- 1Department of Humanities, Section of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Naples “Federico II”, Naples, Italy

- 2Associazione Maestri di Strada ONLUS, Naples, Italy

Introduction: The professional self is often hindered by a lack of self-care and poor work-life balance, and cannot be considered an unlimited resource. Given this, the reflexive team is an important organizational tool for protecting workers' well-being. The non-profit organization Maestri di Strada (MdS) (“Street Teachers”) conducts action research (AR) in the area of socio-education. The main tool used by the group to protect the well-being of its members is a guided reflexivity group, inspired by the Balint Group and termed the Multi-Vision Group (MG). In March 2020, because of the COVID-19 lockdown, the MdS team had to quickly revamp its working model, and MGs were held online for the first time.

Aim: Through qualitative research that takes a longitudinal approach, the aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of the MG in supporting the team's reflexivity in this new online format.

Methods: This article considers MGs during two different time periods: pre-pandemic (T1) and early pandemic (T2). During T1, the MdS team met 18 times in person, while during T2 the team met 12 times through an online platform (always under the guidance of a psychotherapist). During all sessions in both time periods, a silent observer was present in the meetings, and they subsequently compiled narrative reports. The textual corpora of the reports were submitted for a Thematic Analysis of Elementary Contexts through T-Lab Plus, in order to examine the main content of the groups' discourse.

Results: The results (five clusters in T1; and five in T2) show that, during T2, the group devoted considerable time to experiences tied to the pandemic (T21: schools facing the pandemic crisis; T2.2: the pandemic: death, inner worlds, and thought resistance; T2.3: kids' stories involving physical distancing and emotional proximity). The group also came up with innovative educational initiatives that defied the lockdown (T2.4: fieldwork: the delivery of “packages of food for thought”; T2.5: the MdS group: identity and separation). Based on these findings, the MG most likely contributed to the emergence of MdS as a “resilient community,” capable of absorbing the shock of the pandemic and realizing a fast recovery response.

Introduction

Professional Self, Well-Being, and Teams

Non-profit organizations are steadily becoming a larger presence in Italy (ISTAT, 2020). However, these organizations face considerable difficulties that impact workers' well-being, such as excessive employee turnover, decreased public funding, delays in contract renewals, and a lack of systematic resources for supervision and the kind of reflection that creates team support (Olivieri, 2019).

The professional self, which is closely related to the personal self, has an intersubjective, narrative, discursive, and reflective structure (Manuti, 2006; Fellenz, 2016). It can be harmed by a lack of self-care and by poor work-life balance (Myers et al., 2020). The professional self cannot be considered an unlimited resource, and because of this, team support is particularly important: new ideas and innovation emerge between rather than within people, thereby emphasizing the importance of the social and collective context (Barak et al., 2010).

Initial professional training based on knowledge and skills is not enough to support those who work in challenging environments: “on the one hand, knowledge will not just be out of date, but will always be insufficient to describe the novel and unstable situations that present themselves; on the other hand, skills are always addressed to known situations, and cannot be addressed to unforeseen (and unforeseeable) situations” (Barnett, 2009, p. 439). Training of the kind described by Barnett is very widespread today and, according to Urdang (2010), it has abandoned both its basic psychodynamic orientation, as well as its emphasis on professional self-construction and on process-oriented work. Instead, training focuses on cognitive-behavioral theories oriented toward finding solutions, and on time-limited and evidence-based treatments that are results-oriented. These approaches tend to reinforce socio-educational workers' tendencies toward “omniscience, benevolence, and omnipotence” (Brightman, 1984–1985). Thus, larger questions related to meaning, inner life, and group dynamics are often overlooked (Applegate, 2004).

Reflexive processes are considered a crucial strategy for socio-educational workers dealing with uncertain, complex, ambiguous, and unpredictable situations (Spafford et al., 2007; Afrouz, 2021). Reflexive processes are also helpful in managing the financial insecurity of the profession (Werzelen et al., 2019). However, a certain amount of uncertainty, in contrast to the centrality of bureaucratic organizations, is equally crucial to this field (Finlay and Gough, 2003; Striano et al., 2018). In this profession, emotions, thoughts, and actions are intrinsically connected. During professional activity, it is often a “defended self”: defenses can be exceptionally heightened by difficult situations (Bower, 2005; Trevithick, 2011). For this reason, it is important to cultivate reflection after professional activity: such reflection entails a dynamic process of self-awareness that takes into account emotions as well as both external and internal reality.

Although it is not easy to prove the link between reflection, educators' well-being, and the efficacy of interventions to promote team reflexivity, multiple studies have suggested that reflexive practices improve relationships with others and with one's professional practice. It thus protects from the risk of burnout, especially in unpredictable and complex environments (Widmer et al., 2009; Morgan et al., 2013; Matyushkina and Kntemirova, 2019).

Moreover, there are multiple studies on team reflexivity and its positive effects on performance, innovation, and efficacy (De Dreu, 2002; Schippers et al., 2015; Konradt et al., 2016).

The link between reflexivity and specific characteristics of any given team (such as trust, psychological safety, a shared vision, and the diversification of its professional members) has been shown to have a direct, positive effect on the performance of the team (Hinsz et al., 1997). Diverse teams possess a great variety of knowledge, competences, and skills; they also must integrate differing opinions and perspectives on the task at hand. According to van Knippenberg et al. (2004), this process generates more creative and innovative ideas.

The reflexive team is thus an important organizational tool for protecting workers' well-being. Studies have shown that team reflexivity positively affects job engagement (as measured by efficacy, energy, and level of involvement), compassion satisfaction (defined as the pleasure derived from being able to do one's work well while also helping others), and resilience (the ability to respond positively to challenging experiences) (Sanchez-Reilly et al., 2013; Lines et al., 2021).

The Non-profit Organization “Maestri di Strada”

The non-profit organization Maestri di Strada (MdS, or “Street Teachers”) carries out complex socio-educational interventions, both inside and outside of schools, in order to prevent dropout rates and promote the social inclusion of young people.

Maestri di Strada began in Naples, Italy in 2003 with the “Chance Project,” which offered a second-chance school to young people who had previously dropped out. Since 2010, MdS has launched many new socio-educational projects in partnership with the University of Naples Federico II.

These projects serve the eastern suburbs of Naples: specifically, the San Giovanni, Barra, and Ponticelli neighborhoods. This area has 140,000 inhabitants and covers an area of 20 km2. The environment is characterized by high levels of social inequities, poverty, and high rates of early school leaving. Here, criminal organizations recruit many young people who lack both qualifications and employment, and are vulnerable to promises of “quick profits.” Young children below the age of criminal responsibility are often recruited, and the number of young victims of murder is remarkably high. Many of those young people internalize the experience of social exclusion, which transforms into feelings of shame, anger, and a widespread sense of “learned” powerlessness (De Rosa et al., 2017; Parrello, 2018).

Maestri di Strada's interventions follow a theoretical framework which is grounded in cultural psychology and psychoanalysis. Accordingly, all forms of learning and all relationships, whether between clients and workers, or between colleagues, are situated semiotically and characterized emotionally depending on both conscious and subconscious dynamics (Salvatore and Zittoun, 2011).

Maestri di Strada's projects are configured as action research (AR), and often as participatory action research (PAR) (Moreno, 2009; Parrello et al., 2019a).

Action research, as it is known, is a model of investigation whose main aim is to improve the future skills and activities of the researcher, rather than to produce theoretical knowledge. In the 1950s, AR also spread to the field of education (Kaneklin et al., 2010; Baldacci, 2012), and today it is considered one of the most important strategies for qualitative research in education (Coggi and Ricchiardi, 2005), as well as for community care (Lipari and Scaratti, 2014).

At the end of the 1960s, an international network of researchers originated participatory action research (PAR) in order to tackle various problems facing marginalized members of society. Participatory action research deals with power imbalances that generate social and individual distress (Arcidiacono et al., 2017; Stapleton, 2018). For this reason, the PAR method is thought to be particularly suited to the educational field, where power dynamics are a constant presence (Jacobs, 2016). In PAR, knowledge is created by the people involved in the research process, in a non-hierarchical, democratic environment (Savin-Baden and Wimpenny, 2007) that produces contextual knowledge (Pine, 2009).

Reflection is part of the PAR cycle, which can be described as a metacognitive process that consists of exploring personal beliefs, thoughts, and actions in a deliberate, autobiographical, and critical way (Marcosa et al., 2009).

At MdS, both AR and PAR projects aim to identify initiatives that can re-motivate young people to engage with school and to develop active citizenship practices. Young people are assisted individually or in groups by a tutor who is either an adult or a peer a few years older than them. Participants sign up for educational and/or creative workshops, and become actively involved in community events. Moreover, MdS has also developed wider social interventions aimed at supporting families, teachers, and entire communities.

