- 1Faculty of Management Sciences, Indus University, Karachi, Pakistan

- 2Faculty of Management Sciences, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology, Karachi, Pakistan

- 3Department of Financial and Administrative Sciences, Ranyah University College, Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia

- 4Institute of Business Administration, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan

- 5Azman Hashim International Business School, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Malaysia

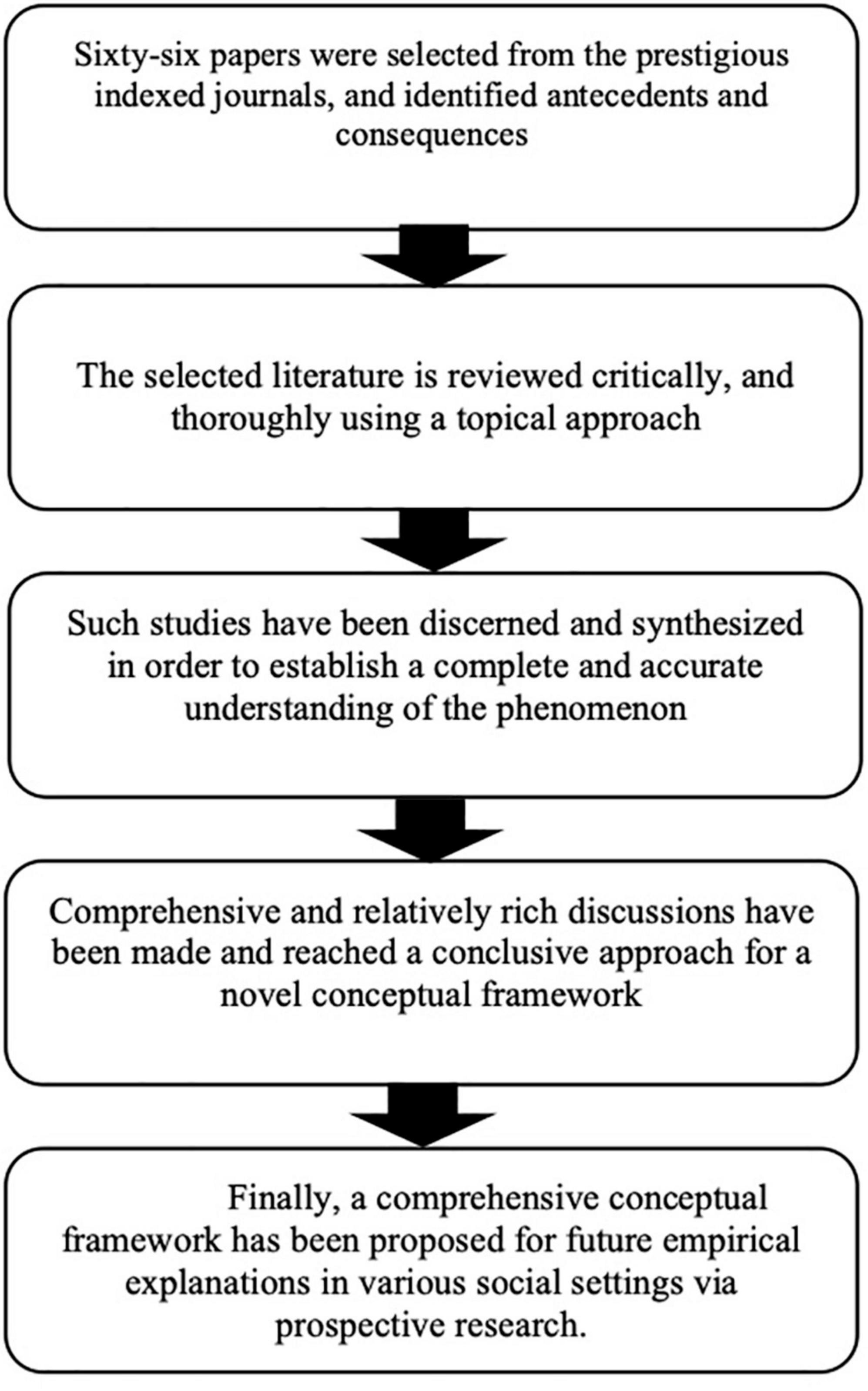

The focus of this paper is to develop a comprehensive conceptual framework for the relationship between internal employer brand image and talent retention. An extensive and semi-systematic literature review identified a number of antecedents and consequences that have been empirically tested in various cutting-edge research studies that were conducted around the world. The existing literature is reviewed using a topical approach, and 66 research studies, most recent from various repositories, were carefully chosen and reviewed based on the criteria. Such studies have been discerned and synthesized in order to establish a complete and accurate understanding of the phenomenon. Finally, a comprehensive and relatively rich conceptual framework has been proposed for future empirical explanations in various social settings via prospective research.

Introduction

A brand is a specific symbol, emblem, name, character, or insignia that represents, signifies, or characterizes a specific product (Kotler and Armstrong, 2017). Brand’s etymology may be traced back to the classic German language, where it means “fire.” The term “brand” means “burning” in ancient English. The brand image corresponds to the perceived quality, features, characteristics, qualities, benefits, and side effects in the minds of present or prospective customers (Keller and Kotler, 2015; Biswas and Suar, 2016). Employer brand image refers to the perceptual impression associated to an employer’s qualities and attributes in the minds of existing employees (internal customers) and potential employees (Barrow and Mosley, 2007; Priyadarshi, 2011). Dowling (1993) and Keller (1993) demonstrated that the employer image converts into the tangible benefits or the asset of the organization.

Employer branding has been introduced from the marketing discipline to the realm of human resource management (HRM) (Stokes, 2015; Stokes et al., 2016; Valle, 2016; Meyer and Xin, 2017; Theurer et al., 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019; Purusottama, 2019). Employer branding has two dimensions: the first is a source of attraction for new employees and the second is a source of motivation for incumbents to stay with the employer in the long run (Theurer et al., 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019). As a result, both prospective candidates and current employees are stakeholders in employer branding.

The difficulty and concern of a successful chief executive officer (CEO) is the recruitment and retention of the talented staff at all ranks (Meyer and Xin, 2017). This challenge is being met with novel techniques developed by combining HRM and marketing strategies. Presently, talent and talent segmentation are prominent HRM subjects that are, in fact, applications of marketing concepts, such as customer and customer segmentation. The top management has learned from business experience curves that long-term retention of talented workers is a basic necessity for developing a competitive advantage over others (Meyer and Xin, 2017).

External employer branding refers to the focus of employer branding strategies on prospective employees, while internal employer branding refers to the focus on incumbents. This research study adds to the theories of employer branding and work design. It is largely concerned with internal employer branding, which is divided into antecedents and repercussions. Antecedents are variables that contribute to the development of an employer’s brand image, whereas repercussions are created by the employer’s brand image. Both sides of the nexus are described in logical sequence in this article.

Antecedents of Internal Employer Branding

Chhabra and Sharma (2014) examined organizational culture, brand name, and compensation as antecedents of employer branding. Jain and Bhatt (2015) arrived at the conclusion that, in order to attract potential employees and retain current employees, it is critical to provide them with organizational support and infrastructure during their early days in the organization; additionally, organizational culture is equally important for achieving the best results from the previous two determinants. Organizational culture and organizational identity are two factors that contribute to an employer’s positive reputation and attraction (Jiang and Iles, 2011; Sageder et al., 2018). As per understanding of internal or external antecedents driven from the studies of Saraswathy and Balakrishnan (2017) and Davies et al. (2018), organizational culture and organizational identity are internal antecedents of employer brand image. In advanced economies, potential applicants have a wide selection of potential employers to choose from, so they make their decision to apply for a position extremely carefully, taking into account a variety of variables, such as trustworthiness (Beck and Kenning, 2015; Davies et al., 2018; Sageder et al., 2018), prestige (Davies et al., 2018), organizational culture, and organizational identity (Jiang and Iles, 2011; Sageder et al., 2018).

