- College of Foreign Languages, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, China

“Hezhe” (合着), “ganqing” (敢情), and “nao le bantian” (闹了半天) are common mood expressions in modern Chinese which have a common function of summarizing the information before (so called ‘sum-up’) as well as similar pragmatic functions. Study on these mood adverbs could reveal how the interactional mechanism molds the original semantic meanings of mood words and leads to new pragmatic functions. Five verbal corpora are applied to collect the real materials of usage containing the above three mood adverbs. Functional analysis and data statistics have been carried out to categorize the pragmatic functions of these words, calculate their distributions, and reconstruct their evolutional approach through an interactional perspective. We have found a core theoretical viewpoint that the similar functions of the three words emerged through the same pragmatic mechanism called “violation”. These functions are: (1) “unexpectation” from the violation of psychological expectation; (2) “criticism” from the violation of universal principles; (3) “humor” from the violation of communicative principles. A statistic work of several corpora showed that these functions of the above three words appear broadly in verbal materials, with differences in their proportions according to the communication types and genres. In Chinese teaching to speakers of other languages, more attention should be paid to these words stemming from dialects, especially during intermediate and advanced levels.

Introduction

What are “sum-up” adverbs?

As a highly isolated language, Chinese doesn't have mood inflections like subjunctive expressions in English and other Indo-European languages. However, emotion, attitude, intimacy, judgment, and so on of the speaker could be expressed by some words such as adverbs and some adverbial phrases, known as “mood adverbs.” However, in other situations, an adverb that originally holds a certain meaning could be attached with some “mood meaning,” thus transforming it into a mood adverb. Such transformation would happen habitually during daily communications before it was fixated and became the prevalent or even dictionary meaning of the word itself. In other words, such mood meanings have been molded during language interactions.

In the intermediate and advanced levels of Teaching Chinese to Speakers of Other Language, or TCSOL, sometimes real audio-visual materials are used as pedagogical materials, such as Chinese interview program clips. During class, students often raise questions about the meaning and usage of some words with mood meaning in the materials, usually colloquial rather than formal. These words do not appear in textbooks, and the TCSOL syllabus does not fully incorporate them. It is difficult for students to fully understand and even master their usage only by consulting dictionaries or other reference books. Especially, some colloquial words originating in dialects have not yet been included in dictionaries. Among them, several such mood adverbs with similar functions have attracted our attention, for example:

(1) 进我们自己的家, 还需要往你口袋里扔钱, 合着里外都让您赚了, 这合适吗?

jin women ziji de jia, hai

enter our own of home still

xuyao wang ni koudai li

need to your pocket inside

reng qian, hezhe liwai

throw money totally speaking inside and outside

dou rang nin

all let you

zhuan le, zhe

earn (perfective aspect particle) this

heshi ma?

proper (question article)

To enter our own house, we need to throw money into your pocket, so totally speaking, you earn money either way. Is this proper? (from a news program on CCTV).

(2) 一千五百块钱, 我还当是稿费, 后来我才看明白, 敢情上杂志上发表您的论文, 是您要给杂志钱。

yiqianwubai kuai qian, wo

1500 (currency unit) money I

hai dang shi gaofei,

originally think be royalties

houlai wo cai kan mingbai,

later I just see clearly

ganqing shang zazhi shang

you dare say go magazine on

fabiao nin de lunwen, shi nin yao

publish you of paper be you need

gei zazhi qian.

give magazine money

I had thought this 1500 yuan was the royalties (given to the author). Only later did I understood, you dare say, that if you'd like to publish your paper on the magazine, it is you who should pay money (from a talk show on Phoenix Satellite TV).

(3) 闹了半天, 是这么回事儿, 既然这吉祥号这么惹麻烦, 您就不能换一个吗?

Nao le bantian, shi zheme

after so much fuss be so

hui shier,

(measure word) issue

jiran zhe jixiang hao zheme re mafan,

since this auspicious number so incur trouble

nin jiu bu neng huan

you just not can change

yi ge ma?

one (measure word) (question article)

After so much fuss, we finally make out the truth. Since the auspicious phone number incurs so much trouble, why can't you change for another one? (from a news program on Beijing TV).

From the examples above, we can see words and phrases like “hezhe” (合着), “ganqing” (敢情), and “nao le bantian” (闹了半天), and they express a basic meaning similar to “conclude” in colloquial Chinese to summarize the information that appeared before their clause. Yet, they are different from the typical “conclude” adverbs and phrases such as “zongzhi (总之)” (in a word) and “zong de lai shuo (总的来说)” (generally speaking), in that they don't acquire such meaning through the morpheme or elements that they are composed of such as “总” (total) and in that they contain certain kinds of mood besides the basic semantic meaning, e.g., beyond expectation, dissatisfaction, criticism, etc., which the typical “conclude” words don't have. Therefore, these words should form an independent category as they perform similar pragmatic functions during interactions above their basic semantic meaning, that is, these words can be regarded as mood adverbs in a broad sense, and at the same time, they all complete the function of summarizing the situation. We refer to these words as “sum-up” mood adverbs.1

Mood elements in modern Chinese are a kind of collection with different origins, complex internal compositions, and diverse meanings and functions. There are different views on the classification of the Chinese mood system (Lv, 1982; Wang, 1985; Gao, 1986; He, 1992; Qi, 2002) and the classification of mood words (Zhang, 2000; Qi, 2003). In particular, the classification and functional generalization of mood words have been discussed for a long time, but a consensus has not yet been reached. The reason for this complex state is that the “mood” gradually obtains its pragmatic meaning and function in the process of real communication.

Social interaction and communication are the original natural habitat of language. We should understand the structure and application of language from the actual verbal communication (Fang, 2005; Couper-Kuhlen and Selting, 2018; Fang et al., 2018; Zeng, 2021). For every specific language component, their research should not be separated from the conversation environment in which they are located, and we should study “dynamic” language (Zhu, 2021). For various mood adverbs mainly produced and used in spoken language, their synchronic performance and functions also “emerge” in the communication within a conversation from the diachronic perspective, thus gradually forming and shaping the language system. Although many mood words stemmed from different sources, they gradually form pragmatic conventions through their use in communication, and according to their pragmatic functions, similar mood words can be grouped together. Therefore, it is necessary to study the specific functional categories to which each specific mood word belongs, explain the different “emerging” paths of similar pragmatic functions in the same category, explore the aggregation mechanism of each category, and then piece together the classification panorama of mood words themselves.

To train learners' oral Chinese communication ability in a real context, it is also necessary to make an in-depth study of these colloquial mood adverbs and analyze their semantic and pragmatic functions by using real corpora. This study, therefore, undertook a pragmatic study on the mood adverbs with “sum-up” meaning such as “hezhe,” “ganqing,” and “nao le bantian” and explained the emergence and development of the pragmatic functions of these words in communication, to provide a reference for international Chinese education.

Research review

This research selected a special category of mood adverbs, whose core meaning can be summarized as “sum-up.” Representative words include “hezhe,” “ganqing,” and “nao le bantian (nao le guiqi).” These words originated from different sources, but they “emerge” with similar pragmatic functions in communication, and their functions have not been accurately recognized or described so far.

Studies on this kind of mood words are few, most of which are dissertations, and their conclusions are quite similar. Qi (2008) defined “hezhe” as a colloquial word in Beijing dialect and summarized its five meanings, of which the last one is “that the speaker makes corresponding reasoning or assumptions about things on the premise of integrating the existing conditions, or knows something according to the summary,” and believes that this usage is equal to “yuanlai” (原来, turn out to be). Qi's study only listed the different usages of “hezhe” at the semantic level, without considering the pragmatic mechanism. The master's thesis of Liu (2012) followed the classification of Chinese adverbs from Zhang (2000), classified “hezhe” as a commentary adverb, and summarized its semantic function into two aspects: in terms of message transmission, its function is “interpretation of known real news by tracing its origin,” and in terms of modality, its function is “emphasis” and “in-depth probe.” The pragmatic functions of “hezhe” are the evaluation function, emphasis function, and textual function. Fang (2018) summarized the pragmatic functions of “hezhe” into three categories: “objective description” “subjective cognition,” and “negative evaluation” in his doctoral thesis, and believed that its expression of negative evaluation is a prescriptive meaning that has “emerged” in interaction.

