- 1School of Education Science, Jilin Normal University, Siping, China

- 2Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 3Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 4Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 5School of Mathematics, Jilin Normal University, Siping, China

Although previous research shows that general self-efficacy is related to employability, the mechanism of them is unclear. Thus, this study aims to explore the relationship between general self-efficacy and employability, examines the mediating role of achievement motivation and career aspirations among financially underprivileged college students in China. The analysis of 651 participants (59% female, 41% male) from six provinces indicates that general self-efficacy positively predicts employability through the mediating chain of achievement motivation and career aspirations. Based on these findings, the researchers propose feasible suggestions for related issues of financially underprivileged college students and future research.

Introduction

Scholars from several disciplines have focused on the development of students’ employability skills. Crucial factor of employability directly affects the success of university students in employment (Lau et al., 2014), and is a core competency to secure students a job (Harvey, 2001). Research has confirmed the importance of improving students’ employability (Sin et al., 2017) to facilitate their successful employment (Gbadamosi et al., 2015). As internal factors (Abele and Spurk, 2009; Millard, 2020) affect the development of students’ employability, therefore, this study further explores the internal determinants of university students’ employability.

Studies at financially underprivileged college student groups (Hu et al., 2020) found that employability is a key factor that enables students to achieve career success regarding career choice and access to employment opportunities (Flores et al., 2017; Eimer and Bohndick, 2021). In China, financially underprivileged college students are identified via the document “Guidance on Carefully Identifying Students from Families with Economic Difficulties in Higher Education” (Education and Finance No. 8, 2007). It is jointly issued by the Chinese Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Finance, stating that students from families with economic difficulties are those who struggle to cover their basic study and living expenses during their school years with the resources available to them and their families. Researchers define financially underprivileged college students based on their family’s financial income, providing that most are unable to afford university-related expenses, which means financial difficulties in maintaining the normal study and living expenses at their institution (Zhang et al., 2021). Several studies have suggested that compared to non-financially underprivileged college students, financially underprivileged college students show low self-confidence and poor employability (Cheng and Dong, 2016; Zhang and Chang, 2019; Gan and Wang, 2021). Indeed, employability is crucial for financially underprivileged college students to escape poverty through gainful employment, but only a few studies have examined the antecedent variables of employability and their development mechanisms, therefore, this study will examine the underlying mechanisms of employability enhancement among that group.

According to Bandura (1977) social cognitive theory (SCT), personal attributes, environmental influences, and intentional behaviors are interlinked (Cupani et al., 2010). That is, personal behaviors are formed through the interaction between personal thoughts and environmental emotions (Peng et al., 2018). Based on SCT, social cognitive career theory (SCCT) clarifies the relationship between influences in occupational domain and career development (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 2006; Burga et al., 2020), which focuses on individuals’ ability to shape their occupational behaviors. Self-efficacy refers to a student’s beliefs about their successful performance, education-related behaviors and abilities, which is an important factor to initiate spontaneous motivation and engagement in learning (Parker et al., 2006). A lack of self-efficacy poses a barrier to successful integration into a profession, for example, some graduates have difficulty in successfully embarking on their careers (Swanson and Fouad, 2015). As there is a lack of research applying SCCT theory to general self-efficacy and employability, this study attempts to based on that to explore the mechanisms of general self-efficacy on employability.

Moreover, in SCCT, achievement motivation is an internal drive for individuals to pursue excellence and strive for success, which motivates people to act (Yeh et al., 1992). In addition, career ambition is a protective factor for employability, and plays a crucial role in career development behavior so that influences career development (Super et al., 1990). Related studies have shown that higher levels of career ambition is associated with higher employability (Gbadamosi et al., 2015). However, previous studies have neglected general self-efficacy, achievement motivation, career ambition and employability in applying SCCT theory to the mechanisms of employability among college students. Therefore, this study aims to explore how the general self-efficacy of financially underprivileged college students influences achievement motivation, which subsequently affects career aspirations and employability, based on the pathway construct of employability formation provided by SCCT.

Literature Review

Theoretical Background of Social Cognitive Career Theory

According to SCCT, the core elements that drive career/employment behaviors are self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and choice of goals (Lent et al., 1994), the chain among these elements further addresses how individuals achieve career development success. Thus, SCCT forms the theoretical basis as assessing self-efficacy for employability in this study (Lent et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021).

SCCT is an empirically validated model that has been widely accepted (Brown et al., 2011; Duffy et al., 2014; Burga et al., 2020). According to Lent et al. (1994), self-efficacy is the key component of SCCT and directly affects behavior (Brown et al., 2011; Duffy et al., 2014). Outcome expectation represents a person’s judgment of the consequences resulting from the execution or non-execution of a specific behavior (Brown et al., 2011; Caesens and Stinglhamber, 2014; Duffy et al., 2014). According to SCCT, self-efficacy helps to determine outcome expectations. They are both precursors to goals and jointly lead to choice goals (Lent et al., 1994).

Although various SCCT studies have included outcome expectations, the operationalization of that structure has varied. Many of the measures used are based on success-related expected outcomes in a specific domain, particularly in the form of self-outcomes (e.g., intrinsic motivation or rewards; see Lent and Brown, 2006). The pattern of manifestation of outcome expectations can be embodied as an achievement motive and the goals represented by career aspirations can directly impact behavior.

Specifically, the theory is based on the core cognitive variable of self-efficacy, which facilitates the establishment of choice goals, and thus, choice behavior through the role of outcome expectations. However, the mechanisms by which general self-efficacy affects employability been overlooked in previous studies Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationship between general self-efficacy and the employability of financially underprivileged college students, through the mediating role of achievement motivation and career aspirations.

Employability

Employability is a key factor for individuals in the labor market (Fugate et al., 2004), as universities and individuals are interested in improving the employability of graduates, it has received significant attention in higher education. Fugate et al. (2004) refer to employability as a person’s ability to identify and realize career opportunities. Employability is a personal characteristic (Fugate et al., 2004; Vermeulen et al., 2018; Shahzad et al., 2020) that describes the capability of a person to become and remain employable.

Most studies on the employability of financially underprivileged college students have focused on financial support (Castleman and Long, 2016; Melguizo et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021) and mental health (Lynch et al., 2000; Dixon and Kurpius, 2008; Cheng and Zhang, 2018). On the one hand, several studies have discussed the impact of mental toughness and positive psychology on individual career development (Wang et al., 2021; Xue, 2021). On the other hand, there were studies indicating that externally acquired assistance, such as student loans, fail to fundamentally extricate these students from poverty (Huang et al., 2017). Considering numerous researches have provided significant effects of intra-individual factors, such as career self-efficacy, on employability (Magagula et al., 2020), therefore, this study aim to explore the impact of intra-individual factors on employability among financially underprivileged college students.

