- 1Department of Global Health Promotion, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Research Fellow of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan

Introduction: Few studies have investigated the moderating effect of coping skills on the association between bullying experience and low self-esteem. The aim of this study was to examine whether coping skills have a moderating effect on the association between bullying experience and self-esteem among Japanese students.

Methods: Data from the population-based Kochi Child Health Impact of Living Difficulty (K-CHILD) study conducted in 2016 were analyzed. Participants included fifth-and eighth-grade students living in Kochi Prefecture, Japan. A questionnaire for the students (n = 5,991) assessed the bullying experience, self-esteem (the Japanese Edition of the Harter’s Perceived Competence Scale for Children), and coping skills that comprised six types (The shortened version of coping skills for elementary school children). Multivariate linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between bullying experience and self-esteem and then the moderating effects of six types of coping as interaction terms on the association were considered.

Results: Bullying experience was inversely associated with self-esteem. All six types of coping did not moderate the relationship between bullying experience and low self-esteem even after adjusting for cofounders (all P for interaction > 0.15).

Conclusion: Coping skills did not moderate the association between bullying experience and self-esteem, suggesting that intervention to boost coping skills to mitigate the adverse effect of bullying experience may not be promising.

Introduction

Bullying is a notable social problem at school and the workplace globally. The 2018 Program for International Student Assessment reported that 23% of students reported being bullied at least a few times a month on average across OECD countries. Although the definition of bullying may vary by research, bullying generally involves (1) intentionality, (2) repetition, and (3) a clear power imbalance between perpetrator and victim (Olweus, 1993). Regardless of the varied components of bullying, the outcome of bullying for victims is often the deterioration of mental health, such as depression, anxiety, or suicidality (Azúa Fuentes et al., 2020). The global school-based Student Health Survey conducted in Asia, Africa, and South America (2009–2017) showed that children who had bullying victimization were 2.8 times more likely to attempt suicide (Smith et al., 2021). In Japan, similarly, a study that investigated the risk factors for suicidality reported that school bullying had a high odds ratio (OR) in junior high students (OR: 3.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.1–4.4) and high school students (OR: 3.6, 95% CI: 2.5–5.3) (Nagamitsu et al., 2020).

Low self-esteem induced by bullying (van Geel et al., 2018) is the main cause of serious mental illnesses in victims. A previous study found that self-esteem mediated the association between bullying victimization and depression (Zhong et al., 2021). Furthermore, low self-esteem in childhood and early adolescence had an influence on depression, anxiety, and internalizing disorders in later adolescence and adulthood (Sowislo and Orth, 2013; Keane and Loades, 2017). Moreover, students who reported having low self-esteem were more likely to declare poorer self-rated health afterward (Arsandaux et al., 2019). Eventually, low self-esteem was closely related to suicidality (Overholser et al., 1995; McGee et al., 2001; Manani and Sharma, 2016).

Several studies have discussed the effect modifiers that can attenuate the association between bullying experience and low self-esteem, such as social support, friendship, and characteristics of victims like mindfulness and forgiveness (Zhou et al., 2017; Barcaccia et al., 2018). Among them, specific coping ways can be a possible moderator of the association between being bullied and low self-esteem. In general, the coping style includes emotion-focused coping which aims to manage emotions associated with the stressor and problem-focused coping which aims to tackle the problems (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980). Among children and adolescents, problem-focused coping is positively associated with self-esteem (Cong et al., 2021). Another study that assessed workplace bullying showed that victims who chose to seek help or assertiveness as a coping style (i.e., problem-focused coping) were more likely to keep high self-esteem scores in comparison with victims who chose other coping styles, while avoidance of coping style (i.e., emotion-focused coping) deteriorated the influence of being bullied on self-esteem (Bernstein and Trimm, 2016). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study investigates the moderating effect of the association between bullying experience and self-esteem among school children.

In a study that compared college students in Japan and those in the United States, it was revealed that the prevalence of students who had engaged in bullying as perpetrators was significantly higher in Japan than in the United States (17.8 vs. 11.7%) (Kobayashi and Farrington, 2020). In addition, as Japanese tend to have lower self-esteem and are more self-critical than their Western counterparts (Heine et al., 1999; Heine and Hamamura, 2007), Japan is a suitable setting to assess the modifiable factors that mitigate the association between bullying experience and low self-esteem.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether bullying experience affects self-esteem and whether coping skills have a moderation effect on the association or not. This study hypothesized that (1) bullying experience is associated with low self-esteem and (2) coping skills moderate the association between bullying experience and low self-esteem.

Materials and methods

Participants

We analyzed data from the Kochi Child Health Impact of Living Difficulty (K-CHILD) study conducted in 2016 (Doi et al., 2020). TF designed the K-CHILD study in consultation with Kochi Prefecture. The objective of this study was to assess the living and health conditions of elementary school, junior high school, and high school students and their parents in Kochi Prefecture, Japan. Kochi Prefecture has a population of 690,211 and 317,822 households as of September 2020. In Kochi, 2.55% of households receive public assistance as of August 2021, and the rate is the fourth highest of 47 Prefectures in Japan. Kochi Prefecture has bolstered its policies to improve the physical and mental health of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds.

