- 1Queensland Centre for Domestic and Family Violence Research, School of Nursing Midwifery and Social Sciences, CQUniversity Australia, Perth, WA, Australia

- 2Cluster for Resilience and Wellbeing, Appleton Institute, CQUniversity Australia, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3School of Nursing Midwifery and Social Sciences, CQUniversity Australia, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Sexual violence is a concerning public health and criminal justice problem. Even though extensive literature has linked sexual victimization to a multitude of mental and physical problems, some victim/survivors recover and are able to lead lives without notable negative impacts. Little is known about women who experienced posttraumatic growth following sexual victimization. This review brings together knowledge accumulated in the academic literature in the past decade. It was informed by the PRISMA-P guidelines. Databases were searched using a combination of keywords to locate original peer-reviewed research articles published between January 2010 and October 2020 focusing on posttraumatic growth following sexual victimization. The initial search identified 6,187 articles with 265 articles being read in full, identifying 41 articles that were included in the analysis. The results suggest that recovery from sexual victimization is possible with the healing process being idiosyncratic. Victim/survivors employed various strategies resulting in higher degrees of functioning, which were termed growth. Following a synthesis of themes that emerged from the thematic analysis, a higher order abstraction, using creative insight through reflexivity, discussions among the research team and consistent interpretation and re-interpretation of the identified themes as a second stage analysis, resulted in the identification of two superordinate topics “relationship to self” and “relationship to others.” Findings indicated that women engaged in deliberate introspection to connect with themselves and utilized altruistic actions and activism in an attempt to prevent further sexual victimization Helping victim/survivors deal with the sexual violence facilitated growth as a collective. We concluded that helping others may be a therapeutic vehicle for PTG. Given research in this area remains in its infancy, further investigation is urgently needed.

Introduction

Sexual violence, defined as unwanted sexual acts against someone (Ulloa et al., 2016), is a global public health and criminal justice problem (Du Mont et al., 2019). Prevalence rates vary considerably across studies with rates ranging from 10.7 to 21.2% for contact-based sexual violence and up to 15.1% for penetrative sexual offenses against children with consistent findings across international studies that girls are at a considerable higher risk of victimization than boys (Tanaka et al., 2017). Adult victimization of unwanted sexual experiences range from 54% among university students (Campbell et al., 2021) to 19% of victimization by rape for women and 2% for men (Breiding et al., 2014). Studies of sexual violence perpetration indicated that between 25 and 30% of male university students admitted to sexually assaulting a female since the age of 14 years with 68% of men indicating repeat sexual offending (Zinzow and Thompson, 2015). Prevalence rates of sexual violence in current intimate relationships ranged from 18 to 66% (Fernet et al., 2019).

It is important to note that because of multiple victimization definitions, participant characteristics (e.g., age cut offs), recruitment sources and settings, measures of sexual violence (e.g., self-report assessment vs. behavioral descriptors of rape, sexual coercion, non-contact sexual violence) used, prevalence rates tend to vary substantially across studies nationally and internationally, which makes comparisons difficult (Vitek and Yeater, 2020). Regardless of these limitations, studies consistently document high prevalence rates of sexual victimization, defined here as being subjected to inappropriate and/or non-consensual sexual acts, particularly against females (Campbell et al., 2021). Keeping these challenges of research in the area of sexual violence in mind, the following section examines the current knowledge to the major field of child sexual abuse (CSA), adult sexual assault (ASA), revictimization, and impact of sexual victimization.

Sexual Victimization

It is estimated that 1 in 7 girls and 1 in 25 boys will be sexually abused in childhood (Scoglio et al., 2019). Negative outcomes of child sexual abuse have been extensively documented in the literature (Domhardt et al., 2015). These include mental health problems such as symptoms of anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, dissociation as well as health risk behaviors including substance use problems as a coping mechanism (Guggisberg, 2012; Walker et al., 2019). Furthermore, CSA victimization increases the risk of repeat sexual victimization later in life (Messman-Moore and Long, 2003; Hawn et al., 2018).

Prevalence rates differ in studies investigating adult sexual victimization but estimates of nearly 30% have been reported (DeCou et al., 2017). Sexual victimization experiences either in childhood and/or in adulthood has been found to negatively impact the victim/survivor's functioning as well as interpersonal relationships (Vitek and Yeater, 2020).

Lately, researchers have become increasingly interested in understanding sexual revictimization. One consistent finding in the literature is that victim/survivors of sexual abuse tend to be drawn to abusive intimate partners (Vitek and Yeater, 2020). Intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) has been found to have the most severe and longterm negative effects when compared to other forms such as emotional abuse and/or physical violence (Guggisberg, 2018).

Impact

Sexual violence has been described as a significant traumatic experience due to the perceived and loss of control over the victimized person's body. This can significantly impact the person's worldview and increase a sense of vulnerability (Ullman and Peter-Hagene, 2014). Strong evidence indicates an association between mental health problems including low self-esteem, anxiety and depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (Scott et al., 2018) and maladaptive coping such as alcohol and/or other drug use (Scoglio et al., 2019; Culatta et al., 2020) and physical health impacts (Guggisberg, 2018). Compared to other forms of interpersonal violence, sexual violence has unique negative impacts including the risk of developing sexually transmitted infections, unwanted pregnancies and other reproductive consequences (Guggisberg, 2021). It is important to note that sexual violence victimization is an idiosyncratic experience and generalization of impacts should be conducted with caution (McFerran et al., 2020), particularly against the background of recent research indicating that posttraumatic growth, defined by Ulloa and colleagues (2016) as “personal transformation that improves quality of life” (p. 293), is possible.

Posttraumatic Growth

Recent literature indicates that some victim/survivors of sexual violence are able to recover (Domhardt et al., 2015). Research found that psychological and emotional growth is related to positive behavior change (Tedeschi et al., 2018). Several concepts have been used in the literature to describe positive adaptation to CSA victimization including “resilience” (Domhardt et al., 2015) and “posttraumatic growth” (PTG) (Tedeschi et al., 2018). PTG has been conceptualized as a person's positive responses to traumatic events (Muldoon et al., 2020). Typically associated with a person's reconstruction of self and reorientation of priorities and/or values (Tedeschi et al., 2018), with experiences of social support (Muldoon et al., 2020).

Consequently, PTG emphasizes longterm changes following a traumatic event. Tedeschi et al. and associates 2018 distinguished between resilience (i.e., a person's intrapersonal attributes) and PTG, which is the result of permanent change in the aftermath of one or several traumatic events. The vast majority of research to date has focused on medical illness such as cancer (Ochoa Arnedo et al., 2019), natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes) (Hafstad et al., 2011), terror (Eisenberg and Silver, 2011) and war-related violence among affected individuals such as military personnel (Nordstrand et al., 2020). More recently, PTG research included domestic and family violence (DFV) including sexual violence (D'Amore et al., 2018). However, often no distinction was made between the types of violence experiences. Studies fail to distinguish between different forms of intimate partner violence and whether the women had a history of prior victimization.

One review of the literature on sexual victimization and PTG by Ulloa et al. (2016) was identified. Even though the review omitted to use a systematic method and used a gender-neutral approach, findings indicated that victim/survivors reported positive change characterized by engaging in advocacy and activism as a concern for others and factors such as disclosure, social support and spirituality being influencing factors. However, Ulloa et al. (2016) acknowledged the paucity of knowledge on PTG specifically in relation to sexual victimization, which is conceptually different from other forms of trauma and called for further research to inform clinical practice. This systematic review of the literature addresses the gap in the literature on PTG among women who experienced sexual violence.

