- 1Taipei City Government, Taipei, Taiwan

- 2Department of Industrial Education, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 3Chinese Language and Technology Center in Learning Sciences, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 4Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 5Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 6Department of Chinese as a Second Language, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 7Executive Master of Business Administration, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

Attending cram school has long been a trend in ethnic Chinese culture areas, including Taiwan. Despite the fact that school reform policies have been implemented in Taiwan, cram schools have continued to prosper. Therefore, in this educational culture, how to achieve a good educational effect is also a topic worthy of discussion. However, whether students really engage in those tutoring programs provided by cram schools has seldom been studied. To address this gap, this study explored how parents’ hovering attitude toward life and coursework influences their children’s engagement in cram schools. This study targeted those students who attend English cram schools to test the correlates between two types of helicopter parenting, tutoring engagement and continued attendance at cram schools. A total of 320 questionnaires were sent out, and 300 were returned, giving an overall response rate of 93.75%. Excluding seven incomplete or invalid questionnaires, 293 valid questionnaires were received. The results of this study show that hovering behavior awareness is negatively related to cram school engagement, whereas cram school engagement is positively related to the intention to continue attending cram school. Moreover, the results imply that parents should alleviate their helicoptering behavior to enhance their children’s engagement in cram school tutoring programs.

Introduction

In order to improve students’ performance in academic subjects (Zhang et al., 2021), profit-oriented individuals or school-like organizations, specialized schools, or so-called cram schools, offer extra-curricular instruction to students. Their curricula mimic the mainstream school curriculum but they differ from the mainstream system in their instruction. Because of this, cram schools are referred to as “shadow education.” Cram schooling is prevalent worldwide (Yung, 2020a,b) and has been given different names in different countries, such as Buxiban in Taiwan, Juku in Japan, Hagwon in Korea, and private tuition or the shadow education system in Western countries. What cram schooling does is train students’ ability of taking tests on academic subjects in order to pass the entrance examinations of better schools (Wang and Wu, 2021). One of students’ popular out-of-school learning activities during the past few decades has been to go to cram schools, and it is believed that a great number of students around the world have received some type of cram schooling (Liu, 2012). According to Bray and Lykins (2012), more than half of the secondary students in Asian countries, for example, China, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand, go to cram schools for tutoring, and the numbers in Western countries are growing fast as well (e.g., Stastný, 2016; Pearce et al., 2018). In cram schools, students passively absorb “pre-processed” information and then “regurgitate” it in school examinations (Bray and Lykins, 2012). However, there is little research on students’ perceptions of the learning environment that affects their engagement, which is key to learning (Diseth et al., 2010). Central to the learning environment in cram schools is the expectation that the more students invest time and effort in educationally purposeful tasks, the more they will gain from their learning experience (Price et al., 2011). In this sense, in order to understand the learning effectiveness of these schools, it is important to study engagement in cram school environments. Therefore, the present study explored the tutoring engagement of cram school attendees.

As cram school instruction may focus on school content with the hope of improving students’ academic performance through relatively short, temporary instruction (Wang and Wang, 2021), for example, in many English-learning cram schools that offer English tutoring classes are mainly intent on increasing students’ achievement in mainstream education and on high-stakes examinations (Bray, 2011; Yung and Chiu, 2020). In Taiwan, Chung (2013) surveyed 365 senior high school students regarding their motivation to learn English and their receipt of tutoring from cram schools, of whom 342 reported that undertaking tutoring from cram schools, meaning investing time and putting extra effort into learning activities, is beneficial for obtaining high examination scores, which leads to an increase in academic performance. However, his paper contextualizes the discussion in sociocultural conditions, focusing on the Taiwanese setting; little research has collected data related to the role of students’ engagement in the effectiveness of English tutoring. Thus, this study aimed to understand the effects of English tutoring engagement at Taiwan’s cram schools.

Cram schools have diversified their breadth to coordinate with recent educational reforms. In Taiwan, in order for students to learn new skills, they have started to attend cram schools even earlier to have a better chance to apply for the new multi-phased entrance program (providing alternative methods for entrance into senior high schools and universities) (Liu, 2012; Lo and Lin, 2020). A previous study indicated that parents’ attitudes will influence whether they assist their children in doing homework or send them to be tutored at cram schools (Chang, 2019). This centralization of parenting style has indirectly created the current emphasis on cram schools. Consequently, how parenting style affects children’s behavior in cram schools deserves study. This study therefore investigated how helicopter-type parenting affects children’s engagement in English cram school tutoring.

Based on the theory of control-value of achievement emotions that Pekrun proposed in 2006. It is an emotion associated with academic achievement activities and their successful and unsuccessful outcomes (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021). There are two types of outcome emotions, perspective outcome emotions related to whether success can be achieved or failure can be avoided; and retrospective outcome emotions, meaning whether oneself or external sources such as another person or the environment has an effect on the outcome. for example, timeframe for engagement. Retrospective outcome emotions assume that parents opt for encouraging or controlling their children’s attendance of private tutoring if the expectation is to reach a desired educational goal (Guill and Lintorf, 2019). Parents might weigh up whether their child’s study behavior is sufficient, and they might try to encourage their child to receive tutoring (Kuan, 2011). On the other hand, activity-related emotions suppose that students have an intention to engage in the totality of each interaction and control themselves “on-task,” and can deepen our understanding of the learning content in private tutoring programs (Pomerantz, 2019). However, based on activity-related emotion, how students engage in private English tutoring has not been extensively studied; thus, this study took activity-related emotion to form a conceptual model to explore the correlates between parenting style, students’ tutoring engagement, and continued attendance at cram schools. Based on the research objectives, this study proposes 9 research hypotheses and elicits 2 research questions containing the following:

RQ1: Are life and coursework hovering negatively related to three types of tutoring engagement?

RQ2: Are three types of tutoring engagement positively related to continued attendance?

Perceived Helicopter Parenting and Its Effects

A lack of the proper transitions in the parent-child relationship as children develop can limit emerging adults from proceeding through this stage during which they explore the world (Arnett, 2000). Previous studies have indicated that the expectations placed on parents are increasing, and helicopter parenting is becoming more widespread. “Middle-class circumstances and resources” is what is causing the intensive parenting urge (Chudacoff, 2007; Granja et al., 2015) and even those with ample resources for their children may struggle to adhere to an intensive parenting style (Valentine et al., 2019) or helicopter parenting (Padilla-Walker and Nelson, 2012). Helicopter parenting is a relatively new phenomenon that describes a specific type of overparenting (Dumont, 2021) which involves continuous control by the parent over the child’s life, from daily life to interpersonal relationships, and which may hinder the child’s efforts to satisfy their desire for autonomy (Carr et al., 2021). Helicopter parents hover over their children’s lives by being overly protective and unwilling to let go (van Ingen et al., 2015). Low tolerance for error and high parental expectations in authoritarian parenting may be more likely to cause children to internalize similar standards of evaluation into their own performance (Chen et al., in press). Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012) argued that helicopter parents try to structure their children’s behavioral world including their daily activities and coursework in ways that are intrusive and manipulative of their children’s thoughts, feelings, and attachment to their parents. Accordingly, this study explored the consequences of parents’ actions in guiding the participants’ behavior through adopting life hovering and coursework hovering behaviors.

