- 1School of Economics and Management, Xi’an University of Technology, Xi'an, China

- 2Department of Business Administration, Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Pakistan

Background: Value-driven career attitude (VDCA) is considered a dimension of a protean career attitude (PCA). Individuals with this attitude seek out personally meaningful experiences and set their own psychological career success standards. This study investigates the association between value-driven career attitude and job performance. It looks at how organizational citizenship behavior affects the relationship between value-driven career attitudes and job performance.

Methods: A self-reported questionnaire was used to collect data from 400 random employees of SMEs in Pakistan during the early pandemic. We chose Cochran’s formula to determine the appropriate sample size, and PLS-SEM was used to analyze the model. P-O fit and self-determination theory is the theoretical lenses used in this study. The underpinning theories to this study enable the researchers to establish a link between VDCA, OCB, and job performance.

Results: By analyzing a sample of 400 employees from active enterprises, we discover that VDCA contributes to an improvement in job performance. Furthermore, OCB plays an intervening effect in the relationship between VDCA and job performance. Thus, the study provided evidence for the underpinning models of P-O fit and self-determination theory.

Conclusion: This study adds to the body of knowledge by investigating the connections between VDCA, OCB, and job performance in SMEs. The existing literature sheds scant light on these linkages, leaving a gap that this study will address. The current study expands on other themes to provide an in-depth analysis of many under-explored PCA outcomes, which may open up new avenues for future researchers to broaden and strengthen PCA with other constructs.

Introduction

In the past two decades, organizations have encountered many new difficulties that have profoundly impacted organizational structures and the nature of work. These changes substantially impact career advancement in the workplace (Morley, 2004). Unprecedented occurrences, such as the current COVID-19 outbreak, have forced individuals to reevaluate their employment and professions (Akkermans et al., 2020). Previously, most career studies were based on the conventional career progression paradigm, accentuating full-time, long-term employment with the same organization and a solid commitment to that organization (Valcour and Ladge, 2008). As a career pattern, lifetime employment with a single employer is falling due to the changing career landscape, which is characterized by less loyalty, higher flexibility, and uncertainty in economic and employment connections (Briscoe and Hall, 2006). Employees are now pursuing careers in several organizations, erasing organizational barriers (Kozlowski and Klein, 2000). These developments significantly affect people’s daily lives in the workplace (Harel et al., 2003). Modern career theories explain the career competencies required to manage such contextual transformations effectively. For more than two decades, traditional professional paths gave way to more personalized models, such as the “protean.” Hall (2004) defined the protean concept as a profession in which success standards are psychological and based on personal beliefs, and career management behaviors reflect personal preference rather than the direction of the organization.

The concept of protean career attitude is derived from protean career theory. This concept was inspired by the Greek god Proteus, known for his adaptability and flexibility (Briscoe and Hall, 2006; Waters et al., 2014). The Protean career theory prioritizes individual career management above organizational career management. The theory explains a career type, attitude, or value system that influences a person’s work environment and career choices (Briscoe and Hall, 2006; Waters et al., 2014). A career attitude that is driven by achievement, values, and the desire to defend personal beliefs or principles is classified as “protean” (Segers et al., 2008; Briscoe et al., 2012; Cortellazzo et al., 2020).

Protean career attitude is a positive psychological factor that individuals use to claim their flexibility and advancement in pursuing continuous learning and psychological career accomplishment. This is different from objective career success, which is measured by things like compensation, and position (Hall, 1996, 2004; Arthur et al., 2005). Two sorts of attitudes were recognized by Briscoe and Hall (2006). One of them was a values-driven professional mindset, which posited that a person’s job success is defined and judged based primarily on his or her intrinsic values and beliefs rather than the organization.

People with a protean career attitude are value-driven (Volmer and Spurk, 2011). Individuals exhibit a values-driven attitude when they pursue meaningful work based on their own values of freedom and progress and the goal of psychological success, as opposed to the organization’s values. Their individual values and beliefs influence their career decisions (Hall, 1996; Briscoe and Hall, 2006; Sullivan and Baruch, 2009). Direnzo et al. (2015) and Hall (2004) argue that being “values-driven” does not mean that you always value liberty and freedom of expression. The term may instead be used to emphasize the importance of loyalty, compliance, and devotion (Arnold and Cohen, 2008), along with safety and a way of life (Gerber et al., 2009). Personal values, like one’s identity and self-awareness, are essential to a person. They allow them to choose work that reflects their most important ideas or passions, to be themselves at work, and to find personal fulfillment by adopting subjective motives (Inkson, 2006; Dries, 2011).

A values-driven approach indicates an individual’s heightened awareness of their preferences and serves as the baseline for executing and evaluating decisions (Hall and Mirvis, 1995). Moreover, in the modern workplace, where multiple career paths have replaced the traditional one-way approach to the top, a value-driven mentality is a prerequisite for an individual to recognize the distinctiveness of his or her career life (Richardson, 2000). This career path is marked by job mobility in multiple directions and the use of an ample range of transferable professional credentials in flexible arrangements with different organizations (Baruch, 2006; Clarke, 2009).

According to several studies, being career-proactive and self-driven increases job happiness and perceived professional prosperity (Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran, 2005; Cabrera, 2009). Values-driven individuals were more likely to be proactive, engrossed in learning, and open to new experiences, but their association with social capital was not statistically significant (Li et al., 2022). Katz and Kahn (1966) argues that developing and defining identity depends on the expression of values. New evidence suggests that a value-driven career outlook strongly indicates internal and external confidence in one’s employability (Lin, 2015). As a result, career researchers have changed their focus from organizational to personal career management, with a few notable exceptions (Baruch and Peiperl, 2000; Quigley and Tymon, 2006; Abele and Wiese, 2008). Research on unemployment also shows a connection between the PC’s values-driven component and self-esteem since maintaining one’s sense of self while unemployed is linked to psychological well-being (Cassidy, 2001).

Segers et al. (2008) discovered an absolute correlation between age and gender and a values-driven attitude, with men having higher values-driven as opposed to women and values-driven career management findings rising with age. In contrast, Mainiero and Sullivan (2005) find that women are more values-driven, and differences may exist for people who are further along in their careers. In this regard, Inceoglu et al. (2008) claimed that females are more motivated by job security and are choosing jobs that allow them to be successful on their own terms rather than by objective metrics of career accomplishment like money, status, and promotion (Heslin, 2005). Values-driven and mobile preferences should be advantageous in a career climate that is more employee-centric (Li et al., 2022). Few studies also showed that affective commitment is inversely correlated with a value-driven career orientation (Alonderienė and Šimkevičiūtė, 2018). Çakmak-Otluoğlu (2012) highlights the conflict between normative commitment and value-driven career management. He also claimed that hesitant individuals about their personal values are more normatively devoted to their organizations. In contrast, few studies found that the values-driven PCO negatively impacted psychological well-being (Rahim and Zainal, 2015; Li, 2018).

Person-organization (P-O) fit theory and self-determination theory can be stated along these lines to conceptualize and establish the relationship between VDCA, OCB, and job performance. The compatibility of values and expectations between individuals and organizations is called P-O fit. P-O fit is a building element of the P-E fit construct (Caplan, 1987). Values are an essential characteristic that can be directly and meaningfully compared between individuals and organizations (Cable and Judge, 1997). According to Argyris (1957), an individual’s organizational behavior results from an interaction between the person and the organization (Verquer et al., 2003). Most research on P-O fit has focused on the congruence between organizational value patterns and human value behaviors (Kristof, 1996). Value congruence is now generally recognized as the operationalization of P-O fit (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). When highly valued personnel share the same values as the organization, they will adhere to the firm’s values (Gubler et al., 2014; Li et al., 2022). This value congruence is expected to positively impact individual performance (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Butt et al., 2020). P-O fit is essential for organizations because there are strong links between it and organizational citizenship behaviors (Tziner, 1987), work attitudes (Dawis and Lofquist, 1984; Cable and Parsons, 2001), and job performance (Cable and Parsons, 2001).

For understanding VDCA and job performance, a comprehensive framework is provided by self-determination theory. Self-determination theory claims that intrinsic values and motivations can lead to fulfillment since they reflect psychological development and self-actualization, which sets them apart from extrinsic motivations (Deci and Ryan, 1985). VDCA is also associated with inner feelings of contentment and self-actualization (Hall and Moss, 1998). Kuvaas (2009) found that the intrinsic motivation of public sector employees was substantially connected with their self-reported job performance and knowledge sharing.

Although the protean career has been studied extensively, there is little empirical evidence to support it because it is still in the preliminary phases of establishing generic roots (Hall, 2004; Granrose and Baccili, 2006; De Vos and Soens, 2008). Prior studies have paid little consideration to the relationship between VDCA, OCB, and job performance. This study intends to establish empirical evidence on these links by utilizing this gap, particularly in developing nations such as Pakistan. Despite significant research on SMEs in both established and emerging economies (Eze and Okpala, 2015; Manzoor et al., 2021), no study has been focused on the relationship between VDCA, OCB, and job performance in the SME sector. Furthermore, due to the individualistic nature of Western culture, the concept of PCA (VDCA and SDCA) has gained the most attention (Tschopp et al., 2014). As a result, there was a call for empirical PCA research in a non-American culture to investigate potential divergence in career attitudes due to communal and civilizing differences (Sullivan and Baruch, 2009). Consequently, this study explored the impact of a value-driven career attitude on job performance, with OCB serving as a mediator in the SME sector. This study focuses on current VDCA knowledge as people’s interest in protean careers grows (Park et al., 2022), particularly during the pandemic.

