- 1Department of Business Administration, Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

- 2Department of Management Studies, Bahria University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 3Department of Management Sciences, National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad, Pakistan

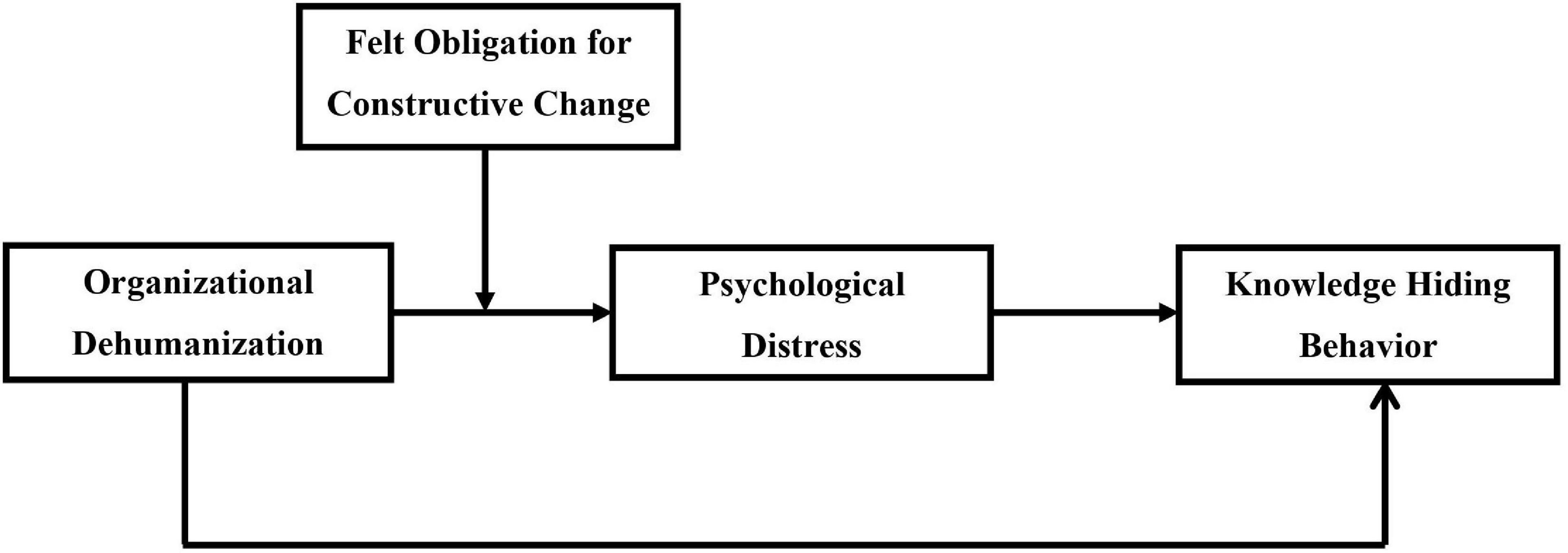

Knowledge hiding has become an alarming issue for the organizations. Knowledge hiding is an employee’s intentional attempt to conceal knowledge requested by others at the workplace. Employee knowledge hiding significantly influences an organization’s effective functioning. This research is an attempt to extend previous work on antecedents of knowledge hiding. Drawing on conservation of resources theory, it is proposed that receiving poor treatment by organizations in the form of organizational dehumanization creates psychological distress among employees toward the organization. Distress among workers in turn intervenes the path and increases the likelihood of engaging in knowledge hiding behaviors. An employee’s felt obligation for constructive change (FOCC) may moderate the relationship between organizational dehumanization and employee psychological distress. Data for the current study were collected from 245 employees of the telecommunication sector in three-time lags. The results support the direct and indirect effect of organizational dehumanization on employee knowledge hiding behaviors through the mediation of psychological distress. The results also support the moderation of FOCC between organizational dehumanization and psychological distress. Furthermore, the findings of the study may help organizational practitioners and managers about the value of effective organizational climate and practices for better organizational functioning through knowledge sharing and providing insight into undesirable repercussions of organizational dehumanization. Implications for organizations and practitioners are discussed.

Introduction

In this era of competition, the organizations are striving to gain a competitive advantage over others by increasing their productivity (Kuranchie-Mensah and Amponsah-Tawiah, 2016). In this competition race, the organizations are pressuring their employees with excessive workloads and mechanical structure while ignoring the humanistic perspective, thus resulting in employee mistreatment. In the past, most of these “negative or abusive” behaviors were attributed to the leadership style of an organizational leader, such as abusive supervision, tyrant leadership, despotic leadership, and perceiving organizations as innocent spectators (Kemper, 2016; Akram et al., 2019; Hussain et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; He et al., 2021). Previously some researchers found that an organization can be a source of abuse, hindrance, obstruction, or harm to its employees (Gibney et al., 2009). For example, work overload, lack of organizational support, workplace bullying, lower social support from bosses and peers (Agarwal et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). The dark side of employee behaviors has emerged as the gravest issue in organizations, depleting employee psychological resources (Irshad and Bashir, 2020; Yao et al., 2020; Pereira and Mohiya, 2021).

When employees perceive their relationship with the organization as harmful and mistreated by the organization, it leads to negative employee and organizational outcomes (Caesens et al., 2017; Morsch et al., 2020; Sarwar and Muhammad, 2020; Wang et al., 2021).

One concept that has recently emerged as destructive for both employees and organizations is organizational dehumanization. Organizational dehumanization refers to the perception of employees about organizational mistreatment as a result of their experience with the organization by treating them like machines rather than humans, having less concern for their respects, and handling them as a means to achieve organizational objectives with less capacity for willingness and sentiments (Caesens and Stinglhamber, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Sainz et al., 2021).

Organizational dehumanization has been studied with the various negative employee and organizational outcomes. For instance, Sarwar and Muhammad (2020) found that organizational dehumanization reduces organizational performance. Further, Sarwar et al. (2021a) stated that organizational dehumanization is the potential predictor of deviant behavior. The adverse outcomes of organizational dehumanization are understandable, and however, employees cannot always reciprocate the mistreatment of the organization overtly. The covert deviant behaviors of employees include time theft, procrastination, and knowledge hiding (Robinson and Bennett, 1995; Webster et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2010; Connelly et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2013; Kang, 2016; Prem et al., 2018; Halberstadt et al., 2019). Some studies have made efforts to understand employees’ less dominant but deviant behavior in response to organizational mistreatments such as employee theft and knowledge hiding (Sarwar and Muhammad, 2020). However, they relied on the mediating mechanism of incivility, which is a visible deviant behavior. Sarwar and Muhammad (2020) also recommend testing other explanatory mechanisms between employees’ dehumanization and knowledge hiding.

The current study aims to investigate knowledge hiding as an outcome of organizational dehumanization through the psychological distress of employees. Knowledge hiding refers to the intentional effort of the employees to conceal their personal and professional knowledge and refrain from sharing with others (Connelly et al., 2012; Kang, 2016). Knowledge hiding refers to withholding of information that is related to the task, using delay tactics in sharing information, intentionally concealing information that is organizationally desired, and not sharing implicit knowledge gained through experience (Serenko and Bontis, 2016; Cerne et al., 2017; Connelly et al., 2019). Employees engage in knowledge hiding behaviors to rationalize the ill-treatment of dehumanization and downplay the distress. In response to organizational mistreatment in the form of perceived dehumanization, employees might reciprocate by concealing their knowledge from sharing with others and not sharing innovative achievements. Organizational dehumanization is also a reason for psychological distress in employees. When employees feel that their organization is treating them like robots and has less care for their interests, it creates psychological strain and stress (Robinson et al., 2004; Glicken and Robinson, 2013). Psychological distress is a feeling of emotional discomfort in response to some stressor (Hilton et al., 2008; Ozaki et al., 2012; Sidorchuk et al., 2017; James et al., 2018; Dodia and Parashar, 2020; Viertiö et al., 2021). An employee’s psychological distress is proposed as an explanatory mechanism between the relationship between organizational dehumanization and knowledge hiding of employees.

