- 1School of Business Administration, Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea

- 2Department of Lifelong Education, Administration, and Policy, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia

- 3School of Business Administration, Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea

- 4Human Resources Development Service of Korea, Ulsan, South Korea

- 5National Assembly Futures Institute, Seoul, South Korea

- 6Graduate School of Education, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea

Job embeddedness (JE) has been recognized as a key factor to address the issue of employee turnover and employee attitudes. This study explores underlying mechanisms of job embeddedness that link the organizational environment and the individuals’ perceptions of the job. Particularly, the effects of psychological empowerment and learning orientation on organizational commitment were examined. This study hypothesizes that psychological empowerment (PE) and learning orientation (LO) should influence organizational commitment (OC) and job embeddedness plays a significant mediating role in these relationships. Data were collected from 27 offices of Human Resource Development Service of Korea (governmental agency) located in major cities in South Korea. Results indicate that all hypothesized relationships (PE and JE, LO and JE, LO and OC, JE and OC, and the mediating role of JE) are supported, except for psychological empowerment and organizational commitment. While the impact of psychological empowerment was not significantly related to organizational commitment, it is notable that through job embeddedness, psychological empowerment had indirect effects on organizational commitment. Further, learning orientation had significant effects on job embeddedness and organizational commitment. Lastly, the most compelling finding is a full mediation of job embeddedness in the relationship between psychological empowerment and organization commitment. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Introduction

Over the past decade, business environments and job markets have become volatile, and the issue of employee turnover persists as a growing concern for many organizations (Mitchell et al., 2001; Holtom and O’neill, 2004; Felps et al., 2009). Job embeddedness (JE) has been recognized as a key factor to address the issue of employee turnover (Mitchell et al., 2001; Crossley et al., 2007; Allen and Shanock, 2013; Sender et al., 2018). To conceptualize job embeddedness, Mitchell et al. (2001) focused on why employees remain and linked the concept to favorable employee attitudes. Job embeddedness is recognized as an individual level phenomenon, and it is based on a balance between perceived costs and psychological benefits. Job embeddedness is also regarded as a key mediating construct between work-related organizational factors and employee attitudes (Li et al., 2016). However, underlying mechanisms that link the organizational environment and the individuals’ perceptions of the job remains unknown (Kiazad et al., 2015). Therefore, this study attempts to reveal the mechanism of how job embeddedness works between organizations and individuals.

Additionally, our aim is that this study extends extant job embeddedness theory to non-Western countries, such as South Korea, because different value systems in specific countries may impact employees’ perceptions in different ways (Williamson and Holmes, 2015; Jordan et al., 2017). Through literature review on embeddedness, Ghosh and Gurunathan (2015) found that existing studies on embeddedness are mostly restricted to the West; however, studies in Asian countries still remained largely unexplored.

The cultural setting in South Korea makes this study meaningful in the job embeddedness literature. That is, this study examined the mediating effects of job embeddedness in a unique cultural setting of Korean corporations, where an organizational culture of hierarchy, collectivism, and masculinity prevails (Hofstede, 1998). More specifically, organizational cultures in Korea encourage employees’ interdependence with the organization, a larger power distance between leaders and subordinates, and putting more emphasis on “off-the-job” factors to explain organizational commitment, in contrast to the organizational factors in Western society (Shore, 2013). Taking into account the importance of this Korean organizational culture as we interpreted the findings of the current study, as such a collectivistic culture could oftentimes notably put pressure on employees into socially obligated organizational behaviors at the workplace, the design for this study strengthened the linkage between psychological empowerment, learning orientation, and organizational commitment through the perception of job embeddedness. Conducting a similar study in Western countries, which hold a different organizational culture with the emphasis on smaller power distance and individualism within corporations and organizations, would help us better understand the significance of the effect of such an meaningful distinctiveness.

Responding to this gap, this study proposes that perceived employees’ psychological empowerment would play a significant role in the organizational commitment that leads to organizational performance, and job embeddedness will mediate this relationship. Specifically, psychological empowerment refers to “psychological motivation reflecting a sense of self-control in relation to one’s work and an active involvement with one’s work role” (Seibert et al., 2011, p. 981). Psychological empowerment is comprised of multidimensional cognitive factors consisting of meaning, self-determination, competence, and impact. Individuals with a feeling of empowerment possess and can rely on a proactive orientation to one’s work roles (Sun L. Y. et al., 2012). Thereby, we argue that psychological empowerment nourishes individual’s job embeddedness, which in turn improves their attitudes towards their organizations.

Another key construct in the proposed mechanism is learning orientation. When employees appreciate the benefits of growth and opportunities from training and learning, they reciprocate such support in the form of positive attitude (Bunderson and Sutcliffe, 2003). In this regard, an employee’s commitment may be the result of a perception that their interests, through learning and development, are supported. However, few researchers have examined the importance of learning orientation with employees’ job embeddedness (Shah et al., 2020). We assume that opportunity-enhancing learning orientation may improve employees’ perception toward the organization further by embedding them in the job. Our study is cognizant that motivational and environmental factors are likely to affect the way job embeddedness relates to employee’s attitude. We explore the mediating role of job embeddedness among psychological empowerment, learning orientation, and organizational commitment.

Along with job embeddedness theory, studies on employees’ organizational commitment (OC) remain an important construct to explaining talent retention and for developing human resources (HR) in organizations (Kontoghiorghes, 2016; Mathieu et al., 2016). Effectively facilitating employee’s commitment by providing psychological empowerment (PE) and promoting learning orientation (LO) is important for enhancing organizational capacity and capability (Bani et al., 2014). Unfortunately, few studies delineate the motivational and psychological effects that explain the development of organizational commitment.

Therefore, this study had two specific goals. First, we sought to extend job embeddedness theory and research on organizational commitment by demonstrating how job embeddedness bridges a link from psychological empowerment and learning orientation. Second, we sought to determine whether the variables of psychological empowerment and learning orientation are predictors of organizational commitment. These two goals address the needs for examining the critical role of motivation and psychological empowerment noted in the job embeddedness literature.

Literature review

Psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment is one of the widely used contextual variables in management research. Increasingly, researchers examine attitudinal and behavioral outcomes, including job performance, in relation to psychological empowerment (Maynard et al., 2014). Conger and Kanungo (1988) proposed that empowerment be viewed as a motivational construct-meaning to enable rather than simply to delegate. Thomas and Velthouse (1990) also empowerment was conceptualized in terms of changes in cognitive variables which determine motivation in workers.

Spreitzer (1995) operationalized theoretical work by creating a measurement of psychological empowerment and proposed a second-order factor of psychological empowerment. It consisted of four dimensions that combined additively to form an overall construct of psychological empowerment. The four dimensions consisted of (1) meaning—the values, beliefs, and work purpose judged by individual’s ideals, (2) competence—an individual’s efficacy specific to accomplish their work role with skills, (3) self-determination—an individual’s sense of initiatives for work behaviors and processes, and (4) impact—the degree an individual can influence work role outcomes at work.

