- 1Wellbeing and Resilience Centre, Lifelong Health Theme, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 2Órama Institute for Mental Health and Wellbeing, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 3College of Nursing and Health Science, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 4College of Education, Psychology and Social Work, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 5Health Counselling and Disability Services, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Replicating or distilling information from psychological interventions reported in the scientific literature is hindered by inadequate reporting, despite the existence of various methodologies to guide study reporting and intervention development. This article provides an in-depth explanation of the scientific development process for a mental health intervention, and by doing so illustrates how intervention development methodologies can be used to improve development reporting standards of interventions. Intervention development was guided by the Intervention Mapping approach and the Theoretical Domains Framework. It relied on an extensive literature review, input from a multi-disciplinary group of stakeholders and the learnings from projects on similar psychological interventions. The developed programme, called the “Be Well Plan”, focuses on self-exploration to determine key motivators, resources and challenges to improve mental health outcomes. The programme contains an online assessment to build awareness about one’s mental health status. In combination with the exploration of different evidence-based mental health activities from various therapeutic backgrounds, the programme teaches individuals to create a personalised mental health and wellbeing plan. The use of best-practice intervention development frameworks and evidence-based behavioural change techniques aims to ensure optimal intervention impact, while reporting on the development process provides researchers and other stakeholders with an ability to scientifically interrogate and replicate similar psychological interventions.

Introduction

Psychological interventions, being activities or groups of activities aimed to change behaviours, feelings and emotional states (Hodges et al., 2011), come in many shapes and sizes. A popular delivery method is in the form of programmes consisting of several interacting components and procedures, which per definition makes them “complex interventions” (Moore et al., 2015). This complexity is often lost in academic publications, as articles for instance are bound to word limits or have a primary focus on presenting outcome data as opposed to theoretical rationale and methodological insights (O’Cathain et al., 2019). Despite various welcome initiatives such the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) the intervention literature typically lacks in-depth descriptions of psychological interventions and the way they were created (Pino et al., 2012; Candy et al., 2018).

These reporting challenges are problematic for the scientific method as they make it difficult to replicate interventions, interpret which underlying intervention components are effective and draw robust conclusions about how these interventions have been developed (Chalmers and Glasziou, 2009; Hoffmann et al., 2017). More importantly, these challenges are avoidable as robust intervention development methodologies already exist that can be used to scientifically describe the components of complex behavioural and psychological interventions (Michie et al., 2011b; Eldredge et al., 2016; Garba and Gadanya, 2017). Scientific articles that purely describe the development of interventions using such methodologies can mainly be found in research on health behaviours, including smoking (van Agteren et al., 2018b), nutrition (Rios et al., 2019), physical activity (Boekhout et al., 2017), AIDS (Wolfers et al., 2007), and oral hygiene (Scheerman et al., 2018) to name a few. Despite their potential merit, the application of similar methodologies has yet to receive traction in psychological science.

Rigour in reporting standards is particularly important for new and emerging scientific areas in gaining scientific credibility and facilitating replication. The last decades have seen the introduction of a range of new psychological interventions, as well as the re-purposing of existing interventions, specifically aimed at promoting mental wellbeing, as opposed to addressing mental disorder per se (Slade, 2010). Improving outcomes of mental wellbeing is a protective factor against the onset of mental illness (Keyes et al., 2010; Iasiello et al., 2019), aids in disease recovery and chronic disease self-management and is associated with improved health service utilisation (Lamers et al., 2012; Slade et al., 2017). Above all, feeling mentally well is an important outcome in its own right, for individuals, families, communities, and society (Diener and Seligman, 2018; Diener et al., 2018). As a result, psychological interventions are increasingly in demand by health organisations, educational providers, workforces, and governments looking at wellbeing initiatives. Considering this interest, the individual and societal benefits of improving wellbeing, and fair criticism that have been drawn toward the lack of rigour in wellbeing research (Heintzelman and Kushlev, 2020), it is important to adequately describe the development of any interventions aimed at improving outcomes of mental wellbeing (Diener, 2003; Gable and Haidt, 2005; Kristjánsson, 2012).

The aim of the current article is to be a case study that firstly describes the application of a rigorous intervention development framework, the Intervention Mapping (IM) approach (Eldredge et al., 2016), to guide development of a theory- and evidence-based mental health intervention, designed to be used with both clinical and non-clinical populations. Secondly, as a result, it aims to act as a case study on the complexity that underpins scientific mental health interventions, and the detail that needs to be considered when aiming to replicate or modify them.

Materials and Methods

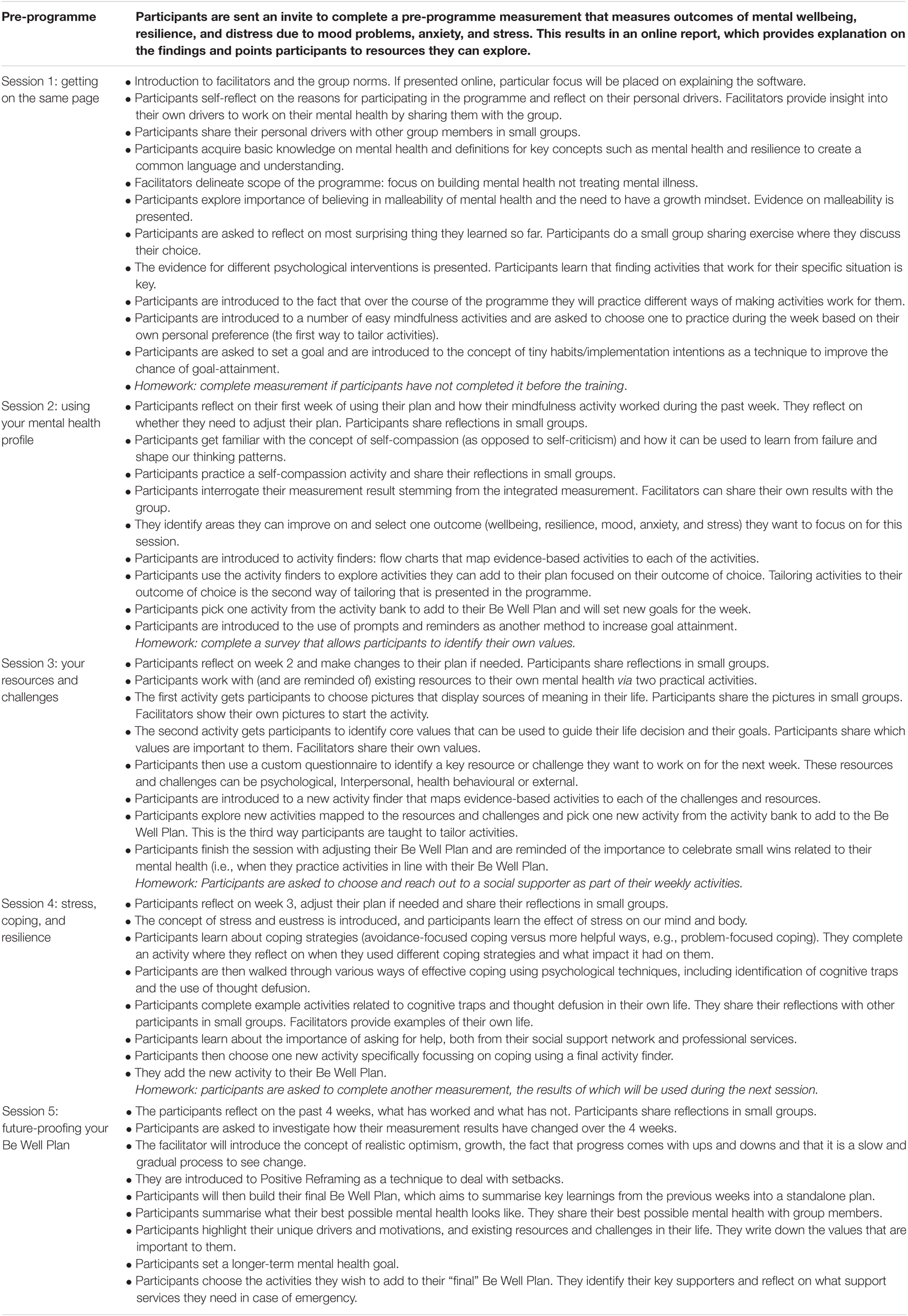

The IM approach guides intervention development in a series of six steps. This article follows the standard structure of the IM methodology. The methods below explain each of the four steps and how they were used for the development of the intervention in this article: the Be Well Plan. For a description of the methodology see Kok et al. (2016). Figure 1 visualises the methodology steps and its outputs at each stage, which are presented in the results below. The large bulk of programme development across the four steps was conducted by a small project team (JA, MI, KA, DF, and GF) who interacted with a larger multi-disciplinary project working group that among others included psychologists, counsellors, mental health researchers, and end-users, throughout the development life cycle. This group was crucial in informing and validating each of the IM steps, such as the exact objectives of the programme. The role for each of the members is described in more detail in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Figure 1. Visualisation of the Intervention Mapping process and the outputs at each of the steps covered in the intervention development methodology.

