- Shaanxi Provincial Key Research Center of Child Mental and Behavioral Health, School of Psychology, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi' an, China

Social anxiety has been a common problem among college students and has an adverse impact on their adaptation outcomes. Among influential factors, parental marital conflict and attachment (parental and peer attachment) have been found to be related to social anxiety symptoms of college students; however, little is known how parental marital conflict and attachment jointly contribute to social anxiety symptoms of college students. The current study explored this issue. Self-reported questionnaires of perception of children of interparental conflict scale, inventory of parent and peer attachment, and the social interaction anxiety scale were administered to 707 undergraduate students (Mean age = 19.27, SD = 0.97). Results indicated that perceived parental marital conflict was positively correlated with social anxiety symptoms and was negatively associated with parental and peer attachment. Parental and peer attachments were negatively correlated with social anxiety symptoms. Mediation analyses indicated that perceived parental marital conflict exerted its indirect effect on social anxiety symptoms through a serial multiple mediation role of parental and peer attachment. The present findings highlight the serial multiple mediation role of parental and peer attachment in the relationship between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms of college students.

Introduction

Recently, the psychological well-being of college students has been a wide concern for society. Among the multiple physical and mental problems, social anxiety has become one of the major psychological problems of college students (Zhao and Dai, 2016; Shi et al., 2019). Social anxiety refers to the negative emotional experience like tension, uneasiness, and fear of social situations caused by the excessive worry of being evaluated or scrutinized by others in public (Morrison and Heimberg, 2013; Boehme et al., 2014), which has an adverse impact on academic, social, and emotional functioning of college students (Book and Randall, 2002; Auerbach et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Previous studies showed that the level of social anxiety increased significantly from adolescence to early adulthood, especially in college years, during which various challenges (i.e., interpersonal communication problems) need to be faced which might more likely lead to higher levels of social anxiety symptoms than other age groups (Herman, 1998). Multiple factors contribute to the development of social anxiety symptoms of college students (El-Sheikh et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), among which family risk environmental factors such as parental marital conflict (Riggio, 2004; Fosco and Feinberg, 2015) has been regarded as an important contributor, and perceptions about such conflicts may be a key factor linking marital dissatisfaction with deleterious adaptations like social anxiety symptoms (Cummings and Schatz, 2012). In addition, attachment (parental and peer attachment) has been found to be associated with social anxiety symptoms of college students (Lu et al., 2015; Gorrese, 2016; Manes et al., 2016). However, previous studies focused on the relation between perceived parental marital conflict, parental and peer attachment, and social anxiety symptoms mostly on Western children and adolescents, while research investigating Chinese college students is still lacking. Therefore, the current study aimed to explore whether parental and peer attachment played a serial multiple mediation role in the relationship between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms in Chinese college students.

Parental Marital Conflict and Social Anxiety

Parental marital conflict refers to any disagreement, difference, or argument regarding an issue of family life, which includes all kinds of physical and psychological conflicts, and has been commonly considered as a core predictor of family solidarity and the key factor in determining family life quality (Erel and Burman, 1995; Cummings and Davies, 2002). Emotional security theory (EST, Davies and Cummings, 1994), as an important theoretical model to investigate the impact of parental marital conflict on the adaptation of children, has been supported by numerous empirical studies (e.g., Kouros et al., 2010; Cummings et al., 2013). A core perspective of EST is that the internalized representations of family relations and response processes of children that develop with time have profound effects on their long-term adaptation (Davies and Cummings, 1994), and perceptions that children have about parental marital conflict may be a key factor linking marital dissatisfaction with maladaptations of the children. According to the EST, perceptions about parental marital conflict destroy the emotional security of children about family relations, increases their negative behavioral and emotional responses, thus increasing their psychological maladaptation (Davies and Cummings, 1994). Based on EST, a large number of studies have shown that perceived parental marital conflict is associated with adjustment problems of children and adolescents like externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and academic difficulties (Davies and Lindsay, 2004; Cummings and Davies, 2010; Cummings et al., 2012; for reviews, see Grych and Fincham, 2001; Li Y. et al., 2016; Khurshid et al., 2019; Li D. et al., 2020). Specifically, empirical studies provided evidence that perceived parental marital conflict could impact social anxiety symptoms (Riggio, 2004; Gao et al., 2018) of individuals. For example, Riggio (2004) found that perceived parental marital conflict had a significant effect on the anxiety of young adults in personal relationships.

Attachment and Social Anxiety

Attachment refers to a close, long-lasting emotional bond between an infant and a caregiver (Bowlby, 1969/1982), or a long-lasting emotional bond of substantial intensity (Armsden and Greenberg, 1987). Research of attachment is based on two theoretical viewpoints, that is, internal working models (IWMs) and attachment relationship approach (Buist et al., 2002, 2004; Li J. B. et al., 2020). The two viewpoints are different but not contradicting in understanding attachment to adolescents and their developmental adaptations. The most significant difference between these two perspectives is how attachment is conceptualized. The IWM is noted as the social cognitive perspective and is largely focused on the assessment of mental representations of people of both the self and others in close relationships, which reflects the relative stability and continuity of attachment (Bartholomew, 1990). According to the attachment relationship approach, attachment is supposed to emphasize specific relationships and is seen as changeable throughout time. As adolescents grow up, the security fostered by their parents becomes more dependent on the abilities of their parents to function as competent allies and less on their actual presence (i.e., availability; Weiss, 1982; Armsden and Greenberg, 1987), which means that the maturity of adolescents and its related adaptations might be associated with greater attachment represented as a parent-child relationship instead of the one represented as the actual availability of parents. Therefore, researchers suggested that investigating specific attachment relationships could help better explain the function and development of attachment in early and later adolescence than IWMs (Buist et al., 2002; Li D. et al., 2020). Furthermore, a self-report measure, inventory of parent and peer attachment (IPPA) (Armsden and Greenberg, 1987; Li D. et al., 2020), is commonly used to assess specific attachment relationships including parental and peer attachment in youth (Armsden and Greenberg, 1987). Accordingly, the measure of IPPA was used in the current study focusing on the specific attachment of later adolescent (i.e., college students) relationships with their parents and peers.

