- School of Management, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

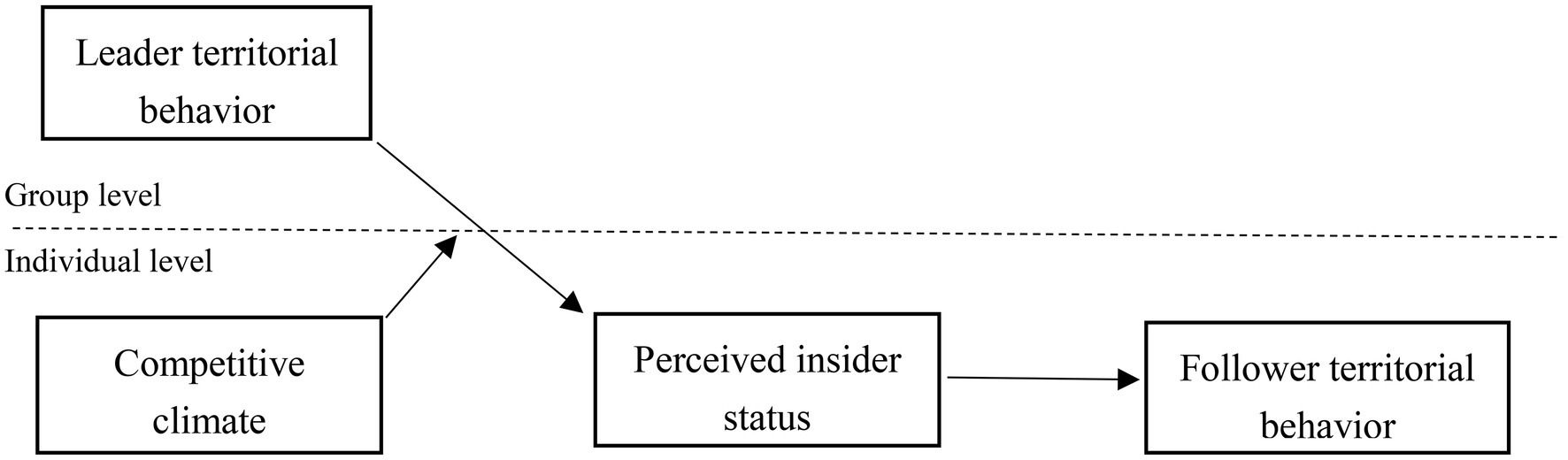

The present research seeks to explore how and when leader territorial behavior trickles down to the follower. Relying on social information processing theory, we hypothesize that territorial behavior has a trickle-down effect from leader to follower, and perceived insider status mediates the relationship between leader territorial behavior and follower territorial behavior. Competition climate is supposed to strengthen the effect of leader territorial behavior on perceived insider status. Two hundred and fifty-two dyads data of supervisor–subordinate in Chinese enterprises provided support for our hypotheses. The results suggest that leader territorial behavior is positively related to follower territorial behavior and that follower perceived insider status significantly mediates the relationship. Moreover, competition climate strengthens the negative relationship between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status as well as the indirect effect of leader territorial behavior on follower territorial behavior via perceived insider status. Theoretical and practical implications are further discussed.

Introduction

Territorial behavior has been widely discussed in the field of organization and management in recent years (Monaghan and Ayoko, 2019; Singh, 2019; Xu and Li, 2021). Territorial behavior refers to an individual’s behavioral expression of his or her feelings of ownership to a physical or social object (Brown et al., 2005). Historically, researchers focused on exploring the antecedents of territorial behavior such as individuals’ psychological ownership (Brown, 2009; Baer and Brown, 2012; Brown et al., 2014; Brown and Zhu, 2016; Wang et al., 2019), territorial infringement (Brown and Robinson, 2010), and organizational territorial climate (Li et al., 2020a), while surprisingly scarce researches have been done about leadership factors as antecedent (for exceptions, see Brown and Menkhoff, 2007; Brown and Zhu, 2016; Boekhorst et al., 2019). Besides, relatively few studies examined the leader territorial behavior (Gardner et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2021). Such an omission is surprising given that the supervisor serves as the agent representing the organization (Coyle-Shapiro and Shore, 2007) and supervisor territorial behavior may have great influence on the whole organization (Brown and Menkhoff, 2007). Following this logic, it is important to consider whether there will be a trickle-down effect of leader territorial behavior on follower territorial behavior.

Social information processing model indicates that individuals make decisions and exhibit subsequent behaviors according to the relevant information that they obtain from their surroundings (Salancik and Pfeffe, 1978). Supervisors, as significant clues of organizational environment, are critical to employee’s perception and behaviors (Bavik et al., 2018). Perceived insider status is indicative of a sense of belonging within the organization (Masterson and Stamper, 2003), describing the extent to which an employee perceived himself/herself as an insider in a particular organization (Stamper and Masterson, 2002). In fact, for employees, leaders are the main transmitters of information, and they are entitled to control employees’ resources, salary, and career development (Dépret and Fiske, 1993; Hu and Shi, 2015). Individuals thus form perceptions about their status as an organizational member by the information or clues from their leaders’ behaviors (Stamper and Masterson, 2002; Loi et al., 2012). Thus, we propose that supervisor’s territorial behaviors can reduce perceived insider status of employees and further increase their territorial behaviors.

The influence of supervisor’s territorial behavior on employees’ perceived insider status may not always exist and may be affected by organizational contextual factors. Therefore, we infer that there is a boundary condition on the relationship between leader’s territorial behavior and follower territorial behavior. We contend that a key aspect of the social work environment that reflects personal relationships with relevant others is the degree of competition in the environment. Competition has been considered as a situation where individuals vie for limited resources or rewards (Wang et al., 2018). Competition climate may increase pressure and reduce team cooperation (Connelly et al., 2017; David et al., 2021). Thus, we argue that competitive climate prompts employees to pay more attention to the relationship between the leader and the resources provided by the leader. Following this rationale, we posit that competitive climate may moderate the relationship between supervisor’s territorial behavior and perceived insider status. By examining the moderation effect of competitive climate and the mediation effect of perceived insider status, we can further clarify the conditions under which territorial behavior can trickle down from leaders to employees.

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we attempt to increase our understanding of territorial behavior literature by demonstrating the trickle-down effect of territorial behavior. Some studies have explored the territorial behavior and its impact at the individual level (Boekhorst et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2021). However, the effect of leader territorial behavior is still unexplored. We attempt to address this gap in the literature by examining the trickle-down effect of leader territorial behavior. Second, social information processing model is one of the main theories in the trickle-down model and has been widely used in trickle-down phenomena (Loi et al., 2012; Vlachos et al., 2014). This study attempts to explain the mediating role of perceived insider status, which will help to explain the mechanism by which supervisor’s territorial behavior affects employee’s territorial behavior, offering fresh insights into territorial behavior research. Our theoretical model is summarized in Figure 1.

Theories and Hypotheses

The Trick-Down Effect of Territorial Behavior

Territorial behavior refers to behaviors that individuals used to mark and defend the social resources who feel ownership, including tangible resources such as physical space and possessions, as well as intangible resources, such as information and relationships (Gardner et al., 2016). In organization, leaders generally have higher positions than employees have in the organizational hierarchy, possess more valued resources (e.g., spaces, roles, relationships, responsibilities, knowledge, experiences, even the employees) and control the resources allocation within the team (Brown et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2019). Therefore, leaders may engage in territorial behavior because of the social defined nature of territoriality. Examples of leader territorial behavior might include a nameplate on the door or the titles like ‘Manager’ and ‘Lead’ to express their identity and a proprietary space in a shared office or the efforts to stop employees from accessing to important information (Brown et al., 2005).

