- 1Business and Tourism School, Sichuan Agricultural University, Dujiangyan, China

- 2College of Management, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

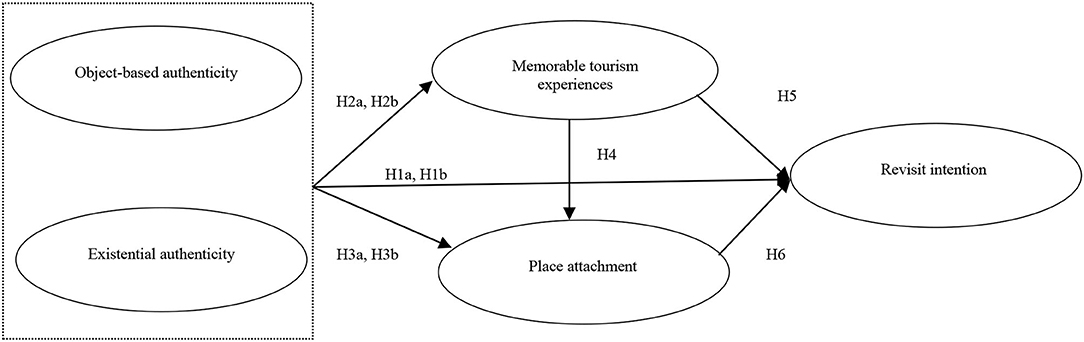

The authenticity of heritage tourism is an important factor for attracting tourists. Research has shown that authenticity is related to revisit intention. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of heritage tourism authenticity on revisit intention. Drawing on cognitive appraisal theory, we constructed a model of the mechanism underlying this relationship. Questionnaires were distributed at one world heritage site (the Dujiangyan irrigation system) in China, and data from 596 valid cases were collected. Using structural equation modeling, the results showed that authenticity, directly and indirectly, affects tourists' revisit intention via memorable tourism experiences and place attachment. The current paper enriches existing literature on the relationship between authenticity and revisit intention and provides a theoretical basis for promoting authenticity and revisit intention in heritage tourism.

Introduction

As a way for tourism to promote people to experience symbols and projects from different historical periods, heritage tourism has been extensively explored by academics. Authenticity is the core attribute of heritage tourism (Lee et al., 2016) and is regarded as an original and common value (Frisvoll, 2013). It is an important factor for tourists to experience tourist attractions set in different historical periods (Frisvoll, 2013). Indeed, one of the primary aims of heritage tourism is the pursuit of authenticity (Park et al., 2019). However, the current understanding of authenticity has changed; the focus has shifted from object-based to subject-based tourism (Wang, 1999). Therefore, authenticity connects the supply and demand elements of heritage tourism (Lu et al., 2015) and has become an important topic of interest regarding heritage tourism destinations and tourist behavior (Zhou et al., 2015).

Revisit intention (RI), which is an important variable to measure a tourist's intention to revisit or return to a destination, is not only an important aspect of tourist behavior but also an essential indicator of the successful development of destinations (Baker and Crompton, 2000). For heritage destinations, understanding the determinants of tourists' willingness to revisit can provide managers with the foundation for managing heritage destinations. Studies have shown that the authenticity of heritage tourism is an essential factor that influences tourists' RI (Yi et al., 2017; Park et al., 2019). However, the relationship between authenticity and RI is not consistent. For example, Kolar and Zabkar (2010) proposed that objective authenticity (OA), constructive authenticity (CA), and existential authenticity (EA) affect RI (Kolar and Zabkar, 2010). Furthermore, other studies have suggested that OA and CA affect RI, whereas EA does not (Zhou et al., 2013). In addition, Park et al. (2019) explored the mediating effect of satisfaction on the relationship between authenticity and loyalty. The results showed that CA and EA affect loyalty via satisfaction, whereas OA does not correlate with satisfaction or loyalty. Thus, current research on how tourism authenticity affects tourists' RI remains unclear. This raises the question, how does tourism authenticity influence tourists' RI?

In the relationship between tourism authenticity and RI, tourism authenticity may be regarded as an environmental stimulus, and RI may be considered a human behavioral response. The cognitive appraisal theory (CAT) of the emotion theory explains that behavior is formed by the interaction between individuals and the environment, which is valuable for studying consumer behavior in the environment. According to the CAT, consumer behavior is produced in response to external stimuli. Specifically, consumers perform cognitive and emotional assessments following exposure to external stimuli, which eventually leads to specific behavior. Although tourism authenticity may not be the direct cause of RI, it may provide an environmental stimulus for RI. Memorable tourism experiences (MTEs), which are experiences that tourists actively remember after visiting a tourist destination (Kim et al., 2012), are cognitive evaluations of external stimuli (such as tourism authenticity). Relevant studies have shown that tourism authenticity correlates with MTEs (Kesgin et al., 2021). Moreover, cognitive evaluations of external stimuli produce emotional responses. Studies have shown that MTEs are associated with place attachment (PA) (Jorgensen and Stedman, 2006). In addition, emotional responses induce specific behaviors, and studies have demonstrated that PA correlates with RI (Yu et al., 2010).

Therefore, based on the CAT, this study introduced a cognitive (namely, MTEs) and an emotional variable (namely, PA) and explored the role of MTEs and PA in the relationship between tourism authenticity and RI. The study aimed to deepen our understanding of authenticity and its theoretical role in the formation of RI and provide practical guidance for the application of authenticity to heritage tourism sites.

Literature Review

Cognitive Appraisal Theory

The CAT is an important theory that explains consumers' response to external stimuli (Bougie et al., 2003; Soscia, 2007) and states that subjective evaluation stimuli include environmental events, personal concerns, historical experiences, and other sensitivities. Evaluation is an individual's cognitive response to a stimulant. Emotion is the psychological interpretation of the individual's cognitive evaluation of a stimulant. Consumer behavior refers to the specific behavior that can induce relevant emotions after an individual evaluates a stimulant (Bagozzi et al., 1999). Therefore, according to the CAT theory, an individual's subjective interpretation of a stimulant affects his or her cognitive evaluation and emotional response (Lazarus and Lazarus, 1991). Emotions affect behavioral responses and are an individual's adaptive meaning analysis or evaluation of the environment in regard to his or her interests (Lazarus and Lazarus, 1991). Thus, when an environment stimulates people, people will also respond to the stimulus. This form of individual evaluation of the environment involves both internal and external evaluation. Internal evaluation is the internal perceptual evaluation of personalities, beliefs, and goals, that is, the perceptual evaluation of the self. In contrast, external evaluation refers to the external perceptual evaluation of product performance and feedback from others, that is, the perceptual evaluation of the environment (Lazarus and Lazarus, 1991).

