- 1Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Research Group School Psychology and Development in Context KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 2Research Foundation Flanders, Brussels, Belgium

- 3Research Group Care Ethics, University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht, Netherlands

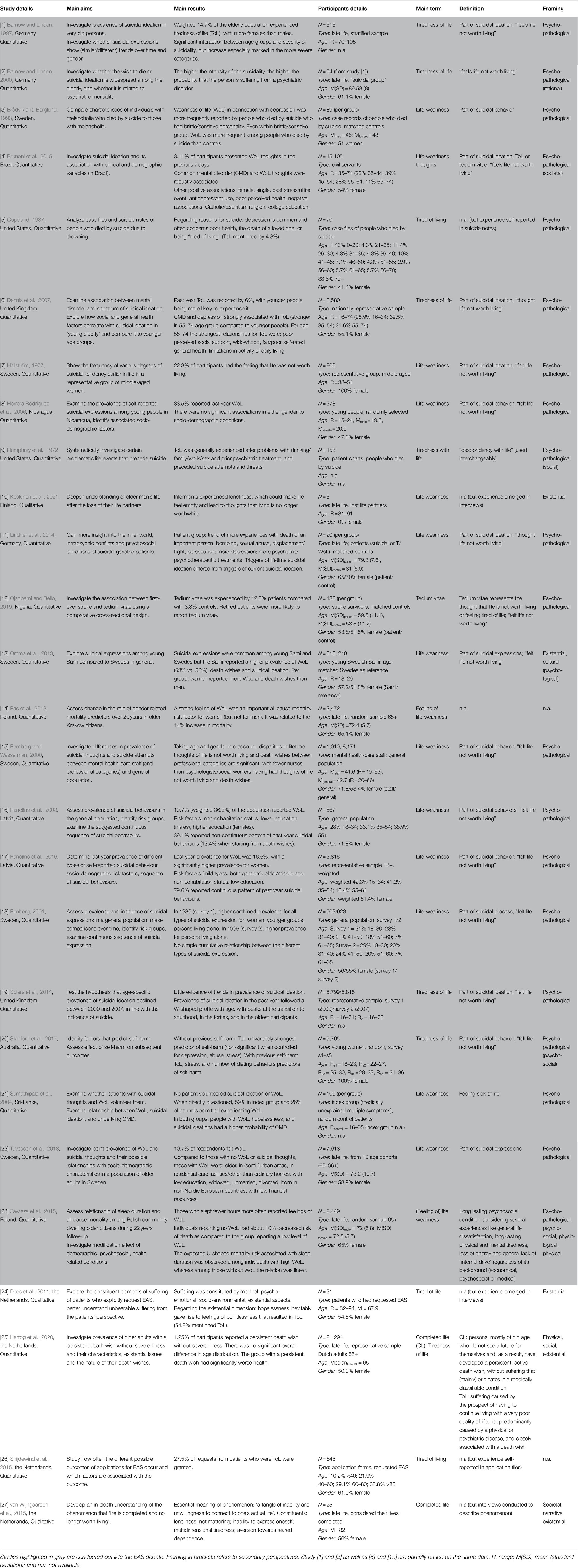

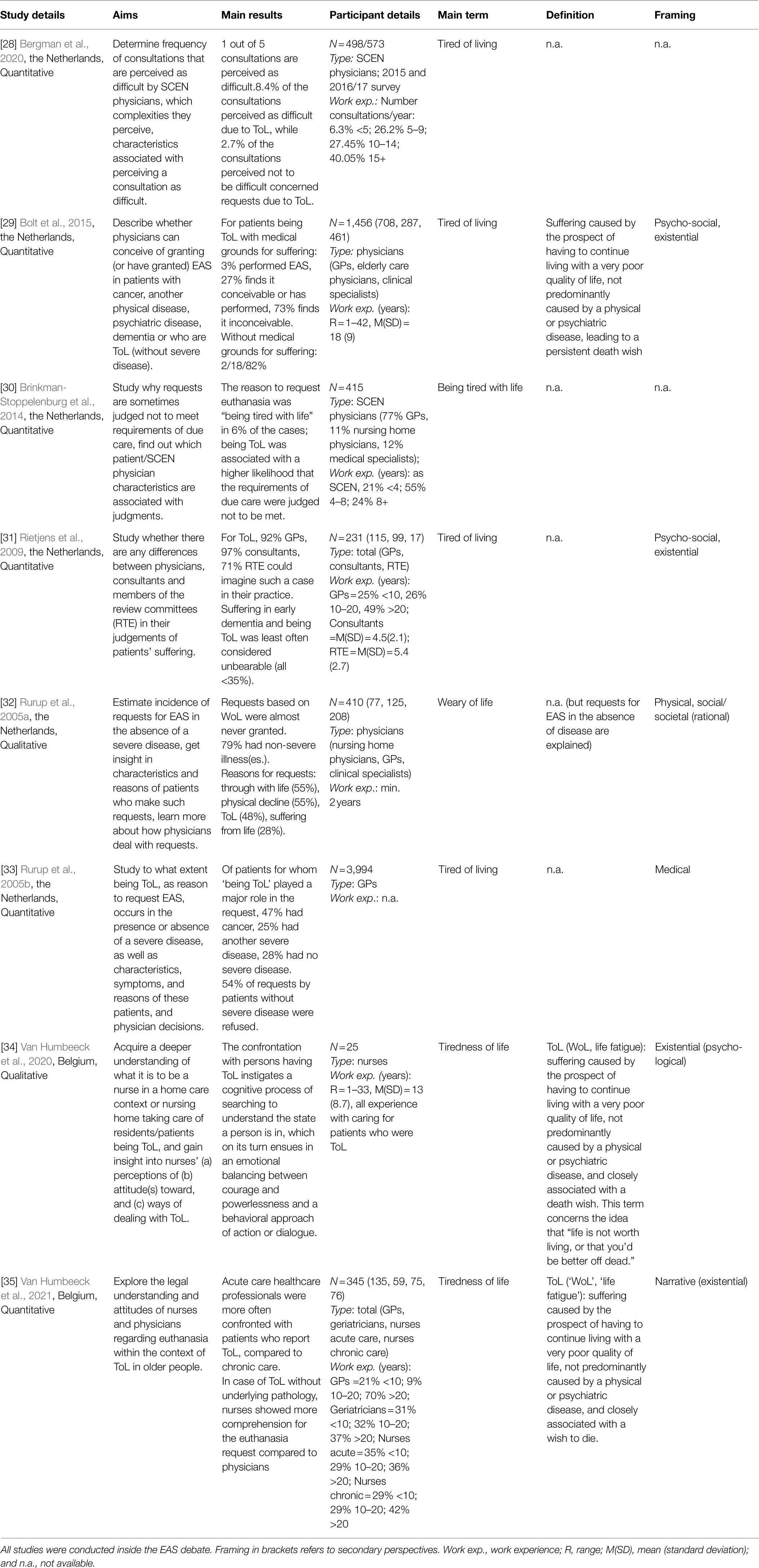

In the Netherlands and in Belgium, a political debate emerged regarding the possibility of euthanasia and assisted suicide (EAS) for older adults who experience their lives as completed and no longer worth living, despite being relatively healthy. This mini-review aimed to (1) present an overview of the terms used to denote this phenomenon as well as their definitions and to (2) explore how the underlying experiences are interpreted by the study authors. A systematic search was performed in Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL, yielding 35 articles meeting the selection criteria. We selected empirical, English-language articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Participants had to have a first-person experience of the phenomenon or be assessed for it, or have a third-person experience of the phenomenon. Results show that the terms tiredness of life (ToL) and weariness of life (WoL) were used most frequently, also in the broader literature on suicidal expressions across the life span. Many studies mentioned operational definitions or synonyms rather than theoretical definitions. Moreover, inside the EAS debate, the term ToL was more common, its definition incorporated death wishes, and it was regularly framed existentially. Outside of this debate, the phenomenon was generally considered as a part of suicidal ideation distinct from death wishes, and its experience was often associated with underlying psychopathology. We discuss the need to establish consensus definitions and conclude that only a multidimensional view may be suitable to capture the complex nature of the phenomenon.

Introduction

Old age is associated with numerous losses, such as of cognitive and physical abilities and social ties. Still, the majority of older adults maintains high levels of life satisfaction up to an advanced age (Gana et al., 2013), with reductions in wellbeing usually only being observed in the very last phase of life (i.e., terminal decline; Gerstorf et al., 2008). A number of older adults, however, appear to cope less well with the challenges of late life and start to lack a sense of meaning. They develop the feeling that their life is not worth living anymore, sometimes reporting an associated death wish. These experiences also seem to develop in the absence of severe physical and mental disorders (van Wijngaarden et al., 2015; Van Humbeeck et al., 2020).