Several previous studies found that psychological empowerment is positively associated with a variety of outcomes. Example attitudinal consequences of psychological empowerment are higher job satisfaction (Spreitzer et al., 1997), higher organizational commitment (Barroso Castro et al., 2008), a reverse relation to job strain (Harley et al., 2007), and lower turnover intention (Griffeth et al., 2000), employee creativity (Matsuo, 2022). Behavioral consequences are a higher level of task performance (Humphrey et al., 2007; Zada et al., 2022), innovation, and managerial effectiveness (Spreitzer, 1995).

Learning orientation

Learning orientation in organizational contexts is defined as “organization-wide activity of creating and using knowledge to enhance a firm’s competitive advantage” (Calantone et al., 2002, p. 516). Watkins and Marsick (2019) employ a cultural perspective of organizational learning that promotes learning capacity to transform as a continuous and strategically used process in formal and, especially, informal learning. Aligning with the concept of a learning organization, learning orientation attempts to connect the organization to its external environment (Watkins and Marsick, 1993).

The operationalization of learning orientation consists of (1) commitment to learning, (2) shared vision, and (3) open-mindedness. First, the main piece of learning orientation is the value placed on learning by an organization (Sinkula et al., 1997). Learning orientation emphasizes the primary means of enhanced capacity to learn and grow. Second, shared vision refers to the direction of learning by providing a focus for learning that assists in the understanding of what needs to be learned (Sinkula et al., 1997). Third, open-mindedness reflects the value that an organization proactively questions the past and regards the future with the ability to change. These organizational characteristics capture how the organization can facilitate or influence an individual employee’s organizational behaviors through structure and environmental atmosphere (Baker and Sinkula, 1999).

Job embeddedness

Job embeddedness refers to “a construct composed of contextual and perceptual forces that bind people to the location, people, and issues at work” (Crossley et al., 2007, p. 1031). The critical aspects of job embeddedness in assessments are internal and external factors that affect individuals’ (a) links to teams and other people; (b) perception of fit with their jobs, organizations, and communities; and (c) likely reactions regarding what they would have to sacrifice if they left their jobs (Mitchell et al., 2001; Kiazad et al., 2015). This last factor was conceived to capture why people remain with the organization against voluntary departure possibilities. Together, these three aspects are labeled as links, fit, and sacrifice on the intricate aspects of community and individual bonds that align with organizational goals and strategies.

Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment refers to “the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization” (Mowday et al., 1982, p. 27). Organizational commitment is a multi-dimensional construct that denotes the relative strength of an individual’s identification, involvement, and loyalty to a particular organization (Meyer and Allen, 1997). Affective commitment reflects an emotional attachment to the organization based on feelings of loyalty toward the employer. Continuance commitment is based on perceived costs of leaving the organization. Normative commitment means a sense of obligation on the part of the employee’s membership in the organization.

Many empirical studies of affective organizational commitment reported positive relationships with job-related experience and organizational factors as antecedents to organizational commitment (Laschinger et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2016; Karim, 2017). For example, job resources that have positive psychological consequences strengthen organizational commitment (Guenzi and Nijssen, 2021). And supportive HR practices signal organizational concerns for its employees and these signals elicit attitudinal and, presumably, behavioral responses, such as increased commitment, continued service to the organization, and a lower intent to quit which results in lowered actual turnover (Seibert et al., 2011). However, since continuous commitment is related to the leaving cost of employees, it was suggested that the relationship between psychological empowerment and continuous commitment would be low.

Psychological empowerment, job embeddedness, and organizational commitment

Avolio et al. (2004) examined psychological empowerment as an antecedent of organizational commitment and as a mediator between transformational leadership and commitment. That study found a positive direct relationship between psychological empowerment and organizational commitment and a significant indirect effect of psychological empowerment. Other studies reported psychological empowerment as a significant antecedent of organizational commitment (Joo and Shim, 2010; Ouyang et al., 2015). Bani et al. (2014) studied the association between psychological empowerment (in terms of sense of efficacy, meaningfulness, autonomy, and trust) and job embeddedness, and they found a positive association between those two constructs. Positive associations between psychological empowerment and job embeddedness were supported from several other studies (Jeon and Yom, 2014; Karavardar, 2014; Bin Jomah, 2017).

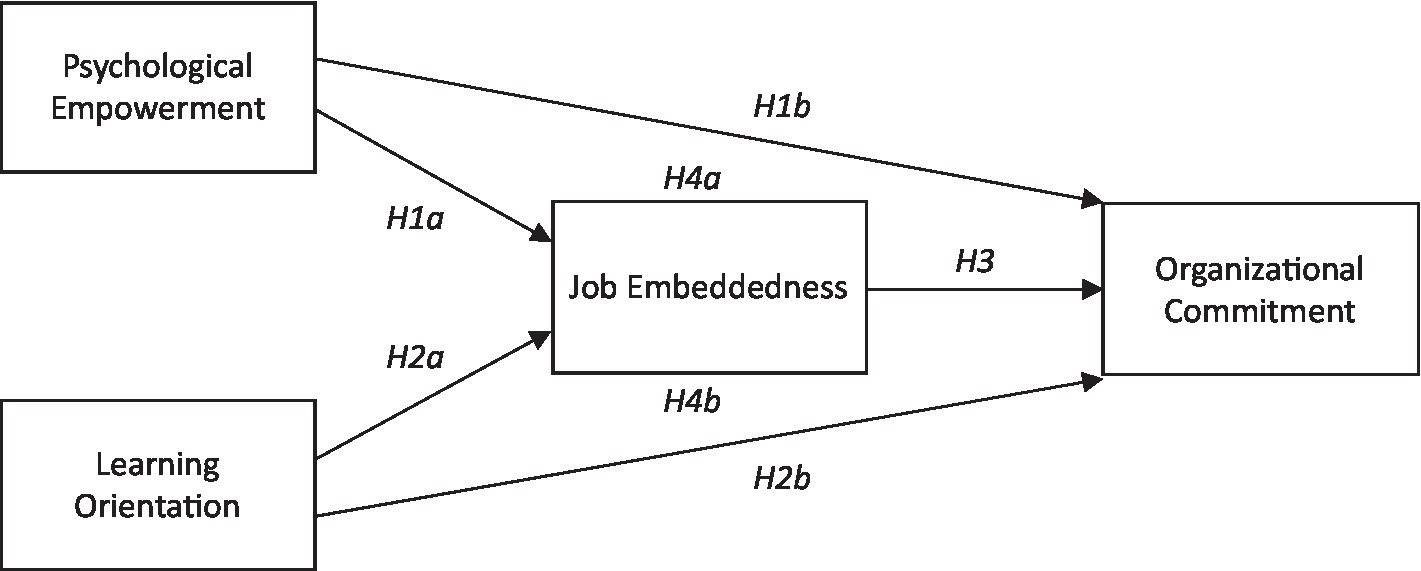

Thomas and Velthouse (1990) suggested that empowerment leads to higher levels of initiative and concentration, which in turn increase organizational commitment. Further, Spreitzer (1995) suggested that empowered employees will regard themselves as more capable of managing their work roles in a more meaningful way by forming a higher level of commitment when empowered (Spreitzer, 1995). Seibert et al. (2011) examined a cross-level model of psychological empowerment. They proposed a model with psychological empowerment as a determinant of individual attitudes, particularly job satisfaction and organizational commitment at the individual level. They reported findings that showed psychological empowerment as positively related to both attitudes. Also, Meyer and Allen (1997) noted the role of psychological empowerment as an intrinsic form of motivation in relation to affective commitment. Therefore, we hypothesize: H1a: Psychological empowerment will be positively related to job embeddedness. H1b: Psychological empowerment will be positively related to organizational commitment.