As Friedkin (2001) suggested, the norms formed through a process of interpersonal influence with leaders who have influential positions. This is because leaders can transmit the accepted norms and values to the team members through the way they behave (Thom-Santelli, 2009). Therefore, leader territorial behavior may lead to the formation of team territorial norms and further influence whether an individual will engage in territorial behavior and the degree involved (Brown and Zhu, 2016). In such territorial norms, team members may protect their territories, maintaining territorial boundaries and be reluctant to venture into certain areas, take on certain roles, or establish certain relationships out of respect for another’s ownership of those territories (Brown et al., 2005). Consequently, individuals isolate themselves from others, neglect their relationship to the organization, and focus on their territories. We then predict that territorial behavior could trickle down from leaders to followers.

H1: Leader territorial behavior is positively related to follower territorial behavior.

Leader Territorial Behavior and Perceived Insider Status

The perceived insider status describes the extent to which an employee perceived himself/herself as an insider in a particular organization (Stamper and Masterson, 2002), and it connotes an employees’ sense of having earned a personal space and acceptance as an organizational member (Masterson and Stamper, 2003). Social information processing theory suggests that social information people get from work environment can affect people’s perceptions, attitudes, and behavior (Zalesny and Ford, 1990). Employees tend to collect relevant information from what their leader do and say to shape their perceptions and behaviors (Hu and Shi, 2015). Therefore, as the representative of the organization, the leader usually provides employees with relevant social cues about their status as an organizational member (Stamper and Masterson, 2002; Loi et al., 2012). This reasoning is consistent with the relational model of authority proposed by Tyler and Lind (1992), who suggested that perceptions of one’s relation to an authority are essential indicators of one’s relation to the entire group, the employees’ feeling about how ‘included’ they are in the organization may, therefore, depend on how they are treated by the supervisor.

As a leader behavior, the leader’s behavioral expression of his or her territory is the important social cues that employees may use to interpret their organization membership. Territorial behavior may affect others’ perceptions of the individual who engage in territorial behavior. For example, territorial behavior may be viewed as an attempt to control resources (Brown and Zhu, 2016); individuals involved in territorial behavior may be considered as an uncooperative person. Therefore, leader territorial behavior may adversely, and perhaps unintentionally, send negative information to others by protecting valued resources and sharing less information, thereby employees may feel that they received less support and lower trust from the leader and organization. Given that the perceived organizational/leader support and trust are important factors influencing perceived insider status (Lapalme et al., 2009), leader territorial behavior may harm employees’ perceived insider status.

Moreover, as a social-behavioral construct, territoriality, in particular, affects the interactions between members in the organization (Webster et al., 2008). Hence, leader territorial behavior forms negative interaction between leaders and employees. Brown and Menkhoff (2007) have suggested that the result of leader territorial behavior makes employees increasingly frustrated with their treatment and lack of acknowledgment, further affecting the leader–follower relationship and organization–follower relationship and reducing employees’ sense of belonging and loyalty to the organization. Considering perceived insider status is a product of employees’ sense-making processes that derive from inputs such as high-quality work relationships. We therefore predicted:

H2: Leader territorial behavior is negatively related to follower perceived insider status.

Perceived Insider Status and Employee Territorial Behavior

As a reflection of the quality of employee–organization relations, employees’ perceived insider status is a dimension to measure employees’ sense of belonging (Masterson and Stamper, 2003), which refers to a type of personal perception of being a member of an organization. Employees who perceived themselves as insiders in the organization are more likely to form the cognition of citizens of the firm and accept the role, responsibilities, and requirements consistent with this identity (Hui et al., 2015). Therefore, as important members of an organization, employees will share their resources and invest more resources in defending the organization (Lapalme et al., 2009) and increase their participation and effort to help the organization (Han et al., 2010). In contrast, if the employees consider themselves as outsiders of the organization members, individuals will be more interested in preserving their own interests and less concerned about the welfare of others or the entire team (Brown et al., 2014). We thus propose:

H3: Perceived insider status is negatively related to follower territorial behavior.

The Mediation of Perceived Insider Status

The present research suggests that leader territorial behavior leads to follower territorial behavior because it reduces a sense of insider membership in the organization. According to the research of Lapalme et al. (2009), when the organization limits its investment in the employees, they may develop a perception that they are outsiders, these employees then limit their investment in the organization. Therefore, leader territorial behavior can reduce knowledge sharing and decrease resources allocation, which sends signals that indicate the individual does not matter to the company. Such a leader’s behavior reduces employee perceived insider status. Subsequently, the employees will seek less interaction with organization members, reinforce self-protection, and reduce resource sharing. We then predict:

H4: Perceived insider status mediates the relationship between leader territorial behavior and employee territorial behavior.

The Moderation of Competitive Climate

Competitive climate represents the extent to which employees perceive organization rewards to be contingent on comparisons of their performance against that of their peers (Brown et al., 1998). Like any environmental context, a competitive environment can have a significant influence on relationships between variables (Johns, 2006). This is because it is part of employees’ sense-making, helping them to both construct and interpret events that happen in that environment (Salancik and Pfeffe, 1978). Therefore, we argued that as a contextual factor in organizations, competition climate serves a critical role that moderates the impact of leader territorial behavior on employees perceived insider status by influencing how individuals understand their relationship with others.

First, by definition, competitive psychological climate consists of the following aspects: perceptions of differential reward distribution, the performance compared to other individuals, perceived competition with others, and frequent status comparisons (Fletcher et al., 2008). The comparisons with other employees cause further stress to the individual (Arnold et al., 2009), reduce collaboration with team members, and even lead to ostracizing (Ng, 2017). As a result, highly competitive climate destroys the trust foundation among team members, reduces their quality of the relationship, and makes employees pay more attention to the relationship with leaders. As a negative interpersonal interaction, leader territorial behavior will have a stronger impact on employees’ perception. In addition, perceptions of competitive climate reflect employees’ sense of the extent to which their job rewards, promotion, and retention depend on performance compared to others (Brown et al., 1998). Given that the important role of leaders in employee performance evaluation and career development, employees are sensitive to their leaders’ evaluation. More importantly, from the perspective of limited resources, the competitive climate describes a situation where individuals or organizations vie for limited resources or rewards (Wang et al., 2018). To access resources and achieve high performance, the employees focus on the leaders’ attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, when leaders engage in territorial behaviors, employees have a stronger reaction to leaders’ negative interpersonal treatment in a higher competitive climate. We then predict:

H5: Competitive climate moderates the negative relationship between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status, such that the negative relationship is stronger when competitive climate is higher.

