94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Psychol., 24 February 2022

Sec. Health Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.827320

This article is part of the Research TopicMental Health Literacy: How to Obtain and Maintain Positive Mental HealthView all 19 articles

Carlos Laranjeira1,2,3*

Carlos Laranjeira1,2,3* Ana Querido1,2,4

Ana Querido1,2,4As the world confronts the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences, including an associated mental health crisis, finding meaning and building positive processes and capacities will help strengthen future mental health (Waters et al., 2021). Existential perspectives use this basic insight to advocate that suffering is an inherent part of life that must be confronted, rather than avoided or amended (Israelashvili, 2021). Positive psychology studies adaptation to adversity and aims to identify factors that favour good psychological adjustment, as well as physical and mental health (Reppold et al., 2015; Phan et al., 2020). Notwithstanding, the mental-ill health approach is still predominant, with authors suggesting the need to improve “mental health literacy” and promote access to mental health services (Mansfield et al., 2020).

Recently, there has been increased interest in assessing the attributes, structure and individual variability of wellbeing and identifying its psychological promotors. This research has begun to clarify the determinants of positive mental health (Gallagher and Lopez, 2009; Das et al., 2020). Positive mental health encompasses the personal resources to face life's challenges, foster satisfactory relationships with others, and achieve psychological wellbeing, including feelings of satisfaction with life, vitality and energy, and physical wellbeing (Teixeira et al., 2019). Applied to Meleis (2010) theory, positive mental health can facilitate a healthy changeover within a transitional process, since personal, community, and social conditions can foster or restrict healthy transitions and the outcome of transitions.

There is a need for mental health literacy programs that are focused on hope, and provide accurate information about disorders and recovery. Positive expectations for the future, commonly conceptualised as hope and optimism in the literature, can act as potential mechanisms toward achieving positive mental health (Gallagher and Lopez, 2009, 2018). The conceptualizations of dispositional hope (Snyder, 2002) and dispositional optimism (Scheier and Carver, 1985; Carver and Scheier, 2014) share several elements: (a) personality traits, (b) cognitive constructs, (c) reference to general expectancies, (d) relation to significant personal goals, (e) future orientation, and (f) acting as determinants of behaviour (Krafft et al., 2021). Hope and optimism, although often used interchangeably in clinical discourse, are in fact distinct constructs, corresponding to distinct mechanisms by which expectations shape human behaviour and produce positive outcomes (Gallagher and Lopez, 2009; Schiavon et al., 2017).

This opinion paper aims to examine some differences between optimism and hope, and integrate these constructs in the context of positive mental health. We also intend to point out some interventions that promote hope and optimism, where mental and psychiatric health nursing play an important role.

Whether optimism and hope can affect physical and mental health has been discussed among academics around the world (Milona, 2020). There is empirical evidence supporting the notion that both attitudes contribute to positive outcomes (Schiavon et al., 2017; Pleeging et al., 2021). In this context, optimism is defined as a cognitive variable reflecting one's favourable view about their future (Carver and Scheier, 2019). Optimists generally have more positive than negative expectations and tend to report less distress in their daily lives, even in the face of challenges (Carver et al., 2010). What is expected to happen in the future can affect how people experience situations in their daily lives, their health, and how they deal with emotions and stress.

Optimists are more focused on generalised expectations rather than how or why the goal is achieved (Carver and Scheier, 2002). Studies has found that optimism is related to fewer symptoms of depression, higher levels of wellbeing, lower attrition rates, and stronger perceptions of social support (Forgeard and Seligman, 2012; Schug et al., 2021). The positive repercussions of optimism may be related to the greater probability of adopting health-promoting behaviours and coping strategies that enable better psychic adjustment (Carver and Scheier, 2014, 2019). Recent evidence reveals that optimism is modifiable and associated with better cardiovascular health (Boehm et al., 2020) and increased likelihood of healthy aging (James et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019). In contrast, pessimists have a less favourable perception of the world and are more likely to adopt risky behaviours, such as the use and abuse of alcohol and other drugs (Carver and Scheier, 2019), and display more harmful reactions and adaptations to adversities, compared to optimists (Forgeard and Seligman, 2012; Carver and Scheier, 2019).