Drawing on the CAT theory, this paper explores the impact of heritage tourism authenticity on tourists' RI. Specifically, we investigated the authenticity of heritage tourism destinations as stimulus factors: MTEs as cognitive evaluation, PA as an emotion, and RI as a behavioral response.

Authenticity in Heritage Tourism

With the development of the experience economy, tourists' demand for cultural tourism has grown (Xu et al., 2014). Heritage tourism refers to a form of tourism aimed at learning about and experiencing local culture and heritage (Poria et al., 2003). Therefore, heritage tourism is an important part of cultural tourism (Seyfi et al., 2019). Because of its association with RI, tourists' experience is extremely important for the development of destinations (Pearce, 2009). In heritage tourism, discussions around the tourist experience are usually related to authenticity, whereby the experience or product is original and authentic (Yeoman et al., 2007). As a new approach to conducting business and promoting activities, information and communication technology is currently used widely in tourism and has a significant impact on the tourist experience (Cantoni, 2020; Stylos et al., 2021). Studies have indicated that the use of social media in museums and cultural heritage can improve tourists' positive experience (Vassiliadis and Belenioti, 2017) and brand equity (Belenioti et al., 2019). In addition, virtual reality has been recognized as a powerful tool to enhance the heritage experience and is considered a supplement to the real travel experience (Mura et al., 2017).

Authenticity is a dynamic concept. OA has been described by MacCannell (1973) and Boorstin (1992), CA has been described by Cohen (1988); Bruner (1994), and EA has been described by Wang (1999). Among these, OA is considered the primitiveness of the museum style measured using objective standards (MacCannell, 1973); CA assumes that objective elements are socially constructed (i.e., a form of symbolic authenticity); and EA considers authenticity as an existential state of being (Wang, 1999). Both OA and CA are related to tourism objects, whereas EA is related to tourism subjects (Wang, 1999).

Object-based authenticity (OBA) refers to authenticity from the perspective of tourism objects. Among these, OA is the cognition of original authentic objects, which is a pure “black and white” concept of “authenticity.” Boorstin (1992) regards authenticity as an inherent attribute of tourism objects and that there is an absolute standard for measuring the authenticity of tourism objects. MacCannell (1973) and Boorstin (1992) believe that OA is genuine and authentic and emphasize the equivalence of the tourism object with the original. With the development of tourism, tourism objects gradually include traces of commercialization. However, tourists can still sense the authenticity of commercialized tourism objects. Tourism object authenticity can be understood from the perspective of social construction; thus, CA has entered people's awareness. Cohen (1988) pointed out that authenticity can be constructed and negotiated. CA is the reality created by tourism operators or authorities and is not the same as OA (Bruner, 1994). The evaluation of object authenticity is variable, and authenticity can offer true symbolic meaning. Regardless of whether authenticity is the OA of the original or the variability of CA, both emphasize the authenticity of tourism objects. With the development of the tourism experience, researchers have begun to shift their attention from tourism objects to tourism subjects, which has led to the topic of EA.

EA was proposed by Wang, who believes that people who live in modern societies and fast-paced working environments can lose their true selves easily (Wang, 1999), and only in unfamiliar territories can people find their true selves (Wang, 1999). Tourism is a particular activity in which people engage in an unfamiliar environment; therefore, tourism activities make it easy for people to find their true selves. EA, which is people-centered, describes the authenticity of personal experiences but does not destroy personal values (Kim and Jamal, 2007). Moreover, EA emphasizes the true self; according to Heidegger (1996), an individual's authentic self is the embodiment of EA. Being an authentic individual means going beyond the existing daily life state, such as one's behavior, activity, and thought, and is a state of individualistic existence.

In conclusion, tourism authenticity comprises OBA and EA. In heritage tourism, the authenticity of tourism attractions is an important factor in tourism motivation. The authenticity of cultural evolution and social construction cannot be ignored, and the authenticity of the tourism subject is indispensable. Therefore, we analyzed the authenticity of heritage tourism according to OBA and EA.

Research Hypothesis

Heritage Tourism Authenticity and Revisit Intention

RI has been extensively explored as an important indicator of tourists' behavior intention and loyalty. RI refers to the possibility of revisiting destinations (Baker and Crompton, 2000). Encouraging tourists to revisit a destination is very important for ensuring the sustainable development of tourism destinations (Ali et al., 2016). Therefore, previous studies have explored the antecedents of RI to understand why tourists revisit destinations (Meleddu et al., 2015). The results have shown that these antecedents of RI include destination image and attributes (Niininen et al., 2004; Hernández-Lobato et al., 2006) and tourists' experiences, such as tourist satisfaction (Antón et al., 2017). From the perspective of authenticity, studies have shown that authenticity is related to RI. Meleddu et al. (2015) reported that tourists' subjective perception of tourism objects affects RI to some degree. In addition, Poria et al. (2003) found that perceived authenticity affects RI in heritage tourism. Furthermore, Shen et al. (2014) revealed that EA correlates with tourists' RI to cultural heritage sites. Kolar and Zabkar (2010) also suggest that OBA and EA affect RI. Moreover, specific to heritage tourism, OBA and EA affect RI. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

H1a: OBA is positively correlated with RI.

H1b: EA is positively correlated with RI.

Heritage Tourism Authenticity and Memorable Tourism Experiences

MTEs are tourists' positive memories and recollections of events after engaging in a tourism activity (Kim et al., 2012). Compared with other types of experiences, MTEs emphasize the memory of the experience, which promotes behavioral intention (Coudounaris and Sthapit, 2017). Currently, research has focused on the dimensions and the antecedent and outcome variables of MTEs. In terms of MTE dimensions, researchers agree that MTEs comprise multiple dimensions. Tung and Ritchie (2011) believed that MTEs are composed of four dimensions: affection, expectations, consequentiality, and recollection, whereas Kim et al. (2012) suggested that MTEs include seven dimensions, which include hedonism, novelty, etc. In regard to destination attributes, MTEs have been suggested to include seven dimensions, which include local culture, infrastructure, natural features, etc. (Kim, 2014), whereas de Freitas Coelho and de Sevilha Gosling (2018) proposed 12 dimensions of MTEs, which include environment, culture, relationships with companions, etc. Although there is variation in the division of the dimensions of MTEs, there is agreement regarding what constitutes an unforgettable tourism experience (de Freitas Coelho and de Sevilha Gosling, 2018). Antecedent variables that affect MTEs include tourists' psychological factors, such as perceived similarity (Wei et al., 2021), and destination level factors, such as destination attributes or services (Kim, 2014). Outcome variables of MTEs include loyalty, RI (Coudounaris and Sthapit, 2017; Chen and Rahman, 2018; Wong and Lai, 2021), subjective well-being (Sthapit and Coudounaris, 2018), and PA (Vada et al., 2019). Taken together, it is evident that MTEs are not only a research hotspot of experiential marketing but also an important concept for understanding and predicting consumer behavior. Therefore, MTEs are an important factor in managing consumer experience and engagement (Taheri et al., 2017).

