- 1Department of Applied Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

For scholars, practitioners, and legislators concerned about sexual minority adolescents, one of the main goals is to create more positive and inclusive learning environments for this minority group. Numerous factors, such as repeated patterns of homophobic bullying by classmates and others in school, have been a significant barrier to achieving this goal. In addition, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) adolescents encounter substantial inequality across a broad spectrum of wellbeing and education consequences. Compared with their heterosexual counterparts, LGBTQ adolescents experience more anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, antisocial behavior, poorer academic performance, less school attachment and protection, and a weaker desire to finish their studies. Such discrepancies based on gender and sexuality were linked to more maltreatment encountered by LGBTQ adolescents. It is crucial to recognize the backgrounds and expectations of LGBTQ adolescents to offer them the best resources. To overcome the inequality and obstacles faced by these LGBTQ adolescents, it is essential to examine tools and techniques that can be utilized. This study examined the literature that explains why society fails to provide enough support to LGBTQ students. Specifically, mechanisms explaining how LGBTQ adolescents interact with others in the learning environment and how such discrepancies arise will be examined. Following that, violence and prejudice, which are fundamental causes of psychological problems among LGBTQ adolescents, will be explored. This review paper thus provides supportive strategies for schools to develop more inclusive learning environments for LGBTQ adolescents.

Introduction

Globally, schools play an essential role in enabling students to acquire college credentials and knowledge, become familiar with the culture, learn about interpersonal relationships, ideals, and standards, and develop survival skills and expertise abilities (Skovdal and Campbell, 2015). When individuals attend schools and colleges and receive a comprehensive education, their chances in life are improved. The community requires their expertise, and they are well equipped to serve it. Given the many roles and advantages of education, school environments need to be protective, stable, inclusive, and pleasant to all students to maximize learning opportunities for everyone to guarantee that school goals are met. Regrettably, colleges and universities worldwide may not be a safe environment for LGBTQ students, who face intimidation, maltreatment, rejection, and other types of discrimination and exploitation (Poynter and Washington, 2005; Fields and Wotipka, 2020; Kurian, 2020). These experiences lead to agony, distress, and anxiety and could have a detrimental effect on LGBTQ students’ physical, psychological and educational wellbeing (Mateo and Williams, 2020; Mallory et al., 2021).

The Correlations Between Discrimination and Mental Health

There are different forms of discrimination, including verbal abuse, physical aggression, burglaries, accommodation discrimination, and sexual assault (Flores A. R. et al., 2020). Adolescents who identify as LGB experience more severe peer harassment and maltreatment than their straight counterparts (Kolbe, 2020). In the United States, 34% of LGB adolescents experienced bullying at school in the surveyed year, compared to 19% of straight adolescents (Johns et al., 2020). It has been reported that maltreatment of children based on their sexuality has occurred at an early age, as young as eight and nine years old (Evans-Polce et al., 2020).

Proximal minority stressors may negatively affect the lives of LGBTQ individuals. They include internalized homonegativity, societal exclusion expectancies, and the concealment of one’s sexual identity (Delozier et al., 2020). Individuals who have a greater degree of internalized homonegativity express more unfavorable sentiments about themselves due to their sexual orientation (Ocasio et al., 2020). Additionally, LGBTQ people may suffer stress or lack self-confidence due to their sexuality (Minturn et al., 2021). Since sexuality can be concealed from others and that marginalization of LGBTQ people may not be immediately apparent throughout most human relationships (Kachanoff et al., 2020), LGBTQ people need to determine whether, when, how, and to whom they disclose their sexuality (Alonzo and Buttitta, 2019; Lo, 2020). Multiple declarations of their socially marginalized identities might be required, increasing their stress (Daniele et al., 2020). Substantial evidence suggests that bisexual youngsters are at an even greater risk of developing psychological problems than gay/lesbian adolescents (Savin-Williams, 2020), given experiences of stressors associated with “double discrimination” (i.e., exclusion from both the heterosexual and LG populations) and dismissal of one’s self-image as “just a phase” (Ramasamy, 2020).

It should also be noted that LGBTQ students who identify as members of other oppressed groups (for example, racial and cultural minorities, non-Christians, and members of the lower class) may face heightened instances of discrimination in educational institutions. According to The Trevor Project’s 2019 national study on LGBTQ psychological wellness, 71% of LGBTQ youngsters encountered prejudice due to gender and/or sexuality. Additionally, two-thirds of the LGBTQ adolescent interviewees reported that they had been persuaded to alter their sexuality. A survey found that 78% of transgender and non-binary adolescents faced prejudice due to their gender and sexuality, while 70% of LGBTQ adolescents experienced discrimination against their gender expressions. Another study (Platero and López-Sáez, 2020) found that 58% of transgender and non-binary adolescents experienced being discouraged from using the restroom that matched their gender preference.

In addition, study findings indicate that LGBTQ individuals may have serious psychological issues due to their sexuality. A study showed that 39% of LGBTQ interviewees reported actively contemplating suicide in the surveyed year, a majority of them aged between 13 and 17 (Higbee et al., 2020). An astounding 71% of LGBTQ adolescents reported experiencing despair or depression for no fewer than 14 days during the surveyed year (Higbee et al., 2020). While significant progress has been achieved in terms of LGBTQ inclusion over the previous decade, this poll demonstrates that the LGBTQ community, especially younger members, continue to face challenges directed at their sexual identities (Standley, 2020).