There are also several specialized research studies on “ganqing.” The master's thesis of Wang (2014) also followed the theoretical framework of Zhang (2000) and summarizes the function of “ganqing” into two aspects: semantic function and pragmatic function. The semantic function includes communication functions such as explanation, assertion, speculation, and summary, as well as mood functions such as emphasis and in-depth probe. The pragmatic function includes evaluation, indicating presupposition, expression, emphasis, and textual function. Han (2014) summarized the meaning of “ganqing” into three kinds: (1) “tracing the origin thus making explanation,” (2) assertions that reinforce affirmation, and (3) indicating a speculative question. The motivation and mechanism of grammaticalization of “ganqing” mainly include frequency principles, analogy principles, rhythm principles, and pragmatic factors. Wu's master's thesis (Wu, 2016) compared “ganqing” with “yuanlai,” and “biding (必定)” (for sure) and “nandao (难道)” (is it really that…?), and held that they have something in common in semantics, but “ganqing” expresses stronger feelings and stronger subjectivity. This research also summarized the main error types of “ganqing” in Chinese as second language acquisition. Nan (2019) summarized the evolving process of “ganqing” from a diachronic perspective and believed that the development of “gan” (dare) and “qing” (emotion) combined from independent words to verb-object phrases, and then evolving into commentary adverbs is the result of the joint influence of the meaning of the words themselves and the external communication situation.

As to other such mood adverbs, no specialized research has been seen. The comparative research of two or more such mood adverbs is also limited to “hezhe” and “ganqing.” Among them, Fang (2018) believes that the two words can be interchanged when expressing the positive judgment function, while when “hezhe” is used as an attitude marker and “ganqing” is used to express the interrogative judgment function, they cannot be replaced with each other. Yang's master's thesis (Yang, 2019) conducted a specialized study on these two words and found that they overlap in semantics, but “ganqing” has richer semantic connotations and more flexible syntactic distribution.

Generally speaking, the research on such mood adverbs focuses mainly on the two words “hezhe” and “ganqing.” The conclusions show the following features: (1) Stepping from the parallel summary of multiple meaning items to the distinction between semantic and pragmatic levels; (2) Looking for the motivation of word evolution from the inside and outside aspects of words, and taking context, communication, and interaction into account; (3) Actively exploring other theoretical perspectives outside the framework of traditional Chinese grammar research.

Besides the small scale, existing studies are still wanting in several aspects: First, the scope of words studied is relatively narrow, and still fewer comparisons among different mood adverbs. Second, the mechanism of pragmatic function is not fully explored, thus lacking a thorough explanation of the motivation behind the gradual occurrence of the various pragmatic functions. Third, is the lack of corpus work. The existing research works using corpora to investigate the meaning and usage of such mood adverbs are limited to dissertations, and most of them wield written corpora. The analysis and statistics from these studies are not comprehensive enough to fully reflect the distribution and use of these kinds of mood adverbs.

Research method

This paper studies the “sum-up” mood adverbs, selecting “hezhe (合着),” “ganqing (敢情),” and “nao le bantian (nao le guiqi) (闹了半天/闹了归齐)” as examples, uses the oral corpora as the research material, explains the pragmatic function and “emergent” principle of each word through the analysis and statistics from oral conversations, and locates the common mechanism behind the clustering of such mood adverbs. We further try to order the semantic and pragmatic conditions of each word and make statistics and induction on the distribution of different usages, so as to provide a reference for TCSOL.

The corpora used in this paper include five parts: (1) the “Media Language Corpus” (MLC) of Communication, University of China, which contains 34,039 transcribed texts of radio and television programs from the year 2008 to 2013, with a total number of 241,316,530 characters. (2) The TV script of <I Love My Family>, the dialogue of which is Beijing dialect in the 1990s, with a total number of 606,950 characters. (3) CCL Corpus of Peking University, “Oral,” “Artistic TV and movie script,” “Crosstalk and short sketch” part of “Modern period,” and “Script” part of “Contemporary period.” (4) General Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese of China's National Language Commission. (5) “Dialogue” part from BCC Corpus of Beijing Language and Culture University. Because the above corpora are real or imitations of daily conversations, this study can reflect the use of mood adverbs in real communication. For reference, during the research process, we still deployed the “Ancient Chinese” part of the CCL corpus and the HSK corpus from Beijing Language and Culture University as additional resources of ancient Chinese languages as well as of learners of Chinese as a second language.

The workflow of this study is as follows: (1) search each target word in each corpus, manually filter the cases where it is used one by one and remove the cases that are not the object of this study, such as “他合着眼躺在床上” (“he lies on the bed with his eyes closed” in which “hezhe” means “closing”), leaving only valid cases. (2) Invite two other linguists whose mother tongue is Chinese to select ten cases from each of the three groups of valid cases to discuss their pragmatic functions and unify the criteria for judgment. (3) The author and two judges, respectively, judge the pragmatic functions of all cases. (4) By comparing the three judgments, each pragmatic function can be determined only after at least two people agree. If there are three different results, the case should be discussed further and then determined (this did not happen in the actual process).

Analysis of pragmatic functions of “sum-up” mood adverbs

Searching through the corpora, 1,284 valid cases were found, including 368 cases of “hezhe,” 833 cases of “ganqing,” and 83 cases of “nao le bantian” (including 1 case of “nao le guiqi“). The following is a semantic and pragmatic analysis of these words combined with examples from the corpora.

Semantic and pragmatic analysis of “hezhe” (合着)

The Modern Chinese Dictionary (7th Edition) (Dictionary Compilation Office, 2016) does not include “hezhe” as a word, which may be because the origin of “hezhe” has a more dialect feature. Based on the basic meaning of “he” (合): amount to, or add up to, combing the previous research and analyzing the frequency distribution of using cases from corpora, we believe that the basic semantic meaning of “hezhe” is “a summary of the above information,” especially the conclusion of digital calculation. This can be regarded as the basic usage of “hezhe” and also the origin of its “sum-up” function. In ancient vernacular from CCL corpus from Ming Dynasty to the year 1949, we found 67 cases of “hezhe” yet all belonged to the basic meaning or served as a simple verbal phrase. Therefore, we believe that this basic meaning was the original point of the other pragmatic functions. In contemporary corpora, this basic meaning is still used in the following examples:

(4) 年薪4800块, 合着一个月才400元。

Nianxin 4800 kuai, hezhe

annual salary (currency unit) amount to

yi ge yue cai

one (measure word) month only

400 yuan.

(currency unit, equal to ”kuai“)

The annual salary of 4800 yuan amounts to 400 yuan per month.

(5) 5个小时, 1200条短信, 这合着4秒钟就发一条短信啊。

5 ge xiaoshi, 1200 tiao

(measure word) hour (measure word)

duanxin, zhe hezhe

short message this amount to

4 miaozhong jiu fa yi

second only send one

tiao duanxin

(measure word) short message

a.

(exclamation mark)

5 hours, 1200 short messages sent, this amounts to 4 seconds per message.

(6) 王先生首付款才交了18万, 合着首付一成多。

Wang xiansheng shoufu kuan cai

(family name) Mr. down payments only

jiao le

pay (past tense)

18 wan,

ten thousand

hezhe shoufu yi cheng duo.

amount to down payments one 10% more

Mr. Wang just paid 180,000 yuan for down payments, which is only a 10% of the total price.

The above cases use the basic meaning of “hezhe,” in which (4) represents the calculation result of money, (5) represents the calculation result of time, and (6) represents the calculation result of proportion. It should be noted that when “hezhe” is used to represent the calculation result, it is not necessarily the total result obtained by adding, but can be extended to other calculation methods as well. For example, (4) and (5) are the result of division.