Currently, the MdS team—which seeks to develop multi-disciplinary synergy—is composed of 45 members: educators, teachers, social workers, artists, community parents, psychologists, sociologists, and educational theorists.

Maestri di Strada can be defined as a “community of practices” (Wenger, 1998) because its members are united by a common mission, reciprocal commitment, and a shared narrative repertoire. It is also a “reflective community” (Schön, 1983) because the team's reflexivity is at the center of its methodology (Leitch and Day, 2020). The main reflexive tool used by MdS is the Multi-Vision group (MG) (Parrello et al., 2020).

The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on the basis of its global diffusion. Italy was the first European country to be seriously affected by the virus, and the government promptly implemented very restrictive measures aimed at the entire population. A lockdown was enacted involving all collective economic, cultural, and educational activities, which were substituted, whenever possible, by distance working and learning. All persons were forbidden from leaving home, except in cases of utmost urgency. Such a drastic and sudden form of social distancing and isolation is unprecedented in history.

The spread of the virus, its daily death toll, and social distancing undermined senses of stability, safety, and identity, as well as physical and psychological continuity, for both individuals and communities (van der Kolk, 2014). Thus, the traumatic impact of the pandemic immediately became clear: many experienced immobility, loneliness, uncertainty, a distorted sense of time, the loss of predictability in the world, and a loss of life's meaning.

Various psychological consequences of the pandemic have already been observed: all over the world, mental health services have registered a generalized spread of sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Cellini et al., 2020; Galea et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2020). The mental health of children, teens, and young people is at risk as well: they have been deprived of extra-familial social relationships (Dubey et al., 2020; Ghosh et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2020; Parola et al., 2020; Petretto et al., 2020; Rogora and Bizzarri, 2020); they have endured their parents' altered mental states and the increase of intra-familial conflicts (Sommantico, 2010; Fionda, 2020; Usher et al., 2020); and they have been constantly exposed to a terrorizing media narrative, centered around death and disease (Garfin et al., 2020). In addition to psychological consequences, socioeconomic effects must be taken into account as well. Lockdown has often led to unemployment and a rise in poverty rates. One-third of all students in the world (about 8 million in Italy) did not have access to technological devices, a stable Internet connection, and/or adequate home spaces for distance learning. This divide has exacerbated inequalities, the risk of school dropout, and social exclusion: according to UNICEF (2020), this is a “global education emergency,” the impact of which could be felt for decades to come.

Past studies of other severe, unplanned disruptions to schooling and family have shown that the greatest negative impact on long-term educational and emotional outcomes tends to be observed on the most disadvantaged children. Consequently, there are considerable concerns that the acknowledged attainment gap for children and young people from disadvantaged families could be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (O'Connor et al., 2020).

Given this background, teachers and educators have been exposed to high stress levels, especially those who work in marginalized settings. With the closing of schools and local centers for socio-educational activities, teachers have been forced to abruptly interrupt their relationships with colleagues, students, and families, and to adapt quickly to distance learning—often without adequate training. The demands of the Ministry of Education and of school principals were pressing and at times contradictory. Working hours increased. For these reasons and various others (Parrello et al., 2019b), many researchers have predicted a higher risk of burnout for teachers during the pandemic (Alves et al., 2020; Kim and Asbury, 2020; Sokal et al., 2020; Trust et al., 2020; UNESCO, 2020). The professional difficulties faced by third-sector educators have been similar to those of teachers, with the addition of greater financial insecurity due to their roles' structural precariousness in Italy (De Lauso and De Capite, 2020).

It is clear that the pandemic and social distancing have affected workers' mental well-being, and their performance as teams, both in local schools and with the MdS Association. So how can the well-being of individuals be protected, and how can teams develop resilience in order to face the impact of COVID-19?

Due to health regulations, the MG—the teams' main tool of “thought resistance” —could not be organized in person, in this very moment of utmost uncertainty and anxiety. However, MdS's workers needed to stand together and think together in order to confront the enormous struggles facing local pupils and families, and to recognize their own vulnerabilities (O'Connor et al., 2020; O'Leary and Tsui, 2020; Cabiati and Gómez-Ciriano, 2021).

Thus, aware of the importance of MGs, the MdS workers decided to try to carry them out remotely—a rapidly expanding practice (Barak, 1999; Barnett, 2014; Handke et al., 2019)—in compliance with health regulations.

The Aim of the Present Study

Through qualitative research with a longitudinal approach, this study aims to evaluate the MG's efficacy in supporting teams' reflexive thinking, despite its new online format during a traumatic event such as the pandemic.

In particular, through a comparison of MG discourse both before and during the COVID-19 lockdown, the study investigates the factors that threaten and protect individual and team well-being, and consequently impact professional performance. The goal was also to evaluate how the pandemic “entered” group discourse, and to investigate if, even in its online format, the MG instrument succeeded in offering an adequate space for confronting such an unsettling and unexpected event, and whether it was able to support resistance, resilience, and creativity.

Methods

The multivision group (MG) is a modified balint group (Van Roy et al., 2015). In the 1950s, the Balint Group (BG) was conceptualized in order to support the work of doctors. During treatment, doctors can be viewed as the most powerful medicine: as such, after treatment, observation of themselves, the patient, and the doctor-patient relationship is required within the context of a larger group setting (Balint, 1957; Perini, 2013). The BG is considered a learning environment as well as a mediating experience, the goal of which is to improve the following: sensitivity to clients' needs, professional performance, and work satisfaction. Within a BG, a participant presents a case and other members respond with comments, emotional reactions, and hypotheses for alternative practices. The BG is focused less on group dynamics and more collective discussion.

Maestri di Strada's MG is composed of a team of professionals from the organization. They meet on a weekly basis under the guidance of a facilitator, who is also an experienced psychotherapist. Instead of presenting specific cases, participants freely describe whatever work experiences they feel the need to share in that moment, in order to better understand them. The facilitator helps the group to think creatively and to enrich their repertoire of options for handling difficult situations. The goal is to turn individuals' professional problems into shared, collective problems. The atmosphere is focused on listening, on acknowledging emotions as viable pathways to deeper understanding, and on open exchange. The atmosphere is usually open and validating, which allows for more distressing topics to arise as well.

In some ways the MG may resemble the Focus Group (FG): the (FG) is also structured around the way in which participants relate their everyday experience (Manuti et al., 2017). However, in the FG, participants do not belong to the same community of practices. Above all, the discussion follows a (more or less) organized track, and is led by a facilitator depending on the level of organized direction desired (Acocella, 2005). In the FG, although the facilitator strives to maintain a calm environment, participants may at times feel strained due to the potential the lack of privacy, and a consequent attempt to avoid difficult topics (Sim and Waterfeld, 2019). Along these same lines, the T-Group (TG) can also at times have damaging effects on its participants, if they do not know one other and are subjected to frequent provocations and to stressful situations (Highhouse, 2002).

All meetings of the MG carried out by MdS took place in the presence of a silent observer (De Rosa, 2003), who then produced a narrative report. Observers are usually trained interns, who come from Social Sciences, Education Science, or Psychology degree programs. They receive brief initial training on observational method from the organization's psychologists. The preferred method is psychoanalytically oriented. While there are no prearranged grids, each person lets their attention drift and focus according to the discourse and dynamics of the group. The narrative report is read aloud during the subsequent meeting. The group then “validates” the report and uses it as a record of its own past history. On the one hand, observers are record-keepers in charge of passively cataloging the universe of meanings present for the group; on the other, however, observers actively contribute to constructing the group archive through their subjective interpretation. Only later on do all group reports become textual material for research.

During the school year 2019–2020, MdS's team met every week for MG meetings at the organization headquarters. Since March 2020, when a health emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in Italy and meetings in person were restricted, MdS has carried out weekly online MGs through a communication platform (Microsoft Teams). The platform allows participants to listen to speakers and to break in at any time. Only those who speak will automatically appear on screen, with a maximum of nine people at a time. While listening, it is possible to participate in written form through a live chat, which also allows participants to send emojis, images, links, etc. In short, group communication employs three channels: oral, visual (face to face but limited to whoever is speaking in that moment), and written. The facilitator establishes the rules forturn-taking.

Both in person and online meetings were led by an experienced psychotherapist. A silent observer also participated in the meeting, who later produced accurate narrative reports.

This article takes into consideration the MG reports during two different time periods: pre-pandemic (T1) and early pandemic (T2). As a basis of comparison, the school year preceding the pandemic was also taken into consideration. During T1 (September 2018–June 2019), the MdS team met 18 times in person; during T2 (March–June 2020) the team met 12 times through an online platform.

