- Department of Psychology, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA, United States

The second wave of devastating consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to dramatic declines in well-being. While much of the well-being literature is based on descriptive and correlational studies, this paper evaluates a growing body of causal evidence from high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that test the efficacy of positive psychology interventions (PPIs). This systematic review analyzed the findings from 25 meta-analyses, 42 review papers, and the high-quality RCTs of PPIs designed to generate well-being that were included within those studies. Findings reveal PPIs have the potential to generate well-being even during a global pandemic, with larger effect sizes in non-Western countries. Four exemplar PPIs—that have been tested with a high-quality RCT, have positive effects on well-being, and could be implemented during a global pandemic—are presented and discussed. Future efforts to generate well-being can build on this causal evidence and emulate the most efficacious PPIs to be as effective as possible at generating well-being. However, the four exemplars were only tested in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic) countries but seem promising for implementation and evaluation in non-WEIRD contexts. This review highlights the overall need for more rigorous research on PPIs with more diverse populations and in non-WEIRD contexts to ensure equitable access to effective interventions that generate well-being for all.

Introduction

In response to psychology’s strong emphasis on pathology and repairing human deficits, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) provided a vision for the next generation of psychological scientists to spend at least some of their careers understanding the factors that make life worth living and preventing pathologies that arise when life is barren and meaningless. The call was answered and thousands of peer-reviewed articles on positive psychology topics have been published and more than a thousand of these articles included empirical tests of positive psychology theories, principles, and interventions (Donaldson et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018). Furthermore, this new science is now being conducted across many disciplines and professions, five continents, and more than 60 countries (Kim et al., 2018; Donaldson et al., 2020). It is hard to believe anyone could have imagined that two decades of rigorous peer-reviewed positive psychological science would become one of the key knowledge bases that could be used to generate well-being in the unprecedented global pandemic of 2020–2021.

“Follow the Science” is the cry being heard from public health scientists around the world as they try to stop the spread of COVID-19 by “flattening the curve.” It is the same cry that we hear with respect to finding treatments to reduce the severity and length of illness caused by the coronavirus, as well as developing effective vaccines. Scientists working on each of these public health challenges are using the best science they have available to prevent the spread of the virus, find effective treatments, and develop vaccines that can be taken to scale to alleviate the fear, trauma, and suffering occurring across the globe (National Institutes of Health, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020).

The second wave of devastating consequences of this global pandemic has been linked to dramatic declines in well-being (see Panchal et al., 2020). These undesirable consequences have affected marginalized and vulnerable groups disproportionately, increasing health and economic disparities around the world (United Nations, 2020). In the same way, public health scientists are following the most rigorous science available to combat the physical health impacts of the virus; it is also important to follow the most rigorous positive psychology intervention (PPI) science to design new PPIs that can be implemented during the pandemic to generate well-being across the globe (see Seligman, 2008; Donaldson et al., 2020). Just as equitable access to effective vaccines has been a major concern worldwide, it is also critical to ensure access and efficacy of PPIs beyond WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic) contexts to ensure that they generate well-being for all.

Present Study

The focus of this review is to identify the most promising PPIs for generating well-being by identifying and describing the most efficacious PPIs to date as determined by high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Like the health scientists designing RCTs to test the efficacy of treatments and vaccines to combat the coronavirus, we are using a conceptual version of the exemplar method (Bronk, 2012; Bronk et al., 2013) to intentionally identify the most efficacious PPIs when tested by the rigorous RCTs. The following sections will describe how we evaluated findings from reviews, meta-analyses, and peer-reviewed RCTs testing PPI efficacy in order to determine the most promising exemplar PPIs for generating well-being during the global pandemic. We hope the findings will help intervention researchers and practitioners around the world, including those in non-WEIRD contexts, to optimize the design and implementation of future PPIs.

Materials and Methods

The exemplar method is a research approach that involves focusing a study on a select sample that exemplifies the area of interest (Bronk, 2012; Bronk et al., 2013). In the spirit of positive psychology, researchers can study within the upper bounds of what is possible as opposed to limiting study to the averages of what is typical. For this reason, the method has been utilized in many previous positive psychology studies (e.g., Reimer et al., 2009; Dunlop et al., 2012; Reimer and Reimer, 2015; Morton et al., 2019). In this study, high-quality RCTs were chosen as exemplars from a larger pool of studies previously published in meta-analyses and review papers. The subsequent sections outline the search strategy, selection, and coding processes. Refer to Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the exemplar process utilized for this study.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted for meta-analyses and review papers in the following five databases: Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, PubMed, and Scopus, covering the period from 1998 (the start of the positive psychology movement) to 2020. The last run was conducted on June 3, 2021. In addition, a hand search was conducted through the websites of three non-Western journals in the field of positive psychology: the Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, the Iranian Journal of Positive Psychology, and the Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology.

Selection of High-Quality RCTs Testing PPIs

The present study focused its in-depth analysis on PPIs that were examined by RCTs that had undergone quality assessment by previous peer-reviewed meta-analyses and reviews. The 25 meta-analyses and 42 review articles were reviewed for the use of quality assessments (QA). Fifteen meta-analyses and nine review papers utilized some sort of QA, the most common of which was Cochrane’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias (Higgins et al., 2011). From eleven papers that used Cochrane’s, after removing two for calculating ratings differently from the others (Brown et al., 2019; Carrillo et al., 2019) and one that did not have studies meeting inclusion criteria (Macaskill and Pattison, 2016), we analyzed the QA ratings within the eight remaining papers (Bolier et al., 2013; Sutipan et al., 2016; Weiss et al., 2016; Chakhssi et al., 2018; Hendriks et al., 2018; Carr et al., 2020; Hendriks et al., 2020; Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020).

The studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) included in one of the aforementioned meta-analyses or review papers, (2) utilized some form of a Cochrane’s quality assessment rating, (3) RCTs using individual random assignment, (4) intervention described as a “PPI,” “positive psychological intervention,” a “positive intervention”, “positive psychotherapy”, “well-being intervention” or referred to their work in the context of “positive psychology” (in order to minimize bias by relying on an explicit, objective criterion for inclusion), (5) published in a peer-reviewed journal in the English language, and (6) intervention focused on improvement of psychological or mental well-being or any dimension based on any one of five major definitions: Subjective Well-being (SWB; Diener, 1984), the PERMA model of flourishing (PERMA; Seligman, 2011), Thriving (Su et al., 2014), Psychological Well-being (PWB; Ryff, 1989), and Quality of Life (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). As part of our exemplar approach, a variety of PPI types and features, samples, and well-being measures were included to ensure the sample was representative of the wide variety of PPI RCTs in the literature. We excluded: (1) cluster RCTs and quasi-experimental studies. (2) interventions that were not described as a PPI, positive psychological intervention, positive intervention, positive psychotherapy, well-being intervention, or referred to their work in the context of positive psychology (3) studies that solely measured as an outcome the reduction of depression, anxiety, or other negative emotions or states without a psychological well-being component as an outcome. (4) PPIs that solely changed behavior without a psychological well-being component as an outcome (e.g., physical activity, and cessation of smoking, etc.). (5) studies published in book chapters, dissertations, and grey literature, and (6) articles not published in the English language.

After removing duplicates and studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria, 23 high-quality studies were identified within the eight papers that met Cochrane’s high versus low or moderate-quality criteria (source of bias criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and anything else; Higgins et al., 2011). Of these 23 studies that were rated as high-quality, six were removed because they received different quality ratings from different papers. Out of the 17 remaining studies, 14 of the most promising trials of PPIs were identified where the PPI was found to improve at least one well-being outcome.

Coding of High-Quality RCT PPIs

Coding was conducted for: (1) year, (2) country of origin, (3) setting of intervention, (4) participants, (5) mention of PP, (6) PPI term used, (7) PPI description, (8) theory behind the intervention, (9) control group type, (10) time points assessed, (11) well-being measure, (12) other non-well-being measures, (13) well-being outcomes & effect sizes, (14) other non-well-being outcomes & effect sizes, (15), other findings, (16), the review or meta-analysis that assessed its quality, (17) applicable in the context of a global pandemic, (18) relevant for equity or marginalized groups heavily impacted by COVID-19, (19) relevant for vulnerable populations during a global pandemic, and (20) and each of the previously assessed quality assessments and quality ratings that used Cochrane’s.

Selection of Four Exemplar PPIs

Fourteen promising PPIs were further analyzed to find exemplar PPIs according to the following criteria: (1) improved well-being outcomes with medium to large effect sizes; (2) outcomes were attributed with confidence to the PPI; and (3) relevance in a global pandemic where the PPI could be delivered at scale and at a lower cost (e.g., online), could be delivered in social distancing conditions (e.g., delivered remotely via online or phone), and incorporated flexible delivery or content (e.g., participants choose their own content or time to complete it).