Researchers Pan and Lee (2011) focused on measuring employability from the perspectives of general ability, professional ability, work attitude, career planning ability, and confidence. Numerous researchers developed employability measurement tools for Chinese college students according to their characteristics, of which largely focused on the aspect of meeting job search needs. Specially, Wang (2006) developed an employability scale for college students comprising four dimensions as self-awareness, communication and cooperation, cognitive ability, and individual reliability, which fits the characteristics of the sample in this study. Thus, this study adopts Wang Yuan’s employability scale.

General Self-Efficacy

The personal perception of efficacy may further determine the types of activities chosen, the effort to be expended, and the degree of persistence in the effort (Bandura, 1977). In terms of theoretical foundations, the self-efficacy theory emphasizes that the stronger the individual’s belief in their ability to perform a set of actions, the more likely they will initiate and persist in the given activity. In terms of relevant empirical research, Ferris et al. (2017) confirmed the positive link between self-efficacy and related outcomes by several meta-analyses, such as work performance, athletic performance, and academic accomplishment. Accordingly, Self-efficacy can be general or task-specific, allowing individuals to have a range of simultaneous self-efficacy beliefs.

General self-efficacy beliefs mirror the definition provided by Bandura (1977), “the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations.” General self-efficacy, which is unspecific, concerns an individual’s self-belief that they can complete any set task at any time. A previous study found that individuals’ role breadth self-efficacy was positively related to their perceived employability (Hanzla et al., 2019). Besides that, researchers have explored the relationship between self-efficacy and employability using Chinese postgraduate students as subjects and suggested that self-efficacy positively predicted employability (Zhong et al., 2020). Moreover, Yan et al. (2019) found that university students’ self-efficacy in career decision-making positively predicted employability.

Research has found that college students’ self-efficacy during job searches positively predicts employment outcomes (Moynihan, 2003). For example, job seekers with low job search self-efficacy tend to adopt ineffective job search techniques and approaches (Wanberg et al., 1999). In addition to that, studies based on SCCT have found a significant positive correlation between self-efficacy and employability (Liu et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: General self-efficacy positively predicts employability.

Achievement Motive

The achievement motivation theory developed by Atkinson and McClelland (Atkinson and John, 1957) defines the tendency to approach an achievement task in terms of two motive factors: the motive to approach success and to avoid failure. The expectancy value theory expands on that idea, proposing that behavior is strongly influenced by an individual’s expectancy of outcome, and the subjective value of that successful outcome (Weiner, 1992). Moreover, research also suggests that the expectancy of success will increase a person’s willingness to overcome challenges and struggles (Eccles and Wigfield, 2002).

According to the above arguments, achievement motivation is an internal drive for individuals to excel and succeed, an internal motivator for action (Yeh et al., 1992), and influenced by general self-efficacy. According to the theory of the role of self-efficacy, individuals with high sense of self-efficacy will mobilize all their strengths to overcome difficulties, which serves a key role in the formation of motivation (Bandura, 1977).

General Self-Efficacy-Achievement Motive

Moreover, evidence suggests that different levels of self-efficacy influence motivation, with higher self-efficacy leading to higher levels of motivation, and vice versa (Cui et al., 2017). Additionally, individuals with low self-efficacy have lower personal motivation, and consequently adopt less effective job search skills (Wanberg et al., 1999); higher levels of general self-efficacy also links to higher motivation in goals, allowing greater efforts and persistence through difficulties (Bandura and Wood, 1989).

Achievement Motive-Employability

Furthermore, research has found that higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with higher levels of achievement (Chemers et al., 2001; Torres and Solberg, 2001). Achievement motivation also influences numerous behaviors, especially employability that is significantly impacted (Barron and Harackiewicz, 2001; Diao, 2015). In addition to them, studies based on SCCT suggest that achievement motivation positively predicts academic performance among university students (Caldwell and Obasi, 2010). Therefore, we put forth the following hypothesis:

H2: General self-efficacy positively predicts employability through the mediating role of achievement motivation.

Career Aspirations

Career aspirations are an individual’s goals and expectations for a particular career that determine an individual’s career choice (Gottfredson, 1981). Additionally, career aspirations also can be defined as “an individual’s expressed career-related goals or choices” (Rojewski, 2005) and the significant predictor of later occupational attainment (Holland and Lutz, 1968). Hence this study operationalizes the concept of career aspirations as the individual’s career goals, which is approved by relevant previous researches that it predict future career choices and achievements (Schoon and Polek, 2011).

Moreover, numerous well-established factors influence career aspirations, including family socioeconomic status (SES), ethnicity, and gender. For example, teenagers from higher-income families reported greater intentions to pursue professional careers and continue their education than teenagers from lower-income families (Ashby and Schoon, 2010; Mau and Bikos, 2011), further, college students and females tend to report lower career ambitions than men (Danziger and Eden, 2007).

General Self-Efficacy—Career Aspirations

Career ambition is seen as an indicator of students’ future career success (Drai et al., 2018). Mau and Li (2018) found that self-efficacy positively predicted students’ career ambitions. Further, individuals with high levels of self-efficacy tend to have strong levels of ambition, that is, self-efficacy predicts the strength of ambition (Super et al., 1990). Additionally, research on disadvantaged youth’s career aspirations who are in low SES also emphasized the effect between general self-efficacy and career aspirations (Direnzo et al., 2013). Thus, it can be seen that the positive effects of general self-efficacy and various task efficacies on work and career outcomes have been addressed, the latter specifically including job performance and career success (Locke et al., 1984; Saks, 1995; Abele and Spurk, 2009).

Career Aspirations—Employability

Teenage ambition predicts adult occupational attainment (Mello, 2008) and future occupational status (Schoon and Parsons, 2002). Simultaneously, career ambition is a protective factor for employability. That is, ambition plays a vital role in career development behavior and influences individual career development (Super et al., 1990). Further, higher levels of career ambition are associated with higher employability (Gbadamosi et al., 2015), with career ambition positively predicting employability (Drai et al., 2018).

General Self-Efficacy—Career Aspirations—Employability

Numerous researches have shown that career self-efficacy is a positive predictor of career aspirations (Hartman and Barber, 2019). Specifically, when individuals are more confident, they persist in overcoming difficulties and tend to adopt behaviors that contribute to their career success (Johnson et al., 2010), which also shows such individuals understand the importance of engaging in behaviors that would help them achieve desired outcomes (Bandura, 1977, 2006). Thus, enhancing individuals’ self-efficacy beliefs affects how they behave and strive toward success (Johnson et al., 2010). Moreover, considering a study using SCCT theory revealed that parental variables influence adolescents’ career ambitions and career behaviors (planning and exploration) through self-efficacy (Sawitri et al., 2014), therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H3: General self-efficacy mediates the employability relationship through career aspirations.