The T1 corpus, composed of 18 reports written by two observers (31.842 occurrences, 5.725 distinct forms, 3.906 lemmas), and the T2 corpus, composed of 12 reports written by two observers (41.173 occurrences, 6.073 distinct forms, 4.094 lemmas), were analyzed by T-Lab Plus software (2020).

T-Lab Plus is an all-in-one set of linguistic, statistical, and graphical tools for text analysis (Lancia, 2004).

Each corpus went through a stemming process (Automatic Lemmatization). A Thematic Analysis of Elementary Contexts was performed. This type of quali-quantitative analysis is suitable for exploring the content of rich narrative and discursive corpora. The starting theoretical hypothesis is that language is, on the one hand, a tool for communicating, to which the principle of relevance and pertinence (e.g., I dwell on a theme because I consider it important) applies. On the other hand, it is also a tool for non-neutral classification, which is indispensable for organizing the world. In the apparent chaos of a conversation (such as the ones taking place during the MG) it is therefore possible to find significant recursions, which are constructed collectively by the group and allow us to penetrate the text in-depth, in order to formulate explicative hypotheses and “local rules” (Smorti, 2003; Giani et al., 2009).

The text was partitioned into elementary context units, with each approximately the length of a sentence. The units were then classified according to the distributions of words in terms of co-occurrences. Cluster analysis was carried out by an unsupervised ascendant hierarchical method (Bisecting K-Means Algorithm). The co-occurrence of semantic features characterizes this analysis. Each cluster consists of a set of keywords (vocabulary) that appear in specific selections of elementary context units, and which were ranked according to the decreasing value of chi-square. A label was then assigned to each cluster by researchers, who first thoroughly read the observation reports that comprise the corpora. This step is fundamental to guaranteeing an interpretive process that limits misunderstandings or simplifications.

Results of the analysis can be considered an isotopic (iso = same; topoi = places) map of the clusters, as they were composed of the co-occurrences of semantic traits. This map can be understood as a picture of the “mind rooms” (or points of view) (Reinert, 1998) in which the MG occurred, and which was subsequently presented to the MdS team in the form of the narrative report.

Results

T1—Pre-pandemic Corpus

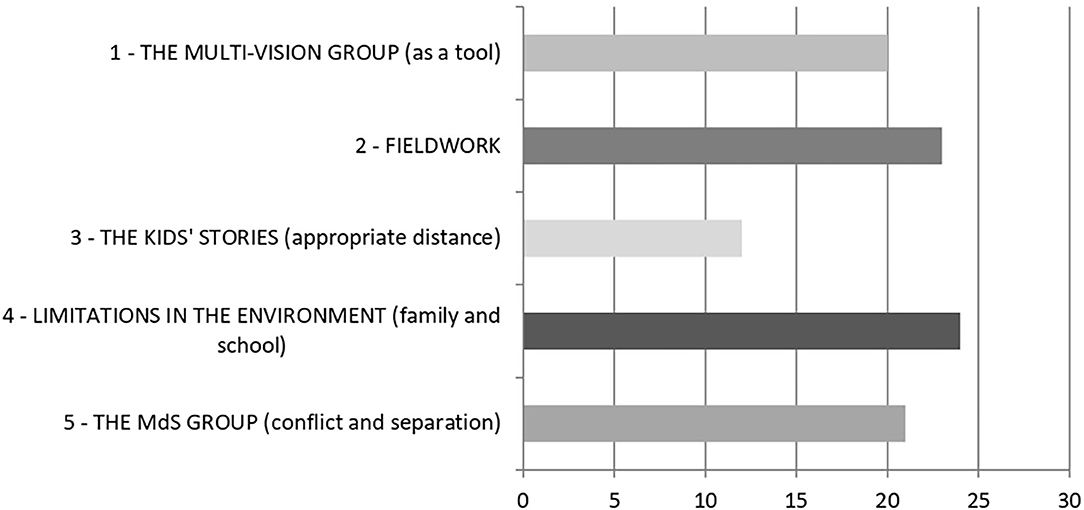

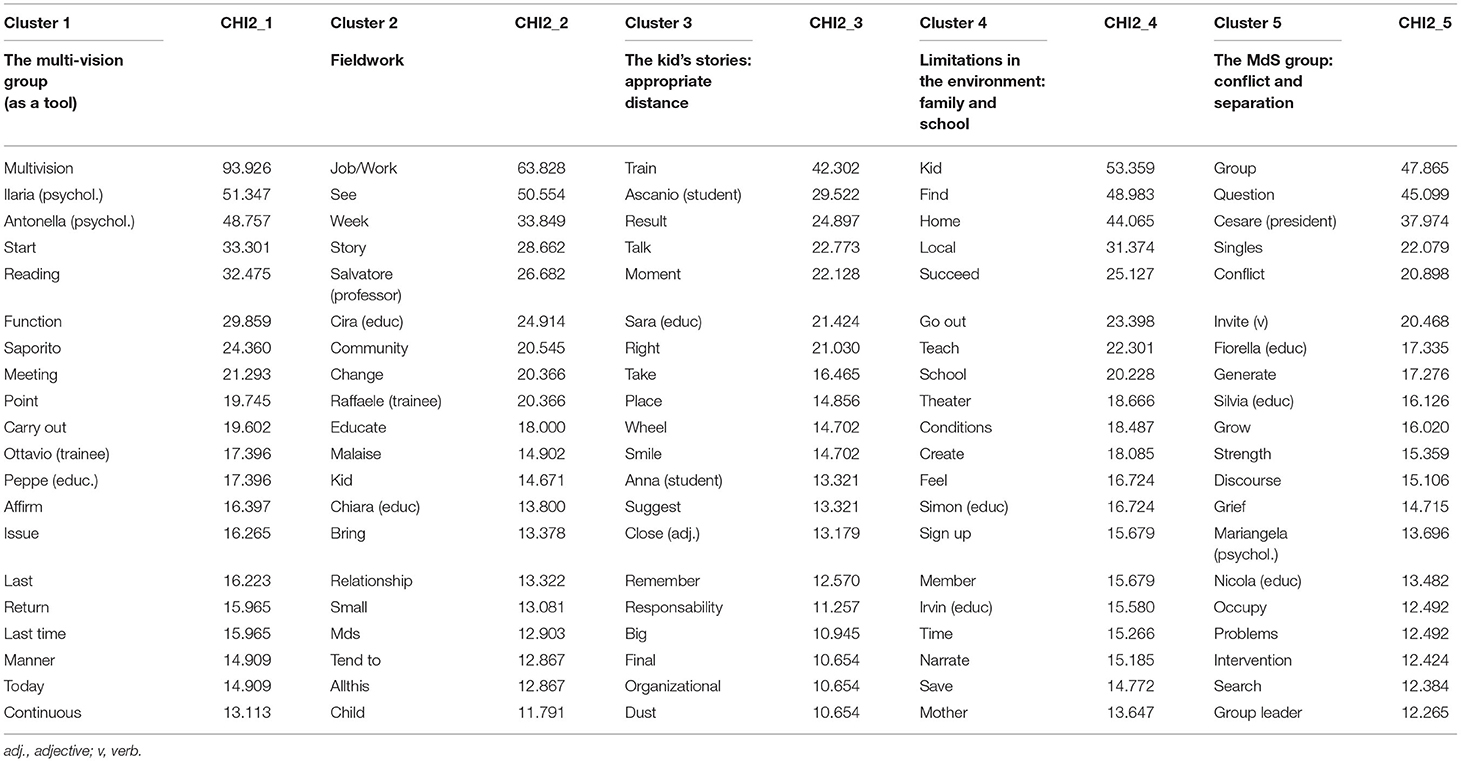

The analysis classified 760 elementary context units (ECUs) and partitioned them into five clusters, or macro-themes. Figure 1 shows the clusters' quantitative dimensions. Table 1 displays the specific vocabularies compiled by T-Lab Plus in accordance with the chi-square value.

Cluster T1.1—The Multi-Vision Group (20% ECUs)

This cluster's vocabulary contains the team's discourse regarding the MG as a tool (multi-vision, observation, reading, begin, meeting) and the function of sharing and care that it performs for the group.

Selection of ECUs:

1. After the reading of the report, A. (psychologist) notes that during that day's multi-vision, its function as a demonstration of care of the group was apparent.

2. (psychologist) recalls that the last multi-vision was especially painful and challenging, but members are all present despite the difficulties, “'til desire do us part.”

