- 1Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

- 2Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

- 3Community Based Psychiatric Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

- 4Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Introduction: Urinary incontinence is a prevalent disorder amongst older women. Identifying the psychosocial experiences of older women in disease management can improve the patient care process. Hence, the present study aimed to determine the psychosocial experiences of older women in the management of urinary incontinence.

Methods: This qualitative study was conducted using conventional content analysis. The study data were collected via unstructured in-depth face-to-face interviews with 22 older women suffering from urinary incontinence selected via purposive sampling. Sampling and data analysis were done simultaneously and were continued until data saturation. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the method proposed by Graneheim and Lundman.

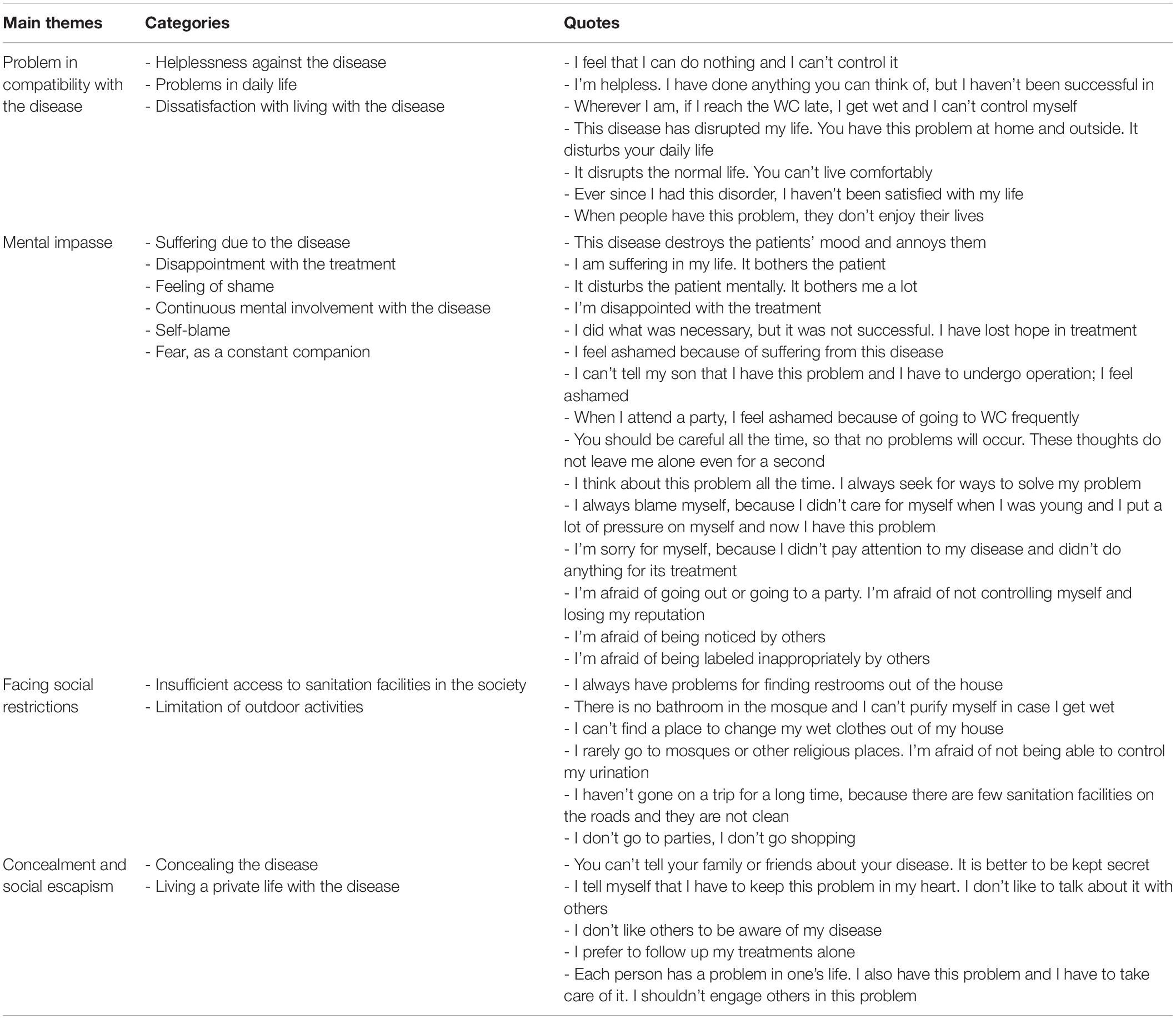

Results: The results indicated that the older people with urinary incontinence had various psychosocial experiences while living with and managing this disease. Accordingly, four main themes were extracted from the data as follows: “problem incompatibility with the disease,” “mental impasse,” “facing social restrictions,” and “concealment and social escapism.”

Conclusion: The findings demonstrated that older people with urinary incontinence experienced significant psychosocial pressures while living with this disorder, which affected their psychosocial well-being. Thus, paying attention to these psychosocial experiences while supporting and taking care of these patients can positively impact their psychosocial health and quality of life.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence has been defined as any involuntary urine leakage (Batmani et al., 2021) and is common in older adults. The prevalence of this disorder has been found to increase with age (Davis et al., 2020; Shaw and Wagg, 2021). Additionally, most epidemiological studies have reported the prevalence of urinary incontinence at 25–45% in females and 5–35% in males (Grant and Currie, 2020; Shaw and Wagg, 2021). In a study conducted in Middle Eastern countries, the prevalence of urinary incontinence was reported as 52%. In the studies conducted in different regions of Asia, the prevalence of urinary incontinence was estimated as 13% in older adults (Kaşıkçı et al., 2015; Khan et al., 2017; Batmani et al., 2021). Another study conducted in Iran indicated that the prevalence of urinary incontinence was 62.2% among women over 60 years of age (Morowatisharifabad et al., 2015).