Further, the personal orientation of employees is a critical factor in deciding employees’ responses to organizational mistreatment. Felt obligation for constructive change (FOCC) refers to the orientation of employees in which they feel responsible for bringing progressive changes in the organization (Phillips-Miller and Morrison, 1999; Fuller et al., 2006). FOCC brings organizations many fruitful outcomes that become the reason for employees’ personal developments and organizational progressions (Fuller et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2012; Mallory et al., 2020). FOCC is used as a valuable resource that is used as a shield against losses experienced by dehumanization practices. As per conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018), FOCC being a valuable resource will determine individual appraisals of stressful situations and experience less distress if they have high FOCC.

The employees who experience a high level of FOCC appraise the problem with a solution approach rather than an avoidant approach (Liang et al., 2012; Bhatti et al., 2020). Considering the importance of FOCC as a psychological state, it helps as a coping mechanism to deal with psychological distress. Through personal experience, the workers recognize what is important for their sheer survival. The COR theory implies that FOCC will help individuals to replace or restore the loss they have experienced in dehumanization. In short, the COR theory postulates that individuals strive to obtain, retain, foster, and protect those things they centrally value (i.e., resources) (Chen and Fellenz, 2020; Guo et al., 2020). Hence, it is proposed that employees feel an obligation for constructive changes that will reduce the negative effect of organizational dehumanization on psychological distress and ultimately the knowledge hiding behavior of employees.

The COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) also supports our proposed model. According to the COR theory, employees strive to preserve their resources from stressor or stressful condition, and frequent exposure to stressor causes stress due to loss of valuable resources followed by the defense mechanism of employees to prevent further loss of resources (Holmgreen et al., 2017). Additionally, the COR theory also posits that investing new resources can offset the loss of resources to organizational stressors. Organizational dehumanization acts as a stressor and consumes psychological resources by causing psychological distress. As a result of resource loss to dehumanization, employees use defensive tactics to regain further resources or stop the resources loss cycle. These defensive techniques might be in the form of knowledge hiding behaviors. Further, FOCC is a valuable resource of employees that can be invested to reduce the damages of stressor organizational dehumanization. Thus, employees with high FOCC will be less vulnerable to organizational dehumanization than others due to their additional resources pool.

The current study contributes to the literature in multiple ways. First, knowledge hiding is proposed as a critical but less dominant deviant behavior resulting from organizational dehumanization. Sometimes employees are not able to reciprocate with the same intensity to organizational mistreatments. Second, psychological distress is proposed as a possible mediator in organizational dehumanization. Previous studies have investigated observable behaviors and attitudes as explanatory mechanisms, while psychological distress is employee’s less visible emotional state that might result in less visible behaviors. Third, FOCC has proposed a potential boundary condition to dampen the effect of organizational dehumanization on psychological distress. Last, the current study has extended the implication of COR theory in the organizational mistreatment literature.

Literature Review

Organizational Dehumanization and Knowledge Hiding Behavior

When organizations objectify an employee, it thwarts an individual’s personal needs. The employees perceive to become means to achieve organizational goals (Brison et al., 2021; Sainz and Baldissarri, 2021). They feel like a means to meet organizational ends. But such means make them feel like an instrument or nothing less than a robot (Caesens et al., 2017, 2019; Nguyen and Stinglhamber, 2021; Sainz et al., 2021). But at the same time, they may experience cognitive, physical, and emotional strains. The strains deplete resources and are being used to protect what they already have rather than pursuing personal needs. These stressors subsequently damage productive behaviors (Caesens et al., 2017, 2019). So through this mechanism, we are trying to understand the remitting effect of dehumanization. The underlying mechanism of transmitting the effect of organization dehumanization on knowledge hiding can be via psychological distress.

The perception of being dehumanized has detrimental effects on different work attitudes and behaviors between the employee–organization relationships (Sainz and Baldissarri, 2021). Humans have been seen as commodities rather than “human capital” (Väyrynen and Laari-Salmela, 2015). To rationalize the ill-treatment of an organization, they behave negatively to downplay the distress, which also has a profound impact on employee psychological wellbeing (Farh and Chen, 2014; Hirschle and Gondim, 2020; Walsh and Arnold, 2020). Individuals may fail to maintain their normative behavior due to loss of self-resources caused by dehumanization (Haslam and Loughnan, 2014). When the reasons for dehumanization become incomprehensible and when the employees cannot cognitively process the motives, they indulge in deviance (Guo et al., 2020; Sarwar et al., 2021b). Work sabotage, showing up late, organizational theft, absenteeism, and disclosing company secrets are examples of counterproductive work behavior (Bennett et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2018; Yasir and Rasli, 2018).

Previous studies found that the individuals will try to cope with the undermining feeling by protecting their limited resources (Connelly et al., 2012; Dahling, 2017; Feng and Wang, 2019). Following this logic, we argue that organizational dehumanization will result in detrimental psychological consequences in the form of psychological distress, which will then instigate sufferers to take knowledge hiding as a form of resource loss preventing actions (Jiang et al., 2019; Bari et al., 2020; Rezwan and Takahashi, 2021). Knowledge hiding is being studied as a dormant form of deviant behavior responding to organizational stressors (Škerlavaj et al., 2018; Livne-Ofer et al., 2019; Khoreva and Wechtler, 2020). Drawing on the COR perspective (Hobfoll, 2001), employees become defensive and indulge in coping strategies.

H1: Organizational dehumanization is positively associated with knowledge hiding behavior of employees.

Mediation of Psychological Distress Between Organizational Dehumanization and Knowledge Hiding Behavior of Employees

Drawing on the proposition that organization dehumanization may encourage knowledge hiding behavior, we postulate that psychological distress mediates the relationship between organizational dehumanization and the knowledge hiding behavior of employees. Individuals feel distressed when high-order need of relatedness and compassion are denied (Bell and Khoury, 2011; Caesens et al., 2017). Based on the COR theory, organization dehumanization is a resource-draining factor (Volpato and Andrighetto, 2015). The feeling of psychological distress becomes high when the perception of dehumanization is internalized. Bell and Khoury (2016) found that the feelings of disrespect, humiliation, and neglect will enhance dehumanization making employees less socially valuable (Christoff, 2014; Huo et al., 2016). Sarwar and Muhammad (2020) explained in their work that such mechanistic dehumanizing experiences may hinder the process of information sharing in the organization and may inculcate knowledge hiding behavior (Zhang and Min, 2021; Zhao and Jiang, 2021). Workers are not in a powerful position to reciprocate similarly, so they take discourse in indulging in deviant behaviors (Foulk et al., 2016). Knowledge hiding is considered a reaction to the organization’s dehumanization by intentionally withholding necessary organizational knowledge (Burmeister et al., 2019; Farooq and Sultana, 2021).

In a situation of psychological distress, likely, a worker may not be able to suffice the request of any knowledge sharing to guard against the already left energy and time (Khoreva and Wechtler, 2020; Rezwan and Takahashi, 2021). Similarly, Vayrynen and Laari-Salmela (2018) found that employees’ perception of dehumanization brings employees into a negative mental state that indicates psychological distress. Despite these findings, we do not know much about how organizational dehumanization might affect knowledge hiding. Given that, dehumanization has devastating effects by creating distress. Therefore, we seek to examine the antecedents of knowledge hiding from organizational dehumanization mainly through the explanatory mechanism of psychological distress.

H2: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between organizational dehumanization and knowledge hiding behavior of employees.

Moderation of Felt Obligation for Constructive Change

Drawing on the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011), dehumanization depletes our cognitive resources and may alienate one’s attitude toward undesirable behavior (Ridner, 2004; Lee et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2020). An individual’s disposition to perceive a negative stimulus in the environment influences our reaction to the event (Judge and Larsen, 2001; Wu and Griffin, 2012). One such individual orientation is the FOCC. It is an individual’s orientation in which employees take outstanding intrinsic inspiration from their work and feel responsible for the assigned task (Fredrickson, 2001). Such disposition is considered very prototypical of a progressive mindset (Mossakowski and Zhang, 2014). We argue that FOCC will lessen the perception that the organization dehumanizes them. Therefore, we can postulate that FOCC will convey to employees that they are in charge of their work and can add value and worth, reducing organizational dehumanization perceptions. In summary, FOCC is an individual’s disposition that will ease the dehumanization’s stressful condition (Jahanzeb et al., 2020; Sainz et al., 2021). FOCC is explained as the employees’ personal sense of responsibility for initiating progressive organizational changes (Fuller et al., 2006). FOCC is essential for ensuring employees’ personal development and organizational progression (Mallory et al., 2020). This depicts that FOCC is a valuable personal-psychological resource that could buffer the negative relation between dehumanization and psychological distress. As explained in the COR theory, the employees strive to preserve their resources from stressors or stressful conditions to ensure their well-being and distance themselves from threats to well-being. Frequent exposure to this organizational dehumanization as a stressor causes psychological distress to employees. The COR theory proposed that in such a stressful environment, employees’ defense mechanisms are activated to prevent or buffer the further loss of resources. The defense mechanism in a given scenario is the individual personal resource, which is FOCC, which thwarts the resource loss cycle (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009; Holmgreen et al., 2017; Pignata et al., 2017).

