- Department of Mental Health, Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Background: About 3% of new cancer cases affect young adults aged between 15 and 39 years. The young age, the increasing incidence and the relatively good prognosis of this population lead to the growing importance to investigate the psychosocial long-term and late effects. The aims of the AYA-LE long-term effects study are: first, to assess the temporal course and related factors of life satisfaction and psychological distress of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors; and second, to examine a specific topic in each of the yearly surveys in a more differentiated way.

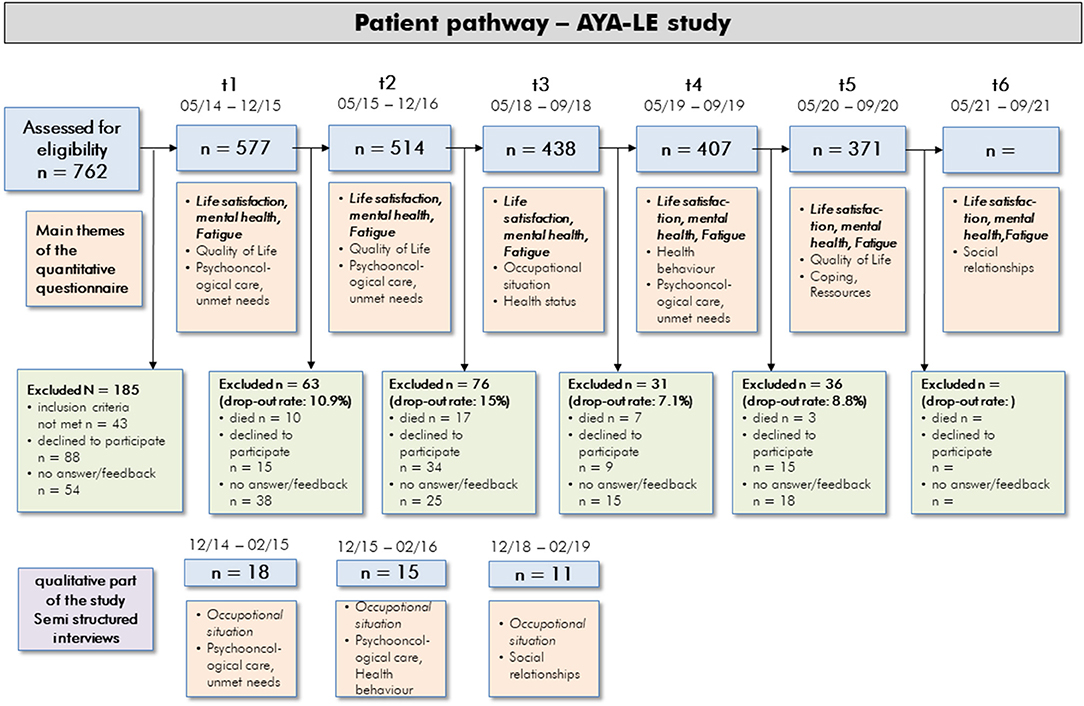

Methods: This study represents a continuation of the longitudinal AYA-LE study. The existing sample of AYA cancer patients (t1: N = 577; t2: N = 514; aged between 18 and 39 years at diagnosis; all major tumor entities) was extended by four further survey points (t3: 2018, t4: 2019, t5: 2020, t6: 2021). In addition, a comparison sample of young adults without cancer was collected. We measured longitudinal data for outcomes such as quality of life, psychological distress, and fatigue with standardized questionnaires. Furthermore, each survey point included a different cross-sectional topic (e.g., health behavior, occupational situation, and compliance).

Discussion: The AYA-LE long-term effects study will show the long-term consequences of cancer in young adulthood. We expect at least complete data of 320 participants to be available after the sixth survey, which will be completed in 2021. This will provide a comprehensive and differentiated understanding of the life situation of young adults with cancer in Germany. The findings of our study enable a continuous improvement of the psychosocial care and specific survivorship programs for young cancer patients.

Background

Around 3% of new cancer cases occur in young adults aged between 15 and 39 years (Gondos et al., 2013). This patient group is described by the National Cancer Institute as adolescent and young adults (AYA) (National Cancer Institute, 2019). Cancer in young adulthood is a non-normative life event (Brandstätter and Lindenberger, 2007) and often has significant physical, social and psychological consequences for those affected (Smith et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the complex developmental tasks that are typical of young adulthood (e.g., maturation of personality, entering into a partnership, starting a career, and starting a family and parenthood) have to be managed (Zebrack and Isaacson, 2012).