Along with the relatively high prevalence of this problem among older adults, urinary incontinence causes changes in all aspects of older people’s lives, and it has many physical, psychological, and social effects, affecting their quality of life (Goforth and Langaker, 2016; Saboia et al., 2017; Javadifar and Komeilifar, 2018). Evidence has indicated that older adults with urinary incontinence have lower perceived health than healthy ones (Murukesu et al., 2019). In fact, due to the limitations associated with the disease, as well as the need for continuous care under different conditions, these patients encounter a variety of psychological and social problems (Higa et al., 2008; Grant and Currie, 2020), causing tension and affecting their identity, emotional balance, self-satisfaction, feeling of efficiency, social interaction, and interpersonal relationships (Afrasiabifar et al., 2010; Stickley et al., 2017).

Previous studies have shown that urinary incontinence was associated with depression, stress, and self-esteem. Accordingly, women with urinary incontinence reported significantly higher levels of depression and stress and lower self-esteem levels than those without this problem (Lee et al., 2021). On the other hand, the findings of another study on the psychosocial impacts of urinary incontinence on women’s quality of life showed that the psychosocial effects of urine leakage like anxiety, isolation, low self-esteem, and depression could worsen the symptoms of urinary incontinence. Therefore, it could adversely affect the quality of life of the affected women (Omu et al., 2020).

How the older adults cope with this disease, and attitudes about this disease are very important in the older adults and the society in which the older adults live (Avery et al., 2013) and can affect their psychosocial health as well as their quality of life (Alshammari et al., 2020). Evidence has demonstrated that older women handle these hurdles depending on their social and cultural backgrounds. In other words, each disease is caused, experienced, and managed differently by different people based on the social and cultural backgrounds of the society they live in van den Muijsenbergh and Lagro-Janssen (2006), Andersson et al. (2008), Hayder and Schnepp (2010), Gjerde (2012), Shirazi et al. (2014), Özkan et al. (2015), Heidari et al. (2021), Shakery et al. (2021). Thus, to determine the psychosocial effects of urinary incontinence on older women, their sociocultural backgrounds should be considered (Sinclair and Ramsay, 2011; Laganà et al., 2014; Alshammari et al., 2020). On the other hand, regarding each society’s sociocultural backgrounds, identifying the experiences of older women suffering from urinary incontinence, finding the strategies they use for the management of the disease, and determining the effects of those strategies on various health dimensions, particularly psychosocial health, can help nurses and other healthcare team members identify and evaluate this problem amongst older women and take measures to provide these patients with training and healthcare services. In this way, they will promote their psychosocial health and improve their quality of life (Pintos-Díaz et al., 2019). In this context, qualitative studies should be conducted based on the sociocultural features of the society where the intended older people live (Shirazi et al., 2016).

Considering Iran’s specific cultural, social, and religious backgrounds, high prevalence of urinary incontinence among older women, and lack of qualitative studies in this field, the present study aims to determine the psychosocial experiences of older women regarding the management of urinary incontinence.

Materials and Methods

Aim

The present study aimed to determine the psychosocial experiences of older women in the management of urinary incontinence.

Study Design

This qualitative research was conducted via conventional content analysis. Content analysis refers to the process of perception, interpretation, and conceptualization of the inner meanings of qualitative data (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). In this method, categories are inductively extracted from textual and verbal data (Cho and Lee, 2014).

Participants

This study was conducted on Persian-speaking older women aged >60 years who were clinically diagnosed with one type of urinary incontinence, were suffering from the disease for at least 6 months, had no history of mental disorders, were utterly conscious, and were willing to take part in the research and share their experiences of disease management. The participants were selected via purposeful sampling from the older women referred to comprehensive health centers in Ahvaz from November 2019 until May 2020. In order to achieve maximum variation among the participants, older women with various education levels, marital statuses, and financial statuses were enrolled in the research. In other words, the researcher interviewed older adults with a suitable economic status (P: 2, 13) as well as those with moderate (P: 1, 7) or poor (P: 14, 19) economic statuses. She also interviewed older adults with a desirable literacy level (P: 9, 12) as well as illiterate ones (P: 6, 11). Interviews were also conducted with older adults living alone (P: 5, 10) as well as those living with their families (P: 3, 4) or spouses (P: 8, 17). Older women with urinary incontinence were interviewed until data saturation was achieved. After all, 22 participants were selected and interviewed.

Data Collection

The study data were collected via unstructured in-depth face-to-face interviews in comprehensive health centers affiliated to Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences from November 2019 until May 2020. It should be noted that the time and place of the interviews were arranged with the participants. The interviews were begun with general questions like “what psychosocial problems has urinary incontinence created for you” and “what do you do to overcome these problems” and were continued using probing questions like “can you explain more,” “please give an example,” “how did you feel under those conditions,” and “what did you do when you encountered this problem.” The first interview was treated as preliminary and was used to identify the potential areas of interest or concern. The interviews lasted for 40–60 min and were recorded using a digital recorder (made by Sony). Purposive sampling was continued until data saturation was achieved and the collected information confirmed the previously gathered points. Overall, 24 interviews were conducted with 22 participants (two patients were interviewed twice). While analyzing the interviews, the researchers encountered some issues, which required further probing and follow-up. Therefore, two participants were interviewed twice in order to achieve richer data. After each interview, its content was transcribed verbatim in the shortest time possible.