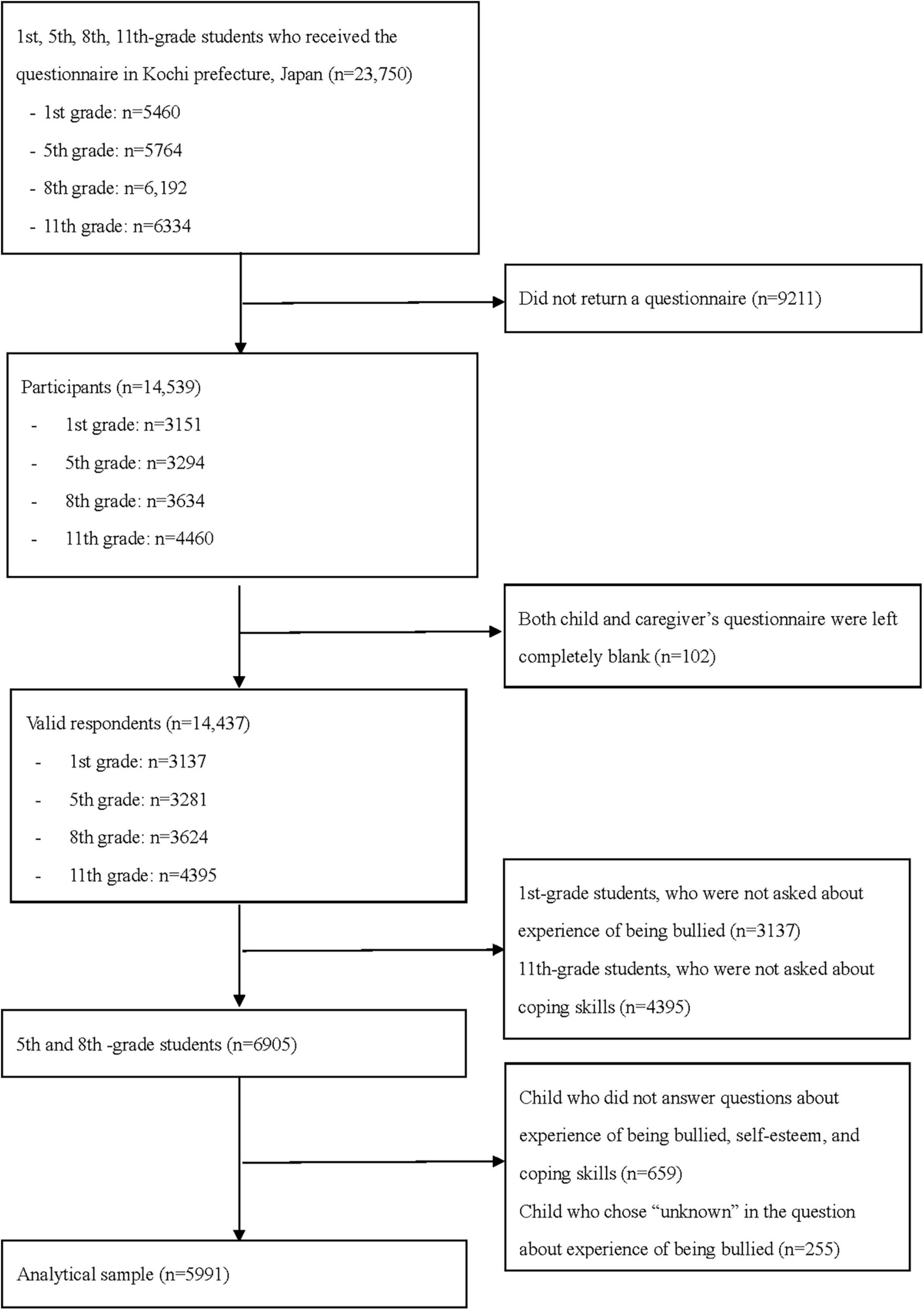

The participants of the K-CHILD study were students in the first and fifth grades in all elementary schools, students in the eighth grade in all junior high schools, and students in the eleventh grade in all high schools. K-CHILD targeted all public, private, and special needs schools in the prefecture, except for correspondence high schools and one special needs school. The Office of Children and Family Services in Kochi Prefecture mailed questionnaires to each school. The anonymous and self-answered questionnaires for children and their caregivers were distributed to children by their teachers. The caregivers’ version of the questionnaires was brought home to the caregivers by their children. The total number of children who received the questionnaires was 23,750, of which 5,460 were in the first grade, 5,764 in the fifth grade, 6,192 in the eighth grade, and 6,334 in the eleventh grade. A total of 14,539 completed children’s and caregivers’ questionnaires were returned to the Office of Children and Family Services in Kochi City (the biggest city in the prefecture) by mail anonymously or to the schools in-person in anonymous envelopes (overall response rate: 61.2%). Approximately 9,108 questionnaires were distributed to participants, and 3,517 of them were returned by postal mail, so the response rate was 38.6%; 14,642 questionnaires were distributed to participants, and 11,022 of them were returned to the schools in person, so the response rate was 75.3%. Notably, 102 child–caregiver pairs returned questionnaires that were blank. Hence, the sum of valid responses was 14,437.