In addition to expressing the calculation results, the most common usage of “hezhe” is to convey different pragmatic meanings, including:

(7) 我选择这两位大爷大娘, 合着他们四个都过关啦。

Wo xuanze zhe liang wei

I choose these two (measure word)

daye daniang,

uncle aunt

hezhe

unexpectedly

tamen si ge dou guoguan

they four (measure word) all pass

le

(past tense and exclamation)

I will choose the uncle and aunt, and unexpectedly they four have all passed the test.

(8) 合着刚刚放进存款机的16500块, 压根就没存进去。

Hezhe ganggang fang jin

Unexpectedly just now put in

cunkuanji de 16500 kuai,

ATM of (currency unit)

yagen jiu mei cun jinqu.

absolutely just not deposit into

Unexpectedly, the 16500 yuan put into the ATM just now has totally not entered the account.

(9) 合着里外都让您赚了, 这合适吗?

Hezhe liwai dou rang

Totally inside and outside all let

nin zhuan le.

you earn (past tense)

zhe heshi ma?

This appropriate (question particle)

Totally speaking, in both situation you made the profit. Is it appropriate?

(10) 合着您养他就是为了吃他, 他是猪还是鸡啊?

Hezhe nin yang ta jiushi

totally speaking you raise he is

weile chi ta,

in order to eat he

ta shi zhu haishi ji

he is pig or chicken

a?

(question particle)

Totally speaking, you brought him up just to depend on him one day. Is he a pig or a chicken?

(11) 这边写着, 这边手插电板里, 都是这样写稿子, 合着成电动的了。

Zhe bian xie zhe, zhe

this side write (progressive tense) this

bian shou cha dianban li,

side hand stick socket inside

dou shi zheyang xie gaozi,

all are so write article

hezhe cheng diandong

totally speaking become electrified

de le.

(auxiliary word) (past tense)

We will write while the other hand is stuck into the socket, and that's how we write articles. Totally speaking, this has become an electrified way of writing.

(12) 后来我说合着这花是给你买的我说, 她说来个玫瑰浴自己。

Houlai wo shuo hezhe zhe

After I say totally speaking this

hua shi gei ni

flower is give you

mai de

buy (auxiliary word)

wo shuo, ta shuo lai

I say she say make

ge meigui yu gei ziji.

(measure word) rose bath give self.

Later I said, totally speaking, you bought the flower for yourself. She said she would use the flowers to have a rose bath for herself.

Among the above examples, in (7) and (8) the pragmatic function of “hezhe” is to convey the mood of “unexpected,” and the reason behind “unexpected” is that the information violates the speaker's psychological expectation. It should be noticed that here we use “expectation” not as “hope” or “wish,” but only when the expression following “hezhe” is against the original guess or imagination of the speaker shall we mark it as “unexpected,” which is different from the situation that the speaker himself/herself have hoped or wished to happen, or what is beneficial to him/her. In detail, “hezhe” in (7) means that “I” didn't expect old couples could pass the test, and “hezhe” in (8) means that the money I thought I had saved was unexpectedly not deposited. The “hezhe” of (9) and (10) complete a pragmatic function of “criticism,” which is caused by violating the generally recognized common sense. For example, “hezhe” in (9) criticizes that people listening to it should not make money on both sides, and “hezhe” in (10) criticizes that people listening should not regard their son as a source of money. The “hezhe” of (11) and (12) performs the pragmatic function of producing the effect of “humor,” which is based on the intentional violation of communication conventions. In (11), the humorous effect comes from the intentional violation of the common sense shared by both parties (it is impossible to write in this “electric” way), and the humor of (12) comes from the intentional violation of the facts shared by both parties (the flowers are actually bought by her as a present for ”me“).

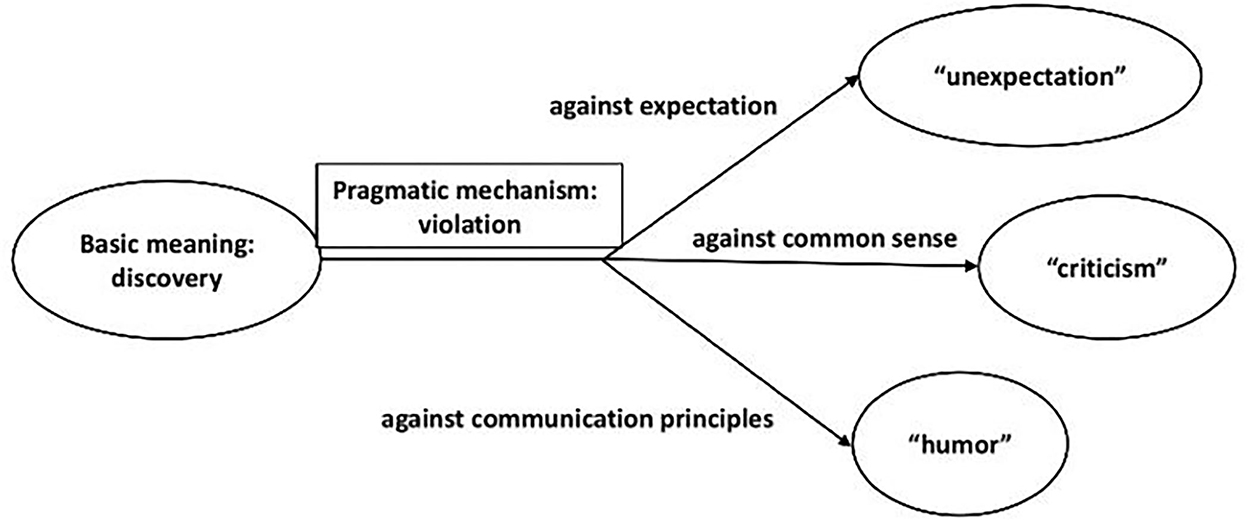

It can be seen that when “hezhe” is used as a pragmatic function, its core mechanism lies in violating people's particular habitual thinking or certain laws. How did this pragmatic function develop? We believe that this can be traced back to the role of verbal communication. Because the basic meaning of “hezhe” is used to express the results achieved by calculation, and in daily verbal communication, the results of “unconventional” or “beyond convention” will attract people's attention and have a higher value of information exchange. Therefore, “hezhe” has gradually emerged with a series of pragmatic functions based on “violation” in communication, which has also transformed it from a simple quantitative adverb to a mood adverb. This is a typical example of the effect of verbal communication on the development of the pragmatic function of adverbs.

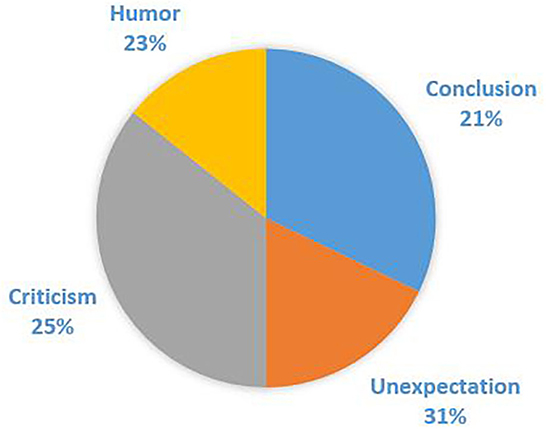

The above meanings and pragmatic functions of “hezhe” are shown in Figure 1.

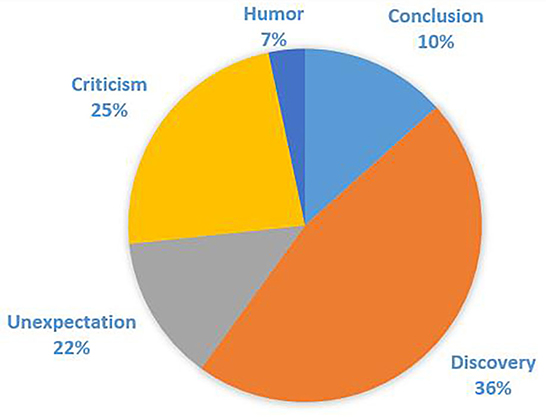

Among the 368 cases of “hezhe” in corpora, 77 cases were used as the basic meaning of “conclusion,” while 291 cases were used as pragmatic functions, including 116 cases expressing “unexpectation,” 91 cases of “criticism,” and 84 cases of “humor.” Their distribution is shown in Figure 2.

