95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 08 July 2021

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626547

Objective: The COVID-19 epidemic has generated great stress throughout healthcare workers (HCWs). The situation of HCWs should be fully and timely understood. The aim of this meta-analysis is to determine the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers.

Method: We searched the original literatures published from 1 Nov 2019 to 20 Sep 2020 in electronic databases of PUBMED, EMBASE and WEB OF SCIENCE. Forty-seven studies were included in the meta-analysis with a combined total of 81,277 participants.

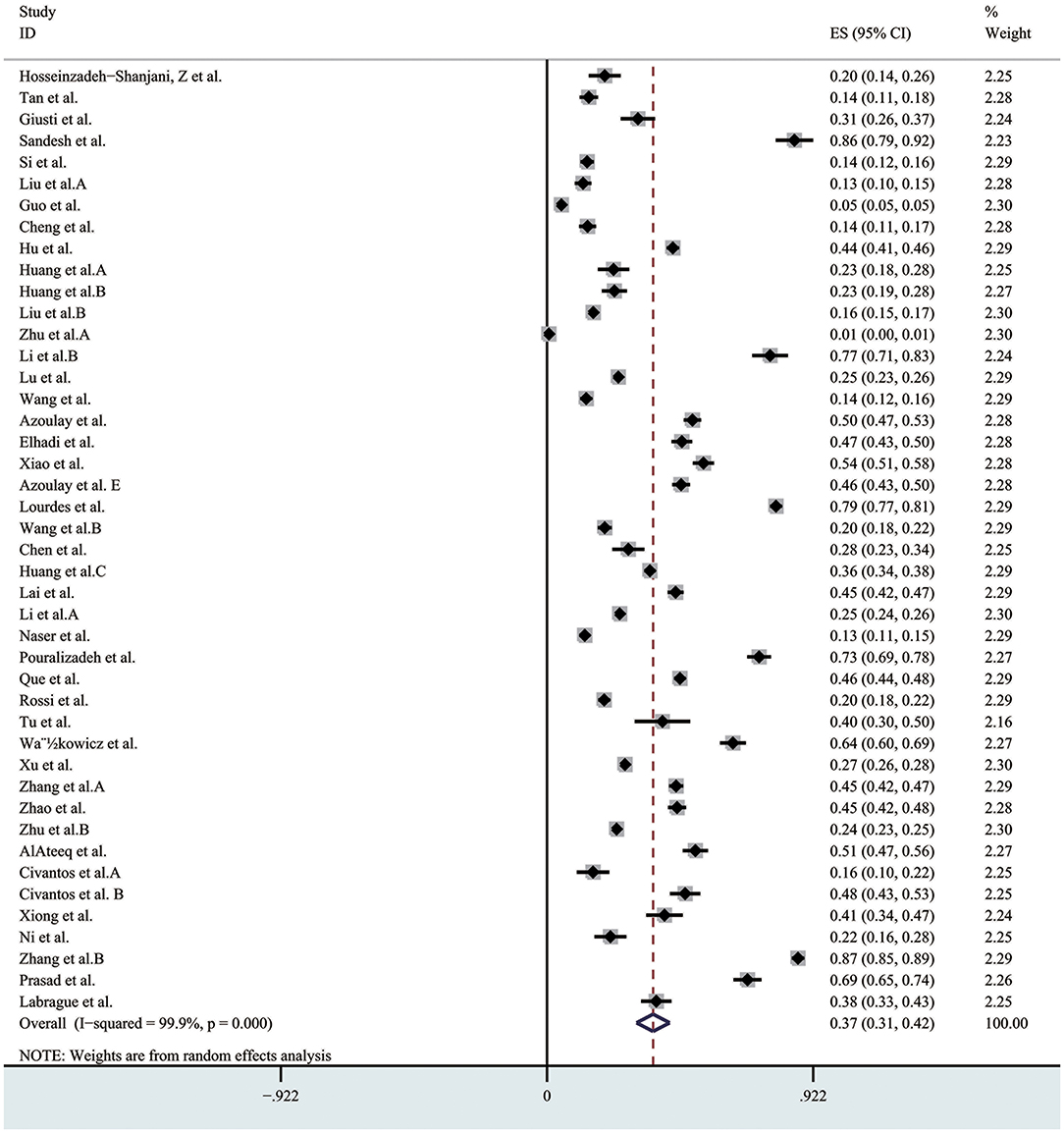

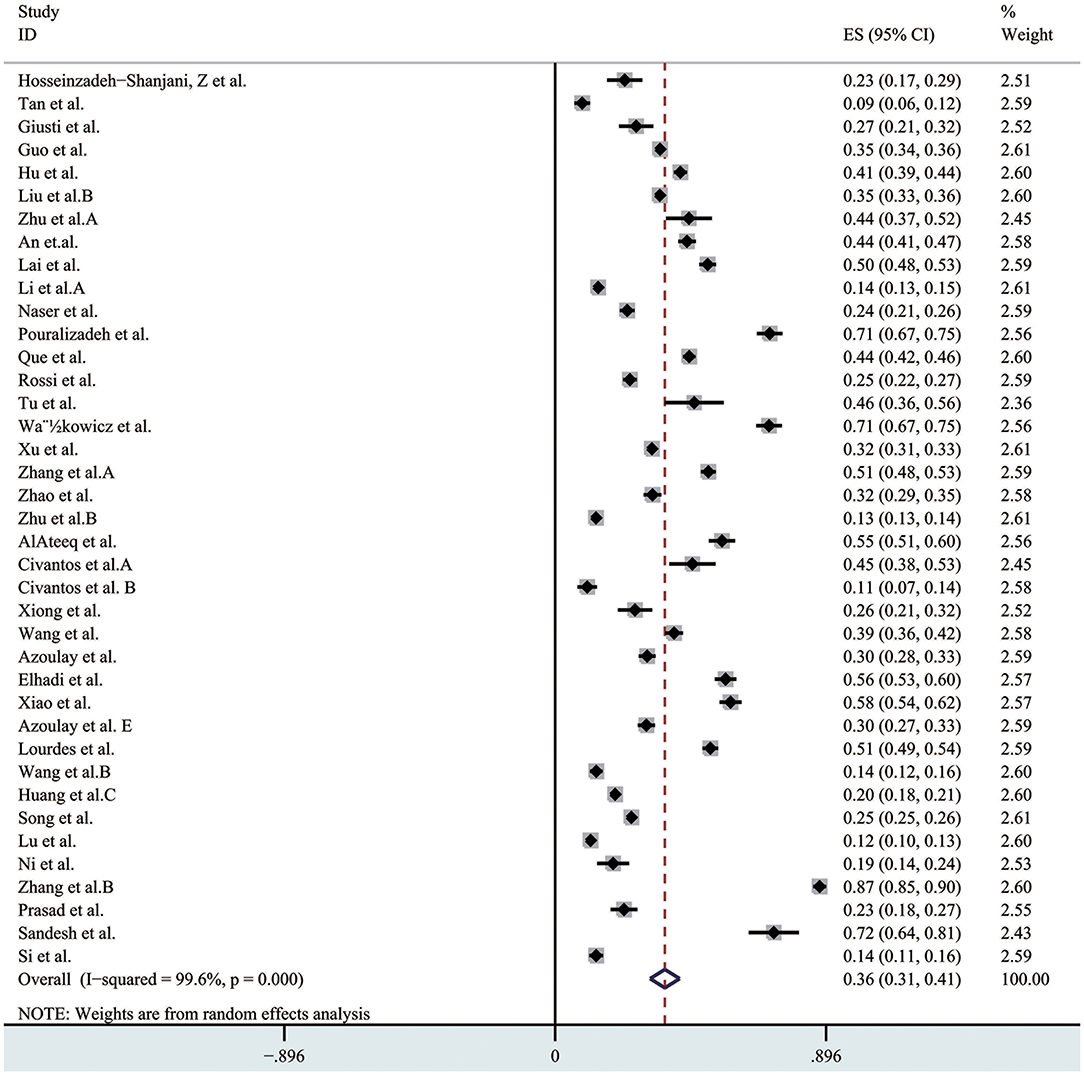

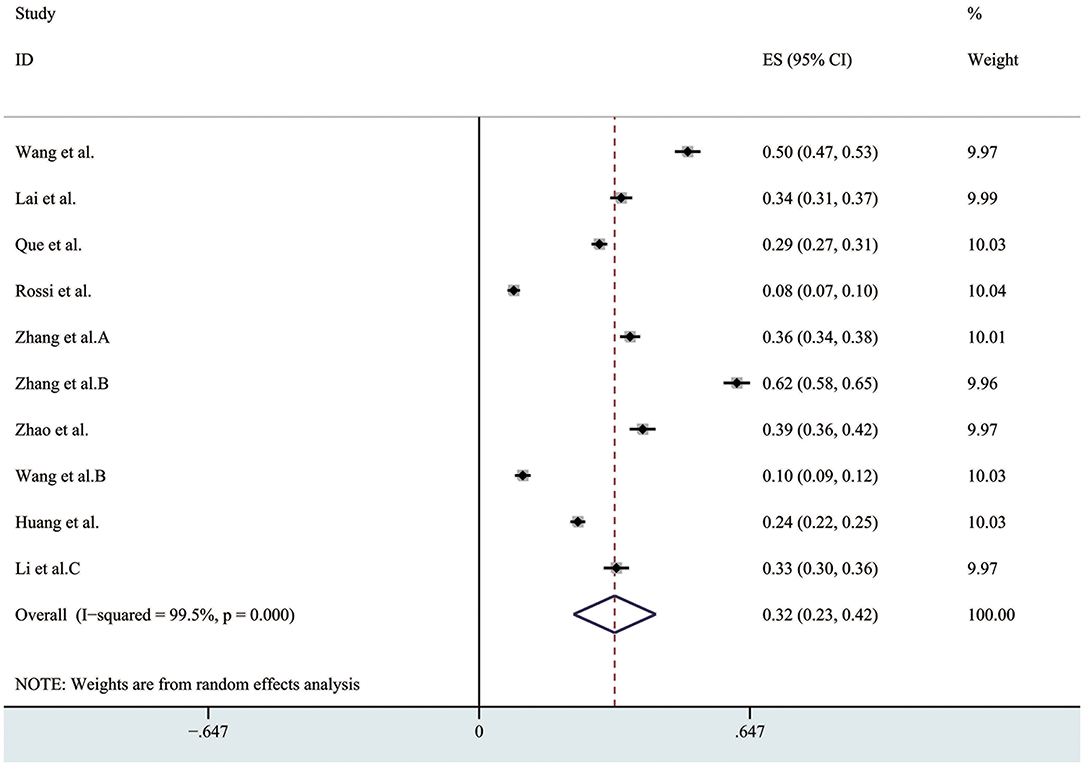

Results: The pooled prevalence of anxiety is 37% (95% CI 0.31–0.42, I2 = 99.9%) from 44 studies. Depression is estimated in 39 studies, and the pooled prevalence of depression is 36% (95% CI 0.31–0.41, I2 = 99.6%). There are 10 studies reported the prevalence of insomnia, and the overall prevalence of insomnia is 32% (95% CI 0.23–0.42, I2 = 99.5%). The subgroup analysis showed a higher incidence of anxiety and depression among women and the frontline HCWs compared to men and non-frontline HCWs respectively.

Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic has caused heavy psychological impact among healthcare professionals especially women and frontline workers. Timely psychological counseling and intervention ought to be implemented for HCWs in order to alleviate their anxiety and improve their general mental health.

Epidemic studies proved that previous infectious diseases caused long-term and persistent psychopathological consequences among this category. Similarly, in this extremely hard and bitter fight against COVID-19, health care workers (HCWs) played a significant role and may undergo severe psychological stress. Just like several studies reported, a multitude of HCWs appeared to suffer from several long-lasting psychological