95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 09 December 2021

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733450

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is the most common chronic neurodevelopmental disorder in childhood, placing a heavy burden on family and society. The treatment of school-aged children with ADHD emphasizes multimodal interventions, but most current research focuses solely on parent training and family functioning. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of parent-teacher training on academic performance and parental anxiety. In an open-label cluster randomized controlled trial from January 2018 to January 2019, 14 primary schools in Shanghai were randomly assigned into the intervention group and the control group, and ADHD screening was conducted for students from grades one to five. Children in both groups received medication as prescribe by their pediatricians. In the intervention group, families and teachers also received parent-teacher training. The training included ADHD behavioral interventions for parents, as well as classroom management skills for teachers. This study screened 9,295 students, 99 children in the control group and 105 children in the intervention group were included in the analysis. The intervention group demonstrated significant improvement in ADHD symptoms and academic performance and decreases in parent stress compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05). This training improved the parents’ perception of ADHD knowledge, treatment options, and drug side effects awareness (P < 0.05). Our study aims to underscore the suitability of such programs in the local nuances of the Chinese context, show application feasibility to pediatricians and psychiatrists, and provide supporting evidence for their utilization within the country’s health and educational systems.

Attention-defici/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common chronic neurological diseases in early childhood (Ameringer and Leventhal, 2013). Numerous studies have showed increasing prevalence rates of ADHD, the prevalence in children aged 6–12 years old is reported as the highest: between 9.8 and 13.3% (Willcutt, 2012; Bronsard et al., 2016). In China, the prevalence of ADHD is around 6.26% of the school-aged children (Grandjean and Landrigan, 2014; Wang et al., 2017).

ADHD brings a heavy burden and induces a variety of undesirable effects to children, parent and society. Children with ADHD have poor academic performance, quality of life, and high incidence of conflicts with parents or teachers (Lieshout et al., 2016). Parents of children with ADHD have increased parenting stress compared to parents of children with any other chronic disease, partially due to misconceptions and lack of ADHD knowledge (Zhu et al., 2015).

Currently, evidence-based treatment for school-aged children with ADHD is medical and behavioral treatment, but both therapies have limitations (Osland et al., 2018). Stimulant medication is the pharmacological treatment of choice for managing ADHD, having been endorsed by hundreds of efficacy studies to reduce core symptoms (Getahun et al., 2013; Konstenius et al., 2014). In general, medical treatment continues to be the most widely used, although it also has important limitations. Medical treatment has efficacy for most ADHD children in reducing core symptoms, however, the sustained use of methylphenidate or atomoxetine may induce drug side effects such as loss of appetite, sleep problems, and mood fluctuations (Upadhyaya et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2016).

Despite shown efficacy, quite often medical treatment suffers from poor compliance (Weisman et al., 2018), due to a general lack in parents of disease-related knowledge and recognition of the importance of medicine in the treatment landscape of ADHD. Moreover, studies have shown that medical dropout rates ranging from 13 to 64% have been observed, particularly in immediate action stimulants (Adler and Nierenberg, 2010). These shortcomings justify the implementation of psychosocial interventions that have been empirically validated as training in behavior management techniques for parents and teachers (Jessica et al., 2019). Psychosocial interventions have been considered to be well-founded and evidence-based treatments for managing the main symptoms of ADHD and have a positive effect on some executive function (Miranda et al., 2013). Previous studies have found that interventions in the school environment can reduce core symptoms of ADHD, cognitive difficulties, disruptive, and aggressive behaviors, while parental interventions can reduce family stress and improve parenting skills (Dupaul and Stoner, 2014; Amado et al., 2016; Reale et al., 2017). However, most behavioral interventions are not systematic, very few studies have included interventions for both parents and teachers.

Parent-teacher training linked family and school systems to provide support for school-aged children with ADHD (Mautone et al., 2011). This training aims to promote home and school well-functioning, strengthen the parent-child relationship, improve parents’ behavior management skills, and promote family-school collaboration through the use of components of behavioral consultation, homework interventions and daily report cards. In one of the first studies by the MTA collaborative Group explored the effects of parent-teacher training, there was no significant differences between the combined and medicine-only group in terms of the core symptoms of ADHD possibly as a result of the changes in the medication procedure (MTA Cooperative Group, 2004; Scruggs and Mastropieri, 2009). Also, fewer studies have focused on the effects of parent-teacher training on academic performance and parental anxiety in school-aged children. The effect of parent-teacher training for children with ADHD is still controversial due to the small sample size, short follow-up time and non-randomized design. Additionally, most studies have included pre-school children, not school-aged children (Epstein et al., 2016; Watzke et al., 2017).