Parental attachment is a tight emotional bond established between the infant and parents (Bowlby, 1969/1982). The quality of parental attachment relationships is significantly related to the social adaptation and development of individuals (Li C. et al., 2016). Regarding social anxiety symptoms, previous research suggested that parental attachment and social anxiety symptoms are intensely intertwined and that insecure and dysfunctional parental attachment relationships may predispose adolescents to social anxiety symptoms (Leung et al., 1994; Eng et al., 2001; Harvey et al., 2005). Therefore, a low-quality parental attachment relationship is another important factor that influences the development and maintenance of social anxiety symptoms (Mothander and Wang, 2014; Zhao et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017).

In addition, recent studies have emphasized the impact of peer attachment relationships on social anxiety symptoms. Peer attachment is defined as a significant and enduring emotional and social bond with close friends, which is characterized by good communication, mutual understanding, trust, and emotional closeness (Laible et al., 2000; Theisen et al., 2018). Adolescents who are insecurely attached to their peers perceive their close friends as neither supportive nor trustworthy and often feel rejected by their close friends, and thus tend to develop social anxiety symptoms (Gorrese, 2016). A low-quality peer attachment relationship is also one of the robust predictors of social anxiety symptoms among college students (Burge et al., 1997). During college years, low-quality peer attachment relationships such as lack of intimacy, companionship, emotional support, and closeness are associated with increased social anxiety symptoms (Greca and Lopez, 1998; Hawker and Boulton, 2000).

Parental Marital Conflict, Attachment, and Social Anxiety Symptoms

Attachment theory highlights the significance of security in the attachment relationship as an internal goal for human beings and lays the groundwork for the future interpersonal relationship quality, whereas EST postulates that maintaining safety and security in the interpersonal relationships are among the most salient in the hierarchy of human goals (Bowlby, 1973; Davies and Woitach, 2008). The EST literature showed that parental marital conflict may spill over to parenting behaviors and attachment relationships to influence the emotional insecurity and adjustment of the individual (e.g., Schermerhorn et al., 2008). Based on EST (Davies and Cummings, 1994; Davies et al., 2002) and the attachment relationship approach (Buist et al., 2002, 2004; Li J. B. et al., 2020), individuals might feel insecure and seem to fear parents and/or be away from them when they perceive parental marital conflict, which in turn can influence their attachment quality. Previous evidences have verified the link between perceived parental marital conflict and attachment (Stocker and Youngblade, 1999; El-Sheikh and Elmore-Staton, 2004; Yang et al., 2016). For example, Yang et al. (2016) found that a higher level of perceived parental marital conflict was negatively linked to the attachment of college students including parental attachment and peer attachment. Thus, it can be assumed that perceived parental marital conflict was negatively associated with the attachment quality of college students toward parents and peers.

In addition, parental and peer attachment are closely related. Attachment theory proposes that attachment relationships initially begin with parents and their infants and serve as affective support and a safe base. As individuals grow up, attachment relationships expand toward peers, and such relationships become the central arena in which attachment processes are possible to play out during adolescence and beyond and contribute to multiple aspects of psychosocial adaptations (Ainsworth, 1989). The positive relationship of parental and peer attachment has been verified, and the mediation role of peer attachment linking parental attachment to adaptation performance of individuals (i.e., addictive behaviors; positive social adjustment, and anxiety) has also been confirmed previously (Gorrese, 2016; Yang et al., 2016; Davies et al., 2018). Furthermore, as noted before, poor attachment relationship quality has been regarded as a risk factor contributing to maladjustments of individuals, such as internet addiction (Deng et al., 2013a,b; Yang et al., 2016) and social anxiety symptoms (Wu and Wang, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Gorrese, 2016; Manes et al., 2016; Pan et al., 2016; Manning et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2019). Based on the theories and previous findings, it could be assumed that parental and peer attachment relationships were significantly related to social anxiety symptoms of college students.

As outlined above, both parental and peer attachment have been regarded as important mediators linking parental marital conflict to adaptations of college students. However, the previous researches were mainly conducted among Western children and adolescents, with only a few studies examining the effects of parental and peer attachment between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms based on Chinese college students.

The Present Study

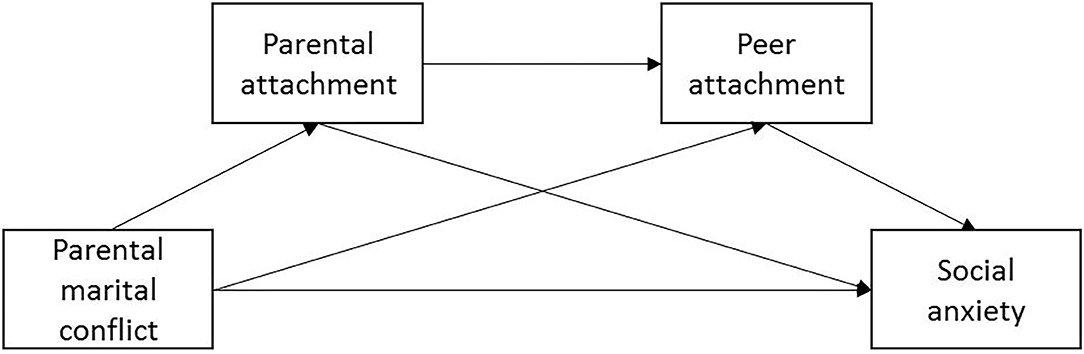

In summary, guided by EST (Davies and Cummings, 1994) and attachment theory (Buist et al., 2002, 2004; Li D. et al., 2020), the current study aimed to examine the serial multiple mediation role of parental and peer attachment in the relationship between perceived parental marital conflict and the social anxiety symptoms of Chinese college students. Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that (1) perceived parental marital conflict would be positively associated with social anxiety symptoms and negatively associated with attachment quality (including parental and peer attachment). Both parental and peer attachment would be negatively associated with social anxiety symptoms, and (2) the association between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms would be mediated by parental and peer attachment (see the hypothesized mediation model, Figure 1).

