94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 20 May 2022

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.857585

This paper selected Vanke as the case to study the governance problems of Vanke and the protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders under the situation of equity disputes. At the same time, the study further explored the advantages and disadvantages of the dispersed ownership structure, the long-term impact on the company’s development and the choice of the involved corporate governance methods under the current Chinese capital market conditions. This paper adopted the event research method and selected the period from June 2015 to June 2017 (24 months) as the observation period to analyze the market performance impact of Vanke in the equity disputes. At the same time, this paper also measured Vanke’s individual stock rate of return (Rit) and market rate of return (Rmt), and calculated Vanke’s normal rate of return [E(Ri,t)], abnormal rate of return (ARi,t), and cumulative abnormal rate of return (CARi) during different event windows ([−3,10]). Vanke’s shareholding was too dispersed and the stock price had been sluggish for a long time, which had greatly reduced the acquisition difficulty and cost of Baoneng, thus triggering the “barbarian invasion” of Baoneng. In the struggle for control, whether it was Vanke’s anti-takeover measures or China Resources, Baoneng, and Evergrande’s competition for equity, their actions had harmed the interests of small and medium shareholders. The market supervision department was too lenient to supervise and punish the interests of small and medium shareholders, and opportunism made behaviors that infringe on the interests of others more reckless. However, small and medium shareholders cannot actively participate in the company’s management decision-making to safeguard their legitimate rights and interests, which intensifies the violations of all parties in the equity disputes, thus forming a vicious circle. Therefore, the protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders required the joint efforts and consciousness of regulators, small and medium shareholders, and acquirers.

China’s capital market has developed for more than 20 years and has achieved good results in financing and investment. However, when we talk about the stock market, we overemphasize its financing function, while ignoring that it is also a place for resource allocation and investment (Hayes and Lundholm, 1996; Hoberg and Phillips, 2016). Whether it was the stock market crash in 2007 or the market crash in 2015, the biggest losses were among small and medium shareholders (Bernard et al., 2006; Hughes et al., 2007; Armstrong et al., 2011; Dye and Hughes, 2018). If the stock market has become a place where “makers,” traders and listed companies wantonly plunder the interests of small and medium shareholders to satisfy their selfish desires, thus causing unbearable economic losses to small and medium shareholders, how can small and medium shareholders get involved in such a market? How can the capital market continue to move forward without the participation of small and medium shareholders (Christensen et al., 2010; Bertomeu et al., 2011; Corona and Lin, 2013; Caskey et al., 2015)? Therefore, from this perspective, protecting the interests of small and medium shareholders plays a vital role in the prosperity and development of China’s stock market.

The protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders involves the issue of principal–agent, and the principal–agent issue of management and shareholders has always been the basic problem in the corporate governance structure (Lemmon and Lins, 2003; Jessica, Weber, 2018). Among them, the ownership structure is one of the most core issues in corporate governance. An appropriate shareholding structure can not only help shareholders alleviate the “insider problem,” but also establish a monitoring mechanism for the behavior of large shareholders (Hodges et al., 2014). Seeking an equity structure suitable for corporate development should be the primary arrangement for corporate strategic development. Perfect corporate governance is not only an effective guarantee for modern companies to enhance their comprehensive competitiveness and performance capabilities, but also an important factor in attracting public investment investors (Robert, 1983). The combination of equity and governance can effectively help companies maximize corporate value and shareholder value.

The shareholding structure of Chinese listed companies is mostly highly concentrated, and the phenomenon of dominance caused by this is relatively common in China. Research showed that a highly concentrated ownership structure can solve the free-riding behavior of small and medium shareholders under a dispersed ownership structure. However, since other shareholders cannot effectively restrain large shareholders, absolute controlling shareholders can threaten the interests of small and medium shareholders by interfering with the management or colluding with them (Gebhardt et al., 2001; Francis et al., 2005; Fresard, 2010; Chen et al., 2014; Dhaliwal et al., 2016). A highly dispersed ownership structure can prevent the interests of major shareholders from infringing on the interests of small and medium shareholders, but it will also bring about the contradiction between the company’s public goods and the private costs of supervision.

This research can study the governance issues of Vanke and the protection of the interests of small and medium investors in the case of dispersed ownership structure. At the same time, this study can also further explore the advantages and disadvantages of dispersed ownership structure, the long-term impact on the company’s development, and the choice of corporate governance methods under the current Chinese capital market conditions. In this way, it can provide a reference for the corporate governance and equity setting of the same industry, as well as the protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders.

Most scholars generally believe that the centralized ownership structure can effectively prevent management from encroaching on shareholders for its own interests, and can reduce the occurrence of agency costs. Equity concentration will create a dominant phenomenon, which creates opportunities for large shareholders to hollow out small shareholders (Hail and Leuz, 2009; Christensen et al., 2010; Cheynel, 2013). The dispersed ownership structure can help to solve the problem that the company may have a dominant shareholder, but it may cause the insider control of the management.

The company’s shareholding structure is not in one-to-one correspondence with the internal and external mechanisms, that is, the dispersed shareholding does not mean that the external mechanism of the company must be good. Likewise, a high concentration of equity does not imply that internal mechanisms are functioning properly (Lang et al., 2004, 2012; Jeng and Pak, 2016). When both the internal mechanism and the external mechanism of the enterprise fail to deal with the principal–agent problem, the interest disputes between the large or small shareholder, the management, and the shareholder will exist within an enterprise at the same time.

Some scholars believe that equity concentration is not conducive to the development of corporate performance. After the share-trading reform, the higher the company’s tradable shares, the greater the improvement in company performance (Hail and Leuz, 2009; Antoniou et al., 2016; Bertomeu and Cheynel, 2016). However, considering that most of the largest shareholders of domestic listed companies are sponsor shareholders, although the internal mechanism can reduce agency costs, it also creates convenience for the absolute controlling shareholder to control the management, conduct related transactions, occupy funds, and other behaviors that will reduce the company’s performance (Gode and Mohanram, 2003). Therefore, the concentration of the company’s ownership structure and the performance of the company are negatively correlated (Lambert et al., 2007).

Some scholars also pointed out that the more concentrated the company’s equity, the better the company’s performance. From the perspective of operation, the higher the company’s equity concentration, the better the company’s operating performance, and the two show a positive correlation (Easley et al., 2002; Botosan and Stanford, 2005; Papakroni, 2013). The performance of equity-concentrated companies is significantly better than that of equity-diversified companies, especially in an environment with immature capital markets, unsound laws, and insufficient investor protection. But at the same time, due to the existence of the absolute controlling shareholder (Ali et al., 2014), the interests of the small and medium shareholders have been damaged, so the centralized ownership structure is necessary to diversify the shareholding (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997).

In a company with a high concentration of equity, the encroachment of small and medium shareholders is mainly manifested in the damage of the interests of small and medium shareholders by the controlling shareholder. Lemmon and Lins (2003) analyzed Asian listed companies in the economic crisis: due to the separation of control rights and cash flow rights caused by the pyramid ownership structure, the rights of controlling shareholders were expanded, which made large shareholders tend to encroach on the interests of small and medium shareholders, and the greater the degree of separation between the two, the more serious this phenomenon was (Minutiello and Tettamanzi, 2022).

In a dispersed ownership structure, this kind of infringement is often caused by management, which can be mitigated through equity incentives (Francis et al., 2008; Dhaliwal et al., 2011). When the external capital market is imperfect, the internal mechanism is imperfect, and the protection of investors is insufficient, the management will control the formulation and implementation of equity incentives (Kammoun and Djerry, 2021). This makes this incentive a way for management to gain vested interests rather than protect shareholder interests.

When the shareholding level of large shareholders is maintained between 35 and 63%, the proportion of large shareholders’ equity increases, and the private interests obtained by large shareholders out of small shareholders are more difficult to compensate for the loss of cash flow rights (Petersen, 2009; Suijs and Wielhouwer, 2019). Therefore, within this range, the increase of the large shareholder’s equity will have a positive effect on corporate performance. The high concentration of equity is actually a substitute for the lack of legal protection of shareholders’ interests. Therefore, from another perspective, highly concentrated equity is actually a protection for shareholders, but it is more focused on large shareholders (Chen, 2018; Li et al., 2021). The centralized ownership structure can prevent insider control and reduce agency costs, but it has a “tunnel effect.” Therefore, we should focus on how to protect the interests of small and medium shareholders for the prevailing dominance phenomenon in our country.