Step 1: Determine the Problem That Needs to Be Solved by the Intervention via a Thorough Needs Analysis

The first step of IM involved performing a needs analysis related to the problem that the programme aims to solve. The needs analysis focuses on determining the problem that needs to be changed and subsequently defining the exact scope of the intervention. The needs analysis firstly draws on an extensive study of the scientific literature on mental health and wellbeing interventions. Secondly, it is underpinned by findings and data (published and unpublished) from previous wellbeing studies our research group conducted across population groups including in the general community, within workforces such as health professionals, with older adults, carers, and disadvantaged youths (Raymond et al., 2018, 2019; van Agteren et al., 2018a; Bartholomaeus et al., 2019). All data that was being used to underpin the needs analysis was subject to ethics approvals issued by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (SBREC), project numbers (PN) 7834, 7891, 7350, 7358, 7221, 7218, and 8579.

The IM framework uses the PRECEDE-PROCEED model (Gielen et al., 2008) to summarise and structure the results of the needs analysis into an actionable logic model. In highly simplified terms, the model gets you to (1) determine the key problem that the needs analysis indicates one needs to solve, (2) the overarching behavioural and environmental outcomes (or targets) one needs to meet to improve the problem, and (3) defining the underlying determinants of those behavioural and environmental outcomes. An example could be, “people with problematic mental health (the problem), may not consistently use psychological activities in their day-to-day lives (the outcome/target) as they do not have enough knowledge (the determinant) of the benefits of using such activities.”

Rather than arbitrarily coming up with determinants that we wished to change, we relied on the Theoretical Domains Framework (Cane et al., 2012) to guide our choice. The TDF is a framework that synthesises 14 unique determinants (e.g., knowledge, skills, and beliefs) stemming from 33 behaviour change and implementation theories. It provides a comprehensive and intuitive theory-based overview of relevant behaviour change determinants that intervention developers can use. IM requires developers to prioritise and choose only the relevant TDF determinants by assigning which determinants (1) are actually related to the problem and (2) can actually be changed. An explanation for the choice of each determinant is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

The result of step 1 is a logic model of change that summarises the problem, the outcomes and the determinants, which will be used to underpin the intervention.

Step 2: Define the Objectives the Intervention Needs to Meet and What the Intervention Needs to Change to Meet Those Objectives

After determining the problem that needs to be addressed, IM continuous to delineate what needs to change to solve the problem. Firstly, each target area (e.g., the lack of participation in psychological activities) identified in the needs analysis were rewritten into desired behavioural and environmental outcomes (e.g., engaging in regular use of psychological activities). Secondly, these outcomes were subsequently broken into sub-objectives called performance objectives (e.g., demonstrates knowledge on how to improve mental health). Finally, these performance objectives were broken down further into so-called change objectives. These are very specific objectives that need to be achieved in order for the performance objective to be realised (e.g., increasing knowledge of malleability of mental health). A change objective consisted of linking performance objective with determinants from the Theoretical Domains Framework (e.g., knowledge, skill, and beliefs about capabilities). The final output of step 2 was a collection of matrices, so-called matrices of change, depicting each change objective per performance objective (placed in the rows) and determinant (placed in the columns).

Step 3: Select Behaviour Change Techniques and Practical Applications of Those Techniques That Will Be Used to Achieve the Change Objectives

In step 3, a new table is created by placing the change objectives on individual rows and matching them with evidence-based “behaviour change techniques” (BCTs) (Kok et al., 2016). BCTs are theoretical strategies (e.g., goal setting, modelling, and active learning) that have been empirically proven to be able to change individual behaviour. The IM framework comes with an extensive summary of BCTs and how they can be used to create impactful interventions. It gets programme developers to match their change objectives with individual BCTs, thereby aiming to improve the chance that actual behaviour and environmental change in line with the change objective will be achieved.

The final part of step 3 is translating the theoretical BCTs into so-called “practical applications,” referring to the proposed real-world application of each BCT. For example, to achieve the change objective “Demonstrating knowledge on malleability of mental health,” the programme draws on the BCT “active learning” which can be achieved via the “practical application” of showing an engaging video on epigenetic changes that can alter our mental health (Schiele et al., 2020). The result is a line-by-line itemised list (or blueprint) of practical applications that need to be incorporated into the programme design in step 4.

Step 4: Design and Develop the Actual Intervention Components Based of the Practical Applications Identified in the Previous Step

In step 4, the programme designers created the actual intervention based on the blueprint established in step 3. This process was guided via various project team meetings. A subgroup of project team members (JA, MI, KA, DF, LW, and GF) created a programme delivery framework, outlining the proposed intervention sessions, their underpinning rationale and the delivery format. This framework was evaluated and approved by the larger multi-disciplinary project team that included end-users over a series of meetings. The subgroup continued by creating a detailed narrative for the programme, which was subsequently translated into an interactive programme. The narrative and programme content is presented in the results below.

After developing the first iteration of the programme, two small-scale in-person test runs with university students (n = 30) and colleagues of the project team members (n = 7) were conducted by JA, MI, KA, GF, and AH. Feedback from these test runs was used to iterate the programme delivery, not to determine impact on outcomes (i.e., they were test runs not evaluation studies). After iteration, each of the five session sessions were recorded on video and the programme was subsequently tested in an online delivery format, i.e., delivered via video conferencing software, resulting in the programme presented in this manuscript.

Steps 5 and 6: Adoption, Implementation, and Evaluation Plans

After finishing the design and development of the intervention, IM concludes with two additional steps, the development of an adoption and implementation plan (step 5) as well as an evaluation plan (step 6). These two steps are outside the scope of this article, as the aim here is to describe the development and design process. The actual evaluation of the programme on outcomes will be covered in subsequent publications, including a pre-post pilot study in university students and general community members (n = 89; van Agteren et al., 2021a) and a randomised controlled study in university students. A brief description of the evaluation approach is provided in the discussion of this manuscript.

Results

Step 1: The Needs Analysis of the Be Well Plan Programme

The results from the needs analysis are presented in a narrative format, combining the findings from the literature review and interrogation of qualitative and quantitative data from previous projects on wellbeing interventions our project team conducted. The needs analysis for this specific programme is structured around four distinct themes, which are outlined below. Supporting material underpinning the needs analysis can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Theme 1: There Is a Need for Mental Health Interventions to Incorporate a Specific Focus on Positive and Adaptive States, in Addition to Taking Psychological Distress Into Account

Psychological interventions for mental health are often thought of to be synonymous to interventions aimed at treating or preventing mental illness or psychological distress. This is reflected in research on psychological interventions such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness, with studies largely focussing on their effectiveness in improving outcomes of illness and psychological distress (Hofmann et al., 2010, 2012; Swain et al., 2013). There is however general agreement that optimal mental health does not equate to a mere absence of symptoms of mental illness as it also requires participants to demonstrate high levels of mental wellbeing, e.g., finding meaning in life, working on positive relationships, and building positive emotions (Jahoda, 1958; Smith, 1959; Fontana et al., 1980; Wilkinson and Walford, 1998; Greenspoon and Saklofske, 2001; Keyes, 2003, 2005; Suldo and Shaffer, 2008). A significant body of research has found that mental wellbeing should not be seen as the mere opposite of mental illness (Iasiello et al., 2020). Studies in Western and non-Western populations demonstrate that people who exhibit psychological distress or show symptoms of mental illness have varying levels of mental wellbeing (Peter et al., 2011; Seow et al., 2016; Bariola et al., 2017; Teismann et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2017).