Data Analysis

The study data were analyzed based on the method proposed by Graneheim and Lundman (2004), which included the following stages: (1) immediate transcription of interviews, (2) reading the whole text for gaining an overall perception, (3) determination of the units of meaning and initial codes, (4) classification of the similar initial codes in more broad categories, and (5) determining the hidden content in the data (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004). Therefore, in the present study, the contents of the interviews were immediately transcribed, typed, and read several times. In this way, the meaning units were extracted from the words, sentences, and paragraphs and were coded. Afterward, a constant comparison was made, and the codes were categorized based on their similarities. Then, the initial codes were merged in order to create more abstract categories and the themes were identified. Categorization and analysis of the data were carried out using the MAXQDA 10 software.

Ethical Considerations

After gaining permission from the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.AJUMS.REC.1398.604, proposal No. NCRCCD-9825) and acquiring the necessary licenses, data collection was started. It should be noted that the participants’ oral and written informed consent was also obtained before data collection. In addition, the interviews were carried out such a way that the participants’ comfort and privacy were respected. Besides, the participants were given nicknames to ascertain the anonymity and confidentiality of their information. The participants were also assured that they could withdraw from the study without any negative impacts on their treatment processes. After all, the interviews were transcribed word by word, and the codes were extracted exactly from the points mentioned by the participants.

Trustworthiness

In order to ensure the trustworthiness of the data, use was made of the criteria proposed by Guba and Lincoln (1994), i.e., credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability. In order to determine the credibility of the collected data, use was made of prolonged engagement (10 months). In addition, the codes, categories, and themes were continuously investigated and reviewed by the research team. The initial codes were also returned to the interviewees to be confirmed. In order to determine dependability, the research team was involved in the study process, and the results were presented to several external observers to explore the process of data analysis. In order to achieve confirmability, all research processes, particularly data collection and analysis, as well as the formation of the main themes, were approved by the external observers. Finally, maximum diversity was observed in the selection of the participants to enhance transferability.

Results

This study was conducted on 22 older women with a mean age of 66.54 ± 5.76 years who suffered from urinary incontinence. Among the participants, 72% were married, and 28% were widowed. In addition, 9.18% of the participants had an academic education, 59.01% had diplomas and below diploma degrees, and 31.81% were illiterate. The participants had been suffering from urinary incontinence for 2–20 years.

The results revealed that the participants had various psychosocial experiences while living with and managing this disease, which affected their health and quality of life. Data analysis showed four main themes and 13 categories. The main themes included “problem incompatibility with the disease,” “mental impasse,” “facing social restrictions,” and “concealment and social escapism.” The main themes, categories, and the participants’ direct quotes have been presented in Table 1.

Problem Incompatibility With the Disease

The life experiences of older adults women with urinary incontinence showed their problems incompatibility with the disease. Despite using various strategies, they were not able to control their urination under sensitive circumstances. Therefore, they frequently faced failures in combating the disease and felt helpless in this regard. On the other hand, their inability to control their disease disrupted their daily lives, created numerous problems for them, and disturbed their tranquility, eventually leading to a feeling of dissatisfaction with life.

Helplessness Against the Disease

Despite using various strategies such as restricting the consumption of fluids, eating specific types of food, consuming medications, and reducing the activities that increased the intra-abdominal pressure, the participants were not able to control their disease under sensitive conditions including the times they were at parties, out of the house, or with others. This caused them to feel helpless in disease management. They also stated frequently that they were defeated by the disease.

“When I suddenly sneeze or laugh at a party, the urine leaks unintentionally, and I cannot control it” (P. 9).

“I feel that I have been defeated. I have had enough. I feel helpless” (P. 1).

Problems in Daily Life

This disease disrupted the patients’ everyday life processes, leading to an imbalance in their lives. In other words, the participants’ activities of daily living were affected by the disease.

“This disease has affected my life. It has disturbed my tranquility” (P. 8).

“Ever since I had this problem, I have faced problems in doing my religious affairs because I can’t keep myself clean” (P. 4).

“From people’s perspective, this is not an acceptable disease. All people love cleanliness. If individuals are not clean or can’t keep themselves clean, their lives will be disrupted” (P. 10).

Dissatisfaction With Living With the Disease

The limitations and problems associated with the disease resulted in the feeling of dissatisfaction with life among the participants. In other words, the participants frequently mentioned their dissatisfaction with living with this disease.

“It has created many problems in my life. Living with this disease is like a nightmare. I do not enjoy my life. I am not satisfied with living with this disease” (P. 4).

Mental Impasse

While living with urinary incontinence, the participants suffered a lot. On the other hand, the ineffectiveness of their measures for managing the disease resulted in their disappointment with the treatment. Moreover, they felt ashamed and blamed themselves for suffering from the disease. They were also tired of thinking about the disease and controlling it all the time. Furthermore, they constantly feared while living with this disease, fear of being judged and rejected. These multifaceted mental pressures put them in a mental impasse.

Suffering Due to the Disease

In addition to the disease, the older participants suffered from getting wet frequently, frequent purification, and foul urine smell.

“It is hard to tolerate the disease. It bothers the patient a lot” (P. 12).

“I am annoyed since I get wet frequently, and I need to purify myself” (P. 5).