Tutoring Engagement

Behavioral (e.g., completion of academic tasks, on-task behavior), emotional (e.g., excitement, enjoyment in learning activities), and cognitive (e.g., mental effort to understand complex ideas) ways are the connections between students and learning, which is also known as learning engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004; Lawson and Lawson, 2013). As McCormick et al. (2013) pointed out, a substantial amount of research shows that time on task and quality of effort are central to students’ learning and achievement, and are relevant to student engagement (e.g., Ryu and Lombardi, 2015; Sinatra et al., 2015). To evaluate students’ engagement, person-centered approaches may allow for the examination of profiles characterized by different configurations of engagement by individuals (Bae and DeBusk-Lane, 2019). For example, for those students who are excited to participate in learning but who may not have been engaged in the learning activities for processing deep understanding of the content, it is possible that they may receive the results from the examination of a high level of emotional engagement combined with a low level of cognitive engagement. Students who may perform well on on-task behaviors, but who lack concentration in their learning are examples of high behavioral engagement with low cognitive engagement (Bae and DeBusk-Lane, 2019). Taking a person-centered approach to examine how students vary in their multivariate engagement profiles in cram school tutoring is not often seen in previous research; thus, the present study explored participants’ three types of tutoring engagement in English cram schools.

Continued Attendance at English Cram Schools

Emotions regarding attitudes, motivation, affect, interests, and goal orientations are the wide range of disparate constructs in secondary language learning (e.g., Gardner and MacIntyre, 1993; Bown and White, 2010). A previous study has shown that motivational purposes in educational settings with the use of positive psychology interventions (PPI) have striking efficiency (Muro et al., 2018). Moreover, they explained what PPI does to develop students’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement to increase motivation for continued learning and so improve academic outcomes (Muro et al., 2018). As students learn and perceive that they are becoming proficient in certain subjects, it could prompt them to continue learning and improve their academic outcomes as a result. In other words, students’ motivation influences what and how they learn (Muro et al., 2018). Dewaele (2005) argued that positive intervention with pleasure while performing L2 learning tasks can signal arousal of the brain limbic system and influence continuance of learning. Accordingly, the present study explored participants’ continued attendance at English cram schools (hereafter, continued attendance).