Employer branding encompasses organizational culture, interpersonal relations, systems, and organizational values (Singh and Rokade, 2014; Sharma and Prasad, 2018). A pleasant, hygienic, and conducive environment makes employees comfortable at work, which eventually may lead to their satisfaction (Singh and Rokade, 2014). Employees love to stay longer with employers who are providing work-life balance and competitive compensation (Singh and Rokade, 2014; Tanwar and Prasad, 2016). Carless and Imber (2007) and Carpentier et al. (2017) highlighted that the attractiveness of the employer is critical in catching the attention of prospective employees looking for work. Carpentier et al. (2017) have explored six factors that influence employer branding, which include pay, advancement, task diversity, atmosphere, meaningfulness, and work-life balance.

Immediate surroundings, such as work settings, people, furniture, equipment, building, and infrastructure etcetera are called working environments (Dessler, 2016). Jain and Bhatt (2015) have taken infrastructure solely as one determinant of employer branding. Employees prefer to work where people are collaborative, mutual respect is assured, the latest technology is available, work settings are safer and hygienic (Barrow and Mosley, 2007; Priyadarshi, 2011). Sharma and Prasad (2018) identified five constituents of employer branding, which include compensation and benefits (Chhabra and Sharma, 2014; Carpentier et al., 2017), work-life balance, work environment, brand strength, and organizational culture.

Carpentier et al. (2017) and Sharma and Prasad (2018) have taken work-life balance as another antecedent of employer brand image. Srivastava and Bhatnagar (2010), Jiang and Iles (2011), Chhabra and Sharma (2014), Beck and Kenning (2015), Jain and Bhatt (2015), Carpentier et al. (2017), Saraswathy and Balakrishnan (2017), Urbancova et al. (2017), Astrachan et al. (2018), Kaur et al. (2018), and Sageder et al. (2018) have taken work environment and organizational culture as predictors for employees’ attraction in the employer. Martin et al. (2016), Urde and Greyser (2016) and Astrachan et al. (2018) have taken brand strength as one of the predictors to employer brand image. Kaur et al. (2018) claimed that organizational culture is critical in attracting internal customers, namely, the personnel. Organizational culture represents the philosophy of the organization and the mindset of management (Srivastava and Bhatnagar, 2010). Truss et al. (2012) have endorsed that training and development is one important factor that creates a positive brand image of the employer.

Training and development are viewed from two perspectives: the employers and the employees. As a result, it must be used effectively because it benefits both sides. Employers want their employees to be updated, competitive, and ready to meet the threats and challenges; due to which, they provide training and manage development programs for their growth in knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs). Employees, on the other hand, seek training to supplement their KSAs and to participate in various development programs at work in order to raise their market value (Minchington, 2010; Truss et al., 2012; Dessler, 2016).

Earlier studies of Bhatnagar (2007) and Vaiman (2008) provide sound support to the arguments of Truss et al. (2012) and Dessler (2016) that training/learning and development programs and career planning are core factors that affect employer brand Image. Employees always appreciate opportunities to learn new things at work and overall people development; however, sincerity in building efficient career progression plans has been a tough demand by employees. As a result, these factors are vital in making employees happy at work, which ultimately generates and enhances a positive employer brand image. Astrachan et al. (2018) have taken four components of employer branding which include identity, image, reputation, and brand. Authors described that today’s employees, apart from good remuneration, look for their and their work’s identity in the organization. Astrachan et al. (2018) have taken the term image as the perceived image of the employer in the market that how people are mentally associated with the organization. In other words, how an employer wants to influence its offerings in the job market (Camara, 2011). Astrachan et al. (2018) have taken reputation from Urde and Greyser (2016) that people’s opinions, views, judgments, and mental association with the employer following employer’s actions in long term. Astrachan et al. (2018) have also taken the concept of the brand from Urde and Greyser (2016) that brand is a collection of value backed by promise and their assured delivery. Astrachan et al. (2018) concluded that these four components collectively form employer branding in the jobs market.

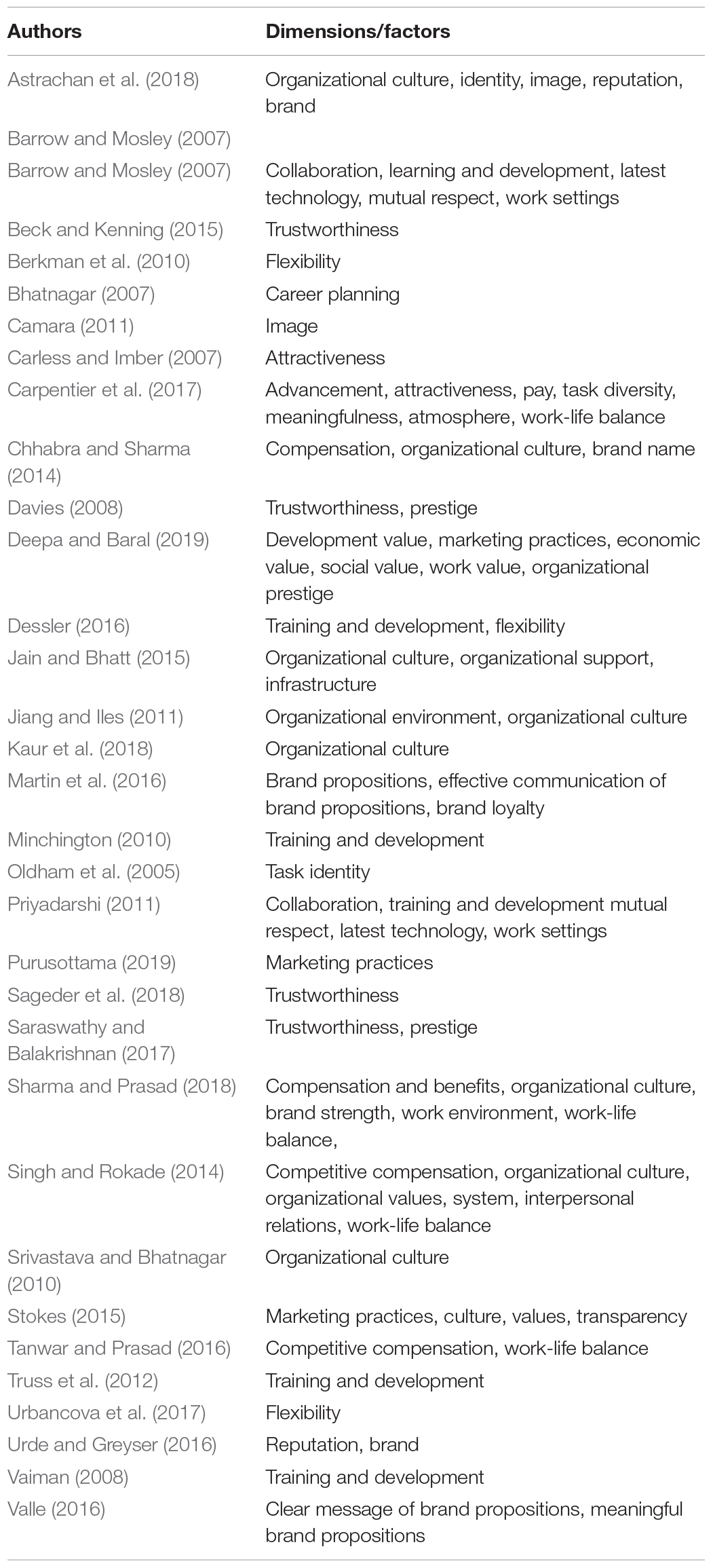

Hackman and Oldham (1975) and Oldham et al. (2005) have addressed their very own theory of work design, namely, the Job Characteristics Model, which is used to measure the attitude of employees toward the job. Authors have theorized and advocated that employees who are on the higher side of the Motivating Potential Score (MPS) have a positive attitude toward and image of their employer, which causes them to become engrossed in their work (job engagement), and they have a higher probability of performing well and remaining associated with their employer in the long run. Flexibility is an implicit agreement or willingness to change according to the situation or circumstances by either party, i.e., employer or employee (Berkman et al., 2010; Dessler, 2016; Urbancova et al., 2017). Flexibility includes options for working hours, such as morning, evening, or night shifts, driving to the office or working from a virtual office, formal or relaxed attire, and so on. Flexibility is essential for putting employees at comfort and allowing them to operate without stress (Dessler, 2016; Urbancova et al., 2017). The literature matrix containing a tabular summary of antecedents of employer branding is depicted in Table 1.

