- Department of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

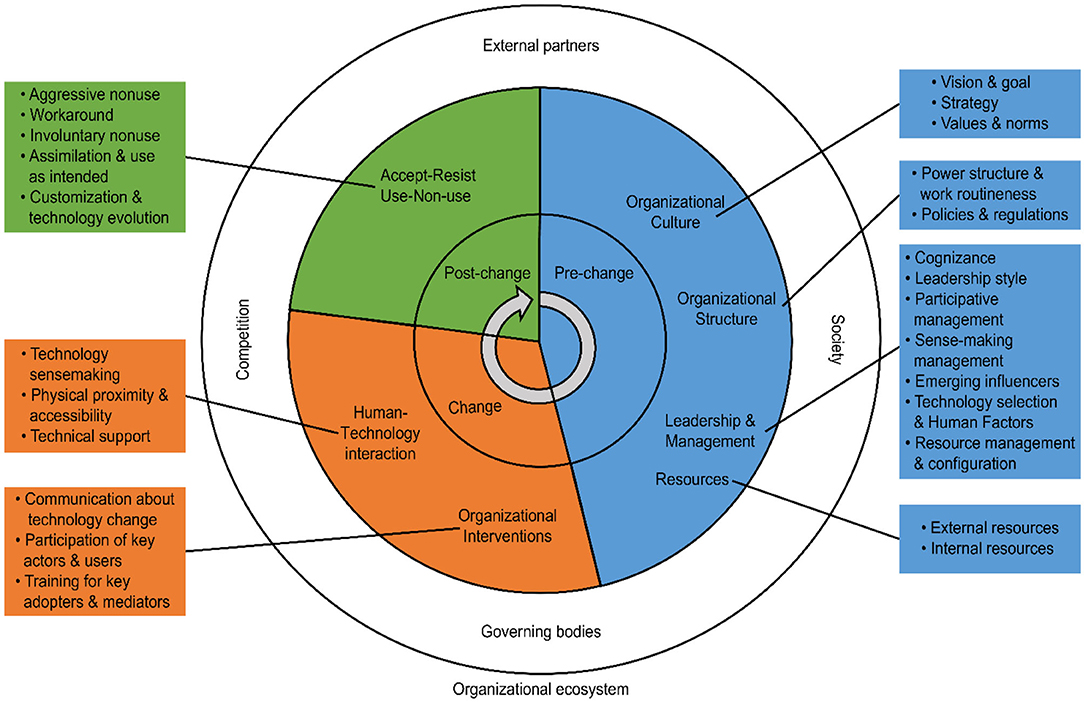

This paper provides a stagewise overview of the important issues that play a role in technology adoption and use in organizations. In the current literature, there is a lack of consistency and clarity about the different stages of the technology adoption process, the important issues at each stage, and the differentiation between antecedents, after-effects, enablers, and barriers to technology adoption. This paper collected the relevant issues in technology adoption and use, mentioned dispersedly and under various terminologies, in the recent literature. The qualitative literature review was followed by thematic analysis of the data. The resulting themes were organized into a thematic map depicting three stages of the technology adoption process: pre-change, change, and post-change. The relevant themes and subthemes at each stage were identified and their significance discussed. The themes at each stage are antecedents to the next stage. All the themes of the pre-change and change stages are neutral, but the way they are managed and executed makes them enablers or barriers in effect. The thematic map is a continuous cycle where every round of technology adoption provides input for the subsequent rounds. Based on how themes have been addressed and executed in practice, they can either enhance or impair the subsequent technology adoption. This thematic map can be used as a qualitative framework by academics and practitioners in the field to evaluate technological changes.

Introduction

The topic of organizational change has received a lot of attention in the past years. There are various kinds of changes and transformations that organizations go through. Organizational changes could be due to merging and acquisition, or cultural, structural, procedural, and technological changes (Smith, 2002). Organizational change management is about taking action toward a defined state through practices that are different from the routine practices (Burnes, 2009; Maali et al., 2020) to reach a goal. The goal of technology change is to offer better products and services through replacing the existing with the new technology (Aremu et al., 2019). The extent to which an organization is able to adapt to required changes is referred to as organizational readiness. With regard to technology changes, readiness encompasses technological infrastructure, knowledge, (human) resources, and managerial commitment to change, and the extent of readiness is a precursor to successful organizational change management (Han et al., 2020; Maali et al., 2020). Therefore, each of the factors that contribute to readiness deserves attention.

Throughout history, there have been three eras of technological advancement, namely the agricultural, industrial, and digital eras (Cascio and Montealegre, 2016). The base of the digital era's technologies is information and communication technologies (Cascio and Montealegre, 2016) that are further divided into three groups: Function IT, which enhances task execution and precision; Network IT, which enhances communication; and Enterprise IT, which redesigns and standardizes workflow. A new era is the fourth industrial revolution, or Industry 4.0, which marks the evolution of technology from mechanical to electrical to digital, and now to even more automation and intelligent networking of systems through smart manufacturing (Lewis and Naden, 2018; Sony and Naik, 2020). Technology adoption and implementation processes in Industry 4.0 are more complex than traditional technology implementations because they involve a wider range of connected technologies, calling for work process readjustments, industrial scale changes, and changes in the society on a global level (Lewis and Naden, 2018). The pace of technological evolution is exponential, and the nature of technologies is more disruptive (Molino et al., 2020) than previous technological eras. This implies that a number of subprojects need to be coordinated and managed strategically (Rojko, 2017). Industry 4.0 has become a topic of great interest among scholars and practitioners since 2013 (Culot et al., 2020). With the rapid advancement of technology, various disciplines and sectors have been influenced by technological evolution. We need to know what we have learned from the past eras of technological advancements to be able to deal with the challenges of the present and future eras. Therefore, an overview of the important factors and their role in technology adoption success is needed. A number of models and theories have been introduced and used in the existing literature. However, they present their findings through different theoretical lenses and they differ in their area of focus and scope. They point to different and sometimes overlapping and rather general factors of the technology adoption process. There is no one overview of all these factors that are mentioned dispersedly in the literature. It is not clear when these factors play a role and when they act as enablers or barriers to technology adoption. Therefore, the following questions arise:

1. What are the main themes (issues/factors) in organizational technology adoption?

2. When do the themes play a role and at what stage of the technology adoption process?

3. How do the themes exert an influence as enablers or barriers?

This paper aims to consolidate different theoretical frameworks, findings, and suggested interventions into one stagewise overview. This will help to emphasize timing in the process, making it easy to create subprojects that can be delegated. Having such an overview will enable us to consolidate new findings from new technological revolutions into the map, updating it with new trends, and to customize it to the internal and external organizational environment. Therefore, it is both general and customizable when applied per industry or organization. The overview will organize these issues into stages, clarifying their role as antecedents or after-effects, enablers, or barriers. The key actors are identified when applicable, and the recommended practices for a better technology adoption process are highlighted. This will help identify future research needs and foci.

In the next section, an overview of the main theoretical frameworks used in past studies is introduced, and an overview of previous findings about influential factors in technology adoption is provided.

Theoretical Background

The current literature has used a number of theories and models for studies related to information systems (IS) and information technology communication (ICT) (Eze et al., 2019). A description of each of them is beyond the scope of this paper, but the most prominent models of technology adoption and change management theory are presented in this section to give an idea of the lenses through which the most prominent factors in technology adoption have been identified to date.

Technology Adoption Models

The models most referred to can be grouped into two categories of individual level and organizational/firm level models. At the individual level, the theory of reasoned action (TRA) by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) posits that a person's behavior, through intention, is influenced by their attitude and their perceived subjective norms about that behavior. Attitude is shaped by the personal belief and view of the behavior, while the subjective norms is about how other's evaluations are perceived and form motivation to engage in a behavior (for a more detailed overview, see Dwivedi et al., 2012). This model was adopted from the field of psychology into IS models (Dwivedi et al., 2012). The model was improved into the theory of planned behavior (TPB) by Ajzen in 1985, and builds on TRA by including perceived behavioral control (PBC), which is important when actions are not under full volitional control. “According to the theory of planned behavior, perceived behavioral control, together with behavioral intention, can be used directly to predict behavioral achievement” (Ajzen, 1985, p. 184).