In our study, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the 1st-grade students because they were not asked about bullying experience; (2) the 11th-grade students because they were not asked about coping skills; (3) children who did not answer questions about bullying experience, self-esteem, and coping skills; and (4) children who chose “unknown” in the question about bullying experience. We excluded from our analysis the first-grade students who were not asked about bullying experience (n = 3,137) and the eleventh-grade students who were not asked about their coping skills (n = 4,395). Furthermore, we excluded the respondents who did not answer any of our main variables, such as bullying experience, self-esteem, or coping skills, and respondents who answered unknown in the questionnaire on bullying experience. Finally, our analytical sample consisted of 5,991 pairs in the fifth (n = 2,906) and eighth grades (n = 3,085) (Figure 1).

Measurements

Bullying experience

The question “Have you ever been bullied?” was asked, and the answer could be 1 (often), 2 (sometimes), 3 (occasionally), 4 (never), or 5 (unknown). In our study, we used the respondents of 1–4 as a continuous variable, and 5 was categorized as missing because it was not an ordinal variable. To avoid the burden of responding to being bullied experience, we did not assess the types of bullying experiences.

Coping skills

Children’s coping skills were calculated by using 12 items on a scale of the shortened version of coping skills for Japanese elementary school children (Otake et al., 2001). They were asked about the frequency of their way of coping when they were confronted by troubles. The 12 means of coping are as follows: (1) asking someone how to cope with troubles, (2) asking for help, (3) trying to change oneself, (4) trying to realize the causes of troubles, (5) being alone, (6) crying alone, (7) yelling in a loud voice, (8) complaining to someone, (9) quitting to think deeply, (10) giving up doing anything, (11) playing games, and (12) playing with friends. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.579. Children rated these items as 1 (rarely), 2 (occasionally), 3 (sometimes), and 4 (often) and then six scores of coping styles were calculated by adding two corresponding questions out of (1) to (12): (a) asking for help as a coping type was calculated by adding two scores of (1) and (2), (b) solving problem was from (3) to (4), (c) emotional avoidance was from (5) to (6), (d) behavioral avoidance was from (7) to (8), (e) cognitive avoidance was from (9) to (10), and (f) diversion was from (11) to (12). Based on previous studies (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980; Machmutow et al., 2012), problem-focused coping includes (a) asking for help and (b) solving problems, while emotion-focused (avoidance) coping includes (c) emotional avoidance, (d) behavioral avoidance, (e) cognitive avoidance, and (f) diversion. When one of the two corresponding questions decided a coping style was missing, we used another score for imputation. When both two corresponding questions were not answered, we dealt with the sample as missing.

Self-esteem

Children’s self-esteem was estimated using the subscale of the self-esteem of the Japanese Edition of Harter’s Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Sakurai, 1992). It consists of nine items: “Are you confident in yourself?,” “Do you think you can manage most things better than anyone else?,” “Do you think you have many values that you are proud of?,” “Do you feel you would succeed if you tried anything?,” “Are you satisfied with what you are now?,” “Do you think you can become a great person?,” “Do you think you have many values for society?,” “Are you able to express your opinion with confidence?,” and “Do you think you have many good points?.” The children answered each item with a scale of 0 (no), 1 (rather no), 2 (rather yes), and 3 (yes). A higher total score means a higher level of self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86 in this study.

Covariates

The caregivers were asked about marital status (“married,” “unmarried,” “divorced,” or “widowed”), maternal and paternal education level (“junior high school,” “dropout high school,” “high school,” “technical college,” “junior college,” “dropout college education,” “college education,” “graduate college,” “other,” or “unknown”), annual household income (in JPY1 million units; JPY110 equivalent to USD1), lack of daily necessities (“yes” or “no”), and the experience of relocation (“yes” or “no”). As for children’s sex, height, and weight, the eighth grade answered the questions themselves while caregivers of the fifth grade answered on behalf of them. Children’s body mass index (BMI) was calculated by WHO Growth reference 5–19 years and categorized into “underweight,” “normal,” and “overweight” (de Onis et al., 2007).

