95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CLINICAL TRIAL article

Front. Psychol. , 04 November 2022

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.867246

This article is part of the Research Topic Systemic Explanations of Psychological Symptoms and Distress in Clinical and Research Practice View all 9 articles

Christina Hunger-Schoppe1,2*

Christina Hunger-Schoppe1,2* Jochen Schweitzer2,3

Jochen Schweitzer2,3 Rebecca Hilzinger2

Rebecca Hilzinger2 Laura Krempel4

Laura Krempel4 Laura Deußer5

Laura Deußer5 Anja Sander6

Anja Sander6 Hinrich Bents5

Hinrich Bents5 Johannes Mander5

Johannes Mander5 Hans Lieb7,8,9

Hans Lieb7,8,9Social anxiety disorders (SAD) are among the most prevalent mental disorders (lifetime prevalence: 7–12%), with high impact on the life of an affected social system and its individual social system members. We developed a manualized disorder-specific integrative systemic and family therapy (ISFT) for SAD, and evaluated its feasibility in a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT). The ISFT is inspired by Helm Stierlin’s concept of related individuation developed during the early 1980s, which has since continued to be refined. It integrates solution-focused language, social network diagnostics, and genogram work, as well as resource- and problem orientation for both case conceptualization and therapy planning. Post-Milan symptom prescription to fluidize the presented symptoms is one of the core interventions in the ISFT. Theoretically, the IFST is grounded in radical constructivism and “Cybern-Ethics,” multi-directional partiality, and a both/and attitude toward a disorder-specific vs. non-disorder-specific therapy approach. SAD is understood from the viewpoint of social systems theory, especially in adaptation to a socio-psycho-biological explanatory model of social anxiety. In a prospective multicenter, assessor-blind pilot RCT, we included 38 clients with SAD (ICD F40.1; Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, LSAS-SR > 30): 18 patients participated in the ISFT, and 20 patients in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT; age: M = 36 years, SD = 14). Within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses showed significant reduction in social anxiety (LSAS-SR; ISFT: d = 1.67; CBT: d = 1.04), while intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA demonstrated the advantage of ISFT (d = 0.81). Per-protocol analyses supported these results. The remission rate based on blind diagnosticians’ ratings was good to satisfactory (Structured Clinical Interview, SCID; 78% in ST, 45% in CBT, p = 0.083); this has yet to be verified in a subsequent confirmatory RCT. The article will present the ISFT rationale and manual, including a special focus on multi-person settings, and the central findings from our pilot RCT.

Collective psychotherapy cultures follow the principle of “healing as a joint achievement” (Schweitzer, 2014). They incorporate an understanding of psychotherapy that has been pushed back in individualized societies to the advantage of individual diagnosis and intervention (“single-person therapy”). Collective psychotherapy cultures, however, have the potential to make a significant difference in the discourse of psychotherapy when, in addition to “index clients” and therapists, therapy equally includes family members, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and co-workers, as well as supervisors (“multi-person therapy”). They all can contribute to the development, maintenance, and change of mental disorders and physical illnesses. Therapists who value and believe in the engagement of all these social system members, even if they completely contradict each other, embody core principals of systemic thinking: e.g., radical constructivism and “Cybern-Ethics” (von Förster and Ollrogge, 2008; McNamee and Hosking, 2012), multi-directional partiality and neutrality (Boszormenyi-Nagy and Sparks, 1973; Cecchin, 1987), and a both/and-attitude toward a disorder-specific vs. non-disorder-specific systemic therapy (Lieb, 2009). Characteristics of the habitus encompass acting, rehearsal, and playing, in contrast to simply sitting and listening. A flexible composition of the therapy setting is the norm, allowing single- to multi-person conversations as well as setting changes.

Therapeutic conversations can include one client or a couple, the family, colleagues, superiors and professionals from various institutions (e.g., the school, youth welfare office), social workers, and doctors. Psychotherapy as cultural practice takes place not only in sacred spaces such as the therapy room, but also in profane places such as the home, in schools, the office, or playgrounds. The location, frequency, duration, and number of therapy sessions vary greatly depending on the clients’ concern and the context of the therapy. In our Heidelberg practice-research group, we developed an Integrative Systemic and Family Therapy (ISFT; Schweitzer et al., 2020). The ISFT includes the therapeutic stance, rationale of disorder and intervention as represented by collective psychotherapy cultures and applies it to social anxiety disorders. It was examined in a feasibility study and showed trends toward positive therapeutic change when compared to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT; Hunger et al., 2020; Hunger, 2021).

The ISFT grounds in radical constructivism (Gadenne, 2008): cognizance emerges within a creative process of constructing various realties (“multiverse”; Tjersland, 1990). The existence of objective facts is not denied, but the epistemological relevance of the world’s ontological representations is challenged (McNamee and Hosking, 2012). Radical constructivism, and with it the idea that every observation essentially depends on and is influenced by the person that makes the observation, builds the epistemological counterpart to second-order cybernetics (Maturana, 1987; Bateson, 2000). Contrarywise, first-order cybernetics is limited to the reciprocity of the different parts, i.e., members, of an affected social system (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1977).

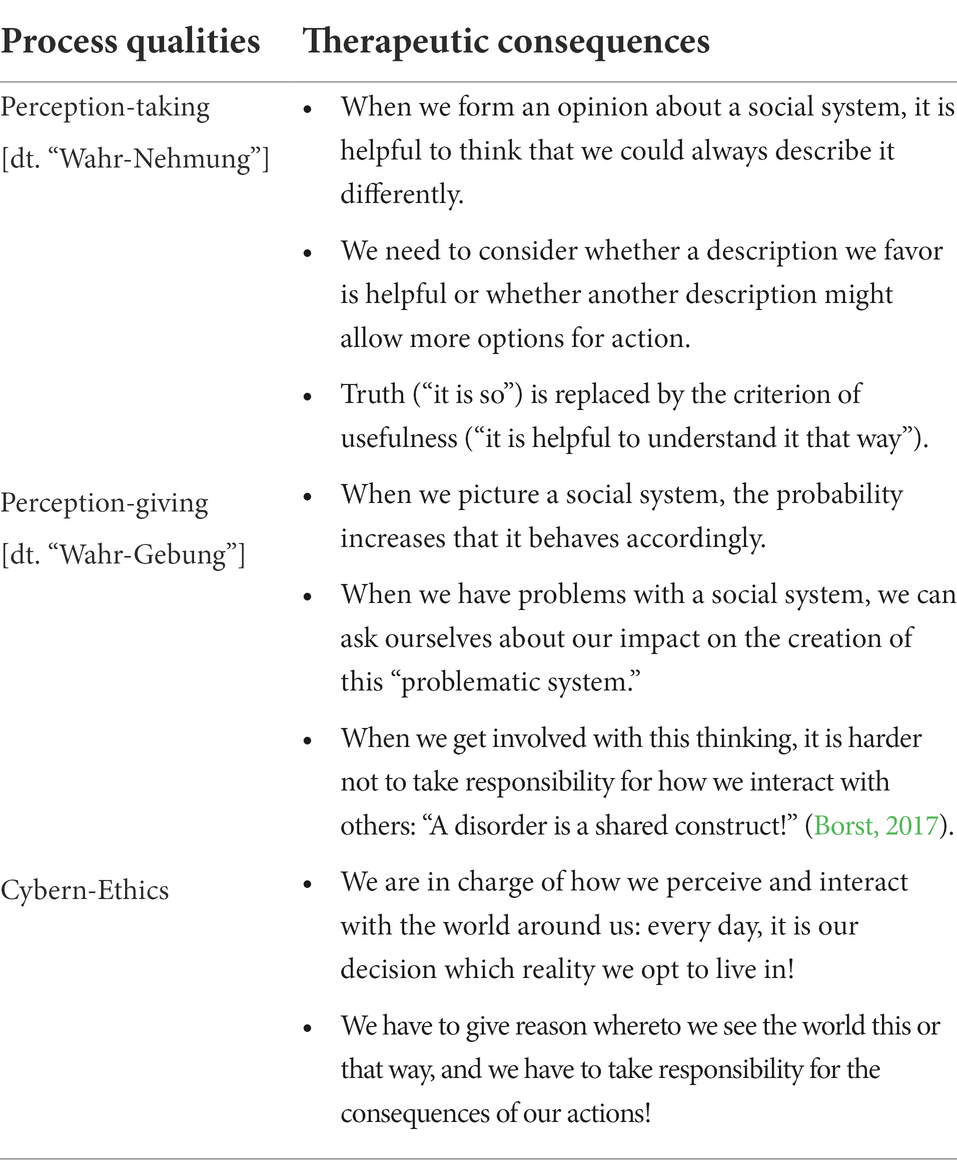

Every communication and interaction is subject to complexity-reducing observation processes (“perception-taking” [dt. “Wahr-Nehmung”]). On the one hand, our brain selects a few explanations from a wealth of possible explanations: we perceive something. An example: even though the consciously visible spectrum (light) is between 380 and 780 nm, we do not consciously perceive UV or infrared radiation due to our biological condition. Likewise, cultural, social, familial up to individual and (epi-)genetic imprints determine which information we select as significant. On the other hand, it is a matter of meaning-making in (un)conscious reciprocal reaction to what is perceived (“perception-giving” [dt. “Wahr-Gebung”]). Another example: Someone who reacts to a marriage proposal with the answer “yes” gives a social system, e.g. spouse to be, parents-in-law to be, own parents and friends of the couple, a fundamentally different information compared to someone who says “no.” If we follow the reciprocity of “perception-taking” and “perception-giving,” our base of possible beliefs in objective facts thus begins to dodder. Ethical points of view no longer ground on the suchness of the world. What remains is an increasing taking of responsibility on how we encounter and can influence the world around us (“Cybern-Ethics”) (Table 1; von Förster and Ollrogge, 2008).

Table 1. Radical constructivism and Cybern-Ethics (von Förster and Ollrogge, 2008; Schweitzer et al., 2020; Hunger, 2021).

In the ISFT, the core therapeutic stance embodies multi-directional partiality (neutrality), i.e., the unconditional respect of the (1) meaningfulness of symptoms, (2) ambivalence to (not) change, and (3) autonomy considering the question of who attaches importance to which therapeutic offers. Multi-personal perspectives lean on the phenomenon that social system members primarily follow their own meaning-making, which does not necessarily generate social realities compatible with other social system members. Construct neutrality addresses the co-existence of different explanatory models regarding the emergence, maintenance, and change of problems and solutions. The core question is about the purpose of preferring one reality over the other. Loss of construct neutrality is reflected in the unidirectional favoring of a specific explanatory model. At worse, this merely is the explanatory model of the therapists while neglecting the clients’ point of view. Relational neutrality occurs when relationship offers are made equally to each social system member and no one is addressed more strongly compared to others, at best while conceding similar speaking times to each social system member. Problem-solution-neutrality grounds in the equal validation of change and no-change. It is considered lost, if one holds on to the imperative that the affected social system must change although it still needs time in the problem space, and vice versa. (Loss of) neutrality is not a static event, but a dynamic-interactive process that oscillates in time and requires reciprocal client(s)-therapist(s)-communication. The ISFT therefore uses brief supervisions where, e.g., clients are asked: “As family members, do you experience yourself as equally seen and valued by us therapists, or is there any favouritism?” (Cecchin, 1987; Schweitzer et al., 2020; Hunger, 2021).

In the development and piloting of the ISFT, we often discussed the need for how much, and whether at all, we needed a disorder-orientation. Lieb (2013) discusses four positions and argues for a both/and attitude, which we prefer for the ISFT as well. It includes the unification of the positive aspects of and discourse with experts from other therapeutic positions. We remain neutral toward the symptoms, not labeling them as good or bad, but primarily as meaning-making (Emlein, 2010). We understand disorders as the striving for the best solution at a particular time in the context of a significant transition (Schweitzer et al., 2020). According to Cybern-Ethics (Table 1), diagnoses are understood as a consequence of social negotiation and above all are subject to the question whether they are of use to the affected social system (utilization principle; Hammel, 2011). They embody attributions vs. intrasystemic or intraperson truths (Hacking, 1999, 2006). Diagnoses are the link to those who work with clinical codes (e.g., physicians, psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and health insurance companies). In the ISFT, they are used if clients call for them (e.g., “Now this ‘something’ has a name!”), and if they serve the social system (e.g. “The symptoms, i.e., this disorder, is my protective shield against overburdening!”). Nevertheless, the main focus of ISFT still is the exploration and testing of other ways of creating meaning (Schweitzer et al., 2020).

Social anxiety disorders (SAD) are one of the most prevalent mental disorders (lifetime prevalence: 7–16%), with high impact to those who constitute a social system that includes SAD. The core symptom of SAD is the fear of rejection, ongoing for at least 6 months in one or more social interaction or performance situations while being confronted with unfamiliar people. The social situations are avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety. SAD is associated with considerable psychosocial handicaps, and increased risk for comorbid disorders and suicidality (Ruscio et al., 2008). Remission rates are low (e.g., 20% in the first 2 years) compared with affective and other anxiety disorders (Yonkers et al., 2003).