Disappointment With the Treatment

Frequent failures in the treatment and control of the disease and facing the peers’ negative experiences created a feeling of discouragement and disappointment among the older women.

“I have done everything to treat the disease, but I was not successful. I have become disappointed” (P. 15).

Feeling of Shame

Since the participants considered urinary incontinence a taboo, they felt ashamed of suffering from this disease. The experiences of unintentional urine leakage further stimulated this feeling at inappropriate times and places and in the presence of other individuals.

“When you get wet in front of your family, friends, and even children, you feel ashamed” (P. 3).

Self-Blame

The participants frequently blamed themselves for suffering from the disease. In this respect, they believed that the disease resulted from their lack of self-care. They also stated that the lack of timely follow-up of the disease caused the intensification of the condition.

“When I get wet, I just blame myself because I did not care for the problem to solve it sooner” (P. 18).

Continuous Mental Involvement With the Disease

The participants emphasized that they thought about their disease all the time. In other words, they lived with these mental ruminations. They believed that they had to be careful about their problem to manage it to the extent possible.

“I think about my disease all the time. It does not get out of my mind even for a second. I have to be careful to avoid problems” (P. 14).

Fear, as a Constant Companion

The participants lived with a constant fear resulting from their inability to control their urinations and the intensification of the disease over time.

“I am afraid of the intensification of my conditions with aging” (P. 11).

The participants were also frightened to unveil their disease because they feared facing their acquaintances’ inappropriate behaviors. They were also afraid of others’ judgments and attitudes toward the disease. They thought that their family and friends would not be willing to have relationships with them due to their disease.

“I am afraid of changes in others’ behaviors, not being accepted by others. They may not be willing to have relationships with me. I am afraid of being rejected” (P. 16).

Facing Social Restrictions

The older women with urinary incontinence faced various social restrictions, including lack of access to sanitation facilities, which reduced their social activities.

Insufficient Access to Sanitation Facilities in the Society

The majority of the participants complained about the lack of sanitation facilities in the society. They maintained that they did not have access to public restrooms in some places. The inability to use Iranian toilets was yet another problem mentioned by the participants. Moreover, they did not have access to bathrooms, particularly in religious places, to purify themselves if necessary. They could not also find a place to change their wet clothes while they were out.

“There are no public restrooms on many streets, and if there are, they are very dirty” (P. 5).

“When I get wet out of my house, I can’t find a safe place to clean myself and change my clothes” (P. 8).

Limitation of Outdoor Activities

Considering the participants’ inability to control their urination and their insufficient access to sanitation facilities in society, they were obligated to limit their outdoor activities. Therefore, they avoided leaving the house or going to places without sanitation facilities to the extent possible. In other words, they only referred to places with public restrooms and had limited social activities.

“I do not go anywhere to the extent possible. I leave the house only for work because I am afraid of not finding a public restroom” (P. 19).

“I have limited my recreational activities with my family and friends” (P. 10).

Concealment and Social Escapism

The study participants tended to conceal their disease. They emphasized that this condition was a personal problem, which caused them to escape from society to hide their disease.

Concealing the Disease

Although the disease had negative impacts on the participants’ social activities, mental health, and well-being, they were not willing to talk about their problem with their families, friends, and even the healthcare team due to the nature of the disease and in order to prevent social stigma. To hide their disease, some participants deprived themselves from forging social relationships with others and preferred to escape from society rather than unveiling their disease.

“I have hidden my problem from my family and friends” (P. 6).

“I do not like to talk about it with others. I do not like others to be aware of my problem. I hide it from everyone” (P. 17).

Living a Private Life With the Disease

The participants considered their disease a personal issue and avoided the engagement of others, even their family members, in their problem. They tended to manage and treat their disease on their own. They believed that talking to their family and friends about the disease did not help them solve the problem and resulted in sadness and sensitivity.

“I consider this disease a personal problem. I do not like to involve my family in this issue” (P. 18).

“I tell myself that I have to shoulder the burden of this problem” (P. 20).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine older women’s experiences regarding the management of urinary incontinence. The findings demonstrated that the participants experienced numerous mental pressures and social restrictions, which were effective in their psychosocial health. Totally, four main themes were extracted from the data as follows: “problem incompatibility with the disease,” “mental impasse,” “facing social restrictions,” and “concealment and social escapism.”

Urinary incontinence is accompanied by psychosocial consequences in older adult women, which are sometimes even more harmful than physical consequences. This disease exerts vast effects on daily living activities, social interactions, perception of health status, and quality of life, eventually resulting in limitations whose degree depends on society’s cultural background. These limitations, in turn, affect women’s mental and social health. Previous studies also indicated that the incidence of psychosocial complications was associated with urinary incontinence. Accordingly, older people with urinary incontinence had a weaker psychosocial health status (Chiu et al., 2020; Omu et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021).

Similarities seem to exist in the psychosocial meanings of urinary incontinence amongst older women living in different cultures, ethnic groups, and social conditions. However, this disease can be accompanied by more problems in societies with specific religious backgrounds. Evidence has indicated differences in disease management experiences of the older women living in such communities compared to those in other societies. For instance, in Islamic communities, urinary incontinence can have more negative psychosocial effects on older adults people due to the cultural-religious atmosphere ruling the society (Karlowicz, 2010; Avery and Stocks, 2016; Jaberi et al., 2019; Batmani et al., 2021). This disease has also been associated with being reserved, isolated, and low self-esteem among Muslim women (Jokhio et al., 2013).