Research Model

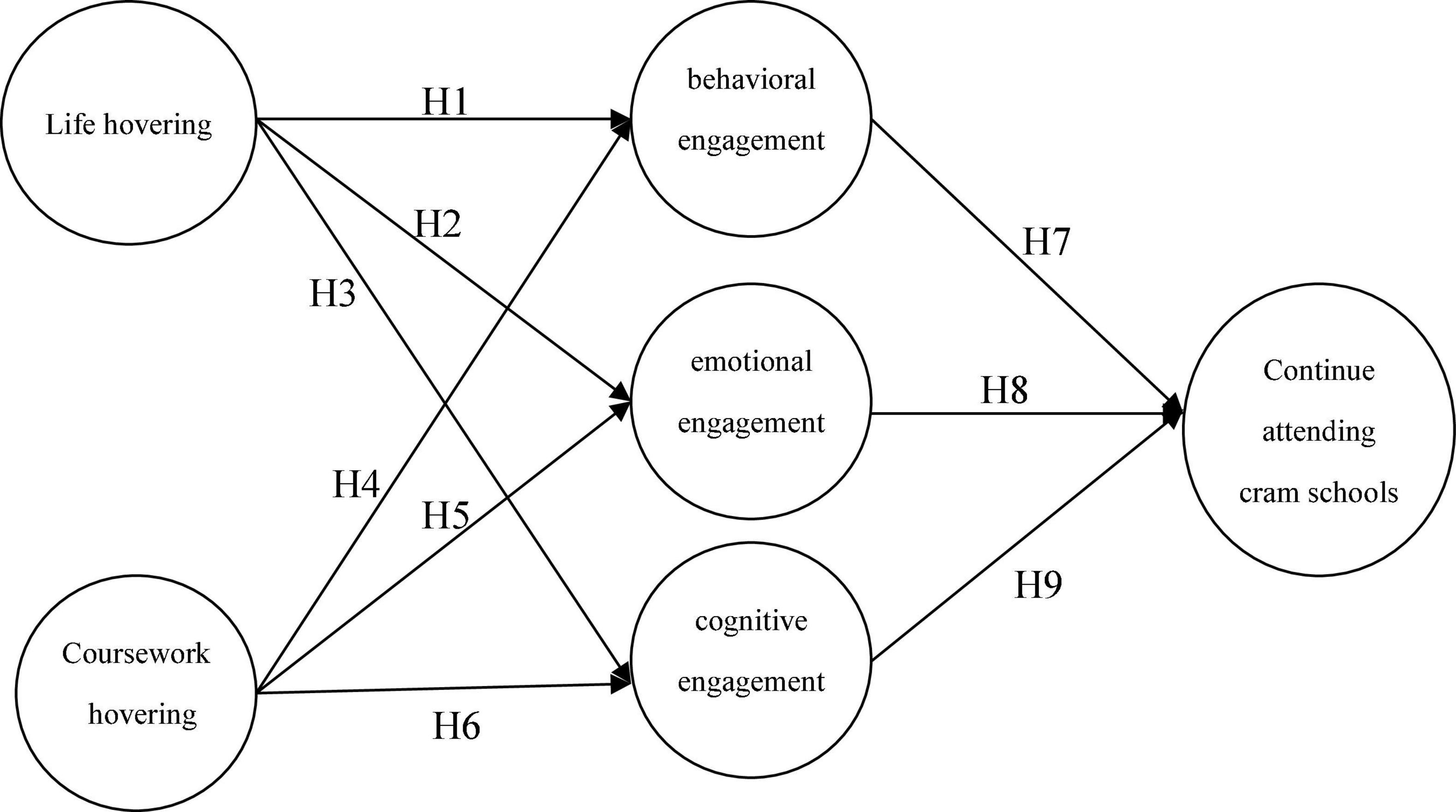

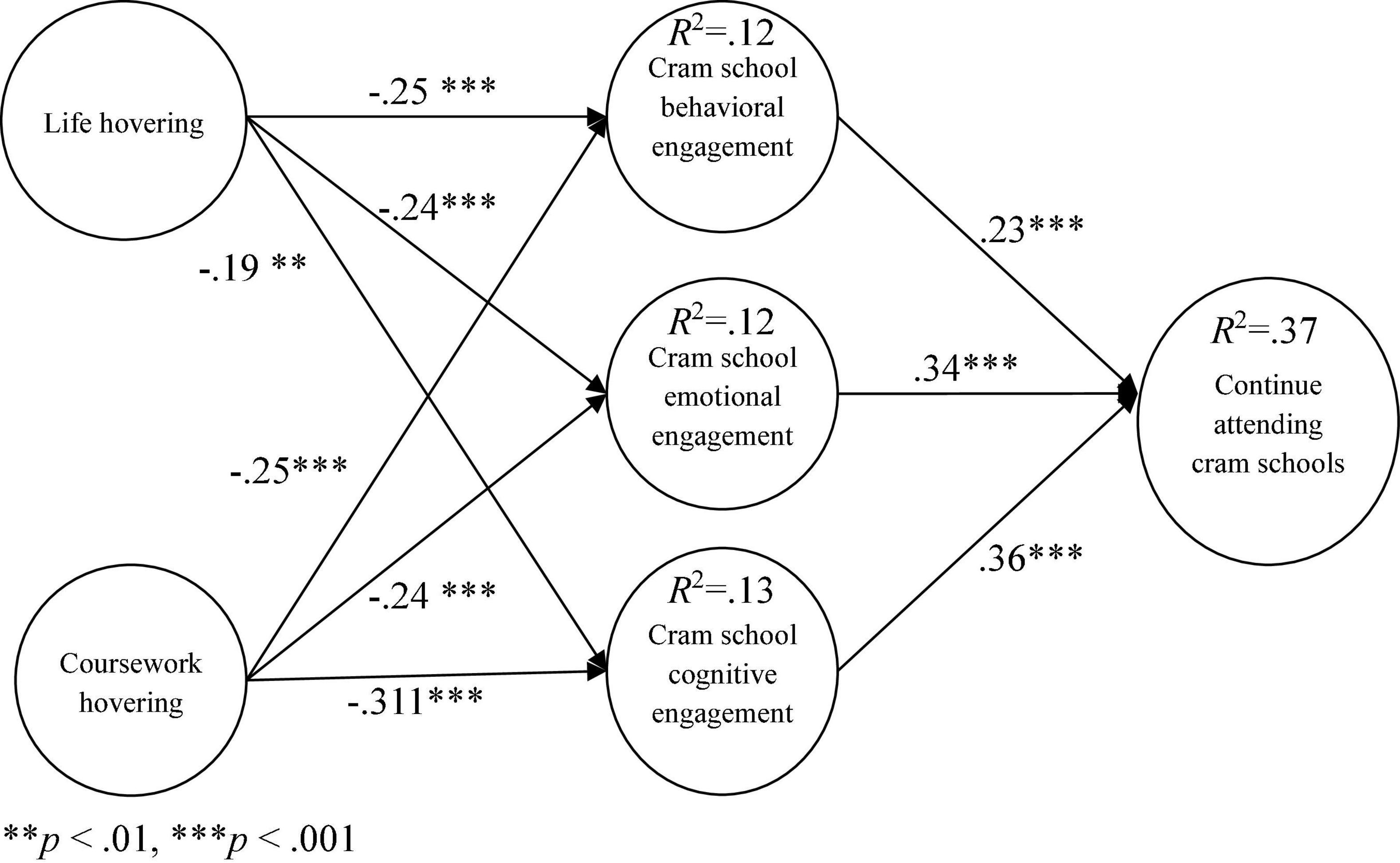

Increasing grades and learning achievement as the congregation of adaptive outcomes is related to engagement (King and Gaerlan, 2014) and also improved attendance and retention (Garn et al., 2017). Accordingly, the research model is proposed as follows. Increasing grades and learning achievement as the congregation of adaptive outcomes is related to engagement (King and Gaerlan, 2014) and also improved attendance and retention (Garn et al., 2017). Accordingly, the research model is proposed as follows, as shown in Figure 1.

Research Hypotheses

Linkage Between Helicopter Parenting and Tutoring Engagement

How parents are responsive and involved in their children’s life or school-related activities is considered as the degree of parental involvement (Luo et al., 2016). Furthermore, parental involvement has an impact on students’ motivation and emotion in learning. For instance, students’ expectancy and value beliefs in doing homework are influenced by how their parents react to their learning (Trautwein et al., 2006). One study has shown that exhibiting lower homework procrastination and higher effort and achievement can be predicted by having parents who are involved in guiding their children to do homework (Dumont et al., 2014). Private tutoring seems to contribute to continued education; if parents see an educational future for their children, they are likely to support their children’s private tutoring attendance (Chugh, 2011; Bray, 2017). Despite serious theoretical advances in the role of engagement in academic settings (Pekrun and Stephens, 2010), the relationship among learning engagement and its antecedent factors has seldom been shown with empirical evidence (Goetz et al., 2010). To address helicopter parenting as an antecedent in the relation with learning engagement, the present study examined how participants’ perceptions of being helicopter parented in terms of life hovering and coursework hovering affected their appraisal of tutoring engagement. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Life hovering is negatively related to behavioral engagement.

H2: Life hovering is negatively related to emotional engagement.

H3: Life hovering is negatively related to cognitive engagement.

H4: Coursework hovering is negatively related to behavioral engagement.

H5: Coursework hovering is negatively related to emotional engagement.

H6: Coursework hovering is negatively related to cognitive engagement.

The Relevance of Tutoring Engagement to Continued Attendance

Previous studies indicate that practice plays an important role in learning, since it may be able to improve the learning process (Gherardi, 2018). Such practice in cram school may help students solve problems, resulting in better engagement (Marques, 2019). For example, engagement in cram school was found to help students in Taiwan with their analytic ability and mathematics scores (Liu, 2012). Private tutoring may also be a double-edged sword (Han and Lee, 2016); practicing may result in students concentrating just on superficial indicators, neglecting deep learning (Sabbagh et al., 2017). Briefly, engagement may be differentially associated with student outcomes (Bae and DeBusk-Lane, 2019). Previous studies have indicated the relevance between cram schooling and improvements in academic performance; however, others have not identified a consequential relationship (Lee et al., 2010; Liu, 2012). Despite those studies of engagement influencing the learning outcomes of the private tutoring system, one study indicated the importance of motivation in having private tutoring impact the possible continuance mechanism to attend English cram schools (Chang, 2019). Thus, how participants’ tutoring engagement is related to their continued attendance was hypothesized as follows:

H7: Behavioral engagement is positively related to continued attendance.

H8: Emotional engagement is positively related to continued attendance.

H9: Cognitive engagement is positively related to continued attendance.

Procedure

Purposive sampling was adopted in this study. The target samples were from English cram schools located in northern Taiwan. With respect to family socioeconomic status, most middle-class parents who work in white-collar jobs tend to send their children to English cram schools to ensure that they have the advanced English ability necessary to perform well in future high-stakes examinations (Chang, 2019). Thus, the participants of this study were students of eight English cram schools. The questionnaire was delivered to 320 attendees of these cram schools. The sampling period was from January 2019 to February 2019. There 300 were returned, giving an overall response rate of 93.75%. Excluding seven incomplete or invalid questionnaires, 293 valid questionnaires were received. To adhere to ethical standards, students were provided with information about what they were being asked to do, their consent was requested, and they were given the option of withdrawing from the study if they so wished.

Participants

Weston and Gore (2006) recommend a minimum sample size of 200 for any SEM study, and the effective participants in this study were above the recommended standard. Valid responses were received from 293 participants in this research. The gender distribution of the study sample was 49.8% female and 50.2% male students. Regarding age, 37.9% were seventh graders, 36.7% were eighth graders, and 25.4% were ninth graders. The weekly frequency with which each participant attended cram schools was: less than two times (3.4%), twice (10.2%), three times (19.1%), four times (26.3%), five times (18.1%), and six or more times (22.9%). Most participants attended cram schools four times per week.

