- School of Foreign Languages, Xinyang College, Xinyang, China

Following the recent special issue in the journal of Frontiers in Psychology, named “The Role of Teacher Interpersonal Variables in Students’ Academic Engagement, Success, and Motivation,” this review is carried out to describe two prime instances of teacher interpersonal behaviors, namely teacher confirmation and stroke, their underlying frameworks, and contributions to desirable student-related outcomes. In light of rhetorical-relational goal theory and the school of positive psychology, it is stipulated that language teacher confirmation and stroke are facilitators of EFL/ESL students’ level of motivation and academic engagement. Providing empirical evidence, the argument regarding the pivotal role of language teacher confirmation and stroke in EFL/ESL contexts was proved. Reviewing the available literature on the aforementioned variables, some pedagogical implications were suggested for teacher trainers, educational supervisors, and pre- and in-service language teachers. Finally, the limitations and drawbacks of the reviewed studies were identified and some avenues for further research were recommended, accordingly.

Introduction

The impact of teacher interpersonal variables on students’ academic engagement, success, and motivation is the focus of a recent special issue in the journal of “Frontiers in Psychology.” In an effort to respond to this call, the present theoretical review aims to delineate two important interpersonal behaviors of teachers, namely teacher confirmation and stroke, their underlying theoretical frameworks, as well as their capability in predicting EFL/ESL students’ motivation and academic engagement in instructional-learning environments. As put forward by Pekrun and Schutz (2007), desirable student-related outcomes can be attained in an educational atmosphere where in students enjoy their learning experiences. Among different factors providing pleasant learning experiences for students in educational contexts, positive teacher-student interpersonal relationship is of great significance (Gałajda et al., 2016; Wendt and Courduff, 2018; Sun et al., 2019). To put it simply, the teacher-student relationship is one of the fundamental building blocks for an effective instructional-learning environment. This is mainly due to the fact that both teachers and students are equally responsible for the effective implementation of the learning and teaching processes; hence, they have to collaborate to create a favorable learning condition (Gabryś-Barker and Gałajda, 2016). Given the importance of teacher-student interpersonal relationship, an increasing attention has been paid to its essence and quality (e.g., Yu and Zhu, 2011; Zhang, 2011; Zhang and Sapp, 2013; Zhu, 2013; Pishghadam and Khajavy, 2014; Wei et al., 2015; Henry and Thorsen, 2018; Wendt and Courduff, 2018; Nayernia et al., 2020; Derakhshan, 2021; Pishghadam et al., 2021).

In any interaction, teachers and students may affect each other either negatively or positively (Zhong, 2013; Brinkworth et al., 2018; Pishghadam et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2020). While a negative teacher-student relationship may result in several adverse consequences (e.g., anxiety, burnout, depression, etc.), a positive teacher-student connection can have a desirable impact on students’ motivation and academic engagement (Roorda et al., 2011; Van Uden et al., 2014; Martin and Collie, 2019; Derakhshan, 2021). Employing appropriate interpersonal behaviors, teachers can develop such a positive relationship with their students. Interpersonal behaviors are verbal, para-verbal, and non-verbal in nature (Babonea and Munteanu, 2012; Dobrescu and Lupu, 2015; Tranca and Neagoe, 2018). Verbal interpersonal communication refers to “a two-way exchange that involves both talking and listening” (Babonea and Munteanu, 2012, p. 2). Such interpersonal communication is crucial in forming bonds and developing relationships between teachers and their students. Verbal interpersonal behaviors enable teachers to draw students’ attention during their instruction. In the case of para-verbal interpersonal communication, “the message is not transmitted through words, but could not get to the listeners without speaking” (Babonea and Munteanu, 2012, p. 2). As put forward by Tranca and Neagoe (2018), Para-verbal interpersonal communication is directly related to the “intonation,” “the volume of voice,” “the intensity of voice,” “the tone of voice,” and “the speech rate.” Finally, non-verbal interpersonal communication “uses as tools physical appearance, facial expression, and gesture, which give nuances to the message” (Babonea and Munteanu, 2012, p. 3). Non-verbal interpersonal communication behaviors are tied with “posture,” “hand gestures,” “body movements,” “facial expressions,” and “eye contact” (Tranca and Neagoe, 2018).

Teacher care, credibility, clarity, confirmation, stroke, humor, immediacy, and praise are examples of verbal, para-verbal, and non-verbal interpersonal behaviors. Among them, this review mainly focuses on confirmation and stroke as the prime instances of teacher positive interpersonal behaviors. The following sections explain these two interpersonal behaviors, their underpinning frameworks, as well as two student-related variables, namely motivation and academic engagement, empirically proved to be predicted by the aforementioned interpersonal behaviors.

Teacher Confirmation

For more than four decades, the term “confirmation” has emerged in theological, philosophical, and communication literature. Several scholars have highlighted the pivotal role of confirmation in teacher-student interpersonal relationships (e.g., Goodboy and Myers, 2008; Schrodt and Finn, 2011; Goldman et al., 2014; Goldman and Goodboy, 2014; Hsu and Huang, 2017; Geier, 2020). Ellis (2000) referred to teacher confirmation as “the transactional process by which teachers talk and interact with students that make them feel they are valuable and significant individuals” (p. 265). The concept of teacher confirmation dates back to the “Broaden-and-Build Theory” (Fredrickson, 2001) and “Emotional Response Theory” (Mottet and Beebe, 2006).

