94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 07 June 2021

Sec. Quantitative Psychology and Measurement

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651071

An increasing number of studies focus on the phenomenon of objectification in the workplace. This phenomenon reflects a process of subjection of the employee, where he is considered as an object, a mean (utilitarian) or reduced to one of his attributes. Previous studies have shown that objectification can have consequences on the workplace health or performance. Field studies are based on objectification measures based on tools whose psychometric qualities are unclear. Based on a previous workplace objectification measurement scale, we conducted a study with the aim of devising a new parsimonious scale. We present three studies which aim to validate this new scale. In the first study, an EFA and a CFA were performed in order to construct a scale and verify its structure validity. We obtained a 10-item scale reporting two factors labeled “Instrumental value” and “Powerfulness.” The psychometric qualities of this scale were satisfactory, i.e., showed good internal reliability and good structural validity. In a second study, we tested the convergent and divergent validity of the scale. We observe that POWS is adequately correlated with dehumanization indicators. Finally, in a third study, we found that only powerfulness was associated with negative consequences for occupational health. This suggests that objectification is a process of social perception that contributes either to the devaluation of social agents in the workplace or to normal functioning at work.

Objectification is a form of dehumanization (Haslam, 2006; Volpato and Andrighetto, 2015) which is expressed through a relationship of subjugation or a reductive perception of a person based on one of their attributes (Nussbaum, 1995). It occurs when the person is viewed as an object. In this context, over and above the denial of their humanity, i.e., passivity, denial of subjectivity and denial of autonomy, the person is viewed through their use, i.e., instrumentalization, possession or interchangeability, or their form, i.e., reduction to appearance, body or silence (Langton, 2011). In the workplace, objectification consists in behaving with an employee as if the latter had no thoughts or emotions, as if they had to be controlled in order to act, deprived of initiative, exploitable and malleable at will. Regarding reduction to form, persons are viewed solely through their appearance or their body, and are not listened to, as they are judged incapable of expressing their feelings about their work or themselves.

We find similar patterns of behavior evoking sexual objectification. At the same time, all these behaviors have in common to rely on elementary perceptual processes (Bernard et al., 2018). We present a series of studies which aim to clarify the measurement of objectification in workplace. We started from a scale measuring the usual behaviors of objectification in workplace (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a) and we developed a new scale based on the perception of employees in workplace.

Several explanatory hypotheses have been put forward to account for objectification. Objectification is thought to be a means of reducing complexity, of coping with uncertainty, and consequently of facilitating interaction by enabling others to be perceived via simple attributes. Landau et al. (2012) highlight the fact that managers, who anticipate difficulties in carrying out their duties and in considering the subjectivity of their employees, focus on their professional attributes (skills for example). A similar explanation can be found in the medical field where objectification is described as a defense mechanism which is established when faced with the difficulty of delivering care effectively, for example when care involves hurting the patient (Timmermans and Almeling, 2009; Haque and Waytz, 2012).

Other authors consider that objectification is associated with the exercise of power. Gruenfeld et al. (2008) observed through several experiments that the exercise of power leads to the objectification of others, that’s to say perceiving them through the sole dimension of their use in achieving goals which are set by the person who holds the power. Other field studies (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a) have highlighted the fact that working in an organization based on strict respect for authority, rationality of procedures, division of work and written formal communication is associated with self-objectification. Moreover, the link between power and objectification is conditioned by the interpersonal attitude of leaders (Sanders et al., 2015) and more generally by the quality of interpersonal relationships (Renger et al., 2016). Beyond power, we can emphasize that scientific discourse on management is underpinned by a vision of the employee as a resource for the organization and not as an end in themselves (Cheney and Carroll, 1997; Shields and Grant, 2010; Rochford et al., 2016).

Following on from the analyses of the thinker Marx (1944), the sociologist Durkheim (1893) and the psychoanalyst Fromm (1956), objectification can be considered as a corollary of the organization of work activity. Haque and Waytz (2012) situate the origin of medical dehumanization at the level of care activity. This highlights the fact that medical care promotes deindividuation (anonymity of the uniform, no name), the perception of the patient as diminished (illness), dissimilarity (caring/neat status, sick/healthy) or labeling (denomination by the disease). Other authors emphasize the impact of labor robotization (Moore and Robinson, 2016) or the characteristics of employees, such as their age (Wiener et al., 2014). Several experimental studies (Andrighetto et al., 2017, 2018; Baldissarri et al., 2017b) have highlighted the fact that objectification takes place when observing someone working in an activity which is continually reproduced (repetitiveness), which is divided into several basic units carried out separately (fragmentation) and whose pace of execution and planning depends on another person or a technical system rather than on the employee themselves (external control). This process occurs if the activity takes place in an industrial context (machine based) rather than a craft-based context (the manufacture of a specific object) and does not exclusively concern the perception of others. So Baldissarri et al. (2017a) highlighted the fact that being placed in a situation of performing an activity which is repetitive, fragmented or under the control of someone else leads to a perception of oneself as self-objectified/dementalized, like an instrument (a tool, a thing, or a machine), and as having little personal freedom, another attribute specifically associated with human beings. The latter element is important as this study by Baldissarri and al. also underlines the fact that seeing oneself as generally having little personal freedom reinforces the phenomenon of self-objectification. There is therefore a downward spiral in which the feeling of loss of freedom may lead to perceiving oneself as an object, this state in turn reducing the feeling of freedom, etc.