Current Quantitative Study

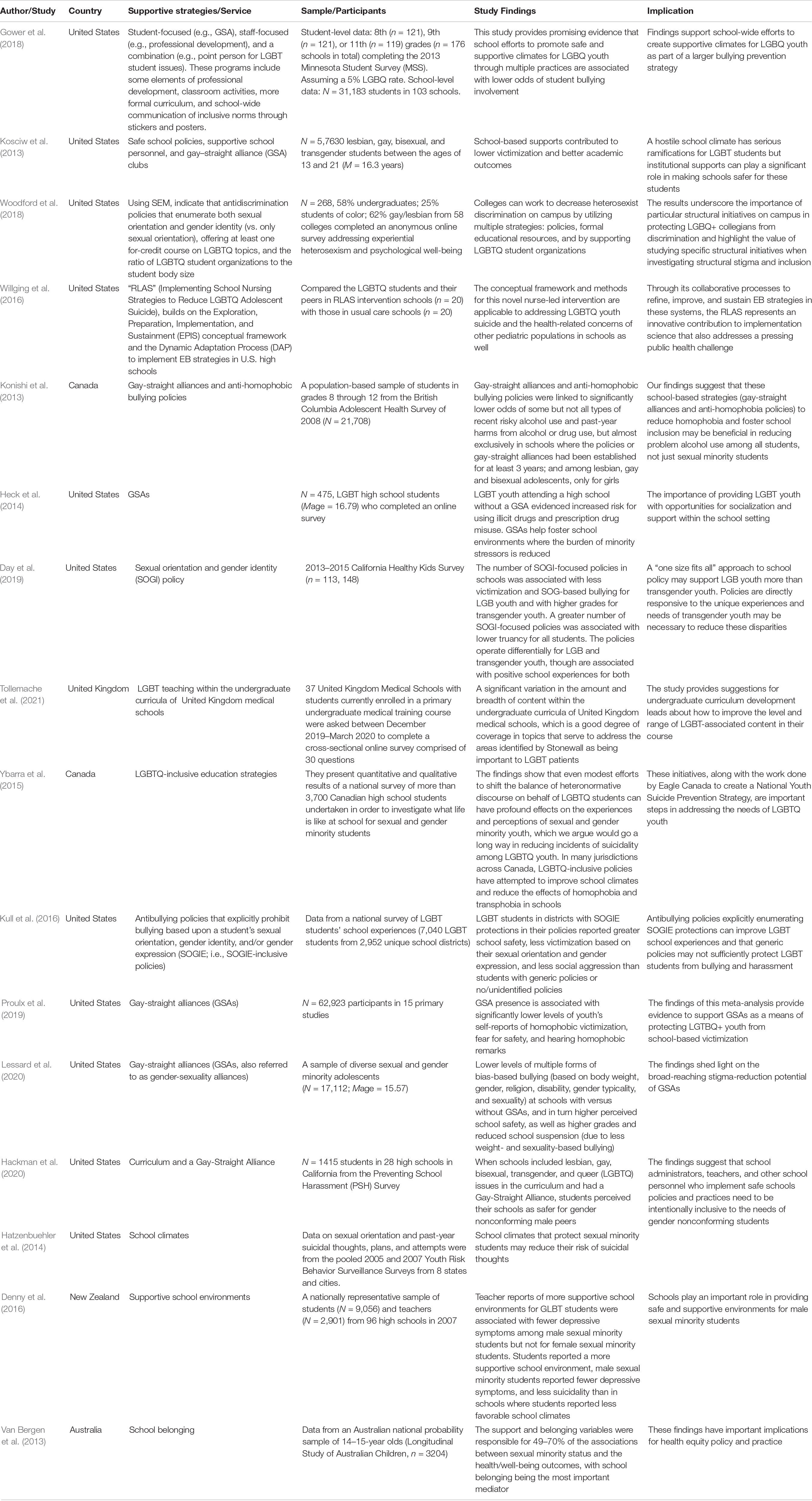

The effects of loneliness, marginalization, and inequality on psychological health and the assessment of health determinants have been examined in a number of quantitative studies conducted with LGBTQ adolescents (Table 1). The prevalence of suicidal ideation, depression, and drug abuse among LGBTQ adolescents is considerably higher than that of their heterosexual counterparts, highlighting the seriousness and frequency of LGBTQ adolescents’ experiences of inequalities (Price-Feeney et al., 2020). It has been found that LGBTQ adolescents have higher incidences of aggression and victimization as well as more despair and suicidal behavior. These adolescents are also more likely to develop psychosocial disorders, such as alcohol and drug problems and eating disorders (Lannoy et al., 2020). Associations have been established between peer victimization and adverse psychological wellbeing indictors, such as depression, distress, and suicidal tendencies, along with liquor and drug misuse and compromised academic performance, including reduced school involvement and interruptions to academic paths (Brown et al., 2020).

Table 1. Summarizes the findings of several academic trials and their connection with the mental health impacts on LGBT students in review.

Quantitative analysis has also centered on defining vulnerability and preventive variables for the psychological wellbeing of LGBTQ adolescents, resulting in the establishment of mitigation, diagnosis, and recovery guidelines, as well as shaping legislation and policy (Lockett, 2020). Family affirmation, for example, provides a protective factor against depression, drug misuse, and suicide among LGBTQ adolescents and young adults. It increases self-esteem, support networks, general wellness, and is a buffer against depression, drug misuse, and suicide (Reyes et al., 2020; Lampis et al., 2021). Thus, household initiatives that inspire and support parents, care providers, and other close relatives have been identified as a beneficial paradigm for preventive strategies. This highlights the strengths and positive impact of constructive parent-child dynamics. Additionally, a recent comprehensive study (Flores A. R. et al., 2020; Flores D. D. et al., 2020) found that elevated degrees of community protection were correlated with a healthy ego while a shortage of community protection was linked with increased levels of stress, anxiety, guilt, alcohol and substance consumption, practices of unsafe sex, and lower levels of self-esteem. McDonald et al. (2021) emphasized the importance of acceptance by family and caregivers and a feeling of connection to a friend/community in LGBTQ youth’s psychological wellbeing.

Impact on Psychological Wellbeing Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Students

Mental health entails a positive relationship with people and the pursuit of a productive and fulfilling existence. It has been shown that those who have a high level of mental health tend to be more lighthearted and lead more energetic and pleasant lives (Chan et al., 2021). Owing to their heightened likelihood of experiencing psychological challenges, LGBTQ adolescents are among the most disadvantaged populations in the community (Detrie and Lease, 2007; McGlashan and Fitzpatrick, 2017). According to figures on the LGBTQ community, New Zealand has an estimated 8% of LGB adolescents, the United States has an estimated 7–8% of LGB adolescents (Wilson et al., 2014). According to Aranmolate et al. (2017), LGBTQ adolescents’ psychological health difficulties are associated with a lack of familial recognition and experiences of harassment. They are more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to encounter violent conditions at home and in the larger community, and are exposed to overt and implicit discrimination, violence, vulnerability, and injustice, all of which have a negative effect on psychological wellbeing (Bertrand et al., 2005; Matebeni et al., 2018; Simons and Russell, 2021).

