- 1School of Business, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University Islamabad, Sahiwal, Pakistan

- 3Department of Business Administration, National College of Business Administration and Economics (NCBA&E), Multan, Pakistan

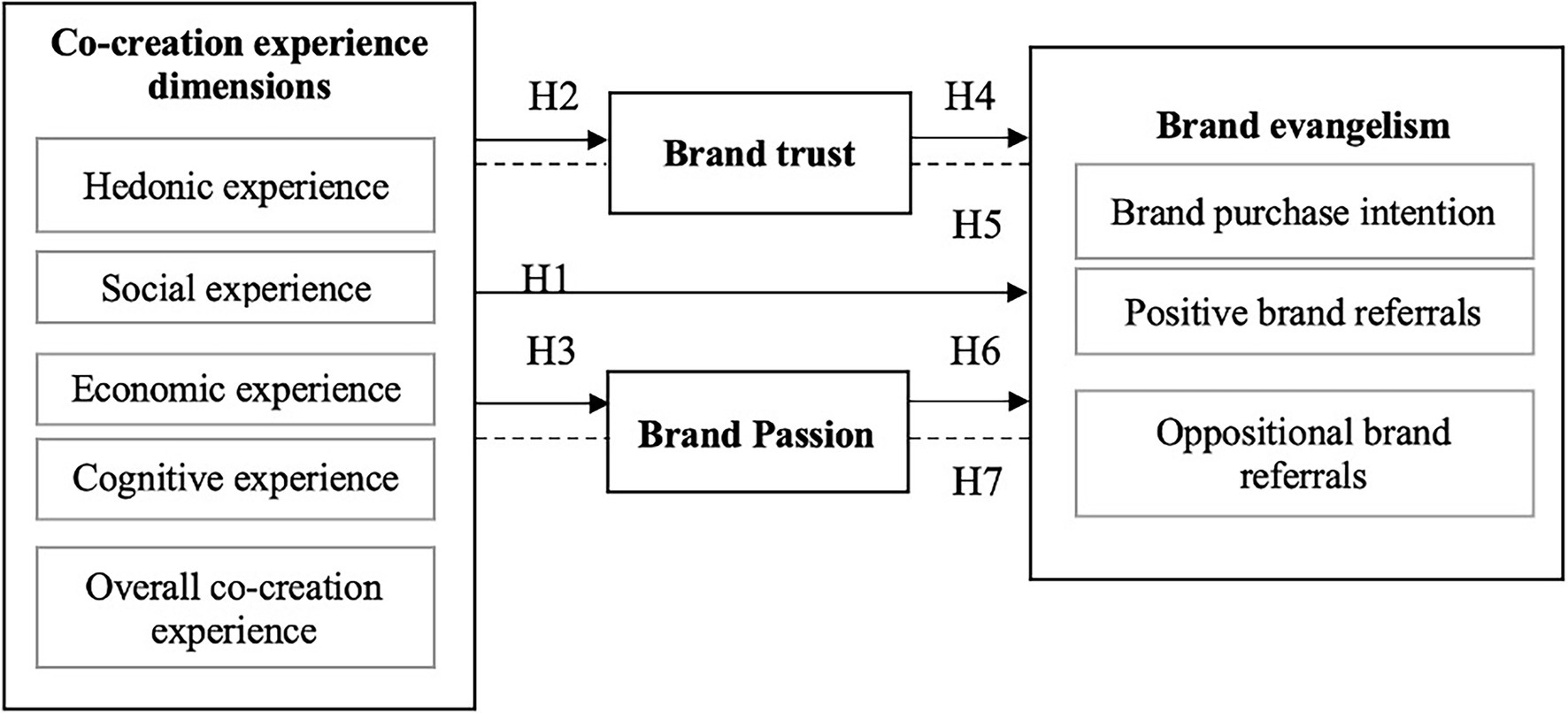

Drawing on the theory of engagement, the present study aims to examine the outcomes of the co-creation experience in a realistic co-creation setting, a hotpot restaurant. To this end, the current research links the relationship marketing literature to hospitality and tourism research and formulates a novel framework by incorporating tourists’ co-creation experience, brand evangelism, brand trust, and brand passion in an integrated conceptual model. Using a quantitative research design, a total of 453 international tourists were surveyed in China. The findings revealed that co-creation experience dimensions positively impact brand evangelism, trust, and passion. Additionally, we found that brand trust and brand passion positively affect brand evangelism. We also confirmed the mediating effect of brand trust and brand passion in bridging the co-creation experience and brand evangelism. This study offers valuable insights for restaurant brand managers regarding attracting and engaging foreign travelers with their service businesses.

Introduction

China has emerged as a top destination for global tourists since the Open Door Policy was enacted in 1978. The period from 2001 to 2019 witnessed an incredible increase in the number of visitors, which rose from 89.1 to 145 million, accounting for an overall growth rate of about 63% (Statista, 2021). Tourists travel for different motives, but visiting local restaurants constitutes an integral part of their stay (Hussain et al., 2018). According to Liu and Jang (2009), Chinese cuisines are exceedingly favored among tourists owing to their high diversification and unique taste. This popularity has led to intense competition among restaurants brands; however, they face many challenges in engaging tourists with their brand, leading to an uncertain future. Their primary objective has been to generate profit rather than understand customers’ needs and expectations and offer value to them. The old-fashioned good-centered dominant logic in which customers are passive receivers of value has shown its inefficacy in retaining customers and engaging them long-term. Accordingly, the customers’ role has shifted from passive receivers of value to co-creators of values alongside the organization (Vargo and Lusch, 2004); therefore, restaurant brands should consider tourists as part of stakeholders and involve them in the value co-creation activity.

Since conception, value co-creation has become a very influential concept, as practitioners and scholars have increased their interest in service-dominant logic (Vargo and Lusch, 2004). Service-dominant logic implies that customers are always co-creators of value. Customers involved in value co-creation feel less deprived and more fulfilled (Navarro et al., 2015). Therefore, co-creation experience (CCE) has received substantial research attention in tourism marketing (Verhoef et al., 2010; Shaw et al., 2011), as an increasing number of firms involve customers in the co-creation process (Jaakkola et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). CCE is defined as the benefits customers expect from the co-creation activity (Verleye, 2015). Extant literature has linked CCE with customer satisfaction (Alarcón López et al., 2017; Hussain et al., 2020), purchase intention (Blasco-Arcas et al., 2014), customer loyalty (Mathis et al., 2016), revisit intention (Hurriyati and Sofwan, 2015; Meng and Cui, 2020) and memorability (Campos et al., 2016; Rachão et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, CCE is limited in three important perspectives. First, while scholars have investigated CCE in the hospitality and tourism context (i.e., Tu et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2018), research on the effect of CCE on tourists’ dining experience remains scarce. Grönroos (2011) revealed that cooking a meal at a restaurant is a comprehensive example of the value co-creation process. Additionally, recent research has confirmed that the restaurant industry provides a platform to investigate customer experience in a co-creation setting (Hussain et al., 2019, 2020). For instance, restaurants, such as McDonald’s and Inamo, offer customers the opportunity to co-create by selecting food through a touchscreen. Chinese hotpot restaurants offer customers a complete CCE by involving them in the cooking process (Hussain et al., 2020). Second, although researchers have acknowledged the importance of CCE, empirical work on its outcomes is still limited (Verleye, 2015). Scholars have primarily paid attention to the antecedent of CCE (e.g., Cova et al., 2011). Third, the economic (e.g., sales growth) and customer benefits of CCE (e.g., customer retention and customer acquisition) are poorly known. An in-depth analysis of CCE literature reveals a scarcity of research investigating the CCE-economic and customer benefit link. The purpose of the current study is to address these mentioned gaps in the literature of CCE. Therefore, the ultimate question is: What is the substantial return on marketing investment outcomes for firms promoting the CCE in the hospitality context?

We propose that brand evangelism (BE), a high level of positive word-of-mouth communication, is a possible outcome for firms. Matzler et al. (2007) defined BE as a more active and committed way of spreading positive opinions and trying fervently to convince or persuade others to get engaged with the same brand. According to Doss (2014), the “evangelist” is an unpaid brand representative who evangelizes others on behalf of the brand. Samson (2006) stated that customer responses to evangelism are more substantial and effective than word-of-mouth, which is the outcome of positive consumer involvement. Although anecdotal proof affirms the importance of CCE, the influence of CCE on BE is largely unresearched.

Consumer–brand relationships have attracted considerable attention among scholars and brand managers as they can influence consumer behavior and marketplace advantages for firms (Albert and Merunka, 2013; Fetscherin and Heinrich, 2015). However, researchers have overlooked the relationship between CCE and consumer–brand relationships, including brand trust (BT) and brand passion (BP). According to Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), BT refers to the willingness of the average consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to provide its stated function. Consumers’ trust in brands is valuable to brands in both online and offline markets (Becerra and Korgaonkar, 2011). As a driving force for consumer–brand relationship, Sternberg (1986) explained that passion is a “hot” element, resulting in romance, physical attraction, adoration, and idealization of a significant other. According to Bauer et al. (2007), the growing relevance of passionate brands in marketing requires examining BP determinants. Based on the theory of engagement, The present study investigates the effect of international tourists’ CCE on BT, BP, and BE in a realistic and routinely performed co-creation setting, a hotpot restaurant.

The current research makes several contributions to the fields of branding, hospitality, and tourism, primarily through the discussion of two critical concepts: the CCE of customers and BE. Mathis et al. (2016) emphasized that CCE can influence brand outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to offer an integrated model of CCE by investigating its effect on BE in the hospitality and tourism context. It identifies how CCE enhances BT and BP and stimulates BE. Hussain et al. (2020) explained that CCE benefits both customers and restaurant brands.

study provides a framework for restaurant brand managers regarding optimizing their service and enhancing their business through the retention and acquisition of valuable customers.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Co-creation Experience

The value co-creation process comprises various actors, including the beneficiary, who decides the value, while other actors contribute to developing and presenting value proposals (Vargo and Lusch, 2004). Ahn et al. (2019) outlined value co-creation behavior as consumers cooperating with other actors to engage in a series of important value-creation activities. In contrast, CCE refers to the mental state resulting from the customers’ participation in the value co-creation activity (Chen, 2018).