The success of SMEs is frequently used as a barometer of economic growth (Veskaisri et al., 2007). Small businesses’ efficiency and competitiveness are crucial to economic growth (Beaver, 2003). These economies prioritize the SME sector regarding economic growth and job generation (Dalrymple, 2004; Laudal, 2011; Mehmood et al., 2019). In emerging nations like Pakistan, SMEs account for 80% of employment, 40% of GDP, and around 30% of exports (SMEDA, 2005, 2007, 2008-2009). SMEs still have difficulty keeping skilled people, so finding, training, and retaining talent is becoming increasingly important. Organizations must assist employees in enhancing their performance by providing the necessary developmental resources and support. In this setting, SMEs should develop career advancement strategies that are adapted to the needs of the workforce and effective at retaining outstanding employees (Star, 2020).

This study investigates the association between a value-driven career attitude and job performance. It looks into how organizational citizenship behavior mediates between value-driven career attitudes and job performance. It reviews the literature on VDCA, OCB, and job performance, as well as the significance of such phenomena in SMEs in developing nations where the research was conducted. The four hypotheses provided in this research are examined using structural equation modeling. The following stage evaluates the pertinent literature, describing the research methods and findings. On the basis of the results and limitations of this study, the implications and the potential for additional research are underlined.

Literature review

This section investigates the existing literature on value-driven career attitudes, OCB, and job performance from several theoretical and relational vantage points.

VDCA and job performance

According to Motowidlo (2003), a person’s job performance is the total expected value to the organization of the discrete behavioral episodes a person does over a certain amount of time. The concept of performance has developed over time (Campbell et al., 1993; Welbourne et al., 1998; Johnson, 2003). For many years, researchers have judged the performance of individuals based on how well they carry out the responsibilities outlined in their job descriptions (Locke and Latham, 1990; Ilgen and Pulakos, 1999). Recently, however, job performance has been evaluated based on specific behaviors linked to the features and surroundings of the workplace (Pulakos et al., 2000; Griffin et al., 2007). This transformation occurred as the organizational environment shifted from stable to dynamic (Griffin et al., 2007). As a result, rather than being evaluated on their ability to do job, employees are assessed on how they behave in their roles (Ilgen and Pulakos, 1999).

Over time, the nature of work has evolved from being relatively static to becoming fluid. Several studies have examined how different organizational traits affect performance to determine how supervisors may enhance the performance of their employees. Hall (2004) indicates that an individual with a strong PCA (VDCA and SDCA) may be a higher performer due to his or her intrinsic motivation and ambition for psychological achievement (Hall et al., 2018), which can result in a tremendous performance. Baruch (2014) determined the strong relationship between PCA (VDCA and SDCA) and task performance. According to De Vos and Soens (2008), PCA is a potent predictor of professional growth. Briscoe et al. (2012) and Baruch (2014) discovered a correlation between self-reported individual performance metrics and protean career inclinations. Individuals can improve their job performance and self-actualization to achieve their objectives, influencing professional decision-making and exploration (Hall, 2004; Waters et al., 2015).

Constructive work attitudes and innovation positively impact job performance in organizations with employee-centered designs (Christensen et al., 2009). Research has also shown that spending on human capital improves job performance, employability, sustainability in the workforce, and the capacity to adjust to fluctuating market working conditions (Casuneanu, 2011; Manzoor et al., 2019). There is a substantial correlation between P-O fit and job performance (Cable and Parsons, 2001), which makes it crucial for organizations. Employees with VDCA are proactive, and proactivity was found to be a component of job function performance (Griffin et al., 2007). They obtain information on potential work possibilities, career interests, talents, and abilities by soliciting comments on their job performance (Weng and McElroy, 2010; Li, 2018). A positive and confident outlook on one’s protean career (VDCA and SDCA) has been shown to have a statistically significant, positive interaction with work excitement and proactivity (Seibert et al., 1999; Baruch, 2014). Career proactivity is empirically linked to job success, career happiness (Butt et al., 2020), career advancement, and job performance (Locke et al., 1984; Seibert et al., 2001; Arthur et al., 2005; Volmer and Spurk, 2011).

We feel that in today’s highly competitive business environment, a person with a robust value-driven attitude will be more likely to achieve outstanding job performance, as these attitudes are closely associated with job satisfaction and productivity. This ubiquitous logic postulates as

H1: Value-driven career attitude has an impact on job performance.

VDCA and OCB

OCBs are employee actions that contribute to and improve the psychological and social work environment. These actions aren’t required by a structured pay system and are meant to help the organization do its job well (Luthans, 2005). Williams and Anderson (1991) divided OCB into two types and classified them as OCBI and OCBO. OCBI refers to behaviors that directly benefit specific individuals within an organization and, as a result, indirectly contribute to organizational effectiveness (Williams and Anderson, 1991; Organ, 1997; Organ and Paine, 1999; Lee and Allen, 2002; Dalal, 2005; Niroula and Chamlagai, 2020). OCBO is a term for actions that a person takes that could improve the performance of an organization as a whole (Williams and Anderson, 1991; Organ, 1997; Organ and Paine, 1999; Dalal, 2005). The progress of an organization is dependent not just on employees’ performance inside their assigned roles but also on their performance outside of those roles (Podsakoff et al., 1997). Benefits from OCBs may accrue to the organization as a whole or an individual employee (Williams and Anderson, 1991). Regardless of the OCBs’ intended audience, organizations that can motivate their employees to make this extra effort will have a more robust workforce and a significant competitive advantage (Bolino and Turnley, 2003). Several researchers have emphasized the importance of OCB for human resources because it correlates with the efficient operation of organizations (Hui et al., 2004; Shih and Chen, 2011) and partially incorporates in-role performance in assessment appraisal (Presti et al., 2019).

OCB has garnered the majority of research focus (Smith et al., 1983). Previous empirical studies have examined the affiliation between OCB and a range of other variables, including employee satisfaction, job commitment, turnover intentions (Huak et al., 2015), intention to stay (Priyanka, 2016), quality management, and organizational performance (Aslefallah and Badizadeh, 2014). Previous studies exploring the relationship between these concepts and other factors found that PCA (VDCA and SDCA) was positively associated with OCB. (Jawahar et al., 2008; Presti et al., 2019). A study conducted in Portugal relating autonomous career orientations with OCBs revealed that individuals with a high PCA exhibit more OCBs (Rodrigues et al., 2015). The association analysis results fallout a strong link between the traits of protean jobs and the OCB (Joshi et al., 2021).

The empirical research on the link between VDCA and OCB is in its infancy (Rowe, 2013; Alok and Rajthilak, 2021; Joshi et al., 2021). Thus, it is hypothesized that a value-driven career attitude would have a favorable influence on OCB.

H2: Value-driven career attitude would positively influence OCB.

Value-driven career attitude, OCB, and job performance

Existing research demonstrates that PCA (VDCA and SDCA) professionals benefit themselves and their organizations by accomplishing greater levels of intrinsic and extrinsic career triumph through exemplary job performance. A protean career is linked to better job performance, higher OCBs, and higher organizational involvement (Rodrigues et al., 2015), all of which lead to better organizational performance (Hall, 2004). Employee advancement is linked with enhanced performance, OCB, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and reduced intention to leave the organization (Birdi et al., 1997; Ellinger, 2004; Benson, 2006).

Organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) have long been marked as an important component of individual success and performance (Dunlop and Lee, 2004). Several studies investigate the significance of OCB in determining the association between human resource management approaches and performance (Sun et al., 2007). Researchers have discovered a strong link between P-O fit, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance in the past (Tziner, 1987; Cable and DeRue, 2002; Iplik et al., 2011). Chien (2003) argues that OCB’s incorporation into the workplace can boost productivity on both an individual and companywide scale. Previous research has assessed the impacts of OCB on performance, customer service and satisfaction, sales revenue, and capital sufficiency (Organ et al., 2011). Individual OCB contributes to enhanced organizational performance and operational effectiveness (Choi, 2009; Organ et al., 2011). Individuals can improve their job performance and self-actualization to achieve their objectives, subsequently influencing professional decision-making and exploration (Hall, 2004; Waters et al., 2015). OCB has been found to be a conclusive predictor of job performance in previous research (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Harwiki, 2016; Bagyo, 2018; Hidayah and Harnoto, 2018; Lestari, 2018; Soumyaja and Kamalanabhan, 2022) and a significant contributor to both organizational effectiveness and social relationships inside the firm (Organ et al., 2005). Previous research discovered that OCB influenced high-and low-performance respondents (Callea et al., 2016; Laski and Moosavi, 2016; Basu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017). OCB across individuals enhances organizational effectiveness (Choi, 2009).

In addition, no prior research has evaluated the association between OCB in VDCA and job performance mediation. Based on the above facts, we have sought to assess and explain the relationship between value-driven career attitude and job performance, considering OCB as a mediating variable. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H3: There is a positive relationship between OCB and job performance.

H4: OCB plays a mediating role between VDCA and job performance.

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model described in the study's theoretical framework.

