- 1School of Physical Education and Sports Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Education, Faculty of Education Sciences, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

- 3SPORT Research Group (CTS-1024), University of Almería, Almería, Spain

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of high (HPBPT) and low percentage ball possession teams (LPBPT) on physical and technical-tactical performance indicators in the Chinese Football Super League (CSL). Eight physical performance indicators and 26 technical-tactical performance indicators from all 240 matches from season 2018 were analyzed, as well as three contextual variables (team strength, quality of opposition, and match location). Players were divided according to five positions: fullbacks, central defenders, wide midfielders, central midfielders, and attackers. A k-means cluster analysis was conducted to classify all match observations into two groups: HPBPT (n = 229) and LPBPT (n = 251). A mixed linear model was fitted with contextual variables as covariates. When significant interactions or main effects were detected, a post hoc comparison was used to compare physical and technical/tactical differences between HPBPT and LPBPT. Results showed that central defenders and fullbacks covered more high-intensity and sprint running distance in the high possession teams, while wide midfielders and forward covered more high-intensity and sprint running distance in the low possession teams. Meanwhile, players from high ball possession teams were strong in technical indicators, especially in attacking organization. These results may help coaches to understand current football development trends and develop suitable training plans and tests for elite football players.

Introduction

Possession in football is a basic and important performance indicator (Pollard and Reep, 1997). Currently, ball possession is a trending topic that is heatedly discussed because of the success of possession-play teams in the World Cup and European Champions league. In the English Premier League, it was found that the best and most successful teams record longer possessions (Jones et al., 2004; Bloomfield et al., 2005; Carling et al., 2005). Additionally, in La Liga (Spanish League), possession was found to be a strong indicator in predicting the winning team (Lago-Peñas and Dellal, 2010; Lago-Peñas et al., 2010), and in the Chinese Super League (CSL), higher ranked teams were associated with high ball possession (Liu et al., 2019).

Possession is very much related to ball control and playing style. There are traditionally two typical playing styles that are most commonly described: (a) direct play and (b) possession play (Bate, 1988; Hughes and Franks, 2005; Lago-Peñas and Dellal, 2010; Kempe et al., 2014). A direct playing team may have less possession on the pitch, and their players tend to play more in counterattack (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Tenga and Sigmundstad, 2011; Fernandez-Navarro et al., 2016). In contrast, a possession playing team will keep the ball for a long time (Kempe et al., 2014), and their players tend to want the ball close to the goal to minimize giving ball control to their opponent. Common beliefs are that Spanish football styles involve possession play and English styles involve more direct play (Sarmento et al., 2013), but recent studies have found that mixed play strategies also work during the match Jones et al. (2004). Different playing styles are rooted in different football philosophies, and each playing style has led to great achievements in history and is still being discussed today (Hughes and Franks, 2005; Sarmento et al., 2013; Yi et al., 2019). Bloomfield et al. (2005) found in three elite English clubs that “all were possession dominant, some already absorbed pressure and adopted a counterattacking strategy.” In addition, in 2018, World Cup teams that entered the top 16 mostly used mixed playing styles (Yi et al., 2019).

Since high and low ball possession typically represent different playing styles that are related to different playing variables (Hewitt et al., 2016), previous researchers have found that high or low ball possession had an impact on technical-tactical and physical performance indicators (Bradley et al., 2013b; da Mota et al., 2016). Technically, high possession teams tend to have longer ball control and more passes (Tenga et al., 2010a), while low possession teams have less ball control and fewer passes. It was expected that physical performance indicators would be affected by high and low possession because playing against high-quality opponents has been linked to lower ball possession (Bloomfield et al., 2005; Lago, 2009), and it is possible for such teams to run more at high intensity to regain the ball (Di Salvo et al., 2009; Bradley et al., 2013b). However, there is also evidence that suggests the opposite is true (Bradley et al., 2013b; da Mota et al., 2016).

In addition to the effects of ball possession, player role was found to be another important variable. Performance indicators are different for different playing positions. Several studies have already focused on technical-tactical and physical profiles for playing positions (Di Salvo et al., 2009; Dellal et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016). From a physical point of view, wide midfielders were reported to cover the greatest distances at high intensity compared to other positions (Bradley et al., 2009; Di Salvo et al., 2009; Mallo et al., 2015). Moreover, technically, center midfielders made more passes than forward and central defenders (Taylor et al., 2004; Redwood-Brown et al., 2012). However, separate analyses for technical-tactical and physical indicators are not adequate because team performance in a real match is affected by interacting performance indicators, which warrant more complex studies.

The exploration of the relationship between playing style (related to ball possession) and player performance, also linked to player role (Fernandez-Navarro et al., 2016; Yi et al., 2019), is still an important and suitable indicator that is popularly used to evaluate performance (Bradley et al., 2013b; da Mota et al., 2016) and identify the best teams at the top level (Lago, 2009; Yang et al., 2018). Although there was an early study that did not support possession play (Bate, 1988), it still stated the importance of entering attacking third zones and therefore creating a chance of scoring (Bate, 1988). Indeed, there is evidence that high possession teams have a greater chance of attacking third and opposition penalty areas (Tenga et al., 2010a; da Mota et al., 2016). Moreover, contextual variables like team strength, quality of opposition and match location are also important (Lago-Peñas and Dellal, 2010; Bradley et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2021) because they also influence the team’s playing style (Fernandez-Navarro et al., 2018) and players’ performance. Currently, most studies are centered on European leagues and the World Cup, while there is still a knowledge gap with respect to the CSL. This football league is growing quickly and its performance evolution has progressed rapidly (Zhou et al., 2020). Although the CSL has received considerable attention in the last few years (Gai et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019), most studies are focusing on an analysis of performance indicators with a lack of discussion on CSL teams’ playing styles. Considering the great evolution of football play in this decade and ball possession as a representative indicator of the playing style, this study aims to analyze the impact of ball possession on physical and technical-tactical indicators in terms of playing position in the CSL.