Authenticity is central to the heritage tourism experience (Hargrove, 2002; Zatori et al., 2018) verified the relationship among participation, authenticity, and the tourist experience and found that authenticity correlates with the tourism experience. Kesgin et al. (2021) confirmed that OBA positively affects MTEs at historical sites, whereas Pine et al. (1999) suggested that people immersed in tourism activities are more likely to have unforgettable experiences. EA comes from engaging in tourism activities (Wang and Mattila, 2015); thus, tourists' participation in activities can create unforgettable experiences (Kim, 2014). Moreover, Cao et al. (2019) reported that social relationships improve tourists' memory of travel experiences in the restaurant environment. Yi et al. (2021a,b) also confirmed that EA affects unforgettable experiences in heritage tourism. In addition, research has indicated that tourism based on authentic objects and sincere interactions leads to positive memorable experiences (Domínguez-Quintero et al., 2020). Therefore, authenticity is associated with MTEs. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis H2a: OBA is positively correlated with MTEs.

Hypothesis H2b: EA is positively correlated with MTEs.

Heritage Tourism Authenticity and Place Attachment

PA refers to an individual's emotional connection with a specific environment (Eisenhauer et al., 2000), the emotional investment in a place (Hummon, 1992), or the degree of evaluation and identification with a particular environment (Moore and Graefe, 1994). PA consists of place dependence and place identity (Bricker and Kerstetter, 2000), which refer to an individual's functional (Gu and Ryan, 2008) and emotional attachment to a place, respectively (Moore and Graefe, 1994). That is, an individual or community uses places as a medium to define oneself and feel a part of the place emotionally. Currently, there is no consensus on the relationship between place identity and place dependence. Several studies have suggested that the two are independent (Kyle et al., 2005), whereas other studies have suggested that the two influence each other (Jorgensen and Stedman, 2001; Lewicka, 2011). As a complex emotion, PA is a positive result of the people–place interaction. PA affects tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Therefore, PA plays a vital role in destination management.

PA reflects the positive state of an individual when approaching a particular place. According to the CAT theory, individuals evaluate the relevance and suitability of the environment to provide personal meaning and subsequently generate emotions. In the tourism context, tourists may form an attachment to a destination because of their satisfaction, specific personal goals, or symbolic meaning.

In other words, tourists may feel a strong sense of authenticity or identify tourist destinations to meet their needs (Meng and Choi, 2016), and the satisfaction of authenticity may result in tourists' PA (Belhassen et al., 2008). Given that authenticity emphasizes the sense of place that tourists experience, when heritage tourism destinations have high OBA, tourists make a positive evaluation of the suitability of the destinations to meet their needs based on the object standard, which results in tourists' functional dependence. Moreover, tourists can obtain an even richer tourist experience through natural tourism objects, which helps promote the identity of heritage sites. In addition, when tourists participate in tourism activities at heritage sites to obtain EA, they become dependent on the heritage site because they escape from their habitual environment. Furthermore, the authentically expressed self-state is conducive to tourists' immersion and self-realization, which strengthens tourists' place identity. Indeed, studies have shown that authenticity is highly correlated with PA (Jiang et al., 2017; Park et al., 2019). Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3a: OBA is positively correlated with PA.

H3b: EA is positively correlated with PA.

Memorable Tourism Experiences and Place Attachment

When engaging in tourism activities, positive experiences gained by tourists help them to become immersed in the environment, obtain higher satisfaction, and provide spiritual meaning to a specific place, which facilitates the formation of their sense of identity and dependence on a place (Tsai, 2016). In other words, positive tourist experiences determine tourists' PA to the destination (Io and Wan, 2018). MTEs are constructed by tourists according to their experience evaluations, which are used to consolidate and strengthen the pleasant memory of the destination experience; therefore, MTEs belong to the positive tourism experience (Kim, 2014), and MTEs positively affect PA (Jorgensen and Stedman, 2006). We hypothesized the following:

H4: MTEs are positively correlated with PA.

Memorable Tourism Experiences and Revisit Intention

Previous studies have shown that tourism experiences affect tourists' RI (Gomez-Jacinto et al., 1999); that is, past tourism experience is considered an important factor in determining whether destinations are revisited (Chandralal and Valenzuela, 2013). RI is deemed a positive outcome of MTEs (Tung and Ritchie, 2011; Kim et al., 2012; Marschall, 2012). Research has demonstrated that there is a correlation between MTEs and RI (Kim et al., 2012), and MTEs are an essential factor in predicting RI (Kim, 2014). Chen and Rahman (2018) found that MTEs of cultural tourism affect loyalty. In addition, Rasoolimanesh et al. (2021) proposed that memorable heritage tourism experiences influence whether tourists return and their recommendations. Therefore, we offered the following research hypothesis:

H5: MTEs are positively correlated with RI.

Place Attachment and Revisit Intention

In tourism experiences, the intensity of PA determines tourists' willingness to revisit the destination. George and George (2004) considered PA as an important antecedent of RI. However, there are differences in the influence of place dependence and place identity on RI (Prayag and Ryan, 2012; Scarpi et al., 2019). Moreover, research has suggested that the PA of tourists to heritage tourism destinations affects RI (Ding et al., 2015). Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H6: PA is positively correlated with RI.

The concept model is shown in Figure 1.