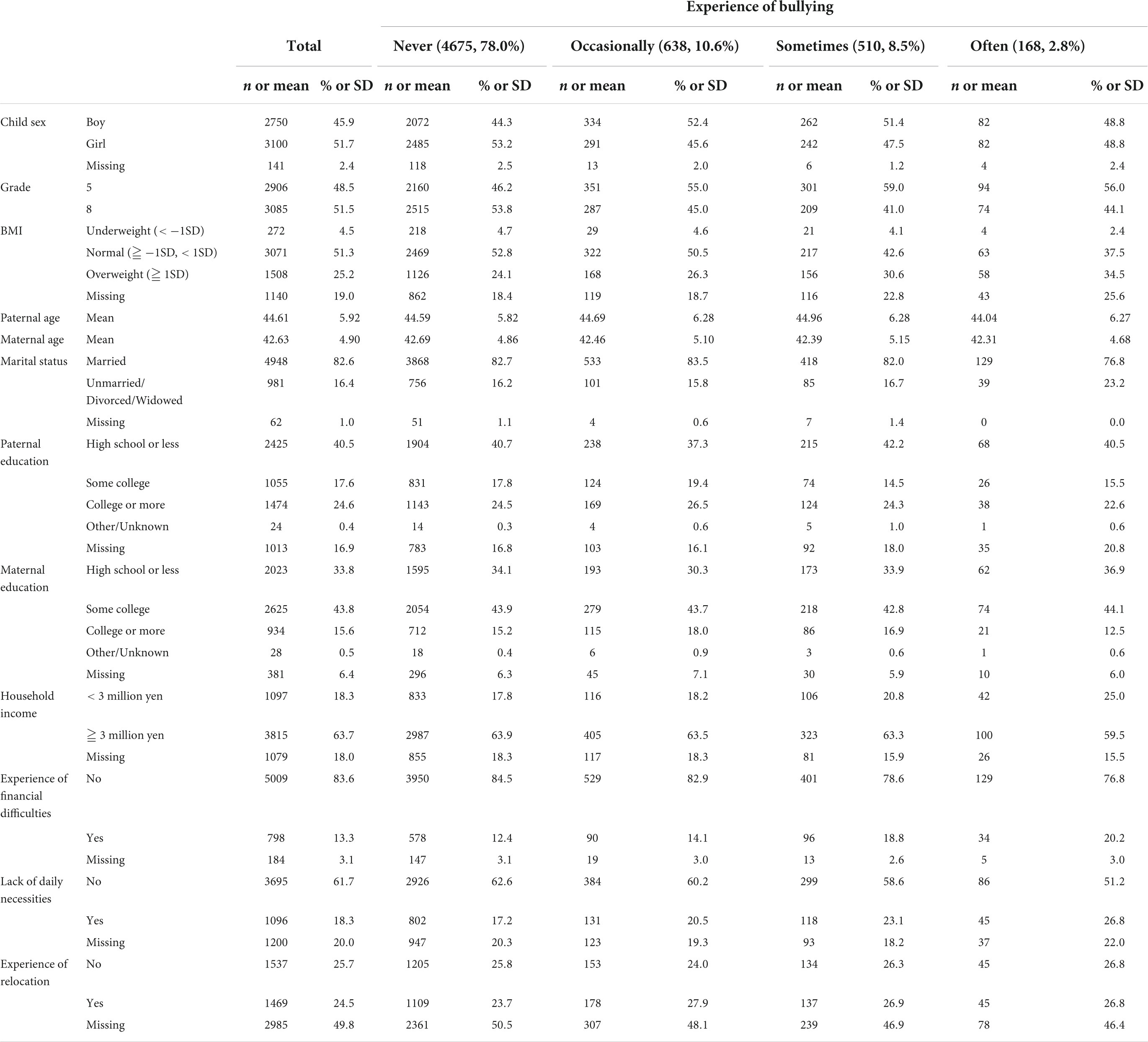

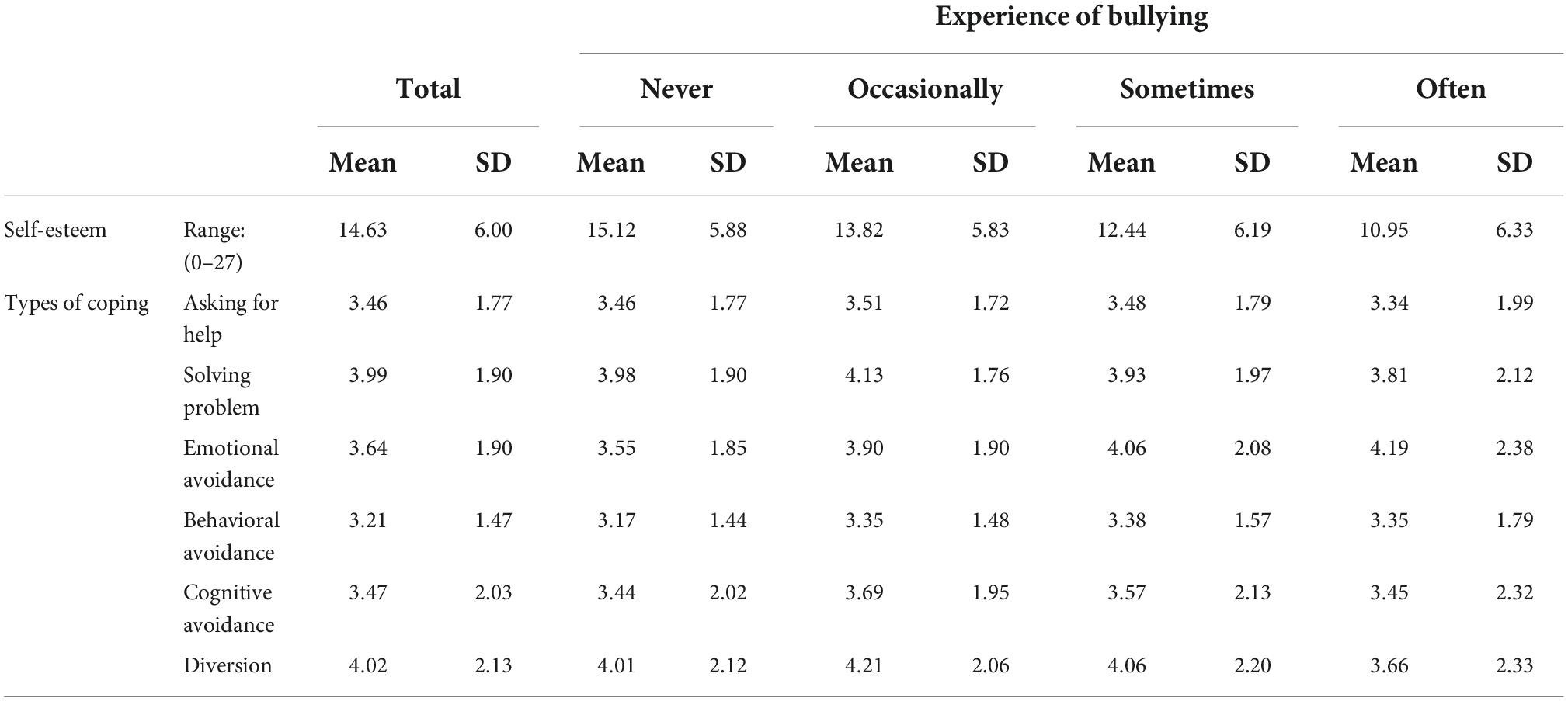

School location was categorized with municipalities where the schools that joined our study were located (Table 1). As for scores of coping ways, the category of diversion had the highest mean, while behavioral avoidance had the lowest mean. Details are shown in Table 2.