The Current Study

Theoretical Underpinnings

Systematic reviews, like other studies, are underpinned by the researchers' perspectives about the topic under investigation (Alexander, 2020). The authors were cognisant of, and sensitive to, the theoretical context, which is outlined below, that inevitably affected the review process at every stage. Sexual violence is inherently gendered (Guggisberg, 2018). In this regard (Brison, 2020) argued that sexual violence is to be understood as “group-based gender-motivated violence against women” (p. 308). Feminist perspectives draw attention to the gendered nature of violence against women and children particularly in relation to harm sustained from sexual victimization (Alcoff, 2018).

Rationale

The rationale for this study was that research in the area of sexual victimization predominantly focusses on negative impacts and the long-lasting negative debilitating effects for victim/survivors. While it is justified to continuously highlight the often devastating effects of sexual victimization, it is important to draw attention to the issue of PTG to balance the research and emphasize that some women recover from the trauma and are able to lead satisfactory lives. Given the recent focus on wellbeing and resiliency against the background of adversity, investigating contexts and circumstances of sexual victimization and common factors and behaviors that may be associated with PTG appears particularly relevant. This review's aim was to systematically review the current knowledge on PTG in women who experienced sexual violence in the past. The specific research question guiding this review was: “What are common signs of posttraumatic growth for adult women who experienced sexual violence?” As outlined above this question warrants a review of current knowledge to fill the gap in the literature.

Methods

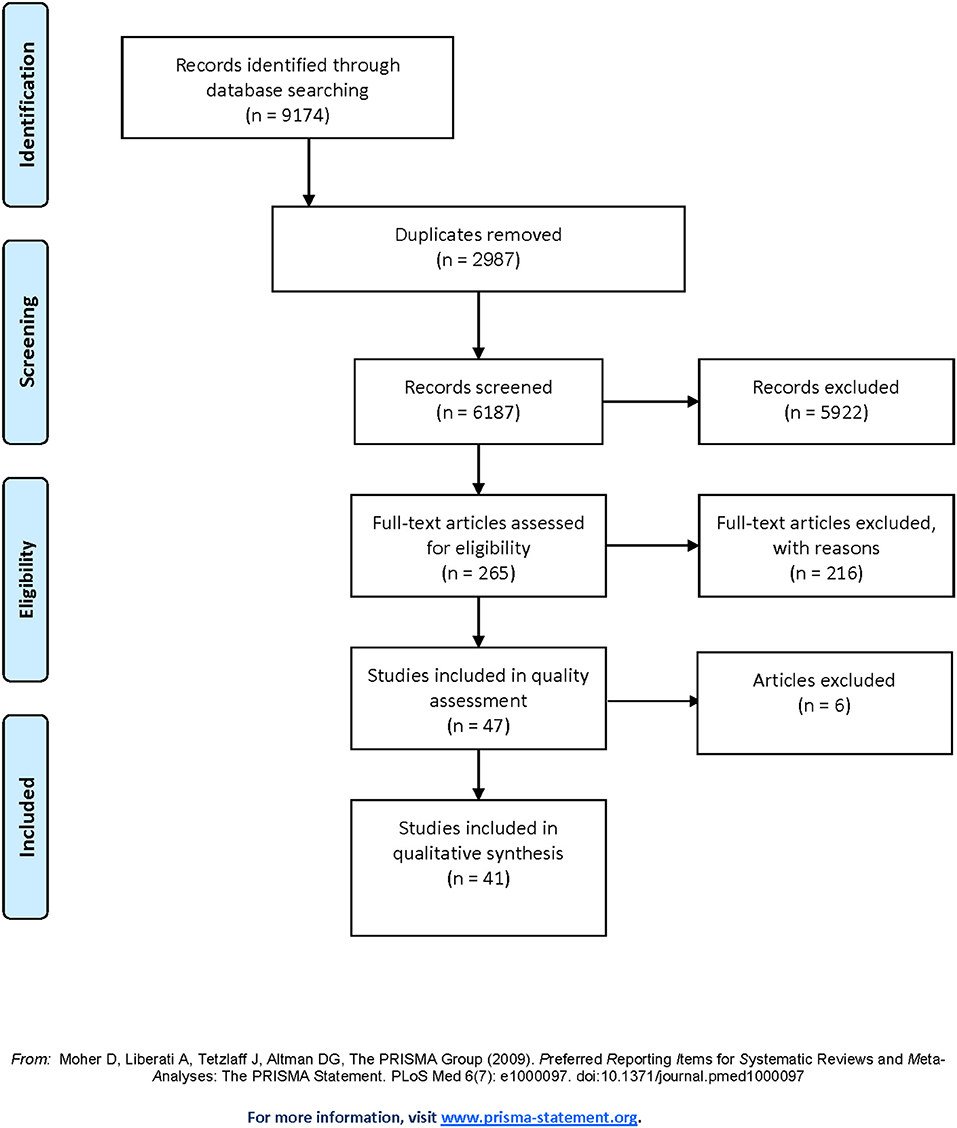

The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) framework (Moher et al., 2015) to identify and analyze published articles specific to sexual victimization and PTG. This review identified qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies on sexual violence and PTG.

Procedure

A systematic search of research studies was undertaken after scoping searches focused on PTG following sexual victimization. The research team, consisting of two experienced senior researchers who previously conducted systematic reviews and a student researcher developed a research protocol. All decisions including aim, criteria for inclusion, search strategies, key words and concepts, methods of review, quality assessment and data analysis, were made in collaboration, which included reviews and revisions until agreement was reached.

Literature Search Strategy

The second author, under close supervision, searched the following databases: Ebscohost, Google Scholar, PsycINFO, Medline, OVID, and Web of Science to identify relevant records. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were included using multiple keywords sets and synonyms (singular and plural forms and different spelling) such as child sexual abuse, adult survivors, healing, recovery, posttraumatic growth, sexual assault, sexual violence, and rape. Various search operators including truncation and wildcard symbols were used to identify studies until no new articles were found.

Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used to identify relevant articles on PTG following sexual victimization: (a) and peer reviewed academic articles of original research in English, (b) published between January 2010 and October 2020, (c) female victim/survivors of sexual violence who reported PTG. To be included, studies had to be conducted on sexual victimization and PTG with female participants.

Exclusion Criteria

When studies included other forms of DFV (e.g., emotional abuse, physical violence), only information about sexual violence was considered. Studies were excluded on child abuse and/or intimate partner violence if no sexual violence measure was reported. Studies with samples of only male victims of sexual violence and participants where results were not distinguishable by gender were also excluded from this review. Furthermore, commentaries, government reports, newspaper and web-based articles, brochures, newsletters, conference papers and student theses were excluded along with research articles published in a language other than English.

Nearly 9,200 records were identified with 2,987 duplicates leading to 6,187 records. As suggested by Belur et al. (2021), we attempted to reduce errors due to fatigue effects by undertaking the initial identification process in “small batches.” Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility following the removal of duplicates. Furthermore, a cautious approach was taken to reduce the potential of excluding a possible relevant article. If the decision for exclusion at this stage was unclear, the record was included. The interpretation of this bivariant screening process (i.e., decision whether to include or exclude a study) was closely observed by the first and second author using a constant comparison approach. The number of studies identified as being included varied slightly when results were compared. Consistent reflections and discussions about how to understand the task of applying the criteria enhanced the confidence in this process and reduced the risk of bias.