There are numerous ways of building outcomes of mental wellbeing, including spending time in nature (Howell et al., 2011; Korpela et al., 2016; Passmore and Holder, 2017), being physically active (Penedo and Dahn, 2005; Windle, 2014), doing yoga (Ivtzan and Papantoniou, 2014; Sharma et al., 2017), and spending more time engaging in social relationships (Keyes, 1998; Gallagher and Vella-Brodrick, 2008) among others. Psychological interventions such as CBT, ACT and mindfulness in addition to be effective for outcomes of mental illness (Hofmann et al., 2012; Öst, 2014; Goldberg et al., 2018) have joined this list in being able to improve outcomes of mental wellbeing, in addition to being effective for distress. A recent systematic review conducted by authors of the current article examined 419 studies (n = 53,288 included in meta-analysis) which clearly demonstrated their impact in both healthy populations and populations with mental illness or physical illness (van Agteren et al., 2021b). The significant findings were dependent on the specific target population (e.g., clinical versus non-clinical populations) and other moderators, most notably intervention intensity.

Psychological interventions are not simply beneficial for improving mental health outcomes in the moment. For instance, by improving outcomes of wellbeing, they can both increase the likelihood of recovery from mental illness or can prevent the onset of illness in the future (Keyes et al., 2010; Wood and Joseph, 2010; Grant et al., 2013; Lamers et al., 2015; Iasiello et al., 2019). By focussing on improving wellbeing it makes them a viable avenue for individuals seeking to reduce symptoms of distress (Gilbert, 2012; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2019) and to build resilience to future adversity (Fritz et al., 2018). In other words, by teaching psychological skills that take future distress and wellbeing into account, participants can be taught techniques that aim to help them withstand adversity or stress (i.e., cope with) without succumbing to more serious mental health problems (Davydov et al., 2010; Harms et al., 2018). A deliberate focus on developing this resilience, or in other words improving adaptative states, could strengthen the impact of mental health interventions, for those with and without current distress (Roy et al., 2007; Fritz et al., 2018).

Theme 2: There Is a Need for Mental Health Interventions to Target Malleable Non-psychological Determinants of Mental Health in Psychological Interventions

Our mental health is not simply determined by our thinking patterns, but rather is influenced by a myriad of bio-psycho-social influences. While not all these influences are within the control of behavioural or psychological interventions, or feasible in light of the focus for our intervention, the team determined that two aspects were. Firstly, stimulating positive change related to our physical health will be beneficial to our mental health, as both are intrinsically linked, which is demonstrated by a considerable body of scientific evidence on the importance of health promotive factors such as physical activity, nutrition and sleep, all of which can be positively addressed using behavioural interventions (Valois et al., 2004; Penedo and Dahn, 2005; Chu and Richdale, 2009; Deslandes et al., 2009; Oddy et al., 2009; Rethorst et al., 2009; Nanri et al., 2010; Gradisar et al., 2011; Rienks et al., 2013; Bernert et al., 2014; Dalton and Logomarsino, 2014; Jacka et al., 2015). Inclusion of, at minimum, rudimentary techniques that could be used to stimulate positive health behaviours was deemed necessary for our intervention. Secondly, the training needed to incorporate elements of our social environment into the intervention. Stimulating small positive change in our social environment can lead to improved mental health (Kawachi and Berkman, 2001; Santini et al., 2015; Verduyn et al., 2017). Similarly, feeling isolated and lonely exerts strong negative influence on wellbeing and mental health (Arslan, 2018; Wang et al., 2018).

Theme 3: Personalising the Mental Health Intervention to Match Individual Participant Needs Will Drive Impact and Is Feasible in Scalable Intervention Formats

In-person psychological mental health interventions outside the clinical setting tend to come in predictable formats. They often are delivered in groups (as this cost-effective), are delivered over multiple sessions, with content tending to come from (a combination of compatible) therapeutic paradigms. The content typically tends to be similar for all participants, despite the fact that personalising or tailoring interventions to individual needs might improve outcomes of interventions or improve the feasibility of its implementation (Norcross and Wampold, 2011). To improve tailoring, intervention developers often adjust the content of interventions to fit specific target populations such as students, older adults, or workforces (Waters, 2011; Shiralkar et al., 2013; Proyer et al., 2014; Robertson et al., 2015). While tailoring to group-needs is a right step in the direction, it is still removed from addressing the needs and preferences of individuals within each population group (Schork, 2015).

One potential way to achieve tailoring to individual needs is to allow participants to work on specific resources and barriers that are relevant to their unique lives. Rather than utilising an approach based on a singular therapeutic model (e.g., CBT versus ACT) the intervention could focus on modelling the approach by recent innovations such as process-based interventions; the intervention could incorporate a range of effective intervention techniques that target known “theoretically derived and empirically supported processes that are responsible for positive treatment change” rather than focussing on a specific illness, medical diagnosis or set therapeutic paradigm (Hayes and Hofmann, 2018; Hofmann and Hayes, 2019). These techniques can come from varying evidence-based interventions, for instance those identified in our systematic review on psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing (van Agteren et al., 2021b).

By facilitating tailoring to individual circumstances engagement with the intervention can be stimulated, as participants in mental health training offerings may resonate differently to different components of an intervention. This is reflected in responses to training feedback in previous projects the team conducted, see Supplementary Appendix 1. The training delivered in these projects consisted of skills stemming from CBT, mindfulness techniques and positive psychology. At the end of the training participants voices different preferences for different skills, with an eclectic response pattern noted. Allowing participants to experiment with different evidence-based techniques in an effective manner has furthermore become much more within reach with the rise of technology (Clough and Casey, 2015; Dinesen et al., 2016; Naslund et al., 2016; Naslund, 2017; Berrouiguet et al., 2018). For instance, technology can help guide activity recommendations based on an individual’s response to scientific questionnaires for mental health and wellbeing. This can allow a participant to experiment with different techniques, without the requirement for a trainer or therapist to guide choice of activities, ultimately facilitating them to independently form a personalised strategy for good mental health and wellbeing.

Theme 4: In Order to Facilitate Lasting Change, There Is a Need for Mental Health Interventions to Leverage a Focus on Behaviour Change

In order for mental health interventions to “stick,” individual participants need to change their behaviour, aligned to the goals of the intervention (Kok et al., 2016). Simply providing activities to build resources and remove challenges to good mental health may not be sufficient, for example, due to a discrepancy between intention to change behaviour and actual behaviour change (Atkins et al., 2017). Reliance on the IM approach stimulated an explicit focus on behaviour change, ultimately asking intervention developers to select key underpinning determinants that are related to the problem behaviour.

Interventions can broach this in numerous ways, depending on the determinants they consider to be the focus for the intervention. As part of the needs analysis, the project team focused on several determinants that were (1) deemed important for mental health and (2) were considered to be malleable and within reach of the current intervention. For instance, teaching skills to deal with stressors, adversity or negative social influence aids in improving the chance of engaging in wellbeing activities (Fritz et al., 2018). Knowledge has been found to be one of the essential ingredients for psychological skills to be developed (Jorm, 2012; Oades, 2017), and self-efficacy helps in the execution of skills (Leamy et al., 2011; Trompetter et al., 2017). Often there is resistance or stigma toward mental health and wellbeing activities (Clement et al., 2015; Thornicroft et al., 2016), indicating the need to focus on changing beliefs about the effectiveness of wellbeing behaviours and beliefs about the consequences of implementing those behaviours (Sheeran et al., 2016). Finally, goal-setting aids in strategy formation and achievement of physical health improvements as well as behavioural regulation via self-monitoring (Wollburg and Braukhaus, 2010; Michie et al., 2011a). A further justification for why the project team chose these determinants over others can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