Results

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

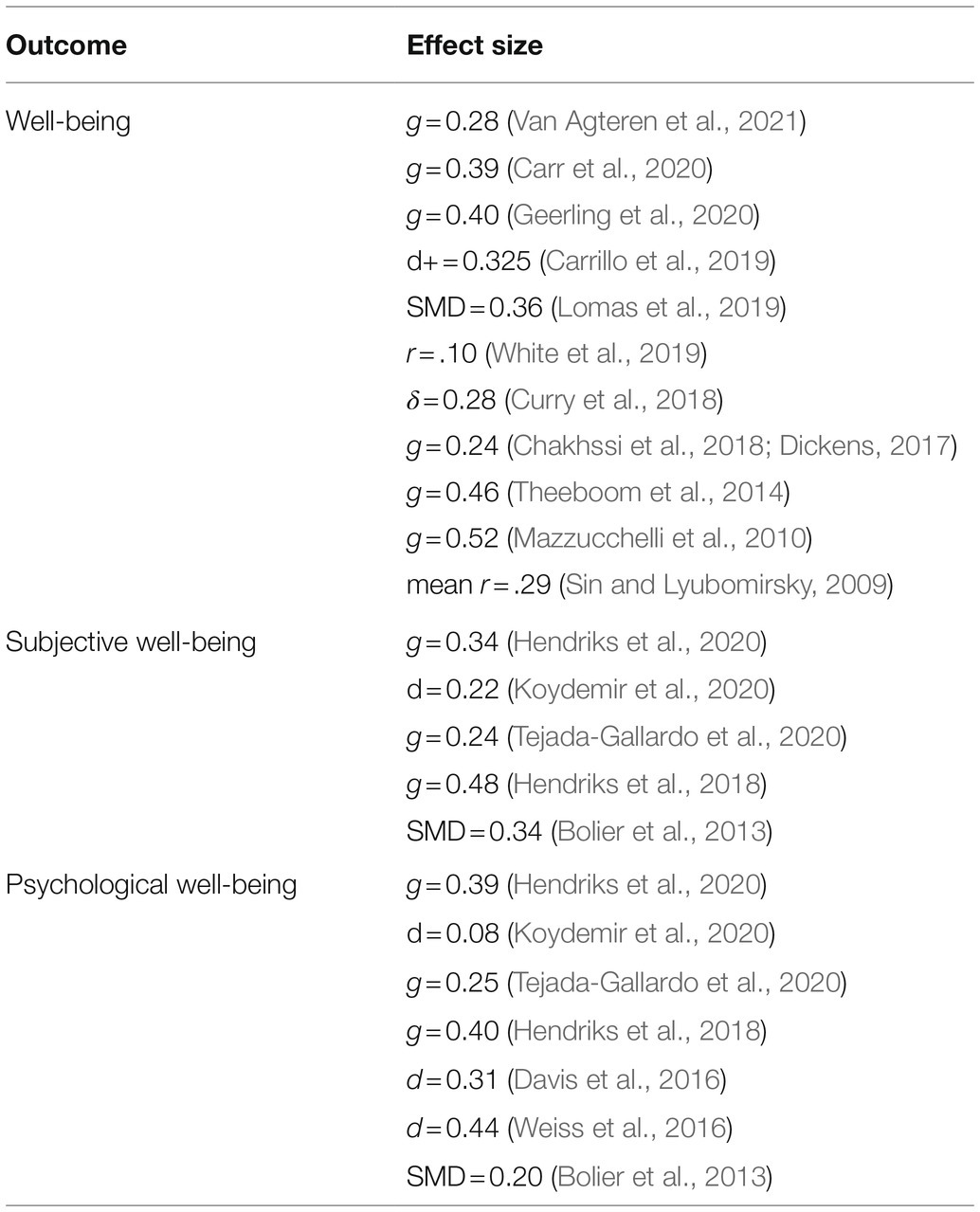

The science of PPIs has matured to the point where we now have numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses (see Table 1). There has also been a surge in recent studies testing PPIs (e.g., Biswas-Diener, 2020).

Well-Being Effect Sizes

Most of these reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs show that PPIs, on average, do have at least small to medium-sized positive effects on important outcomes, such as well-being (Table 2). By way of example, Van Agteren et al. (2021) and Hendriks et al. (2020) both examined the efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions (MPPIs). Van Agteren et al. (2021) found small to moderate effects on overall well-being for the general, mentally ill, and physically ill populations. Hendriks et al. (2020) concluded that MPPIs studies had an overall small effect on subjective well-being and depression, and a small to moderate effect on psychological well-being. In addition, they suggest MPPIs had an overall small to moderate effect on anxiety and a moderate effect on stress. Further, Donaldson et al. (2019a) published a meta-analysis of the most rigorous PPI studies conducted in the workplace. They found that the workplace interventions had small to moderate positive effects across both desirable and undesirable work outcomes (e.g., job stress), including well-being, engagement, leader-member exchange, organization-based self-esteem, workplace trust, forgiveness, prosocial behavior, leadership, and calling.

Table 2. Small to moderate well-being effect sizes in positive psychology intervention meta-analyses.

Moderators

These meta-analyses based on numerous empirical tests and thousands of participants illustrate the conditions under which PPIs can generate well-being and positive human functioning. Many moderators were tested and found to impact effect size. Each of these meta-analyses focused on different types of PPIs with differing study designs, which explains some variability in findings.

Some features of the PPIs were found to be moderators that impacted effect sizes, including the program format, program type, and duration, but not frequency. The program format showed that individualized interventions led to greater effects than self-help or group (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Weiss et al., 2016; Carr et al., 2020). The program type findings were mixed with Carr et al. (2020) demonstrating that multi-component PPIs showed greater effects than single component PPIs, but Hendriks et al. (2018) showed no effect for this moderator. The impacts of duration were also mixed with Carr et al. (2020), Koydemir et al. (2020), and Sin and Lyubomirsky (2009) finding that longer interventions led to greater effects, but Carrillo et al. (2019) found the opposite and Davis et al. (2016), Geerling et al. (2020), Hendriks et al. (2018), and Slemp et al. (2019) not finding this effect. Frequency was only tested by Slemp et al. (2019) study of contemplative interventions and was not found to be a moderator.

Features of the participants were also found to be moderators, including age, gender, and clinical status. Many meta-analyses found age to be a moderator, with older participants showing a larger effect size than younger participants (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Dickens, 2017; Curry et al., 2018; Carrillo et al., 2019; Carr et al., 2020). However, Weiss et al. (2016) did not report this finding. Gender was a moderator in one meta-analysis with women showing greater effects (Lomas et al., 2019) but was not found to be a moderator by Curry et al. (2018) or Dickens (2017). Meta-analyses that compared clinical participants to non-clinical participants found that clinical participants demonstrated greater effects (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Weiss et al., 2016; Carr et al., 2020). However, Hendriks et al. (2018) did not replicate this finding.

