- 1Psychosocial Research and Epidemiology Department, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Department of Medical Oncology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3Department of Neurology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 4Department of Public Health, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 5Department of Medical Oncology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 6Internal Medicine, Division Medical Oncology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands

- 7GROW-School of Oncology and Reproduction, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands

- 8AYA Research Partner, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 9Department of Surgical Oncology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 10Division of Clinical Studies, Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Adolescents and young adults with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis (UPCP) are confronted with ongoing and unique age-specific challenges, which forms an enormous burden. To date, little is known about the way AYAs living with a UPCP cope with their situation. Therefore, this study explores how AYAs with a UPCP cope with the daily challenges of their disease.

Method: We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews among AYAs with a UPCP. Patients of the three AYA subgroups were interviewed (traditional survivors, new survivors, low-grade glioma survivors), since we expected different coping strategies among these subgroups. Interviews were analyzed using elements of the Grounded Theory by Corbin and Strauss. AYA patients were actively involved as research partners.

Results: In total 46 AYAs with UPCP participated, they were on average 33.4 years old (age range 23–44) and most of them were woman (63%). Most common tumor types were low-grade gliomas (16), sarcomas (7), breast cancers (6) and lung cancers (6). We identified seven coping strategies in order to reduce the suffering from the experienced challenges: (1) minimizing impact of cancer, (2) taking and seeking control, (3) coming to terms, (4) being positive, (5) seeking and receiving support, (6) carpe diem and (7) being consciously alive.

Conclusion: This study found seven coping strategies around the concept of ‘double awareness’ and showcases that AYAs are able to actively cope with their disease but prefer to actively choose life over illness. The findings call for CALM therapy and informal AYA support meetings to support this group to cope well with their disease.

Background

Patients diagnosed with advanced cancer have to cope with a complex array of factors, including prolonged treatments, life-long side effects and a poor life perspective. These factors might be even more complicated in adolescents and young adults (AYAs; aged 18–39 years at primary cancer diagnosis) with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis (UPCP). Most AYAs have not yet reached all milestones of an adult life and have less life experience to deal with their uncertain cancer diagnosis (García-Rueda et al., 2016; Bradford et al., 2022). A recent study shows that AYAs with a UPCP are confronted with ongoing and unique age-specific challenges, such as feeling inferior to previous self and others, sense of grief about life and not being able to make life plans (Burgers et al., 2022). This forms a tremendous burden and major life disruption for this young vulnerable patient group (Burgers et al., 2021, 2022). Given the “life-threatening” situation, that will likely not change during the rest of their lives, this group of AYAs must find a way to deal with cancer and its consequences for often a relatively long period.

While there is a growing body of research focusing on AYAs with advanced cancer, the current literature on how AYAs cope with cancer is mainly about older adult patients, patients with a relatively good prognosis or patients coping with nearing death. A recent study of Bradford et al. (2022), regarding AYAs with advanced cancer suggests that coping is a dynamic process where different strategies are used depending on the stressor, available resources and previous experiences. Earlier research on AYAs or adult patients with advanced cancer found acceptance, positive attitude by making comparisons with people in worse situations and setting realistic goals, keeping hope and support seeking as the most commonly used coping strategies (Trevino et al., 2012; Lobb et al., 2015; García-Rueda et al., 2016; Walshe et al., 2017; Lie et al., 2018; Bradford et al., 2022). Arantzamendi et al. (2020) redefined the theory of “living well with chronic illness” to explain the experience of living with advanced cancer. This new model involves an iterative process of struggling, accepting, living with advanced cancer, sharing the illness experience and reconstructing life, that occurs as the disease condition or the response to it change and people have to develop new ways to live well.

This redefined theory suggests that it might be possible to live well with cancer, but it requires deep engagement, time and effort (Arantzamendi et al., 2020). Up to now, little is known about the way AYAs living with a UCPC cope with their situation. Awareness of how these young people cope with daily challenges related to their UPCP is essential to understand how to improve the current care to empower young persons by strengthening individual coping styles and enhancing resources, with the ultimate goal to improve their quality of life. Therefore, this study explores how AYAs with a UPCP cope with the daily challenges of their disease.

Materials and methods

This study presents a secondary analysis, a more detailed description of the methods can be found in Burgers et al. (2022). The Consolidation Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies guideline was followed to guarantee quality and transparency of reporting (Tong et al., 2007; Supplementary material 1).

Participants

Patients were recruited from eight University Medical Centers in Netherlands, the Netherlands Cancer Institute and Haaglanden Medical Center. Eligible patients included those (1) diagnosed with any type of advanced cancer for the first time between 18 and 39 years of age, for which there is no reasonable hope of cure, indicating that the patient will die prematurely due to cancer, and (2) able to speak and understand Dutch. Patients with terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than three to 6 months and a poor performance status were excluded. Participating AYAs were classified into three groups based on received treatment and prognosis (Burgers et al., 2021). The three subgroups are: (1) AYAs treated with standard treatment(s) (mainly chemotherapy; traditional survivors); (2) AYAs undergoing novel treatment(s) (targeted therapy and immunotherapy; new survivors with uncertain prognosis); or (3) AYAs with a low-grade glioma (LGG) who are living with the knowledge that tumor progression inevitably occurs and likely will be lethal (Burgers et al., 2021). Additionally, we included five eligible AYA patients to participate in focus groups. The study obtained ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of Netherlands Cancer Institute (IRBd20-205).