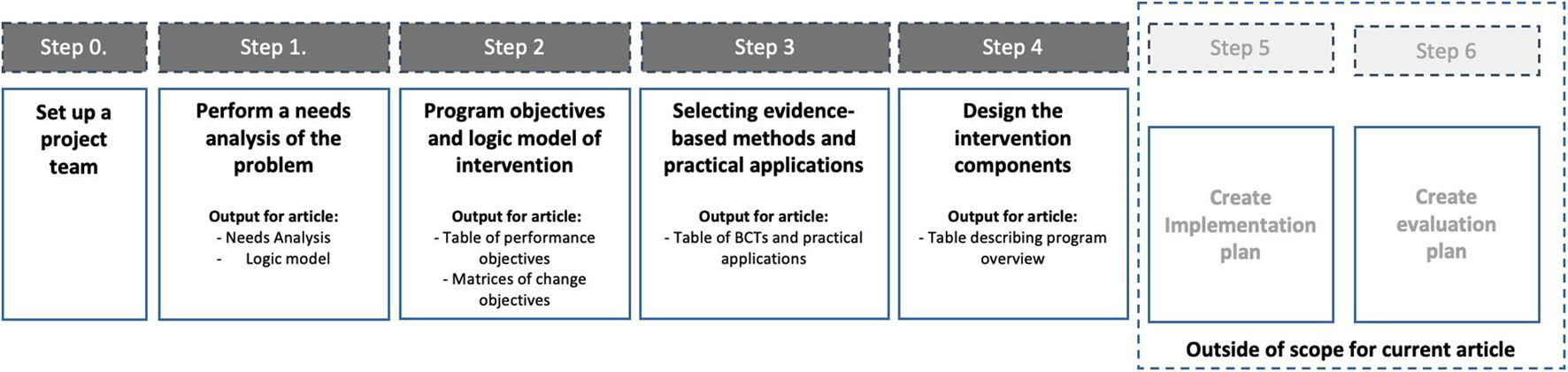

Use the Needs Analysis to Craft a Visual Logic Model for the Intervention

The project team subsequently set out to construct a logic model for the intervention based on the findings from the needs analysis, see Figure 2. The team followed the general structure for logic models as set out in IM and the PRECEDE-PROCEED model (Green and Kreuter, 1999). The key focus for the intervention was to help participants promote their mental health, pointing to the need for an intervention that would be able to target positive, adaptive, and distress states. The needs analysis pointed to the desire for an intervention that allowed participants to develop a personalised mental health and wellbeing strategy or “plan,” allowing participants to take their unique characteristics and health status into account. The key objective was to get participants to change their behaviour by actively engaging in evidence-based activities. These activities firstly should allow individuals to build or leverage resources that can promote mental health in the now and secondly build resources that can help the individual cope with stressors in the future. It should thirdly aim to engage the social environment as a mechanism to support the individual. To achieve the objective, and ultimately behaviour change, the intervention would target specific behaviour change determinants that were derived from the Theoretical Domains Framework Domains (Atkins et al., 2017), including knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities and consequences, goals, social influences, and behavioural regulation.

Figure 2. Simplified overview of the needs analysis for the Be Well Plan. The specific explanatory role of variables (e.g., mediating or moderating) is not taken into account in this figure. The model merely serves to outline the variability of behaviours and determinants that influence wellbeing and resilience using the PRECEDE-PROCEED model outline. Determinants are based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

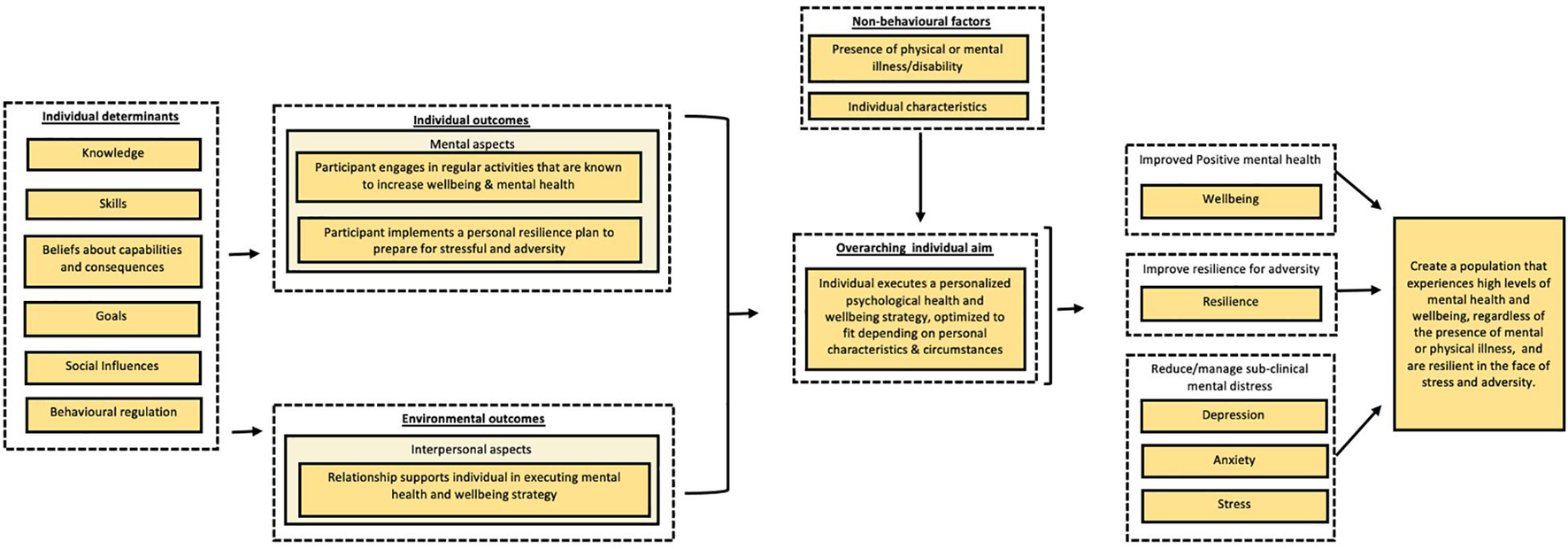

Step 2: Definition of Programme Objectives

Step 2 required the project team to create programme outcomes based on the needs analysis and the logic model. The outcomes were: participant engages in regular activities that are known to increase wellbeing and mental health, participant implements a personal resilience plan to prepare for stressful periods and adversity, participant engages relationship supports in executing their mental health and wellbeing strategy. These outcomes were further specified into performance objectives, see Table 1. Change objectives were formulated for each of the performance objectives in line with the chosen TDF determinants mentioned earlier. All matrices of change can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Table 1. Behavioural and environmental outcomes, and performance objectives (PO) for Complete Mental Health.

Step 3: Evidence-Based Behaviour Change Techniques and Practical Applications

The change objectives developed for each of the performance objectives in step 2 were placed in a new table. In step 3 these change objectives were matched to evidence-based BCT’s (10) in Table 2. The table mentions each specific BCT as well as the psychological theories they come from. For each BCT, the programme team then constructed practical applications that were to be implemented in the programme. The result is a line-by-line theoretical blueprint for the programme.

Table 2. Combined table for behavioural outcome 1 (engages in regular activities that are known to increase wellbeing and mental health of the individual), behavioural outcome 2 (practices resilience activities to prepare for times of stress and adversity), and environmental outcome 1 (relationship supports individual in striving for more wellbeing and resilience).