Features of the study were also moderators, including country of study, study quality, and control group type, in that non-Western countries, lower-quality studies, and those that used no intervention as a comparison group tended to report higher effect sizes. Hendriks et al. (2018) found that PPIs from non-Western countries tend to report larger effect sizes than those from Western countries with the caveat that these studies tend to have lower study quality. Supporting these findings, Carr et al. (2020) and Hendriks et al. (2020) both found country as a moderator of well-being, with individuals in non-WEIRD countries showing greater effects than those in WEIRD countries (Henrich et al., 2010). However, both meta-analyses rated few non-WEIRD studies as good or high-quality according to their quality assessments: 5 out of 64 non-WEIRD studies in Carr et al. (2020) and 1 out of 13 non-WEIRD studies in Hendriks et al. (2020). Across the two meta-analyses, only 19.35% of studies took place in non-WEIRD countries; 48.05% of non-WEIRD studies were rated poor quality, 44.16% of non-WEIRD studies were rated fair/moderate quality, and only 7.79% of non-WEIRD studies were rated good/high quality. Beyond country distinctions, lower-quality RCTs often overestimated the effects of PPIs (e.g., Carr et al., 2020; Hendriks et al., 2020; Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020). However, this finding was not found by Slemp et al. (2019). As further indication of study quality, the type of control group was also found to be a moderator where studies that used no intervention as a comparison group led to greater effects than those that used an alternative/active intervention; plus, those that used a placebo led to greater effects than those that used a waitlist design (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Dickens, 2017; Curry et al., 2018; Carrillo et al., 2019; Slemp et al., 2019; Carr et al., 2020; Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020). However, these control group findings were not replicated by all meta-analyses (Weiss et al., 2016; Dickens, 2017; Curry et al., 2018; Hendriks et al., 2018). Lastly, the study recruitment method showed mixed results with Carr et al. (2020) finding that those with participants who were referred to the study had greater effects than those with participants who self-selected into it, yet Sin and Lyubomirsky (2009) found the opposite.

Small Sample Bias

One criticism of some of these meta-analyses is that they are limited by small sample bias. For example, White et al. (2019) reanalyzed two highly cited meta-analyses (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Bolier et al., 2013) and corrected their findings for small sample size bias. While the effect sizes of PPIs on well-being were smaller (approximately r = 0.10) after the adjustment, both meta-analyses still demonstrated a statistically significant improvement of well-being (White et al., 2019).

Exemplar PPIs

The fourteen promising PPIs identified by this review based on the highest-quality RCTs were all conducted in WEIRD countries. Overall, there were fewer studies from non-WEIRD countries in the sample analyzed for this review and they were of moderate or low quality so were not included in the most promising PPIs. Out of the highest-quality interventions, four exemplars were identified as the most promising PPIs for generating well-being in a global pandemic (see Table 3). All of the Four Most Promising PPIs were conducted with adult samples. Three of the promising PPIs used samples relevant to vulnerable populations during a pandemic: individuals with low to moderate well-being (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2017) mild to moderate depression (Ivtzan et al., 2016), and stressed employees (Feicht et al., 2013).

The four exemplar PPIs are all MPPIs that focus on training, improved well-being with medium to large effect sizes, and can be feasibly implemented during a global pandemic and beyond. The most popular topics were strengths, gratitude, positive relationships, positive emotions, and mindfulness. A variety of measures were used to measure well-being. This variety reflects the lack of consensus on a universal definition of well-being in the positive psychology literature (Diener et al., 2018), which can make it challenging to compare the impact of different interventions. In addition to increasing well-being, three of the PPIs were also effective at reducing negative outcomes, such as perceived stress, depression, and anxiety (Table 3). In terms of training design and content, all of the PPIs are long (ranging from four to 12 weeks) with weekly modules that focus on one topic per week. The Promising PPI topics and exercises can be viewed in Table 4. However, it should be noted that while the four exemplar PPIs share commonalities that can help inform future PPI design, there were also differences in theories, features, and duration.

Although all four exemplar studies were among the highest-quality RCTs in our sample, there were some methodological limitations present. All four studies used samples that were subject to self-selection bias and consisted of mostly educated females. All four RCTs also used waitlist control groups, which can create expectation effects, and all experienced participation attrition. In addition, all four studies used self-report measures although one study (Feicht et al., 2013) also used objective measures. Finally, long-term follow-up measurement was lacking with the longest follow-up measurement at 12 months (see Table 3).

Experimental evidence of the highest quality suggests these PPIs may be promising exemplars for future intervention design during the global pandemic and beyond, and seem promising for future implementation and evaluation in non-WEIRD contexts. However, it is important to emphasize that future PPIs guided by the findings of these exemplars should also be tested in a rigorous manner to make sure they are also efficacious and effective for more diverse populations in need, including populations in non-WEIRD countries. We acknowledge although we have identified some of the most valid causal evidence available for generating well-being with PPIs, the samples used in the most rigorous studies were not as diverse as we would have liked to be confident these PPIs will naturally generalize to different populations and non-WEIRD contexts. Nevertheless, we have identified the most promising causal evidence for guiding the design of PPIs for non-WEIRD countries, with appropriated adaptations to fit the specific context.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to review existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses and identify the most promising PPIs for generating well-being based on the most rigorous experimental evidence available in the peer-reviewed literature. Four exemplar PPIs were identified from these meta-analyses, all of which were MPPIs in the form of self-administered training that can be administered to teach a variety of positive psychology topics and skills over the course of multiple weeks that participants can use to improve their well-being.

Implications and Recommendations

The findings of meta-analyses as well as the most promising PPIs identified by this review provide a base of scientific evidence to inform the future design of PPIs for generating well-being in both pandemic and non-pandemic times. A major advantage of examining the distributions of PPI effects across many rigorous RCTs is that it provides a good sense of what one might expect when designing or replicating a PPI to generate well-being. It also provides some conditions of the format and study design that may bolster or diminish effects. Although using a no-intervention or placebo control group and having a lower-quality study may lead to greater effects, these are not the type of takeaways we hope designers replicate. Instead, we hope these findings underscore the importance of designing a high-quality PPI so as to achieve effects even with a strong active comparison group and high-quality study design.