Given that psychological distress plays a critical role in regulating employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Lee et al., 2018), not every person will respond in the same manner when faced with organizational dehumanization (Lebel, 2017; Kittel et al., 2021). FOCC will try to preserve the loss of individual psychological and physical resources (Fuller et al., 2006) by mitigating the negative effects of organizational dehumanization. Having support from self-regulation theory (Bandura, 1991), we expect that FOCC will act as a boundary condition between dehumanization and psychological distress (Liang et al., 2012). Particularly when faced with dehumanization, employees with high FOCC are more likely to interpret such situations as less intense (Abbasi et al., 2021). They will perceive themselves to be in control of themselves, having proactive conceptualization of the problem (Li et al., 2020) and will experience less resource drain compared with those who have low FOCC. The proactive aspect of personality becomes a protective cover against the stressors in the environment (Bajaba et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2021). They can appraise the situation more optimistically, thus promoting adaptive behaviors (Mazzetti et al., 2019a). Control is one of the characteristics of a hardy personality that considers change as desirable and natural (Mazzetti et al., 2019b).

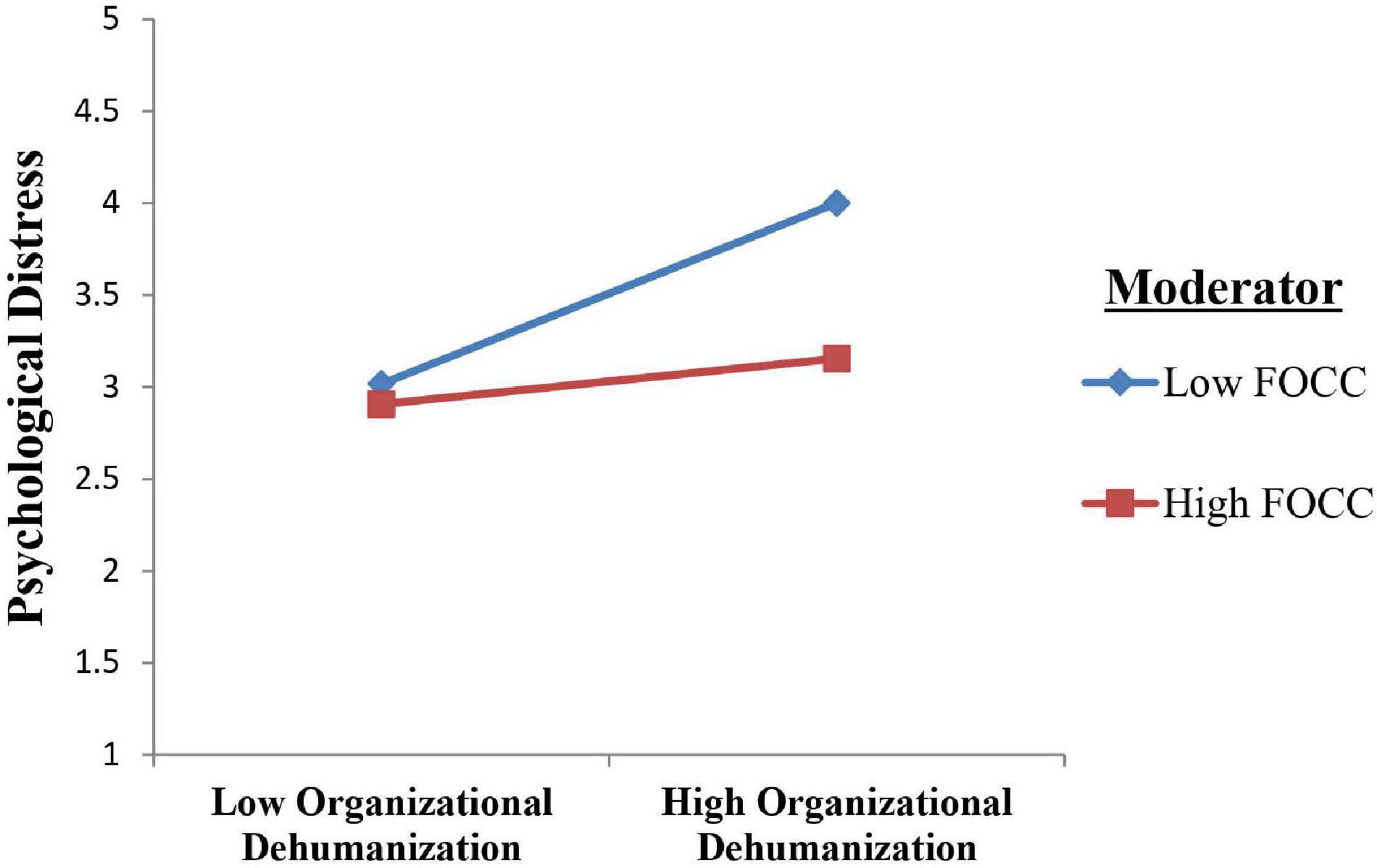

H3: Felt obligation for constructive changes moderates the relationship between organizational dehumanization and psychological distress, such that the relationship will be weaker when FOCC is high and stronger when FOCC is low.

Figure 1 shows the proposed model.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Procedure

A self-survey was administered in the service industry, particularly in the telecommunication sector. Concern for knowledge management among employees of the telecom sector is relatively high (Jyoti et al., 2011; Jyoti and Rani, 2017). Increasing demands for innovation and a global knowledge-based economy have fostered the telecom sector to understand that knowledge management can be the real asset to remain competitive and ahead of competitors (Yen et al., 2021). The knowledge database must be maintained by IT specialists so that tasks can be performed effectively (Bender and Fish, 2000). The sustainability and competitive edge of the telecom sector is highly dependent on knowledge management (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). It has also been proposed by Fey and Furu (2008) that competitive advantage is derived from leveraging knowledge. In a study by Wang and Noe (2010), it was reported that 90% of respondents from the telecom sector intended to conduct a study on knowledge management. Therefore, data were taken from employees of the telecom sector. To avoid the common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012), which is possible in survey studies (Podsakoff et al., 2003), certain steps at the design stage were ensured, and data were collected in time lags.

Data on predictor variables, that is, organizational dehumanization and moderator variables that are felt as obligations for constructive change, were collected at time lag 1 (T1) at the start of February 2021. Being a time lag study, response on mediator variable, that is, psychological distress, was collected in mid of March 2021. Response on the dependent variable as knowledge hiding behavior was collected in time lag 3 at the start of April 2021. Data collection on all the variables from three-time lags was completed at the end of April 2021. Convenience sampling, a non-random sampling technique, was used for data collection. The size of the sample was determined by G*Power version 3.1.9.4 (Faul et al., 2009). A priori sample size was calculated as 107, which is much lesser than the current study sample, that is, 245. This technique is being used by most recent studies and getting the attention of researchers (Irshad et al., 2021b; Qasim et al., 2021). Data were collected through visiting the various organization in an offline mode. Approval was taken from Human Resource offices of telecom organizations to contact their employees. A cover letter explaining the study details was attached to the questionnaires, and employees were assured of their anonymity. Some employees were interested in knowing our study’s findings, so they were assured that findings would be shared with them too. An email address of the corresponding author was mentioned on the cover letter provided along with the questionnaire. So if the respondents are interested in inquiring, they can easily contact us through the corresponding email address. All measures were in English as this is the official language of Pakistan and used the medium for conveying the knowledge in schools and universities. Previous studies have also used English for conducting surveys and administering questionnaires (Um-e-Rubbab and Naqvi, 2020; Irshad et al., 2021a; Majeed et al., 2021).