It is widely believed that a dispersed ownership structure will invite hostile takeovers. However, in some special cases, shareholders within a company with a dispersed ownership structure may boycott the acquisition, which will be detrimental to the realization of the acquisition (Collins, 2011; Thomas, 2010). The equity alliance formed by different shareholders within the enterprise can resist the market’s acquisition of the company, and a solid alliance structure can never let the acquirer retreat or put the acquisition in a huge predicament (Cohen and Malkogianni, 2021.

The consensus view of most scholars is that, compared with companies with concentrated ownership, companies with dispersed ownership are more likely to compete for control rights. Suijs and Wielhouwer (2019) explained the relationship between ownership structure and control rights from the perspective of company value (Orhun, 2019). He established a company value model, and found that the contention for control can improve the value of a company with a dispersed ownership structure, but it is the opposite for a company with a centralized ownership structure. Shleifer and Vishny, 1997 believed that shareholders cannot effectively supervise management, which is prone to principal–agent problems, and the control market will introduce external large shareholders to supervise management, which is more likely to lead to control competition.

In 1988, Vanke was formally established and completed the shareholding system reform; in the same year, it entered the real estate industry. So far, Vanke has completed the transformation from a single operation to a diversified operation. In 1991, Vanke was listed on the A-share market, becoming one of the earliest listed companies in China. As the largest residential development company in mainland China, Vanke has been included in several Forbes rankings, and has been rated as “China’s Most Responsive Real Estate Aircraft Carrier,” “100 Billion Aircraft Carrier,” and “Leader in Corporate Transformation.” By the end of 2015, Vanke had total assets of 611.3 billion yuan, net assets of 136.3 billion yuan, operating income of 195.5 billion yuan, and net profit of 18.1 billion yuan, an increase of 15.3% over the same period in 2014, and a return on net assets of 19.14% in the same year, still the largest real estate company in the industry. Since 2015, Vanke’s equity dispute has gradually attracted the attention of the public (Figure 1).

On July 10, 2015, Qianhai Life, a subsidiary of Baoneng, purchased 5% of Vanke stocks for the first time. On July 24, Jushenghua, a concerted action person of Qianhai Life, once again purchased the stocks of Vanke and became the second largest shareholder of Vanke with 10% of the stocks. On August 26, Baoneng once again increased its shareholding in Vanke by 5.04%, surpassing China Resources for the first time with a shareholding ratio of 15.04%, and became the largest shareholder of Vanke. Subsequently, China Resources once again became the largest shareholder of Vanke with a 15.29% stake through two stock increases in August and September (Wang et al., 2019).

Since then, Baoneng and Vanke’s equity dispute around Vanke has reached a fever pitch. On December 17, 2015, Baoneng once again became the largest shareholder of Vanke with a 23.52% stake. So far, Baoneng’s shareholding ratio was close to the red line of the company’s acquisition, and Vanke was facing the biggest acquisition crisis since the “Baoneng Battle” in 1994 (Zhang, 2018). On the same day, WANG Shi, the founder of Vanke, publicly declared that the “Battle of Wanke” officially started.

On December 18, 2015, after the daily trading limit, the management of Vanke submitted a request to the China Securities Regulatory Commission to suspend trading on the grounds of asset restructuring and acquisition, and the trading of Vanke’s A stocks and H stocks was suspended on the same day.

After that, Vanke united all parties to resist Baoneng’s acquisition: on December 23, 2015, it sought Anbang as a concerted party. On March 3, 2016, China Resources pledged to support Vanke as always. On March 13, Vanke wanted to introduce Shenzhen Metro as its concerted action.

The situation took a dramatic turn: on March 17, 2016, after Vanke announced its cooperation with Shenzhen Metro, China Resources suddenly raised a question to the regulatory authorities about Vanke’s operational compliance. In June of the same year, the decision to purchase Shenzhen Metro assets was opposed by three directors of China Resources. The next day, China Resources once again questioned the rationality of Vanke’s restructuring plan for Shenzhen Metro. On June 23, the two large shareholders of China Resources and Baoneng stated that they would jointly oppose the asset reorganization of Vanke and Shenzhen Metro.

On June 24, 2016, China Resources once again became the largest shareholder of Vanke, and then Baoneng requested the removal of seven directors including WANG Shi and YU Liang, two independent directors, and three supervisors. At Vanke’s annual shareholder meeting on June 27, shareholders focused on whether to remove 12 directors and high salaries for management.

On June 30, 2016, China Resources announced to the public that the company would not agree to the resolution to remove the board of directors of Vanke. The reason was: the large-scale recall will have a serious adverse impact on Vanke’s future medium and long-term development. The move once again sparked public discussion and controversy over Vanke’s corporate governance.

On July 4, 2016, the first day of Vanke’s resumption of trading, it encountered the limit down. The next day, Jushenghua once again purchased a total of 75 million Vanke A stocks. So far, Baoneng holds 24.97% of Vanke’s total stocks (Venkatesh and Chiang, 2012). The frequent placards of the Baoneng were once again resisted by the management of Vanke: on July 14, Vanke announced that it would jointly acquire a commercial real estate company with a mysterious partner. On July 18, Vanke reported to the China Securities Regulatory Commission, Shenzhen Stock Exchange and other regulatory agencies that Baoneng’s asset management plan was suspected of irregularities, resulting in Baoneng’s disclosure of nine asset management plans.

On August 4, 2016, Evergrande purchased 517 million stocks of Vanke for 9.1 billion yuan, with a shareholding ratio of 4.68%. In the following 3 months, Evergrande continued to increase its holdings of Vanke by acquiring tradable stocks. As of November 29, the Vanke A stocks held by Evergrande accounted for 14.07% of Vanke’s total stock capital, making it the company’s third largest shareholder, close to China Resources, the second largest shareholder (Verrecchia and Weber, 2006).

Before that, Vanke’s equity setting and management had been considered a model in the real estate industry. The occurrence of the control competition rights has attracted widespread attention from media public opinion and industry scholars, leading to a great discussion on corporate governance and equity setting. In addition, regulators and mainstream media, including many scholars, have called for all parties to pay attention to the protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders.

The adverse impact of the hostile takeover on Vanke’s sales scale was shown in Table 1. Vanke’s sales in July 2016 fell by 35% year-on-year, a much faster decline than the same period in 2015. In addition to the off-season sales, the reason for the rapid decline in performance is the struggle for control. Especially in June, Baoneng proposed to dismiss all the management, which forced the management center of Vanke to shift to the equity disputes, which seriously affected the normal operation.

The adverse impact of the hostile takeover on Vanke’s operating income and profit is shown in Table 2. In the first half of 2016, the growth rate of Vanke’s gross profit was far behind that of operating income. Compared with the same period in 2015, the profitability of enterprises has dropped significantly. From the perspective of the real estate industry alone, the interest rate of Vanke’s real estate industry in 2016 also dropped by nearly three points compared with the same period in 2015.

The competition for control caused by the hostile takeover has caused many unstable factors to the normal operation of Vanke, which was contrary to the demands of the small and medium shareholders for the company’s stable operation, so that the investment returns of the majority of small and medium shareholders cannot be effectively guaranteed.

This paper selected the stock price within the event window ([−3,10]) to measure the market’s reaction to the Vanke equity disputes. This paper measured Vanke’s individual stock rate of return Ri,t and market rate of return Rm,t, and calculates Vanke’s normal rate of return E(Ri,t), Abnormal Return ARi,t and Cumulative Abnormal Return CARi in different event windows (Bertomeu, 2015; Hua et al., 2018).

i) Calculating the coefficients α and β.