Learning orientation, job embeddedness, and organizational commitment

Learning orientation attempts to develop employees who are willing to combine their own personal learning with broader collective action in an organization (Senge, 2014). This learning-oriented approach in organizations has facilitated employees’ job adaptation so that they can perform effectively and creatively (Dweck and Leggett, 1988). Previous empirical studies suggest that learning organizations can facilitate desirable outcomes for both individuals and organizations. For example, scholars found that learning organization affected job embeddedness positively (Kanten et al., 2015). Lee et al. (2013) found that the mediating effect of job embeddedness had a significant effect between learning organization and job satisfaction. Also, Joo and Shim (2010) found a positive influence of learning organization culture toward organizational commitment. Hanaysha (2016) also confirmed that organizational learning has a positive impact on organizational commitment. Therefore, we suggest, H2a: Learning orientation will be positively related to job embeddedness. H2b: Learning orientation will be positively related to organizational commitment.

Job embeddedness and organizational commitment

An employee’s organizational commitment is strongly associated with the nature of fit between individuals and their organizations (Mitchell et al., 2001). Several empirical studies stated that a strong level of job embeddedness was associated with effective job performance and low intention to leave (Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2008; Ramesh and Gelfand, 2010). Job embeddedness that used three dimensions (fit, links, and sacrifice), as in this study, predicted not only intent to leave but also other key outcomes, such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Mitchell et al., 2001; Kim and Kang, 2015). Kim and Kang (2015) found that both job embeddedness and organizational commitment were identified as most likely paths to turn-over intentions, and those two variables were positively related. Another study found that the stronger the level of job embeddedness, the more links an individual is likely to have and to be committed to the organization (Nica, 2018). In addition, job embeddedness has a significant effect on improving employee well-being, one of the variables that affects organizational commitment (Ahmad et al., 2022). Thus, the aforementioned literature suggests the following hypothesis: H3: Job embeddedness will be positively related to organizational commitment.

Mediating role of job embeddedness

Retention is a critical concern for many organizations. The most frequent variables used as a predictor for turnover rates are job embeddedness and organizational commitment (Williamson and Holmes, 2015). Regarding job embeddedness, researchers noted that more embedded employees are less likely to voluntarily leave the organization (Mitchell et al., 2001). Several scholars empirically tested the phenomenon by using different variables, such as socialization tactics, organizational support, job embeddedness, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions (Allen and Shanock, 2013). They found that job embeddedness mediated a relationship between socialization tactics (e.g., networking) and job commitment because the more employees feel value in the relationships among employees and belonging, the more they will be satisfied with their work. Frequent social exchange among employees will lead to attitudinal and behavioral commitment by giving a sense of positive relationships (Yoon and Lawler, 2006). Organizations should be proactive about increasing job embeddedness among employees because establishing or increasing job embeddedness is likely to increase retention, attendance, citizenship, and job performance (Mitchell et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004, 2014).

Scholars examined job embeddedness to answer why employees remain in their organizations. Qian et al. (2022) suggest highly embedded in the organization can help employees less vulnerable to job insecurity. Another of the studies investigated the effects of job embeddedness as a moderator of relationships among leader-member exchanges, organization-based self-esteem, organizational citizen behaviors, and task performance (Sekiguchi et al., 2008). That study found that job embeddedness moderated the relationship between self-esteem and organizational citizenship behaviors. As self-esteem and quality of relationship are similar concepts to psychological empowerment, we expected similar patterns of interactions on the relationship as hypothesized below: H4a: Job embeddedness will mediate the relationship between psychological empowerment and organizational commitment. H4b: Job embeddedness will mediate the relationship between learning orientation and organizational commitment.

Materials and methods

Data collection and sample

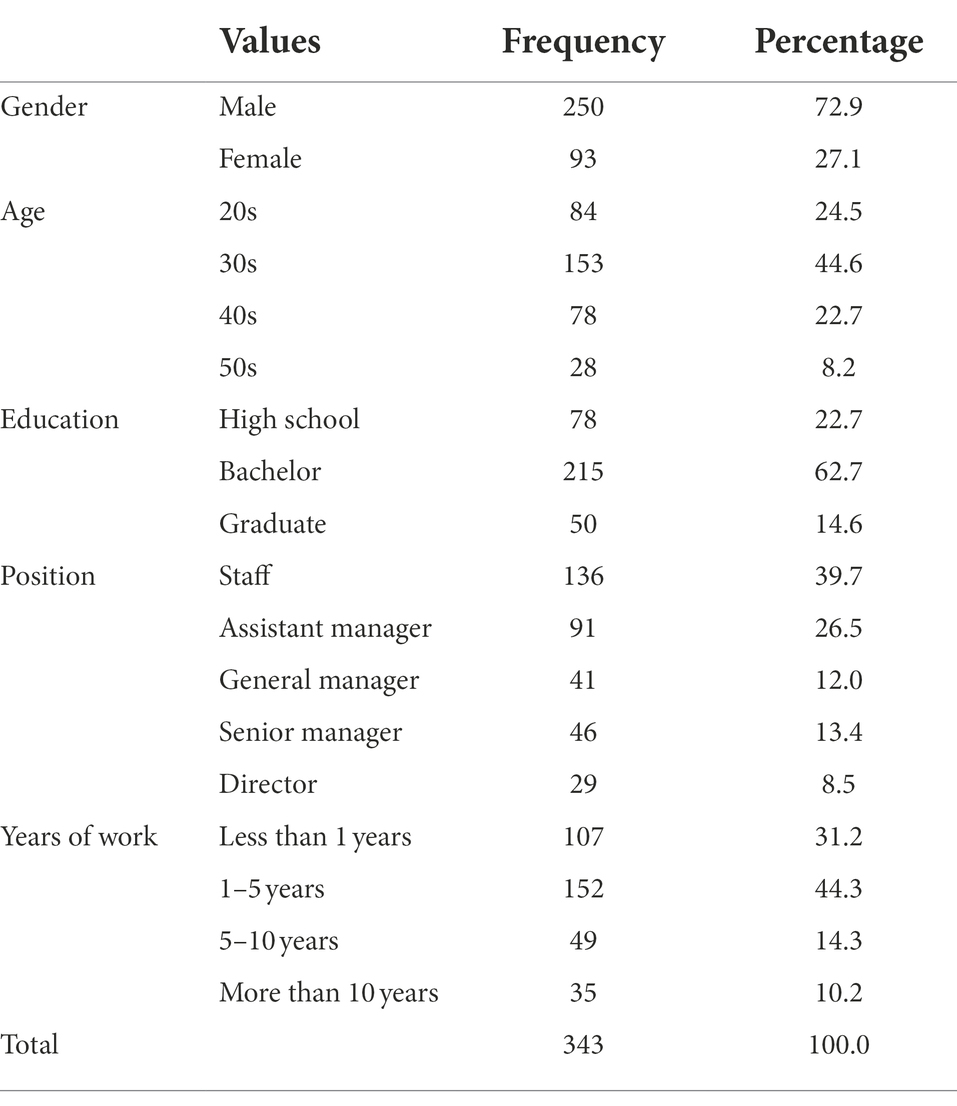

Data were collected from 27 offices of Human Resource Development Service of Korea (governmental agency) located in major cities in South Korea. All 430 employees involved were contacted by HR directors and received a written questionnaire along with a cover letter asking for their confidentiality and voluntary participation in this study. The survey was administrated by randomly assigned identification numbers. A total of 391 employees (91%) completed and returned the survey. Also, 48 sets of missing data were deleted based on list-wise deletion. The sample was 27.1% female and 72.9% male, which shows a very male-dominated organization. Half of the participants (44.6%) were aged in their 30s and 24.5% in their 20s. Over half of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree. There were no significant differences of responses in gender and age (see Table 1).