Emotional Response Theory was designed to describe the intricacies of the interaction between “teacher communication behaviors” and “students’ behavioral and emotional responses” (Mottet et al., 2006, p. 259). As put forward by Mottet et al. (2006), relationally-oriented teaching behaviors such as confirmation have an enormous effect on students’ feelings of arousal, enjoyment, and dominance, which in turn encourages students to participate in approach behaviors toward learning. Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden-and-build theory also suggests that students’ cognitive abilities can be dramatically enhanced by experiencing positive feelings. However, the degree of teacher confirmation appears to have a significant impact on this association (Schrodt and Finn, 2011). To put it differently, students’ conduct and attitudes toward instruction and instructional-learning context can be improved by receiving confirmation from others, illustrating the considerable association between teacher confirmation behaviors and student-related outcomes (Goldman et al., 2018).

Ellis (2000) characterized teacher confirmation around four major dimensions, namely “responding to students’ questions and/or comments,” “demonstrating interest in the student’s learning process,” “employing an interactive teaching style in the classroom,” and “absence of general disconfirmation” (p. 266). The first dimension relates to how much time teachers devote to answering students’ questions effectively, and to what extent teachers take time to listen to students’ questions carefully. The second dimension is concerned with teachers’ interests in students’ learning process, or whether teachers are sufficiently enthusiastic about their students’ study process. The third dimension refers to what extent teachers employ interactive teaching methods to assist students in understanding course content. Employing an interactive teaching style, teachers can modify their teaching practices based on their students’ needs and interests. Finally, the fourth dimension of teacher confirmation is tied with not exhibiting any disconfirming actions toward students, which can be deemed as a kind of confirmation (Ellis, 2004). Previous research has revealed that teacher confirmation behavior is associated with EFL/ESL student-related variables such as increased achievement (Goodboy and Myers, 2008; Hsu, 2012; Goldman et al., 2014; Santana, 2017), motivation (Ellis, 2004; Shen and Croucher, 2018; Croucher et al., 2021), and academic engagement (Campbell et al., 2009; LaBelle and Johnson, 2020).

Teacher Stroke

The notion of stroke is conceptualized as a unit of human recognition that may be used to meet an individual’s desire for recognition (Berne, 1988). It may be traced back to Berne’s (1988) transactional analysis (TA). As put forward by Stewart and Joines (1987), TA is “a theory of personality and a systematic psychotherapy for personal growth and personal change” (p. 4). Newell and Jeffery (2002) categorized TA into six components of “strokes,” “time structures,” “ego states,” “life positions,” “life scenario,” and “transactions.” Regarding the significance of stroke, the first component of TA, Berne et al. (2011) stated that stroke is a crucial element in improving our life quality. Individuals employ a variety of strategies to give and accept a stroke. In this regard, Stewart and Joines (1987) have divided stroke into three dichotomous categories: verbal/non-verbal, positive/negative, and conditional/unconditional. Verbal strokes include the exchange of speech, ranging from saying a single word to maintaining a lengthy conversation. Non-verbal strokes, on the other hand, cover a wide range of non-verbal actions such as smiling and nodding. Negative strokes cause dissatisfaction, whereas positive strokes result in happiness, enjoyment, and satisfaction. In terms of conditional and unconditional strokes, Berne (1988) expounded that “unconditional strokes are related to what you are, while conditional strokes are about what you do” (Pishghadam et al., 2019, p. 286).

The concept of stroke is commonly used in educational psychology to refer to “teacher feedback” and “teacher praise” (Amini et al., 2019). In Instructional-learning contexts, instructors can stroke students in a number of ways, including “calling students by their names,” “allowing them to express themselves,” and “offering adequate feedbacks” (Amini et al., 2019, p. 28). According to Hattie and Timperley (2007), a stroke-rich instructional setting motivates EFL/ESL students to perform better. Similarly, Rajabnejad et al. (2017) hold that teachers’ stroke increases students’ tendency to repeat desirable behaviors that are essential for their academic success. Previous research proved that teacher strokes enable them to promote EFL/ESL students’ willingness to attend classes (Pishghadam et al., 2021), intelligence, care, and feedback (Derakhshan et al., 2019), motivation (Akin-Little et al., 2004; Pishghadam and Khajavy, 2014), as well as academic engagement (Van Uden et al., 2014).

Student Motivation

In a broad sense, motivation deals with individuals’ motive “to make certain decisions,” “to participate in the activity,” and “to persist in pursuing it” (Ushioda, 2008). With regard to language learning, Gardner (1985) defined motivation as the degree of effort a person expends to learn language. Dörnyei (2005) also referred to language motivation as the primary impetus for initiating language learning as well as the reason for continuing the prolonged and tedious process of learning.