3. Each member of the group holds a small part of the anguish: this also is the function of multi-vision.

4. She recalls the anger that emerged from the last meeting and says that now we need to face it together.

Cluster T1.2—Fieldwork (23% ECUs)

In this large cluster, the team reaffirmed the need to pause and step back to see both beauty and mistakes in their work, and to reflect on the difficulties of field work, relationships between colleagues, and painful encounters with some kids. In particular, the team talked about an event organized by the MdS organization, called Educational Community Week. They retraced the story of the project and the organization of this event, in order to focus on everything that did or did not work. They complained about various decisions that were not unanimous. They acknowledged the malaise felt by some educators. They questioned themselves regarding what to change in the future for the organization of similar events.

Selection of ECUs:

1. Our job is dense, full of components that require total immersion. Even when you clock out, you never really get away. But if you don't distance yourself, you can't see beauty.

2. What can an educator do in the face of such great pain in a kid?

3. C. (MdS' president) highlights an upside of the Educational Community Week: the kids participated in an event that brought them all together.

4. Some MdS workers experienced the Educational Community Week as an imposition, an event that was decided by a few. Trouble exploded in the square [where it was held] and did not give them the chance to enjoy the moment.

Cluster T1.3—The Kids' Stories: Appropriate Distance (12% ECUs)

In this small cluster's vocabulary, the kids' names appear the most frequently (e.g., Ascanio, Anna)1. Beginning with these stories of marginalization and pain, educators then reflected on their own responsibility as adults and professionals, regarding the right amount of distance, and how hard it is to obtain certain results. They asked themselves when the right moment is to talk, suggest, or be close, but also imagined being able to take a train to physically escape this reality, like one of the kids, at least temporarily.

Selection of ECUs:

1. M. (community parent) is worried about Ascanio, who recently came out: a fragile kid who feels guilty, isolates himself often and talks of committing suicide. C. (artist) met him on a train while he was aimlessly on the run.

2. Anna failed and will be held back a year. The problem is not failing per se, but the way it was communicated by the teacher, who was laughing: it was mortifying for her and for us.

3. M. (educator) says that we should maintain the right amount of detachment. The GM leader asks: detachment or distance?

4. In this field, people also need to be responsible for stopping when they no longer have the right amount of resources or energy to continue, and take care of themselves.

Cluster T1.4—Limitations in the Environment: Family and School (24% ECUs)

The fourth cluster is very rich: its vocabulary contains references to the shortcomings of family (home, mother) and school (teacher, school), which were often described in anger, and alongside the desire to create the conditions necessary to succeed in saving every kid. In particular, the workers talked about MdS's local art workshops (theater, for example), which were considered to be a valuable resource. However, they also addressed the limits to their own fantasies of omnipotence.

Selection of ECUs:

1. When our kids leave and go home, they only find hate; they can't see anything else.

2. How can it be that a deaf-mute 15-year-old kid couldn't find anyone at school until now who would teach him to communicate, to live in a society, to have a future?

3. If I'm at school every morning, I have no time to be with them in theater; I can't be everywhere, but my heart breaks: tonight, I dreamed of a wall falling on me…

4. If we tell the kids “you'll always find me,” if we think we can “save” them, making up for all the shortcomings of their home and school environments, we then take on a task in which we will inevitably falter.

Cluster T1.5—The MdS Group: Conflict and Separation (21% ECUs)

In the last cluster, the team dealt with topics concerning internal MdS group dynamics. They discussed the feeling of grief for the painful exit of an educator (Fiorella) from the team, the problems regarding democratic processes in the organization, and the conflicts between colleagues and the organization's president (Cesare). Here, the Group Leader intervened more. They wondered about the well-being of single members and about how they could keep growing as a group.

Selection of ECUs:

1. F. (educator) is a symbol for something that all of us are feeling: the fear of failure.

2. S. (educational theorist) says that the group can only work if it is capable of not sweeping the dirt under the rug, and of confronting its own limitations, conflicts, and grief.

3. We took on a workload that we can only bear with the help of the group: under the weight of the kids' pain, we either completely drown, or we grow.

