- 1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Geneva University (UNIGE), Geneva, Switzerland

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatry Service (SPA), University Hospitals of Geneva (HUG), Geneva, Switzerland

- 3Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health (DINOGMI), Section of Psychiatry, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

- 4IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy

- 5Department of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Sensory Organs, Suicide Prevention Center, Sant'Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

The current situation in Ukraine and mental health consequences

The Russian invasion of Ukraine started on February 24, 2022, and is still ongoing, causing the largest civilian refugee crisis in Europe since World War II, and the first of its kind since the Yugoslav war in the 1990's. At the time of writing, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that more than 14 million people had either left the country or been displaced internally [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2022a,b]. The most vulnerable population segments among refugees are children (more than half of all Ukrainian children have been forced to leave their homes), women, elder persons, and those who are ill and unable to participate in the military response (Dobson, 2022; Hodes, 2022). These individuals are at a very high risk of developing a wide range of mental health disorders, including severe anxiety and depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicidal ideation/behavior with likely long-term sequelae (Charlson et al., 2019; Javanbakht, 2022; Elvevåg and DeLisi, 2022). Johnson et al. (2022), conducting face-to-face interviews while the war was still confined to the Donbass and Kharkiv regions, found widespread direct exposure to conflict-related traumatic events (65%) among internally displaced people (IDP) leading to an elevated prevalence of PTSD symptoms across all socio-demographic groups. Similar results were found by Roberts et al. (2019) who used a cross-sectional survey on IDP during the early stages of the conflict and found prevalences of PTSD, depression, and anxiety of 32, 22, and 17%, respectively. Cheung et al. (2019) noted that more than half the IDP in Ukraine were at risk of somatic distress (55%). All this must be seen in the context of a public health care system that is under increased pressure due to the ongoing Russian targeting of residential areas and crucial civilian infrastructures. This had already created a considerable treatment gap in 2017 when 74% of individuals who had either screened positive with PTSD, depression, or anxiety or self-reported a problem were unable to receive Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) (Roberts et al., 2019).