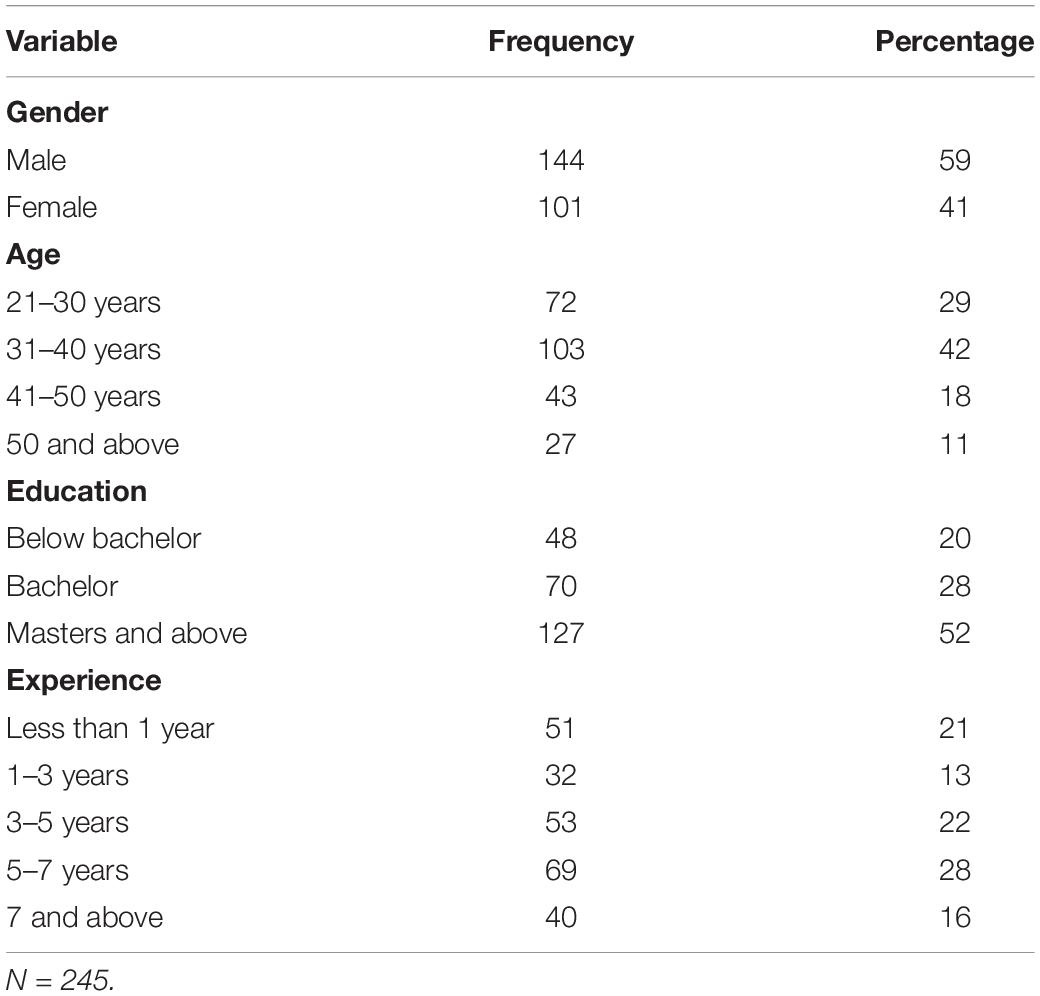

At T1, 500 questionnaires were distributed and 462 were returned with a response rate of 92%. After a gap of 1 month, the same employees were contacted again and were required to respond on knowledge hiding for T2. At T2, 370 questionnaires were received back. At T3, response on felt obligation was collected from the same employees, and 305 questionnaires were received. Thirty-eight questionnaires were discarded because they were incomplete. So the final response rate was 48% with 267 well-filled questionnaires. Out of the 245 respondents, 144 were male and 101 respondents were female. A total of 71% of respondents were between 21 and 40 years old, 80% had bachelors or more than bachelors degree, 44% had more than 5 years experience, 22% had an experience of 3–5 years, 13% had an experience of 1–3 years, while the remaining had less than 1 year experience (see Table 1).

Measures

The scales of perceived organizational dehumanization, perceived distress, knowledge hiding, and felt obligation were adopted from previous studies as mentioned below.

Perceived Organizational Dehumanization

To measure the employees’ perception of organizational dehumanization, 11-items scale of Caesens et al. (2017) was used. Sample items include “My organization treats me as if I were a robot.” and “My organization considers me as a number.” The respondents were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 for strongly disagree and 5 for strongly agree.

Psychological Distress

A 10-items scale was adopted from Kessler et al. (2003) to measure the psychological distress of employees. Specifically, the employees were provided with a series of statements like “In the past 4 weeks, about how often did you feel tired out for no good reason? 2. In the past 4 weeks, about how often did you feel nervous?” on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 for none of the time and 5 for all of the time.

Felt Obligation for Constructive Change

A seven-items scale adapted from the Eisenberger et al. (2001) was used. Sample item includes “I owe it to the organization to do whatever I can to come up with ideas/solutions to achieve its goals.” Employees rated a five-point scale on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 for strongly disagree and 5 for strongly agree.

Knowledge Hiding

A three-items scale adopted from Peng (2013) was used to measure knowledge hiding. Employees were provided with statements like “Do not want to transform personal knowledge and experience into organizational knowledge” and “Do not share innovative achievements” on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 for strongly disagree and 5 for strongly agree.

Results

Correlation Analysis

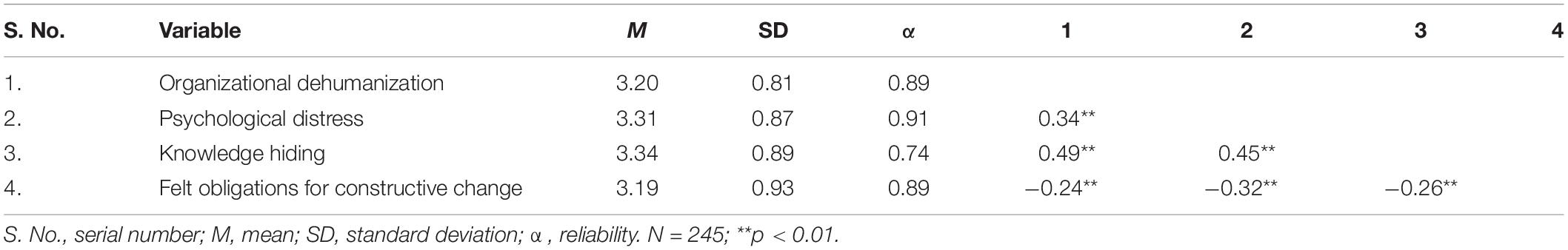

Table 2 provides the mean, SDs, reliabilities, and correlations among the study variables. An ANOVA was performed to check the variance in perceived distress and knowledge hiding due to demographic variables, that is, gender, age, education, and experience of respondents. Variance accounted for all demographic variables. Independent variables were found to be non-significant. Hence, all the demographic variables were not controlled in the study and were excluded in further analysis. Perceived organizational dehumanization is significantly correlated with perceived distress (r = 0.34**, p < 0.01) and employee knowledge hiding (r = 0.49**, p < 0.01). The FOCC was found to be significantly correlated with perceived distress (r = −0.32**, p < 0.01) and employee knowledge hiding (r = −0.26*, p < 0.01). Knowledge hiding was significantly correlated with perceived distress (r = 0.45**, p < 0.01).