Several scholars have examined the concept of co-creation in the tourism (Hurriyati and Sofwan, 2015; Rachão et al., 2019; Mohammadi et al., 2020) and hospitality sectors (Kallmuenzer et al., 2019; Gibbs et al., 2021), as co-creation complements tourism while providing tourists with the opportunity to participate in services. Ramaswamy and Ozcan (2018) posited that co-creation facilitates interactional creation across interactive system environments (afforded by interactive platforms), entailing agency engagements and structuring organizations. According to Jaakkola et al. (2015), CCE is multidimensional as both a phenomenon and a concept. Merz et al. (2018) highlighted its multidimensional nature using two higher-order factors: customer-owned resources and customer motivation. Verleye (2015) highlighted four dimensions of CCE, namely, hedonic experience (HE), cognitive experience (CoE), social experience (SE), and economic experience (EE).

According to Zhang et al. (2020), hedonic reaction is the positive emotional state resulting in customer satisfaction; HE is seen as the pleasurable experience customers expect from the CCE. Customers participating in the value co-creation process seek fun, pleasure, and entertainment regardless of extrinsic rewards (Chen, 2018). CoE is knowledge about service, products, and technologies that customers expect to gain from a co-creation activity (Verleye, 2015). It helps customers to explore news ways to use products and learn from other participants’ co-creation efforts. Füller (2010) stated that customers seeking CoE are intrinsically motived and stimulated by their desire to generate and implement creative ideas for their own sake. At Chinese hotpot restaurants, participation in value co-creation offers customers the opportunity to keep pace with new ideas and hone their skills and ability to perform a specified task. SE is the benefit of connecting with like-minded people during the co-creation activity. Customers expect to gain better status and social esteem from their value co-creation process. According to Füller (2010), this experience builds on the desire of an individual for social identity, recognition, and development of skills that improve communication with the outside world. While some customers participate in the co-creation activity to hone their skills and meet like-minded people, others expect pragmatic and economic benefits. EE refers to the reduction of risks associated with receiving inappropriate products or services and the compensation in line with the effort made (Verleye, 2015). Verleye (2015) found that all four dimensions positively impact the overall co-creation experience (OCCE).

The scale developed by Verleye (2015) presents higher construct validity, reliability, and internal consistency. She stressed that further research should validate the scale in different co-creation situations; therefore, we utilized the exact dimensions to investigate the relationship between CCE, BT, BP, and BE in a restaurant setting. Recent studies have endorsed Verleye’s dimensions (e.g., Hussain et al., 2020).

Brand Evangelism

Organizations face several challenges because of a highly connected marketplace; they are keen to focus on the smaller but most influential customer category known as brand evangelists (Marticotte et al., 2016). The reason for this focus is their potential ability to actively disseminate brand-related experiences among others, embrace a particular brand intensively, persuade others to experience the brand, and dissuade others from buying rival brands (McConnell and Huba, 2003). Many studies argue that positive word-of-mouth or assertive support behavior, such as brand advocacy and brand defense, is derived from the consumer–brand relationship (Hsu, 2018). Mishra et al. (2021) found that customer–brand relational constructs, including brand trust, brand affect, and brand identification, strongly impact BE in terms of purchase intention and brand referral behavior. Harrigan et al. (2020) highlighted that value co-creation leads to brand advocacy and brand defense, which are intrinsically related to BE.

Sharma et al. (2021) outlined that brand community engagement is related to BE, and BE mediates the relationship between brand community engagement, brand defense, and brand resilience. Matzler et al. (2007) argued that a focus on word-of-mouth communication alone does not reveal customers’ behavior and their power to convince others about the brands they like; therefore, BE has emerged as an important concept in the consumer–brand relationship literature. Samson (2006) posited that BE generates a greater and more effective customer response than word-of-mouth. BE has facilitated small brands and benefited large organizations, including Southwest Airlines, IBM, and Build-A-Bear Workshop (McConnell and Huba, 2003).

According to Badrinarayanan and Becerra (2013), BE is customers’ behavioral support for a particular brand, including purchasing a specific brand, convincing others about it, and recommending it to others. Our study adopted the multidimensional approach of BE developed by Badrinarayanan and Becerra (2013). They found that BE is based on three dimensions: brand purchase intention (BPI), positive brand referrals (PBR), and oppositional brand referrals (OBR). Fishbein et al. (1977) defined BPI as a subjective inclination toward a brand or product. Therefore, it is a measure of the strength of consumer intention to decide to purchase a brand in the future (Yeo et al., 2020). Brand evangelists, considered active supporters of a brand, show behavioral support by purchasing products of that brand. PBR can be defined as the brand evangelists’ active behavioral support for a brand, which they show by disseminating favorable opinions, recommending it to others, and attempting to convince others to engage with the same brand. OBR is a negative attitude toward competing brands, resulting from attachment and loyalty to a brand. The strategies employed by brand evangelists go beyond purchasing the brand to include denigrating rival brands that present a threat (Doss, 2014). According to Badrinarayanan and Becerra (2013), research on the antecedents of BE is still limited, so there is a need to broaden the scope for a better understanding of what leads to evangelistic behaviors.

Brand Trust

BT plays a vital role in relational exchange (Riorini and Widayat, 2015; Ling et al., 2021). According to Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), the foundation of BT relies on the brand’s ability to perform its stated function; therefore, the reliability of a brand is the root of BT (Ballester and Munuera-Alemán, 2005; Villagra et al., 2021). Trust has become a very influential concept in branding (Husain et al., 2022). Morgan and Hunt (1994) stated that trust exists when the concerned parties have confidence in each other’s integrity and reliability. In the tourism and hospitality sector, Kim et al. (2014) suggested that a well-renowned celebrity is seen as reliable and can be influential in attracting customers’ attention and highlighting a positive image for hotels.

BT has strong positive relations with brand love (Albert and Valette-Florence, 2010) and BP (Gilal et al., 2020). Fehr and Anne (1988) stated that trust relates to affection more than passion in terms of interpersonal relations. However, similar to passion, BT encompasses both cognitive and affective dimensions (Ling et al., 2021). Baumann and Le Meunier-FitzHugh (2013) reported that trust among parties emerges from internally guaranteed certainty, which leads to brand value co-creation and ensures the other party will not act opportunistically. Their study further highlighted that consumers’ BT is a core element that makes consumers brand evangelists.

Several scholars have investigated the relationship between customer experience and BT (Ha and Perks, 2005; Walter et al., 2013; Guan et al., 2021); however, they have largely overlooked the relationship between CCE and BT even though both concepts are fundamental in measuring consumer behavior.

Brand Passion

Many scholars have investigated the concept of passion in marketing. Bauer et al. (2007) stated that brand uniqueness is one of the principal drivers of consumers’ BP from a theoretical perspective. According to Matzler et al. (2007), individual factors, such as consumer personality, influence BP. Their findings contradicted those of Bauer et al. (2007), who found that the extroversion trait in consumer personality is highly effective for fostering BP.

Gilal et al. (2018) stressed that passion plays a crucial role in shaping positive word-of-mouth communications. Moreover, passion improves consumers’ desire to pay for a premium brand (Swimberghe et al., 2014; Gilal et al., 2018), consumer brand loyalty (Hemsley-Brown et al., 2016), brand advocacy, brand community engagement, social media support, and purchase intention (Pourazad and Pare, 2015; Mukherjee, 2020). Keh et al. (2007) posited that BP represents the zeal and enthusiasm features of the consumer–brand relationship. Matzler et al. (2007) concluded that when consumers are passionate about a brand, they develop a deep emotional relationship with it and may miss it or feel lost if the brand is unavailable. Therefore, BP is intrinsically related to consumer behavior (D'lima, 2018; Gilal et al., 2021a). Thomson et al. (2005) highlighted that BP emerges from an intense and aroused positive feeling toward a brand. Similar to BT, the literature has overlooked the relationship between CCE and BP. Therefore, this study attempts to address this gap in the literature.

Hypotheses Development and Theoretical Framework

Customers’ Co-creation Experience and Brand Evangelism

The constructs of CCE and participation in value co-creation are intrinsically related. CCE is derived from the experience (or benefits) that customers gain from participating in the value co-creation activity.

In the value co-creation process, values are co-created by customers, for customers through experiencing the service and sharing them with others in the user community. Harrigan et al. (2020) outlined that value co-creation is positively related to BE, and Javed et al. (2015) posited that customers are more likely to spread positive opinions and defend what they helped create. Seifert and Kwon (2019) stated that co-creation efforts generate customer recommendations. They further posited that Yi and Gong (2013) use the term customer citizenship behavior to describe evangelistic behaviors, which, according to Badrinarayanan and Becerra (2013), comprise BPI, PBR, and OBR.

According to the theory of engagement, a positive customer experience with a brand leads to customer engagement, which comprises direct contributions (brand purchase) and indirect contributions (incentivized referrals and social media conservations; Pansari and Kumar, 2017). Navarro et al. (2015) stressed that customers involved in value co-creation feel less deprived and more fulfilled. Accordingly, customers participating in the value co-creation process are more likely to have a good experience with the firm, which will eventually stimulate brand purchase intention and positive word-of-mouth messages. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H1: CCE dimensions of (a) hedonic, (b) cognitive, (c) social, (d) economic, and (e) overall co-creation experience positively influence BE dimensions of brand purchase intention, positive brand referrals, and oppositional brand referrals.

Customers’ Co-creation Experience and Brand Trust

CCE is the customer experience resulting from the co-creation activity. Guan et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between customer experience and BT and found that experience is related to trust, which is consistent with the findings of Ha and Perks (2005) and Walter et al. (2013). Kamboj et al. (2018) found that customer participation, which is related to CCE, positively impacts BT.