Snyder (1991, as cited in Schiavon et al., 2017, p. 2) defined “hope as a state of positive motivation based on three components: objectives (goals to be achieved), pathways (planning to achieve these goals), and agency (motivation directed toward these objectives).” Hope theory emphasises the presence of personal agency related to goals and the recognition of strategies to achieve those goals (Snyder, 2002). Therefore, this theory suggests that a hopeful person would endorse statements such as “I will achieve my goal,” but also “I have a plan […] to achieve this goal” and “I am motivated and confident in my ability to use this plan to achieve this goal” (Gallagher and Lopez, 2009, p. 548). According to recent research, an individual's level of hope is often determined by innate personality characteristics and influenced by psychosocial conditions (success in attaining goals and facing stressors, social support, goal-concordant care), physiological factors (including stress hormones, immune mediators, and neurotransmitters) and environmental factors (Corn et al., 2020).

Snyder (2002) hope theory is not the only perspective that distinguishes hope from optimism: Herth's model of hope assumes that hope is a cognitive and motivational attribute needed to initiate and support action towards goal achievement (Arnau et al., 2010).

Currently, mental health literacy programs aim to understand how to reach and maintain positive mental health, recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about treatments, reduce stigma towards mental disorders, and enhance the help-seeking ability, namely when and where to seek help, but also how to best manage and improve one's own mental health (Kutcher et al., 2016). As a catalyst for positive change, hope promotes overall mental health and may help heal specific conditions, including severe mental illness, suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety and trauma-related disorders (Huen et al., 2015; Gallagher et al., 2020; Tomasulo, 2020; Sari et al., 2021). Research also demonstrates that hope promotes wellbeing more than optimism or self-efficacy (individual's belief in their own ability perform task and attain goal) (Krafft et al., 2021). In addition, research shows that hope has strong associations with several psychosocial process and outcomes, including positive affect, emotional adjustment and illness-related coping, greater life satisfaction, enhanced perceptions that life is meaningful, a higher sense of purpose in life, quality of life, and social support (Corn et al., 2020; Long et al., 2020).

A large longitudinal study among older adults exploring the potential public health implications of hope for subsequent health and wellbeing outcomes revealed that “a greater sense of hope was associated with: better physical health and health behavior outcomes (e.g., reduced risk of all-cause mortality, fewer chronic conditions, and fewer sleep problems), higher psychological wellbeing (e.g., increased positive affect, life satisfaction, and purpose in life), lower psychological distress, and better social wellbeing” (Long et al., 2020, p. 1).

Long-term, mental health promotion in vulnerable populations is deeply intertwined with hope-based interventions. At a time when predictions regarding mental health are particularly grim, those involved in promoting mental health, need to pay close attention to the relation between evidence, hope and intervention.

Psychiatric-mental health nursing is grounded in interpersonal engagement and includes a broad range of helping activities, from teaching to counselling (Hartley et al., 2020). Within this interpersonal context, it is well known that expectations about the future directly influence the subject's wellbeing. Given the protective effect of optimism and hope in people's lives, especially with regard to better physical and mental health, two questions must be considered: is it possible to develop or enhance levels of optimism and hope? How they can be mobilized as an intra/interpersonal healing resource?

The techniques grounded in cognitive-behavioural therapy can be an effective strategy to develop more positive beliefs about the future. Using this approach, nurses can help their patients understand the schemes that coordinate their thoughts, behaviours and feelings (Carver and Scheier, 2014). Optimism can be activated by training and cognitive restructuring regarding the subject's way of thinking and acting (Carver et al., 2010; Carver and Scheier, 2014).