Step 4: Design of the Programme

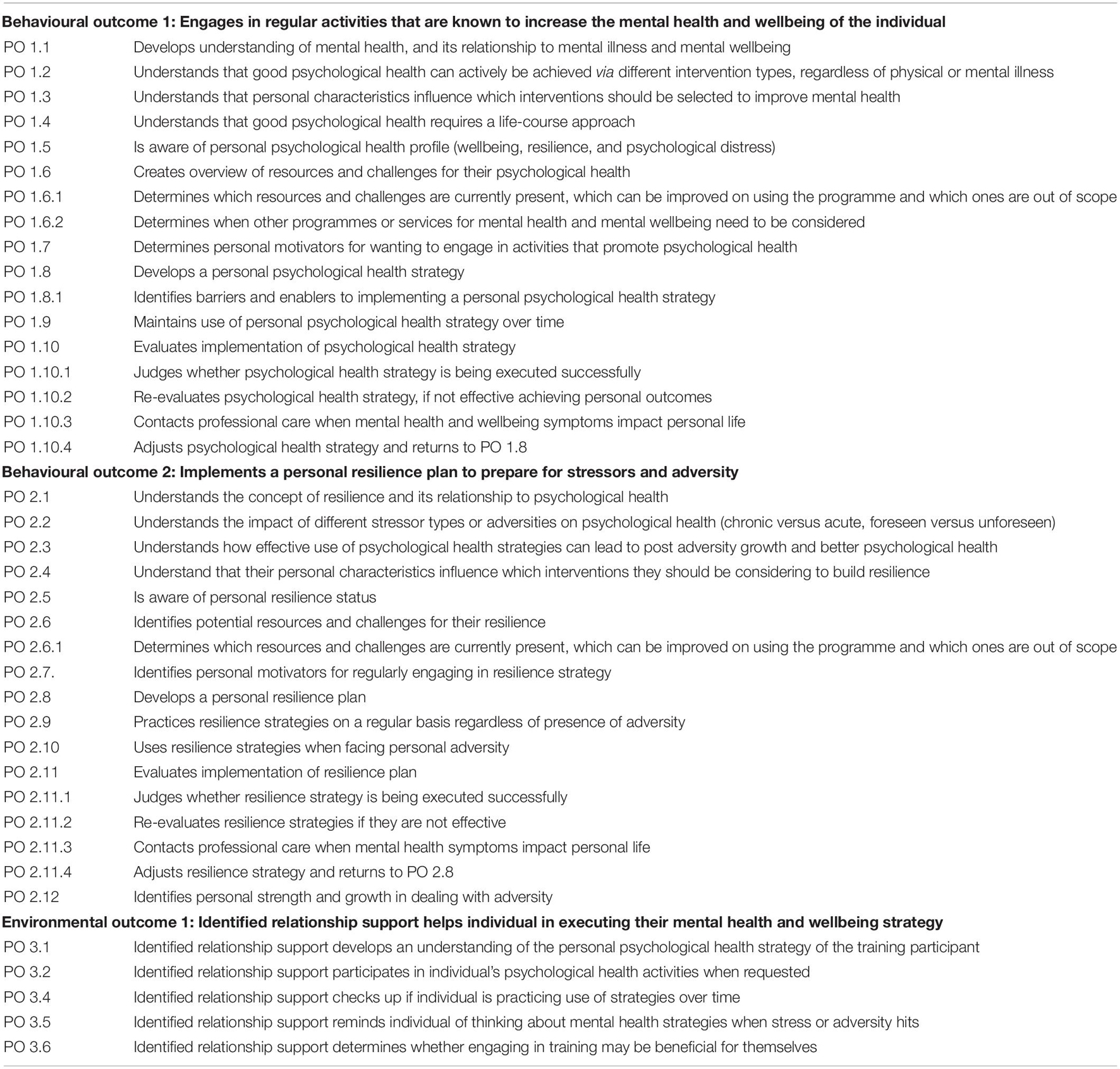

Programme Content

The Be Well Plan programme aims to teach participants to start developing their own tailored wellbeing plan. The standard programme is delivered over 5 weeks, allowing participants to develop, implement, and experiment with activities in their plan to suit their specific situation. Delivering sessions over several weeks was hypothesised to lead to larger effects than a short but intensive programme, as research shows that wellbeing programmes are more efficacious when delivered over a longer period of time (Bolier et al., 2013). While this contradicts with for instance brief intensive exposure literature (Öst and Ollendick, 2017) which focuses more on distinct situations rather than the development of more complex behavioural repertoires, it is in line with evidence from related areas such as memory formation and skill acquisition, which usually take time and practice to consolidate (Eichenbaum, 2011). Each session builds on the other, and gradually introduces more complexity. An overview of the each of the five sessions is provided in Table 3. Examples of the programme content described in the table can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Each session relies on four key components. Firstly, in each session participants reflect on their personal situation and motivations that are related to their mental health. The participant is asked to perform various self-reflection exercises, for instance reflecting on specific drivers to work on their mental health (session 1), determining which mental health outcomes (e.g., mood, anxiety, and wellbeing) they want to work on (session 2), identifying existing resources and challenges to their wellbeing (session 3), determining which social supporters are present within their life (session 4). In the final session participants reflect on the best version of themselves related to mental health and wellbeing. In other words, the participant is stimulated to create a better understanding of their “self” (Kyrios, 2016) which in turn is used to help determine which psychological activities may be most relevant for them implement within their day-to-day life.

Second, each session introduces participants to at least one psychological concept that is considered to be beneficial or “helpful” to building mental health. These include Mindfulness in session 1 (Shapiro et al., 2006), Self-Compassion in session 2 (Neff et al., 2007), Values and Strengths in session 3 (Dahlsgaard et al., 2005), Psychological Flexibility in session 4 (Kashdan and Rottenberg, 2010), and Realistic Optimism in session 5 (Schneider, 2001). The use of these techniques are contrasted with less helpful psychological processes, biases or patterns (e.g., self-compassion versus excessive self-criticism). The aim was to get participants to experience helpful and practical activities related to the psychological concepts, the aim was not to provide a deep dive into each concept. Activities from these specific approaches were chosen as they underpin leading therapeutic models (e.g., CBT, ACT, etc.), are supported by a robust evidence-base, and highlight the malleability of mental health. By teaching these techniques the programme intends to improve participant’s confidence in positively changing their mental health. While the Be Well Plan holds activities from various therapeutic streams other than the ones mentioned above, and aims to stimulate participants to experiment with different activities, highlighting a minimum set of concepts aimed to ensure that participants who were not motivated to experiment would still experience a variety of different activities.

Thirdly participants use the learning from the self-reflection exercises to find different evidence-based psychological activities to implement in their everyday life. The evidence-based activities are collated in an “activity bank,” which were identified by investigating the literature on wellbeing interventions with a systematic review and meta-analysis (van Agteren et al., 2021b). The systematic review identified which intervention types (e.g., CBT, ACT, and positive psychology) were impactful at changing mental wellbeing. The author team then interrogated articles contributing to impactful intervention types and incorporated activities that were included in multiple studies (e.g., though defusion for ACT). Activities were added regardless of the therapeutic or theoretical background, see Supplementary Appendix 1 for a list of the activities. This resulted in a programme that was “theory-agnostic”: activities were chosen based on their demonstrated effectiveness to improve mental wellbeing, rather than their therapeutic background.

Activities can be practiced in two ways, common and personalised. Common activities are matched to specific self-reflection exercises and practised by each participant over the course of the five sessions. For instance, after exploring the topic of self-criticism, every participants completes a self-compassion exercise which asks them to “treat yourself as you would treat your friends” (Neff et al., 2007). Personalised activities are activities that are suggested based on individual answers to the self-reflection exercises. These are therefore specific to the participant, meaning that each participant will use a different set of activities in the programme. Over the programme, the participant tries a different way to personalise the activities using so-called activity finders, which are visual aids that link activities to specific topics. In session 1 participants get taught that activities come in different formats, asking participants to try out different formats of mindfulness, e.g., mindful walking, body scan, or deep breathing (Keng et al., 2011). In session 2 participants match activities to a mental health outcome they want to work on, in session 3 they select resources to work on (e.g., self-esteem) and in session 4 they select activities based on a coping style they wish to use. The role of the facilitator throughout the sessions is to model how to use the activity finders, allowing participants to master different ways to tailor activities to their needs.

The fourth principle taught in each session is the basics behind planning and habit formation. At the end of each session, participants are required to choose at least one new activity to practice during the week. Once an activity is selected, participants are guided to refine and personalise the implementation of that activity by developing explicit statements on when and where activities are practiced. The participant first sets a clear goal related to the activity they will practice during the week, which aims to help motivate participants to execute a behaviour. The participant is then asked to form a habit statement, which is derived from the work of Fogg (2019) on “Tiny Habits” and the concept of implementation intentions (Gollwitzer and Sheeran, 2006). The development of a personalised plan and a focus on implementation means this process is couched in a language of experimentation, where participants try out multiple activities and adjust their plan based on trial-and-error, as they determine which activities work for them, both from a likeability perspective and from their ability to improve the outcome they decided to work on (Proyer et al., 2015). Ultimately this means that each participant will have a different plan consisting of different evidence-based techniques and activities at the end of the programme, matched to their personal situation.

Delivery Format and Style

The standard programme was designed to be delivered over five sessions, in-person and online. The programme relies on facilitators using presenter slides, an extensive workbook and supporting video material. The Be Well Plan programme was designed to be deliverable in various formats. First and foremost, it was designed to be delivered as group-based training, where participants interact with one another and share reflections, led by a facilitator. The proposed group size is about 25–30 participants, to balance engagement, feelings of social support, and logistics with cost-effective implementation. The activities were designed to be conducted in pairs and small groups (size ranging between 2 and 5 people) providing flexibility in the way it may be implemented, either in small classrooms or larger settings. Secondly, the programme can be delivered online via video conferencing technology (Taylor et al., 2011), which can facilitate all individual components including the sharing exercise, e.g., via breakout rooms in conferencing software.

The programme was designed to be delivered without the clear requirement of clinical staff, with the programme utilising a Train-the-Trainer methodology to ensure reach and scalability (Pearce et al., 2012). The facilitators are trained over the course of several week, with a minimum total training time of 26 h. Facilitators in the programme model each of the common activities that are practiced in sessions. This involves facilitators walking participants through the activity, sharing their own experiences of the activity and how they have integrated it into their life. This strategy aims to facilitate a connection between facilitators and participants, in alignment with the importance of the therapeutic relationship in psychological interventions (Clarkson, 2003).

Finally, the programme has an active integration with technology. At the start of the programme participants fill out an online mental health measurement looking at outcomes of mental wellbeing, resilience, and distress, which results in a tailored report. Individual reports serve two purposes: improving the wellbeing literacy (Green et al., 2011) of participants, as well as providing a sense of agency over mental health changes (Schroder et al., 2017). Participants complete the assessment at the start and the end of the programme, allowing them to track their outcomes of interest and “test” whether their personalised strategy has had the desired effect. They also use the results to select an outcome they want to work on during session 2.