Several scholars have examined the relationship between BT and customer satisfaction. They found that BT and customer satisfaction are positively related (Liao et al., 2011; Umar and Bahrun, 2017; Diputra and Yasa, 2021). In their theory of engagement, Pansari and Kumar (2017) posited that a positive/negative customer experience affects the level of satisfaction. Hussain et al. (2020) found that CCE impacts customer satisfaction. Based on the above discussion, we hypothesize that:

H2: CCE dimensions of (a) hedonic, (b) cognitive, (c) social, (d) economic, and (e) overall co-creation experience positively influence BT.

Customers’ Co-creation Experience and Brand Passion

In an increasingly competitive and connected marketplace wherein firms fulfill customers’ needs and expectations, marketing scholars and practitioners have stressed that building a highly emotional consumer–brand relationship is vital in consumer marketing (Huber et al., 2015). Scholars have found that passion and emotion are intrinsically related. According to D'lima (2018), emotion is a dimension of brand passion; therefore, passion is a strong or intense emotion. Bauer et al. (2007) stated that BP is the emotional attachment to a brand and Matzler et al. (2007) posited that passion engages emotional relationships.

According to Hussain et al. (2020), CCE is related to emotional brand attachment. Moreover, Pansari and Kumar (2017) posited that a positive/negative customer experience affects the level of emotions customers have for a firm (Theory of engagement). Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H3: CCE dimensions of (a) hedonic, (b) cognitive, (c) social, (d) economic, and (e) overall co-creation experience positively influence BP.

Brand Trust and Brand Evangelism

BE is considered a high-level of word-of-mouth communication. Previous research found that BT is related to service outcomes, such as word-of-mouth communication (Wang et al., 2018) and purchase intention (Chae et al., 2020). Additionally. Scholars have investigated the relationship between BT and BE, finding that trust positively stimulates evangelistic behaviors (Badrinarayanan and Becerra, 2013; Doss, 2014; Riorini and Widayat, 2015). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H4: BT positively influences BE dimensions of brand purchase intention, positive brand referrals, and oppositional brand referrals.

While it is customary to refer to customers as “the audience,” implying a more passive role, Oetting and Jacob (2007) posited that firms should involve customers in the co-creation process by offering them a more active role. BT is achieved through mutual experience and activities and is an important construct for a successful relationship between firms and customers.

According to Pansari and Kumar's (2017) theory of engagement, customer experience can lead to customer satisfaction which, in turn, leads to customer engagement. They posited that customer engagement comprises direct contributions (brand purchase) and indirect contributions (incentivized referrals and social media conservations). Badrinarayanan and Becerra (2013) outlined that BE dimensions comprise brand purchase (i.e., BPI) and referrals (i.e., PBR and OBR). Walter et al. (2013) found that customer experience is related to BT, and Diputra and Yasa (2021) found that BT impacts customer satisfaction.

Based on the above discussion, we posit that CCE leads to BT, which in turn, leads to brand evangelistic behavior. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H5: BT mediates the relationship between the CCE dimensions of (a) hedonic, (b) cognitive, (c) social, (d) economic, and (e) overall co-creation experience, and BE dimensions of brand purchase intention, positive brand referrals, and oppositional brand referrals.

Brand Passion and Brand Evangelism

Marketing scholars have highlighted that BP has certain causes and leads to certain outcomes, both of which contribute to understanding consumer behavior (D'lima, 2018). Bauer et al. (2007) showed that BP has a positive impact on BPI and positive word-of-mouth. Gilal et al. (2021b) found that BP influences purchase intention, and Ghorbanzadeh et al. (2020) found that BP is related to positive word-of-mouth intention. Matzler et al. (2007) found that BP leads to BE. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H6: BP positively influences BE dimensions of brand purchase intention, positive brand referrals, and oppositional brand referrals.

According to Bauer et al. (2007), BP is the emotional attachment to a brand. Pansari and Kumar (2017) posited that customer experience is likely to lead to emotions which in turn leads to customer engagement. They further asserted that customers showing positive emotions would assist firms with behaviors, such as brand advocacy. Pourazad et al. (2019) found that BP is related to brand advocacy. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H7: BP mediates the relationship between CCE dimensions of (a) hedonic, (b) cognitive, (c) social, (d) economic, and (e) overall co-creation experience, and BE dimensions of brand purchase intention, positive brand referrals, and oppositional brand referrals (Figure 1).

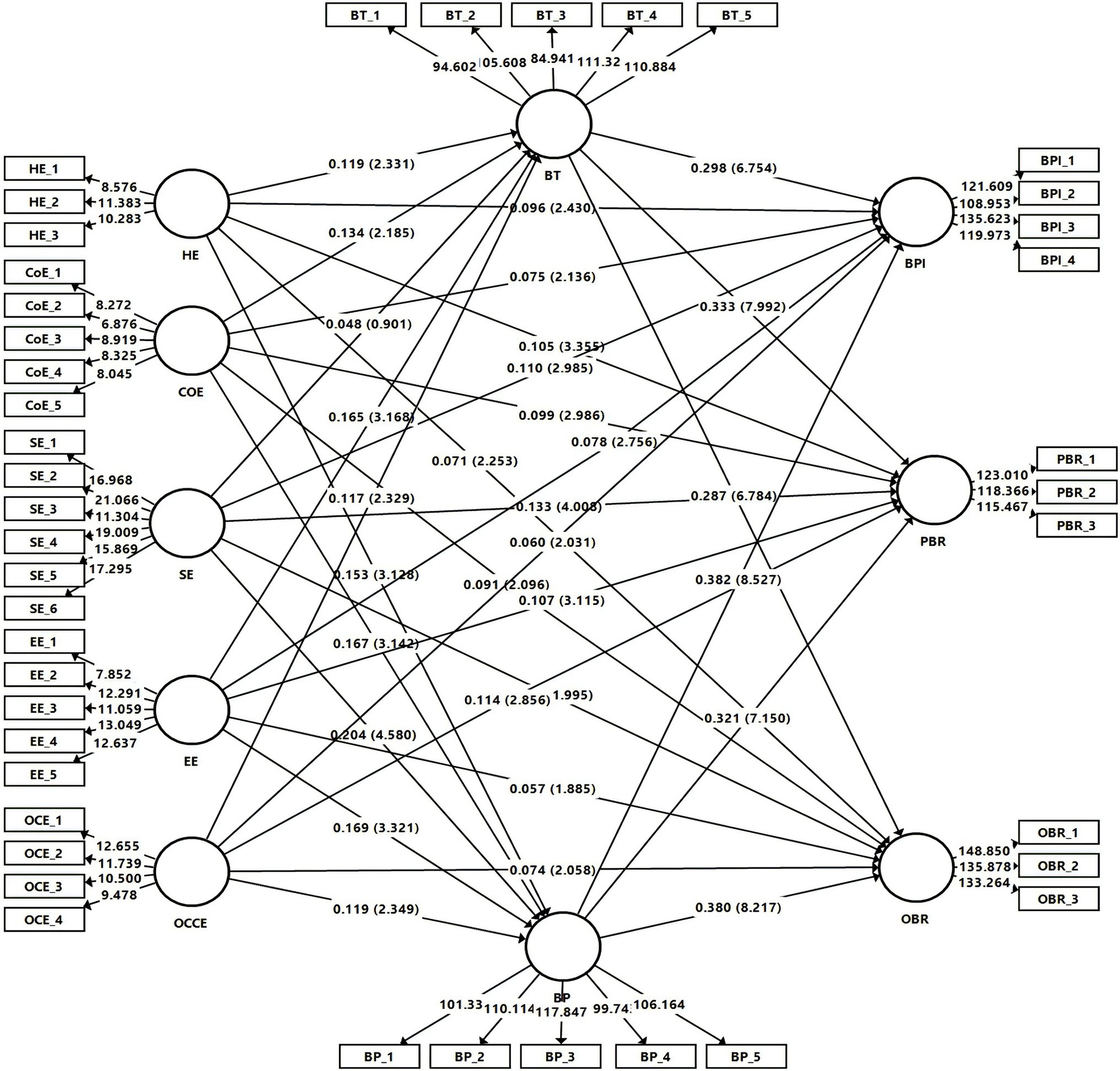

FIGURE 1

Methodology

Measurement Instruments

The items and instruments used in the questionnaire to measure the constructs were adapted from previously validated studies to maintain reliability and validity. We used twenty-three items to assess CCE: six items for EE, three items for HE, five items for SE, five items for CoE, and four items for OCCE. All items were adapted from Verleye (2015). We measured the BE dimensions with ten items: four items for BPI, three items for PBR, and three items for OBR, adapted from Badrinarayanan and Becerra (2013). We measured BT using five items adapted from Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) and Munuera-Alemán et al. (2003), whereas for BP, we used five items adapted from Mostafa and Kasamani (2020) and Thomson et al. (2005). all the items were slightly modified from the existing literature to suit the study context. For example, the original item “I spread positive word of mouth about the brand” was adapted to “I spread positive word of mouth about my favorite hotpot brand.” Two marketing professors reviewed the questionnaire to ensure face and content validity; we distributed the questionnaire after applying their suggestions. Moreover, to measure all the items, we used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Selection of the Co-creation Setting

In 2017, there were approximately 300,000 hotpot restaurants across China, and in 2020, 13,000 new restaurants were opened to meet increasing demand (Statista, 2020). Chinese hotpot restaurants provide customers with a complete CCE as customers can cook their own food. These restaurants provide customers with raw food and ingredients, which they mix up and cook according to their tastes and preferences in a boiling broth on the dining table. The entire process is similar to the co-creation service experience, wherein companies allow customers to co-create their own experience (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004). It is similar to customized offerings where actors invite other actors to participate in the production of service offerings (Mathis et al., 2016). We collected data from international travelers who dined at hotpot restaurants during their stay in China.