Measurement

The questionnaire and scale used in this research were translated and edited based on previous studies, and were subject to expert validity review by three domain experts. After the content validity was confirmed, we invited seven junior high school students who also attended English cram schools to answer the questionnaire. Based on their feedback, a revised version of the questionnaire with face validity was produced. After its expert validity was confirmed, the questionnaire was then piloted by another 10 students to confirm that they understood the meanings of the items. A 5-point Likert scale with the following options was adopted: 1-strongly disagree; 2-disagree; 3-undecided; 4-agree; and 5-strongly agree. Based on the confirmatory research, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire were re-tested after data collection.

Helicopter Parenting

Hong et al. (2015) differentiated helicopter parenting into life hovering and coursework hovering. The scale of this study used the content of the questionnaire compiled by Hong et al. (2015) to measure the participants’ perceptions of being subject to helicopter parenting. Eight items related to life hovering, and six items related to coursework were included, as shown in Table A1. This scale has α = 0.80, CR = 0.86, AVE = 0.56, and FL = 0.68∼0.81.

Tutoring Engagement

Fredricks et al. (2004) divided learning engagement into three dimensions: behavioral, emotional and cognitive learning engagement. Based on this differentiation method, this study referred to the concept stated by Luan et al., 2020) to measure the participants’ perceptions of being subject to tutoring engagement. Each construct of engagement contained seven items, as shown in Table A1. This scale has α = 0.83∼0.86, CR = 0.80∼0.86, AVE = 0.51∼0.61, and FL = 0.70∼78.

Continued Attendance

Continuity is a form of post-adoption behavior (Chang, 2013). This study utilized and revised the continuous participation willingness scale developed by Hong et al. (2014) to measure participants’ perceptions of continued attendance. Eight items were included in this construct, as shown in Table A1. This scale has α = 0.90, AVE = 0.62, CR = 0.87, and FL = 0.65∼0.90.

Results and Discussion

In this study, SPSS 23.0 was used for reliability and validity analysis, and AMOS 20.0 was used for item analysis, model fit analysis and path analysis. The relevant analysis criteria and results are as the following:

Item Analysis

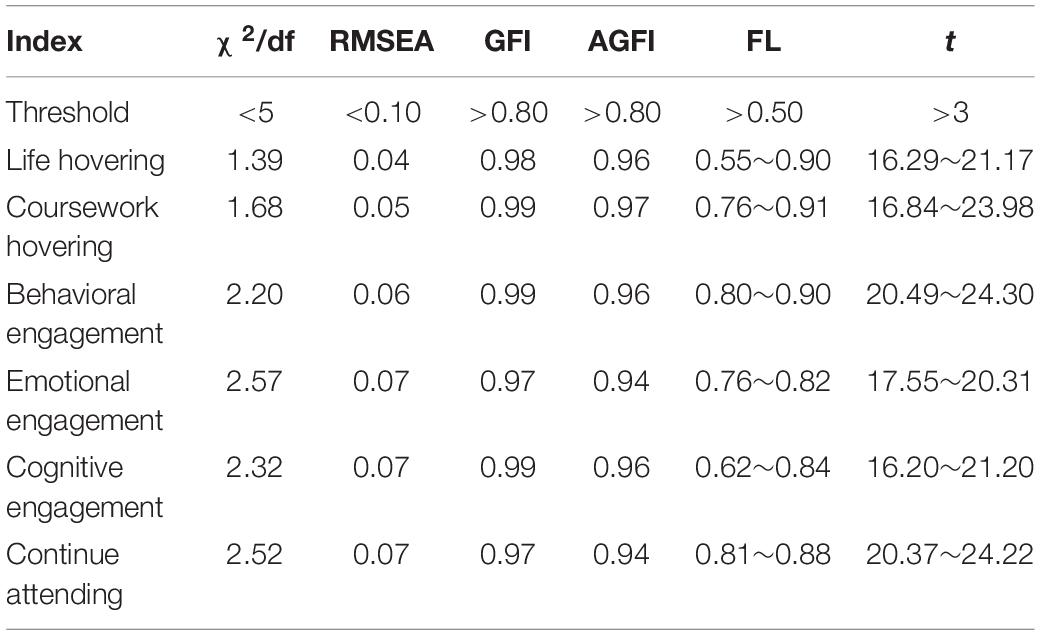

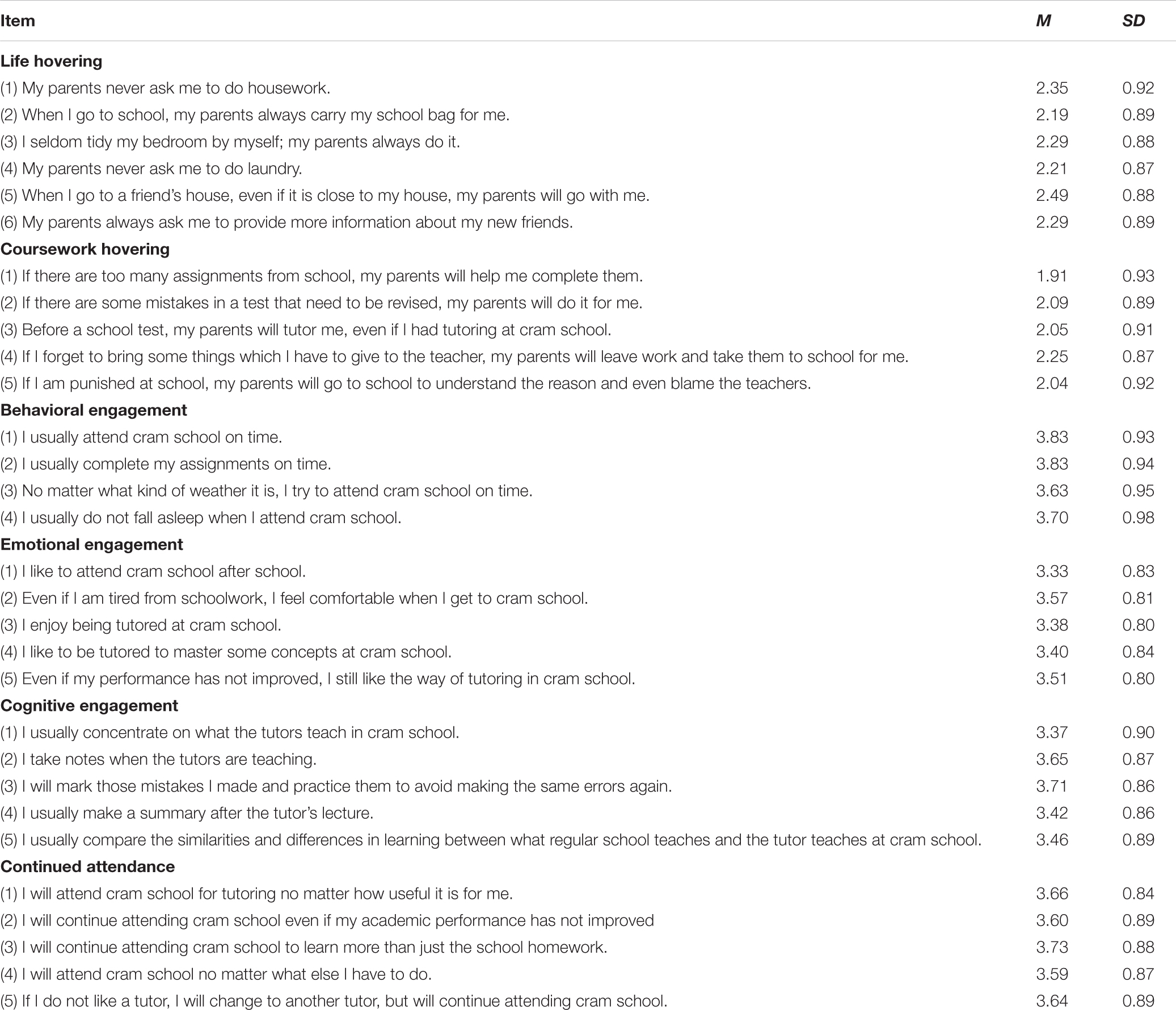

In this phase, 293 participants were used for item analysis in this study. Next, the item analysis method used in this study was first-order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Scholars suggest that the value of χ2 / df should be less than 5; thus, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of the obtained result should be less than 0.10. As the goodness of fit index (GFI) and adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) should be larger than 0.80, items with a factor loading (FL) of less than 0.50 should be deleted from the original questionnaire (Hair et al., 2010; Kenny et al., 2015). The deletion results of each section are as follows: Life hovering: from eight items to six; Coursework hovering: from six items to five; Behavioral engagement: from seven items to four; Emotional engagement: from seven items to five; Cognitive engagement: from seven items to five; and Continued attendance at cram school: from eight items to five, as shown in Table 1.

The external validity of the item can be determined by the critical ratio between the top and bottom groups (Cor, 2016), that is the top 27% and the bottom 27% of all respondents’ values of each item were used to perform a t test. If the t-value (critical ratio) is larger than 3 (***p < 0.001), the item is considered to have good external validity. Table 2 shows that the t-value is larger than 16.20 (***p < 0.001), which means that all of the items retained in the questionnaires are discriminative. All of them are able to verify the response level of different samples (Green and Salkind, 2004), as shown in Table 1.

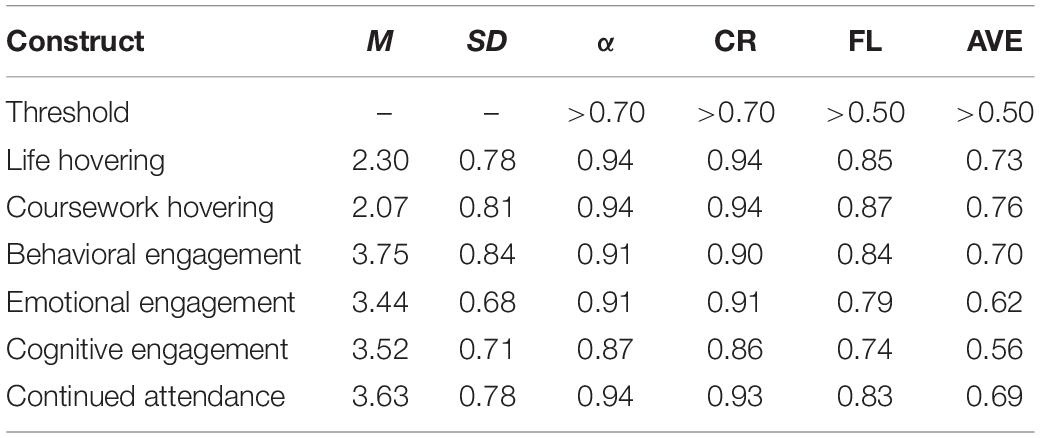

Reliability and Validity Analysis

In this phase, 293 participants were used for item analysis in reliability and validity study, and a Cronbach’s α test was used to confirm the internal consistency of the analysis dimensions, and the reliability was retested with composite reliability (CR). Scholars suggest that values should be considered acceptable when the Cronbach’s α value is larger than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). Hair et al. (2010) suggested that the CR value should be larger than 0.70 to be considered as having composite reliability. In this study, the Cronbach’s α value is between 0.87 and 0.94 (as shown in Table 2), conforming with the suggested thresholds.

The convergence validity of this study was determined by the factor loading (FL) and the average variance extracted (AVE). Hair et al. (2010) suggested that the FL value should be larger than 0.50 to have convergence validity. Thus, items with values of less than 0.50 should be deleted. In this study, the FL values is between 0.74 and 0.87 (as shown in Table 2). Hair et al. (2011) suggested that the AVE value of a dimension should be larger than 0.50 to have convergence validity. In this study, the AVE value is between 0.56 and 0.76 (as shown in Table 2).

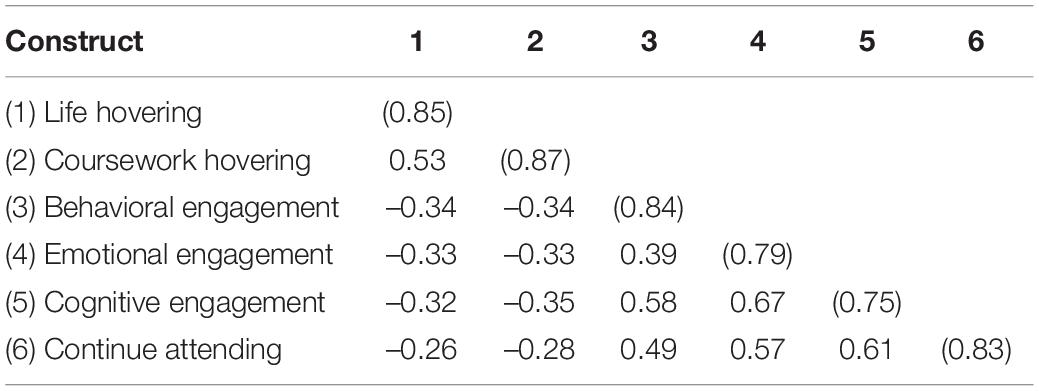

The discriminative validity is determined if the AVE root value of a construct is greater than the Pearson correlation coefficient value of another construct (Awang, 2015). All constructs have good discriminative validity, as shown in Table 3.

Model Fit Analysis

In this phase, 293 participants were used for item analysis in model fit analysis. Hair et al. (2010) suggested that the value of the chi-square degree of freedom ratio (χ2 / df) should be less than 5. The RMSEA should be less than 1. The value of GFI, AGFI, normed fit index (NFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and relative fit index (RFI) should all be larger than 0.8 (Abedi et al., 2015). As for the parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI) and parsimonious goodness of fit index (PGFI), the value should be larger than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2010). The fitting index values of this study are as follows: χ2 = 923.92, df = 455, χ2/df = 2.03, RMSEA = 0.060, GFI = 0.843, AGFI = 0.82, NFI = 0.885, NNFI = 0.93, CFI = 0.94, IFI = 0.94, RFI = 0.97, PNFI = 0.81, and PGFI = 0.73. Each fitting index value in this study meets the suggested standards, and has a good model fit.