Methods

Participants

Only Chinese college students were eligible to participate in the present study. We recruited participants from Xi'an, China, using convenience sampling techniques, and a total of 707 college students (133 males, mean age = 19.27 years, SD = 0.97, age range: 16–25) participated in the present study. Among them, 50.4% of the students were from urban areas, 28% from the town, and 21.6% from rural areas. The sample consisted of four grades: 18.8% were freshmen, 44.6% were sophomores, 28.7% were juniors, and 7.9% were seniors. In addition, 33.9% of the students came from the fields of liberal arts, and 66.1% came from the fields of science.

About 83.7% of the participants reported that their average monthly household income was <10,000 RMB. For parental education levels, 64.1% of the participants reported that their father had a high school degree or less and 34.4% of the fathers had a bachelor's degree or above. Almost 71.1% of the participants reported that their mother had a high school degree or less and 28.1% of the mothers had a bachelor's degree or above.

Procedure

The present study was approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Shaanxi Normal University, China. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. The study consisted of two parts. First, a total of 230 questionnaires were distributed by two researchers in classrooms, and 225 valid questionnaires were returned. To minimize the impact of social desirability, each individual was informed by the researcher to answer every question on the questionnaires as honestly as possible. Second, to ensure an optimal sample size, researchers collected another 482 questionnaires online. Based on the requirement that no item on the online survey should have missing data, all responses of the 482 college students were included in the present study. Thus, there were a total of 707 valid questionnaires in this study.

Measures

Parental Marital Conflict

Perceived parental marital conflict was measured using the Chinese version of children's perception of interparental conflict scale (CPIC; Grych et al., 1992) revised by Chi and Xin (2003). This scale has shown good reliability and validity among Chinese college students (Qing et al., 2017). This study only adopted the subscale of conflict property which had 19 items, including conflict frequency (six items), conflict intensity (seven items), and conflict resolution (six items) [χ2/df = 5.13, tucker-lewis index (TLI) = 0.91, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.92, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.074]. All items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = not at all compliant to 4 = completely compliant). The higher scores indicated higher levels of perceived parental marital conflict. For the current study, Cronbach's alpha for the scale was 0.94.

Attachment

An attachment was assessed using the inventory of parent and peer attachment (IPPA; Armsden and Greenberg, 1989), which consisted of three forms for the mother, father, and peer-yielding three attachment scores, each with 25 items. The scale had three subscales: trust, communication, and alienation. Participants were required to rate the items from 1 (almost never or never true) to 5 (almost always or always true). After the alienation items and the negatively worded items were reversely scored, the parental attachment (χ2/df = 5.13, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.077) score was the sum of the 50 items from the mother form and father form, and the peer attachment (χ2/df = 4.42, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.069) score was the sum of the 25 items from the peer form. Previous studies have proved that IPPA had well-established content validity and was suitable for college students (Guarnieri et al., 2015; Lepp et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016). In the current study, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.86 and 0.85 for parent and peer attachment, respectively, and 0.89 for the total scale.

Social Anxiety Symptoms

The social interaction anxiety scale (SIAS; Mattick and Clarke, 1998) was administered to assess affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions in 20 social interaction situations associated with interacting or engaging with others. It consisted of 20 items (χ2/df = 4.33, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.069) such as “when mixing socially, I am uncomfortable” and “I have difficulty talking with other people,” each rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all characteristic of me) to 4 (extremely characteristic of me). This measure had shown good reliability and validity in samples of Chinese college students (Ye et al., 2007). Higher total scores indicated higher levels of social anxiety symptoms. Cronbach's α for the measure in this study was 0.90.

Data Analysis

One researcher collated the data for analysis. The SPSS version 22.0 and AMOS 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) were used to conduct the following analyses. First, Pearson's correlation analysis was conducted to examine zero-order associations between all the study variables. Then, structural equation models (SEM) were developed based on hypothesized relationships between variables and tests of preliminary models. SEM is a very general, powerful multivariate technique that is used to explain the relationship between multiple variables and concepts, which can combine mediation analysis with latent variable analysis and provides model fit information about the consistency of the hypothesized mediation model to the data. Model fit was assessed by RMSEA, TLI, and CFI. The adequate fit was suggested for values less than or equal to 0.08 for the RMSEA and greater than or equal to 0.90 for the TLI and CFI (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Wen et al., 2004). Finally, the bootstrap method was used to test the indirect effects. We calculated bias-corrected and accelerated 95% bootstrap CIs based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples. If a 95% CI did not contain zero, then the indirect effect was significant. Specific indirect effects were estimated using an AMOS user-defined estimand.

Results

Common Method Bias

In the current study, all the data were collected using self-report measurements, which might lead to common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, a single factor test of Harman was conducted to rule out the common method bias (Harman, 1976). According to Harman (1976), common method bias existed when only one factor emerged or when one factor explained for more than 40% of the variance associated with all items loaded simultaneously in factor analysis. The results of the factor analysis of the current study showed that a single factor explained 21.20% of the total variance, which indicated no significant common method bias.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

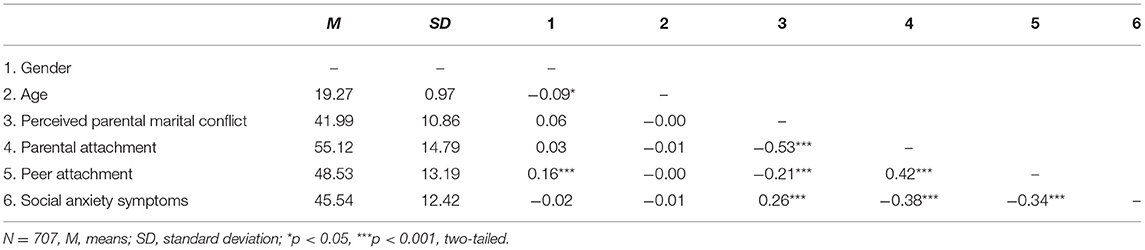

Means, SDs, and bivariate correlations of all the study variables are displayed in Table 1. As hypothesized, perceived parental marital conflict was positively related to social anxiety symptoms, and negatively related to parental and peer attachment. Parental and peer attachments were negatively correlated with social anxiety symptoms. In addition, a positive relationship was found between parental attachment and peer attachment.