problems, including anxiety, depression, insomnia, etc. (Cheng et al., 2020). HCWs are exposed to longer work shifts in order to meet the growth of health care demand. Meanwhile, the lack of social support, poor sleep quality, isolation from families and friends, fear of spreading the disease to their families and coworker and direct contact with patients are several triggers for more psychological problems among HCWs. Moreover, during working hours, HCWs have to wear protective equipment making their movement and operation slowly and cause respiratory discomfort and difficulties which are also aggravating factors for psychological symptoms of HCWs (Cheng et al., 2020; Elhadi et al., 2020; Giusti et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020a).

A systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes COVID-19 during a pandemic the prevalence of depression and anxiety among the healthcare workers, which includes only the literatures published in Asia before April 2020 (Luo et al., 2020). Following the publication of this review, many studies have been published on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on health professionals in many other countries and have compared the psychological impact of COVID-19 on frontline and non-frontline HCWs. As the epidemic continues to spread and cases increase at this stage, we consider that a meta-analysis of published studies is necessary to explore whether COVID-19 has further psychological effects on medical staffs. In order to implement appropriate strategies to prevent or intervene in the adverse psychological effects on HCWs and provide help to relieve the burden, we conducted the current systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the latest psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among healthcare workers In this meta-analysis, we assessed the psychological impact of COVID-19 on the HCWs and summarized the different prevalence rates of anxiety and depression between frontline HCWs and non-frontline HCWs.