Consequences of Internal Employer Branding

Kahn (1990) theoretically explained the phenomenon of employees’ engagement at work as harnessing self, while performing the job emotionally, cognitively, and physically. The author developed three characteristics of employees’ engagement, i.e., meaningfulness, availability, and safety by which a specific employee establishes engagement with their work. Fredrickson (2000) provided another perspective on the phenomenon of employees’ engagement as positive emotions, which broaden the thought process and span of favorable actions at the workplace, which benefits employers and employees in return. The author asserted that such emotions help in building new ideas, reaching creative solutions, and turning colleagues into friends etcetera.

The emotional and cognitive harnessing asserted by Kahn (1990) has convergence with positive emotions asserted by Fredrickson (2000) because emotions either positive or negative are based upon one’s cognitive understanding of the particular situation, event, or individual. Therefore, the studies of Kahn (1990) and Fredrickson (2000) are sharing definitional commonalities. Leiter and Maslach (1998) and Maslach and Leiter (2008), considered employees’ engagement as opposite behavior to the employees’ burnout. They concluded in their seminal study that an employee cannot be engaged at work if he or she is suffering from predictors of burnout behavior, such as stress, a non-conducive atmosphere, toxic boss conduct, and unrealistic deadlines.

Contrary to the studies of Leiter and Maslach (1998), another study by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004) refers to engagement as an attitude, but not behavior. Schaufeli and Bakker (2004) asserted that employees’ engagement is feelings of being positive and having work-oriented mindset, which is backed by absorption, dedication, and vigor in wholesome. The authors defined absorption as a state of intense attention during work in which time moves too rapidly and it is impossible to disconnect from the task at hand. Dedication is defined as feelings of being excited for, inspired by, honored to be at work, and viewing work as a challenge that helps employees stay happy and optimistic about their work. Vigor is defined as the height of an employee’s energy level and the flexibility that an individual exhibits at work, which assists employees in dealing with weariness at work.

Lockwood (2006) asserted that post-industrial progress, where work nature is intangible and performance is based on originality, efficiency, and flexibility, demands high employees’ engagement, which is one of the main challenges that employers are facing. Bhatnagar (2007) reflected that providing employees with engrossing and conducive environment leads to earning two-pronged benefits, i.e., enhanced brand equity of employer and retention in longer run. Bhatnagar (2007) reflected that employees’ engagement has been the second most important HRM issue, while retention of talented employees being first, for the last 10 years. In this context, Bhatnagar (2007) asserted that effective managerial practices demonstrate the employer’s concern toward human capital, which causes employees to be engaged and decrease in the rate of turnover. Eventually, such managerial concern and employees’ response create a significant impact on individual performance and the overall performance of the organization.

Warr and Inceoglu (2012) explained the relationship of personality traits of the big five model, i.e., extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience with the construct of employees’ engagement. Authors found the relationship of employees’ engagement in the short run as a function of the long-term big five traits explicitly emotional stability and two sub-factors socially proactive and achievement-oriented from two core factors, extroversion and conscientiousness, respectively. Vorina et al. (2017) have explained employees’ engagement as behavior, but not attitude in a broader spectrum while testing the relationship of its main antecedents and the impact of employees’ engagement on different work-related behaviors. Vorina et al. (2017) have explained the significant relationship of employees’ engagement with its four antecedents, which include credible leadership, supportive co-workers, job and career satisfaction, and high-performing organizations. Vorina et al. (2017) have also testified the relationship of employees’ engagement with its descendent behaviors and outcomes, which include satisfied and loyal customers, productive and profitable organizations, high-performing workforce, and committed employees.

The study of Meere (as cited in Wang, 2016) concluded that employees’ engagement has at least three stages, i.e., actively disengaged, not engaged, and engaged. Wang (2016) summarized “actively disengaged” employees who are not satisfied, involved in complaints, and they spread negative energy among colleagues; “not Engaged” employees who lack enthusiasm and positive energy, and working for serving the time only; “engaged” employees who are profoundly connected, dedicated, and passionate at the workplace. Okolo et al. (2018) and Kamel (2019) have taken the job characteristics model (Hackman and Oldham, 1975) into account to explain its relationship with employees’ engagement and talent retention. It has been stated that organizations that prioritize talent acquisition and retention create appealing and stimulating work designs and conducive work environments for their employees. Akhir et al. (2018) have explained the relationship of employees’ engagement with its leading consequence, i.e., turnover intention. Turnover intention is viewed as the inverse of employee retention, which makes sense given that leaving or planning to leave the organization is a projected attitude of incumbents, who would behave differently if employee retention is viewed as a result of employee engagement.

Perceived corporate social responsibility (Perceived CSR) also causes employees’ engagement with the mediation effect of employees’ empathy (Tian and Robertson, 2019). Madu et al. (2019) have taken aesthetic workplace as a cause of employees’ engagement. The aesthetic workplace, on the other hand, refers to an organization that is highly beautiful in its physical structure, ambience, and internal appeal, all of which are sub-components of the organizational environment (Carpentier et al., 2017; Astrachan et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2018). Dut̨u and Butucescu (2019) have taken employees’ engagement as a consequence caused by transformational leadership, since such leaders possess the phenomenal power to motivate, delight, and engage the sub-ordinates in a way that become heavily engaged with the firm and perform far more than the expected targets. Conclusively, meaningfulness, availability, and safety (Kahn, 1990), absorption, dedication, and vigor (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004), and emotional stability, socially proactive, achievement-oriented (Inceoglu and Warr, 2012) are dimensions to measure the employees’ engagement; actively disengaged, not engaged, and engaged (Wang, 2016) are types of employees’ engagement, while, positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2000), autonomy, participative decision-making, and mutual trust (Lockwood, 2006), conducive environment (Bhatnagar, 2007), credible leadership, supportive co-workers, job and career satisfaction, and high-performing organizations (Vorina et al., 2017) are antecedents or predictors of employees’ engagement.

The phenomenon of talent retention is associated with employees’ employment tenure with a particular employer (Dessler, 2016). After an employee is hired, the next milestone is to utilize their talent in the long run. There are at least two reasons behind this interest. The first is that replacing an employee with a new hire is always more expensive than retaining an existing employee (Dessler, 2016). Second, a high frequency of recruiting people for a certain position entails a variety of non-monetary costs, such as orientation, training, and development, and normal performance during the initial months of hire, the possibility of theft of business or organizational secrets by employees who have left the workplace, and so forth.

