- 1School of Educational Science, Ludong University, Yantai, China

- 2Institute for Education and Treatment of Problematic Youth, Ludong University, Yantai, China

- 3School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Binzhou Medical University, Yantai, China

Childhood abuse has been shown to have a range of adverse physical and psychological consequences, including aggression and bullying. While researchers have explored the relationship between childhood abuse and cyberbullying, little is known about the impact of emotional abuse on cyberbullying. This study examined the link between childhood emotional abuse (CEA) and cyberbullying perpetration among university students in the Chinese cultural context, as well as the chain mediating effect of self-esteem and Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU). A total of 835 university students (18–25 years old; 293 males, 542 females; Mage = 19.44 years, SD = 1.28) completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short-Form (CTQ-SF), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), the Social Media Use Questionnaire (SMUQ), and Cyberbullying Inventory (CBI). The results showed that CEA and PSMU were positively correlated with cyberbullying; self-esteem was negatively correlated with cyberbullying. Besides, self-esteem and PSMU sequentially mediated the relationship between CEA and cyberbullying perpetration. The findings indicate that childhood emotional abuse may lower self-esteem and cause problematic social media use, which increases cyberbullying perpetration.

Introduction

By the end of 2021, the number of Chinese Internet users was 1.032 billion, of which the Internet penetration rate reached 73%, and the proportion of online surfing with mobile phones was up to 99.7% [China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2022]. With the popularity of the Internet, cyberbullying has become a global phenomenon and an increasingly severe social issue. Cyberbullying perpetration is usually defined as “using electronic forms of contact to repeatedly and intentionally harm a victim who cannot defend him or herself.” (Smith et al., 2008), including various behaviors, such as harassment, denigration, masquerade, flaming, and cyberstalking (Smith, 2015). Cyberbullying differs from traditional school bullying in its anonymity, fast spreading, and uncontrollability, which may cause more critical consequences and adverse psychophysiological effects on victims.

The prevalence of cyberbullying varies in different studies due to different definitions and measurement methods (Brochado et al., 2017; Kowalski et al., 2019; Chen and Chen, 2020; Barlett et al., 2021; Eyuboglu et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021; Fulantelli et al., 2022). A systematic review showed that the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization among East Asian adolescents ranged from 5.8 to 56.8%, and the rate of bullying was lower than victimization (Park, M. S. et al., 2021). A study in EU member countries showed that the rate of victimization ranged from 2.8 to 31.5%, from 3.0 to 30.6% of cyber perpetration (Henares-Montiel et al., 2022). Several studies have revealed that cyberbullying may lead to anxiety, depression, loneliness, social withdrawal, substance abuse, self-harm, and suicidality (Kwan et al., 2020; Giumetti et al., 2021; Chu et al., 2022; Coelho et al., 2022; Pichel et al., 2022). However, much previous research focused on teenagers, and relatively few studies were conducted on university students. Therefore, this study will explore the influencing factors and internal mechanisms of university students’ cyberbullying perpetration to provide empirical support for scientific intervention.

Childhood emotional abuse (CEA) occurs independently of other types of childhood maltreatment (Glaser, 2002) and refers to non-physical, long-term, and harmful interactions between caregivers and children, including verbal aggression, humiliation, blaming, demeaning, or other behaviors (Glaser, 2011; Li et al., 2022). It is noticeable that childhood emotional abuse, which is more devastating than physical and sexual abuse and has potentially lifelong adverse effects, is often overlooked because there is no physical evidence of it (Rees, 2010; Dye, 2020). Studies in different countries and regions have shown high rates of CEA (Chandraratne et al., 2018; Prino et al., 2018). In a recent survey from Hong Kong, 43.3% of participants reported they had suffered emotional abuse during childhood (Fung et al., 2020).

Childhood emotional abuse is a risk factor for aggressive behavior (Wang et al., 2019a). According to the cycle of violence hypothesis, chronically abused victims in childhood are at greater risk of violence in adolescence and early adulthood (Wright et al., 2019) and are more likely to bully peers (Wang et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2021; Park, J. et al., 2021). Recent evidence suggests that childhood abuse can significantly positively predict cyberbullying (Wang et al., 2019b; Jin et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). Two recent studies in Western society have revealed a strong link between CEA and high cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents (Kircaburun et al., 2019; Emirtekin et al., 2020).

Based on previous studies, we consider that CEA is closely related to cyberbullying among university students. However, not all individuals who have suffered from domestic violence will exhibit violent behaviors. Further research is needed to elucidate the mediating or moderating mechanisms in the above relationships.

