- 1Department of Safety, Health and Environmental Engineering, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 2Department of Information Management, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 3Chulalongkorn Business School, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic have caused many enterprises to suffer great losses. Thus, companies have to take measures such as pays cut, furloughs, or layoffs, which caused dissatisfaction among employees and triggered labor disputes. Therefore, this study explores the service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior based on the decomposed theory of planned behavior in order to understand the behavioral intentions of employees through their mental states, job attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. This study conducted questionnaire surveys for employees in different industries, collected 281 valid questionnaires, and applied Structural Equation Model for the analysis. The results show: (1) employees believe organizational justice in the organization is important, and when they feel treated fairly, their job attitudes and beliefs are enhanced. (2) Employees’ job attitudes and beliefs support service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, in other words, they have positive job attitudes and beliefs and will actively provide better service to customers. (3) When employees are treated reasonably and fairly by the organization and have positive job attitudes (job satisfaction and organizational commitment) and perceived behavior control, their spontaneous service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior is stimulated, thus increasing organizational development.

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread globally in 2020, many countries and cities adopted lockdowns or similar measures to prevent the spread of this epidemic. Many people have been forced to stay at home, leading to great changes in their lives, such as working at home, even leading to fear of leaving home. When business slumps, an enterprise must cut spending (e.g., reducing working hours or wages), or even shut down. The magnitude of the unpaid leave due to COVID-19 is much larger than the financial crisis of 2007–2008. In addition to being afraid of catching the disease, employees worry about reduced income, unemployment, and unfair treatment by the organization. These psychological factors of fear or panic, as well as attitude towards employers may affect their performance and behavioral intentions, and employees’ performance will affect the organization’s performance (Kang et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2021). The most direct example is frontline service staff. Because they have most often contact with customers, they communicate information about the organization to customers. Customers may feel that the behavior of service staff represents the company, so their spontaneous and positive performance can benefit the organization. Therefore, this study focuses on service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior.

Many studies have applied the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to explore organizational citizenship behavior (OCB; e.g., Jung and Yoon, 2015; Radaelli et al., 2015; Aguiar-Quintana et al., 2020). These demonstrated that behavioral beliefs such as attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control influence OCB. Taylor and Todd (1995) proposed the decomposed theory of planned behavior (DTPB), decomposing some factors that affect behavior in the original theory, so it is more flexible than TPB. As mentioned above, the psychology of employees is an important factor affecting their action intentions. Previous studies have pointed out a correlation between organizational justice and civic behavior (e.g., Saifi and Shahzad, 2017). Employees’ perception of organizational justice affects their job attitude and behavior. Thus, this research uses disaggregated planning behavior theory to explore the impact of organizational justice on service-oriented OCB and to understand how employees’ perceptions of the organization affect their behavioral intentions. The next section describes DTPB and related research. In the third section, the research framework is proposed, conducting model validation is explained in the fourth section, and conclusions are presented in the final section.

Literature Review

This study applies social psychology to explore job attitude and behavior of employees. In order to more effectively and correctly understand relationships that affect organization members, this study uses DTPB to explore the behavior of employees and the impact of organizational justice on employee psychology. This section reviews relevant literature and empirical research.

Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior

In decomposed theory of planned behavior (DTPB) the belief structure underlying planning behavior theory is decomposed, as an evolution of TPB. DTPB was proposed by Taylor and Todd (1995) based on TPB (Ajzen, 1985) and the technological acceptance model (TAM; Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989), adding referent groups from innovation diffusion theory (Rogers, 1983). It also includes concepts of self-efficacy and facilitating condition; and it decomposes beliefs such as attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control into multi-dimensional belief variables.

Bagozzi (1981, 1982, 1983) found that multidimensional belief structures are more suitable than unidimensional constructs to describe the effects of behavioral attitudes. Some studies have also argued that a multi-dimensional belief structure is indeed more appropriate to explain “behavioral attitudes” (Bagozzi, 1981; Shimp and Kavas, 1984). In addition, the basis of TPB and TAM are both developed from the theory of reasoned action (TRA; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975).

As mentioned above, the model of DTPB is used to decompose the TPB, whose main factors include attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention. “Attitude” refers to an individual’s perception of good or bad, positive or negative, when engaging in a behavior. People’s attitudes toward a behavior are influenced by their “Behavioral Beliefs” and “Outcome Evaluation” (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). “Subjective norm” refers to the social or reference group pressure that an individual perceives when engaging in a particular behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1975, 1980; Lee and Green, 1991). “Perceived behavior control” refers to an individual’s ability to control opportunities and resources when engaging in a behavior (Ajzen, 1989). “Behavior intention” refers to the intensity of a person’s intention to engage in a behavior and is usually used to predict or explain actual behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). Attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavior control influence behavior intentions.

Taylor and Todd (1995) argued that the advantages of using DTPB are that (1) the relationship between predispositions and dimension of belief is clearer and (2) it is easier to identify specific contributing factor s because of the consistency between predispositions and dimensions of belief (Bagozzi, 1981; Shimp and Kavas, 1984). Thus, it is easier to understand the individual predispositions of different belief dimensions.

TPB has been an important theory for exploring human behavioral intentions and as a basis for discussing a wide range of issues such as employee behavior (e.g., Islam et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2021) and purchase intention (e.g., Ruangkanjanases et al., 2020). Moreover, as mentioned above, the multi-dimensional framework is more suitable for explaining behavioral intentions. Scholars have subsequently added other factors to TPB (e.g., Duan, 2022) or combined TPB with other theories (e.g., Luo et al., 2021), extending research on TPB. Hence, this study adopts DTPB as the theoretical basis for discussing factors that influence services-oriented organizational citizenship behavior.

Job Attitude

In DTPB, an important factor affecting behavioral intention is attitude (Taylor and Todd, 1995). Social psychologists consider that attitudes can be divided into affective and cognitive. The former reflects the individual’s feelings about a particular object, such as liking or disliking the work they are engaged in; the latter is whether the particular object can reflect personal thoughts and beliefs, such as whether the work performed can satisfy one’s own expectations. Thus, a person’s “attitude” toward something can be used to predict to what extent the person will engage in a behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975).

Attitude means an employee’s positive or negative evaluation of people, events, and things that influences his or her behavior (Robbins, 1996). Robbins (1993) argues that employees’ attitudes are critical in an organization because they affect performance. Steers and Black (1994) state that job attitudes can be categorized into three concepts: job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work participation. Martin and Bennett (1996) find that job satisfaction and organizational commitment are very important variables in the studies of organizational behavior. In many studies on behavior and job attitudes, job satisfaction and organizational commitment are central topics (Currivan, 1999; Dirks and Ferrin, 2002; Harrison et al., 2006). Studies have also found that job attitudes composed of organizational commitment and job satisfaction can be used to anticipate employee behavior (e.g., Moon, 2000; Harrison et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2010). Thus, according to the viewpoints of most scholars on the influencing factors of job attitude, this study divides it into the dimensions of job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Job Satisfaction

Since Hoppock (1935) put forward the concept of job satisfaction, scholars have developed different definitions of job satisfaction. Most interpretations of this aspect revolve around work-oriented or overall emotional responses (Kreitner and Kinichi, 1995). In addition, some scholars consider that job satisfaction refers to workers’ subjective attitudes toward their workplace (Dunham and Herman, 1975; Jayaratne, 1993; Murphy et al., 2002; Barling et al., 2003). Other studies have proposed aspects to measure job satisfaction, which can be roughly divided into external satisfaction (e.g., workplace, salary and compensation, employee bonus, welfare system, peer relationship, leadership style) and internal satisfaction (e.g., recognition, achievement, autonomy, learning, promotion, and honor from work; Weiss et al., 1967). This classification has been empirically verified (Arvey et al., 1989).

Organization Commitment

Organizational commitment was first conceptualized by Whyte (1956) and has become a widely discussed topic among management scholars. Whyte believed that members of an organization not only work for the organization, but also are part of the organization. Therefore, they identify with the values and targets of the organization, commit themselves to their work, and demonstrate loyalty (Sheldon, 1971; Buchanan, 1974). Organizational commitment is valued since high organizational commitment benefits organizational development by supporting the contributions and loyalty of employees to the organization. Porter et al. (1974) suggested that organizational commitment could anticipate turnover. Morris and Sherman (1981) thought it could also predict employee performance. Ferris and Aranya (1983) argued that it could also be used as an indicator of organizational performance.

Due to different research purposes, scholars have various definitions of organizational commitment. Steers (1977) pointed out that social psychologists and organizational behavior researchers have different perspectives on organizational commitment. One claim is “behavior commitment,” and the other is “attitude commitment.” Behavioral commitment is a belief that an organization’s members are influenced by their past behavior and continue to be committed to their work (Salancik, 1977); attitudinal commitment is an indication that an organization’s members display certain attitudes toward the organization. Other scholars have separated organizational commitment into effort commitment, value commitment, and retention commitment from the perspective of emotional attachment (Porter et al., 1974). Effort commitment refers to members’ willingness to work hard for the benefit of the organization; value commitment is the belief that members accept the targets and values of the organization; retention commitment is the strong desire of members to maintain their job opportunities (Mowday et al., 1982). Scholars also discuss organizational commitment from the viewpoints of behavior, attitude, values, exchange, and ethics. Morrow (1983) pointed out that there are at least 25 concepts and measurement methods related to organizational commitment. However, organizational commitment is commonly defined by attitude (Schwepker Jr., 2001; Spector et al., 2002; Jaramillo et al., 2005).