In the present study, facing unexpected and uncontrollable disease conditions resulted in the participants’ helplessness and dissatisfaction with life due to disrupting their natural life processes. This was to some extent affected by the society’s sociocultural background and represented helplessness incompatibility with the disease, which led to numerous psychosocial consequences for the older adults. In the same line, Hägglund and Ahlström (2007) disclosed that the inability to control urination resulted in the feeling of incompetence in disease management and reduced self-esteem amongst older women with urinary incontinence. This eventually led to psychosocial problems like isolationism, anxiety, and depression (Hägglund and Ahlström, 2007). Consistently, Berges et al. (2014) and Kinsey et al. (2016) reported that urinary incontinence disrupted the patients’ activities of daily living, disturbed their normal life processes, and increased tensions in their lives. Other studies have also revealed dissatisfaction with life among older women with urinary incontinence. Accordingly, this disease negatively affected the patients’ quality of life (Sinclair and Ramsay, 2011; Cerruto et al., 2013; Saboia et al., 2017).

This disease causes psychological complications in older adults (Avery et al., 2013). Based on the current study findings, such complications as shame, fear, self-blame, disappointment, and constantly thinking about the disease put the older adults in a mental impasse, negatively affecting their mental well-being. The majority of studies in this field have also shown the feeling of shame among older patients with urinary incontinence (Hägglund and Wadensten, 2007; Nicolson et al., 2008). Moreover, patients considered this disease as a kind of stigma (Elstad et al., 2010). This attitude is frequently detected amongst Asian women, specifically South Asian ones, and affects discussions about the disease and reception of the related care services. On the other hand, concealing the inconveniences associated with the disease due to being shameful exerts a negative impact on patients’ mental health (Higa et al., 2008; Chiu et al., 2020). Furthermore, since urine is considered dirty in the Islamic culture and urinary incontinence is regarded as uncleanliness, older adults’ women with this disease have a constant fear from the way others may treat them. Previous studies also indicated that patients with urinary incontinence were constantly afraid of getting wet in front of others (Lim, 2016; Spencer et al., 2017), others’ behaviors and judgments about the problem (Avery et al., 2013), and being rejected by others (Andersson et al., 2008). In the same vein, Doshani et al. (2007) stated that these patients were afraid of losing their relationships with others due to their disease, which significantly impacted their mental health.

Self-blame is also among the psychological disorders detected in older people suffering from urinary incontinence (Senra and Pereira, 2015; Toye and Barker, 2020). Iranian women frequently sacrifice themselves, pay less attention to their health status, and prioritize other issues in their lives. This worsens their health problems, eventually leading to regret and self-blame. In the present research, the participants frequently blamed themselves for not having paid attention to the primary symptoms of the disease, not having taken timely measures for treating the disease and not having cared for themselves in this respect. Various studies have also revealed self-blame among patients with urinary incontinence, which was effective in their mental health (Mason et al., 1999; Teunissen et al., 2006; Avery et al., 2013; Senra and Pereira, 2015; Lee et al., 2021).

Other psychological problems mentioned in the current study included discouragement and disappointment of treatment, which affected their treatment process. Which agreed with the results of the research carried out by Nicolson et al. (2008). They found hopelessness together with anxiety and depression amongst patients with urinary incontinence. In their study, older women were also disappointed with urinary incontinence treatment and refused to seek treatment (Nicolson et al., 2008). In the current investigation, the participants were tired of thinking about controlling their disease under various circumstances. They could not stop thinking about the disease. Similarly, Hemachandra et al. (2009) reported that patients with urinary incontinence were tired of constantly thinking about the disease and controlling the conditions to avoid urine leakage, which harmed their mental health. Thus, the incidence of psychological disorders was considered an obstacle against mental well-being, accompanied by a mental burden among older women suffering from urinary incontinence (Sinclair and Ramsay, 2011; Avery et al., 2013).

The current study participants experienced significant social restrictions that affected their social functions and fulfillment of their social roles, eventually leading to social isolation. Therefore, it can be said that older people with urinary incontinence do not have a proper level of social health. Because social health encompasses individuals’ social skills, social function, and ability to consider themselves as a part of society. Therefore, the social health of older women with urinary incontinence is impaired due to their inability to interact effectively with others and society and their inability to establish satisfactory social relationships and play their social roles (Babanejad et al., 2013; Saeid et al., 2019).

Older people need social support and welfare facilities to participate in society and participate in social activities; therefore, lack of appropriate social support for older people with urinary incontinence and paucity of sanitation facilities in the society restrict the presence of these individuals in the society, disrupt the fulfillment of their social roles, and lead to social isolation, thereby affecting their social health (Avery et al., 2013). Other studies also demonstrated that insufficient social support for older people and lack of welfare amenities in society were among the main problems that reduced their social participation (Darvishpoor Kakhki et al., 2010; Saeid et al., 2019). On the other hand, when urinary incontinence is considered uncleanliness in a society with a specific cultural and religious background, purification facilities have to be sufficiently provided in the society so that older adults’ individuals with this disease can use them if necessary. Hence, in this study, the lack of these facilities in the society has been mentioned as a limitation for the presence of older adults in the community and for their performance of social activities. In this respect, Hosseini et al. (2021) stated in their study that lack of social support for older people and lack of the required facilities, decreased their presence in society and affected their health and well-being.