Methodology

Sampling

The sample for this study is comprised of Pakistani professionals working for SMEs. In order to limit sampling error, it is necessary to designate an adequate sample size in survey research (Hair et al., 2010a; Siyal et al., 2019). To this end, we chose Cochran’s formula (Cohen, 1992; Siyal et al., 2019). The Cochran’s formula is appropriate for use in situations where the population size is unknown but the number is high (Chaokromthong and Sintao, 2021). A minimum sample size of 385 was acquired based on criteria at a confidence level of 95% with a precision of 5% (plus or minus; z value was 1.96). In order to address the issue of inappropriate responses, a minimum of 500 samples must be collected. A large sample size ensures the accuracy of structural equation modeling (Siyal et al., 2019). Due to its diversity and the Cochran formula, stratified sampling is a valid method for determining the sample’s representation of the larger population (Stringer et al., 2011). Based on a number of tests, it was decided that the research’s sample was a good representation of the whole population, with a reliability of 0.90 and a good level of consistency across all questions:

Data collection procedure

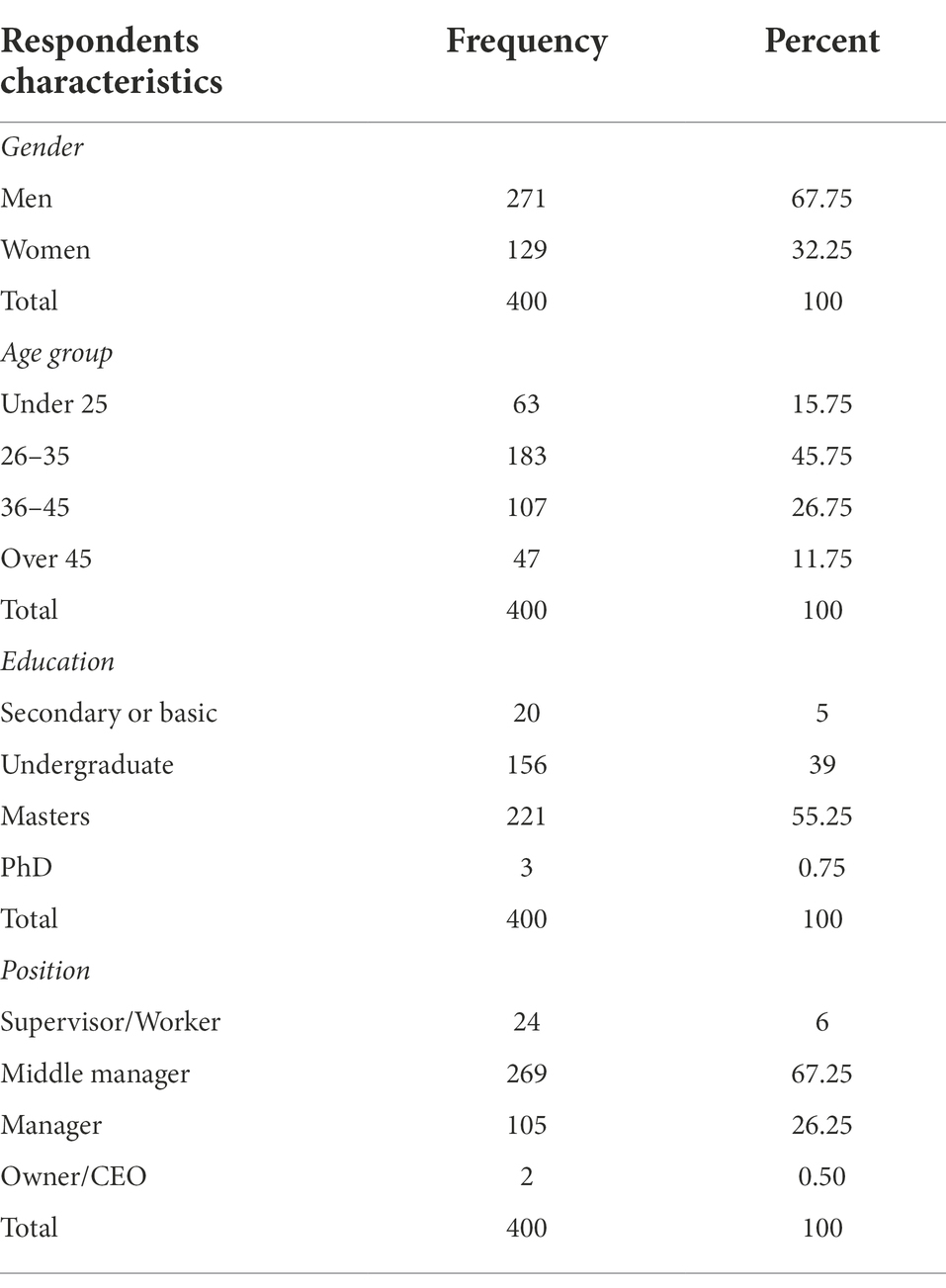

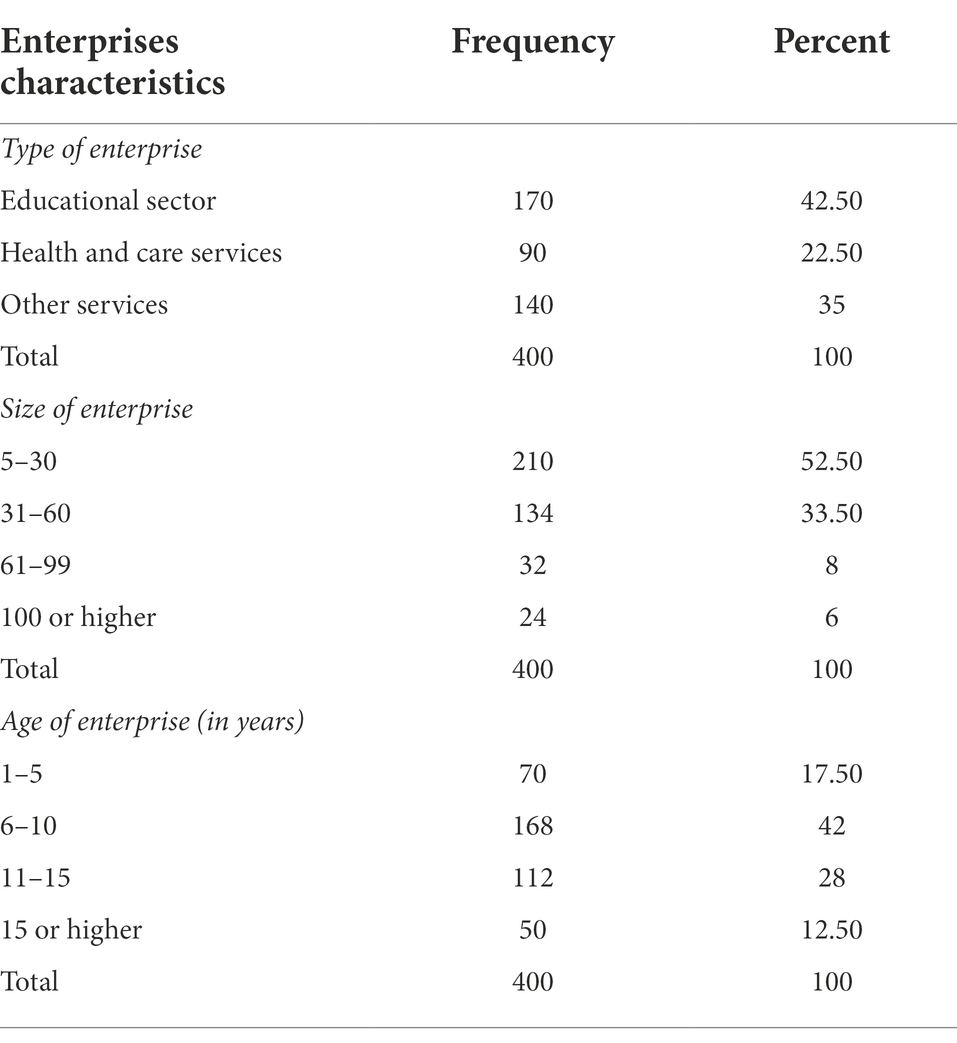

For this study, 500 employees from active SMEs in Pakistan were chosen from all administrative departments. Out of the 500 eligible respondents, 450 questionnaires were returned. Due to insufficient information provided by respondents, 50 questionnaires were denied, whereas 400 completed questionnaires were utilized for data analysis in this study. This study admitted 271 males (67.75%) and 129 females (32.25%). The ages of key informants ranged from under 25 (63), 26 to 35 (183), 36 to 45 (107), and over 45 (47), with percentages of 15.75, 45.75, 26.75, and 11.75, respectively. In this study, career levels ranging from supervisor/worker (24, 6%), middle-level manager (269, 67.25%), manager (105, 26.25%), and owner/CEO (2, 0.50%) were counted. Similarly, respondents with basic/secondary level (20), undergraduate (156), Master’s (221), and Ph.D. (3) degrees had 5%, 39%, 55.25%, and 0.75%, respectively. Tables 1, 2 depict the demographic diversity and characteristics of the study population in detail.

Measures

Standardized measurements were used to collect information on value-driven career attitudes, organizational citizenship behaviors, and job performance. Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale.

Value-driven career attitude

The VDCA was tested using the six items of the PCA scale created by Briscoe et al. (2006). On a five-point Likert scale, individuals indicate the extent to which they believe they are in charge of their values (e.g., “I will follow my own advice if my employer asks me to do something against my values”). The scale ranges from 1 (to little or no) to 5 (to a great extent). This values-driven scale measures the degree to which individuals follow their careers instead of organizational values (Volmer and Spurk, 2011).

Organizational citizenship behavior

The OCB scale developed by Lee and Allen (2002) was utilized to collect data for this research. This measurement consists of 16 elements evaluating the OCBI and OCBO. However, items 3, 14, and 16, namely OCBI3, OCBO6, and OCBO8, were dropped due to low factor loadings. As a rule of thumb, 20 percent of the total items can be eliminated (Hair et al., 2010b). Questions were graded on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating never and 5 indicating always.

Job performance

The scale developed by Koopmans et al. (2013) was adopted to evaluate job performance. The scale has multiple items. Seven items that gage task performance and contextual performance were gathered (Motowidlo, 2012). According to Borman and Motowidlo (1993), two key components determine job performance (task performance and contextual performance). Questions were asked using a Likert, where 1 meant never, and 5 meant always.