Our study is a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the effect and acceptability of parent-teacher training, and to the best of our knowledge, it is one of the earliest attempts to evaluate the effectiveness and acceptability of pediatrician-guided parent-teacher training in China. This study aims to underscore the suitability of such programs in the local nuances of the Chinese context, show application feasibility to pediatricians and psychiatrists, and provide supporting evidence for their utilization within the country’s health and educational systems.

We aimed to explore whether the pediatrician-guided parent-teacher training could deliver a benefit for children with ADHD, compared with only received medication treatment. We hypothesis that compared with the children in the control group, the children in the intervention group would reduce ADHD symptoms, parental stress and improve academic performance after the intervention.

This study was a cluster RCT to investigate the effect and acceptability of the parent-teacher training after 4 and 10 month. It consists of three parts: ADHD screening, parent-teacher training implementation, and evaluation the effect and acceptability of the parent-teacher training.

The RCT was carried out at 14 primary schools (children aged 6–11 years) located in Jiading District, Shanghai, China. A meeting convened by professional pediatricians aims to give the teachers and the parents a better understanding of the goal of the research and the specific pattern of intervention. Parents and teachers who agreed to participate in the program must sign an informed consent. This study was conducted from January 2018 to December 2018. Parents of children who screened positive were notified by phone or e-mail to take their children to Shanghai Children’s Hospital for specialized examination. Eligible patients were included after obtaining written informed consent.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Meet the diagnosis of ADHD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). (2) Between 6–12 years old. (3) Parents agree to use methylphenidate or tomoxetine for treatment. (4) Parents can read and write the Chinese language. (5) Parents signed the informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Intellectual disability (IQ < 70). (2) excluded autistic spectrum disorder (ASD), epilepsy, schizophrenia, cerebral palsy and other nervous system diseases and mental disorders. (3) Excluded children with severe heart, brain, kidney, and other organ dysfunction. (4) Children with hearing and visual impairment.

The randomization sequence was created by a third-party statistician using SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). A total of 14 schools were included in this study and were randomly divided into the intervention group (seven schools) and the control group (seven schools). Parents, teachers, and pediatricians were aware of the allocated arm. A senior statistician who was blinded to the group allocation carried out the primary and secondary analysis.

This study provided a multimodal treatment for teachers and parents in the intervention group, which integrates family, school, and medical department to address the aims of a holistic ADHD management strategy. The parent-teacher training herein was 16-week training for parents and teachers, the three components: teacher training, family training, and ADHD knowledge improvement; and applied medical treatment were described below. Details describing the treatment components were provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Children in both the intervention and control groups were treated with medication. All children started stimulant medication as prescribed by their pediatricians, referring to the clinical practice guidelines for ADHD children published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (2000).

The intervention was implemented by hospital pediatricians targeting to improve the knowledge of ADHD, behavioral intervention and teachers’ classroom management. Hospital pediatricians conducted 1 group meeting with participating school teachers (30-min introduction session, 1-h classroom behavior management, and 30-min case introduction) and 1 school-based consultation with parents and school teachers (30 min communication between parents and teachers about the performance of children). Teachers completed the daily behavior report card and homework plan (Pfiffner et al., 2018).

The intervention began with an overview of the study and behavioral intervention for ADHD children conducted by hospital pediatricians. Hospital pediatricians conducted 2 group parent trainings sessions (30-min introduction session, 2-h ADHD knowledge course, 1-h family behavior management course, and 1-h case introduction) and 2 individualized family therapy sessions (1-h communication between hospital pediatricians and parent and 1-h parent-children interaction). The training included the use of commands, rewards, discipline, and stress management. There were two conferences calls between the hospital pediatricians and the parents (approximately for 10 min) to monitor the children’s treatment and to improve the intervention if needed.

This study established a WeChat messaging platform-based (Tencent Holdings Limited, Shenzhen, China) official account, which was followed by the parents. ADHD information was published to parents and teachers with the goal to inform about ADHD and gain disease-related knowledge through pictures, texts, and videos. In addition, this study distributed two training manuals to introduce the symptoms, causes, diagnosis, treatment, and intervention of ADHD to the children in the intervention group (Fleming et al., 2017).

This training was conducted by multi-disciplinary research team whose participants are hospital pediatricians, psychologist, statistician, postgraduates, and teachers in 14 primary schools in Jiading District. All teacher and parent trainings were held in the classrooms of primary schools and the intervention was conducted by the hospital pediatricians. Ninety five percentage teachers participated in teacher training, and 80% parents participated in family training. This study contacted with parents by telephone every month and inquired about treatment status, medication status, and drug side effects.

