Abstract

Adolescence is a period of several changes and a time when young people are confronted with some difficult tasks of dealing with a diversity of emotions and building their own identity. Therefore, it is a period of higher vulnerability for the development of internalizing problems. The present paper aims to study some constructs considered relevant to adolescents’ adjustment and/or internalizing disorders, emphasizing the role of well-being, emotional regulation and family environment. Therefore, this research aims to (1) test the mediating role of well-being in the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties, the family environment, and internalizing problems, and (2) understand the differences between adolescents with a higher and lower risk of presenting internalizing problems. In the study, 723 adolescents of both sexes (12–18 years old) from middle to high school completed self-report questionnaires. The results indicated that the mediating role of well-being was partially established between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems, explaining 31% of the variance in these problems. Well-being was also considered a partial mediator between family environment (cohesion and support and conflict) and internalizing problems, explaining 19 and 26% of the variance, respectively. Furthermore, the group with a higher risk of developing internalizing problems (n = 130) revealed higher levels of emotional regulation difficulties and family conflict. In contrast, this group reported less family cohesion and support and lower levels of well-being. The main results of the present study provide relevant data in the context of clinical practice. Important implications are also discussed for the design of psychopathology prevention programs and the promotion of global well-being with adolescents. Considering the limitations of the present study, such as the nonrandom sampling process and the reduced number of participants included in the clinical group, these results need to be deepened in future research in this area.

Introduction

Adolescence is a very important period in the individual’s development process and the consolidation of his or her autonomy, involving biological, psychological, cultural and psychosocial changes (Parsons, 2003). In this sense, adolescence is a vulnerable period for developing mental health problems (Costello et al., 2003). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2019) alerts that 20% of adolescents suffer from some mental disorder, and approximately half of them initiate it at approximately 14 years old. Studies carried out in several countries reveal that depression, anxiety, and eating disorders are the most prevalent mental disorders in the young population (e.g., Caldas de Almeida and Xavier, 2009; Roberts et al., 2009). These disorders are often grouped into “internalizing disorders,” as they are based on excessive impulse control and are manifested through various symptoms of anxiety, depression, social isolation and somatic complaints. Usually, they express toward the individual and not toward others, contrary to “externalizing disorders” (Cosgrove et al., 2011).

Some constructs are considered relevant in adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment, emphasizing the role that well-being can play in protecting against the development of internalizing disorders. Well-being is an innovative construct in this area, which still needs much research concerning other factors that are still more studied. Therefore, the present study intends to understand the role of well-being in the relationship of two important factors previously identified as relevant to the development of internalizing disorders (emotional regulation difficulties and family environment). This will allow, in the future, an understanding of how the promotion of well-being can contribute to the prevention of internalizing disorders and the improvement of adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment.

Subjective well-being encompasses three dimensions—social, psychological, and emotional—considered independent but interrelating and impacting mental health (Keyes and Waterman, 2003). Social well-being refers to one’s self-assessment of the quality of relationships with others and with the community in which they are inserted, focusing on the social functioning of the subjects from the point of view of commitment and social integration. Psychological well-being refers to positive self-assessment and self-acceptance and one’s continuous personal development process, setting goals and perceiving the meaning and purpose of life (Keyes, 2002). Emotional well-being encompasses the individual’s emotions and satisfaction evaluation concerning general and specific areas of their own life (Keyes and Waterman, 2003). Considering the difficulties associated with adolescence, it is important to explore and identify what contributes to adolescents’ subjective well-being of. Based on the tripartite model of the subjective well-being by Keyes (2002), a happy teenager is allegedly cognitively satisfied with life and experiences positive emotions (excitement, happiness) more frequently than negative emotions (nervousness, anger and anguish) (Martin and Huebner, 2007).

The identification of protective and risk factors associated with adolescents’ subjective well-being is extremely important to understand what influences the lives of young people (Cunsolo, 2017). Several studies show that low levels of psychological well-being, namely, with adolescents (Melo and Mota, 2014), are associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression (Derdikman-Eiron et al., 2011; Khazanov and Ruscio, 2016), with individuals with low levels of psychological well-being being even more likely to develop depression in the following 10 years (Wood and Joseph, 2010). The decline in general well-being at the beginning of adolescence may be due to feelings of stress that fall under the phase transition during this life stage, with a special focus on difficulties in the relationship between peers and in love relationships, the transition of basic education to secondary education, increased academic demands, and social pressure (Abela and Hankin, 2008). In contrast, the end of adolescence corresponds to a period of growing maturity and progression of the bylaws and a reduction of the anguish felt at the beginning of adolescence (Ge et al., 2006). In this sense, involving adolescents in positive psychology interventions has great potential as it can significantly enhance well-being and decrease symptoms of internalizing problems in both clinical and nonclinical groups (e.g., Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Ng and Ong, 2022).

The theoretical and empirical conceptualizations indicate that emotional regulation difficulties play a critical role in developing and maintaining depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescence (McLaughlin et al., 2011; Ahmed et al., 2015; Schäfer et al., 2016; Beveren et al., 2019). Emotional regulation refers to various conscious and unconscious processes that can be implemented at different stages of the emotion generating process, affecting emotions’ occurrence, intensity, duration, and expression (Gross, 2002; Thompson et al., 2008). Thus, it refers to a set of strategies that the individual uses to increase, maintain or decrease one or more components of a certain emotional response, namely, at the physiological, cognitive, behavioral, experiential and social levels (Gross, 2007). Adaptive emotional regulation involves selecting appropriate strategies and flexibility in their application, which is an indicator of psychological adjustment. Ineffective regulation leads to maladaptive emotional, cognitive and behavioral consequences, jeopardizing the individual’s ability to adapt to the situation (Cicchetti et al., 1995; Verzeletti et al., 2016). Poorly adaptive cognitive strategies for emotional regulation have been indicated as a risk factor for depression and anxiety (Aldao et al., 2010), increasing negative thoughts and compromising problem-solving. On the other hand, adaptive strategies conceive positive interpretations and perspectives, reducing the suffering generated by a negative event (Gross, 2007).

Some authors address emotional dysregulation as a construct with multiple dimensions encompassing deficits in several areas. These areas include awareness, understanding and acceptance of emotions, the ability to implement behaviors aimed at achieving goals and inhibiting impulsive behaviors when experiencing negative emotions, flexibility in the use of strategies aimed at modelling the intensity and/or duration of emotional responses to the detriment of their suppression, and acceptance of experiencing negative emotions that allow them to achieve personal goals (Gratz et al., 2006; Gratz and Gunderson, 2006). Gratz and Roemer (2004) claim that the difficulties in emotional regulation can be subdivided into a few dimensions, such as the nonacceptance of the emotional response, the lack of awareness and misunderstanding of the emotions, the difficulties in maintaining a behavior directed toward the goals, the difficulties in controlling impulses, limited access to emotional regulation strategies and, finally, lack of emotional clarity.

Research has highlighted that, based on a wide range of psychopathological conditions, there are deficits in emotional regulation (Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Chervonsky and Hunt, 2019), namely, in depressive and anxiety disorders (e.g., Masters et al., 2018). According to Turk et al. (2005), subjects with mood and anxiety disorders have a set of difficulties in managing their own emotions, which include a limited understanding of them, difficulties in identifying negative emotions and very negative reactions toward their emotional experience. Both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have consistently demonstrated the association between deficits in the capacity for emotional regulation and depression and anxiety in adolescents (e.g., Silk et al., 2003; Masters et al., 2018). Subjects with generalized anxiety disorder showed less emotional understanding and acceptance, less ability to regulate negative emotional experiences and higher levels of negative emotional reaction. In contrast, subjects with social phobia registered less expressiveness of positive emotions and greater difficulties describing them (Mennin et al., 2002).