On the other hand, older adults’ involvement in social networks such as family, friends, and neighbor networks is considered a source of support, helping them achieve appropriate mental and social health and supplying their other health dimensions (Javanmardifard et al., 2020; Hosseini et al., 2021). However, although the older women in our study suffered from urinary incontinence and needed support in many dimensions, they were doubtful about talking to others, even the healthcare team and family, and were willing to conceal their disease and escape from society and social networks. They regarded the disease as a secret in their lives and insisted on hiding it from others and managing it on their own. Other studies also indicated that older people were doubtful about unveiling their disease, which implied their deprivation from receiving help to facilitate the disease management (Hemachandra et al., 2009; Elstad et al., 2010; Jokar et al., 2020). Thus, if older patients deprive themselves of taking part in these social networks due to their unwillingness to unveil their disease, their mental and social health will be affected (Avery et al., 2013).

Since the emphasis of older women in our study on escaping from society, hiding their disease, and depriving themselves from the existing support sources like family, friends, and healthcare team resulted in their escape from society, which led to social isolation and affected their social health. In this respect, Thomas and Liu (2017) referred to the importance of older people’s close relationships with their families, which helped them receive beneficial support and tolerate and manage their health problems. However, they stated that the participation of older adults in social networks decreased with age. Therefore, favorable family relationships play a more important role in their well-being and help them cope better with various stresses of this period and have healthier behaviors. This can, in turn, increase their self-esteem and exert a positive effect on their psychosocial health (Thomas and Liu, 2017).

Therefore, it is important to provide the facilities needed by these older adults in the community and also to provide conditions for the older adults with urinary incontinence to share their problems more easily with others, especially the family and health care team, to use the available support resources for better management of their disease; otherwise, it makes older women more exposed to the psychosocial effects of the disease.

Conclusion

Even though urinary incontinence is not a life-threatening condition, it can considerably impact the mental and social health of older women suffering from the disease. These individuals face numerous mental and social challenges for their disease management, which affect their psychosocial well-being and quality of life. Paying attention to the psychosocial health of older adults with urinary incontinence based on the society’s cultural and religious background and providing them with psychosocial support on the part of the healthcare team, families, and friends can help them desirably manage their disease.

Implications

Considering the growth of aging and the sociocultural background of the societies where older people live, it is necessary to pay attention to psychosocial health amongst older people suffering from urinary incontinence, examine these patients regarding the psychosocial complications of the disease, and find the origins of their problems. Besides, healthcare team members have to make genuine attempts to solve these problems. For instance, they are suggested to encourage such older patients to share their experiences with their peers, which can help break the associated taboos and promote treatment-seeking behaviors among these patients. Furthermore, the facilities needed by older adults’ individuals with urinary incontinence are recommended to be provided in society to be able to actively participate in the community. This will eventually affect their physical, mental, and social health and their quality of life.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.AJUMS.REC.1398.604, Proposal No. NCRCCD-9825). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SJ, MG, FS, KZ, and FG were involved in the study conception and design, contributed to the data collection and analysis, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, provided administrative and technical support, and supervised the work. SJ, MG, FS, and KZ drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to preparing the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (grant no. NCRCCD-9825).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This article was a part of a Ph.D. dissertation written by SJ, which was financially supported by the Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (NCRCCD-9825). Hereby, we would like to extend their sincere thanks to the study’s sponsor and all the participants. We would also like to appreciate A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Consultation Center (RCC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript.

References

Afrasiabifar, A., Hassani, P., Fallahi Khoshknab, M., and Yaghamaei, F. (2010). Models of adjustment to illness. J. Nurs. Midwifery 19, 42–47.

Alshammari, S., Alyahya, M. A., Allhidan, R. S., Assiry, G. A., AlMuzini, H. R., and AlSalman, M. A. (2020). Effect of urinary incontinence on the quality of life of older adults in riyadh: medical and sociocultural perspectives. Cureus 12:e11599. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11599

Andersson, G., Johansson, J.-E., Nilsson, K., and Sahlberg-Blom, E. (2008). Accepting and adjusting: older women’s experiences of living with urinary incontinence. Urol. Nurs. 28, 115–121.

Avery, J., and Stocks, N. (2016). Urinary incontinence, depression and psychological factors-a review of population studies. Eur. Med. J. Urol. 1, 58–67.

Avery, J. C., Braunack-Mayer, A. J., Stocks, N. P., Taylor, A., and Duggan, P. (2013). Psychological perspectives in urinary incontinence: a metasynthesis. OA Womens Health 1:9.

Babanejad, M., Shokouhi, S., Delpisheh, A., and Ali Ahmadi, N. (2013). Socioeconomic status of aged people in Ilam province. Res. Med. 37, 125–133.

Batmani, S., Jalali, R., Mohammadi, M., and Bokaee, S. (2021). Prevalence and factors related to urinary incontinence in older adults women worldwide: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Geriatr. 21:212. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02135-8

Berges, R., Höfner, K., Gedamke, M., and Oelke, M. (2014). Impact of desmopressin on nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria in men with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH). World J. Urol. 32, 1163–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1381-7

Cerruto, M. A., D’Elia, C., Aloisi, A., Fabrello, M., and Artibani, W. (2013). Prevalence, incidence and obstetric factors’ impact on female urinary incontinence in Europe: a systematic review. Urol. Int. 90, 1–9. doi: 10.1159/000339929

Chiu, M. Y. L., Wong, H. T., and Yang, X. (2020). Distress due to urinary problems and psychosocial correlates among retired men in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:2533. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072533

Cho, J. Y., and Lee, E.-H. (2014). Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: similarities and differences. Qual. Rep. 19, 1–20.