Serial Multiple Mediation Analyses

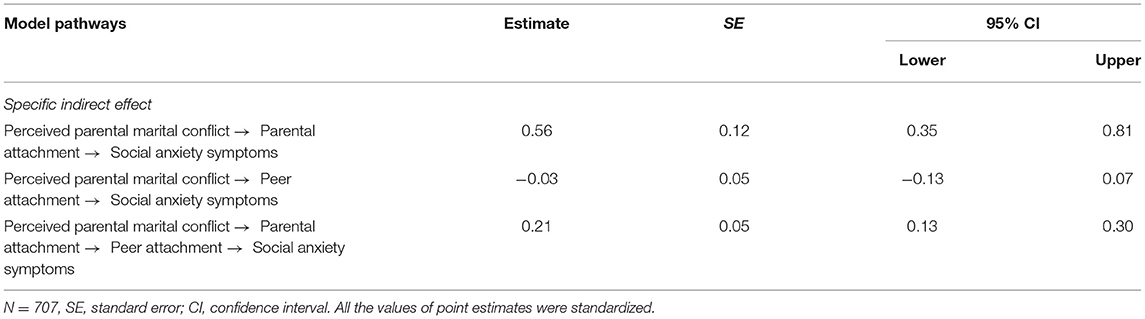

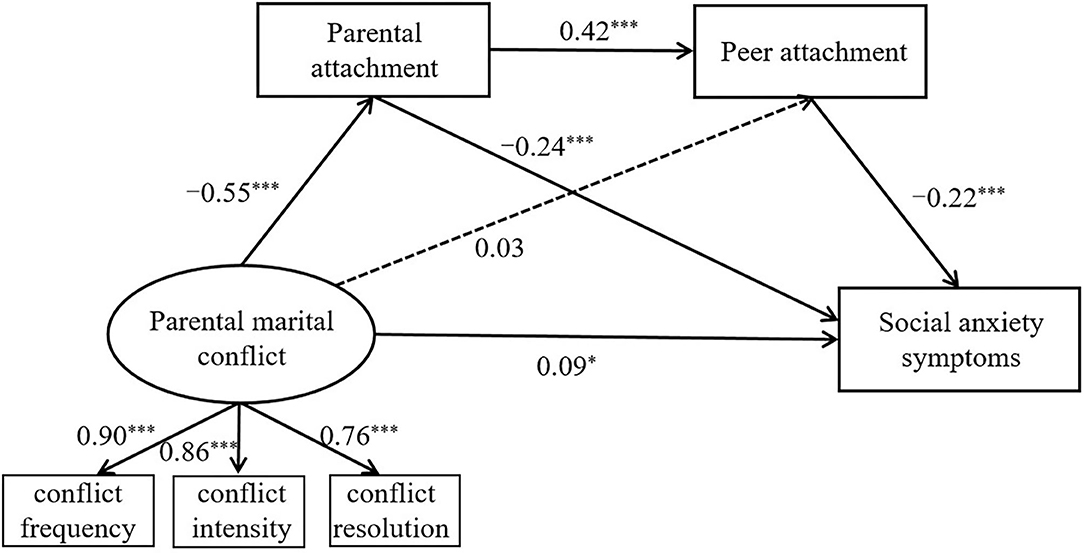

The direct and indirect effects of perceived parental marital conflict on social anxiety symptoms of college students were then examined using AMOS 23.0. We hypothesized that perceived parental marital conflict had a direct effect on social anxiety symptoms of college students, whereas perceived parental marital conflict influenced social anxiety symptoms of college students through serial multiple mediating effects of parental attachment and peer attachment. The fit indices indicated that the model (Model 1) was fitting well (χ2/df = 4.90, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.074). However, in this model, the path from perceived parental marital conflict to peer attachment was not significant; we thus reexamined the model after the non-significant path had been deleted, and the goodness-of-fit for the final model (Model 2) showed that the model fitted the data well (χ2/df = 4.27, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.068). Thus, Model 2 (path coefficients see Figure 2) demonstrated a better fit than Model 1 and could be used for further analysis. Finally, the bootstrap test showed that the serial multiple mediation effects of parental and peer attachment were significant in Model 2 (see Table 2). Thus, the perceived parental marital conflict of college students might exert an indirect effect on their social anxiety symptoms through parental attachment and peer attachment. Parental attachment and peer attachment could serially mediate the effect of perceived parental marital conflict on social anxiety symptoms of college students.

Figure 2. Standardized path coefficients for effects of parental marital conflict on social anxiety symptoms.

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the mechanisms underlying the relation between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms of college students. Drawn from the perspectives of EST and attachment theory, we examined a serial multiple mediation model with parental and peer attachment in the association between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms among Chinese college students.