Resources available to refugees and health care professionals

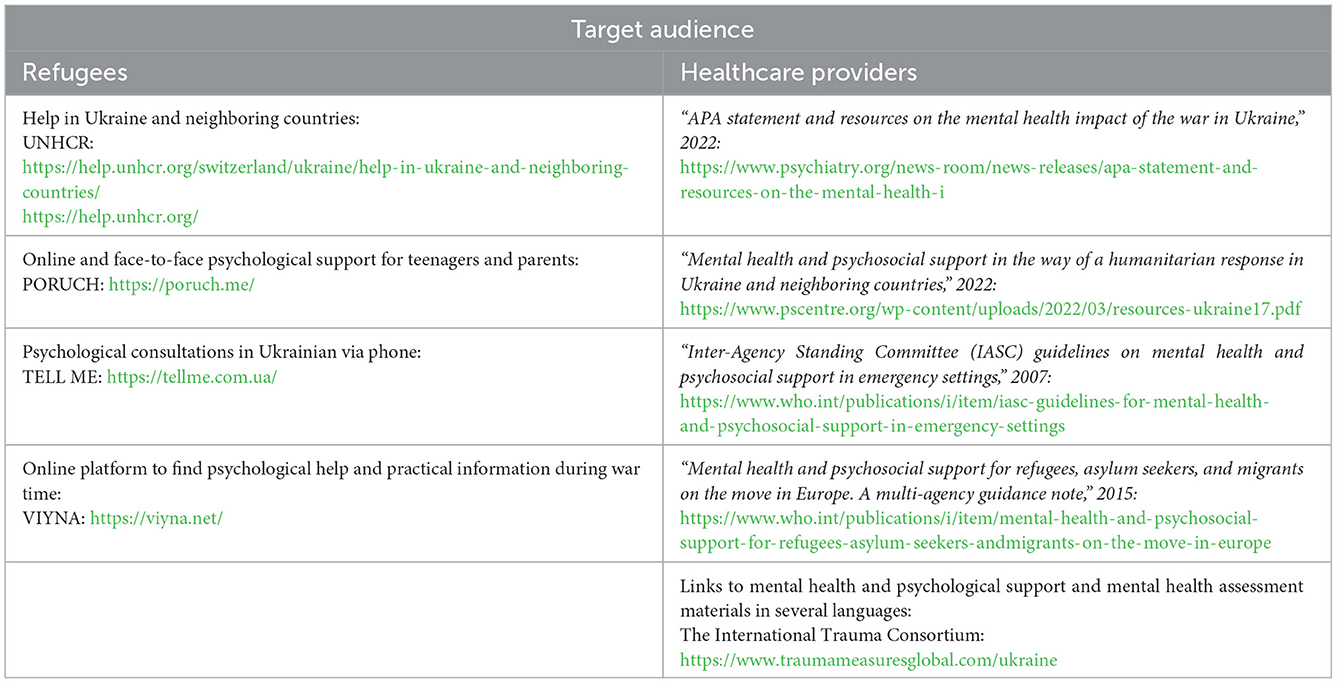

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) pointed out that specific attention should be paid to the presence and intensity of signs indicative of psychiatric/psychological suffering in refugee populations, irrespective of whether they pertain to an already established pathology or prodrome [American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2022]. Therefore, comprehensive MHPSS programs for refugees that integrate somatic health concerns, social support, education, and targeted psychiatric/psychological interventions are urgently needed (Murphy et al., 2022). A broad range of resources can be used to address and alleviate the war's impact on mental health from a primarily pragmatic and easy-access point of view, including various types of psychological and psychotherapeutic strategies that can be applied to these populations (Shevlin et al., 2022; Uphoff et al., 2020). In Table 1 we have assembled (according to our team research consensus) a summary of some of the resources available to refugees and healthcare providers, which we found useful and consider pertinent, including guidelines for various emergency care situations and refugees.

Table 1. Examples of resources available to refugees and healthcare professionals to provide mental health support (non-exhaustive).

War refugees dedicated interventions and their effectiveness

Before any intervention can take place, an initial screening needs to be conducted where the immediate focus should be placed on questions to identify serious mental illness and risk for suicide before proceeding with a more formal mental health assessment once rapport has been established [Hollifield et al., 2012; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2022]. Women should also be screened for possible sexual abuse to guide interventions (Ekblad et al., 2007).

About conflict settings, in general, there is little guidance on how to deliver mental health interventions that are suitable (Slobodin and de Jong, 2015; Gaffey et al., 2021), especially during the active phase of war (Martsenkovskyi et al., 2022). Acarturk et al. (2022), assessing the effectiveness of a WHO self-help psychological intervention for preventing mental disorders among Syrian refugees in Turkey, found that although the self-help approach was not effective immediately post-intervention participants enrolled in the self-help program were significantly less likely to have any mental disorders and also saw beneficial effects in terms of depression and quality of life at the six-month follow-up compared to those in the enhanced care as usual group. Based on a meta-analysis of interventions designed specifically for traumatized asylum seekers and refugees, Slobodin and de Jong (2015) concluded that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and narrative exposure therapy (NET) were two evidence-based strategies that proved effective and suitable for refugee populations. They did not find sufficient data to confirm or refute alternative approaches, although there appears to be some preliminary evidence that a combination of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and stabilization provided positive outcomes. In a similar meta-analysis, Turrini et al. (2019) also found that CBT was effective at reducing PTSD and anxiety while EMDR was effective with depressive symptoms. In contrast, narrative exposure therapy (NET) proved ineffective. They authors further conclude that most studies were conducted in adults or mixed populations of adults and children, which makes the efficacy of these psychosocial interventions in children uncertain.

Concerning refugees, and refugee vulnerable people in particular, data on effective psychotherapeutic interventions are extremely limited (Peltonen and Punamäki, 2010; Pacione et al., 2013). There are some smaller studies that have shown that both Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) and a version specifically adapted to your (KidNET) have been used successfully to treat refugee youth suffering from symptoms of PTSD (Schaal et al., 2009; Robjant and Fazel, 2010; Ruf et al., 2010) and more detailed studies are underway (Schwartz et al., 2022; Velu et al., 2022).