Arasanmi and Krishna (2019) have explained the relationship of employer branding with employees’ retention. Authors have empirically proved the triangular relationship among perceived organizational support, organizational commitment, and employees’ intentions. West et al. (2019) have empirically explained the relationship of employees’ retention with one of the antecedents of employer branding, i.e., compensation and benefits through mediation effect of job satisfaction. Qureshi (2019) has taken high-performance work systems into account to empirically explain their relationship with employees’ commitment and employees’ retention at will. Empirical findings have shown that in the Gulf countries of the Middle East, organizations with high-performing work systems have more devoted employees who want to stay with the business in the long run. In the presence of a just and rigorous performance management culture, the most significant aspects of such high-performing work systems have been training, development, and compensation and benefits. Sukriket (2014) has testified and empirically proved the inverse relationship of employees’ recognition, communication, behavior of co-workers, benefits from employer, job conditions at the workplace, nature of work assigned, operating procedures for working, supervision by seniors, pay structure, and promotion in a career with turnover intentions.

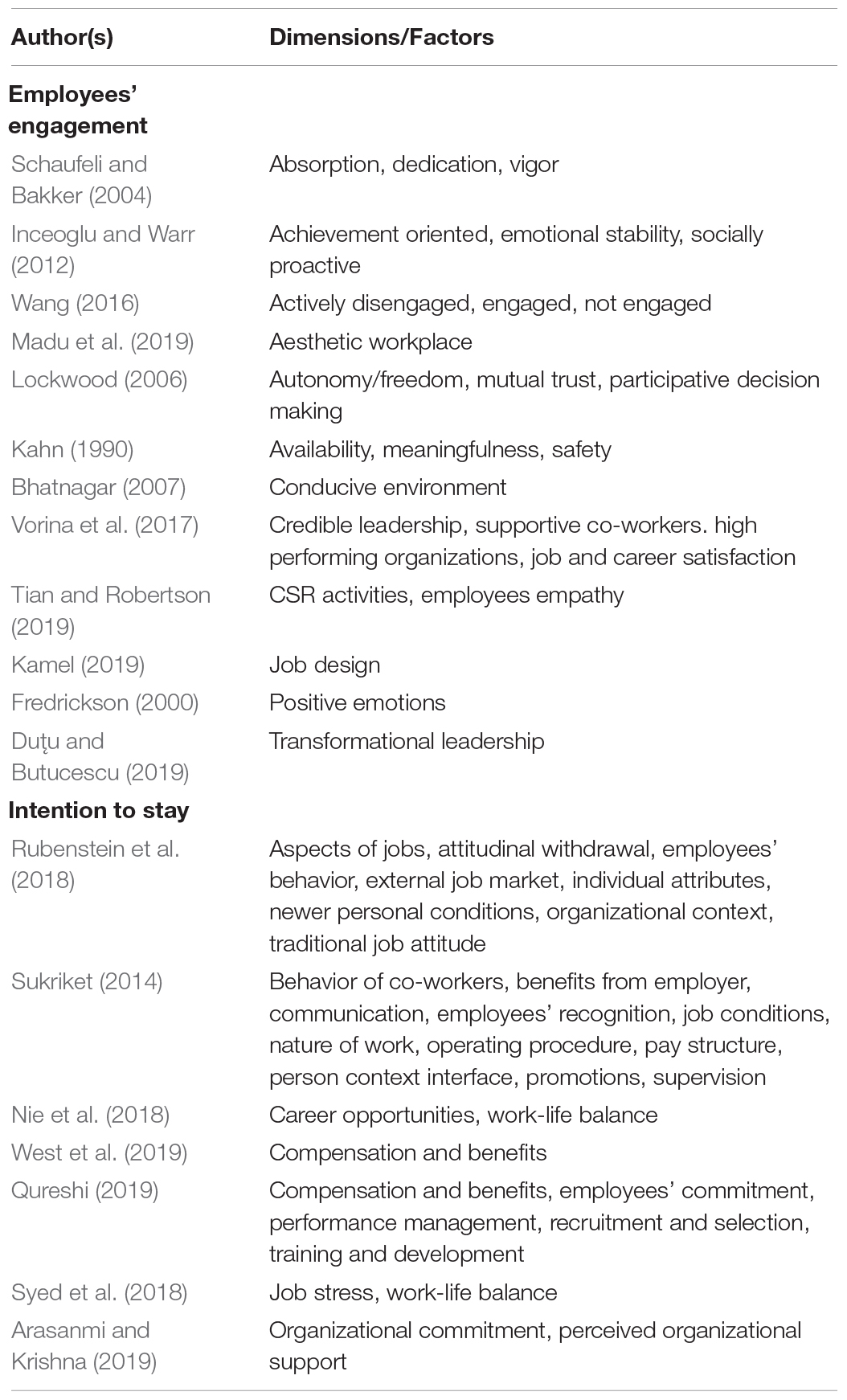

Rubenstein et al. (2018) have carried out a comprehensive meta-analysis of employees’ turnover intention and categorized nine antecedents that include individual attributes, aspects of job, traditional job attitudes, newer personal conditions, organizational context, person-context interface, external job market, attitudinal withdrawal, and employee behavior. Syed et al. (2018) have explained the relationship of turnover intentions with the work-life imbalance and job stresses. Nie et al. (2018) have explained the theoretical relationship of work-family integration and equal career opportunity with turnover intentions with moderating role of supervisor’s gender. Conclusively, the turnover intention is the reverse to the construct of intention to stay and antecedents of the earlier can be taken as antecedents of the latter in the inverse relationship. The literature matrix containing tabular summary of consequences of Employer Branding is demonstrated in Table 2:

Materials and Methods

We fetched literature pertaining to core and sub-themes of Employer Branding from the digital library of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan. We accessed more than 200 research articles out of which 66 articles qualified the criteria of high recency and relevance. The topical approach is opted for searching the articles from repositories to conduct the semi-systematic literature review. Selected research publications are most recent except some classical state-of-the-art articles and examined in connection to the relevant themes with the goal of designing a robust conceptual framework. Review-driven findings are segregated based on their themes and sub-themes; followed by clubbing of related themes to form more abstract themes for increasing parsimony of conceptual framework. The semi-systematic literature review overcomes the hurdles of a systematic review and synthesizes the vital notions, theories, frameworks, and developments (Snyder, 2019; Bhat et al., 2020). An extensive literature analysis identified a nexus of Employer Branding, which is difficult to understand without its deconstruction; thus, the following paragraphs discuss relationship-based disintegration, which aids in understanding the framework’s overall image. Positive and negative notions represent the right and inverse relationship between two variables, respectively.

Literature Gap

The phenomenon of employer branding (Barrow and Mosley, 2007; Priyadarshi, 2011; Carpentier et al., 2017; Saraswathy and Balakrishnan, 2017; Urbancova et al., 2017; Astrachan et al., 2018; Kaur et al., 2018; Sageder et al., 2018; Sharma and Prasad, 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019) along with its antecedents and its consequence employees’ engagement (Kahn, 1990; Schaufeli et al., 2002; Inceoglu and Warr, 2012; Warr and Inceoglu, 2012; Wang, 2016; Vorina et al., 2017), talent retention at will (Arasanmi and Krishna, 2019; Qureshi, 2019; West et al., 2019) has been explored and explained through different research studies but intensive literature review lacks empirical shreds of evidence of theoretical relationship among all three constructs, i.e., employer branding, employee’s engagement, and talent retention in one particular social setting, which means theoretical gap exists in the literature.

Job design (Okolo et al., 2018; Kamel, 2019) has been explained as an antecedent of employees’ engagement and talent retention, but literature review lacks sound evidence where it has been considered as an antecedent of employer brand image and having mediation effect on it, i.e., employer brand image with two consequences, e.g., employees’ engagement and talent retention. Therefore, a theoretical gap exists in the extant literature.