When considering the consequences of objectification in the field of work, it can be seen that this type of relationship is associated with “cognitive deconstructive” states (Christoff, 2014), with a loss of perceived humanity (Loughnan et al., 2017), occupational burnout (Baldissarri et al., 2014; Szymanski and Mikorski, 2016; Caesens et al., 2017), decrease of job satisfaction and depression (Szymanski and Feltman, 2015), sexual harassment (Wiener et al., 2013; Gervais et al., 2016), and self-objectification (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a). Self-objectification constitutes dementalization, i.e., a feeling of having lost the capacity to act, to plan, to exercise control over oneself or one’s environment, or to feel emotions (Gray et al., 2011).

Some studies have also considered the positive consequences, such as personal empowerment (Inesi et al., 2014) or employability (Rollero and Tartaglia, 2013; Nistor and Stanciu, 2017). In the medical field, objectification is also conceived as a means of facilitating medical care (Haque and Waytz, 2012). In these cases, objectification is considered to be a provider of psychosocial resources or to facilitate activity at work.

There is therefore still much research to be done to understand both the antecedents and outcomes of objectification. This work requires the use of valid and simple tools to study the phenomenon of objectification at work.

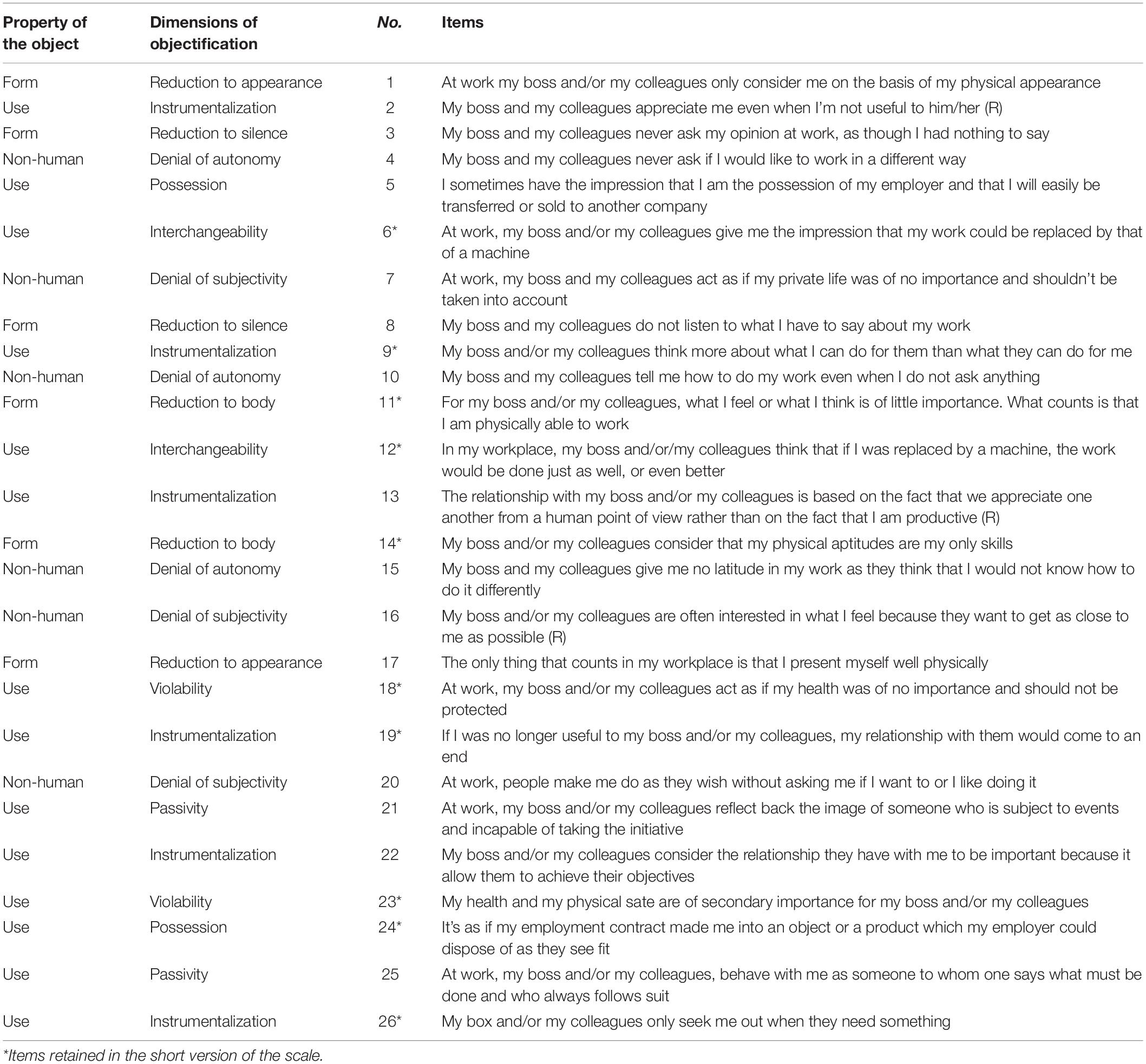

In this study, we aim to construct a scale of objectification in the workplace. We have taken as a basis the perception of being objectified scale created by Auzoult and Personnaz (2016a) which adopts and extends the adaptation of the scale of Gruenfeld et al. (2008) and Baldissarri et al. (2014). In the original scale, we only took into account the instrumentalization that is thought to be the core defining component of objectification. In relation to the work of Nussbaum (1995) and Langton (2011), Auzoult and Personnaz have developed a scale that also takes into account the processes associated to objectification: denial of agentivity, usefulness or his/her apparent characteristics (Figure 1 and Table 1). According to this scale, objectification at work means that the employee acts according to the objectives of a third party and is considered incapable of taking initiatives or decisions. In the same way his/her affects, his/her health and his/her ideas are disregarded and he/she is considered solely from the point of view of his/her appearance. Finally, he/she would be considered as interchangeable with others or with a machine, because he/she belongs to his/her organization. In this way of thinking, the employee is a resource just like raw material or capital (Shields and Grant, 2010; Moore and Robinson, 2016).