According to the self-system model (Connell and Wellborn, 1991; Skinner and Wellborn, 1994; Sandler, 2001), self-model is self-representation, which refers to the positive and negative evaluation of individuals. Typical self-evaluations include self-esteem and self-efficacy. Self-esteem refers to an individual’s positive or negative evaluations of the global perception of self. Childhood adversity, including family maltreatment, can lead to severe disruption of self-system processes (e.g., self-esteem). From the perspective of attachment theory (Riggs and Kaminski, 2010), self-esteem generates from integrating the attitudes and evaluations of others (e.g., parents and other caregivers) toward the self. Children who grow up in an abusive environment do not get the necessary support and affirmation to develop a sense of self-worth.

Previous studies have also confirmed the negative correlation between childhood abuse and self-esteem (Arslan, 2016; Lim and Lee, 2017; Luo et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022). CEA, a part of childhood abuse, can also cause low self-esteem (Chen and Qin, 2020), which may lead to a range of emotional and behavioral problems, resulting in psychological and social maladjustment (Arslan, 2016; Lim and Lee, 2017). Several studies have reported that low self-esteem is associated with high cyberbullying (Brewer and Kerslake, 2015; Fan et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021).

Recent evidence has demonstrated the mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between adversity and problem behavior in children and adolescents. We believe that inappropriate parenting (e.g., CEA) will lead to low self-esteem, and low self-esteem may exhibit aggressive behaviors to avoid inferiority and shame caused by failure (Tracy and Robins, 2003).

Social media are fertile ground for cyberbullying perpetration (Chan et al., 2021). Some researchers have mentioned that Twitter and Facebook are two main social media platforms with the highest occurrence of online bullying (Whittaker and Kowalski, 2015). Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU) refers to an over concern and powerful motivation to engage in social media (Andreassen et al., 2016), relevant signs include overuse on social media platforms, log in or check social software frequently, irritability, or anxiety when not being able to access social media (Chen et al., 2020). Numerous research has indicated that PSMU is an important predictor of online aggression and cyberbullying (Görzig and Frumkin, 2013; Barlett et al., 2018; Craig et al., 2020; Marengo et al., 2021; Borraccino et al., 2022; Giumetti and Kowalski, 2022).

Problematic Social Media Use is influenced by many factors. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model explains that problematic Internet use (e.g., social media addiction) is the result of the interaction of a person, affect, cognition, and execution (Brand et al., 2016, 2019). Specifically, a person’s core characteristics are the susceptibility variables to behavior addiction, including bio-psychological factors (such as genes and early adverse experiences), psychopathological correlates (depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), and personality traits (e.g., high impulsivity, low self-esteem, and high neuroticism). Existing studies have confirmed the link between high abuse and PSMU (Worsley et al., 2018; Kircaburun et al., 2020), as well as low self-esteem and PSMU (Saiphoo et al., 2020; Schivinski et al., 2020).

Early traumatic experiences can be internalized in the evaluation of oneself and others, which could cause damage to self-esteem. Moreover, people with lower self-esteem are sensitive to interpersonal relationships and depend on social network to establish social relationships, leading to the intemperate use of social media and ultimately increasing the risk of cyberbullying. Therefore, high emotional abuse may lead to low self-esteem and PSMU in undergraduates, which in turn causes cyberbullying perpetration.

Given all the above, the current study aims to construct a chain mediation model to test the effects of self-esteem and PSMU. Based on the existing theories and empirical research, we put forward four specific hypotheses:

H1: CEA would positively predict cyberbullying perpetration among university students.

H2: Self-esteem plays a mediating role in the relationship between CEA and cyberbullying perpetration.

H3: PSMU might be a mediator in the relationship between CEA and cyberbullying perpetration.

H4: Self-esteem and PSMU together play a chain mediating role in the relationship between CEA and cyberbullying perpetration.

Materials and methods

Participants

Using the cluster random sampling method, 865 students from a university in Shandong province were selected as the research objects. 30 invalid questionnaires were removed, and the remaining 835 questionnaires were valid. Among the participants, there were 293 (35.1%) male students and 542 (64.9%) female students. 416 (49.8%) were freshmen, 246 (29.5%) were sophomores, and 173 (20.7%) were juniors. 308(36.9%) came from an urban area and 527(63.1%) came from a rural area. The age ranged from 18 to 25 years (M = 19.44, SD = 1.28).

Measures

Childhood emotional abuse

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short-Form (CTQ-SF) developed by Bernstein et al. (1997, 2003) and revised by Zhao et al. (2005), measures abuse and neglect before the age of 16 years old. It includes five subscales: physical abuse (PA), emotional abuse (EA), sexual abuse (SA), emotional neglect (EN), and physical neglect (PN). Each subscale consists of five items, plus three validity items for a total of 28 items. We used the EA subscale (Chen et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020). The CTQ-SF is scored on a five-point scale (1 = never; 5 = always), with higher scores indicating higher levels of EA. The Cronbach’s α of EA in the current study was 0.70.