Materials and Methods

Samples and Variables

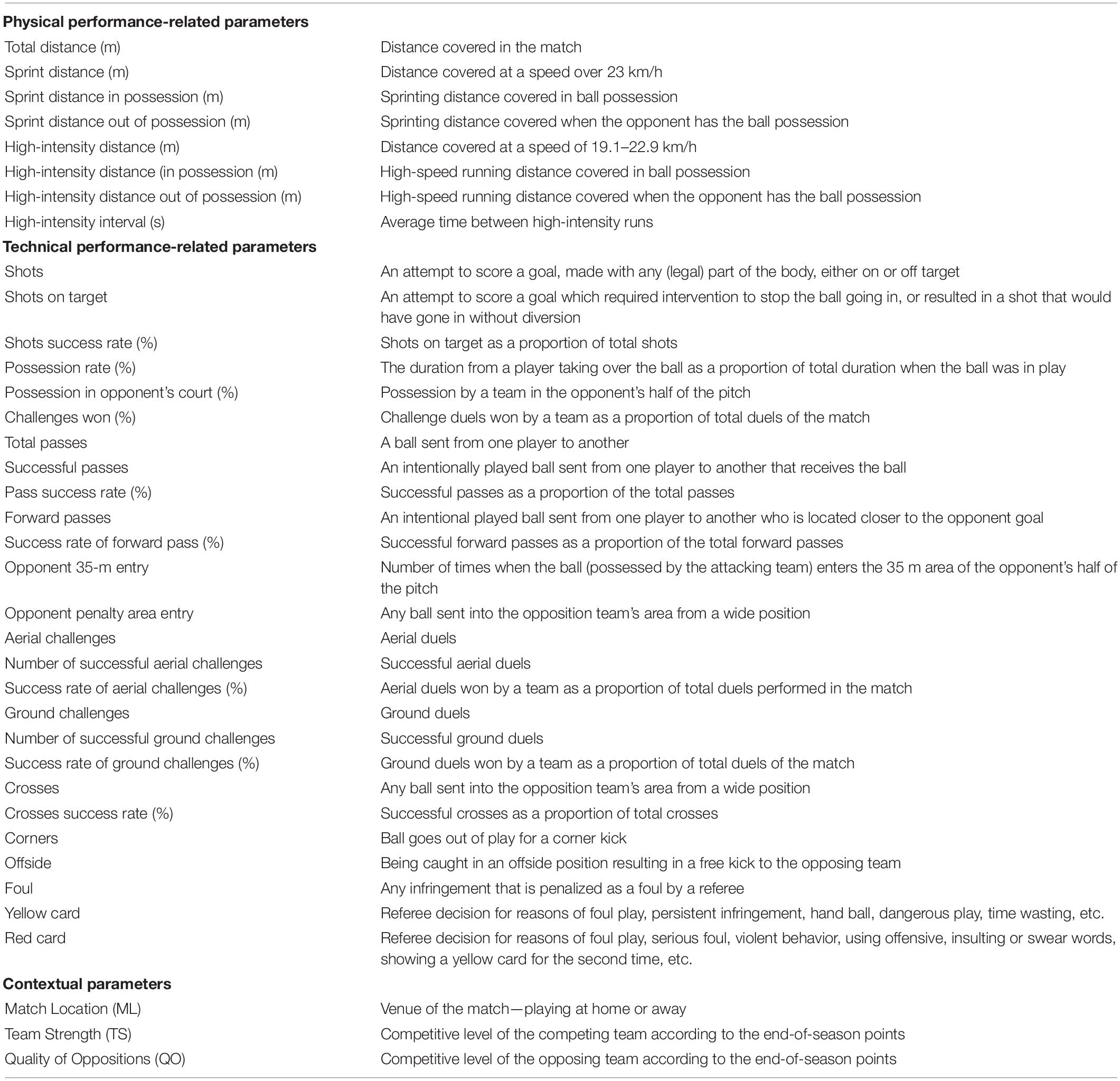

Data were collected from all the matches (n = 240) played in the CSL during the 2018 season. A total of 16 teams participated in this competition, playing 30 matches each in a balanced home and away schedule (15 home and 15 away matches). Players were divided according to five positions as in previous studies (Bush et al., 2015a,b): fullbacks (n = 1,120), central defenders (n = 1,072), wide midfielders (n = 1,404), central midfielders (n = 1,669), and attackers (n = 898). Match data on goalkeepers were excluded because of the specificity of this position; hence, 6,163 match observations were included. Based on previous studies (Bradley et al., 2009; Di Salvo et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2016, 2019, 2021; Gai et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018, 2020; Gong et al., 2021), eight physical performance indicators and 26 technical-tactical performance indicators as well as three contextual variables (team strength - TS-, quality of opposition -QO- and match location -ML-) were analyzed (Table 1). Player position and ball possession were also measured. This study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013).

Procedure

Team performance data were originated from Amisco® Sports Analysis Services, and these data were ordered in specific spreadsheets. During the observation procedure, the movements of all field players in each match were tracked by eight stable and synchronized cameras positioned at the top of the stadium at a sampling frequency of 25 measures a second. Signals and angles obtained by the encoders were sequentially converted into digital data and recorded on six computers for post-match analyses. From the stored data, the distance covered, time spent in the different movement categories, and the frequency of occurrence for each activity were determined by Athletic Mode Amisco® Pro, Nice, France (Di Salvo et al., 2007). The reliability of this data source and collection methods were previously validated and used by many studies (Lago-Peñas et al., 2009; Zubillaga et al., 2009; Dellal et al., 2011; Castellano et al., 2014; Valter et al., 2017).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD), were calculated for each variable. To establish whether a team was in high or low ball possession during a match, a cluster K-means analysis (Schwartz’s Bayesian) was taken based on the team’s ball possession in every match across the whole season (Bradley et al., 2013b; da Mota et al., 2016). The average ball possession in a high ball possession team (HPBPT) was 56.53 ± 4.22% (range of 51–69%; n (229), and in a low ball possession team (LPBPT), was 43.98% (±4.44% (range of 31–%-50%; n = 251).