Table 1. List of Auzoult and Personnar scale items with their associated dimensions: Instumentalization, passivity, possession, violability, interchangeability, reduction to silence, reduction in appearance, reduction to body, denial of subjectivity, and denial of autonomy.

This scale has been used in several studies (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a,b; Auzoult, 2019). It seems to benefit from good internal consistency (Cronbach α from 0.90 to 0.91). However, the factor structure that is presented in the original study reveals the existence of five factors while theoretically 10 dimensions were expected (e.g., instrumentalization, passivity, etc., see Figure 1 and Table 1). The authors (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a) considered that the correlations observed between the items justified the existence of a single factor of objectification at work. This leads us to consider the scale as relatively complex. Similarly, the scale contains 26 items which can penalize field research aimed at populations uncomfortable with writing. These different findings led us to withdraw the 26 items of the original scale and to collect a sufficient number of answers to carry out a new validation study of the scale.

The first study consisted in developing an abbreviated version of the objectification perception scale. First, we evaluated the psychometric properties of the original perception of objectification scale. The scale includes 26 items (Table 1) which measure the 10 theoretical dimensions of objectification: instrumentalization, reduction in appearance, denial of autonomy, denial of subjectivity, passivity, interchangeability, violability, possession, and reduction to body and reduction to silence. Respondents used seven-point scales ranging from “not at all” (1) to “quite” (7). Secondly, if the confirmatory analysis of the previous scale did not fit the data, an exploratory analysis was conducted to refine this. A new confirmatory analysis on a replication sample was performed to test the new version.

EFA and CFA were carried out using the R software by the following packages: Psych (Revelle, 2015), Lavaan (Rosseel, 2012). The parallel analysis allowed us to determine the number of factors to be extracted. We have selected factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1, according to Kaiser’s criteria. The items were deleted if their unique variance was <0.60, their saturation coefficient >0.60 and their double load <0.10 on a second factor. THE EFA extraction method was maximum likelihood and oblimin rotation. For confirmatory analysis, our models were estimated using the following statistical indices: the chi-square and degree of freedom (CMIN/DF), the comparative fit index (CFI), the tucker-lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A good model with a CMIN/DF < 3, has a CFI, GFI and TLI value >0.90 and RMSEA values below 0.08. To evaluate the reliability of the scale, we used cronbach’s alpha which must be >0.7

780 participants (385 males and 395 females) participated in the study. Their average age was 38. Regarding their level of education, 48.9% of them had a level of education lower than the bachelor’s degree, 22.6% a bachelor’s degree, and 28.4% a level higher than the bachelor’s degree. Regarding their status, 72.4% of them were non-managerial, 19.3% were executive and 8.2% were senior managers. 84.9% worked in a service activity and 21.5% in industry. The work objective scale was sent via mailing lists to employees working in various sectors of activity. Respondents were contacted via the researchers’ networks and then asked to extend the study via their own networks (snowball technique).

The questionnaire allowed us to measure the study variable and participants’ characteristics. The answers were anonymous. Respondents received a report on the study’s main results by email. Four participants that had not fully completed the questionnaire, were withdrawn from the study.

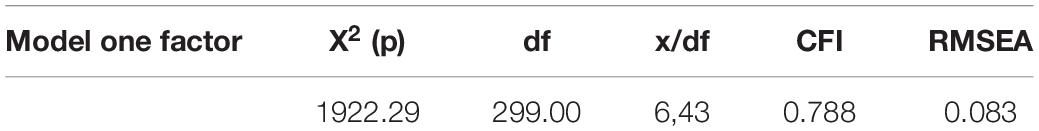

The Table 2 summarizes the CFA indices from the scale of the perception of objectification in the workplace (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a) to a one-factor. The CMIN/DF must be less than 3, but the index indicates that it is 6.43. The RMSEA is 0.083, it can be considered satisfactory, as it must be less than or equal to 0.08. Nevertheless, the CFI is less than 0.09 which is not satisfactory. The 1-dimensional objectification perception scale can be considered inadequate with regard to the indicators presented.

Table 2. Fit indices for de confirmatory analyses of the Perception of objectification on the workplace (Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016a) (N = 780).

To refine the scale and improve the exploratory analysis, we split the sample in two. The participants were randomly numbered so that the first sample contains even numbers and the second contains odd numbers. The first sample (n = 390) will be used for the exploratory analysis, the second sample (n = 390) will be used for the confirmatory analysis.

The factor extraction analysis proposed a two-factor model (Figure 2). The first factor explains 23% of the variance and has an eigenvalue of 6.06. The factor 2 has an eigenvalue of 3.53 and explains 14% of the variance. The Table 3 shows the factors loading of the 10 items selected from the initial scale.

The first factor consisted of 7 items (26, 24, 23, 19, 18, 14, and 9). These represented instrumentalization (26, 19, and 9), possession (24), violability (23 and 18), and reduction to body (14). The saturation coefficients of this factor were between 0.67 and 0.72. The second factor consisted of 3 items (12, 11, and 6). The items represented interchangeability (6 and 12), and reduction to body (11). The saturation coefficients for this factor were between 0.60 and 0.73. The first factor included items that referred to the utility and/or importance of the employee for others: we labeled this factor ‘‘Instrumental value1.’’ The second factor grouped items that referred to the power of the employee, whether physically assessed or compared to that of machines: we labeled this factor ‘‘Powerfulness2.” For a 2-factor model, the KMO index is 0.90, Bartlett’s test is less than 0.05 which can be considered excellent.