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children’s Hospital (2018R003) and registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry1 as ChiCTR1800014945. All participants signed the informed consent.

Researchers use Conners Parent Symptom Questionnaire (PSQ) and Conners Teacher Rating Scale (TRS) to assess the symptoms of ADHD in primary school children. There are 48 items in PSQ, including six factors including conduct problems, learning problems, psychosomatic, hyperactivity-impulsivity, anxiety, and ADHD index (Conners et al., 1998). The higher the scores, the higher the probability of having ADHD, if the ADHD index is ≥ 1.5, indicating that the child may have ADHD. TRS is a scale used by teachers to assess behavioral problems in children. It contains 28 items, including five factors of conduct, hyperactivity, inattention, and ADHD index. The higher the scores, the higher the probability of having ADHD, if ADHD index ≥ 1.5, indicating that the child may have ADHD.

Swanson Nolan and Pelham’s fourth scale (SNAP-IV) contains 26 items, including three factors of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. The higher the score, the more severe the ADHD symptoms. Researchers use it to assess the severity of core symptoms of ADHD. The whole consistency Cronbach α = 0.94, the subscales for attention deficit, hyperactivity – impulsivity, and oppositional disobedience were 0.90, 0.79, and 0.89, respectively.

The secondary outcomes consisted of academic performance and parent stress, all questionnaires were measured at baseline (t1), the end of the treatment (t2), and 10-month (t3) (see Supplementary Table 2).

Academic Performance Questionnaire (APQ) was developed based on the Olivero Bruni’s Teacher school achievement form and school-teacher can APQ to assess students’ academic performance. The questionnaire consists of 15 items using 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating better performance and four subscales (attention, study interest, school achievement, and executive ability). The internal consistency Cronbach α = 0.962 (Zhang et al., 2015).

Parenting Stress Index (PSI) is used to assess the difficulties, anxiety, nervousness, and the level of parenting stress which aims to identify various difficulties in children’s growth and development (Haskett et al., 2017). It consists of 36 items using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5 and three subscales (parent stress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child). The internal consistency Cronbach α = 0.88.

The Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire (TAQ) scale were rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) with higher scores indicating the greater acceptability. TAQ is 8-item measure and is widely used in the treatment acceptability assessment of ADHD children (Krain et al., 2005).

This study collected the child’s gender, child’s age, child’s grade, primary caregivers, socioeconomic status, family structure, parents’ age, parents’ education degree, and child’s ADHD medication status.

We used PASS 16 software (NCSS, the United States) to calculate the sample size. The sample size was based on the primary outcome of this study; the SNAP-IV scores at 10 months between the intervention group and the control group. In this study, we assumed the difference of mean scores in the intervention group and the control group was 0.2 with the standard deviation (SD) 0.48 (Power et al., 2012). Since this study is an exploratory test, a two-sided test was used. In order to defect 80% of the power of this difference when a two-sided alpha = 0.05 is applied, each group size of 88 (total sample size n = 176) is needed. In order to adjust the drop out and loss of 10%, 194 participants will be needed.

In this study, 105 children were eventually in the intervention group and 99 children were included in the control group. Multiple imputation methods were used to replace the missing data in the primary efficacy analysis to reduce potential confounding bias. The baseline variables of the two groups were compared by analysis of a t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Comparisons between the intervention group and the control group for the continuous outcome variables were performed with the use of linear mixed effect model to repeated measures. We had planned to use a linear mixed-effect model for the primary and secondary outcomes analysis. The model included group, time, the interaction of group with time as fixed effects and child-specific random intercepts, child age and mother age as covariates.

All data were performed with SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) and R version 4.0.22 to evaluate intervention effects on the primary outcomes and secondary outcomes.

A total of 9,295 children completed the screening questionnaire, 334 (3.59%) were positive for the screening. Of those 334 children screening positive children, 243 (72.75%) were diagnosed ADHD. However, 21 children were excluded because 5 children have developmental delay, 4 students drop out of school, and 12 declined to participate this study. Information on the flow diagram of participant enrollment in this study is shown in Figure 1. A total of 204 children were included in the analysis. There were no serious adverse events and adverse events reported.

Table 1 shows the demographics and treatment status of the 99 children in the control group and 105 children in the intervention group. There were no statistically significant between the intervention group and the control group except the child age and mother age (P > 0.05). As shown in Table 1, there were 85 boys (85.9%) and the mean age was 8.39 in the intervention group. There were 90 boys (85.7%) and the mean age was 7.71 in the control group.

In this study, 64.8% of the parents in the intervention group hold the opinion that this treatment would help their children. Supplementary Table 3 showed the mean and SDs of the eight items scores for the TAQ of the intervention group.