The family has a prominent role, especially parents, as the main agents of socialization in developing emotional regulation capacity. In the family context, children learn to express emotions to understand the messages they transmit and their various regulatory processes (Larson et al., 2002). Additionally, the quality of family relationships is one of the factors that influence the mental health of individuals (e.g., Benetti, 2006; Herrenkohl et al., 2012; Luijten et al., 2021), so it is important to understand its role in the development and maintenance of internalizing disorders in adolescence. The environment perceived and interpreted by the various elements that make up the family—defined as the family environment—has a very significant influence on the emotional, physical, social and intellectual development and the behavior of its younger members. A positive family environment, based on effective cohesion between parents and children, support, trust, intimacy and empathetic and open communication, promotes psychological and behavioral adjustment in adolescents (López et al., 2008; Teodoro et al., 2009). Several studies have revealed that a family environment characterized by high levels of conflict and low levels of cohesion interferes negatively with the psychological adjustment and well-being of adolescents (Chang et al., 2001; Belardinelli et al., 2008; Sullivan and Miklowitz, 2010). Thus, there is a positive association between family conflict and psychopathology (Benetti, 2006; Morawska and Thompson, 2009; Teodoro et al., 2010; Herrenkohl et al., 2012), as well as between lower levels of mental disorders and higher levels of support and family cohesion (Paixão et al., 2018). Thus, previous investigations highlight the importance of positive characteristics in the family environment that can mitigate the appearance of mental disorder symptoms in adolescents, namely, a family environment with the presence of support and low levels of conflict and violence. For example, adolescents with a better quality of life also present significantly better communication with both parents, greater involvement in family activities, greater perception of support from parents, as well as a better family relationship (Guedes et al., 2022).

With specific regard to internalizing disorders, several studies have confirmed significant relationships with low levels of support (emotional and functional support received) and cohesion (emotional bond) between the various members of the family and with high levels of power differentiation, in which the older members of the family have much influence on decisions (hierarchy) and family conflict (Teodoro et al., 2014). For example, LaMontagne et al. (2022) recently found that adolescents with higher family conflict had more emotion regulation difficulties and more depressive symptoms. Of the various dimensions studied, family conflict has been the most strongly associated with internalizing problems (e.g., Francisco et al., 2016; Leusin et al., 2018).

The Current Study

Research on well-being and mental health in adolescence still needs to be investigated, especially compared to that on mental illness. Research should focus on internalizing problems, which, day by day, acquire space in society since they are not as visible as externalizing problems. To fill some of these gaps and contribute to the definition of key areas for intervention on promoting mental health and well-being in adolescents, the present study aims to understand the role of well-being in the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties, family environment, and internalizing problems among adolescents. The specific objectives are (a) to test the mediating effect of well-being on the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems; (b) to test the mediating effect of well-being on the relationship between the family environment (conflict, cohesion and support) and internalizing problems; and (c) to investigate the differences between adolescents with a higher and lower risk of presenting internalizing problems (i.e., clinical and nonclinical groups, respectively) regarding emotional regulation difficulties, family environment and well-being.

Based on the proposed goals and theoretical framework presented earlier, the following research hypotheses have been established:

-

H1. The relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems is mediated by the adolescents’ well-being.

-

H2. The relationship between the family environment and internalizing problems in adolescents is mediated by well-being.

-

H2.1. The relationship between conflict and internalizing problems is mediated by well-being;

-

H2.2. The relationship between cohesion and support and internalizing problems is mediated by well-being.

-

H3. There were significant differences between participants who presented a higher and lower risk of internalizing problems (i.e., clinical and nonclinical groups, respectively) in the studied variables.

-

H3.1. Adolescents in the clinical group present higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties (and each specific dimension);

-

H3.2. Adolescents in the clinical group present lower levels of well-being (and each specific dimension);

-

H3.3. Adolescents in the clinical group present higher levels of family conflict;

-

H3.4. Adolescents in the clinical group present lower levels of cohesion and support in the family.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A group of 723 adolescents (59.3% female) aged between 12 and 18 years (M = 14.70, SD = 1.735) participated in this study. Most of the participants (67.8%) attended the 3rd cycle of basic education (7–9th grade), and the rest attended secondary education (10–12th grade) in schools in the Greater Lisbon region (55.5%) and São Miguel Island – Azores archipelago (44.5%). Most participants (68.6%) reported never having psychological counselling, 21.2% had it in the past, and 8.6% had it currently.

Most participants came from an intact nuclear family (70.7%), 16.6% from a single-parent family, 6.1% from a stepfamily, and 5.8% from other family situations. The majority of the participants come from families of average socioeconomic level, taking into account the academic qualifications of their parents: Most of the participants’ mothers have higher education (42.1%), followed by less than compulsory schooling (32.3%) and middle schooling (25.6%); in turn, most of the fathers have less than compulsory schooling (42.5%), followed by higher education (32.1%) and middle schooling (25.4%).

Procedure

A cross-sectional design and a convenience sample were used. The Directorate-General for Innovation and Curricular Development of the Ministry of Education and the National Data Protection Commission approved the research project. After these approvals, nine public schools were approached through individual contacts (“snowball” method) and a formal authorization request to the Board of Directors of each educational establishment. Data collection was carried out in a classroom context after obtaining explicit permission from the parents and students’ informed consent (70% adherence rate). The students completed the protocols anonymously, with the presence of the subject teacher and one of the researchers, who clarified any doubts that occurred at the time. The total response time to the questionnaires was approximately 25–30 min, with younger students requiring more time than older students.

Measures

A Questionnaire on Personal and Sociodemographic Data was built within the scope of this study, aiming to collect information at the participant’s personal and sociodemographic level (e.g., sex, age, school year, area of residence).

The Portuguese version of the Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Coutinho et al., 2009) was used to assess the six domains that reflect difficulties in emotional regulation: nonacceptance of negative emotions; inability to engage in goal-driven behavior when experiencing negative emotions; difficulties in controlling impulsive behavior when experiencing negative emotions; limited access to emotional regulation strategies that are perceived to be effective; lack of emotional awareness; and lack of emotional clarity. It is a self-report scale consisting of 36 items, answered on a Likert-type scale with five points from 1 (1 being “almost never applies to me” to 5 being “applies almost always to me”). The scale has good internal consistency in its original version (α=0.93 on the global scale and between 0.80 and 0.89 on the subscales; Gratz and Roemer, 2004), and in the Portuguese version (α =0.92 on the global scale and above 0.75 in all subscales; Coutinho et al., 2009). In this study sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale is 0.93 and Omega index is 0.94, and between 0.74 and 0.90 in the subscales.

The Portuguese version of the Mental Health Continuum - Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes, 2009; Matos et al., 2010) assessed adolescents’ perceived degree of well-being. It is a self-report instrument consisting of 14 items, answered on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 being “never” to 5 being “every day”), whose sum corresponds to the level of global well-being, and which are divided into three dimensions: emotional well-being (3 items), social well-being (5 items) and psychological well-being (6 items). The Portuguese version in use has good levels of internal consistency (α = 0.90 on the global scale and between 0.80 and 0.85 on the subscales; Matos et al., 2010), very similar to the original version of Keyes (2009). In the study sample, the levels of internal consistency were equally high: total well-being α = 0.90 and ω = 0.90; between 0.80 and 0.85 for the subscales.

