94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 21 May 2021

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.650070

This article is part of the Research Topic Advances in Youth Bullying Research View all 14 articles

We recruited 1,631 middle and high school students to explore the relationship between personality traits and school bullying, and the moderated and mediating roles of self-concept and loneliness on this relationship. Results showed that (1) neuroticism had a significant positive predictive effect on being bullied, extroversion had a significant negative predictive effect on being bullied, and agreeableness had a significant negative predictive effect on bullying/being bullied; (2) loneliness played a mediating role between neuroticism and bullied behaviors, extroversion and bullying behaviors, and agreeableness and bullying/bullied behaviors; (3) self-concept played a moderating role on the mediation pathway of loneliness on neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness and bullying behaviors. Therefore, to reduce the frequency of school bullying among adolescents, we should not only reduce their levels of loneliness but also improve their levels of self-concept.

School bullying has been defined as “a specific form of aggression, which is intentional, repeated, and involves a disparity of power between the victims and perpetrators” (Olweus, 1993a,b). In addition, some studies found that sexual violence (McMahon et al., 2019; Madrid et al., 2020) and cyberbullying (Livazović and Ham, 2019; Ige, 2020) were two emerging forms of adolescent violence in today’s society. Bullying is an extremely damaging type of violence present in schools all over the world (Zych et al., 2019). According to previous research, in addition to the effects of physical injury, bullying can lead to decreased self-confidence, self-esteem, and academic performance. It will cause inattention, absenteeism, anxiety, headaches, insomnia, nightmares, depression, and other related symptoms. In extreme cases, students may even commit suicide (Sharp and Smith, 1994). Due to the prefrontal cortex’s inhibition of physical activities, emotional processing is regulated by threat experience, and thus adolescents risk emotional dysregulation and increased internalization problems when they are subjected to threat experiences (Weissman et al., 2019). School problems, peer victimization, parent–child relationship quality issues, and friendship quality issues all affect the anxiety level of adolescents (Nelemans et al., 2017). Campus bullying cannot only cause depression in teenagers but it can also have a serious impact on their future social ability, learning ability, and academic performance (Chen and Chen, 2020). Bullying usually occurs in elementary school, a critical period in child development (Behnsen et al., 2020), and traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization increase the likelihood of avoidance behaviors and of bringing a weapon to school (Keith, 2018). An alarming fact is that bullying can lead to antisocial behavior in adulthood (Stubbs-Richardson et al., 2018). Olweus (1993a, b) pointed out that, often, students who bully others have a higher individual crime rate when they grow up, almost four times higher than others. In addition, victims of bullying are more likely to commit crimes in the future (Behnsen et al., 2020). Studies have shown that bullying victimization and perpetration correlate strongly and that their cross-lagged longitudinal relationship runs in both directions, meaning that perpetration is just as likely to lead to future victimization as victimization is to lead to future perpetration (Walters, 2020). Individuals who experienced the vicarious form (peer victimization) had a higher likelihood of experiencing the same type of victimization as their peers (Stubbs-Richardson and May, 2020). Therefore, improving research on school bullying and its influencing factors is of great significance to the prevention and governance of school bullying.

Bullying behaviors were not effectively measured by demographic variable (Abuhammad et al., 2020). But there are many factors affecting school bullying, among which the influence of personality traits is undeniable. Personality was first studied by Alport. Cattell later identified 16 personality traits. In 1949, Fiske analyzed 22 personality traits from Cattell’s vocabulary and found that five factors always appeared first on the list. These factors came to be known as the Big Five: Openness (imaginative, aesthetic, emotional, unconventional, creative, intelligent, etc.); Conscientiousness (showing competence, fairness; being methodical and dutiful; achieving self-discipline, prudence, restraint, etc.); Extraversion (showing warmth, sociability, assertiveness, optimism, etc.; engaging in activities; risk-taking); Agreeableness (having the characteristics of trustworthiness, altruism, frankness, compliance, modesty, empathy, etc.); Neuroticism (experiencing anxiety, hostility, depression, self-awareness, impulsivity, vulnerability, inability to maintain emotional stability) (Peng, 2001).

Since then, many scholars have studied the relationship between school bullying and personality traits. The compensation model of aggression proposes that low self-esteem leads to bullying behaviors (Staub, 1989). Moreover, the model modified by Nail et al. (2016) proposes that a defensive personality structure is an essential factor in causing bullying. This model details how bullying behaviors are driven by a bully’s personality, motivations, including narcissism, defensive self-centeredness, and inconsistent levels of high self-esteem (Nail et al., 2016). Previous research has indicated that adolescents who have these personality characteristics are likely to be associated with school bullying (Thomaes et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2016). More specifically, personality traits, such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and neuroticism, are significantly associated with school bullying (Miao, 2019).

Extroversion and conscientiousness are negatively related to school bullying (Yao, 2017). Perpetrators of bullying have been found to be prone to anger, silence, and emotional sensitivity, as well as high self-evaluations and psychoticism (Zhou and Ding, 2003), demonstrating that emotional instability is one factor affecting school bullying. In addition, Gu and Zhang (2003) found that self-esteem, extroversion, and neuroticism can significantly predict bullying or being bullied, and self-esteem, psychoticism, and neuroticism are significantly related to bullying in their study of the relationship between the bullying behaviors and personality traits of students in primary schools. Moreover, results of the independent analysis of the victims and perpetrators found that for perpetrators, their personalities are as a whole, and their bullying behaviors were in most cases caused by the interaction of negative cognitive tendencies towards society, negative attitudes toward bullying events, hyperactivity, emotional temperament characteristics, and specific stimulus events. And for victims, school bullying may be harmful to their personality development, and being bullied may also be associated with their own personality traits (Zhang et al., 2001).