Research Model Verification

In this study, structural equation modeling was used for model validation, and all nine research hypotheses were supported. The results of the research model verification are as follows: Life hovering awareness has negative impacts on behavioral engagement (β = −0.25***; t = −3.32), emotional engagement (β = −0.24***; t = −3.32), and cognitive engagement (β = −0.19**; t = −2.56). Coursework hovering also has negative impacts on each engagement dimension as follows: behavioral engagement (β = −0.25**; t = −3.41), emotional engagement (β = −0.24***; t = −3.29), and cognitive engagement (β = −0.31***; t = −4.13). Meanwhile, behavioral engagement has positive impacts on the intention to continue attending cram school (β = 0.23***; t = 3.60), as do emotional engagement (β = 0.340***; t = 4.694) and cognitive engagement (β = 0.36***; t = 4.26), as shown in Figure 2.

The explanatory power of life hovering awareness and coursework hovering awareness to behavioral engagement is 12%, to emotional engagement it is 12%, and to cognitive engagement it is 13%. The explanatory power of behavioral engagement, emotional engagement, and cognitive engagement to the intention to continue attending cram schools is 37%. On the other hand, the effect size of cram school behavioral engagement (f2) is 0.14, that of emotional engagement (f2) is 0.13, cognitive engagement (f2) is 0.16, and there is an effect size of 0.58 for the intention to continue attending cram school (f2).

Discussion

Hovering behavior refers to helicopter parents paying too much attention to their children (Hong et al., 2015; Hwang et al., 2022). Participants in this study had a low awareness of life hovering (M = 2.30, SD = 0.78) and coursework hovering (M = 2.07, SD = 0.81). Behavioral engagement refers to engaging in learning activities, including paying attention to academic tasks, positive behavior, and attending school. Emotional engagement refers to the emotional attitude and recognition of the school and belongingness. Cognitive engagement refers to the self-regulation method of learning and using post-cognitive strategies (Fredricks et al., 2004; El-Sayad et al., 2021). The participants in this study were well aware of cram school behavioral engagement (M = 3.75, SD = 0.84), emotional engagement (M = 3.44, SD = 0.68), and cognitive engagement (M = 3.52, SD = 0.71). As continuity is a form of post-adoption behavior (Chang, 2013), participants in this study showed positive attitude in terms of their intention to continue attending cram school (M = 3.6, SD = 0.78). The results of the study showed that life hovering had negative impacts on the three types of tutoring engagement, so H1∼H3 were negatively verified; coursework hovering had negative impacts on the three types of tutoring engagement, so H4∼H6 were also negatively verified; however, the three types of tutoring engagement had positive impacts on continued attendance, so H7∼H9 were positively verified.

Helicopter parenting is accompanied by a series of negative consequences (Casillas et al., 2021), including subjective and academic ill effects (Schiffrin et al., 2014). In addition, research suggests that strong parenting beliefs do not help children engage in structured activities (Schiffrin et al., 2015). Helicopter parenting negatively affects child development in such aspects as emotion and learning development (Kwon et al., 2017). Hong et al. (2015) confirmed that learners with higher awareness of hovering behaviors have weaker learning situations and are more prone to procrastination. Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012) also pointed out that the more parents are involved in their children’s daily life, the less their children will engage in school, whereas Schiffrin and Liss (2017) indicated in their study that helicopter parenting correlates with poor learning motivation. In addition, past research has found that harsh parenting, a form of negative parenting, may have a negative impact on learning engagement (Zhang and Yue, 2021). From the above literature, it can be said that hovering behavior has negative impacts on cram school engagement. The results of this study display that two types of hovering behavior awareness are negatively correlated with three kinds of English cram school engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive).

Engagement is the act of meeting internal and external expectations (Guthrie et al., 2013). In recognition of the importance of student engagement to the current and future success of students (Cents-Boonstra et al., 2021). Attending cram schools might help solve students’ problems and further increase the level of their engagement (Marques, 2019). Researchers have also pointed out that emotional engagement is an important indicator of willingness prediction (Shuck et al., 2015). For example, the degree of school internship courses engagement positively affects intention to continue participating (Tseng and Chen, 2015). Other studies have also confirmed that the degree of participants’ engagement has positive impacts on creating value and the intention to participate (Algharabat, 2018). In Costley and Lange’s (2017) study on digital learning videos, learners’ engagement level positively affected their future behavioral willingness. The above literature shows that the level of engagement and continued participation are positively correlated with each other. The results of this study also show a positive correlation between three types of cram school engagement and the intention to continue attending cram school.

Conclusion

Attending cram school has long been a trend in ethnic Chinese culture areas, including Taiwan. A high percentage of Taiwanese students have experience of their parents arranging for them to attend cram school during their school life. Since attending cram school is a universal routine, it is of great importance to understand cram school engagement status. Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012) indicated that the more parents are involved in their children’s daily life, the less their children would engage in school. The results of this study show that hovering behavior awareness is negatively related to cram school engagement, whereas cram school engagement is positively related to the intention to continue attending cram school. This represents that helicopter parenting negatively affects the situation of learners’ cram school engagement as well as the intention to continue attending cram school, and this outcome affects the effectiveness of cram schooling.

Implications

Parenting has great impacts on adolescent behaviors. In a society with a low birth rate such as Taiwan, parents are often overly involved in their children’s lives (Hong et al., 2015). Since studies have proved the negative impacts helicopter parenting has on learners and cram school education, what methods parents should adopt to nurture their children is a critical issue.

Studies have also shown that students’ learning situation can indeed be ameliorated by enhancing their engagement level (Bryson and Hand, 2007). Thus, both parents and cram school teachers, especially in regions where cram schooling culture prevails, should pay attention to learners’ engagement situation in school to help them maintain intention to continue attending cram school, in order to make cram schooling effective.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study validated the relationship between helicopter parenting and tutoring engagement, it is not known how tutoring engagement affect the real academic performance in their own schools. However, students attended English cram schools were from different levels of academic performance, it is difficult to evaluate the effect of learning achievement based on their school levels. Therefore, a follow-up study can be applied to further investigate the specific factors that attending English cram schools contribute to their effect of English learning on regular schools.

Learners’ knowledge growth in specific topics can be a predictive indicator of learning behavior (Carpenter et al., 2016). However, the relationship between learners’ cram school engagement and school behaviors was not discussed in this study. Research regarding this topic can be conducted in the future.

In addition, this was a confirmatory study. The hovering behavior awareness and cram school engagement of cram school attendees of different educational systems or ages were not covered in this study. However, this is also an important issue to be discussed in terms of cram school education. Thus, this topic could be further developed and analyzed in the upcoming studies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

Y-JH, J-CH, J-HY, P-HC, and Y-JCL: concept and design and drafting of the manuscript. J-CH, J-HY, and Y-JCL: acquisition of data and statistical analysis. P-HC and L-PM: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the “Chinese Language and Technology Center” of National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU) from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abedi, G., Rostami, F., and Nadi, A. (2015). Analyzing the dimensions of the quality of life in hepatitis B patients using confirmatory factor analysis. Glob. J. Health Sci. 7, 22–31. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n7p22

Algharabat, R. S. (2018). The role of telepresence and user engagement in co-creation value and purchase intention: online retail context. J. Intern. Commer. 17, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2017.1422667

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Awang, Z. (2015). Sem Made Simple, a Gentle Approach to Learning Structural Equation Modeling. Kajang: MPWS Rich.

