- 1Department of Respiratory, The Second Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

- 2Institute of Geriatrics, Beijing Key Laboratory of Aging and Geriatrics, National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics Diseases, The Second Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Occupational Disease Treatment, Medical Center of The Second Artillery, Beijing, China

- 4The Second Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

- 5Department of Nursing, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

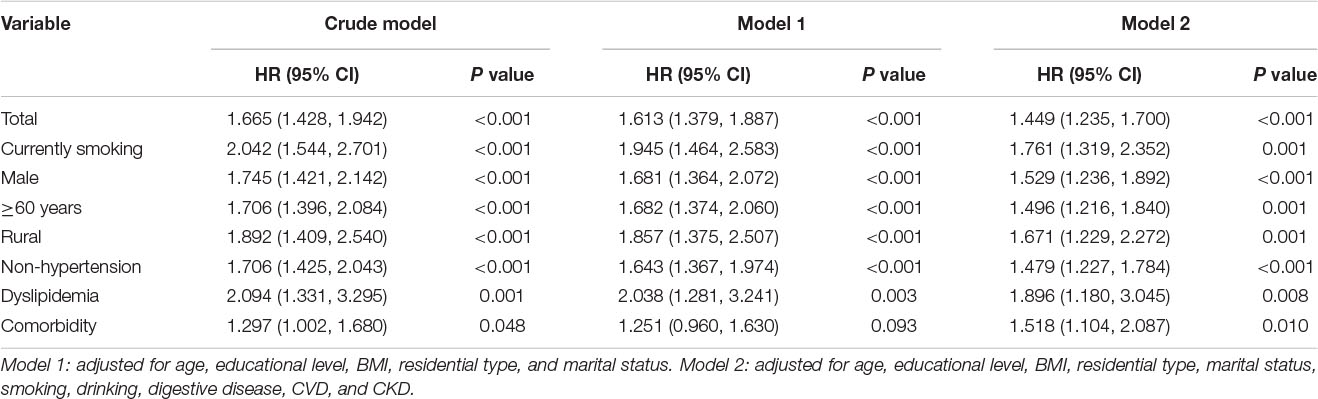

Chronic lung diseases (CLDs) can reduce patients’ quality of life. However, evidence for the relationship between CLD and occurrence with depressive symptoms remains unclear. This study aims to determine the associations between CLD and depressive symptoms incidence, using the data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). CLD was identified via survey questionnaire and hospitalization. The follow-up survey was conducted in 2018 and depressive symptoms were assessed by the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10). A total of 10,508 participants were studied with an average follow-up period of 3 years. A total of 2706 patients (25.8%) with newly diagnosed depressive symptoms were identified. The standardized incidence rate of depressive symptoms in baseline population with and without chronic pulmonary disease was 11.9/100 and 8.3/100 person-years, respectively. The Cox proportional risk model showed that CLD was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (HR: 1.449, 95% CI: 1.235–1.700) after adjusting for covariates, and the HRs of depressive symptoms were higher in those participants with current smoking (HR: 1.761, 95% CI: 1.319–2.352), men (HR: 1.529, 95% CI: 1.236–1.892), living in rural areas (HR: 1.671, 95% CI: 1.229–2.272), with dyslipidemia (HR: 1.896, 95% CI: 1.180–3.045), and suffering from comorbidity (HR: 1.518, 95% CI: 1.104–2.087) at baseline survey. CLD was an independent risk factor of depressive symptoms in China. The mental health of CLD patients deserves more attention.

Introduction

Depression has rapidly become a major public health problem worldwide. There are more than 8 million deaths and approximate 350 million people suffering from depressive symptoms to different degree every year (Whiteford et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2015; Vigo et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2017). Depressive disorders can cause a series of adverse consequences, such as disability, cognitive decline, functional damage, and even suicide (Steffens et al., 2006; Whiteford et al., 2013; Ismail et al., 2017). Depressive disorders contribute to the major global disease burden, and its contribution is rising (Whiteford et al., 2013). The years lived with disability (YLDs) caused by depressive disorders has increased by 37.6% from 1990 to 2010. Moreover, the global burden of mental disease may be seriously underestimated (Vigo et al., 2016).