Another widely used model is the technology acceptance model (TAM) developed by Davis (1989). It has been considered a “powerful tool to represent and understand the determinants of users' IT-acceptance process” (Dwivedi et al., 2012, p. 167). This model posits that intention to use technology is affected by attitude, which in turn influences perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU). PU is based on the belief as to whether the application or innovation helps people perform their job better and helps them improve task performance. PEOU refers to the evaluation of whether or not using the application is worth the effort (Dwivedi et al., 2012). PU is also influenced by PEOU (Dwivedi et al., 2012).

An improvement was made to TAM by incorporating more consumer-related factors (Slade et al., 2015), leading to the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) by Venkatesh et al. in 2003 in acknowledgment that the determinants of acceptance of technology vary across models. The authors studied some of the main models in the IT field to create UTAUT. It postulates that acceptance and behavior are directly determined by performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. The effect of the core constructs is moderated by age and gender, experience, and volition of use (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Both TAM and UTAUT have been criticized for not capturing the complexity of technology adoption adequately, for being too focused on individuals' beliefs and perceptions, and for having reached a plateau of how much they can contribute to the field of technology adoption (Shachak et al., 2019), which is rapidly evolving and expanding.

Diffusion of innovation (DoI), developed by Rogers (1995), focuses on both individual and firm level technology adoption. It integrates three major components: adopter characteristics, innovation characteristics, and the innovation decision process. In the innovation decision step, there are five steps, namely knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation, that are influenced by communication channels among the members of a similar social system over a period of time. Perceived characteristics of innovation include five main constructs—relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability—that have been proposed as factors affecting any innovation acceptance. In the adopter characteristics step, five categories are defined: early adopters, innovators, laggards, late majority, and early majority (for more details, see Baker, 2012 in Dwivedi et al., 2012). Therefore, this model takes into account not only the features of technology, but also individual characteristics and organizational processes. This model is consistent with another firm level model, the technology, organization and environment framework (TOE) developed by Tornatzky and Fleischer (1990). However, the TOE also incorporated the environmental context into the model, which is an advantage over the DoI (Oliveira and Martins, 2011). This model tries to show how technology innovation decision-making is affected by the technological context (technology characteristics and availability), the organizational context (formal and informal linking structure, communication, size, and slack), and the environmental context (market and industry structure, technology support and infrastructure, government regulations) (for more details, see Baker, 2012). The technological context is concerned with the equipment and practices internal to the organization as well as externally available technologies, and draws attention to the disruptiveness of new technology and adoption risks (Baker, 2012). The organizational context is about the organizational structure, management, resources, and processes, and how they affect innovation adoption in organizations. The environmental context is the arena in which the organization operates (Oliveira and Martins, 2011) and how factors such as governmental policies regarding safety or efficiency, industrial maturity and its effect on the strategy for innovation, and the presence and capacity of technology providers influence technology adoption and implementation (Baker, 2012). While DoI is more about the antecedents and determinants of technology adoption, TOE is more about the contextual factors (Oliveira and Martins, 2011).

These models are often used in the literature, especially in the IS, management, and health sectors. However, regarding technology adoption, TRA and TPB do not account for many factors relating to the technology itself and there is no clear indication of the different stages of the adoption process involved. TAM and UTAUT are at the individual level of adoption, while DoI and TOE are applied at the organizational level (Oliveira and Martins, 2011). They deal with many organizational structure factors and contextual factors (Oliveira and Martins, 2011), but there is not enough emphasis on interventions such as training and participation that require the more active engagement of users and leaders in the change process. The next section provides an overview of some of the change management models that could highlight the role of leadership and intervention.

Organizational Change Management Theories

Technology adoption is not a passive process: it requires active leadership engagement. Therefore, it is also important to look at some of the prominent models of change management. “Change management is the process of continually renewing an organization's direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal stakeholders” (Moran and Brightman, 2000, p. 66). One of the oldest models of change management is the three-step “unfreeze,” “change,” and “refreeze” model of change introduced by Lewin (1947) (Cummings et al., 2016). This approach was further elaborated by Schein and was regarded as a cognitive redefinition, learning to think in a new way (Schein, 1999). The first step (unfreezing) involves creating motivation and readiness for change by creating a balance between perceived threats of change and the perceived psychological safety to embrace change (Schein, 1996; Wirth, 2004). The second step (change) involves the identification of what needs to be changed and what should be the outcome, and it can benefit from observing role models that have achieved the desired state, or mentors, as well as learning through trial and error and thus scanning the possible solutions to enhance learning and coping with ongoing change (Schein, 1996; Wirth, 2004). The third step (refreezing) involves habituations and maintenance of the new behaviors consistent with the change through the development of a new identity and relationships within the broader cultural context (Wirth, 2004).

Kotter (1996) introduced a model of change implementation involving eight steps: (1) create a sense of urgency; (2) create a guiding coalition; (3) create a vision and strategy; (4) communicate the change vision; (5) empower broad-based action; (6) generate short-term wins; (7) consolidate gains and further changes; and (8) anchor change into the culture (for more detail, see Kotter, 1996; Appelbaum et al., 2012). Armenakis and Harris (2009) developed a model focused on creating change readiness. The model consists of five components: (1) discrepancy, which is about depicting a difference between the current state and the potential future state; (2) efficacy, which is about creating trust in the ability to accomplish the change goals; (3) appropriateness, which is concerned with being convinced that the change solution is the best solution; (4) principal support, which is about the provision of support during the change; and (5) personal valence, which addresses the perceived personal benefit in the change process. In order to reinforce the five components, seven strategies are mentioned. These strategies are management of information, persuasive communication, formalization of activities, human resource practices, diffusion practices, rites and ceremonies, and active participation (Armenakis and Harris, 2009; Sætren and Laumann, 2017).

Cummings and Worley (2015) presented a five-step model for effective change management including the following steps: (1) motivating employees for change; (2) creating a vision to clarify the why and what of the change; (3) providing political support for change and preventing individuals and groups from blocking the change; (4) managing the transition through planning of activities and maintaining commitment; and (5) sustaining momentum through resource management, change agents, support systems, and skill development (Cummings and Worley, 2015).

There are certain overlaps between these models, but they are not specific to technology and innovation management and interventions. Nevertheless, incorporating the theories about how to manage change into an overview of different perspectives on technology adoption and use at the firm level could create a more comprehensive overview of the entire process of technology introduction and use, from preparing for technology change to maintaining technology use. Many of these frameworks have been used in the literature. An overview of the recent findings is presented next.

Existing Literature

There have been numerous studies on the topic of technology adoption and implementation. A review of the important factors in technology adoption in Industry 4.0 highlighted strategic management and goal setting, employees, the digitalization and harmonization of technology, change management, and cyber security management (Sony and Naik, 2020). There was no clear stagewise division, but the importance of timing was indicated by emphasizing implementation in a timely manner. With regard to time, having a realistic timeframe that accounts for the unpredictable obstacles during the process was noted, and the need to adjust workloads at a given time was indicated (Maali et al., 2020).