Measures

This study used four instruments that were previously validated. They were translated using the back-translation procedure and were piloted with HR managers in each office who were not part of this study. A five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) anchored the items.

Psychological empowerment

To measure psychological empowerment, this study used a 12-item scale developed by Spreitzer (1995): competence, impact, meaning and self-determination. In the existing literature, acceptable estimates of reliability have been shown (Dust et al., 2014). In this study, the reliability coefficient was 0.89. An example question is “I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job.” A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assuming the second-order factor indicated good data-model fit (χ2/df = 2.68, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05) with strong item factor loadings, ranging from 0.75 to 0.81.

Learning orientation

To measure learning orientation, an 11-item scale developed by Sinkula et al. (1997) was used. This scale consists of three sub-constructs: an organization’s commitment to learning, shared vision, and open-mindedness. In this study, internal consistency for this measure (Cronbach’s alpha) ranged from 0.88 to 0.90. An example question is “The basic values of this business unit include learning as key to improvement.” CFA suggested that the second-order factor model fit the data well (χ2/df = 3.69, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA =0.06) with all items loading significantly on their corresponding factors (loadings range = 0.78 to.89).

Job embeddedness

Job embeddedness was assessed with a 7-item scale of global job embeddedness (Crossley et al., 2007) that was revised from composite job embeddedness developed by Mitchell et al. (2001). In previous studies, internal consistency for this measure (Cronbach’s alpha) ranged from 0.83 to 0.86 (Mitchell et al., 2001). Reliability scores in this study ranged from 0.88 to 0.90. An example question is “I feel attached to this organization.” CFA indicated reasonable data fit for the three-factor model (χ2/df = 1.27, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA =0.05), ranging factor loadings of.78 to.85.

Affective organizational commitment

To measure affective organizational commitment, a 6-item scale developed by Meyer and Allen (1997) was used. This study’s reliability coefficient was 0.82. An example question is “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.”

Control variable

The questions on demographic data consisted of a nominal scale, with male set at 1 female at 2, age in 20s at 1, 30s at 2, 40s at 3, 50s or older at 4. The educational background was set to high school graduates, bachelor, and graduate. The position was set to staff 1, assistant manage 2, general manager 3, director 4.

Analytical approach

To examine the causal relationships among variables, this study employed structural equation modeling (SEM), which is quantitative research technique accounting for measurement errors (Kline, 2015). Two steps of data analyses were employed: (1) general assumption assessment including data distribution, reliability testing for measurement items, and validity testing for measurement structures as basic assessments for further data analysis, and (2) examinations of structural modeling on mediation analyses. First, basic assumptions for overall data analyses were tested (Hair et al., 2018). During this stage, according to the nature of research constructs, inter-construct correlation coefficient estimates were examined along with item internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient estimates. In addition, CFA was performed to establish a valid measurement structure based on mode-data fit indices (Kline, 2015). Exploratory factor analysis was not considered, as all research constructs were validated and examined in previous studies across various contexts. Moreover, CFA results supported a sound level of construct validity for the proposed model (Hair et al., 2018). Second, to test hypotheses described in research framework, SEM analysis was performed to assess the direct and indirect effects between exogenous variables and endogenous variables (Kline, 2015). To examine structural equation modeling, we used AMOS 27.0 and SPSS 27.0.

Results

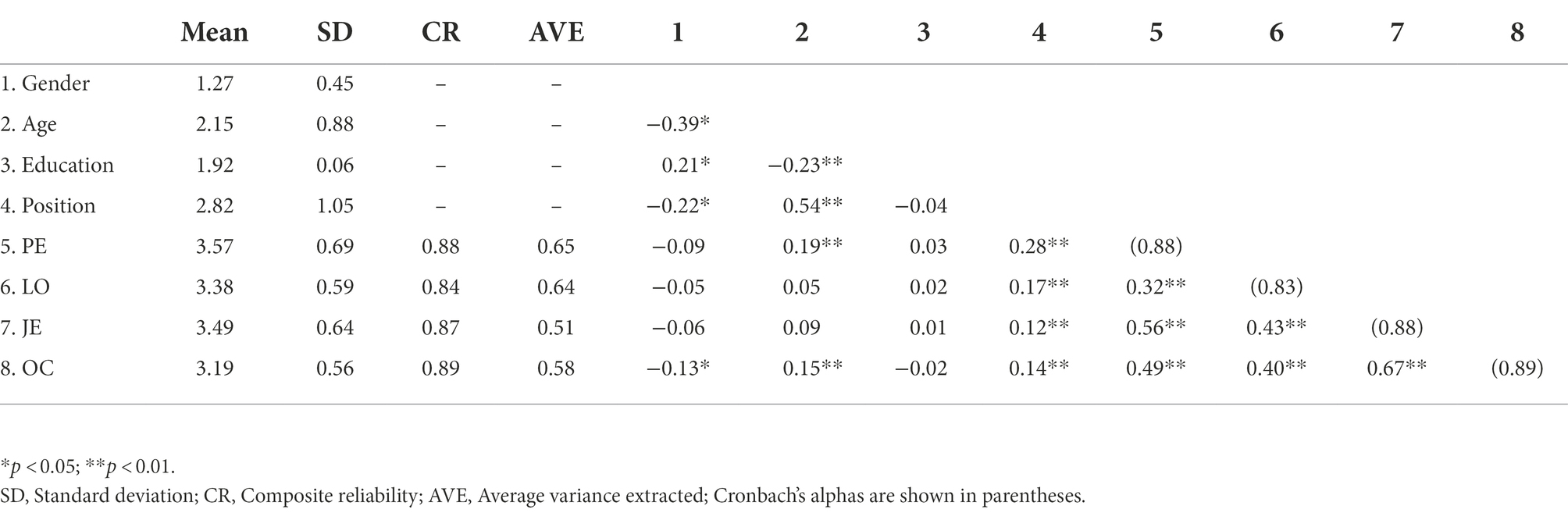

Table 2 summarized results from descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations, and reliability coefficients for each of the study variables. The relationships of four variables are inter-correlated positively and significantly, revealing that multicollinearity is not a concern and that their inter-relationships require further analyses.