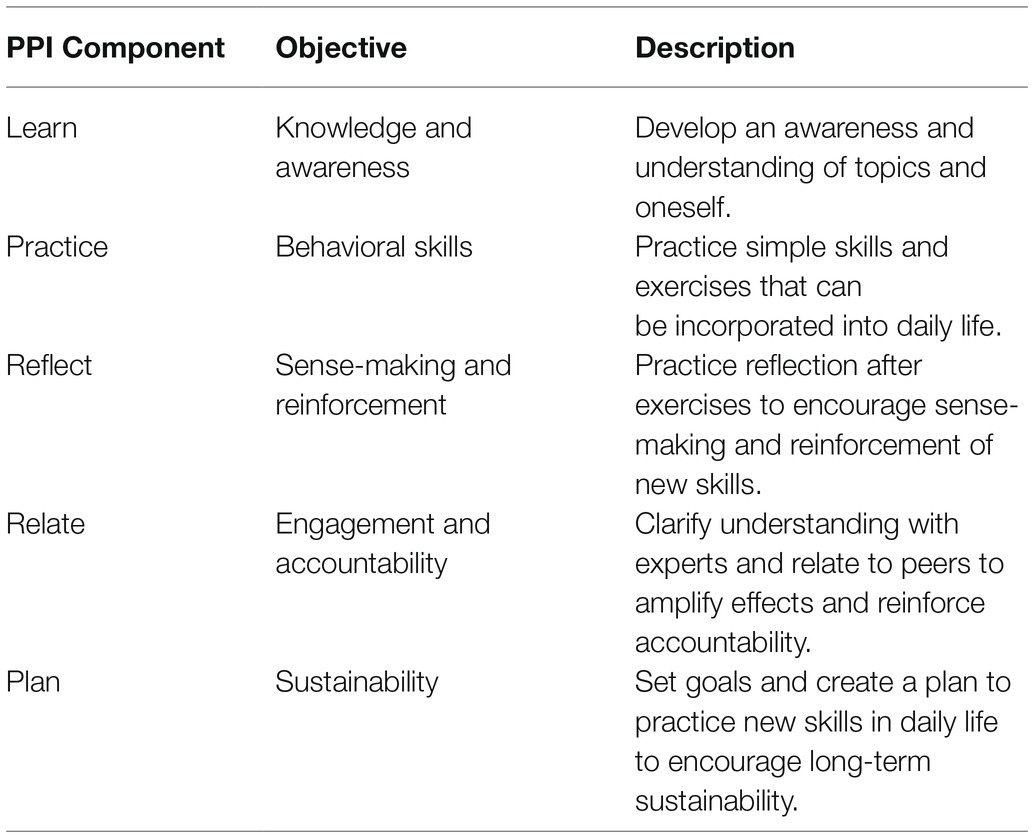

Looking at specifics of design by “following the science,” MPPIs can be administered as a training to help people improve their own well-being by giving them knowledge and skills that will support them in daily life. The most promising PPIs we found illustrated that providing opportunities to learn, practice, reflect, relate, and plan can help ensure effectiveness (see Table 5 for a detailed description).

When designing a training, a variety of topics, exercises, and skills based on the science of positive psychology and MPPIs can be provided to target multiple dimensions of well-being, both hedonic and eudaimonic. Since MPPIs can also decrease stress, depression, and anxiety (Hendriks et al., 2020), the reduction of these symptoms can also be targeted to help people who may be struggling with these symptoms during the pandemic. A design that incorporates mutually reinforcing activities can also amplify positive effects (Rusk et al., 2018). For example, incorporating the practice of mindfulness can enhance and sustain the positive benefits of positive psychology training (Ivtzan et al., 2016).

Successful interventions appear to be informed by scientific evidence and are tailored to fit the specific needs and contexts of participants (Donaldson and Chen, 2021). The most promising PPIs identified by this review can provide ideas for designing a curriculum (see Tables 3–5) and PPI meta-analyses point to theories and activities that have been shown to improve well-being across many studies (see Table 1), such as practicing gratitude (Davis et al., 2016; Dickens, 2017), kindness (Curry et al., 2018), mindfulness (Lomas et al., 2019; Slemp et al., 2019), and best possible self (Carrillo et al., 2019), as well as job crafting, strengths, and PsyCap in the workplace (Donaldson et al., 2019a). The curriculum of these interventions can be adapted to fit the needs and contexts of participants, including those from non-WEIRD countries.

Other aspects of intervention design can also be tailored to suit participants’ needs and contexts. Flexibility can encourage adherence and help meet a variety of participant needs and motivations across different contexts. Participants can choose where and when they complete the modules based on their schedule or tailor their learning by choosing the topics or activities that resonate with them. Longer PPIs have been found to be more effective than shorter ones (Koydemir et al., 2020), yet a large amount of time does not need to be devoted to activities to be effective as demonstrated by the four most promising PPIs. Providing flexibility can be helpful for people with heavy workloads, like frontline and essential workers, or parents who are working from home while balancing childcare responsibilities. Similarly, giving individuals the opportunity to self-select by engaging in activities that are more intrinsically motivating or well-suited can amplify the positive effects (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Lyubomirsky and Layous, 2013). Providing reminders and opportunities to check progress can also be added to further encourage adherence and engagement.