A recent study (Lucassen et al., 2017) found that LGBTQ adolescents were three times more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to exhibit depressive conditions and twice as likely to harm themselves. In the study, 20% of participants attempted suicide, and over half considered it. LGBTQ adolescents were more likely than their non-LGBTQ counterparts to seek therapy in the previous 12 months, at 41.0%. Additionally, the Youth 2000 Survey (Archer et al., 2021) indicates that LGBTQ youth face a higher risk of alcohol or substance usage. In Scotland over the given time, 40% of LGBT adolescents registered as having a psychological disorder, compared to 25% of non-sexual and gender marginalized adolescents and bullying was described as a significant source of anxiety among LGBT participants (Bradbury, 2020; Pachankis et al., 2020).

LGBTQ adolescents, in general, have distinct risk factors, and when such specific threats are associated with common stressful events, this minority group tend to experience increased self-harm, suicidal tendencies, and emotional instability (Eisenberg et al., 2020; Hatchel et al., 2021). These risk factors persist throughout adulthood, with Sexual/Gender Minority (SGM) person 400% more likely to commit suicide and both males and females 150% more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and drug abuse (King et al., 2008; Lothwell et al., 2020). In a 2011 article (Chakraborty et al., 2011), it was found that gay/lesbian individuals experience elevated degrees of psychological discomfort in comparison to straight people.

According to previous studies engaging with minority stress theory (Cyrus, 2017; Fulginiti et al., 2020; Table 1), the rising likelihood of psychological health problems among LGBTQ adolescents is a result of increased social stress, which includes stigma, discrimination, bias, and victimization. Adolescence is a crucial period in cognitive growth, with elevated impact of pressure on psychological wellbeing and an increased susceptibility to substance use (Tavarez, 2020; Fulginiti et al., 2021). At this critical juncture, experiencing discrimination at the hands of academic, clinical, or religious establishments, or internalizing victimization as a consequence of discrimination, transphobia, or biphobia, will create substantial mental difficulties for LGBTQ adolescents (Budge et al., 2020; Formby and Donovan, 2020). Marginalization, loneliness, alienation, bullying, and a lack of supportive grown-ups and spaces all contribute to social tension among LGBTQ adolescents (Grossman et al., 2009; Hafeez et al., 2017).

Stigma establishes individual obstacles for vulnerable adolescents, stopping them from seeking resources (Cortes, 2017). According to Hackman et al. (2020), humiliation, guilt, and apprehension of judgment are all factors explaining why LGBTQ adolescents stop accessing psychological health care. LGBTQ adolescents who are homeless, remote, or drug addicts experience greater obstacles to obtaining assistance (Lucassen et al., 2011, Table 1). If parental or specialist assistance is unavailable, LGBTQ adolescents may seek assistance from peers and resources on online platforms (LaSala, 2015; Pullen Sansfaçon et al., 2020; Town et al., 2021).

Recognition by family members has also been described as a significant factor influencing the psychological wellbeing of LGBTQ adolescents (Afdal and Ilyas, 2020; Buriæ et al., 2020). According to Strauss et al. (2020), familial engagement is represented by openness and sensitivity to the demands of a child. As LGBTQ adolescents feel welcomed and respected, they are more likely to reveal their non-normative identities to family members (Hagai et al., 2020; Endo, 2021). Nevertheless, a huge percentage of LGBTQ adolescents are homeless, indicating that family exclusion is a major risk factor for poor psychological wellbeing (Travers et al., 2020; MacMullin et al., 2021). Durso and Gates (2012) released the findings of a nationwide internet study in the United States and discovered that nearly 68% of their LGBT homeless clients had encountered family abandonment and over 54% had encountered domestic violence.

Adolescence is a transitional stage during which adolescents discover their identity, and for LGBTQ adolescents, it is also the period during which they gain an awareness of their own gender identity and sexual preference (Prock and Kennedy, 2020). Research has shown shifting relationships throughout adolescence and young adulthood, with a corresponding change in commitment to friends and social classes apart from the family, as well as to entities such as education, colleges, religious or political communities (Huang, 2020; Jordan, 2020). Recognition by support communities is a powerful preventive mechanism for LGBTQ children and adolescents (Call et al., 2021). A LGBTQ-friendly climate has a profound impact on their psychological development and well-being. Perceptions of social integration with grown-ups help LGBTQ adolescents overcome challenges, especially during the precarious developmental phase when they are developing their sense of self (Proulx et al., 2019).