It can be seen that the basic meaning “conclusion” of “hezhe” is still used, yet its proportion ranks lowest compared to other mood functions. Among other usages generated by communication, “unexpectation” is the most frequent pragmatic function, and the proportions of “criticism” and “humor” are a little lower.

In addition to the adverbs of “conclusion,” are there other words that can repeat this path and develop similar pragmatic functions in verbal communication? In the following sections, we will explore the other adverbs with similar functions so as to make sure whether they had the same evolving process as “hezhe.”

Semantic and pragmatic analysis of “ganqing” (敢情)

The basic semantic meaning of “ganqing” in the Modern Chinese Dictionary (7th Edition) is “indicating the information that has not been found before.” According to previous research and case distribution from the corpora, we summarize the basic meaning as “discovery,” and such discovery always happens on the basis of the information before, thus rendering it the basic function of “sum-up.” In the ancient Chinese corpus, nearly two-thirds of the “ganqing” cases belong to this basic meaning. Of the 833 cases in the contemporary corpora, there are 422 cases of this basic usage. For example:

(13) 记者仔细一问, 敢情是家里孩子出状况了!

Jizhe zixi yi wen, ganqing

reporter thoroughly once ask the truth is

jia li

home inside

haizi chu zhuangkuang le!

children happen issue (past tense)

The reporter inquired them thoroughly, and found out the truth that their children had some emergent issues at home.

(14) 听了半天, 敢情人家这楼上一直有个心结。

Ting le bantian, ganqin

listen (past tense) half a day the truth is

renjia zhe

they this

loushang yizhi you ge

upstairs always have (measure word)

xinjie.

obsession

Listening for a long time, we finally found out the truth: the people upstairs have always had something unsatisfied.

(15) 齐先生一查, 原来是当地有人跟他同名同姓, 敢情是银行弄错了。

Qi xiansheng yi

(family name) Mr. once

cha, yuanlai shi

investigate turn out to be is

dangdi

local

you ren gen

have person with

ta tongmingtongxing, ganqing

him have the same name the truth

shi

is

yinhang nong cuo le.

bank do wrong (past tense)

Mr. Qi had made some investigation and it turn out to be that there's a local person with the same name as him, so the truth is that the bank had made a mistake.

The above three cases all indicate that some information was found after certain inquiries or investigations. In actual verbal communication, the information often found is the result that is inconsistent with some expectations held by the speaker before. Therefore, some functions similar to “hezhe” appears in pragmatics, which can be divided into several categories depending on the object it violates. For example:

(16) 专家的解释我们倒是第一次听说, 以前光害怕手机辐射人了, 敢情人也能干扰手机啊。

Zhuanjia de jieshi women

Expert of explanation we

daoshi diyici tingshuo

are the first time hear

yiqian guang haipa shouji

before only fear cellphone

fushe ren le

radiation people past tense)

ganqing ren ye neng

unexpectedly people also can

ganrao shouji

interfere cellphone

a.

(exclamation particle)

The explanation of experts is quite new to us, since we only fear the radiation of cellphones to people before. Unexpectedly, people can also interfere cellphones.

(17) 原来光以为执著是个好词儿, 敢情执着如果用错了地方, 也会给人惹麻烦。

Yuanlai guang yiwei zhizhuo

before only think persistent

shi ge hao ci’er

is (measure word) good word

ganqing zhizhuo ruguo yong

unexpectedly persistent if use

cuo le difang,

wrong (past tense) place

ye hui gei ren tian mafan.

also will give peole add trouble

I only thought “persistent” is a good word before. But unexpectedly, if persistence is used in wrong place, it could make people trouble, too.

(18) 可让他没有想到的是, 敢情这足球还真不是一般人能搞的, 扔钱都不带响。

Ke rang ta meiyou

but let him not

xiangdao de shi,

expect (auxiliary word) is

ganqing zhe zuqiu hai

unexpectedly this soccer still

zhen bushi yiban ren

really isn't ordinary people

neng gao de,

can do (auxiliary word)

reng qian dou bu dai xiang.

throw money all not with sound.

But something surprised him. Unexpectedly, the soccer is not a sports for ordinary people, to which your invest disappeared without any trace.

In examples (16–18), the new information found by the speakers is inconsistent with their original cognition, in (16) the speaker thought that “only mobile phones can radiate people;” in (17) the speaker thought that “persistence is a good thing;” and in (18) “he” thought that “ordinary people can invest in football.” Therefore, the pragmatic function of “ganqing” is to highlight the “violation” of these previous expectations. This pragmatic function can be summarized as “unexpectation,” which is similar to the first type of function developed by “hezhe” in communication. There are 109 cases of these functions in the corpora.

The second kind of pragmatic function of “hezhe,” which indicates the violation of the recognized knowledge of things or actions, resulting in the meaning of “criticism,” also appears in the corpora. For example:

(19) 毕竟他是经济学博士, 行贿的巴能军也是经济学博士, 敢情人家学经济主要脑子用这儿了。

Bijing ta shi jingjixue

after all he is economics

boshi, xinghui de Ba Nengjun

doctor bribery (auxiliary word) (name)

ye shi jingjixue boshi,

also is economics doctor

ganqing renjia xue jingji

you dare say they study economics

zhuyao naozi yong zher le.

mainly mind use here (past tense)

After all he is a Doctor of Economics, so is Ba Nengjun who has committed bribery. You dare say, they study economics just to use their knowledge here.

(20) 这话翻译过来就是:邮政法只管邮政局, 不管快递公司。乖乖, 敢情邮政法是国家邮政企业的专用马甲。

Zhe hua fanyi guolai jiushi:

this words translate around is

youzhengfa zhi guan

Postal Law only regulate

youzhengju, bu guan

post office not regulate

kuaidi gongsi. Guaiguai,

express company (exclamation particle)

ganqing youzhengfa shi

you dare say Postal Law is

guojia youzheng qiye

country post industry company

de zhuanyong majia

(auxiliary word) specialized tag

These words mean: Postal Law regulates only the post offices, not express companies. Good heavens! You dare say, Postal Law is the special tool of national post companies.

(21) 教育厅前些日子刚发文说义务教育阶段‘零收费’, 敢情不收学费改卖衣服了。

Jiaoyuting qian

Department of Education before

xie rizi

(measure word of plural form) day

gang fa wen

just publish decree

shuo yiwujiaoyu jieduan

say compulsory education stage

“ling shoufei,” ganqing

zero charge you dare say

bu shou xuefei

no charge tuition fee

gai mai yifu

change sell clothes

le.

(past tense)

The decree issued by Department of Education days before said that no fees should be charged during the stage of compulsory education. You dare say, they change from charging tuition fees to selling clothes.

In (19), the practice of “Doctor of Economics” violated the principle of “people who study economics should also abide by laws.” In (20), the post office's response violated the principle that “the Postal Law should apply to all express companies.” In (21), the practice of collecting clothing fees from students violated the provision of “zero charge in the compulsory education stage.” Therefore, “ganqing” in the above cases conveys the pragmatic function of “criticism” of such behaviors. There are 147 such cases in the corpora.

In the cases of “ganqing,” there are also practices of deliberately violating the conversational principles to obtain the effect of “humor.” For example:

(22) 爱尔兰政府首先回过味来了, 敢情对付金融危机就像鲁提辖三拳打死镇关西。

Aierlan zhengfu shouxian

Ireland government first

huiguowei lai le,

understand around (past tense)

ganqing duifu jinrong

you dare say combat financial

weiji jiu xiang

crisis just like

Lu Tixia

(family name) (government position)

san quan

three fist

da si

beat die

Zhen Guanxi.