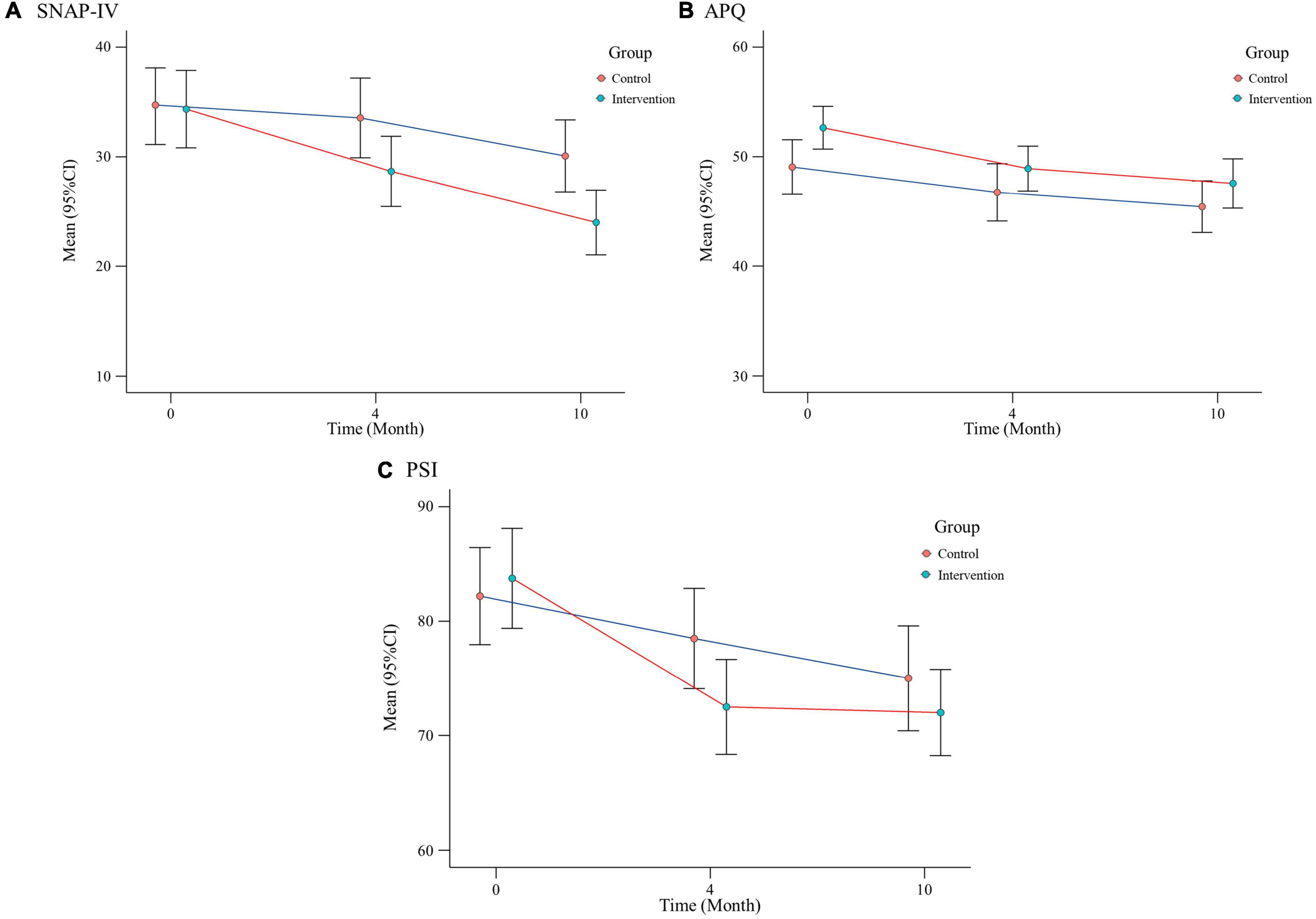

We first analyzed the mean and 95% CI for the outcome variables at different time point and change from baseline between the two groups (see Table 2). SNAP-IV scores decreased at different time points in both the intervention and control group (see Figure 2). From baseline to 10 months, mean scores of SNAP-IV decreased from 34.34 (95% CI:30.81–37.87) to 23.98 (95%CI:21.02–26.94) in the intervention group and from 34.72 (95% CI:31.33–38.10) to 30.07 (95% CI:26.78–33.36) in the control group. Changes over time are shown in Figure 2. The Figure 2 showed that the SNAP-IV scores, APQ scores, and PSI scores were improved in both the intervention group and the control at post-treatment and follow-up.