Most research has stemmed from IS and ICT (Eze et al., 2019) in accordance with the third era of technological revolution (Cascio and Montealegre, 2016). A number of facilitators and barriers are proposed. Literature reviews have shown that organizational culture, strategy, and resources management should be aligned to minimize obstacles to adoption (Kumar et al., 2018; Mohtaramzadeh et al., 2018; Shin and Shin, 2020). However, the obstacles are not clearly distinguished and the mechanism of adjusting the culture and strategy is rather abstract. In other studies, internal upper management support was found to a prominent factor (Chung and Choi, 2018; Lu et al., 2018; Mohtaramzadeh et al., 2018; Maali et al., 2020; Ukobitz, 2020). Furthermore, awareness of the state of affairs in the organization's external environment was found to be essential (Mohtaramzadeh et al., 2018; Vaishnavi et al., 2019). Organizational structure was found to impact technology adoption (for more detail, see Aremu et al., 2018). Other studies have pointed out the importance of change agents and influential and senior users (Keyworth et al., 2018; Molino et al., 2020) in forming normative pressure and influencing the perceptions of other users (De Benedictis et al., 2020). Communicating the reasons for change and provision of training were also mentioned as important facilitators of technology adoption (Maali et al., 2020; Molino et al., 2020). The importance of focusing on the users and users' beliefs as a facilitator of adoption (Mohammed et al., 2018) was mentioned in the literature review by El Hamdi and Abouabdellah (2018). Other studies have suggested that technical issues and technical maturity can be barriers to successful technology change (Keyworth et al., 2018). The importance of a work environment that is supportive to the employees, the participation of skilled key actors, and fostering cross-functional teamwork were mentioned in the study by Kumar et al. (2018). The study by Eze et al. (2019), identified the major factors of adoption as technology's ease of use, a focus on the users, and management. Eze et al. (2019) pointed out that the process of technology adoption is a dynamic process. None of the stages is static, and therefore the different factors involved can influence the adoption process at different stages (Eze et al., 2019). In addition to the aforementioned factors and the dynamic nature of the technology adoption process as posited by Eze et al. (2019), it is important to highlight that when people engage with technology and interact with it, they adapt to it in different ways, showing different outcomes of the use (Schmitz et al., 2016) and application of technology. This is even more complex in today's sociotechnical systems (Lewis and Naden, 2018).

Most of the recent work and reviews show failure in organizational technology adoption and low technology usage (Decker et al., 2012; Sligo et al., 2017). The existing reviews mostly consider the same models of technology adoption embedded in IS field (Hwang et al., 2016; Koul and Eydgahi, 2017; Lai, 2017). Fewer studies have focused on firm level technology adoption (Oliveira and Martins, 2011) than on individual technology adoption. In the existing models and theories on how to manage technology change, the terms “antecedent” and “after-effects” are not clearly distinguished. The studies on antecedents of success and failure are inconsistent (Decker et al., 2012). Therefore, what can be considered as antecedent to success can also be antecedent to failure, which implies these antecedents can be both enablers of success and barriers to it. According to Decker et al. (2012), these antecedents are rooted in different theoretical foundations and can include cultural factors, decision-making processes, and power hierarchy, leadership, and past change failures. Other reviews have offered a detailed account of barriers (Kruse et al., 2016), but it is not clear to which stage of change they belong. The stages of change are not always clearly defined in the reviews, and therefore it is difficult to consolidate the findings from different reviews into a chronological and consistent overview to help identify antecedents and after-effects, enablers, and barriers. Furthermore, the prominent models and theories either target restricted aspects and stages in the technology adoption process with respect to the interest of that specific discipline and without capturing the broader organizational ecosystem, or they are too broad and do not pinpoint the specific issues at particular stages that one needs to be aware of while studying technological adoption processes. The desired outcome is mostly the displayed usage behavior. Usage does not show what users actually think about the new technology, how it was implemented, and how they will incorporate that into future technology rounds. These theories imply a linear process, while Industry 4.0 highlights a need for constant change that is more complex than a mere linear process. Furthermore, the change theories present guidelines and advice for managers on how to implement change from a managerial perspective, and the experience of technology adopters and the broader organizational ecosystem is not clearly stated. Nevertheless, the models have important components that can be integrated into one general overview accounting for both individual level and firm level adoption. It is important to map the existing findings about the technology adoption process in order to be able to evaluate the process and practices against the emerging challenges of technology adoption and its complexities, as characterized by the new technological era (Oliveira and Martins, 2011; Culot et al., 2020). This will help identify new areas of research about where and when improvements are needed and how can they be implemented.

There is a wide range of theoretical frameworks and issues to consider when introducing new technologies in organizations. As such, the motivations for this research and for a qualitative approach were: (1) the lack of one comprehensive overview in the literature of all the issues and themes at different stages of organizational technology adoption; (2) the lack of clarity of when and how these issues acts as enablers and barriers, antecedents and after-effects, and the inconsistent use of terminology; and (3) the broad scope of the research question about a complex system and the need to identify and map the issues mentioned in the literature can be better explored through a qualitative approach to literature review. This literature review aimed to identify and map the scope of the existing literature and it was based on systematic review protocol (Munn et al., 2018). The map can be used for further detailed investigations and systematic literature reviews (Bramer et al., 2017). The aim is to present a stagewise thematic map of important themes and issues to consider from pre-change to post-change, with consideration for future technology change rounds. The map covers issues ranging from selection to acceptance, adoption, and implementation by the stakeholders involved. It is transferable across disciplines. It can be used as a tool to analyze how the relevant themes might influence the technology adoption process by acting as enablers or barriers, and how themes in one stage become antecedents to the themes in the subsequent stage.

In the following section, the materials and method used for the literature search are presented, followed by the data analysis. The results and discussion of the themes, and a thematic map thereof, are presented after that, followed by a general discussion and the conclusion of the paper.

Method

The data were collected through a search of literature in recent publications that addressed themes relating to organizational technology acceptance and adoption. Qualitative analysis was chosen due to the explorative nature of the research question. Qualitative analysis in this case provides an overview of all the themes that should be investigated when adopting a new technology. This paper is a literature review based on qualitative and quantitative research. It attempts to map and identify the main themes and to provide information that can be used by researchers and practitioners seeking to gain an overview of contemporary technological adoption issues in organizations.

Literature Search

The literature review was carried out based on qualitative research methods in order to ascertain which issues (qualitative) or factors (quantitative) influence technology adoption and use in organizations. A Boolean search was conducted in databases containing electronic journals, including ISI Web of Science and PsycINFO. A combination of search terms was used, including:

Organizational change AND (technology adoption/ technology readiness/ technology acceptance/ technology endorsement/ embrace/ approval/ reception/ maturity/ willingness/ undertaking)

The truncated forms of these terms were also searched. Truncation was applied by using the asterisk function, and an exact phrase search was conducted using the double quote character. ISI Web of Science and PsycINFO were chosen because they have peer reviewed publications from various fields and mainly technology and social sciences, which would be most suitable for the topic of the paper. ISI Web of Science provided relevant articles, selected by humans rather than robots, from disciplines that were closely related to the topic of the research presented in a wide range of journals. PsycINFO provided the psychological and organizational psychology point of view for the development of the thematic map. This will also enhance transferability, as more disciplines and research fields are represented in the thematic map. Furthermore, they allow for conducting a Boolean search, which is quite helpful in using different search terms. The search period was limited to publications from 2013 to the end of 2020, the reason being that this period saw the start of publications on Industry 4.0 adoption (Culot et al., 2020). However, additional sources beyond this time period were used to elaborate on the main concepts and definitions of the themes and subthemes that resulted from an analysis of the selected articles.