Procedure

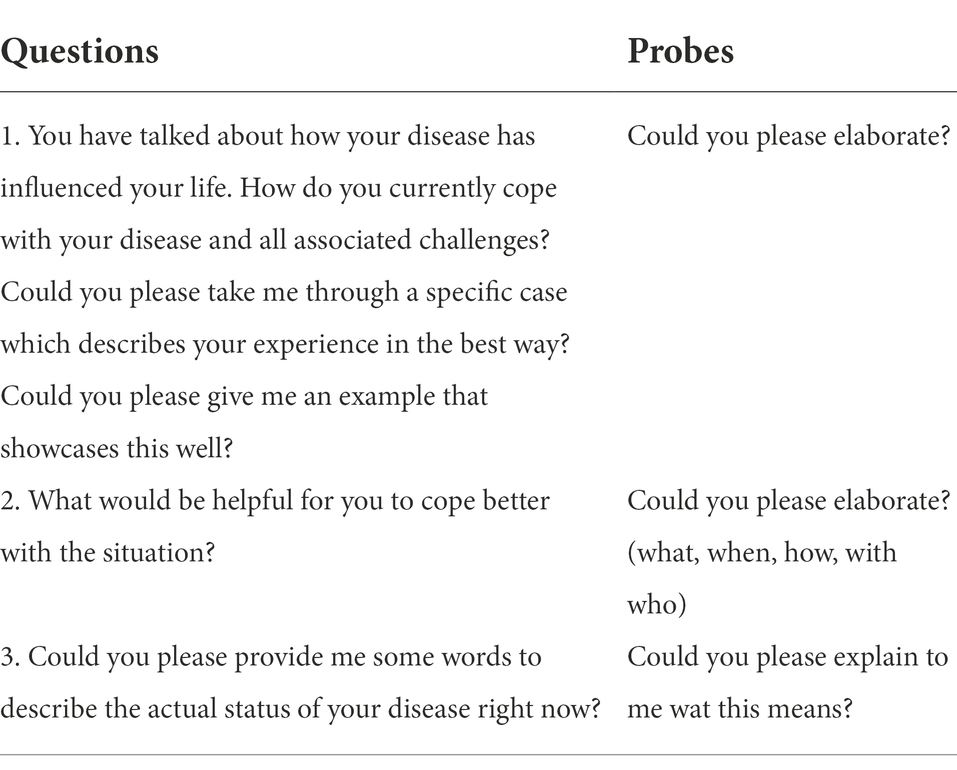

A trained female psychologist and qualitative researcher (VB) conducted all semi-structured interviews after informed consent. The interview guide was based on current literature and drafted in collaboration with experienced researchers (WG, OH) and AYA patients who were actively involved as research partners in this study (AD, NH, MH, SF, SF; Table 1). For more details on the active involvement of AYA research partners in this study, see the GRIPP2-SF checklist (Staniszewska et al., 2017) (Supplementary material 2). VB also led two online focus groups regarding the topic of coping in which preliminary results were discussed with AYAs to check for interpretation and gain additional insights. Interviews and the focus groups were audio-recorded and lasted on average 84 min (range: 49–122) and 55 min (range: 40–70) respectively. Besides the interview and focus group, patients completed a short case record form (CRF) on their sociodemographic and medical status. Additionally, clinical data was obtained from their treating clinician after patients gave explicit permission.

Data analysis

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were analyzed by VB with the help of NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2022). Analysis was performed using elements of the grounded theory by Corbin and Strauss, such as open, axial and selective coding in combination with a constructivist philosophical perspective (Corbin and Strauss, 2014; Sebastian, 2019). A cyclic process was applied of interviewing, visualizing, analyzing and reflection by memo writing, leading to more specific questions. For the first 15 interviews (five each subgroup) were also analyzed by another independent researcher (MR) to identify and discuss different perspectives on the same data. In case of disagreement, the codes were discussed with the AYA research partners and the research team. Axial coding was done with the help of “the paradigm’ of Corbin and Strauss (2014). With selective coding all the data came together to construct an explanatory framework about coping with a UPCP at AYA age, which was checked by the research team and AYA research partners. Data collection stopped when conceptual saturation was reached (Corbin and Strauss, 2014).

