- 1Independent Researcher, Mexico City, Mexico

- 2Department of Social and Developmental Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Formative intervention is a participatory methodology that supports organizational change by means of an interactive and systematic dialogue carried out by researchers and participants. In this process, the researchers contribute to expanding the conversational space in the organization by supporting participants in examining and reflecting on their own work practices, as well as in modeling, shaping, and experimenting with innovations. Drawing on transcripts of videotaped sessions, this study analyzes how change is discursively sustained by the researchers who conduct the meetings within a formative intervention in a Mexican hospital. The quantitative and qualitative analysis focuses on the collective pronoun “we” as a membership categorization device deployed by the researchers for rhetorical and pragmatical aims, such as questioning about the state of necessity for the intervention, engaging the participants, or introducing a proposal of innovation with the participants. Results show how group membership and social identity markers are used by researchers to support emerging forms of collaboration, involvement of participants and the creation of common ground during the intervention process. In terms of the practical implications of the study, an informed and strategic use of membership categorization devices used by the researcher can increase the effectiveness of their formative and expansive role.

Introduction

Formative Interventions for the Development of Workgroups

Formative intervention is a participatory methodology to support a group of professionals, within a work activity system, in the analysis, design, and implementation of new ways of working (Engeström, 2011). In this model, innovations are negotiated with the practitioners, and data are collected to explore the functioning and potential of such groups in their own context. The process of qualitative improvement and change pursued by this methodology is conceived as a progressive increase in the co-construction of new meanings and new work practices (Zucchermaglio and Alby, 2006). Change is approached as an emergent property of the participating organizational group, and the competencies that are needed to develop such a process are considered as located and distributed within it.

The methodology of formative intervention is implemented and developed, in practice, by means of “a toolkit called the Change Laboratory” (CL) (Engeström, 2015), inspired by the work of Vygotskij (1934/1990) and based on the activity theory (Engeström et al., 1996; Virkkunen and Newnham, 2013). This methodology has been widely applied in Europe (see Engeström, 2005), both in healthcare and educational organizations (Stoppini et al., 2009; Ivaldi and Scaratti, 2020) and is at an early stage of development in Latin America (see Montoro and Brito, 2017; Pereira-Querol et al., 2019; Brito, 2020; Vilela et al., 2020).

The CL, which is essentially based on the guided activation of “self-managed” improvement processes, consists of a series of sessions in which practitioners from an organization are supported by means of a bottom-up participatory approach in analyzing the history of their activity system, including sociohistorical tensions and contradictions. One of the main objectives of a CL process consists of unlocking the transformative agency of practitioners to become protagonists in the creation and implementation of a new model of practice (Engeström, 2015; Laitinen et al., 2016). The CL methodology does not provide prepackaged solutions “from the outside” but aims to bring out and develop in the participating group the ability to act in order to transform the activity system in which they work.

To this end, participants are actively and directly involved in the analysis, sensemaking process, and interpretation of their own activity relying on the data collected by means of individual and group interviews, microanalysis of significant and/or problematic observations, narratives, and/or video interactions (Ivaldi and Scaratti, 2020). Such a process involves several sessions and might lead to finding new solutions to problems and possibilities for organizational “expansion.” This type of intervention requires the contribution and experimental attitude of the researchers who play an active role that goes beyond the traditional perspective of a casual observer and facilitator (Engeström, 2015). In this sense, for participants to take the lead in the design and experimentation of new working practices, researchers introduce their own ideas and intentions with the aim of provoking and sustaining a cycle of expansive learning.

The role of the researcher is, therefore, to expand the conversational space during the intervention in order to support participants in examining and reflecting on the current state of their activity system, as well as in modeling, shaping, and experimenting with innovations. Researchers have to sustain dialogic sensemaking when creating socially useful knowledge, acting based on a sort of anticipational fluidity (Cunliffe and Locke, 2020) as a way of relating with others when working with differences. Such differences are experienced through the unfolding living flow within the moment of conversation.

The contribution of researchers is based on the collaborative introduction and application of new tools and ideas through “determined and systematic dialogue” (Engeström, 2015). Consequently, the dynamism of the intervention stems from the interplay of ideas and intentions between researchers and participants. During a CL, sessions are videotaped for the collection of longitudinal data to analyze the intervention process and its development, including the interactions between researchers and the participating group.