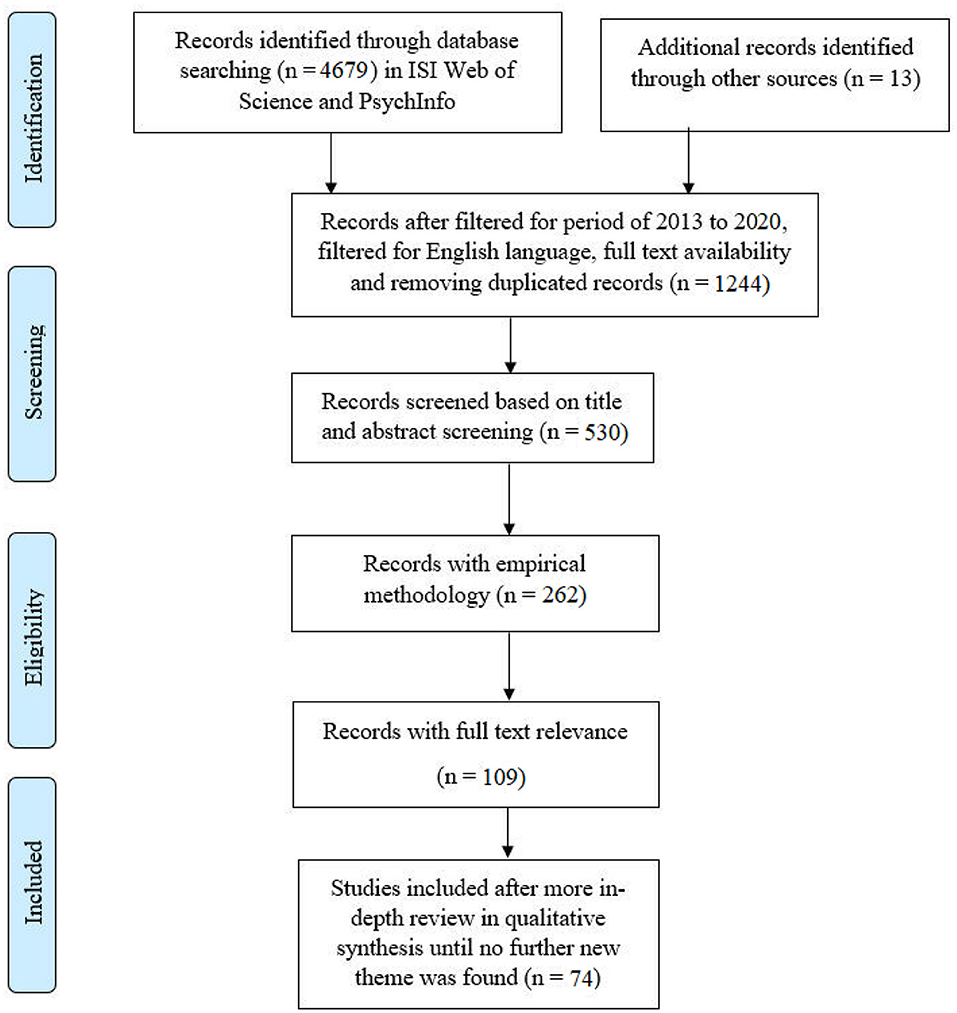

Conducting the review started with developing the search terms, then entering them in the ISI Web of Science first, retrieving the results, filtering for the years 2013–2020, filtering for English language and full text availability, and transferring the remaining publications to the library. The same procedure was applied to the PsycINFO database. The resulting records were added to the library. Duplicated records were continually removed from the library as new sources were added over the period of data collection; the removed duplicates were not recorded. The publications were screened by title and abstract relevance where articles indicated or implied factors and issues affecting technology use in organizations, including tangible and intangible technologies. Next, the selected articles were filtered for empirical methodology. Theoretical papers were not considered. In order to embed the research in evidence, publications that used qualitative and quantitative methods to obtain their results empirically were chosen as opposed to theoretical papers where we are not certain to what extent they have been verified. This adds to the credibility and trustworthiness of the data used to develop the thematic map. The result was 262 peer-reviewed articles. They were read in full and evaluated for relevance to the topic of the review (issues affecting technology use and adoption); if the article introduced an issue or factor that was found to be important or related to technology uptake in the organizational setting, then it was included in the in-depth analysis. The resulting papers were imported to NVivo 12. Critical reading of articles and evaluation of fit were conducted (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013). This resulted in 109 articles. At this stage, data analysis started in the form of coding. This process is explained in further detail below. However, it is important to clarify that data analysis included 74 articles before establishing saturation. See Figure 1 for an overview of the process inspired by the PRISMA model (Moher et al., 2009) to show the data collection process.

Figure 1. Overview of the steps taken to conduct data collection and the criteria for inclusion of sources to be analyzed.

While saturation is generally viewed as “a criterion for discontinuing data collection/or analysis” (Saunders et al., 2017, p. 1894), there are different approaches to it. In this paper, saturation was reached when new papers did not lead to the emergence of a new code or theme, which is consistent with the inductive thematic saturation model (Saunders et al., 2017). This is when the data only feed into the existing codes and do not result into any new codes (Urquhart, 2013), new themes (Given, 2016), or new theoretical insights (Saunders et al., 2017). In this paper, the articles considered for data analysis were categorized primarily according to the database from which they were collected, starting with ISI Web of Science, which has a larger collection and is more multidisciplinary. When the articles ceased to reveal a new theory, thematic map, or concept that was not already covered in previous publications or whose constituent elements had not already been addressed, saturation was assumed. This was reached after 74 articles had been analyzed. A further three articles were added from the references to explain the themes and subthemes in more detail.

It must be acknowledged that it is not possible to establish absolute saturation: it should not be viewed as an absolute point that the researcher reaches, but rather a process in which the researchers establish a degree of saturation that they consider to be enough, knowing that it is always possible to have new and emerging codes and themes (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). However, if adding new data ceases to contribute anything new, data collection becomes redundant (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Saunders et al., 2017). There is always a possibility that certain information regarding different themes and subthemes, different dimensions of a code, and disconfirming evidence derived from the data may have been excluded. According to Saunders et al. (2017, p. 1903), “an uncertain predictive claim is made about the nature of data yet to be collected.” There is a large volume of publications on this broad research topic, and one can never claim that all the publications that could have some sort of relevance have been reviewed or included.

Data Analysis

In this paper, thematic analysis was conducted because of the advantages of this method. “Through its theoretical freedom, thematic analysis provides a flexible and useful research tool, which can potentially provide a rich and detailed, yet complex, account of data” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 78). This method allows for “identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organizes and describes your data set in (rich) detail” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 79). Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 82) posit that “a theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” The importance of the theme or “the ‘keyness’ of a theme is not necessarily dependent on quantifiable measures … but rather on whether it captures something important in relation to the overall research question” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 82).

Conducting thematic analysis is best done through the six phases of thematic analysis as indicated by Braun and Clarke (2006), which can overlap with other methods of qualitative research such as grounded theory. This phasic approach to conducting thematic analysis is merely a guideline and not a strict protocol and rules about conducting analysis. However, it provides a systematic and iterative approach. In phase one (familiarizing oneself with the data), the publications were screened and later thoroughly read to ensure prolonged engagement with the data set. In the second phase (generating initial codes), initial ideas about what the smallest meaningful unit of text could be, and the pattern observed in the text across different publications, were captured through codes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Open coding was done on the texts in a systematic way, and the codes were constantly reviewed and adjusted throughout the process with other research team members to ensure trustworthiness. Codes were categorized into groups in phase three (searching for themes), and different groupings and hierarchical structures were reviewed to make sure that the resulting structure was consistent and captured the different codes derived from the data. This was reviewed and adjusted in collaboration with other research team members in an iterative process in accordance with phase four (reviewing themes). The identified themes and subthemes were reviewed for naming and grouping in accordance with phase five (defining and naming themes), and the results were reported in phase six (producing report). For more details, see (Bowen et al., 1989).

Thematic analysis has different approaches. In this paper, inductive thematic analysis was chosen, where the codes and the themes are developed from the data. Semantic coding was initially applied. “With a semantic approach, the themes are identified within the explicit or surface meanings of the data, and the analyst is not looking for anything beyond what a participant has said or what has been written” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 84). In the next step, latent coding was performed to identify the more subtle and latent meanings and patterns. Analysis at the latent level “starts to identify or examine the underlying ideas, assumptions and conceptualizations … and ideologies … that are theorized as shaping or informing the semantic content of the data” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 84). Latent coding uncovers the overlapping themes and the various terminologies assigned to the same concepts. For example, in the article by Parris et al. (2016), they state that “Market demands and threats posed by competitors are primary stimuli for firms to explore innovation as [a] means to change.” This unit of text can be coded to the theme of external environment, as it reflects how an organization will be influenced to adopt a change by its environment. The themes and subthemes were then organized into a thematic map to show an overview of “the relationship between codes, between themes, and between different levels of themes” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 20). Through this map, our view of the order of the main themes and subthemes in the different stages of technology adoption and implementation is depicted (see Figure 2). In order to provide an overview of the data used for analysis, a descriptive account of the data with regard to the percentage of the references representing each sector, region, and method used was also prepared.