Results

Demographics

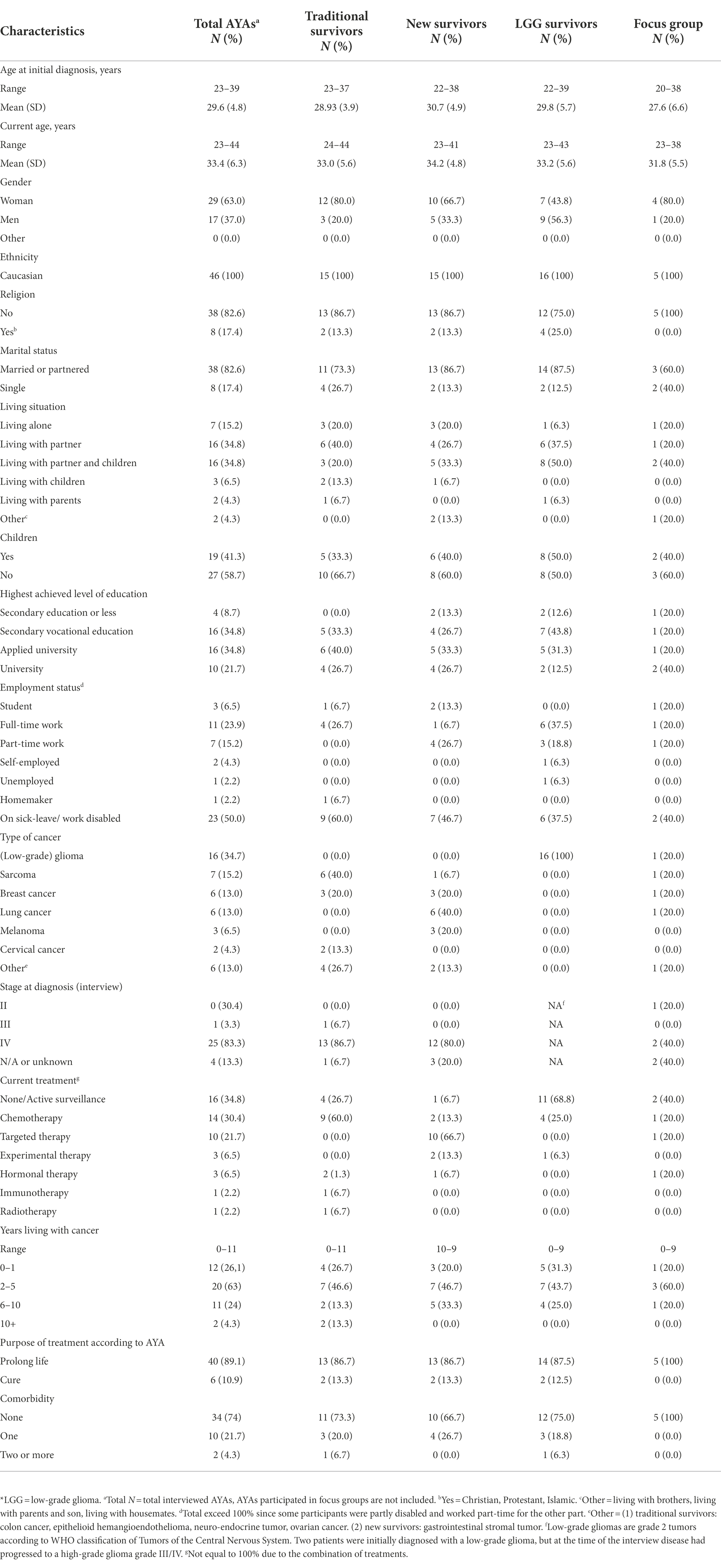

In total, 64 patients were approached and 46 (72%) were actually interviewed. Eleven patients declined due to illness, four patients reported they were too busy or did not want to talk about their disease and three patients did not respond. The median age of the AYAs at time of the interview was 33.5 years and the majority of the participants were woman, had a partner and did not have children. Patients most frequently had (low-grade) gliomas, followed by sarcomas, breast cancer and lung cancer (Table 2).