Clearly, defining a single set of universally valid interventions appropriate in all cultural contexts is an impossibility as interventions are typically only culturally appropriate for those settings in which they have been developed (Elvevåg and DeLisi, 2022; Gaffey et al., 2021). Globally, it seems that there is no a real consensus regarding the efficiency of these interventions, particularly for psychological/psychotherapy strategies.

In this opinion letter, we intend to describe our initial experience in caring for refugees from the war in Ukraine using a meaning-based psychotherapy approach.

Caring for Ukrainian refugees: From demoralization to meaning-centered psychotherapy

At our mental health service we focused on a conceptual model that combines the two psychological constructs of demoralization and meaning in life (MiL), which are closely linked (loss of MiL being a sub-component of demoralization) (Clarke and Kissane, 2002).

Of note, these constructs were conceived specifically for populations who suffered a dramatic fracture that divided their existence into a “before” and “after” in wartime contexts concerning civilian refugees, concentration camp survivors, soldiers, and veterans. Demoralization was first described in American soldiers confronted by an unfamiliar disease (Frank, 1974), and the attribution/preservation of MiL, even if relative and transient, was first studied in concentration camp survivors as a possible key factor for survival while being exposed to unavoidable and incomprehensible atrocities (Frankl, 1959). After these initial conceptualizations, various models of demoralization and MiL have been proposed for the purpose of being used in clinical practice as risk and resilience factors, respectively, in heterogeneous populations, without or with a psychiatric diagnosis, e.g., in perpective of recovery's encouragement or to refine the assessment of suicidal risk (which represents a common final path for many forms of suffering: psychic, somatic, and psychosomatic; it is particularly in this latter domain where these two constructs have been researched and applied most widely) (Huguelet et al., 2016; Costanza et al., 2020a,b).

As part of our institutional mental health support activities, we organized periodic therapeutic sessions with Ukrainian women, who, along with their children, had arrived in Italy as refugees. The therapeutic sessions were conducted in groups with ten participants on average and accompanied by the same interpreter. A full cycle includes four weekly sessions (we chose this 1-month duration as refugees arriving in Italy typically only stay for one month in their first location before being transferred to another, more long term site). Each session within a cycle was co-led by the same psychiatrist and psychologist.

Although in this population a clear diagnosis of depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition (DSM-V) is often difficult to establish, what do emerge prominently are the themes representing the five sub-components of demoralization, namely loss of MiL, hopelessness or disheartenment, helplessness, sense of failure, and dysphoria. Hence, since loss of MiL is a crucial sub-component of demoralization, we conducted these group interventions inspired by meaning-centered therapy.

The theory and rationale underlying the psychotherapeutic model used in our sessions are based on meaning-centered coping strategies. In the late 1990's, Folkman added meaning-centered coping techniques to the original emotion- or problem-based coping strategies of Lazarus by extending the resolution pathway to include the impacts of resources experienced by individuals as they encountered unfavorable outcomes (Folkman, 1997). Meaning-focused coping was defined as “appraisal-based coping in which the person draws on his or her beliefs (e.g., religious, spiritual, or justice-related), values, and existential goals (e.g., purpose in life, guiding principles) to motivate and sustain coping during a difficult time” (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). Severe trauma can represent a kind of ontological assault in which some of the most fundamental assumptions held by the individuals (mentioned above), including that the world is benevolent and meaningful and the self is worthy (Janoff-Bulman, 1992), are shattered, potentially leading to the dissolution of one's personal biography, self-identity, and perceived world. The post-traumatic crisis can imply a challenge to maintaining MiL, with the acquisition of a peculiar depressive disposition (Befindlichkeit) well-captured by the dimensions of demoralization (Janoff-Bulman, 1992).