Hypothesis Testing

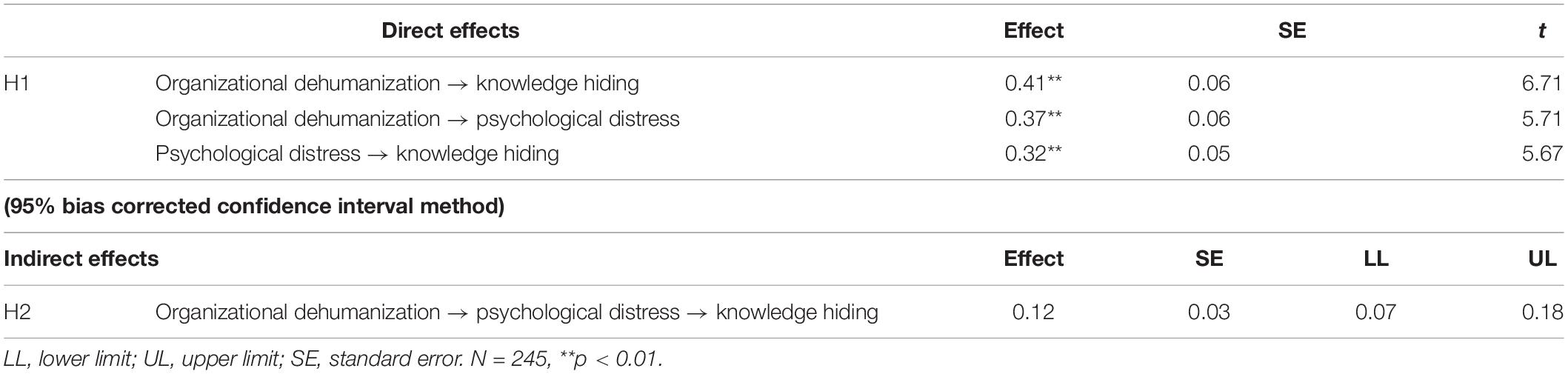

Table 3 provides the direct, mediation, and moderation hypotheses. Hayes (2017) Model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used to check the mediation, and Model 1 was used to check the moderation hypothesis. In line with Hypothesis 1, perceived organization dehumanization was significantly associated with knowledge hiding (β = 0.41, p < 0.01); thus, the H1 of the study was accepted. Furthermore, perceived organizational dehumanization was significantly associated with perceived distress (β = 0.37, p < 0.01), and perceived distress was significantly associated with knowledge hiding (β = 0.32, p < 0.01). The indirect effects confirm the significant mediating role of perceived distress in the relationship between perceived organizational dehumanization and knowledge hiding [indirect effect = 0.12, 95% CI with lower limit (LL) = 0.07 and upper limit (UL) = 0.18]. The LL and UL of the 95% CI both contain non-zero values (Hair et al., 2014). Hence, H2 is also accepted.

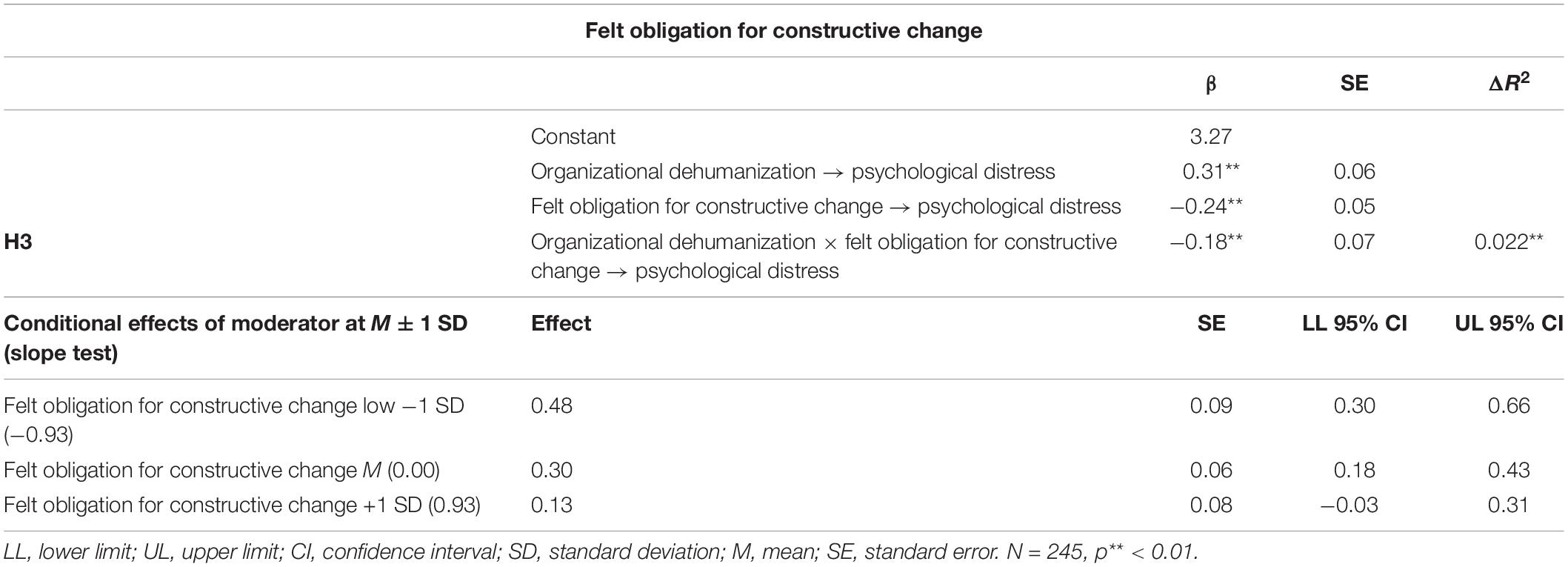

Table 4 presents the result for moderation analysis. Before testing Hypothesis 3, perceived organizational dehumanization and FOCC were mean-centered (Aiken et al., 1991). The interaction effect of perceived organizational dehumanization and FOCC was significant (β = −0.18, p < 0.01). Hence, H3 is also supported. Table 4 and Figure 2 also show the conditional effect of organizational dehumanization on psychological distress via FOCC getting weaker at high values of FOCC (±1 SD from the mean).

Figure 2. Felt obligation for constructive change (FOCC) dampens the positive relationship between organizational dehumanization and psychological distress.

Discussion

In the age of global pandemic, the organization’s sustainability has become the subject of attention as it has led to fierce competition for survival and productivity (Al Aina and Atan, 2020; Keshky et al., 2020; Ibn-Mohammed et al., 2021). In this crisis time, the organizations are mostly shifting toward resource optimization strategies; they end up falling for opting for mechanistic culture and styles of leadership rather than choosing humanistic cultures. Organizations invest a lot in knowledge management and offer many incentives to promote knowledge at various levels, from employees at the same level and from subordinates to managers and vice versa. Hence, employees do not share knowledge and try to hold information despite the organizational efforts (Connelly et al., 2012).

Our study findings suggest that one reason for all efforts and resources spent on making employees share the knowledge go in vain can be the certain organizational practices and behaviors. When employees perceive that they are being treated as robots by the organization, they start acting like robots reciprocating the organizational maltreatment. The maltreatment of employees by the organization is termed as organizational dehumanization. Organizational dehumanization kills employees’ connectedness and belongingness to the organization, and employees prefer hiding their knowledge to justify organizational ill-treatment. Organizational dehumanization serves as a stressor and tends to drain employees psychologically. Since knowledge is an important resource and human beings strive to conserve and retain valuable resources (Hobfoll, 1989). According to Hobfoll (1989), when an individual perceives that an external stressor threatens his/her resources (e.g., psychological, social, and physical), he/she would try to protect and conserve his/her valuables by engaging in certain behaviors. In the current scenario, employee knowledge hiding is his/her retaliatory behavior in response to organizational dehumanization. When employees perceive ill-treatment by the organization, being abused or being used as objects by the organization, they start engaging in retaliation (Khalid et al., 2018), considering their knowledge as a tool to conserve and hold.

Glancing from the COR theory perspective, it proposes that the prevalence of such dehumanizing cultures can create psychological distress or strain among the employees and abstain from further psychological distress and personal resource depletion; the employees mostly exhibit defensive behaviors on their job, such as knowledge hiding. The theory also postulates that the employees can buffer this negative relationship between job demands and psychological strains if they carry certain personal resources to alleviate themselves from this vicious resource depletion cycle (Holmgreen et al., 2017).

This study proves that dehumanizing cultures positively related to increasing employees’ distress, which further increases knowledge hiding behaviors among employees. This study also contributes to the existing literature and theory by investigating the moderating role of the FOCC by weakening the strong relationship between organizational dehumanization and employee distress. The study findings also showed the negative relationship between FOCC and employee psychological distress. FOCC is explained as the employee’s personal sense of responsibility for initiating progressive organizational changes (Fuller et al., 2006). The COR theory proposed that employees’ defense mechanisms are activated in such a stressful environment to prevent or buffer further loss of resources. The defense mechanism in a given scenario is the individual personal resource, which is FOCC, which thwarts the resource loss cycle (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009; Holmgreen et al., 2017; Pignata et al., 2017).