Within the context of a global pandemic, the delivery mode of PPIs is an important consideration. For example, face-to-face interactions may no longer be as feasible to implement in a pandemic-impacted world. Online PPIs, particularly automated online self-help interventions, can be used while social distancing and implemented cost-effectively on a larger scale than face-to-face interventions (Muñoz, 2010). Although individualized interventions tended to show greater effects than self-help or group interventions across meta-analyses (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Weiss et al., 2016; Carr et al., 2020), three out of four of the most promising PPIs were online and were all self-administered with success. Some research has found many searching for well-being programs tend to be inclined to seek online PPIs (Parks et al., 2012, p. 1). A combination of automated content supplemented by live expert or peer support can also be considered. Although online interventions can reach more people, it is important to recognize that a “global digital divide” exists where access to technology is a barrier for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Pick and Azari, 2008, p. 1). Therefore, in non-WEIRD countries that may have larger populations from lower socio-economic backgrounds, alternative modes of delivery can be considered to make PPIs accessible to those who lack adequate access to technology and the Internet. Physical self-help lessons or workbooks can be used and supplemented by additional guidance and support via email (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2017). These materials can be mailed to meet social distancing guidelines and if participants do not have access to email, support can be provided via telephone.

Finally, we recognize that a multi-week training will not be feasible for everyone, especially those heavily impacted by the pandemic. The science of positive psychology also points to several effective smaller-dose mono-PPIs that can be used by anyone at any time. For those lacking time and resources, our recommendations based on the most promising PPIs and PPI meta-analyses provide simple yet effective exercises that anyone can try.

Strengths and Limitations

This review makes several contributions to the positive psychology literature. First, we focused on the most rigorous research of PPIs, in the form of high-quality RCTs, using some of the most valid causal evidence available to identify the most promising PPIs for generating well-being. Second, this is the first systematic review of PPIs that makes use of the exemplar method. The exemplar approach is naturally aligned with the spirit of positive psychology, identifying exemplars in the upper bounds of what is possible as opposed to being limited by what is typical. We hope this unique approach can also serve as a model for future reviews in this field. Third, we believe this review will serve as an especially useful resource for practitioners since it provides practical, evidence-based recommendations for designing effective PPIs that will generate well-being.

There are also several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there are no clearly defined universal criteria for what constitutes an exemplar (Bronk, 2012). We defined our own criteria to identify exemplary PPIs, but there may be other approaches that could be further explored with the longer-term goal of achieving consensus on what constitutes exemplarity among PPIs that target well-being and the RCTs that test their efficacy. Furthermore, it should be noted that how exemplarity is defined in a study will also influence results (Bronk, 2012). Second, our inclusion criteria were limited to RCTs while inclusive of all PPI types and features, samples, well-being measures, and well-being theories. RCTs test efficacy under highly controlled conditions, but more research is needed to draw conclusions about effectiveness in real-world settings. The variability in our sample also means that the PPIs, RCTs, and effect sizes we looked at are not perfectly comparable. Therefore, further research is needed to confirm generalizability and replicability of our findings. Future reviews of PPI studies can also explore the use of narrower inclusion criteria and more homogenous samples to confirm efficacy. Future research is needed to further test the effectiveness of the most promising PPIs and our recommendations for designing PPIs in real-world settings, including different contexts and with different populations. Finally, the samples used to test the most promising PPIs were from WEIRD countries and were mostly White and female, demonstrating a need for rigorous scientific PPI studies to use more diverse samples that include more non-WEIRD countries. None of the four exemplars came from non-WEIRD countries since there were fewer non-WEIRD studies to include and more non-WEIRD studies were rated lower-quality, even though they showed greater effect sizes in meta-analyses (Hendriks et al., 2018, 2020; Carr et al., 2020).

The Importance of DEI for the Future of PPI Science

Our findings are consistent with previous research that found that the majority of RCTs on PPIs were conducted in WEIRD countries on samples that were mostly highly educated with a higher income (Hendriks et al., 2019). Among the RCTs identified in this review, there was also no mention of diversity, equity, or inclusion in the titles or abstracts of these papers. Positive psychology has been criticized for not attending much to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Rao and Donaldson (2015) found that although women are overrepresented as participants in empirical studies, they are underrepresented as first authors, and discussions of issues relevant to women and gender are relatively scarce. Further, empirical research studies conducted across the world are based largely on White samples, and there is little research focused on race and ethnicity or individuals at the intersections of gender, race, and ethnicity. Rao and Donaldson (2015) suggested pathways for addressing these deficits and encouraged future positive psychology researchers to seek a better understanding of DEI issues related to positive psychology. Harrell (2018) and Pedrotti and Edwards (2017) extended this seminal DEI work and provided additional frameworks for understanding positive psychology concepts and interventions in cultural context, with diverse and marginalized groups, and with a focus on collective well-being. Warren et al. (2019) provided a detailed conceptual map for navigating and planning future research on well-being and flourishing through positive diversity and inclusion behaviors and practices. These prior efforts to encourage more emphasis on DEI are useful guides for adapting the most efficacious PPIs we found in this paper to meet the specific needs of the marginalized and vulnerable populations. But we would also like to point out that we cannot assume that the promising PPIs we have identified will necessarily have the same effects. Future efforts to examine PPIs in diverse, marginalized, vulnerable populations, and in non-WEIRD contexts are sorely needed to better understand how to reduce disparities and generate well-being for all (Bolier et al., 2013; Curry et al., 2018; Hendriks et al., 2018).

Conclusion

We followed the positive psychology intervention science and discovered that the most rigorously tested PPIs clearly suggest how we might generate well-being in global pandemic and non-pandemic times. These experimental findings provide us with causal evidence that medium and longer-term well-being outcomes can be achieved with PPIs. It has also revealed the conditions under which PPIs are most likely to be effective and underscored the importance of conducting more rigorous PPI research in non-WEIRD contexts and designing the next generation of PPIs to better serve diverse, marginalized, and the underserved populations who are most likely to be the most negatively affected by a global pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank colleague Mashi Rahmani, Ph.D. for his support of this project, and for his continuous financial support of our flourishing and social justice research program.

