94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 19 May 2022

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.839266

This article is part of the Research TopicLeadership, Diversity and Inclusion in OrganizationsView all 15 articles

The ability to transform on a regular basis is critical in the effort to adapt to external challenges; however, changes to an organization’s fundamental characteristics may increase the likelihood of failure. Because of this, organizational restructuring efforts appear to engender cynicism, which appears to be one of the most significant obstacles facing contemporary businesses, particularly in this area. Organizational inertia is the term used to describe this aversion to change, as well as the desire to maintain the current status quo. A new organizational culture capable of combating the incidence of organizational stagnation is required by massive social, economic, and technological difficulties, and firms that employ the concept of empowering leadership will be able to meet these challenges. For the purposes of this study, a framework for discussing the phenomena of organizational cynicism was developed and implemented.

In a constantly changing business environment, long-term success necessitates not just the ownership of difficult-to-replicate assets, but also the possession of one-of-a-kind and outstanding dynamic talents. Several scholars claim that this competitive advantage will be realized in the area of human capital management if the organization is able to design the connectivity of human resources inside it under the auspices of a high-performing work system (Quratulain and Al-Hawari, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2022). Organizations strive to adjust their strategy in order to face the challenges posed by changes in the company life cycle (Santiago, 2015). Organizations that are able to adapt to new markets, processes, and technology are known as entrepreneurial enterprises (Sharma et al., 2012; Santiago, 2015). For firms confronting changes in the organizational life cycle, innovation appears to be a sensible course of action. Organizations, on the other hand, do not always innovate, and some can fall into a condition of immobility. In family enterprises, inertia is also common (Chirico and Nordqvist, 2010; Chirico and Salvato, 2016). Inertia increases in families that stay closed and paternalistic. The business family becomes rigid and resistant to change as a result of the paternalistic mindset, whereas the entrepreneurial drive encourages innovation (Chirico and Nordqvist, 2010). The refusal to modify the core of the organization is referred to by Mallette and Hopkins (2013) as structural inertia, biased management cognition (Gilbert, 2005). Cynicism about change and even hostility to change stems from the organization’s closed, paternalistic culture and refusal to change its essential values. In addition, some research have found a link between cynicism and organizational inertia. Huang et al. (2013) claimed that inertial organizational conditions will impede the implementation of organizational strategy, making organizational sustainability uncertain (DeCelles et al., 2013; Fernhaber and Li, 2013).

According to research on organizational inertia, there is a significant internal propensity towards similarity, which can inhibit employees’ ability to produce novel ideas (AlKayid et al., 2022). Visionary leadership (AlKayid et al., 2022), flexible budgeting (Oyadomari et al., 2018), skewed management cognition, a lack of incentive to change, or challenges in redeploying business resources (Gilbert, 2005; Hoppmann et al., 2019) are some of the antecedent variables. The character of cynicism as a serious barrier to change (Reichers et al., 1997), cynicism as something that develops, is destructive, and is possible to sabotage (DeCelles et al., 2013), and the reluctance of cynical employees to participate in change are all factors considered in this study (Islam et al., 2020). Cynical personnel have a passive attitude toward change, which leads to organizational stagnation in the form of incapacity to implement internal adjustments in the face of large external changes (Gilbert, 2005).

In recent years, the topic of organizational cynicism has become an intriguing subject for further exploration. Given the strong correlation between cynicism and an employee’s professionalism (Bang and Reio, 2017), cynicism, particularly in Indonesia, is worth investigating further. Indonesia is a collectivist country with a high power distance (Aslam et al., 2016), and its response to cynicism is quite unique, promoting tolerance and respect for others and concealing cynicism within an organization. Milliken et al. (2003) characterized cynicism as “silent cynicism” in a study they conducted.

When an organization changes, the comfort and stability of the workplace are frequently disrupted. This is because when an organization changes, it creates uncertainty and discomfort in the work environment, which contributes to employee cynicism (Oreg, 2006; Aslam et al., 2016). Numerous studies on employee behavior in response to organizational change have been conducted over the last few decades (Reichers et al., 1997; Wanous et al., 2000; Brown and Cregan, 2008; Grama and Todericiu, 2016). The study agrees that employee cynicism will have an effect on the organization’s performance (Bouckenooghe et al., 2014, 2021; Cinite and Duxbury, 2018).

According to several studies, it is believed that by involving employees, an organization’s cynicism can be reduced. Numerous studies indicate that an organization’s cynicism can be reduced by involving employees in the planning process, conducting performance evaluations, and being willing to admit mistakes (Ahearne et al., 2005; Stanley et al., 2005). Employees who feel empowered are more likely to take proactive measures and support the change process; additionally, superiors must demonstrate their recognition of employees’ competence, as this fosters employees’ confidence and security in the organization by allowing them to work independently and providing support. Increasing the capacity of an organization in order to ensure its long-term viability (Jung et al., 2020).

There is a wealth of research demonstrating the link between HPWS and organizational performance. This study will look at HPWS from a variety of angles. The study’s link between strategic human resource management and psychology is in the establishment of empowering leadership mechanisms to manage cynicism and organizational inertia. Confidence in the organization and senior management is increased by preparing followers to accept potential negative experiences during any transformation effort (Zhang and Bartol, 2010; Van Bockhaven et al., 2015; Hao et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2018). As a result, empowered leadership can assist followers in discovering purpose in their job and establishing a sense of security within the organization, while simultaneously fostering creativity and lowering hazardous defensive behavior. As a result, empowering leaders has a beneficial effect on their followers’ risk-taking behavior (Jung et al., 2020). Empowering leaders through development support for the technical and managerial skills required of followers enables followers to initiate change-related activities (Lorinkova and Perry, 2017; Kundu et al., 2019).

This research employs a social cognitive theory approach, which Bandura (1997) asserts consistently demonstrates successful self-leadership abilities and other desirable work-related behaviors. The learning model is a component of social cognition theory and the idea of triadic reciprocity, which asserts that an individual’s cognitive processes, behavior, and environmental impacts are all interconnected (Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014; Newman et al., 2018). Empowerment improves the work environment and increases individual motivation to work indirectly by providing autonomy and development support to lower levels in an organization where decisions can be made, particularly in terms of implementing creative and innovative changes that address business needs. Will eventually result in the creation of a sustainable business (Turi et al., 2019; Lin and Ling, 2021). The interaction of the three triadic reciprocal components is predicted to expand the usage of social cognition theory in the setting of family business. Three components: personal (cynicism about change as a negative attitude among organizational members), environmental (empowering leadership as a positive environment the leader attempts to create), and behavioral (cynicism about change as a negative attitude among organizational members; organizational inertia as a form of behavior after going through the learning process). In this context, empowering leadership is a variable that reduces cynicism and reduces the impact of cynicism on organizational inertia changes in family businesses (Li and Yuan, 2017; Meng-Hsien et al., 2018).