The confirmatory analysis was performed on the second sample to analyze the fit of the 2-factor model in 10 items. The indices of the 2-factor model were compared to a 1 factor model. The Table 4 shows that the 2-factor model requires better adjustment indices. Referring to the threshold of the recommended values, the analysis showed that the CMIN/DF was satisfactory because it was less than 3 (χ2 = 77.599, DF = 34, CMIN/DF = 2.28). The CFI was also satisfactory because it was higher than 0.9 (CFI = 0.973) as was the GFI (GFI = 0.963). RMSEA was of good quality because it was less than 0.08 (RMSEA = 0.041). Finally, the RMR was less than 1 (RMR = 0.041). Compared to 1-factor model, the 2-factor model indicates a better adequacy of the indices. Then, the internal reliability of our model (Figure 3) showed us that the correlations of the intra-factor items were all greater than 0.60 with their latent factor. The inter-factor correlation was equal to 0.50. Finally, the internal consistency index of the various factors, expressed by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, showed us that factor 1 had an alpha of 0.80 and factor 2 had an alpha of 0.70.

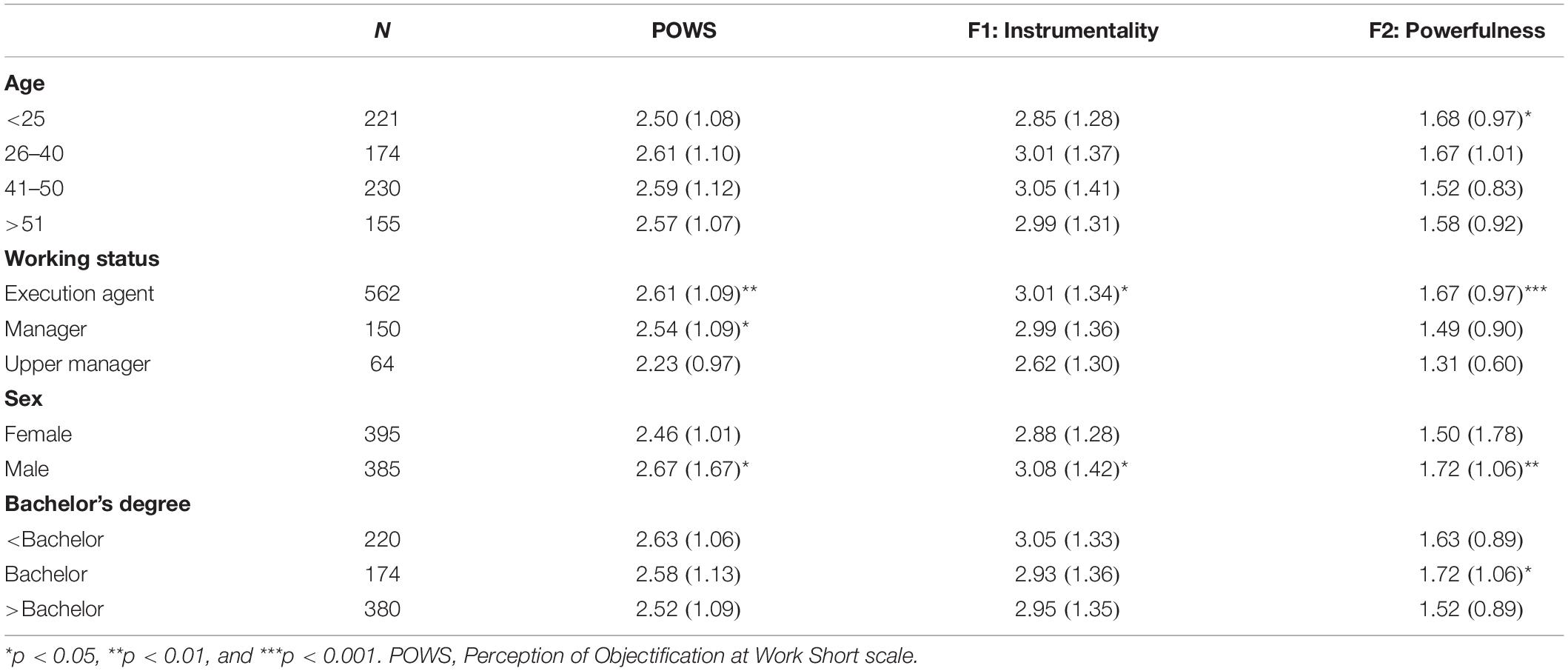

Comparison of means across subjects (Table 5) shows that enforcement agents and managers have a higher score of perceived objectification at workplace than upper managers (execution agent: t = 2.95, df = 82.50, p < 0.005; manager: t = 2.07, df = 132.18, p < 0.05). For gender, males have a significantly higher score than females (t = 2.68, df = 757.26, p < 0.05). Regarding age, we do not observe any difference in POWS scores between the different age groups, however the under 25s have a higher score of the powerfulness factor than the 41/50s (t = 1.91, df = 430.16, p < 0.05). Finally, concerning the level of study, we only observe a difference in average between bachelor’s degree levels and postgraduate education, the first having a higher average in the powerfulness factor (t = 2.51, df = 288.3, p < 0.05).