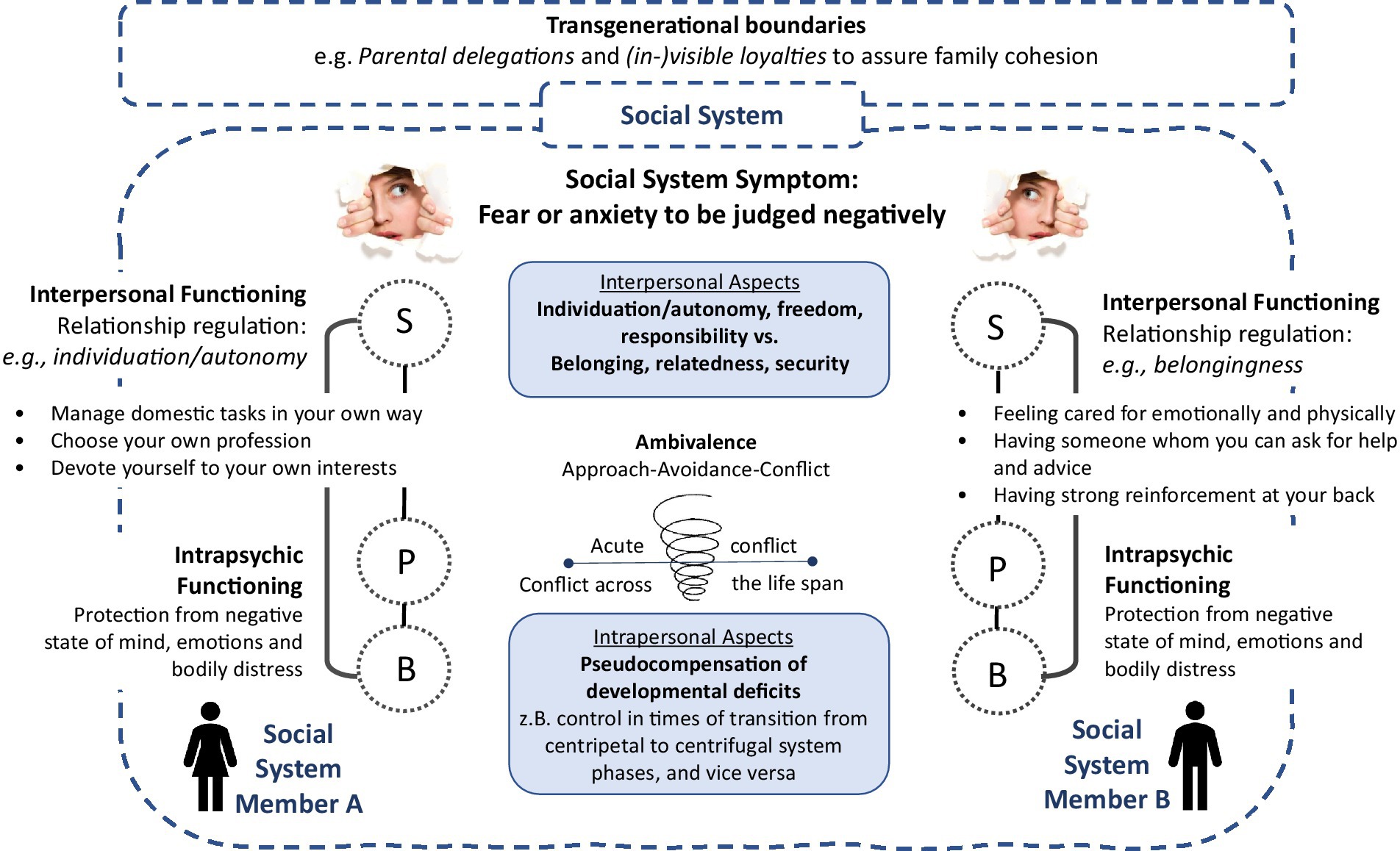

In the context of the ISFT, we do not understand social anxiety as a mischief and troublemaker but to some degree as reasonable or even useful. It triggers adaptive self-organization (e.g., adolescents moving out of parental home; parents focusing on (re)available times), use of innate behavioral programs (e.g., endorphin release in times of crisis), and adaptive modification as well as reorganization of neural networks (e.g., learning from experience). Social anxiety appears as an existential experience and a component of everyday life (Hüther, 2008), including various aspects of inter- and intrapersonal functioning as depicted in the socio-psycho-biological explanatory model adapted to social anxiety (Luhmann, 2017; Hunger et al., 2018; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Socio-psycho-biological explanatory model adapted to social anxiety (Luhmann, 2017; Hunger et al., 2018; Schweitzer et al., 2020). S, Social system (verbal and non-verbal communication and interaction); P, Psychological system (thoughts, emotions); and B, Biological system (corporeal parameters).

In terms of interpersonal functioning, we understand social anxiety as an indicator, i.e., the symptom, of unsatisfactory social interactions between at least two social system members often emerging from an unresolved developmental process that affects the whole social system. It may arise as a mismatch of, e.g., one’s sense of belonging while on the other hand striving for the exploration of the world, in need for individuation, or autonomy. Children or adolescents with SAD may thereby ask themselves and others: e.g., “How can I become independent without losing contact to my parents?” (related autonomy); “How do I want to face the world, and as who?” (self-image); and “What friendships do I want to maintain, and how do I want to encounter superiors compared to my parents?” (social contact). Parents can similarly ask themselves and others: e.g., “How can I become more autonomous (again), take advantage of (new) freedoms, and still stay in touch with my descendants?” (related autonomy); “What do I (still) want to experience in the world, and as who?” (self-image); and “What friendships do I want to (re)intensify, and what parts of my personal and/or professional life do I want to expand?” (social contacts). It is precisely these questions, among others, that therapy is concerned with, and which are addressed in the ISFT. The concept of Related Individuation (Stierlin, 1976) follows this idea. Relatedness, and belonging, describe the experience of being an acknowledged member of a social system. This is shown through being respected and welcomed, and of forming and maintaining significant relationships with others in the social system. Belonging is essential to protecting the boundaries of the social system. Individuation describes the standing up for one’s own needs and implies the understanding that rights, responsibilities, appropriate indebtedness, closeness, and distance can be negotiated. Both relatedness and individuation can be understood as two sides of a coin which together are essential for the growth of individual social system members as well as the social system as a whole. A well-balanced Related Individuation allows for the establishment of a new social system, e.g., conjugal family, without having to abandon ties, e.g., regarding one’s own family of origin. In SAD, symptoms serve the prevention of openly communicating desires of freedom which is associated with threatening the existence of the social system. Instead, they weld all social system members together. However, the desire for appropriate distance persists as seen in (non)verbal communication and interaction (e.g., relationship breakdown, aggression). The successful resolution of entangled social relations therefore requires a co-evolutionary process of the social system as a whole, in which all system members are significantly involved.

In terms of intrapersonal functioning, we see social anxiety as kind of intrapsychic gain, e.g., when it serves the prevention of negative emotions (e.g., fear and anger) and as pseudo-compensation for developmental deficits of the social system in the transition from a centripetal phase with narrow family ties (e.g., in times of a newborn) to a centrifugal phase with looser family ties (e.g., adolescents’ moving out of home). Social system changes can be frightening when failure seems imminent and with it the threat of the social system’s existence (e.g., breakup of the family of origin). Avoidance of anticipated negative consequences, however, reinforces the idea of existential threats, and thus reciprocally produces what is attempted to be avoided. Spill-over effects of negative communication and interaction patterns, emotions, and thoughts, finally cause a sometimes very pronounced socio-psycho-biological impairment of the various social system members (Priest, 2009).

Transgenerationally, significant social system patterns have an impact on the inter- and intrapersonal perception of the social anxiety. Social restraint, e.g., a “keeping one’s head down,” may have been essential for survival in wartime. Parental delegations, e.g., a “make it the same like me as your father/mother” may serve as (in-)visible loyalties (Boszormenyi-Nagy and Sparks, 1973; Stierlin, 1976), fostering family cohesion. Every detail of a family biography becomes part of a multi-layered pattern that co-determines the identity of the social system members in the here-now. The past becomes the prologue (Petry and McGoldrick, 2013). However, once the war and/or delegation is over and one steps out of the group, social anxiety prevents the successful mastering of the developmental challenge. It emerges as a maladaptive and repetitive prophylactic power play that unravels along the question of who defines the relationship and how (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1977; Hand, 2002). This may be the clients with SAD motivating their partners to protect them, who finally take over all activities, above all those outside the home. This can also be the partners who put a stop to the clients’ less trusting behavior, e.g., by interrupting the excessive preparation of a speech and inviting the client as a partner to go for a walk. Sense-making becomes the central phenomenon. In terms of meaning-making, one person has to communicate, and another person has to perceive what is communicated as meaningful (e.g., by understanding the utterance, “Please accompany me to psychotherapy!”). The person has to connect (e.g., by agreement or disagreement: “I would never let you leave alone at home!,” or “I think you can manage quite well without me!”; Emlein, 2010). If this sense of reference (focus) is missed, disorder-specific symptoms can become the organizing principle of the social systems’ inter- and intrapersonal relations (Luhmann, 2017).

A detailed description of the ISFT can be found in the ISFT manual (Schweitzer et al., 2020). For this paper, we choose those aspects which we experience to be central components of the ISFT but less known in their disorder-specific choreography in the systemic community.