Methodology

Research Site

The Dujiangyan irrigation system, which is one of the world heritage sites of China, served as our study context. The Dujiangyan irrigation system is an ecological engineering feat located in Dujiangyan City in Sichuan Province. It is the world's largest water conservancy project and includes Yuzui, Feisha weir, and Baopingkou. The Dujiangyan irrigation system has beautiful scenery and numerous cultural relics, such as the Fulong Temple, Erwang Temple, Anlan Cable Bridge, Yulei Pass, Lidui Park, Yulei Mountain Park, and the resulting hydrology of water, God, and human sacrifices. In line with UNESCO's statement, the Dujiangyan irrigation system has a history of more than 2,000 years since its establishment and is still in use today, and internationally recognized protection guidelines and rules have been followed to protect and restore projects. The Dujiangyan irrigation system was largely undamaged by the Wenchuan earthquake on May 12, 2008 (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1001). In addition, to celebrate the completion of the Dujiangyan irrigation system, the beginning of the busy spring farming and production season, and the commemoration of Li Bing, a large-scale celebration called the Water Release Festival is held, during the Tomb-Sweeping Festival of the 24 solar terms of the lunar calendar that occurs every year in China, which reproduces the grand occasion of the Dujiangyan water release more than 2,000 years ago. The Dujiangyan Water Release Festival is now part of China's national cultural heritage.

Variable Measurement

We used established scales from relevant literature to measure the variables, and all items were adjusted appropriately in heritage tourism context. Authenticity was measured using the scales developed by Kolar and Zabkar (2010). OBA refers to the authenticity of object orientation and includes four items (e.g., “During my visit to the Dujiangyan irrigation system, I perceived that the overall layout or environment is original”). EA reflects the status of activity orientation and includes six items (e.g., “During my visit to the Dujiangyan irrigation system, I was freed from daily routines and became more of myself”). From the study of Kim et al. (2012) and Lee (2015), we adopted six items (e.g., “I enjoyed the experience and felt excited”) to measure MTEs, which reflect tourists' evaluation of the tourism experience. From the study of Prayag and Ryan (2012), we adopted six items (e.g., “This destination is very special to me”) to measure PA, which reflect tourists' emotional attachment to a particular destination. RI reflects loyalty to the destination and included four items proposed by Backman and Crompton (1991) and Morais and Lin (2010) (e.g., “I would like to visit the Dujiangyan irrigation system again”). A seven-point Likert scale (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) was used for all constructs.

Data Collection and Sample

Self-report is an easy and effective data collection method (Koslowsky and Dishon-Berkovits, 2001), which is the most used in the study of tourist behavior. Relevant studies believed that the impact of self-report on common method variation (CMV) is limited (Fox and Spector, 1999). Therefore, we collected data using a self-reported questionnaire. The survey lasted for 2 months from July 2021 to August 2021, during the Dujiangyan irrigation system's peak tourist season. A total of 620 questionnaires were completed, and 596 valid questionnaires were collected. Among the 596 observations, 54% were female; 42% and 40% were aged 21–34 years and 35–50 years, respectively, and 85% had a bachelor's degree or higher. In terms of occupation distribution, 46% were company employees, and 17, 13, and 14% were self-employed, working at government institutions, and working at public institutions, respectively. For income, 70% earned more than 5,000 RMB per month.

Results

Measurement Model

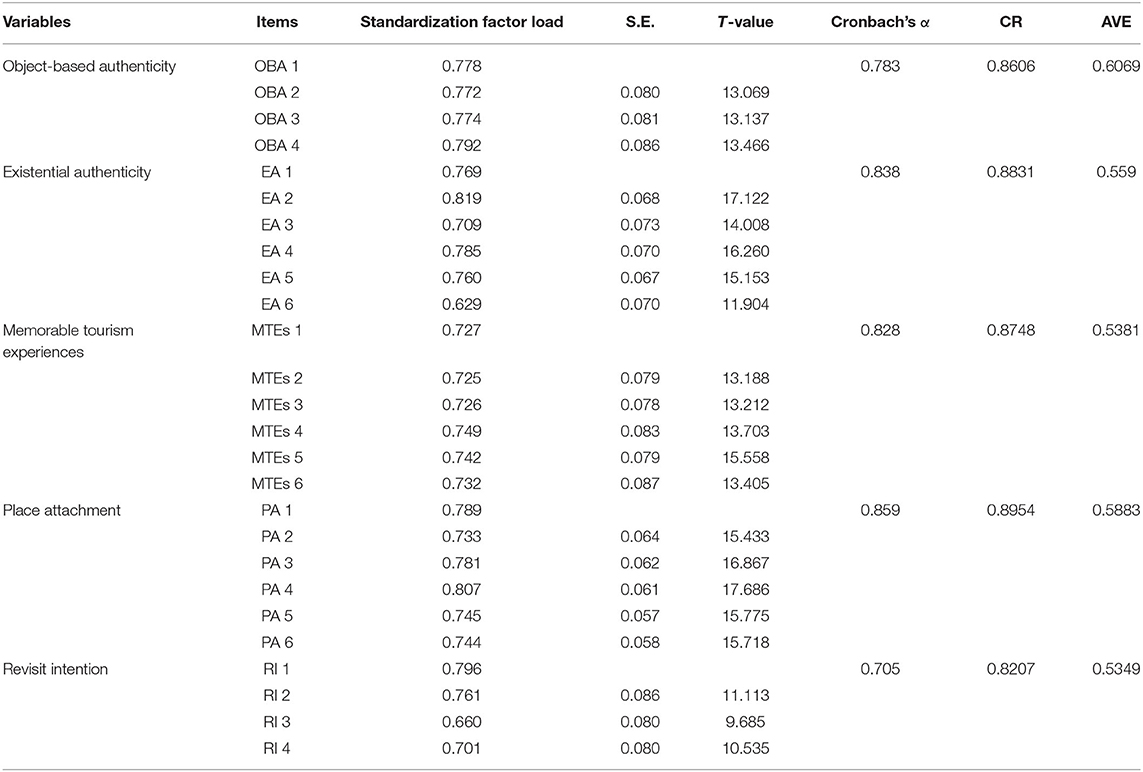

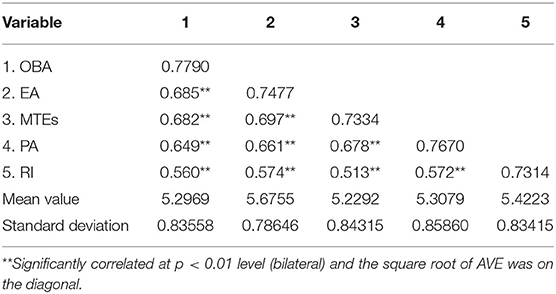

We analyzed 596 valid samples using AMOS 22.0. The mean value of each item ranged from 4.85 to 5.82. CFA was conducted to evaluate whether data were consistent with the measurement model. The results showed that χ2/DF = 2.858, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.0421, CFI = 0.923, IFI = 0.923, and TLI = 0.913. Reliability analysis included Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (CR). As shown in Table 1, Cronbach's alpha (0.705–0.859) and CR (0.8207–0.8954) exceed the recommended standard of 0.70, which indicated good reliability. Standard factor loadings (0.629–0.819) were higher than 0.6 and significant at p < 0.001, as shown in Table 1. Average variance extractions (AVEs, 0.5349–0.6069) were >0.5. The square root of the AVE was higher than the correlation coefficient between corresponding latent constructs (presented in Table 2), which indicated good discriminant validity.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis

As shown in Table 2, OBA was significantly positively correlated with MTEs (r = 0.682, p < 0.01), PA (0.649), and RI (0.560). EA was significantly positively correlated with MTEs (0.697), PA (0.661), and RI (0.574). In addition, MTEs were significantly positively correlated with PA (0.678) and RI (0.513). Finally, there was also a significant positive correlation between PA and RI (0.572).