The Family Climate Inventory (Teodoro et al., 2009) is a self-report instrument consisting of 22 items that assess four dimensions of the family environment on a Likert scale (from 1 “completely disagree” to 5 “completely agree”): conflict (6 items related to the aggressive, critical and conflictual relationship between family members); hierarchy (6 items that analyze power differences within the family); support (5 items that measure the emotional and material support received by members of their family), and cohesion (5 items that define the bond between family members). All subscales have adequate levels of consistency in the original version (α =0.72 hierarchy, α =0.84 conflict, α =0.71 support and α =0.82 cohesion). The Portuguese version (Francisco, 2015) consists of only three dimensions (cohesion and support; hierarchy; conflict), as the results of the factor analysis do not match the original structure, with the cohesion and support items being grouped. In the present study, the hierarchy dimension was not used. In the study sample, both subscales (conflict, cohesion and support) have good levels of internal consistency (α = 0.88; ω = 0.89).

The Portuguese version of the self-report for adolescents aged 11–17 years old of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman et al., 1998; Fleitlich et al., 2005) was used to assess internalizing symptoms. The SDQ consists of 25 items divided into 5 scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. Each scale consists of 5 items, with three answer options (0 “not true”; 1 “somewhat true”; 2 “certainly true”). Goodman et al. (2010), in an in-depth psychometric study of the SDQ, proposed an alternative factor structure, with underlying theoretical justification, combining the subscale of emotional symptoms with the peer problems subscale in a single subscale, called internalizing disorders. This approach was adopted in the present study, as other researchers have also successfully used this structure (e.g., Dickey and Blumberg, 2004). According to Goodman et al. (1998, 2010), in studies with low-risk samples, “clinical cases” can be identified by a high score on one of the four difficulty scales. Since the sample of the present study is of low risk (community sample collected in a school context), individuals who showed a score considered high in one of the two scales of difficulties—above 7 in the Emotional Symptoms and above 6 in the Peer Problems’ scales (Goodman et al., 1998)—are part of the “clinical group” with internalizing problems. Regarding the instrument’s reliability, in the original version, the internal consistency coefficients of the Emotional Symptoms subscale was α =0.75, and α =0.63 (ω =0.63) in this study’s sample; for the Peer Problems subscale, they were α =0.44 and α =0.57 (ω =0.58), respectively. The new subscale “Internalizing Problems” presents higher alpha (0.69) and omega (0.68) coefficients than each subscale separately, reinforcing the appropriateness of using this strategy.

Data Analyses

The treatment and statistical analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 28) and R Studio. The relationship between continuous variables included in the mediation analyses was previously explored with the Pearson correlation coefficient. In simple mediation analyses, 1,000 bootstrap samples were used with a 95% confidence interval. In all mediation analyses, the overall well-being of adolescents was considered the mediating variable, and internalizing problems was the dependent variable. The Student’s t-test was used to test the significant differences in the clinical and nonclinical groups. Differences were considered statistically significant when the value of p was less than 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the correlations between the studied variables. Regarding the mediating role of well-being, the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems was partially mediated by well-being, with the indirect effect being small, although significant [β = 0.01, SE = 0.00, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.01, 0.02)], confirming H1. The mediation model was adequate and explained 31% of the variability in internalizing problems [F (2, 720) = 162.53, p < 0.001]. Particularly, it appears that there is a negative relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and well-being, which, in turn, has a negative relationship with internalizing problems. This leads to the conclusion that the more emotional regulation difficulties are felt, the less well-being and the more internalizing problems there will be. It is also worth mentioning the positive relationship between the emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems (Figure 1).

Table 1

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.DERS (total) | – | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Strategies | 0.895 *** | – | |||||||||||||

| 3. Non-acceptance | 0.755 *** | 0.671 *** | – | ||||||||||||

| 4. Awareness | 0.366 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.012 | – | |||||||||||

| 5. Impulse | 0.776 *** | 0.630 *** | 0.525 *** | 0.207 *** | – | ||||||||||

| 6. Goals | 0.710 *** | 0.623 *** | 0.474 *** | 0.006 | 0.483 *** | – | |||||||||

| 7. Clarity | 0.673 *** | 0.515 *** | 0.399 *** | 0.362 *** | 0.390 *** | 0.328 *** | – | ||||||||

| 8. Well-being (total) | −0.506 *** | −0.480 *** | −0.267 *** | −0.409 *** | −0.266 *** | −0.371 *** | −0.403 *** | – | |||||||

| 9. Emotional well-being | −0.519 *** | −0.516 *** | −0.296 *** | −0.334 *** | −0.295 *** | −0.321 *** | −0.422 *** | 0.807 *** | – | ||||||

| 10. Social well-being | −0.385 *** | −0.361 *** | −0.178 *** | −0.291 *** | −0.175 *** | −0.343 *** | −0.304 *** | 0.883 *** | 0.611 *** | – | |||||

| 11. Psychological well-being | −0.462 *** | −0.408 *** | −0.244 *** | −0.423 *** | −0.249 *** | −0.286 *** | −0.358 *** | 0.911 *** | 0.655 *** | 0.663 *** | – | ||||

| 12. Family Conflict | 0.333 *** | 0.322 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.112 ** | 0.290 *** | 0.185 *** | 0.279 *** | −0.212 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.137 *** | −0.185 *** | – | |||

| 13. Cohesion and Support | −0.262 *** | −0.236 *** | −0.063 | −0.271 *** | −0.200 *** | −0.130 ** | −0.221 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.331 *** | 0.286 *** | 0.338 *** | −0.537 *** | – | ||

| 14. Internalizing Problems | 0.536 *** | 0.562 *** | 0.423 *** | 0.141 *** | 0.398 *** | 0.331 *** | 0.376 *** | −0.418 *** | −0.450 *** | −0.313 *** | −0.357 *** | 0.366 *** | −0.261 *** | – | |

| 15. Sex | −0.192 *** | −0.169 *** | −0.079 * | −0.046 | −0.086 * | −0.209 *** | −0.223 *** | 0.031 | 0.181 *** | 0.187 *** | 0.094 * | −0.010 | 0.042 | −0.174 *** | – |

| 16. Age | −0.037 | −0.034 | −0.021 | 0.003 | −0.032 | 0.013 | 0.023 | −0.032 | −0.139 *** | −0.103 ** | −0.010 | 0.097 * | −0.113 ** | 0.081 * | −0.055 |

Correlations between all variables in study, in all participants (N = 723).

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale.

Figure 1

Illustration of the direct effects of emotional regulation difficulties for internalizing problems through the mediator well-being. The represented coefficients are standardized. Total effect (β = 0.07, p < 0.001). ***p < 0.001.