Achievement Motivation—Career Aspirations

In addition, career aspirations may also mediate the relationship between achievement motivation and employability. Career aspirations are closely linked to an individual’s aspirations, beliefs, and achievement motivation, all of which govern behaviors toward goal attainment (Rojewski, 2005). In addition to that, career aspirations are positively related to achievement motivation. And the choice of career goals (career aspirations) are not only significantly influenced by outcome expectations (achievement motivation) (Li, 2005), but also mediate the relationship between achievement motivation and other career adjustment variables (Wigfield et al., 2002).

Researchers define aspirations or career motivation as the extent to which individuals desire promotion and recognition (Peters et al., 2013). Considering expectancies predict occupational ambitions (Nauta and Epperson, 2003), therefore, we put forth the following hypothesis:

H4: Career aspirations are an essential mediator of achievement motivation affecting employability, and achievement motivation positively predicts career aspirations.

In summary, this study aims to examine the role of general self-efficacy as a predictor of employability based on SCCT and, analyze the mediating role of achievement motivation and career aspirations in the relation between general self-efficacy and employability.

Methodology

Participants and Sampling

Convenience sampling method was employed in this study, recruiting freshmen and sophomore students from nine colleges and universities, including Beijing United University, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Jilin Normal University, Inner Mongolia University of Finance and Economics, Shenyang University of Technology, Changchun Normal University, Jilin Agricultural University, Anhui University of Science and Technology, and Huaiyin Normal University, from the Jilin, Beijing, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Shandong and Anhui Provinces, respectively. Questionnaires were distributed via the Questionnaire Star app, and 2,695 questionnaires were collected. A total of 2,485 questionnaires were valid, yielding a return rate of 92.2%. Based on the definition of financially underprivileged college students in this study, 651 poor university students (26.2% of the total number of students; 59% female; 41%male) were screened according to whether their families applied for financial hardship certificates from their local governments or student loans from their schools.

Measures

Employability

The employability scale, developed by Wang (2006), consists of 23 items that measure four dimensions of employability: cognitive ability, individual reliability, communication and cooperation, and self-awareness. Cognitive ability includes items such as, “I can acquire new knowledge and skills quickly” and “I can reason logically.” These items assess the individual’s understanding and awareness of knowledge, society, and problem areas. The scale is scored on a seven-point Likert scale, with 1 being “completely disagree” and 7 being “completely agree.” Higher scores indicate greater employability. The employability scale displayed good reliability and validity in various studies assessing the employability of college students (Chen and Li, 2011). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.962.

General Self-Efficacy

The general self-efficacy scale was developed by Schwarzer et al. (1997) and revised by Wang et al. (2001). It is a unidimensional scale with 10 items; for example, “I can solve my problems if I do my best” and “I am confident that I can deal effectively with difficulties.” Answers are scored on a four-point Likert scale, with 1 being “completely incorrect” and 4 being “completely correct.” The total score is obtained by summing the scores of all 10 questions and dividing the value by the number of questions, with higher scores indicating higher general self-efficacy. Liang and Su (2011) applied this scale to measure the general self-efficacy of university students. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.892.

Achievement Motivation

The Achievement Motivation Scale was developed by Gjesme and Nygard in 1970 and revised by Yeh et al. (1992) It comprises 30 questions divided into two equal subscales of motivation to pursue success and to avoid failure. The success-seeking motivation score minus the failure-avoidance motivation score represents the total achievement motivation score. Items regarding motivation for success include, “I like to persevere in problems that I am unsure I can solve” and “I enthusiastically face issues that I am not sure I can overcome.” Answers were rated on a four-point Likert scale, with 1 being “completely incorrect” and 4 being “completely correct.” Higher scores indicated stronger achievement motivation. The Achievement Motivation Scale exhibited good reliability and validity in various studies assessing college students’ achievement motivation (Shen et al., 2013). Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.883.

Career Aspirations

The Career Aspirations Scale, developed by Wang (2008), comprises 25 items with six dimensions: job satisfaction, interpersonal relationships, degree of challenge, contribution to society, work environment, and development prospects. Items regarding degree of challenge and job satisfaction include, “My job fosters creativity,” “My job has high social status,” and “My job is challenging.” Answers are rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 5 indicating “extremely important” and 1 indicating “unimportant.” Higher scores indicated greater importance attached to the occupational characteristics represented by the item. Chen and Li (2011) applied this scale to examine career ambition. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.913.

Data Processing

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 and Mplus 7.0 were used for assessing internal consistency, descriptive statistics, and correlation analyses of the scales. SPSS Process components were used for chain mediation tests and bootstrap analysis.

Results

Common Method Deviation Test

The Harman one-factor approach was used to test for common method bias, and exploratory factor analysis was conducted regarding the four study variables. The results revealed 15 factors that could be analyzed with a characteristic root greater than 1. The first common factor had an explanatory rate of 23% (< 40%), which indicated that there was no serious problem of common method bias in this study.

Differences in Demographic Variables Among Financially Underprivileged College Students