Even though personality traits have been shown to have a significant impact on school bullying, there is no evidence to date demonstrating that personality traits can directly affect school bullying behaviors. The social bonds theory (Hirschi, 1969) notes that the links between increased crime rates and individuals and society are weak, whereas increased crime rates are closely related to a low consistency in social norms. In the study by Zhang et al. (2016), personality was significantly correlated with loneliness, and agreeableness, extroversion, openness, and conscientiousness were significantly negatively correlated with loneliness. According to Costa and Mccrae (1992), loneliness is an unpleasant experience that occurs when individuals feel that their social, interpersonal network is low in quality or insufficient in quantity. Furthermore, Zhang (2019) found that school bullying behaviors are significantly correlated with loneliness in elementary school students. School bullying and being bullied are also positively correlated with loneliness in middle school students (Zhou and Ding, 2003). It can therefore be seen that personality traits might affect loneliness, and loneliness might influence school bullying. Therefore, we proposed hypothesis one: loneliness plays a mediating role in the relationship between personality traits and school bullying.

Self-concept is defined by Shavelson as an individual’s overall view of himself based on interpersonal communications and living environment (Byrne and Shavelson, 1996). Previous research has also shown that various dimensions of personality traits have significant relationships with self-concept. For example, self-concept is highly positively correlated with extroversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, and it has a moderate positive correlation with openness and moderately negative correlation with neuroticism (Xiang et al., 2006). In the study by Xiang et al. (2006), personality was quickly clustered by researchers into categories 3–6. The results showed that four categories were justifiable: harmonious personalities (low scores for neuroticism and high scores for other dimensions); emotional personalities (very unstable neuroticism scores, medium scores for other dimensions); conservative personalities (low scores in all dimensions); passive personalities (average scores for neuroticism, low scores for all other dimensions). Furthermore, there are significant differences in the levels of self-concept in students who have different personality traits. Specifically, students with harmonious personalities have the highest levels of self-concept, followed by those with conservative personalities and finally, passive personalities which have the lowest (Xiang et al., 2006). Children’s self-concepts also play mediating roles in the influences of peer rejection and offensive behaviors on children’s relational aggression and physical attacks (Ji et al., 2012). The self-concept and self-esteem of adolescents are closely related to problem behaviors, and adolescents may attack others because their self-concepts are low (Donnellan et al., 2005; Diamantopoulou et al., 2008) or when they perceive that others do not recognize their self-concepts (Taylor et al., 2007; Diamantopoulou et al., 2008). With regard to this phenomenon, humanistic psychology explains that negative self-attention and vague self-concepts result in aggressive behaviors (Donnellan et al., 2005). It is easy to see that the level of self-concept is not only related to personality traits but also affects the adolescents’ being bullied and the bullying behaviors of perpetrators. In addition, the clarity of adolescents’ self-concept is significantly negatively correlated with loneliness (Xu et al., 2017). Students who have lower self-concepts suffer strong feelings of loneliness (Chen and Zhang, 2010), meaning that individuals with weaker self-concepts tend to develop high levels of loneliness.

In summary, personality traits significantly influence school bullying and loneliness, and loneliness also affects school bullying. Students with weaker self-concepts tend to develop high levels of loneliness, and high levels of loneliness may predict aggressive behaviors. Therefore, different self-concept levels could affect the development of loneliness, while the degree of loneliness could affect the impact of personality traits on school bullying. Thus, we proposed hypothesis two: self-concept plays a moderating role in the mediation pathway for loneliness on the relationship between personality traits and school bullying.

The purpose of the current study was to establish a moderated mediation model (see Figure 1) to explore the mediating role of loneliness on the relationship between personality traits and school bullying, as well as the moderating role of self-concept in the mediation pathway.

A total of 2,000 adolescents at two high schools in Chongqing and Shandong received the questionnaire survey through convenience sampling. On completion, 1,631 valid questionnaires were returned reflecting an effective response rate of 81.55%.

Participants were aged 11–21 years old [mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD) = 15.39 ± 1.37], with 755 (46.3%) being male and 876 (53.7%) being female. Among the junior high school students, 88 were from the first grade, 99 were from the second grade, and 275 were from the third grade. Among the senior high school students, 606 were from the first grade, 522 were from the second grade, and 47 were from the third grade.

We used the NEO-FFI Questionnaire which was modified by Costa and Mccrae (1992). There are 60 questions which constitute five subscales: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. The α coefficient in this study was 0.70.

We used the Bully/Victim Questionnaire established by Olweus (1993a, b) and modified by Zhang and Wu (1999). The α coefficient in this study was 0.903.

We used the Self-concept Clarity Scale established by Campbell et al. (1996) and modified by Chen and Ouyang (2013). There are 12 questions in total (including “My view of myself often conflicts with other people’s view of me,” “My thoughts about myself change very frequently,” etc.). Use a 5-point Likert score (1 = “strongly disagree,” 5 = “strongly agree”) to evaluate, and calculate the total score of all questions in the scale. This scale effectively reflects the extent to which individuals clearly determine their own self-concept. The α coefficient in this study was 0.758.

We used the UCLA Loneliness Scale established by Russell (1996) and modified by Wang (1995). There are 18 questions in total. The scale consists of 18 items (including “I feel sorry for others,” “I feel so lonely,” “I cannot find someone I can talk to,” etc.) using a 4-point score from “never” to “always.” The α coefficient in this study was 0.892.

The self-reported questionnaire was completed anonymously during school classes. The researchers were postgraduate students in the Key Laboratory of Applied Psychology, proficient in psychological research methods. Data collection was completed in February 2020. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0. Our research has been registered on the Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/8x6a4/.

In this study, data were obtained from questionnaires meaning that common method biases might affect the results. In order to minimize these influences, we adopted control measures, such as reverse scoring, anonymous reporting, and Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Results showed 21 factors with characteristic roots over 1, and the variance explanation rate of the first common factor was 14.62%, which was less than 40%. Therefore, the current study was not significantly affected by common method biases, and the data were deemed reliable.