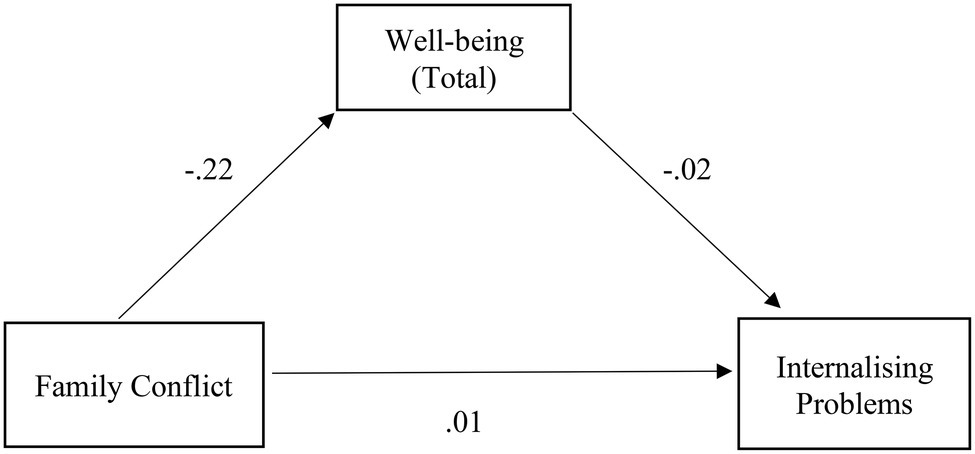

The relationship between family conflict and internalizing problems was also partially mediated by well-being, with a significant indirect effect, despite being small [β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.03, 0.07)], confirming H2.1. The mediation model was adequate and explained 26% of the variability in internalizing problems [F (2,720) = 123.42, p < 0.001]. Specifically, there is a negative relationship between conflict and well-being, which, in turn, has a negative relationship with internalizing problems, concluding that the greater the family conflict, the lesser the well-being, and the greater the internalizing problems. The positive relationship between conflict and internalizing problems should also be noted (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Illustration of the direct effects of the family conflict for internalizing problems through the mediator well-being. The represented coefficients are standardized. Total effect (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). ***p < 0.001.

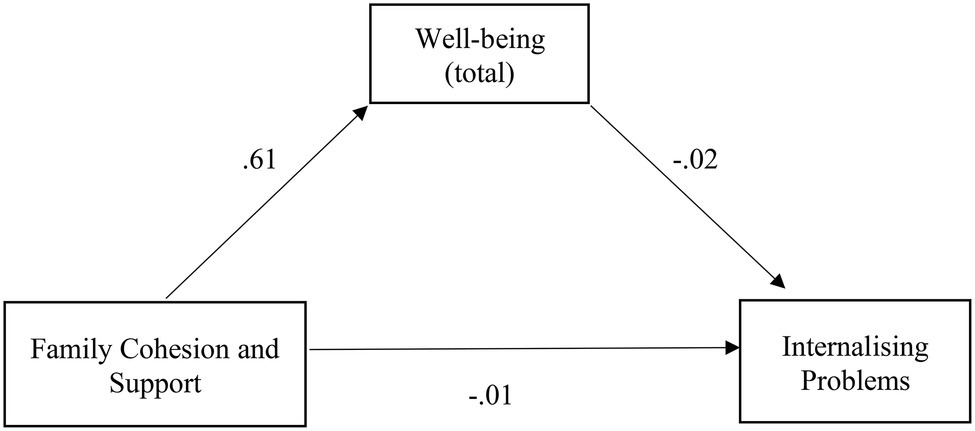

The relationship between family cohesion and support and internalizing problems was also partially mediated by well-being, with a small, albeit significant, indirect effect [β = −0.06, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.08, −0.04)], confirming H2.2. The mediation model was adequate and explained 19% of the variability in internalizing problems [F (2,720) = 83.99, p < 0.001]. There is a positive relationship between family cohesion and support and well-being, which, in turn, has a negative relationship with internalizing problems, concluding that the greater the family cohesion and support, the greater the well-being, and the less the internalizing problems. Additionally, of note is the negative relationship between cohesion and support and internalizing problems (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Illustration of the direct effects of family cohesion and support for internalizing problems through the mediator well-being. The represented coefficients are standardized. Total effect (β = −0.11, p < 0.001). ***p < 0.001.

Additionally, the mediation model was also tested with the three predictor variables. The model also proved to be adequate, explaining 31% of the variability in internalizing problems [F (4, 718) = 81.99, p < 0.001]. Specifically, the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems was mediated by well-being. An indirect effect was small but significant [β = 0.01, SE = 0.00, p = <0.001, CI 95% (0.00, 0.01)]; the relationship between family conflict and internalizing problems was mediated by well-being, and the indirect effect was also small but significant [β = −0.01, SE = 0.01, p = <0.001, 95% CI (−0.01, 0.00)]. Nonetheless, the relationship between familiar cohesion and support and internalizing problems was not mediated by well-being, and the indirect effect was not significant [β = − 0.01, SE = 0.01, p = >0.05, 95% CI (−0.02, 0.00)].

The correlations separated for the clinical and nonclinical groups (Table 2) showed different correlations between the studied variables among the clinical group. Significant correlations (although weaker than in the nonclinical group) were found between internalizing problems and well-being, as well as between internalizing problems and family conflict. However, the correlations of internalizing problems with difficulties in emotion regulation or cohesion and support were nonsignificant. For this reason, the previous models of mediation were tested specifically for the clinical group.

Table 2

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.DERS (total) | – | 0.864 *** | 0.708 *** | 0.342 *** | 0.747 *** | 0.688 *** | 0.632 *** | −0.455 *** | −0.452 *** | −0.337 *** | −0.422 *** | 0.259 *** | −0.232 *** | 0.425 *** | −0.145 *** | −0.013 |

| 2. Strategies | 0.896 *** | – | 0.610 *** | 0.109 * | 0.590 *** | 0.581 *** | 0.431 *** | −0.377 *** | −0.413 *** | −0.269 *** | −0.324 *** | 0.217 *** | −0.180 *** | 0.435 *** | −0.119 ** | −0.041 |

| 3. Non-acceptance | 0.775 *** | 0.666 *** | – | −0.050 | 0.431 *** | 0.441 *** | 0.339 *** | −0.176 *** | −0.200 *** | −0.102 * | −0.168 *** | 0.162 *** | −0.036 | 0.288 *** | −0.033 | −0.014 |

| 4. Awareness | 0.433 *** | 0.278 ** | 0.085 | – | −0.188 *** | −0.031 | 0.346 *** | −0.411 *** | −0.343 *** | −0.282 *** | −0.422 *** | 0.058 | −0.238 *** | 0.088 * | −0.034 | 0.032 |

| 5. Impulse | 0.752 *** | 0.541 *** | 0.581 *** | 0.209 * | – | 0.436 *** | 0.329 *** | −0.201 *** | −0.225 *** | −0.125 ** | −0.186 *** | 0.209 *** | −0.165 *** | 0.261 *** | −0.034 | −0.024 |

| 6. Goals | 0.666 *** | 0.583 *** | 0.363 *** | 0.024 | 0.434 *** | – | 0.270 *** | −0.312 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.299 *** | −0.234 *** | 0.127 ** | −0.083 | 0.253 *** | −0.168 *** | 0.002 |

| 7. Clarity | 0.645 *** | 0.510 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.355 *** | 0.349 *** | 0.300 ** | – | −0.347 *** | −0.396 *** | −0.256 *** | −0.294 *** | 0.218 *** | −0.194 *** | 0.279 *** | −0.229 *** | 0.052 |

| 8. Well-being (total) | −0.427 *** | −0.480 *** | −0.251 ** | −0.347 *** | −0.169 | −0.340 *** | −0.356 *** | – | . 776 *** | 0.868 *** | 0.905 *** | −0.157 *** | −0.328 *** | −0.326 *** | 0.016 | −0.034 |

| 9. Emotional well-being | −0.414 *** | −0.471 *** | −0.251 ** | −0.290 ** | −0.186 * | −0.284 ** | −0.286 ** | 0.826 *** | – | 0.554 *** | 0.636 *** | −0.175 *** | 0.290 *** | −0.338 *** | 0.115 ** | −0.116 ** |