Results and discussion

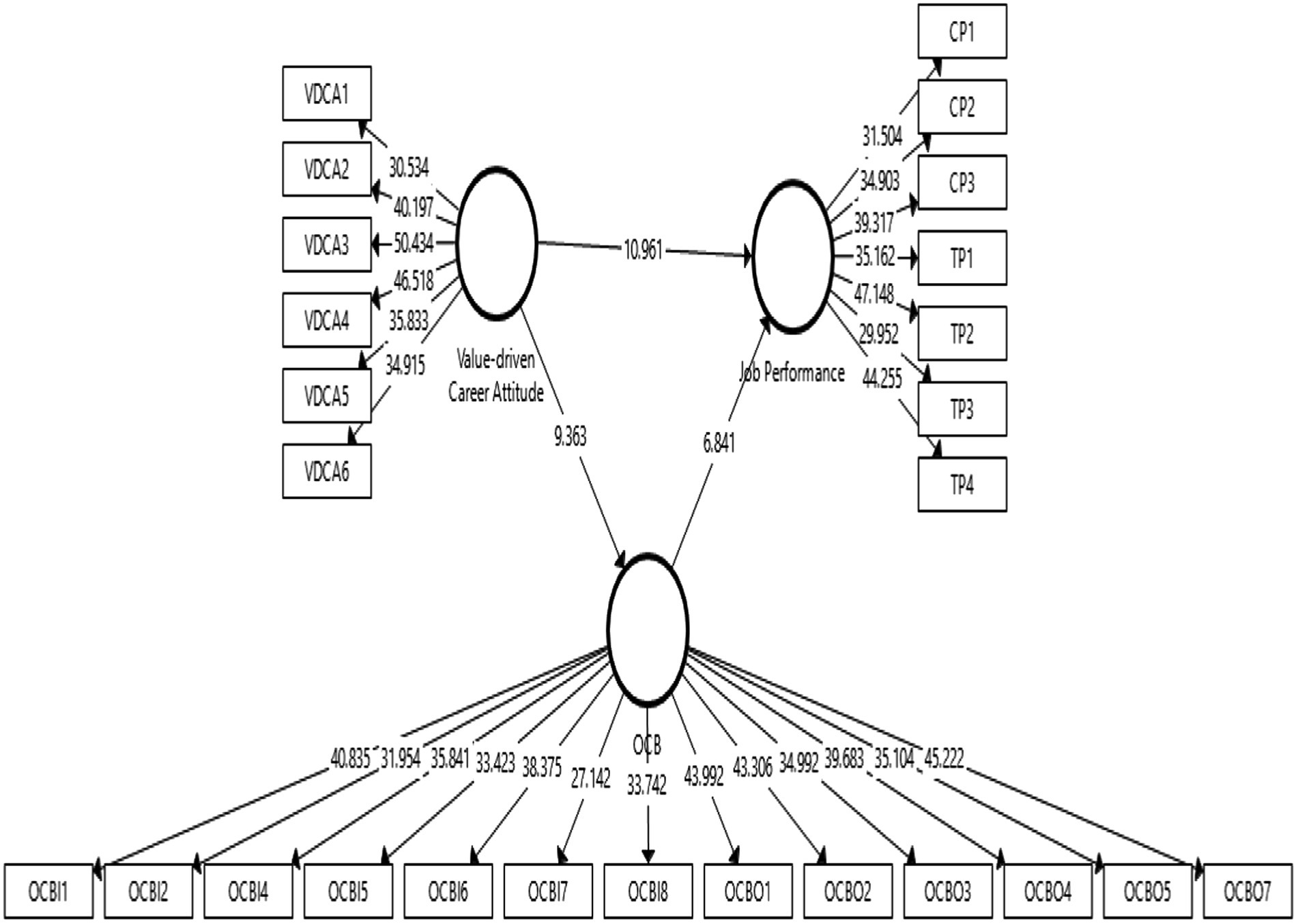

In this study, the theoretical model was examined using PLS-SEM. PLS-SEM is preferred above other standard multivariate techniques (Haenlein and Kaplan, 2004; Ren and Hussain, 2022). PLS-SEM offers a statistically precise evaluation based on a bootstrapping method that yields standard errors for route coefficients (Preacher and Hayes, 2008; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2017). Several assumptions were examined, including multicollinearity, normality, and common method variance (Tabachnick et al., 2007; Hair et al., 2010a; Umrani et al., 2018; Zafar et al., 2021). The researchers then examined the data’s reliability, validity, and structural path. After analyzing the measurement model, the structural model was evaluated using Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modeling (Henseler et al., 2009; Hair et al., 2010a; Rahman and Karim, 2022). The model, which included VDCA, OCB, and job performance, was evaluated in two steps: a measurement model and a structural model (Hair et al., 2014).

Measurement model assessment

In order to evaluate the measurement model, it is crucial to quantify each concept’s reliability, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2010a). We employed PLS-SEM for this aim because scholars in a range of domains widely accept it. Due to its new criteria for critical data analysis, it is ideally suited for this research (Hair et al., 2019).

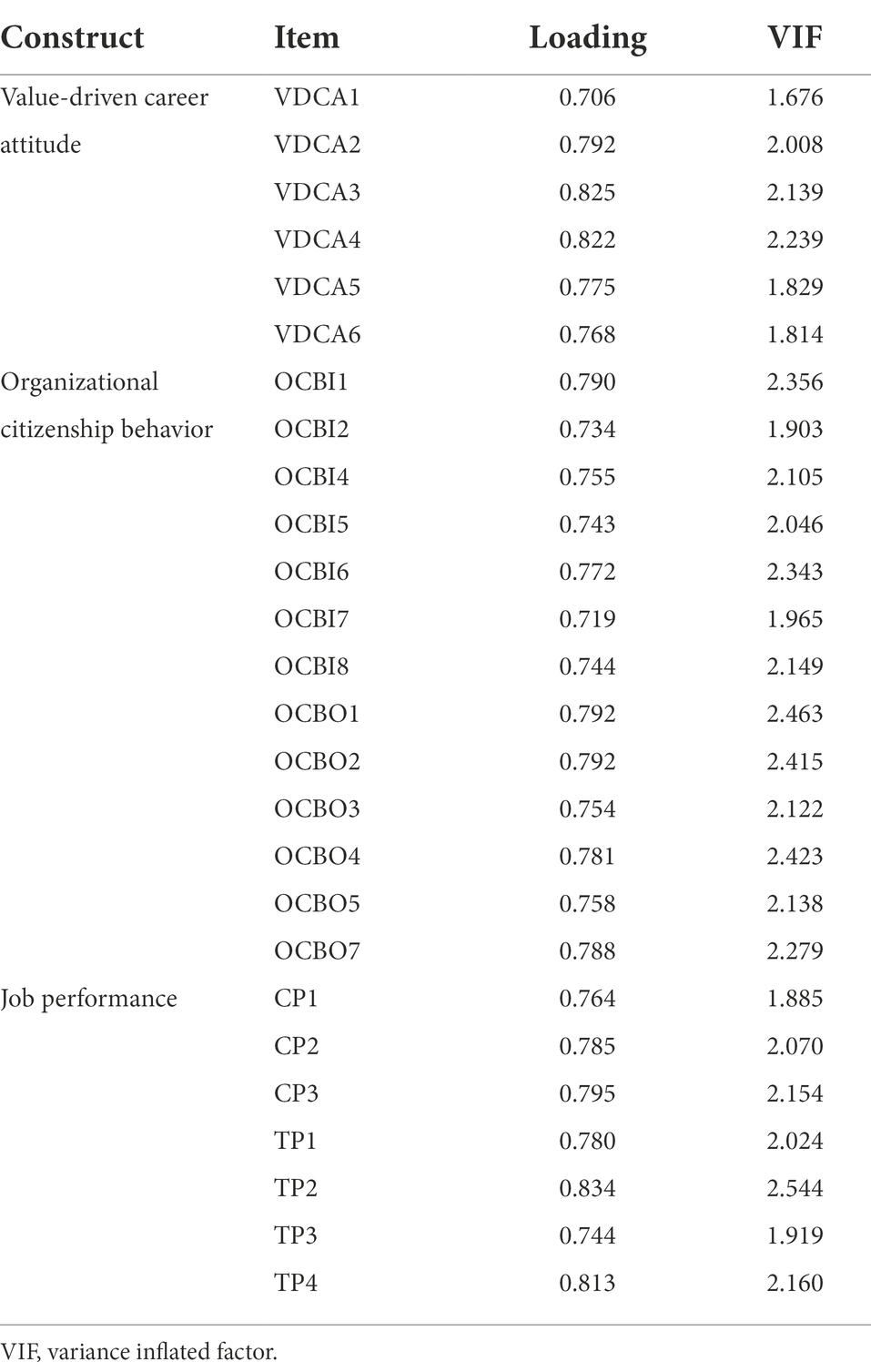

Individual item reliability

The factor loadings of each item in a construct are required to assess the reliability of individual items (Hulland, 1999; Duarte and Raposo, 2010). Hair et al. (2019) proposed that maintaining an item with a value equal to or above 0.5 is considerable. In this investigation, all outer loadings were more than 0.7 (see Table 3), indicating that the individual item reliability criteria were fulfilled.

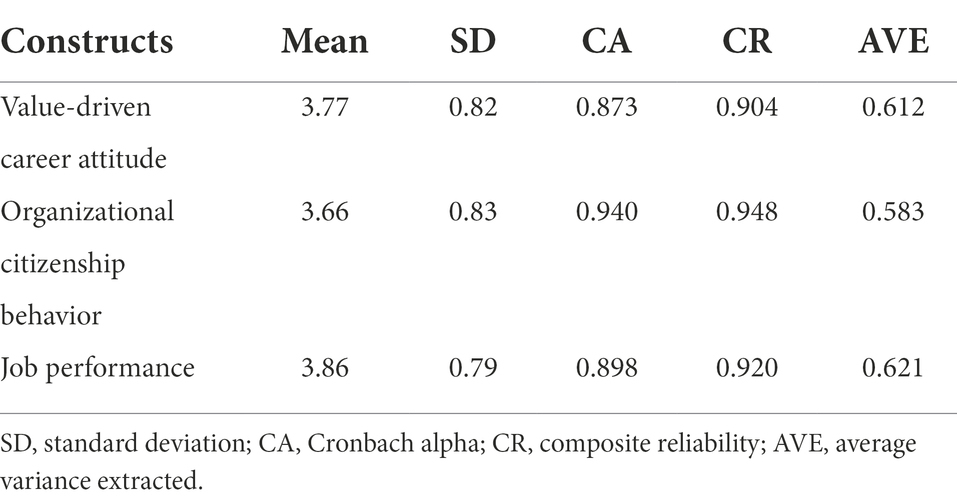

Internal consistency

The average variance extracted (AVE) was utilized to determine convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Bagozzi et al., 1991; Siyal et al., 2019), and all AVE values for latent variables were >0.50. Similarly, researchers evaluated internal consistency reliability by examining composite reliability (CR) scores with a minimum verge of 0.70 and Cronbach’s alpha with a minimum verge of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2016; Siyal et al., 2019; Umrani et al., 2020). The composite reliability coefficients for each construct in this study are displayed in Table 4. This indicates that construct internal consistency reliability is adequate (Bagozzi et al., 1991). The variance inflated factor (VIF) was utilized to evaluate the research design and collinearity bias. Ringle et al. (2015) proposed a VIF verge of 5 or less as the reciprocal of tolerance (Table 3).