The present study found that perceived parent marital conflict was positively associated with social anxiety symptoms of college students. The family environment has been regarded as a particularly significant context for the social and psychological adjustment of individuals (Ko et al., 2015). According to EST (Davies and Cummings, 1994), a higher level of previous exposure to parental marital conflict left children primed for higher and even more negative, emotional responses in later conflict contexts. The present findings are in line with EST and empirical studies, thus suggesting that adolescents or college students who grow in families with chronic parental marital conflict are at a higher risk of acquiring and maintaining social anxiety symptoms (Riggio, 2004; Cusimano and Riggs, 2013; Gao et al., 2018). In addition, individuals who grow in families with frequent, hostile, and poorly resolved parental marital conflict have also been found to have internalizing and externalizing problems, such as substance use (Fosco and Feinberg, 2018), depression (Bernet et al., 2016; Tu et al., 2016), and decreased self-efficacy (Fosco and Feinberg, 2015). Altogether, it can be concluded that parental marital conflict, as an adverse family environmental factor, contributes to the maladjustment of individuals including social anxiety symptoms.

Consistent with the attachment relationship perspective (Buist et al., 2002, 2004; Li D. et al., 2020) and previous studies, the present study found that parental, peer attachment was negatively associated with social anxiety symptoms of college students. As mentioned previously, low-quality parental and peer attachment relationships could increase the risk of social anxiety problems (Mothander and Wang, 2014; Wu and Wang, 2014). Prior evidence has indicated that high-quality parental or peer attachment relationships could effectively cultivate and enhance interpersonal relationships of individuals and reduce the generation of social anxiety symptoms (Wang et al., 2017). On the contrary, individuals growing up in an environment of low-quality parental and peer attachment relationships might unconsciously learn from poor social models and are more likely to adopt maladaptive interpersonal strategies when interacting with others, resulting in interpersonal tensions and social anxiety symptoms (Wang et al., 2017). Accordingly, the present study finding suggests that college students with higher levels of parental or peer attachment relationships might have better interpersonal relationships and have lower levels of social anxiety symptoms. On the contrary, college students who have low-quality attachment relationships with their parents or peers might have maladaptive interpersonal skills in interacting with others and have higher levels of social anxiety symptoms.

Importantly, extending the extant evidence, the present study further showed that there were significant serial mediating effects of parental attachment and peer attachment in the relationships between perceived parent marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms of college students. Specifically, higher levels of perceived parental marital conflict are negatively associated with parental attachment and then peer attachment, which is related to increased social anxiety symptoms of college students. According to Davies and Cummings (1994), parental marital conflict may negatively influence attachment by increasing the negativity of parent-child relationships or by decreasing emotional availability and parental involvement, whereas secure attachment relationships might buffer the impact of parental marital conflict on adaptations of an individual. Based on EST and attachment theory, emotional distress from perceived parental marital conflict spilled over to the attachment relationships between parents and their children, which resulted in the incompetence of children in maintaining close relationships, such as peer attachment in emerging adulthood. College students who have perceived more parental marital conflict might be more vulnerable to develop low-quality attachment relationships with their parents, which in turn might be more likely to form low-quality attachment relationships with peers, thus developing social anxiety symptoms. In contrast, college students who have perceived less parental marital conflict would gain from the security of attachment with their parents, which would cultivate positive relationships in forming high-quality peer attachment, and would decrease the vulnerability in developing social anxiety symptoms. Previous studies have revealed that a higher level of perceived parental marital conflict was positively related to low-quality parental attachment relationships, which in turn might be linked to problematic peer attachment relationships of individuals (Yang et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2018), and that individuals who had formed poor attachment relationships with their parents and peers tended to report a higher level of social anxiety symptoms (Gorrese, 2016). Our study provides direct evidence showing that perceived parent marital conflict exerted its indirect effect on social anxiety symptoms through a serial multiple mediation role of parental attachment to peer attachment.

The present study has important implications. For theoretical contributions, based on the EST and attachment relationship approach, we provide important empirical evidence to explain the underlying mechanisms of how the psychosocial environment of a family (i.e., parent marital conflict) could impact social anxiety symptoms of Chinese college students, which extends the applicability of these two constructs in Chinese society. For practical implications, first, our findings indicate that parents should consciously avoid or reduce conflicts, especially in front of their children. Furthermore, they should spend more time bonding with their children, with warmth and encouragement, as high-quality attachment relationships might form a harmonious atmosphere within the family. This helps to improve marital quality and to reduce the emotional discomfort of the youths (Cox and Paley, 2003; Lindsey et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2016). Second, since peers are significant figures and contribute to multiple aspects of social adjustments of college students (Nelis and Rae, 2009; Balluerka et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016), it should be recommended for families and schools to establish relevant interventions to promote and cultivate positive peer attachment relationships, which might relieve social anxiety symptoms of college students and further promote the harmonious development of communities as well as interpersonal relationships (Nelis and Rae, 2009; Balluerka et al., 2016). Third, for clinical institutions, the present findings provide guidance that healthcare professionals can be involved in mental health promotions and interventions (consider the impacts of family and peer factors in the intervention design) in college students, and brief interventions to improve self-efficacy and motivate college students to engage in healthy activities could be useful in decreasing their social anxiety symptoms (Turner and Dadds, 2001; Harold and Sellers, 2018; Sang and Tan, 2018; Yang et al., 2020). Collectively, for improving mental health level of individuals, marital quality, interpersonal relationships, clinical practice, and further promoting the harmonious development of society, our findings hold significant implications.

There are several limitations of the present study which should be considered in future studies. First, although our findings identified a positive relationship between perceived parental marital conflict and social anxiety symptoms, the crosssectional nature of our study prevented us from examining the causality of the relationship between variables. Thus, future longitudinal and experimental researches should be carried out to examine the causal direction among perceived parental marital conflict, parental, peer attachment, and social anxiety symptoms of college students. Second, data for the current study was only collected from college students. To decrease the possibility of method bias, future studies should consider multiple measures and broader samples including parents, peers, and teachers. Third, other family-related risk factors that may negatively affect social adjustment, psychological well-being, and academic achievement of adolescents should be explored in future studies. Fourth, participants were recruited via convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the study findings; future research can use additional samples to investigate the validity and repeatability of our findings.