Katt and Condly (2009) classified student motivation to learn a language into two main categories of “trait motivation” and “state motivation.” Trait motivation is “a general tendency toward learning,” whereas state motivation is “an attitude toward a particular course” (Katt and Condly, 2009, p. 217). While students’ trait motivation inclines to be stable, their state motivation can be directly or indirectly influenced by their teachers’ interpersonal behaviors (Fallah, 2014). Hence, in interaction with students, teachers should employ positive interpersonal behaviors such as confirmation (Ellis, 2004; Shen and Croucher, 2018; Croucher et al., 2021) and stroke (Akin-Little et al., 2004; Pishghadam and Khajavy, 2014) to enhance EFL/ESL student motivation to learn language.

Student Academic Engagement

The definition and scope of student engagement vary considerably. That is, almost all scholars conceptualized this concept differently. Lamborn et al. (1992), for instance, defined student engagement as “students’ psychological effort and investment toward learning, understanding, or mastering the skills, crafts, or knowledge that the coursework is intended to promote” (p. 13). Later, Skinner et al. (2009) referred to this concept as “the quality of students’ participation or connection with the educational endeavor and hence with activities, values, people, goals, and place that comprise it” (p. 495). Despite the fact that the scope and conceptualization of student engagement are extremely different, scholars have agreed upon the multidimensionality of this concept. They believe that student academic engagement covers a number of factors that work together to display students’ positive feelings toward the learning process (Fredricks et al., 2004; Christenson et al., 2008; Reeve and Tseng, 2011; Carter et al., 2012; Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro, 2013; Phan, 2014; Lei et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020, 2021).

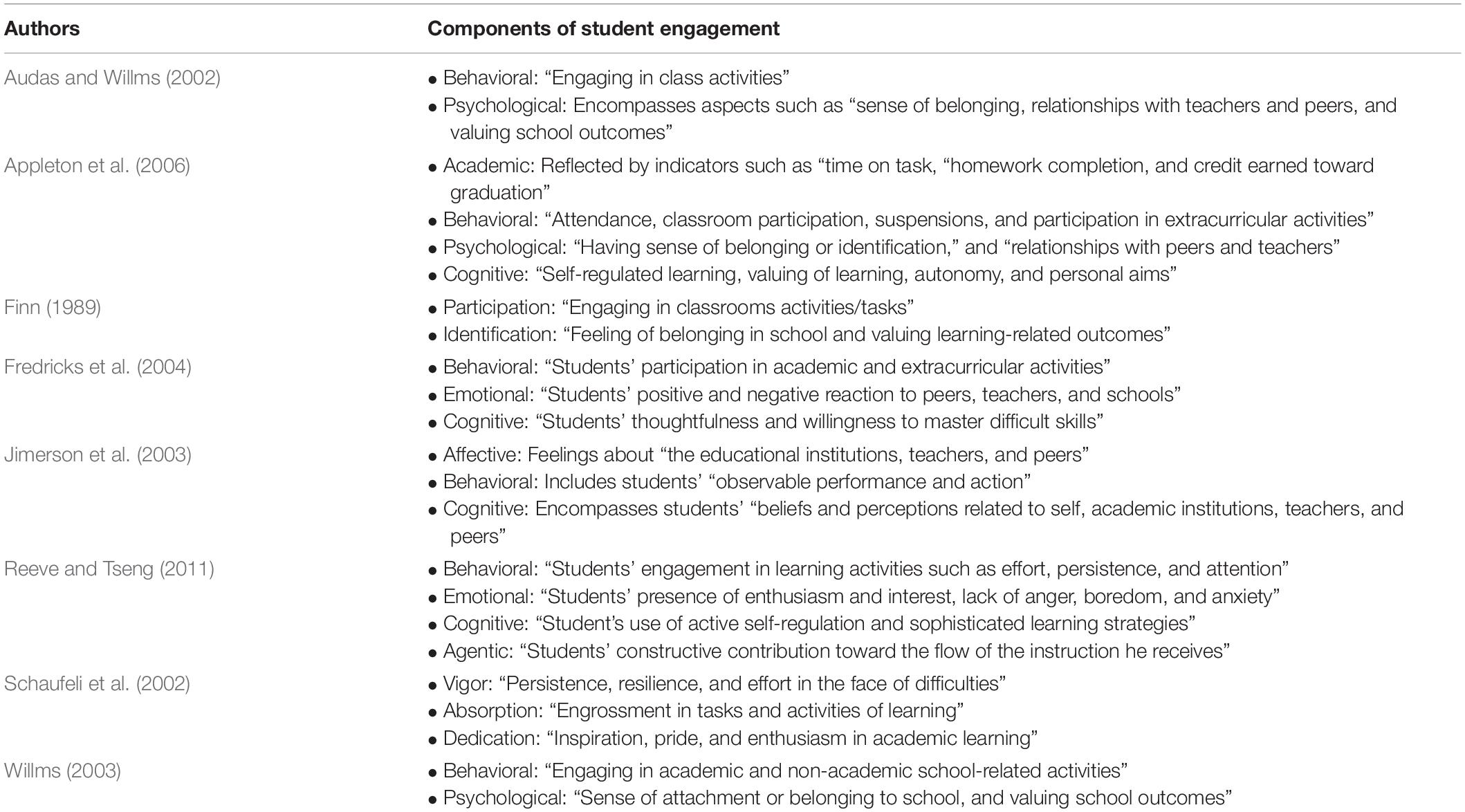

As shown in Table 1, similar to the definition and scope of student engagement, there is debate over the types and number of its components (Appleton et al., 2008; Li and Lerner, 2011). For instance, Schaufeli et al. (2002) divided student engagement into three components of “Vigor,” “Absorption,” and “Dedication,” as opposed to Appleton et al. (2006) who categorized this concept across four dimensions of “Academic,” “Behavioral,” “Psychological,” and “Cognitive.”