Finally, a mixed linear model was fitted in which team strength (TS), Quality of Opposition (QO), and Match Location (ML) were used as covariates. When significant interactions or main effects were detected, a post hoc comparison was used to compare physical and technical/tactical differences between HPBPT and LPBPT. All analyses were conducted using lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) and emmeans (Russell, 2021) packages in statistical software R (ver. 4.1.1) (R Core Team, 2021) with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Physical Performance

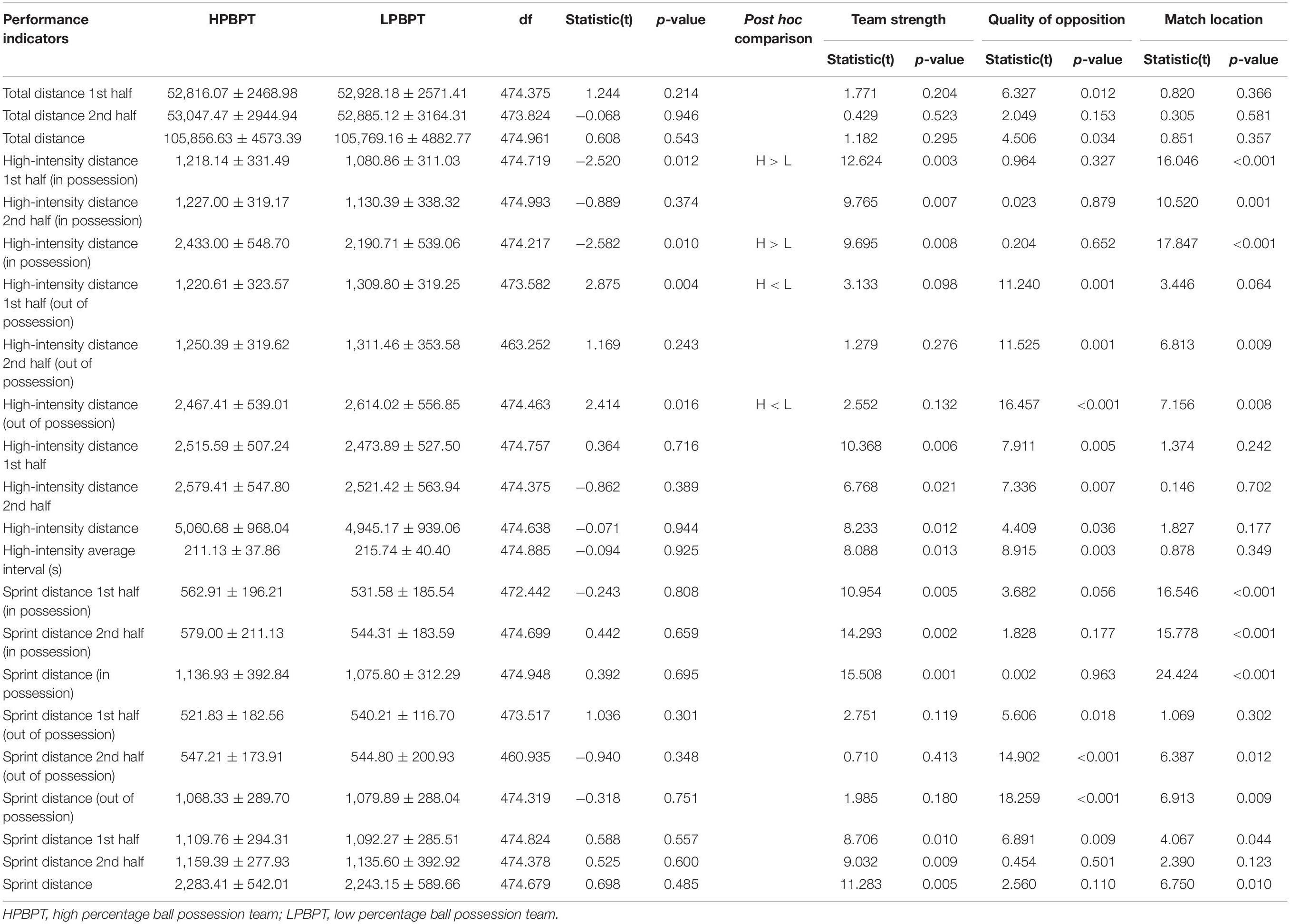

The physical performances of HPBPT and LPBPT are shown in Table 2. The high-intensity distance (first half and total) in ball possession were higher in HPBPT than in LPBPT (p < 0.05). When the ball was out of possession, high-intensity running (first half and total) of HPBPT was lower than that of LPBPT (p < 0.05). No other differences were observed for other running indicators between HPBPT and LPBPT. As covariates, TS had a major influence on high speed running in possession, QO had a major influence on high speed running out of possession, and ML influenced high speed performance both in and out of possession.

Table 3 illustrates the running indicators across playing positions in HPBPT and LPBPT. HPBPT fullbacks covered more high-intensity running (second half and total) and sprint distance (second half and total) than fullbacks in LPBPT (p < 0.05). Central defenders of HPBPT covered more high intensity distance (second half and total) and sprint distance (second half and total), as well as less high-intensity average intervals than central defenders in LPBPT (p < 0.05). However, wide midfielders of HPBPT covered less high-intensity running (second half, total) and sprint distance (second half and total) and more high-intensity average intervals than wide midfielders in LPBPT (p < 0.05). Additionally, attackers of HPBPT covered less high-intensity running (first half, second half, and total) and sprint distance (first half, second half, and total) than their LPBPT counterparts (p < 0.05). No differences were observed for central midfielders between HPBPT and LPBPT. As covariates, in general, QO influenced the high speed performance of fullbacks and central backs, and ML had an impact on the high speed running of wide midfielders and attackers.