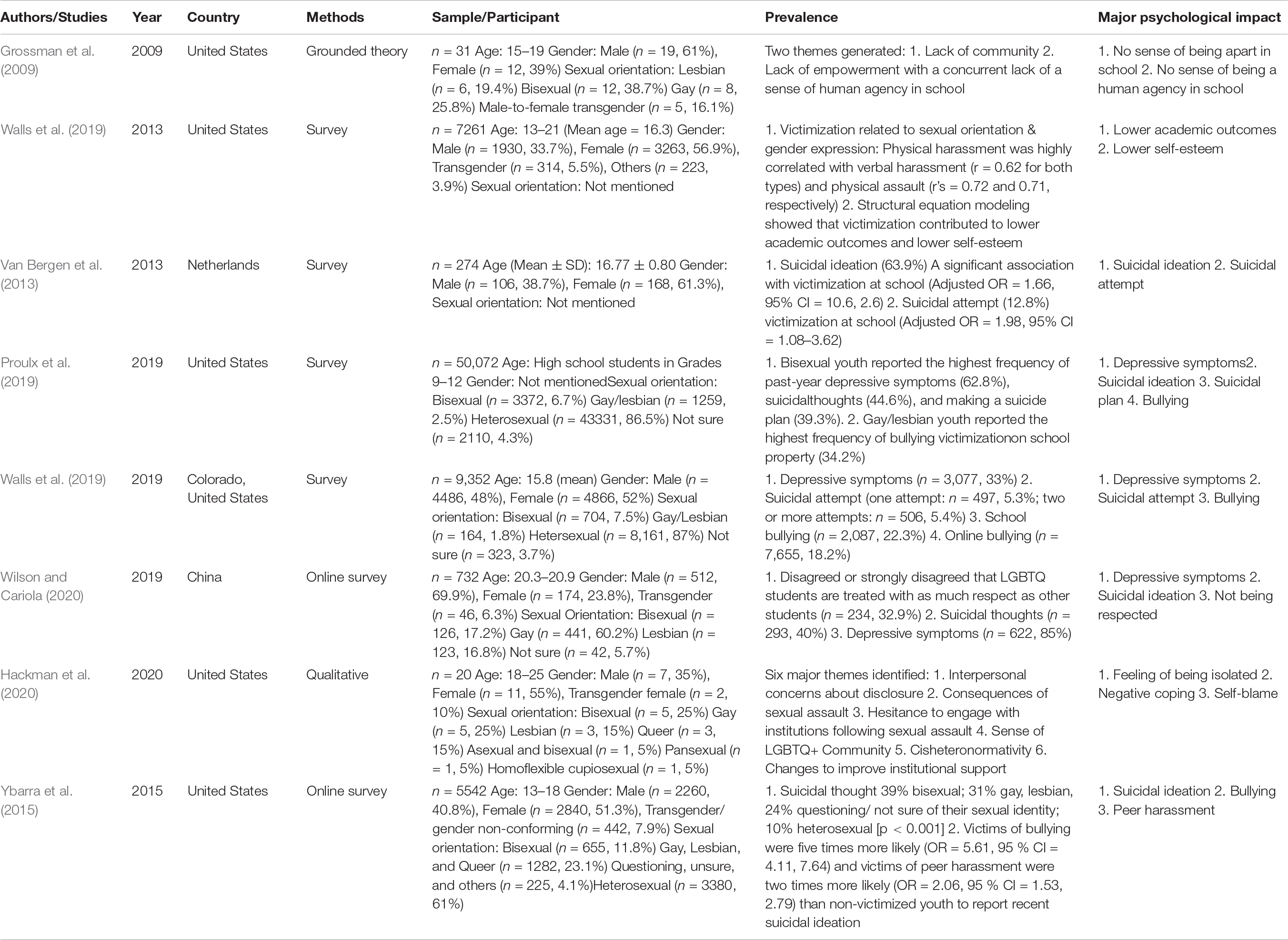

The Supportive Strategies for Inclusive Schools

The interaction between a person and his or her environment affects personal growth and development according to the social ecological model. The risk of suicidal behaviors among LGBTQ adolescents is influenced by a number of contextual factors including schools. Institute of Medicine asked for further research in 2011, focusing specifically on the impact of protective school policies and students’ perceptions of their school environments on their health and well-being (Ancheta et al., 2021). Much research pointed out that schools are well-positioned to address health disparities by creating safe and supportive school climates for LGBTQ youth (Gower et al., 2018; Woodford et al., 2018; Table 2). Evidence shows that a safe and supportive climate is related to lower odds of student bullying involvement, some types of risky alcohol use and drug use, and victimization. A safe climate event may reduce LGBTQ adolescents’ risk of suicidal thoughts (Konishi et al., 2013; Kosciw et al., 2013; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014; Gower et al., 2018). Having a supportive school environment and a sense of belonging to school were associated with lower levels of minority stress and better academic results, health, and wellbeing among LGBTQ students (Denny et al., 2016; Perales and Campbell, 2020). Research has suggested multiple strategies for school-based support, including policies, supporting LGBTQ students organizations, educator intervention and LGBTQ related curriculum (Konishi et al., 2013; Kosciw et al., 2013).

More inclusive policies could contribute to the school climate at the macro level. These policies include antidiscrimination policies (Woodford et al., 2018) and anti-homophobic bullying policies (Konishi et al., 2013). Compared with students at schools with generic policies or no/unidentified policies, LGBTQ students in districts with sexual orientation, gender identity, and/or gender expression (SOGIE) protections in their policies reported greater school safety, less victimization based on their sexual orientation and gender expression, and less social aggression (Kull et al., 2016). Moreover, a greater number of SOGIE-focused policies was associated with lower truancy for all students (Day et al., 2019).

Furthermore, gay–straight alliance (GSAs) has been one of the major sources of support in high schools in the United States and Canada. GSAs are student-led, school-based clubs that aim to provide a safe environment in the school context for LGBTQ students, as well as their straight allies (Toomey et al., 2011. In recent decades, the number of GSAs in schools has increased dramatically, with over 4,000 GSAs registered in the United States (Toomey et al., 2011). Research has suggested that a high school with a GSA can decrease LGBTQ students-risks for using illicit drugs and prescription drug misuse and reduce their burden of minority stressors (Heck et al., 2014). GSAs foster inclusive school environments not only for LGBT + students but for all students, thereby contributing to lower levels of homonegative victimization, fear for safety, homophobic remarks and multiple forms of bias-based bullying (based on body weight, gender, religion, disability, gender typicality, sexuality) (Marx and Kettrey, 2016; Lessard et al., 2020).

Educator intervention and LGBTQ related curriculum also constitute prevention strategies of inclusive schools. Teachers and school staff—in particular, the medical staff—could be provided with LGBTQ sensitive training and LGBTQ medical curricula, which are important for supportive climate building and LGBTQ students’ wellbeing (Gower et al., 2018; Tollemache et al., 2021). By strengthening teachers’ analytical awareness of alienation experienced by children and adolescents, teachers may flourish in school, promoting equal opportunity principles and teaching students about love and consideration, justice and freedom (Glazzard and Stones, 2020). Willging et al. (2016) demonstrated that RLAS (Implementing School Nursing Strategies to Reduce LGBTQ Adolescent Suicide) is applicable to novel nurse-led intervention to address LGBTQ youth suicide and health-related concerns of other students. All these strategies have shown the importance of structural initiatives on campus in protecting LGBTQ students from discrimination (Woodford et al., 2018).

Discussion

Around the world, the importance of an inclusive school climate to LGBTQ student has been suggested and advocated for reducing the risk of violence and discrimination and enhancing their psychological wellbeing. However, most quantitative studies were concentrated in the Northern America, particularly the United States. There remains a lack of research about LGBTQ students’ wellbeing in developing countries. Moreover, much research used the data from health or psychological surveys to state that policies, GSAs club, educator intervention, and LGBTQ related curriculum could improve the school climate; nevertheless, less experimental research could provide evidence and specific methods to guide schools. Further, due to the disparities among LGBTQ students, a ‘one size fits all’ approach to school policy might not fit all LGBTQ students. Day et al. (2019) have demonstrated that SOGIE-focused policy may support LGBTQ youth more than transgender youth.