“Social Cognitive Theory” is a foundational theoretical framework that has been shown to be effective in comprehending and explaining behavior (Bandura, 1997). The individual (person), the environment (environment), and individual behavior (behavior) all have a reciprocal link, which is referred to as (triadic) reciprocal determinism (or triadic reciprocal model of causality; Bandura, 1997; Eslami and Melander, 2019). The essence of this theory is that humans acquire the ability to model through observation and imitation, which they subsequently use when behaving or acting. Humans react by utilizing their capacity for thought, symbolism, and anticipation (outcome reaction). It is critical to emphasize the relationship between individual characteristics, group values, attitudes, and behavior throughout organizational change (Bandura, 1997). This theory is predicated on the following assumptions: humans view humans intrinsically, not as good or bad, but as a result of experience with the potential for all kinds of behavior; humans are capable of conceptualizing and controlling their behavior; humans are capable of acquiring new behavior; and humans can influence the behavior of others just as their behavior is influenced by others (Ilgen et al., 2005; van Zundert et al., 2010) proposed four critical parts to this theory in order to explain it: observational learning (modeling), self-regulation, self-efficacy, and reciprocal determinism. Cynicism toward university changes develops when new obligations are not accompanied by equitable justice. The justice approach is supposed to be capable of fostering an environment conducive to learning, self-evaluation, and constructive behavior (Yim et al., 2017).

Cynicism is essentially the end result of a preceding process (Wanous et al., 2004; Grama and Todericiu, 2016; Schraeder et al., 2016; Bakari et al., 2019). According to Dean et al. (1998), there are five fundamental conceptualizations of cynicism: personality cynicism, societal or institutional cynicism, occupational cynicism, employee cynicism, and skepticism about organizational transformation. Cynicism is defined as a person’s lack of trust in others or their perception of others as dishonest, unsocial, immoral, ugly, or even vicious (Abugre, 2017; Rayan et al., 2018; Schmitz et al., 2018; Zeidan and Prentice, 2022). To be more precise, this research will refer to “cynicism about organizational change” as a moderate attitude toward future organizational changes that includes pessimism about their success, based on the perception that changes are prone to failure and the belief that change agents are incompetent (Wanous et al., 2004).

Wanous et al. (2004) coined the term “cynicism about organizational change,” which refers to a genuine loss of trust in change agents as a result of a history of change initiatives that were not fully or obviously effective. Additionally, because those who are cynical about organizational change may rationalize away knowledge gaps with the rationale that things must not have gone well, ineffectiveness and failure foster pessimistic attitudes, which further inhibit motivation to try again and become a significant impediment to change (James, 2005; Stanley et al., 2005; Abugre, 2017). It occurs despite the best intentions of those responsible for the change; even for rational decision makers who care about both employee well-being and their own reputations (Stanley et al., 2005; Walter and Cole, 2011; Neves, 2012). Cynicism about organizational change has previously been defined as a composite of three components: (a) pessimism about the success of future organizational change, (b) a dispositional attribution that those responsible for change are less motivated, incompetent, or both, and (c) a situational attribution (Wanous et al., 2000, 2004; Stanley et al., 2005). Pessimism is defined as an individual’s assessment of the likelihood that future organizational reforms will be effective. Meanwhile, dispositional attribution is concerned with the motivation and ability of organizational leaders, whereas situational attribution is concerned with circumstances beyond their control (Wanous et al., 2004). In the context of a family business, the term “successor” is not widely used. Leadership transformation is not a position that can be filled by random individuals, but rather by owner placement and direct appointment. Cynicism is critical to manage in this case because it is prone to occur in family businesses.

Additionally, the level of enthusiasm for new projects varies by individual and hierarchy. Changes may be viewed as fascinating challenges or as appropriate and timely responses to a changing environment; however, lower-level employees may regard them as incomprehensible and inexplicable actions because top-level management (parents in the business family) is typically conservative and lacks the capability to adapt to a changing environment (Brown and Cregan, 2008; Qian and Daniels, 2008; Scott and Zweig, 2016). Hourly workers expressed more cynicism about organizational change than executives did. Perhaps executives and managers believe they have a better understanding of upcoming plans and decision-making processes (Reichers et al., 1997). According to a previous empirical study conducted by (Stanley et al., 2005; Qian and Daniels, 2008; Grama and Todericiu, 2016; Bakari et al., 2019; Scott and Zweig, 2020), cynicism about organizational change is likely caused by a lack of general knowledge about what was happening in the workplace, a lack of communication and respect from the supervisor or union representative, a negative disposition, and a lack of opportunity for meaningful participation in decision-making.

According to Wanous et al. (2000), Cynicism about organizational change has two possible antecedents: negative affectivity as a personality trait and organizational factors. For example, prior exposure to change may predispose some employees to cynicism, which includes pessimism about the success of change initiatives. The supervisor’s role efficacy includes conveying information, listening effectively, being available, and showing concern. Participation in decision-making is the third organizational factor that has been linked to cynicism about organizational change. Employee cynicism can be influenced by top management. Unless they are used as selection criteria, top management cannot influence personality traits (Wanous et al., 2000).

As previously stated by Hannan and Freeman (1984), Rumelt (1995), and Gilbert (2005), when an organization has structural inertia or a strong strategy, the organization is prone to resist adaptive adjustments to changes in the external environment and is more comfortable with the status quo. This is because an organization’s adaptation to a change will have an effect on the organization’s existing characteristics, such as its routine operating procedures, organizational structure, resource allocation methods, and decision-making procedures (Yi et al., 2016; Hoppmann et al., 2018; Zhen et al., 2021). Inertia in an organization results in a condensing of the organization’s operating mode and direction, reducing its flexibility (Hannan and Freeman, 1984; Godkin and Allcorn, 2008; Allcorn and Godkin, 2011; Sillic, 2019). Organizational inertia has two components: resource rigidity and routine rigidity (Gilbert, 2005). It is the inability of a company to change its resource investment pattern, while routine inflexibility is the lack of change in organizational processes and procedures for using invested resources. (Gilbert, 2005; Moradi et al., 2021).

In organizational literature, the terms organizational inertia and organizational flexibility are mutually exclusive. Flexibility has a number of advantages, and organizations that are more adaptable are more efficient. Inertia manifests itself in a variety of ways in organizations, including the suppression of valuable information within the organization, rigid rules, and an excessive commitment to the organization (Boyer and Robert, 2006; Dew et al., 2006). The organization is an open system that interacts with its surroundings and is self-sufficient. Closed communication and information channels cause an organization to be unaware of changes occurring around it, leading to its demise. Inflexible organizations and individuals are unable to adapt to changing environments. Individual stagnation leads to organizational inertia (Boyer and Robert, 2006; Hirschmann, 2021; Moradi et al., 2021).

By combining social cognitive theory and organizational inertia, this study sought to understand the relationship between cynicism about change and leader empowerment. Humans, according to SCT, are both environmental consumers and producers (Bandura, 2001). Humans’ ability to choose and control their own behavior through deliberate action is called organization (Bandura, 1989, 2001). SCT proposes five mechanisms for learning and shaping behavior. Observation, reflection, self-regulation, and symbolization are the mechanisms. To test the Empowering Leadership development intervention’s effectiveness in reducing cynicism, and thus unsafe behavior, we used SCT and the underlying mechanisms.