In order to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis on studies evaluating the prevalence of the psychological and mental impact of COVID-19, we did this study according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al., 2009). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Eighth People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. We searched the original literatures published from 1 Nov 2019 to 20 Sep 2020 in electronic databases of PUBMED, EMBASE and WEB OF SCIENCE. Our search terms were (“COVID-19”/exp OR COVID-19 OR “coronavirus”/exp OR coronavirus) AND (“psychological”/exp OR psychological OR “mental”/exp OR mental OR “stress”/exp OR stress OR “anxiety” OR anxiety OR “depression” OR depression OR “post-traumatic” OR “post-traumatic”/exp OR “trauma” OR 'trauma'/exp) AND (“doctor” OR “maternity staff” OR “medical staff” OR “medical workers” OR “Healthcare workers” OR “Healthcare staff” OR “Healthcare professional” OR “Nursing professional” OR “nursing staff” OR “nurses”) for EMBASE; [(“COVID-19”[All Fields] OR “coronavirus”[All Fields]) AND (“Stress, Psychological”[Mesh] OR “mental” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “stress” OR “post-traumatic” OR “trauma”)] AND [[[[[[[[[(doctor) OR (maternity staff)] OR (medical staff)] OR (medical workers)] OR (Healthcare workers)] OR (Healthcare staff)] OR (Healthcare professional)] OR (Nursing professional)] OR (nursing staff)] OR (nurses)] for PUBMED; #1 TS=(COVID-19 OR coronavirus), #2 TS = (Psychological OR mental OR anxiety OR depression OR stress OR post-traumatic OR trauma), #3 TS=(doctor OR surgeons OR surgical staff OR maternity staff OR medical staff OR medical workers OR healthcare workers OR healthcare staff OR healthcare professional OR nursing professional OR nursing staff OR nurses), #4 #1 AND #2 AND #3 for WEB OF SCIENCE.

We selected the literatures we need according to our PICOS (population; intervention; compare; outcomes; study) criteria. The included criteria of our study were as follows: (1) P/I: The subjects in these literatures should be healthcare staffs (i.e., medical doctors, nurses, nursing assistant, clinical assistant departments' staffs, public health professionals) fighting against the COVID-19; (2) O: Only when those studies evaluating the prevalence rates of anxiety, depression and/or insomnia using validated assessment methods were eligible for inclusion; (3) S: Cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, randomized controlled trials were acceptable; (4) The language of the included studies is English or Chinese.

Two researchers searched the literatures independently, and we conducted three rounds of screening of the studies we have searched. Firstly, the titles of the articles were screened and then the selected studies are further screened by reading abstracts of the literature. Finally, the full text of the articles after the second round of screening were read in order to decide which studies would be included. If two researchers had discrepancies on whether to include a certain study, the senior author (LY) was consulted to make the final decision.

The information from each literature were extracted by two researchers independently including: author, year, the number of the participation, response rate, region, the percentage of physician, nurse and other healthcare workers in those studies, the percentage of men and women in included articles, survey methods used and the cut-offs mentioned in each study as well as the total number and percentage of participants that screened positive for depression, anxiety or insomnia. As far as the quality assessment method, we referred to a resent systemic review and meta-analysis (Pappa et al., 2020) using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale to evaluate the quality of included cross-sectional studies. The appraisal tool assessed the representativeness of sample and the sample size, the validate assessment tool with appropriate cut-offs, the response rate and adequacy of descriptive statistics. The total score ranged between 0 and 5. Studies scoring ≥3 points were regarded as low risk of bias, compared to the studies assessed with <3 points that were regarded as high risk of bias.

The metan and metaprop module in STATA was used to calculate the pooled prevalence and 95% confidence interval of anxiety, depression and insomnia with random effects models (Luo et al., 2020). Substantial heterogeneity was defined as I2 > 75%. We also perform a subgroup analysis according to the following categories: the severity of anxiety and depression, gender, frontline and non-frontline healthcare workers. In articles that focus on the severity of anxiety and depression, the following questionnaires and grading criteria are used. Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) questionnaire:mild (score of 5–9), moderate (score 10–14), or severe (score 15–21) (Spitzer et al., 2006); the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9):mild (score of 5–9), moderate (score 10–14), moderately severe (score 15–19), or severe (score 20–27) (Löwe et al., 2004); Selfrating Anxiety Scale (SAS): a score of 50–59 indicated mild anxiety, 60–69 indicated moderate anxiety, and ≥70 indicated severe anxiety; Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS): 50–59 for mild depression, 60–69 for moderate depression, and 70 or more for severe depression (Zung, 1971); The Hamilton rating scale for anxiety (HAMA): no anxiety (score 0–6), mild and moderate anxiety (score 7–13), severe anxiety (score ≥ 14); The Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAMD): mild and moderate (score 7–23), severe depression (score ≥ 24) (Lu et al., 2020). Frontline HCWs are defined as those who currently caring for COVID-19 patients in the participating hospitals and working in places with the highest probability of contact with COVID-19, for example, intensive care units, infectious diseases units, and emergency departments (Hu et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Wańkowicz et al., 2020). The non-frontline HCWs are those not working with COVID-19 patients (Lai et al., 2020). Sensitivity analysis was done by subtracting each study and calculating the pooled prevalence of the remaining studies, in order to identify studies which may severely affect the pooled prevalence. Our main outcomes were prevalence (p), confidence intervals (CI) and percentage prevalence (p × 100%).

A PRISMA diagram detailing the study retrieval process is shown in Figure 1.

The total number of the references we had searched from three databases was 3,168 (Embase: n = 659; PubMed: n = 1,215; Web of science: n = 1,294). Among these articles, 1,118 studies were removed because of duplication. After screening the title and abstract, 1,962 studies were excluded due to failure to meet the inclusion criteria (949: non-medical workers; 970: not about the psychological effects of COVID-19; 43: case report). Eighty-eight studies were screened for the full text. Among the above studies, 35 were deleted because of not reporting the prevalence, four were excluded because no mention was made of the type of questionnaire, and two were deleted because not in English or Chinese. Finally, 47 studies are included in this meta-analysis. All of these studies are cross-sectional studies and they are all conducted through online questionnaires (“questionnaire star,” Wechat or text message/email, etc.). A trigraph has been made to show the characteristics of these studies in Table 1. The results of the quality assessment for each study using Newcastle-Ottawa score are presented in Table 2, and the total pooled prevalence of anxiety, depression and/or insomnia as well as the subgroup analysis results are showed in the figures below.

A total of 44 studies reported the prevalence of anxiety, and the pooled prevalence of the anxiety was 37% (95% CI 0.31–0.42, I2 = 99.9%) as shown in Figure 2. In the sensitivity analysis, no study affected the pooled prevalence by over 3% when excluded. As far as the assessment tool, studies using different validated scales included: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS); Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS); Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); The 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7); Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and The COVID-19 Anxiety scale.

Figure 2. The pooled prevalence of anxiety. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight, weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

Depression were estimated in 39 studies, and the pooled prevalence of the depression was 36% (95% CI 0.31–0.41, I2 = 99.6%), as presented in Figure 3. In the sensitivity analysis, no study affected the pooled prevalence by over 1% when excluded. Different validated scales used to measure depression included: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS); Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS); the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2).