Interventions were transcribed verbatim in medical dossiers to be able to extract the primary themes for subsequent qualitative analysis. These included horrific accounts and images but also particular wording to describe how individuals had attempted to survive those events. Thus far, the MiL-related coping theme that emerged most strongly and most frequently was the “absolute need” to safeguard the physical and mental health of children (even in women who did not have children but who cared for those of others or orphans), according with previous observations (Costanza et al., 2020a,b). Our primary objective – in line with the link between MiL and demoralization – was a diminution of demoralization by trying to enable refugees to find subjective and effective meaning in situations where the irrational seems to prevail. Indeed, toward the end of a therapeutic session cycle, most participants would express a sense of relief and decreased levels of demoralization. This is in good agreement with a recent review on suicidal patients (community-dwellers or affected by psychiatric illnesses and severe oncological and neurological diseases) in which meaning-centered coping techniques have been postulated as useful strategies to alleviate demoralization (Costanza et al., 2022).

Agreeing with the primary instance of these mothers, we would expect that the beneficial effects this therapeutic approach had on adult refugees could help to mitigate the impact the war has had on their children (Bürgin et al., 2022; Editorial, 2022) who have been exposed to something unexpected, unpredictable, and utterly cruel.

Conclusion and perspectives

In this opinion letter, we have provided a short overview of the available interventions for treating war refugees and their effectiveness. From a psychological/psychotherapeutic point of view, we have chosen a specific model from the extensive arsenal of possible approaches that meet APA and MHPSS recommendations for supporting refugees. We then briefly described our experience with this model, which is based on a conceptua framework that combines the two psychological constructs of demoralization and MiL.

Mental health and psychosocial support interventions are crucial as refugees are at a very high risk of developing a wide range of mental health disorders, including PTSD, severe anxiety/depressive disorders, and suicidal ideation/behavior with likely long-term sequelae. Given the magnitude of the current crisis, this requires international support from policy makers and from the institutions in the various hosting countries. We need to encourage both interpersonal support by facilitating links with compatriots in similar situations to share their concerns and experiences in their own language and host countries need to facilitate their social integration by providing language courses, opening schools to refugee children, and allowing them to take on temporary employment, etc (Kaufman et al., 2022; Schwartz et al., 2022).

Finally, while this opinion letter may be brief and somewhat anecdotal and our psychotherapeutic approach is relatively novel and perhaps even unorthodox, it has show promising results although these should be considered preliminary. We expect it to become more common once we are able to provide a more thorough analysis of the outcomes. We believe that our experience is based on solid foundations and can offer a generalizable therapeutic perspective. With the purpose of searching for and redirecting toward a personal and effective meaning where a meaning is not there and the absurd stands out. This work is necessarily in progress and must be continued.

Author contributions

AC: conception, data collection, and composition of the initial draft. AAm: conception and major contributions to the intermediate revision of the manuscript. AAg and LM: contributions to the intermediate revision of the manuscript. PH, GS, MP, and MA: supervision and final draft revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Geneva.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants for spending their time in difficult conditions and sharing their experiences.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acarturk, C., Uygun, E., Ilkkursun, Z., Carswell, K., Tedeschi, F., Batu, M., et al. (2022). Effectiveness of a WHO self-help psychological intervention for preventing mental disorders among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry 21, 88–95. doi: 10.1002/wps.20939

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Statement Resources on the Mental Health Impact of the War in Ukraine. (2022). Available online at: https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-statement-and-resources-on-the-mental-health-impact-of-the-war-in-ukraine (accessed August 08, 2022).

Bürgin D. Anagnostopoulos D. Vitiello B. Sukale T. Schmid M. Board Policy Division of ESCAPl. Impact of war forced displacement on children's mental health-multilevel, needs-oriented, trauma-informed approaches. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. (2022) 31, 845–853. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-01974-z.

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC). Guidance for Mental Health Screening during the Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arrived Refugees. (2022). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/mental-health-screening-guidelines.html (accessed November 27, 2022).