Since the emergence of cultural dimensions back in 1981, Hofstede (2011) explored nine cultural dimensions on the basis of which one social setting is different from others. Without testing in the specific social setting, research studies and phenomena testified in other social settings might not bring the same results. The triangular relationship of employer branding, employees’ engagement, and employees’ talent retention needs to be testified in different social settings before generalizing and practicing.

Selection of Research Papers and Flow of Ideas

The papers were selected from reputed indexing, such as Web of Science, Scopus, ABDC, and ABS, on the basis of different dimensions or factors which are demonstrated in Table 1 (antecedents of employer branding) and Table 2 (consequences of employer branding). The details of selected research articles are also provided in Tables 1, 2. The flow of ideas for the construction of a novel conceptual framework as cascaded in Figure 1.

Discussion for Final Conceptual Framework

The Proposed Framework

The semi-systematic literature review is undertaken using a topical approach, and 66 research publications most recent from various repositories have been selected and examined in connection to the relevant variables with the goal of designing a conceptual framework based on theoretical underpinning. The semi-systematic literature review overcomes the hurdles of a systematic review and synthesizes the vital notions, theories, frameworks, and developments (Snyder, 2019; Bhat et al., 2020). An extensive literature analysis identified a nexus of Employer Branding, which is difficult to understand without its deconstruction; thus, the following paragraphs discuss relationship-based disintegration, which aids in understanding the framework’s overall image.

Competitive Compensation

Perceived competitive compensation has been of high relevance with internal employer branding as it is explained in many recent past research studies (e.g., Chhabra and Sharma, 2014; Singh and Rokade, 2014; Sukriket, 2014; Tanwar and Prasad, 2016; Carpentier et al., 2017; Sharma and Prasad, 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019). It is quite likely that in a particular social situation, employees who receive pay from their employers that is quite competitive to market rates have identified their employers with a positive brand image and are more likely to stay linked with the business in the long run. It has been described as the top or the second most important component with a high impact on employer branding and employee retention in previous studies noted above. As a result, this concept has been adopted as one of the primary antecedents of employer branding.

Organizational Environment

The perceived organizational environment has been taken into account and explained in recent past research studies (e.g., Jiang and Iles, 2011; Priyadarshi, 2011; Chhabra and Sharma, 2014; Singh and Rokade, 2014; Beck and Kenning, 2015; Jain and Bhatt, 2015; Stokes, 2015; Tanwar and Prasad, 2016; Carpentier et al., 2017; Saraswathy and Balakrishnan, 2017; Urbancova et al., 2017; Astrachan et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2018; Kaur et al., 2018; Sageder et al., 2018; Sharma and Prasad, 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019) as an antecedent of internal employer branding. The organizational environment itself is an abstract concept, which is explained through culture, work setting, interpersonal relationships, organizational justice, and work-life balance etcetera. Employees in a particular social context who have a suitable work environment, rich culture, good interpersonal interactions, fairness and justice, and a healthy work-life balance are more likely to have a positive picture of the employer brand and to stay linked with the employer in the long run. As a result, this concept has been adopted as one of the primary antecedents of employer branding.

Career Progression

Perceived career progression has been taken into account and explained in recent past research studies (e.g., Minchington, 2010; Priyadarshi, 2011; Truss et al., 2012; Davies et al., 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019) as an antecedent of internal employer branding. Career progression is explained through learning opportunities, training investment orientation, career growth opportunities, succession planning, and so on. Employees who have opportunities to learn, managers with a positive attitude toward training and development, organizations concerned with employees’ career development, and organizations that practice succession planning at work are more likely to have a positive image of the employer brand and to remain associated with the employer in the long run. As a result, this concept has been adopted as one of the primary antecedents of employer branding.

Employer Prestige

Perceived Reputation of Employer in the market has been taken into account and explained in recent past research studies (e.g., Minchington, 2010; Priyadarshi, 2011; Truss et al., 2012; Davies et al., 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019; Lu et al., 2020) as an antecedent of internal employer branding. The employer’s reputation in the market is explained by the image of the employer viewed by people outside the firm, excellence in market competition, perceived CSR, and the like. It is highly anticipated that in a given social setting, employees who perceive that their employer has a prestigious image among people outside the organization, have established healthy competition with excellence among competitors and have engaged in effective CSR toward society, are more likely to have a rich image of the employer brand and are more likely to remain associated with employer in the long run. As a result, this concept has been adopted as one of the primary antecedents of employer branding.

Job Design

Job design has been taken into account and explained in research studies (e.g., Okolo et al., 2018; Kamel, 2019) as a core antecedent of employees’ engagement. Job design is explained through skills variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback of job characteristics model (Hackman and Oldham, 1975) that is perceived on the basis of experiences of the incumbents. An employee with a better perceived work design is more likely to become involved with the task. Despite having motivational features, the literature lacks evidence that work design is a precursor to employer branding. As a result, this concept has been adopted as an antecedent for both employee engagement and employer branding (Ashraf et al., 2018).

Employees’ Engagement

Employees’ engagement has been taken into account and explained in recent past research studies (e.g., Inceoglu and Warr, 2012; Wang, 2016; Vorina et al., 2017; Akhir et al., 2018; Dut̨u and Butucescu, 2019; Madu et al., 2019; Tian and Robertson, 2019) as an antecedent and consequence of different constructs. According to the literature review, most of the time, employee engagement is viewed as a result of various positive antecedents, such as high-performing organizations, supportive work colleagues, job satisfaction, career growth opportunities, socially proactive workplace, more conducive environment, and so on. Critical synthesis aids comprehension of the fact that the aforementioned antecedents of employee engagement are essentially antecedents and factors of employer branding; hence, employer branding is one of the main antecedents of employees’ engagement. Employee engagement, on the other hand, has been identified as a predictor of a variety of outcomes, such as perceived performance, employee retention, and employee turnover intention. As a result, it has been discovered that the construct of employees’ engagement is both an antecedent and a consequence of different constructs; in fact, it serves as a mediator between its antecedents and consequences.

Talent Retention

Recent studies have taken into account and explained talent retention (Arasanmi and Krishna, 2019; Qureshi, 2019; West et al., 2019), employer brand image, and employee engagement as a result of employer branding strategies. On the other hand, numerous researchers have explained its counterpart construct, turnover intention (e.g., Sukriket, 2014; Nie et al., 2018; Rubenstein et al., 2018; Syed et al., 2018). As a result of various constructs that emerged during the literature review, such as recognition of employees’ work, communication with colleagues, colleague behavior, job conditions, nature of the work, supervision, pay structure, promotion-related policies and practices, individual attributes of employees, work-life balance, and economic situation, and so forth. These indications can also be used to predict talent retention at will, although the link between said indicators and talent retention will be inverse, as it is with turnover intentions. Critical syntheses of these precursors result in similarities to antecedents of employer branding. Gilmore (2017) developed the process of antecedents leading to behavior and then to outcomes employees’ engagement is taken into account in this research study as a behavior with several antecedents that comprise the construct of employer branding; once employees is engaged with their work, they will have a consequence in the form of willful employees’ retention.