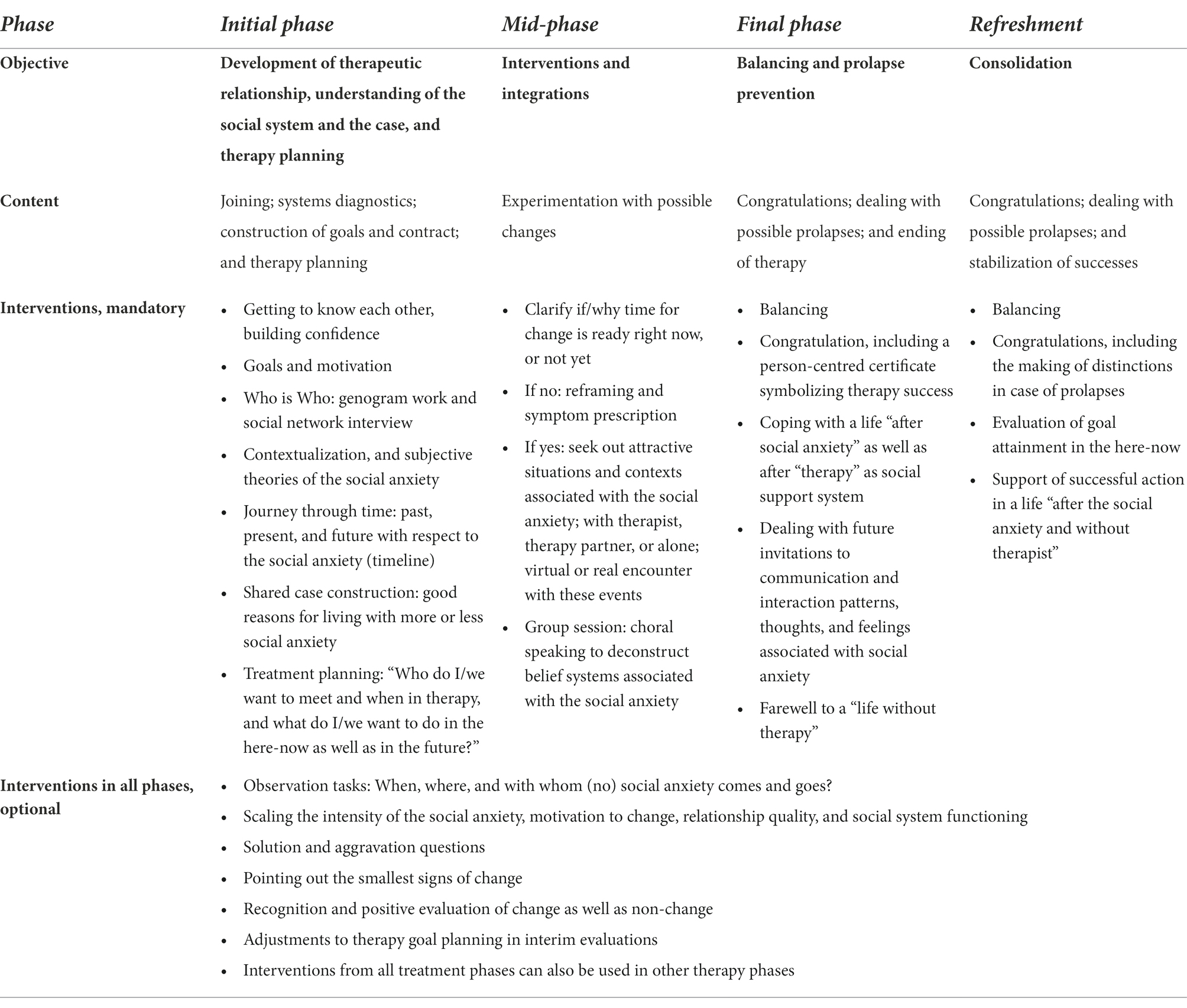

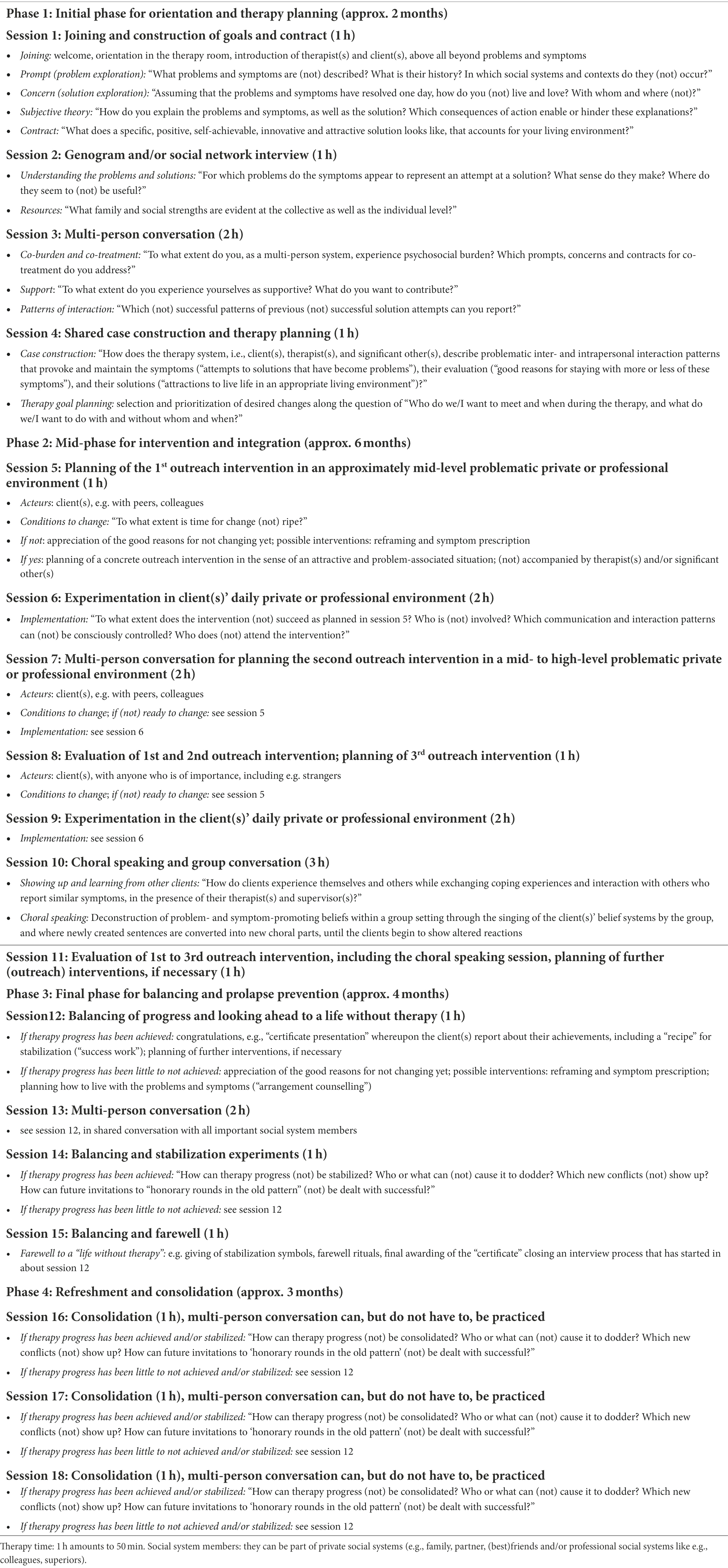

In the ISFT we distinguish four therapy phases with approximately 25 therapy hours, including different objectives with mandatory as well as optional interventions (Table 2, for an overview of the composition of interventions; Table 3, for an overview of the therapy structure). The practice of the ISFT allows for a certain degree of flexibility which seems essential to us when speaking of a client-centered therapy process orientation. The initial phase ideally comprises four sessions with five therapy hours, but in the case of more multi-person conversations it, however, can be fruitful to extend this phase and use therapy hours from other therapy phases such as the mid-phase which, in turn, will then be carried out in a more streamlined way. The same applies when, e.g., the initial phase appears to be finished after three therapy hours, so that the mid-phase begins in the fourth therapy hour. Ideally, the ISFT should be completed in about 22 therapy hours, with three sessions for consolidation after about 6-, 9-, and 12-month post starting the ISFT.

Table 2. Objectives depending on the therapy phase, with mandatory as well as optional interventions (Schweitzer et al., 2020).

Table 3. Course of ISFT in social anxiety disorders, ideal type (Schweitzer et al., 2020) The number of multi-person conversations is perceived as the minimum of sessions where significant social system members are involved. It is welcomed to increase multi-person conversations up to a complete multi-person therapy.

Multi-person conversations and outreach interventions in the social reality of the client’s daily life can be used as single sessions of 50 min or double sessions of 100 min. The choral speaking is conducted as a group session of 150 min. Other variations are conceivable: e.g., therapy hours can be subdivided and complete a week with a debriefing of 25 min after an outreach intervention of 125 min a few days ago; e.g., several sessions of 25 min each can serve a kind of “therapy break” after therapy goals have been (partly) achieved, and for the stabilization of significant changes.

From our point of view, each manual is an ideal suggestion from which there are good reasons to deviate from in individual cases. It seems optimal to us to take the ISFT manual sufficiently seriously, but not too seriously. This is the reason why we use bullet points instead of numbering in the description of mandatory and optional interventions (Table 2). All interventions are interchangeable in their order. Even therapy planning in phase 1 can be started in the first therapy hour. In particular, it is important to define with the clients which duration and intensity, for both the single therapy session as well as the intervention, seems most useful under which circumstances.

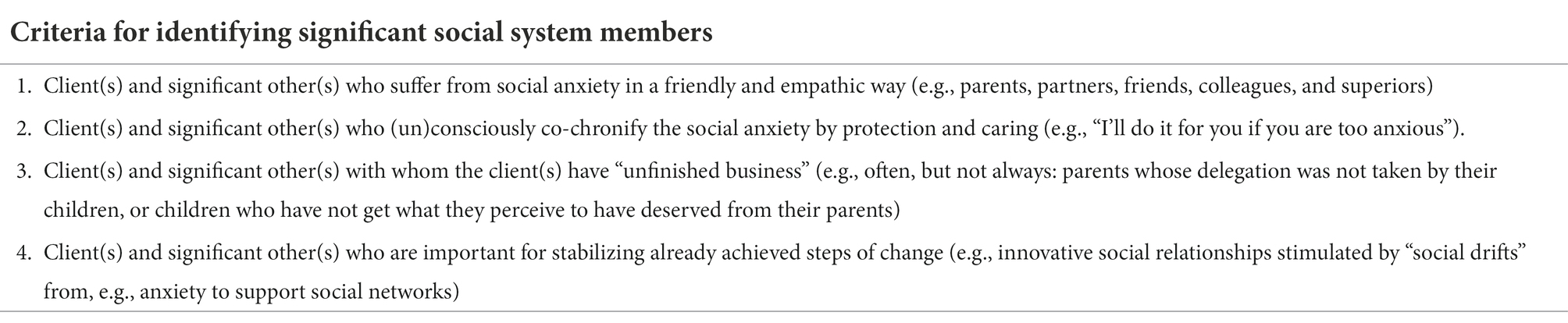

The aim of multi-person conversations in the ISFT is to get a shared idea of who is involved in the development, maintenance, and change of the presented problems and symptoms, and who can participate in the therapy process. It is about exploring who has the power to offer optimal support as well as to worsening the situation. Especially in the initial phase, it seems favorable that the social system members are bound to a secure and safety therapeutic atmosphere that may empower them to give each other their “blessing” in trying out changes. Changes may address distancing movements (e.g., leaving parental home; acceptance of full-time jobs by both parents) as well as approach movements (e.g., trustfulness in family cohesion while announcing a job engagement; becoming an artist, that was not part of the family history yet, e.g., in a family of engineers). The social system members can often better support the interventions when they feel to be integrated, and the change process starts to be more self-sustained. It also becomes clearer who is burdened and how: this is of special interest above all in cases when so-called “index client(s)” appear(s) to be the last stable unit of an affected social system. They can still have the power to call a psychotherapist in contrast to other social system members who have not the power to care for themselves anymore. We call such phenomena a “claim of psychotherapy on behalf of others.” Multi-person conversations allow those who are protected and not apparently at the center of the psychotherapeutic action to be involved in psychotherapy anyway. Hence, the first step is to explore who should be invited (Table 4). In the IFST, we use social network diagnostics (Hunger et al., 2019; Braus et al., 2022) and genogram work (Petry and McGoldrick, 2013) to better understand the composition of affected social systems and their current as well as transgenerational social relationships.

Table 4. Inviting social system members into therapy (Schweitzer et al., 2020).

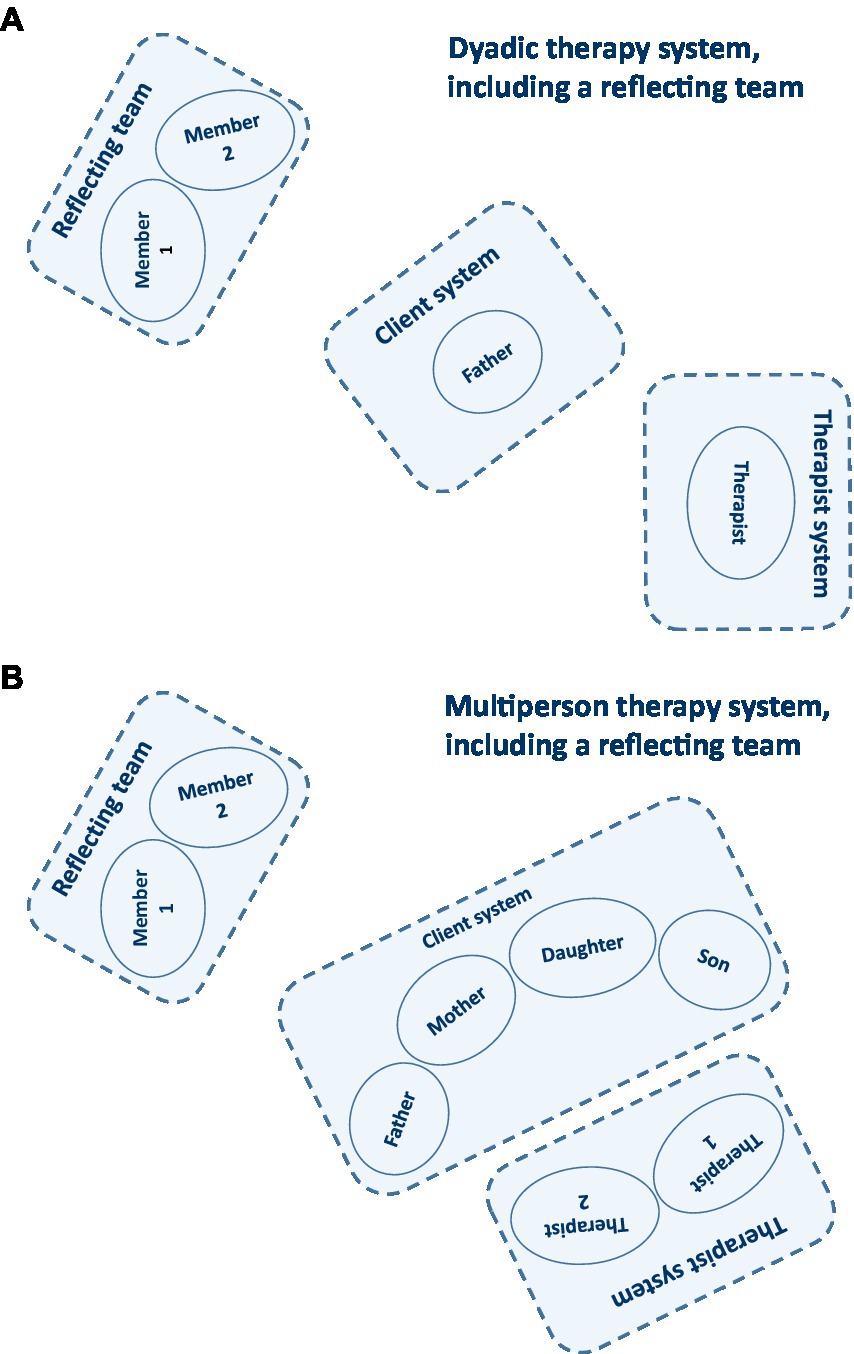

In order to give transparency to therapeutic processes and empower clients as autonomous entities, reflective teams can be installed in each ISFT session. The epistemological background refers to radical constructivism and the assumption that there are as many truth(s) as persons participating in the therapy, including therapists (Andersen, 1991). The forming of a meaningful difference then requires questions that have not been addressed by the clients nor the therapists. Reflecting teams strive to consider what constitutes the clients’ (dys)functional communication and interaction in the sense of first-order cybernetics, and to provide a positive connotation of how to communicate and interact with each other in the sense of second-order cybernetics.