Figure 2. Thematic map of organizational technology selection, adoption, and intervention themes in the pre-change, change process, and post-change stages.

This research took place within the post-positivist paradigm, which posits that reality exists, but it is difficult or impossible to determine whether true reality has been found: it is “imperfectly apprehendable” (Guba and Lincoln, 1994, p. 110). In this paradigm, the research process cannot be purely objective and unbiased due to the researcher's role in the design, data collection, and interpretation, which influences the research process (Clark, 1998; Milch and Laumann, 2018).

Results and Discussion

In this section, the resulting themes of the literature analysis are presented in a thematic map in three stages. The first stage represents the pre-change or background state, meaning what the organization is like before the introduction of the new technology. The second stage is the change process stage, which includes organizational interventions to support the ongoing change and human-technology interaction. The third stage represents the post-change or outcome of the technology adoption. A detailed overview of the stages, themes and subthemes, and references is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

The overview also shows the percentage of different sectors represented in the thematic map. The sector of management, business, and economics was represented the most, with 35 percent of all the references. In terms of region, North America (37%) was the prominent sector. As for the method, the references were mostly qualitative (45%). An overview of the descriptive analysis of the publications used for thematic map is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Pre-change Stage

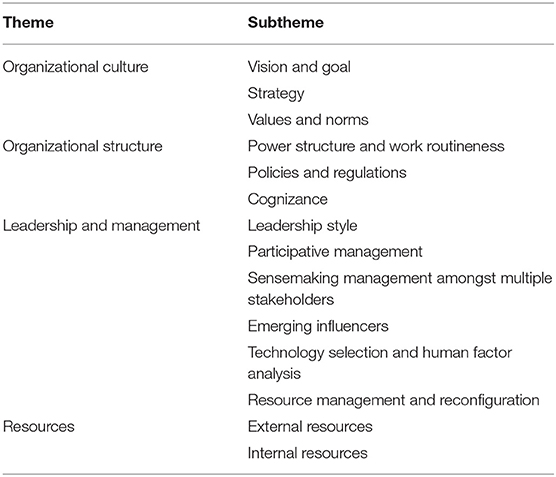

In this section, the themes and subthemes in the pre-change stage are discussed. This is the state of organizations prior to technology adoption. The current state of the themes in the organizations have been shaped by past change processes and these themes play a role in future change processes. The main themes from the literature review that were placed under the pre-change state are organizational culture, organizational structure, leadership and management, and resources (see Table 1). Each of these themes consists of subthemes. A description of the main themes and subthemes is presented in Table 1.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is a very broad theme that has been discussed expansively in the literature. It is the foundation of the organization and is essential as it permeates all the functions of the organization, including technological changes. There are different types of organizational culture (see Shin and Shin, 2020), but none of the frameworks captures all aspects of organizational culture. Organizational culture has been mentioned as the main barrier to change (Belisari et al., 2020). The main subthemes for organizational culture derived from the literature that are found to influence technology adoption are presented here: they include vision and goals, strategy, and organizational values and norms.

The subtheme of vision and goals is important as it sets the direction and focus of the organization. Vision refers to the long-term clear and coherent view of the future state of the organization. Having a common long-term vision across the organization inspires acceptance of changes to achieve the desired state, but if there are competing visions, there will be division as to what should be done and how (Taylor et al., 2015), which could impair the change process. The vision and the goals should ideally be coherent because goals help achieve the vision by forming the basis of objectives, policies, and organizational guidelines (McKenna, 2006). We believe that when planning to adopt a new technology, it is important to consider whether the organization has successfully established a shared vision and set of goals across its echelons that foster the adoption of new technologies. Furthermore, we need to consider whether the purpose of that particular technology is aligned with the vision and goals. If not, adjustments need to be made to the choice of technology. When the vision and goals are clear, respective strategies to adopt technological changes should be put in place to reach the goals. In addition to that, goal congruence between management and employees is important in facilitating technological change and overcoming possible political barriers to technology acceptance and eventual performance (Obal and Morgan, 2018).

The subtheme of strategy reflects on how an organization positions itself with respect to internal and external technological changes. We sorted the different strategies described in the literature into inertia, reactive, proactive, and isomorphism. Inertia refers to an intentional non-response to the changing environment because there is no threat or opportunity in adopting the change (Wang et al., 2015). A reactive strategy to change refers to the lack of an effective response mechanism to external changes, causing instability and avoidance of confronting the future (Miles et al., 1978). An organizational culture characterized by an external focus benefits from higher awareness and adoption of advanced technologies (Shin and Shin, 2020). A proactive strategy is about developing greater efficiency in adopting change or exploring the external environment for new opportunities, also known as a prospective strategy (Miles et al., 1978). Isomorphism is when organizations take up new technological changes due to normative, mimetic, or coercive pressure exerted by their external environment (for more details, see Parris et al., 2016). We believe that a proactive strategy could be the best approach, followed by isomorphism, to cope effectively with rapid technological advancements in the global market, while inertia and reactive strategies could eventually make the organization obsolete and unable to compete in the market. To enact the right strategy, the right norms and values should be created. This is discussed further under the next subtheme.

The subtheme organizational values and norms is an important part of the literature, as the success of technology adoption is partly due to showing respect for cultural norms during the process (Ford et al., 2016). Norms and values are the taken-for-granted guiding principles that help people understand what is acceptable and what is unacceptable. These patterns will be passed on to new members to guide them in their thinking, perceiving, and feeling (2, 1990; Moorhead and Griffin, 2004). Two of the most important norms and values regarding technological change found in the literature review are presented here. The first is the norm of learning and innovativeness. This will enable members to develop new skills and competencies that help these continuously learning organizations to undergo constant renewal (Tamayo-Torres et al., 2016). The term “knowledge management” was mentioned in the literature as a recommended practice by which a member's knowledge can evolve into team and organizational knowledge (Han et al., 2020). The more knowledge is built and shared, the more readily the organization will adopt new technologies and the more likely it is to survive. The second norm or value is the value of knowledge-sharing, which facilitates knowledge transfer and collaboration amongst stakeholders by removing barriers such as cultural differences and language barriers (Tseng, 2017), enhancing collaboration to meet the challenges of adopting new technologies. To enforce a constructive strategy toward technology change, organizations must reconsider their existing norms and evaluate whether these norms make employees motivated to try new approaches and solutions, share their knowledge, and learn from their co-workers. This could potentially create a bottom-up willingness to adopt new technologies rather than a top-down decision by the management, and increase technology acceptance and use.

Understanding organizational culture is important for many purposes. It is at the foundation of any change and, in this paper, we have tried to provide an overview and suggestions as to how vision and goals, strategy, and values and norms should be understood and aligned with the purpose of change. It is important to emphasize that having a vision for more advanced operation by means of technology, having organizational goals related to technology introduction and use, adopting a proactive strategy that encourages the employees to take more initiative in adjusting and using new technologies, and implementing norms of knowledge sharing and collaboration and innovativeness will facilitate ongoing and continuous technology adoption and use in organization.

Organizational Structure

When we have established the right the norms and values, the next step is to consider whether the organizational structure supports acting upon these norms. The structure of an organization determines how individuals work together toward a common goal. The most relevant subthemes to consider under this theme include power structure and work routineness, and policies and regulations.