Figure 2. Effects of interventions over time: changes in SNAP-IV, APQ, and PSI in two groups of participants at different visit points.

The mixed effect models revealed that the greater improvements in ADHD symptoms (F = 8.27, P = 0.005), academic performance (F = 11.05, P = 0.001) and parent stress (F = 4.30, P = 0.042) in the intervention group as compared to the control group. The mixed model showed significant difference in the ADHD performance, academic performance, and parent stress over time (P < 0.05). There was no significant time×group effect on all outcome variables (P > 0.05) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Results of mixed effect models of the outcome measures between the intervention group and the control group.

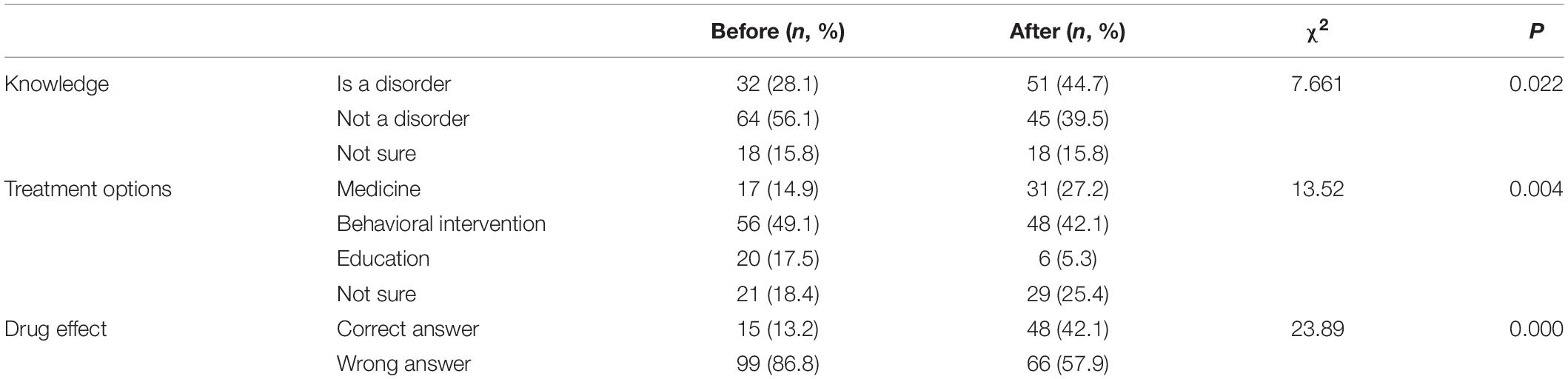

There were statistically significant differences in ADHD knowledge, treatment options, and drug side effects between baseline and 4-month follow-up (P < 0.05). Before training, there were only 28.1% believed that ADHD was a neurological disorder, 14.9% believed medication was the first-line treatment and 13.2% parents drug effects answered correctly. While after training, 44.7% believed that ADHD was a neurological disorder, 27.2% believed medication was the first-line treatment and 42.1% parents answered drug effects correctly (see Table 4).

Table 4. Parents’ knowledge, treatment options, and drug effect toward treatment before and after training (intervention group).

This study provided a multimodal treatment for patients and teachers in the intervention group, which integrates family, school, and health care providers’ efforts to address the aims of a holistic ADHD management strategy. This study provides evidence for the effectiveness of parent-teacher training for school-aged children with ADHD. Parent-teacher training has a significant impact on the family involvement in education, academic performance, and parental stress. ADHD treatment paradigm consists of long-term standardized medical treatment and non-medical treatments. The superiority of parent-teacher training was verified and all outcome variables were changed significantly over time. This study referred to previous studies demonstrating effective behavioral intervention in children with ADHD (Goossens et al., 2016). In addition, this study showed that parent-teacher training is an acceptable treatment.

This study found that during the intervention period, children in the intervention group showed a gradual reduction in their core symptoms and an improvement in their academic performance. The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that behavioral therapy combined with pharmacotherapy is effective, and behavioral interventions for parents and classroom behavioral interventions for teachers are very effective in changing the core symptoms of children with ADHD (American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Public Education, 2001). ADHD children often had learning dysfunction, including poorer academic performance, classroom disorganization, dropout, and disciplinary behavior. Our findings are in the line with previous studies, teacher training was shown to be effective in reducing the core symptoms of ADHD, difficulties in cognition and disruptive behaviors (Betty et al., 2017). Previous studies have found that poor home environments were associated with poorer academic performance (Polderman et al., 2010). The study showed that it was effective in increasing academic productivity, social competence and rule compliance (Charach et al., 2013). This study enhanced parents’ and teachers’ ADHD knowledge, classroom management skills, and family parenting skills to help children improve their academic performance (Loo et al., 2016).