In this study, the data collected from the videotaped sessions are employed to examine the discursive practices of researchers during the intervention.

Social Identity as a Rhetorical and Pragmatic Resource

Studies carried out on intergroup relations in theories of social identity (Tajfel, 1981) and self-categorization (Turner et al., 1987) have constituted one of the richest areas of experimental social psychology. Tajfel’s theory explains how social identity influences intergroup behavior, whereas Turner’s theory of self-categorization focuses on the psychological nature of belonging to a group and on the socio-psychological basis of group behavior. Most of the empirical research carried out in this area has concentrated on intergroup behavior between large social groups (distinguished by race, nation, ethnic group, and so forth) or in experimentally created groups (using the technique of minimal paradigms; Billig and Tajfel, 1973). But what happens in small groups, characterized by multiparty interactions between members? For discursive social psychology (Billig, 1987; Cole, 1996; Edwards, 1998), social (and self) categorization processes are situated results of negotiation discursive practices occurring in interactions with others. In this view, identity is “something that people do which is embedded in some other social activity, not something they are” (Widdicombe, 1998:191).

Sacks (1992) highlighted how social identity choices and moves are both indexical (defined by the terms used to mark the belonging social categories to give salience to) and occasioned (there is a particular social context where the categories should assume some relevance). Each group member has different identities to show and to give salience to for positioning the self and the other rhetorically (Hester and Eglin, 1997). The choice between these possibilities of positioning the self and the others (Harré, 1989; Muhlhausler and Harré, 1990) is guided by social factors such as the relationship between member, their roles, and the content and scope of the group. Identity is a resource that participants are using rhetorically and strategically during social interactions, but the possibility of using different social identities to negotiate and build ingroup-outgroup categorizations is also context-related (Zucchermaglio, 2005; Fantasia et al., 2021). Social identities can become an important negotiation content between members of a group rather than a stable characteristic and an a priori of discourse in interaction. The social context itself plays an active role in allowing some possible identity choices but also in defining the access of each group member to the identity negotiation process.

Many studies have shown how, even using minimal lexical choices, speakers mark those aspects of their own (or other) social identity that they intend to present as relevant in specific interactive contexts (Drew and Heritage, 1992; Sacks, 1992; Hester and Eglin, 1997). In particular, pronouns are discursive components that, together with lexical selection (Drew, 1992), could act as a powerful “membership categorization device.”

In this theoretical and methodological framework, we focus on how the researcher, as part of an intervention process, discursively supports change in the group of healthcare professionals of a Mexican hospital, through the construction and negotiation of specific social identities. Specifically, we present both quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis of how, among the various discursive devices at hand, the researcher strategically uses the pronominal markers “we” to evoke social groups and identities that are rhetorically functional to achieve the goals of the organizational change intervention. Our aim is to provide a micro- and discursive analysis of the strength and effectiveness of organizational change interventions, usually and mostly described and analyzed by considering more general dimensions of participation.

Methods

This study is based on a formative intervention carried out during May and June 2017 in a public hospital located in the central part of Mexico (State of Guanajuato). The intervention was conducted by a multidisciplinary team of 2 senior researchers and 2 assistants with the participation of 25 members of the hospital board of directors. The intervention was requested to support the participants in the analysis of their work activity and functioning as a professional team.

The group of participants consisted of area coordinators, heads of departments, and hospital directors, both medical and administrative. The intervention was conducted through seven sessions, with an average duration of 80 min and at a rate of one per week. The language used in the sessions was Spanish. The objectives of the intervention were to increase integration, collaborative work, and improve interprofessional relations, as a starting point to enhance the performance and effectiveness of the board of directors (Montoro and Brito, 2017). As an “external” measure of the achievement of these objectives (which is not the focus of the paperwork), a questionnaire was distributed to all participants at the end of the last work session. Analysis of the responses reveals relevant clues of agentive speech in the participants and a greater willingness to engage collaboratively with coworkers.

The data analyzed in the study are the verbatim transcripts of the seven intervention’s videotaped sessions. As a preliminary analysis, we first read through the transcripts to explore the presence and distribution of pronouns in the participants’ discursive sequences. Since pronouns are easily identifiable in transcriptions, their occurrence constitutes a finite class that can be identified and counted. We counted, therefore, occurrences of “we” (“nosotros” in Spanish) in each session. Moreover, we also highlighted who was the speaker and which collective identity categories were marked in each session.