In tradition to the Milan approach (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1975), we install reflecting teams directly in the therapy room. As a subsystem observing the therapy process, the position of the reflecting team is characterized by distance while being turned towards the clients and therapists at the same time (Figure 2). The reflecting team listens attentively and formulates questions, first inwardly and later verbalized, on how the symptomatology can be explained alternatively. After a certain period of time, and in consultation with the clients, the therapist asks the reflecting team for its perceptions, including ideas and questions to what they have perceived so far. The reflecting team members talk to each other but neither to the clients nor the therapist. They talk about their perceptions (“I perceive...!”), not about truths. Likewise, they ask themselves questions that they assume to contribute to a meaningful difference in the clients’ communication and interaction patterns (“...and I wonder...?”). Subsequently, the therapist binds back to the clients and, in turn, asks for their ideas and questions in response to what they have perceived on the part of the reflecting team. The clients are thus invited to co-create a conversation about the reflecting team’s conversation about the therapy system’s conversation. A self-referential and self-organizing dialogue (autopoiesis) emerges about what serves to control the clients’ self- and social system-preservation (first-order cybernetics) and how this control can undergo change (second-order cybernetics). The polyphony as perceived by the clients as well as therapists, and the reflecting team’s example that this polyphony can be heard and benevolently negotiated, is considered a central mechanism of change in systemic therapy (Andersen, 1991).

Figure 2. Therapy systems: (A) Dyadic therapy system, including a reflecting team; (B) Multi-person therapy system, including a reflecting team (Hunger, 2021).

We perceive clients especially at the beginning of therapy, and despite their apparent problem orientation, not at the low point of their crisis. If that were the case, they would not pick up the phone to call a complete stranger but rather try to avoid any contact with people unknown to them! Clients who enter psychotherapy have usually gone through a longer decision-making process and have certain ideas of what they hope to achieve, often with less informed expectations of what awaits them (Prior, 2010).

We try to meet as early as possible with the clients’ motivation, their pronounced suggestibility, and openness for new information as well as influences. The initial phone contact (approx. 20 min) serves as a first encounter between clients and therapists, and the radical constructivist and solution-oriented stance of the IFST. The first aim is to form an idea considering the symptom context. We ask the clients for a heading for their concern: e.g., “Finish the son’s apprenticeship—even if it costs our family life!” The clients are invited to sketch their therapy goal which we support with respect to a positive goal formulation: e.g., “You would be happy to see your son with a professional degree that fits well to his competencies and inner wishes, and that you both stay alive in this family process?” When therapists experience the clients’ concern as appropriate in terms of the proposed therapy, and clients agree to this, an appointment is made. The second part of this initial phone call serves the enculturation into the initial face-to-face conversation along three main topics. We ask clients if they would like to know about our interests in the first therapy session, and this question is almost always answered with a “Yes, I’d love to.” (1) We reaffirm our interest in possible solution scenarios, introducing the miracle question: “The first thing I, as a therapist, will be particularly interested in is your goals. It is important to me that we, together, develop a clear picture of where you want to be at the end of our shared time. If we assume it goes optimally and you finally say goodbye with the words ‘I am now where I wanted to be!’, I would be interested in: ‘Where are you then? How will you feel about yourself and others? What will you do differently?’ I’ll bring a lot of questions like this to our initial face-to-face conversation because I want to make sure we are pulling in the same direction.” (2) We also are interested in problem-solving strategies tried so far: “I’ll ask you in our first face-to-face conversation: ‘What have you already tried to approach your goal?”. There will certainly be some action that has made the problem smaller, and some action that has tended to make it worse. I’m interested in both: the successful, because perhaps we can do that more, and the unsuccessful, because this can save us from going in a wrong direction. Does that make sense to you?” (3) We finally point to the recognition of possible changes from now on till the first face-to-face encounter: “I finally will be interested in the good things that may have happened between our contact today till we meet face-to-face. Research has shown that over 70% of the clients who book a therapy appointment experience an improvement between these two events. This can be a small improvement as well as a very significant one—all the way to the rare case where therapy is no longer needed at all. So, I would ask you to simply pay attention to possible changes.” The clients receive these questions together with the appointment confirmation by post. If multiple members of an affected social system are involved, the initial phone contact is conducted with each system member (Prior, 2010). The initial face-to-face conversation follows the choreography of the initial phone contact.

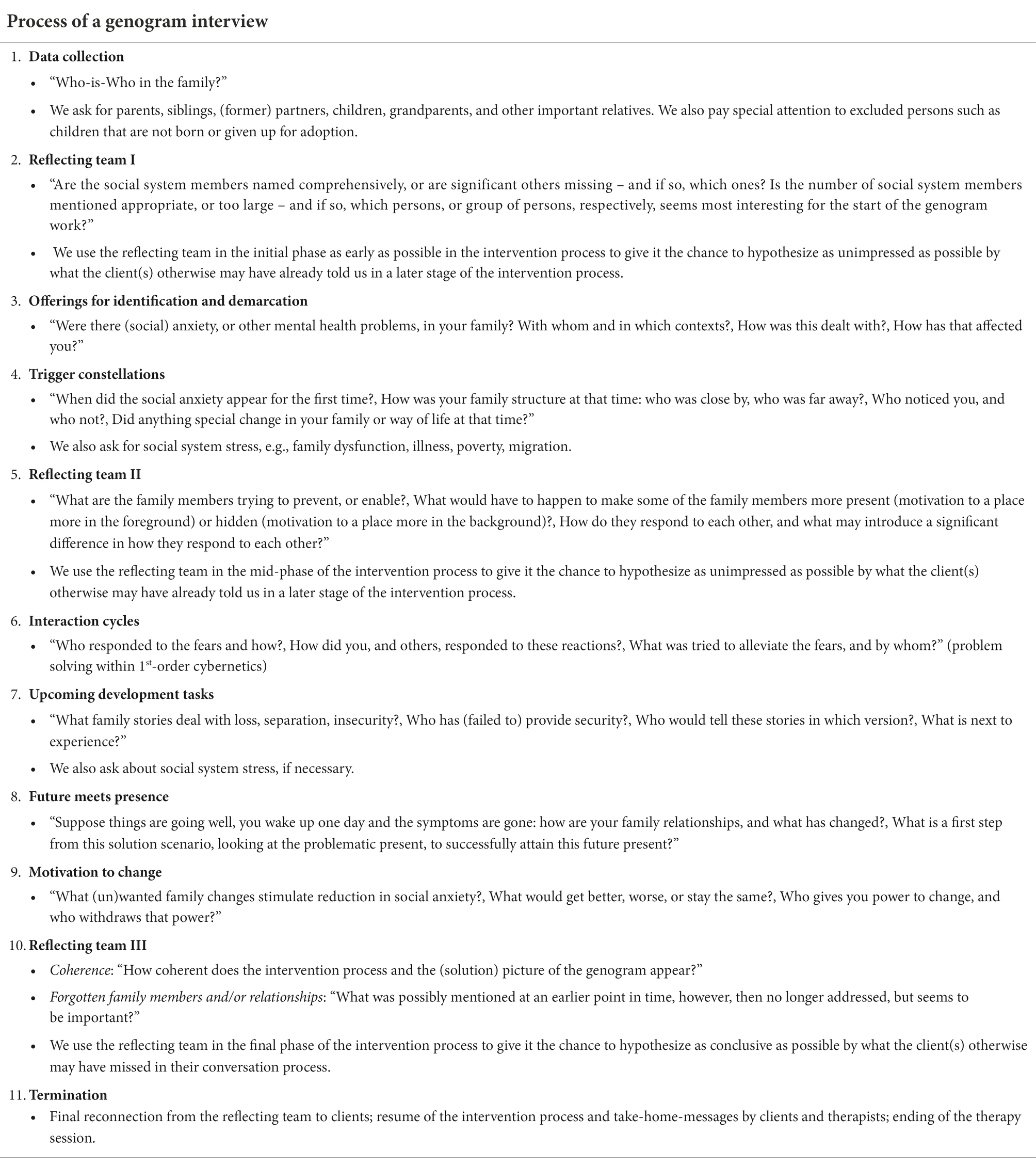

Another meaningful part of the initial phase is to gain a better understanding of the structure and characteristics of the affected social system. We use genogram interviews (Petry and McGoldrick, 2013) to facilitate a pronounced transgenerational system perspective of the social anxiety. Genogram work according to the ISFT includes the identification and demarcation of social anxiety in the family and its history, social trigger constellations for social anxiety and social interaction cycles for its alteration, upcoming developmental task not approached by the family but indicated by the social anxiety, solution scenarios and the motivation to change. Reflecting teams can be used at any time to broaden the perspective of clients and therapists (Table 5).

Table 5. Genogram interview in the context of social anxiety (Schweitzer et al., 2020).