Employees’ work is valued, decision-making authority is increased, and unwanted factors such as harassment are eliminated (Zhang and Bartol, 2010). Enabling does not sum up “sharing power.” Empowered employees can self-manage to improve work psychological cognition. Furthermore, subordinate motivation should be considered holistically (Dong et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018b). Basically, empowerment is a matter of degree rather than absolute state, so the issue is managers’ ability to classify both decisions about who to empower and how much (Cheong et al., 2016; Lorinkova and Perry, 2017; Kim et al., 2018b). However, empowerment can also be seen as a mutually beneficial relationship between a leader and his subordinates (Qian et al., 2018; Muafi et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022). Thus, it is critical to always improve team performance by encouraging problem-solving initiative, quick communication, and improved work-life balance. So Amundsen and Martinsen (2014) focus on power sharing, motivation support, and development support.

Power sharing is a basic application of employee empowerment. Its indirect link between self-leadership and freedom within bounds (e.g., encourage independent actions). According to (Cheong et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2018), decision-making procedures distinguish consultation and delegation. Leaders engage subordinates in consultation before delegating authority and decision-making responsibility (Cheong et al., 2016, 2019). Kim et al. (2018a) noted that delegation provides real autonomy in decision making. To feel empowered, everyone must agree on their overall goal and what actions they can take to achieve it. Leaders must motivate subordinates to take initiative, make decisions, and lead themselves (Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014). Encourage subordinates to work toward self-determination and inspire them with goals (Jung et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2022). Employees believe that for them to feel positive and confident in their abilities, it is critical for’superleaders’ to approach subordinates with an open ear and listen to their ideas. As a result, it may foster autonomy and have a significant effect on motivation and efficacy. Additionally, we advise leaders to create a welcoming environment in which subordinates can discover their capabilities, inspire employees, and apply their abilities (Li et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2020). Empowering and inspiring leaders can inspire and create positive emotional states by demonstrating enthusiasm and belief in their future goals and prospects.

The last essential construct for empowering leadership according to Amundsen and Martinsen (2014) is development support, which explains the main characteristic of leaders is to serve as observable models for their subordinates (Cheong et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016). Model learning is a concept in social cognitive theory that implies a behavior can be learned or modified by observing others (learning by example). This is more likely because the models have status, power, success, and/or competence (Hao et al., 2017; Jung et al., 2020). So this study uses two empowering leadership dimensions. It describes how a leader empowers members to take initiative through delegation, coordination, and information sharing. This dimension describes how a leader can model and guide members to keep learning. To motivate and develop subordinates to work autonomously within the organization’s goals and strategies is a genuine concern of leaders (Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014).

Family businesses must be built on a solid foundation of family meetings, respect, and communication. The first step toward family business sustainability is to understand the basics. Competitive advantages are typically fleeting in high-tech environments, whereas advantages may be more sustainable in low-tech environments (Weemaes et al., 2020). Thus, a family firm is defined as one that is “governed and/or managed with the intention of shaping and pursuing the business vision held by a dominant coalition of members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families.” Family-owned enterprise Sustainability is defined as the capacity to recover, rebound, or revert to pre-existing conditions following the occurrence of problems or stresses (Gupta and Bhattacharya, 2016). Lee et al. (2013) were able to quantify an organization’s potential for sustainability (resilience) by examining adaptability measures such as managers’ perceptions of environmental risk, their willingness to seek information about environmental risks, the organization’s structure, their level of involvement in community planning activities, their level of compliance with continuity of operations planning, and whether the department has professional accreditation (Gupta and Bhattacharya, 2016).

According to the Sustainable Family Business (SFB) model, a sustainable family business is an integrated function of the family’s functionality and the business entity’s success (Kuruppuge and Gregar, 2018; Pitchayadol et al., 2018) and that each of these two components has a two-way influence on the other (Heck and Trent, 1999). Aldrich et al. (2021) established that social networks, including families, foster the establishment, growth, and transition of family businesses. Additionally, (Herrero and Hughes, 2019; Vecchio et al., 2019) discovered that the manner in which family members interact has a significant but inconsistent relationship with the family business’s continuity. This mode of interaction encompasses the negotiation process, everyone’s accessibility, each team member’s individuality, and routines.

Cynicism for change refers to the degree to which people are pessimistic about the future of change initiatives, as well as about their own management skills and abilities to bring about change success (Choi, 2011). Wanous et al. (2000) distinguish between two types of cynicism toward change: pessimism about the change itself and dispositional attributes that are associated with those who are responsible for implementing the change. Pessimism, on the other hand, is of particular interest because it is closely associated with generalizable individual attitudes. Comparatively, because they can relate to stakeholders other than management, such as trade union representatives, dispositional attributes lack the ‘focus specificity’ necessary to be practically useful in change management studies, and therefore are not practical in change management studies (Albrecht, 2002). Consequently, the current research will concentrate primarily on the cynical side’s cynicism regarding change.

Interestingly, cynicism about change appears to be a significant in the ability to successfully implement change, making this concept very intriguing. Change is invoked in individuals more frequently (and unsuccessfully) the more likely it is that they will express cynicism about the change (Brown et al., 2017). Employee engagement, on the other hand, in accordance with the aforementioned constructs, plays an important role in preventing cynicism from changing. It is possible to reduce the likelihood of change cynicism by sharing and communicating information while also involving individuals in the decision-making process. Nonetheless, when individuals are cynical about change, resistance to change is more likely to occur, increasing inertia at the individual level as a result (Stanley et al., 2005). Inertia can result from ignoring this individual’s opposition to the desired change, because individual support is required for the significant implementation of the intended change (Fernandez and Rainey, 2017). In order to successfully avoid inertia, it may be necessary to overcome this individual changing attitude.

Based on the findings and discussion above, the following hypotheses can be proposed:

H1: Cynicism about organizational change has a positive and significant effect on organizational inertia.

Even for highly successful businesses, inertia can lead to difficulties in adapting to new business methods. Moradi et al. (2021) demonstrate that the business management model is accompanied by risk and uncertainty, and that the inertia that exists in organizations that have had successful business models in the past leads to business model problems when accepting new business models. Reconfiguring a business model interacts with issues that must be addressed, such as: (1) overcoming inertia, (2) identifying multiple changes, and (3) adopting a new structure and selecting an appropriate approach to improvement. Because of organizational inertia and the resulting uncertainty, firms are unlikely to define their business model unless they are faced with a significant change in their industry or market. Even in cases where adaptation is obvious, the firm’s strategic direction and path dependencies are likely to make the process of adapting existing business models to new market demands or competitive threats more difficult and time-consuming (Vorbach et al., 2017). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

H2: Organizational inertia has a negative and significant effect on sustainable family business.