Our study performed descriptive statistics and correlation analysis on the five personality trait dimensions, self-concept, loneliness, and the two dimensions of school bullying (bullying/being bullied). We found that neuroticism was significantly positively correlated with self-concept, loneliness, and being bullied. Extraversion was significantly negatively correlated with self-concept, loneliness, and being bullied. Openness was significantly negatively correlated with self-concept and loneliness. Agreeableness was significantly negatively correlated with self-concept, loneliness, and bullying/being bullied. Loneliness was significantly positively correlated with self-concept and bullying/being bullied. Self-concept and being bullied were significantly positively correlated. However, in our study, openness and conscientiousness were not significantly correlated with bullying/being bullied. In some western studies, teenagers who reported bullying scored lower on conscientiousness and openness (Turner and Ireland, 2010; Fossati et al., 2012), as well as lower level of conscientiousness was also associated with being bullied (Effrosyni and Theodoros, 2015). Different from the western countries, children in the traditional Chinese families are not truly independent until they get married, and before that, they may live under the control of their parents, thus there may be ideological differences on conscientiousness and openness. Additionally, in our other interview study, we found that few class leaders with good grades and strong sense of responsibility also have some bullying behaviors, such as verbal bullying and relationship manipulation. So we suspect that conscientiousness and openness did not affect school bullying directly in this study probably because of regional and cultural differences, as well as the selection of samples. The specific results are shown in Table 1.

First, the data were standardized. Second, the macro program PROCESS in SPSS was used to test the moderated mediating model. Finally, the deviation correction and the percentile Bootstrap method were set. The number of repeated sampling was set to 5,000 for inspection and the confidence interval (CI) was set to 95%. The results are shown in Table 2.

The test of the mediating effect was then conducted. We used Model 4 of the SPSS macro designed by Hayes (2012) controlling for gender and age (not shown in the table) to perform the mediating effect test of loneliness on the various personality trait dimensions. Results of the regression analysis (see Tables 2, 3) showed that neuroticism had a positive predictive effect on being bullied, β = 0.216, p < 0.001. After incorporating loneliness into the regression equation, neuroticism still had a significantly predictive effect on being bullied, β = 0.080, p < 0.01, and a positively predictive effect on loneliness, β = 0.566, p < 0.001. Loneliness had a positively predictive effect on being bullied, β = 0.241, p < 0.001, Boot SE = 0.010, 95% CI = 0.062, 0.100. This indicated that the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between neuroticism and being bullied was significant.

Similarly, extraversion had a negatively predictive effect on being bullied, β = −0.129, p < 0.001. After incorporating loneliness into the regression equation, extroversion converted to a significantly positive predictive effect on being bullied, β = 0.076, p < 0.01, and a negatively predictive effect on loneliness β = −0.619, p < 0.001. Loneliness had a positively predictive effect on being bullied, β = 0.331, p < 0.001, Boot SE = 0.010, 95% CI = 0.091, 0.132. This showed that the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between extroversion and being bullied was significant.

Agreeableness had a negatively predictive effect on being bullied, β = −0.224, p < 0.001. After incorporating loneliness into the regression equation, agreeableness still had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, β = −0.133, p < 0.01, and a negatively predictive effect on loneliness, β = −0.42, p < 0.001. Loneliness had a positively predictive effect on being bullied β = 0.25, p < 0.001, Boot SE = 0.009, 95% CI = 0.062, 0.096. This showed that the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between agreeableness and being bullied was significant.

In addition, agreeableness had a negatively predictive effect on bullying, β = −0.149, p < 0.001. After incorporating loneliness into the regression equation, agreeableness still had a significantly predictive effect on bullying, β = −0.120, p < 0.001, and a negatively predictive effect on loneliness, β = −0.419, p < 0.001. Loneliness had a positively predictive effect on bullying, β = 0.070, p < 0.01, Boot SE = 0.027, 95% CI = 0.017, 0.123. This showed that the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between agreeableness and bullying was significant.

It should be noted that the upper and lower limits for the bootstrap 95% CIs for the direct effects of neuroticism, extroversion, and agreeableness on bullying/being bullied behaviors, as well as the mediating effect of loneliness, did not contain 0 (see Table 3). This showed that neuroticism, extroversion, and agreeableness could not only directly influence bullying/being bullied behaviors but also could predict bullying/being bullied behaviors through the mediating effect of loneliness.

The test of the moderated mediation model was then performed. We established a moderated mediation model consisting of three personality trait dimensions (neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness) and school bullying/being bullied, in which we regarded loneliness as the mediating variable and self-concept as the moderating variable using the Model 14 of the SPSS macro designed by Hayes (2012). The results are shown in Tables 4, 5.

From Table 4, we can see that for the dimension of neuroticism, the product term of loneliness and self-concept had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, t = 3.293, p < 0.01, after incorporating self-concept into the model, which meant that self-concept played a moderated role in the predictive effect of loneliness on being bullied. Similarly, for the dimension of extroversion, the product term of loneliness and self-concept had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, t = 3.051, p < 0.01, as well as for the dimension of agreeableness, and the product term for loneliness and self-concept had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, t = 3.845, p < 0.001. Thus, self-concept played a moderating role in the predictive effect of loneliness on being bullied both for the dimension of extroversion and agreeableness. However, self-concept did not play a moderating role in the predictive effect of loneliness on school bullying for the dimension of agreeableness, so these results are not presented.