The young age, the increasing incidence in the last two decades (Smith et al., 2016; Fidler et al., 2017) and the above-average prognosis of this patient group increase the importance of questions of aftercare and long-term consequences for their care (Rabin et al., 2011). AYA survivors have an increased risk for the occurrence of long-term effects. In the 30 years following initial diagnosis, AYA are eight times more likely than their siblings to develop comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease (cardiotoxicity), endocrine and neurological disorders, diabetes or osteoporosis (Oeffinger et al., 2006). In addition, they have a two to three times higher risk of experiencing other cancers (AYA Oncology Progress Review Group, 2006; Hilgendorf et al., 2016).

The previous research findings have reported that AYA have a poorer quality of life and increased psychological stress when compared to their healthy peers (Quinn et al., 2015). In addition, it is known that young adults with cancer have high unmet supportive needs (Tsangaris et al., 2014). However, internationally, very few longitudinal studies have investigated the psychosocial situation of young adults with cancer.

Zebrack et al. (2014) interviewed patients up to a maximum of 16 months after diagnosis (t1: within 4 months after diagnosis; t2: 6 months after t1; t3: 12 months after t1) and showed that over one third of the participants reported a clinically significant level of distress at least once during the study period. Furthermore,12 months after diagnosis, 57% of the AYA patients expressed dissatisfaction with their level of information on at least one of the following topics: information on cancer itself, information on websites, infertility, physical activity or diet (Kwak et al., 2013). In their longitudinal study, Krüger et al. (2009) surveyed breast cancer patients up to 1 year after diagnosis. Compared to older patients, AYA patients had the lowest psychological burden but the relative differences to healthy peers were greater. Husson et al. (2017a,b) investigated n = 176 AYA patients with regard to their quality of life and post-traumatic growth at three points in the first 2 years after diagnosis. In terms of quality of life, the greatest improvement was seen in the first 12 months after cancer diagnosis. However, the quality of life of AYA patients compared to the age-matched general population was also significantly lower after 2 years. Furthermore, Chan et al. (2018) published a longitudinal study from the Asian region that examined the distress of AYA patients (N = 65) in the first 6 months after diagnosis. They showed that there was a decrease in distress from the time of diagnosis to 6 months later.

The few research findings to date regarding the psychosocial life situation of young adults with cancer are not sufficient to establish specific, comprehensive and structured follow-up concepts. Smith et al. (2019) emphasize the importance of the examination of late effects and psychosocial outcomes for the care of young cancer patients. In addition, many aspects of what is known about AYA have been deduced from long-term pediatric cancer survivors (Warner et al., 2016). The aim of the continuation of the study is: first, to assess the temporal course and related factors of life satisfaction and psychological distress of AYA cancer survivors; and second, in each of the yearly surveys, a specific topic of life will be examined in more detail in a cross-sectional design.

Based on the longitudinal study presented here with research-based data on essential life domains (e.g., occupational situation, health behavior, social relationship) of the AYA, urgently needed evidence-based survivorship programs can be designed and established.

Research Questions

The primary research questions follow:

1. What changes occur over time in regard to life satisfaction and psychological distress?

2. What other factors (e.g., sociodemographic, medical, and psychosocial) are associated with time changes in life satisfaction and psychological distress?

3. What differences exist between young adults with cancer compared to healthy peers in life satisfaction and psychological distress?

The selected further research questions follow:

4. How does the health behavior (e.g., nicotine consumption, alcohol consumption, use of illegal drugs, physical activity, nutrition, and adherence) of young adults with cancer compare to that of healthy people?

5. How does the current occupational situation (e.g., employment status, working hours per week, cognitive and physical performance, and income) of young adults with cancer change over time? And, how does it compare with that of healthy people?

Methods

Study Design

This study represents a continuation of the previous study “Life satisfaction, care situation and support needs of cancer patients in young adulthood” (AYA-LE study) (Leuteritz et al., 2017). This study is implemented as a prospective longitudinal survey, which extends the previous study with two measurement points (t1 and t2) by at least four further annual points in time (t3: 2018, t4: 2019, t5: 2020, t6: 2021). In addition, a comparison group of healthy young adults was surveyed at measurement time t3 and t4.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted at measurement time point's t1, t2, and t3, each repeated with the same interviewees and analyzed with Mayring's qualitative structuring content analysis. More detailed information on the measurement time points can be seen in Figure 1. The complete study was funded by the German Cancer Aid.

Participants

AYA Patients: Inclusion Criteria, Recruitment, and Data Collection

The patients must meet the following inclusion criteria:

1. Age at diagnosis: 18–39 years. (Our study aims to draw conclusions about patients treated in adult oncology departments. In Germany, patients younger than 18 years are treated in pediatric oncology units, and patients over 18 are treated in adult oncology units. This is the reason why we focused on 18–39 year olds).