The evidence suggests the possibility of applying optimism and hope through different strategies and intervention programs (Malouff and Schutte, 2016), especially psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring strategies aimed at extracting positive aspects of everyday situations. Testing such interventions is a first step toward producing and spreading effective programs that underscore the positive effects of optimism (Carver and Scheier, 2014).

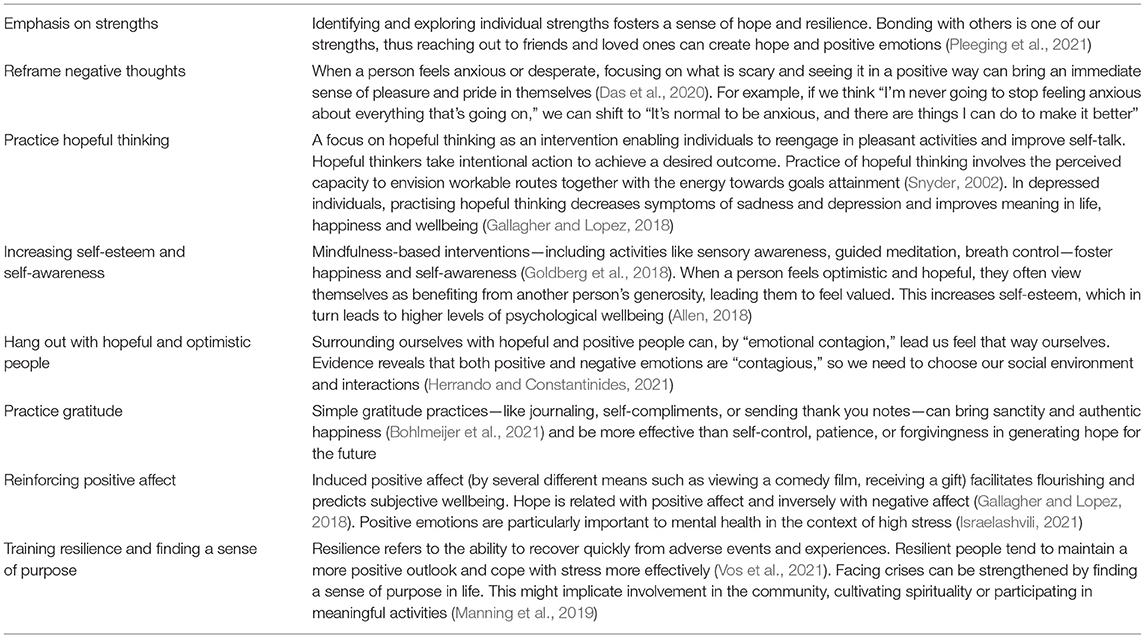

Mental health, hope and optimism are intimately related, and can be reinforced with simple daily actions that boost mental strength, even in the midst of uncertainty such as currently faced with the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we recommend some evidence-based practices to promote hope/optimism and support better mental health literacy (Table 1).

Table 1. Strategies to cultivate a hope/optimism mind-set (based on Newport Academy, 2020).

In sum, optimism and hope are important adaptive phenomena that foster wellbeing, quality of life, and psychological adjustment in the general population and in specific groups, such as people living with mental health conditions. Optimistic and hopeful individuals adapt better to adversity, have lower chances of developing mental disorders, and exhibit behaviours that are healthier and related to greater satisfaction with life. Given these benefits, understanding how hope and optimism arise and flourish is of great interest, and will help develop promotors of mental health. More evidence is needed to develop hope-based interventions and establish their true efficacy. Ideally, these studies would involve randomized control trials (RCTs) with appropriate sample sizes that compare optimism and hope-based interventions to already validated gold standard treatments.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work is funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (UIDB/05704/2020 and UIDP/05704/2020) and under the Scientific Employment Stimulus—Institutional Call (CEECINST/00051/2018).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared affiliation with one of the authors AQ at time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allen, S. (2018). The Science of Gratitude. A white paper prepared for the John Templeton Foundation by the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley. Available online at: https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/GGSC-JTF_White_Paper-Gratitude-FINAL.pdf (accessed November 30, 2021).