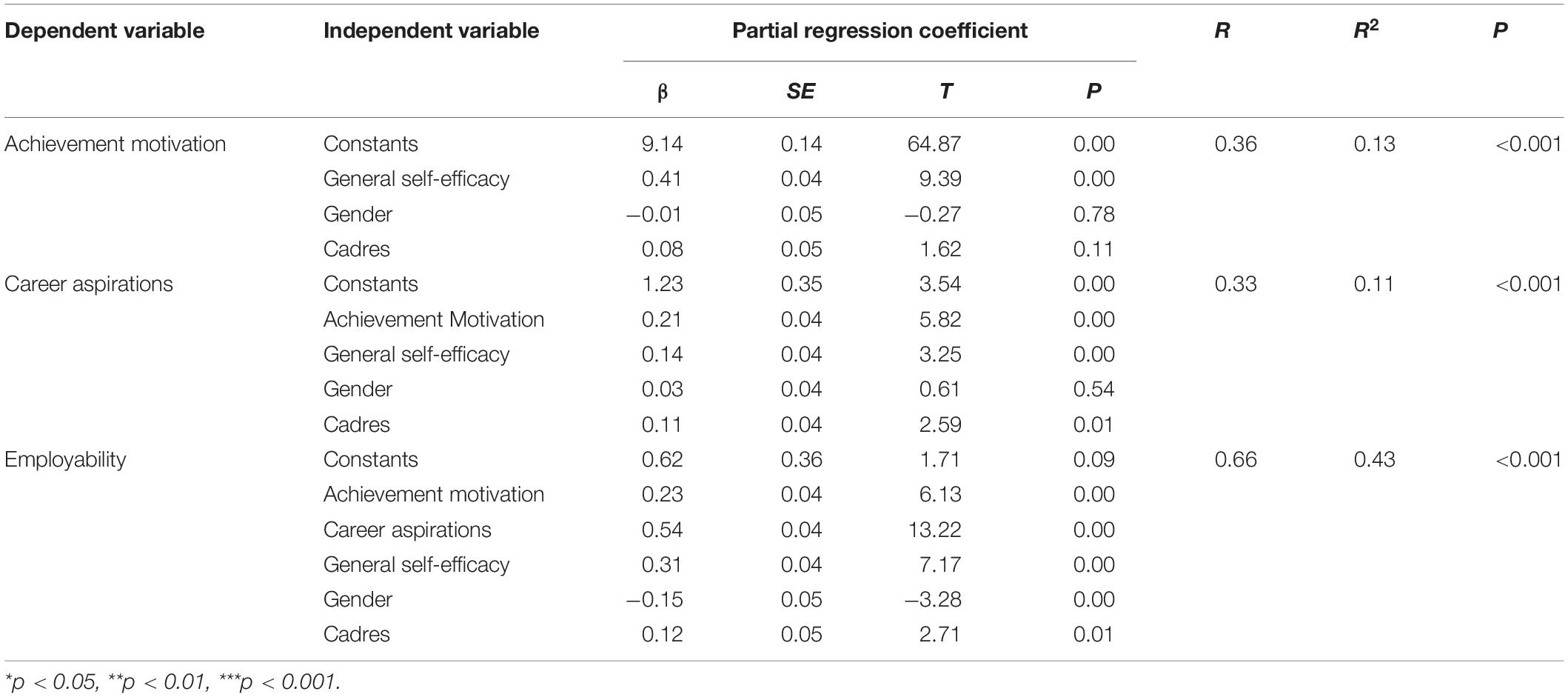

Demographic characteristics including gender, major, and year of study were used as grouping variables. Independent sample t-tests and ANOVA were conducted on employability, career aspirations, general self-efficacy, and achievement motivation among financially underprivileged college students (Table 1).

Table 1. Financially underprivileged college students’ basic information table for each variable (n = 651).

The independent-samples t-test showed that employability scores were higher for those who were class officers (M = 5.71, SD = 0.71) than those not (M = 5.42, SD = 0.74), t = 4.982, p < 0.01, and males (M = 5.68, SD = 0.77) had higher employability scores than females (M = 5.46, SD = 0.71), t = 3.807, p < 0.05. Apart from that, other variables were not significantly different (p > 0.05).

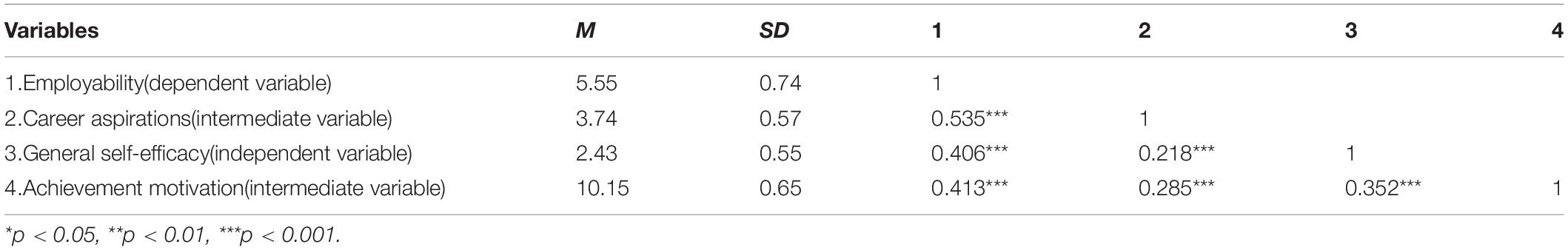

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

General self-efficacy, achievement motivation, career aspirations, and employability were correlated. Pearson product difference correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationship between self-efficacy and employability, and the results showed a significant positive correlation. The specific effects of the correlation analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Correlation analysis of the variables of financially underprivileged college students (n = 651).

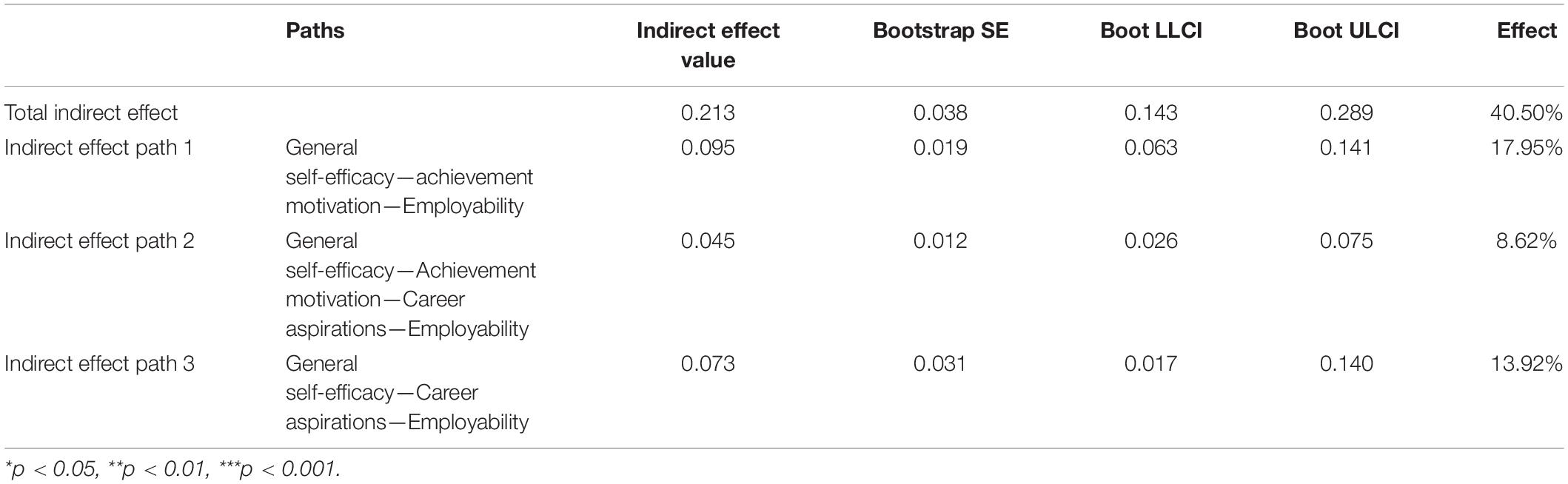

The Relationship Between General Self-Efficacy and Employability: A Test of Chain Mediating Effects

General self-efficacy as the independent variable, achievement motivation and career aspirations as mediating variables, and employability as the dependent variable were used to develop a model, hence further explore the relationship among general self-efficacy, achievement motivation, career aspirations, and employability. Since gender and status as a class officer impacted employability, these factors were included as control variables in the structural equation model. The mediating effect was estimated by 5,000 samples with 95% confidence interval according to the sequential test and bootstrap method as recommended by Wen and Ye (2014).