2. First manifestation of cancer (all malignant tumor identities C00-C97).

3. Diagnosed within the last 4 years at t1.

4. Participation of the t1 and t2 survey.

AYAs are excluded from study participation if an initial screening of their data reveals that:

- They are unable to speak German;

- They are physically or cognitively unable to participate in the survey; or

- They did not provide written consent.

The recruitment in the AYA-LE study was managed in cooperation with four rehabilitations clinics, two tumor registries and 16 acute care hospitals. In May 2018, the 514 patients of the existing sample received an email link to answer the third study questionnaire (t3). The patients are already familiar with this procedure thanks to the first two survey time points (t1, t2). As in the previous study, the online questionnaire was created using the LimeSurvey software. If no email address was available or requested, then the participants received the questionnaire and documents by post.

Reminders were mainly sent by email continuously every 10 days. Approximately 4 weeks after the t3 invitation, patients who had not yet responded received a first postal reminder with questionnaire and participant documents in paper form. The second postal reminder took place 3 weeks later. Address data that were no longer up to date were updated at the residents' registration office. This procedure is now repeated for the yearly surveys, always including all of the participants of the last survey.

Comparison Group: Inclusion Criteria, Recruitment, and Data Collection

The inclusion criteria for the comparative sample were: women and men from the general population who had not had cancer were selected from the general population according to the age and gender of the patient sample at t2. The same exclusion criteria as for the AYA patients were applied.

For the formation of the comparative sample, group information was provided to the Leipzig Register of Residents to obtain a randomized list for men and women from the general population of Leipzig between 18 and 45 years of age. This requirement represented the average age and gender distribution of the AYA patient sample at t2. Taking recruitment drop outs into account, about three times as many people as the AYA sample at t2 (N = 514) were requested (N = 1,598).

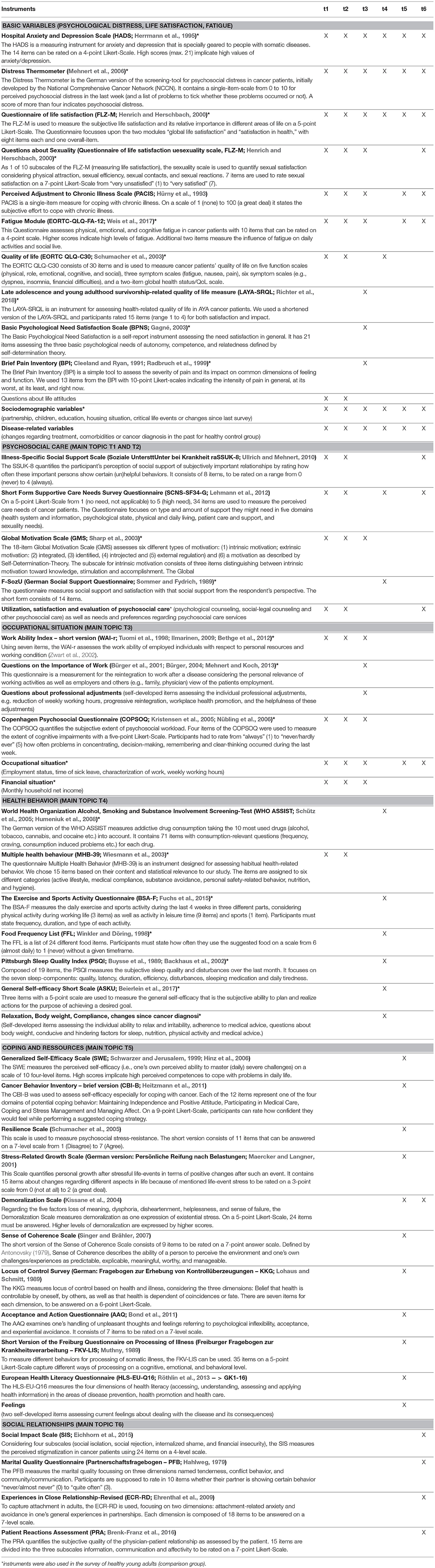

To keep the time required to fill out the study questionnaire reasonable, the survey was divided into two points in time with intervals of 12 months. The two exclusively cross-sectional study questionnaires each contain different topics (occupational situation, health behavior at the same time as the patient survey). The instruments used for the comparison group are marked with * in Table 1. The comparison sample was contacted by post once within 2 months (January to February 2018) in three waves. The second part of the survey of the comparison group was carried out 12 months later in January 2019. Within this survey, two postal reminders were sent out 3 and 6 weeks after the respective questionnaire was sent out.