Accordingly, we developed a structured questionnaire divided into three parts. In the first part, we explained the study purpose and asked respondents to recall their recent experiences at a hotpot restaurant and answer questions on a given scale to describe their experience and satisfaction. We assured them of the confidentiality of the information provided. In the second part, we collected the respondents’ demographic data and their country of origin. The third part comprised items that assessed the variables of interest. The current research conducted an online questionnaire, employing a structured and non-probabilistic convenience sample and cross-sectional survey. We conducted our survey questionnaire on Sojump platform. We shared the link among online group chats of foreigners living in China with the help of group chat administrators as it is the fastest way to access a large sample group in a short period of time. We forwarded the questionnaire along with a message stating that only foreigners who have dined at a Chinese hotpot restaurant within the last 3 months are eligible to fill the survey. Consequently, we distributed 600 self-administered questionnaires and received 521 responses within a month. Of these responses, 68 were excluded from the analysis because they contained unengaged responses and missing information. Therefore, the final sample comprised 453 foreign respondents (response rate of 75.5%) from 61 countries across six continents.

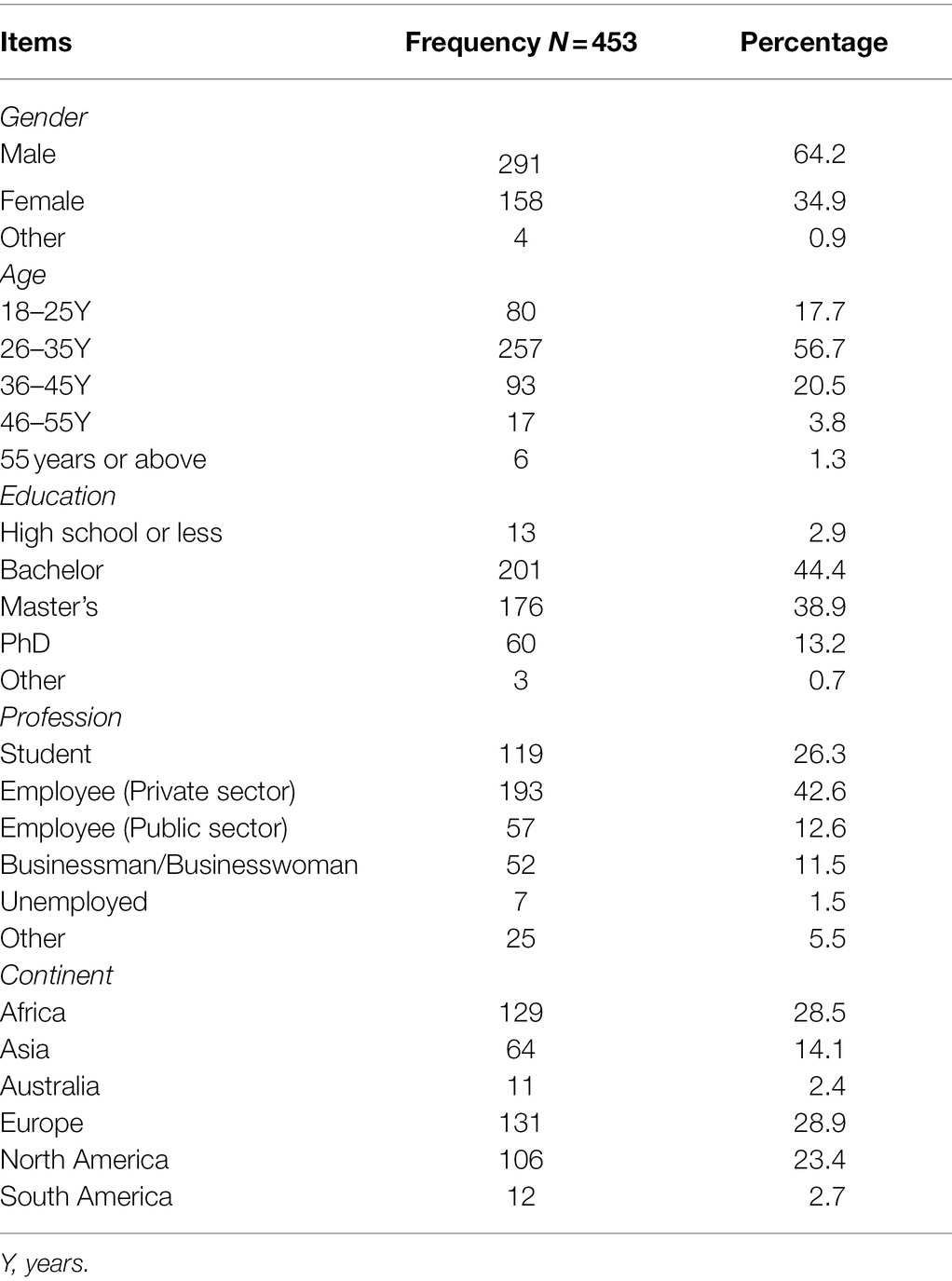

Our sample included 291 men (64.2%) and 158 women (34.9%). The majority of respondents (81%) were aged between 26 and 55 years. Additionally, 96.5% had at least a bachelor’s degree, and 66.7% were employed (public and private sector) or self-employed (businesspersons). Table 1 reports the demographic details of the respondents.

Data Analysis

The present research used IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 to analyze the demographics and the common method bias. We assessed our measurement and structural model with partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) on SmartPLS version 3.3.3. In recent years, PLS has become a very popular and powerful alternative to covariance explanation methods, such as AMOS and LISREL (Wasko and Faraj, 2005). PLS is better suited for explaining complex relationships, and it synchronously estimates the measurement and the structural model. The data were analyzed in two stages: In the first stage, we tested data reliability and validity, and in the second stage, we tested the hypotheses.

Results

The data were analyzed in two stages: In the first stage, we tested data reliability and validity, and in the second stage, we tested the hypotheses.

Common Method Bias

Common method bias is a crucial issue in behavioral research. We tested it using Harman’s single-factor approach. The variance extracted by a single factor was 25.099%, which is less than 50%, indicating no common method bias in this study.

Assessment of Measurement Model

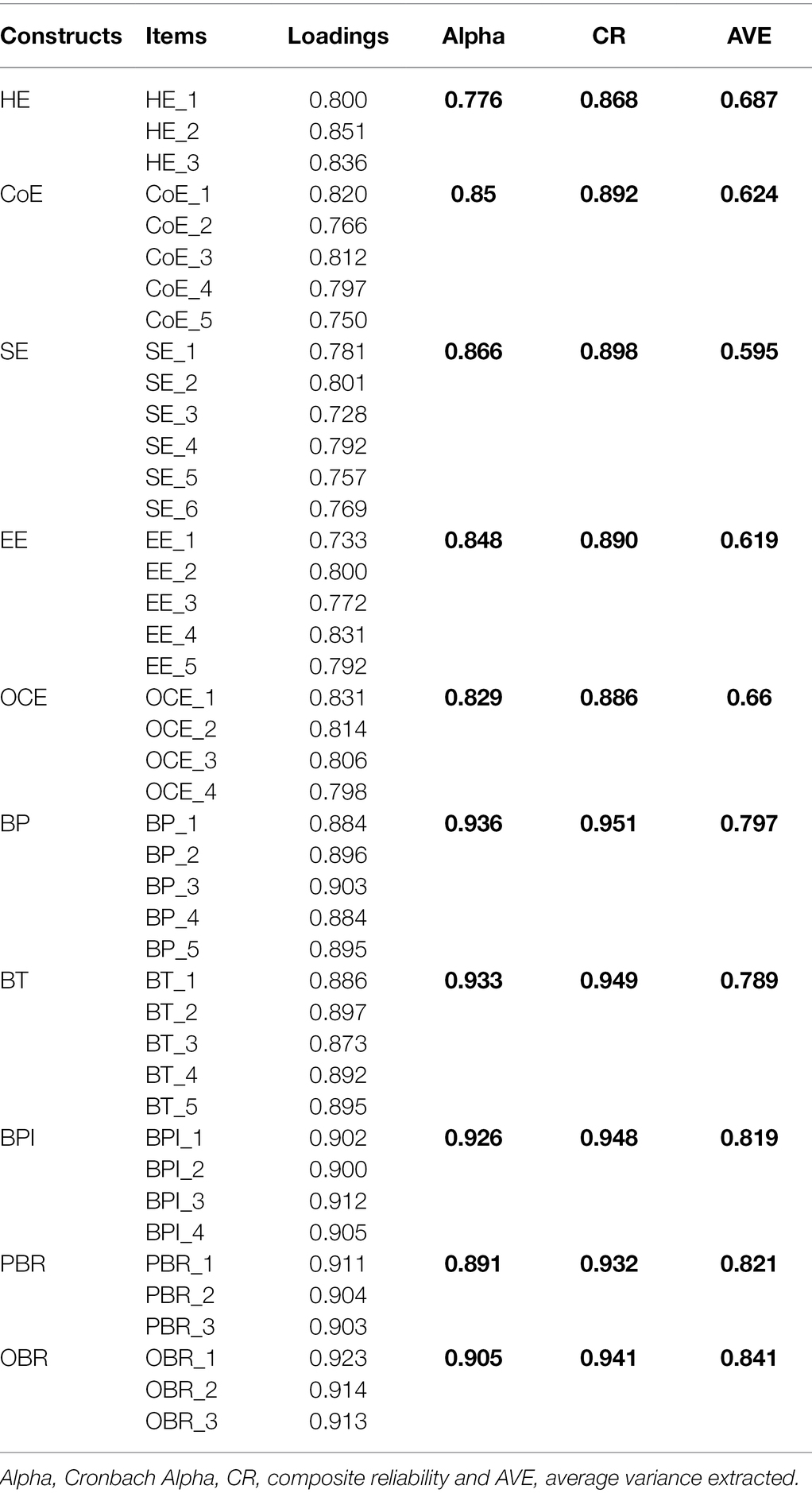

Ringle et al. (2015) stated that the measurement model must establish reliability and validity. In the reliability analysis, the alpha and composite reliability were higher than 0.7. For convergent validity, the standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.5. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were greater than 0.5 and met the threshold level. Table 2 presents details on composite reliability (CR), alpha, AVE, and outer loading.