Ri,t refers to the actual rate of return of a stock on day t, the specific arithmetic formula is

Ri,t = (Pi,t−Pi,t−1)/Pi,t−1, and Pi,t is the closing price of stock i on day t; Rm,t is the market rate of return, and its specific calculation method is

Rm,t = (It−It−1)/It−1. It in this paper is the Shenzhen stock index on the t day. In addition, αi and βi are parameters to be solved, and εt is a random error term.

ii) Calculating the normal rate of return E(Ri,t).

iii) Calculating Abnormal Return (ARi,t) and Cumulative Abnormal Return (CARi).

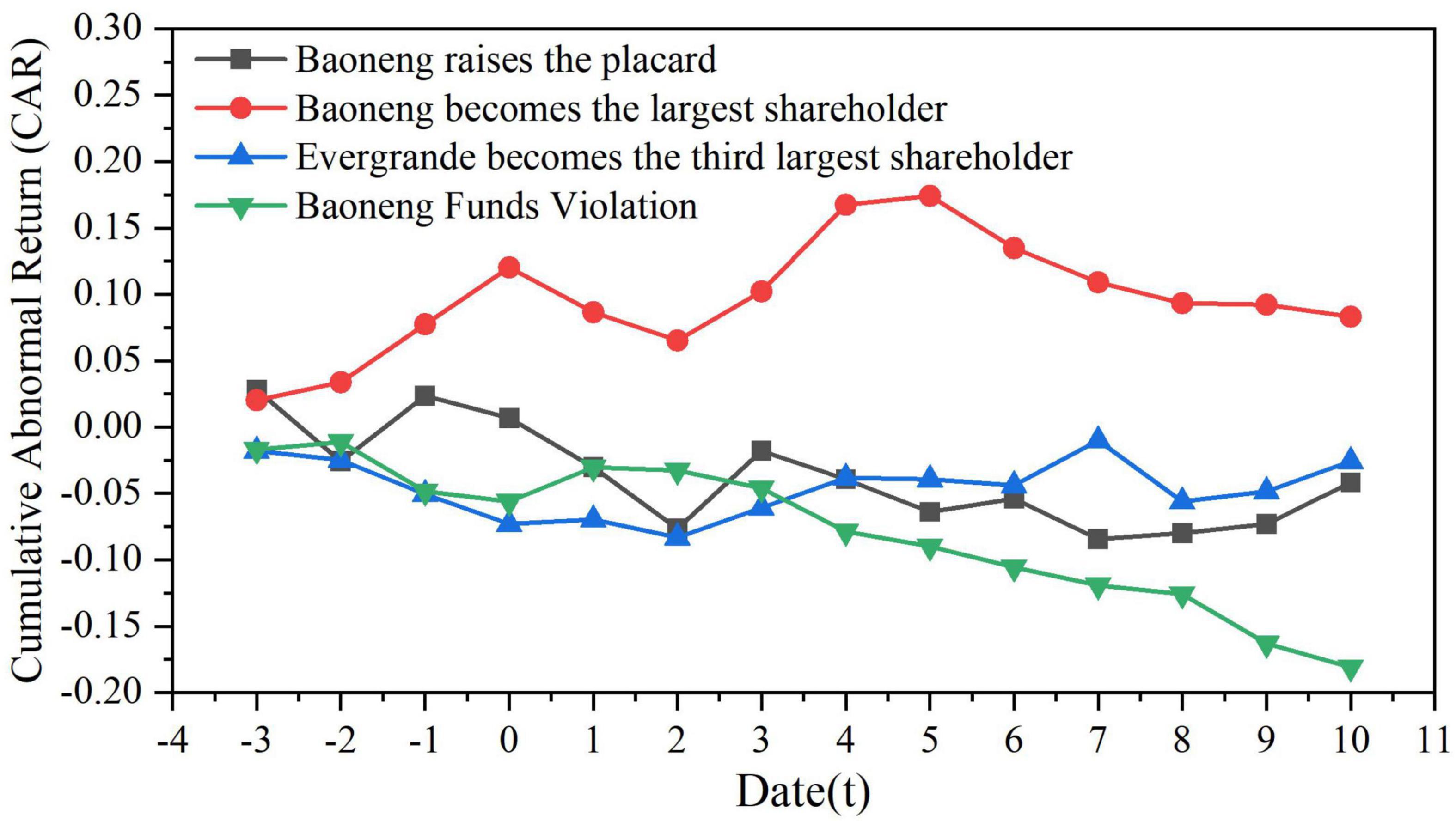

iv) Performing a significance test on the Cumulative Abnormal Return (CAR), and the CAR trend chart in Figure 2 is obtained.

Figure 2. Cumulative abnormal return trends in each event window for control rights. Data source: Derived from the CAR value calculated from the stock price (Supplementary Table 1).

The CAR value of Baoneng showed an overall downward trend and was negative, indicating that the Vanke equity dispute had greatly reduced the market’s expectations for Vanke, and the excess rate of return had reached −3.6 and −4.6%. The management’s factional dividend plan led to a brief increase in the CAR value (t = 3), but then it fell again, and the CAR value began to gradually rise to 0 again at t = 7. After Baoneng became the first shareholder of Vanke, the CAR value decreased at t = 1 and t = 2, and the excess returns were −3.6 and −1.4%, respectively; it started to pick up in the next 3 days and then decreased again in the last 5 days of the window.

A negative excess rate of return indicates that the interests of small and medium shareholders have been violated. At the same time, violent stock price fluctuations increase the capital risk of the acquirer, which may further damage the interests of small and medium shareholders after the acquisition is completed. Considering that Baoneng acquired Vanke this time through a large number of asset management products, leveraged financing and stock pledges, once Baoneng completes the acquisition, in order to quickly make up for capital costs and risks, the acquirer is likely to harm the interests of small and medium shareholders by transferring and hollowing out Vanke’s high-quality assets.