Stress within a family has wide implication of familial well-being; for example, socio-ecological theories suggest that stress on one family member may influence any other family members and cause disputes and disharmony (Sola et al., 2016). Previous studies have shown parent training do not only change children’s behavior; in some cases, they can also improve family functions and reduce parental stress (Ciesielski et al., 2020). In clinical practice, strengthening disease-related education for parents can improve parents’ perception and knowledge of ADHD, help parents acquire parental skills, gain social support, enhance parent-child interaction, and reduce the stress of caring for children with ADHD (Schuck et al., 2018). This study improved parents’ knowledge of ADHD disease, treatment options and drug side effect. For ADHD children, parent beliefs and attitudes toward ADHD are of critical importance, parents’ belief about ADHD medication outweigh evidence of the real benefits and risk (Veloso et al., 2019). The previous study of the research team found that a significant correlation acceptance of pharmacotherapeutic, and parent-teacher training could increase the medication adherence (Zhang et al., 2020). Multimodal therapies are beneficial because they can help providers directly solve obstacles in multiple fields through parent-teacher collaboration, and increase the participation of families and schools in children’s academic life (Sciutto, 2015).

The results of this study provide support for parent-teacher training. First, this study is the first to demonstrate that a parent-teacher training in ADHD children can decrease the parent stress. Second, unlike most previous studies, this study investigated the differential effectiveness of medical treatment and combined intervention. Most guidelines recommend that medication therapies are the primary treatment for school aged children with ADHD, this study explored the additional effects of Parent-teacher training (Thapar and Cooper, 2016). All teacher and parent trainings were carried out at school. Third, this study found that the combining medicine and parent-teacher intervention has a significant effect on the school-aged children with ADHD. The multimodal intervention of children provides a theoretical basis, further indicating that the ADHD disease is related to multiple mechanisms such as psychological and social factors. Researchers should focus on individualized courses for children of different grades, and how to maintain the effect of intervention.

Our study is a cluster RCT, session-based training for both teachers and parents and investigate the effect and acceptability of the parent-teacher training after 4 and 10 months after enrollment. The findings from our study indicate that parent-teacher training improves children’s core symptoms and academic performance, and reduces parental anxiety. While at the same time, the intervention improves parental attitudes and perceptions of ADHD.

Our study is a cluster RCT to investigate the effect and acceptability of pediatrician conducted parent-teacher training and to the best of our knowledge, it is one of the earliest attempts to evaluate the effectiveness and acceptability of parent-teacher training in China. Compared with previous studies, this study has a larger sample size and longer follow-up time.

There are several limitations in this study. Some children who screened positive refused to participate in the study, so the prevalence of ADHD in this study was about 2.5% in this study which is lower than the prevalence reported in the literature. We have not explored the role of possible symptoms of ADHD of the parents in the treatment of their children (Sanchez et al., 2019). Also, this study did not explore the possible factors that may condition the response to treatment, as the MTA study has shown (Swanson et al., 2001). Finally, the ADHD symptoms were only assessed by parents, and teachers’ assessment results were not collected.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children’s Hospital (2018R003). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

LS and YW designed this research. JC and YT coordinated the implementation of this research. LS wrote the manuscript. LS and CW contributed to the analysis of this research. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

This study is supported in part by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality under Grant 18XD1403200 and 17511108902; Shanghai Municipal Health Commission under Grant GWV-10.1-XK19-1 and 2020YJZX0207; and in part by the Science Foundation of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital under Grant No. lygl202101; and in part by Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission Medical Guidance Science and Technology Support Project (19411969000); and in part by Shanghai Natural Science Foundation under Grant 19ZR1477700.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733450/full#supplementary-material

Adler, L. A., and Nierenberg, A. A. (2010). Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad. Med. 122, 184–191. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2112

Amado, L., Jarque, S., and Ceccato, R. (2016). Differential impact of a multimodal versus pharmacological therapy on the core symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. Res. Dev. Disabil. 59, 93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.08.004

American Academy of Pediatrics (2000). Clinical Practice Guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 105, 1158–1170. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1158

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Public Education (2001). American academy of pediatrics: children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics 107, 423–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Arlington, VA: Author.