Figure 3. The pooled prevalence of depression. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight, weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

There were 10 studies which reported the prevalence of insomnia, and the overall prevalence of the insomnia was 32% (95% CI 0.23–0.42, I2 = 99.5%) as presented in Figure 4. In the sensitivity analysis, no study affected the pooled prevalence by over 3% when excluded. The evaluation tool using in these studies included: the seven-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI); PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) scale and Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS).

Figure 4. The pooled prevalence of insomnia. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight, weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

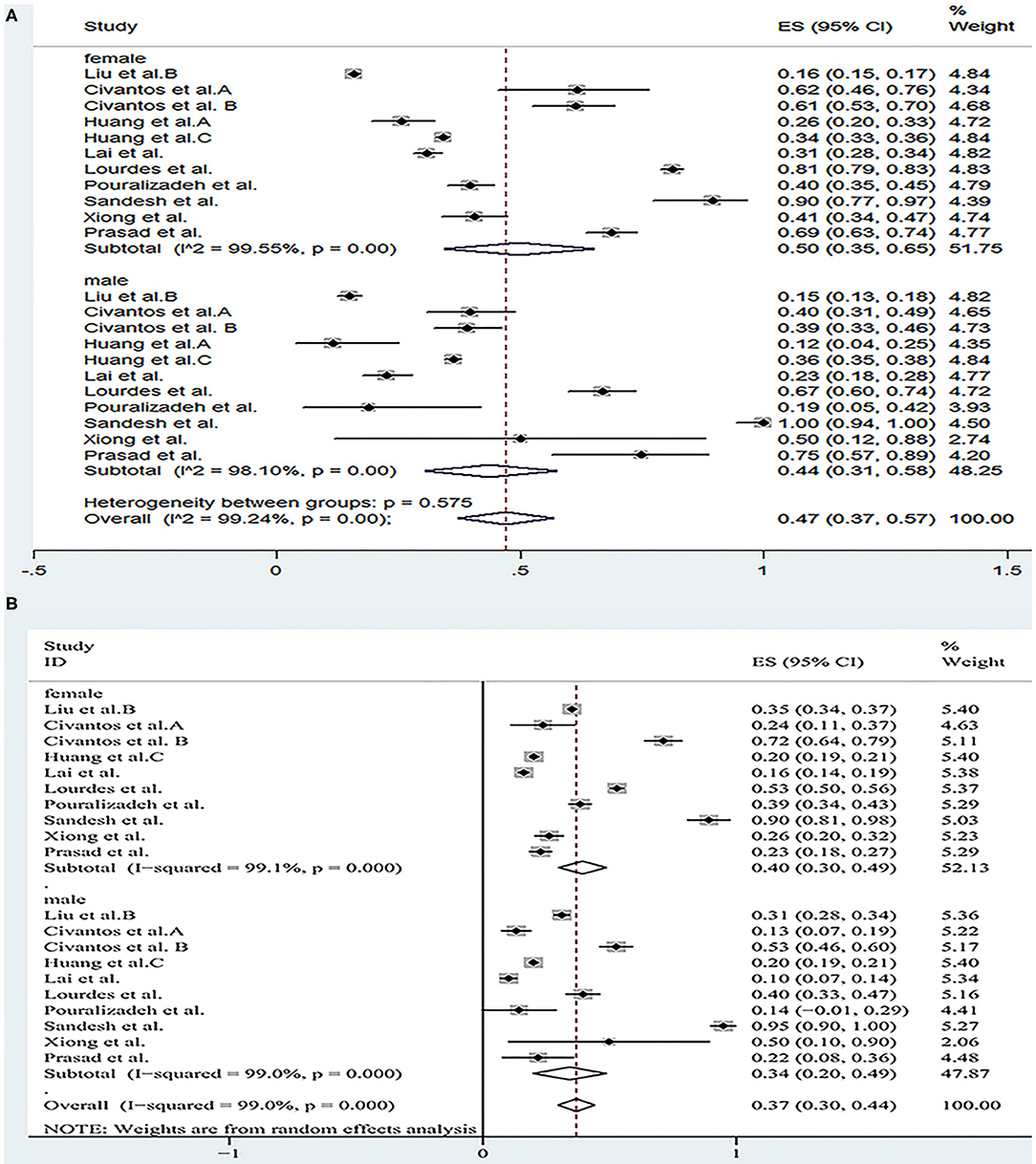

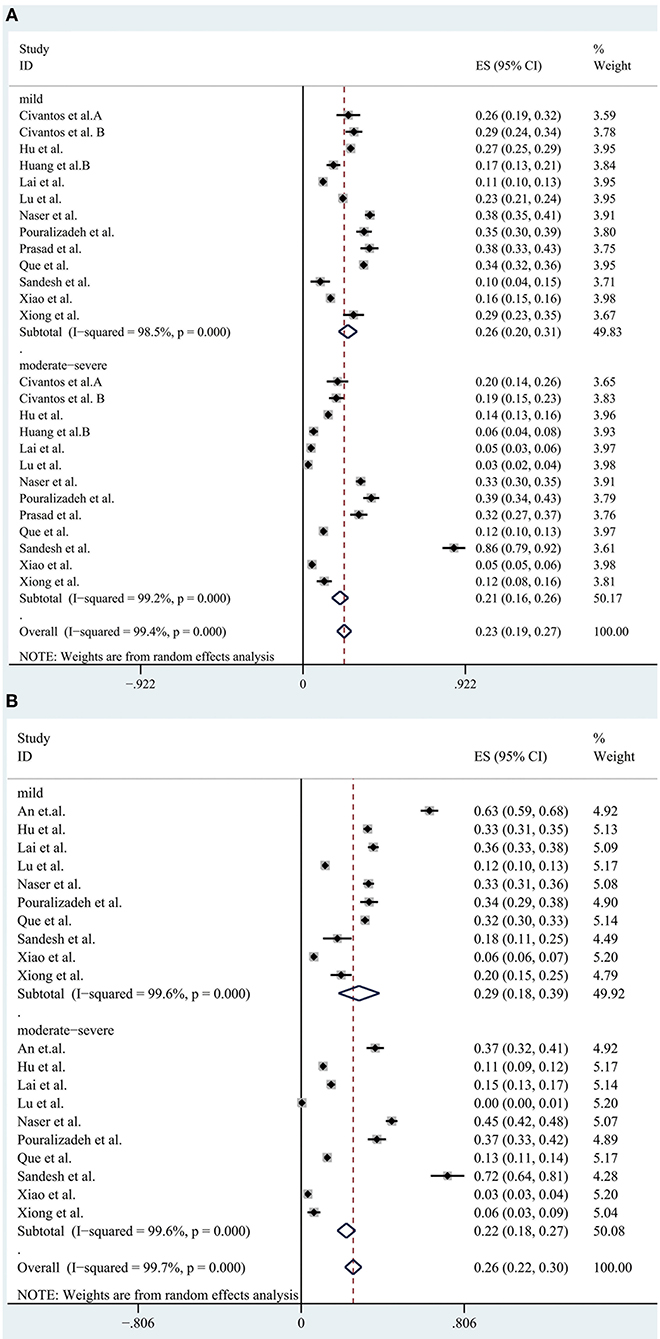

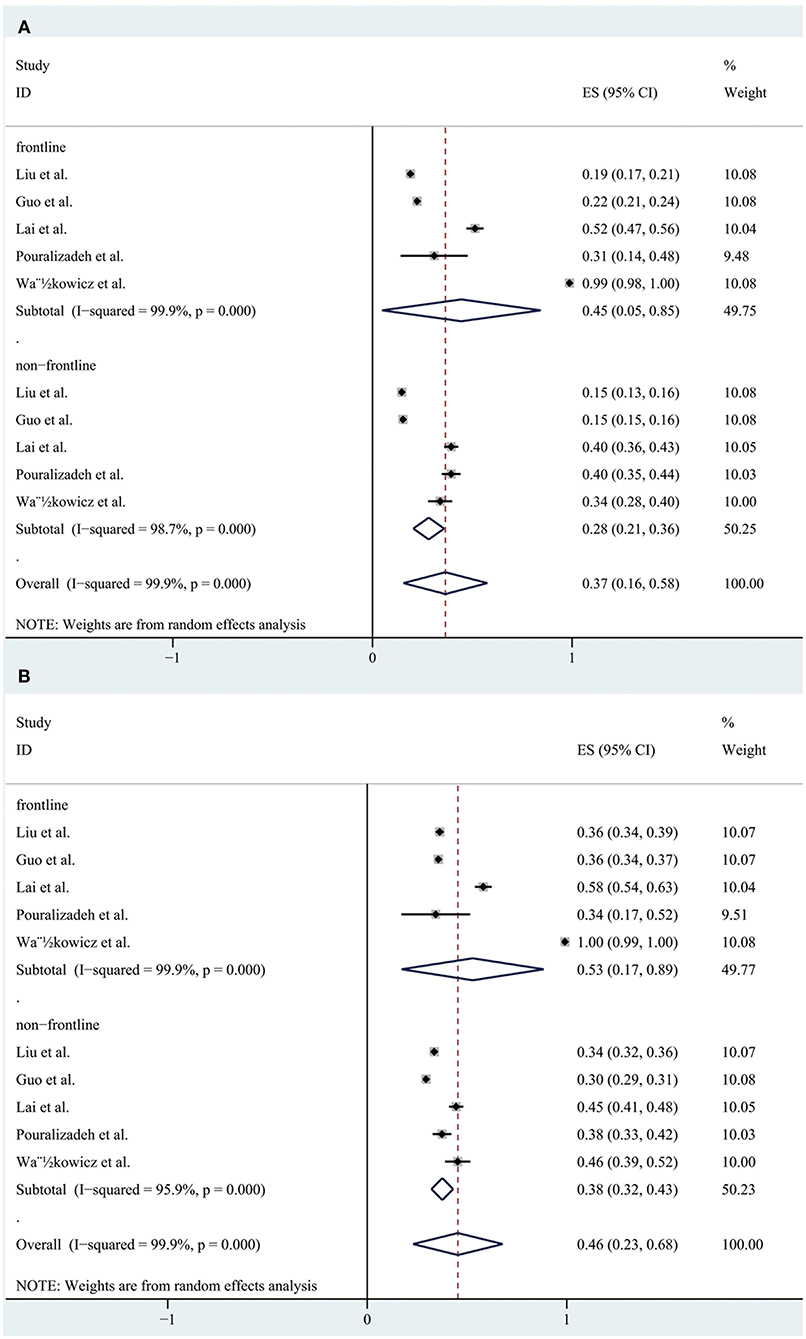

We conducted a subgroup analysis of the morbidity of the anxiety and depression by gender, severity, risk and profession. The results are shown in Figures 5–8, respectively.

Figure 5. The forest map based on the prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers of different genders. (A): A forest map based on the incidence of anxiety among health care workers of different genders; (B): A forest map based on the incidence of depression among health care workers of different genders. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight: weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

Figure 6. A forest map based on the incidence of various levels of anxiety and depression among medical personnel. (A): A forest map based on the incidence of various levels of anxiety among medical personnel; (B): A forest map based on the incidence of various levels of depression among medical personnel. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight: weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

Figure 7. A forest map based on the prevalence of anxiety and depression between front-line and non-frontline medical staffs. (A): A forest map based on the incidence of anxiety between front-line and non-frontline medical personnel; (B): A forest map based on the incidence of depression between front-line and non-frontline healthcare workers. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight: weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

Figure 8. A forest map based on the prevalence of anxiety and depression between doctors and nurses. (A): A forest map based on the incidence of anxiety between doctors and nurses; (B): A forest map based on the incidence of depression between doctors and nurses. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; Weight, weight of each included study (degree of impact on pooled results), The larger the weight is, the greater the influence on the combination result is.