Technical-Tactical Performance

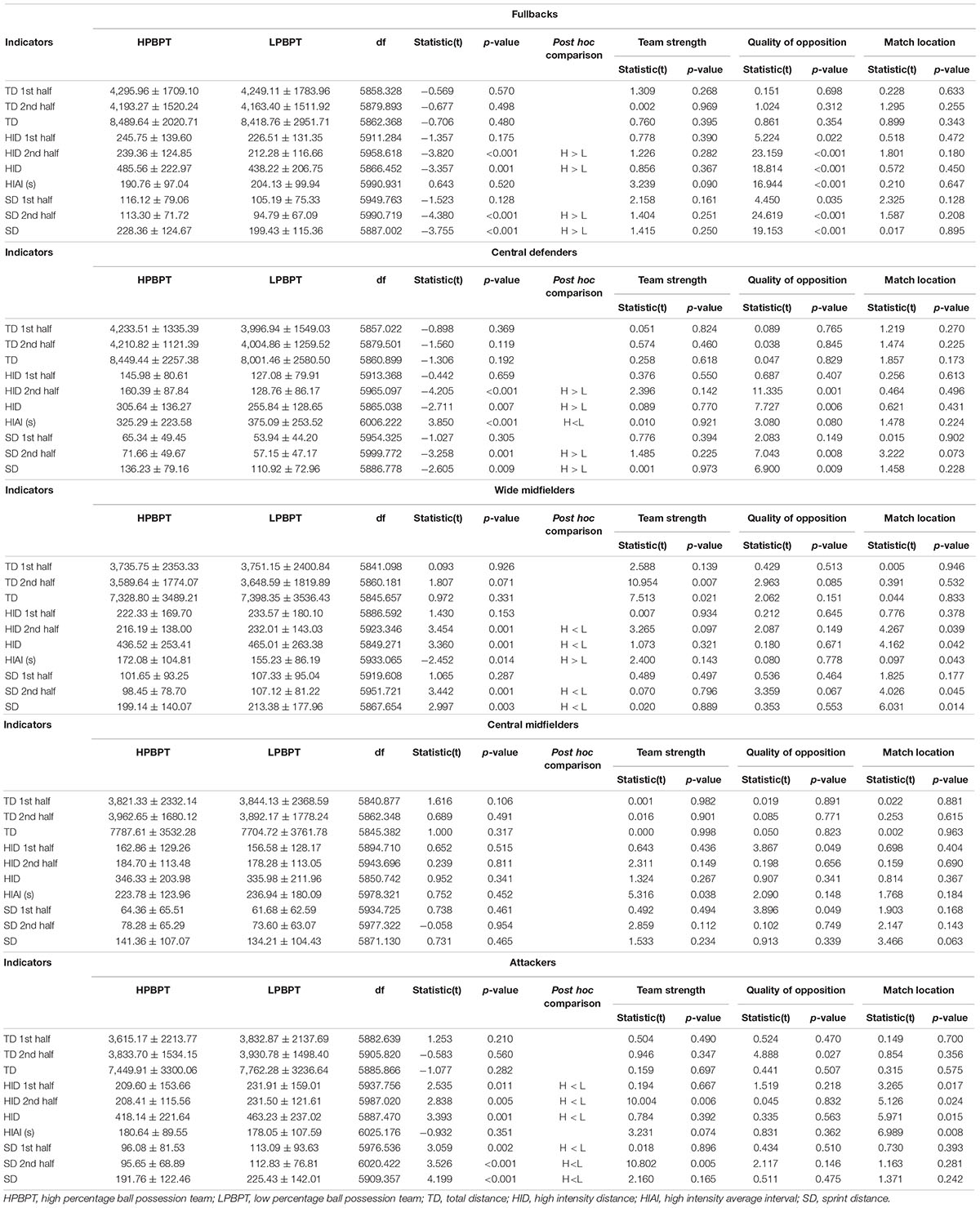

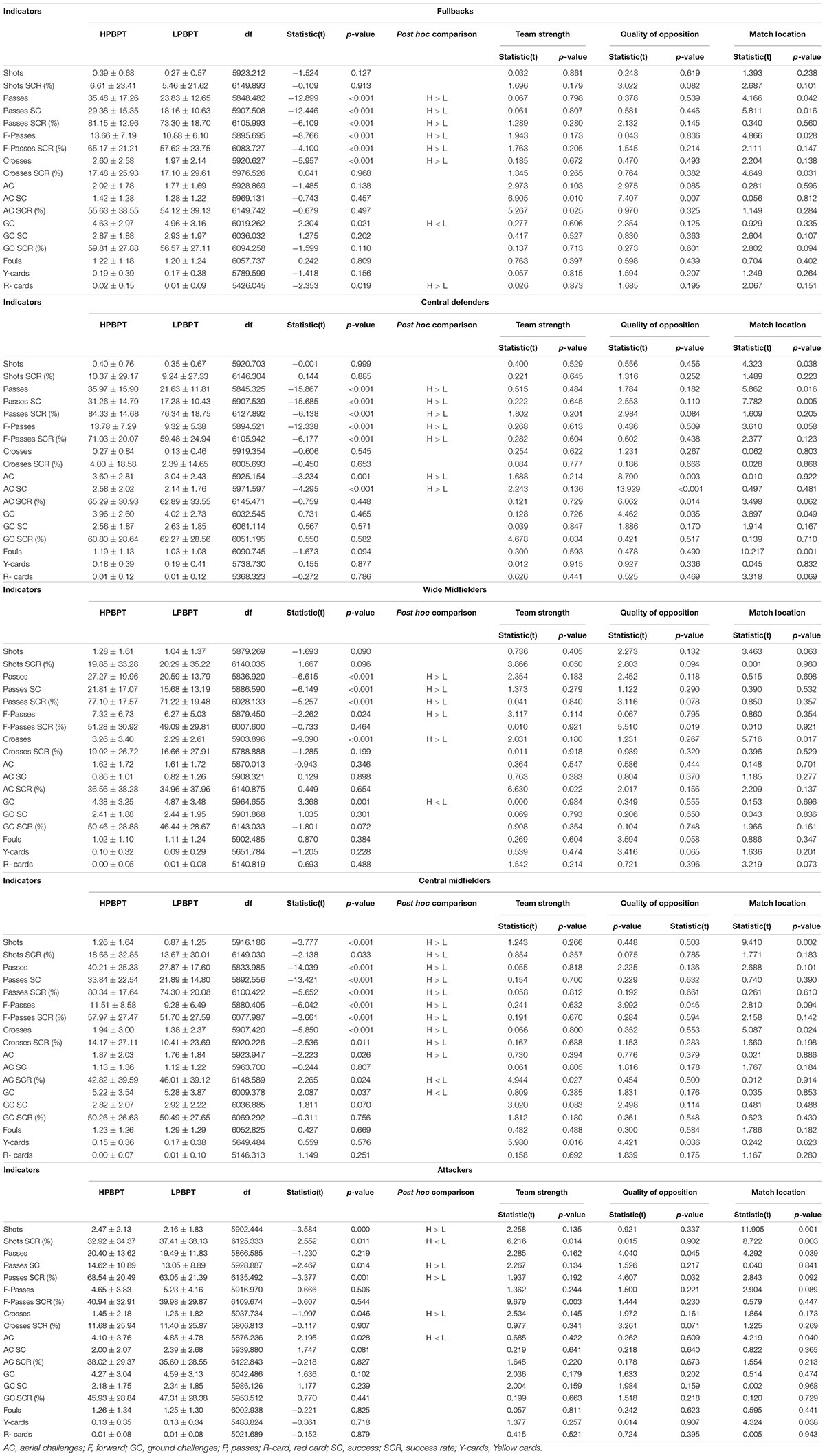

Table 4 shows the technical and tactical performance indicators for HPBPT and LPBPT. HPBPT performed better in their offensive indicators than LPBPT. These indicators included shots, total passes, successful passes, pass success rates, forward passes, success rates of forward passes, corners, crosses, possession in opponent’s half, opponent 35 m entry, opponent penalty area entry, and success rate of aerial challenges (p < 0.05). However, LPBPT played more ground challenges than HPBPT (p = 0.002). As covariates, TS, QO, and ML also had a certain impact on the teams’ technical performance.