The subtheme of power structure and work routineness refers to the hierarchical structure and diversity in work tasks. According to Bruns and Stalker (1961), organizations can be placed on a continuum ranging from a mechanistic to an organic structure. A mechanistic system is one in which tasks are highly specialized and communication is carried out through the chain of command. It is suitable in times of relative stability. An organic structure, however, is more suitable in times of change and a turbulent market (McKenna, 2006). An organic system is less hierarchical. Communication is not hierarchical. There is more task diversity and autonomy. Therefore, people are more engaged and innovative (Avadikyan et al., 2016) and there is better communication and coordination of tasks and staff at a lower cost (Bruns and Stalker, 1961; Miller, 1986; Bowen et al., 1989; Bahrami, 1992; Youngdahl, 1996). Other terminologies used for this concept in the literature include centralized vs. decentralized (see Wang and Feeney, 2016) and formal vs. informal power structures (see Peir and Meliá, 2003). It is worth highlighting that the relationship between organizational size and technology adoption is not clear, since it is argued that large organizations have more resources for faster technology adoption while small organizations have less bureaucracy and structural complexity that could slow down the adoption of technology (Han et al., 2020). We believe that when organizations have a more organic structure during technology adoption, the employees are more engaged and communicative. They are more likely to be innovative and to feel more secure and willing to share and acquire knowledge from others. This can enhance acceptance and adoption speed. However, as mentioned earlier, an organic structure works best during the time of change.

The state of change also requires having regulations and policies that would help the transition which brings us to the subtheme of organizational policies and regulations. Organizational policies should be adjusted to the circumstances arising from new technology to ensure a smooth adoption process. Organizations must be able to monitor and solve any potential problems and concerns that may arise during the process. This can be achieved through assembling governing bodies and project teams to develop policies for times of change that will address safety, security, and protocols for handling complaints (Wells et al., 2015), helping the adopters to adjust and to be compensated for the time lost and not punished for possible errors and compromised productivity during the change process.

Leadership and Management

“Leadership is a process by which an executive can direct, guide and influence the behavior and work of others toward the accomplishment of specific goals in a given situation” (Iqbal et al., 2015, p. 2). The role of leadership and management in innovation is essential, as reflected in the subthemes found in the literature review, including managerial cognizance, leadership style, participative management, sensemaking amongst multiple stakeholders, resource management and reconfiguration, technology selection and human factor analysis, and emerging influencers.

The subtheme of cognizance refers to the managerial ability to direct attention toward technological and market changes and to provide the necessary conditions to embrace change and remain competitive (Tamayo-Torres et al., 2016). The increased technological changes and complexities of the modern economy call for managers' constant scrutiny and investigation of the market (Eze et al., 2019). This also implies that managers themselves should have the cognitive ability to adjust to these changes and have a sense of efficacy in meeting the demands of restructuring, re-engineering, and modifying operational processes (Wang and Feeney, 2016). We believe that cognizance is important because it implies awareness of what is happening and how it affects organizational changes. With this awareness, management can adopt a suitable leadership style to navigate the change.

The next subtheme is therefore leadership style, the two most prominent being transactional and transformational leadership. This topic has been a widely studied topic in the management literature. Transactional leadership is “characterized by contingent reward and management by exception” (Schepers et al., 2005, p. 498) and is suitable for stable conditions. Transformational leadership, introduced by Bass (1985), refers to a style that is inspirational and motivates employees, raises their awareness, creates a long-term vision, and adjusts the system to foster creativity and productivity. As such, it helps with technology acceptance (Howell and Avolio, 1993; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016; Tseng, 2017). Transformational leadership was mentioned as the most suitable style for the implementation of complex technological changes, as characterized by Industry 4.0, which requires consideration of adopters' needs (Sony and Naik, 2020). Transformational leadership has a positive relationship with technology acceptance (Farahnak et al., 2020). Transformational leadership is related to participative management, which shows how this style can be put into action.

The participative management subtheme concerns the extent of management support and commitment, availability, and openness to continuous dialogue, leading to the success of organizational change (Andersen, 2016). The management shows support by being committed to the vision (Martins et al., 2016) and providing both the material resources and the internal political resources (Zhang and Xiao, 2017). Being committed, creating milestones, and celebrating achievements throughout the process enhances change momentum (Maali et al., 2020). A risk factor in the adoption process is the rapid pace of technology implementation compared to the organization's capacity and potential to adapt (Vrhovec et al., 2015). Management's participation will lead to an awareness of the increased pressures on the stakeholders involved. Consequently, they will be able to act so as not to seem apathetic in the face of the increased workload (Vrhovec et al., 2015). By showing awareness and consideration, the management can influence the perception of the stakeholders involved. This brings us to the following subtheme.

The next subtheme under leadership is sensemaking management amongst multiple stakeholders. Handling multiple stakeholders requires a certain level of soft skills (De Carvalho and Junior, 2015). A manager should map the external and internal stakeholders in technology adoption, consider their competing vision and goals that will lead to mixed opinions about using the technology (Taylor et al., 2015), and adjust their discourse. The leaders should understand their audience's cost-benefit evaluation and address the concerns of the stakeholders accordingly. In doing so, managing the perception of fairness is important (Jiao and Zhao, 2014). The new system may segregate a group of users due to an incompatible level of knowledge and skill, and unequal participation and training opportunities. This marginalization may, over time, create prejudice, and bias in the organization (Andersen, 2016) that influences the stakeholders' sensemaking. Therefore, management must address the concerns of stakeholders based on the different stakeholders' perceptions of costs, threats, and fairness through tactful communication (Costa et al., 2014) and the involvement of stakeholders in decision-making to avoid multiple interpretaions (Heath and Porter, 2019). The management may also appoint appropriate change influencers (Taylor et al., 2015) to better manage the sensemaking of multiple stakeholders.

The next subtheme is that of formal and informal emerging influencers (change agents, champions, opinion leaders). A change agent, or influencer, is a person charged with managing the change efforts for a group in which they have a certain level of influence, especially among those employees that are dissatisfied with the change process (McKenna, 2006). They are also referred to as opinion leaders and have been found to affect the technology adoption behavior of employees (Hao and Padman, 2018). These influencers can enhance or impede the diffusion and success of the change. They can inspire people through a tailored discourse (Kim, 2015), spread awareness, and promote the adoption of technological changes (Taylor et al., 2015). However, they may also emerge because of abdicated leadership and may steer the change process in their own desired direction (Andersen, 2016). This highlights the importance of managers' awareness of informal power structures in an organization and the management's close involvement in order to prevent derailment of the change process.

The next subtheme is technology selection and human factor analysis. Managing sensemaking is not just about the people, but also about selecting a technology that “makes sense” and is usable from the start. One of the more recent issues found to influence successful technology use in Industry 4.0 was concern about choosing a system that offers well-integrated cyber security measures. Sony and Naik (2020, p. 809) mentioned that “The successful implementation of Industry 4.0 will depend on the successful implementation of [a] cyber-security strategy.” This subtheme is about choosing the most suitable technology for a desired outcome and conducting the relevant human factor analyses. In the literature, a common problem was found to be that human factors received limited attention compared with technological aspects (Molino et al., 2020). Lack of consideration for human aspects jeopardizes successful technology implementation (Heath and Porter, 2019). “Technological development could benefit from including human factors experts from the project's outset to bridge the gap between the lack of relevant information and sufficient information on which to base development decisions” (Sætren et al., 2016, p. 595). This is crucial in the pre-change stage because insufficient evaluation of the new technology's usability and viability may lead to a costly failure. Consideration of human factors was found to ensure a more user-friendly system (Keyworth et al., 2018), better integration of the new technology into the existing workflow, and work process optimization (Heath and Porter, 2019). It was mentioned in the literature as a critical success factor in technology change implementation (Efremovski et al., 2018; El Hamdi and Abouabdellah, 2018). Viability analysis helps managers make better decisions by detecting opportunities and threats of the new technologies and adjusting the processes and services accordingly. One solution offered was for management to conduct pilot testing of the new technology to uncover potential future barriers before its full implementation (Keyworth et al., 2018).

The selection of suitable technology and conducting sufficient analysis depends on the available resources. Lack of resources can limit the choice of technologies and the ability conduct human factor analysis. This brings us to the next subtheme, which concerns the managers' role in allocating and reconfiguring assets and resources (Teece, 2007). As technology selection and analysis, along with reconfiguring and allocating adequate resources, are parts of managerial responsibilities, these subthemes are presented together here. However, the nature and range of resources will be discussed as a standalone theme due to its significance and breadth. There is a certain overlap between the themes of leadership and management and resources, and a clear-cut distinction may undermine the fact that the themes and subthemes identified at each stage exist and occur simultaneously and take shape parallel to one another.