Measurement model

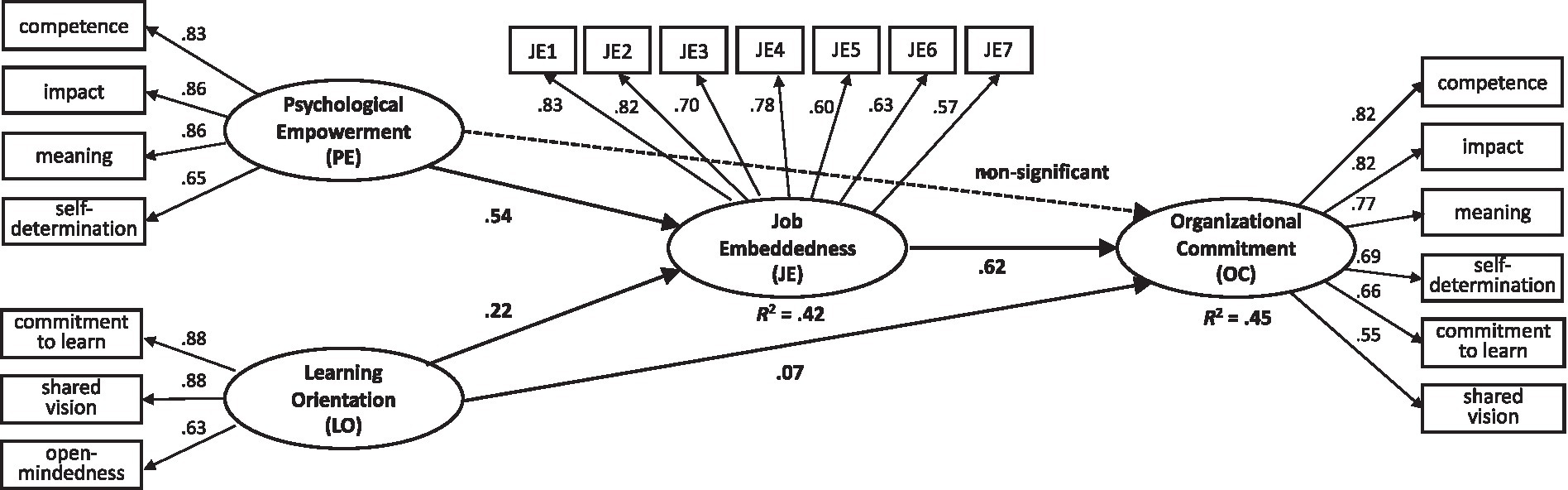

This study employed confirmative factor analysis to examine the stability and validity of the proposed model. Fit statistics of the measurement model are as follows: χ2/df = 1.82, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA =0.04. According to Hair et al. (2018), these fit indices revealed adequate model fit. Also, we examined the phi, correlations among the exogenous variables to further understand the extent to which a construct is truly distinct from other constructs. Results showed that discriminate validity existed among constructs. Convergent validity aims to understand the degree to which measures of the same concept are correlated. According to standardized λ and T values showed in Figure 1, latent variables reached a significant level, which represents the fact that every construct showed convergent validity.

Since this study relied on data assessed via employee self-reports, the possibility of common method bias (CMB) was checked. The Harman single factor test yielded four factors with eigenvalues greater than one that accounted for 72% of the total variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The first factor accounted for 26%, which is well below half of the total variance. Additionally, alternative models were compared. No other models improved the fit, less than.02 in the fit index. Consequently, the proposed model was adopted as the final model.

Hypothesis testing

Figure 2 indicates that psychological empowerment is positively related to job embeddedness (γ = 0.54, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 1a is supported. Consistent with Hypothesis 1a, learning orientation is also positively associated with job embeddedness (γ = 0.22, p < 0.01), thereby supporting Hypothesis 2a. Hypothesis 1b predicted that psychological empowerment is positively related to organizational commitment. However, the path coefficient is not statistically significant (γ = 0.05, p > 0.05). Thereby, Hypothesis 1b is not supported. Psychological empowerment does not have a direct effect on organizational commitment. In contrast, learning orientation is directly associated with organizational commitment. The path coefficient is statistically significant (γ = 0.07, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 2b is supported.

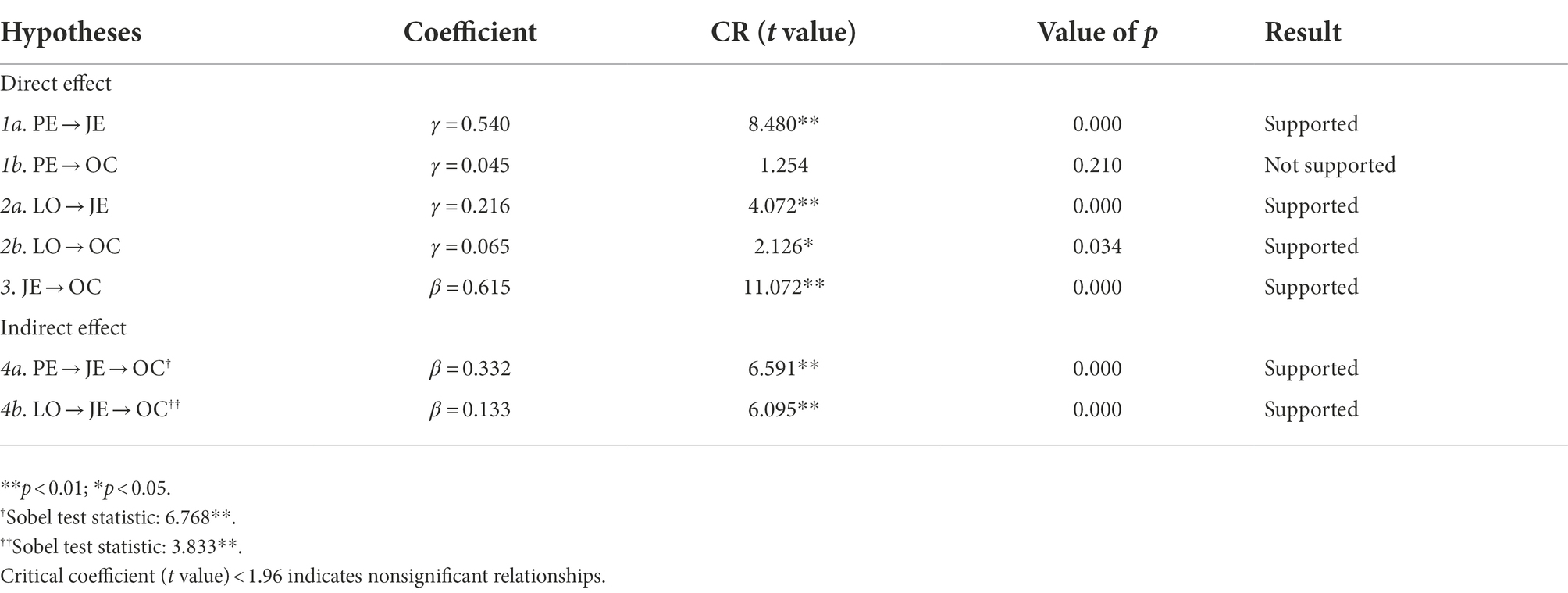

To investigate the mediating effect of job embeddedness, this study examined the direct and indirect effect of structural and competing models. Path coefficients of the structural and competing models are represented in Table 3. The path between empowerment and job embeddedness, and the path between learning orientation and job embeddedness, were significantly related; however, their relationships with commitment were not significant. In addition to significant relationship between job embeddedness and organizational commitment, we observed that job embeddedness indirectly influenced the relationship with organizational commitment. Further, we examined the direct and indirect effects of the structural model. In Table 3, the influences of psychological empowerment on organizational commitment exist only in the indirect relationship. The indirect effect of job embeddedness is approved, and hypotheses 3 and 4 (both a and b) are supported as follows:

Discussion

We investigated the role of job embeddedness on organizational commitment by assuming both a direct and an indirect effect of psychological empowerment and organizational learning orientation. Our results confirmed that all hypothesized relationships (PE and JE, LO and JE, LO and OC, JE and OC, and the mediating role of JE) are supported, except for psychological empowerment and organizational commitment. Aligned with previous literature, psychological empowerment was positively related to job embeddedness, especially considering the importance of psychological recourses on job embeddedness (Harunavamwe et al., 2020). However, psychological empowerment was not significantly related to organizational commitment in our present model. There may be a possible explanation that, depending on organizational culture or countries, the level of psychological empowerment and organizational commitment may be different (Jordan et al., 2017). In addition, Laschinger et al. (2002) suggested that the relationship between psychological empowerment and continuous commitment is low because continuous commitment, one of the organizational commitment variables, is related to the cost of leaving. Likewise, since the subject of the survey was small and medium-sized enterprises, it is analyzed that the relationship between continuous commitment related to leaving costs or external economic conditions may have played a greater role than affective commitment due to psychological empowerment.

Spector (1994) suggested that employees who feel high empowerment show a high degree of commitment to the organization. In addition, studies have been suggested that the higher the autonomy within the organization, the higher the job satisfaction and work efficiency (Seibert et al., 2004). Other studies reported psychological empowerment as a significant antecedent of organizational commitment (Joo and Shim, 2010; Ouyang et al., 2015). Bani et al. (2014) studied the association between psychological empowerment (in terms of sense of efficacy, meaningfulness, autonomy, and trust) and job embeddedness, and they found a positive association between those two constructs. Positive associations between psychological empowerment and job embeddedness were supported from several other studies (Jeon and Yom, 2014; Karavardar, 2014; Bin Jomah, 2017). In this study, while the impact of psychological empowerment was not significantly related to organizational commitment, it is notable that through job embeddedness, psychological empowerment had indirect effects on organizational commitment.

Further, learning orientation had significant effects on job embeddedness and organizational commitment. Findings of this study emphasize the role of learning organizations because learning orientation can support the ideas of employees’ psychological empowerment, organizational commitment, and job embeddedness (Islam et al., 2016). Learning organizations focus on adapting and generating new ideas with the belief that employees can continually learn how to work together and increase their capacity to create the results (Garvin et al., 2008). Aligned with the previous literature, learning organizations can act to be proactive rather than simply reactive to circumstances (Senge, 2006). This is accomplished by incorporating inputs from all levels of employees rather than receiving comments only from top management. This study can be useful for future researchers because not many researchers have used learning orientation as a predictor of job embeddedness, even if factors related to organizational culture were stressed in previous studies (Shah et al., 2020).

Findings from this study extend empirical literature on the positive effect of job embeddedness on organizational outcomes. The positive impact of job embeddedness has been examined numerously starting with reduced turnover (e.g., Lee et al., 2004; Shah et al., 2020), and expanded into other outcomes including job satisfaction and job performance (e.g., Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2008; Sun T. et al., 2012). These studies sequaciously supported job embeddedness as a significant mediator between individual characteristics or work context and individual’s psychological attachment. Although job embeddedness has been reported as a significant moderator between leadership and job performance (Sekiguchi et al., 2008), more scholars adopted the concept as an indicator of work efforts and energy that lead to positive organizational outcomes (Wheeler et al., 2012). Result of the significant indirect effect of job embeddedness mediating the relationship of psychological empowerment and learning orientation toward organizational commitment should prove to be a strong contribution to the growing body of knowledge and interests in employees’ affect toward their organization.

Lastly, the most compelling finding is a full mediation of job embeddedness in the relationship between psychological empowerment and organization commitment. That is, this result points to a potential job embeddedness-based mediator that adds to the organizational behavior mechanisms explored in past research. It shows that the job embeddedness only partially mediated learning orientation relationships; completely mediated the relationship in psychological empowerment and organizational commitment. Even if the direct effect of psychological empowerment on organizational commitment was not significant, we found that the indirect effect through job embeddedness was significant (Sobel test statistic: 6.768, p < 0.01). This finding indicates that employees’ job embeddedness plays a critical mediating role for employees to become more committed to work under conditions where employees are psychologically empowered and to work under a learning organization culture, which has not been examined in previous studies. Without job embeddedness of employees, even if employees are psychologically empowered or are exposed to a learning culture, employees may not commit themselves to organizational activities. This finding highlights ongoing interactional networks of social relations in critical awareness and problem-solving, and how well the work environment suits employees. People guide their commitment based on social interactions with peers and continue to deal with those they trust (Chan et al., 2008).

Implications for practice and research

Our study has several implications for practice and research. The presented structural model may be adopted as a reference tool for practitioners when addressing improvements for the awareness of organizational jobs and commitment. First, this study suggests that programs targeted toward enhancing organizational commitment may focus on the concept of job embeddedness and include psychological empowerment and learning orientation as focal points. Ultimately, job embeddedness is a psychometrically sound construct that captures employees’ work energy and efforts that help them to understand meaning, importance, and sustainment relative to their job. Effectiveness and promise of employee assistance programs’ improving employees’ job embeddedness related to lowering turnover has been well documented in the literature (Wheeler et al., 2007). Investments in empowerment training is often questioned and compared against a single outcome, such as employee’s commitment and well-being. When their effect on what job embeddedness is accounted for, leaders and managers will better understand the role and efficacy of employee empowerment that may instill greater attachment to working groups, encourage their motivation, and lead to greater commitment (Sun L. Y. et al., 2012).

Also, scholars can build upon our model to further expand research on the subject. Researchers can re-examine this suggested structural equation model by replacing the existing variables with other cognate variables. For example, Dweck et al. (2014) included a growth mindset variable instead of learning orientation, which we adopted to capture the employee’s motivational state as a response to the organization. Future researchers can also seek other environmental factors that help to create a learning organization. Other factors, such as organizational climate, managerial support, and a psychologically safe environment can be further included in the structural model as exogenous or indirect effects to continuously update and expand the body of relevant research.

Particularly, scholars can add the shared vision of an organization and its acceptance to the organizational members into the model, given the rising interest of the match between organizational values and important outcomes of society and customers. A shared vision among employees helps to provide focus for the organization as a whole, allowing for momentum and drive towards a vision through job embeddedness. This vision is different from an individual vision in that it is more important for the whole to possess and understand the vision than it is for any individual; it is something that binds individuals together (Senge, 2006).

Limitations and future research suggestions

Some limitations need to be recognized. First, the generalizability of the results should consider the sampling. Although data were collected from multiple industries, participants were those who attended Human Resource Development training in South Korea. We need to examine if the sample of employees without training has similar patterns or not. In addition, studies conducted across different nations and continents tend to enrich the validation of a proposed model. Second, this study focused on the effects of each variable based on one-time data collection. Exploring the effects of the model based on time gaps, especially considering the time needed to transfer employee assistance interventions will be particularly helpful. Relatively few studies have used longitudinal data to study job embeddedness (Gallie et al., 2017).