The technical and tactical performance indicators across playing positions in HPBPT and LPBPT are illustrated in Table 5. Technical indicators such as total passes, successful passes, pass success rates, forward passes, success rates of forward passes, crosses and red cards were higher among fullbacks in HPBPT than in LPBPT (p < 0.05). LPBPT fullbacks carried out more ground challenges than their HPBPT counterparts (p < 0.05). HPBPT central defenders recorded more total passes, successful passes, pass success rates, forward passes, success rates of forward passes, aerial challenges and number of successful aerial challenges than their LPBPT counterparts (p < 0.05). HPBPT wide midfielders also recorded more total passes, successful passes, pass success rates, forward passes, and crosses than their LPBPT counterparts (p < 0.05). However, there were slightly more ground challenges for wide midfielders from LPBPT than those from HPBPT (p = 0.001). HPBPT central midfielders also recorded more shots, shot success rates, total passes, successful passes, pass success rates, forward passes, forward pass success rates, crosses, and cross success rates than players in the same position from LPBPT (p < 0.05). However, there were slightly higher success rates of aerial challenges and ground challenges for central midfielders from LPBPT than those from HPBPT (p < 0.05). Compared to LPBPT, attackers from HPBPT recorded more shots, successful passes, pass success rates and crosses (p < 0.05) but had poorer shots success rates (p = 0.011) and aerial challenges (p = 0.028). As covariates, TS mainly affected AC and the AC success rate in fullbacks; GC success rate in central backs; shots success rate and AC success rate in wide midfielders; AC success rate and yellow cards in central midfielders; and F-passes success rate and shots success rate in forward. QO had impacts on AC success rate in fullbacks; on AC, AC success and its rate in central defenders; on F-passes success rate in wide midfielders; on F-passes and yellow cards in central midfielders; and on pass success rate in forward. ML mostly impacted pass related variables in fullbacks; passes and their success rate, GC and fouls in central backs; crosses in wide midfielders; shots and crosses in central midfielders; and shots, shots success rate, passes, AC and yellow cards in forward.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze physical fitness and technical-tactical performance under high and low ball possession (BP) in different playing positions in the CSL, while contextual variables including team strength (TS), quality of opposition (QO), and match location (ML) were also considered as covariates. To our knowledge, this is the first study that analyses activities in terms of ball possession and playing positions in the CSL. The main findings were as follows: (1) high-intensity running with and without ball is the major difference between high possession and low possession teams; positionally, central defenders and fullbacks in high possession teams covered more high-intensity and sprint running distance, while wide midfielders and forward from low possession teams covered more high-intensity and sprint running distance. (2) Teams with high possession and low possession exhibited differences in attacking organization variables, including quantity and quality. Moreover, high possession teams may be made up of players with a higher technical and tactical performance.

Running performance is widely studied by researchers. Compared to total running distance, which alone is not a key indicator for achieving success (Hoppe et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2018), high-intensity running and sprinting are especially important (Mohr et al., 2003), since they are directly associated with match outcome (Stolen et al., 2005; Faude et al., 2012; Wu and Zhang, 2017) and team ranking at the end of the season (Di Salvo et al., 2009; Rampinini et al., 2009; Hoppe et al., 2015). Previous studies on the CSL also suggested that high-intensity running plays a more critical role than total running distance (Wu and Zhang, 2017), similar to the present study. Thus, our results for high-intensity running distance are similar to prior studies conducted on the CSL (Wu and Zhang, 2017; Yang et al., 2018). In our study, high possession teams and low possession teams did not show significant differences in total high-intensity running distance, but there were differences found when teams had or did not have ball possession. High possession teams recorded more high-intensity running when they were in possession of the ball, whereas low possession teams recorded more high-intensity running when they were not in possession. This finding is in line with Bradley et al.(2013b, p. 1266), who also found “more distance covered by players in high-intensity running with than without the ball in HPBPT compared to LPBPT” (Bradley et al., 2013b).

Given that high possession teams are strongly associated with success (Lago-Peñas and Dellal, 2010), in the FA Premier League, Di Salvo et al. (2009) found that the five best teams also covered more high-intensity distance when they were in possession while middle and bottom teams (15 teams) ran more intensively than the top 5 teams when they were not in possession. Similar results were also reported in the German Bundesliga by Hoppe et al. (2015), where high-intensity distance with ball possession predicted the majority (60%) of the final rankings. This can be explained by the theory that “it is not match running performance alone that is important for achieving success, but rather its relation to technical/tactical skills with regard to ball possession” (Hoppe et al., 2015, p. 565). Maintaining ball possession through a successful pass is critical, which is probably why high ball possession teams covered less high-intensity distance than low ball possession teams when they were in possession, by using perfect techniques/tactics and keeping the opposition running for ball recovery (da Mota et al., 2016). This is consistent with research findings in the English Premier League (Bradley et al., 2013a).

Despite the importance of running intensity, some studies have stated that technical indicators determine team success more accurately than physical indicators (Di Salvo et al., 2009; Carling, 2013). Indeed, current findings show that high ball possession teams have a higher technical and tactical performance than low possession teams. These findings are supported by previous research studies (Bradley et al., 2013b). Both the quantity and quality of shots and attack organization-related indicators (e.g., forward pass success, pass success rate) are all positively related to high ball possession. High ball possession teams recorded more possession in the opponent’s half, final 1/3 entries, and penalty area entries, which were linked with high-intensity actions (Kai et al., 2018) and shooting opportunities (Lago, 2009; Tenga and Sigmundstad, 2011; Bradley et al., 2014). These important technical and tactical indicators are also key indicators of successful teams in the CSL (Yang et al., 2018) and can reveal the players’ good skills in high ball possession teams.