In conclusion, the current study investigated the core family environmental factor (i.e., parental marital conflict) and attachment relationships (i.e., parental, peer attachment) in relation to social anxiety symptoms of Chinese college students. Results showed that both perceived parental marital conflict and the quality of attachment relationships were important factors associated with social anxiety symptoms of college students. Furthermore, the present study highlighted the serial multiple mediation role of parental and peer attachment in the relationship between interparental conflict and social anxiety symptoms of college students. Overall, the present findings highlighted the importance of considering attachment relationships in understanding the mechanisms linking family risk factors (i.e., parental marital conflict) to social anxiety symptoms among Chinese college students.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Shaanxi Normal University, China. Informed consent was obtained by participants prior to data collection.

Author Contributions

ZW played the guiding role in designing research, providing suggestions for the first draft, and revision. AA and YH collected research data. AA and YZ contributed equally to this paper, for AA writing the first draft. YZ finishing the revision and improving the quality of this paper. All authors provided critical feedback and approved the final version submitted.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Grant of China (31671152) and Nutrition and Care of Maternal & Child Research Fund Project of Biostime Institute of Nutrition & Care (2018BINCMCF21) awarded to ZW, and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019TS138) awarded to YZ.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. Am. Psychol. 44, 709–716. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709

Armsden, G., and Greenberg, M. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual difference and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 16, 427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939

Armsden, G. C., and Greenberg, M. T. (1989). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Preliminary Test Manual. Seattle, WA: Department of Psychology; University of Washington.

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). WHO World Mental Health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127, 623–638. doi: 10.1037/abn0000362

Balluerka, N., Gorostiaga, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., and Aritzeta, A. (2016). Peer attachment and class emotional intelligence as predictors of adolescents' psychological well-being: a multilevel approach. J. Adolesc. 53, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.08.009

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: an attachment perspective. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 7, 147–178. doi: 10.1177/0265407590072001

Bernet, W., Wamboldt, M. Z., and Narrow, W. E. (2016). Child affected by parental relationship distress. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.018

Boehme, S., Miltner, W. H. R., and Straube, T. (2014). Neural correlates of self-focused attention in social anxiety. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 856–862. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu128

Book, S. W., and Randall, C. L. (2002). Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use. Alcohol Res. Health 26, 130–135.

Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1, Attachment, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Buist, K. L., Dekovic, M., Meeus, W., and Aken, M. A. (2002). Developmental patterns in adolescent attachment to mother, father, and sibling. J. Youth Adolesc. 31, 167–176. doi: 10.1023/A:1015074701280

Buist, K. L., Dekovic, M., Meeus, W., and Aken, M. A. G. V. (2004). The reciprocal relationship between early adolescent attachment and internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour. J. Adolesc. 27, 251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.012

Burge, D., Hammen, C., Davila, J., Daley, S. E., Paley, B., Lindberg, N., et al. (1997). The relationship between attachment cognitions and psychological adjustment in late adolescent women. Dev. Psychopathol. 9, 151–167. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001119

Chi, L., and Xin, Z. (2003). The revision of children's perception of marital conflict scale. Chin. Mental Health J. 17, 554–556.

Cox, M. J., and Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 12, 193–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259

Cummings, E., and Schatz, J. N. (2012). Family conflict, emotional security, and child development: translating research findings into a prevention program for community families. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 15, 14–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0112-0

Cummings, E. M., Cheung, R. Y. M., and Davies, P. T. (2013). Prospective relations between parental depression, negative expressiveness, emotional insecurity, and children's internalizin symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 44, 698–708. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0362-1

Cummings, E. M., and Davies, P. T. (2002). Effects of marital conflict on children: recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 43, 31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003

Cummings, E. M., and Davies, P. T. (2010). Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Cummings, E. M., George, M., Mccoy, K. P., and Davies, P. T. (2012). Interparental conflict in kindergarten and adolescent adjustment: prospective investigation of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Dev. 83, 1703–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01807.x

Cusimano, A. M., and Riggs, S. A. (2013). Perceptions of interparental conflict, romantic attachment, and psychological distress in college students. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Prac. 2, 45–59. doi: 10.1037/a0031657

Davies, P. T., and Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: an emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 116, 387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387

Davies, P. T., Forman, E. M., Rasi, J. A., and Stevens, K. I. (2002). Assessing children's emotional security in the interparental relationship: the security in the interparental subsystem scales. Child Dev. 73, 544–562. doi: 10.2307/3696374

Davies, P. T., and Lindsay, L. L. (2004). Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: why does gender moderate early adolescent vulnerability? J. Fam. Psychol. 18, 160–170. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.160

Davies, P. T., Martin, M. J., and Cummings, E. M. (2018). Interparental conflict and children's social problems: insecurity and friendship affiliation as cascading mediators. Dev. Psychol. 54, 83–97. doi: 10.1037/dev0000410

Davies, P. T., and Woitach, M. J. (2008). Children's emotional security in the interparental relationship. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 17, 269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00588.x

Deng, L. Y., Fang, X. Y., and Yan, J. (2013a). The Relationship between inter-parental relationship parent-child relationship and adolescents” Internet addiction. J. Spec. Educ. 9, 71–77.