Cynicism about organizational change has a destructive effect on the organization, and it can even lead to acts of sabotage (DeCelles et al., 2013). Organizational inertia will be created as a result of cynicism about change as a result of a negative attitude (Huang et al., 2013). The development of organizational inertia (resources rigidity, processes rigidity, and path dependency) in a family business will result in the company’s inability to actualize the agility that is required in a rapidly changing business environment if allowed to continue (Huang et al., 2013). According to social cognitive theory, cynicism about organizational change is a personal trait that must be developed (Bandura, 1989). Furthermore, empowering leadership can be defined as a leader’s action in creating a favorable environment for initiated changes to take place (Lorinkova and Perry, 2017). Then, as a form of suppression, empowering leadership will be able to suppress cynicism about change as a result of its empowerment (Frazier et al., 2004; Li and Yuan, 2017). It is expected that the interaction of the two variables will act as a buffer, reducing the negative impact of cynicism on changes in organizational inertia (Huang et al., 2013). Therefore, this study formulated the following hypothesis:

H3: Empowering Leadership will be able to reduce the negative effect of CAOC on organizational inertia in family business in Indonesia.

To address the study’s research question, the first step was to select a research sample representative of an organizational inertia phenomenon, specifically family businesses. Questionnaires were distributed to family business founders and members regarding research variables and changes in family business succession. After effectively tabulating the data, data aggregation, processing, and hypothesis testing are performed; additional discussion, as well as theoretical and practical implications, are produced after the findings are acquired. This is a quantitative study conducted using a cross sectional design, in which all measurements on each person are taken at the same time. The population of this study is Indonesian family-owned businesses. The sampling technique used in this study is non-probability sampling, which means that not all samples have an equal chance of being chosen as a sample. Meanwhile, this study’s sample selection technique is purposive sampling. To qualify as a family business, the owner/manager must have been in the business for at least 1 year or be actively engaged in the business for at least 6 h per week or at least 312 h per year while living with other family members. As a result, this study’s sample is limited to businesses that meet those criteria. The research sample is distributed throughout Indonesia and includes 31 family businesses operating in a variety of sectors or fields, including food and beverage, medicine, electronics, garment manufacturing, and the automotive industry. In total, 124 people were sampled for this study, including 31 leaders from various family businesses located throughout Indonesia and 93 members, three from each organization.

This study’s sample units are divided into two categories: leaders (top to middle management) and members (lower management). This study examines four variables, two of which are distributed to the family business leader and the rest to family business members. This study examines members’ cynicism about organizational change and empowering leadership, while measuring organizational inertia and family business sustainability. This study used a questionnaire to collect primary data, i.e., a prepared list of questions. The cynicism about organizational change variable has 16 operational items adapted from Wanous et al. (2004). The reasons for using dispositional cynicism in this study are (a) distrust of integrity, competence, and leadership motivation (common in family businesses); and (b) the data quality test results for pessimism and situational cynicism show that they do not pass the reliability test. For example, resource dependency, position reinvestment incentives, threat perception, contraction of authority, reduced experimentation, focus on existing resources and learning effects are all operational items of organizational inertia adapted from Gilbert (2005). This variable includes autonomous support (power sharing and motivation support) and development support, which are both adapted from Amundsen and Martinsen (2014).

Each leader is represented by 3 (three) members in each family business, implying that each business family must have a minimum of four members. The sample for this study included 31 family business leaders and 93 family business members or employees. Additionally, data aggregation was used to combine data collected from two distinct subjects in the family business. Aggregation of data is a two-step process. To begin, one or more data groups are identified based on the values in selected features (data grouping); second, the values in one or more selected values are aggregated for each group.

The questionnaire generation process was carried out in two stages, referred to as double-back translation, in which operational items adapted from previous research were translated to Bahasa Indonesia and then back to English to avoid misinterpretation during the translation process. Additionally, the questionnaire was rechecked for informal fallacies such as double-barreled questions, which are questions that address multiple issues but allow for only one response. Meanwhile, the questionnaire used the Likert scale as a measurement tool in this study. The Likert scale is a useful indicator of a study with five (five) scales, as it simplifies the process of calculating results and makes responding easier for respondents (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). After completion, the questionnaire was distributed to family businesses throughout Indonesia, with a leader and members representing each sample unit.

This study’s data are processed using Multiple Moderated Regression (MMR). MMR is a statistical method for assessing the impact of moderation in a research model. The general procedure of this method is to examine the effect of the independent variable (X) on the dependent variable (Z) and the effect of the product (XZ) on the independent variable (Z). The independent variable’s effect on the dependent variable varies at intervals determined by the moderator variable (Hayes, 2018). This study’s goal was to examine how empowered leadership affected cynicism about organizational change, organizational inertia, and family business sustainability. The measurement model for this research was validated and reliability tested in advance. Validity was assessed using EFA, CFA, and PCA (PCA). The reliability test used Cronbach Alpha, Corrected Item Total Correlation, and Split-half testing. In addition, the F-test, coefficient of determination, and t-test results were examined in this study. The F-test was used to assess the significance of the regression model and the effect of all independent variables on the dependent variable. It was determined by the coefficient of determination (or t-test) whether or not each independent variable had a significant effect on the dependent variable.

Validity is determined by the value of the outer loading, which according to Hair et al. (2017) has a cutoff of 0.500, whereas reliability is determined by the reference value of composite reliability and the AVE value, with a recommended CR value in the range of 0.700 and an AVE value greater than 0.500 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the overall value of the outer loading does not fall below the standard of 0.500, and the AVE value is also greater than 0.5. Thus, the data used in this study satisfy the validity assumption. Additionally, the composite reliability value is greater than 0.700, indicating that the data used is reliable. Additionally, as shown in Table 2, pro-change behavior is negatively correlated with pro-change cynicism.

We assessed the study’s construction and analysis level using a group-level analysis approach, with the family business as the unit of analysis. As a result, data collection from each unit to represent their respective groups is necessary. The RWG approach is used to merge individual group data into team-level group data (James et al., 1984; Walumbwa et al., 2017), with a minimum value of 0.700.

The PROCESS macro is used to run SPSS to test the moderated mediation hypothesis (Hayes, 2018). In a more detailed model, we examined the impact of cynicism on changes in Cynicism (Cyndisp) on changes in Sustainability Competitive Advantage (SCA) via Behavioral Inertia (INT) moderated by Empowering Leadership (EL). Using a 5,000-bootstrap sample, we obtained a 95 percent bootstrap confidence interval with an indirect effect bias.

The t-count value of cynicism toward changes to inertia (INT) was −0.964 and the p-value was 0.224. Hypothesis 1 thus fails. The second hypothesis states that inertia reduces SCA. The t-count is 0.449 with a p-value of 0.657, indicating that hypothesis 2 is unsupported. The third hypothesis predicts that EL will reduce cynicism’s impact on family business inertia. The moderating variable (CynDisp*EL) has a t-value of 2.426 and a p-value of 0.17, supporting the hypothesis.