4. C. (MdS' president) encourages us to free ourselves from any sense of dependence on the boss.

T2—Early Pandemic Corpus

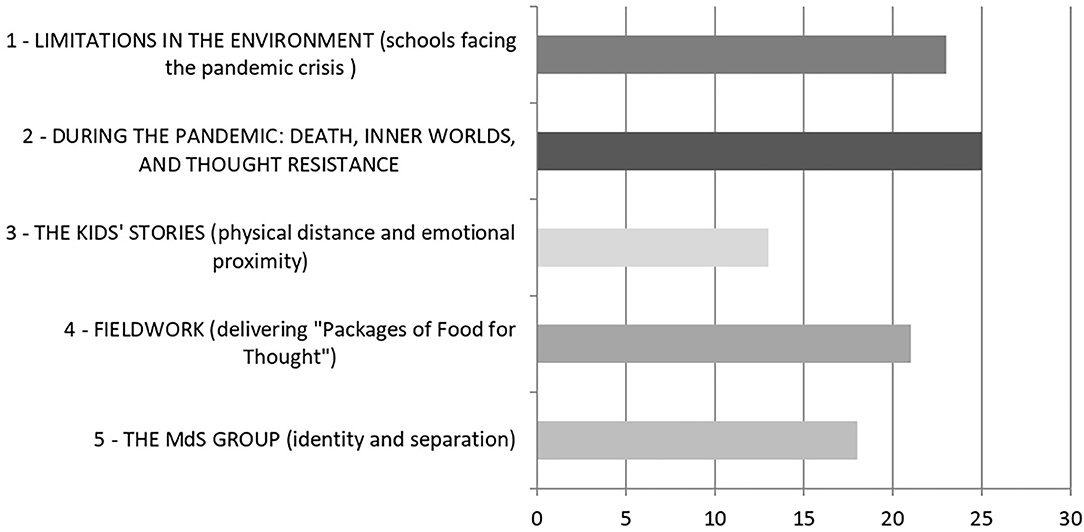

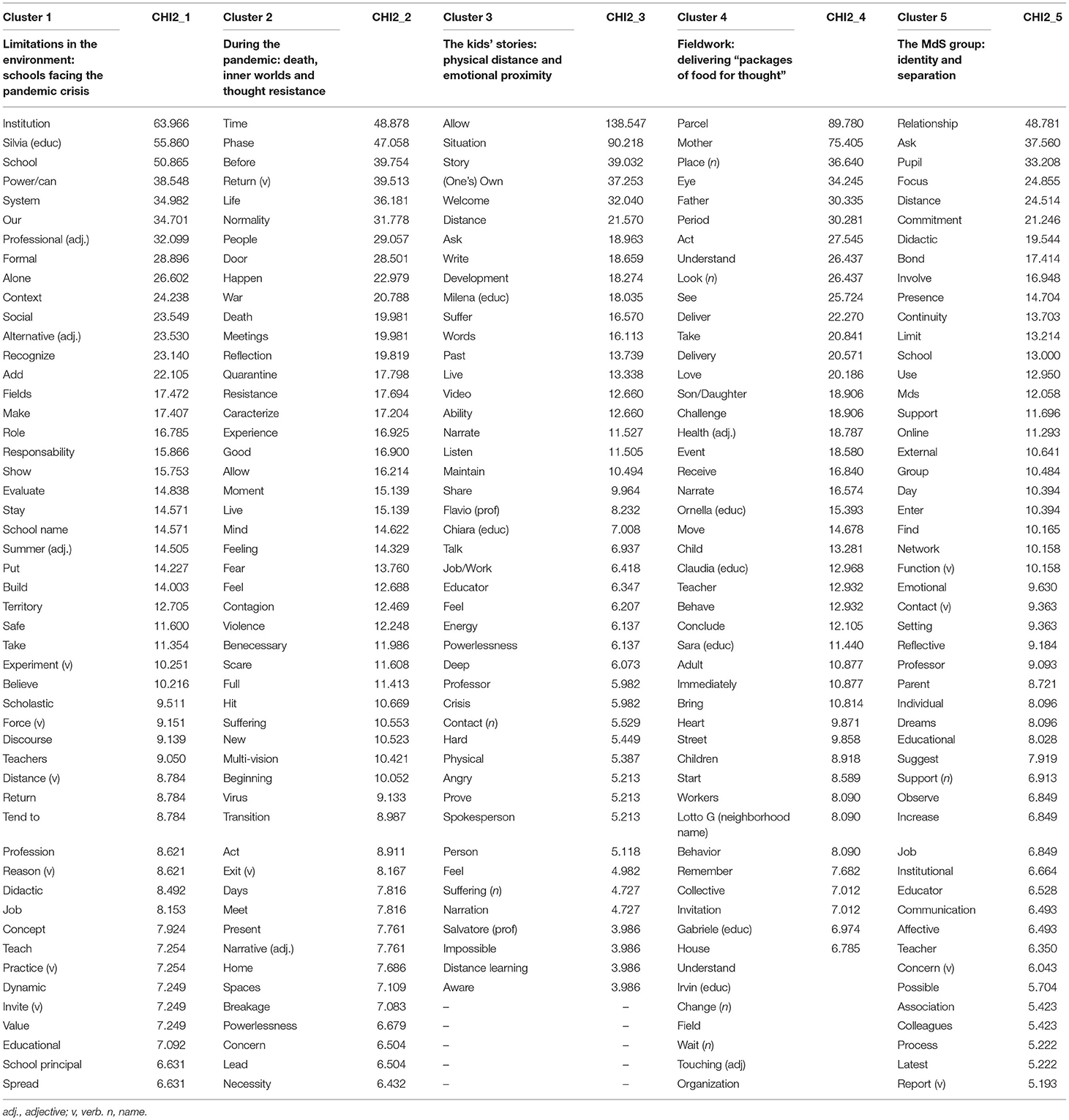

The analysis classified 863 elementary context units (ECUs) and separated them into five clusters, or macro-themes. Figure 2 shows the clusters' quantitative dimensions. Table 2 displays the specific vocabularies compiled by T-Lab Plus in accordance with the chi-square value.

Cluster T2.1—Limitations in the Environment: Schools Facing the Pandemic Crisis (23% ECUs)

This cluster's rich vocabulary contains the group's discourse regarding the functioning of the educational institution in a time of crisis brought about by the pandemic, and in the specific setting of the suburbs (discourse, institution, school, system, formal, context, social, territory). The discourse concerns the institution's power and responsibilities (power, responsibility). Teachers seem to be alone while facing hardship, stressed by various obligations (teachers, alone, order (v), practice, work/job, didactic, school principal): it is harder for them to think things through and experiment (reason, experiment) without reflexive tools or group structure. The group wondered how MdS can support an alternative approach to school administration (can, alternative).

Selection of ECUs:

1. Teachers don't have a group to welcome them in, or a group they can vent to, and they're alone within the institution.

2. The lack of trust in each other is a characteristic of the system.

3. Teachers weren't prepared for distance learning, nor for experimenting with new didactic methods, and now they're forced to by the school system.

4. Right now, we need to be understanding of teachers, in order to understand the narrative imposed by the school system, but, at the same time, we have to create new discourses and alternative educational approaches that will be able to support schools now as well as later on.

Cluster T2.2—During the Pandemic: Death, Inner Worlds, and Thought Resistance (25% ECUs)

This cluster's vocabulary, the largest of the five, contains the group's discourse regarding tragic external events, and their inner reverberations: time, phase, before, return, normality, quarantine, break, virus, life, death, experience, violence, fear, powerlessness, concern, suffering, war. They talked about life and death (infection and death rates), about the loss of a sense of normality, and about their new sense of time (denser on the outside and slower on the inside, because of the difficulty of adapting to the rapid succession of events).

Many educators entrusted their inner feelings and strong emotions to the group, often through the use of metaphors and dreams. The main metaphors concerned war and disability, while dreams mostly expressed anguish and bewilderment, but also, on occasion, freedom. Many participants explicitly highlighted the beneficial function of the MG: meetings, reflection, resistance, multi-vision, mind. Others took notice of positive events occurring at the time: happen, moment, good.

Selection of ECUs:

1. The subject of time returns: the alteration of time that we have experienced… over the past months, we were forced to change and approach time differently.

2. There is a parallel between this moment in our lives and the experience of war: apprehension, loneliness, constant fear, and an inability to take control of our own experience.

3. Quarantine feels like time has frozen. The illusion of going back to things as they were before is insane. But good things do happen, and are happening.

4. We're lucky because we have the stability of the ongoing presence of the group. This is a group that's already established, and capable of emotional sensitivity. We have this group-mother that welcomes us and all of our experiences and emotions.

5. We at MdS have built a social safety net: that is, the group. The group gives us a space for processing, where we can share and think in new ways. So we then find the courage to act responsibly, no matter the difficulties.

Cluster T2.3—Kids' Stories: Physical Distance and Emotional Proximity (13% ECUs)

This cluster's vocabulary contains discourse regarding the technology that allows people to stay connected despite physical distance (allow, situation video, distance, story, welcome, contact, share). However, this type of connection can only develop into emotional closeness and authentic communication if there is also a sense of continuity with a preexisting, positive relationship established by the educator or teacher (past, maintain, work, educator, teacher). In that vein, the group recounted stories of violence, powerlessness, and suffering, as told to them remotely by the kids (spokesperson, story, narration, powerlessness, suffer, suffering). Some educators thought that the “comfortable distance” itself allowed people to recount those painful experiences.

Selection of ECUs:

1. N. (artist) says that today we can lean on this group for support because positive relationships have already been established before. And he sees the same thing with his students: he can carry out impactful creative workshops from a distance because they have shared good experiences together in the past. The confidence they find today is rooted in yesterday's positive experience. The kids don't lose the intimacy previously found in the relationship because of the distance; they are comfortable when it comes to continuing to narrate their own stories and lives, and through these stories we can stay in touch with what is going on for them. It's a sort of virtuous circle that supports our educational work.

2. What if it was this very distance that allowed the girl to tell her story, to put into words so much violence and suffering?

3. This time period makes it very hard to “do,” but it provides an opportunity to listen and think deeply.

Cluster T2.4—Fieldwork: Delivering “Packages of Food for Thought” (21% ECUs)

This cluster's rich vocabulary concerns an initiative set up by MdS during lockdown. After initial inactivity due to strict health regulations, MdS introduced the delivery of “packages of food for thought” to kids who belong to vulnerable families (package, organization, conclude, deliver, delivery, event, health). The packages contained tablets, books, stationery, and, above all, personal letters. The deliveries took place thanks to the support of the Ministry of Education and law enforcement, and kids and parents saw them as an act of love (mother, father, son, child, act, love, eye, look, see, touching). The group discussed the emotional impact of this project at length. Very few teachers wanted to participate (teacher). Some of the places they visited were on the outskirts of the suburbs, which are striking in their poverty and neglect (place, street, house).

According to the educators, the packages—delivered during a time of collective hopelessness and passivity—kindled a sense of empowerment in the recipients.

Selection of ECUs:

1. Delivering a package seems like a trivial thing, but it can actually symbolize an act of overcoming certain predetermined limits.

2. The infrequency of acts of care was apparent from looking into the eyes of the families. However, the moment they understood who we were, they introduced themselves with a smile and took the package and, with it, accepted the gesture of love. Like that father…

3. The positive thing about delivering packages is the effect they created, and the feeling of consideration. People were asking to be seen, and they needed attention.

4. They were waiting for us; rumors moved faster than our van. When we arrived in a new location, they were already prepared: initially a little shy and bashful, then curious and eager to receive a package, which was viewed as a sign that the organization thought of them, sees them, and doesn't abandon them alone in those forgotten, anonymous places.

5. Some, curious, got closer and offered their help in navigating the neglected neighborhood places.

6. The teachers behaved in an ambivalent manner, as if they were torn between seeing the kids and protecting themselves.

7. We had the courage and the ability to move in order to reach them. And this was perceived by families as an invitation to act, to participate, to exist, and to be seen by welcoming eyes that sought their gaze and offered them care.

Cluster T2.5—The MdS Group: Identity and Separation (18% ECUs)

This cluster's vocabulary records the group's discourse regarding the specific organization of MdS, especially during this time of crisis: their main goal is to cultivate relationships with pupils and parents despite remote learning. They also seek to allow themselves to be “used” by the school and its teachers to serve the students (relationships, bond, ask, pupil, focus, teachers, parents), and they continue to dream of a better future for everyone. Again, we find their awareness of having a powerful reflexive tool at their disposal, even when it is only available online (group, setting, reflexive, support, online, function). Its absence is regarded as a great limitation for schools (limit, school, involve). Selection of ECUs:

1. MdS interposes itself between teachers, pupils, and parents in order to mediate.

2. O. (educator) says that she consciously let the school use her to help the pupils.

3. One mother, worried about her daughter who struggled with distance learning, contacts MdS. O. (educator) gets to work to try and improve communication with teachers.

4. Our duty now is to try and protect relationships.

5. Parents and children feel abandoned by the school, and they seek us out, knowing that we are distinct from the school.

6. Teachers use our educators and psychologists in order to vent. They use MdS as a container for their suffering: indeed, thanks to the group, we have learned to contain and withstand the challenges.

