- 1Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, United States

- 2Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, United States

- 4Cook Children’s Medical Center, Fort Worth, TX, United States

- 5Children’s Hospital Orange County, Orange, CA, United States

- 6National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, United States

Background and Aims: End-of-life (EoL) discussions can be difficult for seriously ill adolescents and young adults (AYAs). Researchers aimed to determine whether completing Voicing My CHOiCES (VMC)—a research-informed advance care planning (ACP) guide—increased communication with family, friends, or health care providers (HCPs), and to evaluate the experience of those with whom VMC was shared.

Methods: Family, friends, or HCPs who the AYAs had shared their completed VMC with were administered structured interviews to assess their perception of the ACP discussion, changes in their relationship, conversation quality, and whether the discussion prompted changes in care. Open-ended responses underwent thematic analysis.

Results: One-month post-completion, 65.1% of AYA had shared VMC completion with a family member, 22.6% with a friend, and 8.9% with an HCP. Among a sample of respondents, family (47%) and friends (33%) reported a positive change in their relationship with the AYA. Participant descriptions of the experience fell into five themes: positive experience (47%), difficult experience (44%), appreciated a guide to facilitate discussion (35%), provided relief (21%), and created worry/anxiety (9%). Only 1 HCP noted a treatment change. Family (76%), friends (67%), and HCP (50%) did not think the AYA would have discussed EoL preferences without completing VMC.

Conclusions: VMC has potential to enhance communication about ACP between AYA and their family and friends, though less frequently with HCPs. Participants reported a positive change in their relationship with the AYA after discussing VMC, and described experiencing the conversation as favorable, even when also emotionally difficult.

Introduction

The number of AYAs living with serious illnesses such as cancer is growing globally (Viner et al., 2011; Cohen and Patel, 2014; GBD 2019 Adolescent Young Adult Cancer Collaborators, 2022). In 2020, an estimated 90,000 adolescents and young adults (AYA) were diagnosed with cancer in the United States (Haines et al., 2021). For many, death is an inevitable outcome of their disease, making advance care planning (ACP) a critical component of care (Brown and Sourkes, 2006; DeCourcey et al., 2021). It is difficult for AYAs, their families, and providers to think about or talk about death and dying. The presence of a life-threatening illness adds a multitude of challenges to what is already a difficult period of life, when emerging adults strive to define themself outside of the context of their family and envision their own future (Brown and Sourkes, 2006). Further, disease burden at this age can negatively impact financial security, body image, educational and work trajectories, relationships with spouse/significant other, and plans for having children (Maslow et al., 2011; Warner et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2017). In addition, young adults with advanced cancer have reported significant psychological distress in the form of grief (Jacobsen et al., 2010) and suicidal ideation (Walker et al., 2008).

Effective end-of-life (EoL) discussions are critical for AYAs, especially in the event of disease progression or a poor prognosis, given both the medical challenges and psychosocial risk factors involved (Sansom-Daly et al., 2020). ACP documents and advance directives provide patients with the opportunity to express their preferences for care. These directives can help families and health care agents make informed decisions, alleviate distress (Mack et al., 2005), avoid decisional regret (DeCourcey et al., 2019; Lichtenthal et al., 2020), and potentially improve the patient’s quality of life by respecting their religious, cultural, and familial values and beliefs (Jankovic et al., 2008; Barfield et al., 2010; Kane et al., 2011; Wiener et al., 2012). Families have expressed significant interest in ACP, with parents indicating that the opportunity for these discussions has been a poorly met need (Durall et al., 2012; Lotz et al., 2013; DeCourcey et al., 2019; Hein et al., 2020; Orkin et al., 2020). Research has shown that parents of seriously ill children desire earlier, ongoing opportunities to address ACP with their child’s providers (DeCourcey et al., 2019; Orkin et al., 2020). However, many pediatric providers report a lack of ACP communication training (Dellon et al., 2010; Durall et al., 2012; Lotz et al., 2013; Heckford and Beringer, 2014). Unfortunately, when ACP discussions do take place, they often occur too late and typically during an acute clinical crisis, when there is insufficient time to consider individual goals and values (Davidson et al., 2007; Brudney, 2009; Durall et al., 2012; Snaman et al., 2020; Pennarola et al., 2021).

The literature has clearly demonstrated the need and desire for ACP intervention in this population (Weaver et al., 2015; Kirch et al., 2016), as well as the barriers to initiating ACP (Wolfe et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2012; Kassam et al., 2013; Pinkerton et al., 2018). Studies have shown that less than 3% of AYAs participate in EoL planning conversations without clinician prompting (Lyon et al., 2004, 2014; Liberman et al., 2014; Carr et al., 2021). Data exploring the experience of the family members, friends, and health care providers who are involved in ACP conversations with AYA are limited. Adolescents and families who participated in family-centered ACP found the conversations to be worthwhile (Dallas et al., 2016), notably with a greater understanding of EoL wishes (Madrigal et al., 2017). In a robust multi-site, assessor-blinded, parallel-group, randomized control trial (FACE pACP), ACP surrogates were eight times more likely than controls to have an excellent understanding of adolescent patients’ treatment preferences (Lyon et al., 2018). In another ACP trial, families had more positive appraisals of their caregiving, than families who did not have these conversations (Baker et al., 2020).