As pronouns in Spanish are implicitly marked by verbs that vary according to the grammatical person, their marking in discourse is not necessary: I, you, we, and so forth can, and often are, be elided as they are implicitly marked by the verbs according to the grammatical person. In other words, their occurrence in conversation requires motivation and has a rhetorical function. For this reason, the use of the collective pronoun “we” acquires a specific relevance, as it represents a particular choice of the speaker. The quantitative analysis oriented the subsequent qualitative analysis and codification, which focused on how, when, and with what rhetorical functions the researchers used collective identity categorizations in the sessions. Subsequently, a micro- and discursive analysis focused on the identities marked during the first and fourth sessions was carried out to discuss exemplary excerpts corresponding to each identity category and rhetorical function.

Results

Preliminary Analysis of Identity Category Occurrences

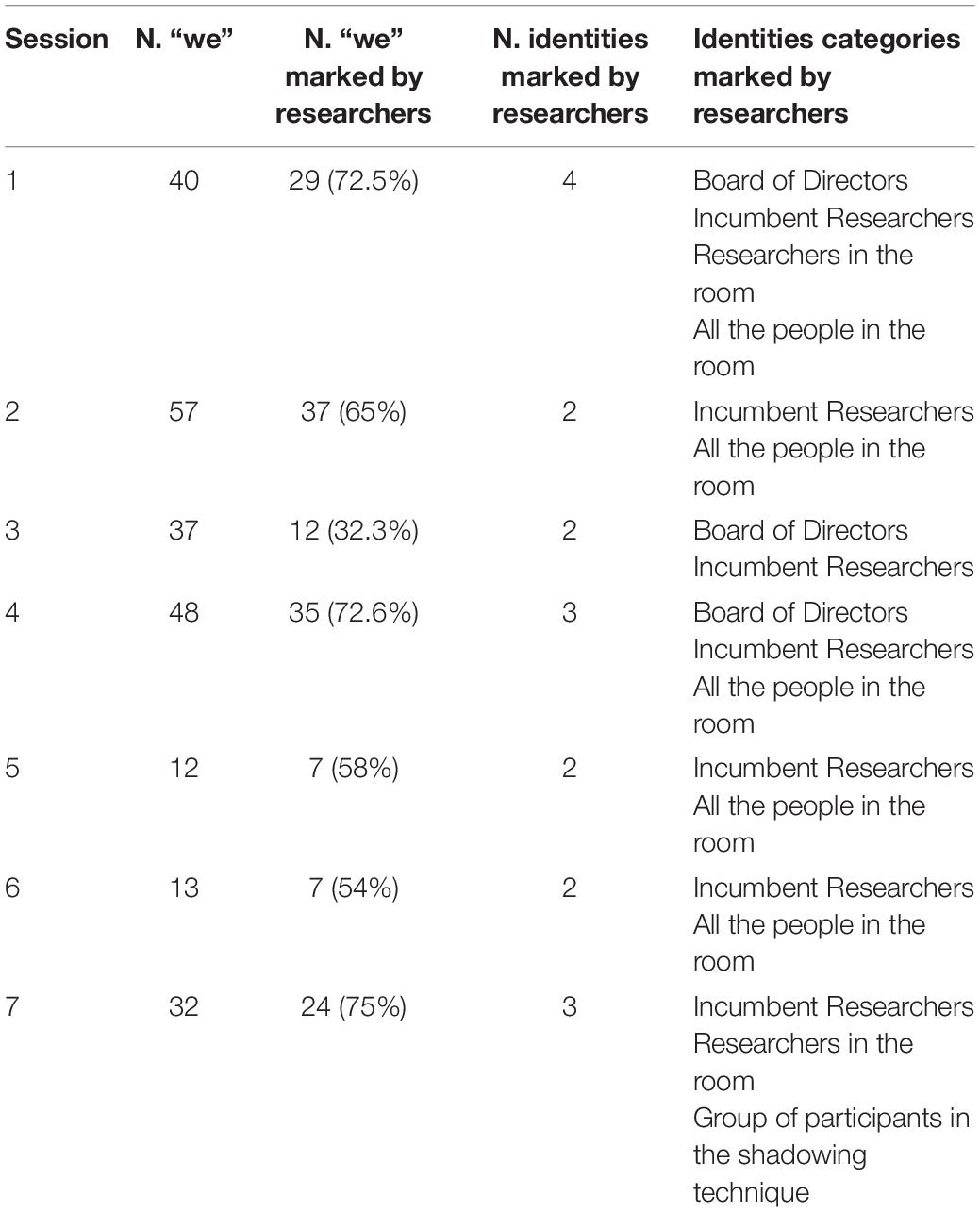

Our preliminary analysis on the occurrences of the “we” pronoun was functional for identifying the identity categories that emerged and how often these categories were employed by participants. Table 1 provides a quantitative overview of the identity categories that emerged across the sessions and of the speakers marking them. Among the participants, the researcher results to be the one who most frequently invokes collective identities in every session (except for session n. 3, see Table 1).

The identity categories that were codified from the data and account for the “we” marked by the researchers during the sessions are as follows:

Board of directors. This “we” was codified each time the researcher referred to the group of the board of directors, i.e., area coordinators, heads of department, and hospital directors, both medical and administrative, who could be in the room during the session or not.

Incumbent researchers. This “we” was codified when the researchers referred to themselves as senior researchers in charge of the intervention and responsible for conducting the sessions.

Researchers in the room. This code states the “we” used to point out the research team in a broad sense. It was codified each time the researcher indicated the research team made up of two incumbent researchers and two junior researchers, who were present in the session and jointly were in charge of the setting organization, video cameras placement, preparation of material, and so forth.

All the people in the room. This “we” was codified each time the researcher referred to all the participants present in the session, both members of the board of directors, senior researchers, and assistants.

Participants in the shadowing technique. This group was codified when the researcher pointed out to the participants in a shadowing exercise carried out in the last two sessions (codified just once in session n. 7).