A total of 11 studies reported the prevalence of anxiety by gender and the pooled prevalence was 50, 36% for female and male, respectively. The severity of the anxiety was divided into two groups including “mild” group and “moderate-severe” group and data could be obtained in 13 articles. The overall prevalence of anxiety for “mild” group was 26 and 21% for “moderate-severe” group. In the frontline and non-frontline groups, data on prevalence of anxiety were available in 5 literatures, with respective values of 45 and 28%. In addition, nine literatures (Al Sulais et al., 2020; Azoulay et al., 2020a; Guo et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020a; Lai et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Que et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020b) reported the prevalence of anxiety of doctors and nurses. The overall prevalence of anxiety for “doctor” group was 28%, and 34% for “nurse” group. For depression, data could be extracted from 10 articles according to gender, with a pooled prevalence of 40% for female and 34% for male. As far as the severity of depression, there were also 10 studies reported the morbidity of depression, with values of 29% for “mild” group and 22% for “moderate-severe” group respectively. Regarding to the “frontline” group and “non-frontline” group, the prevalence of depression was 53% in the former and 38% in the later which were calculated from the same five articles as anxiety. The prevalence of depression could be detected in eight literatures, with a pooled prevalence of 33% for doctors and 38% for nurses. As far as insomnia, a subgroup analysis was not performed due to the limited available data.

Results of a systemic review and meta-analysis of 47 studies indicated that a large proportion of healthcare workers suffered from the adverse psychological impact of COVID-19. Symptoms such as anxiety, depression and insomnia were analyzed as indicators of psychological effects of healthcare staffs during the COVID-19 epidemic, with respective values of 37% (31–42%), 36% (31–41%), and 32% (23–42%). The results of subgroup analysis showed that the incidence of anxiety and depression was significantly increased in females. After statistical analysis and calculation of the included data, the proportion of the “mild” group was higher than that of the “moderate-severe” group. The prevalence of anxiety and depression of frontline HCWs was much higher than non-frontline HCWs. Furthermore, nurses had higher rates of anxiety and depression than doctors.