Taken as a whole, the hypotheses presented above imply a moderated mediation model. Competitive climate may moderate the indirect effect of leader territorial behavior on employee territorial behavior through employee perceived insider status. Perceived insider status explains the relationships between leader territorial behavior and employee territorial behavior (H4), but because the relationship between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status is predicted to be stronger when the competitive climate is higher (H5), we predict that the mediated relationships captured by Hypothesis 4 are stronger when the competitive climate is higher. We then predict:

H6: Competitive climate moderates the indirect relationships between leader territorial behavior and employee territorial behavior such that the indirect effects are stronger when competitive climate is higher.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Procedure

We tested our hypotheses with data collected from three enterprises in Shanghai. To reduce common method variance and illusionary correlations, we collected data in two waves from May to June 2020. In the first stage, the leaders were asked to rate their territorial behavior and provided information in relation to their demographics, and the employees rated team competitive climate and provided information in relation to their demographic. Prior permission from HR departments in these enterprises was sought, and they also assisted us in survey distribution. To perform dyadic matching between employees and their corresponding leaders, all respondents were asked to indicate their leader or subordinates in the enterprises where they work. We explained the purpose of the research, emphasizing that the research is only for scientific study purposes, besides, the questionnaire number and personnel code were issued in a one-to-one correspondence way to ensure the authenticity, confidentiality, and accuracy of the questionnaire survey. One month later, the employees who responded in phase one were asked to rate their perceived insider status and territorial behavior online.

A total of 380 dyads questionnaires were distributed. After eliminating the obviously invalid questionnaires, the final sample of 252 employees with 65 managers was retained for a total response rate of 66.32%. Of those participants, the average income was 7.31 thousand yuan (SD=3.11); 64 percent were women (SD=0.48), and they averaged 24.47years of staying at the company (SD=22.28).

Measures

The instruments were administered in Chinese in our survey but were originally developed in English. To confirm the accuracy of the translation and correct any discrepancies, we employed back-translation procedures (Brislin, 1986). Unless otherwise indicated, we used a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Territorial Behavior

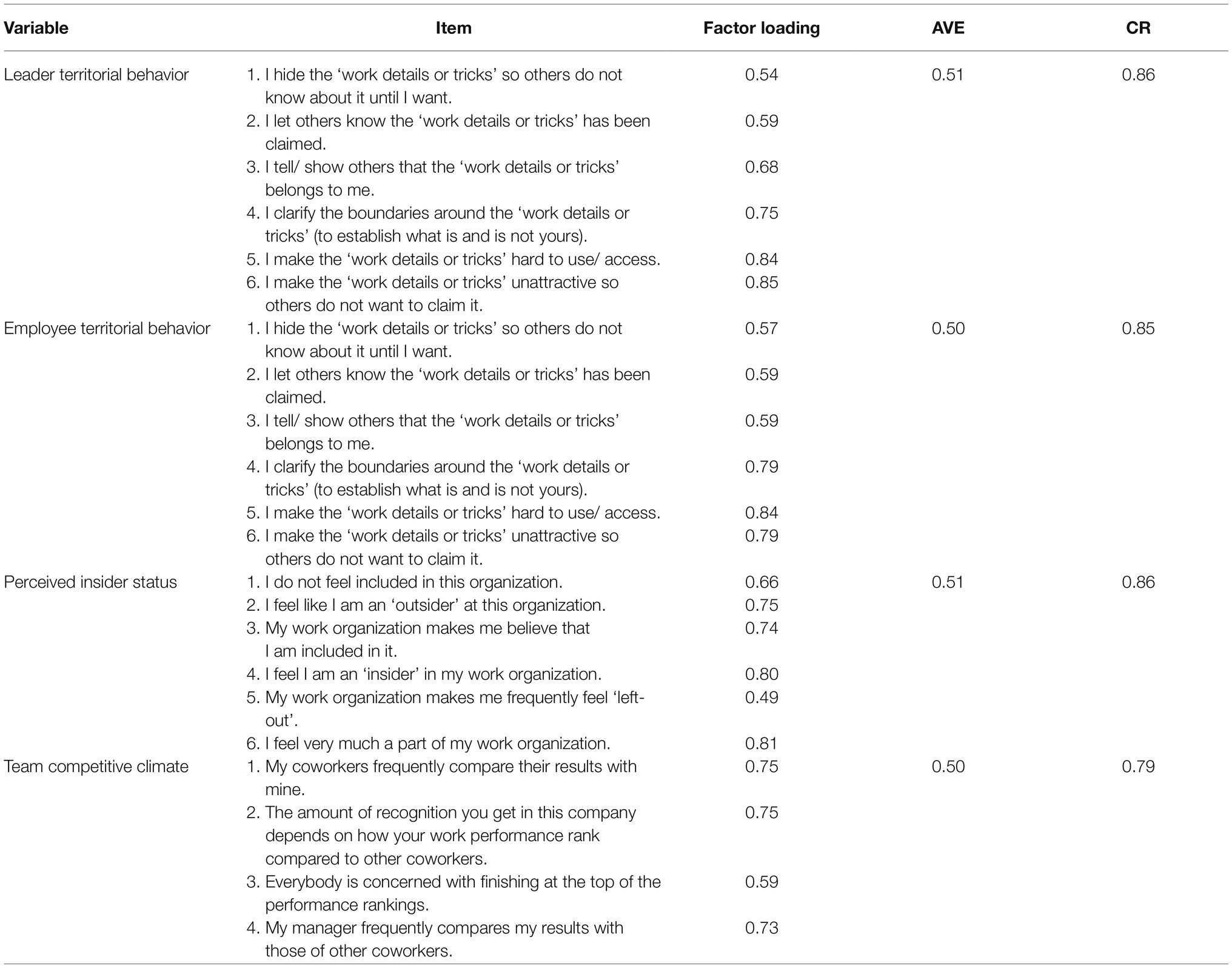

Territorial behavior (leader and follower) was measured using the six-item scale developed by Brown et al. (2014). A sample item is ‘I hide the ‘work details or tricks’ so others do not know about it until I want.’ Cronbach’s alpha of the leader scale was 0.85, and the employee scale was 0.82.

Perceived Insider Status

Perceived insider status was measured using the six-item scale developed by Stamper and Masterson (2002). A sample item is ‘My work organization makes me believe that I am included in it.’ Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.82.

Competitive Climate

For the measurement of competitive climate, we used the four-item scale of perceived team competitive climate by Brown et al. (1998). A sample item is ‘My coworkers frequently compare their results with mine.’ Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.71.

Control Variables

Previous studies have shown that certain socio-demographic variables like gender can affect territorial behavior (Mercer and Benjamin, 1980). Therefore, we controlled for the income and gender. We further controlled for the job tenure of subordinates because it takes some time to establish a supervisor–subordinate relationship.