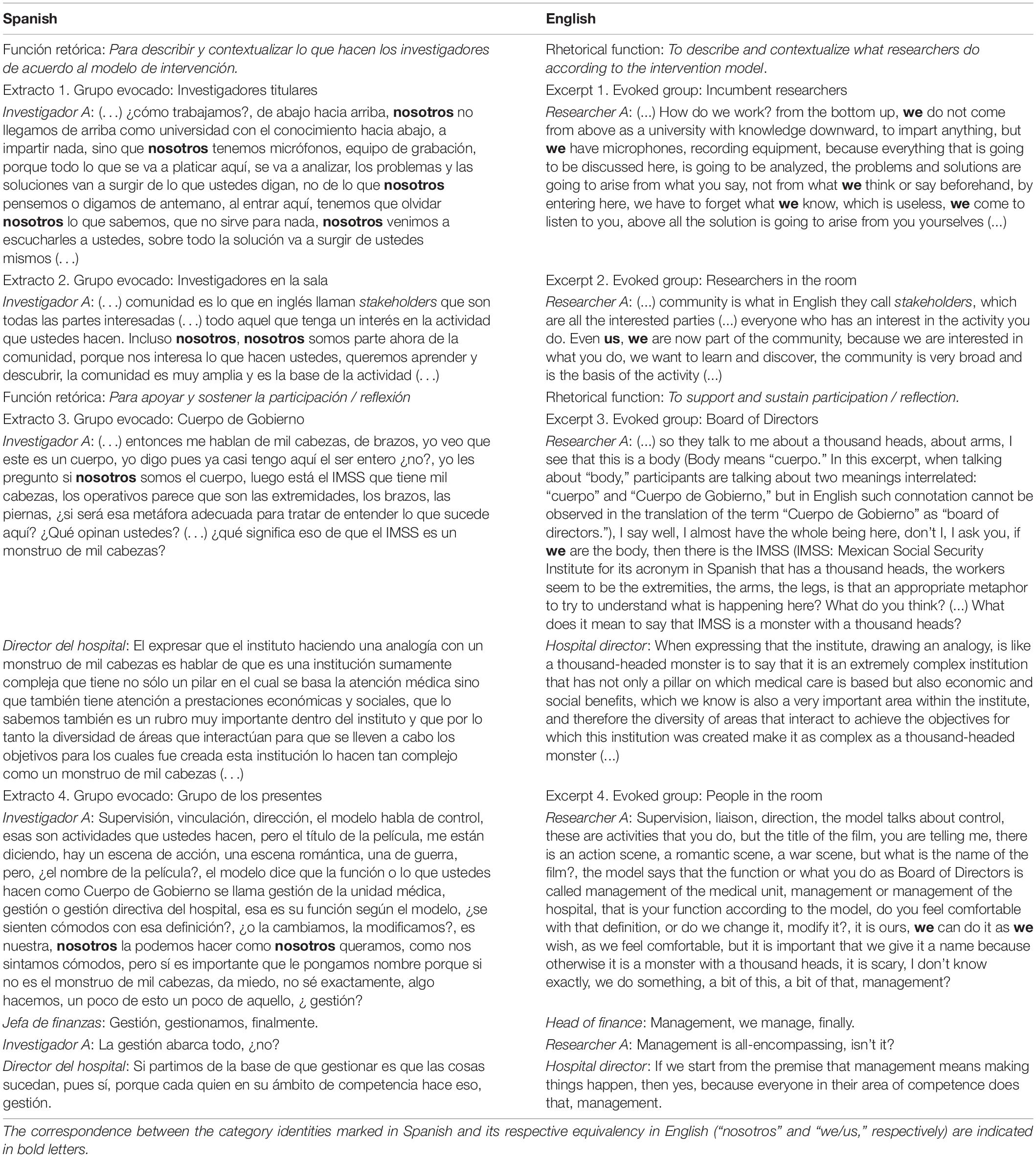

The identity categories made relevant by researchers appeared as broadly linked to the aims of the different sessions of the intervention. We focused here on session n. 1 (Table 2) and session n. 4 (Table 3) since they were particularly central for the successful accomplishment of this intervention. The specific objectives of the first session were to question the state of necessity for the intervention as well as to engage the participants. In the fourth session, the aims were centered on supporting the participants in focusing on improvement areas and proposing alternatives and innovations to improve their work practices. In the following paragraphs, we described and provided examples of how identity categories were used by researchers in these sessions.

Identity Categories Used by Researchers in the First Session

During this meeting, the researchers presented the methodology of the intervention, describing and contextualizing its theoretical and epistemological principles. This was the first time they met with the participants and was the initial opportunity to negotiate and inquire them about the state of necessity for the intervention, as required in the formative intervention approach (Engeström et al., 1996).

Excerpt 1 (Table 2) provides an early example of identity categorization employed by researchers, where the “we” indicates the researchers conducting the intervention. There were four researchers in the room but two of them were juniors who observe and do not intervene in the session. Here the “we” refers to senior researchers who represent a university role and methodological expertise (how do we work?). This “we” is fielded to be depowered with respect to the “you” of the participants, who are presented as repositories of knowledge and agency. There is a reformulation of who has the direction of the intervention, from the researchers to the participants, therefore an attempt to propose this role to the participants in order to nominate them to an active and agentic role. The rhetorical intention is, therefore, to explain the intervention methodological approach and describe what researchers do with an informative purpose, but there is also a subtle attempt to persuade the participants by requesting them to get involved in the enterprise and to be its protagonists. Without this adhesion, in fact, the formative intervention model could not have been put into practice according to its main theoretical and methodological principles (Virkkunen and Newnham, 2013).

A different nuance of the same rhetorical intent is found in Excerpt 2 (Table 2), where Researcher A explains to the participants a theoretical concept of the intervention model (the concept of community as a component of an activity system). Researcher A exemplifies such a concept by including the category “researchers in the room” (incumbent and junior researchers) as part of the community of the hospital activity system at that moment. In doing so, the researcher establishes a link between the practitioners and the researchers as “newcomers,” offering a new and broader perspective related to the theoretical concept presented.