Final Conceptual Framework

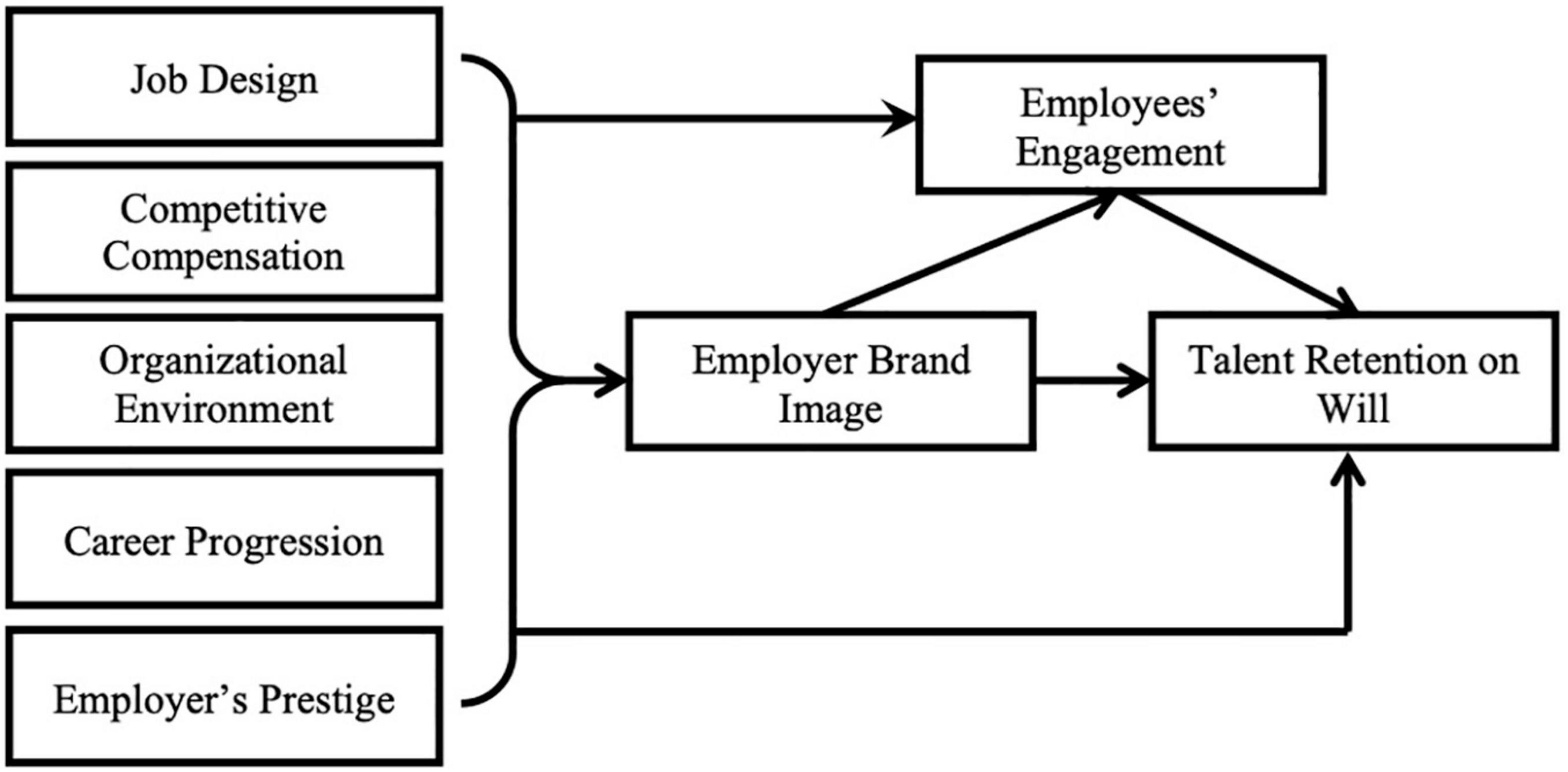

We postulate that the antecedent of employer branding, such as job design, competitive compensation, organizational environment, career progression, and employers’ prestige, causes to build employer brand image that eventually causes employees engagement and talent retention. The construct of employer brand image and employee engagement plays mediating role between antecedents of employer branding and talent retention. In the proposed conceptual framework, all relationships are rightly/positively causing their effects. It addresses novelty through the addition of job design as the antecedent of employer branding and the double mediation through employer brand image and employees’ engagement. On the basis of reviewed literature of employer brand image, employees’ engagement, and talent retention, it is conceptualized that competitive compensation (Chhabra and Sharma, 2014; Carpentier et al., 2017; Sharma and Prasad, 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019), organizational environment (Jain and Bhatt, 2015; Stokes, 2015; Saraswathy and Balakrishnan, 2017; Urbancova et al., 2017; Kaur et al., 2018; Sageder et al., 2018; Sharma and Prasad, 2018; Deepa and Baral, 2019), career progression (Barrow and Mosley, 2007; Vaiman, 2008; Minchington, 2010; Priyadarshi, 2011; Truss et al., 2012; Dessler, 2016), organization’s prestige (Urde and Greyser, 2016; Carpentier et al., 2017; Saraswathy and Balakrishnan, 2017; Sharma and Prasad, 2018), and job design (Carpentier et al., 2017) have theoretical relationship with attitudinal variable employer brand image, which is theoretically linked with behavioral variable, i.e., mediator between attitude and consequence employees’ engagement (Kahn, 1990; Schaufeli et al., 2002; Inceoglu and Warr, 2012; Wang, 2016; Vorina et al., 2017), which has further theoretical relationship with behavioral consequences, talent retention at will (Arasanmi and Krishna, 2019; Qureshi, 2019; West et al., 2019). Hence, the final conceptual framework is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The final conceptual framework (Minchington, 2010; Jiang and Iles, 2011; Priyadarshi, 2011; Inceoglu and Warr, 2012; Truss et al., 2012; Chhabra and Sharma, 2014; Singh and Rokade, 2014; Sukriket, 2014; Beck and Kenning, 2015; Jain and Bhatt, 2015; Stokes, 2015; Tanwar and Prasad, 2016; Wang, 2016; Carpentier et al., 2017; Saraswathy and Balakrishnan, 2017; Urbancova et al., 2017; Vorina et al., 2017; Akhir et al., 2018; Astrachan et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2018; Kaur et al., 2018; Nie et al., 2018; Okolo et al., 2018; Rubenstein et al., 2018; Sageder et al., 2018; Sharma and Prasad, 2018; Syed et al., 2018; Arasanmi and Krishna, 2019; Deepa and Baral, 2019; Dut̨u and Butucescu, 2019; Kamel, 2019; Madu et al., 2019; Qureshi, 2019; Tian and Robertson, 2019; West et al., 2019).

Conclusion

The objective of the undertaken study was to develop an inclusive conceptual framework for the relationship between internal employer brand image and talent retention. For this purpose, authors have carried out an extensive and semi-systematic literature review and identified a number of antecedents and consequences that have been empirically established in numerous leading-edge research studies carried out around the globe at different time horizons in different prestigious indexing journals. The existing literature is reviewed using a topical approach, and 66 research studies, most recent from various repositories, were carefully chosen and reviewed based on the criteria. Such studies have been discerned and synthesized in order to establish a complete and accurate understanding of the phenomenon. Finally, a comprehensive and relatively rich conceptual framework has been proposed for future empirical explanations in various social settings via prospective research based on competitive compensation, organizational environment, career progression, job design, employer’s prestigious, internal employer brand image, employee’s engagement, and talent retention. During the research various constructs that arose through the literature review are acknowledgment of employees’ work, interaction with colleagues, colleague behavior, job environments, nature of the work, guidance, pay structure, promotion-related strategies and exercises, individual characteristics of employees, work-life balance, and economic condition, and so forth. These clues can also be used to forecast talent retention at will, though the link between said markers and talent retention will be contrary, as it is with turnover intentions. Analytical syntheses of these predecessors result in resemblances to antecedents of employer branding. As preceding literature established the process of antecedents leading to behavior and then to consequences employees’ engagement is taken into account in this research study as a behavior with several precursors that comprise the construct of employer branding; once employees are engrossed with their work, they will have a consequence in the form of willful employees’ retention. The suggested conceptual framework offers a roadmap for HR managers, HR consultants, and talent hunters and retainers to understand the workable link of employees’ positive attitude, its causes and effects on work and ultimately on the workplace. HR practitioners may add value to HR policies pertaining to hiring and retaining the talent. This may also help HR practitioners to confirm exemplary shifts from conventional human resource to the resource-based contemporary practices of human resource.

