94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 28 July 2022

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868057

This article is part of the Research TopicSocial Sustainability at Work: A Key to Sustainable Development in BusinessView all 17 articles

Organizations and their leaders are challenged to assume a responsible behavior given the increase of corporate scandals and the deterioration of employee commitment. However, relatively few studies have investigated the impact of responsible leadership (RL) on employee commitment and the effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in this relationship. Using the social identity theory this article examined the mediating effect of CSR practices in the relationship between RL and affective organizational commitment (AOC). Data collection was done through a paper survey completed by 309 full-time Colombian employees. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the data. The results showed that CSR fully mediated the influence of RL on AOC. Thus, RL is an effective mechanism to develop CSR practices that in turn increase the levels of AOC of employees.

Corporate scandals and managerial misconduct have increased the need to reflect on the ethics and morality of corporate leaders (Voegtlin et al., 2012). Thus, there is a need to explain how those making the decisions in organizations impact corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices (Voegtlin, 2016). Because society has been losing trust in companies due to high levels of corruption, damage to stakeholders and the deterioration of natural resources it is said that we need a new conceptualization of the responsibilities of leaders (Patzer et al., 2018). Moreover, irresponsible leadership has been found to deteriorate the organizational commitment of employees (Boddy et al., 2010). These conditions suggest that society and employees demand a more responsible behavior on the part of companies and their leaders. To contribute to these issues, this research suggests that companies should promote a responsible leadership (RL) style in their managers as this favors the deployment of CSR practices that in turn increase the level of affective organizational commitment (AOC) of their employees.

On the other hand, the increase in environmental problems and the growing demands of stakeholders toward companies call for the redefinition of the responsibilities of their leaders (Maak and Pless, 2006). In the same way, it has been pointed out that companies must assume their social and environmental responsibilities (Scherer and Palazzo, 2011; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012). For these reasons, the need to develop responsible leaders has been indicated (Maak and Pless, 2009; Voegtlin, 2016).

Despite businesses efforts to find effective ways to incorporate CSR into their activities, research on the internal determinants of CSR, such as RL style, is limited (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012). Relatively few studies have investigated the relationship of RL with the psychological states of employees (Miska and Mendenhall, 2018). In particular, the association between RL and AOC, as well as the mechanisms that could explain this relationship, need further investigation (Haque and Caputi, 2017; Mousa, 2017). In this sense it has been argued that RL has a positive impact on AOC because employees will try to imitate responsible leaders’ behaviors as they give a sense of purpose and direction (Voegtlin et al., 2020). It has also been argued that leadership and CSR are personal and organizational factors considered key determinants of AOC (Meyer and Allen, 1991; Avolio et al., 2004; Rodrigo et al., 2019). To date no empirical studies have identified the effect of CSR in the relationship between RL and AOC. For these reasons, the objective of this study is to determine the effect of CSR practices in the relationship between RL and AOC in a group of Colombian employees.

The first approximation to the concept of (RL) was proposed by Lynham (1998) who explained that this style of leadership is oriented to achieve much more than economic results. It implies the adoption of a systemic thinking oriented to effectiveness, ethical behavior, and sustainability over time. Later, Doh and Stumpf (2005), explaining the need to connect leadership with CSR, defined it as a value-based leadership, characterized by ethical decision-making and quality relationships building with stakeholders.

The most cited definition in the literature is the one by Maak and Pless (2006). They indicate that RL is born from the recognition that companies must respond to various stakeholders. In their definition it is explained that RL is an ethical relational phenomenon with various interest groups, where the leader seeks to achieve a greater social good. The responsible leader not only influences his subordinates (employees) but builds long term relationships of trust and influence with various stakeholders (employees, clients, shareholders, suppliers, the government, and the community in general). Thus, they define the RL as: “the art of building and sustaining positive relationships with all relevant stakeholders, with the aim of coordinating actions and achieving common, sustainable and legitimate objectives” (p. 40).

Responsible leadership builds relationships through a process of social deliberation, involvement, and mobilization with stakeholders (Voegtlin et al., 2012) that improves the quality and legitimacy of decisions. In the context of a stakeholder society the purpose of RL is to contribute to sustainable development and the triple bottom line (Maak and Pless, 2006). Therefore, it has been indicated that the greatest challenge of RL is to get the organization to recognize and incorporate its social responsibility (SR) (Pless, 2007). Thus, the leader is responsible to various stakeholders, building relationships based on inclusion and facilitating dialogue between them to achieve a shared vision aimed at sustainable development. The involvement that this leadership style promotes with stakeholders generates the necessary knowledge to promote the innovations that allow the organization to survive and evolve (Doh and Quigley, 2014). Thus, Antunes and Franco (2016) explain that RL is a concept that emerges from the intersection that occurs between the studies of ethics, leadership, and CSR.

Conceptual discussions (see Waldman and Galvin, 2008; Waldman and Siegel, 2008) and discussions of empirical evidence (see Pless et al., 2012; Witt and Stahl, 2016), show that RL styles have different orientations. To enhance understanding and synthesize the RL phenomenon, Maak et al. (2016), explain two styles of RL from the theory of the upper echelons (Hambrick, 2007): instrumental and integrative. These two styles of leadership depend on the moral obligations that leaders perceive toward shareholders or stakeholders. The instrumental responsible leader perceives as a moral obligation the fiduciary duty assumed with the owners of the company. This instrumental approach conceives the role as the guardianship of the interests of the company’s owners. This role emerges as part of a psychological contract with the shareholders in which the leader considers them his employers. On the other hand, the integrative responsible leader, assumes that his moral obligation is with a broad set of stakeholders, and perceives a social contract between the company and society as valid, therefore, considers creating value for all stakeholders a responsibility. This does not mean that the integrative responsible leader does not care about economic performance; it is seen as the result of a successful and purposeful company. In this study we use the integrative approach of RL.

Corporate social responsibility has been addressed since the 1950s. It has been gaining relevance as organizations are pressured to contribute to the solution of environmental and social problems. According to Carroll (1999), the father of CSR is Bowen (1953). In his book published in 1953, “The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman,” he concluded that CSR implies the adoption of policies, decisions and actions that are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of society.

The interest in adopting CSR practices led the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) to develop the guide for incorporating SR practices (ISO 26000: Guidance on Social Responsibility) in organizations (ISO, 2010). In it, SR is defined as “the responsibility of an organization for the impacts that its decisions and activities cause on society and the environment, through an ethical and transparent behavior that contributes to sustainable development including the health and well-being of society …” (p. 4). This study adopted the definition of CSR proposed by Aguinis (2011), “Policies and actions in the organizational context that takes into account the expectations of stakeholders and performance based on the triple bottom line: economic, social and, environmental” (p. 855).

The study of the antecedents and consequences of employee commitment to the organization has been a topic of great interest and has been considered a connection or link between the individual and the organization (Mathieu and Zajac, 1990). AOC has particularly been investigated, as it relates to the emotional bond of employees with the organization. For example, work experiences and perceived organizational support have been found to positively influence AOC, which in turn positively impacts staff turnover rates (Rhoades et al., 2001). The meta-analysis by Meyer et al. (2002) concluded that of the three forms of commitment, AOC has had the strongest and most favorable correlations with behaviors such as performance, attendance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Subsequent studies have found a relationship between organizational commitment and various measures of financial performance (Abdul Rashid et al., 2003).

Afterward, Mercurio (2015) concluded that the AOC is the historical and theoretical basis of the other types of commitment, and after carrying out a meta-analysis found that AOC positively affects the indicators of turnover, absenteeism, organizational citizenship behaviors, and stress. His findings lead him to conclude that AOC is the essence of organizational commitment. This is how AOC begins to be identified as one of the determinants of job performance (Sharma and Dhar, 2016; Wang et al., 2020) and as a mediator of the positive effect of human talent practices on the performance of business units (Raineri, 2017). More recently, it has been recognized as a mediator of the positive influence of supervisor feedback on innovative work behavior (Bak, 2020), and as a mediator of the positive effect of authentic leadership on individual creativity (Ribeiro et al., 2020).