Table 5. Mean (standard deviation) for POWS score depending on age, sex, working status, and degree of study (N = 780).

The objective of this first study was to construct a parsimonious objectification at the workplace level with an unambiguous factor structure. We took as a basis for our work the scale constructed by Auzoult and Personnaz (2016a), which initially included 26 items measuring an alleged general objectification factor.

First, we conducted a confirmatory analysis of the model to ensure its psychometric properties. The indices showed us that the 1-factor model was not adequate. An exploratory and confirmatory analysis led us to choose a 10-item two-factor structure. This two-factor structure does not contradict the idea that objectification is a unitary phenomenon since these two factors are strongly intercorrelated. As regards criteria validity, the mean comparison of our sample shows us elements in line with the literature. Indeed, we observe that the executing agents have a higher mean of objectification than the upper managers. This result supports the very definition of objectification, which stems from a fragmented, repetitive activity but also from a power relationship in which subordinates are treated exclusively on their usefulness in achieving a goal (Magee and Galinsky, 2008).

The structural validity of this new scale is satisfactory. The following two studies aim to establish the convergent and divergent validity of the scale by taking into account other psychological constructs supposed to be associated with objectification at work.

To verify the convergent and divergent validity of our scale, we have compared the POWS scale to the following elements: the dehumanization and humanization scales. We postulated that the correlations would be significantly positive between the POWS scale and the dehumanization scale (convergent validity) and the correlations would be significantly negative between the POWS scale and the humanization (divergence validity). We expect these relationships which have already been observed by Auzoult (2019). Indeed, the fact of perceiving oneself as objectified by one’s professional entourage is positively associated with a perception of oneself as an instrument (i.e., mechanical dehumanization) and negatively associated with the perception of oneself as a person (i.e., humanization).

74 participants participated in our study (12 men and 61 women). The average age is 37. As regards professional status, we have 23% of executive agents, 43% of middle managers, 11% of upper managers, 12% of artisans and 11% of students. We distributed our questionnaire on social networks, specifying that the answers were anonymous. The contact procedure was similar to the previous study.

The perception of objectification was measured with the previously validated 10-item POWS scale with an internal consistency index of 0.92.

A 2-dimensional scale of instrumentality and humanness that measures the perception of being seen as an instrument (mechanical dehumanization) or a human being (humanization) (Andrighetto et al., 2017). Five words are presented to describe oneself as a human person (human being, individual, and person) and five words to describe oneself as an instrument (tool, thing, machine). The first factor (mechanical dehumanization) has an internal consistency index of 0.90 and the second factor (humanization) has an internal consistency index of 0.77. Participants respond using a likert scale ranging from 1 «not at all” to 7 “quite.”

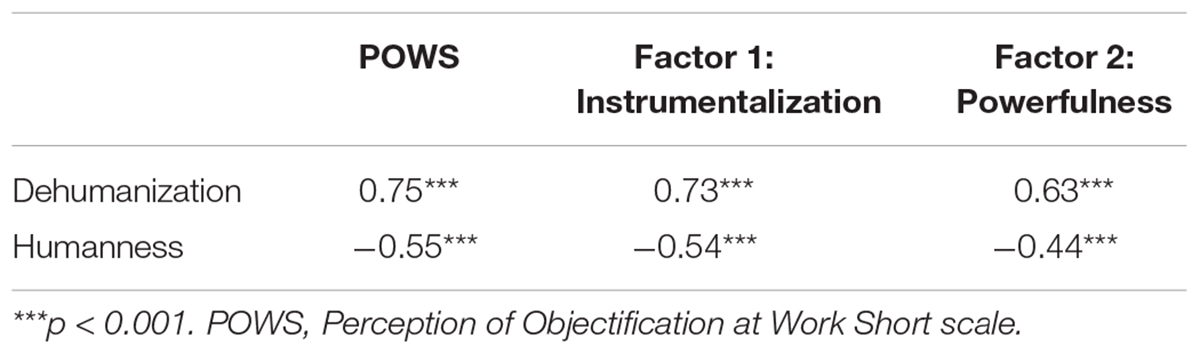

The Table 6 shows the correlations between objectification (POWS scale), the 2 subjacent dimensions, mechanical dehumanization and humanization. Objectification (POWS scale) is positively associated to mechanical dehumanization (r = 0.75) and negatively associated to the humanization (r = −0.55). The two sub−dimensions of the POWS scale are also positively associated to the mechanical dehumanization (Instrumentality: r = 0.73; Powerfulness: r = 0.63) and negatively associated to humanness (Instrumentality: r = −0.54; Powerfulness: r = −0.44). These results confirm a satisfactory convergent and divergent validity of our scale.

Table 6. Correlations between perception of objectification at work (POWS scale), dehumanization, and humanization (N = 74).

The objective of this second study was to establish the convergent and divergent validity of our new scale. These are satisfactory, however, in view of our sample (N = 74), comparisons in other larger samples with the same measures of similar constructs will be included in further studies.