Darvishpoor Kakhki, A., Abed Saeedi, Z., Delavar, A., and Saeed-O-Zakerin, M. (2010). Autonomy in the elderly: a phenomenological study. Hakim Res. J. 12, 1–10.

Davis, N. J., Wyman, J. F., Gubitosa, S., and Pretty, L. (2020). Urinary incontinence in older adults. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 120, 57–62.

Doshani, A., Pitchforth, E., Mayne, C. J., and Tincello, D. G. (2007). Culturally sensitive continence care: a qualitative study among South Asian Indian women in Leicester. Fam. Pract. 24, 585–593. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm058

Elstad, E. A., Taubenberger, S. P., Botelho, E. M., and Tennstedt, S. L. (2010). Beyond incontinence: the stigma of other urinary symptoms. J. Adv. Nurs. 66, 2460–2470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05422.x

Gjerde, J. L. (2012). Female Urinary Incontinence: Perceptions and Practice. A Qualitative Study From Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Bergen: The University of Bergen.

Graneheim, U. H., and Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 24, 105–112.

Grant, A., and Currie, S. (2020). Qualitative exploration of the acceptability of a postnatal pelvic floor muscle training intervention to prevent urinary incontinence. BMC Womens Health 20:9. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0878-z

Guba, E. G., and Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handb. Qual. Res. 2:105.

Hägglund, D., and Ahlström, G. (2007). The meaning of women’s experience of living with long-term urinary incontinence is powerlessness. J. Clin. Nurs. 16, 1946–1954. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01787.x

Hägglund, D., and Wadensten, B. (2007). Fear of humiliation inhibits women’s care-seeking behaviour for long-term urinary incontinence. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 21, 305–312.

Hayder, D., and Schnepp, W. (2010). Experiencing and managing urinary incontinence: a qualitative study. West. J. Nurs. Res. 32, 480–496.

Heidari, S., Shirazi, F., and Badelbuu Ghanipour, S. (2021). Behavioural habits and underlying diseases associated with urolithiasis: a case–control study. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 1–7. doi: 10.1111/ijun.12305

Hemachandra, N. N., Rajapaksa, L. C., and Manderson, L. (2009). A “usual occurrence:”. Stress incontinence among reproductive aged women in Sri Lanka. Soc. Sci. Med. 69, 1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.019

Higa, R., Lopes, M. H. B. D. M., and Turato, E. R. (2008). Psychocultural meanings of urinary incontinence in women: a review. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 16, 779–786. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000400020

Hosseini, M., Dakhteharuni, M., Yaghmaei, F., and Alavi Majd, H. (2021). Investigating the correlation between social support and health of the elderly in selected areas of Tehran. Adv. Nurs. Midwifery 21, 25–30.

Jaberi, A., Momennasab, M., Cheraghi, M., Yektatalab, S., and Ebadi, A. (2019). Spiritual health as experienced by muslim adults in Iran: a qualitative content analysis. Shiraz E Med. J. 20:e88715.

Javadifar, N., and Komeilifar, R. (2018). Urinary incontinence and its predisposing factors in reproductive age women. Sci. J. Ilam Univ. Med. Sci. 25, 45–53.

Javanmardifard, S., Heidari, S., Sanjari, M., Yazdanmehr, M., and Shirazi, F. (2020). The relationship between spiritual well-being and hope, and adherence to treatment regimen in patients with diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 19, 941–950. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00586-1

Jokar, F., Asadollahi, A. R., Kaveh, M. H., Ghahramani, L., and Nazari, M. (2020). Relationship of perceived social support with the activities of daily living in older adults living in rural communities in Iran. Iran. J. Ageing 15, 350–365.

Jokhio, A., Rizvi, R., Rizvi, J., and MacArthur, C. (2013). Urinary incontinence in women in rural Pakistan: prevalence, severity, associated factors and impact on life. BJOG 120, 180–186. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12074

Karlowicz, K. A. (2010). The effect of culture on urinary incontinence: do we really understand? Urol. Nurs. 30, 318–326.

Kaşıkçı, M., Kılıç, D., Avşar, G., and Şirin, M. (2015). Prevalence of urinary incontinence in older Turkish women, risk factors, and effect on activities of daily living. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 61, 217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.008

Khan, S., Ansari, M. A., Vasenwala, S. M., and Mohsin, Z. (2017). The influence of menopause on urinary incontinence in the women of the community: a cross-sectional study from North India. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 6, 911–918. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20170555

Kinsey, D., Pretorius, S., Glover, L., and Alexander, T. (2016). The psychological impact of overactive bladder: a systematic review. J. Health Psychol. 21, 69–81. doi: 10.1177/1359105314522084

Laganà, L., Bloom, D. W., and Ainsworth, A. (2014). Urinary incontinence: its assessment and relationship to depression among community-dwelling multiethnic older women. Sci. World J. 2014:708564. doi: 10.1155/2014/708564

Lee, H.-Y., Rhee, Y., and Choi, K. S. (2021). Urinary incontinence and the association with depression, stress, and self-esteem in older Korean women. Sci. Rep. 11:9054. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88740-4

Lim, D. S. (2016). Management of urinary incontinence in residential care. Aust. Fam. Phys. 45, 498–502.

Mason, L., Glenn, S., Walton, I., and Appleton, C. (1999). The experience of stress incontinence after childbirth. Birth 26, 164–171.