Different leadership styles have been related to employee commitment, this includes between others transformational leadership (Avolio et al., 2004; Keskes et al., 2018; Jiatong et al., 2022), servant leadership (Lapointe and Vandenberghe, 2018), spiritual leadership (Sapta et al., 2021), and authentic leadership (Ausar et al., 2016). This can be explained because several leadership behaviors like decentralization in decision-making, perceived organizational support, perception of importance for the organization (Meyer and Allen, 1991), and perceived organizational support (Rhoades et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 2002) have been identified as determinants of AOC. The RL carries out processes of employee involvement in decision-making, promoting participatory practices that allow the employee to feel important and committed (Voegtlin et al., 2012), also assumes management practices of organizational support to employees and human talent management (Doh et al., 2011), thus can be associated with the AOC by promoting participation and decentralization and increasing the perception of importance of employees for the organization.

In this research this relationship is explained through the social identity theory (SIT), that suggests that individuals tend to classify themselves in social categories that enable to define him or herself in the social environment, in this case the employees identify themselves with the RL role that serves as a referent (Ashforth and Mael, 1989). Particularly employees compare themselves with the dimensions of positive social value (Abrams and Hogg, 1990) that the RL demonstrate by having an ethical behavior and pursuing social and environmental goals.

On the other hand, RL behaviors are negatively related to intention to leave and staff turnover, and this relation is mediated by pride (Doh et al., 2011). RL has also been identified as a strong predictor of significant work in four dimensions: unity with others, expressing full potential, inspiration, and tension equilibrium (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2018). The effect of RL on organizational commitment have been found to be mediated by turnover intention (Haque and Caputi, 2017) and a climate of diversity and inclusion (Mousa, 2017). In this sense, a responsible employee will be linked to a responsible leader and the attributes of the group, which generates a feeling of identity and desire to remain in the company. For these reasons it is proposed that there may be a relationship between RL, and the AOC of employees as is stated in Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: Responsible leadership positively influences the affective organizational commitment of employees.

The relationships between value-based leadership styles such as transformational (Waldman et al., 2006), authentic (Iqbal et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018b; Chaudhary, 2020), ethical (Nejati et al., 2020; Saha et al., 2020), and CSR practices have been studied. The findings indicate that, as these leadership approaches are based on strong ethical values, they can motivate employees by presenting CSR goals that align with their self-concept. Following SIT explanations of group membership, followers may identify with values that go beyond self-interest, like stakeholder needs and the needs of society (Waldman et al., 2006), and thus behave to achieve such goals.

According to the researchers of the RL field of study, there are several mechanisms that explain the RL-CSR relation, it has been explained that one of the central purposes of the RL is to ensure that companies incorporate CSR practices (Pless, 2007), and that the experience, values, and personality of the leader, shape their reasoning about the responsibility of the organization (Maak et al., 2016). Voegtlin et al. (2012) maintain that, RL promotes CSR practices through the construction of relationships with stakeholders, the promotion of an ethical culture based on deliberation practices and the process of raising awareness about the importance of CSR. Incorporating the concerns of stakeholders in decision-making allows the employees to understand the business purpose within the framework of CSR. Similarly, Stahl and Sully de Luque (2014) explain that the RL deploys actions to benefit and to avoid negative impacts on stakeholders. These behaviors of RL contribute to the development of CSR activities, the sense of identification and engagement of employees in responsible behavior with all stakeholders (Haque and Caputi, 2017).

On the relationship between leadership styles associated with RL and CSR, Godos-Díez et al. (2011) analyzed how the leader’s profile is related to the development of CSR practices, as well as the mediation of the perception of the role of ethics and SR; defining two leadership profiles: agency (characterized by selfishness and opportunistic behavior) and servant (characterized by cooperative behavior, which seeks to defend the well-being of various stakeholders) found that those managers with a servant profile were inclined to give more importance to the role and implementation of CSR. Some years later Castro González et al. (2017) identified a positive and significant relationship between RL and perceived CSR. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is proposed.

Hypothesis 2: Responsible leadership positively influences corporate social responsibility practices.

Aguinis and Glavas (2017) recently studied how individuals proactively find meaning in their work, and how this is related to the way they experience CSR practices. In this sense, the relationship between CSR and AOC practices has been a topic of particular interest during the last decade, and several studies have indicated a positive effect of CSR on the organizational commitment of employees in various geographical locations such as North America (Peterson, 2004; Glavas and Kelley, 2014; Vlachos et al., 2014), Pakistan (Ali et al., 2010; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2017), Europe (Ditlev-Simonsen, 2015; Mory et al., 2016a,b), Africa (Mensah et al., 2017; Bouraoui et al., 2018), India (Gupta, 2017), and South Korea (Kim et al., 2018a). As part of the GLOBE project, Mueller et al. (2012), analyzing information collected in 17 countries and with 1084 employees, found a positive relationship between perceived CSR and AOC; their analyzes show that this relationship is strengthened in cultures where there is greater institutional collectivism, human orientation and that it weakens when there are high levels of power distance.

Another stream of research that emphasizes the multidimensionality of CSR has identified the relationship between CSR components and AOC. Internal and external CSR have showed positive effects on organizational commitment (Brammer et al., 2007) as well as CSR to social and non-social stakeholders, to employees and customers (Turker, 2009a). Additionally, AOC has been found to be influenced by CSR related to education and training, human rights, health, safety at work, work life balance and diversity at work (Al-bdour et al., 2010), by CSR with the community, consumers, and employees (Farooq et al., 2014), by CSR with employees, customers, and the government (Hofman and Newman, 2014) and CSR oriented to health, safety, education, and training (Thang and Fassin, 2017).

The relationship between CSR and AOC practices, is explained using the SIT that suggests that employees associate aspects of their self-concept with behaviors and attitudes of certain social groups (Turner and Oakes, 1986). In this case the employees with values oriented toward SR will feel more emotionally committed to organizations that carry out CSR practices, generating a bonding process. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is proposed.

Hypothesis 3: Corporate social responsibility practices positively influences the affective organizational commitment of employees.

In this research, it is proposed that a variation in the RL can cause a variation in the perceived CSR, which in turn could generate a higher level of AOC. This conjecture is argued as follows: the RL creates value for a range of stakeholders in business and in society (Pless et al., 2012), leads the company with an emphasis on the triple bottom line and justifies their decisions under a logic of what is appropriate (Maak et al., 2016). The RL influences the CSR character of the organization, making employees aware of the possible social and environmental consequences of corporate actions, by emphasizing and demonstrating with their actions the importance of involvement with different stakeholders (Voegtlin et al., 2012). These behaviors lead to higher levels of AOC in the employees as their social identity is enhanced when the organization to which the employee belongs is distinctive and more positive than other organizations (Allen et al., 2017).

Thus, RL orients decisions and behavior toward responsibility and coordinates actions to achieve a shared vision of CSR (Maak, 2007). Evidence of this relationship is found in the research carried out by Castro González et al. (2017) that signaled a positive and significant relationship between RL and perceived CSR. In turn, the adoption of CSR practices has been shown to be positively related to organizational commitment (Brammer et al., 2007; Turker, 2009b; Mueller et al., 2012; Hofman and Newman, 2014). The empirical findings of related research explain that, according to the SIT, responsible employees identify themselves with a company that implements CSR practices and has responsible leaders. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is proposed.

Hypothesis 4: CSR is a mediator of the relationship between responsible leadership (RL) and affective organizational commitment (AOC).