In China, the disease burden of depressive disorders has been increasing gradually, and it becomes a huge and growing burden (Yang et al., 2013; Baxter et al., 2016). From 1990 to 2010, major depression was ranked the second leading cause of disability for both sexes and all ages in China (Yang et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2019). Additionally, unlike the developed countries, the general cognition awareness of mental illness is still at a low level in China (Xu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019).

The risk factors of depression over the 40 years of research were cognitive ability and cognitive process; unbearable stressors; certain sociodemographic factors, such as being female and living in a rural area; heredity; and so on (Seedat et al., 2009; Stein et al., 2014; Hammen, 2018). In addition, recent researches have presented that chronic lung disease (CLD) was the independent risk factor for depressive symptoms (Xiao et al., 2018; Sampaio et al., 2019). However, no conclusive evidences were well-established; the majority of studies were based on cross-sectional or convenience samples studies (van den Bemt et al., 2009; Crump et al., 2014). No related evidence based on prospective, national sample studies was found in China. Hence, a representative large-sample cohort study of Chinese middle-aged and elderly people from the community was used to determine the relationship between baseline CLD status and depressive symptoms incidence and also to explore the influence of sociodemographic factors and comorbidity on this association.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The current data in this study originated from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2015 wave 3 (Chen et al., 2019). This database is based on a randomized multistage stratified probability proportional sampling investigation, covering 150 counties and 450 communities/villages in 28 provinces and cities in China, involving more than 17,000 subjects aged 45 or above from 10,000 families. Details of the cohort design, methods, and follow-up plan for CHARLS have been published previously (Zhao et al., 2014). All relevant information of demographics, previous history of disease, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) were collected by trained staff. The follow-up survey was completed in 2018, and incident depressive symptoms were defined as the outcome event. CHARLS was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University and written informed consent was signed by each respondent.