Concerning the two subdimension of the POWS scale, we have labeled these two factors “Instrumental value” and “Powerfulness.” The first factor refers to a feeling of being reduced to a mere support or physical object (like a tool) and thus being represented in a work environment more as tool than a social agent. Thus, the agent feels as if he/she is being utilized and valuated in his/her working environment. The second factor refers to the feeling of not being recognized as an agent in the working environment. Thus, the agent thinks that recognition comes solely from their actions. This leads us to two observations. On the one hand, objectification refers to a representation of people which reflects the process of dehumanization where the employee perceives himself/herself as a resource at the service of others or to a process of comparative devaluation of the employee in his or her technical universe. These two representations of objectification are not strictly similar. Indeed, the fact of perceiving oneself as a resource at the service of the organization can be considered relatively usual since the employment contract reflects this organizational objective. If employees adhere to organizational goals, this phenomenon of reducing the person to a means may even be considered functional and acceptable (Orehek and Weaverling, 2017). In some cases, it can even be conceived that objectification can lead to an increase in the market value of the employee (Rollero and Tartaglia, 2013) or an increase in the feeling of self-efficacy (Nistor and Stanciu, 2017). On the contrary, perceiving oneself as having less power than a machine represents an attack on the instrumental value of the worker. From this point of view, the consequences of objectification for health are not necessarily unambiguous depending on whether we consider the two factors that make up our scale.

This observation led us to question one of the observations made about the consequences of the objective for health. Specifically, one of the consequences of objectification is self-objectification. Self-objectification is thought to take place through dementalization, which is to say, a perception of the self as being incapable of feeling or thinking about work. In studies in which objectification and mentalization are measured, there is a relatively weak relationship (<0.30) (Baldissarri et al., 2014; Auzoult and Personnaz, 2016b) or an absence of a relationship between these two psychological constructs (Auzoult, 2019). We think that this difficulty in observing a strong and consistent relationship is due to the fact that the different dimensions of objectification, “Instrumental value,” and “Powerfulness” are not equivalent from the point of view of the consequences for health, here dementalization at work. Specifically, we think that only the “Powerfulness” dimension of objectification is systematically negatively associated at the level of mentalization, which results in self-objectification at work. The aim of this third study was to test this hypothesis using the reduced scale (POWS) and self-objectification at work.

A total of 650 participants (307 females, 343 males) participated in the study. They were on average 38 years old. Regarding education level, 31% had a level of education lower than the bachelor’s degree, 43% a bachelor’s degree and 25% a level higher than the bachelor’s degree. Regarding status, 69% of them were executive, 21% were middle managers and 9% were senior managers.

Participants were invited to complete an online questionnaire. The questionnaire allowed us to measure the study variables. The answers were anonymous and once data were completed and results processed, respondents received a report of the study’s main results by email.

Objectification was measured using the short scale POWS developed in the previous study. It consisted of 10 items and participants responded using 7-point scales ranging from “not at all” (1) to “quite” (7). This scale is composed of 2 factors: “Instrumental value” with an internal consistency index of 0.87 and “Powerfulness,” with an internal consistency index of 0.73.

Self-objectification was measured using the Self-Mental State Attribution Task (Baldissarri et al., 2014). The scale is based on 19 items, with an internal consistency index of 0.89, allowing the attribution of different mental states during a working day (for example: “To what extent have you been likely to feel psychological states during a working day?: feel a need; have an intention; reasoning”). Participants responded using seven-point scales ranging from “not at all” (1) to “quite” (7).

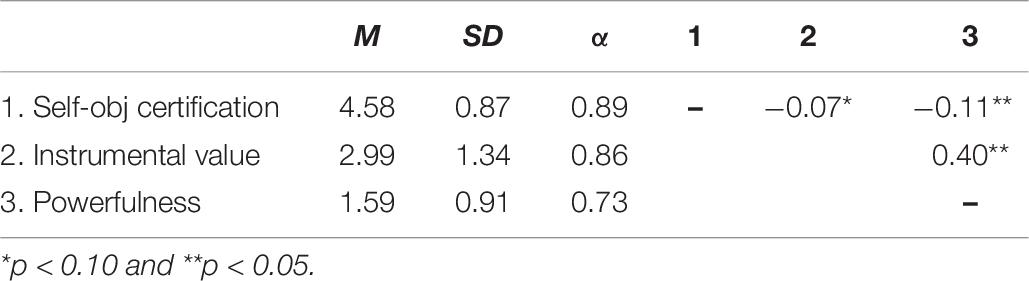

The two indicators of objectification were positively associated (r = 0.40). Self-objectification was significantly negatively associated with powerfulness (r = −0.11) and tendentially with instrumental value (r = −0.07) (Table 7). We conducted a regression analysis considering self-objectification as a dependent variable and the two dimensions of objectification as independent variables. Powerfulness (β = −0.09) explained self-objectification (Table 8). Our hypothesis was confirmed.

Table 7. Correlations between variables: self-objectification, instrumental value, and powerfulness (N = 650).

In this third study the objectification was measured using the reduced scale. We measured dementalization at work as a consequence of objectification. It was observed, as expected, that only the second factor named powerfulness was systematically associated with self-objectification (dementalization), that is to say with negative consequences for occupational health. This result confirms that it is not the fact of perceiving oneself as a means of serving others that is problematic for occupational health. It appears that it is the fact of perceiving oneself as comparable to an instrument or a machine that is deleterious to health at work. From this point of view, self-objectification appears as the result of a comparative devaluation of social agents in their technical universe. However, a single study is not a sufficient basis to draw a conclusion, further studies are needed to confirm this first result.

The two factors involved in the measurement of objectification refer to the value of the employee in reference to the action he/she can perform for others, but also to his/her lack of value that reflects the lack of importance of his/her health or replaceability by machines. Work on social perception leads to the idea that common sense knowledge is evaluative and utilitarian in the sense that it does not aim for accuracy but for action (Funder, 1987). The process of objectification thus appears as the product of an action-oriented evaluative activity, that is to say endowed with functionality as has been previously emphasized (Haque and Waytz, 2012). According to “economy of action” (e.g., Proffitt, 2006), individuals perceive their environment through its opportunity for action and its associated cost. In this process, individuals integrate each source (i.e., physical or social) reducing the cost of their action depending on the nature of the task (e.g., Meagher and Marsh, 2014; Osiurak et al., 2014). This is probably why objectification occurs in contexts where control of action is salient (power, relational uncertainty) and where production through activity is based on the coordination of the human and the technical.