Research into this phenomenon is still an emerging area. Different terms, such as completed life, tiredness of life (ToL), or life fatigue, have been used to denote the phenomenon, but the terms lack agreed-upon definitions as well an integration with other research areas. Additionally, the terminology is influenced by the political debate that emerged in the Netherlands and in Belgium, surrounding the possibility of euthanasia and assisted suicide (EAS) for older adults experiencing their life as not worth living anymore (e.g., Oosterom and van de Wier, 2020). For example, the term completed life is a literal translation of the Dutch term “voltooid leven,” which is central in the EAS debate in the Netherlands. Hence, to advance the knowledge on the phenomenon, the use of consistent and well-defined terms as well as an integration with the broader literature is needed.

This mini-review therefore has two main aims: First, we seek to present an overview of the terms that have been used in the empirical literature to describe the phenomenon that older adults experience their lives as completed and no longer worth living. We will present both definitions/descriptions of these terms and the contexts and populations they are associated with, thus not restricting our search to their use in late life populations. Second, we aim to explore how the underlying experiences are interpreted by study authors (e.g., as a normative experience, a pathological condition, an existential problem).

By taking a broad approach, we hope to gain insight into the extent to which the various terms describe the same or differing (severities of) underlying phenomena, in how far they reflect a different theoretical approach, and where terminological and theoretical overlap with other research areas might lie.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

We systematically searched four databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO (both via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCO), and Web of Science core collections. Databases were searched from inception until 16-03-2021.1 Keywords were completed life, tiredness of life, suffering from life, weariness of life, finished with life, life fatigue, and their variations (e.g., “tired of living”; based on van Wijngaarden, 2016; for the full search strings per database see OSF). In addition to the database search, we examined the reference lists of included articles as well as of related reviews that were identified through our search for further references.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Articles were eligible if they (a) were written in English, (b) published in a peer-reviewed journal, (c) discussed the topic of “tiredness of life” (or an alternative term), (d) used an empirical study design, and (e) investigated either participants with a personal, first-person experience of the phenomenon or assessed them for this experience, or studied participants with a third-person experience of the phenomenon (such as caregivers). We focused on empirical English-language articles and a study population with experience with the phenomenon as we were interested in the international use of the terminology compared to the use within the national political debate.

Study selection was performed using Mendeley and Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). In the title/abstract screening, the first 50 references were screened independently by both authors, reaching an agreement of 98%. Consequently, the first author conducted the rest of the title/abstract screening as well as the full-text screening and data extraction. From all studies, we extracted general study details (first author, year of publication, country, and study design), study focus (main aims and results), terminology, definition/description/operationalization, and interpretation/framing. Depending on the type of sample studied, we also extracted information regarding participants’ age and gender (first-person experience) or role/occupation and work experience (third-person experience). Doubts during screening and extraction were discussed with the second author.

Data Analysis

For the first aim, we made an overview of all (main) terms used for the phenomenon in the articles and then grouped them (e.g., combining tired of living and tiredness of life). For each of these terms, we then created an overview of the characteristics of the studies that applied a given term – namely country, publication year range, age range, type of sample, first- versus third-person perspective, and conducted inside versus outside EAS debate – as well as the definitions given. For the second aim, we assigned one or multiple primary and secondary perspectives to the articles based on the authors’ explicit descriptions and interpretations as well as related phenomena and mentioned theories. We tried to stay as close as possible to the authors’ wording. Then, similar to the first aim, we made an overview of study characteristics for every perspective.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