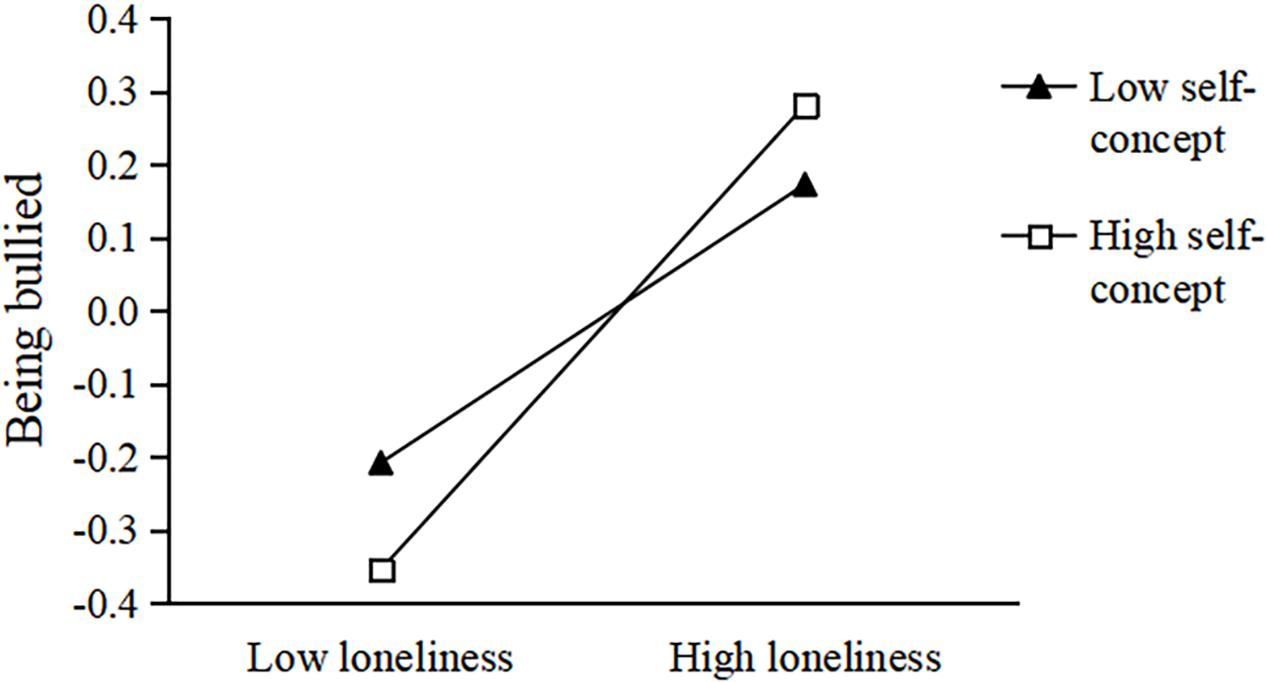

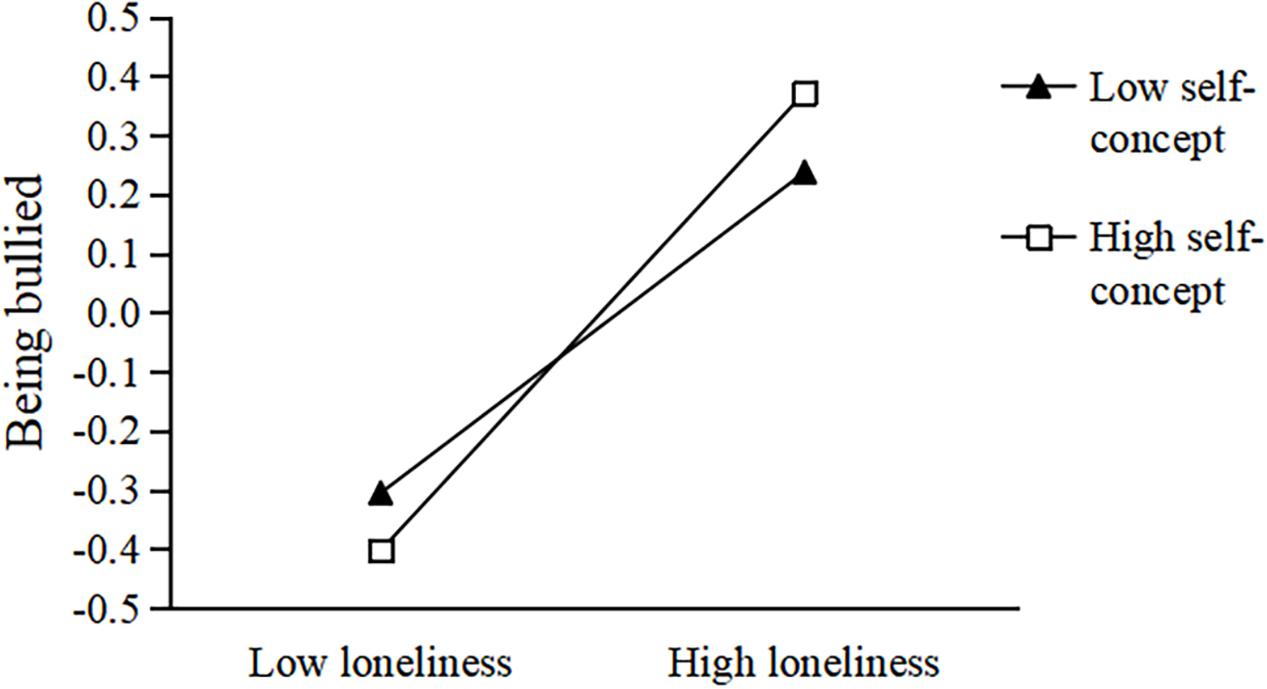

To better understand the moderated effect, we performed a simple slope test (Aiken and West, 1991). Data were divided into high and low groups according to self-concept values (M ± 1 SD). In the second half of the neuroticism-loneliness-being bullied pathway, when the level of self-concept was −1 SD, loneliness had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, b = 0.191, t = 5.335, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.195, 0.349. When the level of self-concept was +1 SD, loneliness still had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, b = 0.318, t = 9.130, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.250, 0.387 (see Figure 2). Meanwhile, in the second half of the extroversion-loneliness-being bullied pathway, when the level of self-concept was −1 SD, loneliness had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, b = 0.271, t = 6.917, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.195, 0.349. When the level of self-concept was +1 SD, loneliness still had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, b = 0.388, t = 10.519, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.315, 0.460 (see Figure 3). Moreover, in the second half of the agreeableness-loneliness-being bullied pathway, when the level of self-concept was −1 SD, loneliness had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, b = 0.148, t = 4.252, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.080, 0.216. When the level of self-concept was +1 SD, loneliness still had a significant predictive effect on being bullied, b = 0.302, t = 9.184, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.237, 0.366 (see Figure 4).

Figure 2. The influence of loneliness on the relationship between being bullied and neuroticism: the moderated effect of self-concept. The black triangle represents low self-concept and the white square represents high self-concept.