Excerpt 3 (Table 2) shows another rhetorical use of the groups’ categorization. In this case, the identity marker used by the researcher refers to “we” as the board of directors, a category into which the researcher puts himself (“if we are the body”). In this excerpt, when talking about “body,” the participants are expressing two meanings interrelated: body and board of directors (cuerpo and Cuerpo de Gobierno in Spanish, respectively). In this regard, the researcher solicits a reflection on the multiple relationships of the board with other organizational actors through the metaphor of the “body” but also solicits the group participation by means of asking numerous questions to the participants. The researcher asks participants a question (“I ask you”) but formulates the content as if the participants had asked it (“if we are the body”). In this way, the researcher models a reflective attitude that consists of adopting the metaphor of the “body” and, in doing so, his rhetorical purpose is to support reflection and leave the participants the role of protagonists and those who have the main agency. The researcher builds such a discursive structure by means of questions and proposals, using a sort of “ventriloquism” (Carter, 2002), to encourage participants to question themselves on certain issues. At the same time, the researcher makes an effort to not be the only one to propose topics for discussion, which would be contrary to the formative intervention methodological principles. It is possible to affirm that the changing identity category of the researcher for a moment (“I ask you, if we are the body”) is one of the ways in which this nondirective and participatory approach is discursively performed, but at the same time, it reveals a commitment and an important rhetorical work aimed at negotiating the engagement of the participants.

In Excerpt 4 (Table 2), the researcher shows a different use of the pronoun “we” referring in this case to the category “all people in the room”. There is a shift from directing the question to board members to phrasing it using a broader and more inclusive identity category (“do you feel comfortable with that definition, or do we change it, modify it?”). Here Researcher A uses the category to activate a reflection that respects the bottom-up rule and he puts himself in the group, the group of those who seek a definition for the management activity of the board of directors. The attempt consists in constructing this enterprise as shared and collaborative, in this way the researcher accomplishes two things, i.e., he reaffirms the participatory approach and at the same time involves and orients the participants in such a defining task.

During the first session, the collective identity markers were used to create engagement and influence in the group without being directive, trying to respect the bottom-up participatory principle through questions and proposals, through the identity categories shown here. These identity markers are used by the researcher to promote reflection and action, but they do so by constructing the procedural directions as shared, as something that comes from the group of participants and not from the researchers. In doing so, the identity markers are employed to serve the purposes of the session and contribute to their achievement, serving mainly on how to achieve such purposes.

Identity Categories Used by Researchers in the Fourth Session

The objectives of the fourth session consisted in supporting the participants to identify improvement areas and propose them alternatives and innovations conducive to the development of their work practices. In Excerpt 5 (Table 3), the identity category “incumbent researchers” is evoked to represent the researchers as the only ones with the competence to see what the object of the intervention is from a theoretical point of view (“the hospital as a whole, a collective activity”) (Engeström, 2015). These early “we’s” are in some ways a transgression from considering only the participants as repositories of knowledge, even though later the “we” of the researchers is evoked to empower the board reiterating the bottom-up participatory approach (“we want to put you in the leading role”). It seems that such an approach constrains the way researchers proceed discursively. In this regard, the use of such “we” pronouns by researchers performs a sort of compromise with respect to leaving everything completely open and in the hands of the participants. However, at the same time, the researchers tend to influence toward an outcome and move the intervention forward.

Excerpt 6 (Table 3) is still an example of the identity category “we” as “Incumbent researchers,” used in this case to support the participating group in identifying an improvement area and adopting a change proposal (“this is a model that we are proposing to you”). The rhetorical intentions linked to the category seem to continue with a negotiation process in order to launch resources conducive to change and, in doing so, stimulate participants’ transformative agency. However, the use of “we” as incumbent researchers achieves a distancing from the participants and connotes the researchers as holders of a methodological competence capable of orienting some aspects of the intervention. During the fourth session, such “we as researchers” seems less participatory than in the first session but exerts more pressure not surprisingly in such a central moment of the intervention.

In Excerpt 7 (Table 3), the researcher supports both participation and reflection by remarking on the board-of-directors category. On the other hand, the researcher puts himself as part of such an identity category to start a discussion about how the board members get involved with the local community. By considering himself as part of this group, the researcher opens up the discussion into the topic of patient inclusion, as proposed in the CL methodology (Virkkunen and Newnham, 2013) (“why not, bring a patient, let the patient tell us about a case, that we see from his point of view?”). Establishing a dialogue with the participants in such a direction seems to highlight a barrier observed by the researcher, who adopts this identity category to play a less intrusive role and support the participant group to overcome such barrier (“we call ‘breaking down the barriers’, crossing the barriers, the barrier between us and them”).