To increase the participation rate, all of the study participants (AYA and comparison group) received a compensation fee of 10 Euros for completing the questionnaire at each measuring point.

Study Measures

The longitudinal survey included standardized questionnaires on psychological distress (HADS, distress thermometer), life satisfaction (questionnaire on life satisfaction) and fatigue (EORTC-QLQ FA-12) (which we already used from t1 to t6). The basis for the selection of these measurement instruments was their established use in psychooncology.

In addition, we used standardized questionnaires and self-developed items to assess cross-sectional topics like occupational situation (t3), health behavior (t4), coping resources (t5), and social relationships (t6). For this purpose, standard measurement instruments from the German-speaking world were selected, which, if possible, have already been used and tested in psycho-oncological studies.

All used instruments shown and described in Table 1.

Data Analyses

We use the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics) for all of the quantitative statistical data analyses. The data collected in this study will be described in terms of mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum. Frequencies of the primary outcomes psychological distress and QoL reported in combination with confidence intervals. Histograms and boxplots will be used for graphical representation.

The primarily exploratory evaluation of the AYA-LE-study includes questions on descriptive expressions, changes over time, influencing factors in the cross-section and longitudinally, and comparative analyses between AYA and the comparison group.

To compare the two groups with respect to a continuous outcome variable, t-tests (in case of normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney-U-tests (in case of non-existence of a normal distribution) are applied. To compare the two groups with respect to a categorical outcome variable, crosstabs with chi-square tests and (if necessary) generalized exact Fisher-tests are calculated. When comparing two measurement points, the t-test or the Wilcoxon test for paired samples, supplemented by crosstabs and possibly the Mc-Nemar test are performed. When comparing multiple measurement points, (co-)variance analyses for repeated measures are performed, or the Friedmann test if the normal distribution assumption is not given.

For multivariate analyses with metrically scaled outcome variables, multiple linear regressions are calculated or logistic regressions are used for binary target variables. The impact of age, gender, diagnosis groups and treatment are to be investigated. The analyses will be preceded by explorative variance analyses. If the identified influencing variables show different (inconsistent) effects for patients and the healthy control group, then additional moderation analyses will be performed to identify possible interaction effects (as moderator the group variable “AYA” vs. comparison group investigated).

Results

AYA Patients

At the first survey (t1), a total of 577 young cancer patients were included in the study. Recruitment details are outlined in the study protocol that was published in the previous study (Leuteritz et al., 2017). Of the 577 t1 participants, 35.7% (N=206) withdrew from the study by the time of the t5 survey. These drop outs consisted of deceased, active rejects, and unreached patients (Figure 1). Thus, at t5 371 complete datasets from t1 to t5 of the AYA patients exists. For t6, we also expect a response rate of approx. 90%.

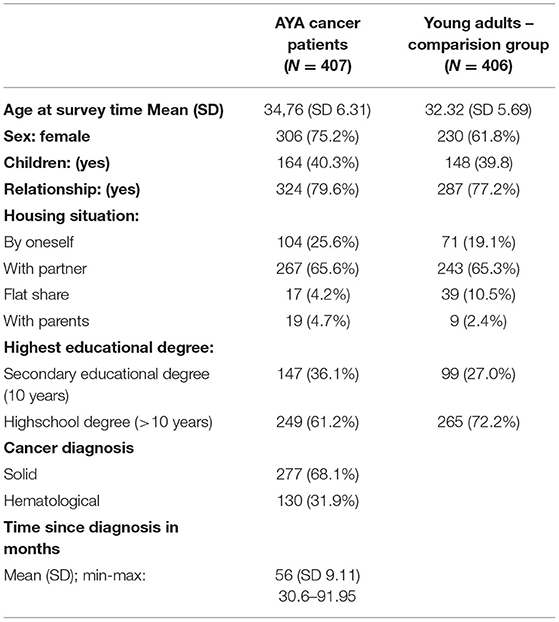

Comparison Group

Of the N = 1,598 Leipzig people who were contacted, n = 421 responded, of which n = 15 did not meet the inclusion criteria. N = 1,177 (74.4%) people did not answer or refused to be interviewed (non-responder). Thus n = 406 (25.5%) respondents were present in the first survey. Of these, n = 372 respondents also filled out the second survey with the focus on health behavior. The sociodemographic and medical characteristics of the samples are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. t4-Follow-up characteristics of the patient sample (AYA = 407) and the comparison group (CG = 406).