This study uses organizational commitment defined by the emotional attachment perspective (Porter et al., 1974). This concept emphasizes employees’ recognition of organizational goals and values, more effort and high work commitment, loyalty, and willingness to remain in the organization. Organizational commitment is divided into three factors: effort commitment, value commitment, and retention commitment.

Organizational Justice

From the perspective of human resources, organizations should consider the opinions of employees that affect their attitudes and behaviors toward work. Previous studies have used “organizational justice” to assess how much importance employees attach to the organization (e.g., Colquitt et al., 2001). Scholl et al. (1987) suggested that organizational justice means the subjective perceptions of employees regarding the justice of the organization in allocating resources or determining various rewards and sanctions. Organ (1988) believed that organizational justice is closely related to individual behavior, and whether managers are fair or not affects employees’ behavior. Organizational justice is one of the main factors affecting employee behavior, and it is also a management issue that managers must consider. In the study of organizational behavior, it is a topic that has been widely discussed. Some scholars believe that “justice” is a very important characteristics of organizations and also an important factor affecting employee behavior (Dittrich and Carrell, 1979; Niehoff and Moorman, 1993; Masterson et al., 2000). Schermerhorn (1996) argued that organizational justice is an indicator that can be used to explain whether employees are satisfied with their work status. If the reward is proportional to the effort, it has a positive effect; otherwise, it causes dissatisfaction and reduces performance. Erdogan et al. (2006) also emphasized that employees’ perceptions of justice are strictly related to leaders’ behaviors and attitudes. In short, organizational justice explores subjective perceptions of employees regarding the fairness of resource allocation and managers’ decisions on rewards and punishments. When members of an organization interact, employees often follow this principle to evaluate whether their input and output are proportional. When employees perceive the organization treats them fairly, they adjust their behaviors and attitudes, supporting organizational performance.

Reviewing the theoretical development of organizational justice, previous scholars focused on the discussion of “distributive justice” (Homans, 1961; Adams, 1965). Homans (1961) defined distributive justice as fairness in the distribution of interpersonal rewards and costs and believed that employees feel they are being treated fairly if their contribution is expected to be proportional to the allocation of organizational resources; otherwise Adams (1965) also focused on the concept of distributive justice. However, organizational justice does not have only a single dimension, and its dimensions vary according to the situations and theoretical interpreations. For example, Thibaut and Walker (1975) posited that a court’s judgment process affects people’s recognition of the judgment result. This, then, leads to the appearance of procedural fairness, which results in the dual aspects of distributive and procedural justice. Bies and Moag (1986) argued that previous studies had ignored the importance of interpersonal interactions and therefore proposed three constructs of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Since then, a more complete structure of organizational justice has been developed, generally known as the traditional three constructs. Subsequently, scholars have proposed four or six dimensions of organizational justice (e.g., Alexander and Ruderman, 1987; Colquitt et al., 2001), but the traditional three-dimensional approach is still used in most studies. This research also adopts distributive, procedural, and interactional justice to discuss.

Service-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors (Service-Oriented OCB) is an extension of OCB (Bettencourt et al., 2001) that refers to the attitudes and behaviors of front-line service staff who are enthusiastic and responsible in providing services to match the needs of customers. In an early study of OCB, Barnard (1938) argued that the success of an organization depends on the cooperation of its members. This kind of cooperative behavior requires the operation of some informal organizations to be effective, so the positive behavior required by non-organizations is also an important theoretical basis for OCB.

Service-oriented means that service staff provide high-quality services to meet customer needs through enthusiasm, courtesy, and sincerity. It also combines staff capability, willingness to learn, motivation and attitude (Hogan et al., 1984). In the service industry, customers’ perception of service quality comes through interactions with frontline service staff. Therefore, in addition to valuing employees’ OCB, service-oriented OCB is even more important for this industry (Borman and Motowidlo, 1993). Bettencourt et al. (2001) reviewed research on service-oriented OCB and suggested that the evaluation of service quality and performance should include service behavior from a non-technical perspective. Service-oriented OCB is a new type of service that refers to attitudes of enthusiasm, responsibility, and courtesy displayed by front-line service personnel in providing services. This kind of OCB to meet the needs of customers is customer-oriented behavior, so non-technical service behavior shows that service-oriented OCB is an extension of OCB. Service quality is the subjective perception of the service delivery process and the actual result of the service received by the customer, which is a key factor of competitive advantage (Liebermann and Hoffmann, 2008).

Service-oriented OCB has the three important connotations of loyalty, service delivery, and participation (Van Dyne et al., 1995; Bettencourt et al., 2001). Loyalty refers to employees who provide services/goods and show support for the organization, which may enhance or detract from the organization’s image (Schneider and Bowen, 1985; Bettencourt et al., 2001). Service delivery means that in the process of service delivery, front-line service personnel demonstrate courteous, reliable, dutiful, dedicated, and trustworthy behaviors (Parasuraman et al., 1988; George, 1991). Therefore, service delivery is an important factor that affects customer satisfaction, overall perception of service quality, and even customer loyalty (Bettencourt et al., 2001). Finally, participation means that when employees contact customers, they are the main source of information for customers and are the customer’s first and main impression of the organization. By participating in services, employees can provide management suggestions for improving service quality to enhance customer purchase intention and satisfaction (Schneider and Bowen, 1985; Parasuraman et al., 1988; George, 1991; Heskett et al., 1994; Bettencourt et al., 2001). Therefore, this study takes loyalty, service delivery and participation as factors of service-oriented OCB.

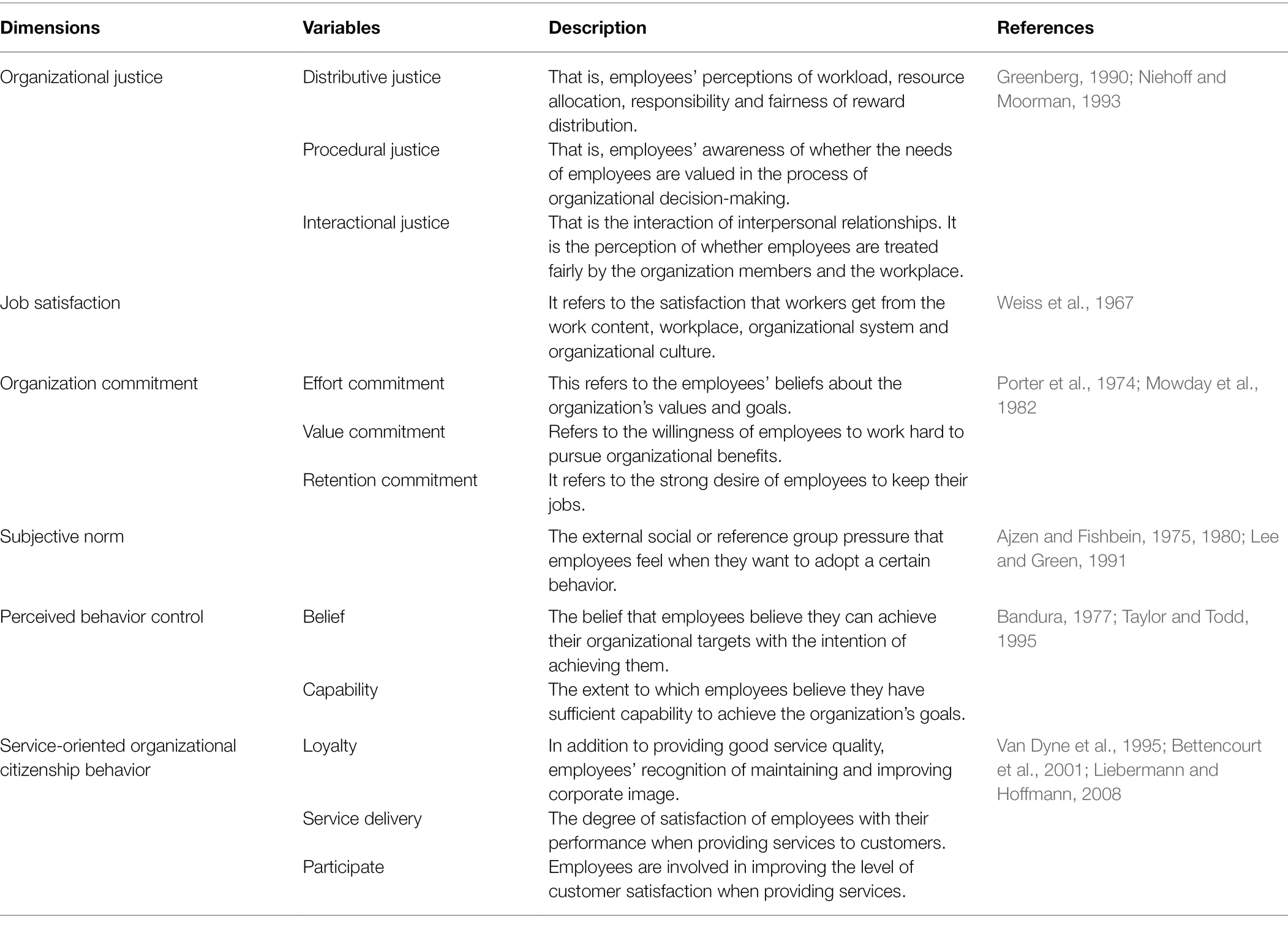

In summary, the operational definitions of the variables are organized as shown in Table 1.