Self-esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965; Wang et al., 1999) was used to measure the level of self-esteem. It consists of 10 items, each item is rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-esteem. In this research, the Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

Problematic social media use

The Social Media Use Questionnaire (SMUQ), developed by Xanidis and Brignell (2016), assesses the problematic use of social media. The SMUQ has nine items and consists of two dimensions: withdrawal and compulsion. Participants rated each item on a five-point scale (0 = never; 4 = always). Cronbach’s α was 0.80 in the current study.

Cyberbullying perpetration

Cyberbullying Inventory (CBI; Erdur-Baker and Kavsut, 2007) was used to test the level of cyberbullying perpetration. The CBI has 18 items. Participants rated each item on a four-point scale (1 = never happened; 2 = happened once or twice; 3 = happened 3–5 times; and 4 = happened more than five times). Higher scores indicate serious state of cyberbullying perpetration. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.80.

Procedure and statistical analysis

We choose students’ self-study time to conduct a collective test of the class. To ensure data quality, the first author, familiar with the study, served as the experimenter for each class. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University. To control the common method bias (CMB), we used procedural remedies and statistical remedies. The questionnaire included some reverse scoring items. Besides, the participants were told that the survey would be conducted anonymously, only for scientific research, and voluntarily.

In addition, we used a statistical test—the Harman single factor test to analyze the common method bias. The results showed that there were 10 factors with eigenvalues >1, and the first factor accounted for 16.12% variance, which is less than the 40% threshold. SPSS 26.0 and SPSS macro PROCESS model 6 (Hayes, 2013) were used for correlation analysis and chain intermediary effect test.

Results

Correlation analysis among variables

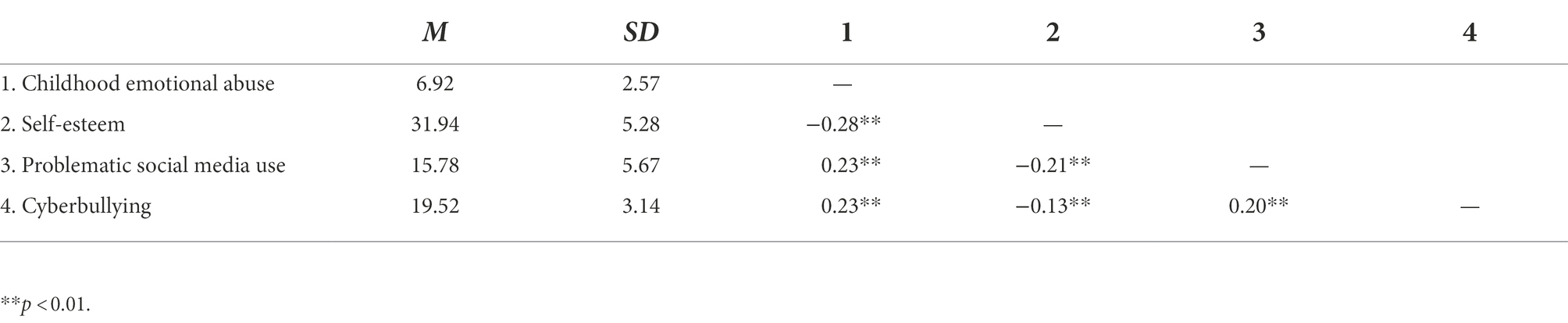

The mean, standard deviation, and correlation matrix of each variable are shown in Table 1. The results showed that CEA (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), PSMU (r = 0.20, p < 0.01), and cyberbullying were significantly positively correlated, while self-esteem and cyberbullying were negatively correlated (r = −0.13, p < 0.01). Additionally, there was a significant positive correlation between CEA and PSMU (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), and a significant negative correlation between CEA and self-esteem (r = −0.28, p < 0.01) and PSMU and self-esteem (r = −0.21, p < 0.01).