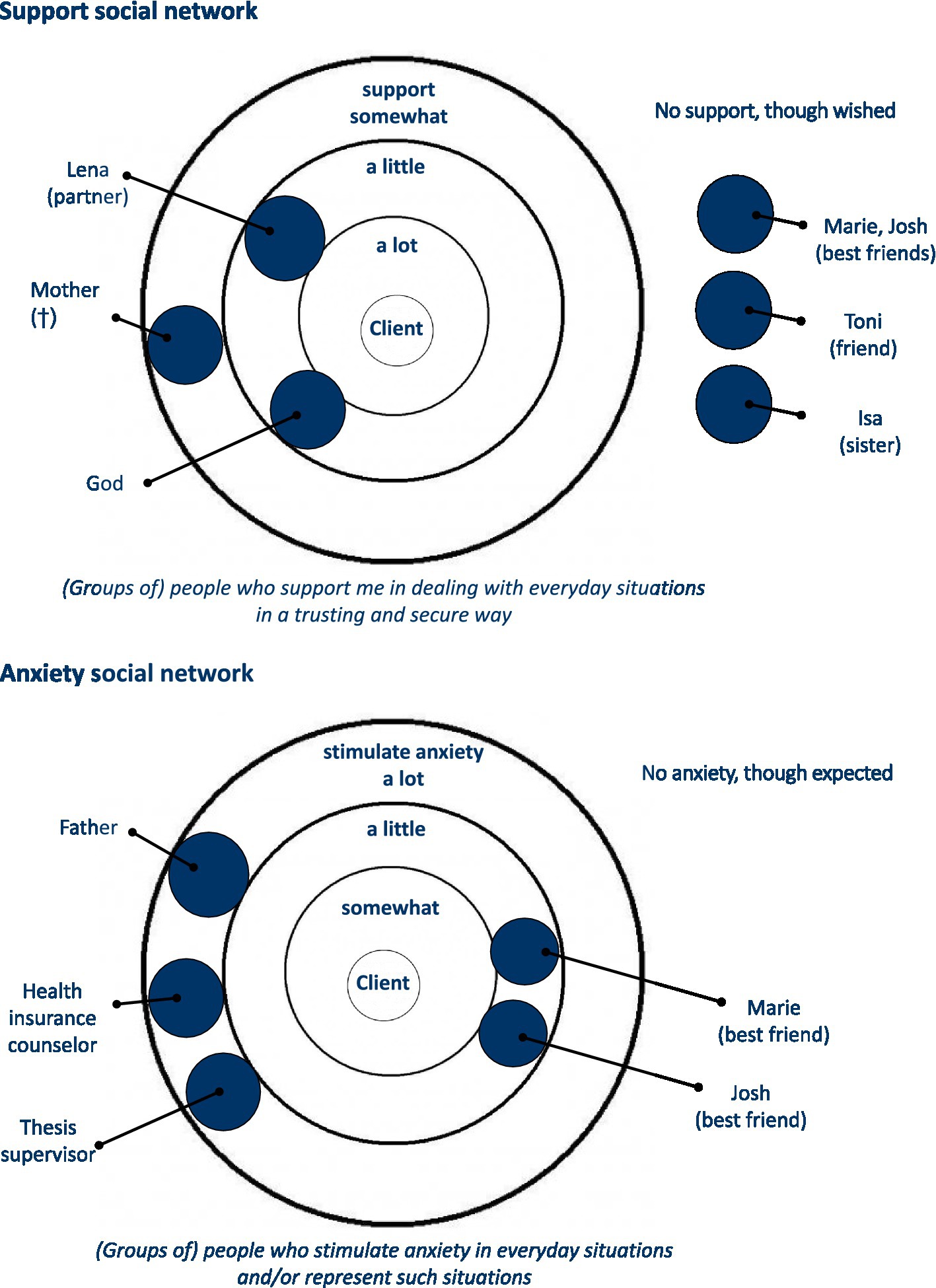

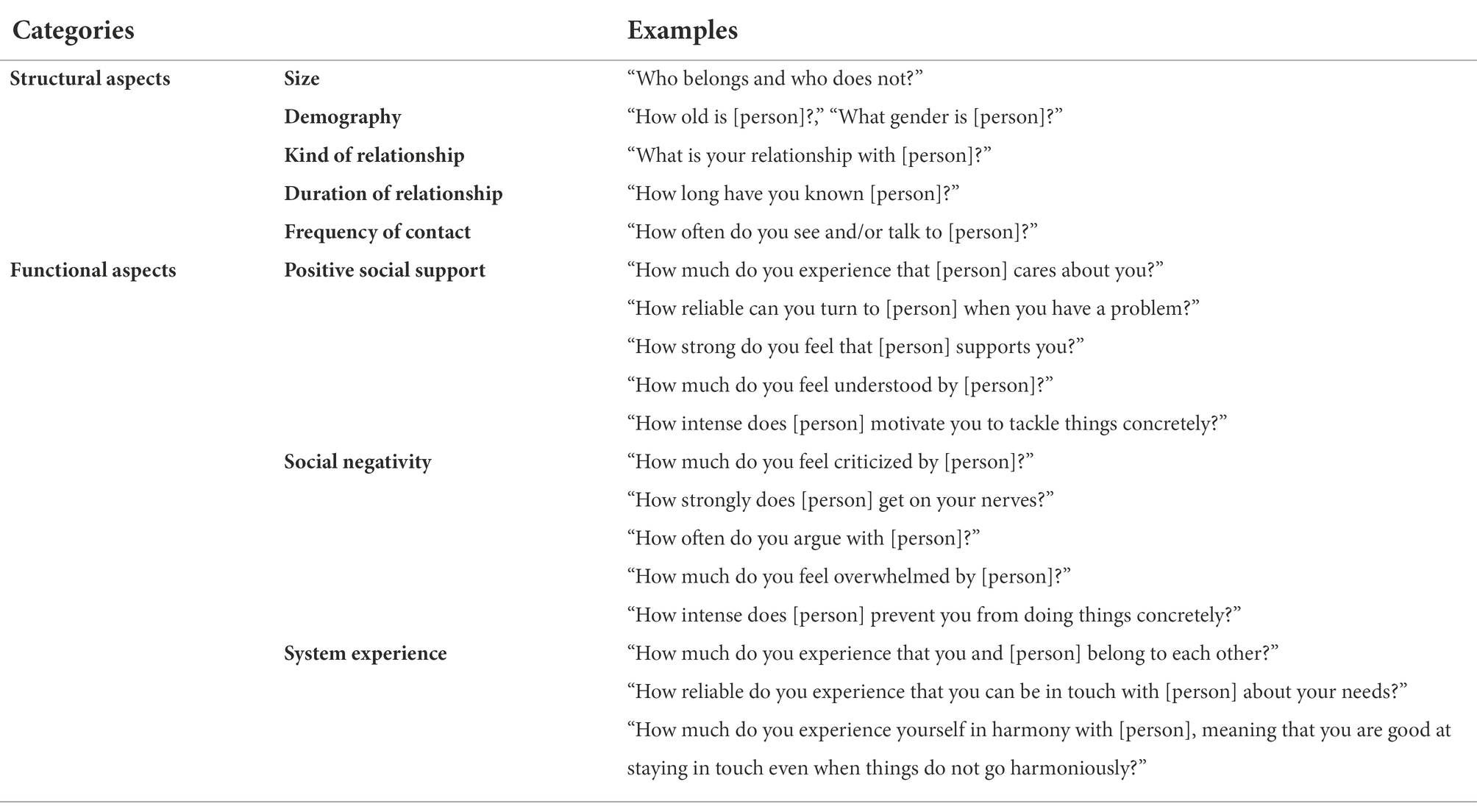

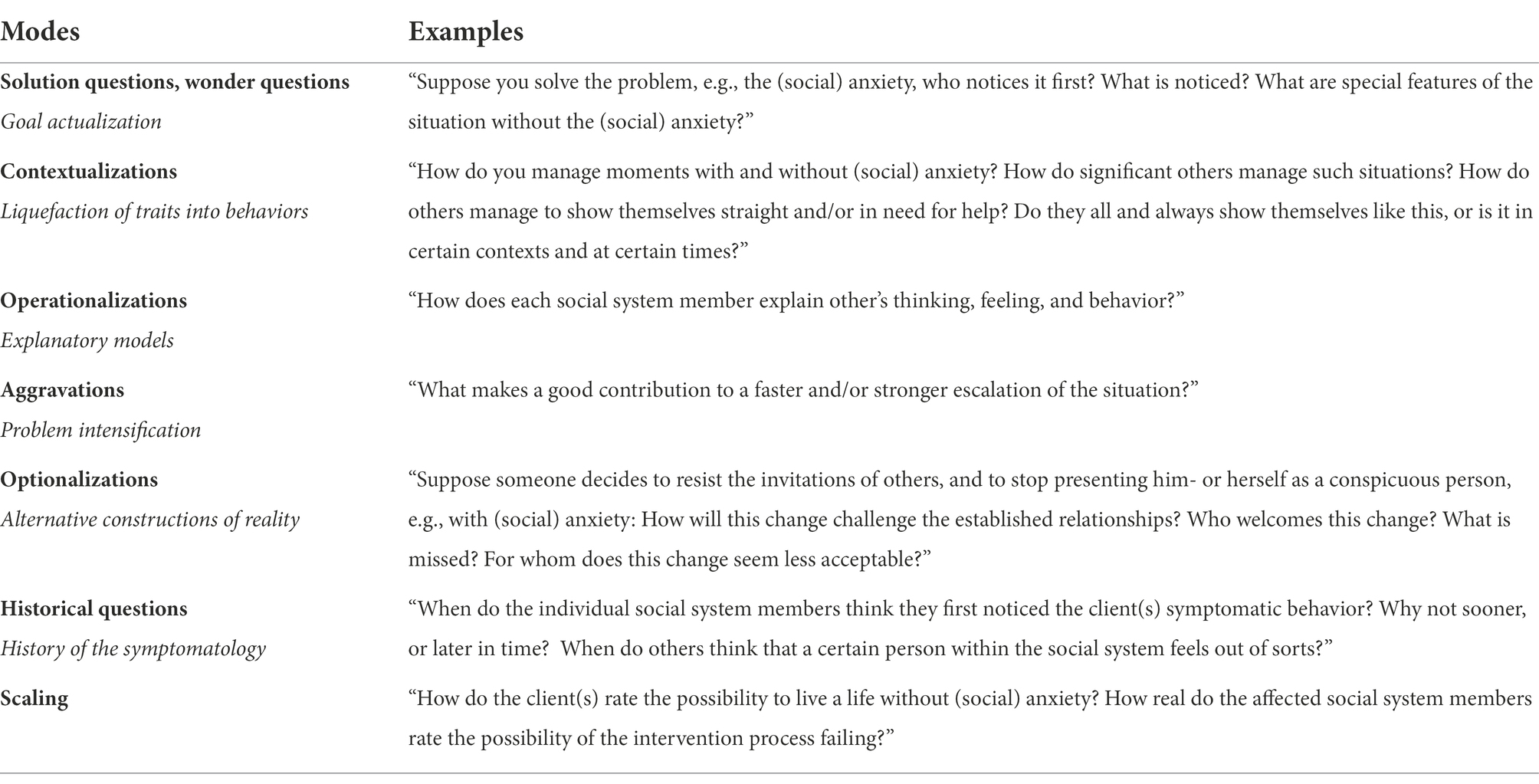

Genograms, however, are limited to biological and legal relationships. They do not well include significant others, e.g., friends, neighbors, colleagues, and co-workers. We thus developed the Social Network Diagnostics (Hunger et al., 2019) to better understand the structure of the affected social system including all important social system members, while keeping in mind that an appropriate number (quantity) and prosociality (quality) of social relations characterize well-integrated social networks (Eaker et al., 2007). The Social Network Diagnostics uses a semi-structured interview to assess the social system’s structure based on three concentrically arranged circles. We distinguish between resource-specific and disorder-specific social networks (Figure 3). The affected social system (e.g., “I” or “my family”) is positioned at the center of the circle structure. Resource-specific social networks, e.g., support social networks, ask for (groups of) persons who provide support for dealing with everyday situations in a trusting and secure way. The client(s) place wooden stones in the first, second or third circle representing the (groups of) persons who support him/her/them a lot/not so much, but also a little/somewhat. (Groups of) persons who do not give support at all, although wished by the client(s), find a place around the circles. Structural aspects such as the network size, demography, kind and duration of the relationship, and frequency of contact as well as functional aspects, such as positive social support, social negativity, and system experience are asked about for all (groups of) persons (Table 6). The same procedure is used in disorder-specific networks, performing an inverted arrangement of the concentric circles, e.g., anxiety social networks (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Support and anxiety social network (Schweitzer et al., 2020; Hunger, 2021).

Table 6. Structural and functional aspects of social networks (Hunger et al., 2019).

The initial phase ends with a circular focus formulation which is at the heart of systemic therapy. The circular focus formulation grounds in as precise a description as possible of how the social anxiety is linked with the disturbed communication and interaction patterns. It should well explain the emergence, maintenance and possibilities for change with respect to the social anxiety within the affected social system. The aim is to provide an approach how to alter the symptomatology while stabilizing previously identified resource-oriented relationships and modify problem-oriented communication and interaction patterns.

An example may serve as an illustration: A client experiences how the refrigerator is getting emptier, and he suspects that he will soon have to go shopping. He asks his partner to do the shopping. The partner reacts annoyed. The client’s body posture becomes more tense with each refusal. The partner shows increasing distance with each new request. Finally, it comes to a dispute, and the partner strongly annoyed leaves the room while the client strongly annoyed stays at home. The opportunity for a joint solution seems to have been missed. According to Rotthaus (2015), the following questions now can guide the process of working out a circular focus formulation:

1. “What is the function of the social anxiety with respect to (the prevention of) the further development of the affected social system? What message does it send to which system member?”

2. “What role do (invisible) loyalties play? Which family, individual and context-related communication and interaction patterns (e.g., attachment (in)security, devaluation, and exclusion) are part of the background of the social anxiety?”

3. “How have similar challenges been (not) successfully dealt with?”

4. “Assuming that the social anxiety has become redundant: how will the client(s) live, love, and work?”

Reframings serve the positive reinterpretation within the shared case construction. They enable reversals into the opposite, as well as role reversals when therapists occupy the position of the “sceptics,” valuing symptoms, and questioning change. Complementarily, they allow clients to take a more active position as “convincers that the solution is possible.” In a variation of Schwing and Fryszer (2006), the formulation of a good reframing follows a narrow sequence of five steps:

1. “What is it exactly that is disturbing you? Please, describe the socially anxious behavior and experience specifically.”

2. “In what contexts does socially anxious behavior and experience fit well, i.e., appears appropriate? In what situations was, and still is it, meaningful?”

3. “What skills become evident in the context of the social anxiety? What have/can you learn from it?”

4. “What good intention do you attribute to the social anxiety? What do you, and others, (un)consciously want to achieve (with the social anxiety)?”

5. “What alternative behavior and experience appear in the context of meaning-making and maintaining the good intentions of the social anxiety, thus taking advantage of it? How can you design the solution in a way that it still contains the positive elements of the problem?”

A circular focus formulation, including a reframing, can explain the function of the social anxiety in the above described couple: The social anxiety of one partner keeps hold of the social system by involving the other partner’s responsibility. The less one partner goes into contact with the outside world, the more the other partner takes over. Transgenerational (invisible) loyalties may operate in the background and motivate one partner more than the other to keep a low profile and not dare risk the encounter with others. The family history showed that avoiding attention was essential to survive in war times. This was truer for a Jewish family like the partner’s family of origin who indicated social anxiety symptoms. Now, however, the war is over, and the parents’ education continues to have an effect on this partner and prevents the further development of the couple as the affected social system. If the social anxiety becomes redundant, the previously social anxious partner explains that he would intensively like to enjoy the new freedom. This, in turn, provokes anxiety in the other partner, who up to now has represented the couple to the outside world, and was happy not take too great a leap. What is needed is not simply a solution to the social anxiety symptoms, but rather a shared construction of what life could be like without the previously shared social anxiety. This would include altered and healthier communication, and interaction patterns.

In this stage of therapy, it is important to try out potential opportunities for change (“experiments”). The therapeutic stance is of high importance, especially when outreach interventions and innovative solution scenarios are performed in the everyday environment of the affected social system. Relevant to action is an optimism for change without pressure to change, framed by caring humour while playing with symptoms and having fun with friendly absurdity and unusual experiments. Core interventions include the working with circular questioning and hypotheses (Penn, 1982; Cecchin, 1987), symptom prescription in accordance with the Milan approach (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1975), and choral speaking (Schweitzer et al., 2020; Hilzinger et al., 2021).