Research Model and Data Collection

Based on the literature discussion, this study proposes research hypotheses and constructs research models. The process of collecting measurement data and analysis tools are explained below.

Hypothesis and Framework

Lawler and Hall (1970) stated that when a person expects to receive fair treatment for their performance, they work hard and further develop job satisfaction. Folger and Konovsky (1989) found that both procedural and distributive justice were significantly correlated with organizational commitment, and that procedural justice predicts organizational commitment more than distribution fairness does. Moorman (1991) found that organizational justice can significantly affect job satisfaction and furthermore: salary satisfaction has a significant positive relationship with distribution justice, promotion, and organizational commitment; that procedural justice is positively related to managerial satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work engagement; and that procedural justice and distributive justice is useful in predicting factors such as employee job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work commitment. Zahednezhad et al. (2021) indicated that organization justice (including distributive justice and interactional justice) positively and significantly affected nurses’ job satisfaction. Additionally, many empirical studies have found that organizational justice significantly directly affects organizational commitment (Martin and Bennett, 1996; Rahman et al., 2016; Aguiar-Quintana et al., 2020). Thus, this study predicts that employees’ perception of organizational justice should influence job attitudes, leading to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ perception of organizational justice has a significant impact on job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ perception of organizational justice has a significant impact on organizational commitment.

According to Adams (1965) equity theory, employees must perform well within organizational norms in order to receive more compensation. In an organizational environment, the three most important reference groups are colleagues, supervisors, and subordinates. For example, perceived organizational support means that employees recognize what behavior the organization wants them to perform or what employees they become under the organizational norms (Eisenberger et al., 1986). Ibragimova (2006) applied TRA to explore whether organizational justice affects the sharing of corporate knowledge and found that organizational justice has a positive relationship with subjective norms. Consequently, this study predicts a relationship between employees’ perceptions of organizational justice and subjective norms and proposes the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ perception of organizational justice has a significant impact on subjective norm.

Edwards (1991) researched on “personal-work fit” and believed that job supply includes salary, benefits, training, decision-making participation, and job richness, etc., and it is the source of organizational justice. For example, pay and benefits determine distributional justice and decisional involvement determines procedural justice. In terms of beneficial environmental factors, from the perspective of personal cognition, people’s perception is affected by the fair distribution of organizational resources and rewards. The fairer the distribution of external environmental resources and remuneration, there is no doubt that people think that they are treated fairly and the easier it is to accomplish organizational tasks. Hence, this study infers that employees’ perception of organizational justice should have a significant influence on perceptual behavior control, and then put forward the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: Employees’ perception of organizational justice has a significant impact on perceived behavior control.

Bettencourt and Brown (1997) found that job satisfaction and organizational justice positively influenced employee service-oriented citizenship behavior, resulting in higher customer satisfaction with service delivery. Bettencourt et al. (2001) also found that job satisfaction can effectively predict some service-oriented OCB. Other studies have found a relation between job satisfaction and OCB (Jung and Yoon, 2015; Torlak et al., 2021). Another study found that organizational justice (distributive and interactional justice) was significantly and positively related to nurses’ job satisfaction; and job satisfaction was significantly and negatively related to turnover intentions (Zahednezhad et al., 2021). There is also support for the finding that job satisfaction is a mediating variable between organizational justice and OCB (Saifi and Shahzad, 2017). Furthermore, organizational commitment has a significant positive relation with employee behavior (Su et al., 2019). Aguiar-Quintana et al. (2020) found that continuous organizational commitment significantly positively affects interpersonal relationships in OCB. Hasyim and Palupiningdyah (2021) also argue that organizational justice positively affects organizational commitment and further affects OCB. Therefore, this study concludes that job attitudes should also have a significant influence on service-oriented OCB, leading to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5: Employees’ job satisfaction has a significant impact on service-oriented OCB.

Hypothesis 6: The organizational commitment of employees has a significant impact on the intention of service-oriented OCB.

According to Taylor and Todd (1995) definition of subjective norms, employees’ normative beliefs and motivations to comply are influenced by their peers, supervisors and subordinates. Relationships between peers are the interaction of interpersonal relationships, whereas in the relationship between supervisors and subordinates, subordinates usually abide by the rules of superiors in order to maintain a smooth workplace relationship. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) pointed out that behavior is sometimes more affected by social environmental pressures than personal attitudes. For example, a supervisor wishes the employees to use a new operating system and also agrees with its functions. At this time, employees have a strong motivation to comply with the supervisor’s expectations, so positive subjective norms are created. Liker and Sindi (1997) explored when to influence employees’ willingness to continue to use expert systems to assist their work, confirming that subjective norms have a positive relationship with behavioral intentions. Bock and Kim (2002) found that subjective norms affect behavioral intentions. Torlak et al. (2021) studied the planned behaviors of nurses and found that subjective norms significantly positively affected burnout and then further significantly negatively affected OCB. Hence, this study concludes that the subjective norms of employees have a significant impact on service-oriented OCB, and puts forward the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 7: The subjective norms of employees have a significant impact on service-oriented OCB.

Internal factors refer to self-efficacy, such as information, skills, abilities, forgetting, emotions, and coerciveness; external factors refer to opportunities to help perform a certain behavior, which are the favorable environment (Ajzen, 1985; Taylor and Todd, 1995). Self-efficacy is considered from the social learning/cognitive theory proposed by Bandura (1977), and is regarded as an element of a special situation related to capability and is a dynamic concept. Self-efficacy can also be said to be the capability and belief that people have when they complete a certain behavior. In other words, self-efficacy is individuals’ belief in their ability to succeed and a judgment on their ability to complete. Employees in an organization have continuous interaction with the environment (e.g., rewards or punishments) to carry out the process of self-regulation, so people’s behaviors differ according to the situation. In short, when a person is engaged in a behavior, he or she can only perform actual behaviors when he or she is sure that he or she can effectively anticipate them. However, there are differences in previous findings regarding the relation between perceived behavioral control and behavioral intentions. Some studies have shown a significant relationship between the two (e.g., Torlak et al., 2021), but others have found no relationship (e.g., Chemseddine and Kamel, 2021). This study considers that frontline employees’ perceived behavior control has a significant impact on service-oriented OCB, so the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 8: Employees’ perceived behavior control has a significant impact on service-oriented OCB.