This current study offers several insights and guidelines for practitioners. First, it highlights that any organization’s sustainability, competition, and productivity can never reside in shifting toward mechanistic cultures; instead, it requires innovative cultures that premise upon knowledge-sharing cultures. Such short-term thinking of dehumanizing organizations such as abusive supervision could worsen the organization and ignite vicious cycles of resource depletion among the organizations.

Second, the dehumanization cultures are strongly related to creating employees’ psychological discomfort and distress. Studies already show that distressed employees can never be engaged in productive outputs like innovation (Tepper et al., 2007; Park et al., 2018). Third, this study also provides evidence that distressed employees end up safeguarding themselves by engaging in defensive behaviors such as knowledge hiding, which can destroy the spirit of creativity and innovation and diminish any organization’s future growth and survival.

Last, this study also provides contextual solutions and insight to organizations that have mechanistic cultures or have high job demands structures; they should recruit employees who have a strong sense of responsibility or feel an obligation toward change because such individuals have such strong aspirations that despite having high job pressures or negative work cultures their inner state of self-responsibility does not get them effected by these job constraints. Hence, they do not feel distressed about their job. This study can also lead to new directions that individuals having felt an obligation for change could effectively redirect the dehumanizing organization toward positive humanistic cultures. Future studies could also identify other moderators like self-efficacy, organizational commitment, and some personality characteristics that could help to buffer the high job demand constraints on employees.

Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study provides evident theoretical and methodological contributions; however, it also carries certain limitations. First, this study observed the impact of organizational dehumanization and psychological distress on only one dependent variable: knowledge hiding behavior. Future studies could also include other counterproductive work behaviors, such as an important outcome in the form of employee procrastination can be studied as the possible outcome of organization dehumanization too. Second, FOCC was taken as a personal psychological resource.

In contrast, other personal resources like resilience, hope, and psychological capital or certain personality traits can also be studied as possible strengthening and buffering effects. This study followed a time-lagged methodology for data collection, and future researches should consider longitudinal studies in other sectors and different contexts.

Conclusion

The current study focuses on the effects of dehumanization practices in the telecommunication sector, although lacking extreme symbolic violence. But other factors lie under the surface. Certain practices are invisible and difficult to change. As a whole, the result of our study suggests that organizational dehumanization should not be left unchecked. Otherwise, it can create a stressful environment damaging employees’ mental state. It may lead to deviant behavior in the form of knowledge hiding. The violation of basic humanness is detrimental for individuals and can also have adverse effects for organizations by the intentional act of concealing vital information. Environmental influence or individual disposition (FOCC) reduces the feeling of being treated like an instrument or tool.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the FJWU Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, S. G., Shabbir, M. S., Abbas, M., and Tahir, M. S. (2021). HPWS and knowledge sharing behavior: the role of psychological empowerment and organizational identification in public sector banks. J. Pub. Affairs 21:2512.

Agarwal, U. A., Avey, J., and Wu, K. (2021). How and when abusive supervision influences knowledge hiding behavior: evidence from India. J. Knowl. Manag. 26, 209–231. doi: 10.1108/jkm-10-2020-0789

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., and Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple Regression: TESTING and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Akram, Z., Li, Y., and Akram, U. (2019). When employees are emotionally exhausted due to abusive supervision. A conservation-of-resources perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 16:3300.

Al Aina, R., and Atan, T. (2020). The impact of implementing talent management practices on sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability 12:8372. doi: 10.3390/su12208372

Alavi, M., and Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quar. 1, 107–136.

Bajaba, S., Bajaba, A., and Fuller, B. (2021). Enduring exploitative leaders at work: the buffering role of proactive personality on employee job strain. Organ. Manag. J. doi: 10.1108/OMJ-11-2020-1090 [Epub ahead of print].

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proces. 50, 248–287. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-l

Bari, M. W., Ghaffar, M., and Ahmad, B. (2020). Knowledge-hiding behaviors and employees’ silence: mediating role of psychological contract breach. J. Knowl. Manag. 24, 2171–2194. doi: 10.1108/jkm-02-2020-0149

Bell, C. M., and Khoury, C. (2011). Dehumanization, deindividuation, anomie and organizational justice. Emerg. Perspect. Organiz. Just. Ethics Res. Soc. Issues Manag. 7, 169–200.

Bell, C. M., and Khoury, C. (2016). Organizational powerlessness, dehumanization, and gendered effects of procedural justice. J. Manage. Psychol. 31, 570–585. doi: 10.1108/JMP-09-2014-0267

Bender, S., and Fish, A. (2000). The transfer of knowledge and the retention of expertise: the continuing need for global assignments. J. Knowl. Manag. 4, 125–137. doi: 10.1108/13673270010372251

Bennett, R. J., Marasi, S., and Locklear, L. (2019). “Workplace deviance,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 1–25.

Bhatti, Z. A., Arain, G. A., Akram, M. S., Fang, Y. H., and Yasin, H. M. (2020). Constructive voice behavior for social change on social networking sites: a reflection of moral identity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 157:120101. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120101

Brison, N., Stinglhamber, F., and Caesens, G. (2021). “Organizational dehumanization,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Burmeister, A., Fasbender, U., and Gerpott, F. H. (2019). Consequences of knowledge hiding: the differential compensatory effects of guilt and shame. J. Occupat. Organiz. Psychol. 92, 281–304. doi: 10.1111/joop.12249

Caesens, G., and Stinglhamber, F. (2019). The relationship between organizational dehumanization and outcomes: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. J. Occupat. Environ. Med. 61, 699–703. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001638

Caesens, G., Nguyen, N., and Stinglhamber, F. (2019). Abusive supervision and organizational dehumanization. J. Bus. Psychol. 34, 709–728.

Caesens, G., Stinglhamber, F., Demoulin, S., and De Wilde, M. (2017). Perceived organizational support and employees’ well-being: the mediating role of organizational dehumanization. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 26, 527–540. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312551

Cerne, M., Hernaus, T., Dysvik, A., and Skerlavaj, M. (2017). The role of multi-level synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and Bibliography 175 job characteristics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 27, 281–299.

Chen, C.-T., Hu, H.-H., and Sunny, K. B. (2018). Shaping the organisational citizenship behavior or workplace deviance: key determining factors in the hospitality workforce. J. Hospital. Tour. Manag. 35, 1–8.

Chen, I. S., and Fellenz, M. R. (2020). Personal resources and personal demands for work engagement: evidence from employees in the service industry. Int. J. Hospital. Manag. 90:102600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102600

Christoff, K. (2014). Dehumanization in organizational settings: some scientific and ethical considerations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:748. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00748

Connelly, C. E., Černe, M., Dysvik, A., and Škerlavaj, M. (2019). Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 40, 779–782.

Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., and Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 33, 64–88. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748237

Dahling, J. J. (2017). Exhausted, mistreated, or indifferent? Explaining deviance from emotional display rules at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 26, 171–182. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2016.1229307

Dodia, P., and Parashar, N. (2020). Shift-work job stress, psychological distress, and job satisfaction among employees. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 8, 1215–1223.

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., and Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 86:42. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

Farh, C. I., and Chen, Z. (2014). Beyond the individual victim: MULTILEVEL consequences of abusive supervision in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 99:1074. doi: 10.1037/a0037636

Farooq, R., and Sultana, A. (2021). Abusive supervision and its relationship with knowledge hiding: the mediating role of distrust. Int. J. Innov. Sci. doi: 10.1108/IJIS-08-2020-0121 [Epub ahead of print].

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., and Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Feng, J., and Wang, C. (2019). Does abusive supervision always promote employees to hide knowledge? From both reactance and COR perspectives. J. Knowl. Manag. 23, 1455–1474.