The database search identified 533 records. After duplicate deletion, 299 records remained. Sixty full-texts were assessed for eligibility, leading to 35 studies being included in the synthesis. The reference list search did not identify any additional articles (for PRISMA flow chart see Supplementary Figure S1; Moher et al., 2009). An overview of the included articles is presented in Tables 1 and 2. Studies were published between 1972 [9] and 2021 [10;35] and conducted in 14 different countries. Twenty-seven studies included participants that reported a first-person experience of the phenomenon or were assessed for its presence [Table 1 (1–27)], whereas eight studies investigated participants with a third-person experience of the phenomenon (Table 2 [28–35]). All studies on third-person experiences were conducted in the Netherlands or in Belgium and were related to the political debate surrounding EAS. Regarding the 27 studies on participants with a first-person experience, the age of samples studied varied from young people to oldest old individuals. Overall, the majority of studies focused on older adults [1–2;10–11;14;22–23;25;27], the general population [4;6–7;15–19], or healthcare professionals [28–35]. Other samples investigated were individuals who died by suicide, young adults, individuals who requested EAS, and medical samples. Most studies took a quantitative approach [1–9;11–23;25–26;28–31;33;35]. The most prevalent type of research question concerned the prevalence and/or predictors of the ToL phenomenon [1;2;4;6–8;11–13;15–19;21–22;25], while others examined ToL as a predictor, aimed at gaining an in-depth understanding of ToL or related phenomena, or concerned end-of-life decision making.

Which Terms Are Used in the Literature and How Are They Defined?

Variations of the terms tiredness of life (ToL; e.g., tired of living/life) and weariness of life (WoL; e.g., life-weariness; feeling of life-weariness) were used most frequently and sometimes interchangeably. Both terms were employed in various countries, with ToL being more prevalent in the Netherlands and in Belgium and WoL being more prevalent in Scandinavian and non-western countries. Similarly, both terms have been used since the 1970s [7;9] and were still present in the recent literature [10;35]. The populations in which the terms were applied were varied and largely overlapping. However, ToL was much more common in samples of healthcare professionals and of individuals requesting EAS, or, more broadly speaking, in studies conducted within the EAS debate. Another term used as a main term in two articles, both of which were conducted in the Netherlands and related to the EAS debate was “completed life” [25;27]. Other literally translated terms from the EAS debate were hardly adopted in the empirical literature [but see 24], and never used as main terms. We did, however, find some terminological overlap in a study that interpreted WoL in the light of a theory of caring sciences that proposes the existence of different kinds of suffering, one of which is termed “life suffering”/“suffering of life” [10]. Despite not specifying this term in our keywords, another synonym for ToL/WoL was “tedium vitae.” Tedium vitae was the major term in Ojabemi et al. [12] and a synonym in Brunoni et al. [4], both studies conducted outside of the EAS debate.

In line with the previous finding, also the definitions/descriptions of all employed terms revealed much similarity. In general, many studies mentioned synonyms or operational definitions or lacked any description at all, instead of providing a theoretical definition. Again, differences primarily emerged between studies that were conducted inside versus outside of the EAS debate. Outside of the EAS debate, most studies mentioned “the thought/feeling that life is not worth living” as their (theoretical) definition/description or operationalization/measurement of the phenomenon [1;2;4;6–8;11–13;15–20]. Moreover, the majority of these studies regarded the phenomenon as a part of suicidal ideation with a low level of intent, independent of the specific term applied [1;3–4;6–8;11;13;15–20;22]. Interestingly, although these studies usually regarded death wishes as a more severe form of suicidal ideation in the suicidal process, some studies grouped ToL/WoL together with death wishes in their measurement or analysis [8;15–17;22]. Likewise, the supposed incremental relationship from ToL/WoL over death wishes to suicidal thoughts and attempts was found by some [1;17] but not all studies [16;18].

In studies conducted within the EAS debate, in contrast, the phenomenon was not explicitly linked to suicidal ideation. Multiple studies, sometimes considering WoL and life fatigue as synonyms, defined ToL as “suffering caused by the prospect of having to continue living with a very poor quality of life, not predominantly caused by a physical or psychiatric disease, and closely associated with (/leading to) a death wish” [25,29,34–35]. One study additionally provided a definition of “completed life,” namely, “persons, mostly of old age, who do not see a future for themselves and, as a result, have developed a persistent, active death wish, without suffering that (mainly) originates in a medically classifiable condition” [25]. Usually, studies employing these definitions also mentioned the experience of feeling that “life is not worth living” in their further description of the phenomenon [25,27,34–35]. Hence, definitions/descriptions provided by studies inside and outside the EAS debate partly overlapped. Within this debate, however, definitions of the phenomenon explicitly incorporated death wishes, though their exact role and severity remained unclear. Additionally, these definitions often specified the cause for the experience as at least partly situated outside of the medical domain.

How Is the Phenomenon Interpreted?