Novel tools and interventions are needed to facilitate ACP discussions between AYA and their family members, friends and HCPs (Snaman et al., 2020). Voicing My CHOiCES (VMC), a research informed ACP guide (Wiener et al., 2012; Zadeh et al., 2015), has been shown to both decrease anxiety around EoL planning and enhance communication with both family members and friends (Wiener et al., 2021). This study adds to the literature by providing the perspectives or outcomes on behalf of the family member, friend, or HCP post completion of an ACP document by an AYA. In this study we aimed to gain understanding of the experience of the family member, friend, or HCP pertaining to the ACP discussion, changes in their relationship, conversation quality, and whether the discussion prompted changes in care.

Materials and Methods

Study Recruitment and Enrollment

As part of a larger study, AYAs aged 18–39 years receiving cancer-directed therapy or treatment for another chronic medical illness at one of seven study sites were enrolled on a larger study examining psychosocial outcomes after completing VMC. For this sub-study, participants included the family members, friends, or HCPs with whom the AYAs initiated a conversation with about their ACP preferences following completion of the VMC guide. Sub-study participants were contacted by phone, with permission from the AYA by whom they had been nominated. The NIH Institutional Review Board approved this protocol, and the study was then approved by the IRB at each of the participating sites. Data was collected between 2015–2019.

Study Procedures

AYAs were contacted one-month post-VMC completion to seek permission to contact any family member, friend, or HCP the AYA had shared preferences with. Informed consent was subsequently obtained and each participant was then administered a one-time structured interview, including both quantitative and open-ended questions. Development of the interview was based on shared clinical expertise of the primary study team, familiarity with the VMC guide, and knowledge of the relevant literature and gaps therein (Wiener et al., 2012, 2021; Dallas et al., 2016; Sansom-Daly et al., 2020). Specifically, the interview assessed the communication they had about ACP with the AYA, as well as perceived changes in their relationship, the quality of the conversation, and whether changes in care were made following the discussion. Interviews were conducted either in person or by phone and responses were written verbatim by the interviewer. No audio or video recordings were collected. Each interview took approximately 15 min to complete. See Supplemental Data Sheet 1 for the interview guide.

Interviews were conducted by a trained study team member, including psychologists, social workers, nursing study coordinators, or graduate students. Procedure training consisted of an in-person, virtual or phone session with the sponsor site (SZB or LW) where a training manual was reviewed in detail and sample case scenarios were discussed.

Analysis

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using a realist approach to inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Maxwell, 2012). Coders (SZB, AF, LW) independently read and re-read the data, identifying initial codes, capturing novel content, and searching for potential themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Miles et al., 2014). The coders then met as a group to review codes, and to examine, refine and define themes (Macqueen et al., 1998). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion. Free-text responses were then coded in parallel (Malterud, 2001). The authors reviewed and discussed the findings and summarized the data.

Results

One month after completing the baseline measure and reviewing the VMC tool, 129 participants answered the follow up questions about talking with family members, 124 about talking with friends, and 124 answered the question about talking with HCP. Overall, 84 (65.1%) of participants had shared what they wrote in VMC with a family member and 11 (8.9%) shared with an HCP (Wiener et al., 2021). Twenty-eight participants (22.6%) shared what they wrote in VMC with a friend. Of those with whom document completion was shared, we interviewed 40 (47.6%) family members, 6 (21.4%) friends, and 5 (45.5%) providers about their experience with this conversation. Of note, three interviews (two family members and one provider) were discontinued when the participant indicated the AYA had not shared what they had written in VMC. The remaining analyses are based on interviews with the 48 participants who engaged in such a conversation, according to both the AYA and the study participant.