(nick name)

The Irish Government first understood that to combat financial crisis is just like Lu Tixia beating Zhen Guanxi to death with three hits (in Chinese traditional legend).

(23) 看看,一个个,全是不同年代的老式收音机,敢情就这么个组合音响啊?

Kankan, yi

look one

gege quan

(measure word in plural form) all

shi butong

are different

niandai

period

de laoshi

(auxiliary word) old style

shouyinji, ganqing

radio you dare say

jiu zheme

just such

ge

(measure word)

zuhe yinxiang a?

stereo system (exclamation particle)

Look. These, one by one, are all old style radios of different periods. So that's what you call a stereo system?

(24) 鹅的确也能看家, 那敢情公鸡中的战斗机, 战斗的本领是从鹅那儿学会的。

E dique ye neng kan

goose surely also can protect

jia, na ganqing

home then you dare say

gongji zhong de zhandouji,

rooster inside (auxiliary word) fighter

zhandou de

fight (auxiliary word)

benling shi cong e naer

ability is from goose there

xue hui de.

learn master (auxiliary word)

The geese surely can protect your home as well. Thus, did the most brave fighters of the roosters learn their skills from the geese?

Case (22) deliberately violated the Maxim of Quality from the four Cooperative Principles (Grice, 1975) and used a Chinese traditional story to describe the psychological activities of a foreign government, which achieved the effect of humor. Similarly, case (23) violated the fact that “several radios do not constitute a stereo system.” Case (24) violated the fact that a goose can't teach a rooster to protect the house. In these examples, “Ganqing” conveys the pragmatic function of “humor” in a way that violates the Maxim of Quality, that is, not to say what you believe to be false, or to say that for which you lack adequate evidence. There are 155 cases of this usage in the corpora.

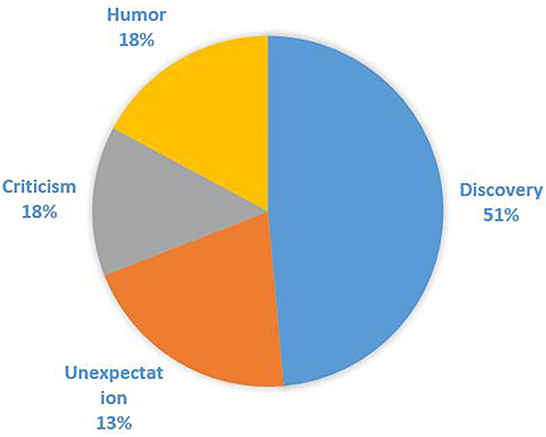

To sum up, the adverb “Ganqing” started with the basic meaning “discovery,” through the “emergence” of pragmatic functions in communication similar to “hezhe,” and finally acquired almost the same pragmatic function system, including “unexpected” “criticism” and “humor,” as is shown in Figure 3.

Such usages of “ganqing” are distributed as shown in Figure 4.

Compared with “hezhe,” the original meaning “discovery” of “ganqing” occupies an absolutely dominant position, while the frequencies of the other three pragmatic functions decrease gradually from “humor” (155 cases), “criticism” (147) to “unexepectation” (109), but there is little difference.

It is the mechanism of verbal communication that enables “hezhe” and “ganqing” with different original meanings to obtain similar pragmatic functions. In real communication, the conclusion of facts and the discovery of new facts from the given information are easy to lead to the function of “sum-up,” then to the violation of some psychological expectations, common sense, and communication conventions. Therefore, the above two words have formed similar pragmatic functions. Whether this inference is true or not, we need to introduce other words to further verify.

Semantic and pragmatic analysis of “nao le bantian(guiqi)” (闹了半天(归齐))

”Nao le bantian” is also a common colloquial phrase. Its original meaning is “make trouble for a period of time (and get some results)“. In the ancient Chinese corpus, this original usage is seen in almost 70% of all instances. In the contemporary corpora, there are still examples of such usage:

(25) 咱们吵了半天闹了半天, 最后大家停下来都去捧读曹雪芹的原著, 我的目的就达到了

Zanmen chao le bantian

We argue (past tense) half a day

nao le bantian,

make trouble (past tense) half a day

zuihou dajia ting xialai dou qu

at last everyone stop down all go

peng du Cao Xueqin de

hold read (name) (auxiliary word)

yuanzhu

original work

wo de mudi jiu

we (auxiliary word) purpose just

dadao le.

achieve (past tense)

We have argued for a long time, and if at last everyone could stop and take an original work of Cao Xueqin to read, then my purpose will be achieved.

(26) 因为现在闹了半天, 之所以闹了才派了几十个人去, 做了很大的文章。

Yinwei xianzai nao le

Because now make trouble (past tense)

bantian, zhisuoyi nao

half a day the reason of make trouble

le cai pai le

(past tense) only send (past tense)

ji ge ren qu,

several (measure word) people go

zuo le hen da

make (past tense) very big

de wenzhang.

(auxiliary word) article

Not until the trouble had been made for a long time did several dozen people were sent and made it a big issue.

(27) 小区的业主委员会就说这个管理公司什么什么有问题, 闹了半天, 闹到最后全部业主同意我们不交管理费。

Xiaoqu de yezhu

housing estate (auxiliary word) owner

weiyuanhui jiu shuo

committee just say

zhege

this

guanli gongsi shenmeshenme

manage company something

you wenti, nao

have problem make trouble

le

(past tense)

bantian, nao dao zuihou

half a day make trouble to last

quanbu yezhu tongyi women

all owner agree we

bu jiao guanli fei.

not hand in manage fee

The house owners of this estate said the management company had all kinds of problems. After making trouble for a long time, at last, all the owners agreed that they wouldn't hand in the management fee.

In these cases, “nao le bantian” is a verb phrase in its original meaning, which has not been integrated into a special mood component. Therefore, it was not included in the scope of effective cases in our analysis and statistics. Except for these, there were still 82 cases of “nao le bantian” used as a mood adverb. In addition, we also found 1 case of “nao le guiqi,” a mood adverb with a similar meaning yet often appearing in the North dialect.

In these cases, the extended meaning closest to the original is the meaning of “conclusion” directly evolving from the meaning of “result,” that is, the meaning of “conclusion obtained over a period of time” was derived from the “result of trouble over a period of time.” This meaning is similar to the basic meaning of “hezhe.” There are eight such cases in the corpora. For example:

(28) 老板说得兴起, 可是, 闹了半天, 这价钱怎么样啊, 说着, 老板拿给我们一张价目表。

Laoban shuo de xingqi,

boss say (auxiliary word) excited

keshi, nao la bantian, zhe jiaqian

but to sum up this price

zenmeyang

how

a, shuo zhe,

(question particle) say (progressive tense)

laoban na gei

boss take give

women

we

yi zhang jiamiu biao.

one (measure word) price list

The boss talked excitedly. However, to sum up, how is the price? While talking, the boss gave us a price list.

(29) 闹了半天, 你拐了半天, 怎么, 结论拐到哪去了?

Nao le bantian, ni guai le

to sum up you go around (past tense)

bantian, zenme, jielun

half a day how conclusion

guai dao na qu le?

go around to where go (past tense)

To sum up, your talking has been winding for a long time, then, what is your conclusion?

(30) 所以说这事要解决的话, 闹了归齐, 说到底, 还是个公德问题。

Suoyishuo zhe shi yao

So this issue will

jiejue dehua, nao le guiqi,

solve if to sum up

shuo dao di,

speak to essence

hai shi ge gongde

still is (measure word) social morality

wenti.

problem

So if this issue wants to be solved, to sum up, after all, this is a problem of social morality.