Two hundred and sixty-five full text articles were read and discussed by the first and second author to confirm inclusion in the review. Results were compared, reasoning for decisions included individual reflection on decisions and disagreements reconciled. Clarity on inclusion and exclusion criteria was enhanced and carefully recorded using an audit trail. Full text reviews resulted in the exclusion of 218 articles for various reasons including unclear information on sexual violence and/or female victim/survivors. Decisions were made in collaboration and discrepancies during this process were resolved through discussions using individual reflection and interpretation of the specific inclusion criteria. At this stage, the researchers applied their clinical knowledge of the research topic and well developed reflective practice on the final decisions for inclusion of articles, which further enhanced reliability. This was important as accuracy and consistency of inclusion decisions are influenced by the researchers' knowledge and understanding of the subject matter (Belur et al., 2021). Before articles were included in the final review, an independent quality appraisal by the first and second author was conducted utilizing the standardized quality assessment Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic reviews (Hong et al., 2018), which has showed content validity and reliability (Hong et al., 2019).

Each study received a specific quality rating score, which ranged from 0 to 6. Studies with total scores between 4 and 6 were considered high quality with low risk of bias. Those with a score of 3 were considered borderline and discussed by the researchers to arrive at an agreement of inclusion or exclusion. Studies given a score of 2 or less were automatically excluded for lack of methodological confidence (e.g., no identified research question, low quality of methods and/or measurement, and inappropriate source population). Given the potential risk of bias, it was mutually agreed to exclude 6 studies from the review. Meticulous record keeping ensured inter-rater agreement during the data extraction and assessment process, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Data Analysis

Data were contextualized and analyzed using a thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006). After the development of initial themes, we discussed the themes on an iterative basis before interpreting our finding in an attempt to understand PTG conceptualizations at a more abstract level that enables generalization of our findings (Eakin and Gladstone, 2020). Generating generalizable concepts, according to Eakin and Gladstone (2020) is a key objective of quality analysis. This creative insight is a result of reflexivity, discussion among the researchers and consistent interpretation and re-interpretation of the identified themes.

Findings

General Study Characteristics

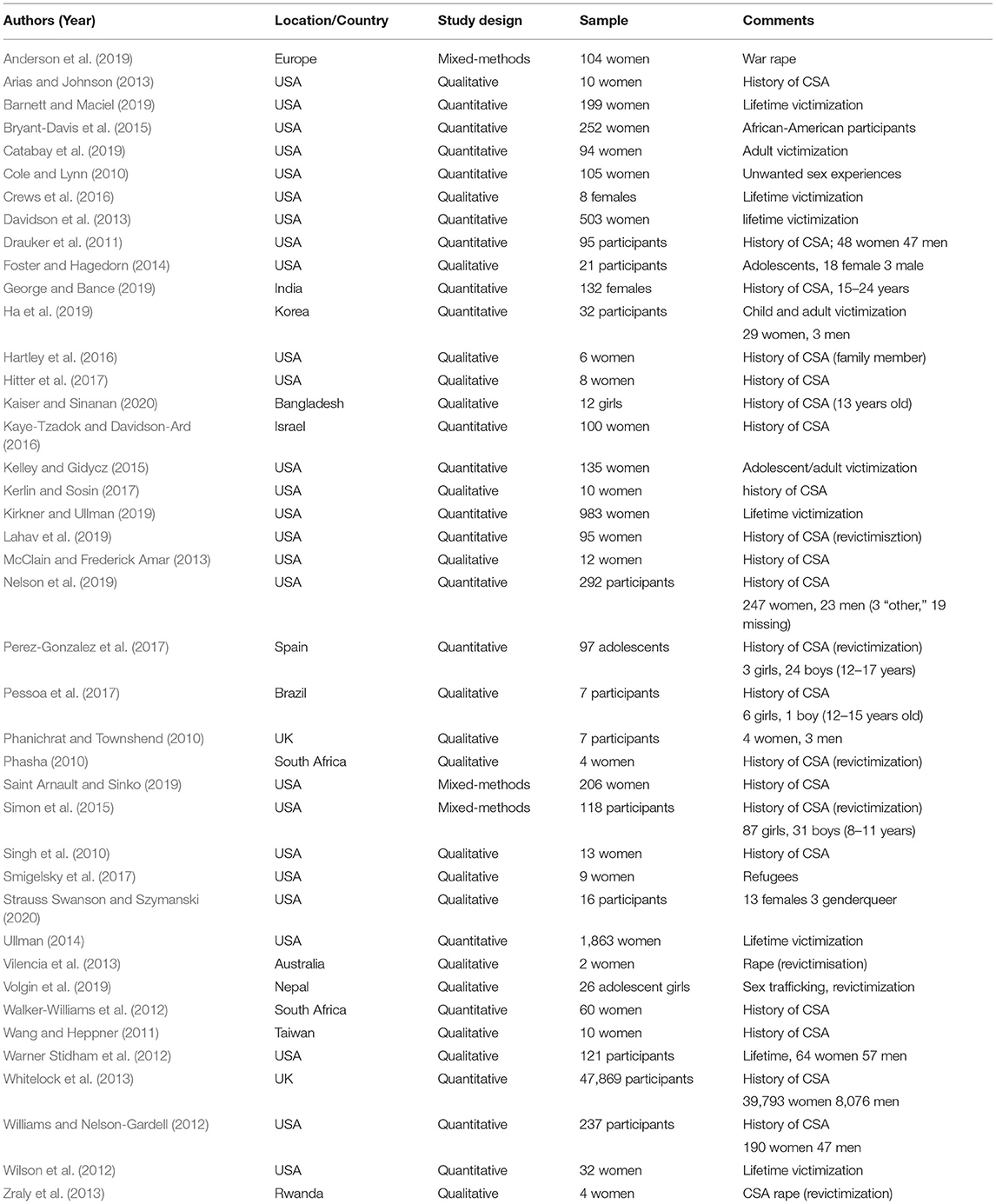

A summary of general study characteristics is presented in Table 1. All 41 articles reported on PTG following female sexual victimization. The sample sizes of studies ranged from 2 to 39,703 with 19 (48.8%) studies having used qualitative, 19 (46.3%) quantitative, and 3 (7.3%) mixed-methods. The vast majority (63.4%) of studies were conducted in the USA (Cole and Lynn, 2010; Singh et al., 2010; Drauker et al., 2011; Warner Stidham et al., 2012; Williams and Nelson-Gardell, 2012; Wilson et al., 2012; Arias and Johnson, 2013; Davidson et al., 2013; McClain and Frederick Amar, 2013; Foster and Hagedorn, 2014; Ullman, 2014; Bryant-Davis et al., 2015; Kelley and Gidycz, 2015; Simon et al., 2015; Crews et al., 2016; Hartley et al., 2016; Hitter et al., 2017; Kerlin and Sosin, 2017; Smigelsky et al., 2017; Barnett and Maciel, 2019; Catabay et al., 2019; Kirkner and Ullman, 2019; Lahav et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2019; Saint Arnault and Sinko, 2019; Strauss Swanson and Szymanski, 2020) followed by European studies with 9.8% (Phanichrat and Townshend, 2010; Whitelock et al., 2013; Perez-Gonzalez et al., 2017; Anderson et al., 2019), and two in South Africa (Phasha, 2010; Walker-Williams et al., 2012). One study each was from Australia (Vilencia et al., 2013), Bangladesh (Kaiser and Sinanan, 2020), Brazil (Pessoa et al., 2017), India (George and Bance, 2019), Israel (Kaye-Tzadok and Davidson-Ard, 2016), Korea (Ha et al., 2019), Nepal (Volgin et al., 2019), Rwanda (Zraly et al., 2013), and Taiwan (Wang and Heppner, 2011). Twenty-two studies (53.7%) placed specific focus on CSA while six studies (14.6%) examined lifetime sexual victimization and some used specific participants such as sexual trafficking and wartime victim/survivors. The vast majority of studies were cross-sectional (85.4%). Six studies (14.6%) used a longitudinal design (see Table 1).