Mediation of self-esteem and problematic social media Use

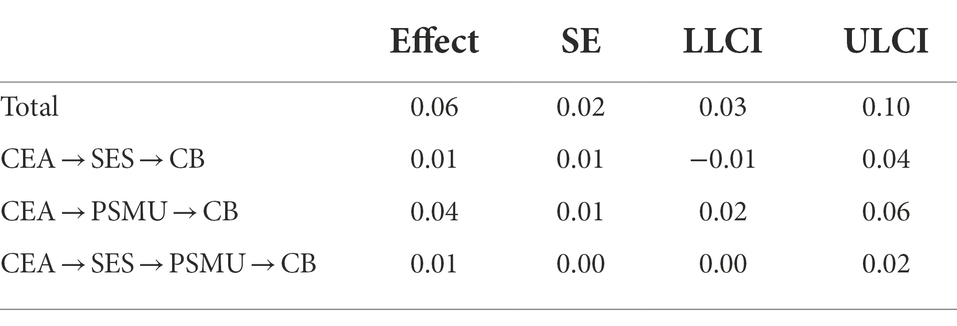

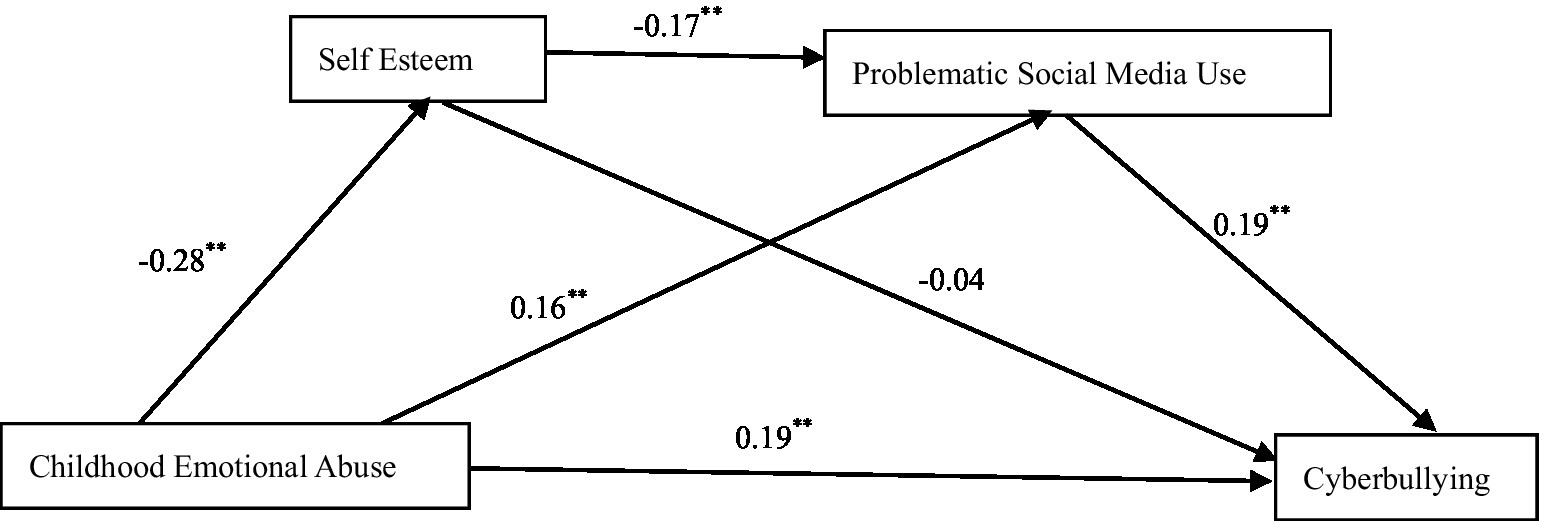

Using PROCESS Model 6 to test the chain mediation effect. CEA was used as a predictor variable, cyberbullying as a dependent variable, self-esteem and PSMU as mediating variables, and gender as a control variable. As shown in Figure 1, CEA negatively predicted self-esteem (β = −0.28, p < 0.01) and positively predicted PSMU (β = 0.16, p < 0.01) and cyberbullying (β = 0.19, p < 0.01). Self-esteem negatively predicted PSMU (β = −0.17, p < 0.01), but it had no significant predictive effect on cyberbullying (β = −0.04, p > 0.05). PSMU positively predicted cyberbullying (β = 0.19, p < 0.01). The results of Bootstrap mediation test are shown in Table 2. The mediating effect of self-esteem is not significant, and the 95% CI [−0.01, 0.04] includes 0. The mediating effect of PSMU was significant, with 95% CI [0.02, 0.06], and the mediating effect accounted for 12.2% of the total effect. The chain mediating effect of self-esteem and PSMU was also significant, with 95% CI [0.00, 0.02], and the mediating effect accounted for 3.72% of the total effect.

Figure 1. Model of the chained mediating effect of self-esteem and problematic social media use. **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Although the effect of childhood maltreatment on cyberbullying has acquired considerable empirical support (Wang et al., 2019b; Jin et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022), less is known about the potential mediating mechanisms. Based on a sample of 835 Chinese university students, we constructed a chain mediated model, and the results proved the chain mediating effect of self-esteem and social media use in the above relationship.

As expected (H1), CEA was positively associated with cyberbullying perpetration, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (Kircaburun et al., 2019; Emirtekin et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). Undergraduates with emotional maltreated experiences are more susceptible to bullying others online. The results support the cycle of violence hypothesis that violence in adulthood can be explained by early abuse. Children who live with violent parents for a long time will inherit violent ways to solve problems, creating a terrible cycle of violence. Based on the results of this study and previous studies, we believe that CEA is a critical risk factor for cyberbullying perpetration.