Convergent validity

The average variance extracted (AVE) was offered to assess convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). A value of 0.5 or above may be used to demonstrate the convergent validity of a specific variable by adhering to Chin (1998) criterion. According to the AVE values in Table 4, this study obtained an AVE value above the 0.5 thresholds, indicating good convergent validity.

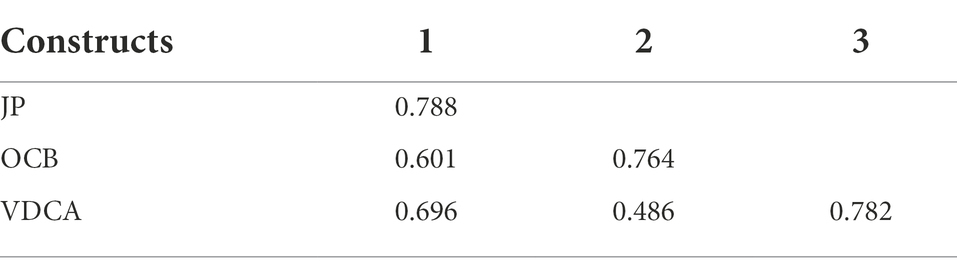

Discriminant validity

Fornell and Larcker (1981) state that discriminant validity can be measured using an AVE value of 0.5 or higher. To demonstrate discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE should also be greater than the correlations between the latent components. As indicated in Table 4, all latent variable AVE values were higher than the cutoff. The correlations between the latent components were smaller than the square root of AVE, as seen in Table 5. Consequently, all metrics indicate that the current investigation’s discriminant validity is sufficient.

Structural model assessment

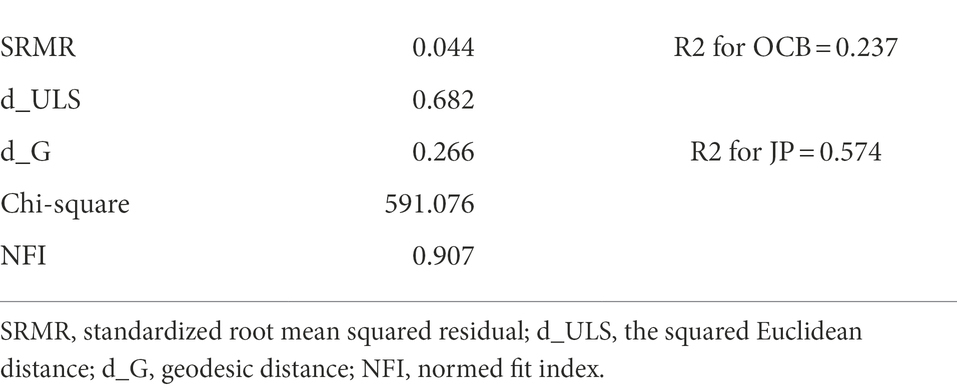

When assessing a model’s potential usefulness, the predictive capability is measured by R2 (Sarstedt et al., 2014). The R2 value indicates the amount of variance in the dependent variable(s) that can be explained by the predictor variable(s) (Hair et al., 2006, 2014; Umrani et al., 2018). According to Umrani et al. (2018), the conditions under which a particular study is conducted determine the acceptable amount of R2 value. According to Chin (1998), an R2 value of 0.60 is considered strong, 0.33 is considered modest, and 0.19 is viewed as weak. However, according to Falk and Miller (1992), an R2 of 0.10 is considered adequate. Based on our data, the coefficient of determination for OCB is = 0.237, and the coefficient for job performance is = 0.574 (Table 6). The value is sufficiently higher than the minimal permissible cutoff, according to Falk and Miller (1992). The square root of the residuals provides an absolute measure of fit, with a value of zero indicating a perfect fit. The SRMR measures the mean squared discordance between observed and implicit correlations in the model. The results show that the SRMR = 0.044 and the NFI = 0.907 are significant; nonetheless, the NFI fit was still satisfactory since it was >0.8 (Zikmund, 2003). Table 6 shows that the study supports the assumption that an SRMR value of 0.08 or less is acceptable (Hu and Bentler, 1998).

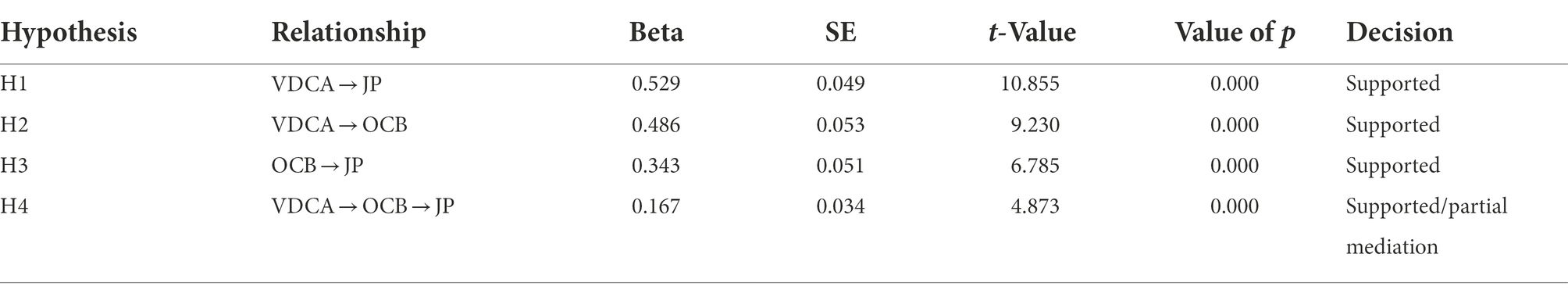

This study used the bootstrapping technique with 5,000 bootstrap samples and a sample size of 400 to determine the significance of the path coefficients (Hair et al., 2010a, 2011, 2014). Table 7 and Figure 2 show that full estimates were obtained using this structural model with statistics. First, H1 predicted that VDCA is strongly associated with job performance. The results of Table 7 and Figure 2 confirmed a confident relationship between VDCA and job performance at a 1% significance level, (β = 0.529, t = 10.855, p = 0.000). As a result, H1 has been confirmed.

Second, we postulate that VDCA has a positive effect on OCB. The outcomes demonstrate a statistically significant association between VDCA and OCB (β = 0.486, t = 9.230, p = 0.000). A second hypothesis, H2, was also tolerated. In hypothesis 3, OCB has a positive impact on job performance. Positive correlations between OCB and job performance were found, as evidenced by the relationship’s β = 0.343, t = 6.785, and p = 0.000 coefficients. The results showed a significant VDCA-OCB-job performance association (β = 0.167, t = 4.873, p = 0.000), proving the fourth hypothesis.

If an indirect path traverses an intermediary construct (mediator), then, according to Baron and Kenny (1986), the mediator serves as a link between independent and dependent constructs. The model is statistically significant if both paths from the independent variable to the dependent variable are significant. If both the direct and indirect paths from the independent variable to the dependent variable are substantial, this indicates some degree of mediation (DeJong et al., 2019). Complete mediation occurs when the direct path is negligible, and the indirect path is significant. The research demonstrates that OCB has a partial mediating impact, supporting Hypothesis 4. Concur that complementing mediation occurs when both direct and indirect pathways are essential and considerable. The results of this study are shown in Table 7.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to investigate the effect of a VDCA on job performance. The data indicates a substantial correlation between VDCA and job performance. These findings confirm previous research revealing that PCA professionals benefit themselves and their organizations by accomplishing tremendous intrinsic and extrinsic career success through exemplary job performance (Sultana and Malik, 2019). Hasan and Altaee (2020) found that bringing people from different career paths together can improve the alignment of high performance in the workplace.

The VDCA appears to promote OCB, resulting in a substantial return for the organization and correlating with an abundance of empirical evidence in the field of previously analyzed studies. According to the study, proactive VDCA employees are likelier to engage in workplace development drives (Jawahar and Liu, 2016). Sturges et al. (2002) found that workers who take charge of their careers are better organizational citizens.

OCB is increasingly recognized as a crucial organizational asset and positively impacts organizational atmosphere and operations (Pletzer et al., 2021). Regarding the hypotheses, this study produces positive results corresponding to evidence already documented in the literature. Individuals with a high VDCA were found to engage in more organizationally healthy behaviors. In contrast, an increase in VDCA was linked with a greater level of commitment and a positive indirect link to extra-role behaviors. Employees with OCB levels above a certain threshold have a positive attitude toward their work and the organization, which translates into more productive work output.

Conclusion

In conclusion, contemporary careers and career selection in the global economy are chaotic and fraught with uncertainty for both individuals and organizations. The potential links between modern professional mindsets and job success have received little consideration from researchers. Evaluating the impact of contemporary careers in developing nations where job security is significant stands out as a challenge. Nonetheless, this study is the first step in defining PCA dimensions as independent constructs and legitimizing them in human and organizational contexts by examining developing nations. An organization should immediately focus on developing career concepts and how they affect the organization and the outside world.