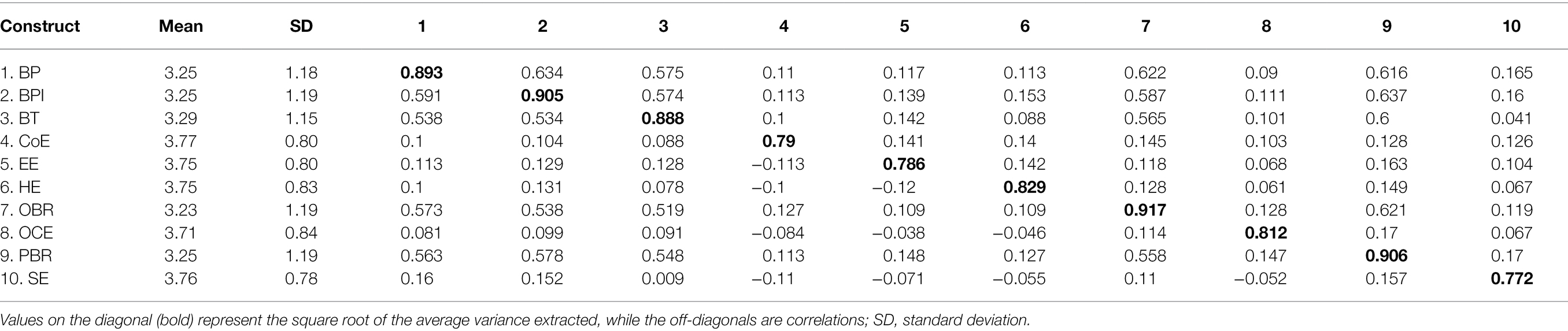

For discriminant validity, we applied two methods, namely, the Fornell Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. In the Fornell and Larcker method, the square root of each latent variable’s AVE was greater than the correlation of its coefficient, which indicates discriminant validity in our study (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Henseler et al. (2015) stated that the HTMT values must be lower than 0.85, which was the case in our study, indicating discriminant validity (see Table 3). We further examined the variance inflation factor (VIF), and the VIF values did not exceed 5; therefore, multicollinearity was acceptable in this study.

Assessment of Structural Model

To conduct hypothesis testing, the statistical bootstrap technique was applied with the recommended sample size of 5,000 using SmartPLS software version 3.3.3. (Ringle et al., 2015).

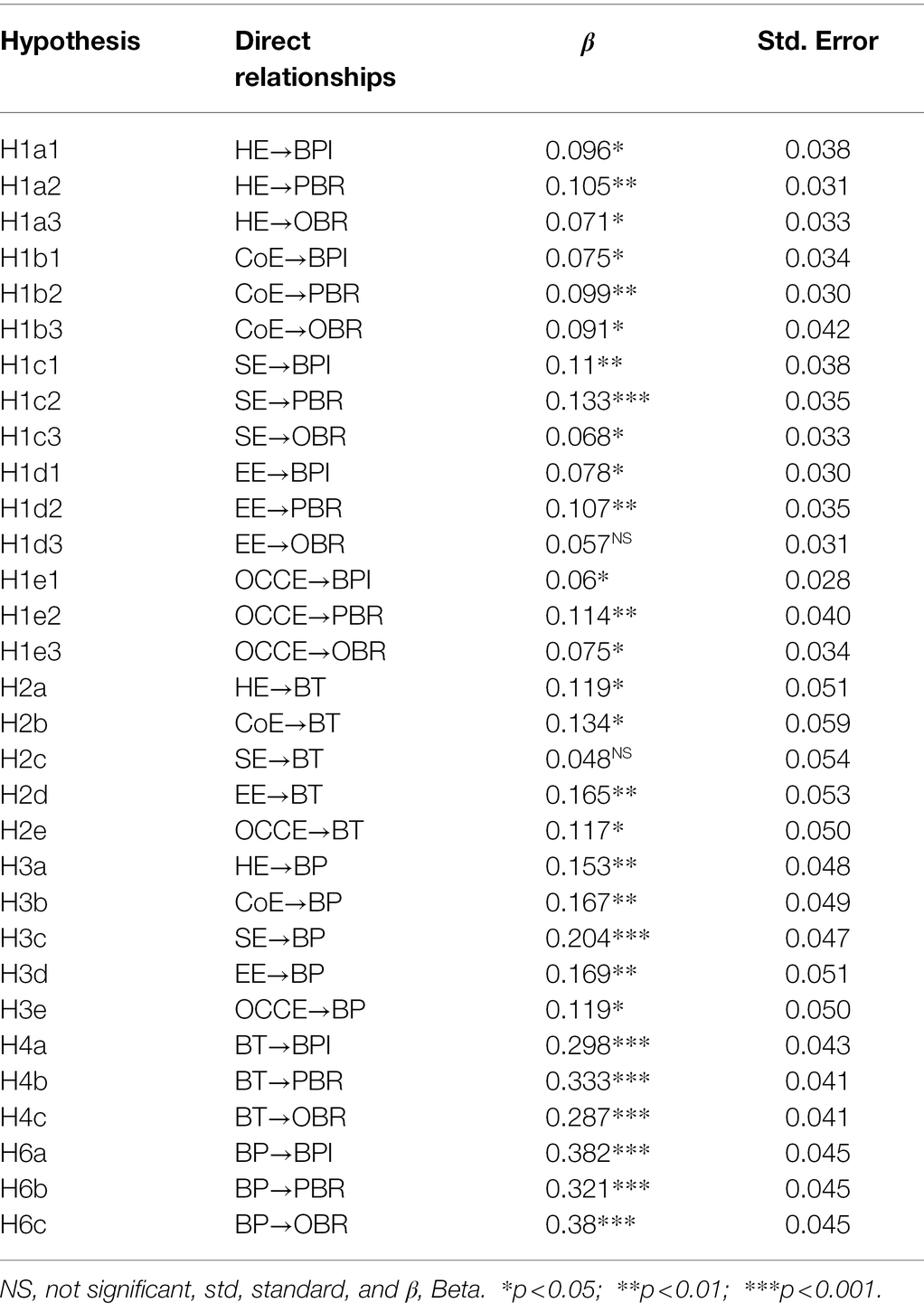

H1’s findings revealed that CCE dimensions, namely, HE (β = 0.96, 0.105, and 0.071), CoE (β = 0.075, 0.099, and 0.091), SE (β = 0.11, 0.133, and 0.068), EE (BPI: β = 0.078 and PBR: β = 0.107), and OCCE (β = 0.06, 0.114, and 0.075) positively impact the BPI, PBR, and OBR dimensions of BE. However, the relationship between EE and OBR is insignificant (β = 0.057).

Furthermore, CCE dimensions, including HE (β = 0.119), CoE (β = 0.134), EE (β = 0.165), and OCCE (β = 0.117) directly contribute to enhancing BT, whereas SE (β = 0.048) was found to be non-significant. The analysis of H3 revealed that CCE dimensions, namely, HE (β = 0.153), CoE (β = 0.167), SE (β = 0.204), EE (β = 0.169), and OCCE (β = 0.119) directly increase BP.

Findings for H4 highlighted that BT strongly impacts BE dimensions, namely, BPI (β = 0.298), PBR (β = 0.333), and OBR (β = 0.287). Additionally, results revealed that BP has a positive and significant impact on the BPI (β = 0,382), PBR (β = 0.321), and OBR (β = 0.38) dimensions of BE. Table 4 illustrates the direct effect.

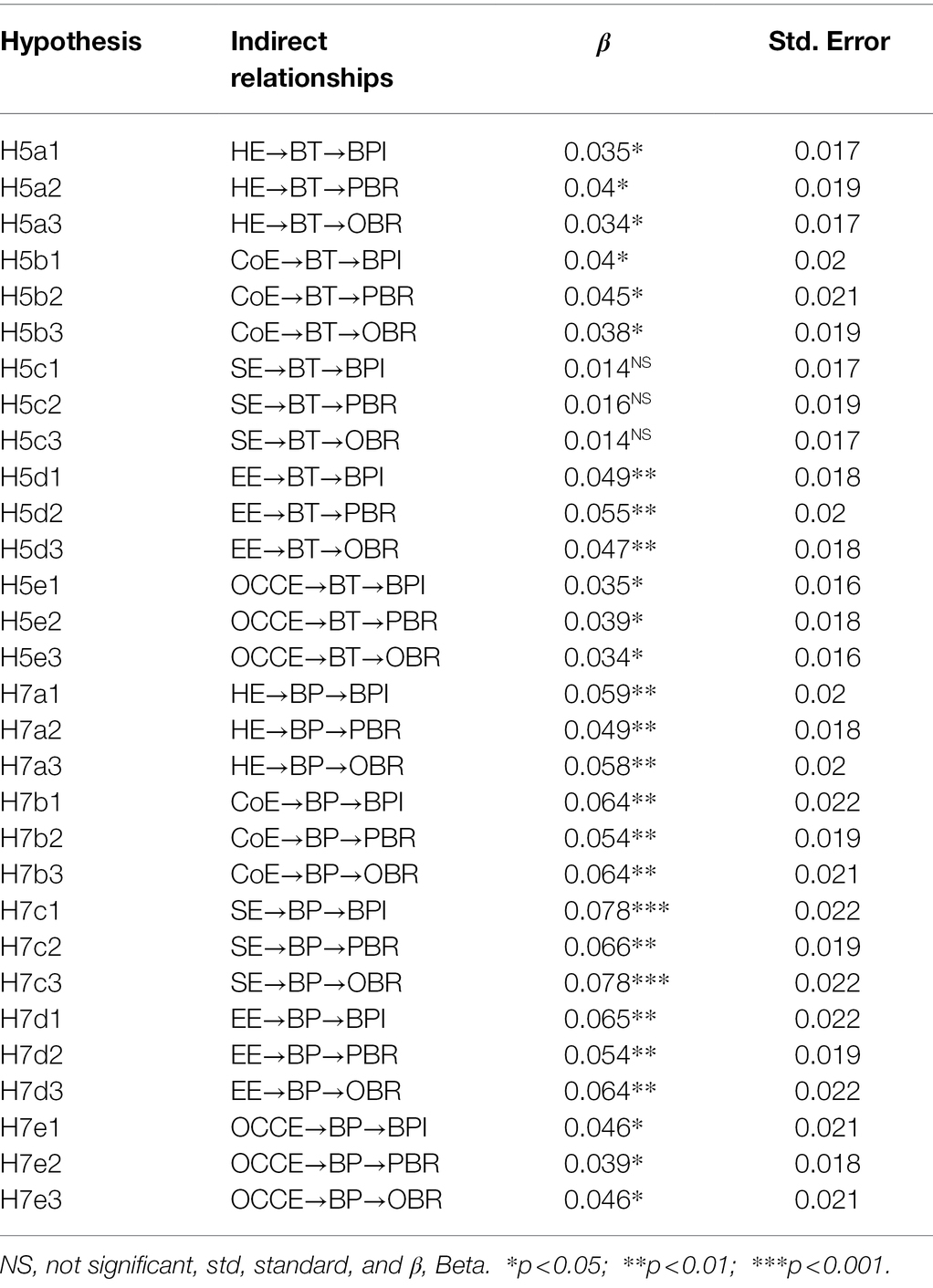

The mediation effect results demonstrated that BT mediates the relationship between the CCE dimensions, including HE (β = 0.035, 0.04, and 0.034), CoE (β = 0.04, 0.034, and 0.038), EE (β = 0.049, 0.055, and 0.047) and OCCE (β = 0.035, 0.039, and 0.034), and BE dimensions of BPI, PBR, and OBR. However, BT does not mediate the relationship between SE and BE dimensions (H5).