Structural Model

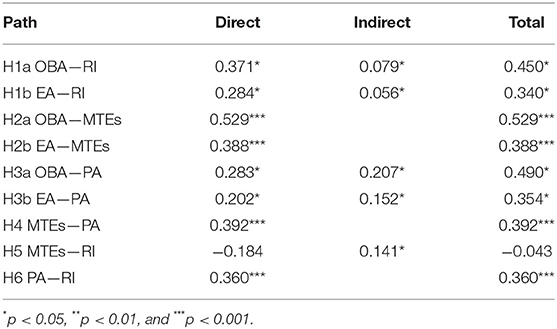

AMOS 22.0 was used to test research hypothesis, and the results are presented in Table 3.

The SEM results verified our proposed model. Authenticity significantly positively affected RI (OBA was β = 0.371, p < 0.05; EA was β = 0.284, p < 0.05). Therefore, H1a and H1b were supported.

Additionally, both OBA and EA significantly positively affected MTEs (OBA was β = 0.529, p < 0.001; EA was β = 0.388, p < 0.001). Therefore, H2a and H2b were supported. In addition, both OBA and EA significantly positively affected PA (OBA was β = 0.283, p < 0.05; EA was β = 0.202, p < 0.05). Therefore, H3a and H3b were supported.

MTEs significantly positively affected PA (β = 0.392, p < 0.001) but not RI (β = −0.184, p > 0.05). As such, H4 was supported, whereas H5 was not supported. PA significantly positively affected RI (β = 0.360, p < 0.001). Thus, H6 was also supported.

The direct, indirect, and total effects of the constructs under analysis are presented in Table 4. OBA had the largest impact on RI, followed by EA. Regarding cognition, MTEs indirectly affected RI. As for emotion, PA indirectly impacted the relationship between authenticity and RI and between MTEs and RI.

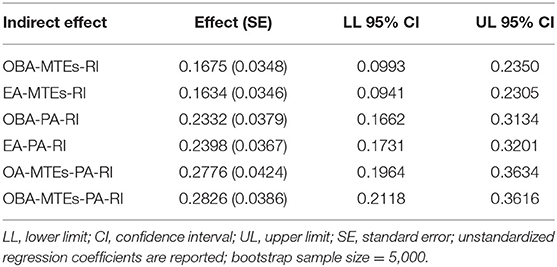

MTEs and PA played a mediating role in the relationship between authenticity and RI. We used bootstrap analysis to test the mediating role of MTEs and PA (Preacher and Hayes, 2004; Hayes, 2013). The results showed that the confidence intervals (CIs) for MTEs on the relationships between OBA and RI (lower limit [LL] = 0.0993, upper limit [UL] = 0.2350) and between EA and RI (LL = 0.0941, UL = 0.2305) did not include zero, and the size of mediation effect ranged from 0.1675 to 0.1634 (Table 5). The CIs for PA on the relationships between OBA and RI (LL = 0.1662, UL = 0.3134) and between EA and RI (LL = 0.1731, UL = 0.3201) did not include zero, and the size of mediating effect ranged from 0.2332 to 0.2398. Similarly, the CIs of MTEs and PA on the relationships between OBA and RI (LL = 0.1964, UL = 0.3634) and between EA and RI (LL = 0.2118, UL = 0.3631) did not include zero, and the size of mediating effect ranged from 0.2776 to 0.2826.

Discussion

The authenticity of heritage tourism destinations is an important factor for attracting tourists. Previous studies have shown that authenticity is related to RI. Therefore, we explored the impact of authenticity on RI in the context of the CAT theory and reached the following conclusions: (1) authenticity affects MTEs, PA, and RI; (2) MTEs affect PA but have no effect on RI; (3) PA affects RI; (4) both MTEs and PA mediate the relationship between authenticity and RI.

First, tourism authenticity affected RI, which is identical with the conclusion in the past (Kolar and Zabkar, 2010; Yi et al., 2017). Tourists were more likely to revisit destinations if they perceived heritage destinations as authentic. Specifically, when tourists perceived a high level of OBA, they were likely to revisit the destination. Moreover, tourists were more likely to revisit the destination when they perceived a high level of EA from relevant activities provided by the heritage tourism destination.

Second, authenticity affected MTEs, which is consistent with the findings of Domínguez-Quintero et al. (2020). This may be because authenticity is related to the tourism experience (Zatori et al., 2018). Specifically, when tourists perceive a high level of authenticity, they will make positive comments on the tourism experience, which eventually leads to high memorability. Therefore, managers must design and provide an authentic experience to meet tourists' expectations and needs and ensure that tourists obtain MTEs. In addition, authenticity affected PA, which is identical with the conclusion in the past (Jiang et al., 2017; Park et al., 2019). In tourism experiences, authenticity emphasizes the sense of place during a tourism experience. Specifically, when heritage tourism destinations provide a high level of OBA and EA, tourists achieve functional and emotional satisfaction, which promotes the formation of PA.

Furthermore, the current study confirmed a significant positive effect of MTEs on PA, which is consistent with the findings of Jorgensen and Stedman (2006) and Vada et al. (2019). MTEs are a vital antecedent variable for PA. When tourists perceive that the heritage tourism destination meets their authenticity needs, they regard destinations as memorable because they experience the original object, obtain the true self, and form a PA to the heritage destination. Moreover, they become more willing to revisit the destination.