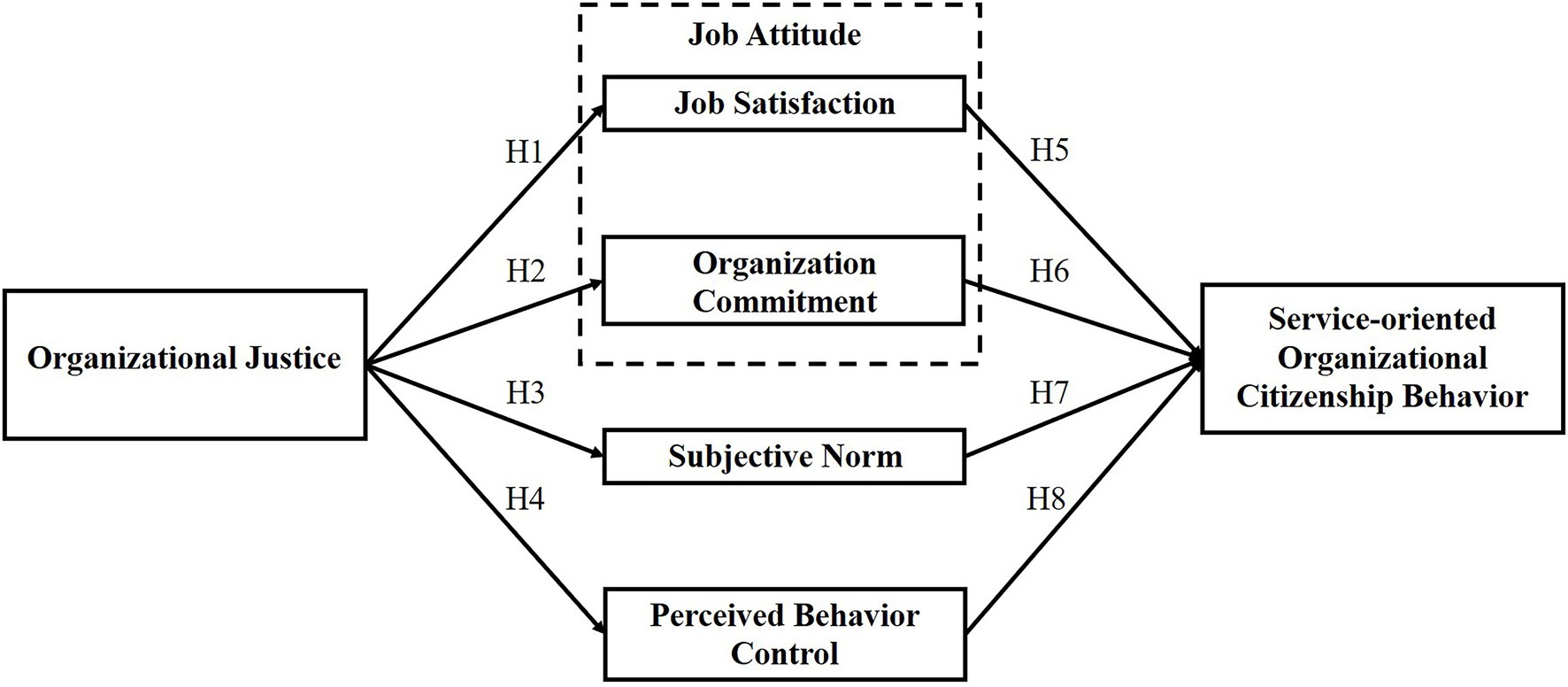

Based on the research purpose and literature review, this study argues that organizational justice impacts job attitudes (job satisfaction and organizational commitment), subjective norms, and perceived behavior control, which in turn impact service-oriented citizenship behavior (OCB). Thus, the conceptual framework of this study is constructed, as shown in Figure 1.

Materials

This study focuses on student workers and general workers because they are the main laborers in society. On-the-job training students use their free time to continue their studies, hoping to enhance their competitiveness with better development in the workplace. The sample of this study includes various fields and industries. The survey was conducted by distributing paper-based questionnaires. The questionnaires were anonymous and distributed by convenience sampling. A total of 315 questionnaires were collected, and invalid questionnaires were deleted. There were 281 valid questionnaires (89.21%).

Research Method

This study uses SPSS and SmartPLS and selects the appropriate data analysis method based on the research purpose and the measurement level of the variables. To explore the effects between the dimensions and to validate the fit of the research model, a Structural Equation Model (SEM) was used for data analysis to explore the relationship between potential variables and to test the proposed hypothesis. Since a single-stage SEM estimates both the measurement model and the structural model, if the model is not properly matched, it is difficult to judge whether the model error comes from the structural model or the measurement model, or both. For this problem, Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and Williams and Hazer (1986) suggested a two-stage SEM validation procedure, in which the fit of the measurement model is examined first, and then the structural model is examined when the fit of the measurement model reaches an acceptable standard. To use SEM as a measurement method, a theoretical model is proposed and the hypothesis of the relationship between potential variables is described before performing the two-stage SEM validation.

Research Results

Following Anderson and Gerbing (1988), this study conducts a two-stage SEM analysis. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was applied to measure the model and analyze data. SPSS and SmartPLS were used for statistical analysis. The results are described in the following sections, including descriptive statistics, reliability and validity, and path analysis of the model.

Descriptive Statistics

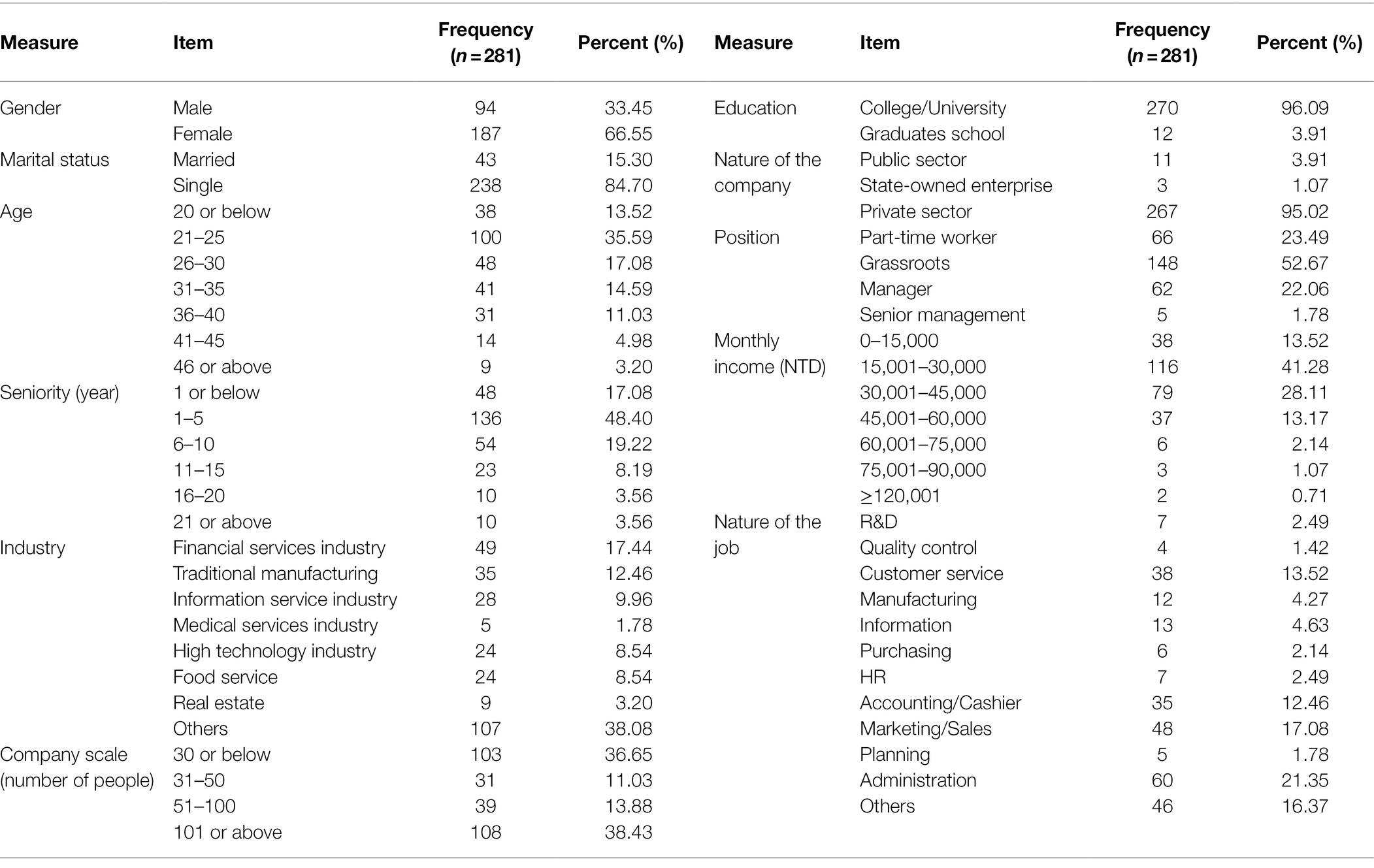

Before the final questionnaire was distributed, this study first had experts check quality of the questionnaire and then conducted the investigation. A total of 315 questionnaires were collected, 281 questionnaires are valid (89.21%). Descriptive statistics of the valid samples are shown in Table 2. There were more females (66.55%) than males (33.45%); more single (84.70%) than married (15.30%); respondents aged 21–25 were the largest group (35.59%), followed by those 26–30 (17.08%).; the highest percentage education level is college/university (96.09%); those with work experience of 1–5 years were the largest group (48.40%); respondents with an average monthly income of NT$15,001–30,000 accounted for 41.28%; some respondents were unsure which industry their company belonged to, so “others” was the largest group (38.08%); most companies were private enterprises (95.02%); most of their positions were grassroots (52.67%); the type of job accounting for the largest proportion was administrative (21.35%).

Reliability, Validity, and Model Fit

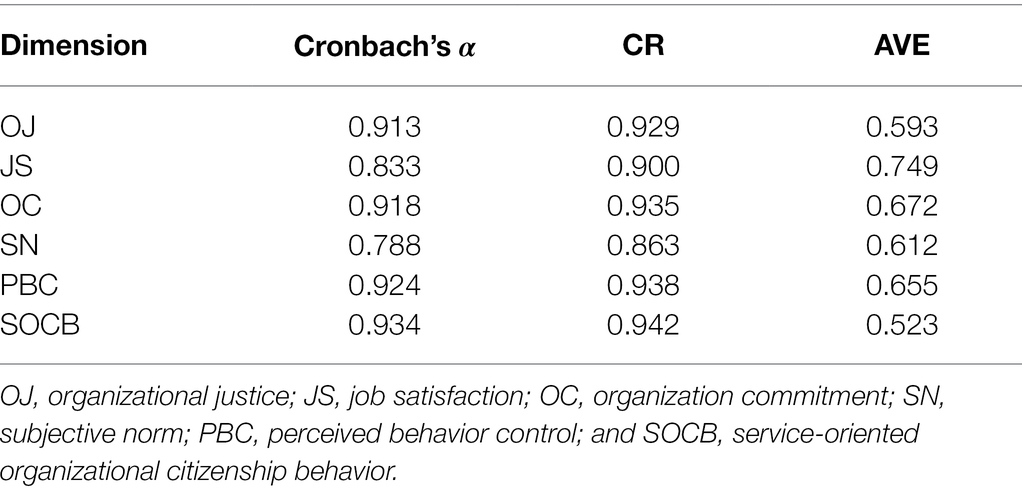

Each dimension and question was analyzed to evaluate the reliability, validity, and significance of estimated parameters for the observed variables. To establish the relationship between measurement indicators and potential variables, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) tested the validity of the questionnaire (measurement indicators), and convergent validity and discriminant validity examined the reliability of each dimension. The results of reliability and validity analysis are shown in Table 3.