Sequential tests results (Table 3) indicated that general self-efficacy significantly and positively predicted achievement motivation. Achievement motivation and general self-efficacy simultaneously predicted career aspirations, significantly as well as positively. When general self-efficacy, achievement motivation, and career aspirations were included in the regression equation simultaneously, all three had a significant positive predictive effect on employability. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was validated.

The direct test for mediating effects (Table 4) revealed that the bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the total indirect effect generated by achievement motivation and career aspirations did not contain a value of 0. That is, both mediating variables had a significant mediating effect on the relation between general self-efficacy and employability.

Table 4. Chain mediating effects of achievement motivation and career aspirations on the relationship between general self-efficacy and employability.

That mediating role comprises three indirect effects. First, the confidence interval for the indirect effect generated by the general self-efficacy–achievement motivation–employability pathway does not contain a value of 0 (0.095, 17.95% of the total effect), indicating that the indirect effect generated by this pathway was significant. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Second, the confidence interval for the indirect effect arising from the general self-efficacy–achievement motivation–career aspiration–employability pathway did not contain a value of 0 (0.045, 8.62% of the total effect) and reached a significant level. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was validated.

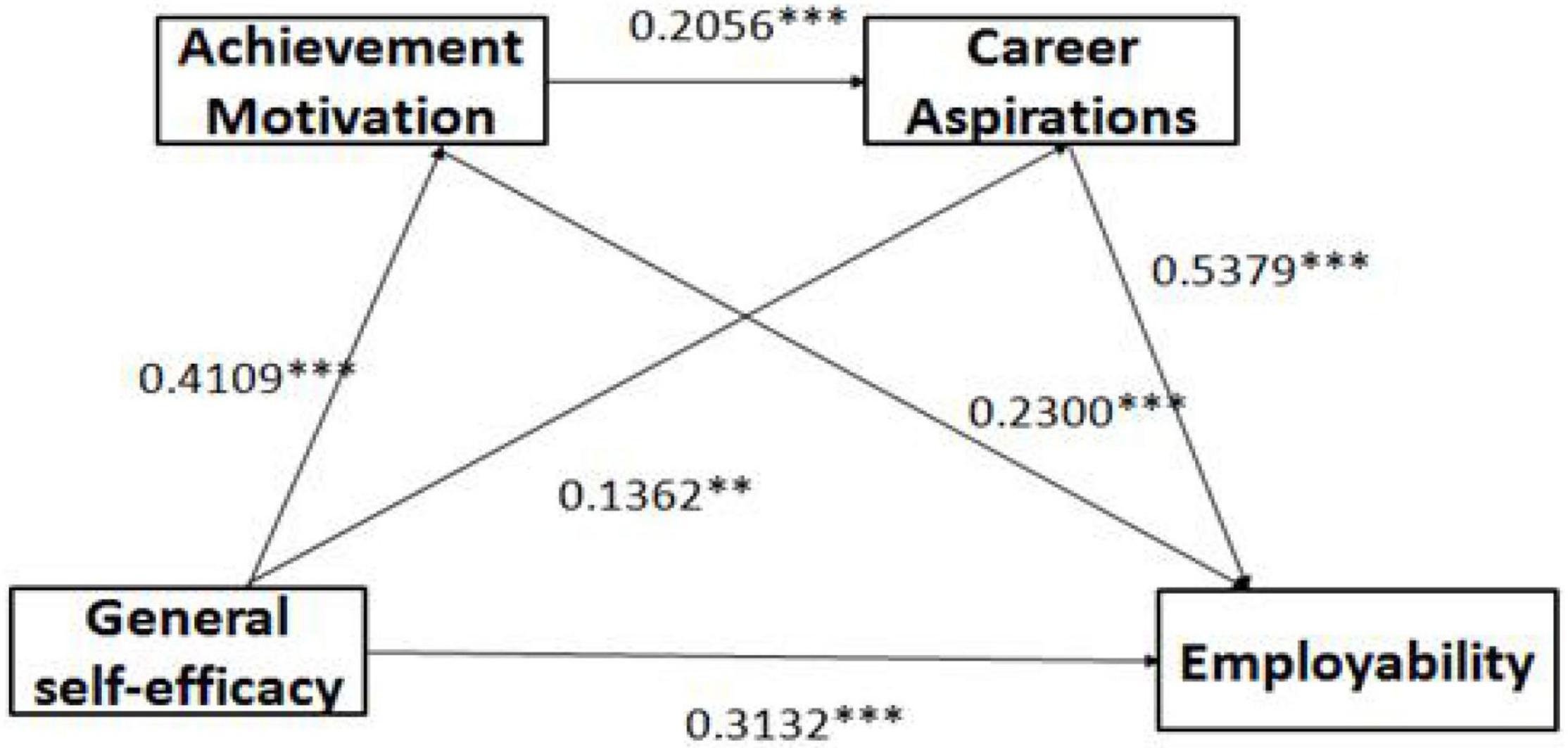

Finally, the indirect effect of the general self-efficacy–career aspiration–employability pathway had a confidence interval not containing a zero value, indicating that career aspiration had a significant mediating effect between general self-efficacy and employability (0.073, accounting for 13.92% of the total effect). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 holds true. The relationship between the variables is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Relationship between general self-efficacy and employability: the chain mediating role of achievement motivation and career aspirations. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

From the above analysis, the relationship among the variables is shown in Figure 1.

Conclusion

Discussion

In previous discussions of student employability, various studies have focused on the antecedents of students’ individual behavior patterns and cognition (Cacciolatti et al., 2017; Blázquez et al., 2018). This study takes financially underprivileged Chinese college students as a research sample to verify whether general self-efficacy positively influenced employability, assuming general self-efficacy has a direct effect on achievement motivation, career ambition, and employability in the SCCT model.

Based on our research findings, this study provides the following contributions. First, we validated the applicability of SCCT in China. Specifically, the operational variables of SCCT—outcome expectancy and choice of goal—as well as the role of general self-efficacy on employability, were explored regarding the characteristics of financially underprivileged college students in China. We thus developed a model of the influence mechanism of employability among this population: general self-efficacy influences employability through the chain mediating role of achievement motivation and career ambition. The proposed mechanism of influence of quantitative research results on employability validates the applicability of the SCCT model to a group of financially underprivileged college students in China.

Second, previous researches on SCCT have mostly focused on the influence of environmental factors, with few studies examining the intrinsic psychological mechanisms of individuals (Rasdi and Ahrari, 2020). This study aims to enrich SCCT theory by exploring how the core cognitive variables of self-efficacy, achievement motivation, and career aspirations interact to influence employability among financially underprivileged college students.

Third, most previous studies on SCCT have been conducted from a cross-national or cross-cultural perspective (Alessandro et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2021), but only a few studies focusing on socioeconomic status (Flores et al., 2017). This study aims to advance SCCT theory and thus provide a direction for future research that focuses on enhancing the employability of financially underprivileged college student groups by SCCT parameters.