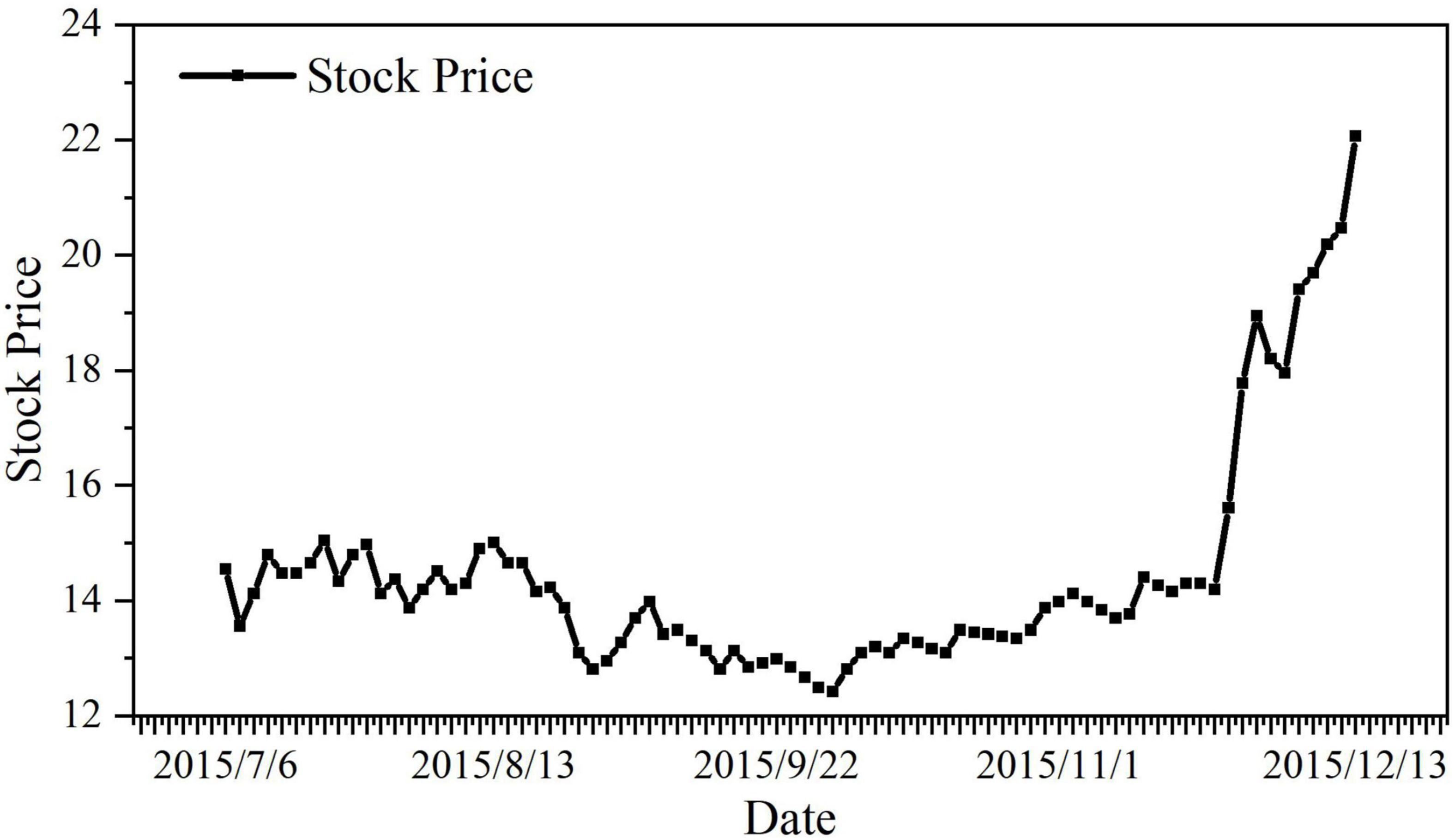

Stock repurchase can bring about a steady rise in stock price, improve the company’s shareholding structure, and improve corporate governance, which is conducive to the company’s future stable development and avoidance of hostile takeovers. Therefore, Vanke released the company’s stock repurchase plan on July 6. However, according to Figure 3, the stock price of Vanke has been higher than its actual highest price of 13.16 yuan for a long time; judging from the repurchase results, the highest price of Vanke’s repurchase was 13.16, and the repurchase plan was finally executed only 160 million yuan, only 1.6% of the expected. Vanke’s repurchase plan was nearly bankrupt.

Figure 3. Stock price chart after Vanke announced stock repurchase plan. Data source: Derived from the CAR value calculated from the stock price (Supplementary Table 1).

In the short term, Baoneng’s hostile takeover has actually caused violent fluctuations in the stock price, making it difficult for small and medium shareholders to enjoy capital gains in the secondary market (Zheng et al., 2021). In the long term, the bankruptcy of the repurchase plan has caused Vanke to fail to improve its own equity structure as scheduled, and it has fallen into a long-term chaotic and deformed struggle for control, which has seriously damaged the long-term interests of small and medium shareholders.

In order to ensure the completion of the acquisition and obtain the board position of Vanke, Baoneng proposed to remove the senior members of Vanke as the largest shareholder, resulting in a significant drop in the company’s sales scale and revenue in July compared with the same period in the past. Combining Tables 1, 2, the acquirer abused the authority of the largest shareholder in order to realize its own interests, causing serious turmoil in Vanke’s management and a significant decline in its performance. The stability of the company’s operation will be greatly reduced, which will make the market’s expectations for the company fall rapidly, which is not conducive to the company’s long-term development, thereby causing damage to the interests of small and medium shareholders.

The information disclosure system was originally designed to alleviate the disadvantage of the natural information asymmetry of small and medium shareholders (Darrough, 1993), but in order to reduce the acquisition cost, Evergrande not only failed to publish transaction information in a timely manner, but also spread false information everywhere (Zhou, 2019). The above practices seriously violated the requirements of the regulators for information disclosure of listed companies, and disrupted the order of the securities market and the stability of stock prices. The majority of small and medium shareholders are unable to achieve investment returns amid stock price fluctuations, and Evergrande’s attempt to gain private ownership by manipulating stock prices is extremely unfair to small and medium shareholders.

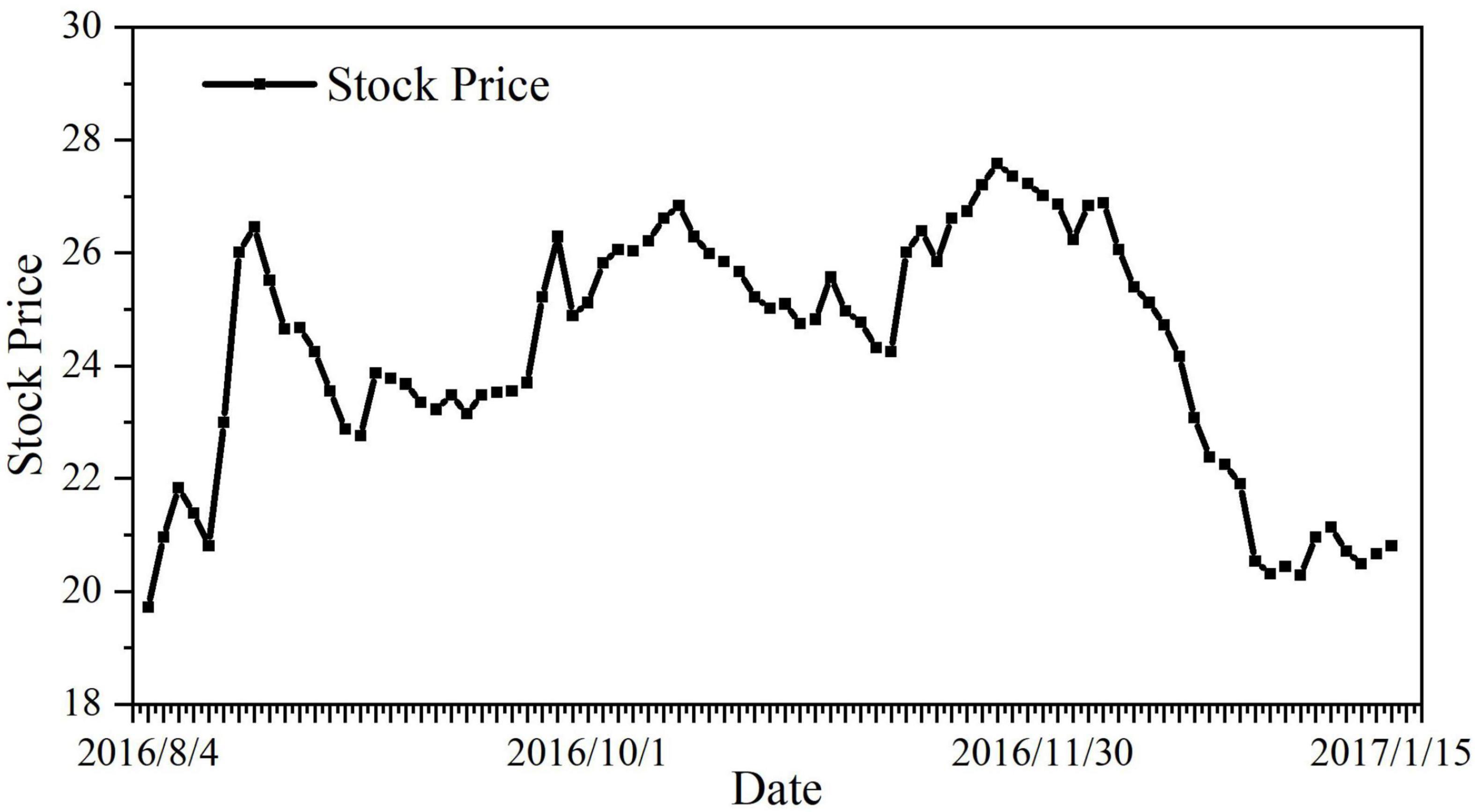

Figure 4 is the stock price chart of Vanke after Evergrande raised its placard. It can be found from the line chart that the increase of competing parties will increase the instability of the company’s stock price in the secondary market. Considering that the previous hostile takeover by Baoneng has led to the violent fluctuation of Vanke’s share price, Evergrande, as a new contender, will further aggravate this instability, which is a fatal blow to the interests of Vanke’s small and medium shareholders.

Figure 4. Vanke’s stock price chart after Evergrande raised the placard. Data source: http://stock.hexun.com/2016-08-04/185332058.html.