Deng, L. Y., Fang, X. Y., Wu, M. M., Zhang, J. T., and Liu, Q. X. (2013b). Family environment, parent-child attachment and adolescent Internet addiction. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 29:305e311. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.03.008

El-Sheikh, M., and Elmore-Staton, L. (2004). The link between marital conflicts and child adjustment: parent–child conflicts and perceived attachments as mediators, potentiator and mitigators of risk. Dev. Psychopathol. 16, 631–648. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004705

El-Sheikh, M., Keiley, M., Erath, S., and Dyer, W. J. (2013). Marital conflict and growth in children's internalizing symptoms: the role of autonomic nervous system activity. Dev. Psychol. 49, 92–108. doi: 10.1037/a0027703

Eng, W., Heimberg, R. G., Hart, T. A., Schneier, F. R., and Liebowitz, M. R. (2001). Attachment in individuals with social anxiety disorder: the relationship among adult attachment styles, social anxiety, and depression. Emotion 1, 365–380. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.4.365

Erel, O., and Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 118, 108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108

Fosco, G. M., and Feinberg, M. E. (2015). Cascading effects of interparental conflict in adolescence: linking threat appraisals, self-efficacy, and adjustment. Dev. Psychopathol. 27, 239–252. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000704

Fosco, G. M., and Feinberg, M. E. (2018). Interparental conflict and longterm adolescent substance use trajectories: examining threat appraisals as a mechanism of risk. J. Fam. Psychol. 32, 175–185. doi: 10.1037/fam0000356

Gao, T. T., Meng, X. F., Qin, Z. Y., Zhang, H., Gao, J. L., Kong, Y. X., et al. (2018). Association between parental marital conflict and internet addiction: a moderated mediation analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 240, 27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.005

Gorrese, A. (2016). Peer attachment and youth internalizing problems: a meta-analysis. Child Youth Care Forum 45, 177–204. doi: 10.1007/s10566-015-9333-y

Greca, A. M. L., and Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 26, 83–94. doi: 10.1023/A:1022684520514

Grych, J. H., and Fincham, F. D. (2001). Interparental Conflict and Child Development: Theory, Research, and Applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Grych, J. H., Seid, M., and Fincham, F. D. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child's perspective: the Children's Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Dev. 63, 558–572. doi: 10.2307/1131346

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., and Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Soc. Indic. Res. 121, 833–847. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0655-1

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd Edn. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Harold, G. T., and Sellers, R. (2018). Annual research review: interparental conflict and youth psychopathology: an evidence review and practice focused update. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 374–402. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12893

Harvey, A. G., Ehlers, A., and Clark, D. M. (2005). Learning history in social phobia. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 33, 257–271. doi: 10.1017/S1352465805002146

Hawker, D. S. J., and Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 41, 441–455. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00629

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jia, Y. R., Zhang, S. C., Jin, T. L., Zhang, L., Zhao, S. Q., and Li, Q. (2019). The effect of social exclusion on social anxiety of college students in China: the roles of fear of negative evaluation and interpersonal trust. J. Psychol. Sci. 42, 653–659. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20190321

Khurshid, S., Peng, Y., and Wang, Z. (2019). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia acts as a moderator of the relationship between parental marital conflict and adolescents' internalizing problems. Front. Neurosci. 13:500. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00500

Ko, C. H., Wang, P. W., Liu, T. L., Yen, C. F., Chen, C. S., and Yen, J. Y. (2015). Bidirectional associations between family factors and internet addiction among adolescents in a prospective investigation. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 69, 192–200. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12204

Kouros, C. D., Cummings, E. M., and Davies, P. T. (2010). Early trajectories of interparental conflflict and externalizing problems as predictors of social competence in preadolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 22, 527–537. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000258

Laible, D. J., Carlo, G., and Raffaelli, M. (2000). The differential relations of parent and peer attachment to adolescent adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 29, 45–59. doi: 10.1023/A:1005169004882

Lepp, A., Li, J., and Barkley, J. E. (2016). College students' cell phone use and attachment to parents and peers. Comput. Human Behav. 64, 401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.021

Leung, A. W., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., and Bruch, M. A. (1994). Social anxiety and perception of early parenting among american, chinese american, and social phobic samples. Anxiety 1, 80–89. doi: 10.1002/anxi.3070010207

Li, C., Sun, Y., Tuo, R., and Liu, J. (2016). The effects of attachment security on interpersonal trust: the moderating role of attachment anxiety. Acta Psychol. Sin. 48, 989–1001. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00989

Li, D., Li, D., and Yang, K. (2020). Interparental conflict and Chinese emerging adults' romantic relationship quality: indirect pathways through attachment to parents and interpersonal security. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 414–431. doi: 10.1177/0265407519865955

Li, J. B., Guo, Y. J., Delvecchio, E., and Mazzeschi, C. (2020). Chinese adolescents' psychosocial adjustment: the contribution of mothers' attachment style and adolescents' attachment to mother. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 2597–2619. doi: 10.1177/0265407520932667

Li, Y., Cheung, R., and Cummings, E. M. (2016). Marital conflict and emotional insecurity among chinese adolescents: cultural value moderation. J. Res. Adolesc. 26, 316–333. doi: 10.1111/jora.12193

Lindsey, E. W., Caldera, Y. M., and Tankersley, L. (2009). Marital conflict and the quality of young children's peer play behavior: the mediating and moderating role of parent–child emotional reciprocity and attachment security. J. Fam. Psychol. 23:130. doi: 10.1037/a0014972

Liu, G., Pan, Y., Li, W., Meng, Y., and Zhang, D. (2017). Effect of self-esteem on social anxiety in adolescents: the mediating role of self-concept clarity. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 25, 151–154. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.01.033

Lu, A., Tian, H., Yu, Y., Feng, Y., Hong, X., and Yu, Z. (2015). Peer attachment and social anxiety: gender as a moderator across deaf and hearing adolescents. Soc. Behav. Pers. 43, 231–240. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.2.231

Manes, S., Nodop, S., Altmann, U., Gawlytta, R., Dinger, U., Dymel, W., et al. (2016). Social anxiety as a potential mediator of the association between attachment and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 205, 264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.060

Manning, R. P. C., Dickson, J. M., Palmier-Claus, J., Cunliffe, A., and Taylor, P. J. (2017). A systematic review of adult attachment and social anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 211, 44–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.020

Mattick, R. P., and Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 36, 455–470. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6

Morrison, A. S., and Heimberg, R. G. (2013). Social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 249–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185631

Mothander, P. R., and Wang, M. (2014). Parental rearing, attachment, and social anxiety in Chinese adolescents. Youth Soc. 46, 155–175. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11427573