Furthermore, we found that BP mediates the relationship between the CCE dimensions, namely, HE (β = 0.059, 0.049, and 0.058), CoE (β = 0.064, 0.054, and 0.064), SE (β = 0.076, 0.066, and 0.078), EE (β = 0.065, 0.054, and 0.064) and OCCE (β = 0.046, 0.039, and 0.046), and BE dimensions, namely, BPI, PBR, and OBR (H7; see Table 5). The structural model is given in Figure 2.

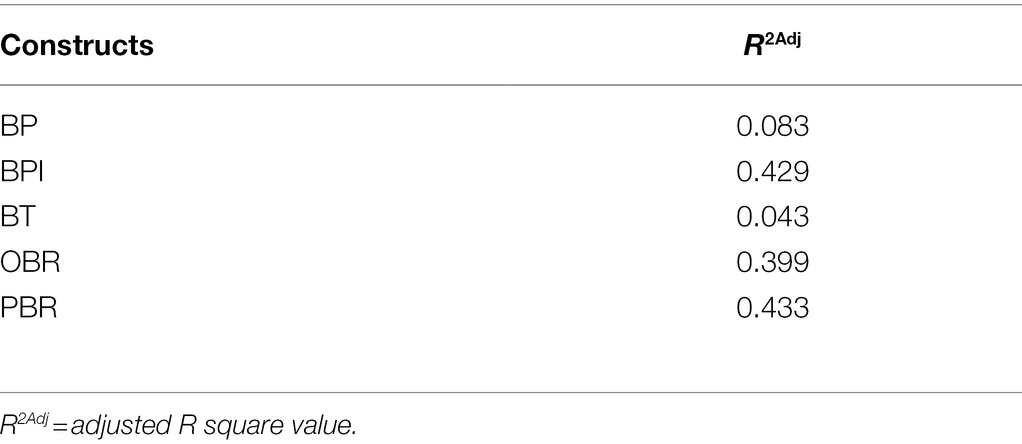

R-squared is the proportion of an endogenous construct’s variance explained by its predictor constructs. According to Hair et al. (2011), 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 denote small, medium, and large effects. Table 6 represents the adjusted R2 values.

Discussion

Currently, the world is rapidly developing and globalization is influencing all countries. Accordingly, several tourism and hospitality markets around the world are trying to figure out ways to improve their services and increase customer satisfaction. This study focuses on value co-creation and investigates the impact of international tourists’ CCE on BE, BT, and BP.

The first hypothesis’s findings revealed that CCE dimensions, namely, HE, SE, and OCCE positively impact the BPI, PBR, and OBR dimensions of BE. A plausible reason is that customers who participated in the value co-creation activity feel less deprived and more fulfilled (Navarro et al., 2015); therefore, they will actively buy the brand, recommend it to others and defend it from any form of criticism. Customers are more likely to show behavioral support to a brand that enriches their social lives, entertains them, and provides new knowledge and information. The findings further revealed that the relationship between EE and OBR is insignificant. This results in the fact that EE does not sufficiently engage international travelers in evangelistic behaviors. International travelers actively purchase the brand and recommend it to others; however, spreading negative opinions about other restaurant brands is perceived as a burden to them.

Furthermore, CCE dimensions, including HE, CoE, EE, and OCCE directly contribute to enhancing BT; however, SE was found to be non-significant. This may be because international travelers seek to connect with like-minded people and gain better self-esteem through co-creation activity; however, they do not necessarily place their confidence in the brand and rely on it. The analysis of the third hypothesis revealed that CCE dimensions directly increase BP, thus enriching extant hospitality and tourism literature. These findings are reasonable, as engaged customers are key to a brand’s success. Findings suggest that customers who participate in the co-creation process develop a high level of enthusiasm and desire and are emotionally connected to the brand. Passion is achieved by providing customers with real value through every aspect of the customer–brand relationship.

Findings for the fourth hypothesis highlighted that BT strongly impacts BE dimensions, namely, BPI, PBR, and OBR, which is in line with extant literature (Badrinarayanan and Becerra, 2013; Doss, 2014; Riorini and Widayat, 2015). These findings suggest that when customers trust a brand, they actively purchase it and engage many other customers. Customers’ trust in a brand reflects a positive feeling and the willingness to be loyal to it, therefore engendering brand evangelistic behaviors. Additionally, The mediation effect results of the fifth hypothesis demonstrated that BT mediates the relationship between the CCE dimensions, including HE, CoE, EE, and OCCE, and BE dimensions of BPI, PBR, and OBR. However, BT does not mediate the relationship between SE and BE dimensions. A reasonable explanation is that social relationships do not lead to brand trust. International travelers do not necessarily rely on the brand, which, in turn, affects their behavior.

Moreover, results for the sixth hypothesis revealed that BP has a positive and significant impact on the BPI, PBR, and OBR dimensions of BE, consistent with Matzler et al. (2007), enriching extant BE literature. Passion is deemed the core of the emotional connection between customers and a brand. Passionate customers are more enthusiastic and are considered profitable advocates of a brand. Their behavior goes beyond purchasing a specific brand to recommend it and denigrate rival brands that present a threat. Furthermore, we found that BP mediates the relationship between the CCE dimensions, namely, HE, CoE, SE, EE, and OCCE, and BE dimensions, namely, BPI, PBR, and OBR. These findings are reasonable as when customers who participated in the co-creation activity had a positive experience, they become passionate about the brand, and therefore, engage in evangelistic behaviors (Doss, 2014). These findings are consistent with Pansari and Kumar's (2017) theory of engagement.

Theoretical Implications

The current study contributes to the branding, hospitality, and tourism literature in multiple ways. First, Im and Qu (2017) stressed that most studies on co-creation are scenario-based. This study examined the proposed conceptual model in a realistic co-creation setting (i.e., hotpot restaurants) that explains how international tourists’ CCE can enhance BT, increase BP, and stimulate brand evangelistic behaviors, offering theoretical grounds for future research on CCE and BE.

Second, extant literature suggested that a positive customer experience is necessary to achieve performance and relational benefits (Hussain et al., 2020). However, such experience must be scrutinized at a dimensional level to understand how each dimension affects consumer behavior. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first attempt to reveal how the multidimensional concept of CCE affects the multidimensional concept of BE. Our research is also the first to investigate CCE and branding relationships, including BT and BP.

Third, the post-hoc analysis investigating BT and BP’s mediating role between CCE and BE is a valuable contribution. The findings highlighted that BT has a positive mediation effect on CCE dimensions, including HE, CoE, EE, and OCCE, and BE dimensions, namely, BPI, PBR, and OBR, whereas the SE mediation effect is non-significant. Additionally, BP was found to mediate all dimensions of CCE and BE.

Fourth, research on CCE is limited in the hospitality literature with respect to international tourists’ perspectives. Previous research has investigated the CCE of local diners (i.e., Hussain et al., 2020). The current study investigates international tourists’ CCE and its impact on BE.

Fifth, BE has been investigated in banking service (Riorini and Widayat, 2015), the video game industry (Marticotte et al., 2016), and social media use (Harrigan et al., 2020). The current research introduces the concept of BE in the hospitality industry; specifically, it investigates how the dining experience of international tourists instigates brand evangelistic behaviors.

Finally, BE has been a hot topic in marketing and branding literature (Harrigan et al., 2020). The literature has treated BE as a higher-order construct (e.g., Matzler et al., 2007) or a construct with two dimensions (e.g., Harrigan et al., 2020). This study considered BE as a construct with three dimensions: BPI, PBR, and OBR, further clarifying the BE phenomenon.

Managerial Implications

As we evolve rapidly to consider CCE as the basis of value, the interaction between the company and the customer becomes the locus of value co-creation (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004). The current study provides valuable insight for an in-depth understanding of foreign tourists with respect to restaurants engaged in the profitable Chinese marketplace.

The findings suggest that firms should engage customers in the co-creation of value where the interaction between customer and employee is crucial to increase customers’ BT, BP, and brand evangelistic behaviors. To stimulate optimized customer experience for brand success, restaurant managers can focus on the various aspects of value co-creation (i.e., HE, CoE, SE, EE, and OCCE). For instance, they can allow tourists to co-create a service experience that suits their context, make the brand engaging and meaningful, and create a better customer experience. Managers can also provide an innovative experience environment for new co-creation experiences (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004) and provide customer support to help customers co-create. Optimizing CCE will cause customers to show their passion for the brand and rely on it. Consequently, customers will develop brand evangelistic behaviors, such as PBR, which help attract additional customers who may otherwise not be attracted via conventional marketing channels.