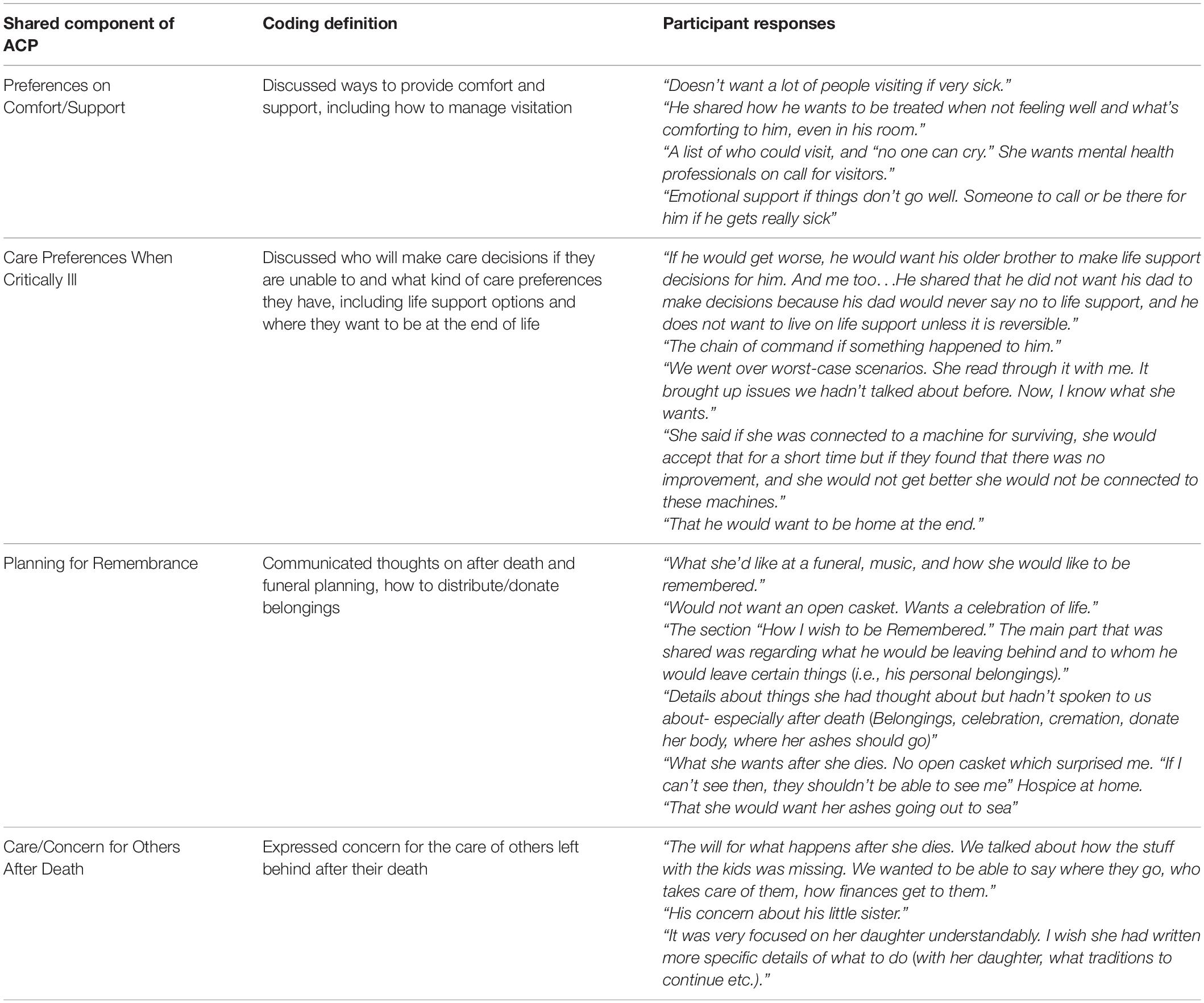

ACP Discussions Had Pre- and Post-VMC

For 17 (42.5%) of the 40 family members interviewed, their first ACP conversation was held post-AYA VMC completion. Of the friends interviewed, 4 of the 6 friends (66.7%) were from AYAs who first spoke to their friend after VMC. Of the five providers interviewed, 3 (60%) were from AYAs who only spoke to their HCP about ACP post-VMC. Twenty-nine (76.3%) family members, 4 friends (67%) and 2 HCP (40%) did not think the AYA would have talked to them about their EoL preferences without the study. When participants were asked “Can you tell me what part of the advance care planning process [the patient] shared with you,” four themes were revealed: preferences on comfort/support, care preferences when critically ill, planning for remembrance, and care/concern for others after death. Sample responses are provided in Table 1. One HCP (20%) noted a treatment change following the discussion (e.g., medication changes for symptom management).