Statistical analysis

First, a multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the association between bullying experience and self-esteem. The independent variable was the frequency of being bullied (i.e., never, occasionally, sometimes, and often). The dependent variable was the total score of self-esteem. Then, the child’s sex (“male” or “female”), BMI (“underweight,” “normal,” or “overweight”), grade (“5th” or “8th”), lack of daily necessities (“yes” or “no”), the experience of financial difficulties (“yes” or “no”), household income, mothers’ educational background, fathers’ educational background, experience of relocation, parents’ marital status, and school location were added as confounders.

Then, we also performed a multivariate linear regression analysis to examine the moderating effect of six types of coping as an interaction term (i.e., victimization * each type of coping) on the association between victimization and self-esteem. These analyses were weighted for response rates of each municipality (i.e., probability weight). A significant level in this study is 5%. All analyses were conducted by using STATA version 15.0 SE (StataCorp. 2017, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Distribution of characteristics

Table 1 shows the distribution of characteristics by frequency of bullying experience. Among all participants, the proportion of the child’s sex and school grade is nearly equal. About 25% of students are overweight. Over half of maternal and paternal age was concentrated between 40 and 49 years, and over 80% of mothers were married. Nearly 60% of fathers had an educational background of some college or less, and over 70% of mothers had a background of some college or less. Nearly 20% had low household income (< JPY3 million), over 10% of caregivers reported that they have experienced financial difficulties, and over 15% of them experienced a lack of daily necessities. Nearly 25% reported experience of relocation.

Among the participants, 4,675 (78.0%) reported they had never been bullied, 638 (10.6%) reported they had occasionally been bullied, 510 (8.5%) reported they had sometimes been bullied, and 168 (2.8%) reported they had often been bullied.

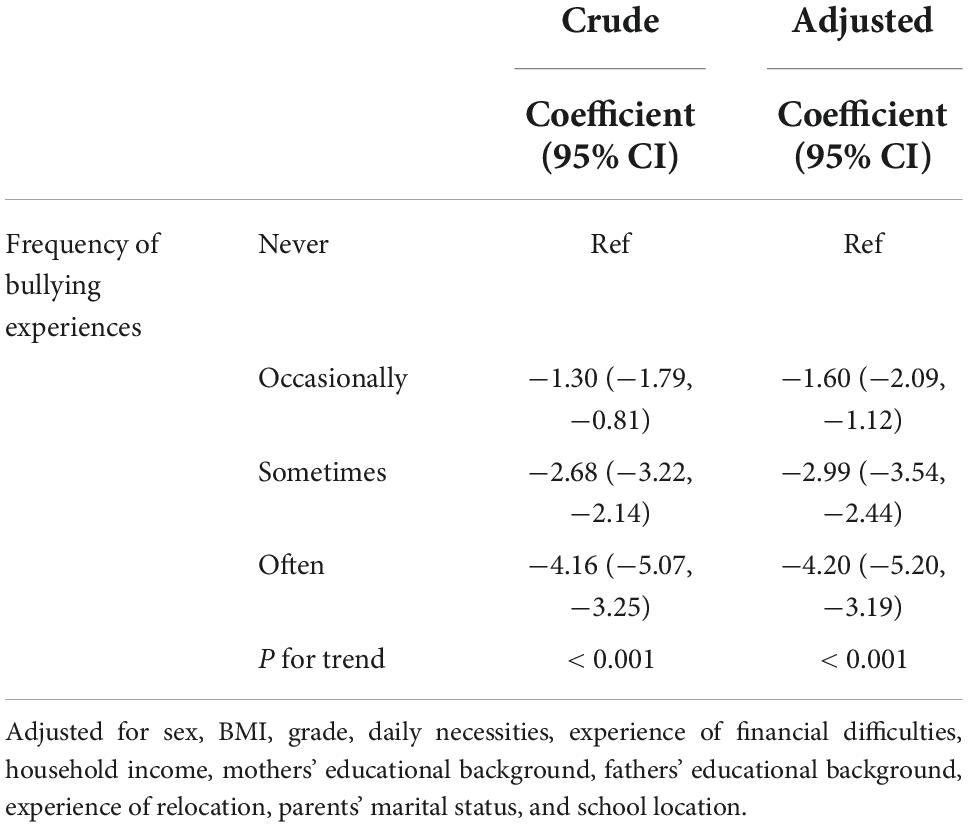

Association between bullying experience and self-esteem

Table 3 shows the association between the frequency of bullying experience and self-esteem. According to the analysis, the more frequently children were bullied, the lower their self-esteem score became even after adjusting for confounders (P for trend: < 0.001); those who had occasionally been bullied (coefficient: −1.60; 95%CI: −2.09, −1.12); those who had sometimes been bullied (coefficient: −2.99; 95%CI: −3.54, −2.44); and those who had often been bullied (coefficient: −4.20; 95%CI: −5.20, −3.19).