Ameringer, K. J., and Leventhal, A. M. (2013). Associations between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom domains and DSM-IV lifetime substance dependence. Am. J. Addict. 22, 23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00325.x

Betty, V., Marjolein, L., and Jaap, O. (2017). Further Insight into the effectiveness of a behavioral teacher program targeting ADHD symptoms using actigraphy, classroom observations and peer ratings. Front. Psychol. 8:1157. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01157

Bronsard, G., Alessandrini, M., Fond, G., Loundou, A., Auquier, P., Tordjman, S., et al. (2016). The prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in the child welfare system: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 95:e2622. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002622

Charach, A., Carson, P., Fox, S., Ali, M. U., Beckett, J., and Lim, C. G. (2013). Interventions for preschool children with high risk of ADHD: a comparative effectiveness review. Pediatrics 131, 1584–1604. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0974

Ciesielski, H. A., Loren, R. E., and Tamm, L. (2020). Behavioral parent training for ADHD reduces situational severity of child noncompliance and related parental stress. J. Atten. Disord. 24, 758–767. doi: 10.1177/1087054719843181

Conners, C. K., Sitarenios, G., Parker, J. D., and Epstein, J. N. (1998). Revision and restandardization of the conners teacher rating scale (CTRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J. Abnormal Child Psychol. 26, 279–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1022606501530

Dupaul, G. J., and Stoner, G. D. (2014). ADHD in the schools: assessment and intervention strategies. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychol. 34, 13–19.

Epstein, J. N., Kelleher, K. J., Baum, R., Brinkman, W. B., Peugh, J., Gardner, W., et al. (2016). Impact of a web-portal intervention on community ADHD care and outcomes. Pediatrics 138:e20154240. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4240

Fleming, M., Fitton, C. A., Steiner, M. F. C., McLay, J. S., Clark, D., King, A., et al. (2017). Educational and health outcomes of children treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 171:e170691. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0691

Getahun, D., Jacobsen, S. J., Fassett, M. J., Chen, W. S., Demissie, K., and Rhoads, G. G. (2013). Recent trends in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 167, 282–288. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.401

Goossens, F. X., Lammers, J., Onrust, S. A., Conrod, P. J., Castro, B. O. D., and Monshouwer, K. (2016). Effectiveness of a brief school-based intervention on depression, anxiety, hyperactivity, and delinquency: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 25, 639–648. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0781-6

Grandjean, P., and Landrigan, P. J. (2014). Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. 13, 330–338. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70278-3

Haskett, M. E., Ahern, L. S., Ward, C. S., and Allaire, J. C. (2017). Factor structure and validity of the parenting stress index-short form. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 46, 170–170. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14

Jessica, V. D., Martijin, A., Hartmut, H., Madelon, A. V., Ute, S., and Sandra, K. L. (2019). Sustained effects of neurofeedback in ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 28, 293–305. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1121-4

Konstenius, M., Jayaram-Lindstrom, N., Guterstam, J., Beck, O., Philips, B., and Franck, J. (2014). Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and drug relapse in criminal offenders with substance dependence: a 24-week randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction 109, 440–449. doi: 10.1111/add.12369

Krain, A. L., Kendall, P. C., and Power, T. J. (2005). The role of treatment acceptability in the initiation of treatment for ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 9, 425–434. doi: 10.1177/1087054705279996

Lieshout, M. V., Luman, M., Twisk, J. W. R., Ewijk, H. V., Groenman, A. P., Thissen, A. J. A. M., et al. (2016). A 6-year follow-up of a large European cohort of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-combined subtype: outcomes in late adolescence and young adulthood. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 25, 1007–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0820-y

Lo, H. H., Wong, S. Y., Wong, J. Y., Wong, S. W., and Yeung, J. W. (2016). The effect of a family-based mindfulness intervention on children with attention deficit and hyperactivity symptoms and their parents: design and rationale for a randomized, controlled clinical trial (study protocol). BMC Psychiatry 16:65. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0773-1

Loo, S. K., Bilder, R. M., Cho, A. L., Sturm, A., Cowen, J., Walshaw, P., et al. (2016). Effects of d-methylphenidate, guanfacine, and their combination on electroencephalogram resting state spectral power in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.020

Mautone, J. A., Lefler, K. E., and Thomas, J. T. (2011). Promoting family and school success for children with ADHD: strengthening relationships while building skills. Theory Pract. 50:43. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2010.534937

Miranda, A., Presentacion, M. J., Siegenthaler, R., and Jara, P. (2013). Effects of a psychosocial intervention on the executive functioning in children with ADHD. J. Learn. Disabil. 46, 363–376. doi: 10.1177/0022219411427349

MTA Cooperative Group (2004). National Institute of mental health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: 24-month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 113, 754–761. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.754

Osland, S. T., Steeves, T. D., and Pringsheim, T. (2018). Pharmacological treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbidtic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6:CD007990. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007990.pub3