Toomey et al. (2011) have pointed out that students perceived their schools as safer for gender nonconforming male peers when schools included LGBTQ issues in the curriculum and had GSAs. Given the growing significance of LGBTQ people as active, respected, and noticeable members of society (Chan, 2021b), it is critical to promote LGBTQ acceptance within and beyond campus (Stones and Glazzard, 2020). LGBTQ students are more likely to report negative school performance when confronted with significant obstacles such as bullying, assault, and a lack of role models. Schools should uphold diversity, decency, compassion, and consideration (Chan, 2021c). Additionally, deans of medical schools have suggested to increase teaching materials related to LGBTQ issues in order to improve medical services in schools (Van Bergen et al., 2013).

This article has collected and analyzed the existing literature to indicate violence and prejudice as fundamental causes of psychological problems among LGBTQ adolescents and identify supportive strategies for schools to build a LGBTQ-friendly environment. However, it is limited because previous studies still primarily focus on developed countries and offer limited insights into possible interventions in different contexts. This study has suggested how treatments should be further developed to guarantee lasting welfare and inclusion of LGBTQ adolescents.

Conclusion

As LGBTQ individuals are becoming a more dedicated, respected, and observable component of humanity (Chan, 2021a), schools play a crucial part in ensuring that all children and adolescents realize that prejudice and discrimination are unacceptable. By teaching young people about all kinds of discrimination and their negative impact, critical pedagogy plays a crucial part in advancing human rights. It inspires optimism for the potential creation of a more just and fair society and empowers young people to be ethical new generations (Glazzard and Stones, 2021). Mental health problems faced by LGBTQ youth are largely associated with discrimination, prejudice, and a lack of support from family, schools, and society at large. Increasing levels of support and acceptance for LGBTQ youth will most likely require political and social change in today’s world, such as legalizing same-sex marriage and liberalizing cultural norms. Future research should continue to attend to LGBTQ students’ health and educational needs and identify possible interventions in order to enhance their wellbeing.

Author Contributions

AC and DW carried out the outline of this manuscript. AC wrote the manuscript with support from JH and IL. EY and IL gave valuable comments and suggestion. EY helped to supervise the whole manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by funding from the Department of Applied Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

AC and DW would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Ben Ku from the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

References

Afdal, A., and Ilyas, A. (2020). How psychological well-being of adolescent based on demography indicators? JPPI 6, 53–68.

Alonzo, D. J., and Buttitta, D. J. (2019). Is “coming out” still relevant? Social justice implications for LGB-membered families. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 11, 354–366.

Ancheta, A. J., Bruzzese, J. M., and Hughes, T. L. (2021). The Impact of Positive School Climate on Suicidality and Mental Health Among LGBTQ Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Sch. Nurs. 37, 75–86. doi: 10.1177/1059840520970847

Aranmolate, R., Bogan, D. R., Hoard, T., and Mawson, A. R. (2017). Suicide Risk Factors among LGBTQ Youth: Review. JSM Schizophr. 2:1011.

Archer, D., Clark, T. C., Lewycka, S., DaRocha, M., and Fleming, T. (2021). Youth19 Rangatahi Smart Survey, Data Dictionary (Edited from The Adolescent Health Research Group Previous Youth2000 series Data Dictionaries). Wellington: The University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington.

Bertrand, M., Chugh, D., and Mullainathan, S. (2005). Implicit discrimination. Am. Econom. Rev. 95, 94–98.

Bradbury, A. (2020). Mental health stigma: The impact of age and gender on attitudes. Commun. Mental Health J. 56, 933–938. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00559-x

Brown, C., Porta, C. M., Eisenberg, M. E., McMorris, B. J., and Sieving, R. E. (2020). Family Relationships and the Health and Well-Being of Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth: A Critical Review. LGBT Health 7, 407–419. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0200

Budge, S. L., Domínguez, S. Jr., and Goldberg, A. E. (2020). Minority stress in nonbinary students in higher education: The role of campus climate and belongingness. Psychol. Sexual Orient. Gender Divers. 7:222.

Buriæ, J., Garcia, J. R., and Štulhofer, A. (2020). Is sexting bad for adolescent girls’ psychological well-being? A longitudinal assessment in middle to late adolescence. New Med. Soc. 2020:1461444820931091.

Call, D. C., Challa, M., and Telingator, C. J. (2021). Providing Affirmative Care to Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth: Disparities, Interventions, and Outcomes. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 23, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01245-9

Chakraborty, A., McManus, S., Brugha, T. S., Bebbington, P., and King, M. (2011). Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. Br. J. Psychiatry 198, 143–148. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082271

Chan, A. S. W. (2021b). Book Review: Safe Is Not Enough: Better Schools for LGBTQ Students (Youth Development and Education Series). Front. Psychol. 12:704995. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704995

Chan, A. S. W. (2021c). Book Review: The Educator’s Guide to LGBT+ Inclusion: A Practical Resource for K-12 Teachers, Administrators, and School Support Staff. Front. Psychol. 12:692343. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.692343

Chan, A. S. W. (2021a). Book Review: The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle. Front. Psychol. 12:677734. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.677734

Chan, A. S. W., Ho, J. M. C., Li, J. S. F., Tam, H. L., and Tang, P. M. K. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on Psychological Well-Being of Older Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Front. Med. 8:666973. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.666973

Cortes, R. N. (2017). Stigma and discrimination experiences in health care settings more evident among transgender people than males having sex with males (MSM) in Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philippines and Timor leste: key results. Sex. Transm. Infect. 93:A202. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053264.525

Cyrus, K. (2017). Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. J. Gay Lesbian Mental Health 21, 194–202. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2017.1320739

Daniele, M., Fasoli, F., Antonio, R., Sulpizio, S., and Maass, A. (2020). Gay voice: Stable marker of sexual orientation or flexible communication device? Arch. Sexual Behav. 49, 2585–2600. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01771-2

Day, J. K., Ioverno, S., and Russell, S. T. (2019). Safe and supportive schools for LGBT youth: Addressing educational inequities through inclusive policies and practices. J. School Psychol. 74, 29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.05.007

Delozier, A. M., Kamody, R. C., Rodgers, S., and Chen, D. (2020). Health disparities in transgender and gender expansive adolescents: A topical review from a minority stress framework. J. Pediatric Psychol. 45, 842–847. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa040

Denny, S., Lucassen, M. F. G., Stuart, J., Fleming, T., Bullen, P., Peiris-John, R., et al. (2016). The Association Between Supportive High School Environments and Depressive Symptoms and Suicidality Among Sexual Minority Students. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 45, 248–261. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.958842

Detrie, P. M., and Lease, S. H. (2007). The relation of social support, connectedness, and collective self-esteem to the psychological well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J. Homosex. 53, 173–199. doi: 10.1080/00918360802103449

Durso, L. E., and Gates, G. J. (2012). Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund.