The moderating effect of various coping styles on the relationship between bullying experience and self-esteem

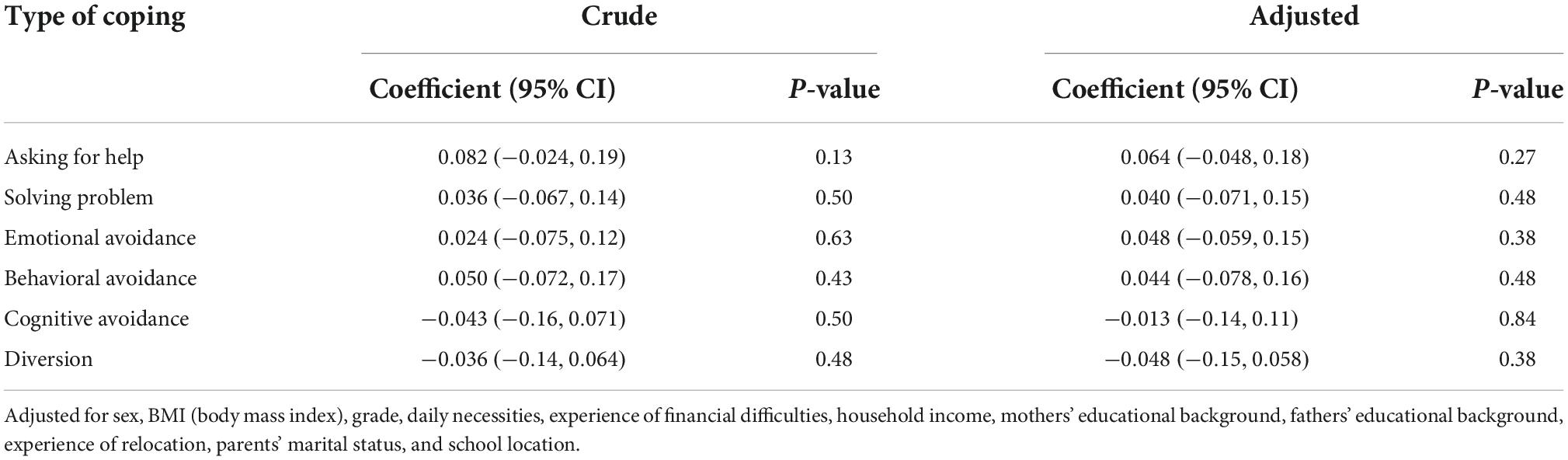

Table 4 indicates that the interaction term of the bullying victimization score as a continuous variable and the score of each coping way as a continuous variable did not make a significant difference in self-esteem score (P > 0.1 in any type of coping). There was no significant influence of coping ways on the association between bullying experience and levels of self-esteem.

Table 4. Effect of each coping skill as a moderator on the association between bullying experience and self-esteem score.

Discussion

In our study, we found that there was a dose–response association between bullying victimization and self-esteem; victims who had been bullied more frequently were likely to have lower self-esteem. Furthermore, any type of coping did not moderate the association, that is, victims’ self-esteem was consistently deteriorated by bullying experience, regardless of coping skills.

Our finding on the association between bullying victimization and low self-esteem was consistent with the hypothesis. Based on the diathesis-stress model, bullying victimization, or negative evaluations from others, can activate cognitive vulnerabilities (Swearer and Hymel, 2015). Furthermore, the time perspective can explain the mechanism of the association between bullying experience and low self-esteem. Time perspective refers to individual thoughts and feelings about their past, present, and future (Zimbardo and Boyd, 2015), which is developed and varies in adolescence (Mello, 2019). Bullying experiences may cause negative feelings about the past, present, and future, and more frequency to think about the past, which leads to lower self-esteem according to previous findings (Moon and Mello, 2021).

The lack of moderating effect on the association between bullying experience and self-esteem was inconsistent with previous studies that showed the interaction effect of coping styles on the association between bullying experience and mental health. Our hypothesis that coping skills moderate the association between bullying experience and low self-esteem was not supported. Coping self-efficacy and emotion dysregulation had a mediation effect on the association between cyber victimization and internalizing difficulties (Trompeter et al., 2018), and coping partially mediates the association between appearance−related bullying problems and self−esteem among young students in Australia (Lodge and Feldman, 2007). The way that one seeks help and assertiveness moderated the impact of bullying victimization on individual well-being including self-esteem, whereas avoidance had a mediation effect on the relationship on workplace bullying in South Africa (Bernstein and Trimm, 2016). Although these studies reported that specific ways of coping had moderating or mediating effects on the association between bullying victimization and self-esteem, our study did not find any moderating effects of coping ways. We consider this inconsistency to be attributed to the specific characteristics of the Japanese culture, that is, collectivism. Compared with other cultures, the Japanese are more likely to think that individuals should behave in a similar way to others. Although individualism had been prevalent as modernization progressed around the world, collectivistic values remained in Japan in some aspects of family and friendship (Hamamura, 2012). Furthermore, the number of Japanese who selected “respect individual rights” as an important moral principle had decreased. Thus, a coping strategy may not protect from deterioration of mental health because students who behave based on a coping strategy will be seen as outliers, which would lead to further isolation from peers. As a result, bullying in Japan would have a tragic impact on victims, regardless of their coping capability.