| 10. Social well-being | −0.301 ** | −0.380 *** | −0.160 | −0.241 ** | −0.054 | −0.330 *** | −0.236 ** | 0.905 *** | 0.681 *** | – | 0.629 *** | −0.110 ** | 0.267 *** | −0.226 *** | 0.128 ** | −0.090 * |

| 11. Psychological well-being | −0.396 *** | −0.393 *** | −0.237 ** | −0.358 *** | −0.208 * | −0.244 ** | −0.374 *** | 0.907 *** | 0.631 *** | 0.686 *** | – | −0.136 ** | 0.293 *** | −0.283 *** | 0.049 | 0.008 |

| 12. Family Conflict | 0.250 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.177 | 0.151 | 0.240 ** | 0.099 | 0.172 | −0.098 | −0.141 | 0.034 | −0.101 | – | −0.480 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.015 | 0.106 * |

| 13. Cohesion and Support | −0.202 * | −0.221 * | −0.032 | −0.326 *** | −0.160 | −0.158 | −0.166 | 0.341 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.222 * | 0.369 *** | −0.634 *** | – | −0.250 *** | 0.042 | −0.133 ** |

| 14. internalizing Problems | 0.158 | 0.192 * | 0.253 ** | 0.101 | 0.233 ** | −0.064 | 0.097 | −0.201 * | −0.211 * | −0.140 | −0.164 | 0.224 * | −0.015 | – | −0.148 *** | 0.090 * |

| 15. Sex | −0.121 | −0.089 | −0.022 | −0.006 | −0.048 | −0.246 ** | −0.007 | −0.033 | 0.232 ** | 0.275 ** | 0.104 | 0.159 | −0.103 | 0.193 * | – | −0.048 |

| 16. Age | −0.138 | −0.070 | −0.071 | −0.143 | −0.100 | 0.088 | −0.146 | −0.099 | −0.237 ** | −0.133 | −0.035 | 0.071 | −0.026 | 0.093 | −0.075 | – |

Correlations between all variables in study, in participants included in clinical (n = 130) and nonclinical groups (n = 584).

Values for participants included in clinical group are in the lower-left triangle and values for participants included in nonclinical group are in the upper-right triangle. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale.

The results revealed that the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems was mediated by well-being, with a small yet significant, indirect effect [β = 0, SE = 0.01, p = <0.05, 95% CI (0.00, 0.01)]. The mediation model was inadequate, explaining only 5% of the variability in internalizing problems [F (2, 127) = 3.59, p < 0.05]. Nonetheless, a negative relationship exists between emotional regulation difficulties and well-being, negatively related to internalizing problems. This leads to the conclusion that the more emotional regulation difficulties are felt, the less well-being and the more internalizing problems there will be. It is also worth mentioning the positive relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Illustration of the direct effects of emotional regulation difficulties for internalizing problems through the mediator well-being in clinical group. The represented coefficients are standardized. Total effect (β = 0.01, p < 0.05). *p < 0.05.

Considering the family variables, the mediation model revealed that the relation between family conflict and internalizing problems was not successfully mediated by well-being (Figure 5), with the indirect effect not being significant [β = 0, SE = 0.02, p > 0.05, 95% CI (0.00, 0.01)]. The relationship between cohesion and support and internalizing problems was also not mediated by well-being (Figure 6) with a nonsignificant indirect effect [β = −0.01, SE = 0.02, p > 0.05, 95% CI (−0.03, 0.00)].

Figure 5

Illustration of the direct effects of the family conflict for internalizing problems through the mediator well-being in clinical group. The represented coefficients are standardized. Total effect (β = 0.01, p > 0.05).

Figure 6

Illustration of the direct effects of family cohesion and support for internalizing problems through the mediator well-being in clinical group. The represented coefficients are standardized. Total effect (β = 0.02, p > 0.05).

Table 3 presents the comparison results between the clinical and nonclinical groups for the study variables. All differences were considered statistically significant, confirming hypotheses H3.1, H3.2, H3.3, and H3.4. Specifically, the clinical group revealed higher values regarding total emotional regulation difficulties and their specific dimensions. The nonclinical group showed higher values of total well-being and its respective dimensions. For the family environment, the clinical group revealed higher conflict values and lower values of cohesion and support.

Table 3

| Clinical Group (n = 130) | Nonclinical Group (n = 584) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | df | t | |

| Strategies | 25.92 (8.24) | 16.54 (6.78) | 165.79 | −11.96 *** |

| Non-acceptance | 16.96 (6.38) | 11.92 (5.29) | 167.94 | −8.33 *** |

| Awareness | 16.73 (5.14) | 15.38 (4.73) | 700 | −2.90 ** |

| Impulses | 16.18 (5.99) | 11.68 (4.98) | 166.96 | −7.89 *** |

| Goals | 18.17 (4.84) | 14.46 (5.03) | 693 | −7.61 *** |

| Clarity | 14.15 (4.09) | 10.98 (3.87) | 695 | −8.23 *** |

| DERS (total) | 107.22 (25.10) | 80.90 (20.89) | 152.24 | −10.52 *** |

| Emotional well-being | 11.83 (3.69) | 14.57 (2.66) | 157.34 | 7.95 *** |

| Social well-being | 14.32 (6.33) | 17.95 (5.44) | 166.76 | 5.95 *** |

| Psychological well-being | 21.17 (6.95) | 25.38 (6.04) | 168.84 | 6.30 *** |

| Well-being (total) | 47.20 (15.01) | 57.97 (12.30) | 158.54 | 7.40 *** |

| Conflict | 15.54 (6.53) | 11.25 (5.06) | 158.14 | −6.90 *** |

| Cohesion and Support | 37.21 (8.46) | 40.35 (7.22) | 166.35 | 3.86 *** |

Comparison between clinical and nonclinical groups regarding emotional regulation difficulties, well-being, conflict, cohesion and support (n = 714).

df, degree of freedom; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale.

Discussion

The main objectives of this study were to understand the mediating effect of well-being on the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and the internalizing problems, and in the relationship between the family environment (conflict, cohesion and support) and internalizing problems. Moreover, it aimed to test the differences between adolescents with a higher and lower risk of internalizing problems (e.g., clinical and nonclinical groups, respectively) concerning emotional regulation difficulties, family environment and well-being.

The Mediating Role of Well-Being

The results of the present study revealed that well-being has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems. Considering the overall path of the direct effects obtained, the more emotional regulation difficulties are felt, the lower the well-being and the greater the Internalizing problems. Previous studies have already found that individuals who did not have difficulties in emotional regulation and used adaptive strategies had higher levels of well-being, manifesting happiness and satisfaction with life (e.g., Freire and Tavares, 2011). Likewise, greater difficulties in emotional regulation experienced by adolescents are also identified in the literature as being associated with Internalizing problems (Silk et al., 2003; Coutinho et al., 2009; Verzeletti et al., 2016) and with suicide ideation (Swee et al., 2020). Swee et al. (2020) identified belongingness— a relevant part of the well-being concept—as a mediator in the relationship between dysfunctional emotional regulation and suicidal ideation, thus demonstrating the need to study the mediating role of well-being and its importance in the psychological adjustment of adolescents. Since research on the mediating effect of well-being in this relationship is scarce, these results provide new knowledge for treating and understanding socio-emotional maladjustment in adolescents. Although emotional regulation difficulties are related to Internalizing problems, there may be a reduction in this impact by developing skills and strategies that promote global well-being in adolescents (Brenning et al., 2021).