Reliability refers to whether the measurement results reach consistency and stability, indicating the accuracy and reliability of the questionnaire. Consistency refers to whether the tests between internal questions are consistent with each other. Stability refers to whether the scores of the tests are consistent at different points in time. Reliability analysis uses Cronbach’s α and Composite Reliability (CR) to measure stability and consistency of a facet. Generally, the value of Cronbach’s α must be greater than 0.6, otherwise the scale must be redone. The overall Cronbach’s α value must be greater than 0.7 to have credibility, and a Cronbach’s α value of 0.8–0.9 is ideal, indicating a high degree of reliability (Nunnally, 1978). If the CR value of the potential variable is higher, the measurement variable is highly correlated, and the internal consistency is higher, which means that the item can effectively measure the potential variable, so the dimension has credibility. Fornell and Larcker (1981) recommends that a CR should be greater than 0.6, and it should be greater than 0.7 for a high degree of credibility (Hair et al., 1998). Table 3 shows that Cronbach’s α and CR for each dimension and item are higher than the recommended value, indicating good internal consistency.

Convergent validity refers to the degree of aggregation or correlation between multiple indicators (i.e., questions) that measure a single dimension. Cronbach’s α, average variances extracted (AVE), and CR were used as the basis for evaluating convergent validity (Hair et al., 1998). The AVE value is used to calculate the explanatory power of the potential variables to the variation of each measurement variable. Examine the reliability Higher AVEs indicate higher reliability and convergent validity. The AVEs are all higher than the recommended value of 0.7, so they have good convergence validity.

In addition, measurement of the items is based on relevant literature and theories, and questionnaires or measurement items used by experts and scholars are cited, and the content of this research is designed and modified into appropriate semantics. Therefore, this research questionnaire has considerable content validity.

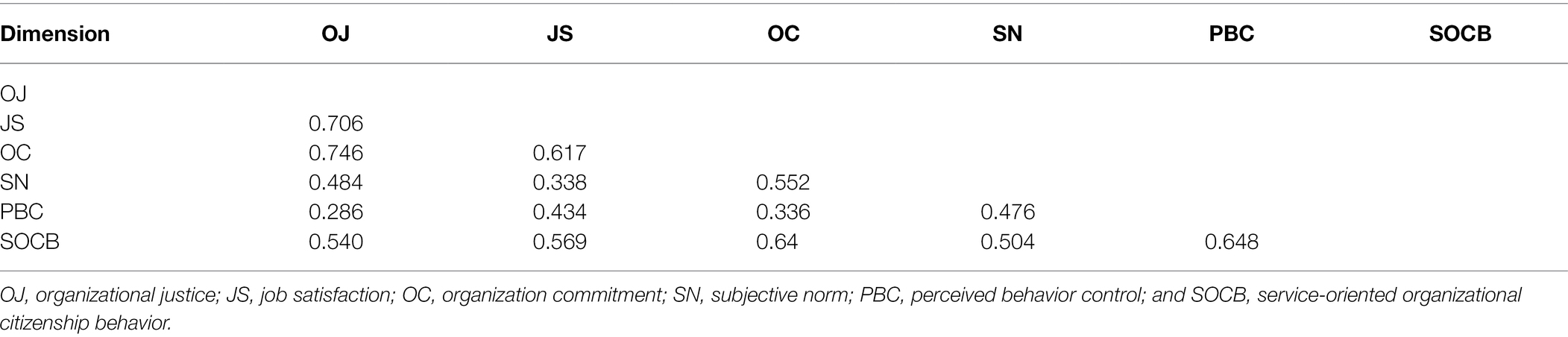

Discriminatory validity confirms that the dimensions (potential variables) are indeed different. The Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) was adopted to test discriminant validity. Hair et al. (2021) proposed that HTMT values less than 0.90 indicate discriminant validity between dimensions. Table 4 shows that all values between two dimensions were less than 0.90. Thus, the dimensions in this study have discriminant validity.

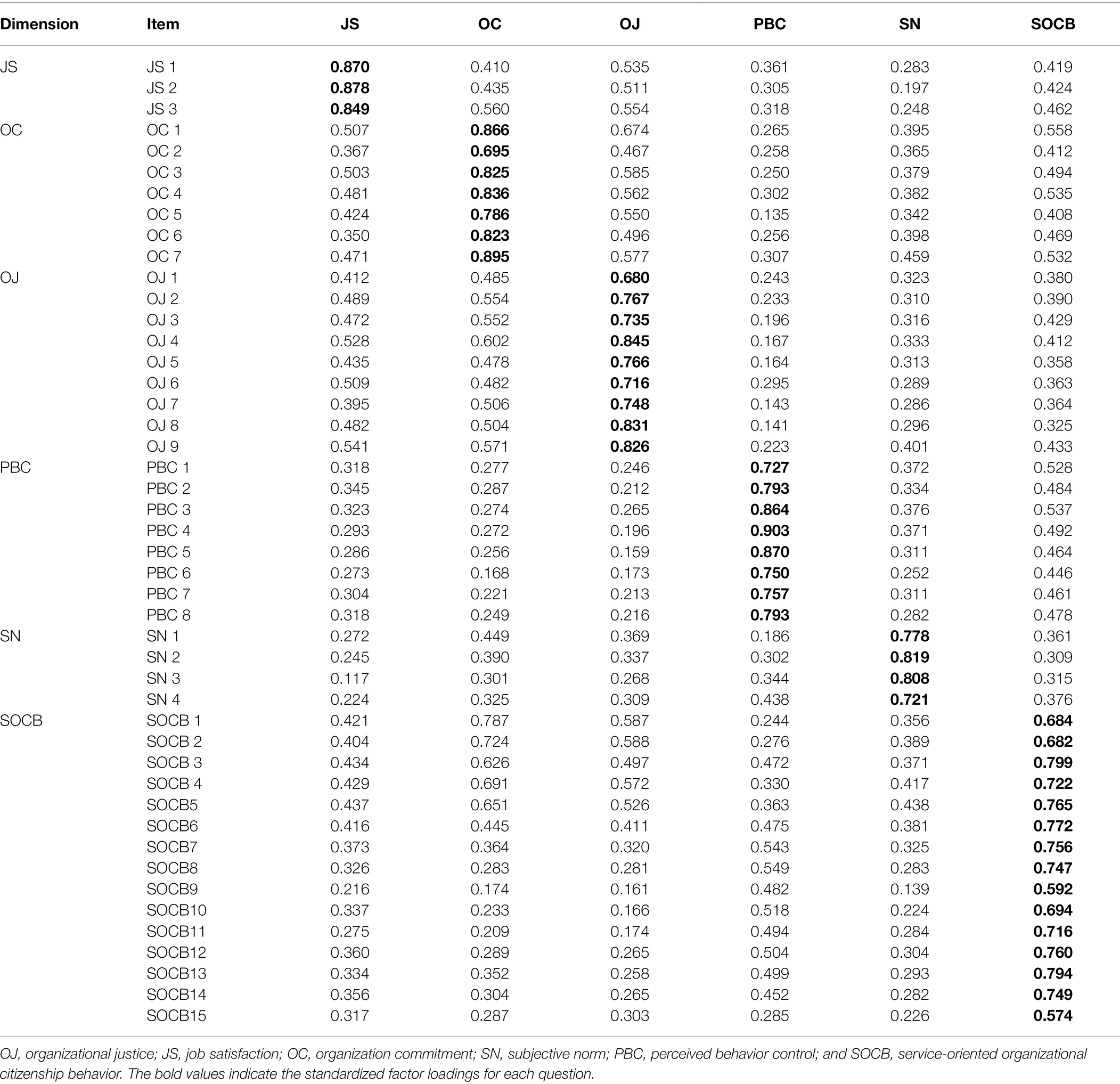

Furthermore, cross loadings can also be used to examine the discriminant validity to test the relationship between each item and different constructs. When items of one dimension are low related to other dimensions, there is discriminant validity between the dimensions. Conversely, in the cross-loading table, when the standardized factor loading of a question in a dimension should be more correlated with the other dimensions, it indicates discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2021). Results of the cross-loadings in this study met these criteria (see Table 5), indicating that the questions designed for this study had good discriminant validity.