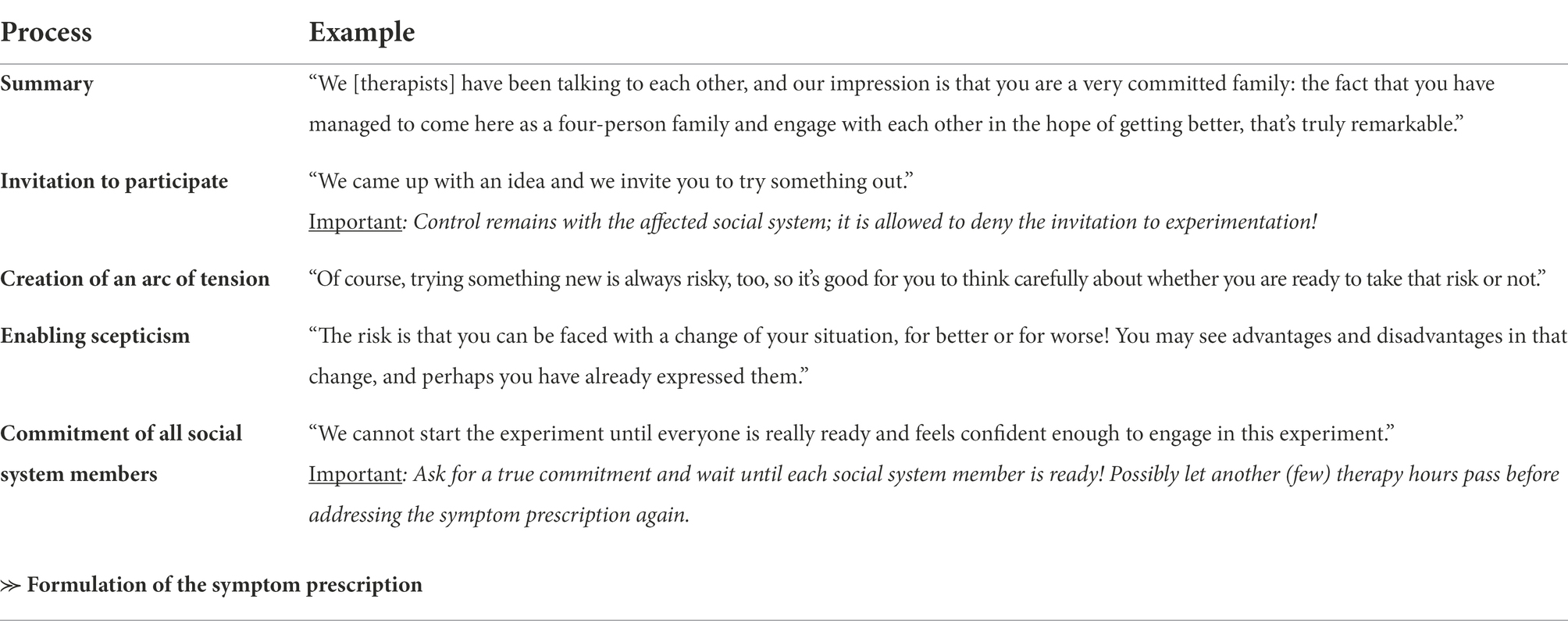

Systemic questioning and hypothesizing, especially addressing circular phenomena, allow a better understanding of the communicative and interactive vicious circles of an affected social system. Circular questions address dyadic interactions, e.g., when a therapist (A) asks how one person (B) thinks about another person (C). Similarly, triadic interactions can be considered when the therapist (A) asks how a person (B) experiences the interaction of two or more other persons (C, D, etc.). This way of asking may appear strange at first, but what is asked is part of our daily life: we do not only react to what others do, but rather to what we think others think about us (expectation–expectation). When all social system members are involved in the therapy session and experience what one system member thinks about the other, then everyone learns something new (Simon and Rech-Simon, 1998). The goal is to make clear that every communication embodies a content and relationship aspect and that in disruptive events it is usually less about the content but more about the underlying unmet needs within the social system. Well-informed alternative ways of communication consequently can be developed and tested for a more appropriate conflict resolution. There are various modes of systemic questioning that serve this purpose, including solution/wonder questions, contextualizations, operationalizations, aggravations, optionalizations, historical questions, and scalings (Table 7).

Table 7. Modes of systemic questioning (Hunger, 2021).

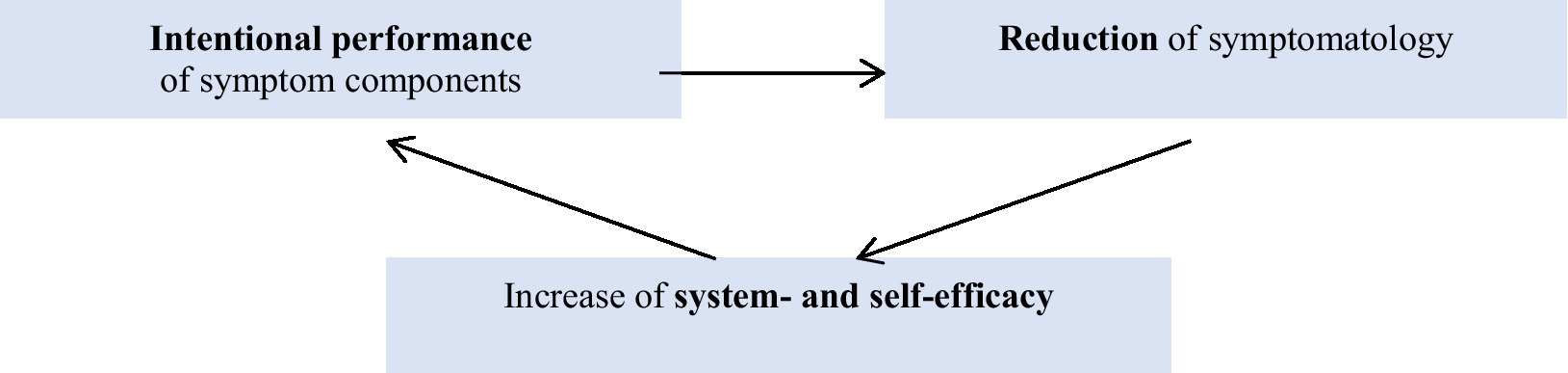

The Milan approach (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1975) was in close exchange with the Heidelberg School (Stierlin, 1976). Epistemologically, symptoms are understood as an independent element indicating the quality of an affected social systems, functioning. To introduce a difference in the therapeutic setting that makes a meaningful difference (Bateson, 2000), clients are invited to perform something unexpected, i.e., to intentionally (not) perform the symptom components (e.g., physiological, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional). This is associated with symptom reduction (e.g., less shaking and/or blushing in social anxiety disorders) or symptom escalation (e.g., strong shaking and/or blushing). The aim is no longer at the solution of the symptoms as this has already been tried many times in vain. Contrariwise, symptom prescriptions proved to be particularly helpful when change had failed, or too early changes bore the risk to threaten the survival of the affected social system. For example, symptoms of social anxiety may have been reduced from 6 h to 3 h the day before the performance of a speech; if, however, attractive alternative goals are missing, responding to the question with whom and what one will spent the 3 h of gained free time, suicidal tendencies can arise to fill the increasing emptiness.

The symptom components are usually prescribed in isolation. Positive symptoms (e.g., “Do [show, think, feel] what you already do [show, think, feel]”) can be addressed (e.g., “Try to sweat as strong as possible, and even stronger, before meeting strangers!”; “Shake so much that you tip over your glass of wine at the garden party and submerge your mother-in-law’s dinner!”). Likewise, negative symptoms (e.g., “Do not do [show, think, feel] what you do not do [show, think, feel]”) can be addressed (e.g., “Do not tell anyone that your career aspiration actually is totally different to your father’s ideas!”; “Be sure to stay at the bar next to the dance floor in the discotheque and by no means dance with your friends, even if your favourite song is playing!”).

“Such ritualized prescriptions of communication and interaction patterns create an exacerbation of the situation in a humorous way. They make clear what is going on, respect it as meaningful, and create a certain pressure not to keep up this nonsense” (Schlippe and Schweitzer, 2016, p. 334).

The goal of symptom prescription is to deliberately perform selected symptom components. The affected social system decides when certain symptoms are allowed to come on stage. This way of dealing with symptoms causes a reduction in the symptomatology and increases the affected social systems’ experience of system- and self-efficacy (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Rationale of symptom prescription (Hunger, 2021).

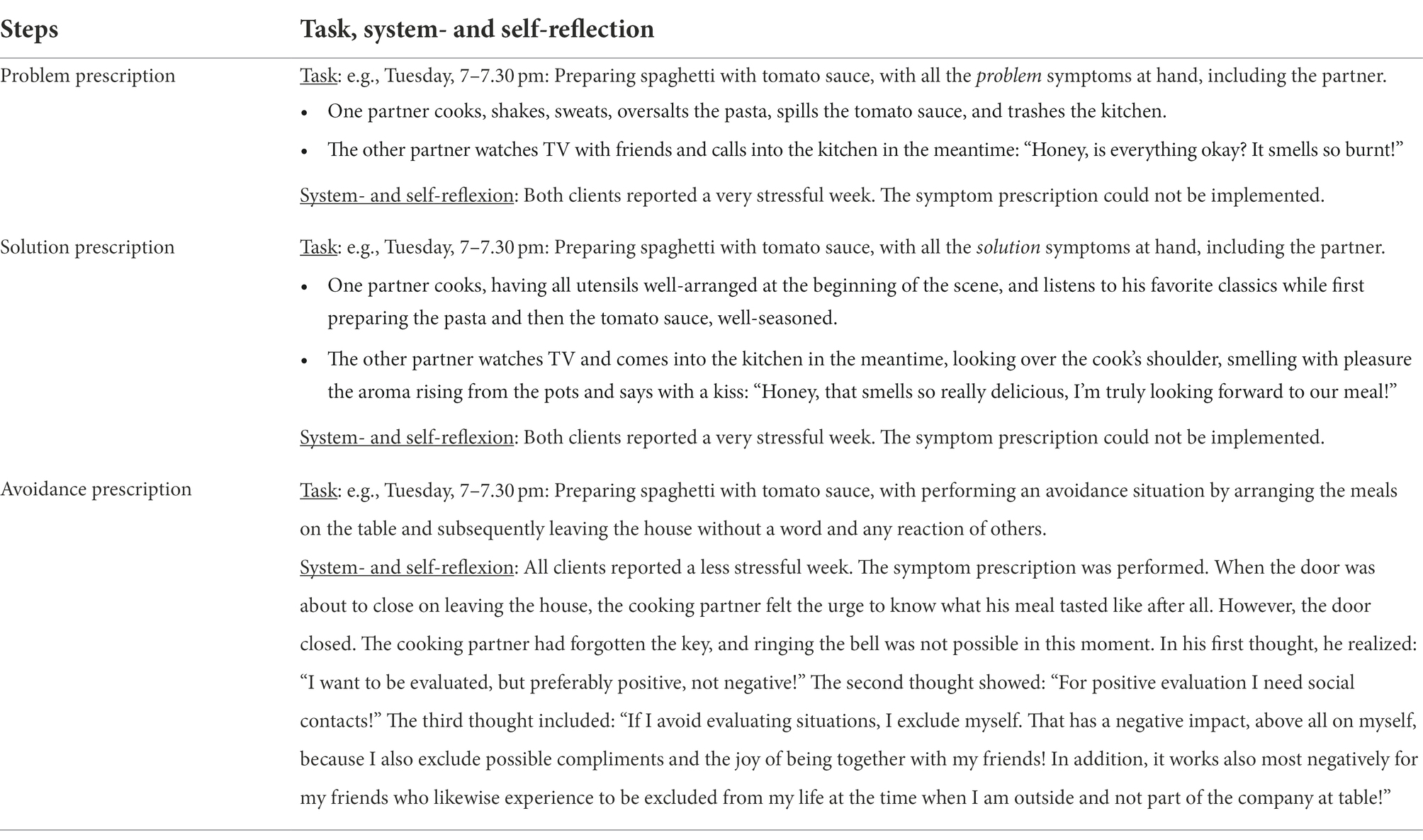

The framing of the symptom prescription can be performed as directive as in the 1970th Milan approach, including a confronting closing commentary (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1975). In the ISFT, we have adapted the Milan approach based on our experience in nowadays systemic therapy. Creating an arc of tension, options for scepticism on the one hand and the commitment of all social system members on the other hand are of particular importance to increase the success of the intervention (Table 8). In addition, we have developed a three-step approach by prescribing problems, solutions, and avoidances. The actual performance of the symptom prescription (in vivo) is as valid as its hypothetical enactment in the context of system- and self-reflection procedures (in sensu). It is important that the situation to be addressed, and the behavior to be proved, are planned together with the social system members and in accordance with their goals, resources, and the social contexts that arise curiosity (Table 9).

Table 8. Closing commentary introducing a symptom prescription (Schweitzer et al., 2020).

Table 9. Three-step approach of symptom prescription (Schweitzer et al., 2020).

Incisive negative beliefs represent mental models which have the power to entrap a person into a so-called problem trance. A problem trance is usually referred to as a trance state that arises when a client mentally enters a subject of high emotionality (Schlippe and Schweitzer, 2016). Such beliefs can be recognized by the following phenomena: (1) sentences in which one blames or accuses oneself, (2) sentences that are emotionally charged but not necessarily explicit, and (3) sentences with which one becomes discouraged, resigned, or fearful. With the choral speaking method (Schweitzer-Rothers, 2006), these sentences can be externalized and beliefs expressed in the sentences can be questioned. The stressful emotions are set in motion, become more and more flexible and distanced from the clients. The goal is to broaden both the clients’ thoughts and bodily sensations which co-carry these feelings, till new solution-oriented ideas emerge in kind of a “solution trance.” Choral speaking is easier the more people are present. The smaller the therapy system, the more the therapist must serve as both conductor and choir.