In case (28), the speaker hopes to conclude “what's the price” after a period of discussion; in (29), the speaker directly expresses his desire to “draw a conclusion“; in (30) “nao le guiqi” directly comes to the conclusion that “this is a problem of social morality.” In another direction, starting from the meaning of “result,” the meaning of “discovery” has also been developed, that is, “new information has been found after a certain process.” This meaning is similar to the basic meaning of “ganqing.” There are 30 such cases, for example:

(31) 听明白了吧, 闹了半天, 是这辆小车违章。

Ting mingbai le

listen clear (past tense)

ba, nao le ban tian,

(exclamation particle) the truth is

shi zhe liang

is this (measure word)

xiaoche weizhang.

car break the rules

Do you understand now? The truth is that it was this car that broke the rules.

(32) 闹了半天, 原来是韩女士在更年期的时候没注意补充营养, 才染上的毛病。

Nao le bantian, yuanlai shi

the truth is turn out to be is

Han nvshi zai gengnianqi

(family name) Ms. in menopause

de shihou mei

(auxiliary word) time not

zhuyi buchong yingyang,

pay attention add nutrition

cai ran shang de maobing.

only incur get (auxiliary word) illness

The truth is that Ms. Han didn't pay attention to take in enough nutrition during her menopause, thus developing the illness.

(33) 隔壁邻居也跟着起急。闹了半天, 罪魁祸首在这儿呢, 看看, 水漏得还挺凶。

Gebi linju ye

next door neighbor also

genzhe qiji. Nao le bantian

together worry the truth is

zuikuihuoshou

arch-criminal

zai zher ne,

in here (exclamation particle)

kankan, shui lou

look water leak

de

(auxiliary word)

hai ting xiong.

still quite serious

The neighbors next door were also worried together. The truth is, here is the source of the problem. Look, the water is leaking quite seriously.

Starting from the similar meanings and “sum-up” function, “nao le bantian(guiqi)” has had a development path similar to “hezhe” and “ganqing.” In the corpora, we found 18 cases of “unexpectation” function, which stemmed from the situation that “conclusion” and “discovery” often “violates” the expectations of communication participants, such as:

(34) 记者正纳闷呢, 有人说了, 这其实不是真结婚, 什么?闹了半天是假的?

Jizhe zheng namen

Reporter in process of confused

ne, youren shuo

(exclamation particle) someone say

le, zhe qishi bu shi

(past tense) this actually not is

zhen jiehun, shenme?

real get married what

Nao le bantian shi jiade?

unexpctedly is false

The reporter was confused, and someone said, this is actually not a real wedding. What? Unexpectedly, this is false?

(35) 边上有人说了句话, 让我们大感意外。什么?闹了半天白激动啦。

Bianshang youren shuo

Aside someone say

le ju hua,

(past tense) (measure word) words

rang women da gan

let we very feel

yiwai. Shenme?

unexpected what

Nao le bantian bai jidong le.

Unexpectedly in vain excited (past tense)

Someone beside me said something that made us feel so surprised. What? Unexpectedly, we had been excited in vain?

The function of “criticism” which emerged from the “violation” of common sense appeared in 21 cases. For example:

(36) 老百姓说闹了半天, 国家政府、我们选举出来的总统居然骗我们。

Laobaixing shuo nao le bantian,

Civilians say ironically

guojia zhengfu, women

country government we

xuanju

elect

chulai de zongtong

out (auxiliary word) president

juran pian women.

unexpectedly cheat us

The civilians said that ironically, the country, the government, and the president we elected unexpectedly cheated us.

(37) 闹了半天, 原来自己就是井盖的负责人, 自己的井盖子自己都不知道。

Nao le bantian, yuanlai ziji

Ironically turn out to be self

jiushi jinggai de

is drain cover (auxiliary word)

fuzeren,

person in charge

ziji de jinggaizi

self (auxiliary word) drain cover

ziji dou bu

self even not

zhidao.

know

Ironically, they themselves are in charge of this drain cover. They even don't know their own drain covers.

(38) 闹了半天, 全是低层次的、粗鲁的、野蛮的竞争, 你不能提高层次。

Nao le bantian, quan shi

Ironically all are

di cengci de,

low level (auxiliary word)

culu de,

rude (auxiliary word)

yeman de jingzheng,

barbarous (auxiliary word) competition

ni buneng tigao

you can't enhance

cengci.

level

After all, these are all rude and barbarous competitions of a low level, and you can't enhance them.

There is 6 cases of “humor” due to “violation” of Cooperative Principles:

(39) 敢情就是这么一个法制, 想着法的制人, 这就是他们所谓的法制, 闹了半天, 人家是这么理解的。

Ganqing jiushi zheme

you dare say is such

yi ge fazhi,

one (measure word) legality

xiang zhe fa

think (progressive particle) method

de zhi ren,

(auxiliary word) bully people

zhe jiushi tamen suowei

this is they say

de fazhi, nao le bantian,

(auxiliary word) legality after all

renjia shi zheme lijie de.

they are so understand (auxiliary word)

You dare say, this is their ‘legality’, that is, using all methods to bully you. This is the ‘legality they mean. After all, this is their understanding.

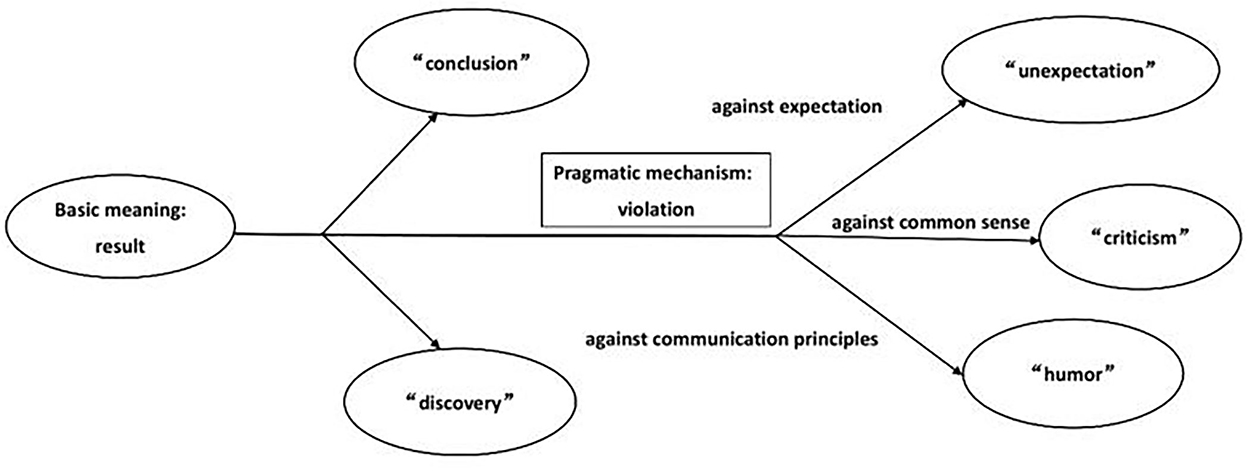

In (39), “nao le bantian” is also used together with “ganqing,” which proves that they are similar in pragmatic functions and strengthens the effect of ”humor.” To sum up, starting from a simple verb phrase, “nao le bantian (guiqi)” gradually obtains extended meanings similar to the original meanings and basic function of “hezhe” and “ganqing,“ then grammaticalized into a fixed phrase similar to an adverb, and produced pragmatic functions similar to the former two words through verbal communication. The changing path of its semantic meanings and pragmatic functions is shown in Figure 5.

The distribution of meanings and pragmatic functions of “nao le bantian(guiqi)” in corpora is shown in Figure 6.

As for “nao le bantian,” the meaning of “discovery” is the most used in the corpora, followed by the function of “criticism” and “unexpectation,” “conclusion” and “humor” still fewer.