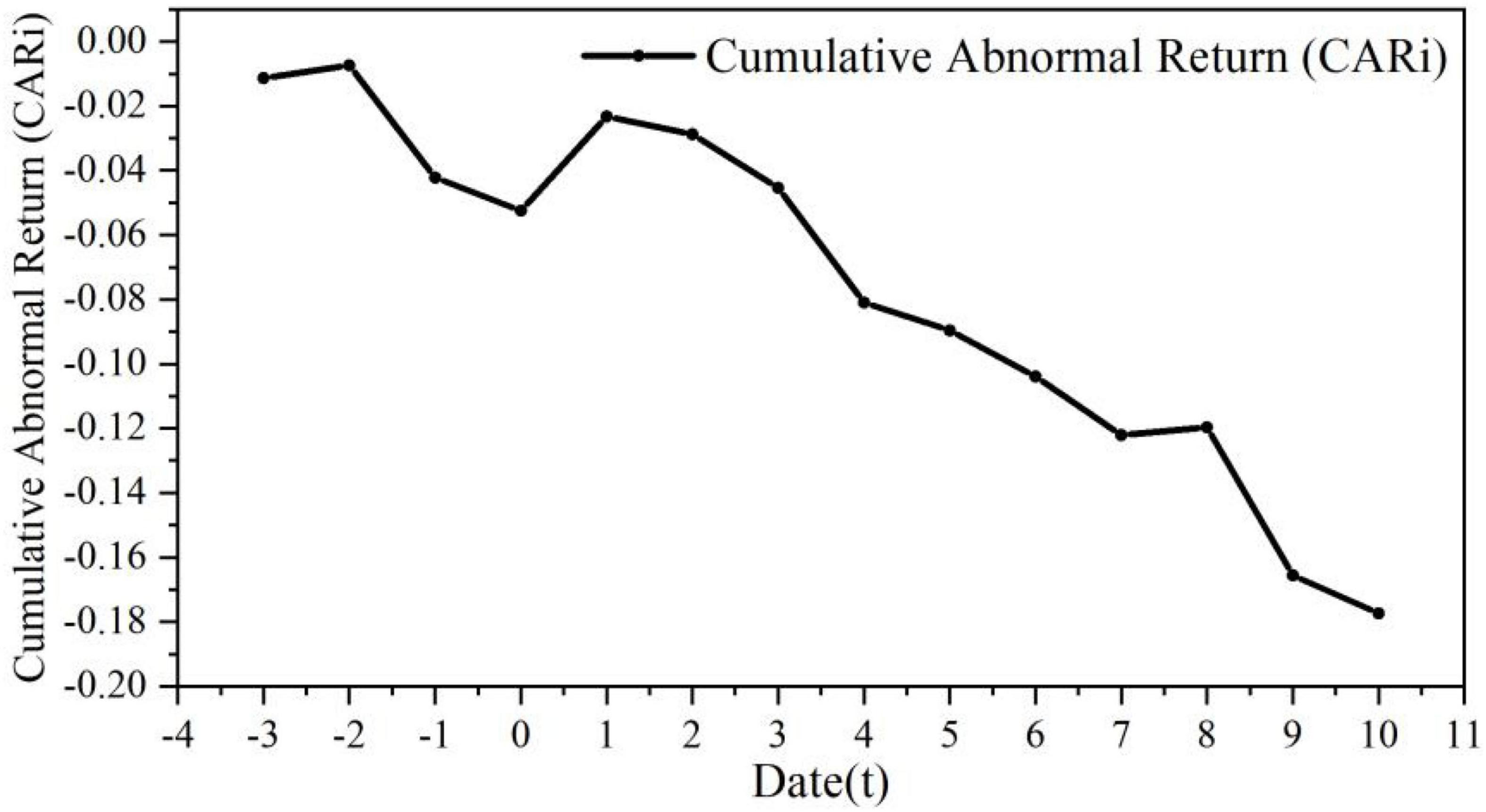

According to Figure 5, the trend of excess return in the above chart shows that the capital market has responded more quickly and farther to the event that Evergrande became the third largest shareholder, which proves from a market perspective that this event is not conducive to the interests of small and medium shareholders.

Figure 5. Changes in CAR of Evergrande becoming the third largest shareholder. Data source: Derived from the CAR value calculated from the stock price (Supplementary Table 1).

Evergrande becoming the third-largest shareholder has investors uncertain about the future of the battle for control of Vanke. What’s more serious is that due to Evergrande becoming the third largest shareholder, the outstanding shares of Vanke’s A-shares are only 14.65%. Too few tradable shares indicate that Vanke’s stock is likely to have become a “zhuanggu,” which will turn it into a profit tool for marketers to manipulate stock prices and trading volume. This will cause extremely serious damage to the trading rights and interests of small and medium shareholders.

Management deliberately dilutes stocks. According to Table 3, it is found that the scale of Shenzhen Metro’s assets is much higher than that of the same industry, but the level of operating income, net profit, and return on assets is much lower than the industry value. As the target of Vanke’s intention to purchase, Shenzhen Metro is not only in average profitability, but also considering the long payback period of the subway project, and it is difficult to achieve income in the short term, the acquisition of such a company will drag down Vanke’s previous excellent operating performance and profitability.

Management overvalued acquired assets. According to Table 4, it is found that the valuation time of Shenzhen Metro and Vanke’s major assets of Qianhai Life is only 20 days apart, but the valuation difference between the two is 22 billion yuan. The huge increase in a short period of time is suspected of being overvalued. According to Table 5, the shareholding ratio of Baoneng and China Resources decreased by 20.6% after the introduction of Shenzhen Metro. Since the “poison plan” was used to dilute the Vanke stocks held by Baoneng and thus protect the management’s control, the biggest beneficiaries of the restructuring are obviously the management of Shenzhen Metro and Vanke.

The management of Vanke bypassed the board of directors and ignored the interests of all shareholders and insisted on introducing Shenzhen Metro. In fact, it shows that there is a serious risk of insider control in Vanke, and the interests of small and medium shareholders are obviously not effectively protected.