Findings

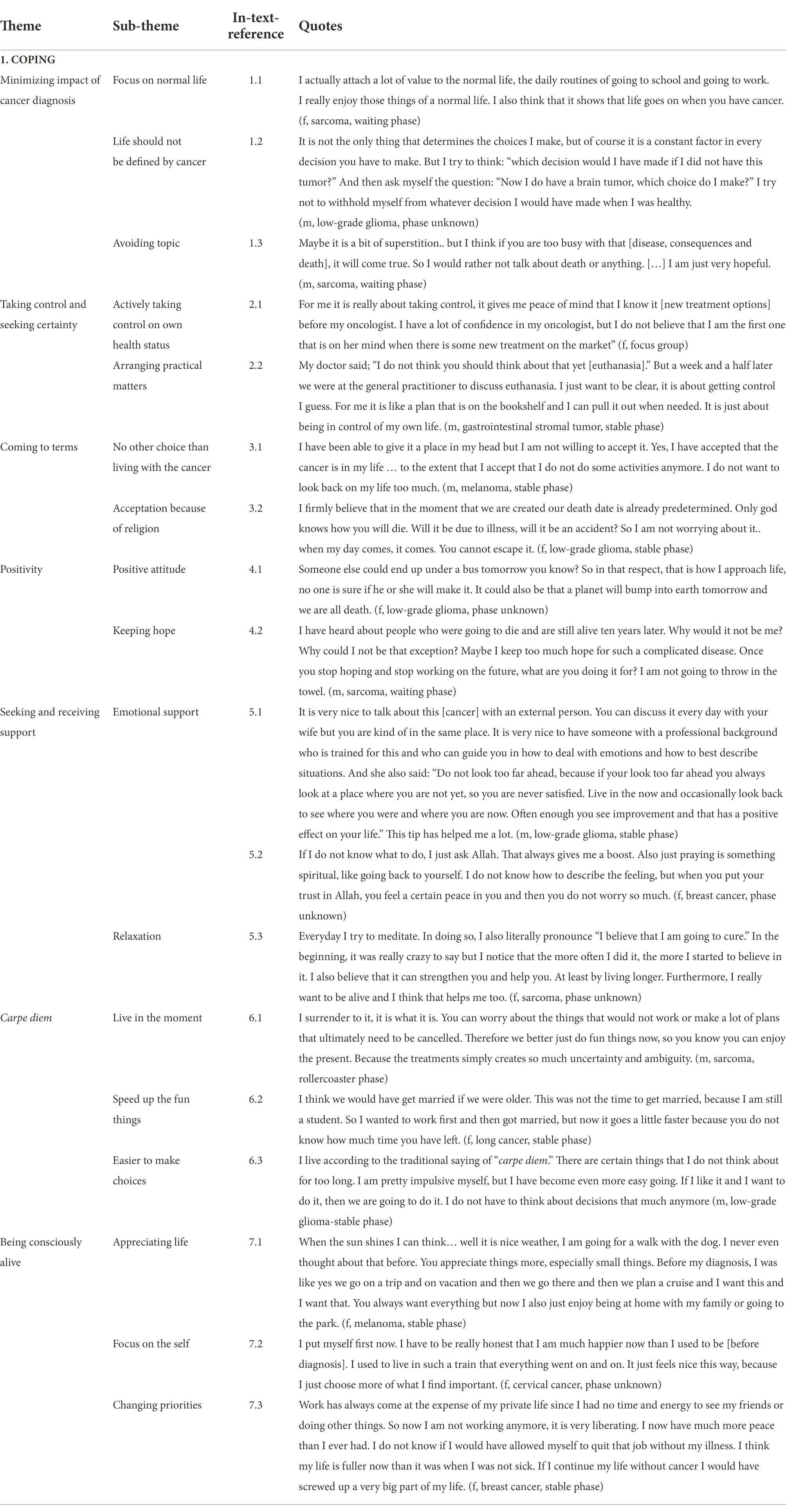

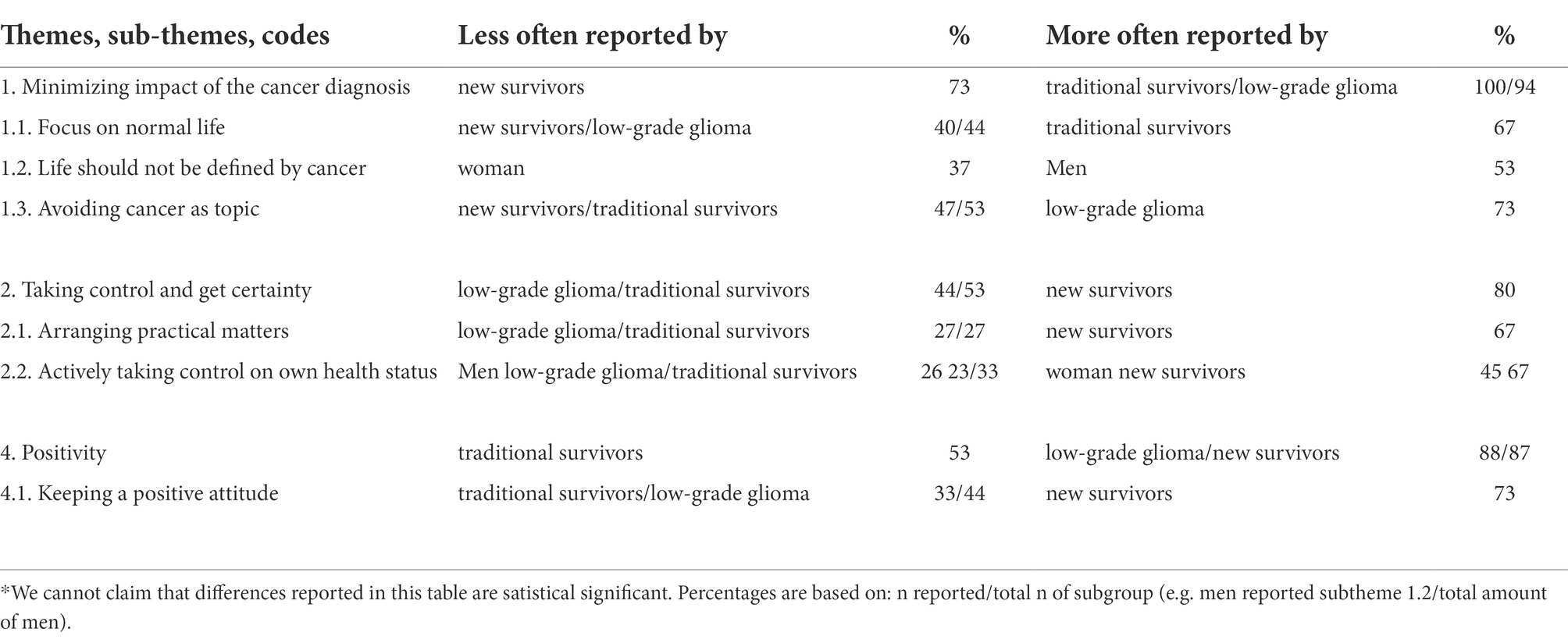

We identified seven main themes regarding coping with the daily challenges of AYAs living with a UPCP. The themes, sub-themes and quotes (including phase of AYA) are presented in Table 3. The numbers in the text refer to matching quotes of the AYAs to give a vivid illustration. Remarkable differences between AYA subgroups are presented in Table A1 in the Appendix.

Theme 1: Minimizing the impact of the cancer

Half of the AYAs with a UPCP want to minimize the impact of cancer by focusing on living a normal life in which they perform their daily routines like going to work and bringing their children to school. Living as normal as possible also includes not being identified as cancer patient, whereby AYAs try to keep up with their peers by ignoring physical complains and make sure that cancer is not always the center of attention. Many AYAs experience daily routines, fun activities and voluntary jobs as a good distraction to push the cancer to the background and live a “normal life” (1.1). Seeking distraction was challenging during the COVID-19 lockdown period. AYAs are confronted with many choices and decisions regarding their life and future plans without any future certainty. However, almost half of the AYAs reported their life should not be defined by cancer with the result that they make choices as if they are not ill, so they will not regret their decisions if they live longer (1.2). To avoid that life will be defined by the cancer, some AYAs did not want to know their prognosis at all. They are afraid that knowing their life expectancy will make them organizing their lives around a date of death. AYA men more often report this coping strategy. Another way AYAs try to minimize the impact of cancer is to avoid cancer as topic. Half of the AYAs reported that they are suppressing their thoughts and emotions regarding cancer and end of life since this causes negative emotions. Some AYAs associated thinking and talking about the cancer and its consequences as being weak and made them conscious of their poor prognosis, while others were still in the fighting mode and not ready to talk about it. At last, some AYAs believe they bring death upon themselves when focusing attention on this topic by talking about it (1.3). In general, minimizing the impact of cancer is most reported by traditional AYA survivors and AYAs with a low-grade glioma. However, AYAs indicate that minimizing the impact of the cancer does not mean they are completely in denial of their diagnosis.