Theoretical Implications

This study extended the existing model of authenticity and RI by applying the CAT theory. Previous studies have shown that authenticity affects RI (Kolar and Zabkar, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013), which led subsequent studies to examine the relationships among authenticity, satisfaction or perceived value, and RI (Park et al., 2019; Su et al., 2021). However, these models focused on the cognitive variables and ignored the psychological process of tourists' reactions to authenticity. Research has suggested that cognitive and emotional variables play an important role in consumer behavior (Song and Qu, 2017). Based on the CAT theory, our study introduced cognitive (i.e., MTEs) and affective variables (i.e., PA) and hypothesized that environmental stimulation (i.e., authenticity) of heritage tourism destinations affects tourists' cognitive evaluation (i.e., MTEs), which subsequently affects tourists' behavior (i.e., RI) via an emotional response (i.e., PA). Because this theoretical model focuses on tourists' cognitive and emotional responses to environmental stimuli, it provides a deeper understanding of the relationship between authenticity and RI.

This study revealed a potentially important, yet previously unexamined, mechanism of the relationship between authenticity and RI. Previous studies have proposed that MTEs play a mediating role in the relationship between authenticity and RI (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021). Other studies have suggested that authenticity affects RI via PA (Shang et al., 2020; Yi et al., 2021b). Drawing on the CAT theory, we found that both MTEs and PA play an independent mediating role successively between authenticity and RI, which is consistent with previous studies (Shang et al., 2020; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021; Yi et al., 2021a). In addition, MTEs and PA played a multiple-step mediating role in the relationship between authenticity and RI. This mechanism depicts tourists' psychological process underlying the relationship between authenticity and RI.

Finally, our findings enrich the research on the relationship between MTEs and PA. We examined the relationship between MTEs and PA to heritage tourism destinations and further verified the findings of Jorgensen and Stedman (2006). Previous studies explored the relationship between MTEs and PA by including MTEs as an independent variable and PA as a dependent variable (Tsai, 2016; Vada et al., 2019). However, few studies have considered MTEs and PA as multiple mediating variables. Thus, our examination of the multiple mediating effects of MTEs and PA in heritage tourism enriches the research on the relationship between MTEs and PA.

Practical Implications

This study focused on tourists' behavior in regard to the authenticity of heritage tourism to provide practical guidance for improving heritage tourism destinations. The local authorities of heritage tourism destinations should maintain the authenticity of both tangible (e.g., the architecture) and intangible (e.g., local legends and stories) elements and offer activities that trigger a sense of authenticity in tourists to encourage revisits. Specifically, local authority marketers and managers should strive to protect and understand OBA and design tourism activities that drive EA. This requires maintaining the authenticity of local buildings and legends and considering projects that tourists are likely to participate in when designing authentic tourism activities. Furthermore, tourism activities should help introduce tourists to local culture and enable them to communicate with residents in a natural, sincere, and friendly manner.

Heritage tourism destination managers should also aim to promote MTEs and PA by facilitating OBA and EA. This requires local managers to promote the organic unity of authenticity protection and utilization. Therefore, heritage tourism destinations should strive to unify economic and social benefits to protect and utilize authenticity. The tourist experience should be optimized by coordinating between OBA and EA to generate MTEs and form PA.

Our study revealed that MTEs significantly increase PA. This requires managers of heritage tourism destinations to recognize the importance of MTEs and carefully design products and services based on authenticity, create MTEs for tourists, and improve tourists' PA to heritage tourism destinations.

Our research also shows that PA significantly increases RI. PA is an individual's evaluation and recognition of a specific environment (Moore and Graefe, 1994). Tourists' attachment to a tourist destination requires positive interactions, where the stronger the attachment to a place, the more the tourists' willingness can be stimulated to revisit the tourist destination. Therefore, managers of heritage tourism destinations should take into account that during a tourism experience, tourists form attachments to destinations, which encourages them to revisit.

Limitations

Although this paper focuses on the role of MTEs and PA in the influence of heritage tourism authenticity on revisit intention, this relationship is not unique, and follow-up research should also consider cognitive variables, such as destination image and perceived value, and emotional variables, such as nostalgia. The survey only acquired cross-sectional data over 2 months. To improve the robustness and effectiveness of the findings, the survey should be conducted during different periods in future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

GZ and WC conceived the study. GZ, WC, and YW wrote the manuscript. All authors designed the study, collected, analyzed the data, read, approved the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sichuan Centre for Rural Development Research (Grant No. CR2011) and the Special Program of Social Sciences of Sichuan Agricultural University 2019.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, F., Ryu, K., and Hussain, K. (2016). Influence of experiences on memories, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: a study of creative tourism. J. Trav. Tour. Market. 33, 85–100. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2015.1038418

Antón, C., Camarero, C., and Laguna-Garcia, M. (2017). Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations. Curr. Iss. Tour. 20, 238–260. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.936834

Backman, S. J., and Crompton, J. L. (1991). The usefulness of selected variables for predicting activity loyalty. Lei. Sci. 13, 205–220. doi: 10.1080/01490409109513138

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., and Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. J. Aca. Market. Sci. 27, 184–206. doi: 10.1177/0092070399272005

Baker, D. A., and Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 27, 785–804. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

Belenioti, Z. C., Tsourvakas, G., and Vassiliadis, C. A. (2019). “Do social media affect museums' brand equity? An exploratory qualitative study,” in Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism, eds A. Kavoura, E. Kefallonitis, and A. Giovanis (Cham: Springer), 533–540. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-12453-3_61

Belhassen, Y., Caton, K., and Stewart, W. P. (2008). The search for authenticity in the pilgrim experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 35, 668–689. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2008.03.007

Bougie, R., Pieters, R., and Zeelenberg, M. (2003). Angry customers don't come back, they get back: the experience and behavioral implications of anger and dissatisfaction in services. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 31, 377–393. doi: 10.1177/0092070303254412

Bricker, K. S., and Kerstetter, D. L. (2000). Level of specialization and place attachment: an exploratory study of whitewater recreationists. Leis. Sci. 22, 233–257. doi: 10.1080/01490409950202285

Bruner, E. M.. (1994). Abraham Lincoln as authentic reproduction: a critique of postmodernism. Am. Anthropol. 96, 397–415. doi: 10.1525/aa.1994.96.2.02a00070

Cantoni, L.. (2020). Digital Transformation, Tourism and Cultural Heritage. In a Research Agenda for Heritage Tourism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK. doi: 10.4337/9781789903522.00025

Cao, Y., Li, X. R., DiPietro, R., and So, K. K. F. (2019). The creation of memorable dining experiences: formative index construction. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 82, 308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.010

Chandralal, L., and Valenzuela, F. R. (2013). Exploring memorable tourism experiences: Antecedents and behavioural outcomes. J. Econ. Busi. 1, 177–181. doi: 10.7763/JOEBM.2013.V1.38

Chen, H., and Rahman, I. (2018). Cultural tourism: an analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manage. Pers. 26, 153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.006