Eisenberg, M. E., Gower, A. L., Watson, R. J., Porta, C. M., and Saewyc, E. M. (2020). LGBTQ Youth-Serving Organizations: What Do They Offer and Do They Protect Against Emotional Distress? Ann. LGBTQ Public Populat. Health 1, 63–79. doi: 10.1891/lgbtq.2019-0008

Endo, R. (2021). Diversity, equity, and inclusion for some but not all: LGBQ Asian American youth experiences at an urban public high school. Multicult. Educat. Rev. 13, 25–42. doi: 10.1080/2005615x.2021.1890311

Evans-Polce, R. J., Veliz, P. T., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T. L., and McCabe, S. E. (2020). Associations between sexual orientation discrimination and substance use disorders: differences by age in US adults. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 55, 101–110. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01694-x

Fields, X., and Wotipka, C. M. (2020). Effect of LGBT anti-discrimination laws on school climate and outcomes for lesbian, gay, and bisexual high school students. J. LGBT Youth 2020, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2020.1821276

Flores, A. R., Langton, L., Meyer, I. H., and Romero, A. P. (2020). Victimization rates and traits of sexual and gender minorities in the United States: Results from the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017. Sci. Adv. 6:eaba6910. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba6910

Flores, D. D., Meanley, S. P., Bond, K. T., Agenor, M., Relf, M. V., and Barroso, J. V. (2020). Topics for Inclusive Parent-Child Sex Communication by Gay, Bisexual, Queer Youth. Behav. Med. 2020, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1700481

Formby, E., and Donovan, C. (2020). Sex and relationships education for LGBT+ young people: lessons from UK youth work. Sexualities 23, 1155–1178. doi: 10.1177/1363460719888432

Fulginiti, A., Goldbach, J. T., Mamey, M. R., Rusow, J., Srivastava, A., Rhoades, H., et al. (2020). Integrating minority stress theory and the interpersonal theory of suicide among sexual minority youth who engage crisis services. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 50, 601–616. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12623

Fulginiti, A., Rhoades, H., Mamey, M. R., Klemmer, C., Srivastava, A., Weskamp, G., et al. (2021). Sexual minority stress, mental health symptoms, and suicidality among LGBTQ youth accessing crisis services. J. Youth Adolesc. 50, 893–905. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01354-3

Glazzard, J., and Stones, S. (2020). Supporting student teachers with minority identities: The importance of pastoral care and social justice in initial teacher education. Res. Informed Teacher Learn. 2020, 127–138.

Glazzard, J., and Stones, S. (2021). Running Scared? A Critical Analysis of LGBTQ+ Inclusion Policy in Schools. Front. Sociol. 6:613283. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.613283

Gower, A. L., Forster, M., Gloppen, K., Johnson, A. Z., Eisenberg, M. E., Connett, J. E., et al. (2018). School practices to foster LGBT-supportive climate: Associations with adolescent bullying involvement. Prevent. Sci. 19, 813–821. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0847-4

Grossman, A. H., Haney, A. P., Edwards, P., Alessi, E. J., Ardon, M., and Howell, T. J. (2009). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth Talk about Experiencing and Coping with School Violence: A Qualitative Study. J. LGBT Youth 6, 24–46. doi: 10.1080/19361650802379748

Hackman, C. L., Bettergarcia, J. N., Wedell, E., and Simmons, A. (2020). Qualitative exploration of perceptions of sexual assault and associated consequences among LGBTQ+ college students. Psychol. Sex. Orient. Gender Divers. 2020:sgd0000457. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000457

Hafeez, H., Zeshan, M., Tahir, M. A., Jahan, N., and Naveed, S. (2017). Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus 9:e1184. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1184

Hagai, E. B., Annechino, R., Young, N., and Antin, T. (2020). Intersecting sexual identities, oppressions, and social justice work: Comparing LGBTQ Baby Boomers to Millennials who came of age after the 1980s AIDS epidemic. J. Soc. Iss. 76, 971–992. doi: 10.1111/josi.12405

Hatchel, T., Torgal, C., El Sheikh, A. J., Robinson, L. E., Valido, A., and Espelage, D. L. (2021). LGBTQ youth and digital media: online risks. Child Adolesc. Online Risk Expos. 2021, 303–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.023

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Birkett, M., Van Wagenen, A., and Meyer, I. H. (2014). Protective school climates and reduced risk for suicide ideation in sexual minority youths. Am. J. Public Health 104, 279–286. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301508

Heck, N. C., Livingston, N. A., Flentje, A., Oost, K., Stewart, B. T., and Cochran, B. N. (2014). Reducing risk for illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Addict. Behav. 39, 824–828. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.007

Higbee, M., Wright, E. R., and Roemerman, R. M. (2020). Conversion Therapy in the Southern United States: Prevalence and Experiences of the Survivors. J. Homosex. 2020, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1840213

Huang, Y. T. (2020). Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) Young Adults’ Relational Well-Being Before and After Taiwanese Legalization of Same-Sex Marriage: A Qualitative Study Protocol. Int. J. Qualitat. Methods 19:1609406920933398.

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Scales, L., et al. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Suppl. 69:19. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3

Jordan, F. (2020). Changing the Narrative for LGBTQ Adolescents: A Literature Review and Call for Research into Narrative Therapy to Improve Family Acceptance of LGBTQ Teens. Counsel. Fam. Therapy Scholar. Rev. 3:6.

Kachanoff, F. J., Cooligan, F., Caouette, J., and Wohl, M. J. (2020). Free to fly the rainbow flag: the relation between collective autonomy and psychological well-being amongst LGBTQ+ individuals. Self Ident. 2020, 1–33.