Discussion

The continuation of the existing AYA-LE study via several additional surveys illustrates the long-term consequences of cancer in young adulthood. A major strength of this study is the collection of longitudinal data of the outcome's quality of life, psychological distress, and fatigue over a very long period of time (at least 6 years). We expect at least 320 complete datasets to be available after the sixth survey, which will be completed in September 2021. To our knowledge, the existing AYA longitudinal studies (Krüger et al., 2009; Kwak et al., 2013; Zebrack et al., 2014) cover a significantly shorter period of time. Furthermore, a different cross-sectional thematic focus is examined at each measurement point. This creates comprehensive and differentiated findings of the life situation of young adults with cancer in Germany. In addition, the questioning of young adults without cancer in the continuation of the AYA-LE study will enable a comparison in psychological distress, quality of life, occupational situation and the health behavior between AYA patients and young adults without cancer.

The low dropout rate over the measurement points is to be emphasized. This can be attributed to the high interest of the patients, who wish to be addressed as a special patient group. To do justice to this wish, the sponsor of the study (German Cancer Aid) is producing the first guide for young adults with cancer in Germany with the support of our AYA research group. Through various strategies (e.g., Christmas and Easter greetings, and multiple reminders) we intend to create a high-rate of participation in the longitudinal study. The resulting large sample size allows different subgroup analyses.

In the first study period (t1, t2), approximately every second participant reported clinically increased anxiety, indicating a significant need for support. Critical life areas were financial and occupational situation as well as family planning and sexuality. Patients with a low net household income, another illness or without social support are particularly at risk of losing life satisfaction in the short and long term. There was a unmeet need with regard to psychological issues, the desire to have children and sexuality. At both times of the survey, the most frequent wishes were for general or psychological counseling, for age-appropriate sports activities and relaxation procedures, and for socio-legal/occupational counseling.

For the further results in the longitudinal study, we expect a stabilization of life satisfaction with a continuing high level of anxiety. With regard to the cross-sectional topics of occupational situation, health behavior, social relationship and coping resources, which have only been marginally investigated so far, we hope to gain a first detailed and differentiated insight in order to design appropriate intervention concepts.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Leipzig. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

This study's design and assessments were conceptualized and developed by KG, KL, and AM-T. The implementation and conduct of the study was coordinated by KG, KL, IS, MF, and HB. KG and KL wrote an outline of the paper, which was carefully revised, edited and discussed by AM-T, IS, HB, and MF. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the German Cancer Aid (Grant No: 70112752 and 70113932). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all our participants, without whom this longitudinal study would be impossible. Furthermore, we would like to thank our student research assistants for their important support in our study. Finally, we would like to thank our cooperating clinics and counseling centers. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and University of Leipzig within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Abbreviations

AYA, Adolescent and Young Adult; QoL, Quality of life; IBM SPSS Statistics.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, Stress and Coping: New Perspectives on Mental and Physical Well-Being. San Francisco, CA:Jossey-Bass.

AYA Oncology Progress Review Group. (2006). Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Available online at: http://www.cancer.gov/types/aya/research/ayao-august-2006.pdf (accessed September 9, 2021).

Backhaus, J., Junghanns, K., Broocks, A., Riemann, D., and Hohagen, F. (2002). Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, S737–740. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00330-6

Beierlein, C., Kemper, C. J., Kovaleva, A., and Rammstedt, B. (2017). Short scale for measuring general self-efficacy beliefs (ASKU). Methods Data Anal. (2013) 7:2. doi: 10.12758/mda.2013.014

Bethge, M., Radoschewski, F. M., and Gutenbrunner, C. (2012). The Work Ability Index as a screening tool to identify the need for rehabilitation: longitudinal findings from the Second German Sociomedical Panel of Employees. J. Rehabil. Med. 44, S980–987. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1063

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. C., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., et al. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire - II: a revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behav. Ther. 42:676–88. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

Brandstätter, J., and Lindenberger, U., (Hg). (2007). Entwicklungspsychologie der Lebensspanne. 2nd Edn. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Brenk-Franz, K., Hunold, G., Galassi, J. P., Tiesler, F., Herrmann, W., Freund, T., et al. (2016). Qualität der arzt-patienten-beziehung - evaluation der deutschen version des patient reactions assessment instruments (PRA-D). Z Allg Med, 92, 103–108. doi: 10.3238/zfa.2016.0103-0108

Bürger, W. (2004). Stufenweise Wiedereingliederung nach orthopädischer Rehabilitation – Teilnehmer, Durchführung, Wirksamkeit und Optimierungsbedarf. Die Rehabil. 43, S152–161. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-814985