Charlson, F., van Ommeren, M., Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H., and Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 394, 240–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

Cheung, A., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., Karachevsky, A., Kharchenko, N., Shpiker, M., et al. (2019). Patterns of somatic distress among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Soc. Psychiatry 54, 1265–1274. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01652-7

Clarke, D. M., and Kissane, D. W. (2002). Demoralization: its phenomenology and importance. Aust. NZJ. Psychiatry. (2002) 36:733–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-2002,01086.x

Costanza A. Amerio A. Odone A. Baertschi M. Richard-Lepouriel H. Weber K. Suicide prevention from a public health perspective. What makes life meaningful? The opinion of some suicidal patients. Acta. Biomed. (2020a) 91:128–134. doi: 10.23750./abm.v91i3-S.9417.

Costanza, A., Baertschi, M., Richard-Lepouriel, H., Weber, K., Pompili, M., Canuto, A., et al. (2020b). The presence and the search constructs of Meaning in Life in suicidal patients attending a psychiatric emergency department. Front. Psychiatry 11, 327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00327

Costanza, A., Vasileios, C., Ambrosetti, J., Shah, S., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A., et al. (2022). Demoralization in suicide: a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 157, 110788. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110788

Dobson, J. (2022). Men wage war, women and children pay the price. BMJ. 376, o634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o634

Editorial. (2022) Children: innocent victims of war in Ukraine. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 6 279–289. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00102-X.

Ekblad, S., Kastrup, M. C., Eisenman, D. P., and Arcel, L. T. Interpersonal Violence towards Women. in Immigrant Medicine, Walker PF, Barnett ED (Eds), Philadelphia: Elsevier (2007). p.665

Elvevåg, B., and DeLisi, L. E. (2022). The mental health consequences on children of the war in Ukraine: a commentary. Psychiatry Res. 317, 114798. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114798

Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc. Sci. Med. (1997) 45, 1207–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3.

Frank J. D. Psychotherapy: the restoration of morale. Am. J. Psychiatry. (1974) 131, 271–274. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.3.271.

Gaffey, M. F, Waldman, R. J, Blanchet, K, Amsalu, R, Capobianco, E, and Ho, L. S. (2021). Delivering health and nutrition interventions for women and children in different conflict contexts: a framework for decision making on what, when, and how. Lancet. 397, 543–554. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00133-1

Hodes M. Thinking about young refugees' mental health following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. (2022). doi: 10.1177/13591045221125639

Hollifield M. Verbillis-Kolp S. Farmer B. Toolson E. C. Woldehaimanot T. Yamazaki J. The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15): development validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, PTSD in refugees. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) 35, 202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.

Huguelet P. Guillaume S. Vidal S. Mohr S. Courtet P. Villain L. Values as determinant of meaning among patients with psychiatric disorders in the perspective of recovery. Sci. Rep. (2016) 6, 27617. doi: 10.1038/srep27617.

Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered Assumptions: Towards a New Psychology of Trauma. New York: Free Press (1992), p. 256.

Javanbakht, A. (2022). Addressing war trauma in Ukrainian refugees before it is too late. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 13, 2104009. doi: 10.1080/20008066.2022.2104009

Johnson, R. J., Antonaccio, O., Botchkovar, E., and Hobfoll, S. E. (2022). War trauma and PTSD in Ukraine's civilian population: comparing urban-dwelling to internally displaced persons. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 57, 1807–1816. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02176-9

Kaufman, K. R., Bhui, K., and Katona, C. (2022). Mental health responses in countries hosting refugees from Ukraine. BJ. Psych Open. 8, 1–10. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2022.55

Martsenkovskyi, D., Martsenkovsky, I., Martsenkovska, I., and Lorberg, B. (2022). The Ukrainian paediatric mental health system: challenges and opportunities from the Russo-Ukrainian war. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 533–535. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00148-1

Murphy, A., Fuhr, D., Roberts, B., et al. (2022). The health needs of refugees from Ukraine. BMJ 377, o864. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o864

Pacione, L., Measham, T., and Rousseau, C. (2013). Refugee children: mental health and effective interventions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 15, 341. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0341-4