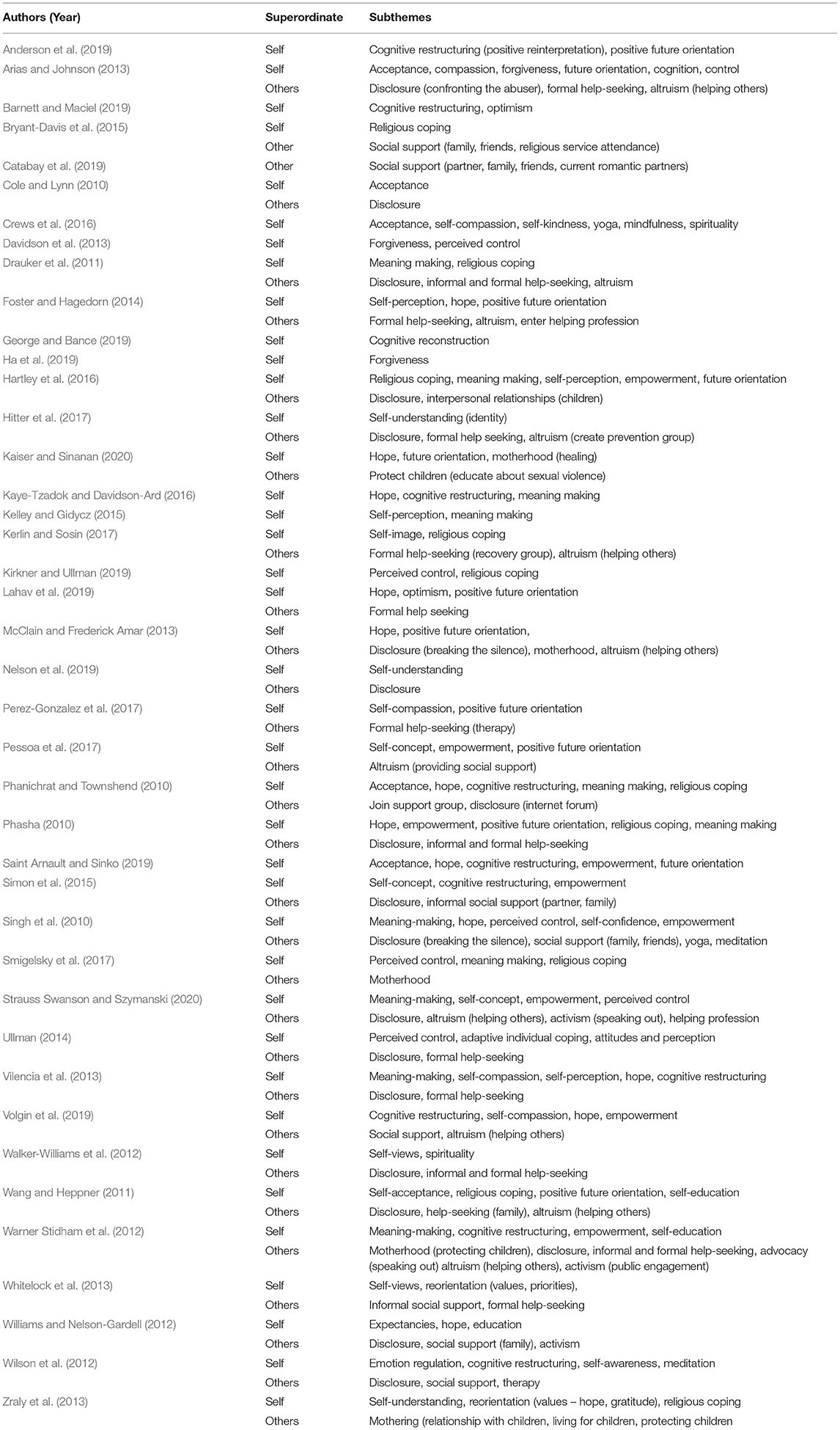

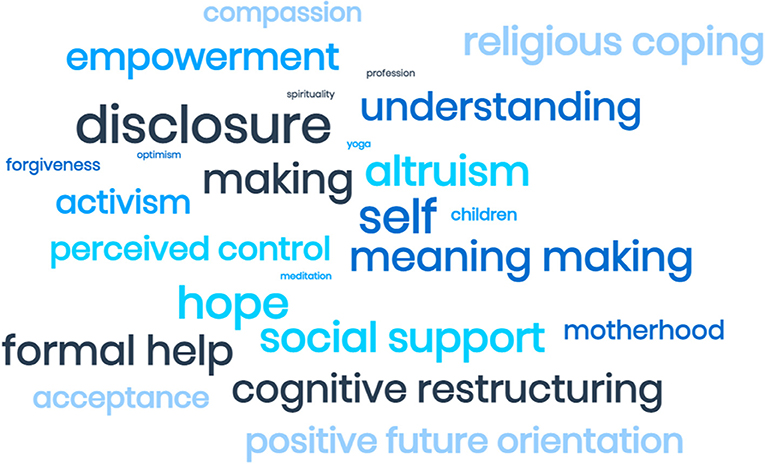

The thematic analysis found that all studies reported some form of PTG occurring with variations according to study focus and revictimization experiences. Within the studies, noteworthy inconsistencies in conceptualizations of PTG as well as varying methods utilized to describe and assess PTG were observed. Researchers conceptualized PTG by obtaining an overall rating using specific measures such as the PTG Inventory (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996), its short form (Cann et al., 2010), whereas others assessed PTG through women's subjectively held attitudes, actions, and evaluations of their recovery. Participants agreed that their sexual victimization experiences should not be forgotten. The studies indicated a willingness to not let the past control their present or future and the decision to actively engage in different ways in an attempt to get beyond the traumatic experiences, often coupled with faith, positive rather than negative thinking, and deliberate actions such as help seeking, activism and advocacy (Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the words/phrases used by the studies to describe PTG. Numerous words pointed to introspection and efforts to reaching out. Further interpretation and reflective discussions resulted in two abstract overarching themes “relationship to self” and “relationship to others” (see Table 2), which will be discussed below.