When collecting questionnaires, an individual respondent may have cognitive similarity with the information, leading to common method variance (CMV). To avoid this problem, this study used anonymous surveys, concealed the meaning of questions, split up questions for each variable, and included reverse questions. Table 4 also shows that constructs of this study have construct validity, so the results are not significantly affected by CMV. Furthermore, this study uses the Harman’s One-Factor Test proposed by Podsakoff and Organ (1986) to test the severity of CMV. Explained variance of the marker variable was 34.105%, indicating that it was not related to the potential constructs. In conclusion, there was no severe CMV.

Final, as mentioned earlier, this study applies PLS-SEM to the analysis. Tenenhaus et al. (2004) proposed a global goodness of fit (GoF) for PLS-SEM to measure model fit. The equation is as follows, and the GoF is a value between 0 and 1. Wetzels et al. (2009) divided GoF into three levels, small (0.1), medium (0.25), and large (0.36).

This study put AVE (see Table 3) and R2 (see Figure 2) into this equation and obtained GoF = 0.460. This value is greater than 0.36, indicating that the model fits is significant and acceptable.

Structural Equation Model Analysis

Structural equation model analysis (SEM) is based on the regression technique of multivariate technology, which conducts path analysis for potential variables to test fitness of the structural model. First, the items are reduced to fewer measurement indicators, the path is analyzed, the causal relationship between the variables is explored, and the various hypotheses are verified (MacCallum et al., 1994). Thus, SEM is based on a few measurement indicators to analyze various dimensions (potential variables) and evaluate causality.

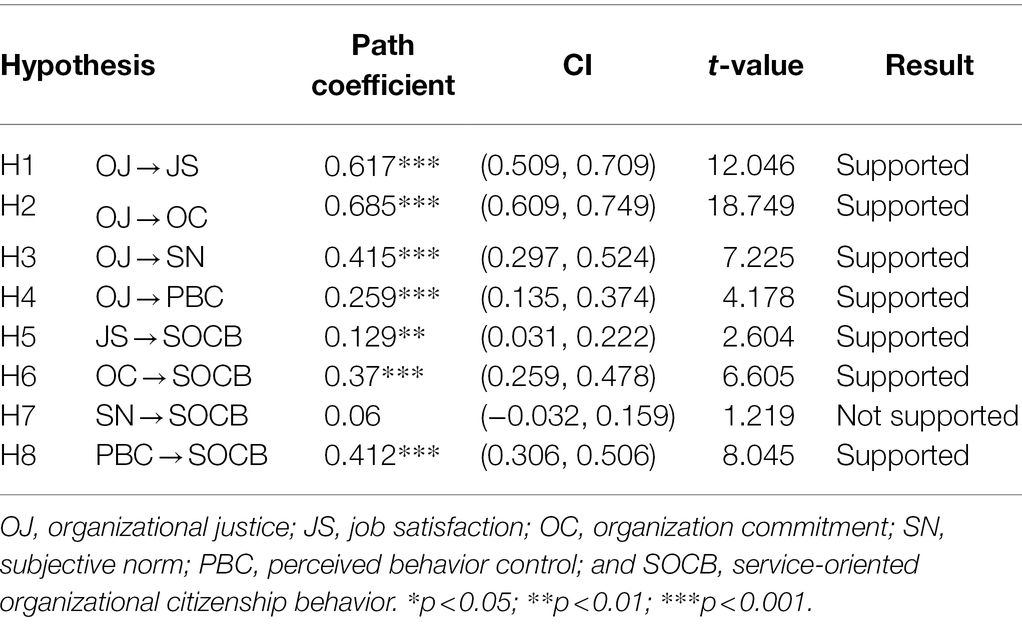

Next, a model structure is established using SmartPLS for SEM analysis to explore relationships between the various dimensions. The result of path analysis is expressed by a path coefficient, which is divided into direct and indirect effects. Direct effect is the path coefficient from the independent variable to the dependent variable; indirect effect is the sum of products of the path coefficients from the independent variable to the dependent variable through the mediator. Effects of the overall potential variables are summarized in Table 6, and the results of the path analysis are shown in Figure 2. Except that H7 has non-significant effect, the other hypotheses are supported (see Table 6). Moreover, the explanatory power (R2) is presented in Figure 2 (job satisfaction: R2 = 0.381; organizational commitment: R2 = 0.469; subjective norm: R2 = 0.172; perceived behavioral control: R2 = 0.067; service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: R2 = 0.560), which is the percentage of the explained variance of the exogenous variables versus the endogenous variables.

Q-square is used to verify whether the model has predictive relevance. When Q-square is greater than 0, it indicates that the model has predictive relevance. In this study, Q-square values are all greater than 0 (job satisfaction: Q2 = 0.281; organizational commitment: Q2 = 0.311; subjective norm: Q2 = 0.100; perceived behavioral control: Q2 = 0.043; service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: Q2 = 0.287), so the model has predictive relevance.

Finally, this study adopts bootstrapping, a method of resampling, to check the indirect effect according to the recommendation of Shrout and Bolger (2002). The indirect effect is significant if the value of p is less than 0.05 and the CI does not contain 0. Three mediation effect s are supported in this study (see Table 7), including (1) organizational justice → job satisfaction → service-oriented OCB; (2) organizational justice → organizational commitment → service-oriented OCB; and (3) organizational justice → perceived behavior control → service-oriented OCB. In short, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and perceived behavior control have significant mediation effects.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the research model above, this section further discusses the findings, describes management implications from the study findings, and suggests future research directions.

Discussion

This study uses the conceptual framework of the DTPB to examine the impact of organizational justice on service-oriented employees OCB. Because this framework focuses on the discussion of behavioral intentions, the psychological impact of organizational justice must be reflected in behavioral performance. The model is discussed based on multi-dimensional factors, which are suitable for explaining and testing the purpose of this study.

The potential independent variables of organizational justice include procedural justice, interactional justice, and distributive justice. Employees want to be valued in their organization and expect good interpersonal relationships. If supervisors can respect and treat their subordinates fairly and peers can respect each other, employees will not have a feeling of unfairness, and have more retention commitment and work harder for the organization’s goal. In addition, if employees receive reasonable remuneration, they feel satisfied and willing to work hard. But if they feel they are exploited, they adjust self-efficacy and put less effort into their work. If employees think that they will get the same reward no matter whether they work hard or not, they will not work hard, thus lowering their self-worth commitment. If employees feel extreme unfairness and are unable to adjust, they may have diverging values or leave their jobs. Thus, the psychological factor of organizational justice is an important factor affecting behavior intention, and this study seeks to clarify the impact of organizational justice on service-oriented OCB. If an organization can better understand the perceptions of employees, it can formulate more appropriate management strategies.

This study first discusses the impact of organizational justice on perceived behavior control, subjective norms, and job attitudes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction). It then discusses the influence of perceived behavior control, subjective norms and job attitude on employees’ behavioral intentions. Service-oriented OCB is an extension of OCB and, as a common behavior in organizations, is the most appropriate way to explore current social situations. This study finds that organizational justice has a significant and positive effect on perceived behavior control, subjective norms, and job attitudes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction), indicating that employees attach great importance to organizational justice. In addition, the impacts of perceived behavior control, subjective norms, and job attitudes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction) on employee behavior were analyzed. Except for subjective norms, other factors have a significant and positive effect on behavioral intentions. This study argues that when organizations use cost-cutting measures (e.g., pay cuts, shorter working hours, unpaid leave), employees feel they are being treated unreasonably. When employees have the feeling of not being treated fairly, their work attitude (job satisfaction and organizational commitment) deteriorates and their confidence in doing their jobs decreases. Finally, these beliefs can impact their willingness to be proactive and enthusiastic in offering their services.

Job attitude includes organizational commitment and job satisfaction, which have important influences on attitude. Job satisfaction is a feeling of affirmation and being respected. Organizational commitment is the recognition that employees receive from the organization for their hard work. It influences the degree of effort and willingness of employees to stay in their jobs, and then forms the criteria for job attitude. The more affirmation employees receives from their organization, the more positive their job attitude will be. The subjective norms perceived by employees are not only influenced by ethics, but also by organizational norms. Because the behavior of employees should comply with organizational and ethical standards and must comply with the organization’s management system and rules.

Observing the findings in the previous section shows that job attitudes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction) have a significant and positive impact on service-oriented OCB. This means that employees with a good job attitude will be able to generate positive behaviors such as maintaining the organization’s image and providing enthusiastic service to customers. Furthermore, when employees are confident in their abilities to complete their work, they are more willing to take the initiative to provide good service to customers and interact with customers enthusiastically. When employees act as service staff and provide good service quality, customers will have a good impression of the organization and be willing to return, increasing profits of the organization. In addition, subjective norms are that employees comply with the norms of organization and ethics, and loyally provide consistent and standardized service quality to satisfy customers, so customers will be treated equally. Employees also play an intermediate role between the organization and customers and provide effective external publicity. Thus, employees with good subjective norms will also develop spontaneous OCB.