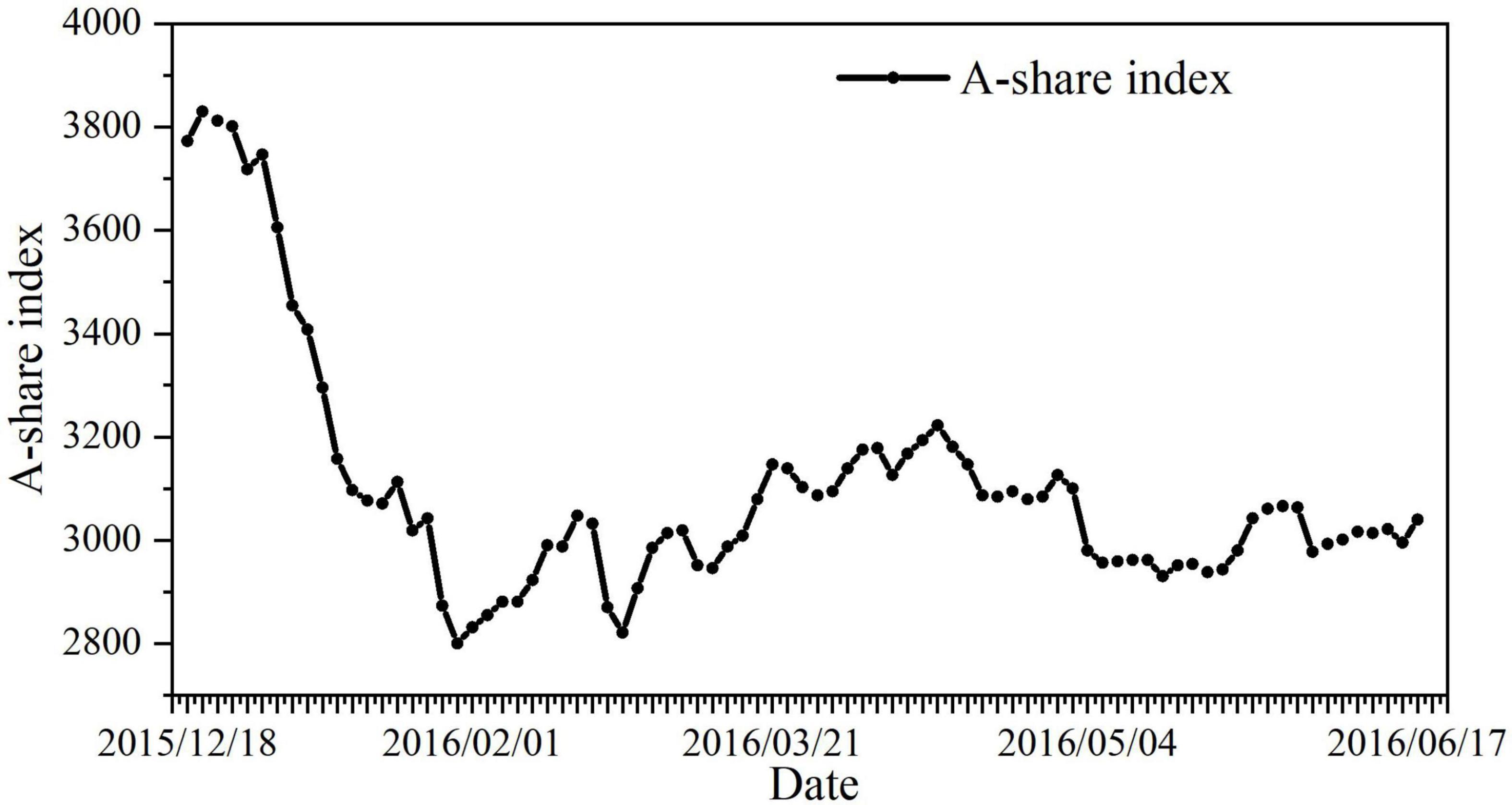

Before the suspension of Vanke’s trading, the company’s 17 executives promptly emptied the company’s stocks with a total market value of nearly 30 million yuan. Their timing of the transaction is so accurate that it makes people suspect that it is suspected of leaking confidential information. According to Figure 6, the Shanghai Composite Index fell from 3600 to 2900 during the suspension period. Due to Baoneng’s aggressive acquisitions, Vanke’s stock price was already inflated before the suspension, which made Vanke’s small and medium shareholders miss the best time to stop losses and exit the market, and their trading freedom was severely restricted. After the resumption of Vanke’s trading, the stock price plummeted, and small and medium shareholders had to bear huge losses for the reckless and arbitrary management of the management.

Figure 6. Trend chart of the A-share index during the suspension period of Vanke. Data source: Trend chart of the A-share index during the suspension period of Vanke. https://finance.eastmoney.com/news/1354,20160704638722937.html.

Due to the intervention of Baoneng and Evergrande, there have been many cases of investors “chasing up and down.” The dispute over control has caused the instability of Vanke’s stock price, coupled with the inability to arbitrage or stop losses in a timely manner, making small and medium shareholders “locked up” when the stock price is high, and ultimately causing damage to their own interests. Small and medium shareholders lack short-term capital technology and information channels. Compared with the fluke mentality of “making a lot of money,” it should be the attitude of small and medium shareholders not to rashly increase their holdings and stop losses in a timely manner.

Vanke, as a typical company with highly dispersed equity, holds a shareholding ratio of 65% in Vanke by small and medium shareholders. After Baoneng became the largest shareholder of Vanke, the proportion of small and medium shareholders is still close to 50%. It can be said that the small and medium shareholders are the largest shareholders of Vanke in the true sense (Li et al., 2018).

In the dispute over control, any decision made by Vanke’s management did not reflect the opinions of small and medium shareholders. On the contrary, whether it is the introduction of Shenzhen Metro or the hasty suspension of trading, every measure taken by the management to counter Baoneng has seriously damaged the interests of small and medium shareholders. The enthusiasm of small and medium shareholders to participate in the decision-making of company affairs is not high, and the existence of free-rider psychology makes it difficult for the company to make long-term decisions in line with the interests of small and medium shareholders.

From the perspective of the company’s equity protection, Vanke does not have a “partnership system” similar to Alibaba to ensure that the founder team can stably control the company. The founder WANG Shi tried to restrict Baoneng’s acquisition by introducing Shenzhen Metro, but was unexpectedly opposed by the “former owner” China Resources. The prolonged suspension and struggle to deal with acquisitions have had a severe negative impact on Vanke’s performance.

Various deeds in the equity disputes showed that Vanke’s ownership structure was difficult to stabilize the company’s control, and at the same time, it cannot effectively reduce the adverse impact of hostile takeovers on the company’s long-term development. In fact, it was precisely because the equity setting was unreasonable that it led to the competition for its control rights, which ultimately damaged the interests of small and medium shareholders.

Insider control is the biggest flaw in Vanke’s corporate governance. The founder WANG Shi has a huge responsibility in the company’s operation and has played a pivotal role in Vanke’s development and growth into the world’s best real estate developer. But in fact, China Resources, as the largest shareholder, rarely participates in the company’s operations, and has not achieved real control.

In Table 6, Guoxin Jinpeng No. 1 was a business partner system launched by Vanke’s management in 2014, that is, Vanke’s internal employees hold shares. Vanke executives represented by WANG Shi and YU Liang hardly hold the company’s stock, but they had long held the actual control of the company. Their decision-making in the battle for control was even more deviated from the interests of shareholders, and even in order to maintain their control, they used actions such as suppressing the stock price, hasty suspension of trading, and reorganization of shares. They had completely disregarded the interests of small and medium shareholders.

The psychology of chasing up and down. In the struggle for control, Baoneng acquired a large number of tradable shares in the secondary market, which led to the rise of Vanke’s share price, which triggered the psychology of small and medium shareholders chasing the rise and selling the fall. Baoneng used leveraged funds to leverage Vanke, which was more speculative than investment. Small and medium shareholders blindly follow the trend and hope to get rich overnight, so they rush to buy Vanke stocks. The subsequent slump in stock prices and the suspension of trading for more than half a year not only caused small and medium investors to suffer unbearable losses, but also damaged their right to free trading.

All parties involved in the competition are suspected of various violations. A variety of violations such as insider trading, information disclosure violations, and stock price manipulation occurred in this control competition, which seriously affected the stability and fairness of the securities market. This is extremely detrimental to the protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders.

First, the enforcement of the information disclosure system is insufficient. For example, Evergrande did not comply with the truthfulness, accuracy, and completeness of the disclosed information when purchasing stocks of Vanke. For another example, Vanke’s forced trading suspension was suspected of insider trading, and the management did not comply with the fairness principle in the information disclosure system.

Second, the punishment is not strong. The various behaviors of all parties in this control right struggle have damaged the legitimate rights and interests of small and medium shareholders. However, the regulatory authorities did not take appropriate measures against the relevant personnel. This is more of an extrajudicial favor to the parties involved in the battle for control. Whether it was the management’s hasty suspension or the acquirer’s abuse of information disclosure, they were only criticized by the regulatory authorities without further disciplinary measures.

Finally, the litigation system is flawed. In this competition for control rights, in the face of the company’s management’s many reckless behaviors, the small and medium shareholders have no right to appeal for protection when their own rights and interests have been violated.

According to Table 7, as of June 30, 2015, the board of directors of Vanke consisted of 11 members, including 4 independent directors and 7 directors.

First, the independence of independent directors was questioned. On June 18, 2016, in Vanke’s proposal to introduce Shenzhen Metro, ZHANG Liping had a relationship with the company’s production and operation, but served as an independent director of the company. The economics and independence of independent directors had been severely affected. Obviously, ZHANG Liping should not continue to serve as an independent director of Vanke.

Second, independent directors were suspected of revealing company secrets. In addition, during equity disputes, independent director HUA Sheng repeatedly published highly targeted and offensive remarks in the public media, including criticism of the company’s management, opposition to large shareholders and the details of the board’s decision-making. This was not in line with the code of conduct for the position in the first place, and its compliance legitimacy had been questioned.

Finally, the independent directors were suspected of not fully performing their duties. In this equity disputes, WANG Shi publicly doubted the rationality of Baoneng becoming the largest shareholder of Vanke in the media, and then HUA Sheng began to question the motive and ability of Baoneng’s acquisition in the article. However, the independent directors representing the interests of small and medium shareholders did not raise any different opinions. This had made it hard to believe that the independent director system of Vanke really fully performs its duties.