As put forward by many scholars (e.g., Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro, 2013; Salmela-Aro and Upadyaya, 2014; Alrashidi et al., 2016; Hiver et al., 2021), among different models of student engagement, the models of Schaufeli et al. (2002) and Fredricks et al. (2004) have received more attention in realizing and explaining the complex nature of the student engagement construct.

Previous empirical studies have examined the construct of student academic engagement from various angles, namely as a means of improving learning outcomes (Parsons et al., 2014; Wonglorsaichon et al., 2014; Virtanen et al., 2015), a way of minimizing school dropout (Janosz et al., 2008), and an indicator of student academic motivation (Akpan and Umobong, 2013; Wu, 2019; Ghanizadeh et al., 2020; Ghelichli et al., 2020; Muñoz-Restrepo et al., 2020).

The Role of Teacher Confirmation and Stroke in EFL/ESL Students’ Motivation and Academic Engagement

Compared to other positive interpersonal behaviors of language teachers, confirmation and stroke have been the focus of less empirical research. However, the available literature on language teacher confirmation and stroke reported valuable findings regarding the impact of these interpersonal behaviors on EFL/ESL student-related variables, notably student motivation and academic engagement.

With regard to EFL/ESL student motivation, Ellis (2009) found that language teacher confirmation directly affects student motivation to learn the language. Similarly, Goodboy and Myers (2008) reported a positive association between language teachers’ confirmation behaviors and students’ state and trait motivation. As far as teacher stroke is concerned, Amini et al. (2019) found a statistically significant relationship between teacher stroke and EFL students’ increased motivation. By the same token, Pishghadam and Khajavy (2014) uncovered that teacher stroke can remarkably predict EFL students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to learn the language. In the same vein, Croucher et al. (2021) demonstrated that ESL students’ level of academic motivation can be dramatically enhanced by teacher confirmation behaviors.

Concerning EFL/ESL student academic engagement, Campbell et al. (2009) showed that language teacher confirmation can lead to higher student motivation in EFL/ESL classes. Similarly, Waldbuesser (2019) found that a positive relationship exists between language teacher confirmation and student academic engagement. When it comes to teacher stroke, Van Uden et al. (2014) reported that language teacher stroke is directly associated with students’ higher engagement. In this regard, Baños et al. (2019) also demonstrated that language teachers can increase students’ academic engagement in a stroke-rich instructional context.

The empirical evidence on the role of teacher confirmation and stroke in enhancing EFL/ESL students’ motivation and academic engagement can be justified by the “rhetorical-relational goal theory” (Mottet et al., 2006). This theory is grounded on the following key premises (Myers et al., 2018, p. 2):

• Teachers have some relational and rhetorical goals.

• Students have some relational and academic needs and wants.

• Effective teaching is the consequence of defining proper rhetorical and relational goals and employing effective interpersonal behaviors to obtain those goals.

• Students who feel more satisfied in the instructional-learning environment and whose relational and academic expectations, needs, and wants are addressed, are more inclined to engage in the learning process.

• Grade levels and instructional contexts influence teachers’ relational and rhetorical goals.

• Students’ relational and academic needs and desires differ across different phases of development.

According to the aforementioned assumptions of rhetorical-relational goal theory, it can be reasonably inferred that teachers can fulfill students’ academic needs and wants through employing positive interpersonal behaviors, which in turn result in some favorable consequences such as increased motivation and academic engagement (Houser and Hosek, 2018).

The predictability of EFL/ESL students’ motivation and academic engagement through teacher confirmation and stroke have also something to do with “positive psychology” (Seligman, 2018; Dewaele et al., 2019; Li and Xu, 2019). Positive psychology is founded on three core elements, including “positive experiences,” “positive individual traits,” and “positive institutions” (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 9). This school of thought posits that positive interaction between teachers and students provides an appropriate instructional-learning environment in which students enjoy their learning experiences (MacIntyre et al., 2016; Budzińska and Majchrzak, 2021). As put forward by Seligman (2011), enjoying the learning process is a key factor in promoting student-related outcomes such as academic engagement and motivation.

Discussion

In this theoretical review, two prime instances of positive interpersonal behaviors (i.e., confirmation and stroke), their underlying frameworks (i.e., broaden-and-build theory, emotional response theory, and transactional analysis), and their associations with two favorable student-related outcomes (i.e., motivation and academic engagement) were explained. Furthermore, two critical theoretical frameworks (i.e., rhetorical-relational goal theory and positive psychology) that support the connections among the aforementioned variables were fully described.

According to what was theoretically reviewed, it appears that this research area has some pedagogical implications for teacher trainers, educational supervisors, and pre- and in-service language teachers. For instance, teacher trainers should alter teachers’ attitudes and perceptions toward their educational responsibilities. To put it simply, they should make teachers aware that their responsibilities in instructional-learning environments are beyond the transmission of content and pedagogical knowledge. That is, teachers must be equipped with the knowledge that the interpersonal behaviors they employ in interaction with their students (e.g., confirmation and stroke) are as important as their knowledge and instructional skills.