Another important subtheme of leadership is resource management and reconfiguration. An organization has various types of both internal and external resources at its disposal. These must be combined and reconfigured in order to reap the most benefit from the technology adoption process (Pace, 2016). “Reconfiguring and managing resources are indicators of the firm's ability to create a better ‘fit’ with its environment” (Pace, 2016, p. 411) and develop competitive capabilities through strengthening and adjusting resources (Teece, 2007). This is referred to as sensing and seizing, which reflects the manager knowing where to invest to create value from the innovation (Pace, 2016). Augier and Teece (2008, p. 1190) defined dynamic capabilities as the ability to “shape, reshape, configure, and reconfigure assets” to be profitable in the face of altering markets and technologies. Management must first identify all the available resources that could help with the technology adoption process. However, there is not enough discussion in the literature of how resources should be reconfigured during technology change as opposed to other changes.

Resources

The next main theme found in the literature is resources. Based on the analysis, we consider resources to include material resources (technical resources, infrastructure, budget) and immaterial resources (employees' knowledge and skills, organization's political resources and partnerships, time). It has been found that an organizational capability to be agile in responding to changes is influenced by tangible and intrinsic resources (such as accumulated experience), internal resources, and external facilitating resources (Ali et al., 2018). This is discussed further under the subthemes of external resources and internal resources.

The subtheme of external resources is about the resources outside the organization that can help in adopting a new technology. They are crucial in allowing an organization to take advantage of its external environment (Pace, 2016). External material resources may be in the form of sponsorships or funding bodies, or even being able to use others' premises to carry out certain tasks or to outsource some operations. External immaterial resources are mainly the network of knowledge sharing, which in the long term will reduce the external knowledge absorption costs (Antonelli and Scellato, 2013). This network can comprise professional network groups, consultants, or technical support team that can help with technology implementation and use.

The next subtheme under resources is internal resources. Internal material resources include the available technological infrastructure and budget. Resources in the form of budget can be allocated to enhance technology adoption through incentive systems that reward and motivate employees' effort to embrace new technologies (Vaishnavi et al., 2019). Having an adequate infrastructure is important in technology adoption because the extent and the quality of the infrastructure determines the attitude and behavior of the adopters (Langstrand, 2016). This implies that having the necessary conditions to introduce a new technology or to incorporate a new technology into an existing system makes it easier for users to accept it because there are fewer problems to be solved. The adopters are more ready and more likely to accept the technology when they know that the organization has the infrastructure for the new changes. The previous technology becomes the foundation upon which new technologies are built, and technological infrastructure accumulates over time (Gillani et al., 2020).

Internal immaterial resources mainly comprise the organization's human resources, meaning the employees, and their attitude and aptitude, prior to the adoption of new technological change. Attitude and aptitude can either slow down the process or speed it up based on how they are shaped and utilized. The employees can hasten and enhance the process if they are ready for technology changes. Zhang and Xiao (2017, p. 433) define citizen readiness as “a state of mind—a citizen's predisposition and likelihood to try new technology services”; the authors posit that technology cannot be absorbed if people are not ready. The same can be applied to employees in an organization.

Aptitude refers to the potential and capabilities that an organization possesses through its employees' tacit and explicit knowledge, their awareness, skill level, and expertise (Naor et al., 2015; Vrhovec et al., 2015; see Freeze and Schmidt, 2015). Attitude is a collection of many constituent elements shaping how employees view the organization. The most relevant elements shaping a person's attitude include personality traits, where openness to experience and extraversion have been argued to enhance change acceptance (Huang, 2015). Another element is perceived psychological safety, which is having a sense of security in the face of new developments. It is the result of the employees' perceived cost and benefit, perceived personal valence (Armenakis and Harris, 2009), perceived threat (Bala and Venkatesh, 2016), and perceived loss of control due to new changes. Perceived procedural and outcome fairness, trust in the management's intention behind the change (Nielsen and Mengiste, 2014), and having a sense of efficacy to cope with new changes (Sætren and Laumann, 2014) can influence attitude toward a change. Furthermore, subjective norms, or “the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188), influence the intention to adopt a new technology (Bayerl et al., 2013). Employees' commitment to the organization's norms motivates them to adopt the change (Vella et al., 2013).

When introducing a new technology, the level of aptitude of the employees must be considered to see if they have the necessary knowledge and skills to adopt the change. If they do, they will be more ready to accept the new technology; if not, organizations must consider interventions such as training that improves the aptitude of employees. It is more difficult to evaluate attitude of employees than to evaluate the aptitude of the employees. Organizations cannot change the personality traits of employees, but when introducing new technologies, they can divide and appoint tasks that better suit their personalities. For example, those with higher levels of openness and extraversion could be suitable change agents. Perceived psychological safety, fairness, and efficacy should be investigated prior to and during the technology change. This can be done through anonymous opinion surveys or forums, as well as in-person information sessions. Based on the results, interventions can be planned to address the concerns raised by employees.

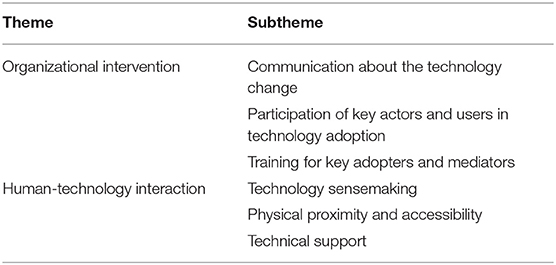

Change Process Stage

In this section, the change process stage and the themes found in the literature that were placed under this stage are presented. The main themes are organizational interventions and human-technology interaction. Interventions include communication, participation, and training in order to smoothen the ongoing change process and enhance the quality of technology adoption. At the same time, a human-technology interaction process is taking place. This is when people are engaged with the technology and are trying to make sense of it based on their attitude and aptitude, the technical features of the technology, and their perceived level of organizational support. These main themes and their subthemes are presented next. An overview is provided in Table 2.

Organizational Intervention

This theme is an important theme in the literature. It refers to the initiatives that organizations take to reinforce the change process. These measures help respond to the challenges of technology adoption and improve the process. Interventions are tailored to the specific context and time, and to the specific technology and its features. It is the presence or absence of these interventions and the extent of the quality and timeliness with which they are offered that make them enablers or barriers. These interventions are discussed under the subthemes of communication about the technological change, participation of key actors and users in technology adoption, and training for key adopters and mediators.

The subtheme of communication about the technological change represents an essential intervention. Organizations should be very strategic about how they convey information about technological changes. Their discourse must be aligned with the organizational culture, tailored to the audience, consistent, continuous, and honest. This will enhance employees' sense of trust and perceived fairness, and reduce feelings of anxiety about the technology change. Timing is essential. Communication should take place in the initial phases of the introduction of the technology, or even as early as the selection decision. Cross-communication early on is important “in order to set a common goal for harmonization, coherence and collaboration” (Kierkegaard, 2015, p. 152) between stakeholders. This leads to early role clarification for all the stakeholders, and helps to avoid confusion and uncertainty. The choice of communication channels and networks is also important. There are multiple official and unofficial networks within organizations. The different stakeholders may also communicate with their respective external partners. Managing communication through these channels and networks is essential in technology sensemaking across the organization's ecosystem. Communication will result in increased awareness, knowledge, and collective problem-solving. Another important aspect of communication is homogeneity across various receivers in terms of frequency and thoroughness, which is important in perceived fairness and trust.

The next subtheme is named participation of key actors and users in technology adoption. Communicating about a technology provides a platform for all the key actors to voice their opinions, to be acknowledged, and to contribute to the betterment of the process (Jensen and Kushniruk, 2014), and participation logically follows. Participation is about empowering end users and key actors, promoting their engagement and commitment (Rizzuto et al., 2014). In the long term, this will mean more problem solving at the beginning and a better, faster, and more cost-effective adoption process. There is also a higher likelihood of continuance of use and increased psychological safety (Antonioni, 1994 as cited in Johannsdottir et al., 2015).