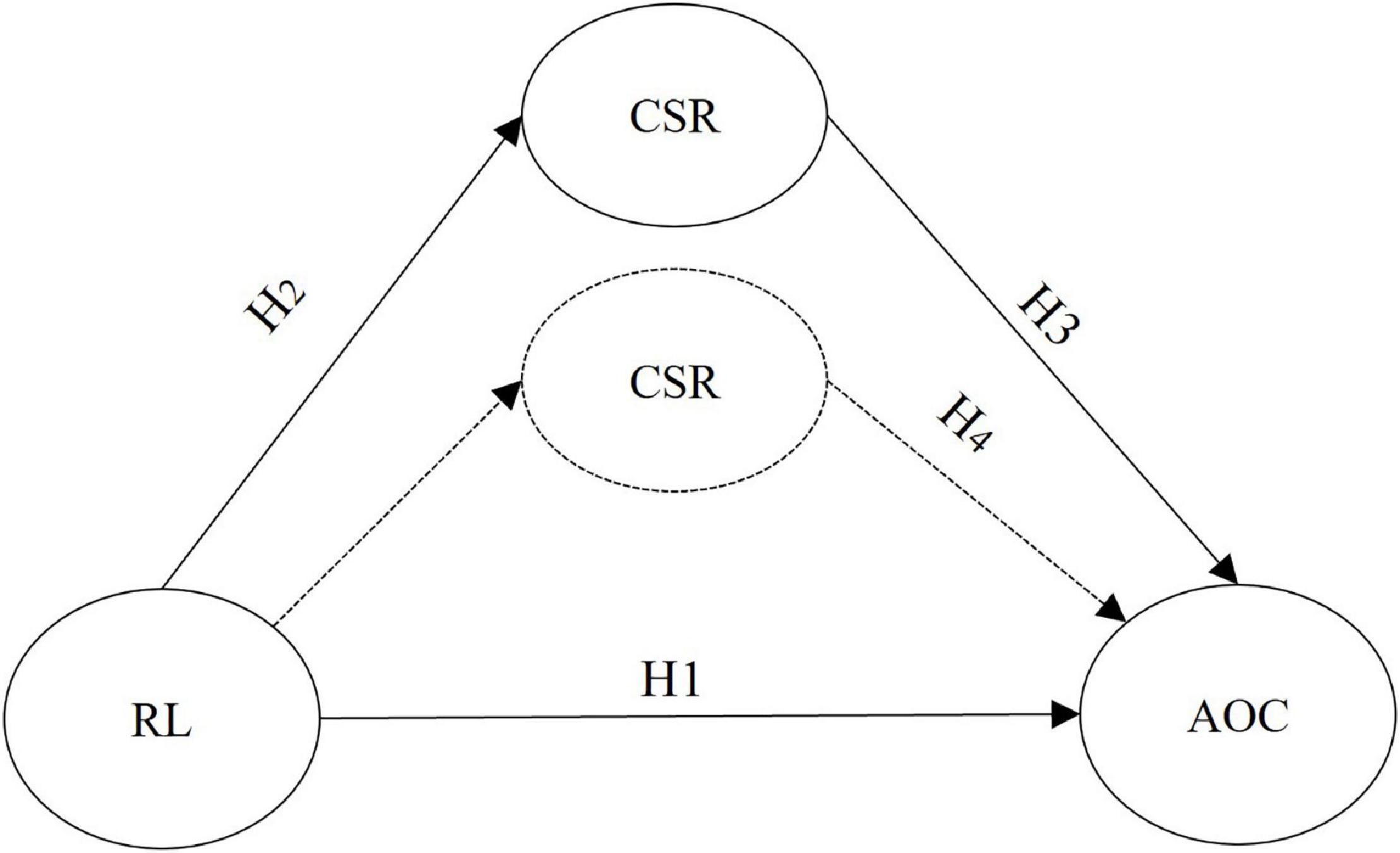

From the previous discussions, a hypothesized model for this study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hypothesized model proposing the direct and mediational relationships. RL, responsible leadership; CSR, corporate social responsibility; AOC, affective organizational commitment.

This research aimed to determine if the RL style has a direct effect on organizational affective commitment (AOC) or if this relationship is mediated by CSR practices. The cause-and-effect explanation makes it part of the functionalist-positivistic research paradigm described by Burrell and Morgan (1979). This study is descriptive, correlational, and explicative in nature. From the perceptions of employees recollected in one point of time, the behaviors of RL, the CSR practices, and the level of AOC are estimated.

In this study, RL influences CSR which in turn influences AOC; it has been suggested that to test this type of causal structures the technique of structural equation modeling (SEM) is adequate (Hair et al., 2009). SEM has been signaled as a robust technique due to its ability to control measurement errors, the possibility of handling different dependent variables and testing models with different assumptions of causality (Ramlall, 2017). It has been considered appropriate to verify if the hypothesized theoretical model is adequate for the sample data (Thakkar, 2020).

The subject type sampling method was used in this study. As inclusion criteria, the participants were Colombian employees, working in the same organization with the same leader for at least the last 12 months, and with a full-time contract. The employees belonged to organizations of different economic sectors and sizes, occupied jobs in different hierarchical levels and different professional backgrounds, allowing variability regarding the type of leader and organization evaluated. This diversity minimizes the common method bias (CMB) as it’s explores different organizational contexts (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

The scales originally developed in English were back translated from Spanish following Brislin (1970) procedure. To minimize CMB, two blank lines were inserted between each scale, a specific instruction was given before the presentation of each set of questions and different number of Likert scale-points were used for each measurement instrument. These procedures allow to psychologically separate the measurement of the independent and dependent variables (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Complementarily, to enhance the motivation to answer the questions, a common and precise language was used, defining less-familiar concepts as could happen with the term: “stakeholders.” Printed questionnaires had spaces between items to eliminate the proximity effect. The data was collected in different parts of the country and analyzed in the SPSS statistical software. To run the SEM procedures the AMOS package was used. Data recollection was done during the second semester of 2019, and during January and February of 2020; 640 questionnaires were answered, of which 309 complied with the inclusion criteria and were considered valid. Finally, the participants were told that their participation was anonymous voluntary, and that they could retire from the study at any time.

In relation to the demographic profile, 55.3% of the survey respondents were women and 44.7% were men. The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 40 or above, with a 42.7% for 18–29 years and with 44.7% for 30–39 years. Among all respondents, 73.8% completed technical or professional education and 26.2% postgraduate degrees. Lastly, 50.6% of respondents had worked with the same superior for 12–28 months and 49.5% for more than 28 months. The detailed data is presented in Table 1.

In the case of RL the unidimensional scale developed by Voegtlin (2011), was selected as it has shown appropriate levels of reliability (Voegtlin, 2011; Castro González et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019; Zhao and Zhou, 2019). This scale is comprised of five items with a 5-point Likert scale: 1. Never, 2. Rarely, 3. Every once in a while, 4. Sometimes, 5. Almost always.

To operationalize and measure CSR practices the scale developed by El Akremi et al. (2018) was used. The scale evaluates the CSR perception of employees using 35 items in relation with the following stakeholders: employees, customers, the environment, shareholders, suppliers, and the community. This instrument has a 6-point Likert scale: 1. Strongly disagree, 2. Disagree, 3. Somewhat disagree, 4. Somewhat agree, 5. Agree, 6. Strongly agree.

To measure AOC the scale developed by Mory et al. (2016b) was selected because it is an improved version of the one built by Meyer and Allen (1991). Its unidimensional and has eight items evaluated through a 7-point Likert Scale: 1. Strongly disagree, 2. Disagree, 3. Somewhat disagree, 4. Neither agree nor disagree, 5. Somewhat agree, 6. Agree, 7. Strongly agree.

The variables RL, CSR, and AOC, were analyzed using descriptive and correlational statistics. To test the proposed hypothesis, the two steps procedure suggested by Byrne (2010) for the SEM technique were carried out: assessing the measurement model and developing the structural model. The first step is performed to examine the validity and reliability of each of the measurement instruments and in this study was developed through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The second step is to test the hypothesized structural model to see if it fits with the data from the sample, this was done using the AMOS module of SPSS. To assess data normality, skewness and kurtosis indicators were calculated. As the data showed a multivariate non-normal distribution, the “Bollen-Stine Bootstrap” (Bollen and Stine, 1992) procedure was carried out to determine if the model was acceptable and SEM fit indexes were estimated using the procedure for non-normal data distributions proposed by Walker and Smith (2017). To determine the significance of the indirect effect of RL through CSR on AOC, a Bootstrap with 5000 iterations and a confidence interval of 95% was executed following Byrne (2010) procedure.

This study considered three control variables: organization size as larger organizations have been found to develop more CSR practices than small ones (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001), sex as previous studies have identified women to score higher on AOC than men (Brammer et al., 2007) and geographical scope, as it is expected that multinational organizations are more willing to perform CSR practices than local ones. The Harman’s one-factor test was calculated to assess if the CMB affected the proposed model.