Cohen, E.. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 15, 371–386. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

Coudounaris, D. N., and Sthapit, E. (2017). Antecedents of memorable tourism experience related to behavioral intentions. Psychol. Market. 34, 1084–1093. doi: 10.1002/MAR.21048

de Freitas Coelho, M., and de Sevilha Gosling, M. (2018). Memorable Tourism Experience (MTE): scale proposal and test. Tour. Manage. Stu. 14, 15–24. doi: 10.18089/tms.2018.14402

Ding, F., Jiang, H., Hou, S., and Zhou, J. (2015). The influencing factors and mechanism on tourists' revisit intention of Chinese traditional ancient village-a case of Zhouzhuang. Hum. Geo. 30, 146–152. doi: 10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2015.06.023

Domínguez-Quintero, A. M., González-Rodríguez, M. R., and Paddison, B. (2020). The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr. Iss. Tour. 23, 248–260. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1502261

Eisenhauer, B. W., Krannich, R. S., and Blahna, D. J. (2000). Attachments to special places on public lands: an analysis of activities, reason for attachments, and community connections. Soc. Nat. Res. 13, 421–441. doi: 10.1080/089419200403848

Fox, S., and Spector, P. E. (1999). A model of work frustration–aggression. J. Org. Behav. 20, 915–931. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199911)20:6<915::AID-JOB918>3.0.CO;2-6

Frisvoll, S.. (2013). Conceptualising authentication of ruralness. Ann. Tour. Res. 43, 272–296. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.006

George, B. P., and George, B. P. (2004). Past visits and the intention to revisit a destination: Place attachment as the mediator and novelty seeking as the moderator. J. Tour Stu. 15, 51−66. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.200501358

Gomez-Jacinto, L., Martin-Garcia, J.S., and Bertiche-Haud'Huyze, C. (1999). A model of tourism experience and attitude change. Ann. Tour Res, 26, 1024–1027.

Gu, H., and Ryan, C. (2008). Place attachment, identity and community impacts of tourism—the case of a Beijing hutong. Tour. Manage. 29, 637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.006

Hargrove, C. M.. (2002). Heritage tourism. Cult. Res. 25, 10–11. Available online at: https://hisp323.umwblogs.org/files/2013/09/hargrove-cheryl.pdf

Hayes, A. F.. (2013). An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hernández-Lobato, L., Solis-Radilla, M. M., Moliner-Tena, M. A., and Sánchez-García, J. (2006). Tourism destination image, satisfaction and loyalty: a study in Ixtapa-Zihuatanejo, Mexico. Tour. Geogr. 8, 343–358. doi: 10.1080/14616680600922039

Hummon, D.. (1992). “Community Attachment,” in Place Attachment. Human Behavior and Environment, eds I. Altman and S. M. Low (Boston, MA: Springer), 253–278. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8753-4_12

Io, M. U., and Wan, P. Y. K. (2018). Relationships between tourism experiences and place attachment in the context of Casino Resorts. J. Qual. Ass. Hosp. Tour. 19, 45–65. doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2017.1314801

Jiang, Y., Ramkissoon, H., Mavondo, F. T., and Feng, S. (2017). Authenticity: the link between destination image and place attachment. J. Hosp. Market.. 26, 105–124. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2016.1185988

Jorgensen, B. S., and Stedman, R. C. (2001). Sense of place as an attitude: lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 21, 233–248. doi: 10.1006/jevp.2001.0226

Jorgensen, B. S., and Stedman, R. C. (2006). A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. J. Environ. Manage. 79, 316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.08.003

Kesgin, M., Taheri, B., Murthy, R. S., Decker, J., and Gannon, M. J. (2021). Making memories: a consumer-based model of authenticity applied to living history sites. Int. J. Cont. Hosp. Manage. 33, 3610–3635. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2020-1467

Kim, H., and Jamal, T. (2007). Touristic quest for existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 34, 181–201. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.07.009

Kim, J. H.. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: the development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manage. 44, 34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.02.007

Kim, J. H., Ritchie, J. B., and McCormick, B. (2012). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J. Trav. Res. 51, 12–25. doi: 10.1177/0047287510385467

Kolar, T., and Zabkar, V. (2010). A consumer-based model of authenticity: an oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manage. 31, 652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010

Koslowsky, M., and Dishon-Berkovits, M. (2001). Self-report measures of employee lateness: Conceptual and methodological issues. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 10, 145–159. doi: 10.1080/13594320143000609

Kyle, G., Graefe, A., and Manning, R. (2005). Testing the dimensionality of place attachment in recreational settings. Environ. Behav. 37, 153–177. doi: 10.1177/0013916504269654

Lee, S., Phau, I., Hughes, M., Li, Y. F., and Quintal, V. (2016). Heritage tourism in Singapore Chinatown: A perceived value approach to authenticity and satisfaction. J. Trav. Tour. Market. 33, 981–998. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2015.1075459

Lee, Y. J.. (2015). Creating memorable experiences in a reuse heritage site. Ann. Tour Res. 55, 155–170. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.09.009

Lewicka, M.. (2011). Place attachment: how far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31, 207–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Lu, L., Chi, C. G., and Liu, Y. (2015). Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manage. 50, 85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.026

MacCannell, D.. (1973). Staged authenticity: arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Soc. 79, 589–603. doi: 10.1086/225585

Marschall, S.. (2012). “Personal memory tourism” and a wider exploration of the tourism– memory nexus. J. Tour. Cult. Change 10, 321–335. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2012.742094

Meleddu, M., Paci, R., and Pulina, M. (2015). Repeated behaviour and destination loyalty. Tour. Manage. 50, 159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.032

Meng, B., and Choi, K. (2016). The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists' intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manage. 57, 397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.003

Moore, R. L., and Graefe, A. R. (1994). Attachments to recreation settings: the case of rail-trail users. Leis. Sci. 16, 17–31. doi: 10.1080/01490409409513214

Morais, D. B., and Lin, C. H. (2010). Why do first-time and repeat visitors patronize a destination? J. Trav. Tour. Market. 27, 193–210. doi: 10.1080/10548401003590443

Mura, P., Tavakoli, R., and Pahlevan Sharif, S. (2017). “Authentic but not too much”: exploring perceptions of authenticity of virtual tourism. Inf. Tech. Tour. 17, 145–159. doi: 10.1007/s40558-016-0059-y

Niininen, O., Szivas, E., and Riley, M. (2004). Destination loyalty and repeat behaviour: an application of optimum stimulation measurement. Int. J. Tour. Res. 6, 439–447. doi: 10.1002/jtr.511