The objectification process refers to a perceptive activity in which the person is encoded through his/her form (structural dimension) but also and above all through his/her functional properties (semantic dimension) that is to say in accordance with the same processes as the perceptive activity of objects (Humphreys et al., 1997; Martin, 2007). Numerous studies have suggested that people think about objects in much the same way as they think about people (Lakey and Orehek, 2011; Orehek and Forest, 2016). When action is concerned, people are used in the same way as objects and are evaluated according to their instrumental usefulness for achieving others’ goals (Orehek and Weaverling, 2017). Objectification in the workplace therefore involves a process of social perception that accounts for basic perceptual mechanisms. We thus find a frame of reference similar to the process of sexual objectification (Bernard et al., 2018). From this point of view, the scale that we have developed takes a closer look at the phenomenon of objectification at work, which can then be considered as a process of social perception in the work context. This also leads to the dissociation of the objectification process from its immediate consequences, i.e., instrumentalization, violability, interchangeability, denial of agency, and so on.

The purpose of this study was to construct a short scale for objectification in the workplace. At the end of this validation study we obtained a scale of 10 items with a bifactorial structure whose psychometric qualities are very satisfactory. From the point of view of content, this scale seems to comprehend the process of objectification as a process of social perception. In future studies, therefore, it would be better to dissociate the objectification process from its consequences in terms of social behavior at work. Likewise, the fact that objectification accounts for the value of people in their work context leads to an interesting question that we need to address experimentally: is objectification a loss of social value or an absence of social attribution?

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

LC, LB, and LA participated in the design of the study and analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. LC conducted the experiment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the EPSYLON laboratory (Montpellier 3) and LB, for the open access publication costs.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank all the participants for their time and willingness to participate.

Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., and Volpato, C. (2017). (Still) Modern times: objectification at work. European Journal of Social Psychology 47, 25–35. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2190

Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., Gabbiadini, A., Sacino, A., Valtorta, R. R., and Volpato, C. (2018). Objectified conformity: Working self-objectification increases conforming behavior. Social Influence 13, 78–90. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2018.1439769

Auzoult, L. (2019). Can meaning at work guard against the consequences of objectification? Psychological Reports doi: 10.1177/0033294119826891 ∗vpq,

Auzoult, L., and Personnaz, B. (2016a). The role of organizational culture and self-consciousness in self-objectification in the workplace. TPM – Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology 23, 271–284.

Auzoult, L., and Personnaz, B. (2016b). Les relations de travail sont-elles un moyen de faire face à l’objectification? [Are working relationships a way to deal with objectification ?]. Lyon: IXème Congrès de l’Association Francophone de Psychologie de la Santé. 14-16 décembre 2016∗.

Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., Gabbiadini, A., and Volpato, C. (2017a). Work and freedom? Working self-objectification and belief in personal free will. British Journal of Social Psychology 56, 250–269. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12172

Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., and Volpato, C. (2014). When work does not ennoble man: Psychological consequences of working objectification. TPM - Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology 21, 327–339.

Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., and Volpato, C. (2017b). Workers as objects: the nature of working objectification and the role of perceived alienation. TPM – Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology 24, 1–14. doi: 10.4473/TPM24.2

Bernard, P., Gervais, S. J., and Klein, O. (2018). Objectifying objectification: When and why people are cognitively reduced to their parts akin to objects. European Review of Social Psychology 29, 82–121. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2018.1471949

Caesens, G., Stinglhamber, F., Demoulin, S., and De Wilde, M. (2017). Perceived organizational support and employees’ well-being: the mediating role of organizational dehumanization. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 26, 527–540. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2017.1319817

Christoff, K. (2014). Dehumanization in organizational settings: some scientific and ethical considerations. Frontiers in human neuroscience 8:748. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00748

Cheney, G., and Carroll, C. (1997). The person as object in discourses in and around organizations. Communication Research 24, 593–630. doi: 10.1177/0093650297024006002

Durkheim, E. (1893). De la division du travail social [The Division of Social Work]. Paris: Felix Alcan.

Funder, D. C. (1987). Errors and mistakes: evaluating the accuracy of social judgment. Psychological Bulletin 101, 75–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.75

Gervais, S. J., Wiener, R. L., Allen, J., Farnum, K. S., and Kimble, K. (2016). Do you see what I see? The consequences of objectification in work settings for experiencers and third party predictors. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 16, 143–174. doi: 10.1111/asap.12118

Gray, K., Knobe, J., Sheskin, M., Bloom, P., and Barrett, L. F. (2011). More than a body: Mind perception and the surprising nature of objectification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101, 1207–1220. doi: 10.1037/a0025883

Gruenfeld, D. H., Inesi, M. E., Magee, J. C., and Galinski, A. D. (2008). Power and the Objectification of Social Targets. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 95, 111–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.111

Haque, O. S., and Waytz, A. (2012). Dehumanization in medicine: causes, solutions, and functions. Perspectives on Psychological Science 7, 176–186. doi: 10.1177/1745691611429706

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review 10, 252–264. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

Humphreys, G. W., Riddoch, M. J., and Price, C. J. (1997). Top-down processes in object identification: evidence from experimental psychology, neuropsychology and functional anatomy. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal society of London. 352, 1275–1282. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0110