Third, a self-reported instrument was used, which may be subject to respondent biases, such as the inability to provide accurate responses because of insufficient recall or memory. Also, a CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2003) is a greater challenge in a cross-sectional study. Although various measures were applied, such as single factor and alternative models testing, as well as an examination of convergent and divergent validity, other useful techniques, such as a marker variable testing, exist. As with all other times when using the same Likert-type scale, the variance that the scales shared with each other represent a response bias. There may be central tendency bias and social desirability bias, which are common for any Likert-type scale.

In conclusion, results of this study suggest that employee’s on-and off-the job causes of turnover may enrich knowledge of commitment, increasing it beyond the current focus on employee’s retention. Psychological empowerment and learning orientation were significantly predictive of organizational commitment through job embeddedness. This broader impact of job embeddedness extends theory and suggests compelling directions for future study

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DY and CH contributed to conception and design of the study. SL and MS organized the database and performed the statistical analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JC and SH wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

We would like to thank that this paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2019.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, A., Shah, F. A., Memon, M. A., Kakakhel, S. J., and Mirza, M. Z. (2022). Mediating effect of job embeddedness between relational coordination and employees’ well-being: A reflective-formative approach. Curr. Psychol. 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03637-3

Allen, D. G., and Shanock, L. R. (2013). Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. J. Organ. Behav. 34, 350–369. doi: 10.1002/job.1805

Avolio, B. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., and Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 25, 951–968.

Baker, W. E., and Sinkula, J. M. (1999). The synergistic effect of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 27, 411–427. doi: 10.1177/0092070399274002

Bani, M., Yasoureini, M., and Mesgarpour, A. (2014). A study on relationship between employees’ psychological empowerment and organizational commitment. Manag. Sci. Lett. 4, 1197–1200. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2014.5.007

Barroso Castro, C., Villegas Perinan, M. M., and Casillas Bueno, J. C. (2008). Transformational leadership and followers' attitudes: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 19, 1842–1863. doi: 10.1080/09585190802324601

Bin Jomah, N. (2017). Psychological empowerment on organizational commitment as perceived by Saudi academics. World J. Educ. 7, 83–92. doi: 10.5430/wje.v7n1p83

Bunderson, J. S., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2003). Management team learning orientation and business unit performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 552–560. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.552

Calantone, R. J., Cavusgil, S. T., and Zhao, Y. (2002). Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 31, 515–524. doi: 10.1016/S0019-8501(01)00203-6

Chan, Y. H., Taylor, R. R., and Markham, S. (2008). The role of subordinates' trust in a social exchange driven psychological empowerment process. J. Manag. Issues 20, 444–467.

Conger, J. A., and Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 13, 471–482. doi: 10.2307/258093

Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., and Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 92:1031. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1031

Dust, S. B., Resick, C. J., and Mawritz, M. B. (2014). Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic–organic contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 413–433. doi: 10.1002/job.1904

Dweck, C. S., and Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95:256. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck, C. S., Murphy, M., Chatman, J., Kray, L., and Delaney, S. (2014). Why Fostering a Growth Mindset in Organizations Matters. Huntington Beach, CA: Senn Delaney,

Felps, W., Mitchell, T. R., Hekman, D. R., Lee, T. W., Holtom, B. C., and Harman, W. S. (2009). Turnover contagion: how coworkers' job embeddedness and job search behaviors influence quitting. Acad. Manag. J. 52, 545–561. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.41331075

Gallie, D., Zhou, Y., Felstead, A., Green, F., and Henseke, G. (2017). The implications of direct participation for organisational commitment, job satisfaction and affective psychological well-being: a longitudinal analysis. Ind. Relat. J. 48, 174–191. doi: 10.1111/irj.12174

Garvin, D. A., Edmondson, A. C., and Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning organization? Harv. Bus. Rev. 86, 109–116.

Ghosh, D., and Gurunathan, L. (2015). Job embeddedness: a ten-year literature review and proposed guidelines. Glob. Bus. Rev. 16, 856–866. doi: 10.1177/0972150915591652

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., and Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 26, 463–488. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00043-X

Guenzi, P., and Nijssen, E. J. (2021). The impact of digital transformation on salespeople: An empirical investigation using the JD-R model. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 41, 130–149. doi: 10.1080/08853134.2021.1918005

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., and Tatham, R. L. (2018). Multivariate Data Analysis (8th Edn.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Press.

Halbesleben, J. R., and Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress 22, 242–256. doi: 10.1080/02678370802383962

Hanaysha, J. (2016). Testing the effects of employee engagement, work environment, and organizational learning on organizational commitment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 229, 289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.139

Harley, B., Allen, B. C., and Sargent, L. D. (2007). High performance work systems and employee experience of work in the service sector: the case of aged care. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 45, 607–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8543.2007.00630.x

Harunavamwe, M., Nel, P., and Van Zyl, E. (2020). The influence of self-leadership strategies, psychological resources, and job embeddedness on work engagement in the banking industry. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 50, 507–519. doi: 10.1177/0081246320922465

Hofstede, G. (1998). Attitudes, values and organizational culture: Disentangling the concepts. Organ. Stud. 19, 477–493.

Holtom, B. C., and O’neill, B. S., (2004). Job embeddedness: a theoretical foundation for developing a comprehensive nurse retention plan. J. Nurs. Adm. 34, 216–227. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200405000-00005

Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., and Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: a meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1332–1356.

Islam, T., Khan, M. M., and Bukhari, F. H. (2016). The role of organizational learning culture and psychological empowerment in reducing turnover intention and enhancing citizenship behavior. Learn. Organ. 23, 156–169. doi: 10.1108/TLO-10-2015-0057

Jeon, J. H., and Yom, Y. H. (2014). Roles of empowerment and emotional intelligence in the relationship between job embeddedness and turnover intension among general hospital nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 20, 302–312. doi: 10.11111/jkana.2014.20.3.302

Joo, B. K., and Shim, J. H. (2010). Psychological empowerment and organizational commitment: the moderating effect of organizational learning culture. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 13, 425–441. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2010.501963

Jordan, G., Miglilč, G., Todorović, I., and Marič, M. (2017). Psychological empowerment, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among lecturers in higher education: comparison of six CEE countries. Organizacija 50, 17–32. doi: 10.1515/orga-2017-0004

Kanten, P., Kanten, S., and Gurlek, M. (2015). The effects of organizational structures and learning organization on job embeddedness and individual adaptive performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 23, 1358–1366. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00523-7

Karavardar, G. (2014). Perceived organizational support, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behavior, job performance and job embeddedness: a research on the fast food industry in Istanbul, Turkey. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 9:131. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v9n4p131

Karim, N. H. A. (2017). The impact of work related variables on librarians’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 15, 149–163.