The results indicate that there was a significant positive relationship among general self-efficacy, achievement motivation, career aspirations, and employability. Specifically, consistent with existing research, this study confirms that general self-efficacy positively predicted employability (Zhong et al., 2020), via achievement motivation (Chemers et al., 2001; Torres and Solberg, 2001), and also facilitated the establishment of career aspirations (Mau and Li, 2018).

Moreover, the results indicate general self-efficacy can promote employability by enhancing the achievement motivation of underprivileged university students. The higher the general self-efficacy, the more challenging the chosen tasks and the more motivated the individuals (Chi and Xin, 2006). People with high achievement motivation harness their capabilities to improve their self-employability (Cui et al., 2017).

Our results also find that general self-efficacy can influence employability through its role in career aspirations. Individuals’ occupational goals effectively predict their employability and mediate the relationship between general self-efficacy and employability (McArdle et al., 2007). Individuals with strong career aspirations are willing to put in more effort and persist in their actions, all of which are conducive to employability (Gbadamosi et al., 2015).

Besides, this study found that achievement motivation and career aspirations mediated the link between general self-efficacy and employability. That is, the higher the general self-efficacy, the more challenging the chosen tasks and the stronger the motivation (Chi and Xin, 2006). Additionally, achievement motivation was an important factor influencing financially underprivileged college students’ academic and career development (Yang et al., 2016). Moreover, career aspirations served as a predictor for employability (Hasan, 2006).

Implications

The study offers the following insights as a reference for universities to enhance the employability of underprivileged university students.

First, the results validated Lent et al. (1994) SCCT model which emphasizes the three core concepts of self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and choice of goals as the driving mechanisms that prompt career behavior. We thus demonstrated the importance of the interaction mechanisms of those three core variables among financially disadvantaged university students in China. Further, we confirmed that general self-efficacy influences employability through the mediating role of achievement motivation and career aspirations thus supporting the validation and application of the SCCT in the Chinese context.

Second, our findings provide a pathway for employment guidance among poor university students. This study constructs a model of the mechanisms influencing the employability of financially underprivileged college students from the perspective of their cognitions and, explores the pathway to the formation of their employability. According to our results, universities can enhance the general self-efficacy of financially underprivileged college students to stimulate achievement motivation. Thus, they can establish clear and explicit action goals for job searches to enhance the students’ career ambitions, thereby improving employability. The proposed influence mechanism of employability provides a reference path for colleges and universities to effectively conduct career guidance work.

The third is the enrichment of future research directions. Employability is an important contributor to the career development of underprivileged university students. However, there is a lack of research on their general self-efficacy and employability. Moreover, the indicators of their employability have not received sufficient attention in previous studies, and the mechanism of the role of employability also has not been explored under a more complete system. Our findings can therefore help operationalize the research concept and provide a valid measure of a particular psychological characteristic of the target population through a survey. Furthermore, through the questionnaire method, the data collected can accurately indicate the relationship among the variables and construct a theoretical model of the influence mechanism between the independent and dependent variables.

Research Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations.

First, this study focuses on the influence of intra-individual psychological influences on employability. In future research, the formation of employability among financially underprivileged college students must be explored from the perspective of external influences to comprehensively construct the formation mechanism of employability.

Second, due to time and space constraints, only six universities were considered in this study, with 615 valid questionnaires and an undifferentiated study area. Scholars believe that gender is also an important factor affecting employability; thus, future studies can expand the sample size to improve research representativeness.

Third, this study takes a cross-sectional approach, which recommended subsequent researches to explore the mechanisms of employability through longitudinal studies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

ZQ played a guiding role in researching. DW mainly took charge of writing. CS and LH mainly took charge of data analysis. DG mainly took charge of language polishing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Education Science “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” Key Project of the Ministry of Education (Project Approval No. DIA200343) and the Scientific Research Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Education (Project Approval No. JJKH20210470SK).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abele, A. E., and Spurk, D. (2009). The longitudinal impact of self-efficacy and career goals on objective and subjective career success. J. Vocat. Behav. 74, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.10.005

Alessandro, L. P., Kaisa, T., and Sara, P. (2018). “Because I am worth it and employable”: a cross-cultural study on self-esteem and employability orientation as personal resources for psychological well-being at work. Curr. Psychol. 39, 1785–1797. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9883-x

Ashby, J. S., and Schoon, I. (2010). Career success: the role of teenage career aspirations, ambition value and gender in predicting adult social status and earnings. J. Vocat. Behav. 77, 350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.06.006

Atkinson, and John, W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol. Rev. 64, 359–372. doi: 10.1037/h0043445

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-eff. Beliefs Adolescen. 5, 307–337.

Bandura, A., and Wood, R. (1989). Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 805–814. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.5.805

Barron, K. E., and Harackiewicz, J. M. (2001). Achievement goals and optimal motivation: testing multiple goal models. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80, 706–722. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.706

Blázquez, M., Herrarte, A., and Llorente-Heras, R. (2018). Competencies, occupational status, and earnings among European University graduates sciencedirect. Eco. Edu. Rev. 62, 16–34. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.10.006

Brown, S. D., Lent, R. W., and Telander, K. (2011). Social cognitive career theory, conscientiousness, and work performance: a meta-analytic path analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.11.009

Burga, R., Leblanc, J., and Rezania, D. (2020). Exploring student perceptions of their readiness for project work: utilizing social cognitive career theory. Proj. Manag. J. 51, 154–164. doi: 10.1177/8756972819896697

Cacciolatti, L., Lee, S. H., and Molinero, C. M. (2017). Clashing institutional interests in skills between government and industry: an analysis of demand for technical and soft skills of graduates in the UK. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chan. 119, 139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.024

Caesens, G., and Stinglhamber, F. (2014). The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: the role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 64, 259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2014.08.002

Caldwell, T., and Obasi, E. M. (2010). Academic performance in african american undergraduates: effects of cultural mistrust, educational value, and achievement motivation. J. Career Dev. 36, 348–369. doi: 10.1177/0894845309349357

Castleman, B., and Long, B. T. (2016). Looking beyond Enrollment: the Causal Effect enrollment: the causal effect of Need-Based Grantsneed-based grants on College Access, Persistence college access, persistence, and Graduation graduation. J. Labor Eco. 34, 1023–1073. doi: 10.1086/686643

Chemers, M. M., Hu, L. T., and Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first-year college student performance and adjustment. Educ. Psychol. 93, 55–64. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.55

Chen, J., and Li, W. (2011). A study on the relationship between college students‘students’ career values, self-efficacy and employability. Explor. Higher Educ. 5, 106–110. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-9760.2011.05.023

Cheng, G., and Zhang, D. (2018). The effect of family socio economic status on depression in college freshmen: a mediated model with moderation. Psychol. Behav. Res. 16, 247–252. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2018.02.015

Cheng, L., and Dong, K. (2016). A study on the employability of poor college students - A case study of local undergraduate universities. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 36, 95–99. doi: 10.15896/j.xjtuskxb.201603013

Chi, L. P., and Xin, Z. Q. (2006). Measures of college students‘ students’ motivation and its relationship with self-efficacy. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 22, 64–70. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4918.2006.02.012

Cui, Y., Xu, F., Cui, L., and Cui, Y. (2017). The relationship between achievement motivation, career choice efficacy and employability among medical students. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 4, 86–90.