In Excerpts 6 and 7, we identified a passage from “we as researchers” (“this is a model that we are proposing to you”) to “we as board of directors” (why not, bring a patient … that we see from his point of view?). This change of identity category seems to push forward the adoption of the methodological principles that in the passage are constructed as shared and applied to the board. In Excerpt 8, the passage continues into the category “all the people in the room” that the researcher uses to support the reflection and discussion on the leadership style topic (“How to lead, as we would like than someone lead to us”).

In summary, during the fourth session, the identity markers are used to frame the focus of the intervention, propose resources conducive to change, and support the collective discussion according to the point of view of researchers. This latter rhetorical function (provide support for the collective discussion) results central to engaging the participants during the first and fourth sessions and can be considered as a specific action that allows the researchers to sustain the reflection process. In this way, researchers used such identity markers to develop the intervention and achieve its methodological goals.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we focused on how the researchers, among the various discursive devices at disposition, use the pronominal markers “we” to evoke social identities that are rhetorically functional to achieve the objectives of an intervention process carried out with a group of healthcare professionals.

In the data presented, researchers rely on the use of identity categories to engage participants in shared meaning making (Sacks, 1992), to negotiate their active involvement in the intervention, and to promote actions leading to change. Results show how the identity categories are strictly linked to the aims of the different sessions of the intervention. The identity categories marked by the researchers were used either as an affiliative device to create a closer engagement (“we” as “all the people in the room”) or to present the intervention as a shared and collaborative activity (“we” as “board of directors”) (in the first session) or rather as a distancing device between researchers and participants in order to assert knowledge of researchers and epistemic authority in finding proposals that lead to change (“we” as incumbent researchers) (in the fourth session).

We observed a tension connected to the identity categories used by researchers, consisting in the action of influencing, making proposals, and adopting an active role, as they try not to intervene too much and to respect the bottom-up participatory principle. This tension, in contrast, is just what qualifies and characterizes the “philosophy” at the base of the CL, as “guided activation of “self-managed” improvement processes” (Engeström et al., 1996; Virkkunen and Newnham, 2013).

The observed tension exemplifies a crucial aspect in relation to how the formative intervention model is discursively operationalized, particularly, in relation to how researchers seek to accomplish rhetorically its epistemological principles (Sannino and Engeström, 2017). The data presented contribute to shed light on an area of usefulness to analyze the formative intervention process and the contribution of researchers from an innovative approach. The empirical analysis of group membership and social identity markers has proved to be useful to assess emerging forms of collaboration in the context of the intervention and, more generally, as indicators of the effectiveness of professional practice of researchers in the formative intervention.

Future research developments plan to use such micro- and discursive analysis not only to investigate other contexts of formative intervention but also to analyze the use of social identity markers by group of participants as a “measure” of their involvement in the development of innovation in their work activity system.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by Local Research and Ethics Committee, Mexican Institute of Social Security, approval number R-2017-1003-10. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for their participation in this study.

Author Contributions

HB provided the conception and design of the study, contributed to the data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article. FA and CZ provided the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revised it critically for final submission. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Open access publication fees were provided by funding received by Sapienza (Grant No. RP11715C303B6FEB).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Billig, M. (1987). Arguing and Thinking: A Rhetorical Approach to Social Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Billig, M., and Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 29, 97–119.

Brito, H. (2020). Intervención formativa y seguimientos observacionales con directivos de un hospital en México. Rev. Psicol. Cien. Comport. 11, 19–38. doi: 10.29059/rpcc.20201215-115

Carter, B. (2002). Chronic pain in childhood and the medical encounter: professional ventriloquism and hidden voices. Qual. Health Res. 12, 28–41. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200103

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cunliffe, A. L., and Locke, K. (2020). Working with differences in everyday interactions through anticipational fluidity: a hermeneutic perspective. Organ. Stud. 41, 1079–1099. doi: 10.1177/0170840619831035

Drew, P. (1992). “Contested evidence in court-room cross-examinations: the case of a trial for rape,” in Talk at Work, eds P. Drew and J. Heritage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 470–520.

Edwards, D. (1998). “The relevant thing about her: social identity categories in use,” in Identities in Talk, eds C. Antaki and S. Widdicombe (London: Sage), 15–33.

Engeström, Y. (2005). Developmental Work Research: Expanding Activity Theory in Practice. Berlin: Lehmanns Media.