Using a wide range of CSL player samples, the current results showed that the players’ running performances were different in different playing positions. Physically, fullbacks and center backs from high ball possession teams covered more high-intensity distance and had fewer high-intensity average intervals, while wide midfielders and attackers from low ball possession teams had certain higher high-intensity indicators than their high ball possession team counterparts. Center midfielders were similar in running performance in both high/low possession teams. These results are interesting because the running performance of fullbacks from high ball possession teams or successful teams is already greater than that of wide midfielders. Prior studies found strong correlations between playing position and player running performance, especially in high-intensity running (Bloomfield et al., 2007; Di Salvo et al., 2007, 2009; Bradley et al., 2009; Lago-Peñas et al., 2009; Mallo et al., 2015), where midfielders recorded more total distance and high-intensity running than any other position (Di Salvo et al., 2007, 2009; Bradley et al., 2009; Lago-Peñas et al., 2009; Rampinini et al., 2009).

These published data were reported approximately 10 years ago and during this decade world football has evolved rapidly. For example, studies on increased high-intensity running and sprinting distance (Barnes et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2020). Bradley et al. (2013b) found similar results, where fullbacks from high ball possession teams performed more high-intensity running and sprinting. Furthermore, there were some recent findings showing that fullbacks covered greater high-intensity and sprint distance than wide midfielders (Vardakis et al., 2019; Aquino et al., 2020). This might be due to playing formation (playing style culture), but it could be due to the football development trend, which is “total possession play.” Typical examples are Spain (2008–2012) and Germany (2014–2018); these players push forward (very hard) when attacking and start to press opponent players immediately after losing possession. Since this playing style became popular around the football world, strong teams tended to adopt this style first, and team formation became increasingly narrow and principally moved more as a whole than ever before. On the one hand, when attacking, three lines of players move together deep into the opponents’ half. In this case, center backs and fullbacks cover a greater distance than ever before, and fullbacks (side backs) play the role of early wide midfielders who are already positioned inside, leaving a passage at the wing to fullbacks. On the other hand, when defending, fullbacks and center backs must run intensively or even sprint to mark opponent players or chase the ball and opponent attackers until the ball is intercepted, resulting in a fast counterattack. This could explain why defenders cover more distance with a different kind of running because high ball possession teams are capable of gaining more entry into their opponents’ half, attacking 1/3 zones, and the penalty area, which are relatively far from their own goal. Consequently, side backs need to run more at high intensity and sprint. Meanwhile, low ball possession teams have to choose a counterattack strategy when facing quality opponents because low possession teams have fewer chances of achieving penetrative passes, so they have to exploit any weaknesses in their strong opponents’ defense and effectively take advantage of an imbalanced defense (Tenga et al., 2010b; Lago-Ballesteros et al., 2012). In this case, forward and side midfielders from low ball possession teams will perform many high-intensity and sprint runs. In addition, since many counterattacks are frequently taken through the side area, side midfielders from low ball possession teams need to both attack and defend (overlapping run) so they have fewer high-intensity average intervals.

Technically, players in different positions from high ball possession teams, especially defenders and midfielders, record a higher technical performance in most indicators in offense (organizing) and shots. These findings are consistent with previous studies regarding high and low possession (Bradley et al., 2013b; da Mota et al., 2016). Moreover, it could be suggested that teams with the skills to sustain possession (or long passing sequences) have a better chance of creating shooting opportunities and thus scoring goals (Hughes and Franks, 2005). That is probably the reason why high ball possession teams are usually strong teams. Strong teams have good players who are perfect at finishing techniques in spite of intense competition and small spaces, and good players are good physically (Mohr et al., 2003) so that they can maintain their playing level and playing style. Bradley et al. (2013b) pointed out that high-intensity running with ball possession and passing ability are very important for a high percentage ball possession strategy, which is line with the results of this study. Good ball passing and control skills are critical for every playing position, although demand varies for different positions. In modern football, defenders have begun to play partial roles as midfielders, midfielders have some overlap with forward, and forward tend to form the first line of starting defense. These changes require players not only to be able to play their own position but also other positions, all of which require good techniques. In this research study, fullbacks from high ball possession teams passed even more than wide midfielders from low ball possession teams. These findings are in line with the UEFA Champions league (Yi et al., 2018), where defenders have become launching points that are greatly involved in attacking (Bush et al., 2015a; Liu et al., 2016) because of the abovementioned “football trend” in recent decades, indicating that defenders today already play in a more important position than ever before.

In this study, TS, QO, and ML had a certain influence along with ball possession on the performance indicators, but did not interfere greatly with the possession effect. The high possession teams had their own advantages and this playing style represents a football trend which needs to be studied and understood. The limitation for this study was that we did not consider possession in the opponents’ half and attacking 1/3 zones as independent variables. Further research studies are warranted and should include these two factors, which could help us to more precisely understand the influence of possession because always passing in one’s own half has not been shown to risk opponent goals and win the match. Additionally, future studies should include more samples (other countries), categories (different competitive levels), genders (women), and ages (youth players).

Conclusion

Our main findings demonstrated that ball possession influenced team performance both physically and technically, primarily in high-intensity running, sprinting in possession, and high-intensity running out of possession, as well as attack-related indicators such as shots, passing, and entry into opposition areas. Defenders from high ball possession teams engaged in more high-intensity and sprint running, whereas wide midfielders and attackers from low ball possession teams engaged in more high-intensity running and sprinting. Meanwhile, players from high ball possession teams were strong in technical indicators, especially in attacking organization. These results may help coaches to understand current football development trends and develop suitable training plans and tests for elite football players. This study could also be a guide for the development of longitudinal youth football training plans.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

TL conceptualized the study and wrote the original draft preparation. TL and LY contributed to the methodology. LY and HC contributed to data collection and visualization. TL, LY, HC, and AG-d-A reviewed and edited the manuscript. AG-d-A helped to improve this work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Liang Zhang from BNU and Qiu Chen from BIT for helping us to improve this manuscript.

References

Aquino, R., Carling, C., Palucci Vieira, L. H., Martins, G., Jabor, G., Machado, J., et al. (2020). Influence of situational variables, team formation, and playing position on match running performance and social network analysis in brazilian professional soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 34, 808–817 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002725

Barnes, C., Archer, D. T., Hogg, B., Bush, M., and Bradley, P. S. (2014). The evolution of physical and technical performance parameters in the English Premier League. Int. J. Sports Med. 35, 1095–1100 doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1375695

Bate, R. (1988). “Football chance: tactics and strategy,” in Science and Football VIII: the Proceedings of the Eighth World Congress on Science and Football, eds T. Reilly, A. Lees, and K. Davids. Milton Park: Routledge

Bloomfield, J., Polman, R., and O’Donoghue, P. (2007). Physical demands of different positions in FA premier league soccer. J. Sports Sci. Med. 6, 63–70

Bloomfield, J., Polman, R., and O’donoghue, P. (2005). Effects of score-line on team strategies in FA premier league soccer. J. Sports Sci. 23, 192–193.