In line with the ISFT manual, the supervisor, six clients and their therapists met once during a therapy in a group session which lasted 3 h. The first part consisted of getting to know each other, with a special focus on the different goals that clients wanted to achieve within the therapy. The second part was essentially the choral speaking method, where clients’ belief systems are sung by the group until the clients begin to show altered reactions. (1) Clients write down their individual answers to the following questions on a flip chart: “What scares me?,” “Who is to blame?,” “What cannot I change?,” and “What would I have to do to make it worse?” (problem-trance). Likewise, the following questions are noted: “Where do I feel safe and in good hands?,” “With whom do I experience such moments?,” “What can I change?,” and “What can I do to make it more like I want it to be?” (solution-trance). (2) This is followed by an exchange in small groups of two or three clients and/or therapists. (3) Together with all clients and therapists, the sentences which have the strongest power to knock someone down as well as the sentences associated with intense positive emotions are identified. (4) Two large choruses are formed. The “problem choir” intones the most concise problem-trance sentences. The “solution choir” intones the most concise solution-trance sentences. The choirs each sing for one client. The client stands in front of the choir, with the supervisor as the conductor, and lets the sung sentences have an effect on him or her. (5) Problem-trance sentences are sung aloud or quiet, fast or slow, at least 10 times, with a short break between each repetition, until the client’s reaction changes. This can be anger at oneself (e.g., “Why do I torture myself so much!”), differentiating ideas (e.g., “That’s not always true!”), re-evaluations (e.g., “The second row gives much more freedom for self-care than the stressful positon of a front woman!”), or new posture ideas (e.g., laughter, or the song “The Bare Necessities” in remembrance of the Jungle Book). The new impulse is introduced into the chorus as a new phrase. The majority of the singers continue to sing the old phrase while a minority alternates singing the new phrase. In a singing contest, the conflicting movements compete against each other. In the listening client, new, third, fourth, fifth, etc. movements are often perceived. These reactions are integrated into the concert by their performance as new voices increasingly differentiating sub-systems of the choir. The process ends when the listening client feels the increase of (more) power and energy, or at least peace and calmness. (6) Solution-trance sentences are sung shorter. Their listening represents a ceremony. If they are botched, they lose their effect. When the listening client has recorded an inner soundtrack of the choral speaking, the choir ends. (7) A debriefing closes the choral speaking methods.

At the end of the ISFT, we and the client(s) reflect on the path we have travelled together in therapy. We congratulate the members of the affected social system on their progress and success. The focus is on the stabilization of the changes achieved. The goal is to make experiences from the therapy helpful for dealing with possible and expected “re-invitations” to future social anxieties in the sense of prolapse prevention. This includes exploring negative consequences of missing future rounds of honor in the old pattern: “What will be missing and become more stressful or conflictual if others experience you as less anxious in the future?.” This is often followed by a collection of good reasons for future prolapses: “What are benefits you associate with staying more or less socially anxious?”

We use timeline work (Suddaby and Landau, 1998) and allow for a glance into the future: “How and with whom do you (not) live, love and work in 3, 6, or 12 months?, What important things have (not) happened when and with whom?, Which challenges have (not) been mastered with whom and how?, Which challenges still have to be (not) overcome with whom and how?” Balances clarify (1) what has been changed, and which social system members contributed, (2) which change steps have (not yet) been performed, and (3) how life can continue even with the unchanged. The goal is that all social system members applaud themselves and the others for what has been achieved and give their blessing to be able to find peace with what currently could (not) be changed or will (not) be changed in the future. A shared farewell ritual serves as a transition to a life without therapy. A comeback is also possible. Even if we make a clear cut and do not extend therapies beyond what is refunded by the national health insurance, we remain open to meeting again after an appropriate therapy break based on success. The length of this break is negotiated with the affected social system. The comeback neither depends on the social system members being in a current crisis. It rather becomes possible with the presentation of a new concern which could not be well addressed in former therapy hours.

Following the studies of Willutzki et al. (2004), Rakowska (2011), and Leichsenring et al. (2009), we aimed to investigate the IFST for social anxiety disorder (SAD) considering its feasibility and trends of change in psychological, social system, and global functioning. This section will summarize the findings published in the original pilot RCT (Hunger et al., 2016a, 2020). The interested reader can find a detailed review of studies and evidence of psychotherapies for the treatment of SAD elsewhere (Hilzinger et al., 2016).

We used the well-established Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as a comparator (Clark and Wells, 1995; Stangier et al., 2016). Previous studies of systemic therapy for SAD have focused on individual therapies (Willutzki et al., 2004; Rakowska, 2011). The study by Leichsenring et al. (2009), the probably largest psychotherapy study on SAD, exclusively compared CBT with Psychodynamic Psychotherapy.

We conducted a prospective multicenter, assessor-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT; CBT: Center for Psychological Psychotherapy; ISFT: Institute of Medical Psychology; Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University: S-190/2014; registered with the U.S. National Library of Medicine, ClinicalTrials.gov: #NCT02360033).

According to Cocks and Torgerson (2013), we aimed to recruit a minimum of 32 patients for a powered two-arm pilot study. Considering a possible drop-out rate of 25%, we decided not to stop recruitment until 38 patients were enrolled and allocated. An independent allocator team performed block randomization to CBT or ISFT, and subsequently randomized patients to therapists (Efird, 2011). They then sent assignment information to the study director (CHS), who forwarded them to the staff members (Hunger et al., 2020).

We screened 252 interested persons, and of these, 38 patients were allocated to CBT and ISFT, respectively (CBT: 20 patients; ISFT: 18 patients). The patient flow can be found elsewhere (Hunger et al., 2020). Patients were almost equally men and women in their 30s with similar education levels, mainly married or living with a partner. Social system members were mainly married or living with a partner, well-educated and employed spouses or partners, parents, (best)friends, children, or siblings. Therapists were mostly educated females in their 30s, and the majority was married or living with a partner. Study arms were well-balanced with respect to patients’ data at baseline.

No therapist had practiced the CBT or ISFT manual before the trial started, so therapists all participated in three 3-day CBT or ISFT manual trainings. Subsequently, every therapist performed a training phase including the treatment of two patients. Experts in CBT and ISFT provided supervision every fourth therapy hour. Over the course of the study, CBT therapists’ global adherence showed smaller deviations (CTAS-SP: M = 2.18; SD = 0.29; 0 = no adherence, 3 = very good adherence; Consbruch et al., 2008). ST therapists’ global adherence was frequently demonstrated (STAS: M = 2.51; SD = 0.66; 0 = not at all, 3 = very often; Hilzinger et al., 2016; Hunger et al., 2020). In accordance with Borkovec and Nau (1972), we asked for the therapists’ allegiance to either CBT or ISFT (i.e., CBT: “How enthusiastic are you about CBT?”; ISFT: “How enthusiastic are you about ISFT?”; 1 = not at all, 5 = very much). Therapists’ allegiance did not differ between study arms (CBT: M = 3.95, SD = 0.59; ISFT: M = 4.10, SD = 0.38; t(31) = 0.868, p = 0.392).

The CBT manual (Clark and Wells, 1995; Stangier et al., 2016) works with the individual patient aiming at (re-) establishing a realistic self-perception in five therapy phases: (a) generation of an idiosyncratic version of the disorder and identification of safety behaviors; (b) manipulation of self-focused attention and safety behaviors, including role play and video feedback; (c) training in attentional redeployment and reduction in safety behaviors through behavioral experiments (expositions), cognitive restructuring and changing of dysfunctional convictions; (d) relapse prevention; and (e) refreshment and consolidation. Sessions were performed weekly and in the phase of relapse prevention every 2–3 weeks. Therapy sessions were mainly 50 min long, but with allowances to extend up to six sessions to a maximum of 100 min to facilitate behavioral experiments.

We will summarize the results of our pilot RCT in an overview, concentrating on the estimation of effects based on Cohen’s d for dimensional between- and within-group effects, and Cohen’s h for categorical between-group differences (Cohen, 1988). A detailed description of all instruments and results, including all test statistics and calculations, can be found in the original publication of the pilot RCT (Hunger et al., 2020).

Within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses of the patients’ ratings on the primary outcome showed a significant reduction in social anxiety (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, LSAS-SR; Rytwinski et al., 2009), with large effects seen in both conditions from baseline to end of therapy (CBT: d = 1.04; ISFT: d = 1.67). The intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA comparing CBT and ISFT showed a significant large effect to the advantage of ISFT (d = 0.81). Per-protocol analyses supported these results.

Considering the secondary outcomes, blind diagnosticians use the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID; Wittchen et al., 1997; First et al., 2016) and rated seven CBT patients (46.7%) and 14 ISFT patients (77.8%) as no longer demonstrating clinically relevant SAD symptoms at the end of therapy (χ2(1) = 3.422, p = 0.083; IRR at 94%, range: 91–100%). Within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses showed their ratings pointing to significant improvement in global functioning (GAF; Aas, 2010) in both conditions with large effects (CBT: d = 0.92; ISFT: d = 1.50; IRR at 94%, range: 82–100%). The intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA showed a significant medium effect to the advantage of ISFT (d = 0.76).

Within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses of the patients’ ratings on the secondary outcomes showed a significant improvement in psychological functioning on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Kühner et al., 2007) in both conditions (CBT: d = 0.50; ISFT: d = 1.71). The intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA showed a significant medium effect to the advantage of ISFT (d = 0.77). Significant improvement was also observed in within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses on the Global Severity Index (GSI) of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Geisheim et al., 2002) in the ISFT (d = 1.89), but not in the CBT. The intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA showed a significant medium effect to the advantage of ISFT (d = 0.77). Considering social system functioning, within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses of the Experience in Social Systems Questionnaire (EXIS.pers; Hunger et al., 2017) showed a significant improvement in both conditions (CBT: d = 0.23; ISFT: d = 1.06). The intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA was not significant.

Within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analysis of the social system members’ ratings on the secondary outcomes showed a significant reduction on the psychosocial Burden Assessment Scale (BAS; Hunger et al., 2016b) in both conditions (CBT: d = 0.56; ISFT: d = 0.59). The intention-to-treat mixed-design ANOVA was not significant. Significant improvement was also observed in within-group, simple-effect intention-to-treat analyses on the GSI in the ISFT (d = 0.14), but not in the CBT. Additional outcomes can be found elsewhere (Hunger et al., 2018, 2020).

Considering clinical significance, the level of patients’ remission (LSAS-SR) in CBT was 15%, response 55%, no change 25%, and deterioration 5%. For ISFT, the level of remission was 39% (h: 0.55), response 56% (h: 0.01), no change 1% (h: 0.57), and deterioration 0% (h: 0.45; Hunger et al., 2020).

We developed a manualized disorder-specific ISFT for SAD, evaluated for its feasibility in a multicenter, assessor-blind pilot RCT, and compared it to manualized and monitored CBT (Clark and Wells, 1995; Stangier et al., 2016). The discussion will concentrate on recommendations for the use of the ISFT manual in further studies, and for a confirmatory RCT to test the reported effects on psychological, social system and global functioning including both the patients and their social systems (e.g., family, couple; co-workers).

At the beginning of the ISFT project, the manual structure was designed strictly parallel to the number of hours and sequence of sessions of the CBT manual (Stangier et al., 2016), as this was the comparator. Initially, the therapy sessions followed each other closely, often weekly, and more sessions were agreed upon than proved useful and necessary. Therapists reported a feeling of “methodological pressure” from the manual: e.g., “I thought that I have to have my genogram interview ready after the second session as it is part of the initial phase. So, if I wanted to keep to the manual structure, I thought I had to hurry.” In the course of our pilot RCT, the ISFT therapists increasingly designed their own style of how to use the manual. They allowed themselves to omit manualized interventions, e.g., a third symptom prescription after two previous ones that had already been successful, when patients and therapists did not expect it to bring about further meaningful difference. At the end of the project, the ISFT dosage demonstrated a minor number of therapy hours compared to the manualized 25 h, and to the comparator in the per-protocol-analysis (CBT: M = 26.00 h, SD = 0.00, no range; ST: M = 22.50 h, SD = 2.57, range: 17–26; t(31) = 42.524, p = 0.000, d = 2.48). These findings support our stance toward the perception of the ISFT manual as an ideal suggestion from which there are good reasons to deviate in individual cases. As we already said in the ISFT introduction above, it seems optimal to us to take the ISFT manual sufficiently serious, but not too serious. This is why all interventions are interchangeable in their order, and why therapy planning in the ISFT can already start in the first therapy hour. It has not to wait till, all information have been collected at the end of the initial phase.

Therapists also reported that the ISFT manual had made it possible “for me to approach a lot of things more quickly.” The use of the initial phone contact (Prior, 2010) allowed the therapists to work solution-oriented already before an encounter with the clients. It turned out to be an enculturation into the ISFT. Clients no longer came to the therapy with the expectation of having to present as many problems as possible in order to get access to treatment (“ticket to admission”; Goldberg and Bridges, 1988). In none of the ISFT patient-therapist-dyades did we perceive the “culture clash” often described in the practice of systemic therapy. This becomes evident when patients believe that they must communicate problems while therapists strive for solutions. This phenomenon also includes social system members when present during the ISFT.

The Social Network Diagnostics (Hunger et al., 2019) was mentioned by the clients, diagnosticians, therapists and researchers to be very useful for the detection of social system members, e.g., partners, family members, and other important caregivers. Both diagnosticians and therapists described the conductance of the Social Network Diagnostics on par with the SCID interview and highly supportive to include significant others in the therapy process either as significant relative or friend, and/or additional client with clinical problems. Therapists also reported that the Social Network Diagnostics made it easier for them to address and negotiate changes of social relationships which is at least as important as changes of SAD symptoms detected with the SCID.