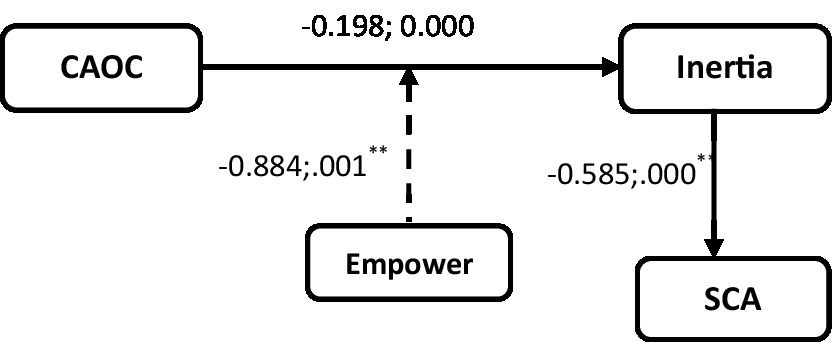

Cynicism has an indirect effect on SCA changes via inertia, according to Hypothesis 4. For H3, Figure 1 and Table 3 show the moderated mediation of Hayes’ 7 model outputs. Model 1’s outcome variable has a 38.50 percent variation (Inertia). The model fits with a F value of 5.630. EL has a significant positive effect on inertia, with a p-value of 0.039 0.05. The LLCI and ULCI are not zero because of the significant interaction (int 1 = Cyndisp*EL). This suggests that EL does act as a moderator in the relationship between cynicism about organizational change and organizational inertia (Hayes, 2013).

The result of the mediation model is as follows: SCA is the criterion and Cyndisp is the independent variable. The proposed model’s R2 is 38.600%, F is 8.807, and p-value (0.001) is significant. Since Inertia directly affects SCA, it appears to be a mediator in the relationship between Cyndisp and SCA. Also, the LLCI and ULCI Boot values are both negative, with no zeros between them. So EL is a moderator at low, average, and high levels.

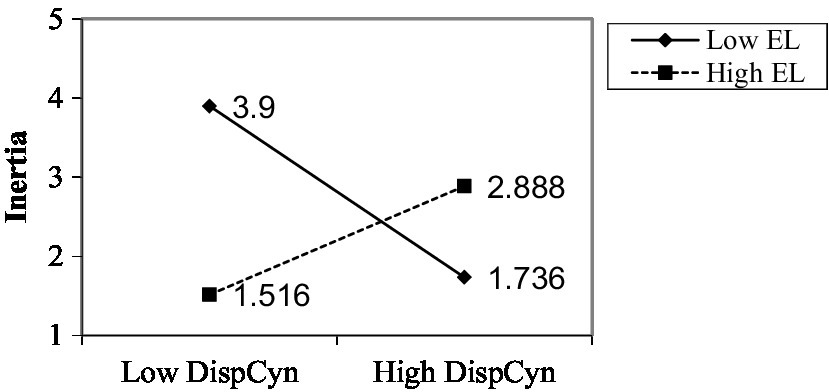

An interaction plot is made to see if the interaction is in the predicted direction. As shown in Figure 2, when leaders are empowered and cynical about change, the inertia value is moderate. Moderate inertia indicates that the family business can maintain a competitive advantage while maintaining the status quo. When cynicism toward change is high and the value of empowered leadership is low, inertia tends to be valuable. Due to the low inertia, the family business is more likely to be dynamic in the long run, thereby establishing a sustainable competitive advantage. Additionally, when cynicism toward change is low and empowerment of leadership is low, it has been demonstrated that the value of inertia is low. Inertia results from low cynicism toward change and high empowerment. Inertia indicates a family business is keeping things the same (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Hayes v3.5 Model-7 output statistical diagram. **Correlation values are significant at p < 0.01.

Figure 3. The effect of cynicism towards change on inertia at various levels of empowering leadership.

Because of the interaction between cynicism about organizational change and empowering leadership, the result demonstrates the ability of the interaction to produce suppression and buffering as a reciprocal triadic mechanism in Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura and Wood, 1989; Frazier et al., 2004; Li and Yuan, 2017; Lorinkova and Perry, 2017). Cynicism about organizational change, as indicated by a reduction in the regression coefficient value of cynicism about organizational change, from −0.884 to −0.198 in the interaction regression coefficient, is said to be able to suppress by the interaction when it can suppress by the interaction (Frazier et al., 2004; Li and Yuan, 2017). Organizational inertia is reduced by the positive influence of empowering leadership, which acts as a buffer against the negative impact of cynicism about organizational change. In other words, when empowering leadership by the leader is perceived as creating a positive environment for employees, the relationship between cynicism about organizational change and organizational inertia is reduced (Lorinkova and Perry, 2017).

The findings have many theoretical implications: To begin, research shows that leaders who empower employees are less effective. The results show that EL is only effective at high concentrations to reduce DispCyn’s negative effect on inertia. Perhaps the most important theoretical contribution of this study is expand the use of Social Cognitive Theory in the context of family business, besides the results of this study indicate that empowering leadership is a form of environmental in triadic reciprocal (Bandura, 1989; Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014; Lim et al., 2020). It has been proven that a positive environment of change can be a suppressor in suppressing cynicism for change, besides that a positive environment can also be a buffer in suppressing the negative influence of cynicism on changes to organizational inertia (Buffer). EL and cynicism change only when subordinates have positive empowering exchange relationships with superiors. Thus, the moderated-mediated model assumes a fully moderated negative relationship between EL and cynicism. These findings add to the growing body of research on the impact of leadership empowerment by highlighting the critical role of empowerment in generating exchange (Lorinkova and Perry, 2017).

The following are the implications: The first use of empowering leadership is to increase employee psychological empowerment and reduce cynicism about change. However, it is important for family business owners to remember that employees must psychologically feel empowered by the owner or leader. The effects of dyadic relationships can be felt by frontline employees, so direct supervisors and their supervisors are encouraged to cultivate high-quality dyadic relationships. This study suggests that family businesses actively train members to manage with the EL style through training and coaching. Development assistance can help reduce cynicism and inertia (Kim et al., 2018a,b).

Second, in the context of family business changes that place employees under pressure, discomfort, and/or uncertainty (Dhaenens et al., 2018; Lorenzo Gomez, 2020), leaders must position themselves as role models for employees, particularly cynical employees. Employees will learn from their leaders how to adapt to change, modify their behavior, and combat cynicism. By reducing employee cynicism through empowering leadership behaviors demonstrated by a leader who also enjoys a positive relationship with top management, managers can ensure a happier workplace and possibly even a more seamless transition to a new organizational reality without experiencing inertia (Santiago, 2015; Hirschmann, 2021).