Morowatisharifabad, M. A., Rezaeipandari, H., Mazyaki, A., and Bandak, Z. (2015). Prevalence of urinary incontinence among elderly women in Yazd. Iran: a population-based study. Elder. Health J. 1, 27–31.

Murukesu, R. R., Singh, D. K., and Shahar, S. (2019). Urinary incontinence among urban and rural community dwelling older women: prevalence, risk factors and quality of life. BMC Public Health 19:529. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6870-6

Nicolson, P., Kopp, Z., Chapple, C., and Kelleher, C. (2008). It’s just the worry about not being able to control it! A qualitative study of living with overactive bladder. Br. J. Health Psychol. 13, 343–359. doi: 10.1348/135910707X187786

Omu, F. E., Takadom, S., Vellolikala, C., Al-Harbi, F., Ismail, S., and Jeevakumari, G. (2020). The psycho-social impact of urinary incontinence on the quality of life among Kuwaiti women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Open J. Nurs. 10:716. doi: 10.4236/ojn.2020.107051

Özkan, S., Başgöl, Ş, and Beji, N. (2015). The meaning of urinary incontinence in female geriatric population who experience urinary incontinence: a qualitative study. Ann. Nurs. Pract. 2:1028.

Pintos-Díaz, M. Z., Alonso-Blanco, C., Parás-Bravo, P., Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C., Paz-Zulueta, M., Fradejas-Sastre, V., et al. (2019). Living with urinary incontinence: potential risks of women’s health? A qualitative study on the perspectives of female patients seeking care for the first time in a specialized center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:3781. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193781

Saboia, D. M., Firmiano, M. L. V., Bezerra, K. C., Vasconcelos, J. A., Oriá, M. O. B., and Vasconcelos, C. T. M. (2017). Impact of urinary incontinence types on women’s quality of life. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 51:e03266. doi: 10.1590/S1980-220X2016032603266

Saeid, M., Makarem, A., Khanjani, S., and Bakhtyari, V. (2019). Comparison of social health and quality of life between the elderlies resident at nursing homes with non-resident counterparts in Tehran City, Iran. Salmand Iran. J. Ageing 14, 178–187.

Senra, C., and Pereira, M. G. (2015). Quality of life in women with urinary incontinence. Rev. Assoc. Méd. Bras. 61, 178–183.

Shakery, M., Mehrabi, M., and Khademian, Z. (2021). The effect of a smartphone application on women’s performance and health beliefs about breast self-examination: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21:248. doi: 10.1186/s12911-021-01609-4

Shaw, C., and Wagg, A. (2021). Urinary and faecal incontinence in older adults. Medicine 49, 44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2020.10.012

Shirazi, F., Heidari, S., Sanjari, M., Khachian, A., and Shahpourian, F. (2014). The role of dietary habits in urinary stone disease. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 8, 137–143.

Shirazi, M., Manoochehri, H., Zagheri Tafreshi, M., Zayeri, F., and Alipour, V. (2016). Chronic pain management in older people: a qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. Midwifery 4, 13–28.

Sinclair, A. J., and Ramsay, I. N. (2011). The psychosocial impact of urinary incontinence in women. Obstet. Gynaecol. 13, 143–148. doi: 10.1576/toag.13.3.143.27665

Spencer, M., McManus, K., and Sabourin, J. (2017). Incontinence in older adults: the role of the geriatric multidisciplinary team. Br. Columbia Med. J. 59, 99–105.

Stickley, A., Santini, Z. I., and Koyanagi, A. (2017). Urinary incontinence, mental health and loneliness among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland. BMC Urol. 17:29. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0214-6

Teunissen, D., Van Den Bosch, W., Van Weel, C., and Lagro-Janssen, T. (2006). “It can always happen”: the impact of urinary incontinence on elderly men and women. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 24, 166–173. doi: 10.1080/02813430600739371

Toye, F., and Barker, K. L. (2020). A meta-ethnography to understand the experience of living with urinary incontinence:‘is it just part and parcel of life?’. BMC Urol. 20:1. doi: 10.1186/s12894-019-0555-4

Keywords: urinary incontinence, women, psychosocial, qualitative research, older

Citation: Javanmardifard S, Gheibizadeh M, Shirazi F, Zarea K and Ghodsbin F (2022) Psychosocial Experiences of Older Women in the Management of Urinary Incontinence: A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychol. 13:785446. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.785446

Received: 29 September 2021; Accepted: 14 February 2022;

Published: 08 March 2022.

Edited by:

Gary Christopher, University of the West of England, Bristol, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sonia Lorente, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa, SpainHeather Honoré Goltz, University of Houston–Downtown, United States

Copyright © 2022 Javanmardifard, Gheibizadeh, Shirazi, Zarea and Ghodsbin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mahin Gheibizadeh, Z2hlaWJpemFkZWgtbUBhanVtcy5hYy5pcg==

†ORCID: Sorur Javanmardifard, orcid.org/0000-0001-9891-852X; Mahin Gheibizadeh, orcid.org/0000-0002-3673-8715; Fatemeh Shirazi, orcid.org/0000-0002-4127-0838; Kourosh Zarea, orcid.org/0000-0001-5124-6025; Fariba Ghodsbin, orcid.org/0000-0001-5713-5748

Sorur Javanmardifard

Sorur Javanmardifard Mahin Gheibizadeh

Mahin Gheibizadeh Fatemeh Shirazi

Fatemeh Shirazi Kourosh Zarea

Kourosh Zarea Fariba Ghodsbin

Fariba Ghodsbin