Well-being also had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between the family environment and Internalizing problems. Considering the direct effects, higher levels of family conflict are associated with less well-being among adolescents, which, in turn, is associated with greater Internalizing problems. Likewise, high levels of cohesion and support within the family act as enhancers of well-being, which is then reflected in fewer Internalizing problems in adolescents. Previous studies have already shown that a family environment characterised by high levels of conflict and low levels of cohesion negatively interfere with the well-being, quality of life and psychological adjustment of adolescents (Belardinelli et al., 2008; Sullivan and Miklowitz, 2010; Cunsolo, 2017; Guedes et al., 2022), namely, in the rise of Internalizing problems (Teodoro et al., 2014; Paixão et al., 2018).

Considering only the clinical group, even though it was observed that well-being partially mediated the relationship between emotional regulation difficulties and internalizing problems, it was not as robust as when compared with the results described for the global sample. It was also noted that this group presented no significant mediation between the family environment (specifically family conflict and cohesion and support) and internalizing problems. However, these results can be explained by the small number of participants integrated into the clinical group, so future studies should further explore these possible effects. Nevertheless, the present study results allow a more in-depth understanding of the relationships between these constructs among adolescents in general, as the association found between the family environment (conflict and cohesion and support) and internalizing problems can change with the influence of well-being. In this sense, the promotion of the global well-being of adolescents will influence the relationship between family conflicts and the psychosocial adjustment, reducing the development of internalizing problems.

Risk Associated With Internalizing Problems

Adolescents at higher and lower risk of internalising problems showed significant differences in all studied variables. According to previous research, the greatest difficulties in emotional regulation reported by adolescents in the clinical group were expected. Studies have shown that individuals from the clinical population, namely, those with mood and anxiety disorders, had difficulties in managing their own emotions, as well as a limited understanding of them. They also presented difficulties in identifying negative emotions, controlling them, following goal-driven behaviors when they experience negative emotions, and presenting negative reactions toward their emotional experience (e.g., Turk et al., 2005; Coutinho et al., 2009).

Regarding the family environment, adolescents in the clinical group had higher levels of conflict and lower levels of family cohesion and support. Previous studies with adolescents with internalizing and externalizing problems reached the same conclusions (Teodoro et al., 2014), suggesting that the family environment is relevant to adolescents’ socioemotional adjustment. Given that a positive family environment assumes, as a basis, affective cohesion between parents and children, support, trust, empathic communication and openness, these can be considered protective factors of the children’s psychological adjustment. In this sense, a critical and aggressive relationship can be associated with high levels of conflict and, in turn, with adolescents’ internalizing problems (López et al., 2008).

Finally, the adolescents in the clinical group presented lower levels of well-being, which is in line with the results of previous studies that compared adolescents with and without anxiety and depression (Derdikman-Eiron et al., 2011; Luijten et al., 2021). In this regard, it is important to understand that, according to Keyes (2002), low levels of subjective well-being are associated with a less positive assessment of the overall satisfaction with one’s life (emotional well-being), with a more negative assessment of the quality of relationships with others and with the environment (social well-being), and even with lower personal acceptance and sense of life (psychological well-being). These are, in fact, aspects also frequently found in adolescent patients with internalizing problems (Khazanov and Ruscio, 2016), which reveals the relative overlap between the mental health and mental illness continuum.

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications for Future Studies

There is no prior research on the mediating effect of well-being on the analyzed constructs and internalizing problems, so these innovative results provide new knowledge regarding socioemotional (dis)adjustment in adolescents. Most of the current well-being research focuses on mediating constructs that influence well-being (e.g., Huang et al., 2018; Roemer and Harris, 2018; Yu and Luo, 2018) and not well-being as a mediator. However, according to the existing literature, this problem still needs greater in-depth research at the level of internalizing problems in adolescents (Zalk, 2020).

New implications are also drawn for the study of emotional regulation difficulties. They play a critical role in developing and maintaining internalizing problems in adolescents, making it extremely important to identify and understand the deficits that promote emotional dysregulation (Schäfer et al., 2016). Likewise, it is important to highlight the selection of appropriate strategies and flexibility in their application for adaptive emotional regulation since maladaptive emotional regulation strategies are indicated as risk factors for developing most mental disorders (Aldao et al., 2010).

Some limitations of the present study should be mentioned. First, the sampling was neither random nor representative of the Portuguese population, not allowing the generalization of the results. Second, using self-report instruments could have introduced some skewing on the answers regarding social desirability and randomness. Third, the small sample size of the clinical group and the way it was constituted. Actually, in this study, the clinical group refers to the group of participants who had a high score on one of the Emotional Symptoms and/or Relationship Problems with Colleagues subscales (cf. Goodman et al., 2010) and not in the sense that some type of clinical diagnosis was made or reported. Finally, the study’s cross-sectional nature does not allow us to make definitive statements regarding the directionality or causality of the associations.

Future studies should explore the influence of other factors contributing to the subjective well-being of adolescents, as well as the role of well-being as a mediator of the relationship between other variables and internalizing problems, such as the quality of family communication or coping strategies commonly used by adolescents to deal with the challenges of this developmental stage. In addition to longitudinal studies, which will allow verification of the stability of the studied relations, it will also be important to replicate this study comparing adolescents without and with a medical diagnosis of internalizing disorders. In this case, data collection should occur in institutions used by adolescents with difficulties (e.g., primary healthcare centers, hospitals), and not in the school community. Furthermore, it would be of great interest to address the results of the present study from a qualitative perspective, for example, including interviews with adolescents about the way they use different emotion regulation strategies in various situations, to better understand its relationships with the various dimensions of well-being and internalizing problems.

Implications for Practice

These results may be relevant to the intervention with adolescents, both in terms of preventing internalizing problems and promoting their well-being in psychotherapeutic intervention. In the context of clinical intervention, it will be relevant to promote more adaptive emotional regulation strategies to help conceptualize the difficulties and find additional viable alternatives for self-regulation. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated the effectiveness of existing interventions to improve emotion regulation, with improvements in psychopathology in youth (Moltrecht et al., 2021). At the same time, it is essential to promote belongingness to a group and create appropriate supportive relationships, including family relationships characterized by high cohesion and support and few conflicts. In addition, a recent study with Portuguese parents and adolescents suggested that mindful parenting interventions might be useful to foster adaptive emotion regulation in children by facilitating their self-compassion and psychological flexibility (Moreira and Canavarro, 2020). Interventions with both parents and adolescents can have important outcomes in reducing adolescent internalizing problems.

The results also provide relevant information for the design of psychopathology prevention programs in adolescents and the promotion of mental health and global well-being. For example, Johnstone et al. (2020) proved the efficacy of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression symptomatology in children and adolescents by promoting emotion regulation strategies. Positive psychology is also extremely relevant to assist in the understanding and development of high levels of psychological well-being in students, staff and school, considering that a positive school environment can help solve many problems (Duckworth et al., 2009; Borkar, 2016). Thus, a focus on different dimensions, such as emotional literacy, awareness of different emotions, emotional expression and differentiation, seems relevant to facilitate the adoption of adjusted attitudes and behaviors in intensely emotional situations. Furthermore, this will enhance the sense of belongingness to a group, promote interpersonal knowledge, provide problem-solving strategies, and promote positive family interactions.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by CRC-W: Católica Research Centre for Psychological, Family and Social Wellbeing, from Universidade Católica Portuguesa. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

BR designed the study, collected, managed and analyzed data, and wrote the draft of this manuscript. RF designed the study, supervised data collection and data analyzes, reviewed the draft, and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students and their teachers and principals, from the nine schools that made this study possible, by participating in the data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Abela J. R. Z. Hankin B. L. (2008). Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents.New York: Guilford Press.