Nelis, S. M., and Rae, G. (2009). Brief report: peer attachment in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 32, 443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.006

Pan, Y., Zhang, D., Liu, Y., Ran, G., and Teng, Z. (2016). Different effects of paternal and maternal attachment on psychological health among Chinese secondary school students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 25, 2998–3008. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0463-0

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Qing, Z., Wu, C., Cao, J., Liu, X., and Qiu, X. (2017). Inter-parental conflict and mobile phone addiction: a chain mediating model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 25, 1083–1087. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.06.019

Riggio, H. R. (2004). Parental marital conflict and divorce, parent-child relationships, social support, and relationship anxiety in young adulthood. Pers. Relatsh. 11, 99–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00073.x

Sang, H., and Tan, D. (2018). Internalizing behavior disorders symptoms reduction by a social skills training program among chinese students: a randomized controlled trial. Neuroquantology 16, 104–109. doi: 10.14704/nq.2018.16.5.1312

Schermerhorn, A. C., Cummings, E. M., and Davies, P. T. (2008). Children's representations of multiple family relationships: organizational structure and development in early childhood. J. Fam. Psychol. 22, 89–101. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.89

Shi, M., Li, N., Lu, W. Y., Yu, X. Y., and Xin, S. F. (2019). A cross-temporal meta-analysis of changes in Chinese college students' social anxiety during 1998-2015. Psychol. Res. 12, 540–547.

Stocker, C. M., and Youngblade, L. (1999). Marital conflict and parental hostility: links with children's sibling and peer relationships. J. Fam. Psychol. 13:598.

Tan, E. S., McIntosh, J. E., Kothe, E. J., Opie, J. E., and Olsson, C. A. (2018). Couple relationship quality and offspring attachment security: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Attach. Hum. Dev. 20, 349–377. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2017.1401651

Theisen, J. C., Fraley, R. C., Hankin, B. L., Young, J. F., and Chopik, W. J. (2018). How do attachment styles change from childhood through adolescence? Findings from an accelerated longitudinal Cohort study. J. Research in Personality. 74, 141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2018.04.001

Tu, K. M., Erath, S. A., and El-Sheikh, M. (2016). Coping responses moderate prospective associations between marital conflict and youth adjustment. J. Fam. Psychol. 30, 523–532. doi: 10.1037/fam0000169

Turner, C. M., and Dadds, M. R. (2001). Clinical Prevention and Remediation of Child Adjustment Problems Child Development and Interparental Conflict. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 387–416.

Wang, Y., Li, D., Sun, W., Zhao, L., Lai, X., and Zhou, Y. (2017). Parent-child attachment and prosocial behavior among junior high school students: moderated mediation effect. Acta Psychol. Sinica. 49, 663–679. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00663

Wang, Y. Q., Zou, H., Hou, K., Wang, M. Z., Tang, Y. L., and Pan, B. (2016). The relationships among parent-child attachment, peer attachment and negative affect in adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Psychol. Deve. Educ. 32, 226–235. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.02.12

Weiss, R. S. (1982). “Attachment in adult life,” in The Place of Attachment in Human Behavior, eds C. M. Parkes and J. Stevenson-Hinde (New York, NY: Basic Books), 171–184.

Wen, Z., Hou, J., and Herbert, W. M. (2004). Structural equation model testing: cut off criteria for goodness of fit indices and chi-square test. Acta Psychol. Sin. 36, 186–194.

Wu, Q., and Wang, M. (2014). Relationship among parent-child attachment, peer attachment and anxiety in adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 22, 684–687. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.04.026

Yang, X. H., Yu, H. J., Liu, M. W., Zhang, J., Tang, B. W., Yuan, S., et al. (2020). The impact of a health education intervention on health behaviors and mental health among Chinese college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 68, 587–592. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1583659

Yang, X. J., Zhu, L., Chen, Q., Song, P. P., and Wang, Z. H. (2016). Parent marital conflict and internet addiction among chinese college students: the mediating role of father-child, mother-child, and peer attachment. Comput. Human Behav. 59, 221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.041

Ye, D., Qian, M., Liu, X., and Chen, X. (2007). Revision of social interaction anxiety scale and social phobia scale. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 15, 115–117.

Yu, Y., Liu, S., Song, M. H., Fan, H., and Zhang, L. (2019). Effect of parent–child attachment on college students' social anxiety: a moderated mediation model. Psychol. Rep. 123, 2196–2214. doi: 10.1177/0033294119862981

Zhang, Y. L., Li, S., and Yu, G. L. (2019). The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: a meta-analysis with Chinese students. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 27, 1005–1018. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.01005

Zhao, C., and Dai, B. (2016). Relationship of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in college students. China J. Health Psychol. 24, 1746–1749. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2016.11.038

Keywords: social anxiety, parental attachment, peer attachment, perceived parental marital conflict, Chinese college students

Citation: Adare AA, Zhang Y, Hu Y and Wang Z (2021) Relationship Between Parental Marital Conflict and Social Anxiety Symptoms of Chinese College Students: Mediation Effect of Attachment. Front. Psychol. 12:640770. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.640770

Received: 12 December 2020; Accepted: 05 August 2021;

Published: 06 September 2021.

Edited by:

Leslie Leve, University of Oregon, United StatesReviewed by:

Itziar Alonso-Arbiol, University of the Basque Country, SpainSiti Raba'ah Hamzah, Putra Malaysia University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2021 Adare, Zhang, Hu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuewen Zhang, ei15dWV3ZW5Ac25udS5lZHUuY24=; Zhenhong Wang, d2FuZ3poZW5ob25nQHNubnUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors share first authorship

Aklilu A. Adare

Aklilu A. Adare Yuewen Zhang

Yuewen Zhang Yaqi Hu

Yaqi Hu Zhenhong Wang

Zhenhong Wang