Attachment theory demonstrates that children constantly insulted, terrorized, disparaged, and despised by parents will believe they are worthless, unloved, and unlovable, which seriously affects their formation of correct self-cognition and results in lower self-evaluation. The results showed a negative effect of CEA on self-esteem, which also accords with the earlier observations (Arslan, 2016; Chen et al., 2022). However, when PSMU was added, the predictive effect of self-esteem on cyberbullying was no longer significant, and the path of CEA → self-esteem → cyberbullying was not significant, which is inconsistent with hypothesis 2. This result is similar to previous studies (Xin et al., 2007; Cao and Zhang, 2018). When other variables are added, the direct predictive effect of self-esteem on aggressive behavior becomes no longer significant. Low self-esteem caused by CEA does not necessarily trigger online bullying, though, in the most simple binary relation, our result showed the negative relationship between self-esteem and cyberbullying, but in the background of multivariate context and within the group of university students, the relationship between the above two is likely to be influenced by the third variable, this study also proved it.

In line with Hypothesis 3, PSMU mediated the relationship between CEA and cyberbullying perpetration. Emotional abuse can significantly and positively predict problematic Internet use and social media use, consistent with existing research findings (Dalbudak et al., 2014; Schimmenti et al., 2014; Worsley et al., 2018; Kircaburun et al., 2020). Dalbudak et al. (2014) have found that the types of childhood abuse associated with increasing risk of Internet addiction were emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect, among which the emotional abuse was the most important predictor. In addition, Schimmenti et al. (2014) revealed that childhood sexual abuse was associated with a sevenfold increasing risk of problematic Internet use in adolescence. This may be a strategy for individuals who suffered adversity in childhood to cope with early adverse experiences through virtual worlds (Worsley et al., 2018). Frequent and problematic use of social media increases the likelihood of witnessing and imitating online attacks, causing negative consequences of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. However, PSMU is more strongly linked with cyberbullying perpetration (Craig et al., 2020). Thus, the mediating effect of PSMU was significant.

The current results also indicated that self-esteem and PSMU had a chain mediating effect on the relationship between emotional abuse and cyberbullying. CEA sequentially influences self-esteem and PSMU and eventually leads to cyberbullying among university students. Individuals exposed to parental maltreatment in childhood suffer from emotional trauma and unsatisfied psychological needs. They constantly receive and accumulate negative emotions and feedback from caregivers and gradually internalize negative evaluations of themselves with low self-worth and self-esteem. Moreover, to overcome the trauma caused by early adverse experiences, children and adolescents seek their positive values in social networks to obtain emotional satisfaction, which leads to the excessive use of social media and increases the chances of hurting others and being hurt by others. How does CEA influence cyberbullying among university students? Some researchers suggest that it is through dark personality traits (Kircaburun et al., 2019), while others consider it is through the chain mediating effect of hostile attribution bias and anger rumination (Li et al., 2022). Our results explain why CEA is associated with cyberbullying in terms of self-esteem and PSMU, supporting the I-PACE model and enriching our understanding of the relationship between early adverse experiences and cyberbullying perpetration.

This study confirms that CEA sequentially influences cyberbullying through self-esteem and PSMU in a Chinese cultural context. In the Chinese sample, low self-esteem caused by CEA does not necessarily lead to cyberbullying. It is the overuse of social media that results in the risk of cyberbullying. Whether this conclusion is applicable to other cultures remains to be further tested.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. Firstly, the cross-sectional design cannot provide evidence for causal relationships among variables, and longitudinal studies should be carried out in the future, which would be more conducive to understanding the impact of emotional abuse on cyberbullying. Secondly, self-report measures were used to collect data, while retrospective self-report is prone to biases. In addition, the sensitivity of abuse or cyberbullying is easily affected by social desirability bias. Thirdly, the samples were taken from undergraduates in China, and cyberbullying has cultural differences (Craig et al., 2020), so future research should conduct cross-cultural tests.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WX conducted the survey, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SZ designed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The work was supported by the Social Science Popularization and Application Research Project of Shandong Province (2022-SKZZ-02).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the school counselors and the participants who volunteered to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., et al. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 30, 252–262. doi: 10.1037/adb0000160

Arslan, G. (2016). Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: the mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse Negl. 52, 200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.010

Barlett, C. P., Gentile, D. A., Chng, G., Li, D., and Chamberlin, K. (2018). Social media use and cyberbullying perpetration: a longitudinal analysis. Violence Gend. 5, 191–197. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0047

Barlett, C. P., Seyfert, L. W., Simmers, M. M., Chen, V. H. H., Cavalcanti, J. G., Krahé, B., et al. (2021). Cross-cultural similarities and differences in the theoretical predictors of cyberbullying perpetration: results from a seven-country study. Aggress. Behav. 47, 111–119. doi: 10.1002/ab.21923