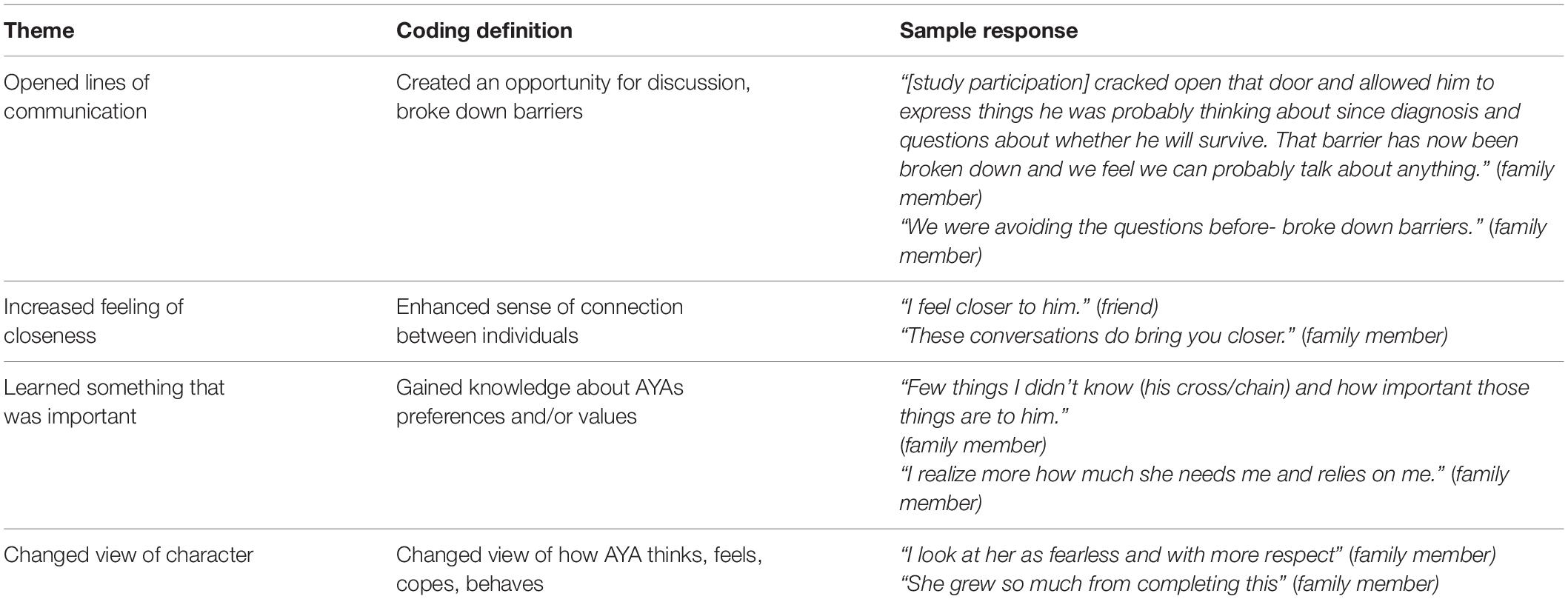

Changes in Relationship

Forty-seven percent of family members (n = 19) and 33% of friends (n = 2) reported a change in their relationship with the AYA following the discussion. If a change in their relationship was reported, participants were then asked to describe the change. Four themes were found: the conversation opened lines of communication, increased feelings of closeness, learned something that was important, and changed view of character (i.e., how the AYA thinks, feels or copes). Sample responses are provided in Table 2.