Results

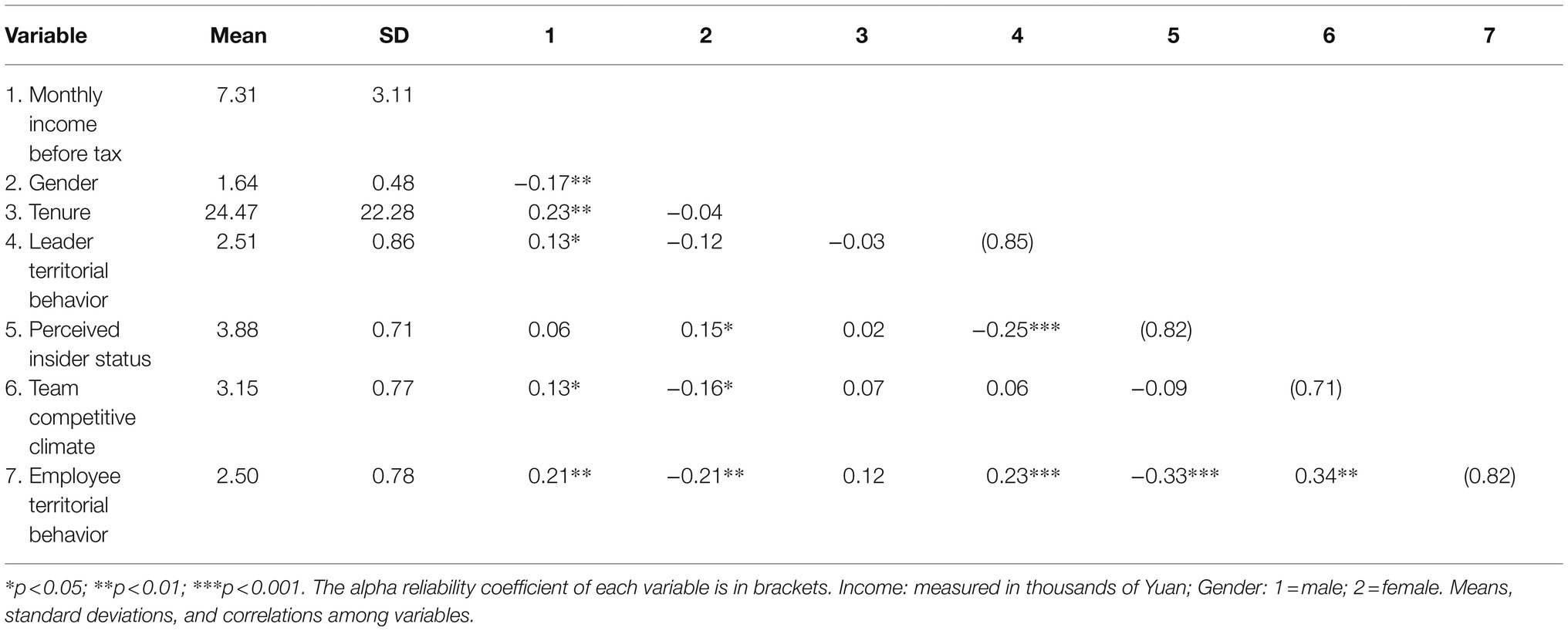

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables. The correlations are as expected. Leader territorial behavior was positively correlated with employee territorial behavior (γ=0.23, p<0.001). Leader territorial behavior was negatively correlated with perceived insider status (γ=−0.25, p<0.001). Perceived insider status was negatively correlated with employee territorial behavior (γ=−0.33, p<0.001).

Reliability and Validity

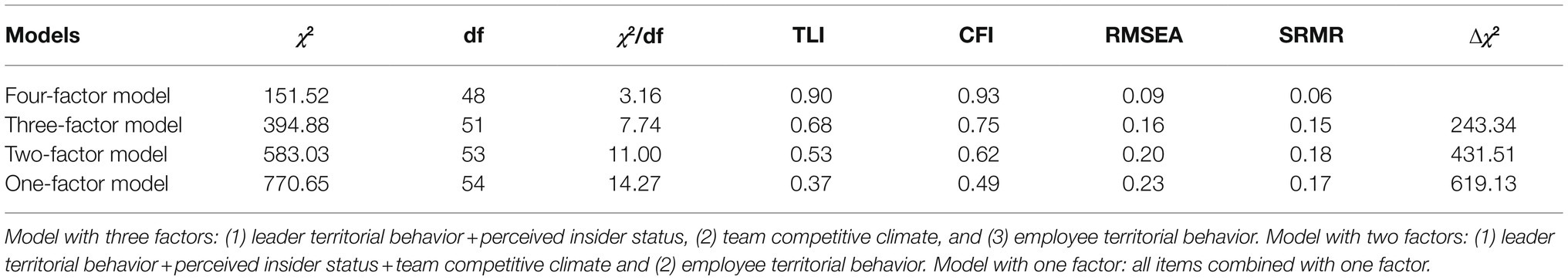

This study performed Harman’s one-factor test to verify the risk of common method effect (Podsakoff et al., 2003), which indicated that Harman’s single-factor test indicates the fixed single factor explains 25.28 percent of the covariance of the variables. The reliability of the multi-item scale for each dimension was assessed by using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The results in Table 2 showed that Cronbach’s alpha values of all of the constructs ranged from 0.71 to 0.85, exceeding the recommended minimum standard of 0.70 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Besides, the results in Table 3 showed that the composite reliability (CR) is higher than 0.7. Therefore, the reliability of the measurement in this study was acceptable.

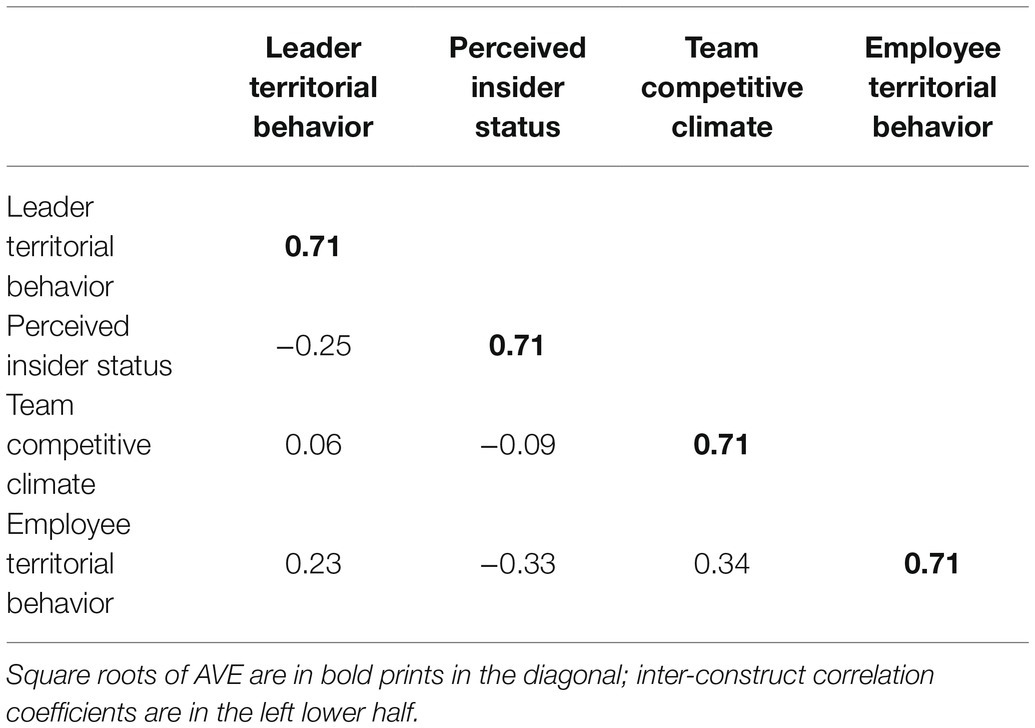

In addition, we computed the average variance extracted (AVE) for all variables. Discriminant validity was established by ensuring AVEs of any two variables which were higher than the square of their correlations (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Wang et al., 2021). In other word, the square root of AVEs of the variable is greater than the correlation coefficient between the variable and other variables, thus confirming the discriminant validity. The results in Table 4 showed that this rule was not violated as the inter-construct correlation coefficients ranged from 0.06 to 0.34, whereas the square root of the AVEs is 0.71, indicating acceptable discriminant validity.