Bradley, P. S., Lago-Penas, C., Rey, E., and Gomez Diaz, A. (2013b). The effect of high and low percentage ball possession on physical and technical profiles in English FA Premier League soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 31, 1261–1270. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.786185

Bradley, P. S., Carling, C., Gomez Diaz, A., Hood, P., Barnes, C., Ade, J., et al. (2013a). Match performance and physical capacity of players in the top three competitive standards of English professional soccer. Hum. Mov. Sci. 32, 808–821. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2013.06.002

Bradley, P. S., Lago-Penas, C., Rey, E., and Sampaio, J. (2014). The influence of situational variables on ball possession in the English Premier League. J. Sports Sci. 32, 1867–1873. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.887850

Bradley, P. S., Sheldon, W., Wooster, B., Olsen, P., Boanas, P., and Krustrup, P. (2009). High-intensity running in English FA Premier League soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 27, 159–168. doi: 10.1080/02640410802512775

Bush, M., Archer, D. T., Hogg, R., and Bradley, P. S. (2015a). Factors influencing physical and technical variability in the English Premier League. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 10, 865–872. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0484

Bush, M., Barnes, C., Archer, D. T., Hogg, B., and Bradley, P. S. (2015b). Evolution of match performance parameters for various playing positions in the English Premier League. Hum. Mov. Sci. 39, 1–11 doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2014.10.003

Carling, C. (2013). Interpreting physical performance in professional soccer match-play: should we be more pragmatic in our approach? Sports Med. 43, 655–663 doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0055-8

Carling, C., Williams, A. M., and Reilly, T. (2005). Handbook of Soccer Match Analysis : a Systematic Approach to Improving Performance. Milton Park: Routledge.

Castellano, J., Alvarez-Pastor, D., and Bradley, P. S. (2014). Evaluation of research using computerised tracking systems (Amisco and Prozone) to analyse physical performance in elite soccer: a systematic review. Sports Med. 44, 701–712 doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0144-3

da Mota, G. R., Thiengo, C. R., Gimenes, S. V., and Bradley, P. S. (2016). The effects of ball possession status on physical and technical indicators during the 2014 FIFA World Cup Finals. J. Sports Sci. 34, 493–500 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1114660

Dellal, A., Chamari, K., Wong, D. P., Ahmaidi, S., Keller, D., Barros, R., et al. (2011). Comparison of physical and technical performance in European soccer match-play: FA Premier League and La Liga. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 11, 51–59. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2010.481334

Di Salvo, V., Baron, R., Tschan, H., Calderon Montero, F. J., Bachl, N., and Pigozzi, F. (2007). Performance characteristics according to playing position in elite soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 28, 222–227 doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924294

Di Salvo, V., Gregson, W., Atkinson, G., Tordoff, P., and Drust, B. (2009). Analysis of high intensity activity in Premier League soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 30, 205–212 doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1105950

Faude, O., Koch, T., and Meyer, T. (2012). Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football. J. Sports Sci. 30, 625–631

Fernandez-Navarro, J., Fradua, L., Zubillaga, A., and McRobert, A. P. (2018). Influence of contextual variables on styles of play in soccer. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 18, 423–436 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1479925

Fernandez-Navarro, J., Fradua, L., Zubillaga, A., Ford, P. R., and McRobert, A. P. (2016). Attacking and defensive styles of play in soccer: analysis of Spanish and English elite teams. J. Sports Sci. 34, 2195–2204 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1169309

Gai, Y., Leicht, A. S., Lago, C., and Gómez, M. -Á. (2018). Physical and technical differences between domestic and foreign soccer players according to playing positions in the China Super League. Res. Sports Med. 27, 314–325 doi: 10.1080/15438627.2018.1540005

Gong, B., Cui, Y., Zhang, S., Zhou, C., Yi, Q., and Gómez-Ruano, M. -Á. (2021). Impact of technical and physical key performance indicators on ball possession in the Chinese super league. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 21, 1–13 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2021.1957296

Hewitt, A., Greenham, G., and Norton, K. (2016). Game style in soccer: what is it and can we quantify it? Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 16, 355–372 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2016.11868892

Hoppe, M. W., Slomka, M., Baumgart, C., Weber, H., and Freiwald, J. (2015). Match running performance and success across a season in german bundesliga soccer teams. Int. J. Sports Med. 36, 563–566 doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398578

Hughes, M., and Franks, I. (2005). Analysis of passing sequences, shots and goals in soccer. J. Sports Sci. 23, 509–514 doi: 10.1080/02640410410001716779

Jiang, Z., Huang, Z. -H., and Wu, F. (2018). Analysis on determinant running performance indicator under different match situation in chinese football association super league. China Sport Sci. Technol. 54, 64–70.

Jones, P. D., James, N., and Mellalieu, S. D. (2004). Possession as a performance indicator in soccer. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 4, 98–102. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2004.11868295

Kai, T., Horio, K., Aoki, T., and Takai, Y. (2018). High-intensity running is one of the determinats for achieving score-box possession during soccer matches. Football Sci. 15, 61–69.