The information disclosure of listed companies is an important means to make up for the information asymmetry in the securities market and meet the information requirements of the majority of investors. Therefore, for individuals or collectives who do not use or even abuse information disclosure tools correctly, the regulatory authorities should severely punish and strengthen supervision in this regard.

The important reason why it is difficult to effectively protect the interests of small and medium shareholders is that China currently lacks an effective mechanism for small and medium shareholders to hold listed companies accountable, so that the illegal cost of all parties infringing the interests of small and medium shareholders is extremely low (Ball et al., 2016). Therefore, market regulators should promptly introduce civil accountability systems related to abusive information disclosure, insider trading, and stock price manipulation, and compel violators to make economic compensation for small and medium shareholders whose interests have been damaged from the perspective of laws and regulations. It can not only play a warning role, but also effectively curb the recurrence of violations of relevant regulations (Jonathan Lewellen, 2015).

To improve the shareholding structure, it is necessary to ensure the control and balance of shareholders. When improving the company’s equity structure, listed companies should pay attention to ensuring that the company’s shareholders can effectively control the company’s control rights and prevent the recurrence of equity disputes. In order to protect the interests of small and medium shareholders, the improvement of the shareholding structure should also pay attention to the ability to effectively check and balance other shareholders, and at the same time to supervise the management’s business decisions.

From the perspective of protecting the interests of small and medium shareholders, market value management focusing on the long-term development of the company and building investor relations can not only reflect the price discovery function of the capital market, but also help protect the interests of small and medium investors.

Small and medium shareholders need to be rational in the secondary market. When investing, small and medium shareholders should avoid following the trend, “fighting the luck” and blindly listening to gossip, maintain due vigilance, and carefully screen the asset status and future value of listed companies (Valta, 2012). Small and medium shareholders should make rational investments according to their own risk appetite and actual economic level, and must not have the mentality of “a huge profit” and “get rich overnight,” so as to avoid unnecessary losses to themselves.

Small and medium shareholders should also actively participate in the management of the company. At this stage, online voting at the general meeting of shareholders of listed companies has become popular (Li, 2010). Only by actively and responsibly exercising their legal rights and actively participating in the company’s business decisions can small and medium shareholders effectively safeguard their own interests.

Acquirers should spontaneously form an attitude of maintaining market order and the interests of small and medium shareholders. Protecting the interests of small and medium shareholders requires the self-consciousness of the acquirer. Acquirers cannot only consider the results of business competition and ignore the legitimate rights and interests of small and medium investors (Berger et al., 2012). In the competition for control rights, we should consciously abide by market rules, and there should not be behaviors such as manipulation of stock prices, insider trading, and abuse of information disclosure tools that disrupt market order and investor confidence.

This paper took the equity dispute of Vanke as the background, and mainly studied the damage to the interests of small and medium shareholders in the equity dispute. This paper mainly drew the following conclusions:

First of all, the highly dispersed ownership structure is the main reason why Vanke has encountered equity dispute. Vanke’s shareholding is too dispersed and the stock price has been sluggish for a long time, which has greatly reduced the acquisition difficulty and cost of Baoneng, thus triggering Baoneng’s brutal invasion. The dispersed ownership structure also led to Vanke’s long-term insider control of the management. There was a backlash from management to defend its control when the company faced a hostile takeover. The above two factors eventually led to the occurrence of the Vanke equity dispute.

Second, in the struggle for control, neither the management, major shareholders nor acquirers take into account the interests of small and medium shareholders. Whether it is the anti-takeover measures taken by the management of Vanke, or the equity dispute by China Resources, Baoneng, and Evergrande, their actions have actually caused damage to the interests of small and medium shareholders.

Finally, the protection of the interests of small and medium shareholders is imminent. The regulatory authorities are too lenient to supervise and punish all parties that harm the interests of small and medium shareholders, and the existence of opportunism makes them more reckless with their actions that infringe on the interests of others. However, the small and medium shareholders lack effective ways to safeguard their legitimate rights and interests by participating in the company’s management decision-making, which intensifies the violations of all parties in the equity dispute, thus forming a vicious circle.

At present, my country’s regulatory agencies, listed companies or small and medium shareholders themselves lack substantial measures to protect the interests of small and medium shareholders. In the subsequent research process, this paper hopes to use other research methods to conduct a more comprehensive and systematic analysis of the large sample data of the capital market, so as to draw universal conclusions.

China Vanke Co., Ltd. is referred to as Vanke.

Shenzhen Baoneng Investment Group Co., Ltd. is referred to as Baoneng.

China Resources Group is referred to as China Resources.

Evergrande Real Estate Group Co., Ltd. is referred to as Evergrande.

Qianhai Life Insurance Co., Ltd. is referred to as Qianhai Life.

Shenzhen Jushenghua Co., Ltd. is referred to as Jushenghua.

Anbang Insurance Group Co., Ltd. is referred to as Anbang.

Shenzhen Metro Group Co., Ltd. is referred to as Shenzhen Metro.

Company names are in bold italics, such as Baoneng.

People’s names are in bold italics, and all letters of the last name are capitalized, such as WANG Shi.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

CH: writing – review and editing, data curation, and formal analysis. WS: conceptualization and writing – review and editing. TO: investigation, formal analysis, and supervision. WL: resources, visualization, and supervision. BZ: resources, formal analysis, visualization, and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.857585/full#supplementary-material

Ali, A., Klasa, S., and Yeung, E. (2014). Industry concentration and corporate disclosure policy. J. Account. Econ. 58, 240–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.08.004

Antoniou, C., Doukas, J. A., and Subrahmanyam, A. (2016). Investor sentiment, beta, and the cost of equity capital. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 62, 347–367. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2014.2101

Armstrong, C. S., Core, J. E., and Taylor, D. J. (2011). When does information asymmetry affect the cost of capital? J. Account. Res. 49, 1–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679x.2010.00391.x

Ball, R., Gerakos, J., and Linnainmaa, J. T. (2016). Accruals, cash flows, and operating profitability in the cross section of stock returns. J. Financ. Econ. 121, 28–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.03.002

Berger, P. G., Chen, H. J., and Li, F. (2012). Firm specific information and the cost of equity capital. SSRN Electron. J. 57, 75—-108.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., and Schott, P. K. (2006). Trade costs, firms and productivity. J. Monet. Econ. 53, 917–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2006.05.001

Bertomeu, J. (2015). Incentive contracts, market risk, and cost of capital. Contemp. Account. Res. 32, 1337–1352. doi: 10.1111/1911-3846.12130

Bertomeu, J., and Cheynel, E. (2016). Disclosure and the cost of capital: a survey of the theoretical literature. Abacus 52, 221–258. doi: 10.1111/abac.12076

Bertomeu, J., Beyer, A., and Dye, R. A. (2011). Capital structure, cost of capital, and voluntary disclosures. Account. Rev. 86, 857–886. doi: 10.2308/accr.00000037

Botosan, C. A., and Stanford, M. (2005). Managers’ motives to withhold segment disclosures and the effect of sfaS No. 131 on analysts’ information environment. Account. Rev. 80, 751–771. doi: 10.2308/accr.2005.80.3.751

Caskey, J., Hughes, J. S., and Liu, J. (2015). Strategic informed trades, diversification, and expected returns. Account. Rev. 90, 1811–1837. doi: 10.2308/accr-51026

Chen, C., Li, L., and Ma, M. L. Z. (2014). Product market competition and the cost of equity capital: evidence from China. Asia-Pacific J. Account. Econ. 21, 227–261. doi: 10.1080/16081625.2014.893197

Chen, S. H. (2018). Research into the duties of directors in the mergers and acquisitions of listed companies: taking the battle for vanke’s control rights as the breakthrough point. China Legal Sci. 6, 127–160.