Discussion

This article outlines the use of an intervention development framework to guide the design and development of a mental health intervention. Significant detail about the development process and the intervention itself is provided to allow transparency for end-users, researchers, practitioners and policy makers who may wish to access, evaluate or replicate the programme. At the same time, it serves to illustrate a methodology that allows for improving the reporting of development and design processes for psychological interventions. Firstly, we will discuss the Be Well Plan in the context of other existing mental health interventions. Secondly, we will discuss the implications of using this reporting approach which provides an extensive descriptions of intervention methodology and design, and compare its strengths and limitations to other approaches.

Although a plethora of mental health interventions exist, the needs analysis that underpins the Be Well Plan led it to be designed differently to most other interventions in various ways, e.g., the need for a focus beyond mental illness, the need to personalise, and the need to focus on behaviour change. Firstly, most existing mental health interventions are focused on treating mental illness (Das et al., 2016) and not necessarily building or promoting mental health (Keyes, 2007). Simply relying on techniques designed to treat symptoms of illness could be limiting for a mental health promotion intervention that aimed to be suitable for clinical and non-clinical populations, considering the existence of differential antecedents for mental illness and wellbeing (Kinderman et al., 2015). For example, simply extrapolating techniques that were developed to address maladaptive thought patterns might only be relevant for a proportion of participants, whose maladaptive thoughts patterns are the cause of their challenges, rather than for instance a lack of purpose or positive social relations. Similarly, traditional “wellbeing” interventions such as positive psychology interventions are typically designed to target positive constructs, and do not necessarily address the potential maladaptive antecedents of poor mental health (Seligman et al., 2005). A notable exception can be found in ACT-based interventions as they address both states (Fledderus et al., 2012), although they are still typically applied in the context of mental illness rather than promotion of wellbeing (Doorley et al., 2020).

The Be Well Plan is “theory agnostic” and explicitly deviates from existing interventions that are underpinned by a set therapeutic paradigms. A broad variety of interventions based on CBT, ACT or positive psychology exist (Hofmann et al., 2012; Öst, 2014; Carr et al., 2020). While they have demonstrated, on average, significant impacts on mental health outcomes, there is no decisive evidence to suggest that these are the only valid approaches to improving mental health, particularly when the focus is on mental health promotion and not simply the treatment of mental illness (Slade, 2009). Rather, the Be Well Plan includes a set of empirically derived psychological activities from across paradigms targetting various antecedent, with which the participant experiments with, drawing a parallel with process-based therapies (Hofmann and Hayes, 2019). Future studies that focus on outcome evaluation are planned to validate whether this approach will lead to cause the hypothesised positive impact on mental health outcomes.

Furthermore, a key aim for the programme is to create lasting behavioural change for participants, using guidance from behaviour change taxonomies (Kok et al., 2016). Instead of providing participants with activities and leaving it up to participants to decide which activities can be used as part of their life journey to good mental health, the programme encourages participants to match and experiment with activities to their needs, which may be driven by distress or illness, by wellbeing needs or by both. This approach is in line with a personal recovery approach to mental health promotion, which is captured by Anthony (1993) as “a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life, even within the limitations caused by illness.” The focus of the intervention is to guide participants to develop a sustainable wellbeing plan and provide them with tools to monitor their mental health over the life-course. This required the integration with an online assessment that facilitated real-time reporting. While tracking of change as a result of interventions is common in e-health solutions, particularly those focussing on Ecological Momentary Assessment (Shiffman et al., 2008), the integration of reporting capability in group-based interventions is uncommon. It follows the growth in popularity of outcome monitoring (Carlier et al., 2012; Boswell et al., 2015), where health practitioners are able to monitor treatment progress, and expands this by providing this same real-time capability to participants; a principle which is not typically seen in group-based programmes. This fundamentally aims to provide self-agency and gives the participant ownership over and accountability on their own mental health, now and in the future (Clarke et al., 2014).

Detailed outcome evaluation will be needed to determine the impact of the approach chosen in the Be Well Plan. Two studies have, at time of writing this manuscript, been completed, with further studies underway. The first completed study was an uncontrolled intervention study aimed at determining the initial impact of the intervention, finding significant improvements in outcomes of wellbeing, resilience, and psychological distress, most notably for those with more problematic mental health scores at baseline (van Agteren et al., 2021a). Preliminary findings of a randomised controlled study are replicating the positive findings of the first study, with a manuscript currently being prepared. The Be Well Plan evaluation is ongoing, with future studies focussing on investigating who benefits most from the intervention and investigating the impact of different formats of the Be Well Plan (e.g., face-to-face versus online) as well as its longer term impact, including comparing its impact to other psychological intervention types.

Improving the Reporting Standards for Mental Health Intervention Research

The article aimed to provide a foundation for anyone who seeks more detailed information about the Be Well Plan’s scientific foundations. Using an extensive intervention development process such as IM to document intervention design allows for detailed replication of the theoretical approach to the programme. By doing so, IM provides a specific methodology to improve attempts at reproducibility and replicability, following other positive developments in reporting standards for interventions and research. One example of such a development is the more frequent use of checklists such as the TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al., 2014). While TIDieR asks detailed questions regarding theoretical underpinnings, materials, procedures, tailoring, and iterations, it lacks a focus on describing the individual detailed components of the intervention such as the one reported in Table 2. Merely requesting researchers to explain that their intervention was based on for instance CBT-based principles or the Theory of Planned Behaviour does not provide sufficient details about the exact design principle of intervention components. A more detailed approach, via the use of taxonomies and ontologies to break down intervention components into active building blocks, is becoming more frequent (Larsen et al., 2017). The development of matrices of change, use of BCTs and guidance from the TDF provides an in-depth explanation of each component of the intervention, which can provide an extra safeguard at achieving intervention impact.

The use of IM or similar approaches such as the Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al., 2011b) also protects against a limitation of reporting checklists. These checklists are often used after the intervention has been designed, even if they were supposed to be used to guide design and studies. By using intervention development frameworks, the exact steps of the development process are captured throughout the entire project (Eldredge et al., 2016). This extensive process does come with its own limitations (Peters et al., 2015), including their requirement of resources. This ultimately also influenced the way the Be Well Plan was developed as it mainly on a small “core” group of contributors (JA, MI, GF, and KA) who guided the large majority of the development work, while the larger multi-disciplinary group provided input at half a dozen meetings and at key touch points. This was mainly the result of practical constraints (e.g., availability to contribute in-kind on top of existing workloads) and on lack of familiarity with the process, which poses a general limitation to methods such as IM (Eldredge et al., 2016). If programmes require rapid development with limited resources, using the current framework might at first glance not be favoured over a more pragmatic approach. The ultimate effectiveness of programmes that are designed, developed and implemented within short periods of time without adequate methodological considerations, may however be suboptimal in their ability to change outcomes and limit our ability to advance psychological science and improve mental health research. Adoption of rigorous development methodologies and investing resources in their use, such as is demonstrated in the case of the Be Well Plan, may be a way to counter this, pushing us another right step in the direction of scientific rigour in psychological intervention research (Prager et al., 2019).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by underpinning data stems from a variety of studies approved by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, project numbers (PN) 7834, 7891, 7350, 7358, 7221, 7218, and 8579. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JA and MI: project methodology, needs analysis, programme objectives, theoretical framework for programme, programme material development, and manuscript write-up. KA: project methodology, programme objectives, theoretical framework for programme, programme material development, and manuscript write-up. DF: programme objectives, theoretical framework for programme, and manuscript write-up. GF, LW, and AH: programme objectives, theoretical framework for programme, programme material development, and manuscript write-up. MK: project methodology, guidance of process and clinical input, and manuscript write-up. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Be Well Plan was in part funded by a philanthropic contribution by the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute which employs JA and MI, receives financial compensation from providing the Be Well Plan to organisations and the community.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the stakeholder group participants including Monique Newberry, Marissa Carey, Kim Seow, Stuart Freebairn, Michael Musker, Laura Lo, Jonathan Bartholomaeus, Emma Steains, Karen Reilly, Alison Jones, Jodie Zada, Kate Ridley, Renae Summers, Martin Evans, Yukiya Wake, Louise Roberts, Vanessa Ryan, and Bree Scharber. The authors would also like to acknowledge the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation in helping to support the development of the Be Well Plan.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648678/full#supplementary-material

References

Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16: 11.