The current study confirms that VDCA significantly contributes to improved job performance and that OCB mediates the relationship between VDCA and job performance. Consequently, firms that invest in performance enhancement to meet individual and organizational objectives should prioritize developing career concepts. This research aids in comprehending the mechanism by which the emerging attitude affects human capital, which is vital for effective career management and the formulation of suitable HR policies (Baruch, 2014). It’s essential to measure how employees feel about their occupations in response to various work designs and organizational support initiatives. This study offers new insights into how enhancing organizational development across the board in developing nations can be accomplished by managing employees effectively in new career management. The two-way communication made possible by PCA allows employers and workers to collaborate on projects and share ideas for improving the organization and the workplace. Which, in the end, aids businesses in reaching their intended markets and forming strategic partnerships.

Limitations and future work

Our findings provide a solid foundation for future research on new career concepts. Similar to the novel contribution to the career literature, this study includes limitations that should be addressed in future studies. One of the primary drawbacks is that it is limited to the occupational field, namely SMEs, restricting the findings’ external validity and generalizability. In the future, the model of this study could be examined with samples from other areas, such as new or emerging markets or more well-known companies, to make our results more applicable to a broader range of situations. Future research can further explore this new career orientation concept by examining it with other variables. In addition, the study encourages replication in various cultural contexts and with diverse samples to increase generalizability. The COVID-19 pandemic is also a limitation because it occurred while collecting data. This means that the findings and effects of future studies may differ from those of this research.

Theoretical and practical implications

Due to the individualistic aspect of Western culture, the concept of PCA has garnered crucial attention (Tschopp et al., 2014). Consequently, there was a demand for empirical PCA research in non-American contexts to study potential disparities in career attitudes related to communal and civilizing characteristics (Sullivan and Baruch, 2009). The researchers empirically tested the hypothesis and discovered that VDCA significantly affects job performance and that OCB acts as a mediator between VDCA and job performance. The significance of the study was achieved, as stipulated in the conceptual model; hypotheses are in accordance with research objectives, and research objectives are in line with research questions.

In a world where change occurs rapidly, the study could assist HRD experts and managers in helping their employees to plan their careers and align their job performance goals with their professional goals and triumphs. The resultant creation of HR policies that promote evolving career conceptions will aid in preventing employee turnover. On the other hand, organizational career management rules that permit self-management will assist protean talented workers in maintaining their jobs and achieving their goals, thereby preventing them from leaving their current positions. These new findings shed light on how career flexibility impacts various organizational divisions. Youth unemployment is a critical challenge facing Pakistani society. However, organizations now have a more significant duty to investigate the human attitudes and behaviors influencing how employees perform and view their professional development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Xi’an University of Technology. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abele, A. E., and Wiese, B. S. (2008). The nomological network of self-management strategies and career success. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 81, 733–749. doi: 10.1348/096317907X256726

Akkermans, J., Richardson, J., and Kraimer, M. L. (2020). The COVID-19 Crisis as a Career Shock: Implications for Careers and Vocational Behavior, Vol. 119. San Diego, USA, CA: Academic Press Inc. Elsevier Science, 103434.

Alok, S., and Rajthilak, R. (2021). Protean and boundaryless career attitude as determinants of well-being among Indian IT temporary agency workers. Vision :09722629211036208. doi: 10.1177/09722629211036208

Alonderienė, R., and Šimkevičiūtė, I. (2018). Linking protean and boundaryless career with organizational commitment: the case of young adults in finance sector. Balt. J. Manag. 13, 471–487. doi: 10.1108/BJM-06-2017-0179

Argyris, C. (1957). Personality and organization; the conflict between system and the individual. Harpers. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1958-01005-000.

Arnold, J., and Cohen, L. (2008). 1 the psychology of careers in industrial and organizational settings: a critical but appreciative analysis. Int. Rev. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 23, 1–44. doi: 10.1002/9780470773277.ch1

Arthur, M. B., Khapova, S. N., and Wilderom, C. P. (2005). Career success in a boundaryless career world. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organizational Psychol. Behav. 26, 177–202. doi: 10.1002/job.290

Aslefallah, H., and Badizadeh, A. (2014). Effect of organizational citizenship behaviour on total quality management and organizational performance (case study: Dana insurance co.). Euro. Online J. Nat. Social Sci. 3, 1124–1136.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., and Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 36, 421–458. doi: 10.2307/2393203

Bagyo, Y. (2018). The effect of counterproductive work behavior (CWB) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) on employee performance with employee engagement as intervening variable. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 20, 83–89. doi: 10.9790/487X-2002048389

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Baruch, Y. (2006). Career development in organizations and beyond: balancing traditional and contemporary viewpoints. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 16, 125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.002

Baruch, Y. (2014). The development and validation of a measure for protean career orientation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 25, 2702–2723. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.896389

Baruch, Y., and Peiperl, M. (2000). Career management practices: an empirical survey and implications. Hum. Resour. Manag. 39, 347–366. doi: 10.1002/1099-050X(200024)39:4<347::AID-HRM6>3.0.CO;2-C

Basu, E., Pradhan, R. K., and Tewari, H. R. (2017). Impact of organizational citizenship behavior on job performance in Indian healthcare industries: the mediating role of social capital. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 66, 780–796. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-02-2016-0048

Beaver, G. (2003). Small business: success and failure. Strateg. Chang. 12, 115–122. doi: 10.1002/jsc.624

Benson, G. S. (2006). Employee development, commitment and intention to turnover: a test of ‘employability’policies in action. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 16, 173–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2006.00011.x

Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3, 424–453. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Birdi, K., Allan, C., and Warr, P. (1997). Correlates and perceived outcomes of 4 types of employee development activity. J. Appl. Psychol. 82, 845–857. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.845

Bolino, M. C., and Turnley, W. H. (2003). More than one way to make an impression: exploring profiles of impression management. J. Manag. 29, 141–160. doi: 10.1177/014920630302900202

Borman, W. C., and Motowidlo, S. (1993). Expanding the Criterion Domain to Include Elements of Contextual Performance.

Briscoe, J. P., and Hall, D. T. (2006). The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: combinations and implications. J. Vocat. Behav. 69, 4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.002

Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., and DeMuth, R. L. F. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers: an empirical exploration. J. Vocat. Behav. 69, 30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.003

Briscoe, J. P., Henagan, S. C., Burton, J. P., and Murphy, W. M. (2012). Coping with an insecure employment environment: the differing roles of protean and boundaryless career orientations. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.12.008

Butt, R. S., Wen, X., and Hussain, R. Y. (2020). Mediated effect of employee job satisfaction on employees’ happiness at work and analysis of motivational factors: evidence from telecommunication sector. Asian Bus. Res. J. 5, 19–27. doi: 10.20448/journal.518.2020.5.19.27

Cable, D. M., and DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 875–884. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875

Cable, D. M., and Judge, T. A. (1997). Interviewers' perceptions of person–organization fit and organizational selection decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 82, 546–561. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.546

Cable, D. M., and Parsons, C. K. (2001). Socialization tactics and person-organization fit. Pers. Psychol. 54, 1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00083.x

Cabrera, E. F. (2009). Protean organizations: Reshaping work and careers to retain female talent. Career Dev. Int. 14, 186–201. doi: 10.1108/13620430910950773

Çakmak-Otluoğlu, K. Ö. (2012). Protean and boundaryless career attitudes and organizational commitment: the effects of perceived supervisor support. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.03.001

Callea, A., Urbini, F., and Chirumbolo, A. (2016). The mediating role of organizational identification in the relationship between qualitative job insecurity, OCB and job performance. J. Manag. Dev. 35, 735–746. doi: 10.1108/JMD-10-2015-0143

Campbell, J. P., McCloy, R. A., Oppler, S. H., and Sager, C. E. (1993). A theory of performance. Personnel Sel. Organ. 3570, 35–70.

Caplan, R. D. (1987). Person-environment fit theory and organizations: commensurate dimensions, time perspectives, and mechanisms. J. Vocat. Behav. 31, 248–267. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(87)90042-X

Cassidy, T. (2001). Self-categorization, coping and psychological health among unemployed mid-career executives. Couns. Psychol. Q. 14, 303–315. doi: 10.1080/09515070110102800

Casuneanu, C. (2011). The Romanian employee motivation system: an empirical analysis. Int. J. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 5, 931–938.

Chaokromthong, K., and Sintao, N. (2021). Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran and Krejcie and Morgan and Green formulas and Cohen statistical power analysis by G* power and Comparisions. Apheit Int. J. 10, 76–86.

Chien, M.-H. (2003). "A study to improve organizational citizenship behaviors", in International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM03): Citeseer. Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand Inc. (MSSANZ), 1364–1367.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 295, 295–336.

Choi, J. N. (2009). Collective dynamics of citizenship behaviour: what group characteristics promote group-level helping? J. Manag. Stud. 46, 1396–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00851.x

Christensen, T., Faxvaag, A., Lærum, H., and Grimsmo, A. (2009). Norwegians GPs’ use of electronic patient record systems. Int. J. Med. Inform. 78, 808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.08.004

Clarke, M. (2009). Plodders, pragmatists, visionaries and opportunists: career patterns and employability. Career Dev. Int. 14, 8–28. doi: 10.1108/13620430910933556

Cooper-Hakim, A., and Viswesvaran, C. (2005). The construct of work commitment: testing an integrative framework. Psychol. Bull. 131, 241–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.241

Cortellazzo, L., Bonesso, S., Gerli, F., and Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2020). Protean career orientation: behavioral antecedents and employability outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 116:103343. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103343

Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 1241–1255. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

Dalrymple, J. F. (2004). “Performance measurement for SME growth: a business profile benchmarking approach,” in Second World Conference on POM and 15th Annual POM Conference, Cancun, Mexico.

Dawis, R., and Lofquist, L. (1984). A Psychological Theory of Work Adjustment. Minneapolis, MN: University. of Minnesota Press.

De Vos, A., and Soens, N. (2008). Protean attitude and career success: the mediating role of self-management. J. Vocat. Behav. 73, 449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.08.007

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Motivation and Self-determination in Human Behavior. NY: Plenum Publishing Co.