Theme 2: Taking control and seeking certainty

Since uncertainty is overwhelming in AYAs with a UPCP, many try to take back any control or get any certainty where possible. This helps them to live as normal as possible. For example, by actively taking control on own health status. This includes; wanting to know every medical detail about their tumor or treatment and having control over treatment options (2.1). For some, understanding what is going on in their body and which treatments are available worldwide is a way to process the situation and to gain some hope. Other AYAs are trying to be in control by focusing on a healthy lifestyle, like exercising and specific diets. When they conduct this behavior, they are able to focus on their normal life routines. Furthermore, many AYAs are in need to take control regarding their death and inheritance. Having organized and planned euthanasia, the will and their funeral results in some kind of peace, allowing the AYA to move these topics to the background again (2.2). For some AYAs it is also about ensuring a desired future for their family by creating a lasting impact on the lives of their loved ones and making things easier on their family by leaving their partner and kids financially well.

Theme 3: Coming to terms

At least half of the AYAs report that they have come to terms with cancer and its consequences. A lot of them experience that there is no choice other than living with the cancer since fighting against it does not help and may make it even harder to live with cancer. Cancer is part of their lives and they have to find their way to live with it over time, however, not everyone can or will accept their situation (3.1). Some AYAs claimed they have accepted the cancer since this is how they simply deal with the situation or because of the comforting statements from their religion. A few AYAs find peace in their religion, for example they feel like they regain control over their lives by relinquishing control to Allah in which they are accepting Allah’s’ fate, suggesting their death date is predetermined (3.2). Relying on their faith was also helpful to make sense of one’s situation. All AYAs reported that time was helpful to find their way on how to deal to with their disease.

Theme 4: Positivity

The majority of the AYAs with a UPCP believe that a positive attitude is their motivational factor and has a positive impact on their mental and physical situation. This coping strategy is seen especially in new survivors. Some AYAs suggest having a natural positive attitude and others have learned to focus on the positive aspects of life. Another manner to be positive is by reframing. Like for example, reframing that sickness due to treatment is something positive since it is working against the cancer. Others are putting things into perspective, especially regarding the uncertainty in which they usually make the comparison that nobody is certain about their future (4.1). Many AYAs are keeping hope for a prolonged life or even a cure due to trust in medical science, the feeling of being a medical exception and feeling physically well (4.2). Keeping hope is the only way to keep them going. Coping with positivity is least used by AYAs receiving traditional treatment.

Theme 5: Seeking and receiving support

Almost all AYAs are seeking or receiving emotional support by family, partners, friends or AYA peers. Venting or doing fun things as a distraction feels supportive for AYAs. Others are seeking professional support by means of a psychologist, social worker or AYA clinical nurse specialist (5.1). Some AYAs seek religious support like praying to Allah (5.2). Nevertheless, several AYAs notice they are mostly supporting themselves, since they did not ask or receive the right support from others or felt like they do not fit in support groups. Others explained that they want to solve their problems on their own and want to experience the cancer process all by themselves, mostly in order to not burden others. Furthermore, relaxation methods like mindfulness and writing to express their feelings are also providing benefits for some AYAs (5.3).

Theme 6: Carpe diem

During the focus group sessions AYAs expressed that life was exhausting for them since they were always searching for some kind of balance in all the chaos. One AYA has found this new balance while the others are searching for it, asking themselves if they will ever find it. Some are actively searching for it while others are not being aware of this ‘new state of life’. Although this new state was not reported in the interviews, AYAs reported concepts of how to live relatively good with a UPCP. For most AYAs the context of an uncertain and poor prognosis results in living in the moment. They prefer to focus on living day by day instead of thinking about the future (6.1). Most of them learned it the hard way since planning the future is difficult, disappointing or sometimes not doable because of treatment and prognosis uncertainty. They try to enjoy the present to the fullest and speed up the fun things they would like to do in life, such as travelling and getting married (6.2). For some AYAs it is much easier now to make choices regarding things on their wish lists (6.3).

Theme 7: Being consciously alive

Being alive with a UPCP results in AYAs appreciating (the little) things in life more compared to before the cancer diagnosis, like enjoying the sun and being thankful for everyone around them (7.1). Some AYAs believe they now focus more on themselves instead of others (e.g., prioritizing friendships that give them energy), their job (e.g., quitting their job) or future (7.2). This is also the result of changing priorities since being aware of the value of life ensures AYAs to focus on their health and family (7.3). Some AYAs feel even happier and believe that their quality of live is increased.