According to our findings, a strategy that promotes children’s coping skills may not be helpful to mitigate the adverse impacts of bullying experiences, at least among Japanese children. Rather than the strategy to change the children’s behaviors, it may be important to create a support system around the children. A previous study showed that social support mitigates the adverse impacts of bullying experiences (Machmutow et al., 2012; Mishna et al., 2016). An approach to foster the relationship between children and parents, teachers, or other adults and to create a third place for children may be effective to buffer the impacts of bullying and prevent bullying on self-esteem (Fujiwara et al., 2020).

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study. We could not evaluate the causality between bullying victimization and low self-esteem. Some studies mentioned reverse causality, that is, low self-esteem in children led to a higher likelihood of being victims of school bullying (Brito and Oliveira, 2013; Silva et al., 2020). Second, the data of the K-CHILD study do not reflect the situation throughout Japan. Furthermore, the response rate in Kochi City was lower than in other municipalities. Therefore, this study cannot be generalized to the whole of Japan. Third, the experience of being bullied is a self-rated question, so some students might not remember correctly, and some students might not want to answer the question to keep their experience a secret. Besides, some students answered unknown questions on bullying (4.21% of 6,606 students), but we have excluded them from this study. Therefore, there is a possibility that students who had been bullied and kept it secret were excluded. Fourth, we could not assess the type of bullying, intentionality, repetition, and power imbalance due to using one question “Have you ever been bullied?” in this study. Especially, the power imbalance between the bully and victim is an important aspect because it helps to distinguish between bullying and other aggressive behaviors (Aalsma and Brown, 2008). Although it remains difficult to define bullying and a detailed assessment of bullying has risks in the school (Olweus, 1993; Basilici et al., 2022), we need to assess the multiple aspects of bullying experiences in a further study.

The most significant point in the settings of education is to eradicate bullying itself. Bullying has a major and lasting impact on students’ mental health and suicidality. Therefore, if adults noticed or encountered victimization, they should not ask victims to cope themselves but instead, make an effort not to repeat the bullying.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the restriction of IRB. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to TF, ZnVqaXdhcmEuaGx0aEB0bWQuYWMuanA=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University (M2017-243). Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TF designed the study. TF and SD managed the administration of the study, including the ethical review process, and provided critical comments on the manuscript related to the intellectual content. YS analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers: 16H03276, 17K19794, 19H04879, 21H04848, 21K18294, and 22A101).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aalsma, M. C., and Brown, J. R. (2008). What is bullying? J. Adolescent Health 43, 101–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.001

Arsandaux, J., Michel, G., Tournier, M., Tzourio, C., and Galéra, C. (2019). Is self-esteem associated with self-rated health among French college students? a longitudinal epidemiological study: the i-Share cohort. BMJ Open 9:e024500. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024500

Azúa Fuentes, E., Rojas Carvallo, P., and Ruiz Poblete, S. (2020). [Bullying as a risk factor for depression and suicide]. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 91, 432–439. doi: 10.32641/rchped.v91i3.1230

Barcaccia, B., Pallini, S., Baiocco, R., Salvati, M., Saliani, A. M., and Schneider, B. H. (2018). Forgiveness and friendship protect adolescent victims of bullying from emotional maladjustment. Psicothema 30, 427–433.

Basilici, M. C., Palladino, B. E., and Menesini, E. (2022). Ethnic diversity and bullying in school: a systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 65:101762. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2022.101762

Bernstein, C., and Trimm, L. (2016). The impact of workplace bullying on individual wellbeing: the moderating role of coping. SA J. Hum. Resource Manag. 14, 1–12. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v14i1.792

Brito, C. C., and Oliveira, M. T. (2013). Bullying and self-esteem in adolescents from public schools. J. Pediatr. 89, 601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.04.001

Cong, C. W., Ling, W. S., and Aun, T. S. (2021). Problem-focused coping and depression among adolescents: mediating effect of self-esteem. Curr. Psychol. 40, 5587–5594. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00522-4

de Onis, M., Onyango, A. W., Borghi, E., Siyam, A., Nishida, C., and Siekmann, J. (2007). Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 85, 660–667. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497

Doi, S., Fujiwara, T., and Isumi, A. (2020). Association between maternal adverse childhood experiences and child’s self-rated academic performance: results from the K-CHILD study. Child Abuse Negl. 104:104478. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104478

Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 21, 219–239. doi: 10.2307/2136617

Fujiwara, T., Doi, S., Isumi, A., and Ochi, M. (2020). Association of existence of third places and role model on suicide risk among adolescent in japan: results from A-CHILD study. Front. Psychiatry 11:529818. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.529818

Hamamura, T. (2012). Are cultures becoming individualistic? a cross-temporal comparison of individualism-collectivism in the United States and Japan. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 16, 3–24. doi: 10.1177/1088868311411587

Heine, S. J., and Hamamura, T. (2007). In search of East Asian self-enhancement. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11, 4–27. doi: 10.1177/1088868306294587

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychol. Rev. 106, 766–794. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766

Keane, L., and Loades, M. (2017). Review: low self-esteem and internalizing disorders in young people - a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 22, 4–15. doi: 10.1111/camh.12204