Pansari and Kumar's (2017) theory of engagement states that the consumer–brand relationship is neither static nor instant. Therefore, restaurant brand managers must stimulate a positive customer experience, which will eventually enhance BP and lead to brand evangelistic behaviors. A passionate customer is an asset to a brand. Brand managers can instill BP by implementing and providing platforms and tools for a pleasurable CCE (HE), as customers participating in the value co-creation activity seek fun, pleasure, and entertainment.

Additionally, restaurant brand managers can offer customers the opportunity to learn about service, products, and technologies (CoE) and provide a suitable platform for them to connect with like-minded people (SE). Customers involved in the co-creation process give suggestions and feedback, which reduce risks associated with offering undesirable products or services. Further, managers can provide compensation commensurate with the effort made during the co-creation process (pragmatic and economic benefit). For instance, they could formulate a reward system (company swag) and focus on sophisticated reward programs.

Limitations and Recommendations

The current study has several limitations. First, we used a structured questionnaire to assess international tourists’ participation. Given that it may limit tourists’ expression, future research may employ a mixed-methods approach. Second, we focused on co-creation in a restaurant setting; future research could specifically focus on co-creation activities in tourism services and online shopping. Third, we did not consider the control variables’ role in this research. Therefore, future research may include control variables, such as tourists’ gender, age, and the frequency of dining at a hotpot restaurant. Fourth, we associated BT and BP to understand the relationship between CCE and BE. Researchers may use other variables, such as customer perceived value, brand love, and affective commitment to better understand the relationship.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by East China University of Science and Technology. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

GN provided writing, editing, data collection, initial analysis, methodology, and conceptualization. FJ and KH provided review and critical advices. SJ and MR worked on the result. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

CCE, Co-creation experience; HE, Hedonic experience; SE, Social experience; EE, Economic experience; CoE, Cognitive experience; OCCE, Overall co-creation experience; BE, Brand evangelism; BPI, Brand purchase intention; PBR, Positive brand referrals; OBR, Oppositional brand referrals; BT, Brand trust; BP, Brand passion.

References

Ahn, J., Lee, C.-K., Back, K.-J., and Schmitt, A. (2019). Brand experiential value for creating integrated resort customers’ co-creation behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 81, 104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.009

Alarcón López, R., Ruiz de Maya, S., and López, I. (2017). Sharing co-creation experiences contributes to consumer satisfaction. Online Inf. Rev. 41, 969–984. doi: 10.1108/OIR-09-2016-0267

Albert, N., and Merunka, D. (2013). The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 30, 258–266. doi: 10.1108/07363761311328928

Albert, N., and Valette-Florence, P. (2010). Measuring the love feeling for a brand using interpersonal love items. J. Mark. Dev. Comp. 5, 57–63.

Badrinarayanan, V., and Becerra, E. (2013). Influence of Brand Trust and brand identification on brand evangelism. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 22, 371–383. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-09-2013-0394

Ballester, E., and Munuera-Alemán, J.-L. (2005). Does brand trust matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 14, 187–196. doi: 10.1108/10610420510601058

Bauer, H., Heinrich, D., and Martin, I. (2007). “How to create high emotional consumer-brand relationships? the causalities of brand passion.” in Proceedings of the Australia and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference. eds. M. Thyne, K. Deans and J. Gnoth. December, 2007; Dunedin, 2189–2198.

Baumann, J., and Le Meunier-FitzHugh, K. (2013). Trust as a facilitator of co-creation in customer-salesperson interaction – an imperative for the realization of episodic and relational value? AMS Rev. 4, 5–20. doi: 10.1007/s13162-013-0039-8

Becerra, E., and Korgaonkar, P. (2011). Effects of trust beliefs on consumers’ online intentions. Eur. J. Mark. 45, 936–962. doi: 10.1108/03090561111119921

Blasco-Arcas, L., Hernandez-Ortega, B., and Jimenez-Martinez, J. (2014). The online purchase as a context for co-creating experiences. Drivers of and consequences for customer behavior. Internet Res. 24, 393–412. doi: 10.1108/IntR-02-2013-0023

Campos, A. C., Mendes, J., do Valle, P. O., and Scott, N. (2016). Co-creation experiences: attention and memorability. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 33, 1309–1336. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2015.1118424

Chae, H., Kim, S., Lee, J., and Park, K. (2020). Impact of product characteristics of limited edition shoes on perceived value, brand trust, and purchase intention; focused on the scarcity message frequency. J. Bus. Res. 120, 398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.040

Chaudhuri, A., and Holbrook, M. (2001). The chain of effects From Brand Trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 65, 81–93. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

Chen, Z. (2018). A pilot study of the co-creation experience in traditional Cantonese teahouses in Hong Kong. J. Herit. Tour. 13, 506–527. doi: 10.1080/1743873x.2018.1444045

Cova, B., Dalli, D., and Zwick, D. (2011). Critical perspectives on consumers’ role as ‘producers’: broadening the debate on value co-creation in marketing processes. Mark. Theory 11, 231–241. doi: 10.1177/1470593111408171

Diputra, I., and Yasa, N. N. (2021). The influence Of product quality, brand image, Brand Trust On customer satisfaction and loyalty. Am. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 4, 25–34.

D’lima, C. (2018). Brand passion and its implication on consumer behaviour. Int. J. Bus. Fore. Mark. Intell. 4:30. doi: 10.1504/IJBFMI.2018.10009307

Doss, S. K. (2014). “Spreading the Good Word”: Toward an Understanding of Brand Evangelism. in The Sustainable Global Marketplace, 444–444.

Fehr, B., and Anne, B. (1988). Prototype analysis of the concepts of love and commitment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 55, 557–579. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.4.557

Fetscherin, M., and Heinrich, D. (2015). Consumer-brand relationship research: A Bibliometric citation meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 68, 380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.010

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I., and Belief, A. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Contemp. Sociol. 6:244. doi: 10.2307/2065853

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Füller, J. (2010). Refining virtual co-creation from a consumer perspective. Calif. Manag. Rev. 52, 98–122. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2010.52.2.98

Ghorbanzadeh, D., Saeednia, H., and Rahehagh, A. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of brand passion among young smartphone consumers: evidence of Iran. Cogent Bus. Manag. 7:1712766. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2020.1712766

Gibbs, D., Haven-Tang, C., and Ritchie, C. (2021). Harmless flirtations or co-creation? Exploring flirtatious encounters in hospitable experiences. Tour. Hosp. Res. 21, 473–486. doi: 10.1177/14673584211049297

Gilal, F. G., Channa, N., Gilal, N., Gilal, R., Gong, Z., and Zhang, N. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and brand passion among consumers: theory and evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 27, 2275–2285. doi: 10.1002/csr.1963

Gilal, F. G., Gilal, N., Gilal, R., Gon, Z., Gilal, W., and Tunio, M. N. (2021a). The ties that bind: do brand attachment and brand passion translate Into consumer purchase intention? Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 29, 14–38. doi: 10.7206/cemj.2658-0845.39

Gilal, F. G., Paul, J., Gilal, N. G., and Gilal, R. G. (2021b). Strategic CSR-brand fit and customers’ brand passion: theoretical extension and analysis. Psychol. Mark. 38, 759–773. doi: 10.1002/mar.21464

Gilal, F. G., Zhang, J., Gilal, N., and Gilal, R. (2018). Association between a parent’s brand passion and a child’s brand passion: a moderated moderated-mediation model. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 11, 91–102. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S161755

Grönroos, C. (2011). Value co-creation in service logic: a critical analysis. Mark. Theory 11, 279–301. doi: 10.1177/1470593111408177

Guan, J., Wang, W., Guo, Z., Chan, J. H., and Qi, X. (2021). Customer experience and brand loyalty in the full-service hotel sector: the role of brand affect customer experience and brand loyalty. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 33, 1620–1645. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2020-1177

Ha, H.-Y., and Perks, H. (2005). Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: brand familiarity, satisfaction and brand trust. J. Consum. Behav. 4, 438–452. doi: 10.1002/cb.29

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Prac. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Harrigan, P., Roy, S., and Chen, T. (2020). Do value co-creation and engagement drive brand evangelism? Mark. Intell. Plan. doi:doi: 10.1108/MIP-10-2019-0492 [Epub ahead of print].

Hemsley-Brown, J., Melewar, T. C., Nguyen, B., and Wilson, E. (2016). Exploring brand identity, meaning, image, and reputation (BIMIR) in higher education: A special section. J. Bus. Res. 69, 3019–3022. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.016

Henseler, J., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hsu, L.-C. (2018). Investigating the brand evangelism effect of community fans on social networking sites: perspectives on value congruity. Online Inf. Rev. 43, 842–866. doi: 10.1108/OIR-06-2017-0187

Huber, F., Meyer, F., and Schmid, D. (2015). Brand love in progress – the interdependence of brand love antecedents in consideration of relationship duration. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 24, 567–579. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-08-2014-0682

Hurriyati, R., and Sofwan, D. M. P. (2015). Analysis of co-creation experience towards a creative city as a toursim destination and its impact on revisit intention. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 6, 353–364.

Husain, R., Ahmad, A., and Khan, B. M. (2022). The impact of brand equity, status consumption, and brand trust on purchase intention of luxury brands. Cogent Bus. Manag. 9:2034234. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2022.2034234

Hussain, K., Jing, F., Junaid, M., Bukhari, F., and Shi, H. (2019). The dynamic outcomes of service quality: a longitudinal investigation. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 29, 513–536. doi: 10.1108/JSTP-03-2019-0067

Hussain, K., Jing, F., Junaid, M., Zaman, Q., and Shi, H. (2020). The role of co-creation experience in engaging customers with service brands. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 30, 12–27. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2537

Hussain, K., Jing, F., and Perveen, K. (2018). How do foreigners perceive? Exploring foreign diners’ satisfaction with service quality of Chinese restaurants. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 23, 613–625. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2018.1476391

Im, J., and Qu, H. (2017). Drivers and resources of customer co-creation: A scenario-based case in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 64, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.03.007

Jaakkola, E., Helkkula, A., and Aarikka-Stenroos, L. (2015). Service experience co-creation: conceptualization, implications, and future research directions. J. Serv. Manag. 26, 182–205. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-12-2014-0323

Javed, M., Roy, S., and Mansoor, B. (2015). Will you defend your loved brand? Brand defense superseding advocacy. Consumer Brand Relationships Meaning, Measuring, Managing. eds. M. Fetscherin and T. Heilmann. (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 31–54.