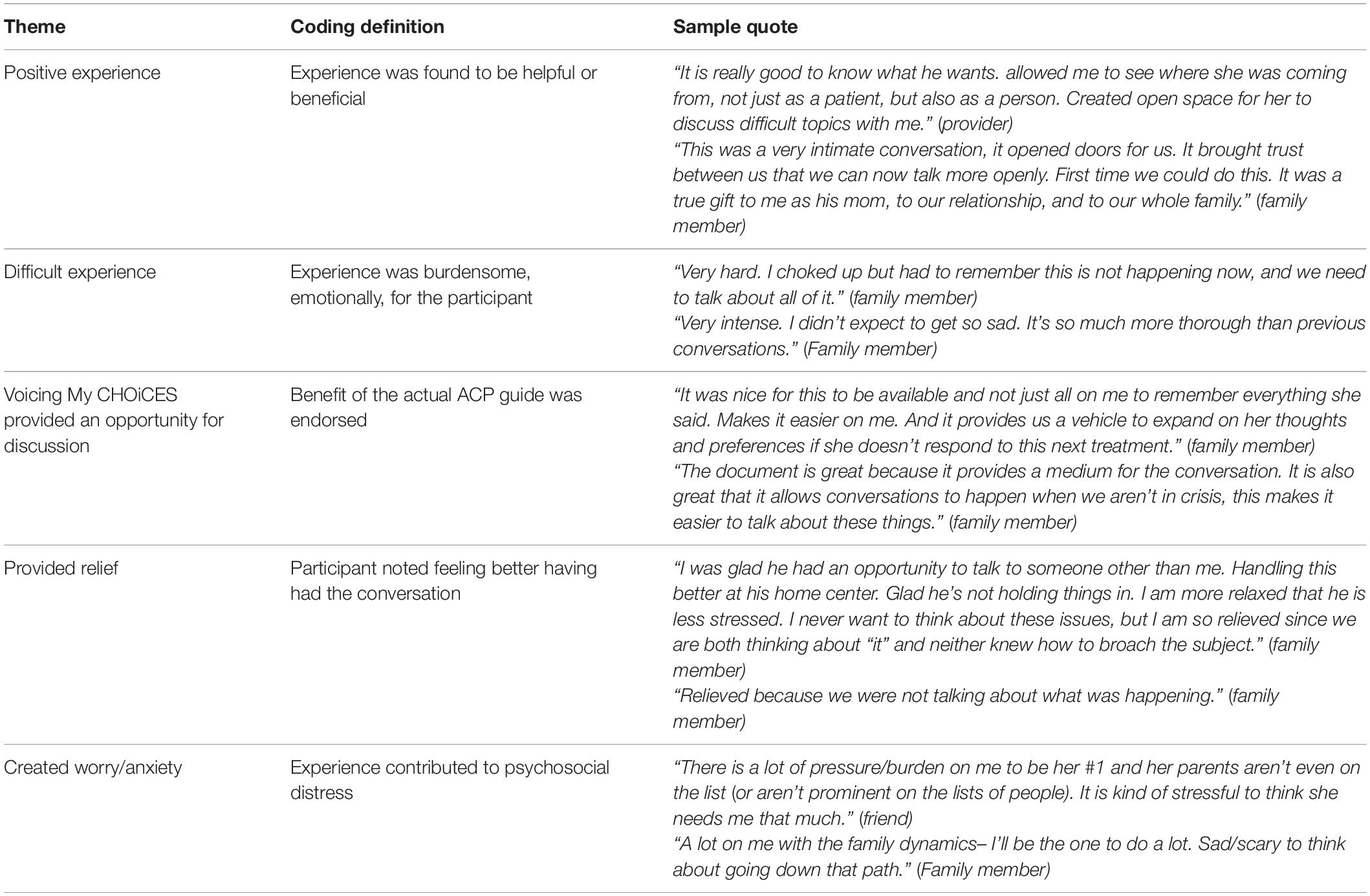

How the ACP Conversation Was Experienced

Family members, friends and HCPs were also asked, “Can you tell us what this experience was like for you?” What emerged illustrated both benefit and burden. Themes that represented benefit included the conversation being a positive experience, appreciating a guide to facilitate a deeply honest conversation and the conversation provided relief. Themes that represented a burden included experiencing the conversation as emotionally difficult and that it created worry/anxiety. While some participants described a sense of burden from the discussion (e.g., difficult experience or created worry/anxiety), the majority described benefit (e.g., positive experience, appreciated guide, provided relief). Of those participants who reported a burdensome experience most indicated finding benefit despite the burden (e.g., painful to have the discussion but grateful to know what their EoL preferences are). Select participant responses are provided in Table 3.

Discussion

ACP discussions have been associated with a range of positive outcomes, including increased congruence between treatment preferences expressed by AYAs and their caregivers and increased likelihood that these preferences will be honored at the EoL. Yet, AYAs and their caregivers find it difficult to engage in these conversations (Jimenez et al., 2018). For the majority of study participants, completing an age-appropriate ACP guide prompted a first conversation regarding EoL preferences with a family member. To a lesser degree, it also prompted a first conversation with a friend. Notably, many of these conversations covered more than just EoL preferences. Participants described having deeply honest discussions about hopes, fears, and relationships. These findings support using VMC to enhance communication about EoL preferences, adding to the existing literature on the myriad benefits of such interventions (Feraco et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2020; Laronne et al., 2021).

In addition to families requiring assistance in navigating these discussions (Kenney et al., 2021), we found few AYAs shared what they wrote in VMC with their HCP. Challenges surrounding ACP conversations with HCPs include provider discomfort and a lack of training and resources (Dellon et al., 2010; Durall et al., 2012; Lotz et al., 2013; Heckford and Beringer, 2014). In fact, most family members and friends, as well as half of the HCP in our study, did not think the AYA would have talked to them about their EoL preferences without having completed VMC. This highlights the need for training on how to introduce ACP more comfortably with AYAs so that goals regarding current and future care can be addressed. While just one of five HCPs noted a treatment change following the discussion, these numbers may reflect the limited number of HCPs who the AYAs engaged in an ACP conversation. This is consistent with current literature suggesting patients and their family members will wait for the topic to be raised by their clinician (Clayton et al., 2005; Brighton and Bristowe, 2016). Research focused on training clinicians and preparing patients and families to engage in high-quality discussions using an age-appropriate ACP guide, like VMC, may help to achieve higher quality EoL care.

The specifics of what the AYA shared following completion of VMC was varied and included their preferences on mechanisms of comfort and support, how aggressively they would like to be treated if there was little to no chance of recovery, planning for how they would like to be remembered, and care/concern for others after death. These conversations were well received and described as being beneficial to both parties, despite being emotionally difficult to initiate. Similar to extant literature (Aldridge et al., 2017; Hein et al., 2018; Weaver et al., 2021), participants in the current study recognized that communicating important EoL care preferences can help prepare for future situations and create a pathway to goal-concordant EoL care. Critical longitudinal data is needed to assess whether communicated preferences were honored after an AYAs death.

Other benefits from these conversations were also reported. Half of family members and a third of their friends reported a change in their relationship with the AYA. Changes were all self-reported to be positive. Additionally, when describing the overall experience of talking about ACP with the AYA, participants again highlighted benefit despite also being seen as burdensome. Many participants spoke to the value of the ACP conversations and the relief in having the discussion despite the stress of thinking about worst-case scenarios. These findings can reassure family members and HCPs of advantages associated with these courageous conversations.