Theoretical and Practical Contributions

The proposed conceptual framework adds theoretical value to the discourse of organizational behavior, HRM, and talent management. It offers a unique and novel addition of Job Design in the nexus between antecedents and consequences of employer branding. Moreover, the double mediating role of employer brand image and employees’ engagement adds theoretical value in the realm of knowledge. The proposed conceptual framework provides a roadmap for HR generalists, line managers, HR consultants, and talent hunters and retainers to understand the workable link of employees’ positive attitude, its causes, and effects on work and eventually on workplace. Practitioners may add value in HR policies pertaining to hiring and retaining the talent. This may also help HR practitioners to ensure the paradigmatic shift from traditional HR to the resource-based modern practices of HR.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

This probe appears to be limited in its scope of designing a conceptual framework based on literature gap and theoretical backdrop. Following theoretical underpinning particularly employer branding theory and theory of work design, the proposed conceptual framework merits empirical testing and explanation in different social settings in order to establish and increase its generalizability and to confirm or refute the theoretical relationship of the concepts. This framework contributes to theory and has implications for empirical research, theory, and practice, especially in policy and strategy design.

Author Contributions

RA, JQ, and MA contributed to the conception and design of the study and wrote the first draft and sections. AH, VP, and NM revised and finalized the manuscript. AH and NM provided the scientific support during the research. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/338), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Faculty of Management, SZABIST, Karachi; and Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/338), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia for supporting this study.

References

Akhir, R. M., Ahmad, S. N., Ahmad, H., and Hashim, N. A. (2018). Staying or Leaving? The influence of employees’ engagement towards turnover decision among employees of a semi-government organization in Malaysia. Humanities 3, 55–62. doi: 10.20448/801.31.55.62

Arasanmi, C. N., and Krishna, A. (2019). Employer branding: perceived organizational support and employee retention–the mediating role of organizational commitment. Ind. Commerc. Train. 51, 174–183. doi: 10.1108/ICT-10-2018-0086

Ashraf, M., Vveinhardt, J., Ahmed, R. R., Štreimikienë, D., and Mangi, R. A. (2018). Exploring intervening influence of interactional justice between procedural justice and job performance: evidence from South Asian Countries. Amfiteatru Econ. 20, 169–184. doi: 10.24818/EA/2018/47/169

Astrachan, C. B., Botero, I., Astrachan, J. H., and Prügl, R. (2018). Branding the family firm: a review, integrative framework proposal, and research agenda. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 9, 3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2018.01.002

Barrow, S., and Mosley, R. (2007). The Employer Brand, Bringing the Best of Brand Management to People at Work. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Beck, S., and Kenning, P. (2015). The influence of retailers’ family firm image on new product acceptance: an empirical investigation in the German FMCG market. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 43, 1126–1143. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-06-2014-0079

Berkman, L. F., Buxton, O., Ertel, K., and Okechukwu, C. (2010). Managers’ practices related to work-family balance predict employee cardiovascular risk and sleep duration in extended care settings. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 15, 316–329. doi: 10.1037/a0019721

Bhat, M., Shumaiev, K., Hohenstein, U., Biesdorf, A., and Matthes, F. (2020). “The evolution of architectural decision making as a key focus area of software architecture research: a semi-systematic literature study,” in Proceedings of 2020 IEEE International Conference on Software Architecture (ICSA), (Piscataway, NJ: IEEE), 69–80. doi: 10.1109/ICSA47634.2020.00015

Bhatnagar, J. (2007). Talent management strategy of employee engagement in Indian ITES employees. Employee Relat. 29, 640–663. doi: 10.1108/01425450710826122

Biswas, M. K., and Suar, D. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of employer branding. J. Bus. Ethics 136, 57–72. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2502-3

Camara, N. Z. (2011). “Identity, image and reputation,” in Reputation Management, eds S. Helm, K. Liehr-Gobbers, and C. Storck (Berlin: Springer-Verlag), 47–58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19266-1_6

Carless, S., and Imber, A. (2007). Job and organizational characteristics: a construct evaluation of applicaton perceptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 67, 328–341. doi: 10.1177/0013164406292040

Carpentier, M. V., Stockman, S., Schollaert, E., Van Theemsche, B., and Jacobs, G. (2017). Recruiting nurses through social media: effects on employer brand and attractiveness. J. Adv. Nurs. 73, 2696–2708. doi: 10.1111/jan.13336

Chhabra, N., and Sharma, S. (2014). Employer branding: strategy for improving employer attractiveness. Int. J. Organ. Analysis 22, 48–60. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-09-2011-0513

Davies, G. (2008). Employer branding and its influence on managers. Eur. J. Market. 42, 667–681. doi: 10.1108/03090560810862570

Davies, G., Mete, M., and Whelan, S. (2018). When employer brand image aids employee satisfaction and engagement. J. Organ. Effect. People Perform. 5, 64–80. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-03-2017-0028

Deepa, R., and Baral, R. (2019). Importance-performance analysis as a tool to guide employer branding strategies in the IT-BPM industry. J. Organ. Effect. People Perform. 6, 77–95. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-04-2018-0024

Dowling, G. R. (1993). Developing your company image into a corporate asset. Long Range Planning 26, 101–109.

Dut̨u, R., and Butucescu, A. (2019). On the link between transformational leadership and employees’ work engagement: the role of psychological empowerment. Psihol. Resurselor Umane 17, 42–73. doi: 10.24837/pru.v17i2.291

Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Why positive emotions matter in organizations: lessons from the broaden-and-build model. Psychol. Manag. J. 4, 131–142. doi: 10.1037/h0095887

Gilmore, H. (2017). ABC’s of Behavior (Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence). Available online at: https://pro.psychcentral.com/child-therapist/2017/07/abcs-of-behavior-antecedent-behavior-consequence/ (accessed September 5, 2021).

Hackman, J. R., and Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 60, 159–170. doi: 10.1037/h0076546

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2:1. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Inceoglu, I., and Warr, P. (2012). Personality and job engagement. J. Pers. Psychol. 10, 177–181. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000045

Jain, N., and Bhatt, P. (2015). Employment preferences of job applicants: unfolding employer branding determinants. J. Manag. Dev. 34, 634–652. doi: 10.1108/JMD-09-2013-0106

Jiang, T. T., and Iles, P. (2011). Employer Brand Equity, organizational attractiveness and talent management in the Zhejiang private sector of China. J. Technol. Manag. 6, 97–111. doi: 10.1108/17468771111105686

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.5465/256287

Kamel, N. (2019). “Implementing talent management and its effect on employee engagement and organizational performance,” in Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, (Abu Dhabi: Society of Petroleum Engineers). doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0566-5

Kaur, M., Oney, K., Chadbourne, J., Bookman, K., and Beckman, B. (2018). An Analysis of the Factors which Effectively Attract College Graduates. Available online at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/566 (accessed March 15, 2021).

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Market. 57, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/002224299305700101

Keller, K. L., and Kotler, P. (2015). “Holistic marketing: a broad, integrated perspective to marketing management,” in Does Marketing Need Reform?: Fresh Perspectives on the Future, eds J. Sheth and R. Sisodia (Abingdon: Routledge), 308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.034

Kotler, P., and Armstrong, G. (2017). Principles of Marketing: Global Edition. London: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Leiter, M. P., and Maslach, C. (1998). “Burnout,” in Encyclopedia of Mental Health, Vol. 1, ed. H. S. Friedman (New York, NY: Academic Press).