Moreover, educational supervisors who are responsible for observing teachers and evaluating their academic effectiveness can take some advantage of research evidence in the area of the positive teacher-student relationships. Given the pivotal role of teachers’ interpersonal behaviors in the adequacy of instruction and learning, besides teacher competence and instructional skills, supervisors should also take interpersonal behaviors into account as other essential dimensions of teacher success. Last but by no means the least, both pre- and in-service language teachers should enhance their effectiveness by pursuing recent studies on effective interpersonal behaviors of teachers, attending different related conferences and workshops, and evaluating their own interpersonal behaviors. In light of new information, language teachers should make necessary changes in the interpersonal behaviors they employ in interactions with their EFL/ESL students.

Finally, a number of important limitations need to be noted regarding the available literature on teacher confirmation and stroke. To start with, compared to other positive interpersonal behaviors, teacher confirmation and stroke have received less attention (e.g., Sidelinger and Booth-Butterfield, 2010; Hsu, 2012); hence, more empirical studies should be conducted on these two interpersonal behaviors. Next, previous research proved that teacher confirmation and stroke play a pivotal role in improving student motivation and academic engagement (Van Uden et al., 2014; LaBelle and Johnson, 2020; Croucher et al., 2021); it would be interesting to examine whether other student-related variables (e.g., learning achievement, willingness to communicate, satisfaction, etc.) can be positively predicted by teacher confirmation and stroke.

Moreover, almost all previous studies employed a quantitative method to examine the interplay of language teacher confirmation and stroke with respect to student motivation and academic engagement. What is now needed is to examine the inter-relationships of these variables through qualitative and mixed-method approaches that offer a more detailed understanding of the subject under inquiry (Patton, 2015; Ary et al., 2018). Furthermore, the questionnaire was the sole instrument employed in these studies. For the sake of triangulation, future studies can employ other data collection instruments such as interviews, observation schemes, and diary writing. Additionally, the majority of the existing literature has been carried out in EFL contexts. As such, future research needs to be conducted to uncover the extent to which the association among the aforementioned variables is present in ESL instructional-learning contexts.

A further limitation of the available literature deals with the measurement of teacher interpersonal variables. That is, the majority of studies merely used observer-report scales to measure teacher stroke and confirmation. Hence, the attitudes and perceptions of teachers toward their interpersonal behaviors were neglected. To fill this gap, further empirical studies are advised to use both observer-report scales and self-report scales to measure these two interpersonal behaviors of teachers. Last but not least, the moderating effects of situational variables such as gender (Campbell et al., 2009) and culture (Shen and Croucher, 2018; Croucher et al., 2021) have been the focus of less research. In this regard, more empirical research is highly required to examine the impact of different situational variables.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Akin-Little, K. A., Eckert, T. L., Lovett, B. J., and Little, S. G. (2004). Extrinsic reinforcement in the classroom: Bribery or best practice. School Psychol. Rev. 33, 344–362. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2004.12086253

Akpan, I. D., and Umobong, M. E. (2013). Analysis of achievement motivation and academic engagement of students in the Nigerian classroom. Acad. J. Interdiscipl. Stud. 2:385. doi: 10.5901/ajis.2013.v2n3p385

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., and Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: An overview of its definitions, dimensions, and major Conceptualizations. Int. Educat. Stud. 9, 41–52. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n12p41

Amini, A., Pishghadam, R., and Saboori, F. (2019). On the role of language learners’ psychological reactance, teacher stroke, and teacher success in the Iranian context. J. Res. Appl. Linguist. 10, 25–43. doi: 10.22055/RALS.2019.14716

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., and Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol. Schools 45, 369–386. doi: 10.1002/pits.20303

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., and Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. J. School Psychol. 44, 427–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Irvine, C. K. S., and Walker, D. (2018). Introduction to research in education. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Audas, R., and Willms, J. D. (2002). Engagement and dropping out of school: A life-course perspective. Canada: HRDC Publications Centre.

Babonea, A., and Munteanu, A. (2012). “Towards positive interpersonal relationships in the classroom,” in Paper presented at international conference of scientific paper. Brasov, Romania, (Greece: WSEAS).

Baños, J. H., Noah, J. P., and Harada, C. N. (2019). Predictors of student engagement in learning communities. J. Med. Educat. Curricul. Dev. 6:2382120519840330. doi: 10.1177/2382120519840330

Berne, E. (1988). Games people play: The psychology of human relationships. New York, NY: Grove Press.

Berne, E., Stroie, L., and Gheorghe, N. (2011). Analiza tranzactionala in psihoterapie. Bucuresti: EdituraTrei.

Brinkworth, M. E., MacIntyre, J., Juraschek, A. D., and Gehlbach, H. (2018). Teacher-student relationships: The positives and negatives of assessing both perspectives. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 55, 24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.09.002

Budzińska, K., and Majchrzak, O. (2021). Positive psychology in second and foreign language education. New York, NY: Springer.

Campbell, L. C., Eichhorn, K. C., Basch, C., and Wolf, R. (2009). Exploring the relationship between teacher confirmation, gender, and student effort in the college classroom. Hum. Commun. 12, 447–464.