To determine if the RL directly affects the AOC or if this relationship is mediated by CSR, in this section the results are detailed in the following order: first the descriptive and correlation statistics of the principal variables are showed, then the results of the SEM are presented. The results of the effects of the control variables and of the single factor test for the hypothesized model are subsequently described. Finally, the results of the mediation test are presented.

To identify associations between variables Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. Table 2 allows us to identify that in the study the highest correlation between the main variables is between CSR and AOC with a coefficient of (0.54; p < 0.01), followed by the coefficient (0.31; p < 0.01) between RL and CSR. On the other hand, the weakest coefficient among the three (0.25; p < 0.1) is between RL and AOC.

As is detailed in Appendix Table 1, the (β2) values indicated that none of the items has significant kurtosis (<7), however, the critical ratio exceeds for various items the critical value z (±1.96) signaling a multivariate non-normal data distribution (Byrne, 2010). Since the multivariate non-normal distribution can alter the standard error of the coefficients between the latent variables in SEM (Andreassen et al., 2006), and underestimate the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) fit indices when the maximum likelihood estimation method is used (Byrne, 2010), the procedure known as “Bollen-Stine Bootstrap” (Bollen and Stine, 1992) was carried out to determine if the model can be accepted. Subsequently, the two procedures proposed by Byrne (2010) were carried out; the first step was the evaluation of the measurement model and the second the development of the structural model. During these procedures, the SEM adjusted indices for non-normal data were calculated according to the indications of Walker and Smith (2017). Accordingly, initially the results of the CFA are detailed for the measurement model and afterward the results obtained for the structural equation model (SEM) is presented.

In this study, the RL was measured using the scale developed by Voegtlin (2011) with five items to consider the employees’ perception of RL. The perceptions of CSR practices by the employees was measured with 35 items of the instrument developed by El Akremi et al. (2018) with a Cronbach’s alpha for this study of (α = 0.95). The instrument is made up of six subscales: CSR with the community (α = 0.91), CSR with the environment (α = 0.90), CSR with employees (α = 0.89), CSR with suppliers (α = 0.89), CSR with customers (α = 0.87), and CSR with shareholders (α = 0.91). The AOC was measured with the one-dimensional 8-item scale developed by Mory et al. (2016b). Since the data indicated a non-normal multivariate distribution, the bootstrap procedure was executed (Bollen and Stine, 1992) and a p-value = 0.025 less than 0.05 was obtained, which indicated that the model was not consistent with the data. When reviewing the factor loadings of each of the first order dimensions in the second order dimension CSR, it was identified that the dimension “CSR with the Community” presented a standardized factor load of 0.21, so following the indications of Hair et al. (2009) was eliminated from the measurement model. With the new measurement model without the “CSR with the Community” dimension, the bootstrap procedure was executed (Bollen and Stine, 1992) and a value of p = 0.106 greater than 0.05 was obtained, which indicates that this model was consistent with the data. To calculate the fit indices, the results of χ2 = 10461.674 and df = 820 of the independence model, those of χ2 = 1040.725 and df = 708 of the base model, the sample size n = 309 and the value p = 0.106 were used to run the procedure established by Walker and Smith (2017). The model fit indicators are presented in Table 3.

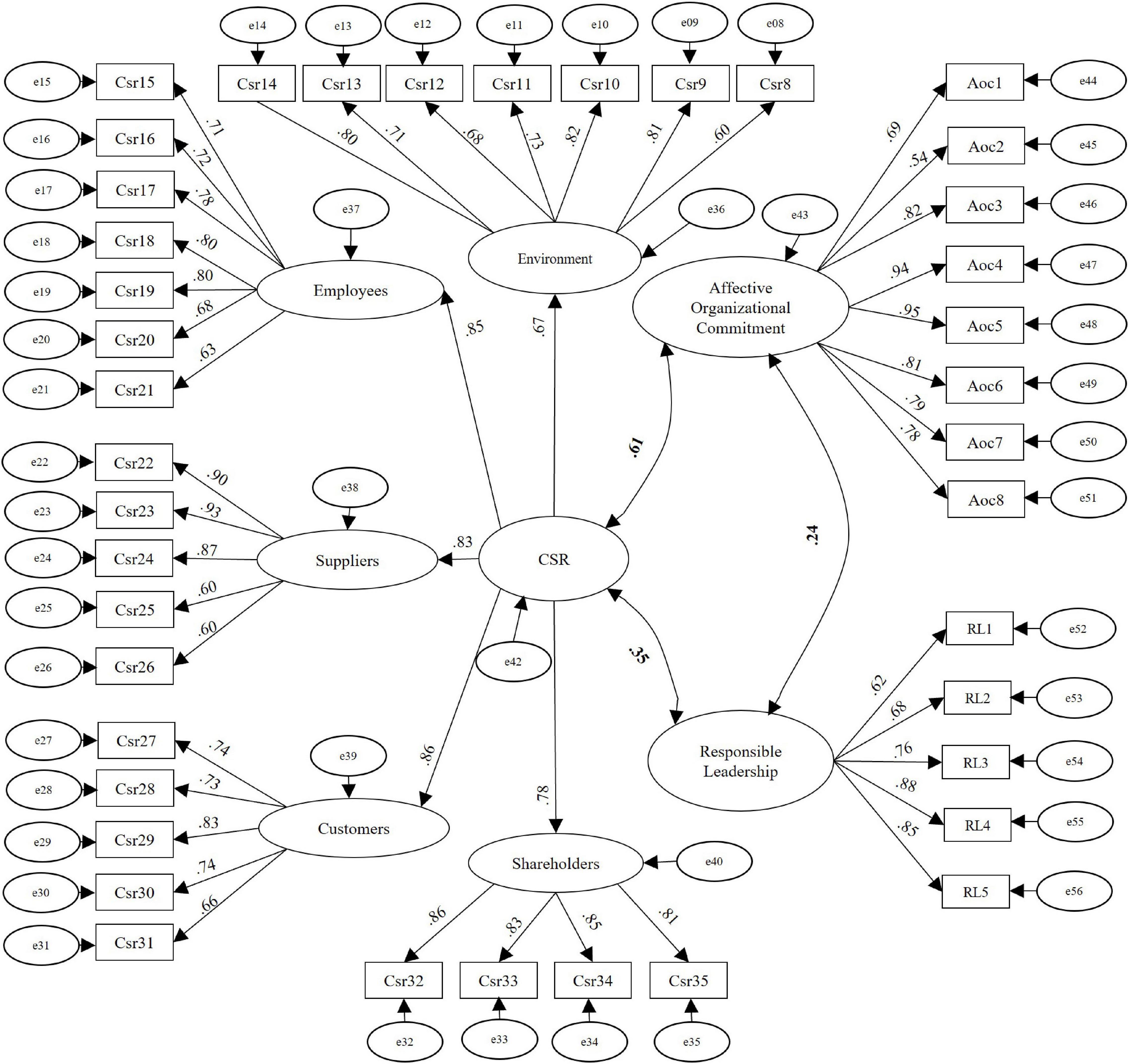

Indices greater than 0.95 were obtained in the adjusted indices of CFI, TLI, and incremental fit index (IFI), and a value less than 0.08 for the adjusted root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which indicates that the measurement model adjusted to the data adequately. The results of the CFA are presented in Figure 2 indicating levels of significance and adequate standardized factor loadings (Hair et al., 2009).

Figure 2. Second-order confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model. This figure represents the CFA of the measurement model, the values in bold correspond to correlations and the others to standardized factor loadings of the observed and latent variables, they are all significant (p < 0.001). n = 309.

Thus, the CFA results for the measurement model present appropriate fit indicators and factor loadings.