Some limitations are important to note. First, many family members (n = 44, 53.7%), friends (n = 6, 54.5%), and HCP (n = 5, 50%) who AYAs shared their VMC completion with were not interviewed. For some, the AYA wasn’t comfortable with having the researcher reach out to them, and for others the family member, friend, or HCP was unreachable or declined participation. Second, interviews were only conducted with English-speaking individuals. Therefore, we do not know if the themes that were identified would be different from the family members, friends and HCP who were not interviewed. Third, we contacted AYA participants 1 month after they completed VMC. We don’t know if a conversation occurred with a family member, friend, or HCP about what they wrote in VMC past this point. Fourth, demographic data was not collected on the contact participants, so it is unknown whether one demographic was more represented than another. Last, the perspectives obtained might have been affected by recall bias. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first multisite study that describes the unique perspectives of family members, friends, and HCP after discussing ACP preferences with AYA post completion of VMC. The concurrent voices captured here poignantly illustrate the shared sense of burden and benefit AYAs and all those who care for them experience trying to communicate during the complex journey at the end of life.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by NIH Institutional Review Board: National Institutes of Health. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SB, LW, and MP contributed to the conception and design of the study. SB, LW, JT, PM, CH, and KZ collected the data. SB organized the database and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MG, SB, and AF performed the statistical analysis. LW wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Center for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the researchers involved at all collaborative sites, including Catriona Mowbry, Andrea Gross, Jessica Thompkins, Alice Hoeft, Cathy Elstner, Kristine Donovan, Jessamine Cadenas, Karen Long-Traynor, Denise Velazquez, Lisa Gennarini, Phoebe Souza, Shana Jacobs, and Katelyn MacDougall, as well as all the individuals who participated in this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.871042/full#supplementary-material

References

Aldridge, J., Shimmon, K., Miller, M., Fraser, L. K., and Wright, B. (2017). I can’t tell my child they are dying. Helping parents have conversations with their child. Arch. Dis. Child Educ. Pract. Educ. 102, 182–187. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311974

Baker, J. N., Thompkins, J., Friebert, S., Needle, J., Wang, J., Cheng, Y., et al. (2020). Effect of FAmily CEntered (FACE) advance care planning (ACP) on families’ appraisals of caregiving for their teen with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 38:e22533. doi: 10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.e22533

Barfield, R. C., Brandon, D. H., Thompson, J. A., Harris, N., Schmidt, M., and Docherty, S. L. (2010). Mind the child: using interactive technology to improve child involvement in decision making about life-limiting illness. Am. J. Bioeth. 10, 28–30. doi: 10.1080/15265161003632930

Braun, V., and Clarke, C. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psych. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brighton, L. J., and Bristowe, K. (2016). Communication in palliative care: talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgrad. Med. J. 92, 466–670. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133368

Brown, M., and Sourkes, B. (2006). The adolescent living with a life-threatening illness: psychological issues. Child. Pediatr. Palliat. Care Newslett. 5, 5–10.

Brudney, D. (2009). Choosing for another: beyond autonomy and best interests. Hastings Cent. Rep. 39, 31–37. doi: 10.1353/hcr.0.0113

Carr, K., Hasson, F., McIlfatrick, S., and Downing, J. (2021). Factors associated with health professionals decision to initiate paediatric advance care planning: A systematic integrative review. Palliat. Med. 35, 503–528. doi: 10.1177/0269216320983197

Clayton, J. M., Butow, P. N., and Tattersall, M. H. (2005). When and how to initiate discussion about prognosis and end-of-life issues with terminally ill patients. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 30, 132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.02.014

Cohen, E., and Patel, H. (2014). Responding to the rising number of children living with complex chronic conditions. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 186, 1199–1200. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141036

Dallas, R. H., Kimmel, A., Wilkins, M. L., Rana, S., Garcia, A., Cheng, Y. I., et al. (2016). Acceptability of family-centered advanced care planning for adolescents with HIV. Pediatrics 138:e20161854. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1854

Davidson, J. E., Powers, K., Hedayat, K. M., Tieszen, M., Kon, A., Shepard, E., et al. (2007). Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit. Care Med. 35, 605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067

DeCourcey, D., Partin, L., Revette, A., Bernacki, R., and Wolfe, J. (2021). Development of a stakeholder driven serious illness communication program for advance care planning in children, adolescents, and young adults with serious illness. J. Pediatr. 229, 247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.09.030

DeCourcey, D. D., Silverman, M., Oladunjoye, A., and Wolfe, J. (2019). Advance care planning and parent-reported end-of-life outcomes in children, adolescents, and young adults with complex chronic conditions. Crit. Care Med. 47, 101–108. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB

Dellon, E. P., Shores, M. D., Nelson, K. I., Wolfe, J., Noah, T. L., and Hanson, L. C. (2010). Caregiver perspectives on discussions about the use of intensive treatments in cystic fibrosis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 40, 821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.021

Durall, A., Zurakowski, D., and Wolfe, J. (2012). Barriers to conducting advance care discussions for children with life threatening conditions. Pediatrics 129, e975–e982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2695

Feraco, A. M., Brand, S. R., Mack, J. W., Kesselheim, J. C., Block, S. D., and Wolfe, J. (2016). Communication skills training in pediatric oncology: moving beyond role modeling. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 63, 966–972. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25918