DeJong, H., Fox, E., and Stein, A. (2019). Does rumination mediate the relationship between attentional control and symptoms of depression? J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 63, 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.12.007

Direnzo, M. S., Greenhaus, J. H., and Weer, C. H. (2015). Relationship between protean career orientation and work–life balance: a resource perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 538–560. doi: 10.1002/job.1996

Dries, N. (2011). The meaning of career success: avoiding reification through a closer inspection of historical, cultural, and ideological contexts. Career Dev. Int. 16, 364–384. doi: 10.1108/13620431111158788

Duarte, P. A. O., and Raposo, M. L. B. (2010). “A PLS model to study brand preference: an application to the mobile phone market,” in Handbook of Partial Least Squares, vol. Springer, 449–485.

Dunlop, P. D., and Lee, K. (2004). Workplace deviance, organizational citizenship behavior, and business unit performance: the bad apples do spoil the whole barrel. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Indu. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 25, 67–80. doi: 10.1002/job.243

Ellinger, A. D. (2004). The concept of self-directed learning and its implications for human resource development. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 6, 158–177. doi: 10.1177/1523422304263327

Eze, T. C., and Okpala, C. S. (2015). Quantitative analysis of the impact of small and medium scale enterprises on the growth of Nigerian economy:(1993-2011). Int. J. Dev. Emerging Econ. 3, 26–38.

Falk, R. F., and Miller, N. B. (1992). A Primer for Soft Modeling. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Gerber, M., Wittekind, A., Grote, G., Conway, N., and Guest, D. (2009). Generalizability of career orientations: a comparative study in Switzerland and Great Britain. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 82, 779–801. doi: 10.1348/096317909X474740

Granrose, C. S., and Baccili, P. A. (2006). Do psychological contracts include boundaryless or protean careers? Career Dev. Int. 11, 163–182. doi: 10.1108/13620430610651903

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., and Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 327–347. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24634438

Gubler, M., Arnold, J., and Coombs, C. (2014). Reassessing the protean career concept: empirical findings, conceptual components, and measurement. J. Organ. Behav. 35, S23–S40. doi: 10.1002/job.1908

Haenlein, M., and Kaplan, A. M. (2004). A beginner's guide to partial least squares analysis. Underst. Stat. 3, 283–297. doi: 10.1207/s15328031us0304_4

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010a). Canonical Correlation: A Supplement to Multivariate Data Analysis. Multivariate data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed Pearson Prentice Hall Publishing, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010b). “Multirative Data Analysis: A Global Perspective,” New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., and Tatham, R. (2006). “Data Analysis Multivariate,” Upper Saddle River, NJ. Pearson Education).

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2016). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (Pls-Sem). Sage Publications : Thousand Oaks, CA.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., and Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hall, D. (1996). Careers protean century of the. Acad. Manag. Exec. 10, 8–16. doi: 10.5465/ame.1996.3145315

Hall, D. T. (2004). The protean career: a quarter-century journey. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006

Hall, D. T., and Mirvis, P. H. (1995). The new career contract: developing the whole person at midlife and beyond. J. Vocat. Behav. 47, 269–289. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1995.0004

Hall, D. T., and Moss, J. E. (1998). The new protean career contract: helping organizations and employees adapt. Organ. Dyn. 26, 22–37. doi: 10.1016/S0090-2616(98)90012-2

Hall, D. T., Yip, J., and Doiron, K. (2018). Protean careers at work: self-direction and values orientation in psychological success. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 5, 129–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104631

Harel, G., Tzafrir, S., and Baruch, Y. (2003). Achieving organizational effectiveness through promotion of women into managerial positions: HRM practice focus. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 14, 247–263. doi: 10.1080/0958519021000029108

Harwiki, W. (2016). The impact of servant leadership on organization culture, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) and employee performance in women cooperatives. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 219, 283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.04.032

Hasan, A. A., and Altaee, P. D. A. H. (2020). The Role of a Protean Career in High Performance. 10. doi: 10.37648/ijrssh.v10i04.016

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). “The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing,” in New Challenges to International Marketing (Advances in International Marketing, Vol. 20). eds. R. R. Sinkovics and P. N. Ghauri (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 277–319.

Heslin, P. A. (2005). Experiencing career success. Organ. Dyn. 34, 376–390. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.08.005

Hidayah, S., and Harnoto, H. (2018). Role of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), perception of justice and job satisfaction on employee performance. JDM (Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen) 9, 170–178. doi: 10.15294/jdm.v9i2.14191

Huak, M., Pivi, F. G., and Hassan, Z. (2015). The impact of organizational citizenship behavior on Employee’s job satisfaction, commitment and turnover intention in dining restaurants Malaysia. Int. J. Accounting Bus. Manage. 1, 1–17.

Huang, M., Peng, J., and Wang, C. (2017). "The effects of users' organizational citizenship behaviors on information system performance", in 2017 4th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI): IEEE, 1652–1656.

Hui, C., Lee, C., and Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Psychological contract and organizational citizenship behavior in China: investigating generalizability and instrumentality. J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 311–321. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.311

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 20, 195–204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7

Ilgen, D. R., and Pulakos, E. D. (1999). “The changing nature of performance: implications for staffing, motivation, and development,” Frontiers of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

Inceoglu, I., Segers, J., Bartram, D., and Vloeberghs, D. (2008). Age differences in work motivation. Int. J. Psychol. 43:496. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02035.x

Inkson, K. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers as metaphors. J. Vocat. Behav. 69, 48–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.004

Iplik, F. N., Kilic, K. C., and Yalcin, A. (2011). The simultaneous effects of person-organization and person-job fit on Turkish hotel managers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 23, 644–661. doi: 10.1108/09596111111143386

Jawahar, I., and Liu, Y. (2016). Proactive personality and citizenship performance: the mediating role of career satisfaction and the moderating role of political skill. Career Dev. Int. 21, 378–401. doi: 10.1108/CDI-02-2015-0022

Jawahar, I., Meurs, J. A., Ferris, G. R., and Hochwarter, W. A. (2008). Self-efficacy and political skill as comparative predictors of task and contextual performance: a two-study constructive replication. Hum. Perform. 21, 138–157. doi: 10.1080/08959280801917685

Johnson, J. W. (2003). “Toward a better understanding of the relationship between personality and individual job performance.” in Personality and Work: Reconsidering the Role of Personality in Organizations, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Imprint, 83:120.

Joshi, M., Maheshwari, G. C., and Yadav, R. (2021). Understanding the moderation effect of age and gender on the relationship between employee career attitude and organizational citizenship behavior: a developing country perspective. Manag. Decis. Econ. 42, 1539–1549. doi: 10.1002/mde.3325

Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C., Hildebrandt, V., Van Buuren, S., Van der Beek, A. J., and De Vet, H. C. (2013). Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. Int. J Prod. Performance Manage. 62, 6–28. doi: 10.1108/17410401311285273

Kozlowski, S. W. J., and Klein, K. J. (2000). “A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes,” in Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. eds. K. J. Klein and S. W. J. Kozlowski (Jossey-Bass), 3–90.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 49, 1–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., and Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences OF INDIVIDUALS'FIT at work: a meta-analysis OF person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 58, 281–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Kuvaas, B. (2009). A test of hypotheses derived from self-determination theory among public sector employees. Empl. Relat. 31, 39–56. doi: 10.1108/01425450910916814

Laski, S. A., and Moosavi, S. J. (2016). The relationship between organizational trust, OCB and performance of faculty of physical education. Int. J. Humanit. Cult. Stud. 1, 1280–1287.

Laudal, T. (2011). Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Social Responsibility J. 7, 234–256. doi: 10.1108/17471111111141512

Lee, K., and Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 131–142. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131

Lestari, T. W. (2018). Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) variable on employees of PT. Smartfren Jember. Int. J. Social Sci. Bus 2, 231–236.

Li, Y. (2018). Linking protean career orientation to well-being: the role of psychological capital. Career Dev. Int. 23, 178–196. doi: 10.1108/CDI-07-2017-0132

Li, C. S., Goering, D. D., Montanye, M. R., and Su, R. (2022). Understanding the career and job outcomes of contemporary career attitudes within the context of career environments: an integrative meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 43, 286–309. doi: 10.1002/job.2510

Lin, Y.-C. (2015). Are you a protean talent? The influence of protean career attitude, learning-goal orientation and perceived internal and external employability. Career Dev. Int. 20, 753–772. doi: 10.1108/CDI-04-2015-0056

Locke, E. A., Frederick, E., Lee, C., and Bobko, P. (1984). Effect of self-efficacy, goals, and task strategies on task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 69, 241–251. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.241

Locke, E. A., and Latham, G. P. (1990). A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance. Washington, DC: Prentice-Hall, Inc. American Psychological Association.

Luthans, F. (2005). Organizational Citizenship Behavior. 10th Edition Boston Mc Graw-Hill International.

Mainiero, L. A., and Sullivan, S. E. (2005). Kaleidoscope careers: an alternate explanation for the opt-out revolution. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 19, 106–123. doi: 10.5465/ame.2005.15841962

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Bányai, T., Nurunnabi, M., and Subhan, Q. A. (2019). An examination of sustainable HRM practices on job performance: an application of training as a moderator. Sustainability 11:2263. doi: 10.3390/su11082263

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., and Siraj, M. (2021). Small and medium-sized enterprises and economic growth in Pakistan: an ARDL bounds cointegration approach. Heliyon 7:e06340. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06340

Martínez-Martínez, D., Madueño, J. H., Jorge, M. L., and Sancho, M. P. L. (2017). The strategic nature of corporate social responsibility in SMEs: a multiple mediator analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 117, 2–31. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0315

Mehmood, R., Hunjra, A. I., and Chani, M. I. (2019). The impact of corporate diversification and financial structure on firm performance: evidence from south Asian countries. J. Risk Financ. Manage. 12:49. doi: 10.3390/jrfm12010049

Morley, M. J. (2004). Contemporary debates in European human resource management: context and content. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 14, 353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.10.005

Motowidlo, S. J. (2003). “Job performance,” in Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., vol. 12, 39–53.