Bae, C. L., and DeBusk-Lane, M. (2019). Middle school engagement profiles: implications for motivation and achievement in science. Learn. Individ. Differ. 74:101753. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101753

Bown, J., and White, C. J. (2010). Affect in a self-regulatory framework for language learning. System 38, 432–443. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2010.03.016

Bray, M. (2011). The Challenge of Shadow Education: Private Tutoring and its Implications for Policy Makers in the European Union Brussels. Brussels: European Commission.

Bray, M. (2017). Schooling and its supplements: changing global patterns and implications for comparative education. Comp. Educ. Rev. 61, 469–491. doi: 10.1086/692709

Bray, M., and Lykins, C. (2012). Shadow Education: Private Supplementary Tutoring and its Implications for Policy Makers in Asia. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong, and Asian Development Bank.

Bryson, C., and Hand, L. (2007). The role of engagement in inspiring teaching and learning. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 44, 349–362. doi: 10.1080/14703290701602748

Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., and Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 1051–1095. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09585-3

Carpenter, S. K., Lund, T. J., Coffman, C. R., Armstrong, P. I., Lamm, M. H., and Reason, R. D. (2016). A classroom study on the relationship between student achievement and retrieval-enhanced learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 353–375. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9311-9

Carr, V. M., Francis, A. P., and Wieth, M. B. (2021). The relationship between helicopter parenting and fear of negative evaluation in college students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 30, 1910–1919. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01999-z

Casillas, L. M., Elkins, S. R., Walther, C. A., Schanding, G. T. Jr., and Short, M. B. (2021). Helicopter parenting style and parental accommodations: the moderating role of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Fam. J. 29, 245–255. doi: 10.1177/1066480720961496

Cents-Boonstra, M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Denessen, E., Aelterman, N., and Haerens, L. (2021). Fostering student engagement with motivating teaching: an observation study of teacher and student behaviours. Res. Pap. Educ. 36, 754–779. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2020.1767184

Chang, C. C. (2013). Examining users’ intention to continue using social network games: a flow experience perspective. Telematics Inform. 30, 311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2012.10.006

Chang, C. H. (2019). Effects of private tutoring on English performance: evidence from senior high students in Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 68, 80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.05.003

Chen, W. W., Yang, X., and Jiao, Z. (in press). Authoritarian parenting, perfectionism, and academic procrastination. Educ. Psychol. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2021.2024513

Chugh, S. (2011). Dropout in Secondary Education: A Study of Children Living in Slums of Delhi. New Delhi: National University of Educational Planning and Administration.

Chung, I. F. (2013). Crammed to learn English: what are learners’ motivation and approach? Asia Pacif. Educ. Res. 22, 585–592. doi: 10.1007/s40299-013-0061-5

Cor, M. K. (2016). Trust me, it is valid: research validity in pharmacy education research. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 8, 391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.02.014

Costley, J., and Lange, C. H. (2017). Video lectures in e-learning: effects of viewership and media diversity on learning, satisfaction, engagement, interest, and future behavioral intention. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 14, 14–30. doi: 10.1108/ITSE-08-2016-0025

Dewaele, J. M. (2005). Investigating the psychological and the emotional dimensions in instructed language learning: obstacles and possibilities. Modern Lang. J. 89, 367–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00311.x

Diseth, A., Pallesen, S., Brunborg, G. S., and Larsen, S. (2010). Academic achievement among first semester undergraduate psychology students: the role of course experience, effort, motives and learning strategies. High. Educ. 59, 335–352. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9251-8

Dumont, D. E. (2021). Facing adulthood: helicopter parenting as a function of the family projection process. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 35, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2019.1601049

Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Nagy, G., and Nagengast, B. (2014). Quality of parental homework involvement: predictors and reciprocal relations with academic functioning in the reading domain. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 144–161. doi: 10.1037/a0034100

El-Sayad, G., Md Saad, N. H., and Thurasamy, R. (2021). How higher education students in Egypt perceived online learning engagement and satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comput. Educ. 8, 527–550. doi: 10.1007/s40692-021-00191-y

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

Gardner, R. C., and MacIntyre, P. D. (1993). On the measurement of affective variables in second language learning. Lang. Learn. 43, 157–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1992.tb00714.x

Garn, A. C., Simonton, K., Dasingert, T., and Simonton, A. (2017). Predicting changes in student engagement in university physical education: application of control-value theory of achievement emotions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 29, 93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.12.005

Gherardi, S. (2018). “A practice-based approach to safety as an emergent competence,” in Beyond Safety Training, eds C. Bieder, C. Gilbert, B. Journé, and H. Laroche (Berlin: Springer), 11–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-65527-7_2

Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Stoeger, H., and Hall, N. C. (2010). Antecedents of everyday positive emotions: an experience sampling analysis. Motiv. Emot. 34, 49–62. doi: 10.1007/s11031-009-9152-2

Granja, R., da Cunha, M. I. P., and Machado, H. (2015). Mothering from prison and ideologies of intensive parenting: enacting vulnerable resistance. J. Fam. Issues 36, 1212–1232. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14533541

Green, S. B., and Salkind, N. (2004). Using Spss for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and Understanding Data, 4th Edn. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Guill, K., and Lintorf, K. (2019). Private tutoring when stakes are high: insights from the transition from primary to secondary school in Germany. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 65, 172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.08.001

Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., and Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents. Read. Res. Q. 48, 9–26. doi: 10.1002/rrq.035

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edn. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Han, Y., and Lee, S. (2016). Heterogeneous relationships between family private education spending and youth academic performance in Korea. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 69, 136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.08.001

Hong, J. C., Hwang, M. Y., Kuo, Y. C., and Hsu, W. Y. (2015). Parental monitoring and helicopter parenting relevant to vocational student’s procrastination and self-regulated learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 42, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.003

Hong, J. C., Hwang, M. Y., Liu, M. C., Ho, H. Y., and Chen, Y. L. (2014). Using a “prediction–observation–explanation” inquiry model to enhance student interest and intention to continue science learning predicted by their Internet cognitive failure. Comput. Educ. 72, 110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.004

Hwang, W., Jung, E., Fu, X., Zhang, Y., Ko, K., Lee, S. A., et al. (2022). Typologies of helicopter parenting in American and Chinese young-adults’ game and social media addictive behaviors. J. Child. Fam. Stud. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-02213-w

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., and McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 44, 486–507. doi: 10.1177/0049124114543236

King, R. B., and Gaerlan, M. J. M. (2014). High self-control predicts more positive emotions, better engagement, and higher achievement in school. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 29, 81–100. doi: 10.1007/s10212-013-0188-z

Kuan, P. Y. (2011). Effects of cram schooling on mathematics performance: evidence from junior high students in Taiwan. Comp. Educ. Rev. 55, 342–368. doi: 10.1086/659142

Kwon, K. A., Yoo, G., and De Gagne, J. C. (2017). Does culture matter? A qualitative inquiry of helicopter parenting in Korean American college students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 1979–1990. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0694-8

Lawson, M. A., and Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 432–479. doi: 10.3102/0034654313480891

Lee, H., Lim, C., and Min, K. (2010). Effects of coaching on college admissions. J. Econ. Finance Educ. 19, 151–175.