Discussion

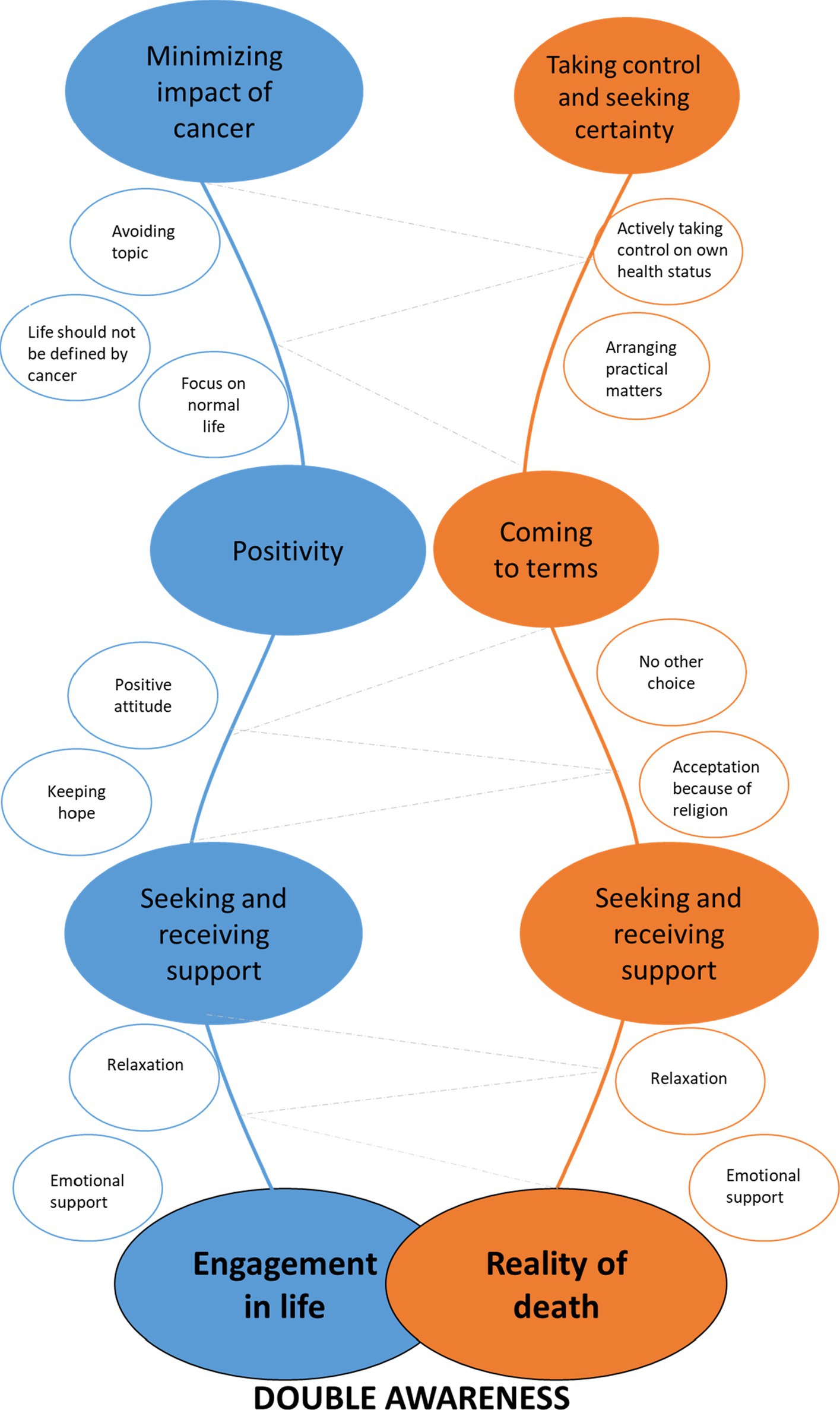

Findings from this qualitative interview study reveal that AYAs with a UPCP use multiple coping strategies like; minimizing impact of cancer, taking and seeking control, coming to terms, being positive, seeking and receiving support, carpe diem and being consciously alive in order to reduce the suffering from the experienced challenges. These results may indicate that this group is walking on two paths at the same time while coping with their UPCP; one path focusing on engagement in life and one path focusing on the reality of premature death. For example, some AYAs are hopeful for cure but at the same time accepting their poor prognosis. It seems that factors like; flow of life, hospital appointments or medical progression determine which path the AYA walks on. This capacity to cope in a context of a prolonged living-dying interval is earlier described by Rodin & Zimmerman as ‘double awareness’ (Rodin, 2013; Colosimo et al., 2018). See Figure 1 for the integration of double awareness in AYAs with a UPCP according to the results of this study.

Figure 1. Double awareness in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with a uncertain or poor cancer prognosis (UPCP). *Size of the colored circles represents the frequency of the reported coping strategies. (e.g.) circles of ‘minimizing impact of cancer’ and ‘seeking and receiving support’ are largest, suggesting that these coping strategies were reported the most.

With regard to the first path, the engagement in life, we found that AYAs are trying to minimize the impact of cancer. In line with previous research, AYAs want to stick to normalcy and seek distraction to avoid negative thoughts or situations that were anticipated to cause stress(Trevino et al., 2012; Walshe et al., 2017; Lie et al., 2018; Arantzamendi et al., 2020; Bradford et al., 2022). It is remarkable that coping by minimizing the impact of cancer was least reported by new survivors, possibly because these patients experience minimal impact of their treatment in daily life. It seems that especially men in this study do not want their life to be defined by cancer and implement strategies like not wanting to know their prognosis and not wanting to make other decisions than when they were healthy. Literature suggest that men wish to avoid engagement in issues of death and dying (Seifart et al., 2020). These observed gender differences might result from the product of a masculine gender-role in which men should be tough and emotionally inexpressive, which is easier when not being aware of the poor prognosis (Addis and Mahalik, 2003). Extra attention could be given in clinical practice to ensure that these AYA men also receive the right support. Another coping strategy we identified is positivity, which seems to be an essential manner of dealing with difficult emotions or situations and protecting mental health (Arantzamendi et al., 2020; Bradford et al., 2022). Previous research has found that positive framing was related to better quality of life and less depressive symptoms in incurable patients (Nipp et al., 2016). In line with these observations, hope seems to be a source of motivation for AYAs to face their present and future life (García-Rueda et al., 2016). The uncertainty in AYAs with a UPCP results in some extra options for hope, since there is no certainty of a poor end. It seems that AYAs on traditional treatments use positivity and hope less often, which could be explained by their poor health situation or by the fact that they did not have much hope that new treatments will arise.