7. Without a reflexive setting or a welcoming community, teachers are scuba divers without oxygen. In the face of this absence, MdS can be a resource: we can be their oxygen!

8. The fact that G. (educator) left the MdS team deeply impacted the group. Many wonder if, sooner or later, they too will be forced to leave this job—full of dreams but with no financial security.

Discussion

In July 2020, after 4 months of the pandemic, global research groups began to prioritize education and the need for changes in work environments (O'Connor et al., 2020). The experience of the MdS team is a confirmation of this need.

In the suburbs of Naples, many children and teens live in a state of deprivation and social exclusion: the COVID-19 lockdown increased their risk for school dropout and other challenges2 In the same time period, educators' personal and professional well-being was also severely put to the test. The MdS organization attempted to “take care of those who care,” following the suggestions of van der Kolk (2020): by establishing routines, creating thoughtful connection, and fostering the feeling of being alive. The online MG also moved in that direction: it became a regular and eagerly anticipated meeting for members. It allowed participants locked inside their homes to see one other, to communicate, and to re-imagine creative approaches to pedagogy together. The thematic areas that emerged from our analysis of the group's discourses indicate that this reflexive tool was effective: the pandemic took over the group's discussions, and many felt the need to talk about themselves even before they discussed their work, addressing their own vulnerability even before turning to the vulnerability of the kids and their families (Cabiati and Gómez-Ciriano, 2021). In socio-educational work, personal self and professional self are indeed tightly connected (Fellenz, 2016).

Throughout the year prior, during MG meetings, the group had reflected in particular on limitations in the environment, both of families and schools (cluster T1.4, the largest). They also discussed fieldwork (cluster T1.2). They wondered how educators can place themselves at a “right distance” from the kids, especially when their stories are particularly painful and moving (cluster T1.3). The group had also discussed its own internal dynamics, including conflicts between colleagues and with their leader, while reflecting on the fact that one educator had left the team, perhaps because of the difficult emotional sustainability of the job (cluster T1.5). They often mentioned the positive sharing and support provided by the MG tool (cluster T1.1).

Analysis of MG discourse during lockdown revealed four interesting elements. Firstly, the MG allowed participants to face the shock of the pandemic. They made contact with their own and with their colleagues' inner worlds (cluster T2.2, the largest), by expressing emotions and feelings. They also drew from symbolic thinking through the use of metaphors and the recounting of dreams. Thanks to the online MG, educators constructed a shared narrative of the pandemic that differed from the apocalyptic narrative spread by mass media (Rossolatos, 2020), thereby connecting emotions, thoughts, and action, and protecting their own sense of safety, identity, and continuity. The use of metaphors and the critical discussion that ensued (Craig, 2020; Sabucedo et al., 2020), as well as the recounting of personal dreams filled with anguish as well as hope (Iorio et al., 2020), are all signs of an attempt to make sense of the pandemic. Only by taking care of themselves can educators offer protection and support to those they take care of (Myers et al., 2020).

Secondly, the MG group allowed the team to analyze shortcomings in their own professional settings, focusing on the administration of educational institutions facing the pandemic crisis, in order to come up with ways to support the teachers' work (cluster T2.1). The painful stories of the kids “got to them” despite the physical distance, thanks to the relationships that had been consolidated over time (cluster T2.3): a new form of “right distance” was thus experienced through a virtual filter.

Thirdly, a new type of fieldwork emerged: the MdS team promptly came up with creative initiatives, like the delivery of “packages of food for thought” (cluster T2.4), which were useful (and not only materially) to hundreds of struggling students and families.

Finally, the group did not cease reflecting on its own internal dynamics: however, in this phase conflicts seemed to temporarily disappear, perhaps because of a need for internal unity in the face of the collective threat of the virus. Team members then reflected on their professional identity, and on their strengths and weaknesses in supporting school-family relationships and the dream of a fairer society. They were very upset by the fact that an educator left the group because of the profession's financial insecurity (cluster T2.5). During this phase, no comments were made by the team concerning the MG's online format. Reflexive methodology—at first in person, and then online during lockdown—most likely contributed to the resilient and resistant qualities of the MdS community. It was capable of absorbing the shock of a stressful event and undertaking a speedy recovery process. Because of this, perhaps, any tendencies toward depression and self-idealizing hyperactivity were also curbed (Kulig, 2000).

In conclusion, even in the online format it took during the pandemic, team reflexivity helped to achieve many different positive outcomes. It allowed team members to take care of themselves and tend to their own vulnerability (Cabiati and Gómez-Ciriano, 2021), and it had positive effects on performance, innovation, and efficacy (De Dreu, 2002; Fook, 2013a,b; Schippers et al., 2013, 2015). The “packages of food for thought” were the first initiative of Project REM (Educational Resistance in Movement). This Project included, among other programs, online educational art workshops for students, online support groups for parents, online seminars for teachers, and Facebook live streams for all. Each initiative was both informative and entertaining (Parrello and Moreno, 2021). At the end of the school year, all at-risk students who had been served by MdS passed their exams. Cooperation with families increased, and new partnerships with schools were born.

According to O'Leary and Tsui (2020), the pandemic is an invaluable occasion for reflecting, analyzing, and learning from crisis. One can take the time to understand what has been working well and what has not, and identify new ways of working and adapting that can help to further develop the profession. The pandemic and its effects will be felt for many years to come, but it is already clear that socio-educational work is “fundamental to not only rebuilding but transforming our world” (Truell, 2020, p. 548).

The MdS team went back to in-person meetings as soon as it became possible, in early July 2020, with the accompanying awareness that bodies, non-verbal communication, and physical proximity are also fundamental to a group.

Limits and Future Perspectives

A limitation of this study is that it refers to a single source of observation. In fact, observers' reports are inevitably affected by their subjective experience as trainees They are also sometimes aspiring MdS members. Therefore, we should take into account the possibility of some “complacency” in their perspectives regarding the organization. Further research should integrate this study with questionnaires and interviews in order to also consider the point of view of individual participants regarding in-person, online, or blended MGs (Lodder et al., 2020). A research study integrating observational data and data from a self-report questionnaire evaluating the MG is already under way.

The hope of the authors of this article is that online and in-person reflexive groups may be used more widely by educators inside of schools and in the third sector (Kerkhoff, 2020). New studies should be conducted, offering critical opportunities for comparison.

At the moment, these results cannot be generalized, but the practical implications for workers' well-being appear to be evident.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by CERP (Comitato Etico delle Ricerca Psicologica), Department of Humanities, University of Naples Federico II. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed in the same way to conception and design of the study, manuscript composition, and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Chiara Cigliano for the English translation of the article.

Footnotes

1. ^Children's names were changed to respect their privacy.

2. ^In a single year of the pandemic, reports of school dropout in Naples have risen 65%. Most reports come from the San Giovanni, Barra, and Ponticelli neighborhoods: https://www.oggiscuola.com/web/2021/04/13/abbandono-scolastico-impennata-di-segnalazioni-cagliari-e-napoli-casi-drammatici/.

References

Acocella, I. (2005). L'uso dei focus groups nella ricerca sociale: vantaggi e svantaggi. Quad. Sociol. 37, 63–81. doi: 10.4000/qds.1077

Afrouz, R. (2021). Approaching uncertainty in social work education, a lesson from COVID-19 pandemic qualitative. Soc. Work 20, 561–567. doi: 10.1177/1473325020981078

Alves, R., Lopes, T., and Precioso, J. (2020). Teachers' well-being in times of COVID-19 pandemic: factors that explain professional well-being. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 15, 203–217. doi: 10.46661/ijeri.5129

Applegate, J. S. (2004). Full circle: returning psychoanalytic theory to social work education. Psychoanal. Soc. Work 11, 23–36. doi: 10.1300/J032v11n01_03

Arcidiacono, C., Natale, A., Carbone, A., and Procentese, F. (2017). Participatory action research from an intercultural and critical perspective. J. Prevent. Interv. Community 45, 44–56. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2016.1197740

Baldacci, M. (2012). Questioni di rigore nella ricerca-azione educativa, J. Educ. Cult. Psychol. Stud. 6, 97–106. doi: 10.7358/ecps-2012-006-bald

Barak, A. (1999). Psychological applications on the Internet: a discipline on the thresold of a new millennium. Appl. Prevent. Psychol. 8, 231–245. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80038-1

Barak, J., Gidron, A., and Turniansky, B. (2010). ‘Without stones there is no arch’: a study of professional development of teacher educators as a team. Profess. Dev. Educ. 36, 275–287. doi: 10.1080/19415250903457489

Barnett, J. E. (2014). Integrating Technology Into Practice: Essentials for Psychotherapists. Available online at: http://www.societyforpsychotherapy.org/integrating-technology-into-psychotherapy-practice (accessed March 15, 2018).