The majority of study authors adopted a psychopathological perspective [1–9,11–12,15–23], thus, for instance, viewing the phenomenon as a condition closely associated with psychiatric disorders and as requiring treatment. This perspective in many cases was the only interpretation given and was taken across countries and populations. Studies from the Netherlands and Belgium and concerning healthcare professionals or individuals requesting EAS formed an exception. Indeed, all studies adopting a psychopathological perspective were conducted outside of the EAS debate. The second most common way of framing the phenomenon was existential [10,13,24–25,27,29;31;34–35]. These studies related the phenomenon to a lack of meaning, experiences of emptiness, or difficulties with constructing a (cultural) identity. The existential perspective was predominantly found in studies from the Netherlands and from Belgium and thus within the EAS debate, though also two Scandinavian studies on young and old adults, respectively, adopted this perspective. Notably, the psychopathological and existential perspective never appeared in combination. Merely two studies with an existential perspective additionally discussed the phenomenon’s possible relation to psychological (but not necessarily psychopathological) factors [13,34].

In addition, various studies interpreted the phenomenon as grounded in social/societal/cultural issues [4,9,13,25,27;32] or psychosocial problems [20,23,29,31]. These perspectives were always mentioned alongside other perspectives and were adopted independent of country and population, both inside and outside the EAS debate. Some ways of framing the phenomenon were exclusively found in studies linked to old age. These studies, for instance, stressed the importance of physical/medical aspects [23,25,32–33], such as of fatigue and physical deterioration, or suggested an intertwinement with physiological aspects [23]. Moreover, a narrative perspective explaining the phenomenon as a potential consequence of perceiving one’s life story as completed was adopted by two studies within the EAS debate [27,35]. Lastly, the hypothesis that life-weariness and death wishes are the result of rationally considering one’s life situation was put forward as a (secondary) perspective [2,32]. Importantly, other studies explicitly questioned this interpretation [25,27].

Of note, we could not infer a perspective for four studies [14,26,28,30], mainly from inside the EAS debate and concerning end-of-life decision making. Therefore, these studies were not included in this part of the analysis.

Discussion

Some of the terms used to denote the phenomenon that relatively healthy older adults experience their life as completed and not worth living are also employed in the broader empirical literature, especially on suicidal expressions across the life span. ToL and WoL are found most frequently, with many studies mentioning operational definitions or synonyms rather than theoretical definitions. Moreover, which terms are used, how these terms are defined, and how the experience is interpreted differs depending on country and whether a study is related to the EAS debate. Inside the EAS debate, the term ToL is common, its definition incorporates death wishes, and it is regularly framed as an existential problem. Outside of this debate, the term WoL is applied as well, the phenomenon is generally considered as a part of suicidal ideation distinct from death wishes, and its experience is often associated with psychopathology.

These differences can be understood in the light of the criteria that have to be met to be eligible for EAS in the Netherlands and in Belgium, which specify that an individual’s suffering must be grounded in a medical condition (De Jong and van Dijk, 2017). There is debate about whether older adults who do not suffer from a severe somatic or psychiatric disease but experience their lives to be completed and wish for death should have the option to request EAS (van Wijngaarden et al., 2017; Holzman, 2021). The definition of ToL inside the EAS debate is thus tailored towards this very specific group and is inherently inconsistent with a strictly psychopathological framing.

Despite their differences, the two lines of research on the phenomenon have similar limitations that future research needs to address. For instance, an overall lack of theoretical definitions and an inconsistency concerning the relationship between ToL/WoL and death wishes was observed. Clarifying this question and establishing consensus definition(s) is not only crucial for comparability among studies but will simultaneously elucidate the appropriateness of viewing the phenomenon as a part of suicidal ideation. For example, while in suicide research advances have been made by distinguishing between suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Klonsky et al., 2018), it is – especially for older adults – still unclear whether there are also qualitative differences within suicidal ideation (O’Riley et al., 2014; Van Orden and Conwell, 2016). Currently, age differences are difficult to determine, as inside the EAS debate the phenomenon is viewed as unique to late life, whereas outside this debate similar definitions are applied for varying age groups. It is conceivable, however, that reflecting about the worth of one’s life and thinking about or even hoping for one’s death can have different origins and meanings depending on an individual’s life stage. In later life, it might be indicative both of normative developmental processes of dealing with mortality as well as of underlying suicidality (Van Orden and Conwell, 2016). One possibility to gain insight into these nuances is the adoption of more diverse study designs and of theory-derived research questions that move beyond investigations of prevalence, predictors, and end-of-life decisions. Indeed, the latter has been previously emphasized with regard to late-life suicide (Van Orden and Conwell, 2016).