Cheynel, E. (2013). A theory of voluntary disclosure and cost of capital. Rev. Account. Stud. 18, 987–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11142-013-9223-1

Christensen, P. O., Rosa, L., and Feltham, G. A. (2010). Information and the cost of capital: an ex ante perspective. Account. Rev. 85, 817–848. doi: 10.2308/accr.2010.85.3.817

Cohen, S., and Malkogianni, I. (2021). Sustainability measures and earnings management: evidence from Greek municipalities. J. Public Budgeting 33, 365–386. doi: 10.1108/jpbafm-10-2020-0171

Collins, D. H. (2011). Huang. management entrenchment and the cost of equity capital. J. Bus. Res. 64, 356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.02.013

Corona, C., and Lin, N. (2013). Preannouncing competitive decisions in oligopoly markets. J. Account. Econ. 56, 73–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2013.04.002

Darrough, M. N. (1993). Disclosure policy and competition: cournot vs. Bertrand. Account. Rev. 68, 534–561.

Dhaliwal, D. S., Judd, J. S., Serfling, M., and Shaikh, S. (2016). Customer concentration risk and the cost of equity capital. J. Account. Econ. 61, 23–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.03.005

Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., and Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: the initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account. Rev. 86, 59–100. doi: 10.2308/accr.00000005

Dye, R. A., and Hughes, J. S. (2018). Equilibrium voluntary disclosures, asset pricing, and information transfers. J. Account. Econ. 66, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacceco.2017.11.003

Easley, D., Hvidkjaer, S., and O’hara, M. (2002). Is information risk a determinant of asset returns? J. Financ. 57, 2185–2221. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00493

Francis, J. R., Khurana, I. K., and Pereira, R. (2005). Disclosure incentives and effects on cost of capital around the world. Account. Rev. 80, 1125–1162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203425

Francis, J., Nanda, D., and Olsson, P. (2008). Voluntary disclosure, earnings quality, and cost of capital. J. Account. Res. 46, 53–99. doi: 10.1177/1062860613476733

Fresard, L. (2010). Financial strength and product market behavior: the real effects of corporate cash holdings. J. Financ. 65, 1097–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01562.x

Gebhardt, W. R., Lee, C. M., and Swaminathan, B. (2001). Toward an implied cost of capital. J. Account. Res. 39, 135–176. doi: 10.1111/1475-679x.00007

Gode, D., and Mohanram, P. (2003). Inferring the cost of capital using the Ohlson-Juettner model. Rev. Account. Stud. 8, 399–431.

Hail, L., and Leuz, C. (2009). Cost of capital effects and changes in growth expectations around US cross-listings. J. Financ. Econ. 93, 428–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.006

Hayes, R. M., and Lundholm, R. (1996). Segment reporting to the capital market in the presence of a competitor. J. Account. Res. 34, 261–279. doi: 10.2307/2491502

Hoberg, G., and Phillips, G. (2016). Text-based network industries and endogenous product differentiation. J. Polit. Econ. 124, 1423–1465. doi: 10.1086/688176

Hodges, C. W., Lin, B., and Lin, C. M. (2014). Product market competition, corporate governance, and cost of capital. Appl. Econ. Lett. 21, 906–913. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2014.896978

Hua, Z., Hu, H., and Ying, L. (2018). Reconstruction of corporate governance model and control rights fighting:a case study based on battle for control of vanke. Manage. Rev. 30, 276–290.

Hughes, J. S., Liu, J., and Liu, J. (2007). Information asymmetry, diversification, and cost of capital. Account. Rev. 82, 705–729. doi: 10.2308/accr.2007.82.3.705

Jeng, J. F., and Pak, A. (2016). The variable effects of dynamic capability by firm size: the interaction of innovation and marketing capabilities in competitive industries. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 12, 115–130. doi: 10.1007/s11365-014-0330-7

Kammoun, M., and Djerry, C. T. M. (2021). The underperformance of acquiring mutual funds: a re-examination of a puzzle. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 13:77. doi: 10.5539/ijef.v13n7p77

Lambert, R. A., Leuz, C., and Verrecchia, R. E. (2007). Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. J. Account. Res. 45, 385–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679x.2007.00238.x

Lang, M. H., Lins, K. V., and Miller, D. P. (2004). Concentrated control, analyst following, and valuation: do analysts matter most when investors are protected least? J. Account. Res. 42, 589–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679x.2004.t01-1-00142.x

Lang, M., Lins, K. V., and Maffett, M. (2012). Transparency, liquidity, and valuation: international evidence on when transparency matters most. J. Account. Res. 50, 729–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679x.2012.00442.x

Lemmon, M. L., and Lins, K. V. (2003). Ownership structure corporate governance and firm value: evidence from the East Asia financial crisis. J. Financ. 58, 1445–1468. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00573

Li, N., Shi, B., and Kang, R. (2021). Information disclosure, coal withdrawal and carbon emissions reductions: a policy test based on China’s environmental information disclosure. Sustainability 13, 1–24. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262014953.003.0001

Li, X. (2010). The impacts of product market competition on the quantity and quality of voluntary disclosures. Rev. Account. Stud. 15, 663–711. doi: 10.1007/s11142-010-9129-0

Li, Z. Q., Sun, Y., and Kang, Z. H. (2018). On the application of dual-equity sctructure system in China——based on the dispute between baoneng and china vanke. Econ. Forum 6, 125–128.

Minutiello, V., and Tettamanzi, P. (2022). The quality of nonfinancial voluntary disclosure: a systematic literature network analysis on sustainability reporting and integrated reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 29, 1–18. doi: 10.1002/csr.2195

Orhun, E. (2019). Disclosure decision in an entry game with costly information interpretation. Glob. Econ. J. 19:1950005. doi: 10.1142/s2194565919500052

Papakroni, J. (2013). The impact of loss incidence on analyst forecast dispersion: uncertainty or information asymmetry. J. Account. Financ. 13, 26–48.

Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev. Financ. Stud. 22, 435–480. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hhn053

Robert, S. (1983). Examining antitrust policy towards horizontal mergers. J. Financ. Econ. 11, 225–240. doi: 10.1016/0304-405x(83)90012-0

Suijs, J., and Wielhouwer, J. L. (2019). Disclosure policy choices under regulatory threat. RAND J. Econ. 50, 3–28. doi: 10.1111/1756-2171.12260

Thomas, C. J. (2010). Equity premia as low as three percent? Evidence from analysts’ earnings forecasts for domestic and international stock markets. J. Financ. 56, 1629–1666. doi: 10.1111/0022-1082.00384

Valta, P. (2012). Competition and the cost of debt. J. Financ. Econ. 105, 661–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.04.004

Venkatesh, P. C., and Chiang, R. (2012). Information asymmetry and the dealer’s bid-ask spread: a case study of earnings and dividend announcements. J. Financ. 41, 1089–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1986.tb02532.x

Verrecchia, R. E., and Weber, J. (2006). Redacted disclosure. J. Account. Res. 44, 791–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679x.2006.00216.x

Wang, Y. L., Bao, H., and Yang, X. (2019). On the reform of the dual-class share structure of chinese enterprises from the battle for the control of vanke. J. Inner Mong. Univ. Financ. Econ. 17, 59–62.

Weber, J. L. (2018). Corporate social responsibility disclosure level, external assurance and cost of equity capital. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 16, 694–724. doi: 10.1108/jfra-12-2017-0112

Zhang, P. (2018). Analysis of the legal basis of asset management plan between the baoneng and vanke—based on the analytical framework of the objective purpose. Private Law Rev. 29, 192–210.

Zheng, Z., Lin, Y., Yu, X., and Liu, X. (2021). Product market competition and the cost of equity capital. J. Bus. Res. 132, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.013

Keywords: small and medium shareholders, dispersed ownership structure, equity disputes, interest protection, corporate governance

Citation: He CX, Soh WN, Ong TS, Lau WT and Zhong B (2022) Analysis of Equity Disputes in Listed Companies With Dispersed Ownership Structure and Protection of Small and Medium Shareholders’ Interests. Front. Psychol. 13:857585. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.857585

Received: 17 February 2022; Accepted: 29 March 2022;

Published: 20 May 2022.

Edited by:

Michael A. Talias, Open University of Cyprus, CyprusReviewed by:

Chenguel Bechir, University of Kairouan, TunisiaCopyright © 2022 He, Soh, Ong, Lau and Zhong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Ni Soh, dHF0ZDUyQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.