GBD 2019 Adolescent Young Adult Cancer Collaborators (2022). The global burden of adolescent and young adult cancer in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Oncol. 23, 27–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00581-7

Haines, E. R., Lux, L., Smitherman, A. B., Kessler, M. L., Schonberg, J., Dopp, A., et al. (2021). An actionable needs assessment for adolescents and young adults with cancer: the AYA Needs Assessment & Service Bridge (NA-SB). Support Care Cancer 29, 4693–4704. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06024-z

Heckford, E., and Beringer, A. J. (2014). Advance care planning: challenges and approaches for pediatricians. J. Palliat. Med. 17, 1049–1053. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0374

Hein, K., Knochel, K., Zaimovic, V., Reimann, D., Monz, A., Heitkamp, N., et al. (2020). Identifying key elements for paediatric advance care planning with parents, healthcare providers and stakeholders: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 34, 300–308. doi: 10.1177/0269216319900317

Hein, K., Mona, A., Daxer, M., Heirkamp, N., Knochel, K., Jox, R., et al. (2018). Challenges in pediatric advance care discussions between health care professionals and parents of children with a life-limiting condition: A qualitative pilot study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 56:e131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.419

Jacobsen, J. C., Zhang, B., Block, S. D., Maciejewski, P. K., and Prigerson, H. G. (2010). Distinguishing symptoms of grief and depression in a cohort of advanced cancer patients. Death Stud. 34, 257–273. doi: 10.1080/07481180903559303

Jankovic, M., Spinetta, J. J., Masera, G., Barr, R. D., D’Angio, G. J., Epelman, C., et al. (2008). Communicating with the dying child: an invitation to listening – a report of the SIOP working committee on psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 50, 1087–1088. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21533

Jimenez, G, Tan, W. S., Virk, A. K., Low, C. K., Car, J., Ho, A. H. Y. (2018). Overview of systematic reviews of advance care planning: summary of evidence and global lessons. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 56, 436–459.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.05.016

Jin, M., An, Q., and Wang, L. (2017). Chronic conditions in adolescents. Exper. Ther. Med. 14, 478–482. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4526

Kane, J., Joselow, M., and Duncan, J. (2011). “Understanding the illness experience and providing anticipatory guidance,” in Textbook of Interdisciplinary Pediatric Palliative Care, eds J. Wolfe, P. Hinds, and B. Sourkes (Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc.), 30–40. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4377-0262-0.00004-9

Kassam, A., Skiadaresis, J., Habib, S., Alexander, S., and Wolfe, J. (2013). Moving toward quality palliative cancer care: parent and clinician perspectives on gaps between what matters and what is accessible. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 910–915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8936

Kenney, A. E., Bedoya, S. Z., Gerhardt, C. A., Young-Saleme, T., and Wiener, L. (2021). End of life communication among caregivers of children with cancer: A qualitative approach to understanding support desired by families. Palliat. Support. Care 19, 715–722. doi: 10.1017/S1478951521000067

Kirch, R., Reaman, G., Feudtner, C., Wiener, L., Schwartz, L. A., Sung, L., et al. (2016). Advancing a comprehensive cancer care agenda for children and their families: institute of Medicine Workshop highlights and next steps. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 398–407. doi: 10.3322/caac.21347

Laronne, A., Granek, L., Wiener, L., Feder-Bubis, P., and Golan, H. (2021). Some things are even worse than telling a child he is going to die: pediatric oncology healthcare professionals perspectives on communicating with children about cancer and end of life. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 69:e29533. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29533

Liberman, D. B., Pham, P. K., and Nager, A. L. (2014). Pediatric advance directives: parents’ knowledge, experience, and preferences. Pediatrics 134, e436–e443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3124

Lichtenthal, W. G., Roberts, K. E., Catarozoli, C., Schofield, E., Holland, J. M., Fogarty, J. J., et al. (2020). Regret and unfinished business in parents bereaved by cancer: A mixed methods study. Palliat. Med. 34, 367–377. doi: 10.1177/0269216319900301

Lin, B., Gutman, T., Hanson, C. S., Ju, A., Manera, K., Butow, P., et al. (2020). Communication during childhood cancer: systematic review of patient perspectives. Cancer 126, 701–716. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32637

Lotz, J. D., Jox, R. J., Borasio, G. D., and Führer, M. (2013). Pediatric advance care planning: A systematic review. Pediatrics 131, e873–e880. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2394

Lyon, M. E., Garvie, P. A., D’Angelo, L. J., Dallas, R. H., Briggs, L., Flynn, P. M., et al. (2018). Advance care planning and HIV symptoms in adolescence. Pediatrics 142:e20173869. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3869

Lyon, M. E., Jacobs, S., Briggs, L., Cheng, Y. I., and Wang, J. (2014). A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J. Adolesc. Health 54, 710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.206

Lyon, M. E., McCabe, M. A., Patel, K. M., and D’Angelo, L. J. (2004). What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. J. Adolesc. Health 35, .e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.009

Mack, J. W., Hilden, J. M., Watterson, J., Moore, C., Turner, B., Grier, H. E., et al. (2005). Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 9155–9161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010

Macqueen, K., McLellan, E., Kay, K., and Milstein, B. (1998). Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. Cult. Anthropol. 10, 31–36. doi: 10.1177/1525822x980100020301

Madrigal, V. N., MCabe, B., and Cecchini, C. (2017). The Respecting Choices Interview: Qualitative Assessment. San Francisco, CA: Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting.