At the same time, combining aspects from the two lines of research could deepen the current understanding of the phenomenon. For example, the idea that “life is (not) worth living” which was included in many descriptions of the phenomenon has also been conceptualized as an evaluative component of experienced meaning in life (Martela and Steger, 2016). Thus, incorporating an existential perspective more broadly outside the EAS debate seems warranted and might offer one theoretical route forward. Concurrently, even in the study on “completed life” that selected individuals without severe diseases, individuals with death wishes displayed poor mental health and sometimes reported the lifelong presence of their death wishes (Hartog et al., 2020). Therefore, also when studying seemingly healthy samples as often done inside the EAS debate, attention for (sub-clinical) psychopathology should be kept. Actually, the distinction between existential and psychopathological factors itself might be artificial given various accounts stressing their interplay (Yalom, 1980; Maxfield et al., 2014). Similarly, results point to social-relational as well as societal-cultural influences on the experience of the phenomenon. Introducing studies on the perspectives of caregivers and relatives also outside of the EAS debate could be one way to gain more insight into these dynamics.

The current findings are strengthened by the reviews’ broad approach, including articles independent of, for example, their publication year, studied age group, or geographical location. Thereby, a comprehensive overview of research into the phenomenon was created which allows to discern variations as well as overlap in results depending on cultural developments and type of sample. At the same time, a limitation that should be kept in mind is that the findings on terminology are restricted by our keywords. There might be even more terms used to refer to the phenomenon, or related culture-specific phenomena.

Concluding, it is likely that only an integration of various perspectives will be able to do justice to the multidimensional nature of the phenomenon and can uncover potential variations in its experience across cultures, developmental stages, and health statuses. Ideally, this multidimensionality will also be reflected in the terminology used to denote the phenomenon(/a) – which is currently usually biased toward either a psychopathological or a political discourse, as well as in the applied measurement tools.

Author Contributions

JA: conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and writing – original draft. EW: conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and writing – review and editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO, Belgium; grant 1152421N to JA). The University for Humanistic Studies provided funds for open access publication fees. These funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articless/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734049/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^More detailed information on the methodology can be found on the OSF page of the study: https://osf.io/c48j6/.

References

*Barnow, S., and Linden, M. (1997). Suicidality and tiredness of life among very old persons: results from the Berlin aging study (base). Arch. Suicide Res. 3, 171–182. doi: 10.1080/13811119708258269

*Barnow, S., and Linden, M. (2000). Epidemiology and psychiatric morbidity of suicidal ideation among the elderly. Crisis 21, 171–180. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.21.4.171

*Bergman, T. D., Pasman, H. R. W., and Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2020). Complexities in consultations in case of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: a survey among SCEN physicians. BMC Fam. Pract. 21, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-1063-z

*Bolt, E. E., Snijdewind, M. C., Willems, D. L., van der Heide, A., and Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2015). Can physicians conceive of performing euthanasia in case of psychiatric disease, dementia or being tired of living? J. Med. Ethics 41, 592–598. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102150

*Brådvik, L., and Berglund, M. (1993). Risk factors for suicide in melancholia: A case-record evaluation of 89 suicides and their controls. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 87, 306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03377.x

*Brinkman-Stoppelenburg, A., Vergouwe, Y., van der Heide, A., and Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2014). Obligatory consultation of an independent physician on euthanasia requests in the Netherlands: what influences the SCEN physicians judgment of the legal requirements of due care? Health Policy 115, 75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.12.002

*Brunoni, A. R., Nunes, M. A., Lotufo, P. A., and Benseñor, I. M. (2015). Acute suicidal ideation in middle-aged adults from Brazil. Results from the baseline data of the Brazilian longitudinal study of adult health (ELSA-Brasil). Psychiatry Res. 225, 556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.047

*Copeland, A. R. (1987). Suicide by drowning. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 8, 18–22. doi: 10.1097/00000433-198703000-00005

De Jong, A., and van Dijk, G. (2017). Euthanasia in the Netherlands: balancing autonomy and compassion. World Med. J. 63, 10–15.