Inesi, M. E., Lee, S. Y., and Rios, K. (2014). Objects of desire: Subordinate ingratiation triggers self-objectification among powerful. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 53, 19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.01.010

Landau, M. J., Sullivan, D., Keefer, L. A., Rothschild, Z. K., and Osman, M. R. (2012). Subjectivity uncertainty theory of objectification: Compensating for uncertainty about how to positively relate to others by downplaying their subjective attributes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48, 1234–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.05.003

Langton, R. (2011). Sexual solipsism: Philosophical essays on pornography and objectification. European Journal of Philosophy 19, 327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0378.2011.00478.x

Lakey, B., and Orehek, E. (2011). Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review 118, 482–495. doi: 10.1037/a0023477

Loughnan, S., Baldissarri, C., Spaccatini, F., and Elder, L. (2017). Internalizing objectification: Objectified individuals see themselves as less warm, competent, moral, and human. British Journal of Social Psychology 56, 217–232. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12188

Magee, J. C., and Galinsky, A. D. (2008). 8 social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management annals, 2, 351–398. doi: 10.1080/19416520802211628

Martin, A. (2007). The representation of object concepts in the brain. Annual Review of Psychology 58, 25–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190143

Marx, K. (1944). “The economic and philosophical manuscripts of 1844,” in The marx/engels reader, ed. R. Tucker (New York, NY: Norton & Company), 66–125.

Meagher, B. R., and Marsh, K. L. (2014). The costs of cooperation: Action-specific perception in the context of joint action. Journal of experimental psychology: human perception and performance 40, 429. doi: 10.1037/a0033850

Moore, P., and Robinson, A. (2016). The quantified self: What counts in the neoliberal workplace. New Media & Society 18, 2774–2792. doi: 10.1177/1461444815604328

Nistor, N., and Stanciu, I. D. (2017). “Being sexy” and the labor market: Self-objectification in job search related social networks. Computers in Human Behavior 69, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.005

Orehek, E., and Weaverling, C. G. (2017). On the Nature of Objectification: Implications of Considering People as Means to Goals. Perspectives on Psychological Science 12, 719–730. doi: 10.1177/1745691617691138

Orehek, E., and Forest, A. L. (2016). When people serve as means to goals: Implications of a motivational account of close relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25, 79–84. doi: 10.1177/0963721415623536

Osiurak, F., Morgado, N., Vallet, G. T., Drot, M., and Palluel-Germain, R. (2014). Getting a tool gives wings: overestimation of tool-related benefits in a motor imagery task and a decision task. Psychological research 78, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00426-013-0485-9

Proffitt, D. R. (2006). Embodied perception and the economy of action. Perspectives on psychological science 1, 110–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00008.x

Revelle, W. (2015). psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. R package version 1.5.1.

Renger, D., Mommert, A., Renger, S., and Simon, B. (2016). When less equal is less human: Intragroup (dis)respect and the experience of being human. The Journal of Social Psychology 5, 553–563. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2015.1135865

Rochford, K. C., Jack, A. I., Boyatzis, R. E., and French, S. E. (2016). Ethical leadership as a balance between opposing neural networks. Journal of Business Ethics 144, 755–770. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3264-x

Rollero, C., and Tartaglia, S. (2013). Men and women at work: the effect of objectification on competence, pay, and fit for the job. Studia Psychologica 55, 139–152. doi: 10.21909/sp.2013.02.631

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of statistical software 48, 1–36. doi: 10.1002/9781119579038.ch1

Sanders, S., Wisse, B. M., and Yperen, N. W. V. (2015). Holding Others in Contempt: the Moderating Role of Power in the Relationship Between Leaders’Contempt and their Behavior Vis-a-vis Employees. Business Ethics Quarterly 25, 213–241. doi: 10.1017/beq.2015.14

Shields, J., and Grant, D. (2010). Psychologising the Subject: HRM, Commodification, and the Objectification of Labour. The Economic and Labour Relations Review 20, 61–76. doi: 10.1177/103530461002000205

Szymanski, D. M., and Feltman, C. E. (2015). Linking Sexually Objectifying Work Environments Among Waitresses to Psychological and Job-Related Outcomes. Psychology of Women Quarterly 39, 390–404. doi: 10.1177/0361684314565345

Szymanski, D. M., and Mikorski, R. (2016). Sexually objectifying restaurants and waitresses’ burnout and intentions to leave: The roles of power and support. Sex Roles 75, 328–338. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0621-210.1007/s11199-016-0621-2

Timmermans, S., and Almeling, R. (2009). Objectification, standardization, and commodification in health care: A conceptual readjustment. Social Science & Medicine 69, 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.020

Volpato, C., and Andrighetto, L. (2015). Dehumanization. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 6, 31–37.

Wiener, R. L., Gervais, S. L., Allen, J., and Marquez, A. (2013). Eye of the Beholder: Effects of Perspective and Sexual Objectification on Harassment Judgments. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 19, 206–221. doi: 10.1037/a0028497

Keywords: objectification in the workplace, questionnaire, action, social perception, dehumanization

Citation: Crone L, Brunel L and Auzoult L (2021) Validation of a Perception of Objectification in the Workplace Short Scale (POWS). Front. Psychol. 12:651071. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651071

Received: 08 January 2021; Accepted: 04 May 2021;

Published: 07 June 2021.

Edited by:

Sai-Fu Fung, City University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Andrea Svicher, University of Florence, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Crone, Brunel and Auzoult. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lola Crone, bG9sYS5jcm9uZUB1bml2LW1vbnRwMy5mcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.