Arnau, R. C., Martinez, P., Guzman, I. N., Herth, K., and Konishi, C. Y. (2010). A Spanish-language version of the Hearth Hope Scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 70, 808–824. doi.10.1177/0013164409355701

Boehm, J. K., Qureshi, F., Chen, Y., Soo, J., Umukoro, P., Hernandez, R., et al. (2020). Optimism and cardiovascular health: longitudinal findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Psychosom. Med. 82, 774–781. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000855

Bohlmeijer, E. T., Kraiss, J. T., Watkins, P., and Schotanus-Dijkstra, M. (2021). Promoting gratitude as a resource for sustainable mental health: results of a 3-armed randomized controlled trial up to 6 months follow-up. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 1011–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00261-5

Carver, C. S., and Scheier, M. F. (2002). Optimism, in Handbook of Positive Psychology, eds Snyder, C. R., and Lopez, S. J., (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 231–243.

Carver, C. S., and Scheier, M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003

Carver, C. S., and Scheier, M. F. (2019). Optimism, in Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures, eds Gallagher, M. W., and Lopez, S. J., (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 61–76.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., and Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clin. Psychol. Rev., 30, 879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006

Corn, B. W., Feldman, D. B., and Wexler, I. (2020). The science of hope. Lancet Oncol. 21, e452–e459.

Das, K. V., Jones-Harrell, C., Fan, Y., Ramaswami, A., Orlove, B., and Botchwey, N. (2020). Understanding subjective well-being: perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev. 41, 25. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00142-5

Forgeard, M. J., and Seligman, M. E. (2012). Seeing the glass half full: a review of the causes and consequences of optimism. Pratiq. Psychol. 18, 107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.prps.2012.02.002

Gallagher, M. W., Long, L. J., Richardson, A., D'Souza, J., Boswell, J. F., Farchione, T. J., et al. (2020). Examining hope as a transdiagnostic mechanism of change across anxiety disorders and CBT treatment protocols. Behav. Ther. 51, 190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.06.001

Gallagher, M. W., and Lopez, S. J. (2009). Positive expectancies and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. J Posit Psychol. 4, 548–556. doi: 10.1080/17439760903157166

Gallagher, M. W., and Lopez, S. J. (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Hope. New York: Oxford University Press.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., et al. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 59, 52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

Hartley, S., Raphael, J., Lovell, K., and Berry, K. (2020). Effective nurse-patient relationships in mental health care: a systematic review of interventions to improve the therapeutic alliance. Int J Nurs. Stud. 102, 103490. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103490

Herrando, C., and Constantinides, E. (2021). Emotional contagion: a brief overview and future directions. Front. Psychol. 12, 712606. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712606

Huen, J. M., Ip, B. Y., Ho, S. M., and Yip, P. S. (2015). Hope and hopelessness: the role of hope in buffering the impact of hopelessness on suicidal ideation. PLoS ONE 10, e0130073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130073

Israelashvili, J. (2021). More positive emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with better resilience, especially for those experiencing more negative emotions. Front. Psychol. 12, 648112. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648112

James, P., Kim, E. S., Kubzansky, L. D., Zevon, E. S., Trudel-Fitzgerald, C., and Grodstein, F. (2019). Optimism and healthy aging in women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 56, 116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.037

Krafft, A. M., Guse, T., and Maree, D. (2021). Distinguishing perceived hope and dispositional optimism: theoretical foundations and empirical findings beyond future expectancies and cognition. J. Well-being Assess. (2021) 2021:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s41543-020-00030-4

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., and Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental health literacy: past, present and future. Can. J. Psychiatr. 61, 154–8. doi: 10.1177/0706743715616609

Lee, L. O., James, P., Zevon, E. S., Kim, E. S., Trudel-Fitzgerald, C., Spiro, A. 3rd, et al. (2019). Optimism is associated with exceptional longevity in 2 epidemiologic cohorts of men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 116, 18357–18362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900712116