Bürger, W., Dietsche, S., Morfeld, M., and Koch, U. (2001). Multiperspektivische Einschätzungen zur Wahrscheinlichkeit der Wiedereingliederung von Patienten ins Erwerbsleben nach orthopädischer Rehabilitation - Ergebnisse und prognostische Relevanz. Die Rehabil. 40, S217–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15992

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, S193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

Chan, A., Poon, E., Goh, W. L., Gan, Y., Tan, C. J., Yeo, K., et al. (2018). Assessment of psychological distress among Asian adolescents and young adults (AYA) cancer patients using the distress thermometer: a prospective, longitudinal study. Supp. Care Cancer. 26, S3257–3266. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4189-y

Cleeland, C. S., and Ryan, K. (1991). The brief pain inventory. Pain Res. Group. 143–147. doi: 10.1037/t04175-000

Ehrenthal, J. C., Dinger, U., Lamla, A., Funken, B., and Schauenburg, H. (2009). Evaluation of the German version of the attachment questionnaire “Experiences in Close Relationships–Revised” (ECR-RD). Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 59, 215–223. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067425

Eichhorn, S., Mehnert, A., and Stephan, M. (2015). Die deutsche Version der Social Impact Scale (SIS-D) - Pilottestung eines Instrumentes zur Messung des Stigmatisierungserlebens an einer Stichprobe von Krebspatienten. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol.65, 183–190. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398523

Fidler, M. M., Gupta, S., Soerjomataram, I., Ferlay, J., Steliarova-Foucher, E., and Bray, F. (2017). Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20-39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 18, S1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30677-0

Fuchs, R., Klaperski, S., Gerber, M., and Seelig, H. (2015). Messung der Bewegungs- und Sportaktivität mit dem BSA-Fragebogen. Zeitschrift Gesundheitspsychol. 23, S60–76. doi: 10.1026/0943-8149/a000137

Gagné, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motiv. Emot. 27, 199–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1025007614869

Gondos, A., Hiripi, E., Holleczek, B., Luttmann, S., Eberle, A., and Brenner, H. (2013). Survival among adolescents and young adults with cancer in Germany and the United States: an international comparison. Int. J. Cancer. 133, S2207–2215. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28231

Hahlweg, K. (1979). Konstruktion und Validierung des Partnerschaftsfragebogens PFB. Zeitschrift Klinische Psychol. 8, 17–40.

Heitzmann, C. A., Merluzzi, T. V., Jean-Pierre, P., Roscoe, J. A., Kirsh, K. L., and Passik, S. D. (2011). Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: Development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B). Psychooncology 20, 302–312. doi: 10.1002/pon.1735

Henrich, G., and Herschbach, P. (2000). Questions on life satisfaction (FLZM) - a short questionnaire for assessing subjective quality of life. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 16, 150–159. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.16.3.150

Herrmann, C., Buss, U., Snaith, R. (1995). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Deutsche Version (HADS-D). Manual.Bern: Hans Huber.

Hilgendorf, I., Borchmann, P., Engel, J., Heußner, P., Katalinic, A., Neubauer A., et al. (2016). Heranwachsende und junge Erwachsene: Onkopedia Leitlinien. Available online at: https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/heranwachsende-undjunge-erwachsene-aya-adolescents-and-young-adults/@@view/html/~index.html (accessed September 9, 2021).

Hinz, A., Schumacher, J., Albani, C., Schmid, G., and Brähler, E. (2006). Bevölkerungsrepräsentative normierung der skala zur allgemeinen selbstwirksamkeitserwartung. Diagnostica 52, S26–32. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924.52.1.26

Humeniuk, R., Ali, R., Babor, T. F., Farrell, M., Formigoni, M. L., Jittiwutikarn, J., et al. (2008). Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). Addiction (Abingdon, England) 103, S1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x

Hürny, C., Bernhard, J., Bacchi, M., Tomamichel, M., Spek, U., Coates, A., et al. (1993). The perceived adjustment to chronic illness scale (PACIS): a global indicator of coping for operable breast cancer patients in clinical trials. Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG). Support. Cancer. 1, 200–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00366447

Husson, O., Zebrack, B., Block, R., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Hayes-Lattin, B., and Cole, S. (2017a). Posttraumatic growth and well-being among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: a longitudinal study. Supp. Care Cancer. 25, S2881–2890. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3707-7

Husson, O., Zebrack, B. J., Block, R., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Hayes-Lattin, B., and Cole, S. (2017b). Health-related quality of life in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a longitudinal study. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, S652–659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7946

Ilmarinen, J. (2009). Work ability–a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 35, S1–5. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1304