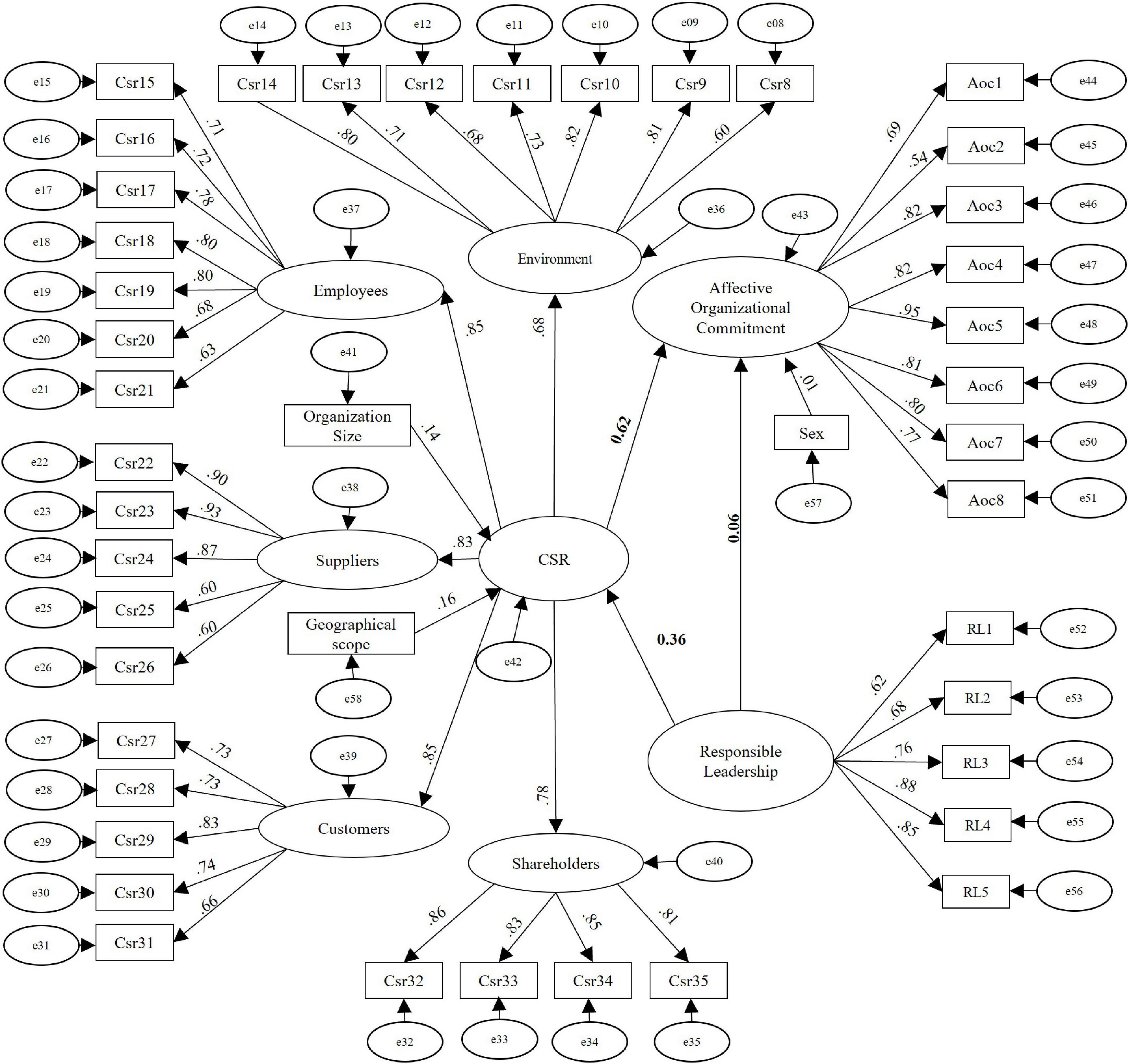

In this study, a structural model was developed to test the mediating effect of CSR on the effect between RL and AOC. The standardized regression coefficients (β) are presented in bold in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Structural equation model of the mediation of CSR between RL and AOC. The values in bold correspond to standardized coefficients (β) and the others to standardized factor loadings of the observed and latent variables. n = 309.

Since the data showed a non-normal distribution, the bootstrap procedure was executed (Bollen and Stine, 1992), obtaining a value p = 0.066 greater than 0.05, which indicates that the model is consistent with the data. To calculate the fit indices, the results of χ2 = 10681.241 and df = 946 of the independence model, those of the base model χ2 1229.038 and df = 830, the sample size n = 309 and the value p = 0.066 were used to run the procedure established by Walker and Smith (2017). The model fit indicators are presented in Table 4.

Indexes greater than 0.95 were obtained in the adjusted indices of CFI, TLI, and IFI, and an index less than 0.08 for the adjusted RMSEA, which indicates that the CSR mediation model adjusted to the data adequately.

The hypothesis was tested using the estimated parameters of the structural model. As presented in Table 5, the direct effect of RL on AOC was not significant (β = 0.06; p > 0.005), rejecting Hypothesis 1, while the indirect effect of RL on AOC, through CSR, was (β = 0.22; p < 0.001) which confirmed Hypothesis 4. The significance of the indirect effect was calculated through the Bootstrap procedure with 5000 samples and a 95% corrected bias confidence interval in the AMOS software. The effect of RL on CSR was positive (β = 0.36; p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 2. A positive influence of CSR on AOC is also observed (β = 0.62; p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 3.

As control variables for this research, the size, geographical scope of the organization (local or multinational) and the sex of the employees surveyed were considered. As can be seen in Figure 3, the size of the organization has a standardized effect on CSR practices of (β = 0.14; p < 0.05); the geographic scope of operation a standardized effect on CSR practices of (β = 0.16; p < 0.01); and finally, the sex of the participants has a standardized effect of (β = 0.16; ns). To determine the existence of the common method bias, the Harman single factor test was carried out, which assesses the degree to which a latent common factor accounts for all the manifest variables. The test was carried out using an exploratory factor analysis with an unrotated factor solution (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The total variance explained by a single factor was 36.8%, less than 50%, which indicates that the common method bias was not a risk in this study.

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of CSR practices in the relationship between RL and AOC in a group of Colombian employees, the results showed that RL influences the level of AOC through the development of CSR practices. This demonstrate that RL can be a relevant determinant of value generation for stakeholders and the environment. Also, that it can be a leadership style that emotionally connects the employee to the organization, through the development of CSR practices.

The claim of contributing to the challenge of sustainability from management science (Ghoshal, 2005) implies the comprehension of the leadership needed to manage environmental and social issues in organizations. Ethical scandals of several managers, environmental movements, and social expectations, have seriously questioned the vision and behavior of business leaders (Muff et al., 2020). For these reasons, this research expands the existing knowledge in the field of RL, describes it as aware of the economic, environmental, and social impact of organizations, and points out the implications of promoting spaces for collective construction with stakeholders. It is emphasized in this research that the RL not only focuses on the relationship of influence with its employees, but also builds long-term and trusting relationships with multiple stakeholders (Maak and Pless, 2006). This conception allows to understand the role of business leaders as global citizens who seek the common good (Maak and Pless, 2009) and the dimension of responsibility in managerial practice (Voegtlin, 2016). This is how the RL is conceived responsible toward a wide set of interest groups (Maak et al., 2016) being the one that maximizes value for the different interest groups, internalizes the negative impacts, is long-term oriented and is regenerative rather than degenerative (WBCSD, 2020).

This research expands the knowledge on the outcomes of RL. It has been pointed out that the RL deploys CSR practices (Voegtlin et al., 2012) and this study presents empirical evidence of the positive and significant effect of the RL style on the development of CSR practices. This result indicates that those leaders who consider the concerns of stakeholders in their decision-making process and who seek to generate value in the triple bottom line contribute to the deployment of various CSR activities. According to SIT the followers will be proud of their responsible leaders, sharing a social category membership with the organization, and acting accordingly. It provides additional evidence to the positive influence of RL on CSR found by Castro González et al. (2017) in Spain and to the investigations that account for the relationship between leadership styles and the development of CSR practices (Godos-Díez et al., 2011; Groves and LaRocca, 2011; Du et al., 2013; Saha et al., 2020). It provides complementary evidence of the positive relationship between leadership and organizational commitment in the Colombian context (Bohorquez, 2016; Mañas-Rodríguez et al., 2020).