Figure 3. The influence of loneliness on the relationship between being bullied and extroversion: the moderated effect of self-concept. The black triangle represents low self-concept and the white square represents high self-concept.

Figure 4. The influence of loneliness on the relationship between being bullied and agreeableness: the moderated effect of self-concept. The black triangle represents low self-concept and the white square represents high self-concept.

To sum up, when individuals had a low level of loneliness, the increased self-concept level was beneficial in reducing the occurrence of being bullied. However, when individuals had a high level of loneliness, the increased level of self-concept increased the occurrence of being bullied. Therefore, improving self-concept levels could reduce the incidence of being bullied by individuals with low levels of loneliness. Reducing the levels of loneliness would be conducive to reducing the incidence of being bullied by individuals with high loneliness.

The current study explored the direct impact of personality traits on school bullying and the mediating role of loneliness on the relationship between personality traits and school bullying/being bullied.

Results showed that loneliness played a mediating role in the relationships between neuroticism, extroversion, agreeableness, and being bullied. Therefore, each specific personality trait not only directly affected school bullying behaviors but also influenced being bullied behaviors through the mediating effect of loneliness.

When an individual’s interpersonal relationships do not reach their aspiration level, they are likely to experience loneliness, and this is accompanied by negative psychological states such as emptiness, boredom, helplessness, and depression (Kim, 2017). Personality is an essential influencing factor on loneliness (Schmitt and Kurdek, 1985). For example, extroversion, conscientiousness, and openness are positively related to adolescents’ effective social adaptation (Nie et al., 2008). Adolescents with high neuroticism levels generally have low interpersonal satisfaction (Lopes et al., 2003). In contrast, individuals with high agreeableness levels are better at controlling their emotions and resolving interpersonal conflicts (Graziano et al., 1996).

Individuals with a high level of extroversion are also better at communicating (Rothbart and Hwang, 2005), so they more easily establish positive interpersonal relationships. Therefore, personality traits affect the quality of interpersonal relationships, and aspiration levels of interpersonal relationships influence levels of loneliness, which can lead to school bullying/being bullied behaviors. To prevent teenagers from being negatively affected by school bullying/being bullied, it is necessary to cultivate good interpersonal relationships among adolescents and reduce their loneliness. In addition, studies indicated that a problematic parent–child relationship negatively predicted loneliness and depression in children (Fan and Wu, 2020), and the parent–child relationship could have a significant influence on school bullying. Some studies found that higher parental rejection and lower parental warmth predicted increases in peer victimization and vice versa (Kaufman et al., 2019). Research studies provided the evidence of highly significant effects of parenting interventions on bullying reduction (Chen et al., 2020). And some studies indicated that maternal love withdrawal prospectively predicted more aggressive bullying behaviors, whereas guilt induction predicted lower levels of aggressive bullying behaviors in children 6 months later (Yu et al., 2019). Therefore, bullying behaviors can be prevented by establishing a good parent–child relationship.

After exploring the mediating role of loneliness on the relationship between personality traits and school bullying behaviors, we further examined the moderated role of self-concept in this mediating pathway.

The results showed that first, self-concept played a moderating role in the mediating pathway of loneliness on neuroticism and being bullied. Previous research has found that neuroticism is positively related to school bullying, and higher neuroticism is associated with a greater likelihood of psychological stress, impulsivity, and emotional reactivity (Zhou et al., 2019). On the contrary, teenagers with healthy mental states have a better understanding of all aspects of their self-concept, and their relationships in different domains (such as teacher–student, peer–peer, and parent–child relationships) are more harmonious (Shen et al., 2019). Crimes committed by young offenders may be related to their lack of a positive self-concept (Zhong and Liu, 2013), which means that adolescents with high self-concepts tend to have fewer problematic behaviors. Self-concept in the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between neuroticism and being bullied would also promote the healthy development of adolescents who are experiencing bullying dilemmas.

Second, the results showed that self-concept played a moderating role in the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between extroversion and being bullied. In our study, extroversion was significantly negatively related to bullying, showing that more introverted teenagers are more vulnerable to being bullied. Zhou et al. (2008) reported that individuals who are outgoing, cheerful, easy-going, and self-disciplined have higher levels of positive mental health, indicating that introversion and extroversion impact an individuals’ levels of mental health. The poorer the level of mental health, the more ambiguous the self-concept is, thus the less effective moderated effect of self-concept in the mediating role of loneliness on the relationship between extroversion and being bullied, leading to bullying behaviors. Therefore, enhancing students’ self-concept would be a macro measure, closely associated with parenting patterns, social supports (Li et al., 2017) and peer relationships (Li et al., 2013), as well as the differing developmental characteristics in every stage of teenagers’ growth. Due to the moderating role of self-concept in the mediating effect of loneliness on personality traits and bullying/being bullied, constructing comfortable school atmospheres (Xie and Mei, 2019) and perfecting personality educations (Miao, 2019) may overcome the negative impacts of school bullying. To be specific, first, education departments should offer targeted psychological guidance according to the different personality characteristics of teenagers, such as counseling for bullies with low self-esteem, paying attention to vulnerable victims with high self-esteem (Choi and Park, 2018), and preventing bullying by those with defensive personalities. Second, mental health courses on cultivating a healthy personality should be offered to teenagers. Such courses could strengthen self-affirmation training (Thomaes et al., 2009) and cultivate emotional regulation ability (Garofalo et al., 2016). Studies showed that educational interventions are effective in reducing the frequency of traditional and cyberbullying victimization and perpetration (Ng et al., 2020).