Engeström, Y. (2011). From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory Psychol. 21, 598–628. doi: 10.1177/0959354311419252

Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., Virkkunen, J., Helle, M., Pihlaja, J., and Poikela, R. (1996). Change laboratory as a tool for transforming work. Lifelong Learn. Eur. 1, 10–17.

Fantasia, V., Zucchermaglio, C., Fatigante, M., and Alby, F. (2021). ‘We will take care of you’: identity categorisation markers in intercultural medical encounters. Discourse Stud. 23, 451–473. doi: 10.1177/14614456211009060

Hester, S., and Eglin, P. (eds). (1997). Studies in Membership Categorization Analysis. Lanham, MD: International Institute for Ethnomethodology and University Press of America.

Ivaldi, S., and Scaratti, G. (2020). Narrative and conversational manifestation of contradictions: social production of knowledge for expansive learning. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 25, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.11.002

Laitinen, A., Sannino, A., and Engeström, Y. (2016). From controlled experiments to formative interventions in studies of agency: methodological considerations. Educação 39, 14–23. doi: 10.15448/1981-2582.2016.s.24321

Montoro, C., and Brito, H. (2017). “Crossing cultures: a healthcare change laboratory intervention in Mexico [Full paper],” in Paper Presented at 33rd EGOS Colloquium, Copenhagen.

Muhlhausler, P., and Harré, R. (1990). Pronouns and People: The Linguistic Construction of Social and Personal Identity. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Pereira-Querol, M. A., Beltran, S. L., Montoro, C., Valenzuela, I., Castro, W., Tresserras, E., et al. (2019). Intervenciones formativas en educación y aprendizaje en el trabajo: aplicaciones del Laboratorio de Cambio en Iberoamérica. Rev. Int. Educ. Aprendizaje 7, 83–96. doi: 10.37467/gka-revedu.v7.1992

Sannino, A., and Engeström, Y. (2017). Co-generation of societally impactful knowledge in change laboratories. Manag. Learn. 48, 80–96. doi: 10.1177/1350507616671285

Stoppini, L., Scaratti, G., and Zucchermaglio, C. (2009). Autori di Ambienti Organizzativi. Roma: Carocci.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. London: Basil Blackwell.

Vilela, R. A. d. G., Pereira Querol, M. A., Beltran Hurtado, S. L., Cerveny, G. C. d. O., and Lopes, M. G. R. (2020). Collaborative Development for the Prevention of Occupational Accidents and Diseases. Change Laboratory in Workers’ Health. Cham: Springer.

Virkkunen, J., and Newnham, D. (2013). The Change Laboratory. A tool for Collaborative Development of Work Activities. Rotterdam: Sense publishers.

Vygotskij, L. S. (1934/1990). Pensiero e Linguaggio. Ricerche Psicologiche. A cura di Luciano Mecacci. Bari, Laterza, 1990. First edition: Myshlenie I rech’. Psihologicheskie Issledovanija. Moskvà-Leningrad: Gosu-darstvennoe social’no-èkonomicheskoe izdatel’stvo.

Widdicombe, S. (1998). “Identity as an analyst’s and a participant’s resource,” in Identities in Talk, eds C. Antaki and S. Widdicombe (London: Sage), 52–70.

Zucchermaglio, C. (2005). Who wins and who loses: the rethorical manipulation of social identities in a soccer team. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 9, 219–238. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.9.4.219

Keywords: social identity, formative intervention, collective pronouns, group membership categorization, rhetorical resources

Citation: Brito Rivera HA, Alby F and Zucchermaglio C (2021) Group Membership and Social Identities in a Formative Intervention in a Mexican Hospital. Front. Psychol. 12:786054. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.786054

Received: 29 September 2021; Accepted: 09 November 2021;

Published: 09 December 2021.

Edited by:

Massimiliano Barattucci, University of eCampus, ItalyReviewed by:

Giuseppe Scaratti, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyMare Koit, University of Tartu, Estonia

Copyright © 2021 Brito Rivera, Alby and Zucchermaglio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hugo Armando Brito Rivera, aHVnb2FybWFuZG8uYnJpdG9yaXZlcmFAZ21haWwuY29t

Hugo Armando Brito Rivera

Hugo Armando Brito Rivera Francesca Alby

Francesca Alby Cristina Zucchermaglio

Cristina Zucchermaglio