Cupani, M., Minzi, M., Pérez, E. R., and Pautassi, R. M. (2010). An assessment of a social–cognitive model of academic performance in mathematics in Argentinean middle school students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 20, 659–663. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.03.006

Danziger, N., and Eden, Y. (2007). Gender-related differences in the occupational aspirations and career-style preferences of accounting students: a cross-sectional comparison between academic school years. Career Dev. Int. 12, 129–149. doi: 10.1108/13620430710733622

Diao, X. (2015). Research on career counseling model for poor college students in the perspective of career decision-making. China Adult Educ. 20, 41–43.

Direnzo, M. S., Weer, C. H., and Linnehan, F. (2013). Protégé career aspirations: the influence of formal e-mentor networks and family-based role models. J. Vocat. Behav. 83, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.02.007

Dixon, S. K., and Kurpius, S. (2008). Depression and college stress among university undergraduates: do mattering and self-esteem make a difference? J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 49, 412–424. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0024

Drai, M. U., Petrovi, I. B., and Vukeli, M. (2018). Career ambition as a way of understanding the relation between locus of control and self-perceived employability among psychology students. Front. Psychol. 9:1729. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01729

Duffy, R. D., Bott, E. M., Allan, B. A., and Autin, K. L. (2014). Exploring the role of work volition within social cognitive career theory. J. Career Assess 22, 465–478. doi: 10.1177/1069072713498576

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 109–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Eimer, A., and Bohndick, C. (2021). How individual experiential backgrounds are related to the development of employability among university students. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Emp. 12, 114–130. doi: 10.21153/jtlge2021vol12no2art1011

Ferris, D. L., Johnson, R. E., and Sedikides, C. (2017). The self at work: fundamental theory and research. Abingdon: Routledge.

Flores, L. Y., Navarro, R. L., and Ali, S. R. (2017). The state of scct research in relation to social class: future directions. J. Career Assess 25, 6–23. doi: 10.1177/1069072716658649

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., and Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: a psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

Gan, N., and Wang, X. (2021). Review and prospect of research on poor college students in China (1994–2020). Jiangsu High. Educ. 5, 62–67. doi: 10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2021.05.008

Gbadamosi, G., Evans, C., Richardson, M., and Ridolfo, M. (2015). Employability and students’ part-time work in the uk: does self-efficacy and career aspiration matter? Br. Educ. Res. J. 41, 1086–1107. doi: 10.1002/berj.3174

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and compromise: a developmental theory of occupational aspirations. J. Couns. Psychol. 32, 152–159. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.28.6.545

Hanzla, A., Shahid, N., and Muhammad, I. R. (2019). Self-efficacy, self-esteem, and career success: the role of perceived employability. J. Manag. Sci. 6:6202.

Hartman, R. L., and Barber, E. G. (2019). Women in the workforce : the effect of gender on occupational self-efficacy, work engagement and career aspirations. Gender Manag. Int. J. 35:62. doi: 10.1108/GM-04-2019-0062

Harvey, L. (2001). Defining and measuring employability. Qual. High. Educ. 7, 97–109. doi: 10.1080/13538320120059990

Hasan, B. (2006). Career maturity of indian adolescents as a function of self-concept, vocational aspiration and gender. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 32, 127–134.

Holland, J. L., and Lutz, S. W. (1968). The predictive value of a student’s choice of vocation. Pers. Guid. J. 46, 428–434. doi: 10.1002/j.2164-4918.1968.tb03209.x

Hu, S., Hood, M., Creed, P. A., and Shen, X. (2020). The relationship between family socioeconomic status and career outcomes: a life history perspective. J. Career Dev. 2020:76. doi: 10.1177/0894845320958076

Huang, W., Li, F., Liao, X., and Hu, P. (2017). More money, better performance? the effects of student loans and need-based grants in china’s higher education. China Econ. Rev. 51, 208–227. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2017.09.005

Johnson, R. D., Stone, D. L., and Phillips, T. N. (2010). Relations among ethnicity, gender, beliefs, attitudes, and intention to pursue a career in information technology. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 38, 999–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00336.x

Lau, H. H., Hsu, H. Y., Acosta, S., and Hsu, T. L. (2014). Impact of participation in extra-curricular activities during college on graduate employability: an empirical study of graduates of taiwanese business schools. Educ. Stud. 40, 26–47. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2013.830244

Lent, R. W., and Brown, S. D. (2006). Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: a social-cognitive view. J. Vocat. Behav. 69, 236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.006

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., and Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 45, 79–122. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Li, Y. (2005). Major and career choice among Chinese university students - an analysis based on social cognitive career theory. Beijing: Beijing Normal University.

Liang, B., and Su, C. (2011). The relationship between general self-efficacy coping style and mental health of freshmen from sichuan earthquake stricken area. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 19, 669–671.

Liu, X., Peng, M. Y. P., Anser, M. K., Chong, W. L., and Lin, B. (2020). Key teacher attitudes for sustainable development of student employability by social cognitive career theory: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and problem-based learning. Front. Psychol. 11:1945. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01945

Locke, E. A., Frederick, E., Lee, C., and Bobko, P. (1984). Effect of self-efficacy, goals, and task strategies on task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 69, 241–251. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.241

Lynch, J. W., Smith, G. D., Kaplan, G. A., and House, J. S. (2000). Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 320, 1200–1204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1200

Magagula, K., Maziriri, E. T., and Saurombe, M. D. (2020). Navigating on the precursors of work readiness amongst students in johannesburg. South Africa. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 46, 1–11. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1778

Mau, W. C., and Bikos, L. H. (2011). Educational and vocational aspirations of minority and female students: a longitudinal study. J. Couns. Dev. 78, 186–194. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02577.x

Mau, W. J., and Li, J. (2018). Factors influencing STEM career aspirations of under represented high school students. Career Dev. Q. 66, 246–258. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12146

McArdle, S., Waters, L., Briscoe, J. P., and Hall, D. T. (2007). Employability during unemployment: adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. J. Vocat. Behav. 71, 247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.003

Melguizo, T., Sanchez, F., and Velasco, T. (2016). Credit for low-income students and access to and academic performance in higher education in Colombia: a regression discontinuity approach. World Dev. 80, 61–77. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.018

Mello, Z. R. (2008). Gender variation in developmental trajectories of educational and occupational expectations and educational and occupational expectations and attainment from adolescence to adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 44, 1069–1080. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1069