References

Biswas-Diener, R. (2020). The practice of positive psychology coaching. J. Positive Psychol. 15, 701–704. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1789705

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G., Riper, H., Smit, F., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Bronk, K. C. (2012). The exemplar methodology: An approach to studying the leading edge of development. Psychol. Well-Being Theor. Res. Pract. 2:5. doi: 10.1186/2211-1522-2-5

Bronk, K. C., King, P. E., and Matsuba, M. K. (2013). An introduction to exemplar research: A definition, rationale, and conceptual issues. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2013:20045. doi: 10.1002/cad.20045

Brown, L., Ospina, J. P., Celano, C. M., and Huffman, J. C. (2019). The effects of positive psychological interventions on medical patients’ anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 81, 595–602. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000722

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

Carrillo, A., Rubio-Aparicio, M., Molinari, G., Enrique, Á., Sánchez-Meca, J., and Baños, R. M. (2019). Effects of the best possible self intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 14:e0222386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222386

Chakhssi, F., Kraiss, J. T., Sommers-Spijkerman, M., and Bohlmeijjer, E. T. (2018). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being in clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC 18:211. doi: 10.1186/s12888018-1739-2

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. England: Routledge Academic.

Curry, O. S., Rowland, L. A., Van Lissa, C. J., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J., and Whitehouse, H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 76, 320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2018.02.014

Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., et al. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. J. Couns. Psychol. 63, 20–31. doi: 10.1037/cou0000107

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The 'what' and 'why' of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Dhillon, A., Sparkes, E., and Duarte, R. V. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness 8, 1421–1437. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0726-x

Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 39, 193–208. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., and Oishi, S. (2018). Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra. Psychology 4:15. doi: 10.1525/collabra.115

Donaldson, S. I., and Chen, C. (2021). Positive Organizational Psychology Interventions: Design & Evaluation. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Donaldson, S. I., Csikszentmihalyi, M., and Nakamura, J. (2020). Positive Psychological Science: Improving Everyday Life, Well-Being, Work, Education, and Societies across the Globe. New York: Routledge.

Donaldson, S. I., Dollwet, M., and Rao, M. A. (2015). Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 10, 185–195. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.943801

Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., and Donaldson, S. I. (2019a). Evaluating positive psychology interventions at work: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inter. J. Appl. Positive Psychol. 4, 113–134. doi: 10.1007/s41042-019-00021-8

Drozd, F., Mork, L., Nielsen, B., Raeder, S., and Bjørkli, C. A. (2014). Better days—A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based positive psychology intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 377–388. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.910822

Dunlop, W. L., Walker, L. J., and Matsuba, M. K. (2012). The distinctive moral personality of care exemplars. J. Posit. Psychol. 7, 131–143. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2012.662994

Feicht, T., Wittmann, M., Jose, G., Mock, A., von Hirschhausen, E., and Esch, T. (2013). Evaluation of a seven-week web-based happiness training to improve psychological well-being, reduce stress, and enhance mindfulness and flourishing: A randomized controlled occupational health study. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2013/676953

Geerling, B., Kraiss, J. T., Kelders, S. M., Stevens, A. W. M. M., Kupka, R. W., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and psychopathology in patients with severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 15, 572–587. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1789695

Harrell, S. P. (2018). ‘Being human together’: positive relationships in the context of diversity, culture, and collective well-being,” in Toward a positive psychology of relationships: new directions in theory and research. eds. Warren, M. A., and Donaldson, S. I. (California: ABC-CLIO), 247–284.

Heekerens, J. B., and Eid, M. (2020). Inducing positive affect and positive future expectations using the best-possible-self intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 16, 322–347. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1716052

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E. T., and de Jong, J. (2018). The efficacy of non-Western positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Inter. J. Well. 8, 71–98. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v8i1.711

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Jong, J., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2020). The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Happiness Stud. Interdisciplin. Forum Subject. Well-Being 21, 357–390. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1

Hendriks, T., Warren, M. A., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E. T., et al. (2019). How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 14, 489–501. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., and Norenzayan, A. (2010). Beyond WEIRD: towards a broad based behavioral science. Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 111–135. doi: 10.1017/S0140525x10000725

Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., et al. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

Howell, A. J., and Passmore, H.-A. (2019). Acceptance and commitment training (ACT) as a positive psychological intervention: A systematic review and initial meta-analysis regarding ACT’s role in well-being promotion Among university students. J. Happiness Stud. 20, 1995–2010. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-0027-7

Ivtzan, I., Young, T., Martman, J., Jeffrey, A., Lomas, T., Hart, R., et al. (2016). Integrating mindfulness into positive psychology: A randomised controlled trial of an online positive mindfulness program. Mindfulness 7, 1396–1407. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0581-1

Kim, H., Doiron, K., Warren, M., and Donaldson, S. (2018). The international landscape of positive psychology research: A systematic review. Inter. J. Well. 8, 50–70. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v8i1.651

Koydemir, S., Sökmez, A. B., and Schütz, A. (2020). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of randomized controlled positive psychological interventions on subjective and psychological well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 16, 1145–1185. doi: 10.1007/s11482-019-09788-z

Lomas, T., Medina, J. C., Ivtzan, I., Rupprecht, S., and Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. (2019). Mindfulness-based interventions in the workplace: An inclusive systematic review and meta-analysis of their impact upon wellbeing. J. Posit. Psychol. 14, 625–640. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1519588

Lyubomirsky, S., and Layous, K. (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 57–62. doi: 10.1177/0963721412469809

Macaskill, A., and Pattison, H. (2016). Review of positive psychology applications in clinical medical populations. Healthcare 4:66. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030066

Mazzucchelli, T. G., Kane, R. T., and Rees, C. S. (2010). Behavioral activation interventions for well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 5, 105–121. doi: 10.1080/17439760903569154

Morton, E., Colby, A., Bundick, M., and Remington, K. (2019). Hiding in plain sight: older U.S. purpose exemplars. J. Posit. Psychol. 14, 614–624. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1510022

Muñoz, R. F. (2010). Using evidence-based internet interventions to reduce health disparities worldwide. J. Med. Internet Res. 12:e60. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1463

National Institutes of Health (2020). Federally funded clinical studies related to Covid-19. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=COVID-19 (Accessed August 3, 2020).