Park, E., Choi, B. K., and Lee, T. J. (2019). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manage. 74, 99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.001

Pearce, P.. (2009). The relationship between positive psychology and tourist behavior studies. Tour Anal 14, 37–48 doi: 10.3727/108354209788970153

Pine, B. J., Pine, J., and Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Poria, Y., Butler, R., and Airey, D. (2003). The core of heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 30, 238–254. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00064-6

Prayag, G., and Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists' loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Trav. Res. 51, 342–356. doi: 10.1177/0047287511410321

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res Met. Ins. Comp. 36, 717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., and Hatamifar, P. (2021). Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists. J. Destination Market. Manage. 21, 100621. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100621

Scarpi, D., Mason, M., and Raggiotto, F. (2019). To Rome with love: a moderated mediation model in Roman heritage consumption. Tour. Manage. 71, 389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.030

Seyfi, S., Hall, C., and Fagnoni, E. (2019). Managing world heritage site stakeholders: a grounded theory paradigm model approach. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 308–324. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527340

Shang, W., Qiao, G., and Chen, N. (2020). Tourist experience of slow tourism: From authenticity to place attachment–a mixed-method study based on the case of slow city in China. Asia. Pac. J. Tour Res. 25, 170–188. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2019.1683047

Shen, S., Guo, J., and Wu, Y. (2014). Investigating the structural relationships among authenticity, loyalty, involvement, and attitude toward world cultural heritage sites: An empirical study of Nanjing Xiaoling Tomb, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 19, 103–121. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2012.734522

Song, J., and Qu, H. (2017). The mediating role of consumption emotions. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 66, 66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.015

Soscia, I.. (2007). Gratitude, delight, or guilt: the role of consumers' emotions in predicting post-consumption behaviors. Psychol. Market. 24, 871–894. doi: 10.1002/mar.20188

Sthapit, E., and Coudounaris, D. N. (2018). Memorable tourism experiences: antecedents and outcomes. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour.18, 72–94. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2017.1287003

Stylos, N., Zwiegelaar, J., and Buhalis, D. (2021). Big data empowered agility for dynamic, volatile, and time-sensitive service industries: the case of tourism sector. Int. J. Cont. Hosp. Manage. 33, 1015–1036. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-07-2020-0644

Su, Y., Xu, J., Sotiriadis, M., and Shen, S. (2021). Authenticity, perceived value and loyalty in marine tourism destinations: the case of Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province, China. Sustainability. 13, 3716. doi: 10.3390/su13073716

Taheri, B., Coelho, F. J., Sousa, C. M., and Evanschitzky, H. (2017). Mood regulation, customer participation, and customer value creation in hospitality services. Int. J. Cont. Hosp. Manage. 29, 3063–3081. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-07-2016-0389

Tsai, C. T.. (2016). Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 18, 536–548. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2070

Tung, V. W. S., and Ritchie, J. B. (2011). Investigating the memorable experiences of the senior travel market: an examination of the reminiscence bump. J. Trav. Tour. Market.. 28, 331–343. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2011.563168

Vada, S., Prentice, C., and Hsiao, A. (2019). The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 47, 322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.007

Vassiliadis, C., and Belenioti, Z. C. (2017). Museums & cultural heritage via social media: an integrated literature review. Tourismos 12, 97–132. Available online at: https://tourismosjournal.aegean.gr/article/view/533

Wang, C. Y., and Mattila, A. S. (2015). The impact of servicescape cues on consumer prepurchase authenticity assessment and patronage intentions to ethnic restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 39, 346–372. doi: 10.1177/1096348013491600

Wang, N.. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour Res. 26, 349–370. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

Wei, W., Zheng, Y., Zhang, L., and Line, N. (2021). Leveraging customer-to-customer interactions to create immersive and memorable theme park experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Ins. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-10-2020-0205

Wong, J. W. C., and Lai, I. K. W. (2021). Gaming and non-gaming memorable tourism experiences: How do they influence young and mature tourists' behavioural intentions? J. Destination Market.. Manage. 21, 100642. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100642

Xu, H., Wan, X., and Fan, X. (2014). Rethinking authenticity in the implementation of China's heritage conservation: the case of Hongcun Village. Tour. Geogr. 16, 799–811. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2014.963662

Yeoman, I., Brass, D., and McMahon-Beattie, U. (2007). Current issue in tourism: the authentic tourist. Tour. Manage. 28, 1128–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.09.012

Yi, X., Fu, X., Lin, V. S., and Xiao, H. (2021a). Integrating authenticity, well-being, and memorability in heritage tourism: a two-site investigation. J. Trav. Res. 61, 378–393. doi: 10.1177/0047287520987624

Yi, X., Fu, X., So, K. K. F., and Zheng, C. (2021b). Perceived authenticity and place attachment: new findings from Chinese world heritage sites. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 45, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/10963480211027629

Yi, X., Lin, V. S., Jin, W., and Luo, Q. (2017). The authenticity of heritage sites, tourists' quest for existential authenticity, and destination loyalty. J. Trav. Res. 56, 1032–1048. doi: 10.1177/0047287516675061

Yu, Y., Tian, J., and Su, J. (2010). A study of the relativity between place attachment and post-tour behavioral tendencies of visitors: taking value perception and satisfaction experience as intermediary variables. Tour. Sci. 24, 54–62. doi: 10.16323/j.cnki.lykx.2010.03.006

Zatori, A., Smith, M. K., and Puczko, L. (2018), Experience-involvement, memorability authenticity. Tour. Manage. 67, 111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.013

Zhou, Q., Zhang, J., Zhang, H., and Ma, J. (2015). A structural model of host authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 55, 28–45. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.08.003

Keywords: object-based authenticity, existential authenticity, memorable tourism experience (MTE), place attachment, revisit intention

Citation: Zhou G, Chen W and Wu Y (2022) Research on the Effect of Authenticity on Revisit Intention in Heritage Tourism. Front. Psychol. 13:883380. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883380

Received: 25 February 2022; Accepted: 12 April 2022;

Published: 30 May 2022.

Edited by:

Zening Song, Beijing Foreign Studies University, ChinaReviewed by:

Eduardo Moraes Sarmento, Lusophone University of Humanities and Technologies, PortugalJose Weng Chou Wong, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macao SAR, China

Copyright © 2022 Zhou, Chen and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenkuan Chen, d2tjOTg4OUAxNjMuY29t

Gefen Zhou

Gefen Zhou Wenkuan Chen

Wenkuan Chen Yuting Wu

Yuting Wu