Khanlou, N., Koh, J. G., and Mill, C. (2008). Cultural Identity and Experiences of Prejudice and Discrimination of Afghan and Iranian Immigrant Youth. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 6, 494–513. doi: 10.1007/s11469-008-9151-7

King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., et al. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

Kolbe, S. M. (2020). Creating Safety in Schools for LGBT and Gender Non-Conforming Students. BU J. Graduate Stud. Educat. 12, 17–21.

Konishi, C., Saewyc, E., Homma, Y., and Poon, C. (2013). Population-level evaluation of school-based interventions to prevent problem substance use among gay, lesbian and bisexual adolescents in Canada. Prevent. Med. 57, 929–933. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.031

Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., Kull, R. M., and Greytak, E. A. (2013). The Effect of Negative School Climate on Academic Outcomes for LGBT Youth and the Role of In-School Supports. J. School Viol. 12, 45–63. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2012.732546

Kull, R. M., Greytak, E. A., Kosciw, J. G., and Villenas, C. (2016). Effectiveness of school district antibullying policies in improving LGBT youths’ school climate. Psychol. Sex. Orient. Gender Divers. 3:407.

Kurian, N. (2020). Rights-protectors or rights-violators? Deconstructing teacher discrimination against LGBT students in England and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child as an advocacy tool. Int. J. Hum. Rights 24, 1080–1102.

Lampis, J., De Simone, S., and Belous, C. K. (2021). Relationship satisfaction, social support, and psychological well-being in a sample of Italian lesbian and gay individuals. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 17:49–62.

Lannoy, S., Mange, J., Leconte, P., Ritz, L., Gierski, F., Maurage, P., et al. (2020). Distinct psychological profiles among college students with substance use: A cluster analytic approach. Addict. Behav. 109:106477. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106477

LaSala, M. C. (2015). Condoms and connection: Parents, gay and bisexual youth, and HIV risk. J. Marital Fam. Therapy 41, 451–464. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12088

Lessard, L. M., Watson, R. J., and Puhl, R. M. (2020). Bias-based bullying and school adjustment among sexual and gender minority adolescents: the role of gay-straight alliances. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1094–1109.

Lockett, G. (2020). Spiritual, Cultural, and Religious Influences on the Psychological Well-being of LGBTQ Individuals. Ph. D. Thesis. Tennessee: Tennessee State University.

Lo, I. P. Y. (2020). Family formation among lalas (lesbians) in urban China: strategies for forming families and navigating relationships with families of origin. J. Sociol. 56, 629–645.

Lothwell, L. E., Libby, N., and Adelson, S. L. (2020). Mental Health Care for LGBT Youths. Focus 18, 268–276. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20200018

Lucassen, M. F. G., Stasiak, K., Samra, R., Frampton, C. M. A., and Merry, S. N. (2017). Sexual minority youth and depressive symptoms or depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Austral. N Z. J. Psychiatry 51, 774–787. doi: 10.1177/0004867417713664

Lucassen, M. F., Merry, S. N., Robinson, E. M., Denny, S., Clark, T., Ameratunga, S., et al. (2011). Sexual attraction, depression, self-harm, suicidality and help-seeking behaviour in New Zealand secondary school students. Austral. N Z. J. Psychiatry 45, 376–383.

MacMullin, L. N., Bokeloh, L. M., Nabbijohn, A. N., Santarossa, A., van der Miesen, A. I., Peragine, D. E., et al. (2021). Examining the Relation Between Gender Nonconformity and Psychological Well-Being in Children: The Roles of Peers and Parents. Arch. Sex. Behav. 50, 823–841. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01832-6

Mallory, C., Vasquez, L. A., Brown, T. N., Momen, R. E., and Sears, B. (2021). The Impact of Stigma and Discrimination Against LGBT People in West Virginia. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute.

Marx, R. A., and Kettrey, H. H. (2016). Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 1269–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0501-7

Matebeni, Z., Monro, S., and Reddy, V. (eds) (2018). Queer in Africa: LGBTQI Identities, Citizenship, and Activism. London: Routledge.

Mateo, C. M., and Williams, D. R. (2020). Addressing bias and reducing discrimination: The professional responsibility of health care providers. Acad. Med. 95, S5–S10. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003683

McDonald, S. E., Murphy, J. L., Tomlinson, C. A., Matijczak, A., Applebaum, J. W., Wike, T. L., et al. (2021). Relations between sexual and gender minority stress, personal hardiness, and psychological stress in emerging adulthood: Examining indirect effects via human-animal interaction. Youth Soc. 2021:0044118X21990044.

McGlashan, H., and Fitzpatrick, K. (2017). LGBTQ youth activism and school: Challenging sexuality and gender norms. Health Educat. 117, 485–497. doi: 10.1108/he-10-2016-0053

Minturn, M. S., Martinez, E. I., Le, T., Nokoff, N., Fitch, L., Little, C. E., et al. (2021). Early Intervention for LGBTQ Health: A 10-Hour Curriculum for Preclinical Health Professions Students. MedEdPORTAL 17:11072. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11072

Ocasio, M. A., Tapia, G. R., Lozano, A., Carrico, A. W., and Prado, G. (2020). Internalizing symptoms and externalizing behaviors in Latinx adolescents with same sex behaviors in Miami. J. LGBT Youth 2020, 1–17.

Pachankis, J. E., Clark, K. A., Burton, C. L., Hughto, J. M. W., Bränström, R., and Keene, D. E. (2020). Sex, status, competition, and exclusion: Intraminority stress from within the gay community and gay and bisexual men’s mental health. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 119:282. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000282

Perales, F., and Campbell, A. (2020). Health Disparities Between Sexual Minority and Different-Sex-Attracted Adolescents: Quantifying the Intervening Role of Social Support and School Belonging. LGBT Health 7, 146–154. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0285

Platero, R. L., and López-Sáez, M. Á (2020). Support, cohabitation and burden perception correlations among LGBTQA+ youth in Spain in times of COVID-19. J. Children’s Serv. 15, 221–228. doi: 10.1108/jcs-07-2020-0037

Poynter, K. J., and Washington, J. (2005). Multiple identities: Creating community on campus for LGBT students. New Direct. Stud. Serv. 2005, 41–47. doi: 10.1002/ss.172

Price-Feeney, M., Green, A. E., and Dorison, S. (2020). Understanding the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth. J. Adolesc. Health 66, 684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.314

Prock, K. A., and Kennedy, A. C. (2020). Characteristics, experiences, and service utilization patterns of homeless youth in a transitional living program: Differences by LGBQ identity. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 116:105176. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105176

Proulx, C. N., Coulter, R. W., Egan, J. E., Matthews, D. D., and Mair, C. (2019). Associations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning–inclusive sex education with mental health outcomes and school-based victimization in US high school students. J. Adolesc. Health 64, 608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.012

Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Kirichenko, V., Holmes, C., Feder, S., Lawson, M. L., Ghosh, S., et al. (2020). Parents’ journeys to acceptance and support of gender-diverse and trans children and youth. J. Fam. Iss. 41, 1214–1236.