This study has various limitations, including the following: (1) the use of cross-sectional data, (2) the lack of a research gap between variables, (3) data processing at the same place, and (4) the inability to conduct simultaneous testing due to the dimensions of the test equipment utilized. Because of this, it is recommended that longitudinal data be used in the next study. This is done in order to ensure that there is a gap between CAOC and SCA in terms of influencing inertia. Researchers can use a time lag of 3–6 months with the same respondents in order to get more accurate results. Furthermore, researchers can use covariance-based SEM to determine whether or not a test is unidimensional.

The findings of this study indicate that cynicism toward organizational change has a beneficial and statistically significant effect on organizational inertia. Additionally, empowering leadership has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between cynicism about organizational change and organizational inertia. Overall, this study sheds new light on the importance of empowering leadership in family businesses in suppressing members’ cynicism toward change, thereby reducing the likelihood of organizational inertia. A leader’s action in creating a favorable environment for initiated changes can also be defined as “a leader’s action in facilitating the implementation of changes” (Lorinkova and Perry, 2017). When empowered leadership suppresses cynicism about change, it is doing so in the form of suppression (Frazier et al., 2004; Li and Yuan, 2017). It is anticipated that the interaction of the two variables will act as a buffer, mitigating the negative impact of cynicism on changes in organizational inertia by at least a factor of two (Huang et al., 2013). The results of the moderated mediation test revealed that EL was responsible for determining the indirect effect of CAOC on SCA through organizational inertia in the study. EL not only reduces CAOC (Suppress), but it also supports the relationship between CAOC and inertia (Buffer), and it determines the indirect effect of CAOC on SCA through inertia (Frazier et al., 2004; Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014; Hayes, 2018).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

TT and VS presented the idea about how cynicism might affect the sustainability of an organization. SS and EA focused on how to conduct the data analysis with the multi-source and data aggregation, while TS and EA helped to gain access to family business networks in Indonesia. TT supervised the progress of this paper and added some references about organizational change and cynicism. VS helped to add some contribution and discussion to this paper. Finally, TT and EA edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abugre, J. B. (2017). Relations at workplace, cynicism and intention to leave. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 25, 198–216. doi: 10.1108/ijoa-09-2016-1068

Ahearne, M., Jelinek, R., and Rapp, A. (2005). Moving beyond the direct effect of SFA adoption on salesperson performance: training and support as key moderating factors. Ind. Mark. Manag. 34, 379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.09.020

Albrecht, S. L. (2002). Perceptions of integrity, competence and trust in senior management as determinants of cynicism toward change. Public Adm. Manag. Interact. J. 7, 320–343.

Aldrich, D. P., Kolade, O., McMahon, K., and Smith, R. (2021). Social capital’s role in humanitarian crises. J. Refug. Stud. 34, 1787–1809.

AlKayid, K., Selem, K. M., Shehata, A. E., and Tan, C. C. (2022). Leader vision, organizational inertia and service hotel employee creativity: role of knowledge-donating. Curr. Psychol. 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02743-6

Allcorn, S., and Godkin, L. (2011). Workplace psychodynamics and the management of organizational inertia. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 21, 89–104. doi: 10.1108/10595421111106247

Amundsen, S., and Martinsen, Ø. L. (2014). Empowering leadership: construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. Leadersh. Q. 25, 487–511. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.009

Aslam, U., Ilyas, M., Imran, M. K., and Rahman, U.-U. (2016). Detrimental effects of cynicism on organizational change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 29, 580–598. doi: 10.1108/jocm-12-2014-0231

Bakari, H., Hunjra, A. I., Jaros, S., and Khoso, I. (2019). Moderating role of cynicism about organizational change between authentic leadership and commitment to change in Pakistani public sector hospitals. Leadersh. Health Serv. 32, 387–404. doi: 10.1108/LHS-01-2018-0006

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 44, 1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura, A., and Wood, R. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14, 361–384.

Bang, H., and Reio, T. G. Jr. (2017). Examining the role of cynicism in the relationships between burnout and employee behavior. Rev. Psicol. Trabajo Organ. 33, 217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.rpto.2017.07.002

Bouckenooghe, D., Schwarz, G. M., Kanar, A., and Sanders, K. (2021). Revisiting research on attitudes toward organizational change: bibliometric analysis and content facet analysis. J. Bus. Res. 135, 137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.028

Bouckenooghe, D., Schwarz, G. M., and Minbashian, A. (2014). Herscovitch and Meyer’s three-component model of commitment to change: meta-analytic findings. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24, 578–595. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2014.963059

Boyer, M., and Robert, J. (2006). Organizational inertia and dynamic incentives. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 59, 324–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2004.06.024

Brown, M., and Cregan, C. (2008). Organizational change cynicism: the role of employee involvement. Hum. Resour. Manag. 47, 667–686. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20239

Brown, M., Kulik, C. T., Cregan, C., and Metz, I. (2017). Understanding the change– cynicism cycle: the role of HR. Hum. Resour. Manag. 56, 5–24. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21708

Cheong, M., Spain, S. M., Yammarino, F. J., and Yun, S. (2016). Two faces of empowering leadership: enabling and burdening. Leadersh. Q. 27, 602–616. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.01.006

Cheong, M., Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Spain, S. M., and Tsai, C.-Y. (2019). A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. Leadersh. Q. 30, 34–58. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.08.005

Chirico, F., and Nordqvist, M. (2010). Dynamic capabilities and trans-generational value creation in family firms: the role of organizational culture. Int. Small Bus. J. 28, 487–504. doi: 10.1177/0266242610370402

Chirico, F., and Salvato, C. (2016). Knowledge internalization and product development in family firms: when relational and affective factors matter. Entrep. Theory Pract. 40, 201–229. doi: 10.1111/etap.12114

Choi, M. (2011). Employees’ attitudes toward organizational change: a literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 50, 479–500. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20434

Cinite, I., and Duxbury, L. E. (2018). Measuring the behavioral properties of commitment and resistance to organizational change. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 54, 113–139. doi: 10.1177/0021886318757997

Dean, J. W. J., Brandes, P., and Dharwadkar, R. (1998). Organizational cynicism. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 341–352. doi: 10.2307/259378

DeCelles, K. A., Tesluk, P. E., and Taxman, F. S. (2013). A field investigation of multilevel cynicism toward change. Organ. Sci. 24, 154–171. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1110.0735

Dew, N., Goldfarb, B., and Sarasvathy, S. (2006). Optimal inertia: when organizations should fail. Ecol. Strategy 23, 73–99. doi: 10.1016/s0742-3322(06)23003-1

Dhaenens, A. J., Marler, L. E., Vardaman, J. M., and Chrisman, J. J. (2018). Mentoring in family businesses: Toward an understanding of commitment outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 28, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.05.005

Dong, Y., Chuang, A., Liao, H., and Zhou, J. (2015). Fostering employee service creativity: joint effects of customer empowering behaviors and supervisory empowering leadership. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 100, 1364–1380. doi: 10.1037/a0038969

Eslami, M. H., and Melander, L. (2019). Exploring uncertainties in collaborative product development: managing customer-supplier collaborations. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 53, 49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jengtecman.2019.05.003

Fernandez, S., and Rainey, H. G. (2017). Managing successful organizational change in the public sector. Public Adm. Rev. 66, 168–176. doi: 10.4324/9781315095097-2

Fernhaber, S. A., and Li, D. (2013). International exposure through network relationships: implications for new venture internationalization. J. Bus. Ventur. 28, 316–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.002

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., and Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. J. Couns. Psychol. 51, 115–134. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115

Gilbert, C. G. (2005). Unbundling the structure of inertia: resource versus routine rigidity. Acad. Manag. J. 48, 741–763. doi: 10.5465/amj.2005.18803920

Godkin, L., and Allcorn, S. (2008). Overcoming organizational inertia: a tripartite model for achieving strategic organizational change. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 8, 82–94.