In service-oriented OCB, the main behavioral performance of employees is reflected in participation, service delivery and loyalty. For example, an employee’s sense of responsibility to the organization is a sign of loyalty. Proper service delivery means that employees will comply with organizational norms and provide consistent and standardized service quality to satisfy customers. Finally, participation means that employees provide excellent service that is spontaneous and goes beyond the norm. In addition, according to the theory of service profit chain, employee feedback increases the organization’s profits. But spontaneous feedback from employees is not easy, so an organization needs to recruit new members and increase training costs (Heskett et al., 1994). Hence, this study explores the influencing factors of service-oriented OCB by using DTPB. Empirical results show that perceived behavior control and job attitudes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction) affect service-oriented OCB. Nevertheless, these three factors are also affected by organizational justice. This study further verifies that organizational justice affects service-oriented OCB through perceived behavior control and job attitudes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction). Thus, these factors have mediation effects.

Management Implications

This study examines this psychological perception of organizational justice to clarify the importance of organizational justice to organizations. For organizations to create profits, they must maintain their stability, and retaining good talent by reducing the turnover rate is important for organizational stability. Furthermore, a low staff turnover rate can reduce operation costs. Service-oriented OCB is the behavior of employees when they spontaneously work hard, beyond the scope of work norms. Employees are motivated to develop OCB, which is a continuous act of loyalty, and employees who perceive that the organization is treating them fairly are more likely to develop OCB. According to the theory of service profit chains, an organization’s profits can be increased by employee feedback. Managers hope that employees are willing to give back actively if the organization treats the employees fairly. When employees think that their hard work will be rewarded by corresponding compensation, they spontaneously give more. This creates a positive cycle, increasing the organization’s profits. This study confirms that when employees appreciate that their organization is treating them fairly, their job attitude and perceived behavior control are improved, which in turn affects service-oriented OCB. This will enable the organization to develop better. The study also confirms that when employees appreciate that they are treated fairly by the organization, it affects their perceived behavior control and job attitude, which in turn affects service-oriented OCB. As a result, organizations that treat their employees fairly are more likely to receive active feedback from employees that enable the organization to develop better. When the organization achieves its profit targets, its employees will also receive fair and reasonable compensation, forming a win-win situation for the organization and employees.

Future Research and Suggestions

According to the research purpose, the respondents were employees in different industries, so this study could only understand some general perceptions of workers towards their organization. Consequently, this study proposes several future research directions. First, it is suggested that an overall assessment should be done for a single industry. Second, it is recommended that investigations be conducted at different points in time in the future, and there may be different findings. Third, more factors can be added to the evaluation, which may reveal more factors affecting the OCB to improve the organization-employee relationship, enhance the organization’s competitiveness, and create higher profits. Final, frontline service workers interact with customers. Zhu et al. (2021) studied the relationship between service satisfaction and customer citizenship behavior in e-tailing industry. Hence, this study suggests that this research framework can be used as a basis to discuss customer citizenship behavior in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

K-CT, Y-CL, and S-CC: conceptualization. TH and S-CC: methodology. T-HC, SK, and TH: validation; Y-CL and S-CC: formal analysis. Y-CL and S-CC: investigation. K-CT, T-HC, SK, TH, Y-CL, and S-CC: writing original draft preparation. TH, Y-CL, and S-CC: writing review and editing. Y-CL and S-CC: visualization. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). “Inequity in social exchange,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 2. ed. L. Berkowitz (New York: Academic Press), 267–299.

Aguiar-Quintana, T., Araujo-Cabrera, Y., and Park, S. (2020). The sequential relationships of hotel employees’ perceived justice, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviour in a high unemployment context. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 35:100676. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100676

Ajzen, I. (1985). “From intention to actions: a theory of planned behavior,” in Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior. eds. J. Kuhl and J. Beckman (Heidelberg: Springer), 11–39.

Ajzen, I. (1989). “Attitude structure and behavior,” in Attitude Structure and Function. eds. A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, and A. G. Greenwald (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 241–274.

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1975). A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 82, 261–277. doi: 10.1037/h0076477

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Alexander, S., and Ruderman, M. (1987). The role of procedural and distributive justice in organizational behavior. Social Justice Research. 1, 177–198. doi: 10.1007/BF01048015

Anderson, J. C., and Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103, 411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Arvey, R. D., Bouchard, T. J., Segal, N. L., and Abraham, L. M. (1989). Job satisfaction: environmental and genetic components. J. Appl. Psychol. 74, 187–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.74.2.187

Bagozzi, R. P. (1981). Attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a test of some key hypotheses. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 41, 607–627. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.41.4.607

Bagozzi, R. P. (1982). A field investigation of causal relations among cognitions, affect, intentions, and behavior. J. Mark. Res. 19:562. doi: 10.2307/3151727

Bagozzi, R. P. (1983). Issues in the application of covariance structure analysis: a further comment. J. Consum. Res. 9:449. doi: 10.1086/208939

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., and Iverson, R. D. (2003). High-quality work, job satisfaction, and occupational injuries. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 276–283. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.276

Bettencourt, L. A., and Brown, S. W. (1997). Contact employees: relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. J. Retail. 73, 39–61. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90014-2

Bettencourt, L. A., Gwinner, K. P., and Meuter, M. L. (2001). A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 29–41. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.29

Bies, R. J., and Moag, J. S. (1986). “Interactional justice: communication criteria of fairness,” in Research on Negotiation in Organization, Vol. 1. eds. R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, and M. H. Bazerman (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press), 199–218.

Bock, G. W., and Kim, Y. G. (2002). Breaking the myths of rewards: an exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 15, 14–21. doi: 10.4018/irmj.2002040102

Borman, W. C., and Motowidlo, S. M. (1993). “Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance,” in Personnel Selection in Organizations, Vol. 48. eds. N. Schmitt and W. C. Borman (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass), 299–337.

Buchanan, B. (1974). Building organizational commitment: the socialization of managers in work organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 19, 533–546. doi: 10.2307/2391809

Chemseddine, B. A., and Kamel, M. O. U. L. O. U. D. J. (2021). Using the theory of planned behavior to explore employees intentions to implement green practices. Dirassat J. Econ. Issues 12, 641–659.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., and Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 425–445. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425

Currivan, D. B. (1999). The causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in models of employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 9, 495–524. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4822(99)00031-5

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13:319. doi: 10.2307/249008

Davis, R. D., Bagozzi, R. P., and Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical model. Manag. Sci. 35, 982–1003. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

Dirks, K. T., and Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 611–628. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611

Dittrich, J. E., and Carrell, M. R. (1979). Organizational equity perceptions, employee job satisfaction, and department absence and turnover rates. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 24, 29–40. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(79)90013-8

Duan, L. H. (2022). An extended model of the theory of planned behavior: an empirical study on entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial behavior in college students. Front. Psychol. 12:627818. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.627818

Dunham, R., and Herman, J. (1975). Development of a female faces scale for measuring job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 60, 629–631. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.60.5.629

Edwards, J. R. (1991). “Person-job fit: a conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique,” in International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 6. eds. C. L. Cooper and I. T. Robertson, (Hoboken, New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons), 283–357.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., and Sowa, D. (1986). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 71:500. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., and Kraimer, M. L. (2006). Justice and leader-member exchange: the moderating role of organizational culture. Acad. Manag. J. 49, 395–406. doi: 10.5465/amj.2006.20786086

Ferris, K. R., and Aranya, N. (1983). A comparison of two organizational commitment scales. Pers. Psychol. 36, 87–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1983.tb00505.x

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Folger, R., and Konovsky, M. A. (1989). Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 32, 115–130. doi: 10.2307/256422

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

George, J. M. (1991). State or trait: effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 76, 299–307. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.299

Greenberg, J. (1990). Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: the hidden cost of pay cuts. J. Appl. Psychol. 75, 561–568. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.561

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., and Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis With Readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2021). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Harrison, D. A., Newman, D. A., and Roth, P. L. (2006). How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Acad. Manag. J. 49, 305–325. doi: 10.5465/amj.2006.20786077

Hasyim, A. F., and Palupiningdyah, P. (2021). Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating roles of organizational commitment and leader member exchange. Manag. Anal. J. 10, 1–10. doi: 10.15294/maj.v10i1.43916

Heskett, J. L., Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, W. E. Jr., and Schlesinger, L. A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harv. Bus. Rev. 4, 35–45. doi: 10.3233/WOR-1994-4106

Hogan, J., Hogan, R., and Busch, C. M. (1984). How to measure service orientation. J. Appl. Psychol. 69, 167–173. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.167

Ibragimova, B. (2006). Propensity for Knowledge Sharing: An Organizational Justice Perspective. University of North Texas.

Islam, T., Mahmood, K., Sadiq, M., Usman, B., and Yousaf, S. U. (2020). Understanding knowledgeable workers’ behavior toward COVID-19 information sharing through WhatsApp in Pakistan. Front. Psychol. 11:572526. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572526

Jaramillo, F., Mulki, J. P., and Marshall, G. W. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational commitment and salesperson job performance: 25 years of research. J. Bus. Res. 58, 705–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.10.004

Jin, Y., Cheng, L., Li, Y., and Wang, Y. (2021). Role stress and prosocial service behavior of hotel employees: a moderated mediation model of job satisfaction and social support. Front. Psychol. 12:698027. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.698027

Jung, H. S., and Yoon, H. H. (2015). The impact of employees’ positive psychological capital on job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors in the hotel. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 27, 1135–1156. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-01-2014-0019

Kang, S.-E., Park, C., Lee, C.-K., and Lee, S. (2021). The stress-induced impact of COVID-19 on tourism and hospitality workers. Sustainability 13:1327. doi: 10.3390/su13031327

Kreitner, R., and Kinichi, A. (1995). Organizational Behavior. 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Richard D. Irwin, Inc.