Fey, C. F., and Furu, P. (2008). Top management incentive compensation and Knowledge sharing in multinational corporations. Strat. Manag. J. 29, 1301–1323. doi: 10.1002/smj.712

Foulk, T., Woolum, A., and Erez, A. (2016). Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: the contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 101:50. doi: 10.1037/apl0000037

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56:218. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., and Hester, K. (2006). Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 1089–1120. doi: 10.1002/job.408

Gibney, R., Zagenczyk, T. J., and Masters, M. F. (2009). The negative aspects of social exchange: an introduction to perceived organizational obstruction. Group Organ. Manag. 34, 665–697. doi: 10.1177/1059601109350987

Glicken, M. D., and Robinson, B. (2013). Treating Worker Dissatisfaction During Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Guo, L., Cheng, K., and Luo, J. (2020). The effect of exploitative leadership on knowledge hiding: a conservation of resources perspective. Leader. Organ. Dev. J. 42, 83–98. doi: 10.1108/lodj-03-2020-0085

Hair, J. F. Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., and Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 26, 106–121. doi: 10.1108/ebr-10-2013-0128

Halberstadt, J., Timm, J.-M., Kraus, S., and Gundolf, K. (2019). Skills and knowledge management in higher education: how service learning can contribute to social entrepreneurial competence development. J. Knowl. Manag. 23, 1925–1948. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Haslam, N., and Loughnan, S. (2014). Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65, 399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford publications.

He, Q., Wu, M., Wu, W., and Fu, J. (2021). The effect of abusive supervision on employees’ work procrastination behavior. Front. Psychol. 12:113. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.596704

Hilton, M. F., Whiteford, H. A., Sheridan, J. S., Cleary, C. M., Chant, D. C., Wang, P. S., et al. (2008). The prevalence of psychological distress in employees and associated occupational risk factors. J. Occupat. Environ. Med. 50, 746–757. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817e9171

Hirschle, A. L. T., and Gondim, S. M. G. (2020). Stress and well-being at work: a literature review. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 25, 2721–2736.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44:513. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., and Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71501-0

Holmgreen, L., Tirone, V., Gerhart, J., and Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Conservation of resources theory. Handb. Stress Health Guide Res. Pract. 7, 443–457.

Huo, W., Cai, Z., Luo, J., Men, C., and Jia, R. (2016). Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: a multi-level study of r&d teams knowledge hiding behavior. J. Knowl. Manag. 20, 880–897.

Hussain, K., Abbas, Z., Gulzar, S., Jibril, A. B., and Hussain, A. (2020). Examining the impact of abusive supervision on employees’ psychological well-being and turnover intention: the mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 7:1818998. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2020.1818998

Ibn-Mohammed, T., Mustapha, K. B., Godsell, J., Adamu, Z., Babatunde, K. A., Akintade, D. D., et al. (2021). A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 164:105169. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169

Irshad, M., and Bashir, S. (2020). The dark side of organizational identification: a multi-study investigation of negative outcomes. Front. Psychol. 11:2521. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572478

Irshad, M., Bartels, J., Majeed, M., and Bashir, S. (2021a). When breaking the rule becomes necessary: the impact of leader–member exchange quality on nurses pro-social rule-breaking. Nurs. Open 2021, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/nop2.979

Irshad, M., Majeed, M., and Khattak, S. A. (2021b). The combined effect of safety specific transformational leadership and safety consciousness on psychological well-being of healthcare workers. Front. Psychol. 12:2371. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.688463

Jahanzeb, S., Clercq, D. D., and Fatima, T. (2020). Bridging the breach: using positive affectivity to overcome knowledge hiding after contract breaches. J. Psychol. 154, 249–272. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2019.1705235

James, C., Tynan, R., Roach, D., Leigh, L., Oldmeadow, C., Rahman, M., et al. (2018). Correlates of psychological distress among workers in the mining industry in remote Australia: evidence from a multi-site cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 13:e0209377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209377

Jiang, Z., Hu, X., Wang, Z., and Jiang, X. (2019). Knowledge hiding as a barrier to thriving: the mediating role of psychological safety and moderating role of organizational cynicism. J. Organ. Behav. 40, 800–818. doi: 10.1002/job.2358

Judge, T. A., and Larsen, R. J. (2001). Dispositional affect and job satisfaction: a review and theoretical extension. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proces. 86, 67–98. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2001.2973

Jyoti, J., and Rani, A. (2017). High performance work system and organisational performance: role of knowledge management. Pers. Rev. 46, 1770–1795. doi: 10.1108/pr-10-2015-0262

Jyoti, J., Gupta, P., and Kotwal, S. (2011). Impact of knowledge management practices on innovative capacity: a study of telecommunication sector. Vision 15, 315–330.

Kang, S. W. (2016). Knowledge withholding: psychological hindrance to the innovation diffusion within an organisation. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 14, 144–149. doi: 10.1057/kmrp.2014.24

Kemper, S. (2016). Abusive Supervision in the Workplace: An Examination of Current Research and a Proposal for Preventive Measures. Ph.D. thesis. Portland, OR: Portland State University. doi: 10.15760/honors.248

Keshky, E., El Sayed, M., Basyouni, S. S., and Al Sabban, A. M. (2020). Getting through covid-19: the pandemic’s impact on the psychology of sustainability, quality of life, and the global economy–a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 11:3188.

Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E., et al. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 184–189.

Khalid, J., Khaleel, M., Ali, A. J., and Islam, M. S. (2018). Multiple dimensions of emotional intelligence and their impacts on organizational commitment and job performance. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 34, 221–232.

Khoreva, V., and Wechtler, H. (2020). Exploring the consequences of knowledge hiding: an agency theory perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 35, 71–84.

Kittel, A. F., Kunz, R. A., and Seufert, T. (2021). Self-regulation in informal workplace learning: influence of organizational learning culture and job characteristics. Front. Psychol. 12:688. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643748

Kuranchie-Mensah, E. B., and Amponsah-Tawiah, K. (2016). Employee motivation and work performance: a comparative study of mining companies in Ghana. J. Industr. Eng. Manag. (JIEM) 9, 255–309. doi: 10.3926/jiem.1530

Lebel, R. D. (2017). Moving beyond fight and flight: a contingent model of how the emotional regulation of anger and fear sparks proactivity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 42, 190–206. doi: 10.5465/amr.2014.0368

Lee, S., Kim, S. L., and Yun, S. (2018). A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. Leaders. Quar. 29, 403–413. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041240

Li, X., Xue, Y., Liang, H., and Yan, D. (2020). The impact of paradoxical leadership on employee voice behavior: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 11:2408. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.537756

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., and Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad. Manag. J. 55, 71–92. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Livne-Ofer, E., Coyle-Shapiro, J. A., and Pearce, J. L. (2019). Eyes wide open: perceived exploitation and its consequences. Acad. Manag. J. 62, 1989–2018. doi: 10.5465/amj.2017.1421

Majeed, M., Irshad, M., and Bartels, J. (2021). The interactive effect of COVID-19 risk and hospital measures on turnover intentions of healthcare workers: a time-lagged study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:10705. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010705

Mallory, D. B., Rupp, D. E., Pandey, N., and Tay, L. (2020). The effect of employee proactive personality and felt responsibility on individual corporate social responsibility behaviors: the CSR context matters. J. Sustain. Res. 3:582.

Martin, L. E., Brock, M. E., Buckley, M. R., and Ketchen, D. J. Jr. (2010). Time banditry: examining the purloining of time in organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 20, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.013

Mazzetti, G., Simbula, S., Panari, C., Guglielmi, D., and Paolucci, A. (2019a). “Woulda, coulda, shoulda”. workers’ proactivity in the association between emotional demands and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:309. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16183309

Mazzetti, G., Vignoli, M., Petruzziello, G., and Palareti, L. (2019b). The hardier you are, the healthier you become. may hardiness and engagement explain the relationship between leadership and employees’ health? Front. Psychol. 9:2784. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02784

Morsch, J., van Dijk, D., and Kodden, B. (2020). The impact of perceived psychological contract breach, abusive supervision, and silence on employee well-being. J. Appl. Bus. Econom. 22, 37–53.