The summary of “sum-up” mood adverbs

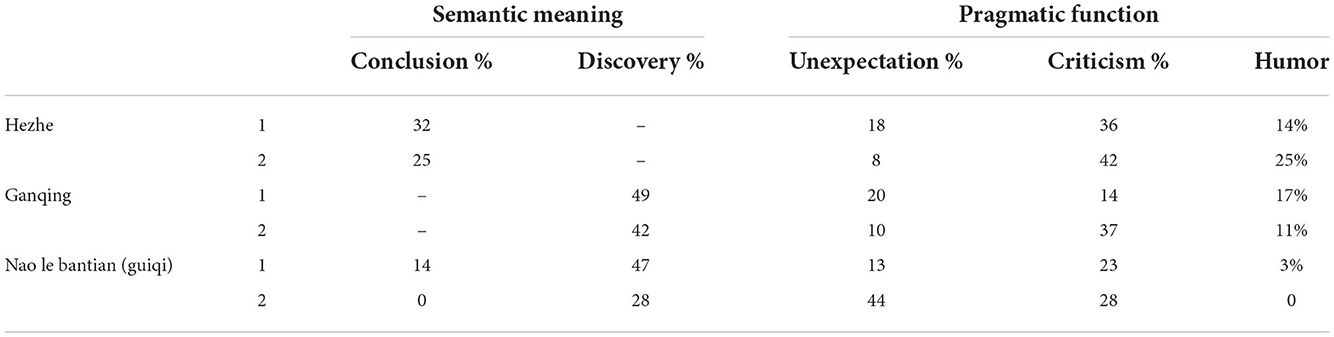

So far, we have clarified the semantic and pragmatic functions of the mood adverbs “hezhe” and “ganqing,” as well as the phrase “nao le bantian(guiqi).” We can see that, due to the motivation of verbal communication, words with different original meanings can also accept the influence of the same pragmatic mechanism and “emerge” with similar functions to make them “come to the same goal by different paths.” From the meanings of “conclusion,” “discovery” and “result,” the above three words have moved from “sum-up” function through the mechanism of “violating” some inherent standards, and then produced three corresponding pragmatic functions that not only help to convey information, but also convey a specific tone of the speakers. The distribution of the semantics and pragmatic functions of the three mood words are summarized as in Table 1.

It should also be noted that the emergence of pragmatic function is a “self-organization” phenomenon spontaneously emerging from communication behavior. It has a certain randomness in which select words are used in peculiar directions and to specific extents. Therefore, not all words with the meaning of “conclusion” will produce the pragmatic function of “violation” (e.g., zongzhi), neither will all words with the meaning of “discovery” evolve along this path (e.g., yuanlai).

To further verify the effect that communication style has on the pragmatic distribution of the above words, we compared corpus 2 with corpus 1. The rate of the total number of characters between corpus 1 (MLC) and corpus 2 (script) was about 330:1, while the ratio of the three adverbs: 1.17:1, 11.1:1, and 4.71:1. It can be seen that these three words appear much more intensively in corpus 2, which is because corpus 2 is created by imitating the dialogue in ordinary family life in Beijing, and therefore such mood adverbs are used more frequently than in interview programs. Compared with the overwhelming advantage of “hezhe” in corpus 1, there is little gap between “hezhe” and “ganqing” in corpus 2, although the former appears a little more, which may be due to the role of the dialect region. “Nao le bantian” is still relatively few, and there is no “nao l guiqi.” The specific distribution of the three words in corpus 2 was compared with the data obtained in corpus 1, as shown in Table 2.

It can be seen from Table 2 that in both corpora, the basic meaning of “conclusion” occurs quite often but not in the highest frequency. The most frequently used pragmatic function is “criticism“. However, because corpus 2 is a comedy style, the frequencies of “criticism” and “humor” are higher, and the proportion of “unexpectation” is relatively low. For example:

(40) 这一辆车呀, 也能合着五六万块钱哪。

Zhe yi liang

this one (measure word)

che ya, ye

car (exclamation particle) also

neng

can

hezhe wu liu

totally five six

wan kuai qian

10,000 (currency unit) money

na.

(exclamation particle)

This car, totally calculated, is worth 50 to 60 thousand yuan (”conclusion“).

(41) 嘿, 合着我这姑妈到现在还不知道有我这么一个人呢。

Hei, hezhe wo zhe

(exclamation word) unexpectedly mine this

guma dao xianzai hai

aunt till now still

bu zhidao you

not know have

wo zheme yi

I such one

ge ren ne.

(measure word) person (exclamation particle)

Oh my! Unexpectedly, this aunt of mine still doesn't know that I exist (”unexpectation“).

(42) 那您呢? 合着您就什么都不管啦?

Na nin ne? Hezhe

then you (question particle) totally

nin jiu shenme dou

you just what all

bu guan la?

no take on (question particle)

How about you? Totally speaking, you don't take on any affairs at home? (”criticism“).

(43) 哎嗨嗨, 合着你们家祖宗是一太监。

Aiheihei, hezhe nimen jia

(exclamation word) totally your family

zuzong shi yi taijian

ancestor is one eunuch

Good heavens, totally speaking, your ancestor was an eunuch (”humor“).

”Hehze” in (40) is the conclusion of the money calculation. (41) is the youngest son of the family who is surprised that his aunt doesn't know about his existence. (42) criticizes the attitude of “doing nothing” as a family member, and the obvious impossibility of “the ancestor is an eunuchs” in (43) is to obtain the effect of humor.

Of all “ganqing” in the two corpora, the frequency of the basic meaning “discovery” appears the highest—more than two-fifths. Among the later emerging pragmatic functions, corpus 2 still has more “criticism.” “Unexpectation” and “humor” are slightly lower than those in corpus 1. For example:

(44) 噢我说呢, 敢情这小时候就有事啊。

O wo shuo

(exclamation word) I say

ne, ganqing zhe

(exclamation particle) the truth is this

xiaoshihou jiu you

childhood already have

shi a.

affair (exclamation particle)

Oh, so I see. The truth is, you two had affairs since childhood (”discovery“).

(45) 不是你说这么热闹敢情是一倒卧呀?

Bushi ni shuo zheme renao

Oh no you say so exited

ganqing shi yi daowo

unexpectedly is one beggar

ya?

(exclamation particle)

What? You described him so brilliant but unexpectedly he is a beggar? (”unexpectation“).

(46) 嘿, 你这不倒霉催的么, 敢情好人全让这局长给干了, 啊, 坏人全让你给当了。

Hei, ni zhe

(exclamation word) you this

bu daomeicui de

not unfortunate (auxiliary word)

me,

(exclamation particle)

ganqing haoren quan rang zhe

you dare say good man all let this

juzhang gei gan le,

director give do (past tense)

a, huairen quan rang

(exclamation word) bad guy all let

ni gei dang le.

you give be (past tense)

Hey, you are so unfortunate. You dare say, the Director become the only good man, and just you are the bad guy (”criticism“).

(47) 敢情是金子搁哪儿都发光!是葵花长哪儿都向阳!

Ganqing shi jinzi ge

You dare say is gold put

naer dou faguang!

where all shine

Shi kuihua zhang naer

Is sunflower grow where

dou xiang yang!

all toward sun

You dare say, the gold will shine no matter where you put it! And the sunflower will be toward the sun no matter where you grow it! (”humor“).

In (44), “ganqing” indicates the speaker just found some new information. In (45), the speaker was surprised that his family had brought back a beggar. (46) criticized the selfish behavior of the “Director,” and (47) commented on the fact that an elderly man over 60 years old was looking for a lover again. The idiom quoted in (47) was inconsistent with the event itself, so the effect of humor was achieved.

”Nao le bantian” appears fewer times in corpus 2 and has a narrow scope of use. The functions of “conclusion” and “humor” are not used. For example:

(48) 好哇, 闹了半天是你们干的!

Hao wa, nao le bantian

Good (exclamation particle) the truth

shi nimen gan

is you do

de!

(auxiliary word)

Good! It turned out to be you who did it! (”discovery“)

(49) 志新:原先我还真以为我喜欢她, 闹了半天……

Zhixin: Yuanxian wo hai

(name): before I still

zhen yiwei wo xihuan ta,

really think I like her

nao le bantian…

unexpectedly

胡三:呸!

Husan: Pei!

(name): (exclamation word)

志新:我还真喜欢她……

Zhixin: wo hai zhen xihuan ta…

(name): I still really like her

Zhixin: I thought I really liked her before, but it turned out that…

Husan: Oh!