The results in Table 3 showed that all the items loaded significantly onto their correspondent constructs with the factor loading range from 0.49 to 0.85, and average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than 0.5, indicating acceptable convergent validity. Although most items loaded nicely on their respective factors with standardized loadings coefficients being from 0.49 to 0.85, some items still loaded low (<0.708). We used full items in data analysis. This is because they are original measurement items for the internalization dimension of four scales, and the development of these items has undergone a rigorous psychometric process (Brown et al., 1998; Stamper and Masterson, 2002; Brown et al., 2014). Meanwhile, the reliability of the full item measure (>0.70) is adequate for research (cf. Nunnally, 1978; Hair et al., 2010) and consistent with those reported in other studies including that of Brown and Zhu themselves (2016; for others see Xiong Chen and Aryee, 2007; Chen et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019).

We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Mplus7.4 to compare possible measurement models. The results in Table 2 showed that the proposed four-factor model demonstrated a better fit (χ2=151.52, df=48, RMSEA=0.09, CFI=0.93, TLI=0.90, SRMR=0.06) to the data than other alternative models, indicating support for the distinctiveness of the constructs in the study. These results proved that the four-factor model was the most appropriate one that provided support for the convergent validity of our variables.

Null Model

We calculated the ICC(1) for employee territorial behavior to ascertain whether the use of multilevel modeling is necessary to analyze our data (Stawski, 2013). The ICC(1) was 0.12, meaning that 12% of the overall variance in employee territorial behavior was due to differences between groups, thus warranting a multilevel approach to data analysis.

Hypothesis Testing

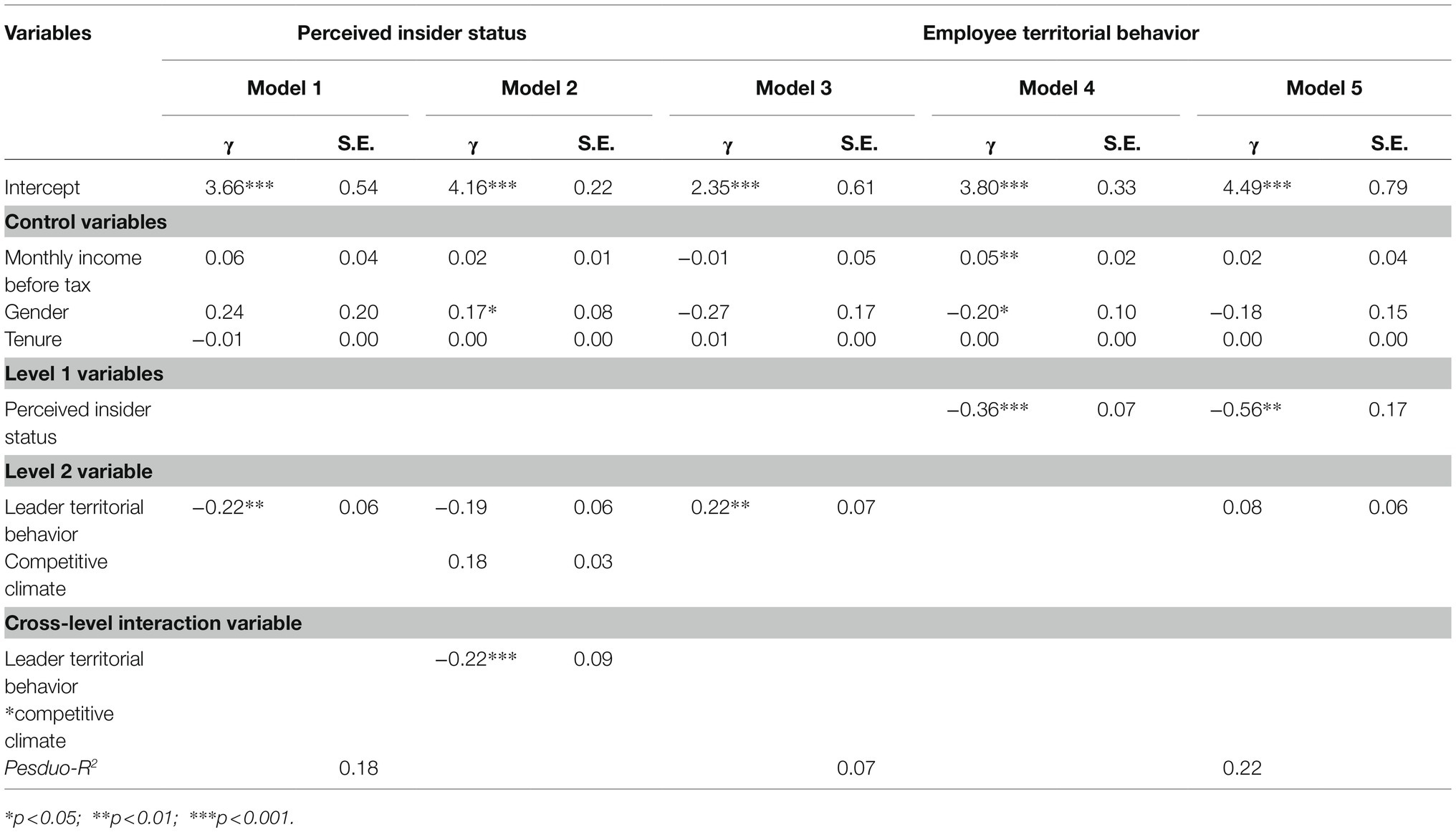

Hypothesis 1 predicted a positive relationship between leader territorial behavior and follower territorial behavior. In Model 3 of Table 5, the results suggested that leader territorial behavior was positively related to follower territorial behavior (γ=0.22, p<0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 posited that leader territorial behavior is negatively related to perceived insider status, and Hypothesis 3 proposed a negative relationship between perceived insider status and follower territorial behavior. As shown in Table 5, the results of Model 1 revealed that leader territorial behavior had a significant negative effect on perceived insider status (γ=−0.22, p<0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. The results of Model 4 revealed that perceived insider status had a significant negative effect on follower territorial behavior (γ=−0.36, p<0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Further, in Model 5, after entering perceived insider status, the positive relationship between leader territorial behavior and follower territorial behavior was not significant (γ=0.08, p>0.05). According to Baron and Kenny procedures (Baron and Kenny, 1986), we found support for the mediation of perceived insider status. In addition, we used the Monte Carlo simulation approach (Preacher and Selig, 2012) to assess the indirect effect. The results showed that the indirect effect was significant [95% CI=(0.01, 0.23), excluding 0]. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