Kallmuenzer, A., Peters, M., and Buhalis, D. (2019). The role of family firm image perception in host-guest value co-creation of hospitality firms. Curr. Issue Tour. doi:doi: 10.1080/13683500.2019.1611746 [Epub ahead of print].

Kamboj, S., Sarmah, B., Gupta, S., and Dwivedi, Y. (2018). Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: applying paradigm of stimulus-organism-response. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 39, 169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.001

Keh, H. T., Pang, J., and Peng, S. (2007). “Understanding and measuring brand love.” in Paper presented at Society for Consumer Psychology. Advertising and Consumer Psychology Conference Proceedings. Santa Monica; June, 2007; 84–88.

Kim, S., Lee, J., and Prideaux, B. (2014). Effect of celebrity endorsement on tourists’ perception of corporate image, corporate credibility and corporate loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 37, 131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.11.003

Liao, S.-H., Chung, Y.-C., Hung, Y. R., and Pa, R. (2011). “The impacts of brand trust, customer satisfaction, and brand loyalty on word-of-mouth.” in 2010 IEEM-IEEE Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management.

Ling, X., Shahzad, F., Abrar, Z., and Khattak, J. (2021). Determinants of the intention to purchase branded meat: mediation of Brand Trust. SAGE Open 11:215824402110326. doi: 10.1177/21582440211032669

Liu, Y., and Jang, S. (2009). Perceptions of Chinese restaurants in the U.S.: what affects customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 28, 338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.10.008

Marticotte, F., Arcand, M., and Baudry, D. (2016). The impact of brand evangelism on oppositional referrals towards a rival brand. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 25, 538–549. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-06-2015-0920

Mathis, E. F., Kim, H. L., Uysal, M., Sirgy, J. M., and Prebensen, N. K. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Ann. Tour. Res. 57, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.023

Matzler, K., Pichler, E. A., and Hemetsberger, A. (2007). Who is spreading the word? The positive influence of extraversion on consumer passion and brand evangelism. Mark. Theory App. 18, 25–32.

McConnell, B., and Huba, J. (2003). Creating Customer Evangelists: How Loyal Customers Become a Volunteer Sales Force. Chicago: Dearborn Trade Pub.

Meng, B., and Cui, M. (2020). The role of co-creation experience in forming tourists’ revisit intention to home-based accommodation: extending the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 33:100581. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100581

Merz, M., Zarantonello, L., and Grappi, S. (2018). How valuable are your customers in the brand value co-creation process? The development of a customer co-creation value (CCCV) scale. J. Bus. Res. 82, 79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.018

Mishra, M., Kesharwani, A., and Gautam, D. R. V. (2021). Examining the relationship between consumer brand relationships and brand evangelism. Aust. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 6, 84–95. doi: 10.52283/NSWRCA.AJBMR.20210601A07

Mohammadi, F., Yazdani,, Reza, Hamid, Jami Pour, M., and Soltani, M. (2020). Co-creation in tourism: a systematic mapping study. Tour. Rev. doi:doi: 10.1108/TR-10-2019-0425 [Epub ahead of print].

Morgan, R., and Hunt, S. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 58, 20–38. doi: 10.2307/1252308

Mostafa, R., and Kasamani, T. (2020). Brand experience and brand loyalty: is it a matter of emotions? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. doi:doi: 10.1108/APJML-11-2019-0669 [Epub ahead of print].

Mukherjee, K. (2020). Social media marketing and customers’ passion for brands. Mark. Intell. Plan. 38, 509–522. doi: 10.1108/MIP-10-2018-0440

Munuera-Alemán, J.-L., Ballester, E., and Yague-Guillen, M. (2003). Development and validation of a Brand Trust scale. Int. J. Mark. Res. 45, 1–18. doi: 10.1177/147078530304500103

Navarro, S., Llinares, C., and Garzón, D. (2015). Exploring the relationship between co-creation and satisfaction using QCA. J. Bus. Res. 69, 1336–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.103

Oetting, M., and Jacob, F. (2007). Empowered Involvement and Word of Mouth: An Agenda for Academic Inquiry. ESCP-EAP European School of Management.

Pansari, A., and Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement–The construct, antecedents and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 45, 294–311. doi: 10.1007/s11747-016-0485-6

Pourazad, N., and Pare, V. (2015). “Conceptualising the behavioural effects of brand passion among fast fashion young customers.” in Proceedings of Sydney International Business Research Conference; Sydney, NSW, Australia; Australia: University of Western Sydney Campbelltown, 17–19.

Pourazad, N., Stocchi, L., and Pare, V. (2019). Brand attribute associations, emotional consumer-brand relationship and evaluation of brand extensions. Australas. Mark. J. 27, 249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.07.004

Prahalad, C., and Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 18, 5–14. doi: 10.1002/dir.20015

Rachão, S., Breda, Z., Fernandes, C., and Joukes, V. (2019). Food tourism and regional development: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 21, 33–49. doi: 10.54055/ejtr.v21i.357

Ramaswamy, V., and Ozcan, K. (2018). What is co-creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. J. Bus. Res. 84, 196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.027

Riorini, S., and Widayat, C. (2015). Brand relationship and its effect towards brand evangelism to banking service. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 8, 33–45. doi: 10.21632/irjbs.8.1.33-45

Samson, A. (2006). Understanding the buzz that matters: negative vs positive word of mouth. Int. J. Mark. Res. 48, 647–657. doi: 10.1177/147078530604800603

Seifert, C., and Kwon, W.-S. (2019). SNS eWOM sentiment: impacts on brand value co-creation and trust. Mark. Intell. Plan. doi: 10.1108/MIP-11-2018-0533 [Epub ahead of print].

Sharma, P., Sadh, A., Billore, A., and Motiani, M. (2021). Investigating brand community engagement and evangelistic tendencies on social media. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 31, 16–28. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-01-2020-2705

Shaw, G., Bailey, A., and Williams, A. (2011). Aspects of service-dominant logic and its implications for tourism management: examples from the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 32, 207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.020

Statista (2020). China: number of hot pot restaurants 2013–2022 | Statista. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1121121/china-number-of-hot-pot-restaurants/ (Accessed August 27, 2021).

Statista (2021). 4th China: Tourists in China 2018, by country of origin. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/234149/tourists-in-china-by-country-of-origin/ (Accessed October 15, 2021).

Sternberg, R. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychol. Rev. 93, 119–135. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119

Swimberghe, K., Astakhova, M., and Wooldridge, B. (2014). A new dualistic approach to brand passion: harmonious and obsessive. J. Bus. Res. 67, 2657–2665. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.003

Thomson, M., Macinnis, D., and Park, C. (2005). The ties That bind: measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 15, 77–91. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1501_10

Tu, Y., Neuhofer, B., and Viglia, G. (2018). When co-creation pays: stimulating engagement to increase revenues. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 30, 2093–2111. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0494

Umar, A., and Bahrun, R. (2017). The mediating relationship of customer satisfaction Between Brand Trust, brand social responsibility image with moderating role of switching cost. Adv. Sci. Lett. 23, 9020–9025. doi: 10.1166/asl.2017.10015

Vargo, S., and Lusch, R. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic. J. Mark. 68, 1–17. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

Verhoef, P., Reinartz, W. J., and Krafft, M. (2010). Customer engagement as a new perspective in customer management. J. Serv. Res. 13, 247–252. doi: 10.1177/1094670510375461

Verleye, K. (2015). The co-creation experience from the customer perspective: its measurement and determinants. J. Serv. Manag. 26, 321–342. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-09-2014-0254

Villagra, N., Monfort, A., and Sánchez Herrera, J. (2021). The mediating role of brand trust in the relationship between brand personality and brand loyalty. J. Consum. Behav. 20, 1153–1163. doi: 10.1002/cb.1922

Walter, N., Cleff, T., and Chu, G. (2013). Brand experience’s influence on customer satisfaction and loyalty: a mirage in marketing research? Int. J. Manag. Res. Bus. Strateg. 2, 130–144.

Wang, J., Wang, S., Xue, H., Wang, Y., and Li, J. (2018). Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. J. Clean. Prod. 181, 426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.250

Wasko, M. M., and Faraj, S. (2005). Why should i share? examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly. 29, 35–57. doi: 10.2307/25148667

Wu, J., Law, R., and Liu, J. (2018). Co-creating value with customers: a study of mobile hotel bookings in China. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 30, 2056–2074. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0476

Yeo, S. F., Tan, C. L., Lim, K. B., and Khoo, Y.-H. (2020). Product packaging: impact on customers’ purchase intention. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 21, 857–864. doi: 10.33736/ijbs.3298.2020

Yi, Y., and Gong, T. (2013). Customer value co-creation behavior: scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 66, 1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.026

Zhang, M., Guo, L., Hu, M., and Liu, W. (2016). Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: mediating effect of customer value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 37, 229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.04.010

Keywords: co-creation experience, brand evangelism, brand trust, brand passion, international tourists, theory of engagement

Citation: Nkoulou Mvondo GF, Jing F, Hussain K, Jin S and Raza MA (2022) Impact of International Tourists’ Co-creation Experience on Brand Trust, Brand Passion, and Brand Evangelism. Front. Psychol. 13:866362. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.866362

Edited by:

Umair Akram, Jiangsu University, ChinaReviewed by:

Sadaf Noor, Liaoning University, ChinaMuhammad Junaid, Lusíada University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2022 Nkoulou Mvondo, Jing, Hussain, Jin and Raza. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gustave Florentin Nkoulou Mvondo, ZmxvcmVudDkwQHlhaG9vLmZy

Gustave Florentin Nkoulou Mvondo

Gustave Florentin Nkoulou Mvondo Fengjie Jing1

Fengjie Jing1 Khalid Hussain

Khalid Hussain Muhammad Ali Raza

Muhammad Ali Raza