Since COVID-19 is novel and has never been explored, and its horrible infectivity and mortality generate great stress throughout healthcare staffs especially on the frontline healthcare professionals, which become a major factor causing anxiety depression and insomnia among HCWs (Salari et al., 2020). In addition, there are also other factors, for example, insufficient medical protective equipment, contact ban with relatives, transfer to another ward, work overload and so on (Sandesh et al., 2020; Shigemura et al., 2020; Wańkowicz et al., 2020) that would lead to mental health problems for medical staff. In view of the above, several practical steps should be implemented by government officers and hospital administrators in order to prevent the occurrence of mental illness and relieve the mental and physical stress of the healthcare staffs, for example, adequate supplies of protective equipment (Koh et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006; Kim and Choi, 2016), appropriate work shift with regular sleep (Ho et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2018), clear communication (Bai et al., 2004; Goulia et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2018), and video contact with their families and friends (Azoulay et al., 2020a; Kisely et al., 2020). Furthermore, it's extremely necessary to provide timely and professionally tailored mental health support through media or multidisciplinary teams (Pappa et al., 2020). Whether the medical protective equipment provided by the government and society is sufficient, whether the social support is enhanced, etc., all of these factors, to a certain extent, can enhance the mental strength of medical staff and reduce the incidence of mental illness. We believe it is necessary to conduct this meta-analysis based on the research published so far to address the psychological condition of the HCWs.

Compared with the recent meta-analysis concerning the psychological impacts of COVID-19 among healthcare professionals which included 13 articles and reported the prevalence of anxiety, depression and insomnia were 23.2, 22.8, and 34.2% respectively, our study found a similar prevalence of insomnia among healthcare staffs but the prevalence of anxiety 37% and depression 36% were much higher than the prior study. We consider that as the epidemic worsens and the number of cases increase rapidly all over the world, the mental and physical stress faced by medical staff in each country is also increasing.

According to the result of the subgroup analysis, the incidence of anxiety and depression among female medical staffs was higher than that of male. The results of epidemiological studies showed that women were at a higher risk of depression (Lim et al., 2018). There are many reasons for this gap between men and women. For example, genetic factors might play a part, but empirical evidence for their potential to explain the gender gap in depression is still scarce (Albert, 2015; Kuehner, 2017). In addition, a ruminative response style, that is, the tendency to passively and repetitively analysis one's distress, problems, and concerns, without taking actions, has been proposed to account for a substantial part of the gender gap in depression. Two meta-analyses identified higher rumination tendencies in women than in men (Kuehner, 2017). However, of the studies included in our subgroup analysis, most had a higher percentage of female responders than male, and only four (Civantos et al., 2020a,b; Lai et al., 2020; Sandesh et al., 2020) (25.8, 39.3, 23.3, 42.9%, respectively) had a lower percentage of women than men. This selection bias may exist. According to the statistical results of the literature, we included that the prevalence rate of anxiety and depression appeared to be higher in “mild” group, while moderate and severe symptoms were less common among the participants. In our opinion, this result suggests that we ought to detect and intervene the mental health status of medical staffs timely and efficiently in order to prevent the occurrence of adverse mental illness, thus effectively reducing the incidence of anxiety and depression. Furthermore, we also find that a great proportion of the frontline healthcare workers suffered from anxiety and depression, since frontline healthcare professionals treating patients with COVID-19 are likely to be exposed to the highest risk to be infected because of their close, frequent contact with patients and longer hours than usual. In addition, these people are exposed to emotionally challenging interactions with the sick and critically ill patients and they tend to pay more attention to their own and their families' health. Moreover, they are subject to occupational overload due to staff shortages and insufficient personal protective equipment (Rossi et al., 2020; Wańkowicz et al., 2020). This highlighted the significance to take more effective and precautionary measures to protect frontline healthcare workers from the psychological damage at the governmental level and the personnel level (Luo et al., 2020). The higher overall prevalence of anxiety and depression is observed in nurses. There are several reasons to consider this. Firstly, nurses are relatively young and mostly female which may be an important reason. In addition, nurses are responsible for the collection of sputum for virus detection, which is the most dangerous work (Guo et al., 2020), and they need to act as “gatekeepers” responsible for educating and monitoring the practices of staff and visitors and also had an increased workload as they took on duties of other staff (Mitchell et al., 2002). All of these may contribute to the higher incidence of anxiety among nurses than doctors.

Overall, the findings of the current study may have some clinical implications. First, the COVID-19 pandemic situation has been effectively controlled in some countries, but the situation in other countries is still not optimistic. We must take adequate measures to prevent possible the next outbreak of the epidemic. We clearly confirm that HCWs who under high physical and mental health burden are still at a higher risk of suffering from psychological disease. It is urgently to provide psychological assistance to medical personnel who could help the governments better prepare for future outbreaks of unexpected infectious diseases. Second, our study showed that frontline HCWs presented higher prevalence of anxiety and depression. In fact, they did not want their families and friends worry about them and were afraid of bringing the virus to their home. In addition, patients' not cooperation with medical measures, unable to deal with patients' anxiety, panic, and other emotional problems, shortage of protective equipment were the main factors resulting psychological stress (Chen Q. et al., 2020). Therefore, it is not only necessary to ensure adequate equipment supply and timely psychological support for medical staffs, but also important to provide psychological support for patients, as it indirectly affects the mental and psychological state of frontline HCWs. Also, to a certain extent, the workload and difficulty of frontline medical work will be reduced. We held the opinion that a special research can be conducted to study which factors (little is known about the new virus/disease, limited resource, long work hours, contact ban with relatives, work overload, etc.) have a serious psychological impact on medical staff in the new epidemic, and what measures can be taken to effectively reduce the psychological pressure on medical staff in the future study. Third, the second wave of the outbreak in many countries has been kicked off, due to the outbreak of the first wave made a great influence on the spirit of the medical personnel psychology, therefore, we think it is necessary for medical workers, especially women and healthcare workers who have fought on the front line to carry out a psychological evaluation and to give professional guidance in time, in order to prevent the second pandemic from having a more severe impact on them.