Motowidlo, S. J. (2012) in Job Performance. eds. S. J. Motowidlo and H. J. Kell (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Rice University)

Niroula, K. B., and Chamlagai, G. P. (2020). Status of organization citizen behavior (OCB) in Nepalese commercial banks. Dristikon Multidiscip. J. 10, 143–156. doi: 10.3126/dristikon.v10i1.34552

Organ, D. W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: It's construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 10, 85–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1002_2

Organ, D. W., and Paine, J. B. (1999). A new kind of performance for industrial and organizational psychology: Recent contributions to the study of organizational citizenship behavior.

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., and MacKenzie, S. B. (2005). Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature, antecedents, and consequences. Washington, DC, United States: SAGE Publications.

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Expanding the criterion domain to include organizational citizenship behavior: Implications for employee selection.

Park, Y., Lee, J. G., Jeong, H. J., Lim, M. S., and Oh, M.-R. (2022). How does the protean career attitude influence external employability? The roles of career resilience and proactive career behavior. Ind. Commer. Train. 54, 317–332. doi: 10.1108/ICT-06-2021-0045

Pletzer, J. L., Oostrom, J. K., and de Vries, R. E. (2021). HEXACO personality and organizational citizenship behavior: a domain-and facet-level meta-analysis. Hum. Perform. 34, 126–147. doi: 10.1080/08959285.2021.1891072

Podsakoff, P. M., Ahearne, M., and MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 82, 262–270. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.262

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., and Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: a critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 26, 513–563. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600307

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). “Assessing mediation in communication research,” in The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication. eds. A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater and Leslie B. Snyder (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.).

Presti, A. L., Manuti, A., and Briscoe, J. P. (2019). Organizational citizenship behaviors in the era of changing employment patterns: the complementary roles of psychological contracts and protean and boundaryless careers. Career Dev. Int. 24, 127–145. doi: 10.1108/CDI-05-2018-0137

Priyanka, S. (2016). Assessing the impact of organizational citizenship behaviour on intention to stay among Bank employees in Coimbatore District. Paripex-Indian J. Res. 5, 140–142.

Pulakos, E. D., Arad, S., Donovan, M. A., and Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 85, 612–624. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.612

Quigley, N. R., and Tymon, W. G. (2006). Toward an integrated model of intrinsic motivation and career self-management. Career Dev. Int. 11, 522–543. doi: 10.1108/13620430610692935

Rahim, N. B., and Zainal, S.-R. M. (2015). Embracing psychological well-being among professional engineers in Malaysia: the role of protean career orientation and career exploration. Int. J. Econ. Manage. 9, 45–65.

Rahman, M. H. A., and Karim, D. N. (2022). Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating role of work engagement. Heliyon 8:e09450. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09450

Ren, Z., and Hussain, R. Y. (2022). A mediated-moderated model for green human resource management: an employee perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1538. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.973692

Richardson, M. S. (2000). A new perspective for counsellors: from career ideologies to empowerment through work and relationship practices. Future Career, 197–211. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511520853.013

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., and Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH. Bönningstedt, Germany.

Rodrigues, R., Guest, D., Oliveira, T., and Alfes, K. (2015). Who benefits from independent careers? Employees, organizations, or both? J. Vocat. Behav. 91, 23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.005

Rowe, K. P. (2013). Psychological capital and employee loyalty: The mediating role of protean career orientation.

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Henseler, J., and Hair, J. F. (2014). On the emancipation of PLS-SEM: a commentary on Rigdon (2012). Long Range Plan. 47, 154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2014.02.007

Segers, J., Inceoglu, I., Vloeberghs, D., Bartram, D., and Henderickx, E. (2008). Protean and boundaryless careers: a study on potential motivators. J. Vocat. Behav. 73, 212–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.05.001

Seibert, S., Crant, J., and Kraimer, M. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 416–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., and Crant, J. M. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Pers. Psychol. 54, 845–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00234.x

Shih, C.-T., and Chen, S.-J. (2011). The social dilemma perspective on psychological contract fulfilment and organizational citizenship behaviour. Manag. Organ. Rev. 7, 125–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2010.00202.x

Siyal, A. W., Donghong, D., Umrani, W. A., Siyal, S., and Bhand, S. (2019). Predicting mobile banking acceptance and loyalty in Chinese bank customers. SAGE Open 9:215824401984408. doi: 10.1177/2158244019844084

SMEDA (2005). Textile Vision 2005. Pakistan: Small and Medium Enterprise Development Authority. Available at: https://smeda.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=47&Itemid=150.

SMEDA (2007). “SME Policy,” in SME Led Economic Growth - Creating Jobs and Reducing Poverty. Pakistan. Available at: https://smeda.org/phocadownload/sme_policy_2007.pdf

SMEDA (2008–2009). “SME Baseline Survey 2009,” Small and Medium Enterprise Development Authority. Pakistan. Available at: https://smeda.org/phocadownload/Publicatoins/SME%20Baseline%20Survey.pdf.

Smith, C. A., Dennis, W. O., and Janet, P. N. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 68, 453–463.

Soumyaja, D., and Kamalanabhan, T. (2022). A study on executives’ self–other rater agreement on HEXACO personality and OCB. Manage. Labour Stud. 47, 319–332. doi: 10.1177/0258042X221082835

Star, T. (2020). Malaysia 5.0 for SMEs. Availabe at: www.thestar.com.my/opinion/letters/2020/06/22/malaysia-50-for-smes

Stringer, C., Didham, J., and Theivananthampillai, P. (2011). Motivation, pay satisfaction, and job satisfaction of front-line employees. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 8, 161–179. doi: 10.1108/11766091111137564

Sturges, J., Guest, D., Conway, N., and Davey, K. M. (2002). A longitudinal study of the relationship between career management and organizational commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work. J. Organizational Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organizational Psychol. Behav. 23, 731–748. doi: 10.1002/job.164

Sullivan, S. E., and Baruch, Y. (2009). Advances in career theory and research: a critical review and agenda for future exploration. J. Manag. 35, 1542–1571. doi: 10.1177/0149206309350082

Sultana, R., and Malik, O. F. (2019). Is protean career attitude beneficial for both employees and organizations? Investigating the mediating effects of knowing career competencies. Front. Psychol. 10:1284. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01284

Sun, L.-Y., Aryee, S., and Law, K. S. (2007). High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: a relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 558–577. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.25525821

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., and Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics. Pearson, Boston, MA.

Tschopp, C., Grote, G., and Gerber, M. (2014). How career orientation shapes the job satisfaction–turnover intention link. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 151–171. doi: 10.1002/job.1857

Tziner, A. (1987). Congruency issue retested using Fineman's achievement climate notion. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2:63.

Umrani, W. A., Channa, N. A., Yousaf, A., Ahmed, U., Pahi, M. H., and Ramayah, T. (2020). Greening the workforce to achieve environmental performance in hotel industry: a serial mediation model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 44, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.05.007

Umrani, W. A., Kura, K. M., and Ahmed, U. (2018). Corporate entrepreneurship and business performance: the moderating role of organizational culture in selected banks in Pakistan. PSU research. Review 2, 59–80. doi: 10.1108/PRR-12-2016-0011

Valcour, M., and Ladge, J. J. (2008). Family and career path characteristics as predictors of women’s objective and subjective career success: integrating traditional and protean career explanations. J. Vocat. Behav. 73, 300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.06.002

Verquer, M. L., Beehr, T. A., and Wagner, S. H. (2003). A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 63, 473–489. doi: 10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00036-2

Veskaisri, K., Chan, P., and Pollard, D. (2007). Relationship between strategic planning and SME success: empirical evidence from Thailand. Asia Pacific DSI, 1–13.

Volmer, J., and Spurk, D. (2011). Protean and boundaryless career attitudes: relationships with subjective and objective career success. Z. Arbeitsmarktforsch. 43, 207–218. doi: 10.1007/s12651-010-0037-3

Waters, L., Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., and Wang, L. (2014). Protean career attitudes during unemployment and reemployment: a longitudinal perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 84, 405–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.03.003

Waters, L., Hall, D. T., Wang, L., and Briscoe, J. P. (2015). “Protean career orientation: A review of existing and emerging research,” in Flourishing in Life, Work and Careers. eds. R. J. Burke, K. M. Page, and C. Cooper (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Welbourne, T. M., Johnson, D. E., and Erez, A. (1998). The role-based performance scale: validity analysis of a theory-based measure. Acad. Manag. J. 41, 540–555.

Weng, Q., and McElroy, J. C. (2010). HR environment and regional attraction: an empirical study of industrial clusters in China. Aust. J. Manag. 35, 245–263. doi: 10.1177/0312896210384679

Williams, L. J., and Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 17, 601–617. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700305

Zafar, Z., Wenyuan, L., Sulaiman, M. A. B. A., Siddiqui, K. A., and Qalati, S. A. (2021). Social entrepreneurship orientation and Enterprise fortune: an intermediary role of social performance. Front. Psychol. 12:755080. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.755080

Keywords: value-driven career attitude, protean career attitude, job performance, organizational citizenship behavior, small and medium enterprises

Citation: Iqbal MB, Li J, Yang S and Sindhu P (2022) Value-driven career attitude and job performance: An intermediary role of organizational citizenship behavior. Front. Psychol. 13:1038832. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1038832

Edited by:

Rana Yassir Hussain, University of Education Lahore, PakistanReviewed by:

Rashid Mehmood, University of Education Lahore, PakistanBilal Ahmed, Zhejiang University of Technology, China

Copyright © 2022 Iqbal, Li, Yang and Sindhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Babar Iqbal, YmFiYXJpcWJhbEBzdHUueGF1dC5lZHUuY24=

Muhammad Babar Iqbal

Muhammad Babar Iqbal Jianxun Li1

Jianxun Li1