Third, our results showed that self-concept played a moderating role in the mediating pathway of loneliness on the relationship between agreeableness and being bullied, but it had no moderating role in the mediating effect of loneliness between agreeableness and bullying. The simple slope test results found that when school bullying occurred, there was a more obvious moderated effect of self-concept on students with low loneliness. Consequently, the levels of self-concept had a more significant effect on bullying. In the present study, agreeableness and bullying/being bullied were both significantly negatively correlated. One previous study manifested that agreeableness has a significantly negative correlation with depressive symptoms. Specifically, adolescents who are friendly and obedient are more likely to be approved by parents and society, and thus they are less likely to encounter adverse life events and have relatively fewer depressive symptoms (Zhang et al., 2019). Moreover, being bullied is closely related to depression (Chen et al., 2020). Being bullied could increase the severity of students’ depression (Cao et al., 2020), which would reduce their agreeableness level. Hence, higher agreeableness is associated with lower levels of bullying/being bullied, especially for adolescents who get along well with their classmates and teachers and experience harmonious family atmospheres.

Why did self-concept have a significant moderated effect on being bullied but no significant moderated effect on bullying? Scores for neuroticism increase with age, meaning that scores for some other personality traits may be replaced by it over time (Zhang et al., 2019). In addition, when individuals are in the transition from childhood to adolescence, personality traits might temporarily err towards immaturity. There is a temporary decline in the level of agreeableness from late childhood to middle adolescence (Akker et al., 2014). Consequently, a decline in agreeableness may explain why the moderated effect of self-concept on the mediating pathway was not significant in our study. Specific factors need to be further studied.

To sum up, school bullying/being bullied is harmful to students’ physical and mental health, so this issue deserves our continuous attention and reflection. Levels of neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness can positively or negatively predict school bullying. Furthermore, a high level of loneliness could exacerbate bullying/being bullied, while a higher self-concept could reduce the incidence of school bullying. Therefore, helping students have an unambiguous self-concept as well as reducing their loneliness are crucial approaches to reducing school bullying. However, some studies indicate that existing educational interventions had a very small to zero effect size on traditional bullying and cyberbullying perpetration. More research is needed to identify the key moderators that enhance educational programs and to develop alternative forms of anti-bullying interventions (Ng et al., 2020). Additionally, bullying can also be caused by some unconventional factors nowadays, such as the long-term use of adult drugs (alcohol, tobacco, various drugs; Zych et al., 2021) and dating violence (Quinn and Stewart, 2018). Thus, this situation implies that educators’ responses to school bullying should adapt to the rapidly changing modern world.

Our key findings can be summarized as follows:

1) Neuroticism had a significantly positive predictive effect on being bullied, extroversion had a significantly negative predictive effect on being bullied, and agreeableness had a significantly negative predictive effect on bullying/being bullied.

2) Loneliness played a mediating role between neuroticism and bullied behaviors, extroversion and bullying behaviors, and agreeableness and bullying/bullied behaviors.

3) Self-concept played a moderated role in the mediation pathway of loneliness in neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and bullying behaviors.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://pan.baidu.com/s/1yzvKsezYCG8ihuKmSTIcWA; password: nyh8.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee of Chongqing Normal University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

YZ: the principal author of the manuscript, consult literature, and logging date. ZL: advisor. YT: data analysis. XZ, QZ, and XC: logging date. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by Chongqing Education Scientific Planning Project: 2017-GX-119.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abuhammad, S., Alnatour, A., and Howard, K. (2020). Intimidation and bullying: A school survey examining the effect of demographic data. Heliyon 6:e04418. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04418

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions - institute for social and economic research (iser). Eval. Pract. 14, 167–168. doi: 10.1057/jors.1994.16

Akker, A. L. V. D., Dekoviæ, M., Asscher, J. J., and Prinzie, P. (2014). Mean-level personality development across childhood and adolescence: a temporary defiance of the maturity principle and bidirectional associations with parenting. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 107, 736–750. doi: 10.1037/a0037248

Behnsen, P., Buil, J. M., Koot, S., Huizink, A., and Lier, P. V. (2020). Heart rate (variability) and the association between relational peer victimization and internalizing symptoms in elementary school children. Devel. Psychopathol. 32, 521–529. doi: 10.1017/s0954579419000269

Byrne, B. M., and Shavelson, R. J. (1996). On the structure of social self-concept for pre-, early, and late adolescents: a test of the Shavelson, Hubner, and Stanton (1976) model. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 70, 599–613. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.599

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., and Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 70, 141–156. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.141

Cao, X. Q., Tian, M., Song, Y. Q., Li, Z. Y., Wang, Q. W., and Wang, L. (2020). The correlation between cyberbullying and depression of college students (in Chinese). Chin. School Health 41, 235–238.

Chen, F. X., and Zhang, F. J. (2010). The characteristics and relationship of peer attachment, self-concept and loneliness of students in work-study schools (in Chinese). Psychol. Devel. Educat. 26, 76–83. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2010.01.012

Chen, J., and Ouyang, W. F. (2013). Reliability and validity analysis of the Chinese version of the Self-Concept Clarity Scale for middle school students (in Chinese). J. Educat. Sci. Hun. Normal Univ. 12, 127–129.

Chen, L., and Chen, X. (2020). Affiliation with depressive peer groups and social and school adjustment in Chinese adolescents. Dev. Psychopathol. 32, 1087–1095. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419001184

Chen, Q., Zhu, Y., and Chui, W. H. (2020). A Meta-Analysis on Effects of Parenting Programs on Bullying Prevention. Trauma 2020:619. doi: 10.1177/1524838020915619

Chen, T., Fan, Y., Zhang, Z. H., and Fang, X. Y. (2020). Correlation between bullying behavior and depression among middle school students in Jiangxi Province (in Chinese). Chin. School Health 41, 600–603.