Arslan, G. (2018). Social exclusion, social support and psychological wellbeing at school: a study of mediation and moderation effect. Child Indic. Res. 11, 897–918. doi: 10.1007/s12187-017-9451-1

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., et al. (2017). A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 12:77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Bariola, E., Lyons, A., and Lucke, J. (2017). Flourishing among sexual minority individuals: application of the dual continuum model of mental health in a sample of lesbians and gay men. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 4, 43–53. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000210

Bartholomaeus, J., Van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., and Jarden, A. (2019). Positive ageing: the impact of a community wellbeing program for older adults. Clin. Gerontol. 42, 377–386. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2018.1561582

Bernert, R. A., Turvey, C. L., Conwell, Y., and Joiner, T. E. (2014). Association of poor subjective sleep quality with risk for death by suicide during a 10-year period: a longitudinal, population-based study of late life. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 1129–1137. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1126

Berrouiguet, S., Perez-Rodriguez, M. M., Larsen, M., Baca-García, E., Courtet, P., and Oquendo, M. (2018). From eHealth to iHealth: transition to participatory and personalized medicine in mental health. J. Med. Internet Res. 20:e2. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7412

Boekhout, J. M., Peels, D. A., Berendsen, B. A. J., Bolman, C. A. W., and Lechner, L. (2017). An eHealth intervention to promote physical activity and social network of single, chronically impaired older adults: adaptation of an existing intervention using intervention mapping. JMIR Res. Protoc. 6:e230. doi: 10.2196/resprot.8093

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Boswell, J. F., Kraus, D. R., Miller, S. D., and Lambert, M. J. (2015). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychother. Res. 25, 6–19. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.817696

Candy, B., Vickerstaff, V., Jones, L., and King, M. (2018). Description of complex interventions: analysis of changes in reporting in randomised trials since 2002. Trials 19:110. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2503-0

Cane, J., O’Connor, D., and Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. 7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

Carlier, I. V. E., Meuldijk, D., Van Vliet, I. M., Van Fenema, E., Van der Wee, N. J. A., and Zitman, F. G. (2012). Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 18, 104–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

Chalmers, I., and Glasziou, P. (2009). Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 374, 86–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9

Chu, J., and Richdale, A. L. (2009). Sleep quality and psychological wellbeing in mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 30, 1512–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.007

Clarke, J., Proudfoot, J., Birch, M.-R., Whitton, A. E., Parker, G., Manicavasagar, V., et al. (2014). Effects of mental health self-efficacy on outcomes of a mobile phone and web intervention for mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety and stress: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 14:272. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0272-1

Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., et al. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 45, 11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129

Clough, B. A., and Casey, L. M. (2015). The smart therapist: a look to the future of smartphones and mHealth technologies in psychotherapy. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 46:147. doi: 10.1037/pro0000011

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared virtue: the convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 9, 203–213. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.203

Dalton, A. G., and Logomarsino, J. V. (2014). The relationship between dietary intake and the six dimensions of wellness in older adults. Int. J. Wellbeing 4, 45–99. doi: 10.5502/ijw.4i2.4

Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., et al. (2016). Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J. Adolesc. Health 59, S49–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

Davydov, D. M., Stewart, R., Ritchie, K., and Chaudieu, I. (2010). Resilience and mental health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 479–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003

Deslandes, A., Moraes, H., Ferreira, C., Veiga, H., Silveira, H., Mouta, R., et al. (2009). Exercise and mental health: many reasons to move. Neuropsychobiology 59, 191–198. doi: 10.1159/000223730

Diener, E. (2003). What is positive about positive psychology: the curmudgeon and Pollyanna. Psychol. Inq. 14, 115–120.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., and Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

Diener, E., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). Beyond money: progress on an economy of well-being. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 171–175. doi: 10.1177/1745691616689467

Dinesen, B., Nonnecke, B., Lindeman, D., Toft, E., Kidholm, K., Jethwani, K., et al. (2016). Personalized telehealth in the future: a global research agenda. J. Med. Internet Res. 18:e53. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5257

Doorley, J. D., Goodman, F. R., Kelso, K. C., and Kashdan, T. B. (2020). Psychological flexibility: What we know, what we do not know, and what we think we know. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 14, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12566

Eichenbaum, H. (2011). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195141740.001.0001

Eldredge, L. K. B., Markham, C. M., Ruiter, R. A. C., Fernández, M. E., Kok, G., and Parcel, G. S. (2016). Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Fledderus, M., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Pieterse, M. E., and Schreurs, K. M. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 42, 485–495. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001206

Fogg, B. J. (2019). Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Fontana, A. F., Marcus, J. L., Dowds, B. N., and Hughes, L. A. (1980). Psychological impairment and psychological health in the psychological well-being of the physically ill. Psychosom. Med. 42, 279–288. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198003000-00005

Fritz, J., de Graaff, A. M., Caisley, H., Van Harmelen, A.-L., and Wilkinson, P. O. (2018). A systematic review of amenable resilience factors that moderate and/or mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health in young people. Front. Psychiatry 9:230. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00230

Gable, S. L., and Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 9, 103–110. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

Gallagher, E. N., and Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2008). Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Pers. Individ. Dif. 44, 1551–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.011

Garba, R. M., and Gadanya, M. A. (2017). The role of intervention mapping in designing disease prevention interventions: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One 12:e0174438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174438

Gielen, A. C., McDonald, E. M., Gary, T. L., and Bone, L. R. (2008). Using the precede-proceed model to apply health behavior theories. Health Behav. Health Educ. 4, 407–429.

Gilbert, K. E. (2012). The neglected role of positive emotion in adolescent psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.005

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., et al. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 59, 52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

Gollwitzer, P. M., and Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 69–119. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Gradisar, M., Gardner, G., and Dohnt, H. (2011). Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 12, 110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.008

Grant, F., Guille, C., and Sen, S. (2013). Well-being and the risk of depression under stress. PLoS One 8:e67395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067395

Green, L., and Kreuter, M. (1999). The Precede–Proceed Model. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational Approach, 3rd Edn. (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company), 32–43.

Green, S., Robinson, P. L., and Oades, L. G. (2011). “The role of positive psychology in creating the psychologically literate citizen,” in The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives, eds J. Cranney and D. S. Dunn (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199794942.003.0036

Greenspoon, P. J., and Saklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Soc. Indic. Res. 54, 81–108. doi: 10.1023/A:1007219227883

Harms, P. D., Brady, L., Wood, D., and Silard, A. (2018). Resilience and Well-Being. Handbook of Well-Being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

Hayes, S. C., and Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Process-Based CBT: The Science and Core Clinical Competencies of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Heintzelman, S. J., and Kushlev, K. (2020). Emphasizing scientific rigor in the development, testing, and implementation of positive psychological interventions. J. Posit. Psychol. 15, 685–690. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1789701

Hodges, L. J., Walker, J., Kleiboer, A. M., Ramirez, A. J., Richardson, A., Velikova, G., et al. (2011). What is a psychological intervention? A metareview and practical proposal. Psychooncology 20, 470–478. doi: 10.1002/pon.1780

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., et al. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

Hoffmann, T. C., Oxman, A. D., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Moher, D., Lasserson, T. J., Tovey, D. I., et al. (2017). Enhancing the usability of systematic reviews by improving the consideration and description of interventions. BMJ 358:j2998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2998

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T., and Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 36, 427–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

Hofmann, S. G., and Hayes, S. C. (2019). The future of intervention science: process-based therapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 7, 37–50. doi: 10.1177/2167702618772296

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., and Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 78, 169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555

Howell, A. J., Dopko, R. L., Passmore, H.-A., and Buro, K. (2011). Nature connectedness: associations with well-being and mindfulness. Pers. Individ. Dif. 51, 166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037

Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., Keyes, C. L. M., and Cochrane, E. M. (2019). Positive mental health as a predictor of recovery from mental illness. J. Affect. Disord. 251, 227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.065

Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2020). Mental health and/or mental illness: a scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evid. Base 2020, 1–45. doi: 10.21307/eb-2020-001

Ivtzan, I., and Papantoniou, A. (2014). Yoga meets positive psychology: examining the integration of hedonic (gratitude) and eudaimonic (meaning) wellbeing in relation to the extent of yoga practice. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 18, 183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.11.005

Jacka, F. N., Cherbuin, N., Anstey, K. J., and Butterworth, P. (2015). Does reverse causality explain the relationship between diet and depression? J. Affect. Disord. 175, 248–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.007

Jahoda, M. (1958). Current Concepts of Positive Mental Health. New York, NY: Basic books. doi: 10.1037/11258-000

Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 67, 231–243. doi: 10.1037/a0025957

Kashdan, T. B., and Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

Kawachi, I., and Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 78, 458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., and Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

Keyes, C. L. M. (2003). “Complete mental health: an agenda for the 21st Century,” in Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived, eds C. L. M. Keyes and J. Haidt (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 293–312. doi: 10.1037/10594-013

Keyes, C. L. M. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am. Psychol. 62, 95–108. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

Keyes, C. L. M., Dhingra, S. S., and Simoes, E. J. (2010). Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. Am. J. Public Health 100, 2366–2371. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245

Kinderman, P., Tai, S., Pontin, E., Schwannauer, M., Jarman, I., and Lisboa, P. (2015). Causal and mediating factors for anxiety, depression and well-being. Br. J. Psychiatry 206, 456–460. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147553

Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., Peters, G.-J. Y., Mullen, P. D., Parcel, G. S., Ruiter, R. A. C., et al. (2016). A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an Intervention Mapping approach. Health Psychol. Rev. 10, 297–312. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155

Korpela, K. M., Stengard, E., and Jussila, P. (2016). Nature walks as a part of therapeutic intervention for depression. Ecopsychology 8, 8–15. doi: 10.1089/eco.2015.0070

Kristjánsson, K. (2012). Positive psychology and positive education: Old wine in new bottles? Educ. Psychol. 47, 86–105. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2011.610678

Kyrios, M. (2016). “The self in psychological disorders: and introduction,” in The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders, eds M. Kyrios, R. Moulding, G. Doron, S. Bhar, M. Nedeljkovic, and M. Mikulincer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 25–37.

Lamers, S. M., Westerhof, G. J., Glas, C. A., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2015). The bidirectional relation between positive mental health and psychopathology in a longitudinal representative panel study. J. Posit. Psychol. 10, 553–560. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015156

Lamers, S. M. A., Bolier, L., Westerhof, G. J., Smit, F., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2012). The impact of emotional well-being on long-term recovery and survival in physical illness: a meta-analysis. J. Behav. Med. 35, 538–547. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9379-8

Larsen, K. R., Michie, S., Hekler, E. B., Gibson, B., Spruijt-Metz, D., Ahern, D., et al. (2017). Behavior change interventions: the potential of ontologies for advancing science and practice. J. Behav. Med. 40, 6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9768-0

Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., and Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 199, 445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M., and West, R. (2011b). The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Michie, S., Ashford, S., Sniehotta, F. F., Dombrowski, S. U., Bishop, A., and French, D. P. (2011a). A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol. Health 26, 1479–1498. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.540664

Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., et al. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 350:h1258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258

Nanri, A., Kimura, Y., Matsushita, Y., Ohta, M., Sato, M., Mishima, N., et al. (2010). Dietary patterns and depressive symptoms among Japanese men and women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 832–839. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.86

Naslund, J., Aschbrenner, K., Marsch, L., and Bartels, S. (2016). The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 25, 113–122. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015001067

Naslund, J. A. (2017). Digital Technology for Health Promotion Among Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. Ph.D. thesis. Ann Arbor, MI: Dartmouth College.

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., and Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J. Res. Pers. 41, 139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Norcross, J. C., and Wampold, B. E. (2011). What works for whom: tailoring psychotherapy to the person. J. Clin. Psychol. 67, 127–132. doi: /10.1002/jclp.20764

Oades, L. G. (2017). “Wellbeing literacy: the missing link in positive education,” in Future Directions in Well-Being, eds M. A. White, G. R. Slemp, and A. S. Murray (Cham: Springer), 169–173. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56889-8_29

O’Cathain, A., Croot, L., Duncan, E., Rousseau, N., Sworn, K., Turner, K. M., et al. (2019). Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 9:e029954. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954

Oddy, W. H., Robinson, M., Ambrosini, G. L., Therese, A. O., de Klerk, N. H., Beilin, L. J., et al. (2009). The association between dietary patterns and mental health in early adolescence. Prev. Med. 49, 39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.05.009

Öst, L.-G. (2014). The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 61, 105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.018

Öst, L.-G., and Ollendick, T. H. (2017). Brief, intensive and concentrated cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 97, 134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.008

Passmore, H.-A., and Holder, M. D. (2017). Noticing nature: individual and social benefits of a two-week intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 537–546. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1221126

Pearce, J., Mann, M. K., Jones, C., Van Buschbach, S., Olff, M., and Bisson, J. I. (2012). The most effective way of delivering a train-the-trainers program: a systematic review. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 32, 215–226. doi: 10.1002/chp.21148

Penedo, F. J., and Dahn, J. R. (2005). Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 18, 189–193. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013

Peter, T., Roberts, L. W., and Dengate, J. (2011). Flourishing in life: an empirical test of the dual continua model of mental health and mental illness among Canadian university students. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 13, 13–22. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2011.9715646

Peters, G.-J. Y., De Bruin, M., and Crutzen, R. (2015). Everything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler: towards a protocol for accumulating evidence regarding the active content of health behaviour change interventions. Health Psychol. Rev. 9, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.848409

Pino, C., Boutron, I., and Ravaud, P. (2012). Inadequate description of educational interventions in ongoing randomized controlled trials. Trials 13:63. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-63

Prager, E. M., Chambers, K. E., Plotkin, J. L., McArthur, D. L., Bandrowski, A. E., Bansal, N., et al. (2019). Improving transparency and scientific rigor in academic publishing. J. Neurosci. Res. 97, 377–390. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24340

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., and Ruch, W. (2014). Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50–79 years: long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging Ment. Health 18, 997–1005. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.899978

Proyer, R. T., Wellenzohn, S., Gander, F., and Ruch, W. (2015). Toward a better understanding of what makes positive psychology interventions work: predicting happiness and depression from the person× intervention fit in a follow-up after 3.5 years. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 7, 108–128. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12039

Raymond, I. I., Kelly, D., and Jarden, A. (2019). Program logic modelling and complex positive psychology intervention design and implementation: the ‘Resilient Futures’ case example. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 3, 43–67. doi: 10.1007/s41042-019-00014-7

Raymond, I. J., Iasiello, M., Jarden, A., and Kelly, D. M. (2018). Resilient futures: an individual and system-level approach to improve the well-being and resilience of disadvantaged young Australians. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 4, 228–244. doi: 10.1037/tps0000169

Rethorst, C. D., Wipfli, B. M., and Landers, D. M. (2009). The antidepressive effects of exercise. Sports Med. 39, 491–511. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939060-00\break004

Rienks, J., Dobson, A. J., and Mishra, G. D. (2013). Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-aged women: results from a large community-based prospective study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 67, 75–82. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.193

Rios, L. M., Serrano, M. M., Aguilar, A. J., Chacón, L. B., Neria, C. M. R., and Monreal, L. A. (2019). Promoting fruit, vegetable and simple water consumption among mothers and teachers of preschool children: an intervention mapping initiative. Eval. Program Plann. 76:101675. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101675

Robertson, I. T., Cooper, C. L., Sarkar, M., and Curran, T. (2015). Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: a systematic review. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 88, 533–562. doi: 10.1111/joop.12120

Roy, A., Sarchiapone, M., and Carli, V. (2007). Low resilience in suicide attempters. Arch. Suicide Res. 11, 265–269. doi: 10.1080/13811110701403916

Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., and Haro, J. M. (2015). The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 175, 53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049

Scheerman, J. F. M., Van Empelen, P., Van Loveren, C., and Van Meijel, B. (2018). A mobile app (WhiteTeeth) to promote good oral health behavior among Dutch adolescents with fixed orthodontic appliances: intervention mapping approach. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6:e163. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9626

Schiele, M. A., Gottschalk, M. G., and Domschke, K. (2020). The applied implications of epigenetics in anxiety, affective and stress-related disorders-A review and synthesis on psychosocial stress, psychotherapy and prevention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 77:101830. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101830

Schneider, S. L. (2001). In search of realistic optimism: meaning, knowledge, and warm fuzziness. Am. Psychol. 56, 250–263. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.250

Schork, N. J. (2015). Personalized medicine: time for one-person trials. Nat. News 520, 609–611. doi: 10.1038/520609a

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Keyes, C. L., de Graaf, R., and ten Have, M. (2019). Recovery from mood and anxiety disorders: the influence of positive mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 252, 107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.051

Schroder, H. S., Yalch, M. M., Dawood, S., Callahan, C. P., Donnellan, M. B., and Moser, J. S. (2017). Growth mindset of anxiety buffers the link between stressful life events and psychological distress and coping strategies. Pers. Individ. Dif. 110, 23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.016