Grama, B., and Todericiu, R. (2016). Change, resistance to change and organizational cynicism. Stud. Bus. Econ. 11, 47–54. doi: 10.1515/sbe-2016-0034

Gupta, P. D., and Bhattacharya, S. (2016). Impact of knowledge management processes for sustainability of small family businesses: evidences from the brassware sector of Moradabad (India). J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 15, 1–46. doi: 10.1142/s0219649216500404

Hair, J. J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2017). Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th Edn. London: Pearson Education Limited.

Hannan, M. T., and Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 49, 149–164. doi: 10.2307/2095567

Hao, P., He, W., and Long, L.-R. (2017). Why and when empowering leadership has different effects on employee work performance: the pivotal roles of passion for work and role breadth Self-efficacy. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 25, 85–100. doi: 10.1177/1548051817707517

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Methodology in the Social Sciences: Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis – A Regression Based Approach. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Heck, R. K. Z., and Trent, E. S. (1999). The prevalence of family business from a household sample. Fam. Bus. Rev. 12, 209–219.

Herrero, I., and Hughes, M. (2019). When family social capital is too much of a good thing. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 10:100271. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2019.01.001

Hirschmann, G. (2021). International organizations' responses to member state contestation: from inertia to resilience. Int. Aff. 97, 1963–1981. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiab169

Hoppmann, J., Naegele, F., and Girod, B. (2019). Boards as a source of inertia. Examining the internal. Acad. Manag. J. 62, 437–468. doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.1091

Huang, H.-C., Lai, M.-C., Lin, L.-H., and Chen, C.-T. (2013). Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 26, 977–1002. doi: 10.1108/jocm-04-2012-0047

Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., and Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: from input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 517–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070250

Islam, M. N., Furuoka, F., and Idris, A. (2020). Employee championing behavior in the context of organizational change: a proposed framework for the business organizations in Bangladesh. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 14, 735–757. doi: 10.1108/jabs-01-2019-0019

James, M. S. L. (2005). Antecedents and Consequences of Cynicism in Organizations: An Examination of the Potential Positive and Negative Effects on School Systems. Tallahassee, FL: The Florida State University College of Business.

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., and Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 69, 85–98. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85

Jung, K. B., Kang, S.-W., and Choi, S. B. (2020). Empowering leadership, risk-taking behavior, and employees’ commitment to organizational change: the mediated moderating role of task complexity. Sustainability 12:2340. doi: 10.3390/su12062340

Kim, M., Beehr, T. A., and Prewett, M. S. (2018b). Employee responses to empowering leadership: a meta-analysis. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 25, 257–276. doi: 10.1177/1548051817750538

Kim, D., Moon, C. W., and Shin, J. (2018a). Linkages between empowering leadership and subjective well-being and work performance via perceived organizational and co-worker support. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 39, 844–858. doi: 10.1108/lodj-06-2017-0173

Kundu, S. C., Kumar, S., and Gahlawat, N. (2019). Empowering leadership and job performance: mediating role of psychological empowerment. Manag. Res. Rev. 42, 605–624. doi: 10.1108/mrr-04-2018-0183

Kuruppuge, R. H., and Gregar, A. (2018). Employees’ organizational preferences: a study on family businesses. Econ. Soc. 11, 255–266. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2018/11-1/17

Lee, A. V., Vargo, J., and Seville, E. (2013). Developing a tool to measure and compare organizations’ resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 14, 29–41. doi: 10.1061/(asce)nh.1527-6996.0000075

Lee, A., Willis, S., and Wei tian, A. (2018). When Empowering Employees Works, and When It Doesn’t.pdf. Harvard Business Review.

Li, M., Liu, W., Han, Y., and Zhang, P. (2016). Linking empowering leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 29, 732–750. doi: 10.1108/jocm-02-2015-0032

Li, J., and Yuan, B. (2017). Both angel and devil: the suppressing effect of transformational leadership on proactive employee’s career satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 65, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.008

Lim, J. S., Choe, M.-J., Zhang, J., and Noh, G.-Y. (2020). The role of wishful identification, emotional engagement, and parasocial relationships in repeated viewing of live-streaming games: a social cognitive theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 108:106327. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106327

Lin, M., and Ling, Q. (2021). The role of top-level supportive leadership: a multilevel, trickle-down, moderating effects test in Chinese hospitality and tourism firms. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 46, 104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.11.013

Lin, M., Zhang, X., Ng, B. C. S., and Zhong, L. (2022). The dual influences of team cooperative and competitive orientations on the relationship between empowering leadership and team innovative behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 102:103160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103160

Lorenzo Gomez, J. D. (2020). Barriers to change in family businesses. Eur J. Fam. Bus. 10, 56–65. doi: 10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i1.7018

Lorinkova, N. M., and Perry, S. J. (2017). When is empowerment effective? The role of leader-leader exchange in empowering leadership, cynicism, and time theft. J. Manag. 43, 1631–1654. doi: 10.1177/0149206314560411

Mallette, P., and Hopkins, W. E. (2013). Structural and cognitive antecedents to middle management influence on strategic inertia. J. Glob. Bus. Manag. 9, 104–115.

Meng-Hsien, L., Samantha, N. N. C., and Terry, L. C. (2018). Understanding olfaction and emotions and the moderating role of individual differences. Eur. J. Mark. 52, 811–836. doi: 10.1108/EJM-05-2015-0284

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., and Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. J. Manag. Stud. 40, 1453–1476. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00387

Moradi, E., Jafari, S. M., Doorbash, Z. M., and Mirzaei, A. (2021). Impact of organizational inertia on business model innovation, open innovation and corporate performance. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 26, 171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.01.003

Muafi, U., Fachrunnisa, O., Siswanti, Y., El Qadri, Z. M., and Harjito, D. A. (2019). Empowering leadership and individual readiness to change: the role of people dimension and work method. J. Knowl. Econ. 10, 1515–1535. doi: 10.1007/s13132-019-00618-z

Neves, P. (2012). Organizational cynicism: spillover effects on supervisor–subordinate relationships and performance. Leadersh. Q. 23, 965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.06.006

Newman, A., Tse, H. H. M., Schwarz, G., and Nielsen, I. (2018). The effects of employees’ creative self-efficacy on innovative behavior: the role of entrepreneurial leadership. J. Bus. Res. 89, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.001

Nguyen, T. M., Malik, A., and Budhwar, P. (2022). Knowledge hiding in organizational crisis: the moderating role of leadership. J. Bus. Res. 139, 161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.026

Oreg, S. (2006). Personality, context, and resistance to organizational change. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 15, 73–101. doi: 10.1080/13594320500451247

Oyadomari, J. C. T., Afonso, P. S. L. P., Dultra-de-Lima, R. G., Mendonça Neto, O. R. R., and Righetti, M. C. G. (2018). Flexible budgeting influence on organizational inertia and flexibility. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 67, 1640–1656. doi: 10.1108/ijppm-06-2017-0153

Pitchayadol, P., Hoonsopon, D., Chandrachai, A., and Triukose, S. (2018). Innovativeness in Thai family SMEs: an exploratory case study. J. Small Bus. Strateg. 28, 38–48.