In this study, the understanding of the effects of CSR is broadened, by confirming hypothesis number three that indicates the positive and significant effect of CSR practices on the AOC level of employees in Colombia. This is justified as SIT suggest that individuals have a desire for positive self-evaluation, in this case being part of an organization that behaves more responsibly than others can enhance their social identity (Abrams and Hogg, 1990). This result is in line with the findings on the positive influence of CSR on AOC in other geographical areas such as North America (Peterson, 2004; Glavas and Kelley, 2014; Vlachos et al., 2014), Pakistan (Ali et al., 2010; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2017), Northern Europe (Ditlev-Simonsen, 2015; Mory et al., 2016a,b), Africa (Gupta, 2017; Mensah et al., 2017; Bouraoui et al., 2018), South Korea (Kim et al., 2018a), and in the countries that have been part of the GLOBE project (Mueller et al., 2012). According to the literature review, this increase in AOC levels is due to higher levels of identification and reciprocity of the employee with the organization that is concerned with generating social, environmental, and not only economic value. This finding is in line with the positive and significant relation between internal CSR and AOC found the Colombian context (Ávila-Tamayo and Bayona, 2022). However, the use of the multidimensional CSR scale, developed by El Akremi et al. (2018) allowed to identify that the CSR dimension with the community was not relevant in the Colombian context; its slight manifestation may be due to organizations prioritizing other CSR dimensions. This study contributes to the body of knowledge of CSR by identifying RL as an antecedent and AOC as an outcome.

Furthermore, this research contributes to the understanding of the mechanism of influence of RL on AOC. The result of the parameter that evaluates Hypothesis 1 indicates that the direct influence of RL on AOC is almost null and not significant; while the test parameter for Hypothesis 4 indicates that the indirect effect of RL on AOC through CSR practices is positive and significant. The result of Hypothesis 1 indicates that the variations in AOC levels are not directly explained by the adoption of the RL style. According to the result of Hypothesis 4, employees will increase their AOC level when the RL achieves the effective deployment of CSR practices. This finding can be explained using the SIT (Turner and Oakes, 1986), according to which people are attracted to groups whose behaviors are framed by what they consider valuable. In this way, organizations that incorporate or develop managers with RL styles will be able to deploy CSR practices, which will increase the AOC level of employees. This finding is consistent with the results of the research carried out by Castro González et al. (2017) who identified that CSR mediates the influence of RL on the creativity of a group of vendors, those of Mousa (2017) who found that climate diversity and inclusion mediates the relationship of influence between RL on organizational commitment, those of Haque and Caputi (2017) which indicate that employee turnover intention partially mediate the effect of RL on the AOC level and those of Voegtlin et al. (2020) that found a positive relationship between RL and AOC. The result is also associated with the mediating role of CSR in the relationship between transformational leadership and AOC reported by Allen et al. (2017). In general, it is observed that the effects of the RL style on the psychological and behavioral states of employees occur indirectly. Likewise, it was observed that gender did not affect the AOC levels, while the size of the organization and the geographical scope of operation affected the level of CSR practices in a slightly but significant way.

In terms of theoretical implications, this study provides an explanation of how CSR mediates the relationship between RL and AOC using the SIT framework. Followers feel identified with responsible leaders that act according to higher moral standards, and with organizations that are responsive to societal expectations. These higher levels of social identification with RL and organizations increase the level of AOC. This study explains how CSR practices mediate the relationship as employees are the first ones to experience the effects of RL in the operations of the organization and their impact in the wellbeing of society and the planet.

The results of this research have practical implications for managers who face the challenge of getting their organizations to regain the trust lost due to negative environmental impacts and increased inequity (Edelman, 2020). The findings indicate that managers who adopt and promote the RL will favor the development of CSR practices in their organizations, building sustainable and trusting relationships with different stakeholders and coordinating their action to achieve common goals, sustainability, and social legitimacy (Maak and Pless, 2006). Besides, organizations should recognize that developing RL behaviors can strengthen the capacity of managers to motivate and have an engaged workforce, for example in the Colombian context adopting a transformational leadership style – ethical and value-based leadership approach – can help managers increase the level of commitment of their workers (Bohorquez, 2016; Mañas-Rodríguez et al., 2020). Additionally, as organizations are pressured to contribute to sustainable development, HR departments should include responsible competencies as criteria for selecting leaders; and develop leadership training programs that emphasize the development of RL skills.

On the other hand, since the results of this research indicate the strong influence of CSR practices on the AOC of employees, it is desirable to periodically socialize the projects that the company carries out to meet the needs of the different stakeholders. Previous research has found that workers with high levels of AOC improve their job performance (Sharma and Dhar, 2016; Wang et al., 2020) and achieve higher levels of creativity (Ribeiro et al., 2020). The results also indicate that it is not enough for managers to recognize and show their willingness to incorporate CSR, it is necessary to effectively deploy CSR projects in such a way that employees perceive their development, which in turn enhance their self-identity and levels of AOC. For the Colombian context it has been found that is desirable to develop internal CSR practices to develop higher levels of AOC (Ávila-Tamayo and Bayona, 2022).

These findings suggest that managers that wish to develop CSR practices can adopt a RL style, and that this leadership style can increase AOC when CSR practices with employees, suppliers, customers, and the environment are developed. This work provides a new conceptual model which considers the mediation role of CSR on the relationship between RL and AOC and offers an empirical validation with a sample of employees in a developing country.

This study has limitations related to data collection, sample size and scope. Data collection was carried out through a self-report questionnaire answered by employees, which can lead to social desirability bias; this means that the participants could tend to present a favorable image of themselves and their organizations. In future studies, this bias can be mitigated by using various sources for data collection, for example, surveying not only employees but also managers. Since it is a cross-sectional study, it does not allow the analysis of data evolution. Future studies could use a longitudinal approach that provides more complete explanations on the causality between variables under study.

This investigation used a subject type – feasible sample so a larger sample is desirable in further research to generalize. For example, future studies could use representative samples from various sectors or countries to evaluate the effect of context variables such as culture, sector dynamics or government regulations.

The hypothetical model could be refined to give more rigor to the study, for example, it is necessary to evaluate the probable mediating role of human resources practices such as: job design, organizational climate, or work life balance. Research on the effects of RL on other outcomes such as civic or environmental behaviors is needed. On the other hand, research on internal determinants of CSR, such as board composition or strategic choices is still required. Finally, future research from a qualitative approach could investigate the reasons why certain dimensions of CSR are presented with more intensity than others and how they are developed.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RP wrote all the sections of this manuscript.

This article was a product of a research project funded by the Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The author is particularly grateful for the assistance given by the researchers of the Leadership and Organizational Behavior group of the School of Management of Universidad del Rosario, for their help in the development of this research.

CSR, corporate social responsibility; RL, responsible leadership; AOC, affective organizational commitment; SIT, social identity theory; SEM, structural equation modeling.

Abdul Rashid, Z., Sambasivan, M., and Johari, J. (2003). The influence of corporate culture and organisational commitment on performance. J. Manag. Dev. 22, 708–728. doi: 10.1108/02621710310487873

Abrams, D. E., and Hogg, M. A. (1990). Social identity theory: Constructive and critical advances. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Publishing.

Aguinis, H. (2011). “Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well,” in APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization, Vol. 3, ed. S. Zedeck (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 855–879.

Aguinis, H., and Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: a review and research agenda. J. Manag. 38, 932–968. doi: 10.1177/0149206311436079

Aguinis, H., and Glavas, A. (2017). On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2017:0149206317691575. doi: 10.1177/0149206317691575

Al-bdour, A. A., Nasruddin, E., and Lin, S. K. (2010). The relationship between internal corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment within the banking sector in Jordan. Internat. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 5, 932–951. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1054799

Ali, I., Rehman, K. U., Ali, S. I., Yousaf, J., and Zia, M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 4, 2796–2801. doi: 10.5897/AJBM.9000159

Allen, G. W., Attoh, P. A., and Gong, T. (2017). Transformational leadership and affective organizational commitment: mediating roles of perceived social responsibility and organizational identification. Soc. Responsib. J. 13, 585–600. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-11-2016-0193

Andreassen, T. W., Lorentzen, B. G., and Olsson, U. H. (2006). The impact of non-normality and estimation methods in SEM on satisfaction research in marketing. Qual. Quan. 40, 39–58. doi: 10.1007/s11135-005-4510-y

Antunes, A., and Franco, M. (2016). How people in organizations make sense of responsible leadership practices: multiple case studies. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 37, 126–152. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-04-2014-0084

Ashforth, B. E., and Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 20–39.