Millard, L. (2020). Students as colleagues: the impact of working on campus on students and their attitudes towards the university experience. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Emp. 11, 37–49. doi: 10.21153/jtlge2020vol11no1art892

Moynihan, R. (2003). Industry group created bogus websites to hijack browsers. BMJ 326:463. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.463/a

Nauta, M. M., and Epperson, D. L. (2003). A longitudinal examination of the social-cognitive model applied to high school girls’ choices of nontraditional college majors and aspirations. J. Couns. Psychol. 50, 448–457. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.4.448

Pan, Y. J., and Lee, L. S. (2011). Academic performance and perceived employability of graduate students in business and management – an analysis of nationwide graduate destination survey. Behav. Sci. 25, 91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.531

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., and Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 636–652. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

Peng, M. Y. P., Sheng-Hwa, T., and Han-Yu, W. (2018). “The impact of professors’ transformational leadership on university students’ employability development based on social cognitive career theory,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology, Okinawa. doi: 10.1145/3206129.3239422

Peters, K., Ryan, M. K., and Haslam, S. A. (2013). Women’s occupational motivation: the impact of being a woman in a man’s world. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rasdi, R. M., and Ahrari, S. (2020). The applicability of social cognitive career theory in predicting life satisfaction of university students: a meta-analytic path analysis. PLoS One 15:e0237838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237838

Rojewski, J. W. (2005). “Occupational Aspirations: Constructs, Meanings, and Application,” in Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, eds S. D. Brown and R. W. Lent. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Saks, A. M. (1995). Longitudinal field investigation of the moderating and mediating effects of self-efficacy on the relationship between training and newcomer adjustment. J. Appl. Psychol. 80, 211–225. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.80.2.211

Sawitri, D. R., Creed, P. A., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., and Peter. (2014). Parental influences and adolescent career behaviours in a collectivist cultural setting. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 14, 161–180. doi: 10.1007/s10775-013-9247-x

Schoon, I., and Parsons, S. (2002). Teenage aspirations for future careers and occupational outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 60, 262–288. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1867

Schoon, I., and Polek, E. (2011). Teenage career aspirations and adult career attainment: the role of gender, social background and general cognitive ability. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 35, 210–217. doi: 10.1177/0165025411398183

Schwarzer, R., Born, A., Iwawaki, S., and Lee, Y. M. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: comparison of the chinese, indonesian, japanese, and korean versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia 40, 1–13.

Shahzad, M., Qu, Y., Ur Rehman, S., Zafar, A. U., Ding, X., and Abbas, J. (2020). Impact of knowledge absorptive capacity on corporate sustainability with mediating role of CSR: analysis from the Asian context. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 63, 148–174. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2019.1575799

Shen, P. Y., Zhang, Z., Wang, L., and Wu, X. F. (2013). The mediating role of achievement motivation in the relationship between Internet addiction and self-esteem among college students. Chin. Sch. Health 3, 260–262.

Sin, C., Tavares, O., and Amaral, A. (2017). Accepting employability as a purpose of higher education? Academics ‘Academics’ perceptions and practices. Stud. High. Educ. 44, 920–931. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1402174

Super, D. E., Savickas, M. L., and Super, C. M. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Career Choice Dev. 16, 282–298. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

Swanson, J. L., and Fouad, N. A. (2015). Career theory and practice: learning through case studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Torres, J. B., and Solberg, V. S. (2001). Role of self-efficacy, stress, social integration, and family support in latino college student persistence and health. J. Vocat. Behav. 59, 53–63. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1785

Vermeulen, B., Kesselhut, J., Pyka, A., and Saviotti, P. P. (2018). The impact of automation on employment: just the usual structural change? Sustainability 10:1661. doi: 10.3390/su10051661

Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., and Rotundo, M. (1999). Unemployed individuals: motives, job-search competencies, and job-search constraints as predictors of job seeking and reemployment. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 897–910. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.6.897

Wang, C. K., Hu, C. F., and Liu, Y. (2001). A study on the reliability and validity of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Appl. Psychol. 1, 37–40. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-6020.2001.01.007

Wang, L. (2008). A study of college students‘students’ career aspirations. Chongqing: Southwest University.

Wang, Y. (2006). A study on the relationship between college students‘students’ career values and employability and employment performance. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University.

Wang, Y. L., Derakhshan, A., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front. Psychol. 12:731721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wen, Z., and Ye, B. (2014). Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: competitors or backups? Acta Psychol. Ogica. Sinica. 46:714. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00714

Wigfield, A., Battle, A., Keller, L. B., and Eccles, J. S. (2002). Sex differences in motivation, self-concept, career aspiration, and career choice: implications for cognitive development. Biol. Soc. Behav. Dev. Sex Diff. Cogn. 21, 93–124.

Xue, L. (2021). Challenges and resilience-building: a narrative inquiry study on a mid-career chinese EFL Teacher. Front. Psychol. 12:758925. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.758925

Yan, H. U., Jing, Y., Cao, X. M., and Education, S. O. (2019). The relationship between college students’ self-efficacy in career decision-making and employability: the intermediary role of career planning. Theory Prac. Educ. 39:3.

Yang, D., Liang, S. C., and Wu, H. M. (2016). The relationship between achievement motivation and burnout among college students: the mediating role of hope. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2, 255–259. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2016.02.026

Yeh, R. M., Kunt, A., and Hagtvet. (1992). Measurement and analysis of achievement motivation. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 8, 14–16.

Zhang, C., Ma, L., and Chen, X. (2021). The impact of financial aid for poor students on college students’ consumption behavior: a study based on campus card consumption data and questionnaire data. Edu. Econ. 37, 80–87.

Zhang, X., and Chang, X. (2019). Mental health education for poor college students in the perspective of positive psychology:reflections and improvements. Jiangsu Higher Educ. 2019, 119–124. doi: 10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2019.05.021

Zhao, W. X., Peng, Y. P., and Liu, F. (2021). Cross-cultural differences in adopting social cognitive career theory at student employability in pls-sem: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and deep approach to learning. Front. Psychol. 12:586839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.586839

Keywords: college students, self-efficacy, employability, achievement, motivation, career, aspirations

Citation: Wang D, Guo D, Song C, Hao L and Qiao Z (2022) General Self-Efficacy and Employability Among Financially Underprivileged Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Achievement Motivation and Career Aspirations. Front. Psychol. 12:719771. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719771

Received: 03 June 2021; Accepted: 13 December 2021;

Published: 21 January 2022.

Edited by:

Ali Derakhshan, Golestan University, IranCopyright © 2022 Wang, Guo, Song, Hao and Qiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhihong Qiao, cWlhb3poaWhvbmdAYm51LmVkdS5jbg==

Dan Wang

Dan Wang Danyang Guo3

Danyang Guo3 Chao Song

Chao Song Lianming Hao

Lianming Hao Zhihong Qiao

Zhihong Qiao