Looking at the second path, reality of premature death, we found that AYAs want to have control over practical matters regarding death and inheritance, such as their funeral. To take back any control, AYAs want to actively take control of their own health status, which includes knowing all the details about their cancer diagnosis and focusing on new available treatment options. Half of the AYAs come to terms with their disease and get on with their lives. In line with previous research most participants described this as the only choice they had, because it was seen as essential to be able to move forward in life (Arantzamendi et al., 2020). Other research suggests that finding acceptance is correlated with less anxiety and depression and better quality of life (Nipp et al., 2016; Greer et al., 2020). At last, AYAs are seeking and receiving emotional and professional support. Earlier research suggested that social support is a key element in AYAs, resulting in higher psychosocial and existential quality of life and less grief (Trevino et al., 2012). These mental health benefits are also seen in correlation with religious coping, which helps AYAs to make sense of their situation in a way that supports acceptation (Alcorn et al., 2010; Barton et al., 2018; Arantzamendi et al., 2020). Young adults in the Dutch general population are described as less religious than older adults, however, religious young adults facing a disease view their religion as a guideline on how to cope with their disease and navigate their illness experience (King et al., 2021; CBS, 2022). AYAs also reported to seek social support, which is in contrast with our previous findings suggesting that AYAs feel alone since nobody truly understood their experiences and they tend to protect loved ones (Burgers et al., 2021). It is possible that having someone to count on does support the AYA, but is not the solution for the sense of loneliness.

Furthermore, theme six and seven of our result section suggest that AYAs with a UPCP strive to find a new balance in life (a new state) by living according to the metaphor carpe diem and being consciously alive. It could be that these patients have found double awareness. These results show some similarities with the study of Garcia et al. in which they identified that the majority of people with advanced cancer try to find (new) meaning in life to be able to enjoy life despite the disease (García-Rueda et al., 2016). In line with previous research it is about shifting the attention away from illness and the desire to live as fully as possible (Arantzamendi et al., 2020). Accepting the cancer and premature death facilitates this process. However, this process takes time and not everyone succeeds. Future research is needed to get a better understanding of this new state and examine predictive and risk factors.

Strengths and limitations

This paper is the first to present how AYAs with a UPCP cope with their daily life challenges and offers insights in the combination of living well while also facing uncertainty around death. Additionally, this study is pioneering in involving patients as AYA research partners. In terms of qualitative research, the sample size is relatively large. This study also has some limitations. First, the representation of ethnic minority groups was limited. Since religion seems to play an important role in coping with a UPCP, future research should especially focus on the coping style of ethnic minority groups. In our sample we did not observe important differences in coping strategies between different ages. However, it should be mentioned that young AYA patients between the ages of 18 and 25 were slightly underrepresented. Lastly, according to the concept of double awareness, coping strategies may fluctuate over time. Since this study is cross-sectional, we were not able to access this process. A longitudinal study is recommended to examine the fluctuating process of coping over time.

Clinical implications

Taking into account the positive correlation between coping strategies and quality of life, it seems indeed possible to live well with a UPCP. However, we have to keep in mind that some AYAs are still struggling to cope with the disease and not everyone reached double awareness. For example, AYAs can be in a problematic relation with the idea of death, such as avoiding making plans due to preoccupation with mortality (Burgers et al., 2021). When experiencing this tensions between life and death, Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully (CALM) therapy, could be recommended. This brief, tailored psychotherapeutic intervention seems effective in relieving and preventing depressive symptoms and can help patients to address preparations for the end of life (Rodin et al., 2018). Colosimo and colleagues provide a framework for using CALM to cultivate double awareness (Colosimo et al., 2018). However, up to now, there is no literature focusing on CALM therapy in AYA patients and the question that arise is how double awareness works in this AYA group given their unique age, developmental phase of life and prognostic characteristics of their disease. Future research on the concept and determinants of double awareness in AYA patients with a UPCP, and the effectiveness of CALM therapy in this patient group is needed. Furthermore, the positive effects of social support, specifically AYA peer support, seems not always as effective as described in literature. In practice, some AYAs want to avoid negativity and confrontation and therefore do not want to join a peer support group (Bradford et al., 2022). Since they may still have the need for mutual interactions, AYA peer support should also offer the option of informal meetings. For example, the Dutch AYA ‘Young and Cancer’ Care Network has implemented AYA lounges in hospitals and the Dutch Youth and Cancer foundation is organizing meetings in bars. At last, a positive attitude or minimizing the impact of cancer by preferring not to know prognosis or medical information is not directly an indication of lack of awareness of dying. Instead, it could be a protective function as it allows hope (Hagerty et al., 2005). We encourage healthcare professionals to explore patients coping style and in specific prognostic information preferences and the underlying reasons in order to provide tailored communication (van der Velden et al., 2022).

Conclusion

We identified seven different coping strategies around the concept of ‘double awareness’ and found that AYAs want to reach a new balance in life in which they manage their new state. AYAs are able to actively cope with their UPCP but actively choose life over illness and also need a break from cancer sometimes. However, this does not imply that they deny the cancer and its consequences. Recommendations included CALM-therapy and informal AYA support meetings targeted to UPCP to support AYAs to cope well with their UPCP.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Netherlands Cancer Institute (IRBd20-205). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OH and WG conceptualized the study and acquired funding. VB, AD, SF, MN, WG, and OH developed methodology. VB, MB, DR, and WG contributed to patient recruitment. VB performed interviews and analysis with help of AD, SF, MN, WG, and OH were also involved in analysis discussions. The original draft was prepared by VB, WG, and OH. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

OH and VB are supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research [grant number VIDI198.007].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Milou J. P. Reuvers (MR) for being the second coder for the data analysis and thank Niels Harthoon and Simone Frissen for their active contribution as AYA research partner.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1026090/full#supplementary-material

References

Addis, M. E., and Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am. Psychol. 58, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5

Alcorn, S. R., Balboni, M. J., Prigerson, H. G., et al. (2010). “If god wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today,”: religious and spiritual themes in patients' experiences of advanced cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 13, 581–588. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343