Bernstein, D. P., Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D., and Handelsman, L. (1997). Validity of the childhood trauma questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., and Ahluvalia, T. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 27, 169–190. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Borraccino, A., Marengo, N., Dalmasso, P., Marino, C., Ciardullo, S., Nardone, P., et al. (2022). Problematic social media use and cyber aggression in Italian adolescents: the remarkable role of social support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 19:9763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159763

Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., et al. (2019). The interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 104, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., and Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: an interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71, 252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Brewer, G., and Kerslake, J. (2015). Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 48, 255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.073

Brochado, S., Soares, S., and Fraga, S. (2017). A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma Viol. Abus. 18, 523–531. doi: 10.1177/1524838016641668

Cao, X., and Zhang, L. (2018). Chain mediating effect of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and self-control between self-esteem and aggressiveness in adolescents. Chin. Ment. Health J. 32, 574–579. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2018.07.007

Chan, T. K., Cheung, C. M., and Lee, Z. W. (2021). Cyberbullying on social networking sites: a literature review and future research directions. Inform. Manag. 58:103411. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2020.103411

Chandraratne, N. K., Fernando, A. D., and Gunawardena, N. (2018). Physical, sexual and emotional abuse during childhood: experiences of a sample of Sri Lankan Young adults. Child Abuse Negl. 81, 214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.004

Chen, J. K., and Chen, L. M. (2020). Cyberbullying among adolescents in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China: a cross-national study in Chinese societies. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 30, 227–241. doi: 10.1080/02185385.2020.1788978

Chen, L., Guo, H., Zhu, Q., Bu, Y., and Lin, D. (2016). Emotional abuse and depressive symptoms in children: the mediating of emotion regulation. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 24, 1042–1050. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.06.017

Chen, C., Ji, S., and Jiang, J. (2022). Psychological abuse and social support in Chinese adolescents: the mediating effect of self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 13:852256. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.852256

Chen, I. H., Pakpour, A. H., Leung, H., Potenza, M. N., Su, J. A., Lin, C. Y., et al. (2020). Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. J. Behav. Addict. 9, 410–419. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00023

Chen, C., and Qin, J. (2020). Emotional abuse and adolescents’ social anxiety: the roles of self-esteem and loneliness. J. Fam. Violence 35, 497–507. doi: 10.1007/s10896-019-00099-3

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2022). The 49th China internet development statistics report. Available at: http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202202/t20220225_71727.htm (Accessed February 25, 2022).

Chu, X., Yang, S., Sun, Z., Jiang, M., and Xie, R. (2022). The association between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation among Chinese college students: the parallel mediating roles of core self-evaluation and depression. Front. Psychol. 13:929679. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.929679

Coelho, V. A., Marchante, M., and Romão, A. M. (2022). Adolescents’ trajectories of social anxiety and social withdrawal: are they influenced by traditional bullying and cyberbullying roles? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 69:102053. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102053

Connell, J. P., and Wellborn, J. G. (1991). “Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: a motivational analysis of self-system processes,” in Self Processes and Development. eds. M. R. Gunnar and L. A. Sroufe (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Press), 43–77.

Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S. D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P. D., et al. (2020). Social media use and cyber-bullying: a cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 66, S100–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.006

Dalbudak, E., Evren, C., Aldemir, S., and Evren, B. (2014). The severity of internet addiction risk and its relationship with the severity of borderline personality features, childhood traumas, dissociative experiences depression and anxiety symptoms among Turkish university students. Psychiatry Res. 219, 577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.032

Dye, H. L. (2020). Is emotional abuse as harmful as physical and/or sexual abuse? J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 13, 399–407. doi: 10.1007/s40653-019-00292-y

Emirtekin, E., Balta, S., Kircaburun, K., and Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Childhood emotional abuse and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: the mediating role of trait mindfulness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 18, 1548–1559. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-0055-5

Erdur-Baker, O., and Kavsut, F. (2007). Cyber bullying: a new face of peer bullying. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 7, 31–42.