Relationship to Self

The majority of studies revealed that women learned to connect with themselves in new ways upon engaging in deliberate introspection. Many studies reported how participants utilized trauma-related affective and cognitive coping mechanisms including searching for meaning, taking control, and engaging in decision making processes. Numerous studies reported that after becoming aware of their emotions and thoughts women changed effortful cognitive and behavioral avoidance behaviors and engaged in mobilizing effortful strategies that resulted in a reduction of negative symptoms and increased their functioning ability and quality of life. Participants focusing on themselves, engaging in cognitive and behavioral techniques have been found to experience empowerment and recovery from sexual victimization. These insights developed in the context of informal social support and therapy after professional help seeking efforts.

Relationship to Others

Most studies indicated that women sought relationships with others. Engaging with others after sexual victimization can be particularly challenging, which is why some women prefer a coping strategy that does not involve relationship with others (Ha et al., 2019). The reason for some women's difficulties establishing relationships with others after sexual victimization is the impact of secrecy and betrayal, particularly if the perpetrator was a biological father (Guggisberg, 2017). It is important to note that the decision not to seek social support should be seen as an expression of perceived control rather than a sign of helplessness (Wasco, 2003).

Findings of this review indicated that the vast majority of women disclosed their sexual victimization and sought informal and/or formal support. Women in several studies indicated that they experienced a sense of belonging and recovery through social engagement such as music, yoga and religious service attendance. The studies reported that the experience of interaction was beneficial in that it was perceived as empowering and enhanced self-understanding. Social engagement in the aftermath of sexual victimization has been found to assist women in establishing safety and stability followed by reconstructing the trauma narrative through means of music and other forms of creative therapy (Herman, 2015). Herman (2015) advocated for meaning-making and using reflection as an integrated effort to re-establish ownership of self. The process of reconnecting with self, integrating the victimization experiences, is an integral part of the recovery process, which allows victim/survivors to experience self-compassion and grief whereby connecting with the traumatic experiences emotionally to self-sooth and physically reconnect with their body. Religious engagement, music and yoga have been mentioned by several studies, that align with Herman's (2015) theoretical explanation of integrating the women's private and public self.

Furthermore, women actively engaged in altruism by helping other victim/survivors Importantly, it has been recognized that victim/survivors themselves are excellently situated to engage in peer support as they understand the importance of choice, which, unsurprisingly, has been associated with experiences of recovery from trauma (Sweeney et al., 2018).

Combining the Relationships

Most studies indicated that engaging with oneself and others was a mutually inclusive process. Experiencing inner healing led to social engagement, which furthered feelings of empowerment and control in a bidirectional fashion. Sweeney et al. and colleagues 2018 explained this observation with what they referred to as the “triangle of wellbeing,” an “interaction between the social, personal and biological realms” (p. 319). Indeed, sexual victimization has been found to have an impact on neurobiological processes particularly if retraumatization occurs (Guggisberg, 2017; Sweeney et al., 2018). In this regard, Guggisberg (2017) emphasized the importance of therapy particularly in relation to intergenerational healing and recovery.

Taken together, women who experience PTG are generally utilizing a combination of strategies that can be subsumed under relationship to “self” and “others.” Victim/survivors have in common the desire to regain control over their bodies, minds, and regaining a sense of trust in people. This inner struggle and pursuit of integrating their sexual victimization experience into a new sense of self and with others can be explained as PTG with a deliberate choice to take proactive steps rather than escape and avoidance strategies.

Once the realization of choice and decision making is achieved, the individual is free to open their mind and facing the option of choosing to change the status quo (Schick, 1998). Schick (1998) indicated: “we have options… to make a choice… to choose is to come to want to take this or that option we have. To choose is to come to want something that is an option for us… we must try to think of wanting in anon-hedonic way, in a way that allows for our wanting what we know will be painful” (p. 11). For a victim/survivor of sexual violence this means confronting coping behaviors associated with the sexual trauma, which Schick (1998) conceptualized as an “inner changing” (p. 12) whereby things appear in a new light and understanding reasons behind the actions that are possibilities to be chosen. Similarly, Bermudez (2018) indicated that motivation for a particular change in behavior over another can be explained as exercising self-control. Being aware of various options and the possibility to choose, is engaging in conscious decision making, which entails thinking about a desired outcome and working toward an identified goal (Bermudez, 2018). Several studies indicated the importance of self-control, empowerment and positive future orientation (see Table 2).

Speaking Out

Relationships with self and others were discussed in 30 studies where participants indicated how they were able to engage with others after self-discovery. Interpersonal relationships were described as helpful in the recovery process for the women and many indicated the need for breaking the silence about their sexual victimization as indicated in 18 studies, even specifically confronting their abuser (Arias and Johnson, 2013), or helping others by various means such as creating a specific recovery group (Kerlin and Sosin, 2017) but also prevention group (Hitter et al., 2017) and entering a helping profession (Foster and Hagedorn, 2014). Victim/survivors seem to enact agency by speaking out about their experiences of sexual harm along with the desire to speak for others who share the same experiences. Talking about sexual victimization experiences publicly has become a movement, which creates collectivity (Alcoff, 2018).

Given the risk of non-supportive responses including victim-blaming statements following disclosure of sexual victimization (Bhuptani et al., 2019), many women feel safer to voice their experiences anonymously online (Mendes et al., 2019). Women disclosing their sexual victimization using social media have reported experiencing liberation and feeling empowered in having their voices heard Positive reactions to disclosures of sexual victimization have been related to perceived control and increased feelings of self-efficacy as described by several studies. In this regard, it is important to note that even negative responses to disclosure have resulted in increased perceived control and positive coping efforts (Ullman and Peter-Hagene, 2014). Digital disclosure of sexual victimization has been described as being part of a broader movement of speaking out such as #Me Too and #BeenRapedNeverReported, which has been associated with reduced risk of revictimization and improved psychological health (Moors, 2013). A discussion about the possible challenges of using social media as a means of disclosure is beyond the scope of this paper. However, making allegations of sexual violence against a specific person can be ethically and legally problematic (Salter, 2013).

Six studies specifically mentioned women engaging preventatively to ensure their children were protected from sexual violence. Not only did the women recognize their potential and unique position in protecting their children from child sexual abuse (Guggisberg et al., 2021), their children from child sexual abuse but their sense of control and personal agency was related to a positive future orientation and increased confidence, as discussed by nearly half of the studies. To take control over their lives in an attempt to overcome the traumatic events tended to lead to experiencing a sense of agency, resulting in altruism and advocacy behaviors. As discussed above, online communities have become increasingly used by women to discuss their sexual victimization, which have not only been recognized as an avenue for activism but an important support mechanism, especially for women who are geographically isolated as online platforms are easily accessible and contribute to a sense of connectedness (Serisier, 2019).

Strengths and Limitations

This review substantially advances knowledge on PTG among female victim/survivors of sexual violence. It not only provides an overview and summary of indicators associated with PTG but goes beyond by theorizing about victim/survivors' relationship to self and others. Regardless, the results of this review should be considered in the light of the following limitations: Firstly, focus was placed on female victim/survivors of sexual violence, which means findings may vary for males. Perhaps a separate study involving males would be helpful in assessing this point. Furthermore, even though a large amount of studies was identified published between 2010 and 2020, it is possible that some information was missed due to the publication date limits set. Additionally, as Belur et al. and colleagues 2021 argued, subjectivity must be acknowledged, which may impact the selection of records included in the review. The studies identified in this paper only represent peer-reviewed original research publications; information presented in theses, government reports and conference papers may have been omitted due to the restrictive inclusion criteria. Consequently, generalizability may be limited by the researchers' interpretations of the subject matter along with varying cultural contexts that were not comprehensively explored in this review. Therefore, further research may benefit from removal of time limits, the inclusion of publications other than peer-reviewed studies only, an examination of specific cultural implications, not only for female but male victim/survivors and those identifying as non-cisgender individuals along with quantitative studies that use a meta-analysis approach. Further research should explore PTG experiences among women who were subjected to multiple types of sexual victimization (i.e., in childhood, adolescence, and/or adulthood) in their lifetime to better understand the specific implications of PTG associated with revictimization. There is a need for further research focusing specifically on different types of sexual victimization in childhood vs. adolescence and adulthood. Age-related research may uncover different coping and help-seeking strategies in relation to PTG.