2

Ahmed S. P. Bittencourt-Hewitt A. Sebastian C. L. (2015). Neurocognitive bases of emotion regulation development in adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci.15, 11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.07.006

3

Aldao A. Nolen-Hoeksema S. Schweizer S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.30, 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

4

Belardinelli C. Hatch J. P. Olvera R. L. Fonseca M. Caetano S. C. Nicoletti M. et al . (2008). Family environment patterns in families with bipolar children. J. Affect. Disord.107, 299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.011

5

Benetti S. P. C. (2006). Conflito conjugal: Impacto no desenvolvimento psicológico da criança e do adolescente [marital conflict: impact on the psychological development of children and adolescents]. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica19, 261–268. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722006000200012

6

Beveren M.-L. V. Goossens L. Volkaert B. Grassmann C. Wante L. Vandeweghe L. et al . (2019). How do I feel right now? Emotional awareness, emotion regulation, and depressive symptoms in youth. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry28, 389–398. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1203-3

7

Borkar V. N. (2016). Positive school climate and positive education: impact on students well-being. Ind. J. Health Well Being7, 861–862.

8

Brenning K. Soenens B. Vansteenkiste M. Clercq B. D. Antrop I. (2021). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic risk factor for (non)clinical adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: investigating the intervening role of psychological need experiences. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev.53, 124–136. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01107-0

9

Caldas de Almeida J. M. Xavier M. (2009). Estudo epidemiológico nacional de saúde mental: Primeiro relatório [National epidemiological study of mental health: First report].Lisbon: Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

10

Chang K. D. Blasey C. Ketter T. A. Steiner H. (2001). Family environment of children and adolescents with bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord.3, 73–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030205.x

11

Chervonsky E. Hunt C. (2019). Emotion regulation, mental health, and social wellbeing in a young adolescent sample: a concurrent and longitudinal investigation. Emotion19, 270–282. doi: 10.1037/emo0000432

12

Cicchetti D. Ackerman B. P. Izard (1995). Emotions and emotion regulation in developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol.7, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006301

13

Cosgrove V. E. Rhee S. H. Gelhorn H. L. Boeldt D. Corley R. C. Ehringer M. A. et al . (2011). Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol.39, 109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8

14

Costello E. J. Mustillo S. Erkanli A. Keeler G. Angold A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry60, 837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837

15

Coutinho J. Ribeiro E. Ferreirinha R. Dias P. (2009). Versão Portuguesa da Escala de Dificuldades de Regulação Emocional e sua relação com os sintomas psicopatológicos [Portuguese version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms]. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica37, 145–151.

16

Cunsolo S. (2017). Subjective wellbeing during adolescence: A literature review on key factors relating to adolescent’s subjective wellbeing and education outcomes. Studi sulla Formazione20, 81–94. doi: 10.13128/Studi_Formaz-20941

17

Derdikman-Eiron R. Indredavik M. S. Bratberg G. H. Taraldsen G. Bkken I. J. Colton M. (2011). Gender differences in subjective well-being, self-esteem and psychosocial function in adolescents with symptoms of anxiety and depression: findings from the Nord-Trondelag health study. Scand. J. Psychol.52, 261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00859.x

18

Dickey W. C. Blumberg S. J. (2004). Revisiting the factor structure of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire: United States, 2001. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry43, 1159–1167. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000132808.36708.a9

19

Duckworth A. L. Quinn P. D. Seligman M. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Posit. Psychol.4, 540–547. doi: 10.1080/17439760903157232

20

Fleitlich B. Loureiro M. J. Fonseca A. Gaspar M. F. (2005). Versão portuguesa do Questionário de capacidades e dificuldades (SDQ) [Portuguese version of the Strengths and difficulties questionnaire - research version].Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra.

21

Francisco R. (2015). Versão portuguesa do Inventário de Clima Familiar - versão para investigação [Portuguese version of the Family Climate Inventory - research version].Lisbon: Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

22

Francisco R. Loios S. Pedro M. (2016). Family functioning and adolescent psychological maladjustment: the mediating role of coping strategies. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev.47, 759–770. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0609-0

23

Freire T. Tavares D. (2011). Influência da autoestima, da regulação emocional e do género no bem-estar subjetivo e psicológico de adolescentes [influence of self-esteem, emotional regulation and gender in the subjective and psychological well-being of adolescents]. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica38, 184–188. doi: 10.1590/S0101-60832011000500003

24

Ge X. Natsuaki M. N. Conger R. D. (2006). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and stressful life events among male and female adolescents in divorced and nondivorced families. Dev. Psychopathol.18, 253–273. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060147

25

Goodman A. Lamping D. L. Ploubidis G. B. (2010). When to use broader internalizing and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol.38, 1179–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x

26

Goodman R. Meltzer H. Bailey V. (1998). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry7, 125–130. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057

27

Gratz K. L. Gunderson J. G. (2006). Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav. Ther.37, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002

28

Gratz K. L. Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess.26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

29

Gratz K. M. Rosenthal M. Z. Tull M. T. Lejuez C. W. (2006). An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol.115, 850–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.850

30

Gross J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology36, 281–291. doi: 10.1017/s0048577201393198

31

Gross J. J. (2007). Handbook of Emotion Regulation.New York: The Guilford Press.

32

Guedes F. B. Cerqueira A. Gaspar S. Gaspar T. Moreno C. Gaspar de Matos M. (2022). Family environment and Portuguese adolescents: impact on quality of life and well-being. Children9:200. doi: 10.3390/children9020200

33

Herrenkohl T. I. Lee J. O. Kosterman R. Hawkins J. D. (2012). Family influences related to adult substance use and mental health problems: a developmental analysis of child and adolescent predictors. J. Adolesc. Health51, 129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.003

34

Huang J. Shi H. Liu W. (2018). Emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: altruistic behavior as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Pers.46, 749–758. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6762

35

Johnstone K. M. Middleton T. Kemps E. (2020). A pilot investigation of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression symptomology in children: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychol.76, 1193–1216. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22926

36

Keyes C. (2002). The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Res.43, 207–222. doi: 10.2307/3090197

37

Keyes C. (2009). “The nature and importance of positive mental health in America’s adolescents,” in Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools.1stEdn. eds. GilmanR.HuerbnerE. S.FurlongM. J. (London: Routledge), 9–23.

38

Keyes C. Waterman M. (2003). “Dimensions of well-being and mental health in adulthood,” in Well-Being: Positive Development Across the Life Course. eds. BornsteinM.DavidsonL.KeyesC.MooreK. (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

39

Khazanov G. K. Ruscio A. M. (2016). Is low positive emotionality a specific risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull.142, 991–1015. doi: 10.1037/bul0000059

40

LaMontagne L. G. Diehl D. C. Doty J. L. Smith S. (2022). The mediation of family context and youth depressive symptoms by adolescent emotion regulation. Youth Soc. doi: 10.1177/0044118X211067266

41

Larson R. Moneta G. Richards M. Wilson S. (2002). Continuity, stability and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Dev.4, 1151–1165. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464

42

Leusin J. F. Petrucci G. W. Borsa J. C. (2018). Clima familiar e os problemas emocionais e comportamentais na infância [family environment and emotional and behavioral problems in childhood]. Revista da Sociedade de Psicoterapias Analíticas Grupais do Estado de São Paulo19, 49–61.