Neff, K. D., and Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J. Clin. Psychol. 69, 28–44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21923

Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Ogera, K., Cox, C., Garfield, R., Hamil, L., et al. (2020). The implications of Covid-19 for mental health and substance abuse. Available at: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/ (Accessed April 21, 2020).

Parks, A. C., Della Porta, M. D., Pierce, R. S., Zilca, R., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). Pursuing happiness in everyday life: The characteristics and behaviors of online happiness seekers. Emotion 12, 1222–1234. doi: 10.1037/a0028587

Pedrotti, J. T., and Edwards, L. M. (2017). “Cultural context in positive psychology: History, research, and opportunities for growth” in Scientific Advances in Positive Psychology. eds. Warren, M. A., and Donaldson, S. I. (California: ABC-CLIO), 257–288.

Pick, J. B., and Azari, R. (2008). Global digital divide: influence of socioeconomic, governmental, and accessibility factors on information technology. Inf. Technol. Dev. 14, 91–115. doi: 10.1002/itdj.20095

Rao, M. A., and Donaldson, S. I. (2015). Expanding opportunities for diversity in positive psychology: An examination of gender, race, and ethnicity. Can. Psychol. 56, 271–282. doi: 10.1037/cap0000036

Reimer, K. S., Goudelock, B. M. D., and Walker, L. J. (2009). Developing conceptions of moral maturity: traits and identity in adolescent personality. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 372–388. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992431

Reimer, L. C., and Reimer, K. S. (2015). Maturity is coherent: structural and content-specific coherence in adolescent moral identity. J. Posit. Psychol. 10, 543–552. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015159

Rusk, R. D., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., and Waters, L. (2018). A complex dynamic systems approach to lasting positive change: The synergistic change model. J. Posit. Psychol. 13, 406–418. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2017.1291853

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C. H., Pieterse, M. E., Boon, B., Walburg, J. A., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). An early intervention to promote well-being and flourishing and reduce anxiety and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 9, 15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.04.002

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C. H., Pieterse, M. E., Walburg, J. A., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2015). Efficacy of a multicomponent positive psychology self-help intervention: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR 4:e105. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4162

Seligman, M. E. (2008). Positive health. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 57, 3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00351.x

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, M. E., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. American Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Seligman, M. E. P., Rashid, T., and Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. Am. Psychol 61, 774–788. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774

Sin, N., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 65, 467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593

Slemp, G. R., Jach, H. K., Chia, A., Loton, D. J., and Kern, M. L. (2019). Contemplative interventions and employee distress: A meta-analysis. Stress Health J. Inter. Society Invest. Stress 35, 227–255. doi: 10.1002/smi.2857

Su, R., Tay, L., and Diener, E. (2014). The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) and the brief inventory of thriving (BIT). Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 6, 251–279. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12027

Sutipan, P., Intarakamhang, U., and Macaskill, A. (2016). The impact of positive psychological interventions on wellbeing in healthy elderly people. J. Happiness Stud. 18, 269–291. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9711-z

Tejada-Gallardo, C., Blasco-Belled, A., Torrelles-Nadal, C., and Alsinet, C. (2020). Effects of school-based multicomponent positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1943–1960. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01289-9

Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., and van Vianen, A. E. M. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

United Nations. (2020) Impacts of COVID-19 disproportionately affect poor and vulnerable: UN chief. Available at: United Nations website. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/06/1067502 (Accessed June 30, 2020).

Van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Lo, L., Bartholomaeus, J., Kopsaftis, Z., Carey, M., et al. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 631–652. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01093-w

Warren, M. A., Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., and Donaldson, S. I. (2019). Reinvigorating research on gender in the workplace using a positive work and organizations perspective. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 21, 498–518. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12206

Weiss, L. A., Westerhof, G. J., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Can we increase psychological well-being? The effects of interventions on psychological well-being: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 11:e0158092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158092

White, C. A., Uttl, B., and Holder, M. D. (2019). Meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions: The effects are much smaller than previously reported. PLoS One 14:e0216588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216588

World Health Organization (2020). COVID-19 studies from the World Health Organization database. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/who_table

Keywords: positive psychology intervention, well-being, randomized controlled trial, systematic review, exemplar method

Citation: Donaldson SI, Cabrera V and Gaffaney J (2021) Following the Science to Generate Well-Being: Using the Highest-Quality Experimental Evidence to Design Interventions. Front. Psychol. 12:739352. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.739352

Edited by:

Llewellyn Ellardus Van Zyl, North West University, South AfricaReviewed by:

Ernst Bohlmeijer, University of Twente, NetherlandsChiara Ruini, University of Bologna, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Donaldson, Cabrera and Gaffaney. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stewart I. Donaldson, stewart.donaldson@cgu.edu

Stewart I. Donaldson

Stewart I. Donaldson Victoria Cabrera

Victoria Cabrera Jaclyn Gaffaney

Jaclyn Gaffaney