Conclusion

This review systematically and methodically examined the literature on the two constructs sexual violence victimization and PTG among female victim/survivors. Findings revealed that recovery from sexual victimization is possible as the 41 analyzed articles indicated. The numerous identified themes suggested that the healing process is idiosyncratic and an individual journey for victim/survivors and many different strategies were employed by the women who participated in the studies that were reviewed. Common themes involved women's self-reflection and meaning making activities, resulting in higher degrees of functioning and positive change, which were termed growth. Cognitive appraisal involved having control and decision making abilities that were experienced as empowering. The articles emphasized the interaction between women's search for meaning, valuing themselves and finding a new purpose and meaning in life and analysis revealed the importance of the notions of control and decision making. Following a synthesis of themes that emerged, a higher order abstraction resulted in the identification of two superordinate topics, which we categorized as “relationship to self” and “relationship to others,” leading to altruistic actions and activism in an attempt to prevent further sexual victimization. Helping victim/survivors deal with the sexual violence facilitated growth as a group, which points to the conclusion that helping others may be a therapeutic vehicle for PTG individually as well as collectively. We recommend developing interventions that reinforce the themes inherent in this review. Furthermore, given that research in this area remains in its infancy, further investigation is urgently needed.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MG and SB undertook the analysis and interpreting of the data with discussions of the texts and analytical thoughts involving all authors. MG contributed to the initial draft with the other authors critically reviewing numerous drafts, providing commentary on revisions during the pre-publication stage. All authors were responsible for the conceptualization and writing of this article.

Funding

Financial support was provided from the Cluster for Resilience and Wellbeing, CQUniversity; Grant No HE 3351.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alcoff, L. M. (2018). Rape and Resistance: Understanding the Complexities of Sexual Violation. Medford, MA: Polity Press.

Alexander, P. A. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: the art and science of quality systematic reviews. Rev. Educ. Res. 90, 6–23. doi: 10.3102/0034654319854352

Anderson, K., Delic, A., Komproe, I., Avidibegovic, E., van Ee, E., and Glaesmer, H. (2019). Predictors of posttraumatic growth among conflict-related sexual violence survivors from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Confl. Health 13, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0201-5

Arias, B., and Johnson, C. V. (2013). Treatment of childhood sexual abuse survivors: voices of healing and recovery from childhood sexual abuse. J. Child Sex. Abus. 22, 822–841. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2013.830669

Barnett, M. D., and Maciel, I. V. (2019). Counterfactual thinking among victims of sexual assault: Relationships with posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. J. Interpers. Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260598952629. [Epub ahead of print].

Belur, J., Tompson, L., Thornton, A., and Simon, M. (2021). Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociol. Methods Res. 50, 837–865. doi: 10.1177/0049124118799372

Bermudez, J. L. (2018). “Frames, rationality, and self-control,” in Self-control, Decision Theory, and Rationality: New Essays, eds J. L. Bermudez (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 179–202. doi: 10.1017/9781108329170.009

Bhuptani, P. H., Kaufman, J. S., Messman-Moore, T. L., Gratz, K. L., and DiLillo, D. (2019). Rape disclosure and depression among community women: the mediating roles of shame and experiential avoidance. Violence Against Women 25, 1226–1242. doi: 10.1177/1077801218811683

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., Walters, M. L., Chen, J., and Merrick, M. T. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization: National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey United States, 2011. Centers for Disease Control. Available online at: http://origin.glb.cdc.gov/mmwr/ss6308 (accessed September 15, 2020).

Brison, S. J. (2020). Can we end the feminist 'sex wars' now? Comments on Linda Martin Alcoff, Rape and resistance: understanding the complexities of sexual violation. Philos. Stud. 177, 303–309. doi: 10.1007/s11098-019-01392-z

Bryant-Davis, T., Ullman, S., Tsong, Y., Anderson, G., Counts, P., Tillman, S., et al. (2015). Healing pathways: longitudinal effects of religious coping and social support on PTSD symptoms in African American sexual assault survivors. J. Trauma Dissociation 16, 114–128. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2014.969468

Campbell, J. C., Sabri, B., Budhathoki, C., Kaufman, M. R., Alhusen, J., and Decker, M. R. (2021). Unwanted sexual acts among university students: correlates of victimization and perpetration. J. Interpers. Violence 36, 504–526. doi: 10.1177/0886260517734221

Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Taku, K., Vishnevsky, T., Triplett, K. N., et al. (2010). A short form of the Post Traumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 23, 127–137. doi: 10.1080/10615800903094273

Catabay, C. J., Stockman, J. K., Campbell, J. C., and Tsuyki, K. (2019). Perceived stress and mental health: the mediating roles of social support and resilience among black women exposed to sexual violence. J. Affect. Disord. 259, 143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.037

Cole, A. S., and Lynn, S. J. (2010). Adjustment of sexual assault survivors: hardiness and acceptance coping in posttraumatic growth. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 30, 111–127. doi: 10.2190/IC.30.1.g

Crews, D. A., Stolz-Newton, M., and Grant, N. S. (2016). The use of yoga to build self-compassion as a healing method for survivors of sexual violence. J. Religion Spiritual. Soc. Work Soc. Thought 35, 139–156. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2015.1067583

Culatta, E., Clay-Warner, J., Boyle, K. M., and Oshri, A. (2020). Sexual revictimization: a routine activity theory explanation. J. Interpers. Violence, 35, 1–25. doi: 10.1177/0886260517704962

D'Amore, C., Martin, S. L., Wood, K., and Brooks, C. (2018). Themes of healing and posttraumatic growth in women survivors' narratives of intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 36, NP2697–NP2724. doi: 10.1177/0886260518767909

Davidson, M. M., Lozano, M., Cole, B. P., and Gervais, S. J. (2013). Associations between women's experiences of sexual violence and forgiveness. Violence Victims 28, 1041–1053. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00075

DeCou, C. R., Cole, T. T., Lynch, S. M., Wong, M. M., and Matthews, K. C. (2017). Assault-related shame mediates the association between negative social reactions to disclosure of sexual assault and psychological distress. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 9, 166–172. doi: 10.1037/tra0000186

Domhardt, M., Muenzer, A., Fegert, J. M., and Goldbeck, L. (2015). Resilience in survivors of child sexual abuse: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 16, 476–493. doi: 10.1177/1524838014557288

Drauker, C. B., Martsolf, D. S., Roller, C., Knapik, G., Ross, R., and Warner Stidham, A. (2011). Healing from childhood sexual abuse: a theoretical model. J. Child Sex. Abus. 20, 435–466. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2011.588188