Zhixin: I really like her…(”unexpectation“)

(50) 我在外头整天奔命似的我给谁奔哪?闹了半天我给你奔哪!我该你的我是欠你的?

Wo zai waitou zhengtian

I in outside all day

benming shide wo gei

strive like I give

shui ben na?

who strive (question particle)

Nao le bantain wo gei

Ironically I give

ni ben na!

you strive (exclamation particle)

Wo gai nide wo shi qian nide?

I own your I am in debt your

I strive to earn money all day with my life outside home, and for whom do I do this? Ironically, I strive for you! Do I own you a debt? (”criticism“).

Case (48) shows that the speaker has finally discovered the originator of the incident, and the speaker in case (49) is surprised that he suddenly realizes his true feelings. It is worth noting that case (49) inserted another turn between “nao le bantian” and the subsequent unexpected result. This long pause and foreshadowing highlighted the sense of “unexpectation” and achieved dramatic effects. In (50) it is the hostess of the family who criticizes that the housekeeper's salary is too high and thinks that all the money she earns is paid to the housekeeper, which she believes is improper.

To sum up, the previous categorization of the semantic meanings and pragmatic functions of “hezhe,” “ganqing,” and “nao le bantian (guiqi)” has appeared in corpus 1 and 2 in different ways of distribution. Such differences were possibly due to different occasions and genres, and especially due to different origins of dialect regions since corpus 2 depicts the oral communication of people from Beijing, a city that holds its own dialect traits. The above findings evinced the complex nature of oral interaction. Gathering a larger number of cases and differentiating various genres and dialect regions will be an interesting topic for further research.

Conclusion

This study chose three common adverbs (or phrases) in oral communication, “hezhe,” “ganqing,” and “nao le bantian (nao le guiqi).” Through the analysis of cases from five corpora, it was found that although their original meanings are different, they all go from the basic function of “sum-up” through the mechanism of “violation” in verbal communication and produce the pragmatic functions of “unexpectation,” “criticism,” and “humor.” We categorized such words as “sum-up“ mood adverbs.

Ancient and contemporary corpus statistics reveal the origins and distributions of different functions of the three words, and the comparison between MLC and script corpus also shows that the distribution proportion of various functions will be different on the premise of different communication nature and purpose. For example, the proportion of “critical” and “humor” functions tends to rise in comedy scripts with satirical and humorous effects.

The conclusion of this paper reflects the influence of verbal communication on the meaning and function of words. Through the analogy of similar psychological mechanisms, words with different original meanings may “emerge” with similar pragmatic functions through long-term use. Especially for the category of mood words, which is inseparable from the communication process and highlights the vividness of oral language, it is necessary to break the traditional simple classification based on semantics and explore their function and usage from practical communication. In the future, it is expected to expand the research scope to more types of oral corpora to reveal the influence of communication modes on the distribution of word functions, considering the factor of the genre, dialect, etc. And there are still other words and phrases that could obtain a similar “sum-up” function and mood functions to the words considered in the paper, such as “shuo dao di” (说到底, to speak to the bottom), and “shuo bai le” (说白了, to speak clearly), the study of which could enrich the category of “sum-up” and become the resources of comparison among such words.

In addition, in TCSOL, more attention should be paid to words from dialects such as “hezhe,” “ganqing” and “nao le bantian (nao le guiqi).” At present, only few studies such as Ding (2003) have discussed the teaching of dialect words. In second language learners' Chinese discourse, as in HSK corpus, neither “hezhe” nor “ganqing” as adverbs has been used, while “nao le bantian” appeared only once, in original meaning as a verbal phrase:

(51) 可是闹了半天, 究竟敌不过爸爸, 她只好哭一阵。

keshi nao le bantian, jiujing di

but make a fuss for quite a while at last contend

bu guo baba,

not over father

ta zhihao ku yi zhen

she only cry a while

She made a fuss for quite a while but at last couldn't defeat my father, and she could only cry for a while.

With the development of China's international exchange, the continuous expansion of high-level Chinese learners, and the increasing use of film, television, and entertainment works as materials for Chinese teaching, more and more learners will be widely exposed to daily used oral words. Some of these words have entered the vocabulary syllabus, and more are to be included. Therefore, based on the conclusions of this research, dialect words can be appropriately selected and supplemented in TCSOL classes, especially for speaking classes of intermediate and advanced levels, and the instruction design of such words can be carried out in combination with their pragmatic functions to reflect the practical and communicative principles of TCSOL.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^It should be noted that “nao le bantian” is actually a phrase in the perspective of traditional grammar. Yet in this study it perform the pragmatic functions as an integrated entity, just like so-called “discourse marker.” So for the convenience of narrating, in this paper we will call it “mood adverb” as well.

References

Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Selting, M. (2018). Interactional Linguistics: An Introduction to Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781139507318

Dictionary Compilation Office Institute of Language, and Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. (2016). Modern Chinese Dictionary, 7th Edn. Beijing: Commercial Press.

Ding, Q. (2003). The relationship between Chinese dialects and teaching Chinese as a second language. Lang. Teach. Linguist. Stud. 58–64.

Fang, D. (2018). 互动视角下的汉语口语评价表达研究 (Research on Chinese Oral Evaluation Expression From the Perspective of Interaction). Doctoral Dissertation of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFDLAST2019&filename=1018973191.nh

Fang, M. (2005). 篇章语法与汉语篇章语法研究 (Text grammar and the study of Chinese text grammar). Soc. Sci. China. 165–172.

Fang, M., Li, X., and Xie, X. (2018). Interactional linguistics and Chinese studies in interactional perspectives. Lang. Teach. Linguist. Stud. 1–16.

Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and conversation,” in Speech Acts, eds P. Cole, and J. Morgan (New York, NY: Academic Press).

Han, X. (2014). 浅析语气副词 “敢情” (On mood adverb “Ganqing”). J. Mudanjiang Norm. Univer. 92–95. doi: 10.13815/j.cnki.jmtc(pss).2014.04.032

Liu, T. (2012). Analysis of Beijing Dialect Word “Hezhe” From Several Angles. Master's thesis of Shanghai Normal University. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201301&filename=1012456437.nh

Nan, Y. (2019). 浅析语气副词” 敢情”的历时变化 (A diachronic study on mood adverb “Ganqing”). Sinogram Cult. 8-9+18. doi: 10.14014/j.cnki.cn11-2597/g2.2019.11.004

Qi, H. (2002). 论现代汉语语气系统的建立 (On the Establishment of Modern Chinese Mood System). Chinese Language Learning, 1–12. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-7365.2002.02.001

Wang, K. (2014). Analysis of Beijing Dialect Word “Ganqing” From Several Aspects. Master's thesis of Guangxi Normal University. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201402&filename=1014270428.nh

Wu, Y. (2016). The Study on Dialect Adverbs Absorbed Into Mandarin and Teaching Chinese as a Second Language. Master's thesis of Hunan Normal University. Availabe online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201701&filename=1016085623.nh

Yang, L. (2019). Studies on Commentary Adverbs Ganqing (敢情) and Hezhe (合着). Master's thesis of Tianjin Foreign Studies University.

Zeng, G. (2021). 对话语言学: 核心思想及其启示 (Dialogue linguistics: core ideas and implications). Contemp. For. Lang. Stud. 53–60. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-8921.2021.03.006

Keywords: mood adverbs, pragmatics, TCSOL, corpus, modern Chinese linguistics

Citation: Song J (2022) How interaction molds semantics: The mood functions of Chinese “sum-up” adverbs. Front. Psychol. 13:1014858. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1014858

Received: 09 August 2022; Accepted: 04 November 2022;

Published: 30 December 2022.

Edited by:

Swaleha Bano Naqvi, National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), PakistanReviewed by:

Chunxiang Wu, Shanghai International Studies University, ChinaChengwen Wang, Peking University, China

Copyright © 2022 Song. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingyao Song, anlzb25nQHNobXR1LmVkdS5jbg==

Jingyao Song

Jingyao Song