Lawler, E. E., and Hall, D. T. (1970). Relationship of job characteristics to job involvement, satisfaction, and intrinsic motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 54, 305–312. doi: 10.1037/h0029692

Lee, C., and Green, R. T. (1991). Cross-cultural examination of the Fishbein behavioral intentions model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 22, 289–305. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490304

Liebermann, S., and Hoffmann, S. (2008). The impact of practical relevance on training transfer: evidence from a service quality training program for German bank clerks. Int. J. Train. Dev. 12, 74–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2419.2008.00296.x

Liker, J. K., and Sindi, A. A. (1997). User acceptance of expert systems: a test of the theory of reasoned action. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 14, 147–173. doi: 10.1016/S0923-4748(97)00008-8

Lu, L., Siu, O. L., and Lu, C. Q. (2010). Does loyalty protect Chinese workers from stress? The role of affective organizational commitment in the greater China region. Stress. Health 26, 161–168. doi: 10.1002/smi.1286

Luo, Y. Z., Xiao, Y. M., Ma, Y. Y., and Li, C. (2021). Discussion of students’ E-book reading intention with the integration of theory of planned behavior and technology acceptance model. Front. Psychol. 12:752188. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.752188

MacCallum, R. C., Roznowski, M., Mar, C. M., and Reith, J. V. (1994). Alternative strategies for cross-validation of covariance structure models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 29, 1–32. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2901_1

Martin, C. L., and Bennett, N. (1996). The role of justice judgments in explaining the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Group Org. Manag. 21, 84–104. doi: 10.1177/1059601196211005

Masterson, S. S., Lewis, K., Goldman, B. M., and Taylor, M. S. (2000). Integrating justice and social exchange: the differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 43, 738–748. doi: 10.2307/1556364

Moon, M. J. (2000). Organization com mitment revisited in new public management: motivation, organizational culture, sector and managerial level. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 24, 177–194. doi: 10.2307/3381267

Moorman, R. H. (1991). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J. Appl. Psychol. 76, 845–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.6.845

Morris, J. H., and Sherman, J. D. (1981). Generalizability of an organizational commitment model. Acad. Manag. J. 24, 512–526. doi: 10.2307/255572

Morrow, P. C. (1983). Concept redundancy in organizational research: the case of work commitment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 8, 486–500. doi: 10.2307/257837

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., and Steer, R. M. (1982). Employee-Organization Linkages. NY: Academic Press.

Murphy, G., Athanasou, J., and King, N. (2002). Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: a study of Australian human-service professionals. J. Manag. Psychol. 17, 287–297. doi: 10.1108/02683940210428092

Niehoff, B. P., and Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 36, 527–556. doi: 10.2307/256591

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Solider Syndrome, Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Parasuraman, A. V., Zeithaml, V. A., and Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 69, 140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(05)80007-7

Podsakoff, P. M., and Organ, D. W. (1986). Self reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manag. 12, 531–544. doi: 10.1177/014920638601200408

Porter, K. R., Puck, T. T., Hsie, A. W., and Kelley, D. (1974). An electron microscope study of the effects of dibutyryl cyclic AMP on Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cell 2, 145–162. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90089-0

Radaelli, G., Lettieri, E., and Masella, C. (2015). Physicians’ willingness to share: a TPB-based analysis. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 13, 91–104. doi: 10.1057/kmrp.2013.33

Rahman, A., Shahzad, N., Mustafa, K., Khan, M. F., and Qurashi, F. (2016). Effects of organizational justice on organizational commitment. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 7, 196–209. doi: 10.1108/JGR-06-2016-0015

Robbins, S. P. (1993). Organizational Behaviour, Concepts, Controversies and Applications. (6th Ed.). Englewood Cliffs. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Robbins, S. P. (1996). Organizational Behavior: Concept, Controversier, Applications-7/E. Hoboken, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Ruangkanjanases, A., You, J. J., Chien, S. W., Ma, Y., Chen, S. C., and Chao, L. C. (2020). Elucidating the effect of antecedents on consumers’ green purchase intention: an extension of the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 11:1433. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01433

Saifi, I. A., and Shahzad, K. (2017). The mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 34, 233–244. doi: 10.31217/p.34.2.4

Salancik, G. R. (1977). “Commitment and the control of organizational behavior and belief,” in New Directions in Organizational Behavior. eds. B. Staw and G. Salancik (Chicago: St. Clair Press), 1–54.

Schermerhorn, J. R. (1996). Management and Organizational Behavior Essentials. New York: John Wiley.

Schneider, B., and Bowen, D. E. (1985). Employee and customer perceptions of service in banks: replication and extension. J. Appl. Psychol. 70, 423–433. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.70.3.423

Scholl, R. W., Cooper, E. A., and McKenna, J. F. (1987). Referent selection in determining equity perceptions: differential effects on behavioral and attitudinal outcomes. Pers. Psychol. 40, 113–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb02380.x

Schwepker, C. H. Jr. (2001). Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the salesforce. J. Bus. Res. 54, 39–52. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00125-9

Sheldon, M. E. (1971). Investments and involvements in mechanisms producing commitment to the organization. Adm. Sci. Q. 16, 143–150. doi: 10.2307/2391824

Shimp, T. A., and Kavas, A. (1984). The theory of reasoned action applied to coupon usage. J. Consum. Res. 11:795. doi: 10.1086/209015

Shrout, P. E., and Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., and Aguilar-Vafaie, M. E. (2002). A comparative study of perceived job stressor sources and job strain in American and Iranian managers. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 51, 446–457. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00102

Steers, R. M. (1977). Antecedents and outcomes of organization commitment. Adm. Sci. Q. 22, 46–56. doi: 10.2307/2391745

Steers, R. M., and Black, J. S. (1994). Organizational Behavior. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers. P. 87.

Su, F., Cheng, D., and Wen, S. (2019). Multilevel impacts of transformational leadership on service quality: evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 10:1252. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01252

Taylor, S., and Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: a test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 6, 144–176. doi: 10.1287/isre.6.2.144

Tenenhaus, M., Amato, S., and Esposito Vinzi, V. (2004). A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modeling. in Proceedings of the XLII SIS Scientific Meeting; June 9–11, 2004; Padova: CLEUP. 739–742.

Thibaut, J., and Walker, I. (1975). Procedural Justice: A Psycholgical Analysis, Eribaum, Hillsdale, NJ. 26, 1271.

Torlak, N. G., Kuzey, C., Sait Dinç, M., and Budur, T. (2021). Links connecting nurses’ planned behavior, burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Work. Behav. Health 36, 77–103. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2020.1862675

Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., and Parks, J. M. (1995). “Extra-role behaviors: in pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters),” in Research in Organizational Behavior, Greenwich. Vol. 15. eds. B. M. Staw and L. L. Cummings, (CT: JAI Press), 193–195.

Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., England, G. W., and Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., and Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 33:177. doi: 10.2307/20650284

Whyte, W. H. (1956). The organization man. New York: Simon and Schuster, work commitment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 11, 311–500. doi: 10.2307/258462

Williams, L. J., and Hazer, J. T. (1986). Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: a reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 219–231. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.219

Wong, A. K. F., Kim, S. S., Kim, J., and Han, H. (2021). How the COVID-19 pandemic affected hotel employee stress: employee perceptions of occupational stressors and their consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 93:102798. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102798

Zahednezhad, H., Hoseini, M. A., Ebadi, A., Farokhnezhad Afshar, P., and Ghanei Gheshlagh, R. (2021). Investigating the relationship between organizational justice, job satisfaction, and intention to leave the nursing profession: a cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 1741–1750. doi: 10.1111/jan.14717

Keywords: theory of planned behavior, organizational justice, job attitude, structural equation modeling, service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior

Citation: Tsai K-C, Chou T-H, Kittikowit S, Hongsuchon T, Lin Y-C and Chen S-C (2022) Extending Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Service-Oriented Organizational Citizen Behavior. Front. Psychol. 13:839688. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.839688

Edited by:

Michael Yao-Ping Peng, Foshan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Hao Ji, Beijing Union University, ChinaI-Hsien Ting, National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Copyright © 2022 Tsai, Chou, Kittikowit, Hongsuchon, Lin and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tung-Hsiang Chou, c2FtQG5rdXN0LmVkdS50dw==; Tanaporn Hongsuchon, dGFuYXBvcm4uaEBjaHVsYS5hYy50aA==; Yu-Chun Lin, eXVjaHVubGluQG5rdXN0LmVkdS50dw==

Kuang-Chung Tsai1

Kuang-Chung Tsai1 Tanaporn Hongsuchon

Tanaporn Hongsuchon Yu-Chun Lin

Yu-Chun Lin Shih-Chih Chen

Shih-Chih Chen