Liu, J. (2012). Does cram schooling matter? Who goes to cram schools? Evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 32, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.01.014

Lo, C. F., and Lin, C. H. (2020). The impact of English learning motivation and attitude on well-being: cram school students in Taiwan. Future Internet 12:131. doi: 10.3390/fi12080131

Luan, L., Hong, J. C., Cao, M., Dong, Y., and Hou, X. (2020). Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: a structural equation model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 28, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1855211

Luo, W., Ng, P. T., Lee, K., and Aye, K. M. (2016). Self-efficacy, value, and achievement emotions as mediators between parenting practice and homework behavior: a control-value theory perspective. Learn. Individ. Differ. 50, 275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.07.017

Marques, J. (2019). Creativity and morality in business education: toward a trans-disciplinary approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 17, 15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2018.11.001

McCormick, A., Kinzie, J., and Gonyea, R. M. (2013). Bridging research and practice to improve the quality of undergraduate education. High. Educ. Handb. Theory Res. 28, 47–92. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5836-0_2

Muro, A., Soler, J., Cebolla, À, and Cladellas, R. (2018). A positive psychological intervention for failing students: does it improve academic achievement and motivation? A pilot study. Learn. Motiv. 63, 126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2018.04.002

Padilla-Walker, L. M., and Nelson, L. J. (2012). Black hawk down? Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. J. Adolesc. 35, 1177–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.007

Pearce, S., Power, S., and Taylor, C. (2018). Private tutoring in Wales: patterns of private investment and public provision. Res. Pap. Educ. 33, 113–126. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2016.1271000

Pekrun, R., and Stephens, E. J. (2010). Achievement emotions: a control-value approach. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 4, 238–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00259.x

Pomerantz, A. (2019). Negotiating the terms of engagement: humor as a resource for managing interactional trouble in after-school tutoring encounters. Linguist. Educ. 49, 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2018.12.001

Price, L., Richardson, J. T. E., Robinson, B., Ding, X., Sun, X., and Han, C. (2011). Approaches to studying and perceptions of the academic environment among university students in China. Asia Pacif. J. Educ. 2, 159–175. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2011.566996

Ryu, S., and Lombardi, D. (2015). Coding classroom interactions for collective and individual engagement. Educ. Psychol. 50, 70–83. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2014.1001891

Sabbagh, M. A., Koenig, M. A., and Kuhlmeier, V. A. (2017). Conceptual constraints and mechanisms in children’s selective learning. Dev. Sci. 20:e12415. doi: 10.1111/desc.12415

Schiffrin, H. H., Godfrey, H., Liss, M., and Erchull, M. J. (2015). Intensive parenting: does it have the desired impact on child outcomes? J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 2322–2331. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0035-0

Schiffrin, H. H., and Liss, M. (2017). The effects of helicopter parenting on academic motivation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 1472–1480. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0658-z

Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., and Tasher, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. J. Child Fam. Stud. 23, 548–557. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3

Shuck, B., Zigarmi, D., and Owen, J. (2015). Psychological needs, engagement, and work intentions: a Bayesian multi-measurement mediation approach and implications for HRD. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 39, 2–21. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-08-2014-0061

Sinatra, G. M., Heddy, B. C., and Lombardi, D. (2015). The challenges of defining and measuring student engagement in science. Educ. Psychol. 50, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2014.1002924

Stastný, V. (2016). Private supplementary tutoring in the Czech Republic. Eur. Educ. 48, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/10564934.2016.1147006

Trautwein, U., Ludtke, O., Kastens, C., and Koller, O. (2006). Effort on homework in grades 5 through 9: development, motivational antecedents, and the association with effort on classwork. Child Dev. 77, 1094–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00921.x

Tseng, L. Y., and Chen, Y. C. (2015). A study of the relationship between self-directed learning and job retention among medical interns with job involvement as the intervening variable. J. Healthcare Manag. 16, 1–22. doi: 10.6174/JHM2015.16(1).1

Valentine, K., Smyth, C., and Newland, J. (2019). ‘Good enough’ parenting: negotiating standards and stigma. Int. J. Drug Policy 68, 117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.07.009

van Ingen, D. J., Freiheit, S. R., Steinfeldt, J. A., Moore, L. L., Wimer, D. J., Knutt, A. D., et al. (2015). Helicopter partenting: the effect of an overbearing caregiving style on peer attachment and self-efficacy. J. Coll. Couns. 18, 7–20. doi: 10.1002/j.21

Wang, C., and Wang, L. (2021). The mathematics teacher in shadow education: a new area of focus in teacher education. J. Math. Teacher Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10857-021-09522-3

Wang, J., and Wu, Y. (2021). Private supplementary education and Chinese adolescents’ development: the moderating effects of family socioeconomic status. J. Community Psychol. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22774

Weston, R., and Gore, P. A. Jr. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Couns. Psychol. 34, 719–751. doi: 10.1177/0011000006286345

Yung, K. W. H. (2020b). Problematising students’ preference for video-recorded classes in shadow education. Educ. Stud. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1814697

Yung, K. W. H. (2020a). Comparing the effectiveness of cram school tutors and schoolteachers: a critical analysis of students’ perceptions. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 72:102141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102141

Yung, K. W. H., and Chiu, M. M. (2020). Factors affecting secondary students’ enjoyment of English private tutoring: student, family, teacher, and tutoring. Asia Pacif. Educ. Res. 29, 509–518. doi: 10.1007/s40299-020-00502-4

Zhang, J., and Yue, P. (2021). The influence of harsh parenting on middle school students’ learning engagement: the mediating effect of perceived self-efficacy in managing negative affect and the moderating effect of mindfulness. Psychology 12, 1473–1489. doi: 10.4236/psych.2021.1210093

Zhang, Y., Dang, Y., He, Y., Ma, X., and Wang, L. (2021). Is private supplementary tutoring effective? A longitudinally detailed analysis of private tutoring quality in China. Asia Pacif. Educ. Rev. 22, 239–259. doi: 10.1007/s12564-021-09671-3

Appendix

Keywords: English cram schools, helicopter parenting, learning engagement, mummy’s child, tutoring

Citation: Ho Y-J, Hong J-C, Ye J-H, Chen P-H, Ma L-P and Chang Lee Y-J (2022) Effects of Helicopter Parenting on Tutoring Engagement and Continued Attendance at Cram Schools. Front. Psychol. 13:880894. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.880894

Received: 22 February 2022; Accepted: 11 March 2022;

Published: 13 April 2022.

Edited by:

Jesús-Nicasio García-Sánchez, Universidad de León, SpainReviewed by:

Lidon Moliner, University of Jaume I, SpainFrancisco Alegre, University of Jaume I, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Ho, Hong, Ye, Chen, Ma and Chang Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jian-Hong Ye, a2ltcG8zMDEwN0Bob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Po-Hsi Chen, Y2hlbnBoQG50bnUuZWR1LnR3

Ya-Jiuan Ho

Ya-Jiuan Ho Jon-Chao Hong

Jon-Chao Hong Jian-Hong Ye

Jian-Hong Ye Po-Hsi Chen

Po-Hsi Chen Liang-Ping Ma6

Liang-Ping Ma6