*Dees, M. K., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Dekkers, W. J., Vissers, K. C., and Van Weel, C. (2011). ‘Unbearable suffering’: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J. Med. Ethics 37, 727–734. doi: 10.1136/jme.2011.045492

*Dennis, M., Baillon, S., Brugha, T., Lindesay, J., Stewart, R., and Meltzer, H. (2007). The spectrum of suicidal ideation in Great Britain: comparisons across a 16-74 years age range. Psychol. Med. 37, 795–805. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000013

Gana, K., Bailly, N., Saada, Y., Joulain, M., and Alaphilippe, D. (2013). Does life satisfaction change in old age: results from an 8-year longitudinal study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 68, 540–552. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs093

Gerstorf, D., Ram, N., Röcke, C., Lindenberger, U., and Smith, J. (2008). Decline in life satisfaction in old age: longitudinal evidence for links to distance-to-death. Psychol. Aging 23:154. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.154

*Hällström, T. (1977). Life-weariness, suicidal thoughts and suicidal attempts among women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 56, 15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb06658.x

*Hartog, I. D., Zomers, M. L., van Thiel, G. J., Leget, C., Sachs, A. P., Uiterwaal, C. S., et al. (2020). Prevalence and characteristics of older adults with a persistent death wish without severe illness: a large cross-sectional survey. BMC Geriatr. 20, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01735-0

*Herrera Rodríguez, A., Caldera, T., Kullgren, G., and Salander Renberg, E. (2006). Suicidal expressions among young people in Nicaragua. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 41, 692–697. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0083-x

Holzman, T. (2021). The final act: An ethical analysis of Pia Dijkstra’s euthanasia for a completed life. J. Bioethical Inq. 18, 165–175. doi: 10.1007/s11673-020-10084-x

*Humphrey, J. A., Puccio, D., Niswander, G. D., and Casey, T. M. (1972). An analysis of the sequence of selected events in the lives of a suicidal population: a preliminary report. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 154, 137–140. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197202000-00006

Klonsky, E. D., Saffer, B. Y., and Bryan, C. J. (2018). Ideation-to-action theories of suicide: a conceptual and empirical update. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 22, 38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.020

*Koskinen, C., Nyman, G. B., and Nyholm, L. (2021). Life has given me suffering and desire–A study of older men’s lives after the loss of their life partners. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 35, 163–169. doi: 10.1111/scs.12831

*Lindner, R., Foerster, R., and von Renteln-Kruse, W. (2014). Physical distress and relationship problems. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 47, 502–507. doi: 10.1007/s00391-013-0563-z

Martela, F., and Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 11, 531–545. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

Maxfield, M., John, S., and Pyszczynski, T. (2014). A terror management perspective on the role of death-related anxiety in psychological dysfunction. Humanist. Psychol. 42, 35–53. doi: 10.1080/08873267.2012.732155

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G., Prisma Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

*Ojagbemi, A., and Bello, T. (2019). Tedium vitae in stroke survivors: a comparative cross-sectional study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 26, 195–200. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2019.1590971

*Omma, L., Sandlund, M., and Jacobsson, L. (2013). Suicidal expressions in young Swedish Sami, a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 72:19862. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.19862

Oosterom, R., and van de Wier, M. (2020). Waarom het debat over voltooid leven pas net begint. Trouw. Available at: https://www.trouw.nl/binnenland/waarom-het-debat-overvoltooid-leven-pas-net-begint~bcdb3660/.

O’Riley, A. A., Van Orden, K., and Conwell, Y. (2014). “Suicidal ideation in late life,” in The Oxford Handbook of Clinical Geropsychology. eds. N. A. Pachana and K. Laidlaw (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., and Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

*Pac, A., Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B., Brzyska, M., and Florek, M. (2013). The role of different predictors in 20-year mortality among Krakow older citizens. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 56, 524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.11.008

*Ramberg, I. L., and Wasserman, D. (2000). Prevalence of reported suicidal behaviour in the general population and mental health-care staff. Psychol. Med. 30, 1189–1196. doi: 10.1017/S003329179900238X

*Rancāns, E., Lapiņš, J., Renberg, E. S., and Jacobsson, L. (2003). Self-reported suicidal and help seeking behaviours in the general population in Latvia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 38, 18–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0602-y

*Rancāns, E., Pulmanis, T., Taube, M., Spriņǵe, L., Velika, B., Pudule, I., et al. (2016). Prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of self-reported suicidal behaviours in Latvia in 2010: a population-based study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 70, 195–201. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2015.1077887