Du Mont, J., Johnson, H., and Hill, C. (2019). Factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology among women who have experienced sexual assault in Canada. J. Interpers. Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260519860084

Eakin, J. M., and Gladstone, B. (2020). “Value-adding” analysis: doing more with qualitative data. Int. J. Qual. Methods 19, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406920949333

Eisenberg, N., and Silver, R. C. (2011). Growing up in the shadow of terrorism: youth in America after 9/11. Am. Psychol. 66, 468–481. doi: 10.1037/a0024619

Fernet, M., Lapierre, A., Herbert, M., and Cousineau, M.-M. (2019). A systematic review of literature on cyber intimate partner victimization in adolescent girls and women. Comput. Human Behav. 100, 11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.06.005

Foster, J. M., and Hagedorn, W. B. (2014). Through the eyes of the wounded: a narrative analysis of children's sexual abuse experiences and recovery process. J. Child Sex. Abus. 23, 538–557. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2014.918072

George, N., and Bance, L. O. (2019). Coping strategies as a predictor of post traumatic growth among selected female young adult victims of childhood sexual abuse in Kerala, India. Indian J. Health Well-being 10, 236–240. Retrieved from: http://www.iahrw.com/index.php

Guggisberg, M. (2012). Sexual violence victimisation and subsequent problematic alcohol use: Examining the self-medication hypothesis. Int. J. Arts Sci. 5, 723–736. Available online at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Sexual-Violence-Victimisation-and-Subsequent-Use%3A-Guggisberg/1b5433ebf78ca19a7b27ca7cb8d5aa01a3e0cf8c

Guggisberg, M. (2017). The wide-ranging impact of child sexual abuse. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. Sci. 1, 255–264. Available online at: https://www.scientiaricerca.com/srcons/pdf/SRCONS-01-00039.pdf

Guggisberg, M. (2018). “The impact of violence against women and girls: a life span analysis,” in Violence Against Women in the 21st Century: Challenges and Future Directions, eds M. Guggisberg and J. Henricksen (New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 3–27.

Guggisberg, M. (2021). “Sexuality and sexual health: professional issues for nurses,” in Nursing in Australia: Contemporary Professional and Practice Insights, eds N. J. Wilson, P. Lewis, L. Hunt, and L. Whitehead (London: Routledge), 201–210. doi: 10.4324/9781003120698-25

Guggisberg, M., Botha, T., and Barr, J. (2021). Child Sexual Abuse Prevention—the Involvement Of Protective Mothers and Fathers: A Systematic Review. J. Fam. Stud. (forthcoming).

Ha, N., and Bae, S.-M. M.-H. H. (2019). The effect of forgiveness writing therapy on post-traumatic growth in survivors of sexual abuse. Sexual Relationsh. Therapy 34, 10–22. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2017.1327712

Hafstad, G. S., Kilmer, R. P., and Gil-Rivas, V. (2011). Posttraumatic growth among Norwegian children and adolescents exposed to the 2004 tsunami. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 3, 130–138. doi: 10.1037/a0023236

Hartley, S., Johnco, C., Hofmeyr, M., and Berry, A. (2016). The nature of posttraumatic growth in adult survivors of child sexual abuse. J. Child Abuse 25, 201–220. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2015.1119773

Hawn, S. E., Lind, M. J., Conley, A., Overstreet, C. M., Kendler, K. S., Dick, D. M., et al. (2018). Effects of social support on the association between precollege sexual assault and college-onset victimization. J. Am. College Health 66, 467–475. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1431911

Hitter, T. L., Adams, E. M., and Cahill, E. J. (2017). Positive sexual self-schemas of women survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Couns. Psychol. 45, 266–293. doi: 10.1177/0011000017697194

Hong, Q. N., Fabregues Feijoo, S., Bartlett, G., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., et al. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inform. 34, 285–b291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fabregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., et al. (2019). Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 111, 49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

Kaiser, E., and Sinanan, A. N. (2020). Survival and resilience of female street children experiencing sexual violence in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. J. Child Sex. Abus. 29, 550–569. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2019.1685615

Kaye-Tzadok, A., and Davidson-Ard, B. (2016). Posttraumatic growth among women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: its relation to cognitive strategies, posttraumatic symptoms and resilience. Psychol. Trauma 8, 550–558. doi: 10.1037/tra0000103

Kelley, E. L., and Gidycz, C. A. (2015). Labeling of sexual assault and the relationship with sexual functioning: the mediating role of coping. J. Interpers. Violence 30, 348–366. doi: 10.1177/0886260514534777

Kerlin, A. M., and Sosin, L. S. (2017). Recovery from childhood abuse: a spiritually integrated qualitative exploration of 10 women's journeys. J. Spiritual. Mental Health 19, 189–209. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2016.1247411

Kirkner, A., and Ullman, S. E. (2019). Sexual assault survivors' posttraumatic growth: Individual and community-led differences. Violence Against Women 26, 1987–2003. doi: 10.1177/1077801219888019

Lahav, Y., Ginzburg, K., and Spiegel, D. (2019). Post-traumatic growth, dissociation and sexual revictimization in female childhood sexual abuse survivors. Child Maltreat. 25, 96–105. doi: 10.1177/1077559519856102

McClain, N., and Frederick Amar, A. (2013). Female survivors of child sexual abuse: finding voices through research participation. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 34, 482–487. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2013.773110

McFerran, K. S., Lai, H. I. C., Chang, W.-H., Acquaro, D., Chin, T. C., Stokes, H., et al. (2020). Music, rhythm and trauma: a critical interpretive synthesis of research literature. Front. Psychol. 11:324. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00324

Mendes, K., Keller, J., and Ringrose, J. (2019). Digitized narratives of sexual violence: making sexual violence felt and known through digital disclosures. New Media Soc. 21, 1290–1310. doi: 10.1177/1461444818820069

Messman-Moore, T. L., and Long, P. J. (2003). The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: an empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 23, 537–571. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00203-9

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. BioMed Central 4, 1–9. Available online at: https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.118/2046-4053-4-1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Moors, R. W. R. (2013). The dance of disclosure: online self-disclosure of sexual assault. Qual. Soc. Work 12, 799–815. doi: 10.1177/1473325012464383

Muldoon, O. T., Haslam, S. A., Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Keams, M., and Jetten, J. (2020). The social psychology of responses to trauma: social identity pathways associated with divergent traumatic responses. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 30, 311–348. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1711628

Nelson, K. M., Hagedorn, W. B., and Lambie, G. W. (2019). Influence of attachment style on sexual abuse survivors' posttraumatic growth. J. Counsel. Dev. 97, 227–237. doi: 10.1002/jcad.12263

Nordstrand, A. E., Boe, H. J., Holen, A., Reichelt, J. G., Gjerstad, C. L., and Hjemdal, O. (2020). Social support and disclosure of war-zone experiences after deployment to Afghanistan—implications for posttraumatic deprecation or growth. Traumatology 26, 351–360. doi: 10.1037/trm0000254

Ochoa Arnedo, C., Sanchez, N., Sumalla, E. C., and Casellas-Grau, A. (2019). Stress and growth in cancer: mechanism and psychotherapeutic interventions to facilitate a constructive balance. Front. Psychol. 10, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00177

Perez-Gonzalez, A., Guilera, G., Pereda, N., and Jarne, A. (2017). Protective factors promoting resilience in the relation between child sexual victimization and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Child Abuse Neglect 72, 393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.006