Qian, Y., and Daniels, T. D. (2008). A communication model of employee cynicism toward organizational change. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 13, 319–332. doi: 10.1108/13563280810893689

Qian, J., Song, B., Jin, Z., Wang, B., and Chen, H. (2018). Linking empowering leadership to task performance, taking charge, and voice: the mediating role of feedback-seeking. Front. Psychol. 9:2025. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02025

Quratulain, S., and Al-Hawari, M. A. (2021). Interactive effects of supervisor support, diversity climate, and employee cynicism on work adjustment and performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 93:102803. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102803

Rayan, A. R. M., Aly, N. A. M., and Abdelgalel, A. M. (2018). Organizational cynicism and counterproductive work behaviors: an empirical study. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 10, 70–79.

Reichers, A. E., Wanous, J., and Austin, J. (1997). Understanding and managing cynicism about organizational change. Acad. Manag. Exec. 11, 48–59. doi: 10.5465/ame.1997.9707100659

Rumelt, R. P. (1995). “Inertia and transformation,” in Resource-Based and Evolutionary Theories of the Firm: Towards a Synthesis. ed. C. A. Montgomery (Kluwer Academic Publishers).

Santiago, A. (2015). Inertia as inhibiting competitiveness in Philippine family businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 5, 257–276. doi: 10.1108/jfbm-07-2014-0015

Schmitz, M. A., Froese, F. J., and Bader, A. K. (2018). Organizational cynicism in multinational corporations in China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 24, 620–637. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2018.1492203

Schraeder, M., Jordan, M. H., Self, D. R., and Hoover, D. J. (2016). Unlearning cynicism. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 24, 532–547. doi: 10.1108/ijoa-05-2013-0674

Scott, K. A., and Zweig, D. (2016). Understanding and mitigating cynicism in the workplace. J. Manag. Psychol. 31, 552–569. doi: 10.1108/jmp-01-2015-0023

Scott, K. A., and Zweig, D. (2020). The cynical subordinate: exploring organizational cynicism, LMX, and loyalty. Pers. Rev. 49, 1731–1748. doi: 10.1108/pr-04-2019-0165

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., and Gersick, K. E. (2012). 25 years of family business review. Fam. Bus. Rev. 25, 5–15. doi: 10.1177/0894486512437626

Sillic, M. (2019). Critical impact of organizational and individual inertia in explaining non-compliant security behavior in the shadow IT context. Comput. Secur. 80, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2018.09.012

Stanley, D. J., Meyer, J. P., and Topolnytsky, L. (2005). Employee cynicism and resistance to organizational change. J. Bus. Psychol. 19, 429–459. doi: 10.1007/s10869-005-4518-2

Turi, J. A., Sorooshian, S., and Javed, Y. (2019). Impact of the cognitive learning factors on sustainable organizational development. Heliyon 5:e02398. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02398

Van Bockhaven, W., Matthyssens, P., and Vandenbempt, K. (2015). Empowering the underdog: soft power in the development of collective institutional entrepreneurship in business markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 48, 174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.03.020

van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., and van Merriënboer, J. (2010). Effective peer assessment processes: research findings and future directions. Learn. Instr. 20, 270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.004

Vecchio, P. D., Secundo, G., Rubino, M., Garzoni, A., and Vrontis, D. (2019). Open innovation in family firms: empirical evidence about internal and external knowledge flows. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 26, 979–997. doi: 10.1108/BPMJ-03-2019-0142

Vorbach, S., Wipfler, H., and Schimpf, S. (2017). Business model innovation vs. business model inertia: the role of disruptive technologies. Berg. Huttenmannische Monatshefte 162, 382–385. doi: 10.1007/s00501-017-0671-y

Walter, F., and Cole, M. S. (2011). Change cynicism, transformational leadership, and the buffering role of dispositional optimism. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2011, 1–6. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2011.1.1da

Walumbwa, F. O., Muchiri, M. K., Misati, E., Wu, C., and Meiliani, M. (2017). Inspired to perform: a multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of thriving at work. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 249–261. doi: 10.1002/job.2216

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., and Austin, J. T. (2000). Cynicism about organizational change. Group Org. Manag. 25, 132–153. doi: 10.1177/1059601100252003

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., and Austin, J. T. (2004). Cynicism about organizational change: an attribution process perspective. Psychol. Rep. 94, 1421–1434. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3c.1421-1434

Weemaes, S., Bruneel, J., Gaeremynck, A., and Debrulle, J. (2020). Initial external knowledge sources and start-up growth. Small Bus. Econ. 58, 523–540. doi: 10.1007/s11187-020-00428-7

Yi, S., Knudsen, T., and Becker, M. C. (2016). Inertia in routines: a hidden source of organizational variation. Organ. Sci. 27, 782–800. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2016.1059

Yim, J. S.-C., Moses, P., and Choy, S. C. (2017). “Cynicism toward educational change on teacher satisfaction: the contribution of situational and dispositional attribution,” in Empowering 21st Century Learners Through Holistic and Enterprising Learning. eds. G. Teh and S. Choy (Singapore: Springer), 147–156.

Zeidan, S., and Prentice, C. (2022). The journey from optimism to cynicism: the mediating and moderating roles of coping and training. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 71:102796. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102796

Zhang, X., and Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity; the influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 107–128. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.48037118

Keywords: cynicism about organizational change, organizational inertia, empowering leadership, attribution theory, family business

Citation: Teofilus T, Ardyan E, Sutrisno TFCW, Sabar S and Sutanto V (2022) Managing Organizational Inertia: Indonesian Family Business Perspective. Front. Psychol. 13:839266. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.839266

Received: 19 December 2021; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 19 May 2022.

Edited by:

Daniel Roque Gomes, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

Pouya Zargar, Girne American University, CyprusCopyright © 2022 Teofilus, Ardyan, Sutrisno, Sabar and Sutanto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sabar Sabar, c2FiYXJAcHJvZGVzLml0cy5hYy5pZA==; Elia Ardyan, ZWxpYS5hcmR5YW5AY2lwdXRyYS5hYy5pZA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.