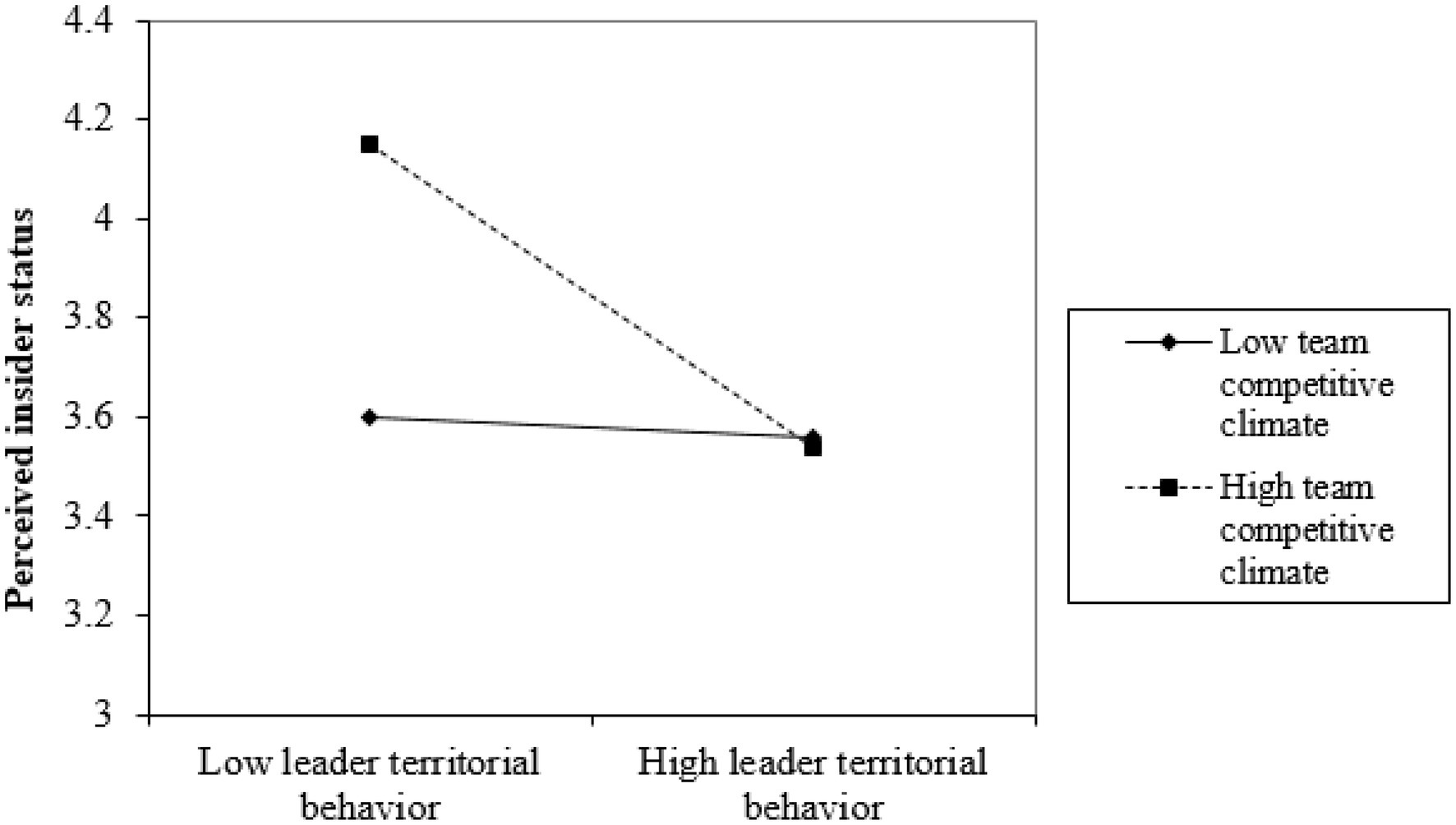

Hypothesis 5 predicted that competitive climate would moderate the relationship between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status. As shown in Model 2, the interactive effect was significant (γ=−0.22, p<0.001). Figure 2 further showed that this relationship was more negative when competitive climate was high (one SD above the mean) rather than low (one SD below the mean). Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Figure 2. Effect of the interaction between leader’s territorial behavior and team competitive climate on employee’s perceived insider status.

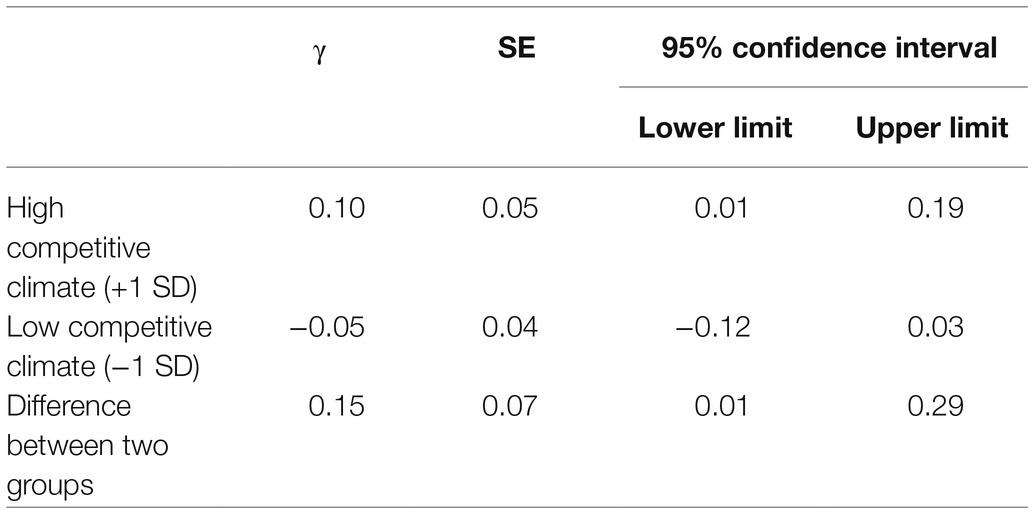

Hypothesis 6 predicted that competitive climate would moderate the indirect effect of leader territorial behavior on follower territorial behavior through perceived insider status. According to results presented in Table 6, competitive climate significantly moderated this indirect effect [difference=0.15, p<0.05, 95%CI=(0.01, 0.29), excluding 0]. Specifically, when competitive climate was high (one SD above the mean), moderated mediation effect was 0.10 [p<0.05, 95%CI=(0.01, 0.19), excluding 0]; when competitive climate was low (one SD below the mean), the moderated mediation effect was not significant. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

Discussion

The main objective of the present research is to explore how and when leader territorial behavior trickles down to followers. Relying on social information processing theory, we explored the mediating role of perceived insider status in linking leader territorial behavior with employee territorial behavior and the moderating role of competitive climate in influencing the relationship between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status. As hypothesized, we found that leader territorial behavior was positively related to employee territorial behavior and that perceived insider status mediated the relationship. Moreover, competitive climate strengthened the negative relationship between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status and the indirect effect of leader territorial behavior on employee territorial behavior via perceived insider status. We now discuss the theoretical and practical implications of the results.

Theoretical Implications

Our research provides empirical evidence for the trickle-down effect of a leader’s territorial behavior on an employee’s territorial behavior within the social information processing theory framework. Specifically, we are the first to theorize and propose a model in which leader’s territorial behavior trickles down to employee in the organization, which respond to Thom-Santelli’s (2009) call for exploring the predictors of territorial behavior from the perspective of leader. Our study’s results not only support the view that ‘Leaders are an important factor influencing follower behaviors and perceptions’ (Ambrose et al., 2013; Bavik et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019), they also supplement the literature on trickle-down effects of leader behaviors (e.g., Frazier and Tupper, 2016; Lu et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Byun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Previous studies primarily focused on the territorial behavior and its impact at the individual level (Boekhorst et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2021), while surprising few researches have been done about leader territorial behavior (for exceptions, see Gardner et al., 2016). There is territoriality at different levels of the organization (Brown et al., 2005). Given the territorial nature of human beings and the particular status of leaders in the organization, it is not surprising that leaders engage in territorial behavior. Gardner et al.’s (2016) study showed that managers engaged in territorial behaviors to maintain ownership claims over their employees. In addition, some studies suggested that leaders will protect the information and relationship, which affect the organization–employee relationship (Brown and Menkhoff, 2007). Therefore, this research contributes to the understanding of the leader territorial behavior and its consequences by describing how leader territorial behavior promotes employee territorial behavior on the organization.