Asrar-ul-Haq, M., Kuchinke, K. P., and Iqbal, A. (2017). The relationship between corporate social responsibility, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment: case of Pakistani higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 142, 2352–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.040

Ausar, K., Kang, H. J. A., and Kim, J. S. (2016). The effects of authentic leadership and organizational commitment on turnover intention. Leadership Org. Dev. J. 2, 181–199. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-05-2014-0090

Ávila-Tamayo, D. F., and Bayona, J. A. (2022). Spanish–speaking validation of the internal corporate social responsibility questionnaire. PLoS One 17:e0266711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266711

Avolio, B. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., and Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J. Org. Behav. 25, 951–968. doi: 10.1002/job.283

Bak, H. (2020). Supervisor Feedback and Innovative Work Behavior: the Mediating Roles of Trust in Supervisor and Affective Commitment. Front. Psychol. 11:559160. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559160

Boddy, C. R., Ladyshewsky, R. K., and Galvin, P. (2010). The influence of corporate psychopaths on corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment to employees. J. Bus. Eth. 97, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0492-3

Bohorquez, N. (2016). Perception of leadership styles, organizational commitment and burnout in faculty of Colombian universities. [dissertation/doctoral thesis]. Scottsdale, AZ: Northcentral University.

Bollen, K. A., and Stine, R. A. (1992). Bootstrapping Goodness-of-Fit Measures in Structural Equation Models. Sociol. Methods Res. 21, 205–229. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002004

Bouraoui, K., Bensemmane, S., Ohana, M., and Russo, M. (2018). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment: a multiple mediation model. Manag. Dec. 2018:1015. doi: 10.1108/MD-10-2017-1015

Brammer, S., Millington, A., and Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Internat. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 18, 1701–1719. doi: 10.1080/09585190701570866

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1, 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

Burrell, G., and Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. London: Heinemann Educational, doi: 10.4324/9781315242804

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series), Vol. 396. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group, 7384.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38, 268–295. doi: 10.1177/000765039903800303

Castro González, S., Bande Vilela, B., and Fernández Ferrín, P. (2017). Liderazgo responsable, RSC y creatividad del vendedor. Sevilla: XXIX Congreso de Marketing AEMARK, 998–1012.

Chaudhary, R. (2020). Authentic leadership and meaningfulness at work: role of employees’ CSR perceptions and evaluations. Manag. Dec. 59, 2024–2039. doi: 10.1108/MD-02-2019-0271

Ditlev-Simonsen, C. D. (2015). The relationship between Norwegian and Swedish employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility and affective commitment. Bus. Soc. 54, 229–253. doi: 10.1177/0007650312439534

Doh, J. P., and Quigley, N. R. (2014). Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 28, 255–274. doi: 10.5465/amp.2014.0013

Doh, J. P., and Stumpf, S. A. (2005).? Handbook on responsible leadership and governance in global business. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Doh, J. P., Stumpf, S. A., and Tymon, W. G. (2011). Responsible leadership helps retain talent in India in?Responsible Leadership. Dordrecht: Springer. 85–100. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-3995-6_8

Du, S., Swaen, V., Lindgreen, A., and Sen, S. (2013). The roles of leadership styles in corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 114, 155–169. doi: 10.1007/s10551-012-1333-3

Edelman (2020). Edelman trust barometer: Global Report. Available online at: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/440941/Trust%20Barometer%202020/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report.pdf?utm_campaign=Global:%20Trust%20Barometer%202020&utm_source=Website (accessed May, 2022).

El Akremi, A., Gond, J. P., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K., and Igalens, J. (2018). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 44, 619–657. doi: 10.1177/0149206315569311

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., and Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 125, 563–580. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1928-3

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices.? Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. ? 4, 75–91. doi: 10.5465/amle.2005.16132558

Glavas, A., and Kelley, K. (2014). The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 24, 165–202. doi: 10.5840/beq20143206

Godos-Díez, J. L., Fernández-Gago, R., and Martínez-Campillo, A. (2011). How important are CEOs to CSR practices? An analysis of the mediating effect of the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethic. 98, 531–548. doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0609-8

Groves, K. S., and LaRocca, M. A. (2011). An empirical study of leader ethical values, transformational and transactional leadership, and follower attitudes toward corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 103, 511–528. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0877-y

Gupta, M. (2017). Corporate social responsibility, employee–company identification, and organizational commitment: mediation by employee engagement. Curr. Psychol. 36, 101–109. doi: 10.1007/s12144-015-9389-8

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis 7th Edition Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hambrick, D. C. (2007). ‘Upper echelons theory: an update’. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32, 334–343. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.24345254

Han, Z., Wang, Q., and Yan, X. (2019). How Responsible Leadership Motivates Employees to Engage in Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: a Double-Mediation Model. Sustainability 11:605. doi: 10.3390/su11030605

Haque, A. F., and Caputi, P. (2017). The Relationship between Responsible Leadership and Organisational Commitment and the Mediating Effect of Employee Turnover Intentions: an Empirical Study with Australian Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3575-6

Hofman, P. S., and Newman, A. (2014). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: evidence from China. Internat. J. Hum. Resourc. Manag. 25, 631–652. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.792861

Iqbal, S., Farid, T., Ma, J., Khattak, A., and Nurunnabi, M. (2018). The impact of authentic leadership on organizational citizenship behaviours and the mediating role of corporate social responsibility in the banking sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 10:2170. doi: 10.3390/su10072170

Jiatong, W., Wang, Z., Alam, M., Murad, M., Gul, F., and Gill, SA. (2022). The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Affective Organizational Commitment and Job Performance: the Mediating Role of Employee Engagement. Front. Psychol. 13:831060.

Keskes, I., Sallan, J. M., Simo, P., and Fernandez, V. (2018). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: mediating role of leader-member exchange. J. Manag. Dev. 37, 271–284. doi: 10.1108/JMD-04-2017-0132

Kim, B. J., Nurunnabi, M., Kim, T. H., and Jung, S. Y. (2018a). The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: the sequential mediating effect of meaningfulness of work and perceived organizational support. Sustainability 10:2208. doi: 10.3390/su10072208

Kim, B. J., Nurunnabi, M., Kim, T. H., and Kim, T. (2018b). Doing good is not enough, you should have been authentic: organizational identification, authentic leadership and CSR. Sustainability 10:2026. doi: 10.3390/su10062026

Lapointe, E., and Vandenberghe, C. (2018). Examination of the Relationships Between Servant Leadership, Organizational Commitment, and Voice and Antisocial Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 148, 99–115. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-3002-9

Lips-Wiersma, M., Haar, J., and Wright, S. (2018). The Effect of Fairness, Responsible Leadership and Worthy Work on Multiple Dimensions of Meaningful Work. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3967-2

Lynham, S. A. (1998). The development and evaluation of a model of responsible leadership for performance: beginning the journey. Hum. Resourc. Dev. Internat. 1:207.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital.? J. Bus. Ethics ? 74, 329–343. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9510-5

Maak, T., and Pless, N. M. (2006). Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society–a relational perspective. ? J. Bus. Ethics? 66, 99–115. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9047-z

Maak, T., and Pless, N. M. (2009). Business leaders as citizens of the world. Advancing humanism on a global scale.? J. Bus. Ethic. ? 88, 537–550. doi: 10.1007/s10551-009-0122-0

Maak, T., Pless, N. M., and Voegtlin, C. (2016). Business statesman or shareholder advocate? CEO responsible leadership styles and the micro-foundations of political CSR.? J. Manag. Stud. 53, 463–493. doi: 10.1111/joms.12195

Mañas-Rodríguez, M. A., Enciso-Forero, E., Salvador-Ferrer, C. M., Trigueros, R., and Aguilar-Parra, J. M. (2020). Empirical Research in Colombian Services Sector: relation between Transformational Leadership, Climate and Commitment. Sustainability 12:6659. doi: 10.3390/su12166659

Mathieu, J. E., and Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol. Bull. 108:171. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171

McWilliams, A., and Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 26, 117–127. doi: 10.5465/amr.2001.4011987

Mensah, H. K., Agyapong, A., and Nuertey, D. (2017). The effect of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment of employees of rural and community banks in Ghana. Cog. Bus. Manag. 4:1280895. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2017.1280895

Mercurio, Z. A. (2015). Affective commitment as a core of organizational commitment: an integrative literature review. Hum. Resourc. Dev. Rev. 14, 389–414. doi: 10.1177/1534484315603612

Meyer, J. P., and Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resourc. Manag. Rev. 1, 61–89. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., and Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 61, 20–52. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Miska, C., and Mendenhall, M. E. (2018). Responsible leadership: a mapping of extant research and future directions. J. Bus. Ethic. 148, 117–134. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2999-0

Mory, L., Wirtz, B. W., and Göttel, V. (2016a). Corporate social responsibility strategies and their impact on employees’ commitment. J. Strat. Manag. 9, 172–201. doi: 10.1108/JSMA-12-2014-0097

Mory, L., Wirtz, B. W., and Göttel, V. (2016b). Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. Internat. J. Hum. Resourc. Manag. 27, 1393–1425. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2015.1072103

Mousa, M. (2017). Responsible Leadership and Organizational Commitment among Physicians: can Inclusive Diversity Climate Enhance the Relationship? J. Intercult. Manag. 52, 103–141.