Barnett, R. (2009). Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 429–440. doi: 10.1080/03075070902771978

Brightman, B. K. (1984–1985). Narcissistic issues in the training experience of the psychotherapist. Int. J. Psychoanal. Psychother. 10, 293–317.

Cabiati, E., and Gómez-Ciriano, E. J. (2021). The dialogue between what we are living and what we are teaching and learning during COVID-19 pandemic: reflections of two social work educators from Italy and Spain. Qual. Soc. Work 20, 273–283. doi: 10.1177/1473325020973292

Cellini, N., Canale, N., Mioni, G., and Costa, S. (2020). Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digitalmedia use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 29:e13074. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074

Craig, D. (2020). Pandemic and its metaphors: sontag revisited in the COVID-19 era. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 23, 1025–1032. doi: 10.1177/1367549420938403

De Dreu, C. K. W. (2002). Team innovation and team effectiveness: the importance of minority dissent and reflexivity. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 11, 285–298. doi: 10.1080/13594320244000175

De Lauso, F., and De Capite, N. (2020). Gli Anticorpi della Solidarietà. Rapporto 2020 su Povertà ed Esclusione Sociale in Italia. Roma: Caritas Italiana.

De Rosa, B. (2003). “Aspetti metodologici dell'osservazione ad orientamento psicoanalitico,” in L'apprendista Osservatore, ed A. Nunziante Cesaro (Milano: Franco Angeli), 25–76.

De Rosa, B., Parrello, S., and Sommantico, M. (2017). Ranimer l'espoir: l'interventionpsycho-educative de Maestri di Strada. Connexion 107, 181–196. doi: 10.3917/cnx.107.0181

Dubey, S., Dubey, M. J., Ghosh, R., and Chatterje, S. (2020). Children of frontline COVID-19 warriors: our observations. J. Pediatr. 224, 188–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.026

Fellenz, M. R. (2016). Forming the professional self: bildung and the ontological perspective on professional education and development. Educ. Philos. Theory 48, 267–283. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1006161

Finlay, L., and Gough, B., (eds.). (2003). Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences. London: Blackwell.

Fionda, B. (2020). Emergenza nell'emergenza. Violenza di genere ai tempi del COVID-19. Psicobiettivo 2, 31–42. doi: 10.3280/PSOB2020-002003

Fook, J. (2013a). “Critical reflection in context: contemporary perspectives and issues,” in Critical Reflection in Context: Applications in Health and Social Care, eds J. Fook and F. Gardner (Abingdon, UK: Routledge), 1–11.

Fook, J. (2013b). “Uncertainty the defining characteristic of social work?,” in Social Work: A Reader, ed V. E. Cree (London: Routledge), 29–34.

Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., and Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing. The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 180, 817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C., and Holman, E. A. (2020). The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychol. 39, 355–357. doi: 10.1037/hea0000875

Ghosh, R., Dubey, M. J., Chatterjee, S., and Dubey, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on children: special focus on psychosocial aspect. Miner. Pediatr. 72, 226–235. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9

Giani, U., Osorio, G. M., and Parrello, S. (2009). “La narrazione della malattia come spazio per la ricerca del sé,” in Narrative Based Medicine e Complessità, ed U. Giani (Napoli: ScriptaWeb), 293–326.

González-Sanguino, C., Ausína, B., Castellanos, N. A., Saiz, J., López-Gómez, A., Ugidos, C., et al. (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040

Handke, L., Klonek, F. E., Parker, S. K., and Kauffeld, S. (2019). Interactive effects of team virtuality and work desing on team functioning. Small Group Res. 51, 3–47. doi: 10.1177/1046496419863490

Highhouse, S. (2002). A history of the T-group and its early applications in management development. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 6, 277–290. doi: 10.1037//1089-2699.6.4.277

Hinsz, V. B., Tindale, R. S., and Vollrath, D. A. (1997). The emerging conceptualization of groups as information processors. Psychol. Bull. 121, 43–64. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.43

Iorio, I., Sommantico, M., and Parrello, S. (2020). Dreaming in the time of COVID-19: a quali-quantitative Italian study. Dreaming 30, 199–215. doi: 10.1037/drm0000142

ISTAT (2020). Report: Struttura e Profili del Settore Non Profit. Available online at: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/248321 (accessed October 9, 2020).

Jacobs, S. (2016). The use of participatory action research within education-benefits to stakeholders. World J. Educ. 6, 48–55. doi: 10.5430/wje.v6n3p48

Kaneklin, C., Piccardo, C., and Scaratti, G. (a cura di). (2010). La Ricerca-Azione. Cambiare per Conoscere nei Contesti Educativi. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Kerkhoff, S. (2020). Collaborative video case studies and online instruments for self-reflection in global teacher education. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 28, 341–351. Available online at: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216212/

Kim, L. E., and Asbury, K. (2020). ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: the impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. Educ. Psychol. 90, 1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12381

Konradt, U., Otte, K. P., Schippers, M. C., and Steenfatt, C. (2016). Reflexivity in teams: a review and new perspectives. J. Psychol. 150, 153–174. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2015.1050977

Kulig, J. C. (2000). Community Resiliency: the potential for community health nursing theory development. Public Health Nurs. 17, 374–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00374.x

Lancia, F. (2004). Strumenti per l'Analisi dei Testi. Introduzione All'uso di T-LAB. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Leitch, R., and Day, C. (2020). Action research and reflective practice: towards a holistic view. Educ. Action Res. 8, 179–193. doi: 10.1080/09650790000200108

Lines, R. L. J., Pietsch, S., Crane, M., Ntoumanis, N., Temby, P., Graham, S., et al. (2021). The effectiveness of team reflexivity interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 1–58. doi: 10.1037/spy0000251

Lipari, D., and Scaratti, G. (2014). “Comunità di pratica,” in Formazione. I Metodi, (a cura di) G. P. Quaglino (Milano: Raffaello Cortina), 207–232.

Lodder, A., Papadopoulos, C., and Randhawa, G. (2020). Using a blended format (videoconference face to face) to deliver a group psychosocial intervention to parents of autistic children. Internet Interv. 21:100336. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100336

Manuti, A. (2006). La costruzione narrativa del sé professionale. Repertori 1568 interpretativi e schemi di sé in un campione di giovani alla prima occupazione. 1569 Narr. Grup. Prospet. Clin. Soc. 1, 1–43. Available online at: http://www.narrareigruppi.it/index.php?journal=narrareigruppi&page=article&op=view&path%5B%5D=78&path%5B%5D=0

Manuti, A., Scardigno, R., and Mininni, G. (2017). Diatexts at work. The diatextual approach as a psycho-cultural path of critical discourse analysis in the organizational context. Qual. Res. J. 17, 319–334. doi: 10.1108/QRJ-07-2016-0044

Marcosa, J., Miguela, E., and Tillemab, H. (2009). Teacher reflection on action: what is said (in research) and what is done (in teaching). Reflect. Pract. 10, 191–204. doi: 10.1080/14623940902786206

Matyushkina, E. Y., and Kntemirova, A. A. (2019). Professional burnout and reflection of professionals helping professions. Counsel. Psychol. Psychother. 27, 50–68. doi: 10.17759/cpp.2019270204

Moreno, C. (2009). La ricerca-azione nel contesto di un intervento sociale ed educativo: il progetto chance a Napoli dal 1998 al 2008. Ricer. Psicol. 3, 197–217. doi: 10.3280/RIP2009-003012

Morgan, A., Brown, R., Heck, D., Pendergast, D., and Kanasa, H. (2013). Professional identity pathways of educators in alternative schools: the utility of reflective practice groups for educator induction and professional learning. Reflect. Prac. Int. Multidiscipl. Perspect. 15, 579–591. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2012.749227

Myers, K., Martin, E., and Brickman, K. (2020). Protecting others from ourselves: self-care in social work educators. Social Work Educ. 2020, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2020.1861243

O'Connor, D. B., Aggleton, J. P., Chakrabarti, B., Cooper, C. L., Creswell, C., Dunsmuir, S., et al. (2020). Research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a call to action for psychological science. Brit. J. Psychol. 111, 603–629. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12468

O'Leary, P., and Tsui, M. S. (2020). Ten gentle reminders to social workers in the pandemic. Int. Soc. Work 63, 273–274. doi: 10.1177/0020872820918979

Olivieri, F. (2019). Il tirocinio dell'educatore socio-pedagogico come sviluppo dell'identità professionale. Ann. Online Didatt. Formaz. Doc. 11, 235–250. doi: 10.15160/2038-1034/2147

Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delveccio, E., and Espada, J. P. (2020). Immediate psychological effects of COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front. Psychol. 11:579038. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579038

Parola, A., Rossi, A., Tessitore, F., Troisi, G., and Mannarini, S. (2020). Mental health through the COVID-19 quarantine: a growth curve analysis on Italian young adults. Front. Psychol. 11:567484. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567484

Parrello, S. (2018). “Growing up in the suburbs: stories of adolescents at risk and of their Maestri di Strada,” in Idiographic Approach to Health, eds R. De Luca Picione, J. Nedergaard, M. F. Freda, and S. Salvatore (Charlotte, NC: Age Publishing), 161–176.