Carter, C. P., Reschly, A. L., Lovelace, M. D., Appleton, J. J., and Thompson, D. (2012). Measuring student engagement among elementary students: Pilot of the student engagement instrument—elementary version. School Psychol. Quart. 27, 61–73. doi: 10.1037/a0029229

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., Appleton, J. J., Berman, S., Spanjers, D., and Varro, P. (2008). “Best practices in fostering student engagement,” in Best practices in school psychology, eds A. Thomas and J. Grimes (Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists), 1099–1120.

Croucher, S. M., Rahmani, D., Galy-Badenas, F., Zeng, C., Albuquerque, A., Attarieh, M., et al. (2021). “Exploring the relationship between teacher confirmation and student motivation: The United States and Finland,” in Intercultural competence past, present and future, eds M. D. López-Jiménez and J. Sánchez-Torres (Singapore: Springer), 101–120. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-8245-5_5

Derakhshan, A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ nonverbal immediacy and credibility. J. Teaching Persian Speakers Other Lang. 10, 3–26.

Derakhshan, A., Saeidi, M., and Beheshti, F. (2019). The interplay between Iranian EFL teachers’ conceptions of intelligence, care, feedback, and students’ stroke. IUP J. English Stud. 14, 81–98.

Dewaele, J. M., Chen, X., Padilla, A. M., and Lake, J. (2019). The flowering of positive psychology in foreign language teaching and acquisition research. Front. Psychol. 10:2128. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02128

Dobrescu, T., and Lupu, G. S. (2015). The role of nonverbal communication in the teacher-pupil relationship. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 180, 543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.157

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ellis, K. (2000). Perceived teacher confirmation: The development and validation of an instrument and two studies of the relationship to cognitive and affective learning. Hum. Communicat. Res. 26, 264–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00758.x

Ellis, K. (2004). The impact of perceived teacher confirmation on receiver apprehension, motivation, and learning. Communicat. Educat. 53, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/0363452032000135742

Ellis, R. (2009). A Reader responds to Guilloteaux and Dörnyei’s “Motivating Language Learners: A Classroom−Oriented Investigation of the Effects of Motivational Strategies on Student Motivation”. TESOL Quart. 43, 105–109. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00229.x

Fallah, N. (2014). Willingness to communicate in English, communication self-confidence, motivation, shyness and teacher immediacy among Iranian English-major undergraduates: A structural equation modeling approach. Learn. Individ. Differen. 30, 140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.12.006

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from School. Rev. Educat. Res. 59:117. doi: 10.3102/00346543059002117

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educat. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Gabryś-Barker, D., and Gałajda, D. (eds) (2016). Positive psychology perspectives on foreign language learning and teaching. New York, NY: Springer.

Gałajda, D., Zakrajewski, P., and Pawlak, M. (eds) (2016). Researching second language learning and teaching from a psycholinguistic perspective: Studies in honor of Danuta Gabryś-Barker. New York, NY: Springer.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Geier, M. T. (2020). The teacher behavior checklist: The mediation role of teacher behaviors in the relationship between the students’ importance of teacher behaviors and students’ effort. Teach. Psychol. 2020:0098628320979896. doi: 10.1177/0098628320979896

Ghanizadeh, A., Amiri, A., and Jahedizadeh, S. (2020). Towards humanizing language teaching: Error treatment and EFL learners’ cognitive, behavioral, emotional engagement, motivation, and language achievement. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 8, 129–149.

Ghelichli, Y., Seyyedrezaei, S. H., Barani, G., and Mazandarani, O. (2020). The relationship between dimensions of student engagement and language learning motivation among Iranian EFL learners. Int. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 8, 43–57. doi: 10.5565/rev/jtl3.803

Goldman, Z. W., and Goodboy, A. K. (2014). Making students feel better: Examining the relationships between teacher confirmation and college students’ emotional outcomes. Communic. Educat. 63, 259–277. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2014.920091

Goldman, Z. W., Bolkan, S., and Goodboy, A. K. (2014). Revisiting the relationship between teacher confirmations and learning outcomes: Examining cultural differences in Turkish, Chinese, and American classrooms. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 43, 45–63. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2013.870087

Goldman, Z. W., Claus, C. J., and Goodboy, A. K. (2018). A conditional process analysis of the teacher confirmation–student learning relationship. Commun. Quart. 66, 245–264. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2017.1356339

Goodboy, A. K., and Myers, S. A. (2008). The effect of teacher confirmation on student communication and learning outcomes. Commun. Educat. 57, 153–179. doi: 10.1080/03634520701787777

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educat. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Henry, A., and Thorsen, C. (2018). Teacher–student relationships and L2 motivation. Modern Lang. J. 102, 218–241. doi: 10.1111/modl.12446

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., and Mercer, S. (eds) (2021). Student engagement in the language classroom. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Houser, M. L., and Hosek, A. M. (eds) (2018). Handbook of instructional communication: Rhetorical and relational perspectives, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hsu, C. F. (2012). The influence of vocal qualities and confirmation of nonnative English-speaking teachers on student receiver apprehension, affective learning, and cognitive learning. Commun. Educat. 61, 4–16. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2011.615410