Long, K. N., Kim, E. S., Chen, Y., Wilson, M. F., Worthington, E. Jr, and VanderWeele, T. J. (2020). The role of hope in subsequent health and well-being for older adults: an outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Global Epidemiol. 2, 100018. doi.org/10.1016/j.gloepi.2020.100018

Malouff, J. M., and Schutte, N. S. (2016). Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1221122

Manning, L., Ferris, M., Rosario, C. N., Prues, M., and Bouchard, L. (2019). Spiritual resilience: understanding the protection and promotion of well-being in the later life. J. Relig. Spirit. Aging 31, 168–186. doi: 10.1080/15528030.2018.1532859

Mansfield, R., Patalay, P., and Humphrey, N. (2020). A systematic literature review of existing conceptualisation and measurement of mental health literacy in adolescent research: current challenges and inconsistencies. BMC Public Health 20, 607. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08734-1

Meleis, A. (2010). Transitions Theory: Middle Range and Situation Specific Theories in Nursing Research and Practice. New York: Springer Publishing Company

Milona, M. (2020). Hope and Optimism. John Templeton Foundation. Available online at: https://www.templeton.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/JTF-Hope-Optimism.pdf

Newport Academy (2020). The Connection Between Hope and Mental Health. Available online at: https://www.newportacademy.com/resources/mental-health/hope-and-mental-health/

Phan, H. P., Ngu, B. H., Chen, S. C., Wu, L., Shi, S. Y., Lin, R. Y., et al. (2020). Advancing the study of positive psychology: the use of a multifaceted structure of mindfulness for development. Front. Psychol. 11, 1602. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01602

Pleeging, E., Burger, M., and van Exel, J. (2021). The relations between hope and subjective well-being: a literature overview and empirical analysis. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 16, 1019–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11482-019-09802-4

Reppold, C. T., Gurgel, L. G., and Schiavon, C. C. (2015). Research in positive psychology: a systematic literature review. Psico-USF 20, 275–285. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200208

Sari, S. P., Agustin, M., Wijayanti, D. Y., Sarjana, W., Afrikhah, U., and Choe, K. (2021). Mediating effect of hope on the relationship between depression and recovery in persons with schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 12, 627588. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.627588

Scheier, M., and Carver, C. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol., 4, 219–247. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219

Schiavon, C. C., Marchetti, E., Gurgel, L. G., Busnello, F. M., and Reppold, C. T. (2017). Optimism and hope in chronic disease: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 7, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02022

Schug, C., Morawa, E., Geiser, F., Hiebel, N., Beschoner, P., Jerg-Bretzke, L., et al. (2021). Social support and optimism as protective factors for mental health among 7765 healthcare workers in germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of the VOICE Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 3827. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073827

Snyder, C. (2002). Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol. Inq. 13, 249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

Teixeira, S., Coelho, J., Sequeira, C., Lluch i Canut, M. T., and Ferré-Grau, C. (2019). The effectiveness of positive mental health programs in adults: a systematic review. Health Soc. Care Commun. 27, 1126–1134. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12776

Tomasulo, D. (2020). Learned Hopefulness: The Power of Positivity to Overcome Depression. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.

Vos, L., Habibović, M., Nyklíček, I., Smeets, T., and Mertens, G. (2021). Optimism, mindfulness, and resilience as potential protective factors for the mental health consequences of fear of the coronavirus. Psychiatry Res. 300, 113927. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113927

Keywords: hope, positive mental health, mental health literacy, nursing, optimism

Citation: Laranjeira C and Querido A (2022) Hope and Optimism as an Opportunity to Improve the “Positive Mental Health” Demand. Front. Psychol. 13:827320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.827320

Received: 01 December 2021; Accepted: 01 February 2022;

Published: 24 February 2022.

Edited by:

Carlos Sequeira, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Dan Tomasulo, Columbia University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Laranjeira and Querido. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlos Laranjeira, Y2FybG9zLmxhcmFuamVpcmFAaXBsZWlyaWEucHQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.