Pfiffner, L. J., Rooney, M. E., Jiang, Y., Haack, L. M., Beaulieu, A., and McBurnett, K. (2018). Sustained effects of collaborative school-home intervention for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and impairment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 57, 245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.016

Polderman, T. J. C., Boomsma, D. I., Bartels, M., Verhulst, F. C., and Huizink, A. C. (2010). A systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 122, 271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01568.x

Power, T. J., Mautone, J. A., Soffer, S. L., Clarke, A. T., Marshall, S. A., Sharman, J., et al. (2012). A family-school intervention for children with ADHD: results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 80, 611–623. doi: 10.1037/a0028188

Reale, L., Bartoli, B., Cartabia, M., Zanetti, M., Costantino, M. A., Canevini, M. P., et al. (2017). Comorbidity prevalence and treatment outcome in children and adolescents with ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 1443–1457. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1005-z

Sanchez, M., Labigne, R., Romero, J. F., and Elosegui, E. (2019). Emotion regulation in participants diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, before and after an emotion regulation intervention. Front. Psychol. 10:1092. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01092

Schuck, S. E. B., Johnson, H. L., Abdullah, M. M., Stehli, A., Fine, A. H., and Lakes, K. D. (2018). The role of animal assisted intervention on improving self-esteem in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Front. Pediatr. 6:300. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00300

Sciutto, M. J. (2015). ADHD knowledge, misconceptions, and treatment acceptability. J. Atten. Disord. 19, 91–98. doi: 10.1177/1087054713493316

Scruggs, T. E., and Mastropieri, M. A. (2009). Intervention with students with ADHD analysis of the effects of a multi-component and multi-contextualized program on academic and social emotional adjustment. Adv. Learn. Behav. Disabil. 22, 227–263. doi: 10.1108/S0735-004X20090000022010

Sola, H. D., Salazar, A., Duenas, M., Ojeda, B., and Failde, I. (2016). Nationwide cross-sectional study of the impact of chronic pain on an individual’s employment: relationship with the family and the social support. BMJ Open 6:e012246. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012246

Swanson, J. M., Kraemer, H. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Arnold, L. E., Conners, C. K., Abikoff, H. B., et al. (2001). Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 168–179. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011

Thapar, A., and Cooper, M. (2016). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 387, 1240–1250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00238-X

Upadhyaya, H., Kratochvil, C., Ghuman, J., Camporeale, A., Lipsius, S., D’Souza, D., et al. (2015). Efficacy and safety extrapolation analyses for atomoxetine in young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 25, 799–809. doi: 10.1089/cap.2014.0001

Veloso, A., Vicente, S. G., and Filipe, M. G. (2019). Effectiveness of cognitive training for school-aged children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 10:2983. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02983

Wang, T., Liu, K., Li, Z., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., Shi, W., et al. (2017). Prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 17:32–43. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1187-9

Watzke, B., Haller, E., Steinmann, M., Heddaeus, D., Harter, M., Konig, H. H., et al. (2017). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone-based cognitive-behavioural therapy in primary care: study protocol of TIDe - telephone intervention for depression. BMC Psychiatry 17:263. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1429-5

Weisman, O., Schonherz, Y., Harel, T., Efron, M., Elazar, M., and Gothelf, D. (2018). Testing the efficacy of a smartphone application in improving medication adherence among children with ADHD. Isr. J. Psychiatry 55, 59–63.

Willcutt, E. G. (2012). The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics 9, 490–499. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8

Zhang, X. F., Shen, L., Jiang, L., Shen, X., Xu, Y., Yu, G. J., et al. (2020). Parent and teacher training increases medication adherence for primary school children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Front. Pediatr. 7:486353. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.486353

Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., Jiang, Y., Sun, W., Wang, Y., Chen, W., et al. (2015). Association between physical activity and teacher-reported academic performance among fifth-graders in shanghai: a quantile regression. PLoS One 10:e0115483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115483

Keywords: ADHD, parent-teacher training, academic performance, parental anxiety, randomized controlled trial

Citation: Shen L, Wang C, Tian Y, Chen J, Wang Y and Yu G (2021) Effects of Parent-Teacher Training on Academic Performance and Parental Anxiety in School-Aged Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial in Shanghai, China. Front. Psychol. 12:733450. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733450

Received: 01 September 2021; Accepted: 17 November 2021;

Published: 09 December 2021.

Edited by:

Anna Maria Re, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Manuel Soriano-Ferrer, University of Valencia, SpainCopyright © 2021 Shen, Wang, Tian, Chen, Wang and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Wang, d3lfcmFpbkAxMjYuY29t; Guangjun Yu, Z2p5dUBzaGNoaWxkcmVuLmNvbS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.