Kissane, D. W., Wein, S., Love, A., Lee, X. Q., Kee, P. L., and Clarke, D. M. (2004). The Demoralization Scale: a report of its development and preliminary validation. J. Palliat. Care. 20, 269–276. doi: 10.1177/082585970402000402

Kristensen, T. S., Hannerz, H., Høgh, A., and Borg, V. (2005). The copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire–a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 31, S438–449. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.948

Krüger, A., Leibbrand, B., Barth, J., Berger, D., Lehmann, C., Koch, U., Mehnert, A. (2009). Verlauf der psychosozialen Belastung und gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualitat bei Patienten verschiedener Altersgruppen in der onkologischen Rehabilitation. Zeitschrift Psychosom. Med. Psychother. 55, S141–161. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2009.55.2.141

Kwak, M., Zebrack, B. J., Meeske, K. A., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Block, R., et al. (2013). Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a 1-year longitudinal study. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, S2160–2166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9222

Lehmann, C., Koch, U., and Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A. (2012). Psychometric properties of the German version of the short-form supportive care needs survey questionnaire (SCNS-SF34-G). Supp. Cancer. 20, 2415–24. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1351-1

Leuteritz, K., Friedrich, M., Nowe, E., Sender, A., Stöbel-Richter, Y., and Geue, K. (2017). Life situation and psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients - study protocol of a 12-month prospective longitudinal study. BMC Cancer 17:82. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3077-z

Lohaus, A., and Schmitt, G. M. (1989). Fragebogen zur Erhebung von Kontrollüberzeugungen zu Gesundheit und Krankheit. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Maercker, A., and Langner, R. (2001). Persönliche Reifung durch Belastungen und Traumata: Ein Vergleich zweier Fragebogen zur Erfassung selbstwahrgenommener Reifung nach traumatischen Erlebnissen. Diagnostica 47, 153–162. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.47.3.153

Mehnert, A., and Koch, U. (2013). Predictors of employment among cancer survivors after medical rehabilitation–a prospective study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 39, S76–87. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3291

Mehnert, A., Müller, D., Lehmann, C., and Koch, U. (2006). Die deutsche Version des NCCN Distress-Thermometers. Zeitschrift Psychiatr. Psychol. Psychother. 54, 213–223. doi: 10.1024/1661-4747.54.3.213

National Cancer Institute. (2019). Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Available online at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya (accessed September 9, 2021).

Nübling, M., Stößel, U., Hasselhorn, H.-M., Michaelis, M., and Hofmann, F. (2006). Measuring psychological stress and strain at work - Evaluation of the COPSOQ Questionnaire in Germany. Psycho-Soc. Med. 3:Doc05.

Oeffinger, K. C., Mertens, A. C., Sklar, C. A., Kawashima, T., Hudson, M. M., Meadows, A. T., et al. (2006). Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, S1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185

Quinn, G. P., Gonçalves, V., Sehovic, I., Bowman, M. L., and Reed, D. R. (2015). Quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 6, S19–51. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S51658

Rabin, C., Simpson, N., Morrow, K., and Pinto, B. (2011). Behavioral and psychosocial program needs of young adult cancer survivors. Qual. Health Res. 21, S796–806. doi: 10.1177/1049732310380060

Radbruch, L., Loick, G., Kiencke, P., Lindena, G., Sabatowski, R., Grond, S., and Cleeland, C. S. (1999). Validation of the German version of the Brief Pain Inventory. J. Pain Sympt. Manag. 18, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00064-0

Richter, D., Mehnert, A., Schepper, F., Leuteritz, K., Park, C., and Ernst, J. (2018). Validation of the German version of the late adolescence and young adulthood survivorship-related quality of life measure (LAYA-SRQL). Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 16, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0852-8

Röthlin, F., Pelikan, J. M., and Ganahl, K. (2013). Die Gesundheitskompetenz der 15-jährigen Jugendlichen in Österreich. Abschlussbericht der österreichischen Gesundheitskompetenz Jugendstudie im Auftrag des Hauptverbands der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger (HVSV).

Schumacher, J., Klaiberg, A., Brähler, E. (2003). Diagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und Wohlbefinden. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Schumacher, J., Leppert, K., Gunzelmann, T., Strauß, B., and Brähler, E. (2005). Die Resilienzskala - Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der psychischen Widerstandsfähigkeit als Personmerkmal. Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother, 53, 16–39.

Schütz, C. G., Daamen, M., and van Niekerk, C. (2005). Deutsche Übersetzung des WHO ASSIST Screening-Fragebogens. SUCHT 51, S265–271. doi: 10.1024/2005.05.02

Schwarzer, R., and Jerusalem, M. (1999). “Skalen zur erfassung von Lehrer-und schülermerkmalen.” in: Dokumentation der psychometrischen Verfahren im Rahmen der Wissenschaftlichen Begleitung des Modellversuchs Selbstwirksame Schulen, Vol. 23 (Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin).