Kiazad, K., Holtom, B. C., Hom, P. W., and Newman, A. (2015). Job embeddedness: a multifoci theoretical extension. J. Appl. Psychol. 100:641. doi: 10.1037/a0038919

Kim, K. Y., Eisenberger, R., and Baik, K. (2016). Perceived organizational support and affective organizational commitment: moderating influence of perceived organizational competence. J. Organ. Behav. 37, 558–583. doi: 10.1002/job.2081

Kim, Y., and Kang, Y. (2015). Effects of self-efficacy, career plateau, job embeddedness, and organizational commitment on the turnover intention of nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 21, 530–541. doi: 10.11111/jkana.2015.21.5.530

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Kontoghiorghes, C. (2016). Linking high performance organizational culture and talent management: satisfaction/motivation and organizational commitment as mediators. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 27, 1833–1853. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2015.1075572

Laschinger, H. K. S., Finegan, J., and Shamian, J. (2002). “The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’ work satisfaction and organizational commitment,” in Advances in health care management (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 3, 59–85.

Lee, T. W., Burch, T. C., and Mitchell, T. R. (2014). The story of why we stay: a review of job embeddedness. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 1, 199–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091244

Lee, S. K., Choi, D. G., Kang, E. G., and Lee, S. W. (2013). A study on the influence of dimensions of learning organization to job satisfaction: mediating effect of job embeddedness. J. Digit. Convergence 11, 185–192. doi: 10.14400/JDPM.2013.11.12.185

Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Sablynski, C. J., Burton, J. P., and Holtom, B. C. (2004). The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 47, 711–722. doi: 10.5465/20159613

Li, J. J., Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Hom, P. W., and Griffeth, R. W. (2016). The effects of proximal withdrawal states on job attitudes, job searching, intent to leave, and employee turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 1436–1457. doi: 10.1037/apl0000147

Mathieu, C., Fabi, B., Lacoursière, R., and Raymond, L. (2016). The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. J. Manag. Organ. 22, 113–129. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2015.25

Matsuo, M. (2022). Influences of developmental job experience and learning goal orientation on employee creativity: mediating role of psychological empowerment. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 25, 4–18. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2020.1824449

Maynard, M. T., Luciano, M. M., D’Innocenzo, L., Mathieu, J. E., and Dean, M. D. (2014). Modeling time-lagged reciprocal psychological empowerment–performance relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 99, 1244–1253. doi: 10.1037/a0037623

Meyer, J. P., and Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., and Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 44, 1102–1121. doi: 10.5465/3069391

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., and Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism and turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Nica, E. (2018). The role of job embededness in influencing employees’ organizational commitment and retention attitudes and behaviors. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 13, 101–106.

Ouyang, Y. Q., Zhou, W. B., and Qu, H. (2015). The impact of psychological empowerment and organisational commitment on Chinese nurses’ job satisfaction. Contemp. Nurse 50, 80–91. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2015.1010253

Podsakoff, P. M., Mac Kenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88:879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Qian, S., Yuan, Q., Niu, W., and Liu, Z. (2022). Is job insecurity always bad? The moderating role of job embeddedness in the relationship between job insecurity and job performance. J. Manag. Organ. 28, 956–972. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2018.77

Ramesh, A., and Gelfand, M. J. (2010). Will they stay or will they go? The role of job embeddedness in predicting turnover in individualistic and collectivistic cultures. J. Appl. Psychol. 95:807. doi: 10.1037/a0019464

Seibert, S. E., Silver, S. R., and Randolph, W. A. (2004). Taking empowerment to the next level: a multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 47, 332–349. doi: 10.5465/20159585

Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., and Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: a meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 981–1003. doi: 10.1037/a0022676

Sekiguchi, T., Burton, J. P., and Sablynski, C. J. (2008). The role of job embeddedness on employee performance: the interactive effects with leader–member exchange and organization-based self-esteem. Pers. Psychol. 61, 761–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00130.x

Sender, A., Rutishauser, L., and Staffelbach, B. (2018). Embeddedness across contexts: a two-country study on the additive and buffering effects of job embeddedness on employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 28, 340–356. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12183

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization (2nd Ed.). New York, NY: Currency Doubleday.

Senge, P. M. (2014). The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Shah, I. A., Csordas, T., Akram, U., Yadav, A., and Rasool, H. (2020). Multifaceted role of job embeddedness within organizations: development of sustainable approach to reducing turnover intention. SAGE Open 10, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/2158244020934876

Sinkula, J. M., Baker, W. E., and Noordewier, T. (1997). A framework for market-based organizational learning: linking values, knowledge, and behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 25, 305–318. doi: 10.1177/0092070397254003

Spector, P. E. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: a comment on the use of a controversial method. J. Organ. Behav. 15, 385–392. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150503

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 1442–1465. doi: 10.5465/256865

Spreitzer, G. M., Kizilos, M. A., and Nason, S. W. (1997). A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness, satisfaction, and strain. J. Manag. 23, 679–704.

Sun, L. Y., Zhang, Z., Qi, J., and Chen, Z. X. (2012). Empowerment and creativity: a cross-level investigation. Leadersh. Q. 23, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.005

Sun, T., Zhao, X. W., Yang, L. B., and Fan, L. H. (2012). The impact of psychological capital on job embeddedness and job performance among nurses: a structural equation approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 68, 69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05715.x

Thomas, K. W., and Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 15, 666–681. doi: 10.5465/amr.1990.4310926

Watkins, K. E., and Marsick, V. J. (1993). Sculpting the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and Science of Systemic Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Watkins, K. E., and Marsick, V. J. (2019). “Conceptualizing an organization that learns,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Learning Organization. ed. A. Ortenblad (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 51–66.

Wheeler, A. R., Coleman Gallagher, V., Brouer, R. L., and Sablynski, C. J. (2007). When person-organization (mis) fit and (dis) satisfaction lead to turnover: the moderating role of perceived job mobility. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 203–219. doi: 10.1108/02683940710726447

Wheeler, A. R., Harris, K. J., and Sablynski, C. J. (2012). How do employees invest abundant resources? The mediating role of work effort in the job-embeddedness/job-performance relationship. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, E244–E266. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01023.x

Williamson, I. O., and Holmes, O. IV (2015). What's culture got to do with it? Examining job embeddedness and organizational commitment and turnover intentions in South Africa. Afr. J. Manag. 1, 225–243. doi: 10.1080/23322373.2015.1056649

Yoon, J., and Lawler, E. (2006). “Relational cohesion model of organizational commitment,” in Relational Perspectives in Organizational Studies. eds. O. Kyriakidou and M. Ozbilgin (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar), 38–162.

Keywords: job embeddedness, psychological empowerment, learning orientation, organizational commitment, mediating role

Citation: Yoon D-Y, Han CS-H, Lee S-K, Cho J, Sung M and Han SJ (2022) The critical role of job embeddedness: The impact of psychological empowerment and learning orientation on organizational commitment. Front. Psychol. 13:1014186. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1014186

Edited by:

Jalal Hanaysha, Skyline University College, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Zhong Wang, City University of Macau, Macao SAR, ChinaWeijing Chen, Hubei University, China

Copyright © 2022 Yoon, Han, Lee, Cho, Sung and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Caleb Seung-Hyun Han, Y2FsZWJoYW5AdWdhLmVkdQ==

Dong-Yeol Yoon

Dong-Yeol Yoon Caleb Seung-Hyun Han

Caleb Seung-Hyun Han Soo-Kyoung Lee

Soo-Kyoung Lee Jun Cho

Jun Cho Moonju Sung5

Moonju Sung5