Kobayashi, E., and Farrington, D. P. (2020). Why do japanese bully more than americans? influence of external locus of control and student attitudes toward bullying. Educ. Sci. Theory Practice 20, 5–19. doi: 10.12738/jestp.2020.1.002

Lodge, J., and Feldman, S. S. (2007). Avoidant coping as a mediator between appearance-related victimization and self-esteem in young Australian adolescents. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 25, 633–642. doi: 10.1348/026151007X185310

Machmutow, K., Perren, S., Sticca, F., and Alsaker, F. D. (2012). Peer victimisation and depressive symptoms: can specific coping strategies buffer the negative impact of cybervictimisation? Emot. Behav. Difficulties 17, 403–420. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2012.704310

Manani, P., and Sharma, S. (2016). Self esteem and suicidal ideation: a correlational study. MIER J. Educ. Stud. Trends Practices 3, 75–83. doi: 10.52634/mier/2013/v3/i1/1556

McGee, R., Williams, S., and Nada-Raja, S. (2001). Low self-esteem and hopelessness in childhood and suicidal ideation in early adulthood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 29, 281–291. doi: 10.1023/A:1010353711369

Mello, Z. R. (2019). A Construct Matures: Time Perspective’s Multidimensional, Developmental, and Modifiable Qualities. Taylor & Francis: Milton Park. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2019.1651156

Mishna, F., Khoury-Kassabri, M., Schwan, K., Wiener, J., Craig, W., Beran, T., et al. (2016). The contribution of social support to children and adolescents’ self-perception: the mediating role of bullying victimization. Children Youth Services Rev. 63, 120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.013

Moon, J., and Mello, Z. R. (2021). Time among the taunted: the moderating effect of time perspective on bullying victimization and self-esteem in adolescents. J. Adolescence 89, 170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.05.002

Nagamitsu, S., Mimaki, M., Koyanagi, K., Tokita, N., Kobayashi, Y., Hattori, R., et al. (2020). Prevalence and associated factors of suicidality in Japanese adolescents: results from a population-based questionnaire survey. BMC Pediatr. 20:467. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02362-9

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at School: What we Know and what we can do (7a; Reimpresión)”. Oxford: Blackwell.

Otake, K., Shimai, S., and Soga, S. (2001). Coping scale brief version elementary school children health. Hum. Sci. 4, 1–5.

Overholser, J. C., Adams, D. M., Lehnert, K. L., and Brinkman, D. C. (1995). Self-esteem deficits and suicidal tendencies among adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 34, 919–928. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00016

Sakurai, S. (1992). The investigation of self-consciousness in the 5th-and 6th-grade children. Japanese J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 32, 85–94. doi: 10.2130/jjesp.32.85

Silva, G., Lima, M. L. C., Acioli, R. M. L., and Barreira, A. K. (2020). Prevalence and factors associated with bullying: differences between the roles of bullies and victims of bullying. J. Pediatr. 96, 693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2019.09.005

Smith, L., Shin, J. I., Carmichael, C., Oh, H., Jacob, L., López Sánchez, G. F., et al. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of multiple suicide attempts among adolescents aged 12-15 years from 61 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. J. Psychiatr. Res. 144, 45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.047

Sowislo, J. F., and Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 139, 213–240. doi: 10.1037/a0028931

Swearer, S. M., and Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. Am. Psychol. 70:344. doi: 10.1037/a0038929

Trompeter, N., Bussey, K., and Fitzpatrick, S. (2018). Cyber victimization and internalizing difficulties: the mediating roles of coping self-efficacy and emotion dysregulation. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 46, 1129–1139. doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0378-2

van Geel, M., Goemans, A., Zwaanswijk, W., Gini, G., and Vedder, P. (2018). Does peer victimization predict low self-esteem, or does low self-esteem predict peer victimization? meta-analyses longitudinal studies. Dev. Rev. 49, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2018.07.001

Zhong, M., Huang, X., Huebner, E. S., and Tian, L. (2021). Association between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in children: the mediating role of self-esteem. J. Affect. Disord. 294, 322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.016

Zhou, Z.-K., Liu, Q.-Q., Niu, G.-F., Sun, X.-J., and Fan, C.-Y. (2017). Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: a moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Personal. Individual Differ. 104, 137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.040

Zimbardo, P. G., and Boyd, J. N. (2015). “Putting time in perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metric,” in Time Perspective Theory; Review, Research and Application: Essays in Honor of Philip, eds M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, and W. van Beek (Berlin: Springer), 17–55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07368-2_2

Keywords: bullying experience, self-esteem, coping skill, Japan, adolescent

Citation: Saimon Y, Doi S and Fujiwara T (2022) No moderating effect of coping skills on the association between bullying experience and self-esteem: Results from K-CHILD study. Front. Psychol. 13:1004482. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1004482

Received: 27 July 2022; Accepted: 15 November 2022;

Published: 14 December 2022.

Edited by:

Michelle F. Wright, DePaul University, United StatesReviewed by:

Quynh Anh Tran, Hanoi Medical University, VietnamDiana Alves, University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2022 Saimon, Doi and Fujiwara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takeo Fujiwara, ZnVqaXdhcmEuaGx0aEB0bWQuYWMuanA=

Yukino Saimon

Yukino Saimon Satomi Doi

Satomi Doi Takeo Fujiwara

Takeo Fujiwara