Eyuboglu, M., Eyuboglu, D., Pala, S. C., Oktar, D., Demirtas, Z., Arslantas, D., et al. (2021). Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Res. 297:113730. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113730

Fan, C., Chu, X., Zhang, M., and Zhou, Z. (2019). Are narcissists more likely to be involved in cyberbullying? Examining the mediating role of self-esteem. J. Interpers. Viol. 34, 3127–3150. doi: 10.1177/0886260516666531

Fang, J., Wang, W., Gao, L., Yang, J., Wang, X., Wang, P., et al. (2022). Childhood maltreatment and adolescent cyberbullying perpetration: a moderated mediation model of callous unemotional traits and perceived social support. J. Interpers. Viol. 37, NP5026–NP5049. doi: 10.1177/0886260520960106

Fulantelli, G., Taibi, D., Scifo, L., Schwarze, V., and Eimler, S. C. (2022). Cyberbullying and cyberhate as two interlinked instances of cyber-aggression in adolescence: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 13:909299. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.909299

Fung, H. W., Chung, H. M., and Ross, C. A. (2020). Demographic and mental health correlates of childhood emotional abuse and neglect in a Hong Kong sample. Child Abuse Negl. 99:104288. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104288

Giumetti, G. W., and Kowalski, R. M. (2022). Cyberbullying via social media and well-being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 45:101314. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101314

Giumetti, G. W., Kowalski, R. M., and Feinn, R. S. (2021). Predictors and outcomes of cyberbullying among college students: a two wave study. Aggress. Behav. 48, 40–54. doi: 10.1002/ab.21992

Glaser, D. (2002). Emotional abuse and neglect (psychological maltreatment): a conceptual framework. Child Abuse Negl. 26, 697–714. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00342-3

Glaser, D. (2011). How to deal with emotional abuse and neglect—further development of a conceptual framework (FRAMEA). Child Abuse Negl. 35, 866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.002

Görzig, A., and Frumkin, L. A. (2013). Cyberbullying experiences on-the-go: when social media can become distressing. Cyberpsychology 7:4. doi: 10.5817/CP2013-1-4

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. J. Educ. Meas. 51, 335–337. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050

Henares-Montiel, J., Benítez-Hidalgo, V., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Pastor-Moreno, G., and Rodríguez-Barranco, M. (2022). Cyberbullying and associated factors in member countries of the European Union: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies with representative population samples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 19:7364. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127364

Jin, T., Wu, Y., Zhang, L., Li, X., and Liu, Z. (2020). Childhood psychological maltreatment and cyberbullying among Chinese adolescents: the moderating roles of perceived social support and gender. J. Psychol. Sci. 43, 323–332. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200210

Kircaburun, K., Griffiths, M. D., and Billieux, J. (2020). Childhood emotional maltreatment and problematic social media use among adolescents: the mediating role of body image dissatisfaction. Int. J. Ment. Health 18, 1536–1547. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-0054-6

Kircaburun, K., Jonason, P., Griffiths, M. D., Aslanargun, E., Emirtekin, E., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., et al. (2019). Childhood emotional abuse and cyberbullying perpetration: the role of dark personality traits. J. Interpers. Viol. 36, NP11877–NP11893. doi: 10.1177/0886260519889930

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., and McCord, A. (2019). A developmental approach to cyberbullying: prevalence and protective factors. Aggress. Violent Behav. 45, 20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.009

Kwan, I., Dickson, K., Richardson, M., Macdowall, W., Burchett, H., Stansfield, C., et al. (2020). Cyberbullying and children and young people's mental health: a systematic map of systematic reviews. Cyberpsych. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 72–82. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0370

Li, M., He, Q., Zhao, J., Xu, Z., and Yang, H. (2022). The effects of childhood maltreatment on cyberbullying in college students: the roles of cognitive processes. Acta Psychol. 226:103588. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103588

Li, W., Zhang, Q., Liu, S., and Wang, Z. (2020). Comparison of the influence mechanism of parental childhood emotional abuse on toddler’s problem behavior. J. Psychol. Sci. 43, 593–599. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200312

Lim, Y., and Lee, O. (2017). Relationships between parental maltreatment and adolescents’ school adjustment: mediating roles of self-esteem and peer attachment. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 393–404. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0573-8

Luo, S., Liu, Y., and Zhang, D. (2020). Psychological maltreatment and loneliness in Chinese children: the role of perceived social support and self-esteem. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 108:104573. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104573

Marengo, N., Borraccino, A., Charrier, L., Berchialla, P., Dalmasso, P., Caputo, M., et al. (2021). Cyberbullying and problematic social media use: an insight into the positive role of social support in adolescents—data from the health behaviour in school-aged children study in Italy. Public Health 199, 46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.010

Park, M. S., Golden, K. J., Vizcaino-Vickers, S., Jidong, D., and Raj, S. (2021). Sociocultural values, attitudes and risk factors associated with adolescent cyberbullying in East Asia: a systematic review. Cyberpsychology 15:5. doi: 10.5817/CP2021-1-5

Park, J., Grogan-Kaylor, A., and Han, Y. (2021). Trajectories of childhood maltreatment and bullying of adolescents in South Korea. J. Child Fam. Stud. 30, 1059–1070. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01913-7

Pichel, R., Feijóo, S., Isorna, M., Varela, J., and Rial, A. (2022). Analysis of the relationship between school bullying, cyberbullying, and substance use. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 134:106369. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106369

Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., and Settanni, M. (2018). Young adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: prevalence of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse in Italy. Arch. Sex. Behav. 47, 1769–1778. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1154-2

Rees, C. A. (2010). Understanding emotional abuse. Arch. Dis. Child. 95, 59–67. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.143156

Riggs, S. A., and Kaminski, P. (2010). Childhood emotional abuse, adult attachment, and depression as predictors of relational adjustment and psychological aggression. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 19, 75–104. doi: 10.1080/10926770903475976

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Saiphoo, A. N., Halevi, L. D., and Vahedi, Z. (2020). Social networking site use and self-esteem: a meta-analytic review. Pers. Individ. Differ. 153:109639. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109639

Sandler, I. (2001). Quality and ecology of adversity as common mechanisms of risk and resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 29, 19–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1005237110505

Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., Gervasi, A. M., Manzella, S., and Famà, F. I. (2014). Insecure attachment attitudes in the onset of problematic internet use among late adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 45, 588–595. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0428-0

Schivinski, B., Brzozowska-Woś, M., Stansbury, E., Satel, J., Montag, C., and Pontes, H. M. (2020). Exploring the role of social media use motives, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and affect in problematic social media use. Front. Psychol. 11:617140. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617140

Skinner, E., and Wellborn, J. G. (1994). “Coping during childhood and adolescence: a motivational perspective,” in Life-Span Development and Behavior. eds. D. Featherman, R. Lerner, and M. Perlmutter (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Press), 91–133.

Smith, P. K. (2015). The nature of cyberbullying and what we can do about it. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 15, 176–184. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12114

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., and Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 49, 376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Tracy, J. L., and Robins, R. W. (2003). “Death of a (narcissistic) salesman:” an integrative model of fragile self-esteem. Psychol. Inq. 14, 57–62.

Wang, Q., Shi, W., and Jin, G. (2019a). Effect of childhood emotional abuse on aggressive behavior: a moderated mediation model. J. Aggress. Maltreat. 28, 929–942. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1498962

Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., and Ma, H. (1999). Handbook of Mental Health Assessment Scale. Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Journal Press

Wang, X., Yang, L., Gao, L., Yang, J., and Lei, L., and Wang, C. (2017). Childhood maltreatment and Chinese adolescents’ bullying and defending: the mediating role of moral disengagement. Child Abuse Negl. 69, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.016

Wang, X., Yang, J., Wang, P., and Lei, L. (2019b). Childhood maltreatment, moral disengagement, and adolescents' cyberbullying perpetration: fathers' and mothers' moral disengagement as moderators. Comput. Hum. Behav. 95, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.031

Whittaker, E., and Kowalski, R. M. (2015). Cyberbullying via social media. J. Sch. Violence 14, 11–29. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2014.949377

Worsley, J. D., McIntyre, J. C., Bentall, R. P., and Corcoran, R. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and problematic social media use: the role of attachment and depression. Psychiatry Res. 267, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.023

Wright, K. A., Turanovic, J. J., O’Neal, E. N., Morse, S. J., and Booth, E. T. (2019). The cycle of violence revisited: childhood victimization, resilience, and future violence. J. Interpers. Viol. 34, 1261–1286. doi: 10.1177/0886260516651090

Xanidis, N., and Brignell, C. M. (2016). The association between the use of social network sites, sleep quality and cognitive function during the day. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.004

Xiao, Y., Jiang, L., Yang, R., Ran, H., Wang, T., He, X., et al. (2021). Childhood maltreatment with school bullying behaviors in Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 281, 941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.022

Xin, Z., Guo, S., and Chi, L. (2007). The relationship of adolescent’s self-esteem and aggression: the role of mediator and moderator. Acta Psychol. Sin. 39, 845–851.

Yang, J., Wang, N., Gao, L., and Wang, X. (2021). Childhood maltreatment and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: the roles of self-esteem and friendship quality. J. Psychol. Sci. 44, 74–81. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20210111

Zhao, X. F., Zhang, Y. L., Li, L. F., Zhou, Y. F., and Yang, S. C. (2005). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chin. J. Clin. Rehabil. 9, 105–107.

Keywords: childhood emotional abuse, cyberbullying perpetration, self-esteem, problematic social media use, university students

Citation: Xu W and Zheng S (2022) Childhood emotional abuse and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese university students: The chain mediating effects of self-esteem and problematic social media use. Front. Psychol. 13:1036128. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1036128

Edited by:

Sebastian Wachs, University of Potsdam, GermanyReviewed by:

Reyes López López, University of Murcia, SpainJie Li, Inner Mongolia Normal University, China

Qingqing Ye, Zhengzhou University, China

Copyright © 2022 Xu and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shujie Zheng, c2h1amllemhlbmdAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Wei Xu

Wei Xu Shujie Zheng

Shujie Zheng