Malterud, K. (2001). Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 358, 483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

Maslow, G. R., Haydon, A. A., Ford, C. A., and Halpern, C. T. (2011). Young adult outcomes of children growing up with chronic illness: an analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 165, 256–261. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.287

Maxwell, J. A. (2012). A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Orkin, J., Beaune, L., Moore, C., Weiser, N., Arje, D., Rapoport, A., et al. (2020). Toward an understanding of advance care planning in children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 145:e20192241. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2241

Pennarola, B. W., Fry, A., Prichett, L., Beri, A. E., Shah, N. N., and Wiener, L. (2021). Mapping the landscape of advance care planning in adolescents and young adults receiving allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A 5-year retrospective review. Transpl. Cell Ther. 28, e1–e164. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.12.007

Pinkerton, R., Donovan, L., and Herbert, A. (2018). Palliative care in adolescents and young adults with cancer-why do adolescents need special attention? Cancer J. 24, 336–341. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000341

Sansom-Daly, U. M., Wakefield, C. E., Patterson, P., Cohn, R. J., Rosenberg, A. R., Wiener, L., et al. (2020). End-of-life communication needs for adolescents and young adults with cancer: recommendations for research and practice. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 9, 157–165. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2019.0084

Smith, T. J., Temin, S., Alesi, E. R., Abernethy, A. P., Balboni, T. A., Basch, E. M., et al. (2012). American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161

Snaman, J., McCarthy, S., Wiener, L., and Wolfe, J. (2020). Pediatric palliative care in oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 954–962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02331

Viner, R. M., Coffey, C., Mathers, C., Bloem, P., Costello, A., Santelli, J., et al. (2011). 50-year mortality trends in children and young people: a study of 50 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries. Lancet 377, 1162–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60106-2

Walker, J., Waters, R. A., Murray, G., Swanson, H., Hibberd, C. J., Rush, R. W., et al. (2008). Better off dead: suicidal thoughts in cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 4725–4730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8844

Warner, E. L., Kent, E. E., Trevino, K. M., Parsons, H. M., Zebrack, B. J., and Kirchhoff, A. C. (2016). Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 122, 1029–1037. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29866

Weaver, M. S., Heinze, K. E., Kelly, K. P., Wiener, L., Casey, R. L., Bell, C. J., et al. (2015). Palliative care as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 62(Suppl. 5), S829–S833. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25695

Weaver, M. S., Wiener, L., Jacobs, S., Bell, C. J., Madrigal, V., Mooney-Doyle, K., et al. (2021). Weaver et al’s response to Morrison: advance directives/care planning: clear, simple, and wrong. J. Palliat. Med. 24, 8–10. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0486

Wiener, L., Bedoya, S., Battles, H., Sender, L., Zabokrtsky, K., Donovan, K. A., et al. (2021). Voicing their choices: advance care planning with adolescents and young adults with cancer and serious conditions. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951521001462

Wiener, L., Zadeh, S., Battles, H., Baird, K., Ballard, E., Osherow, J., et al. (2012). Allowing adolescents and young adults to plan their end-of-life care. Pediatrics 130, 897–905. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0663

Wolfe, J., Hammel, J. F., Edwards, K. E., Duncan, J., Comeau, M., Breyer, J., et al. (2008). Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1717–1723. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0277

Keywords: AYA family, friends, HCP, adolescent and young adult, advance care planning, EoL discussions, Voicing My CHOiCES, communication

Citation: Bedoya SZ, Fry A, Gordon ML, Lyon ME, Thompkins J, Fasciano K, Malinowski P, Heath C, Sender L, Zabokrtsky K, Pao M and Wiener L (2022) Adolescent and Young Adult Initiated Discussions of Advance Care Planning: Family Member, Friend and Health Care Provider Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 13:871042. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.871042

Received: 07 February 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 08 June 2022.

Edited by:

Ellen van der Plas, The University of Iowa, United StatesReviewed by:

Catarina Samorinha, University of Sharjah, United Arab EmiratesFlora Koliouli, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Copyright © 2022 Bedoya, Fry, Gordon, Lyon, Thompkins, Fasciano, Malinowski, Heath, Sender, Zabokrtsky, Pao and Wiener. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sima Z. Bedoya, c2ltYS5iZWRveWFAbmloLmdvdg==

Sima Z. Bedoya

Sima Z. Bedoya Abigail Fry1

Abigail Fry1 Mallorie L. Gordon

Mallorie L. Gordon Paige Malinowski

Paige Malinowski Lori Wiener

Lori Wiener