Sharp, E., Pelletier, L. G., Blanchard, C., Levesque, C. (2003). “The global motivation scale: its validity and usefulness in predicting success and failure at self-regulation,” in Paper Presented at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (Los Angeles, CA).

Singer, S., and Brähler, E. (2007). Die Sense of Coherence Scale: Testhandbuch zur deutschen Version. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

Smith, A. W., Keegan, T., Hamilton, A., Lynch, C., Wu, X.-C., Schwartz, S. M., et al. (2019). Understanding care and outcomes in adolescents and young adult with Cancer: a review of the AYA HOPE study. Pediatric Blood Cancer 66:e27486. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27486

Smith, A. W., Seibel, N. L., Lewis, D. R., Albritton, K. H., Blair, D. F., Blanke, C. D., et al. (2016). Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: An update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer 122, S988–999. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29870

Sommer, G., and Fydrich, T. (1989). Soziale Unterstützung, Diagnostik, Konzepte, Fragebogen F-SozU. Tübingen: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verhaltenstherapie.

Tsangaris, E., Johnson, J., Taylor, R., Fern, L., Bryant-Lukosius, D., Barr, R., et al. (2014). Identifying the supportive care needs of adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer: a qualitative analysis and systematic literature review. Supp. Care Cancer. 22, S947–959. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2053-7

Tuomi, K., Ilmarinen, J., Jahkola, A., Katajarinne, L., Tulkki, A. (1998). Work Ability Index. 2nd Edn. Helsinki: Institute of Occupational Health (Occupational health care, 19).

Ullrich, A., and Mehnert, A. (2010). Psychometrische Evaluation and Validierung einer 8-Item Kurzversion der Skalen zur Sozialen Unterstützung bei Krankheit (SSUK) bei Krebspatienten. Klinische Diag. Eval. 3:81.

Warner, E. L., Kent, E. E., Trevino, K. M., Parsons, H. M., Zebrack, B. J., and Kirchhoff, A. C. (2016). Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer 122, S1029–1037. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29866

Weis, J., Tomaszewski, K. A., Hammerlid, E., Ignacio Arraras, J., Conroy, T. (2017). International psychometric validation of an EORTC quality of life module measuring cancer related fatigue (EORTC QLQ-FA12). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1:109. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw273

Wiesmann, U., Timm, A., Hannich, H. (2003). Multiples Gesundheitsverhalten und Vulnerabilität im Geschlechtervergleich. Zeitschrift Gesundheitspsychol. 11:4. doi: 10.1026//0943-8149.11.4.153

Winkler, G., and Döring, A. (1998). Validation of a short qualitative food frequency list used in several German large scale surveys. Zeitschrift Ernahrungswiss. 37, S234–241. doi: 10.1007/PL00007377

Zebrack, B., and Isaacson, S. (2012). Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, S1221–1226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5467

Zebrack, B. J., Corbett, V., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Meeske, K. A., Hayes-Lattin, B., et al. (2014). Psychological distress and unsatisfied need for psychosocial support in adolescent and young adult cancer patients during the first year following diagnosis. Psycho-oncology 23, S1267–1275. doi: 10.1002/pon.3533

Keywords: adolescent and young adult (AYA), cancer, psychological distress, quality of life, life situation

Citation: Geue K, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A, Stroske I, Brock H, Friedrich M and Leuteritz K (2021) Psychosocial Long-Term Effects of Young Adult Cancer Survivors: Study Protocol of the Longitudinal AYA-LE Long-Term Effects Study. Front. Psychol. 12:688142. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.688142

Received: 30 March 2021; Accepted: 30 August 2021;

Published: 29 September 2021.

Edited by:

Chiara Acquati, University of Houston, United StatesReviewed by:

Olga Husson, Netherlands Cancer Institute, NetherlandsCaterina Calderon, University of Barcelona, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Geue, Mehnert-Theuerkauf, Stroske, Brock, Friedrich and Leuteritz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristina Geue, a3Jpc3RpbmEuZ2V1ZUBtZWRpemluLnVuaS1sZWlwemlnLmRl

Kristina Geue

Kristina Geue Anja Mehnert-Theuerkauf

Anja Mehnert-Theuerkauf Isabelle Stroske

Isabelle Stroske Hannah Brock

Hannah Brock Michael Friedrich

Michael Friedrich Katja Leuteritz

Katja Leuteritz