Kempe, M., Vogelbein, M., Memmert, D., and Nopp, S. (2014). Possession vs. direct play: evaluating tactical behavior in elite soccer. Int. J. Sports Sci. 4, 35–41

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., and Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 1–26, 82. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13

Lago, C. (2009). The influence of match location, quality of opposition, and match status on possession strategies in professional association football. J. Sports Sci. 27, 1463–1469 doi: 10.1080/02640410903131681

Lago-Ballesteros, J., Lago-Penas, C., and Rey, E. (2012). The effect of playing tactics and situational variables on achieving score-box possessions in a professional soccer team. J. Sports Sci. 30, 1455–1461 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.712715

Lago-Peñas, C., and Dellal, A. (2010). Ball possession strategies in elite soccer according to the evolution of the match-score: the influence of situational variables. J. Hum. Kinet. 25, 93–100. doi: 10.2478/v10078-010-0036-z

Lago-Peñas, C., Lago-Ballesteros, J., Dellal, A., and Gómez, M. (2010). Game-related statistics that discriminated winning, drawing and losing teams from the Spanish soccer league. J. Sports Sci. Med. 9:288

Lago-Peñas, C., Rey, E., Lago-Ballesteros, J., Casais, L., and Domínguez, E. (2009). Analysis of work-rate in soccer according to playing positions. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 9, 218–227 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2009.11868478

Liu, H., Gomez, M. A., Goncalves, B., and Sampaio, J. (2016). Technical performance and match-to-match variation in elite football teams. J. Sports Sci. 34, 509–518. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1117121

Liu, T., Garcia-de-Alcaraz, A., Wang, H., Hu, P., and Chen, Q. (2021). Impact of scoring first on match outcome in the chinese football super league. Front. Psychol. 12:662708 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662708

Liu, T., García-De-Alcaraz, A., Zhang, L., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Exploring home advantage and quality of opposition interactions in the Chinese Football Super League. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 19, 289–301 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2019.1600907

Mallo, J., Mena, E., Nevado, F., and Paredes, V. (2015). Physical demands of top-class soccer friendly matches in relation to a playing position using global positioning system technology. J. Hum. Kinet. 47, 179–188 doi: 10.1515/hukin-2015-0073

Mohr, M., Krustrup, P., and Bangsbo, J. (2003). Match performance of high-standard soccer players with special reference to development of fatigue. J. Sports Sci. 21, 519–528 doi: 10.1080/0264041031000071182

Pollard, R., and Reep, C. (1997). Measuring the effectiveness of playing strategies at soccer. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D 46, 541–550. doi: 10.1111/1467-9884.00108

R Core Team (2021). R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing

Rampinini, E., Impellizzeri, F. M., Castagna, C., Coutts, A. J., and Wisloff, U. (2009). Technical performance during soccer matches of the Italian Serie a league: effect of fatigue and competitive level. J. Sci. Med. Sport 12, 227–233 doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.10.002

Redwood-Brown, A., Bussell, C., and Bharaj, H. S. (2012). The impact of different standards of opponents on observed player performance in the English Premier League. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 7, 341–355 doi: 10.4100/jhse.2012.72.01

Russell, L. (2021). Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R Package Version 1.6.2-1

Sarmento, H., Pereira, A., Matos, N., Campaniço, J., Anguera, T. M., and Leitão, J. (2013). English premier league, Spaińs La Liga and Italýs Seriés a – what’s different? Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 13, 773–789 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2013.11868688

Stolen, T., Chamari, K., Castagna, C., and Wisloff, U. (2005). Physiology of soccer: an update. Sports Med. 35, 501–536 doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535060-00004

Taylor, J. B., Mellalieu, S. D., and James, N. (2004). Behavioural comparisons of positional demands in professional soccer. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 4, 81–97. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2004.11868294

Tenga, A., and Sigmundstad, E. (2011). Characteristics of goal-scoring possessions in open play: Comparing the top, in-between and bottom teams from professional soccer league. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 11, 545–552 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2011.11868572

Tenga, A., Holme, I., Ronglan, L. T., and Bahr, R. (2010a). Effect of playing tactics on achieving score-box possessions in a random series of team possessions from Norwegian professional soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 28, 245–255 doi: 10.1080/02640410903502766

Tenga, A., Holme, I., Ronglan, L. T., and Bahr, R. (2010b). Effect of playing tactics on goal scoring in Norwegian professional soccer. J. Sports Sci. 28, 237–244 doi: 10.1080/02640410903502774

Valter, D. S., Adam, C., Barry, M., and Marco, C. (2017). Validation of Prozone ® : a new video-based performance analysis system. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 6, 108–119 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2006.11868359

Vardakis, L., Michailidis, Y., Mandroukas, A., Mavrommatis, G., Christoulas, K., and Metaxas, T. (2019). Analysis of the running performance of elite soccer players depending on position in the 1-4-3-3 formation. German J. Exerc. Sport Res. 50, 241–250 doi: 10.1007/s12662-019-00639-5

World Medical Association (2013). World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191–2194 doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Wu, F., and Zhang, T. -A. (2017). Impacts of running performance on match results in chinese football association super league. China Sport Sci. Technol. 53, 78–84.

Yang, G., Leicht, A. S., Lago, C., and Gomez, M. A. (2018). Key team physical and technical performance indicators indicative of team quality in the soccer Chinese super league. Res. Sports Med. 26, 158–167 doi: 10.1080/15438627.2018.1431539

Yi, Q., Gomez, M. A., Wang, L., Huang, G., Zhang, H., and Liu, H. (2019). Technical and physical match performance of teams in the 2018 FIFA World Cup: effects of two different playing styles. J. Sports Sci. 37, 2569–2577 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2019.1648120

Yi, Q., Jia, H., Liu, H., and Gómez, M. Á. (2018). Technical demands of different playing positions in the UEFA Champions League. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 18, 926–937 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1528524

Zhou, C., Gómez, M. -Á., and Lorenzo, A. (2020). The evolution of physical and technical performance parameters in the Chinese Soccer Super League. Biol. Sport 37, 139–145 doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2020.93039

Zhou, C., Zhang, S., Lorenzo Calvo, A., and Cui, Y. (2018). Chinese soccer association super league, 2012–2017: key performance indicators in balance games. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 18, 645–656 doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1509254

Keywords: team sports, performance analysis, game demands, player role, physical performance, technical indicators

Citation: Liu T, Yang L, Chen H and García-de-Alcaraz A (2021) Impact of Possession and Player Position on Physical and Technical-Tactical Performance Indicators in the Chinese Football Super League. Front. Psychol. 12:722200. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722200

Received: 08 June 2021; Accepted: 31 August 2021;

Published: 29 September 2021.

Edited by:

Corrado Lupo, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Miguel-Angel Gomez-Ruano, Polytechnic University of Madrid, SpainAlexandru Nicolae Ungureanu, Università di Torino, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Liu, Yang, Chen and García-de-Alcaraz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tianbiao Liu, ltb@bnu.edu.cn; Antonio García-de-Alcaraz, antoniogadealse@gmail.com

Tianbiao Liu

Tianbiao Liu Lang Yang

Lang Yang Huimin Chen1

Huimin Chen1 Antonio García-de-Alcaraz

Antonio García-de-Alcaraz