Pessoa, A. S., Colmbra, R. M., Bottrell, D., and Noltemeyer, A. (2017). Resilience processes within the school context of adolescents with sexual violence history. Educ. Rev. 33, 1–25. doi: 10.1590/0102-4698157785

Phanichrat, T., and Townshend, J. M. (2010). Coping strategies used by supervisors of childhood sexual abuse on the journey to recovery. J. Child Abuse 19, 62–78. doi: 10.1080/10538710903485617

Phasha, T. N. (2010). Educational resilience among African survivors of child sexual abuse in South Africa. J. Black Stud. 40, 1234–1253. doi: 10.1177/0021934708327693

Saint Arnault, D., and Sinko, L. (2019). Hope and fulfillment after complex trauma: using mixed methods to understand healing. Front. Psychol. 10:2061. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02061

Salter, M. (2013). Justice and revenge in online counter-publics: emerging responses to sexual violence in the age of social media. Crime Media Cult. 9, 225–242. doi: 10.1177/1741659013493918

Schick, F. (1998). Making Choices: A Recasting of Decision Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Scoglio, A. A. J., Kraus, S. W., Saczynski, J., Jooma, S., and Molnar, B. E. (2019). Systematic review of risk and protective factors for revictimization after child sexual abuse. Trauma Violence Abuse 22, 41–53 doi: 10.1177/1524838018823274

Scott, K. M., Koenen, K. C., King, A., Petukhova, M. V., and Kessler, R. C. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder associated with sexual assault among women in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 48, 155–167. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001593

Serisier, T. (2019). “A new age of believing women? Judging rape narratives online,” in Rape Narratives in Motion, eds U. Anderson, M. Edgren, L. Karlsson, and G. Nilsson (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 199–222. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-13852-3_9

Simon, V. A., Smith, E., Fava, N., and Feiring, C. (2015). Positive and negative posttraumatic change following childhood sexual abuse are associated with youths' adjustment. Child Maltreatment 20, 278–290. doi: 10.1177/1077559515590872

Singh, A. A., Hays, D. G., Chung, Y. B., and Watson, L. (2010). South Asian immigrant women who have survived child sexual abuse: resilience and healing. Violence Against Women 16, 444–458. doi: 10.1177/1077801210363976

Smigelsky, M. A., Gill, A. R., Foshager, D., Aten, J. D., and Im, H. (2017). My heart is in his hands: the lived spiritual experiences of Congolese refugee women survivors of sexual violence. J. Prev. Interv. Commun. 45, 281–273. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2016.1197754

Strauss Swanson, C., and Szymanski, D. M. (2020). From pain to power: an exploration of activism, the #Me Too movement, and healing from sexualt assault trauma. J. Couns. Psychol. 67, 653–668. doi: 10.1037/cou0000429

Sweeney, A., Filson, B., Kennedy, A., Collinson, L., and Gillard, S. (2018). A paradigm shift: relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. Br. J. Psychiatry Adv. 24, 319–333. doi: 10.1192/bja.2018.29

Tanaka, M., Suzuki, Y. E., Aoyama, I., Takaoka, K., and MacMillan, H. L. (2017). Child sexual abuse in Japan: a systematic review and future directions. Child Abuse Neglect 66, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.041

Tedeschi, R. G., and Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The post-traumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 9, 455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305

Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Taku, K., and Caihoun, L. G. (2018). Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315527451

Ullman, S. E. (2014). Correlates of posttraumatic growth in adult sexual assault victims. Traumatology 20, 219–224. doi: 10.1037/h0099402

Ullman, S. E., and Peter-Hagene, L. (2014). Social reactions to sexual assault disclosure, coping, perceived control, and PTSD symptoms in sexual assault victims. J. Community Psychol. 42, 495–509. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21624

Ulloa, E., Guzman, M. L., and Cala, C. (2016). Posttraumatic growth and sexual violence: a literature review. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 25, 286–304. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1079286

Vilencia, S., Shakespeare-Finch, J., and Obst, P. (2013). Exploring the process of meaning making in healing and growth after childhood sexual assault: a case study approach. Counseling Psychology Quarterly 26, 39–54. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2012.728074

Vitek, K. N., and Yeater, E. A. (2020). The association between a history of sexual violence and romantic relationship functioning: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2020, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/1524838020915615

Volgin, R. N., Shakespeare-Finch, J., and Shochet, I. M. (2019). Posttraumatic distress, hope and growth in survivors of commercial sexual exploitation in Nepal. Traumatology 25, 181–188. doi: 10.1037/trm0000174

Walker, H. E., Freud, J. S., Ellis, R. A., Fraine, S. M., and Wilson, L. C. (2019). The prevalence of sexual revictimization: a meta-analytic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 20, 67–80. doi: 10.1177/1524838017692364

Walker-Williams, H. J., van Eeden, C., and van der Merwe, K. (2012). The prevalence of coping behavior, posttraumatic growth and psychological wellbeing in women who experienced childhood sexual abuse. J. Psychol. Africa 22, 617–622. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2012.10820576

Wang, Y.-W., and Heppner, P. P. (2011). A qualitative study of childhood sexual abuse survivors in Taiwan: toward a transactional and ecological model of coping. J. Couns. Psychol. 58, 393–409. doi: 10.1037/a0023522

Warner Stidham, A., Drauker, C. B., Martsolf, D. S., and Mullen, L. P. (2012). Altruism in survivors of sexual violence: the typologty of helping others. J. Am. Psychiatric Assoc. 18, 146–155. doi: 10.1177/1078390312440595

Wasco, S. M. (2003). Conceptualizing the harm done by rape: applications of trauma theory to experiences of sexual assault. Trauma Violence Abuse 4, 309–322. doi: 10.1177/1524838003256560

Whitelock, C. F., Lamb, M. E., and Rentfrow, P. J. (2013). Overcoming trauma: psychological and demographic characteristics of chold sexual abuse survivors in adulthood. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 1, 351–362. doi: 10.1177/2167702613480136

Williams, J., and Nelson-Gardell, D. (2012). Predicting resilience in sexually abused adolescents. Child Abuse Neglect 36, 53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.004

Wilson, D. R., Vidal, B., A, W. W., and Salyer, S. L. (2012). Overcoming sequelea of childhood sexual abuse with stress management. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 19, 587–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01813.x

Zinzow, H. M., and Thompson, M. (2015). A longitudinal study of risk factors for repeated sexual coercion and assault in U.S. college men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 44, 213–222. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0243-5

Keywords: posttraumatic growth, rape, recovery, sexual assault, trauma, victimization

Citation: Guggisberg M, Bottino S and Doran CM (2021) Women's Contexts and Circumstances of Posttraumatic Growth After Sexual Victimization: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 12:699288. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.699288

Received: 23 April 2021; Accepted: 30 July 2021;

Published: 26 August 2021.

Edited by:

Xue Yang, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Rui She, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaGuohua Zhang, Wenzhou Medical University, China

Copyright © 2021 Guggisberg, Bottino and Doran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marika Guggisberg, bS5ndWdnaXNiZXJnQGNxdS5lZHUuYXU=; orcid.org/0000-0003-1344-7330

Marika Guggisberg

Marika Guggisberg Simone Bottino3

Simone Bottino3 Christopher M. Doran

Christopher M. Doran