Mossakowski, K. N., and Zhang, W. (2014). Does social support buffer the stress of discrimination and reduce psychological distress among Asian Americans? Soc. Psychol. Quarter. 77, 273–295. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000045

Nguyen, B., Steel, P., and Ferrari, J. R. (2013). Procrastination’s impact in the workplace and the workplace’s impact on procrastination. Int. J. Select. Assess. 21, 388–399. doi: 10.1111/ijsa.12048

Nguyen, N., and Stinglhamber, F. (2021). Emotional labor and core self-evaluations as mediators between organizational dehumanization and job satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 40, 831–839. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9988-2

Nguyen, N., Dao, Q. A., Nhan, T. L. A., and Stinglhamber, F. (2021). Organizational dehumanization and emotional labor: a cross-cultural comparison between vietnam and the United Kingdom. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 52, 43–60. doi: 10.1177/0022022120972183

Ozaki, K., Motohashi, Y., Kaneko, Y., and Fujita, K. (2012). Association between psychological distress and a sense of contribution to society in the workplace. BMC Public Health 12, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-253

Park, J. H., Carter, M. Z., DeFrank, R. S., and Deng, Q. (2018). Abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence: the effects of gender dissimilarity between supervisors and subordinates. J. Bus. Ethics 153, 775–792. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3384-3

Peng, H. (2013). Why and when do people hide knowledge? J. Knowl. Manag. 17, 398–415. doi: 10.1108/jkm-12-2012-0380

Pereira, V., and Mohiya, M. (2021). Share or hide? Investigating positive and negative employee intentions and organizational support in the context of knowledge sharing and hiding. J. Bus. Res. 129, 368–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.011

Phillips-Miller, D. L., and Morrison, C. R. (1999). Innovative practice: systemic problem solving: retention and the role of a student counseling center. J. College Couns. 2, 180–183. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.1999.tb00154.x

Pignata, S., Boyd, C. M., Winefield, A. H., and Provis, C. (2017). Interventions: employees’ perceptions of what reduces stress. BioMed Res. Int. 2017:589. doi: 10.1155/2017/3919080

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903.

Prem, R., Scheel, T. E., Weigelt, O., Hoffmann, K., and Korunka, C. (2018). Procrastination in daily working life: a diary study on within-person processes that link work characteristics to workplace procrastination. Front. Psychol. 9:1087. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01087

Qasim, M., Irshad, M., Majeed, M., and Rizvi, S. T. H. (2021). Examining impact of islamic work ethic on task performance: mediating effect of psychological capital and a moderating role of ethical leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 21, 1–13.

Rezwan, R. B., and Takahashi, Y. (2021). The psychology behind knowledge hiding in an organization. Admin. Sci. 11:57. doi: 10.3390/admsci11020057

Ridner, S. H. (2004). Psychological distress: concept analysis. J. Advan. Nurs. 45, 536–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x

Robinson, D., Perryman, S., and Hayday, S. (2004). The Drivers of Employee Engagement. Brighton: Institute for Employment Studies.

Robinson, S. L., and Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: a multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 555–572. doi: 10.5465/256693

Sainz, M., and Baldissarri, C. (2021). Abusive leadership versus objectifying job features: factors that influence organizational dehumanization and workers’ self-objectification. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 51, 825–837. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12803

Sainz, M., Delgado, N., and Moriano, J. A. (2021). The link between authentic leadership, organizational dehumanization and stress at work. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 37, 85–92.

Sarwar, A., and Muhammad, L. (2020). Impact of organizational mistreatment on employee performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hospital. Manag. 33, 513–533.

Sarwar, A., Khan, J., Muhammad, L., Mubarak, N., and Jaafar, M. (2021a). Relationship between organizational dehumanization and nurses’ deviant behaviors: a moderated mediation model. J. Nurs. Manag. 29, 1036–1045. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13241

Sarwar, A., Muhammad, L., and Sigala, M. (2021b). Unraveling the complex nexus of punitive supervision and deviant work behaviors: findings and implications from hospitality employees in Pakistan. Int. J. Contemp. Hospital. Manag. 33, 1437–1460. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-08-2020-0808

Serenko, A., and Bontis, N. (2016). Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 20, 1199–1224. doi: 10.1108/jkm-05-2016-0203

Sidorchuk, A., Engström, K., Johnson, C. M., Leeoza, N. K., and Möller, J. (2017). Employment status and psychological distress in a population-based cross-sectional study in Sweden: the impact of migration. BMJ Open 7:e014698. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014698

Škerlavaj, M., Connelly, C. E., Cerne, M., and Dysvik, A. (2018). Tell me if you can: time pressure, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 22, 1489–1509. doi: 10.1108/jkm-05-2017-0179

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., Lockhart, D. E., and Carr, J. C. (2007). Abusive supervision, upward maintenance communication, and subordinates’ psychological distress. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 1169–1180. doi: 10.2307/20159918

Um-e-Rubbab and Naqvi, S. M. M. R. (2020). Employee voice behavior as a critical factor for organizational sustainability in the telecommunications industry. PLoS One 15:e0238451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238451

Väyrynen, T., and Laari-Salmela, S. (2015). Men, mammals, or machines? Dehumanization embedded in organizational practices. J. Bus. Ethics 15, 1–19.

Vayrynen, T., and Laari-Salmela, S. (2018). Men, mammals, or machines? dehumanization embedded in organizational practices. J. Bus. Ethics 147, 95–113. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2947-z

Viertiö, S., Kiviruusu, O., Piirtola, M., Kaprio, J., Korhonen, T., Marttunen, M., et al. (2021). Factors contributing to psychological distress in the working population, with a special reference to gender difference. BMC Public Health 21, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10560-y

Volpato, C., and Andrighetto, L. (2015). “Dehumanization,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. ed. J. D. Wright (Oxford: Elsevier), 31–37. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24035-X

Walsh, M. M., and Arnold, K. A. (2020). The bright and dark sides of employee mindfulness: leadership style and employee well-being. Stress Health 36, 287–298. doi: 10.1002/smi.2926

Wang, C. C., Hsieh, H. H., and Wang, Y. D. (2020). Abusive supervision and employee engagement and satisfaction: the mediating role of employee silence. Pers. Rev. 49, 1845–1858.

Wang, S., and Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: a review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 20, 115–131.

Wang, T., Cao, Z., Zhong, X., and Chen, C. (2021). Self-regulation failure? The influence mechanism of leader reward omission on employee deviant behavior. Front. Psychol. 12:558293. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.558293

Webster, J., Brown, G., Zweig, D., Connelly, C. E., Brodt, S., and Sitkin, S. (2008). Beyond knowledge sharing: Withholding knowledge at work. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 27, 1–37. doi: 10.1016/s0742-7301(08)27001-5

Wei, Z., Li, C. J., Li, F., and Chen, T. (2021). How proactive personality affects psychological strain and job performance: the moderating role of leader–member exchange. Pers. Individ. Differ. 179:110910. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110910

Wu, C. H., and Griffin, M. A. (2012). Longitudinal relationships between core self-evaluations and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 97, 331–342. doi: 10.1037/a0025673

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 74, 235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.003

Yan, R., Basheer, M. F., Irfan, M., and Rana, T. N. (2020). Role of psychological factors in employee well-being and employee performance: an empirical evidence from Pakistan. Rev. Argent. Clín. Psicol. 29:638.

Yao, Z., Zhang, X., Luo, J., and Huang, H. (2020). Offense is the best defense: the impact of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 24, 675–695. doi: 10.1108/jkm-12-2019-0755

Yasir, M., and Rasli, A. (2018). Direct and indirect effects of ethical leadership on workplace deviance in public healthcare sector of Pakistan. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 15, 558–574.

Yen, Y., Shatta, A., and Ahmad, M. (2021). Enhancing organizational performance in the telecommunication industry in Saudi Arabia. Manag. Sci. Lett. 11, 843–848. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2020.10.018

Zhang, Z., and Min, M. (2021). Organizational rewards and knowledge hiding: task attributes as contingencies. Manag. Decis. 59, 2385–2404.

Keywords: knowledge hiding, psychological distress, organizational dehumanization, felt obligation for constructive change, conservation of resources theory

Citation: Rubbab UE, Khattak SA, Shahab H and Akhter N (2022) Impact of Organizational Dehumanization on Employee Knowledge Hiding. Front. Psychol. 13:803905. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.803905

Received: 28 October 2021; Accepted: 05 January 2022;

Published: 21 February 2022.

Edited by:

Krishna Venkitachalam, Estonian Business School, EstoniaReviewed by:

Greta Mazzetti, University of Bologna, ItalySusmita Mukhopadhyay, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India

Copyright © 2022 Rubbab, Khattak, Shahab and Akhter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Um E. Rubbab, cnViYmFiaGF5YXQ1NUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

‡These authors share last authorship

Um E. Rubbab

Um E. Rubbab Sana Aroos Khattak

Sana Aroos Khattak Hina Shahab

Hina Shahab Naveed Akhter3‡

Naveed Akhter3‡