There are several strengths and limitations to our review. Compared to the last systematic review and meta-analysis that comprised 13 studies from Asian countries (n = 33,062), the current meta-analysis included more studies (47 studies from 12 countries) with a much bigger sample size (n = 81,277). Psychological conditions of frontline and non-frontline HCWs were further investigated, which has some guiding implications for medical personnel to provide psychological assistance when facing different risks. The inherent heterogeneity across studies is also one of the main considerations for the limitations on research. While all of these studies reported prevalence of anxiety, depression or insomnia, several of them used the same test, but screened the population using different assessment scales and set different thresholds which may have an effect on the outcome. In addition, only three symptoms were meta-analyzed in this article due to the lack of relevant studies on other psychological symptoms of healthcare workers. Therefore, related studies can be conducted on other psychological effects of the COVID-19 on medical staff in the future. Moreover, most of the included studies are from China, data from other countries are still a few. At the present stage, the severity of the epidemic varies from country to country; the impact on the mental health of medical workers also varies greatly. In addition to the study in China, 16 of the included studies were conducted in 13 different countries. It is not reliable to describe the psychological status of medical staff in each country according to the limited literature collected so far. Therefore, if more literatures are collected in the future, further analysis can be made in this aspect. All quantitative studies were cross-sectional surveys with a short follow-up duration. Psychological status of medical personnel will change as the epidemic progresses, so it is not possible to extrapolate from these studies only the long-term mental health effects and how the basic rates of these mental health symptoms relate to other periods. Some literatures reported age (MD ± SD) or age range of the study group, but some did not report (age not applicable, Table 1), so we could not analyze age as a factor. Although most of the study subjects were between the ages of 25 and 45 (young adults), we still can't rule out the possibility that age may affect the results. It is also a limitation of our study.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created an emergency state and caused heavy psychological impact among HCWs. The prevalence of anxiety and depression are significantly higher in female HCWs than males, also in the frontline HCWs than non-frontline HCWs. In addition to quickly establish programs that provide knowledge on the virus, timely psychological counseling and intervention ought to be implemented for HCWs in order to alleviate their anxiety and improve their general mental health.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

LY: funding acquisition, conceptualization, and methodology. LC: supervision, review, and editing. MW, TS, YW, and JL: investigation and data curation. PS: data curation, original draft preparation, writing, and editing. All authors contributed, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1004800).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Al Sulais, E., Mosli, M., and AlAmeel, T. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 26, 249–255. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_174_20

AlAteeq, D. A., Aljhani, S., Althiyabi, I., and Majzoub, S. (2020). Mental health among healthcare providers during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health. 13, 1432–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.013

Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 40, 219–221. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150205

An, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, A., Li, Y., Zhang, Q., Cheung, T., et al. (2020). Prevalence of depression and its impact on quality of life among frontline nurses in emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect Disord. 276, 312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.047

Azoulay, E., Cariou, A., Bruneel, F., Demoule, A., Kouatchet, A., Reuter, D., et al. (2020a). Symptoms of anxiety, depression and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing COVID-19 patients: a cross-sectional study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 1388–1398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC

Azoulay, E., De Waele, J., Ferrer, R., Staudinger, T., Borkowska, M., Povoa, P., et al. (2020b). Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. Intensive Care 10:110. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00722-3

Bai, Y., Lin, C. C., Lin, C. Y., Chen, J. Y., Chue, C. M., and Chou, P. (2004). Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr. Serv. 55, 1055–1057. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055

Chen, Q., Liang, M., Li, Y., Guo, J., Fei, D., Wang, L., et al. (2020). Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 7, e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X

Chen, R., Chou, K. R., Huang, Y. J., Wang, T. S., Liu, S. Y., and Ho, L. Y. (2006). Effects of a SARS prevention programme in Taiwan on nursing staff's anxiety, depression and sleep quality: a longitudinal survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 43, 215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.006

Chen, X., Zhang, S. X., Jahanshahi, A. A., Alvarez-Risco, A., Dai, H., Li, J., et al. (2020). Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6:e20737. doi: 10.2196/20737

Cheng, F. F., Zhan, S. H., Xie, A. W., Cai, S. Z., Hui, L., Kong, X. X., et al. (2020). Anxiety in Chinese pediatric medical staff during the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019: a cross-sectional study. Transl. Pediatr. 9, 231–236. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.04.02

Civantos, A. M., Bertelli, A., Goncalves, A., Getzen, E., Chang, C., Long, Q., et al. (2020a). Mental health among head and neck surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national study. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 41, 102694–102694. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102694

Civantos, A. M., Byrnes, Y., Chang, C., Prasad, A., Chorath, K., Poonia, S. K., et al. (2020b). Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: national study. Head Neck-J. Sci. Spec. Head Neck 42, 1597–1609. doi: 10.1002/hed.26292

Elhadi, M., Msherghi, A., Elgzairi, M., Alhashimi, A., Bouhuwaish, A., Biala, M., et al. (2020). Psychological status of healthcare workers during the civil war and COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 137:110221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110221

Giusti, E. M., Pedroli, E., D'Aniello, G. E., Stramba Badiale, C., Pietrabissa, G., Manna, C., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684

Goulia, P., Mantas, C., Dimitroula, D., Mantis, D., and Hyphantis, T. (2010). General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:322. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-322

Guo, J., Lianming Liao, P., Baoguo Wang, M. D., and Xiaoqiang Li, M. D. (2020). Psychological effects of COVID-19 on hospital staff a national cross-sectional survey. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3550050

Ho, S. M., Kwong-Lo, R. S., Mak, C. W., and Wong, J. S. (2005). Fear of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) among health care workers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 344–349. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.344

Hosseinzadeh-Shanjani, Z., Hajimiri, K., Rostami, B., Ramazani, S., and Dadashi, M. (2020). Stress, anxiety, and depression levels among healthcare staff during the COVID-19 epidemic. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 11, 163–170. doi: 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.651.4

Hu, D., Kong, Y., Li, W., Han, Q., Zhang, X., Zhu, L. X., et al. (2020). Frontline nurses' burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: a large-scale cross-sectional study. EClin. Med. 24:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424

Huang, J. Z., Han, M. F., Luo, T. D., Ren, A. K., and Zhou, X. P. (2020a). [Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 38, 192–195. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121094-20200219-00063

Huang, L., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Ye, P., Chen, X., Xu, H., et al. (2020b). Factors influencing anxiety of health care workers in the radiology department with high exposure risk to COVID-19. Med. Sci. Monit. 26:e926008. doi: 10.12659/MSM.926008

Huang, Y., and Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

Kang, H. S., Son, Y. D., Chae, S. M., and Corte, C. (2018). Working experiences of nurses during the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 24:e12664. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12664

Kim, J. S., and Choi, J. S. (2016). Factors influencing emergency nurses' burnout during an outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Korea. Asian Nurs. Res. 10, 295–299. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.10.002

Kisely, S., Warren, N., McMahon, L., Dalais, C., Henry, I., and Siskind, D. (2020). Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 369:m1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1642

Koh, D., Lim, M. K., Chia, S. E., Ko, S. M., Qian, F., Ng, V., et al. (2005). Risk perception and impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: what can we learn? Med. Care 43, 676–682. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc

Kuehner, C. (2017). Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry 4, 146–158. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2

Labrague, L. J., and De Los Santos, J. A. A. (2020). COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121

Lai, J., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Hu, J., Wei, N., et al. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