Therapists also took methodological suggestions from the ISFT manual. This was most often the idea in case of the symptom prescription. Due to the historical closeness of the Heidelberg School (Stierlin, 1976) to the Milan approach (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1975), we ascribed a great importance to this classical and nowadays still innovative systemic method. The therapists particularly liked our adaption of the Milan approach into a three-step approach by prescribing problems, solutions, and avoidances either in vivo or in sensu. The current German landscape of systemic therapy appears to incorporate a pronounced solution-orientation. As a result, the symptom prescription with its directive nature is rarely and less explicitly trained. In the ISFT, solution prescriptions invited therapists and patients to make a first encounter with the symptom prescription. As a result, a curiosity arose on the part of both therapists and patients to try out problem prescriptions as well. Avoidance prescriptions were experienced as particularly tricky. They often highlighted the price patients paid to protect themselves from negative criticism, making it impossible, for example, to experience any positive feedback simultaneously.

The obligation to conduct multi-person conversations at least once in each therapy phase encouraged the therapists to conduct settings with more than one representative of the affected social system. Additionally, the choral speaking was new to therapists and patients and became one of the core interventions to stimulate meaningful change from the patients’ and therapist’ viewpoint (Hilzinger et al., 2021).

A larger budget for the recruitment of patients is needed in future RCTs. We screened 252 individuals, and of these, 189 were heard on initial screening phone calls, each lasting about 20–30 min. SCID interviews were performed with 101 individuals lasting about 60–90 min. This costly procedure was required to finally include 38 patients in the pilot RCT. Though the drop-out rate was zero for the ISFT, it was at 25% for the CBT. The budget for recruitment for this pilot RCT was inadequate and comprised the timeliness of the study as well as the more advanced investigation of therapists’ adherence and competence which is crucial for the sophisticated interpretation of study results.

There are often difficulties reported with respect to the inclusion of social system members in psychotherapy research. In our pilot RCT, however, this was not the fact but rather an easy game. Based on our experiences from our pilot RCT, we recommend the early application of the Social Network Diagnostics (Hunger et al., 2019) as it allows for the identification of those social system members who appear to play an important role in the development, maintenance and change of the addressed symptoms.

It was difficult to recruit therapists with substantial experience in multi-person settings. Although it is seen that the work with families, couples and social networks is at the core of systemic therapy, it is evident that currently multi-person settings are hardly trained in German psychotherapy. Therefore, future studies should give a special focus in the ISFT manual training and supervision of therapies like we implemented in our pilot RCT.

The insufficient funding for recruitment procedures equally applies to the budget for blind diagnosticians. Currently, the hourly rate for external psychological diagnosticians is about 100€, if they are not permanently employed due to a lack of funding. We saw about 100 interested persons in 60–90 min SCID interviews. Again, the funding was insufficient and should be better supported by appropriate structural working conditions. so that diagnosticians can be hired for the study period.

The randomization was appropriate and the independent allocator team worked well performing block randomization (Schulz and Grimes, 2007) using a pseudorandom number generator (www.randomization.com; McLeod, 1985). Patients, social system members, and therapists knew which study-arm they were being allocated to, though not about the specific research questions. We do not see this as a disadvantage of our pilot RCT as transparency is a fact of “real word delivery of care” (Zwarenstein et al., 2008, p. 6).

CBT as an active comparator worked well in our pilot RCT. It, however, showed a 25% drop-out after the initial clinical interview. The reasons for this were the demand for a stronger integration of the partner and/or family into therapy, the experience of therapy demanding too much or the detection of another primary diagnosis compared to SAD.

Furthermore, essential characteristics of systemic therapy were abandoned in favor of comparability between the ISFT and CBT as the active comparator. Systemic therapy grounds in a collective intervention culture that meets with the affected social system in multi-person settings approximately every 3–4 weeks (Schweitzer, 2014). CBT, however, belongs to individual intervention cultures and sees mostly one single patient each week. The preconditions thus were uneven to the disadvantage of the ISFT. Future studies should investigate whether differences may appear less between different schools of psychotherapy than in the nature of the performed setting. It can be assumed that by treating an entire social system, the relapse rate of individual members with previously diagnosed mental disorders appear reduced (Morgan et al., 2013). This may be due to a better balance of interpersonal in addition to intrapersonal conflicts, the recognition and multidirectional negotiation of differences in each social system members’ need for related autonomy (Stierlin, 1976) and increased options for the evolvement of an integrated prosocial support within the affected social system (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

The reported instruments are validated, easy to administer and impactful measures that serve well as primary and secondary outcomes for ISFT in SAD. This is even more successful as the primary outcome of ISFT is not a symptom reduction but an improvement of social system functioning. The primary effect of ISFT, assessed with the LSAS as an instrument asking for social anxiety symptoms, was therefore measured with an instrument that is less close to the actual intent and mode of action of the ISFT. Future studies should concentrate on a broader acquisition of the social system functioning, considering its different facets.

Online data collection worked well in kind of a “Data Café,” accompanied by cakes, cookies and/or coffee, which we implemented in a comfortable room for both study arms. Study staff was always available to answer questions. Since there was no fundamental criticism against the online assessment via the online platform UNIPARK, we recommend online data collection in future studies for economic reasons with respect to the study management, and to ensure no missing or potential data entry errors in the assessment procedure.

The statistical results need interpretation with caution, since the nature of a pilot trial is its small sample size that is not sufficiently powered to test hypotheses of program efficacy. Our pilot trial, however, used an adequate power for a two-arm pilot RCT based on the rationale of Cocks and Torgerson (2013). The trend obtained in the LSAS as the primary outcome for psychological functioning was positive and encouraging. Results also indicated significant treatment effects on additional aspects of psychological and social system functioning to the advantage of the ISFT, including blind diagnosticians’ ratings of patients’ remission from SAD as well as their global functioning. Social system members likewise reported a reduction in their psychosocial burden, and improvement of psychological functioning. This finding fits well into the socio-psycho-biological explanatory model (Figure 1; Luhmann, 2017; Hunger et al., 2018): changes in one person are reciprocally associated with changes in the other person (“spill-over effect”; Keeton et al., 2013), pointing to mental disorders as interpersonally shared realities and the need to include all important social system members in psychotherapy to empower sustainable change (Morgan and Crane, 2010). The overall positive trends of the ISFT compared to CBT in our study bode well for a larger powered RCT.

Our manualized disorder-specific new ISFT for SAD was evaluated for its feasibility in a multicenter, assessor-blind pilot RCT, compared to manualized and monitored CBT. Both the creation of the manual, its acceptability by therapists, patients, and social system members, as well as the efficacy trends calculated for the ISFT bode well for a subsequent confirmatory RCT. The pilot findings indicated integrity of the study methods and procedures, a favorable acceptance of the manual by therapists, patients, and social system members. We however suggest minor adjustments to recruitment, instruments, test administration, and a stronger emphasis on the flexibility of the ISFT manual. The promising results indicate a fully powered RCT concentrating on the social system functioning, in addition to the assessment of patients’ symptomatology, to be feasible and worth of future investment of time, effort, and funding.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because raw data cannot be anonymized. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to CHS, Y2hyaXN0aW5hLmh1bmdlci1zY2hvcHBlQHVuaS13aC5kZQ==.

The RCT involved human participants. It was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty (S-190/2014). The patients provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

CHS, JS, and RH conceptualized and designed the RCT. CHS, LK, LD, RH, JM, and AS contributed substantially to the data analysis, and together with JS and HB contributed to the interpretation of the study results. JS drafted the first German version of the ISFT manual, complemented and revised by CHS, RH and HL. CHS drafted the English version of the ISFT manual. JS is first author of the original ISFT manual, and CHS is first author of the original publication of our pilot RCT. All authors critically reviewed this publication for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This project was the winner of the 2014 research competition of the German Association for Systemic Therapy, Counseling and Family Therapy (DGSF). It gained further financial support from the Systemic Society (SG), the Heidehof Foundation, the Institute of Medical Psychology at the University Hospital Heidelberg, and the Center for Psychological Psychotherapy at the Heidelberg University.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aas, M. (2010). Global assessment of functioning (GAF): properties and frontier of current knowledge. Ann. General Psychiatry 9:20. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-9-20

Andersen, T. (1991). The Reflecting Team: Dialogues and Dialogues About the Dialogues. New York, NY: Norton & Co

Bateson, G. (2000). Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Borkovec, T. D., and Nau, S. D. (1972). Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 3, 257–260.

Boszormenyi-Nagy, I., and Sparks, G. M. (1973). Invisible Loyalties: Reciprocity in Intergenerational Family Therapy. New York, NY: Harper & Row

Braus, N., Kewitz, S., and Hunger-Schoppe, C. (2022). The complex dynamics of resources and maintaining factors in social networks for alcohol-use disorders: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 13:804567. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.804567

Cecchin, G. (1987). Hypothesizing, circularity, and neutrality revisited: an invitation to curiosity. Fam. Process 26, 405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1987.00405.x

Clark, D. M., and Wells, A. (1995). “A cognitive model of social phobia,” in Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. eds. R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, and F. R. Schneier (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 69–93.

Cocks, K., and Torgerson, D. J. (2013). Sample size calculations for pilot randomized trials: a confidence interval approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 66, 197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.002

Consbruch, V., Heinrich, K., Engelhardt, K., Clark, K., and Stangier, D. M. U. (2008). “Psychometric properties of the german versions of the cognitive therapy competence scale for social phobia (CTCS-SP) and the cognitive therapy adherence scale for social phobia (CTAS-SP),” in SOPHONET Forschungsverbund zur Psychotherapie der Sozialen Phobie. eds. E. Leibing, S. Salzer, and F. Leichsenring (Göttingen: Cuvillier Verlag), 14–21.

Eaker, E. D., Sullivan, L. M., Kelly-Hayes, M., D’Agostino, R. B., Sr., and Benjamin, E. J. (2007). Marital status, marital strain, and risk of coronary heart disease or total mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Psychosom. Med. 69, 509–513. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f62357

Efird, J. (2011). Blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 15–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8010015

Emlein, G. (2010). Luhmann, Niklas: Soziale Systeme - Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie. Familiendynamik 35, 168–172.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., and Spitzer, R. L. (2016). User’s guide for the SCID-5-CV Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® Disorders: Clinical Version. Arlington, VA: APA

Geisheim, C., Hahlweg, K., Fiegenbaum, W., Frank, M., Schröder, B., and Witzleben, I. V. (2002). Das Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) als Instrument zur Qualitätssicherung in der Psychotherapie. Diagnostica 48, 28–36. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.48.1.28

Goldberg, D. P., and Bridges, K. (1988). Somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in primary care setting. J. Psychosom. Res. 32, 137–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(88)90048-7

Hammel, S. (2011). Handbuch der Therapeutischen Utilisation. Vom Nutzen des Unnützen in Psychotherapie, Kinder- und Familientherapie, Heilkunde und Beratung. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta

Hand, I. (2002). “Systemische Aspekte in der Verhaltenstherapie von Zwangsstörungen,” in Die Behandlung von Zwängen. Perspektiven für die klinische Praxis. ed. W. Ecker (Bern: Huber), 81–100.

Hilzinger, R., Duarte, J., Hench, B., Hunger-Schoppe, C., Schweitzer, J., Krause, M., et al. (2021). Recognizing oneself in the encounter with others: meaningful moments in systemic therapy for social anxiety disorder in the eyes of patients and their therapists after the end of therapy. PLoS One 16, e0250094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250094

Hilzinger, R., Schweitzer, J., and Hunger, C. (2016). How do I evalute whether it was systemic? An overview of systemic adherence scales examplified by psychotherapeutic efficacy studies on social anxiety. Familiendynamik 43, 2–11. doi: 10.21706/fd-41-4-334

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., and Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hunger, C., Bornhäuser, A., Link, L., Geigges, J., Voss, A., Weinhold, J., et al. (2017). The experience in personal social systems questionnaire (EXIS.Pers): development and psychometric properties. Fam. Process 56, 154–170. doi: 10.1111/famp.12205

Hunger, C., Geigges, J., and Schweitzer, J. (2019). “Social network diagnostics (SozNet-D): assessment and practice including structural and functional aspects of social relations,” in Systemic Methods in Family Counselingand Therapy. eds. A. Eickhorst and A. Röhrbein (Göttingen: V&R), 269–280.

Hunger, C., Hilzinger, R., Bergmann, N. L., Mander, J., Bents, H., Ditzen, B., et al. (2018). Burden of significant others of adult patients with social anxiety disorder. Psychotherapeut 63, 204–212. doi: 10.1007/s00278-018-0281-5

Hunger, C., Hilzinger, R., Klewinghaus, L., Deusser, L., Sander, A., Mander, J., et al. (2020). Comparing cognitive behavioral therapy and systemic therapy for social anxiety disorder: randomized controlled pilot trial (SOPHO-CBT/ST). Fam. Process 59, 1389–1406. doi: 10.1111/famp.12492

Hunger, C., Hilzinger, R., Koch, T., Mander, J., Sander, A., Bents, H., et al. (2016a). Comparing systemic therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorders: study protocol for a randomized controlled pilot trial. Trials 17, 171. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1252-1