Parrello, S., Ambrosetti, A., Iorio, I., and Castelli, L. (2019b). School burnout, relational, and organizational factors. Front. Psychol. 10:1695. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01695

Parrello, S., Iorio, I., Carillo, F., and Moreno, C. (2019a). Teaching in the Suburbs: participatory action research against educational wastage. Front. Psychol. 10:2308. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02308

Parrello, S., Iorio, I., De Rosa, B., and Sommantico, M. (2020). Socio-educational work in at-risk contexts and professional reflexivity: the multi-vision group of “Maestri di Strada”. Soc. Work Educ. 39, 584–598. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2019.1651260

Parrello, S., and Moreno, C. (2021). Maestri di Strada in tempo di COVID-19. Psiche 1, 211–223. doi: 10.7388/101131

Perini, M. (2013). Balint. Il Metodo. Available online at: https://www.spiweb.it/spipedia/balint-il-metodo/ (accessed September 14, 2013).

Petretto, D. R., Masala, I., and Masala, C. (2020). School closure and children in the outbreak of COVID-19. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 16, 189–191. doi: 10.2174/1745017902016010189

Pine, G. J. (2009). Teacher Action Research: Building Knowledge Democracies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Reinert, M. (1998). “Mondes lexicaux et topoi dans l'approche alceste,” in Mots Chiffrés et Déchiffrés, eds S. Mellet and M. Vuillaume (Paris: Honoré Champion Editeur), 289–303.

Rogora, C., and Bizzarri, V. (2020). “Non sarà più come prima”. Adolescenti e psicopatologia: alcune riflessioni durante la pandemia da COVID-19. Psicobiettivo 2, 137–148. doi: 10.3280/PSOB2020-002011

Rossolatos, G. (2020). A brand storytelling approach to COVID-19's terrorealization: cartographing the narrative space of a global pandemic. J. Destin. Market. Manage. 18:100484. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100484

Sabucedo, J. M., Alzate, M., and Hur, D. (2020). COVID-19 and the metaphor of war (COVID-19 y la metáfora de la guerra). Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 35, 618–624. doi: 10.1080/02134748.2020.1783840

Salvatore, S., and Zittoun, T. (2011). (eds.) Advances in Cultural Psychology. Cultural Psychology and Psychoanalysis: Pathways to Synthesis. Charlotte, NC: IAP Information Age Publishing.

Sanchez-Reilly, S., Morrison, L. J., Carey, E., et al. (2013). Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. J. Support. Oncol. 11, 75–81. doi: 10.12788/j.suponc.0003

Savin-Baden, M., and Wimpenny, K. (2007). Exploring and implementing participatory action research. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 31, 331–343. doi: 10.1080/03098260601065136

Schippers, M. C., Homan, A. C., and van Knippenberg, D. (2013). To reflect or not to reflect: prior team performance as a boundary condition of the effects of reflexivity on learning and final team performance. J. Organ. Behav. 34, 6–23. doi: 10.1002/job.1784

Schippers, M. C., West, M. A., and Dawson, J. F. (2015). Team reflexivity and innovation: the moderating role of team context. J. Manage. 41, 769–788. doi: 10.1177/0149206312441210

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professional Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Sim, J., and Waterfeld, J. (2019). Focus group methodology: some ethical challenges. Qual. Quan. 53, 3003–3022. doi: 10.1007/s11135-019-00914-5

Smorti, A. (2003). La Psicologia Culturale. Processi di Sviluppo e Comprensione Sociale. Roma: Carocci.

Sokal, L. J., EblieTrudel, L. G., and Babb, J. C. (2020). Supporting teachers in times of change: the job demands- resources model and teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Contemp. Educ. 3, 67–74. doi: 10.11114/ijce.v3i2.4931

Sommantico, M. (2010). La ciénaga. Ou le malaise dans la famille comme révélateur du Malaise dans la culture. Cah. Psychol. Clin. 34, 205–217. doi: 10.3917/cpc.034.0203

Spafford, M. M., Schryer, C. F., Campbell, S. L., and Lingard, L. (2007). Towards embracing clinical uncertainty: lessons for social work, optometry and medicine. J. Soc. Work 7, 155–178. doi: 10.1177/1468017307080282

Stapleton, S. R. (2018). Teacher participatory action research (TPAR): a methodological framework for political teacher research. Act. Res. 19:147675031775103. doi: 10.1177/1476750317751033

Striano, M., Malacarne, C., and Oliverio, S. (2018). La Riflessività in Educazione: Prospettive, Modelli, Pratiche. Brescia: Scholé.

Trevithick, P. (2011). Understanding defences and defensiveness in social work. J. Soc. Work Pract. 25, 389–412. doi: 10.1080/02650533.2011.626642

Truell, R. (2020). News from our societies – IFSW: COVID-19: the struggle, success and expansion of social work – reflections on the profession's global response, 5 months on. Int. Soc. Work 63, 545–548. doi: 10.1177/0020872820936448

Trust, T., Carpenter, J. P., Krutka, D. G., and Kimmons, R. (2020). #RemoteTeaching & #RemoteLearning: Educator Tweeting During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 28, 151–159. Available online at: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216094/

UNESCO (2020). Adverse Consequences of School Closures. UNESCO. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresp (accessed March 10 2020).

UNICEF (2020). COVID-19: are Children Able to Continue Learning During School Closures? A Global Analysis of the Potential Reach of Remote Learning Policies using Data from 100 Countries. Available online at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/remote-learning-reachability-factsheet/ (Accessed August 2020).

Urdang, E. (2010). Awareness of self. A critical tool. Soc. Work Educ. 29, 523–538. doi: 10.1080/02615470903164950

Usher, K., Bhullar, N., Durkin, J., Gyamfi, N., and Jackson, D. (2020). Family violence and COVID-10: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 29, 549–552. doi: 10.1111/inm.12735

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking Press.

van der Kolk, B. (2020). Nurturing our Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Bessel van der Kolk MD Discusses How We can Nurture our Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.besselvanderkolk.com/blog/how-we-can-nurture-our-mental-health-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed April 3, 2020).

van Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C. K. W., and Homan, A. C. (2004). Work group diversity and group performance: an integrative model and research agenda. J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 1008–1022. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.1008

Van Roy, K., Vanheule, S., and Inslegersm, R. (2015). Research on Balint groups: a literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 98, 685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.01.014

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Werzelen, W., Driessens, K., and Boxtaens, J. (2019). “Belgian social workers as piping engineers in the Belgian Welfare State,” in Austerity, Social Work and Welfare Policies: A Global Perspective, eds A. López Peláez and E. J. GómezCiriano (Cizur Manor: Thomson Reuters-Aranzadi),51–73.

Widmer, P. S., Schippers, M. C., and West, M. A. (2009). Recent developments in 1697 reflexivity research: a review. Psychol. Everyday Activ. 2, 2–11. Available online at: https://research.aston.ac.uk/en/publications/recent-developments-in-reflexivity-research-a-review

Keywords: socio-educational work, team reflexivity, action-research, COVID-19 lockdown, modified balint group, online group, T-lab text analysis

Citation: Parrello S, Fenizia E, Gentile R, Iorio I, Sartini C and Sommantico M (2021) Supporting Team Reflexivity During the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Qualitative Study of Multi-Vision Groups In-person and Online. Front. Psychol. 12:719403. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719403

Received: 02 June 2021; Accepted: 12 July 2021;

Published: 06 August 2021.

Edited by:

Terri Mannarini, University of Salento, ItalyReviewed by:

Rosa Scardigno, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyElisabetta Sagone, University of Catania, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Parrello, Fenizia, Gentile, Iorio, Sartini and Sommantico. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Santa Parrello, cGFycmVsbG9AdW5pbmEuaXQ=

Santa Parrello

Santa Parrello Elisabetta Fenizia

Elisabetta Fenizia Rosa Gentile

Rosa Gentile Ilaria Iorio

Ilaria Iorio Clara Sartini

Clara Sartini Massimiliano Sommantico

Massimiliano Sommantico