Peltonen, K., and Punamäki, R. L. (2010). Preventive interventions among children exposed to trauma of armed conflict: a literature review. Aggress. Behav. 36, 95–116. doi: 10.1002/ab.20334

Roberts, B, Makhashvili, N, Javakhishvili, J, Karachevskyy, A, Kharchenko, N, and Shpiker, M. (2019). Mental health care utilisation among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: results from a nation-wide survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr Sci. 28, 100–111. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000385

Robjant, K., and Fazel, M. (2010). The emerging evidence for narrative exposure therapy: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30:1030–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.07004

Ruf, M,, Schauer, M, Neuner, F, Catani, C, Schauer, E, and Elbert, T. (2010). Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: a randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. J. Trauma Stress 23, 437–45. doi: 10.1002/jts.20548

Schaal, S., Elbert, T., and Neuner, F. (2009). Narrative exposure therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy. A pilot randomized controlled trial with Rwandan genocide orphans. Psychother Psychosom. 78, 298–306. doi: 10.1159/000229768

Schwartz, L., Nakonechna, M., Campbell, G., Brunner, D., Stadler, C., Schmid, M., et al. (2022). Addressing the mental health needs and burdens of children fleeing war: a field update from ongoing mental health and psychosocial support efforts at the Ukrainian border. Eur J. Psychotraumatol. 13, 2101759. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2022.2101759

Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J., and Roberts, B. (2022). The Ukraine crisis: Mental health resources for clinicians and researchers. J. Trauma. Stress, 35, 775–777. doi: 10.1002/jts.22837

Slobodin, O., and de Jong, J. T. (2015). Mental health interventions for traumatized asylum seekers and refugees: What do we know about their efficacy? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 61, 17–26. doi: 10.1177/0020764014535752

Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Acarturk, C., Anttila, M., Au, T., Ballette, F., et al. (2019). Efficacy and acceptability of psychosocial interventions in asylum seekers and refugees: systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 28, 376–388. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000027

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Operational Data Portal. (2022a). Available online at: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed November 27, 2022).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Operational Data Portal. (2022b). Available online at: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/ukr/751 (accessed November 27, 2022).

Uphoff, E., Robertson, L., Cabieses, B., Villalón, F. J, Purgato, M., Churchill, R., et al. (2020). An overview of systematic reviews on mental health promotion, prevention, and treatment of common mental disorders for refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD013458. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013458.pub2

Velu, M. E, Martens, I, Shahab, M, de Roos, C, Jongedijk, R. A, and Schok, M. (2022). Trauma-focused treatments for refugee children: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of KIDNET versus EMDR therapy versus a waitlist control group (KIEM). Trials 23, 347. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06178-z

Keywords: war, Ukraine, refugees and asylum seekers, children, mental health and psychosocial programs, demoralization, meaning in life, meaning-based psychotherapy

Citation: Costanza A, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Magnani L, Huguelet P, Serafini G, Pompili M and Amore M (2022) Meaning-centered therapy in Ukraine's war refugees: An attempt to cope with the absurd? Front. Psychol. 13:1067191. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1067191

Received: 11 October 2022; Accepted: 07 December 2022;

Published: 22 December 2022.

Edited by:

Argyroula Kalaitzaki, Hellenic Mediterranean University, GreeceReviewed by:

Areti Efthymiou, Hellenic Mediterranean University, GreeceCopyright © 2022 Costanza, Amerio, Aguglia, Magnani, Huguelet, Serafini, Pompili and Amore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Amerio,  YW5kcmVhLmFtZXJpb0B1bmlnZS5pdA==

YW5kcmVhLmFtZXJpb0B1bmlnZS5pdA==

Alessandra Costanza

Alessandra Costanza Andrea Amerio

Andrea Amerio Andrea Aguglia

Andrea Aguglia Luca Magnani

Luca Magnani Philippe Huguelet1,2

Philippe Huguelet1,2 Gianluca Serafini

Gianluca Serafini Maurizio Pompili

Maurizio Pompili Mario Amore

Mario Amore