Another contribution is our exploration of the trickle-down effect mechanism through which the effects of leader territorial behavior trickle down to employee territorial behavior. In doing so, we respond to scholars’ calls for more investigations to open the black box of the influences of leader territorial behavior (Gardner et al., 2016) by providing empirical evidence of employee perceived insider status as a mediator. Moreover, we provide a new perspective for the study of territorial behavior–social information processing theory. Specifically, our research differs from existing territorial behavior literature, which is largely based on the extended self-theory (Wang et al., 2019) and social exchange theory (Huo et al., 2017; Singh, 2019; Li et al., 2020b). In doing so, we extend the application of social information processing theory in the territorial behavior literature.

Practical Implications

Our findings have several important practical implications. First, the present study found that leader territorial behavior has trickled down effects on followers. Thus, organizations should take measures to reduce leader territorial behavior in the workplace. For example, the organization can effectively inhibit the leader territorial behavior by building an open office environment, encouraging leadership delegation, and holding experience sharing sessions. Second, the findings showed that perceived insider status mediates the trickle-down process. Thus, organizations can reduce employee territorial behavior by taking measures to increase employee perceived insider status. In the business management practice, organizations should offer resources support to their employees, who need to feel that they are part of group members or have special status. Moreover, organizations could also enhance employees’ perceived insider status through other ways such as delegation or organizational inducements (Hui et al., 2015). Third, the present study found that competitive climate strengthens the link between leader territorial behavior and perceived insider status. Thus, organizations should create a healthy competition atmosphere and avoid excessive competition to weaken the negative effect of leader territorial behavior on employee territorial behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

Our research has some limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, our method is restricted in some respects. Our data fitting results are acceptable, but still not good enough, such as RMSEA=0.09 and AVE=0.50 are slightly higher than the acceptable range when other indicators are acceptable. We think there may be two reasons. On the one hand, according to Bandalos’s recommendation (Bandalos, 2002), the parameter-to-item ratio should be above almost a certain proportion (10:1), our sample size is slightly higher than the acceptable standard, the direct use of the original title may lead to some estimation bias, and on the other hand, the reason why the Cronbach’s alpha of the competitive climate scale is 0.71 is that the participants may not be willing to truly evaluate the competitive atmosphere. Although this reliability is acceptable, it may still affect the fit of the whole model. Therefore, future research should use a more perfect questionnaire process to ensure that the participants can be express their real ideas and verify the conclusion with a larger sample. Besides, our three-waved time-lagged data still cannot verify causality certainly for all variables in our model. Future research should consequently replicate our conclusions with a more rigorous longitudinal research method or experimental method.

Second, samples from Chinese enterprises limit the generalizability of the findings to different contexts. Cultural values can influence how individuals perceive and react to leader behavior (Peng and Kim, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, further research could examine the relationship between leader territorial behavior and follower territorial behavior in other cultural contexts.

Third, we explored only one boundary condition—competitive climate moderates the relationship between leader territorial behavior and employee territorial behavior. There may be other moderator variables to mitigate the negative impact of leader territorial behavior, and future research can explore other organizational factors to reduce the negative impact of leader territorial behavior.

Conclusion

From the perspective of social information processing, this paper expounds in detail that territorial behavior has a trickle-down effect from leader to follower and perceived insider status mediates the relationship between leader territorial behavior and follower territorial behavior. Our findings expand the perspective of territorial behavior research and hope to spark further research on territorial behavior.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.721806/full#supplementary-material

References

Ambrose, M. L., Schminke, M., and Mayer, D. M. (2013). Trickle-down effects of supervisor perceptions of interactional justice: a moderated mediation approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 98, 678–689. doi: 10.1037/a0032080

Arnold, T., Flaherty, K. E., Voss, K. E., and Mowen, J. C. (2009). Role stressors and retail performance: The role of perceived competitive climate. J. Retail. 85, 194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2009.02.002

Baer, M., and Brown, G. (2012). Blind in one eye: how psychological ownership of ideas affects the types of suggestions people adopt. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 118, 60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.01.003

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 78–102. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_5

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bavik, Y. L., Tang, P. M., Shao, R., and Lam, L. W. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: exploring dual-mediation paths. Leadersh. Q. 29, 322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.05.006

Boekhorst, J., Halinski, M., and Good, J. (2019). Does having fun “come with the territory”? The role of fun activities on territorial behaviors. Acad. Manage. Proc. 2019:16030. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2019.16030abstract

Brislin, R. W. (1986). A culture general assimilator: preparation for various types of sojourns. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 10, 215–234.

Brown, G. (2009). Claiming a corner at work: measuring employee territoriality in their workspaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 29, 44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.05.004

Brown, S. P., Cron, W. L., and Slocum, J. W. Jr. (1998). Effects of trait competitiveness and perceived intraorganizational competition on salesperson goal setting and performance. J. Mark. 62, 88–98. doi: 10.1177/002224299806200407

Brown, G., Crossley, C., and Robinson, S. L. (2014). Psychological ownership, territorial behavior, and being perceived as a team contributor: The critical role of trust in the work environment. Pers. Psychol. 67, 463–485. doi: 10.1111/peps.12048

Brown, G., Lawrence, T. B., and Robinson, S. L. (2005). Territoriality in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 30, 577–594. doi: 10.5465/amr.2005.17293710

Brown, G., and Menkhoff, T. (2007). Territoriality over knowledge: Towards a cross-cultural perspective. J. Asian Business. 22, 103–112.

Brown, G., and Robinson, S. L. (2010). “Hey, that’s mine! The nature of territorial behavior in organizations.” in Paper presented at the ASAC 2005 Toronto, Ontario.

Brown, G., and Zhu, H. (2016). ‘My workspace, not yours’: The impact of psychological ownership and territoriality in organizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 48, 54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.08.001

Byun, G., Lee, S., Karau, S. J., and Dai, Y. (2020). The trickle-down effect of empowering leadership: a boundary condition of performance pressure. Leadership Organ. Dev. J. 41, 399–414. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-06-2019-0246

Chen, Y., Wang, L., Liu, X., Chen, H., Hu, Y., and Yang, H. (2019). The trickle-down effect of leaders’ pro-social rule breaking: joint moderating role of empowering leadership and courage. Front. Psychol. 9:2647. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02647

Chen, Z., Zhu, J., and Zhou, M. (2015). How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 511–521. doi: 10.1037/a0038036

Connelly, C. E., Ford, D. P., Turel, O., Gallupe, B., and Zweig, D. (2017). ‘I’m busy (and competitive)!’ Antecedents of knowledge sharing under pressure. Knowl. Manage. Res. Pract. 12, 74–85. doi: 10.1057/kmrp.2012.61

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., and Shore, L. M. (2007). The employee–organization relationship: where do we go from here? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 17, 166–179. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.03.008

David, E. M., Kim, T. Y., Rodgers, M., and Chen, T. (2021). Helping while competing? The complex effects of competitive climates on the prosocial identity and performance relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 58, 1507–1531. doi: 10.1111/joms.12675

Dépret, E. F., and Fiske, S. T. (1993). Social Cognition and Power: Some Cognitive Consequences of Social Structure as a Sources of Control Deprivation. Springer, New York, NY.