Hsu, C. F., and Huang, I. (2017). Are international students quiet in class? The influence of teacher confirmation on classroom apprehension and willingness to talk in class. J. Int. Students 7, 38–52. doi: 10.32674/jis.v7i1.244

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., and Pagani, L. S. (2008). School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. J. Soc. Iss. 64, 21–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00546.x

Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., and Greif, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. Califor. School Psychol. 8, 7–27. doi: 10.1007/bf03340893

Katt, J. A., and Condly, S. J. (2009). A preliminary study of classroom motivators and de-motivators from a motivation-hygiene perspective. Commun. Educat. 58, 213–234. doi: 10.1080/03634520802511472

LaBelle, S., and Johnson, Z. D. (2020). The relationship of student-to-student confirmation and student engagement. Commun. Res. Rep. 37, 234–242. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2020.1823826

Lamborn, S., Newmann, F., and Wehlage, G. (1992). “The significance and sources of student engagement,” in Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools, ed. F. Newmann (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 11–39.

Lei, H., Cui, Y., and Zhou, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 46, 517–528. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7054

Li, C., and Xu, J. (2019). Trait emotional intelligence and classroom emotions: A positive psychology investigation and intervention among Chinese EFL learners. Front. Psychol. 10:2453. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02453

Li, Y., and Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Dev. Psychol. 47, 233–247. doi: 10.1037/a0021307

Luo, Y., Deng, Y., and Zhang, H. (2020). The influences of parental emotional warmth on the association between perceived teacher–student relationships and academic stress among middle school students in China. Childr. Youth Serv. Rev. 114:105014. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105014

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (eds) (2016). Positive psychology in SLA. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Martin, A. J., and Collie, R. J. (2019). Teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement in high school: Does the number of negative and positive relationships with teachers matter? J. Educat. Psychol. 111, 861–876. doi: 10.1037/edu0000317

Mottet, T. P., and Beebe, S. A. (2006). The relationships between student responsive behaviors, student socio-communicative style, and instructors’ subjective and objective assessments of student work. Commun. Educat. 55, 295–312. doi: 10.1080/03634520600748581

Mottet, T. P., Frymier, A. B., and Beebe, S. A. (2006). “Theorizing about instructional communication,” in Handbook of instructional communication: Rhetorical and relational perspectives, eds T. P. Mottet, V. P. Richmond, and J. C. McCroskey (Boston: Allyn & Bacon), 255–282.

Muñoz-Restrepo, A., Ramirez, M., and Gaviria, S. (2020). Strategies to enhance or maintain motivation in learning a foreign language. Profile Iss. Teachers Profess. Dev. 22, 175–188. doi: 10.15446/profile.v22n1.73733

Myers, S. A., Baker, J. P., Barone, H., Kromka, S. M., and Pitts, S. (2018). Using rhetorical/relational goal theory to examine college students’ impressions of their instructors. Commun. Res. Rep. 35, 131–140. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2017.1406848

Nayernia, A., Taghizadeh, M., and Farsani, M. A. (2020). EFL teachers’ credibility, nonverbal immediacy, and perceived success: A structural equation modelling approach. Cogent Educat. 7:1774099. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2020.1774099

Newell, S., and Jeffery, D. (2002). Behavior management in the classroom. A transactional analysis approach. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Parsons, S. A., Nuland, L. R., and Parsons, A. W. (2014). The ABCs of student engagement. Phi Delta Kapp. 95, 23–27. doi: 10.1177/003172171409500806

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Sage.

Pekrun, R., and Schutz, P. A. (2007). Where do we go from here? Implications and future directions for inquiry on emotions in education. Cambridge: Academic Press., 313–331. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-372545-5.X5000-X

Phan, H. P. (2014). An integrated framework involving enactive learning experiences, mastery goals, and academic engagement-disengagement. Eur. J. Psychol. 10, 41–66. doi: 10.23668/psycharchives.1071

Pishghadam, R., and Khajavy, G. H. (2014). Development and validation of the student stroke scale and examining its relation with academic motivation. Stud. Educat. Evaluat. 43, 109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.03.004

Pishghadam, R., Derakhshan, A., and Zhaleh, K. (2019). The interplay of teacher success, credibility, and stroke with respect to EFL students’ willingness to attend classes. Polish Psychol. Bull. 50, 284–292. doi: 10.24425/ppb.2019.131001

Pishghadam, R., Derakhshan, A., Zhaleh, K., and Al-Obaydi, L. H. (2021). Students’ willingness to attend EFL classes with respect to teachers’ credibility, stroke, and success: A cross-cultural study of Iranian and Iraqi students’ perceptions. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01738-z

Rajabnejad, F., Pishghadam, R., and Saboori, F. (2017). On the influence of stroke on willingness to attend classes and foreign language achievement. Appl. Res. Engl. Lang. 6, 141–158. doi: 10.22108/ARE.2017.21344

Reeve, J., and Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemp. Educat. Psychol. 36, 257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M., Spilt, J. L., and Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Rev. Educat. Res. 81, 493–529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

Salmela-Aro, K., and Upadyaya, K. (2014). School burnout and engagement in the context of demands–resources model. Br. J. Educat. Psychol. 84, 137–151. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12018

Santana, C. A. D. S. N. (2017). Affect: What is teacher confirmation and what effect does it have on learning?. Ph. D. thesis. Portugal: NOVA University Lisbon.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happin. Stud. 3, 71–92.