Ramasamy, V. R. (2020). “Young, disabled and LGBT+ identities,” in Young, Disabled and LGBT+: Voices, Identities and Intersections, eds A. Toft and A. Franklin (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis), 159–178.

Reyes, M. E. S., Davis, R. D., Yapcengco, F. L., Bordeos, C. M. M., Gesmundo, S. C., and Torres, J. K. M. (2020). Perceived Parental Acceptance, Transgender Congruence, and Psychological Well-Being of Filipino Transgender Individuals. North Am. J. Psychol. 22, 135–152.

Savin-Williams, R. C. (2020). “Coming out to parents and self-esteem among gay and lesbian youths,” in Homosexuality and the Family, ed. F. W. Bozett (London: Routledge), 1–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v18n01_01

Simons, J. D., and Russell, S. T. (2021). Educator interaction with sexual minority youth. J. Gay Lesb. Soc. Serv. 2021, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2021.1897052

Skovdal, M., and Campbell, C. (2015). Beyond education: What role can schools play in the support and protection of children in extreme settings? Int. J. Educat. Dev. 41, 175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.02.005

Standley, C. J. (2020). Expanding our paradigms: Intersectional and socioecological approaches to suicide prevention. Death Stud. 2020, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1725934

Stones, S., and Glazzard, J. (2020). Tales From the Chalkface: Using Narratives to Explore Agency, Resilience, and Identity of Gay Teachers. Front. Sociol. 5:52. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.00052

Strauss, P., Cook, A., Winter, S., Watson, V., Wright Toussaint, D., and Lin, A. (2020). Mental health issues and complex experiences of abuse among trans and gender diverse young people: findings from trans pathways. LGBT Health 7, 128–136. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0232

Tavarez, J. (2020). “I can’t quite be myself”: Bisexual-specific minority stress within LGBTQ campus spaces. J. Divers. Higher Educat. [Preprint].

Tollemache, N., Shrewsbury, D., and Llewellyn, C. (2021). Que (e) rying undergraduate medical curricula: a cross-sectional online survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer content inclusion in UK undergraduate medical education. BMC Med. Educat. 21, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02532-y

Toomey, R. B., Ryan, C., Diaz, R. M., and Russell, S. T. (2011). High school gay–straight alliances (GSAs) and young adult well-being: An examination of GSA presence, participation, and perceived effectiveness. Appl. Dev. Sci. 15, 175–185. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.607378

Town, R., Hayes, D., Fonagy, P., and Stapley, E. (2021). A qualitative investigation of LGBTQ+ young people’s experiences and perceptions of self-managing their mental health. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01783-w

Travers, Á, Armour, C., Hansen, M., Cunningham, T., Lagdon, S., Hyland, P., et al. (2020). Lesbian, gay or bisexual identity as a risk factor for trauma and mental health problems in Northern Irish students and the protective role of social support. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 11:1708144. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1708144

Van Bergen, D. D., Bos, H. M. W., Van Lisdonk, J., Keuzenkamp, S., and Sandfort, T. G. M. (2013). Victimization and suicidality among Dutch lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Am. J. Public Health 103, 70–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300797

Walls, N. E., Atteberry-Ash, B., Kattari, S. K., Peitzmeier, S., Kattari, L., and Langenderfer- Magruder, L. (2019). Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, Mental Health, and Bullying as Predictors of Partner Violence in a Representative Sample of Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 64, 86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.011

Willging, C. E., Green, A. E., and Ramos, M. M. (2016). Implementing school nursing strategies to reduce LGBTQ adolescent suicide: a randomized cluster trial study protocol. Implement. Sci. 11, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0507-2

Wilson, B. D. M., Cooper, K., Kastanis, A., and Nezhad, S. (2014). Sexual and Gender Minority Youth in Foster Care: Assessing Disproportionality and Disparities in Los Angeles. Los Angeles, CA: The William Institute.

Wilson, C., and Cariola, L. A. (2020). LGBTQI+ youth and mental health: a systematic review of qualitative research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 5, 187–211. doi: 10.1111/appy.12199

Woodford, M. R., Kulick, A., Garvey, J. C., Sinco, B. R., and Hong, J. S. (2018). LGBTQ policies and resources on campus and the experiences and psychological well-being of sexual minority college students: Advancing research on structural inclusion. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gender Divers. 5:445. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000289

Keywords: social inclusion and exclusion, discrimination, LGBTQ students, mental health, psychological impact

Citation: Chan ASW, Wu D, Lo IPY, Ho JMC and Yan E (2022) Diversity and Inclusion: Impacts on Psychological Wellbeing Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Communities. Front. Psychol. 13:726343. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.726343

Received: 16 June 2021; Accepted: 05 January 2022;

Published: 29 April 2022.

Edited by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Cheng-Fang Yen, Kaohsiung Medical University, TaiwanLudgleydson Fernandes De Araujo, Federal University of the Parnaíba Delta, Brazil

Copyright © 2022 Chan, Wu, Lo, Ho and Yan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alex Siu Wing Chan, Y2hhbnN3LmFsZXhAZ21haWwuY29t; Elsie Yan, ZWxzaWUueWFuQHBvbHl1LmVkdS5oaw==

Alex Siu Wing Chan

Alex Siu Wing Chan Dan Wu

Dan Wu Iris Po Yee Lo

Iris Po Yee Lo Jacqueline Mei Chi Ho2

Jacqueline Mei Chi Ho2 Elsie Yan

Elsie Yan