Fletcher, T. D., Major, D. A., and Davis, D. D. (2008). The interactive relationship of competitive climate and trait competitiveness with workplace attitudes, stress, and performance. J. Organ. Behav. 29, 899–922. doi: 10.1002/job.503

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Frazier, M. L., and Tupper, C. (2016). Supervisor prosocial motivation, employee thriving, and helping behavior: A trickle-down model of psychological safety. Group Org. Manag. 43, 561–593. doi: 10.1177/1059601116653911

Friedkin, N. E. (2001). Norm formation in social influence networks. Soc. Networks 23, 167–189. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(01)00036-3

Gardner, T. M., Munyon, T. P., Hom, P. W., and Griffeth, R. W. (2016). When territoriality meets agency: An examination of employee guarding as a territorial strategy. J. Manag. 44, 2580–2610. doi: 10.1177/0149206316642272

Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Han, T.-S., Chiang, H.-H., and Chang, A. (2010). Employee participation in decision making, psychological ownership and knowledge sharing: mediating role of organizational commitment in Taiwanese high-tech organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 21, 2218–2233. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2010.509625

Hu, X., and Shi, J. (2015). Employees' surface acting in interactions with leaders and peers. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 1132–1152. doi: 10.1002/job.2015

Hui, C., Lee, C., and Wang, H. (2015). Organizational inducements and employee citizenship behavior: The mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of collectivism. Hum. Resour. Manag. 54, 439–456. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21620

Huo, W. W., Yi, H., Men, C., Luo, J., Li, X., and Tam, K. L. (2017). Territoriality, motivational climate, and idea implementation: we reap what we sow. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 45, 1919–1932. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6849

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 31, 386–408. doi: 10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

Lapalme, M.-È., Stamper, C. L., Simard, G., and Tremblay, M. (2009). Bringing the outside in: can “external” workers experience insider status? J. Organ. Behav. 30, 919–940. doi: 10.1002/job.597

Li, X., Wei, W. X., Huo, W., Huang, Y., Zheng, M., and Yan, J. (2020a). You reap what you sow: knowledge hiding, territorial and idea implementation. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 16, 1583–1603. doi: 10.1108/IJOEM-05-2019-0339

Li, X., Xu, Z., and Men, C. (2020b). The transmission mechanism of idea generation on idea implementation: team knowledge territoriality perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 25, 1508–1525. doi: 10.1108/JKM-02-2020-0140

Loi, R., Lai, J. Y. M., and Lam, L. W. (2012). Working under a committed boss: A test of the relationship between supervisors' and subordinates' affective commitment. Leadersh. Q. 23, 466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.12.001

Lu, X., Xie, B., and Guo, Y. (2018). The trickle-down of work engagement from leader to follower: The roles of optimism and self-efficacy. J. Bus. Res. 84, 186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.014

Masterson, S. S., and Stamper, C. L. (2003). Perceived organizational membership: an aggregate framework representing the employee–organization relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 24, 473–490. doi: 10.1002/job.203

Mercer, G. W., and Benjamin, M. L. (1980). Spatial behavior of university undergraduates in double-occupany residence rooms: An inventory of effects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 10, 32–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1980.tb00691.x

Monaghan, N., and Ayoko, O. B. (2019). Open-plan office, employees’ enactment, interpretations and reactions to territoriality. Int. J. Manpow. 40, 228–245. doi: 10.1108/IJM-10-2017-0270

Ng, T. W. H. (2017). Can idiosyncratic deals promote perceptions of competitive climate, felt ostracism, and turnover? J. Vocat. Behav. 99, 118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.01.004

Peng, A. C., and Kim, D. (2020). A meta-analytic test of the differential pathways linking ethical leadership to normative conduct. J. Organ. Behav. 41, 348–368. doi: 10.1002/job.2427

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Preacher, K. J., and Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Commun. Methods Meas. 6, 77–98. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2012.679848

Salancik, G. R., and Pfeffe, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 23, 224–253. doi: 10.2307/2392563

Singh, S. K. (2019). Territoriality, task performance, and workplace deviance: empirical evidence on role of knowledge hiding. J. Bus. Res. 97, 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.034

Stamper, C. L., and Masterson, S. S. (2002). Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 875–894. doi: 10.1002/job.175

Stawski, R. S. (2013). Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 20, 541–550. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2013.797841

Thom-Santelli, J. (2009). “Expressing territoriality in collaborative activity,” in Paper Presented at the GROUP '09 Proceedings of the ACM 2009 International Conference on Supporting Group Work Sanibel Island, Florida, USA.

Tyler, T. R., and Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 25, 115–191. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60283-x

Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., and Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 990–1017. doi: 10.1002/job.1946

Wang, L., Law, K. S., Zhang, M. J., Li, Y. N., and Liang, Y. (2019). It’s mine! Psychological ownership of one’s job explains positive and negative workplace outcomes of job engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 104, 229–246. doi: 10.1037/apl0000337

Wang, H., Wang, L., and Liu, C. (2018). Employee competitive attitude and competitive behavior promote job-crafting and performance: A two-component dynamic model. Front. Psychol. 9:2223. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02223

Wang, Z., Xing, L., Xu, H., and Hannah, S. T. (2021). Not all followers socially learn from ethical leaders: The roles of followers’ moral identity and leader identification in the ethical leadership process. J. Bus. Ethics 170, 449–469. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04353-y

Webster, J., Brown, G., Zweig, D., Connelly, C. E., Brodt, S., and Sitkin, S. (2008). Beyond Knowledge Sharing: Withholding Knowledge at Work. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 27, 1–37. doi: 10.1016/S0742-7301(08)27001-5

Xiong Chen, Z., and Aryee, S. (2007). Delegation and employee work outcomes: An examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 226–238. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24162389

Xu, Z., and Li, X. (2021). Knowledge territorial behavior congruence and innovation process: the moderating role of team territorial climate. J. Knowl. Manag. doi: 10.1108/JKM-12-2020-0884

Zalesny, M. D., and Ford, J. K. (1990). Extending the social information processing perspective: new links to attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 47, 205–246. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(90)90037-a

Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., Xu, S., Liu, X., and Newman, A. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of authentic leadership across culture: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pac. J. Manag. doi: 10.1007/s10490-021-09762-0

Zhang, Z., Zhang, L., Xiu, J., and Zheng, J. (2020). Learning from your leaders and helping your coworkers: the trickle-down effect of leader helping behavior. Leadership Organ. Dev. J. 41, 883–894. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-07-2019-0317

Keywords: leader’s territorial behavior, employee’s territorial behavior, perceived insider status, team competitve climate, the trick-down effect

Citation: Li Y, Weng H, Zhu T and Li N (2021) The Trickle-Down Effect of Territorial Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 12:721806. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.721806

Edited by:

Osman Titrek, Sakarya University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Shahnawaz Saqib, Khawaja Freed University of Engineering and Information Technology, PakistanSílvio Manuel da Rocha Brito, Instituto Politécnico de Tomar (IPT), Portugal

Copyright © 2021 Li, Weng, Zhu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Zhu, MTUxNzk1MDAxMzFAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Yi Li

Yi Li Haolin Weng

Haolin Weng Ting Zhu

Ting Zhu Na Li

Na Li