Schrodt, P., and Finn, A. N. (2011). Students’ perceived understanding: An alternative measure and its associations with perceived teacher confirmation, verbal aggressiveness, and credibility. Commun. Educat. 60, 231–254. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2010.535007

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Atria.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018:1437466. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466

Seligman, M. E. P., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14.

Shen, T., and Croucher, S. M. (2018). A cross-cultural analysis of teacher confirmation and student motivation in China, Korea, and Japan. J. Intercult. Commun. 47, 1404–1634.

Sidelinger, R. J., and Booth-Butterfield, M. (2010). Co-constructing student involvement: An examination of teacher confirmation and student-to-student connectedness in the college classroom. Commun. Educat. 59, 165–184. doi: 10.1080/03634520903390867

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., and Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educat. Psychol. Measurem. 69, 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0013164408323233

Stewart, I., and Joines, V. (1987). TA today: A new introduction to transactional analysis. Nottingham: Life space.

Sun, X., Pennings, H. J., Mainhard, T., and Wubbels, T. (2019). Teacher interpersonal behavior in the context of positive teacher-student interpersonal relationships in East Asian classrooms: Examining the applicability of western findings. Teaching Teacher Educat. 86:102898. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102898

Tranca, L. M., and Neagoe, A. (2018). The importance of positive language for the quality of interpersonal relationships. Agora Psycho Pragmat. 12, 69–77.

Upadyaya, K., and Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Engagement with studies and work: Trajectories from post comprehensive school education to higher education and work. Emerg. Adulth. 1, 247–257. doi: 10.1177/2167696813484299

Ushioda, E. (2008). “Motivation and good language learners,” in Lessons from good language learners, ed. C. Griffiths (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 19–34. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511497667.004

Van Uden, J. M., Ritzen, H., and Pieters, J. M. (2014). Engaging students: The role of teacher beliefs and interpersonal teacher behavior in fostering student engagement in vocational education. Teaching Teacher Educat. 37, 21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.08.005

Virtanen, T. E., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., and Kuorelahti, M. (2015). The relationship between classroom quality and students’ engagement in secondary school. Educat. Psychol. 35, 963–983. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.822961

Waldbuesser, C. (2019). Extending Emotional Response Theory: Testing a model of teacher communication behaviors, student emotional processes, student academic resilience, student engagement, and student discrete emotions. Ph. D. thesis. Athens: Ohio University.

Wei, M., Zhou, Y., Barber, C., and Den Brok, P. (2015). Chinese students’ perceptions of teacher–student interpersonal behavior and implications. System 55, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2015.09.007

Wendt, J. L., and Courduff, J. (2018). The relationship between teacher immediacy, perceptions of learning, and computer-mediated graduate course outcomes among primarily Asian international students enrolled in an US university. Int. J. Educat. Technol. Higher Educat. 15, 1–15.

Willms, J. D. (2003). Student engagement at school: A sense of belonging and participation. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Wonglorsaichon, B., Wongwanich, S., and Wiratchai, N. (2014). The influence of students’ school engagement on learning achievement: A structural equation modeling analysis. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 116, 1748–1755. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.467

Wu, Z. (2019). Academic motivation, engagement, and achievement among college students. Coll. Stud. J. 53, 99–112.

Yu, T. M., and Zhu, C. (2011). Relationship between teachers’ preferred teacher–student interpersonal behavior and intellectual styles. Educat. Psychol. 31, 301–317. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2010.548116

Zhang, Q. (2011). Teacher immediacy, credibility, and clarity as predictors of student affective learning: A Chinese investigation. China Media Res. 7, 95–104.

Zhang, Q., and Sapp, D. A. (2013). Psychological reactance and resistance intention in the classroom: Effects of perceived request politeness and legitimacy, relationship distance, and teacher credibility. Commun. Educat. 62, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2012.727008

Zhao, Y., Zheng, Z., Pan, C., and Zhou, L. (2021). Self-esteem and academic engagement among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12:690828. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.690828

Zhao, Z., Broström, A., and Cai, J. (2020). Promoting academic engagement: University context and individual characteristics. J. Technol. Transfer 45, 304–337. doi: 10.1007/s10961-018-9680-6

Zhong, Q. M. (2013). Understanding Chinese learners’ willingness to communicate in a New Zealand ESL classroom: A multiple case study drawing on the theory of planned behavior. System 41, 740–751. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2013.08.001

Keywords: theoretical review, confirmation, stroke, language teacher, motivation, academic engagement, EFL/ESL students

Citation: Gao Y (2021) Toward the Role of Language Teacher Confirmation and Stroke in EFL/ESL Students’ Motivation and Academic Engagement: A Theoretical Review. Front. Psychol. 12:723432. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723432

Received: 10 June 2021; Accepted: 28 June 2021;

Published: 19 July 2021.

Edited by:

Ali Derakhshan, Golestan University, IranReviewed by:

Liqaa Habeb Al-Obaydi, University of Diyala, IraqSaeed Khazaie, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2021 Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yun Gao, bWFnZ2llMTk4MzExNUAxNjMuY29t

Yun Gao

Yun Gao