Lee, S. H., Juang, Y. Y., Su, Y. J., Lee, H. L., Lin, Y. H., and Chao, C. C. (2005). Facing SARS: psychological impacts on SARS team nurses and psychiatric services in a Taiwan general hospital. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 27, 352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.04.007

Li, G., Miao, J., Wang, H., Xu, S., Sun, W., Fan, Y., et al. (2020a). Psychological impact on women health workers involved in COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan: a cross-sectional study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 91, 895–897. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323134

Li, R., Chen, Y., Lv, J., Liu, L., Zong, S., Li, H., et al. (2020b). Anxiety and related factors in frontline clinical nurses fighting COVID-19 in Wuhan. Medicine 99:e21413. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021413

Li, X., Yu, H., Bian, G., Hu, Z., Liu, X., Zhou, Q., et al. (2020c). Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical correlates of insomnia in volunteer and at home medical staff during the COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 140–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.008

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

Lim, G. Y., Tam, W. W., Lu, Y., Ho, C. S., Zhang, M. W., and Ho, R. C. (2018). Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and (2014). Sci. Rep. 8:2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x

Liu, C. Y., Yang, Y. Z., Zhang, X. M., Xu, X., Dou, Q. L., Zhang, W. W., et al. (2020). The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol. Infect. 148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107

Löwe, B., Gräfe, K., Zipfel, S., Witte, S., Loerch, B., and Herzog, W. (2004). Diagnosing ICD-10 depressive episodes: superior criterion validity of the patient health questionnaire. Psychother. Psychosom. 73, 386–390. doi: 10.1159/000080393

Lu, W., Wang, H., Lin, Y., and Li, L. (2020). Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936

Luceno-Moreno, L., Talavera-Velasco, B., Garcia-Albuerne, Y., and Martin-Garcia, J. (2020). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:5514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155514

Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., and Wang, H. (2020). The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190

Mitchell, A., Cummins, T., Spearing, N., Adams, J., and Gilroy, L. (2002). Nurses' experience with vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). J. Clin. Nurs. 11, 126–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00560.x

Naser, A. Y., Dahmash, E. Z., Al-Rousan, R., Alwafi, H., Alrawashdeh, H. M., Ghoul, I., et al. (2020). Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and University students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 10:e01730. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1730

Ni, M. Y., Yang, L., Leung, C. M. C., Li, N., Yao, X. I., Wang, Y., et al. (2020). Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment. Health 7:e19009. doi: 10.2196/19009

Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., and Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

Pouralizadeh, M., Bostani, Z., Maroufizadeh, S., Ghanbari, A., Khoshbakht, M., Alavi, S. A., et al. (2020). Anxiety and depression and the related factors in nurses of Guilan University of Medical Sciences hospitals during COVID-19: a web-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 13:100233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100233

Prasad, A., Civantos, A. M., Byrnes, Y., Chorath, K., Poonia, S., Chang, C., et al. (2020). Snapshot impact of COVID-19 on mental wellness in nonphysician otolaryngology health care workers: a national study. OTO Open 4:2473974X20948835. doi: 10.1177/2473974X20948835

Que, J., Shi, L., Deng, J., Liu, J., Zhang, L., Wu, S., et al. (2020). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen. Psychiatr. 33:e100259. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259

Rossi, R., Socci, V., Pacitti, F., Di Lorenzo, G., Di Marco, A., Siracusano, A., et al. (2020). Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw. Open 3:e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., et al. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Sandesh, R., Shahid, W., Dev, K., Mandhan, N., Shankar, P., Shaikh, A., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare professionals in Pakistan. Cureus 12:e8974. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8974

Shigemura, J., Ursano, R. J., Morganstein, J. C., Kurosawa, M., and Benedek, D. M. (2020). Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74:281–282. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12988

Si, M. Y., Su, X. Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, W. J., Gu, X. F., Ma, L., et al. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 9:113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0

Song, X., Fu, W., Liu, X., Luo, Z., Wang, R., Zhou, N., et al. (2020). Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., and Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Tan, B. Y. Q., Chew, N. W. S., Lee, G. K. H., Jing, M., Goh, Y., Yeo, L. L. L., et al. (2020). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 173, 317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083

Tu, Z. H., He, J. W., and Zhou, N. (2020). Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 99:e20769. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000020769

Wang, H., Huang, D., Huang, H., Zhang, J., Guo, L., Liu, Y., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study. Psychol. Med. 52, 1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002561

Wańkowicz, P., Szylińska, A., and Rotter, I. (2020). Assessment of mental health factors among health professionals depending on their contact with COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:5849. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165849

Xiao, X., Zhu, X., Fu, S., Hu, Y., Li, X., and Xiao, J. (2020). Psychological impact of healthcare workers in China during COVID-19 pneumonia epidemic: a multi-center cross-sectional survey investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.081

Xiaoming, X., Ming, A., Su, H., Wo, W., Jianmei, C., and Qi, Z. (2020). The psychological status of 8817 hospital workers during COVID-19 Epidemic: A cross-sectional study in Chongqing. J. Affect Disord. 276, 555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.092

Xiong, H., Yi, S., and Lin, Y. (2020). The psychological status and self-efficacy of nurses during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Inquiry 57:46958020957114. doi: 10.1177/0046958020957114

Xu, J., Xu, Q. H., Wang, C. M., and Wang, J. (2020). Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 288:112955. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112955

Zhang, C., Yang, L., Liu, S., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., et al. (2020a). Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 11:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306

Zhang, W. R., Wang, K., Yin, L., Zhao, W. F., Xue, Q., Peng, M., et al. (2020b). Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 89, 242–250. doi: 10.1159/000507639

Zhao, K., Zhang, G., Feng, R., Wang, W., Xu, D., Liu, Y., et al. (2020). Anxiety, depression and insomnia: a cross-sectional study of frontline staff fighting against COVID-19 in Wenzhou, China. Psychiatry Res. 292:113304. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113304

Zhu, J., Sun, L., Zhang, L., Wang, H., Fan, A., Yang, B., et al. (2020a). Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against Covid-19 in Gansu. Front. Psychiatry. 11:386. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00386

Zhu, Z., Xu, S., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Wu, J., Li, G., et al. (2020b). COVID-19 in Wuhan: Sociodemographic characteristics and hospital support measures associated with the immediate psychological impact on healthcare workers. EClin. Med. 24:100443. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100443

Keywords: mental health, anxiety, depression, insomnia, COVID-19, health care workers

Citation: Sun P, Wang M, Song T, Wu Y, Luo J, Chen L and Yan L (2021) The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:626547. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626547

Received: 09 November 2020; Accepted: 25 May 2021;

Published: 08 July 2021.

Edited by:

Martin Teufel, University of Duisburg-Essen, GermanyReviewed by:

Yesim Erim, University of Erlangen Nuremberg, GermanyCopyright © 2021 Sun, Wang, Song, Wu, Luo, Chen and Yan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lili Chen, MTg5MTA5MzEzMTFAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Lei Yan, eWFubGVpQHNkdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.