Mueller, K., Hattrup, K., Spiess, S. O., and Lin-Hi, N. (2012). The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: a cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 97:1186. doi: 10.1037/a0030204

Muff, K., Liechti, A., and Dyllick, T. (2020). How to apply responsible leadership theory in practice: a competency tool to collaborate on the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Env. Manag. 27, 2254–2274. doi: 10.1002/csr.1962

Nejati, M., Salamzadeh, Y., and Loke, C. K. (2020). “Can ethical leaders drive employees’ CSR engagement? Soc. Responsib. J. 16, 655–669. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-11-2018-0298

Patzer, M., Voegtlin, C., and Scherer, A. G. (2018). The normative justification of integrative stakeholder engagement: a Habermasian view on responsible leadership. Bus. Ethics Q. 28, 325–354. doi: 10.1017/beq.2017.33

Peterson, D. K. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 43, 296–319. doi: 10.1177/0007650304268065

Pless, N. M. (2007). Understanding responsible leadership: role identity and motivational drivers. J. Bus. Ethic. 74, 437–456. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9518-x

Pless, N. M., Maak, T., and Waldman, D. A. (2012). Different approaches toward doing the right thing: mapping the responsibility orientations of leaders. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 26, 51–65. doi: 10.5465/amp.2012.0028

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88:879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Raineri, A. (2017). Linking human resources practices with performance: the simultaneous mediation of collective affective commitment and human capital. Internat. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 28, 3149–3178. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1155163

Ramlall, I. (2017). Applied Structural Equation Modelling for Researchers and Practitioners: Using R and Stata for Behavioural Research: Vol. 1. First edition. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., and Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: the contribution of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 86:825. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

Ribeiro, N., Duarte, A. P., Filipe, R., and Torres de Oliveira, R. (2020). How authentic leadership promotes individual creativity: the mediating role of affective commitment. J. Leadership Org. Stud. 27, 189–202. doi: 10.1177/1548051819842796

Rodrigo, P., Aqueveque, C., and Duran, I. J. (2019). Do employees value strategic CSR? A tale of affective organizational commitment and its underlying mechanisms. Bus. Ethic. 28, 459–475. doi: 10.1111/beer.12227

Saha, R., Cerchione, R., Singh, R., and Dahiya, R. (2020). Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: a systematic review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Env. Manag. 27, 409–429. doi: 10.1002/csr.1824

Sapta, I. K. S., Rustiarini, N. W., Kusuma, I. G. A. E. T., and Astakoni, I. M. P. (2021). Spiritual leadership and organizational commitment: the mediation role of workplace spirituality. Cog. Bus. Manag. 8:1966865. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2021.1966865

Scherer, A. G., and Palazzo, G. (2011). The new political role of business in a globalized world: a review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy.? J. Manag. Stud. ? 48, 899–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00950.x

Sharma, J., and Dhar, R.L. (2016). Factors influencing job performance of nursing staff: mediating role of affective commitment. Person. Rev. 45, 161–182. doi: 10.1108/PR-01-2014-0007

Stahl, G. K., and Sully de Luque, M. (2014). Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: a research synthesis, conceptual framework, and agenda for future research. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 28, 235–254. doi: 10.5465/amp.2013.0126

Thakkar, J. J. (2020). Applications of structural equation modelling with AMOS 21, IBM SPSS in Structural Equation Modelling. Singapore: Springer. 35–89.

Thang, N. N., and Fassin, Y. (2017). The impact of internal corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: evidence from Vietnamese service firms. J. Asia-Pacific Bus. 18, 100–116. doi: 10.1080/10599231.2017.1309617

Turker, D. (2009a). Measuring corporate social responsibility: a scale development study. J. Bus. Ethic. 85, 411–427. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9780-6

Turker, D. (2009b). How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethic. 89:189. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9993-8

Turner, J. C., and Oakes, P. J. (1986). The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 25, 237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00732.x

Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., and Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: a multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. J. Org. Behav. 35, 990–1017. doi: 10.1002/job.1946

Voegtlin, C. (2011). Development of a scale measuring discursive responsible leadership in Responsible Leadership. Dordrecht: Springer. 57–73. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-3995-6_6

Voegtlin, C. (2016). What does it mean to be responsible? Addressing the missing responsibility dimension in ethical leadership research.? Leadership 12, 581–608. doi: 10.1177/1742715015578936

Voegtlin, C., Frisch, C., Walther, A., and Schwab, P. (2020). Theoretical Development and Empirical Examination of a Three-Roles Model of Responsible Leadership. J Bus Ethics 167, 411–431. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04155-2

Voegtlin, C., Patzer, M., and Scherer, A. G. (2012). Responsible leadership in global business: a new approach to leadership and its multi-level outcomes.? J. Bus. Ethic.? 105, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0952-4

Waldman, D. A., and Galvin, B. M. (2008). Alternative perspectives of responsible leadership.? Org. Dyn. 37, 327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2008.07.001

Waldman, D. A., and Siegel, D. (2008). Defining the socially responsible leader.? Leadership Q.? 19, 117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.12.008

Waldman, D. A., Siegel, D. S., and Javidan, M. (2006). Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. Stud. 43, 1703–1725. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00642.x

Walker, D. A., and Smith, T. J. (2017). Computing robust, bootstrap-adjusted fit indices for use with nonnormal data. Measur. Eval. Counsel. Dev. 50, 131–137. doi: 10.1080/07481756.2017.1326748

Wang, Q., Weng, Q., and Jiang, Y. (2020). When Does Affective Organizational Commitment Lead to Job Performance?: integration of Resource Perspective. J. Career Dev. 47, 380–393. doi: 10.1177/0894845318807581

WBCSD (2020). Reinventing capitalism: a transformation agenda. Available online at: https://www.wbcsd.org/Overview/About-us/Vision-2050-Refresh/Resources/Reinventing-capitalism-a-transformation-agenda#:~:text=The%20issue%20brief%2C%20Reinventing%20Capitalism,take%20today%20to%20drive%20transformation (accessed date 11 Nov 2020).

Witt, M. A., and Stahl, G. K. (2016). Foundations of responsible leadership: asian versus Western executive responsibility orientations toward key stakeholders.? J. Bus. Ethic.? 136, 623–638. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2534-8

Zhao, H., and Zhou, Q. (2019). Exploring the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: a Leadership Identity Perspective. Sustainability 11:944. doi: 10.3390/su11040944

Keywords: corporate social responsibility, affective organizational commitment, responsible leadership, social identity theory, stakeholders

Citation: Piñeros Espinosa RA (2022) Responsible Leadership and Affective Organizational Commitment: The Mediating Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility. Front. Psychol. 13:868057. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868057

Received: 02 February 2022; Accepted: 20 June 2022;

Published: 28 July 2022.

Edited by:

Susanne Rank, Hochschule Mainz, GermanyReviewed by:

Iftikhar Hussain, University of Kotli Azad Jammu and Kashmir, PakistanCopyright © 2022 Piñeros Espinosa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rafael Alejandro Piñeros Espinosa, cmFmYWVsLnBpbmVyb3NAdXJvc2FyaW8uZWR1LmNv

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.