Choi, B., and Park, S. (2018). Who Becomes a Bullying Perpetrator After the Experience of Bullying Victimization? The Moderating Role of Self-esteem. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 913–917. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0913-7

Costa, P. T., and Mccrae, R. R. (1992). Multiple uses for longitudinal personality data. Europ. J. Person. 6, 85–102. doi: 10.1002/per.2410060203

Diamantopoulou, S., Rydell, A., and Henricsson, L. (2008). Can both low and high self-esteem be related to aggression in children. Soc. Devel. 17, 682–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00444.x

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., and Casp, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychol. Sci. 16, 328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x

Effrosyni, M., and Theodoros, G. (2015). Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: A meta-analytic approach. Aggres. Violent Behav. 21, 61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.007

Fan, Z. Y., and Wu, Y. (2020). Parent-child Relationship and Loneliness and Depression in Rural Left-behind Children: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Gratitude (in Chinese). Psychol. Devel. Educat. 6, 734–742. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2020.06.12

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., and Maffei, C. (2012). Bullying as a style of personal relating: Personality characteristics and interpersonal aspects of self−reports of bullying behaviours among Italian adolescent high school students. Person. Mental Health 6, 325–339. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1201

Garofalo, C., Holden, C. J., Zeigler-Hill, V., and Velotti, P. (2016). Understanding the connection between self-esteem and aggression: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Aggressive Behav. 42, 3–15. doi: 10.1002/ab.21601

Graziano, W. G., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., and Hair, E. C. (1996). Perceiving interpersonal conflict and reacting to it: The case for agreeableness. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 70, 820–835. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.820

Gu, C. H., and Zhang, W. X. (2003). The relationship between bullying and personality tendencies in primary school children (in Chinese). Acta Psychol. Sin. 01, 101–105.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Manuscr. Submit. Publicat. 2012:1642.

Ige, O. A. (2020). What we do on social media! Social representations of schoolchildren’s activities on electronic communication platforms. Heliyon 6:e04584. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04584

Ji, L. Q., Wei, X., Chen, L., and Zhang, W. X. (2012). Peer Relationship Adversities and Children’s Aggression During Late Childhood: The Mediating Roles of Self-conception and Peer Beliefs (in Chinese). Acta Psychol. Sin. 44, 1479–1489. doi: 10.3724/sp.j.1041.2012.01479

Kaufman, T. M. L., Kretschmer, T., Huitsing, G., and Veenstra, R. (2019). Caught in a vicious cycle? Explaining bidirectional spillover between parent-child relationships and peer victimization. Devel. Psychopathol. 32, 11–20. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001360

Keith, S. (2018). How do Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization Affect Fear and Coping among Students? An Application of General Strain Theory. Am. J. Crim. Justice 43, 67–84. doi: 10.1007/s12103-017-9411-9

Kim, J. H. (2017). Smartphone-mediated communication vs face-to-face interaction: two routes to social support and problematic use of smartphone. Comput. Hum. Behav. 67, 282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.004

Li, F., Cha, Y. Y., Liang, H. Y., Yang, C., and Zheng, X. (2017). The relationship between self-concept clarity, social support, self-esteem and subjective well-being of secondary vocational students (in Chinese). Chin. Mental Health J. 31, 896–901.

Li, X. L., Ling, H., Zhang, J. R., Si, X. F., and Ma, X. Y. (2013). The influence of the time of onset of puberty on boys’ self-concept and peer relationship (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 21, 512–514.

Livazović, G., and Ham, E. (2019). Cyberbullying and emotional distress in adolescents: the importance of family, peers and school. Heliyon 5:6. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01992

Lopes, P. N., Salovey, P., and Straus, R. (2003). Emotional intelligence, personality, and the perceived quality of social relationships. Person. Indiv. Diff. 35, 641–658. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00242-8

Madrid, B. J., Lopez, G. D., Dans, L. F., Fry, D. A., Duka-Pante, F. G. H., and Muyot, A. T. (2020). Safe schools for teens: preventing sexual abuse of urban poor teens, proof-of-concept study-Improving teachers’ and students’ knowledge, skills and attitudes. Heliyon 6:6. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04080

McMahon, S., Steiner, J. J., Snyder, S., and Banyard, V. L. (2019). Expanding Who Is Invited to the Table. Trauma 2019:275. doi: 10.1177/1524838019883275

Miao, L. (2019). The Causes and Educational Enlightenment of School Bullying from the Perspective of Personality (in Chinese). Mental Health Educat. Prim. Sec. Schools 391, 9–13.

Nail, P. R., Simon, J. B., Bihm, E. M., and Beasley, W. H. (2016). Defensive egotism and bullying: gender differences yield qualified support for the compensation model of aggression. J. School Viol. 15, 22–47. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2014.938270

Nelemans, S. A., Hale, W. W., Branje, S., Meeus, W., and Rudolph, K. D. (2017). Individual differences in anxiety trajectories from Grades 2 to 8: Impact of the middle school transition. Devel. Psychopathol. 2017, 1–15.

Ng, E. D., Chua, J. Y. X., and Shorey, S. (2020). The Effectiveness of Educational Interventions on Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma 2020:3867. doi: 10.1177/1524838020933867

Nie, Y. G., Lin, C. D., Zheng, X., Ding, L., and Peng, Y. S. (2008). The relationship between adolescents’ social adaptation behaviors and the Big Five personality (in Chinese). Psychol. Sci. 031, 774–779.

Olweus, D. (1993b). Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long-term outcomes. Soc. Withdr. Inhib. Shyn. 1993. 315–341.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Quinn, S. T., and Stewart, M. C. (2018). Examining the Long-Term Consequences of Bullying on Adult Substance Use. Am. J. Criminal Just. 43, 85–101. doi: 10.1007/s12103-017-9407-5

Rothbart, M. K., and Hwang, J. (2005). “Temperament and the development of competence and motivation,” in Handbook of competence & motivation, eds A. J. Elliot and C. S. Dweck (New York: Guilford Press), 167–184.

Russell, D. W. (1996). Ucla loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 66, 20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

Schmitt, J. P., and Kurdek, L. A. (1985). Age and gender differences in and personality correlates of loneliness in different relationships. J. Person. Asses. 49, 485–496. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4905_5

Sharp, S., and Smith, P. K. (1994). Tackling Bullying in Your School: A Practical Handbook for Teachers. London: Routledge.

Shen, Y. N., Xie, F., Wang, Y. W., Qu, X. F., Li, L., and Song, L. P. (2019). The relationship between parental rearing styles and emotions of adolescents: the mediating role of self-concept (in Chinese). Psychol. Monthly 14, 19–21.