43

López E. Pérez S. Ochoa G. Ruiz D. (2008). Clima familiar, Clima escolar y Satisfacción con la vida en adolescents [family environment, school environment and satisfaction with life in teenagers]. Revista Mexicana de Psicología25, 119–128.

44

Luijten C. C. van de Bongardt D. Jongerling J. Nieboer A. P. (2021). Associations between adolescents’ internalizing problems and well-being: is there a buffering role of boys’ and girls’ relationships with their mothers and fathers?BMC Public Health21:1871. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11920-4

45

Martin K. M. Huebner E. S. (2007). Peer victimization and prosocial experiences and emotional well-being of middle school students. Psychol. Sch.44, 199–208. doi: 10.1002/pits.20216

46

Masters M. R. Zimmer-Gembeck M. Farrell L. J. (2018). Transactional associations between adolescents’ emotion dysregulation and symptoms of social anxiety and depression: a longitudinal study. J. Early Adolesc.39, 1085–1109. doi: 10.1177/0272431618806053

47

Matos A. P. André R. S. Cherpe S. Rodrigues D. Figueira C. Pinto A. M. (2010). Estudo Psicométrico preliminar da mental health continuum – short form – for youth numa amostra de adolescentes portugueses [preliminary psychometric study of the mental health continuum – short form – for youth in a sample of Portuguese adolescents]. Psychologica53, 131–156. doi: 10.14195/1647-8606_53_7

48

McLaughlin K. A. Hatzenbuehler M. L. Mennin D. S. Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2011). Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: a prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther.49, 544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003

49

Melo O. S. Mota C. P. (2014). Protótipos de vinculação amorosa: Bem-estar psicológico e psicopatologia em jovens de famílias intactas e divorciadas [prototypes of loving attachment: psychological wellbeing and psychopathology in young people from intact and divorced families]. Análise Psicológica3, 307–322. doi: 10.14417/ap.718

50

Mennin D. S. Heimberg R. G. Turk C. L. Fresco D. M. (2002). Applying an emotion regulation framework to integrative approaches to generalized anxiety disorder. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract.9, 85–90. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.85

51

Moltrecht B. Deighton J. Patalay P. Edbrooke-Childs J. (2021). Effectiveness of current psychological interventions to improve emotion regulation in youth: a meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry30, 829–848. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01498-4

52

Morawska A. Thompson E. (2009). Parent problem checklist: measure of parent conflict. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry43, 260–269. doi: 10.1080/00048670802653281

53

Moreira H. Canavarro M. C. (2020). Mindful parenting is associated with adolescents’ difficulties in emotion regulation through adolescents’ psychological inflexibility and self-compassion. J. Youth Adolesc.49, 192–211. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01133-9

54

Ng W. Ong K. R. (2022). Using positive psychological interventions to improve well-being: are they effective across cultures, for clinical and non-clinical samples?J. Contemp. Psychother.52, 45–53. doi: 10.1007/s10879-021-09513-8

55

Paixão R. F. Patias N. D. Dell’Aglio D. D. (2018). Relações entre violência, clima familiar e transtornos mentais na adolescência [relationships between violence, family environment and mental disorders in adolescence]. Gerais: Revista Interinstitucional de Psicologia11, 109–122.

56

Parsons C. (2003). Caring for adolescents and families in crisis. Nurs. Clin. N. Am.38, 111–122. doi: 10.1016/S0029-6465(02)00071-3

57

Roberts R. E. Roberts C. R. Chan W. (2009). One-year incidence of psychiatric disorders and associated risk factors among adolescents in the community. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry50, 405–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01969.x

58

Roemer A. Harris C. (2018). Perceived organizational support and well-being: the role of psychological capital as a mediator. SA J. Ind. Psychol.44, 1–11. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1539

59

Schäfer J. Ö. Naumann E. Holmes E. A. Tuschen-Caffier B. Samson A. C. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: a meta-analytic review. J. Youth Adolesc.46, 261–276. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0

60

Silk J. S. Steinberg L. Morris A. (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Dev.74, 1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x

61

Sin N. L. Lyubomirsky S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol.65, 467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593

62

Sullivan A. E. Miklowitz D. J. (2010). Family functioning among adolescents with bipolar disorder. Family Psychol.24, 60–67. doi: 10.1037/a0018183

63

Swee G. Shochet I. Cockshaw W. Hides L. (2020). Emotion regulation as a risk factor for suicide ideation among adolescents and young adults: the mediating role of belongingness. J. Youth Adolesc.49, 2265–2274. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01301-2

64

Teodoro M. Allgayer M. Land B. (2009). Desenvolvimento e validade fatorial do Inventário do Clima familiar (ICF) Para adolescentes [development and factorial validity of the family climate inventory for adolescents]. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática11, 27–39.

65

Teodoro M. Cardoso B. M. Freitas A. C. H. (2010). Afetividade e conflito familiar e sua relação com a depressão em crianças e adolescentes [affectivity and family conflict and its relationship with depression in children and adolescents]. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica23, 324–333. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722010000200015

66

Teodoro M. Hess A. Saraiva L. Cardoso B. (2014). Problemas emocionais e de comportamento e clima familiar em adolescentes e seus pais [emotional and behavioral problems and family climate in adolescents and their parents]. Psico45, 168–175. doi: 10.15448/1980-8623.2014.2.13172

67

Thompson R. A. Lewis M. D. Calkins S. D. (2008). Reassessing emotion regulation. Child Dev. Perspect.2, 124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00054.x

68

Turk C. L. Heimberg R. G. Luterek J. A. Mennin D. S. Fresco D. M. (2005). Emotion dysregulation in generalized anxiety disorder: a comparison with social anxiety disorder. Cogn. Ther. Res.29, 89–106. doi: 10.1007/s10608-005-1651-1

69

Verzeletti C. Zammuner V. L. Galli C. Agnoli S. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial well-being in adolescence. Cogent Psychol.3:1199294. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2016.1199294

70

Wood A. Joseph S. (2010). The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: a ten year cohort study. J. Affect. Disord.122, 213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.032

71

World Health Organization (2019). Child and adolescent mental health. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/child_adolescent/en/ (Accessed February 10, 2022).

72

Yu Y. Luo J. (2018). Dispositional optimism and well-being in college students: self-efficacy as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Pers.46, 783–792. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6746

73

Zalk N. V. (2020). The development of internalizing behaviors in early adolescence: introduction to the special issue. J. Early Adolesc.40, 1281–1290. doi: 10.1177/0272431620919174

Summary

Keywords

emotional regulation difficulties, family environment, adolescence, well-being, internalizing problems

Citation

Raposo B and Francisco R (2022) Emotional (dys)Regulation and Family Environment in (non)Clinical Adolescents’ Internalizing Problems: The Mediating Role of Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 13:703762. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.703762

Received

30 April 2021

Accepted

14 March 2022

Published

31 March 2022

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

José Manuel García-Fernández, University of Alicante, Spain

Reviewed by

Sreekanth Kumar Mallineni, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia; Iván Fernández Martínez, Universidad Internacional de Valencia, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Raposo and Francisco.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rita Francisco, ritafrancisco@ucp.pt

This article was submitted to Psychology for Clinical Settings, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.