Lockwood, N. R. (2006). Talent Management: Driver for Organizational Success. SHRM Research Quarterly. Available online at: https://docplayer.net/786555-Talent-management-driver-for-organizational-success-by-nancy-r-lockwood-sphr-gphr-m-a-manager-hr-content-program.html (accessed March 7, 2022).

Lu, J., Ren, L., Zhang, C., Rong, D., Ahmed, R. R., and Streimikis, J. (2020). Modified carroll’s pyramid of corporate social responsibility to enhance organizational performance of SMEs industry. J. Clean. Product. 271:122456. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122456

Madu, G. N., Oparanma, A. O., and Gabriel, J. M. (2019). Workplace aesthetics and employees engagement of government tertiary Institutions In Rivers State, Nigeria. Noble Int. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 3, 95–102.

Martin, G., Gollan, P., and Grigg, K. (2016). “Managing corporate reputations, strategic human resource management and negative capabilities,” in Corporate Reputations: Managing Opportunities and Threats, eds R. J. Burke, G. Martin, and C. Cooper (London: Routledge).

Maslach, C., and Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 93:498. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

Meyer, K. E., and Xin, K. R. (2017). Managing talent in emerging economy multinationals: integrating strategic management and human resource management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 29, 1827–1855. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1336362

Minchington, B. (2010). Employer Brand Leadership - A Global Perspective. Torrensville: Collective Learning Australia.

Nie, D., Lämsä, A. M., and Pučëtaitë, R. (2018). Effects of responsible human resource management practices on female employees’ turnover intentions. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 27, 29–41. doi: 10.1111/beer.12165

Okolo, D., Kamarudin, S., and Ahmad, U. N. (2018). An exploration of the relationship between technostress, employee engagement and job design from the nigerian banking employee’s perspective. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 6, 511–531. doi: 10.25019/MDKE/6.4.01

Oldham, G. R., Hackman, J. R., Smith, K. G., and Hitt, M. A. (2005). “How job characteristics theory happened,” in The Oxford Handbook of Management Theory: The Process of Theory Development, eds K. G. Smith and M. A. Hitt (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 151–170.

Priyadarshi, P. (2011). Employer brand image as predictor of employee satisfaction, affective commitment & turnover. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 46, 510–522.

Purusottama, A. (2019). The dimension of employer branding: attracting talented employees to leverage organizational competitiveness. J. Apl. Manaj. 17, 118–126. doi: 10.21776/ub.jam.2019.017.01.13

Qureshi, T. M. (2019). Talent retention using high performance work systems. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 12, 10–19.

Rubenstein, A. L., Eberly, M. B., Lee, T. W., and Mitchell, T. R. (2018). Surveying the forest: a meta-analysis, moderator investigation, and future-oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Pers. Psychol. 71, 23–65. doi: 10.1111/peps.12226

Sageder, M., Mitter, C., and Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B. (2018). Image and reputation of family firms: a systematic literature review of the state of research. Rev. Manag. Sci. 12, 335–377. doi: 10.1007/s11846-016-0216-x

Saraswathy, R., and Balakrishnan, J. (2017). Facets of talent retention: role of employee and employer branding as catalysts. Int. J. Bus. Forecast. Market. Intellig. 3, 407–432. doi: 10.1504/ijbfmi.2017.10008566

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 25, 293–315. doi: 10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happ. Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Sharma, R., and Prasad, A. (2018). “Employer brand and its external perspective,” in Flexible Strategies in VUCA Markets, eds S. Dhir Sushil (Singapore: Springer), 251–268. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8926-8_19

Singh, M., and Rokade, V. (2014). Employer branding: a strategic dimension for employee retention. J. Market. Consum. Res. 5, 1–6.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Srivastava, P., and Bhatnagar, J. (2010). Employer brand for talent acquisition: an exploration towards its measurement. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 14, 25–34. doi: 10.1177/097226291001400103

Stokes, C. (2015). Employer Branding: Why It’s Time Marketing, Execs, and HR Worked Together. Available online at: https://venturebeat.com/2015/11/01/employer-branding-why-its-time-marketing-execs-and-hr-worked-together/ (accessed May 15, 2020).

Stokes, P., Liu, Y., Smith, S., Leidner, S., Moore, N., and Rowland, C.-G. (2016). Managing talent across advanced and emerging economies: HR issues and challenges in a Sino-German strategic collaboration. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 27, 2310–2328. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2015.1074090

Sukriket, P. (2014). The relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention of Thai software programmers in Bangkok, Thailand. AU J. Manag. 12, 42–52.

Syed, A., Ahmad, M. B., Ali, H. F., Arif, M. M., and Gohar, A. (2018). Work-family conflict and turnover intentions: moderated mediation model. Hum. Resour. Res. 2, 95–106. doi: 10.5296/hrr.v2i1.13925

Tanwar, K., and Prasad, A. (2016). The effect of employer brand dimensions on job satisfaction:gender as a moderator. Manag. Decis. 54, 854–886. doi: 10.1108/MD-08-2015-0343

Theurer, C. P., Tumasjan, A., Welpe, I. M., and Lievens, F. (2018). Employer branding: a brand equity-based literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 20, 155–179. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12121

Tian, Q., and Robertson, J. L. (2019). How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. Ethics 155, 399–412. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3497-3

Urbancova, H., Richter, P., Kucirkova, L., and Jarkovska, M. (2017). Employer branding in the agricultural sector: making a company attractive for the potential employees. Agric. Econ. 63:5. doi: 10.17221/338/2015-agricecon

Urde, M., and Greyser, S. A. (2016). The corporate brand identity and reputation matrix –the case of the Nobel Prize. J. Brand Manag. 23, 89–117. doi: 10.1057/bm.2015.49

Vaiman, V. (2008). Retention management as a means of protecting tacit knowledge in organization: a conceptual framework for professional services firms. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Capital 5, 172–185. doi: 10.1504/IJLIC.2008.020150

Valle, P. L. (2016). HR and Marketing. Available online at: https://www.emotivebrand.com/hr-and-marketing (accessed July 25, 2021).

Vorina, A., Simonič, M., and Vlasova, M. (2017). An analysis of the relationship between job satisfaction and employee engagement. Econ. Themes 55, 243–262. doi: 10.1515/ethemes-2017-0014

Wang, J. (2016). The Antecedents of Employee Engagement: A Comparative Analysis between Finland and Asia. Helsinki: Aalto University.

Warr, P., and Inceoglu, I. (2012). Job engagement, job satisfaction, and contrasting associations with person–job fit. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 17:129. doi: 10.1037/a0026859

West, C., Ricks, J., Strachan, C., Iacono, J., and Shay, C. (2019). Factors that Influence Recruitment and Retention. Available online at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/980 (accessed March 19, 2021).

Keywords: employer brand image, employer branding, talent retention, internal branding, employees’ engagement, job design

Citation: Ahmed RR, Azam M, Qureshi JA, Hashem E AR, Parmar V and Md Salleh NZ (2022) The Relationship Between Internal Employer Branding and Talent Retention: A Theoretical Investigation for the Development of a Conceptual Framework. Front. Psychol. 13:859614. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.859614

Received: 21 January 2022; Accepted: 18 February 2022;

Published: 18 March 2022.

Edited by:

Tung-Ju Wu, Harbin Institute of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Priya Gunesh, University of Mauritius, MauritiusSiti Ngayesah Ab Hamid, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Ahmed, Azam, Qureshi, Hashem E, Parmar and Md Salleh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rizwan Raheem Ahmed, cml6d2FuLnJhaGVlbUBpbmR1cy5lZHUucGs=

Rizwan Raheem Ahmed

Rizwan Raheem Ahmed Muhammad Azam2

Muhammad Azam2 Alharthi Rami Hashem E

Alharthi Rami Hashem E