Simon, J. B., Nail, P. R., Swindle, T., Bihm, E. M., and Joshi, K. (2016). Defensive egotism and self-esteem: a cross-cultural examination of the dynamics of bullying in middle school. Self Identity 16, 270–297. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2016.1232660

Staub, E. (1989). The roots of evil: the origins of genocide and other group violence. Int. J. offend. Ther. Comp. Criminol. 44, 261–263.

Stubbs-Richardson, M., and May, D. C. (2020). Social Contagion in Bullying: an Examination of Strains and Types of Bullying Victimization in Peer Networks. Am. J. Crim. Justice 20:9572. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09572-y

Stubbs-Richardson, M., Sinclair, H. C., Goldberg, R. M., Ellithorpe, C. N., and Amadi, S. C. (2018). Reaching Out versus Lashing Out: Examining Gender Differences in Experiences with and Responses to Bullying in High School. Am. J. Crim. Just. 43, 39–66. doi: 10.1007/s12103-017-9408-4

Taylor, L. D., Davis-Kean, P., and Malanchuk, O. (2007). Self-esteem, academic self-concept, and aggression at school. Aggres. Behav. 33, 130–136. doi: 10.1002/ab.20174

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., de Castro, B. O., Cohen, G. L., and Denissen, J. J. A. (2009). Reducing Narcissistic Aggression by Buttressing Self-Esteem: An Experimental Field Study. Psychol. Sci. 20, 1536–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02478.x

Turner, P., and Ireland, J. L. (2010). Do personality characteristics and beliefs predict intra−group bullying between prisoners? Aggress. Behav. 36, 261–270. doi: 10.1002/ab.20346

Walters, G. D. (2020). School-Age Bullying Victimization and Perpetration: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies and Research. Trauma 90:6513. doi: 10.1177/1524838020906513

Wang, D. F. (1995). A study on the reliability and validity of the Russell Loneliness Scale (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 01, 23–25.

Weissman, D. G., Guyer, A. E., Ferrer, E., Robins, R. W., and Hastings, P. D. (2019). Tuning of brain-autonomic coupling by prior threat exposure: Implications for internalizing problems in Mexican-origin adolescents. Devel. Psychopathol. 31, 1127–1141. doi: 10.1017/s0954579419000646

Xiang, X. P., Zhang, C. M., and Zhou, H. (2006). The developmental characteristics of primary school students’ self-concept and its correlation with personality (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 14, 294–296.

Xie, J. S., and Mei, L. (2019). The influence of bullying victimization of middle school students on their internalization problems: a moderated mediating model (in Chinese). Psychol. Explor. 39, 379–384.

Xu, H. H., Sun, X. J., Zhou, Z. K., Niu, G. F., and Lian, S. L. (2017). True self-expression in social networking sites and adolescent loneliness: the mediating role of self-concept clarity (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 25, 138–141+137.

Yao, X. M. (2017). The Causes and Avoidance of Bullying in Elementary and Secondary Schools from the Perspective of Psychology (in Chinese). J. Sci. Educat. 22, 159–160.

Yu, J., Cheah, C. S. L., Hart, C. H., Yang, C., and Olsen, J. A. (2019). Longitudinal effects of maternal love withdrawal and guilt induction on Chinese American preschoolers’ bullying aggressive behavior. Devel. Psychopathol. 31, 1467–1475. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001049

Zhang, L. Y. (2019). A Study on the Influencing Factors of Pupils’ Bullying Behavior on Campus (in Chinese). J. Shangqiu Teach. College 35, 91–95.

Zhang, M. L., Han, J., Ding, H. S., Wang, K. Q., Kang, C., Gong, Y. S., et al. (2019). The relationship between adolescent trauma experience and depressive symptoms and personality characteristics (in Chinese). Chin. Mental Health J. 33, 52–57.

Zhang, W. X., and Wu, J. F. (1999). Revision of the Chinese version of the Olweus Children Bullying Questionnaire (in Chinese). Psychol. Devel. Educat. 2, 7–11.

Zhang, X. W., Gu, C. H., and Ju, Y. C. (2001). A review of the research on the relationship between child bullying and personality (in Chinese). Psychol. Dynam. 3, 215–220.

Zhang, Y. X., Sun, X. J., Ding, Q., Chen, W., Niu, G. F., and Zhou, Z. K. (2016). The influence of children’s personality traits on loneliness: the mediating effect of friendship quality (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 24, 66–69.

Zhong, W. F., and Liu, H. (2013). The relationship between juvenile criminals’ self-concept, social support and family factors (in Chinese). Problem Juvenile Delinq. 02, 65–68.

Zhou, C. H., Chang, X. L., Sun, J. J., Wang, Y. T., and Yuan, L. (2019). A study on the relationship between bullying in primary and middle schools and Big Five personality (in Chinese). Talent 27, 6–9.

Zhou, H. Y., and Ding, Y. X. (2003). Research on self-concept of bullying children (in Chinese). Psychol. Explorat. 1, 59–62. doi: 10.1207/s15326934crj1601_6

Zhou, S. H., Li, S. Z., Zhang, Y. T., Li, R., and Peng, Q. Y. (2008). Research on the relationship between mental health and personality of junior high school students (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 16, 395–396+394.

Zych, I., Ttofi, M. M., and Farrington, D. P. (2019). Empathy and Callous-Unemotional Traits in Different Bullying Roles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma 20, 3–21. doi: 10.1177/1524838016683456

Keywords: school bullying, personality traits, loneliness, self-concept, adolescents

Citation: Zhang Y, Li Z, Tan Y, Zhang X, Zhao Q and Chen X (2021) The Influence of Personality Traits on School Bullying: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 12:650070. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.650070

Received: 06 January 2021; Accepted: 29 April 2021;

Published: 21 May 2021.

Edited by:

Megan Stubbs-Richardson, Social Science Research Center, Mississippi State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Matt DeLisi, Iowa State University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Zhang, Li, Tan, Zhang, Zhao and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zuoshan Li, NjQyNjYyMjEzQHFxLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.