*Renberg, E. S. (2001). Self-reported life-weariness, death-wishes, suicidal ideation, suicidal plans and suicide attempts in general population surveys in the north of Sweden 1986 and 1996. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 36, 429–436. doi: 10.1007/s001270170020

*Rietjens, J. A., van Tol, D. G., Schermer, M., and van der Heide, A. (2009). Judgement of suffering in the case of a euthanasia request in the Netherlands. J. Med. Ethics 35, 502–507. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.028779

*Rurup, M. L., Muller, M. T., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., Van Der Heide, A., Van Der Wal, G., and Van Der Maas, P. J. (2005a). Requests for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide from older persons who do not have a severe disease: an interview study. Psychol. Med. 35, 665–671. doi: 10.1017/S003329170400399X

*Rurup, M. L., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., Jansen-van der Weide, M. C., and van der Wal, G. (2005b). When being ‘tired of living’ plays an important role in a request for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: patient characteristics and the physician’s decision. Health Policy 74, 157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.01.002

*Snijdewind, M. C., Willems, D. L., Deliens, L., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., and Chambaere, K. (2015). A study of the first year of the end-of-life clinic for physician-assisted dying in the Netherlands. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 1633–1640. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3978

*Spiers, N., Bebbington, P. E., Dennis, M. S., Brugha, T. S., McManus, S., and Jenkins, R. (2014). Trends in suicidal ideation in England: the National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys of 2000 and 2007. Psychol. Med. 44, 175–183. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000317

*Stanford, S., Jones, M. P., and Loxton, D. J. (2017). Understanding women who self-harm: predictors and long-term outcomes in a longitudinal community sample. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 51, 151–160. doi: 10.1177/0004867416633298

*Sumathipala, A., Siribaddana, S., and Samaraweera, S. D. (2004). Do patients volunteer their life weariness and suicidal ideations? A Sri Lankan study. Crisis 25, 103–107. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.25.3.103

*Tuvesson, H., Hellström, A., Sjöberg, L., Sjölund, B. M., Nordell, E., and Fagerström, C. (2018). Life weariness and suicidal thoughts in late life: a national study in Sweden. Aging Ment. Health 22, 1365–1371. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1348484

*Van Humbeeck, L., Dillen, L., Piers, R., and Van Den Noortgate, N. (2020). Tiredness of life in older persons: a qualitative study on nurses’ experiences of being confronted with this growing phenomenon. The Gerontologist 60, 735–744. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz088

*Van Humbeeck, L., Piers, R., De Bock, R., and Van Den Noortgate, N. (2021). Flemish healthcare providers’ attitude towards tiredness of life and euthanasia: a survey study. Aging Ment. Health 1–7. [Preprint]. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1870205

Van Orden, K. A., and Conwell, Y. (2016). Issues in research on aging and suicide. Aging Ment. Health 20, 240–251. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1065791

van Wijngaarden, E. (2016). Ready to give up on life: A study into the lived experience of older people who consider their lives to be completed and no longer worth living. PhD dissertation. Utrecht: University of Humanistic Studies.

van Wijngaarden, E. J., Klink, A., Leget, C., and The, A. M. (2017). Assisted dying for healthy elderly people in the Netherlands: a step too far? The BMJ. 357:j2298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2298

*van Wijngaarden, E., Leget, C., and Goossensen, A. (2015). Ready to give up on life: The lived experience of elderly people who feel life is completed and no longer worth living. Soc. Sci. Med. 138, 257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.015

Keywords: systematic review, tiredness of life, life-weariness, completed life, older adults, euthanasia and assisted suicide, suicidal ideation, death wishes

Citation: Appel JE and van Wijngaarden EJ (2021) Older Adults Who Experience Their Lives to Be Completed and No Longer Worth Living: A Systematic Mini-Review Into Used Terminology, Definitions, and Interpretations. Front. Psychol. 12:734049. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734049

Edited by:

Gørill Haugan, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NorwayReviewed by:

Cristina Monforte-Royo, International University of Catalonia, SpainKenneth Chambaere, Ghent University, Belgium

Copyright © 2021 Appel and van Wijngaarden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Judith E. Appel, anVkaXRoLmFwcGVsQGt1bGV1dmVuLmJl

Judith E. Appel1,2*

Judith E. Appel1,2* Els J. van Wijngaarden

Els J. van Wijngaarden