The next subtheme is training for key adopters and mediators. Training is an important contributor to successful change implementation (Petit dit Dariel et al., 2013). This intervention is particularly effective in overcoming knowledge and skills gaps, and helps to enhance self-efficacy, reduce technostress (Molino et al., 2020), and improve technology adoption. By reducing the perceived complexity, it can enhance PEOU and technological efficacy, leading to more positive attitudes as it enhances sensemaking (Takian et al., 2014) and contributes to the success of technology adoption (Herbert and Connors, 2016).

To be effective, training should be carefully designed and tailored to the receivers. The choice of discourse and the phrasing of the objectives of the training are very important to create a realistic expectation of what the training can lead to. The trainers need to be carefully chosen as they are the first mentors in guiding employees in the use of the technology. It is important to deliver knowledge in such a way that people can utilize it to better accomplish their task objectives (Mühlburger et al., 2017). It is also mentioned in the literature that adequate adjustment time is needed to allow the users to familiarize themselves with the technology in the initial stages of change (Keyworth et al., 2018). Furthermore, the stages in training and the actors are important considerations. For example, it was mentioned in the literature that it is best to allow employees to familiarize themselves with the technology for less complicated and risky tasks and then move on to riskier contexts (Thomas and Yao, 2020). Training is a strategic investment that strengthens an organization's internal resources by targeting employees' aptitude and attitude toward current and future technological changes. Training should not only focus on technical skills, but also on soft skills as “they represent protective factors in changing situations” (Molino et al., 2020, p. 10), especially with regard to the new industrial and technological development era of Industry 4.0. Enhanced positive attitude, along with the necessary skills, leading to technology acceptance and use can, in turn, create a feeling of greater work engagement and motivation among employees, and so improve performance. The knowledge and skills acquired will become part of the stored knowledge and infrastructure of the firm. Training is considered to be “an important incentive for work, even more important than extrinsic rewards or compensation” (Shirish et al., 2016, p. 1120), and when it comes to incentives, “training and development is the most prized benefit” (Han and Su, 2011, p. 3). However, one issue mentioned in the literature is the importance of standardization of training in a sector in order to avoid training employees “in various ways, using different means, and achieving different levels of proficiency” (Kumar et al., 2018, p. 36).

Training is an important tool to influence organizational culture when it comes to resistance to change. Training should have a clear learning objective, and it should also clarify the mechanism by which it will enhance task performance and reduce the perception of risk and threat (Escobar-Rodríguez and Bartual-Sopena, 2015). The result will be smoother technology adoption and assimilation.

Human-Technology Interaction

Technology does not operate in a vacuum and it cannot be isolated from its social context. The use of technology is very much dependent on the user experience. Therefore, this theme is about how this user experience is formed through interaction with the technology, but also as a response to how the organization manages technology changes. Human-technology interaction will determine the fate of the technology and its further use. The most relevant underlying mechanism of this interaction is reflected in the subthemes presented in this section. These subthemes include technology sensemaking, physical proximity and accessibility, and technical support.

The subtheme of technology sensemaking encompasses the broad emotional and cognitive processes involved in the evaluation of the new technology adoption process. Employees evaluate how the technology has been put to use—volition vs. coercion in use and the perceived fairness during the process (Jiao and Zhao, 2014). The employees evaluate those who developed and introduced the technology and the management based on what the employees' attitude is toward the developers and managers. Employees also evaluate whether there was an urgent and legitimate need for this technology and whether the technology itself was a suitable choice. They evaluate the usability of the technology (is it easy and fast to learn or is it complex and time consuming?) and the attributes that make the technology more attractive to use. These attributes are summarized by Rogers (2003, p. 223) as “(1) relative advantage, (2) compatibility, (3) complexity, (4) trialability and (5) observability.”

The attribute of relative advantage presented by Rogers (2003) is about the superiority of the innovation or technology compared to the previous version. This attribute is closely linked to other concepts presented in the literature, such as PU and PEOU, which influence the intention to use the technology (for more detail, see Davis et al., 1989; Vella et al., 2013; Escobar-Rodríguez and Bartual-Sopena, 2015; Goldkind et al., 2016). PEOU is also related to technological efficacy, which is about having a sense of capability based on one's technical skills and the procedural knowledge that is needed, and being confident that new skills and knowledge can be acquired (for more details, see Hopp and Gangadharbatla, 2016; Martins et al., 2016). A lack of technological efficacy could lead to the experience of technostress and possibly job dissatisfaction and resistance to change (Freeze and Schmidt, 2015). PEOU may be influenced by how sophisticated the technology is (Ghorab, 1997): for example, if the technology presented is an early prototype, it will not yet be well-developed and will not be easy and smooth to use. This can lead to a lack of usability (Bourrie et al., 2015), leading to a negative evaluation of the technology.

The attributes of compatibility and complexity (Rogers, 2003) are also referred to as assimilative-disruptive and incremental-radical technology in the literature. Complexity is about the degree to which the novel features require learning in order to use the new technology. Compatibility is about being able to integrate the technology into current tasks without disturbing the current methods due to similar technical standards (Nagy et al., 2016). It has been found to be an important factor in technology adoption (Hanafizadeh et al., 2014). The more complex the technology, the more cognitive and emotional resources are needed to learn how to work with it and to cope with the challenges. Employees may evaluate whether it is worth it to meet the demands of the complex technologies. In doing so, they also evaluate the task-technology congruence. This is about whether the technology actually does what it is supposed to do and the extent to which it fits with the deliverables defined for the task with improved efficiency (Vest and Kash, 2016) and effectiveness (Singh, 2017). If it is worth it, employees will be willing to meet the demands of adopting new technology. Literature has shown that users evaluate if the technology helps them achieve their goal at the desired level of quality and without increasing the time needed to perform the task (Barrett, 2018).

The remaining attributes mentioned by Rogers (2003) include trialability, which is about being able to experiment with the technology, modify, and reinvent it as it evolves. The attribute of observability refers to being able to see the results of the use of technology and become motivated to use it.

Another subtheme that influences the human-technology interaction is physical proximity and accessibility, which is about easy access to the technology and proximity to developers and managers. Proximity is important because it enhances continuous communication and dialogue between key actors, leading to work process improvement that will, in turn, enhance technology acceptance and use. Lack of accessibility decreases PEOU (Vella et al., 2013), and unequal proximity creates organizational bias over time due to inconsistent communication, mutual irritations, and compromised technical support.

The availability of technical support facilitates adoption. It helps with managing technostress, promotes learning and knowledge sharing, and enhances psychological safety. It shows commitment on the part of the management, and the social support that will help overcome all kinds of challenge during the adoption process (Freeze and Schmidt, 2015; Wells et al., 2015; Avadikyan et al., 2016).

We believe that the change process stage is crucial in technology adoption and use. Interventions can shape the attitude and improve the capabilities of users regarding the technology and the organization. They can set the tone for constructive communication and participation, and, over time, create the cultural norms and values that enhance technology acceptance and innovation. This is the time either to make up for the organization's history of past technology implementation failures or to build on a history and culture of successful technology implementations. Past experiences of failure pose a risk to new changes and create uncertainties (Han et al., 2020), while past successes facilitate new technology changes (Kumar et al., 2018). We believe that by knowing the pre-change stage very well and carefully designing the interventions, organizations can influence the human-technology interaction and lead the change process toward a desired outcome. This is the time to compensate for the shortcomings of the past and to create a foundation for current and future technology adoptions.

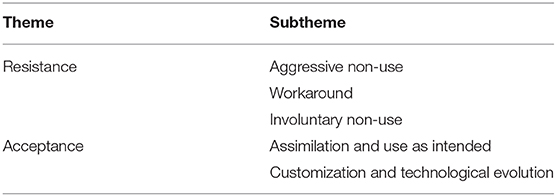

Post-change Stage and Outcome