Arantzamendi, M., García-Rueda, N., Carvajal, A., and Robinson, C. A. (2020). People with advanced cancer: the process of living well with awareness of dying. Qual. Health Res. 30, 1143–1155. doi: 10.1177/1049732318816298

Barton, K. S., Tate, T., Lau, N., Taliesin, K. B., Waldman, E. D., and Rosenberg, A. R. (2018). “I’m not a spiritual person.” how Hope might facilitate conversations about spirituality among teens and young adults with cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 55, 1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.001

Bradford, N., Cashion, C., Holland, L., Henney, R., and Walker, R. (2022). Coping with cancer: a qualitative study of adolescent and young adult perspectives. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 974–981. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.034

Burgers, V. W. G., van den Bent, M. J., Dirven, L., et al. (2022). Finding my way in a maze while the clock is ticking: the daily life challenges of adolescents and young adults with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis. Front. Oncol. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.994934

Burgers, V. W. G., van der Graaf, W. T. A., van der Meer, D. J., et al. (2021). Adolescents and young adults living with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis: the “new” lost tribe. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 19, 240–246. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7696

CBS (2022). Religieuze betrokkenheid; persoonskenmerken. Available at: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/cijfers/detail/82904NED?q=religie (Accessed July 22, 2022).

Colosimo, K., Nissim, R., Pos, A. E., Hales, S., Zimmermann, C., and Rodin, G. (2018). “Double awareness,” in psychotherapy for patients living with advanced cancer. J. Psychother. Integr. 28:125. doi: 10.1037/int0000078

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory Sage Publications.

García-Rueda, N., Carvajal Valcárcel, A., Saracíbar-Razquin, M., and Arantzamendi, S. M. (2016). The experience of living with advanced-stage cancer: a thematic synthesis of the literature. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 25, 551–569. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12523

Greer, J. A., Applebaum, A. J., Jacobsen, J. C., Temel, J. S., and Jackson, V. A. (2020). Understanding and addressing the role of coping in palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 915–925. doi: 10.1200/jco.19.00013

Hagerty, R. G., Butow, P. N., Ellis, P. M., et al. (2005). Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients' views on the disclosure of prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 1278–1288. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.11.138

King, S. D. W., Macpherson, C. F., Pflugeisen, B. M., and Johnson, R. H. (2021). Religious/spiritual coping in young adults with cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 10, 266–271. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2020.0148

Lie, N. K., Larsen, T. M. B., and Hauken, M. A. (2018). Coping with changes and uncertainty: a qualitative study of young adult cancer patients’ challenges and coping strategies during treatment. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 27:e12743. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12743

Lobb, E. A., Lacey, J., Kearsley, J., Liauw, W., White, L., and Hosie, A. (2015). Living with advanced cancer and an uncertain disease trajectory: an emerging patient population in palliative care? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 5, 352–357. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000381

Nipp, R. D., El-Jawahri, A., Fishbein, J. N., et al. (2016). The relationship between coping strategies, quality of life, and mood in patients with incurable cancer. Cancer 122, 2110–2116. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30025

QSR International Pty Ltd (2022). NVivo. Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (Accessed June, 2022).

Rodin, G. (2013). Research on psychological and social factors in palliative care: an invited commentary. Palliat. Med. 27, 925–931. doi: 10.1177/0269216313499961

Rodin, G., Lo, C., Rydall, A., et al. (2018). Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): a randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2422–2432. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.1097

Sebastian, K. (2019). Distinguishing between the types of grounded theory: classical, interpretive and constructivist. J. Soc. Thought. 3, 1–9.

Seifart, C., Riera Knorrenschild, J., Hofmann, M., Nestoriuc, Y., Rief, W., and von Blanckenburg, P. (2020). Let us talk about death: gender effects in cancer patients’ preferences for end-of-life discussions. Support. Care Cancer 28, 4667–4675. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05275-1

Staniszewska, S., Brett, J., Simera, I., et al. (2017). GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3453

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Trevino, K. M., Maciejewski, P. K., Fasciano, K., et al. (2012). Coping and psychological distress in young adults with advanced cancer. J. Support. Oncol. 10, 124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.08.005

van der Velden, N. C. A., van Laarhoven, H. W. M., Burgers, S. A., et al. (2022). Characteristics of patients with advanced cancer preferring not to know prognosis: a multicenter survey study. BMC Cancer 22:941. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09911-8

Walshe, C., Roberts, D., Appleton, L., et al. (2017). Coping well with advanced cancer: a serial qualitative interview study with patients and family Carers. PLoS One 12:e0169071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169071

Appendix 1

Keywords: adolescents and young adults, uncertain or poor cancer prognosis, coping, qualitative research, CALM therapy

Citation: Burgers VWG, van den Bent MJ, Rietjens JAC, Roos DC, Dickhout A, Franssen SA, Noordoek MJ, van der Graaf WTA and Husson O (2022) “Double awareness”—adolescents and young adults coping with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis: A qualitative study. Front. Psychol. 13:1026090. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1026090

Edited by:

Gregor Weissflog, Leipzig University, GermanyReviewed by:

Diana Richter, University Medical Center Leipzig, GermanyEttore De Berardinis, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Burgers, van den Bent, Rietjens, Roos, Dickhout, Franssen, Noordoek, van der Graaf and Husson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olga Husson, b2xnYS5odXNzb25AaWNyLmFjLnVr

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Vivian W. G. Burgers

Vivian W. G. Burgers Martin J. van den Bent

Martin J. van den Bent Judith A. C. Rietjens4

Judith A. C. Rietjens4 Annemiek Dickhout

Annemiek Dickhout Winette T. A. van der Graaf

Winette T. A. van der Graaf Olga Husson

Olga Husson