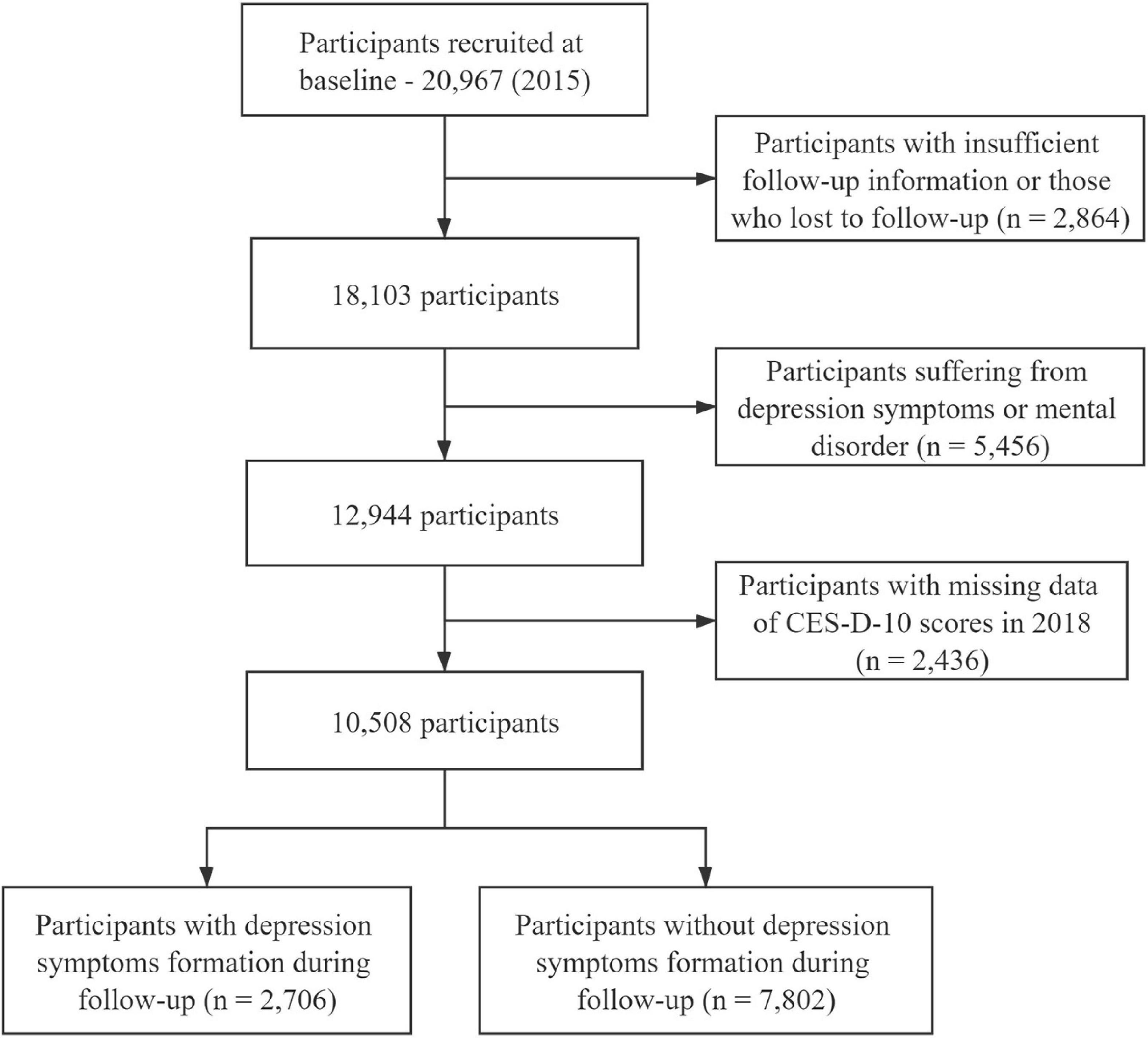

In the baseline survey wave, a total of 20,967 participants were included. After excluding those who lacked baseline information, were lost to follow-up, had been diagnosed with depressive symptoms at baseline survey, and were missing important variable data, a total of 10,508 eligible participants fully qualified for data analysis were enrolled. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of research participants.

Definitions

The CES-D-10 scale is administered to evaluate the depression symptom severity (Li et al., 2019). This scale consists of three items analyzing symptoms of depressed affect, five items assessing somatic symptoms, and two items estimating symptoms of positive affect. Response options for each item ranged from 0 to 5 (“rarely or none of the time” to “all of the time”), and the scores of items 5 and 8, which estimate positive affect, are reversed. The total score ranges from 0 to 30, where the higher the score, the more serious the depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were assessed using CES-D-10 at baseline and 3 years follow-up, and CES-D-10 with a cumulative score of 10 or more was considered to be of depressive symptoms in this study (Luo et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019).

Diagnoses of CLD, cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), dyslipidemia, diabetes, and digestive system disease were recorded based on the self-report. Smoking status was dichotomized into “yes” or “no,” and alcohol drinking status was divided into three categories (drink more than once a month, drink but less than once a month, and none) according to the questionnaire. To better understand the age differences between the CLD and occurrence of depressive symptoms, age was categorized into <60- and ≥60-year groups. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Blood pressure was measured twice in the right arm and the average SBP and DBP values were taken from the current study. According to the Chinese household registration system “hukou,” the residential type of the participants was classified into two groups: urban and rural. Participant educational level was categorized into three groups according to years of school (illiterate, 0 years; primary school, 1–6 years; middle school and above, ≥10 years). Presence of comorbidity was defined as no comorbidity versus comorbidity without or with CLD.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical interpretation of data was performed using packages R (The R Foundation)1 and EmpowerStats (X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA, United States)2. The continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), and the differences between participants with and without CLD were evaluated by Student’s t test. Categorical data were expressed as number of cases and percentage, and the differences of whether the participants suffered from CLD were analyzed by Chi-square test. Univariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the associations between baseline variable and depressive symptoms. Multivariate adjusted Cox proportional hazards model was performed to estimate HRs (95% CI) of CLD for depressive symptoms incidence. In multivariate model 1, adjusted variables were age, educational level, BMI, residential type, and marital status, and the adjusted variables of model 2 were model 1 plus smoking, drinking, digestive disease, CVD, and CKD. Stratified analysis was performed by gender, age group, rural/urban, and smoking status using multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Interactions between baseline variables and whether participants suffered from CLD were tested by adding each multiplicative factor in the Cox proportional hazards model. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

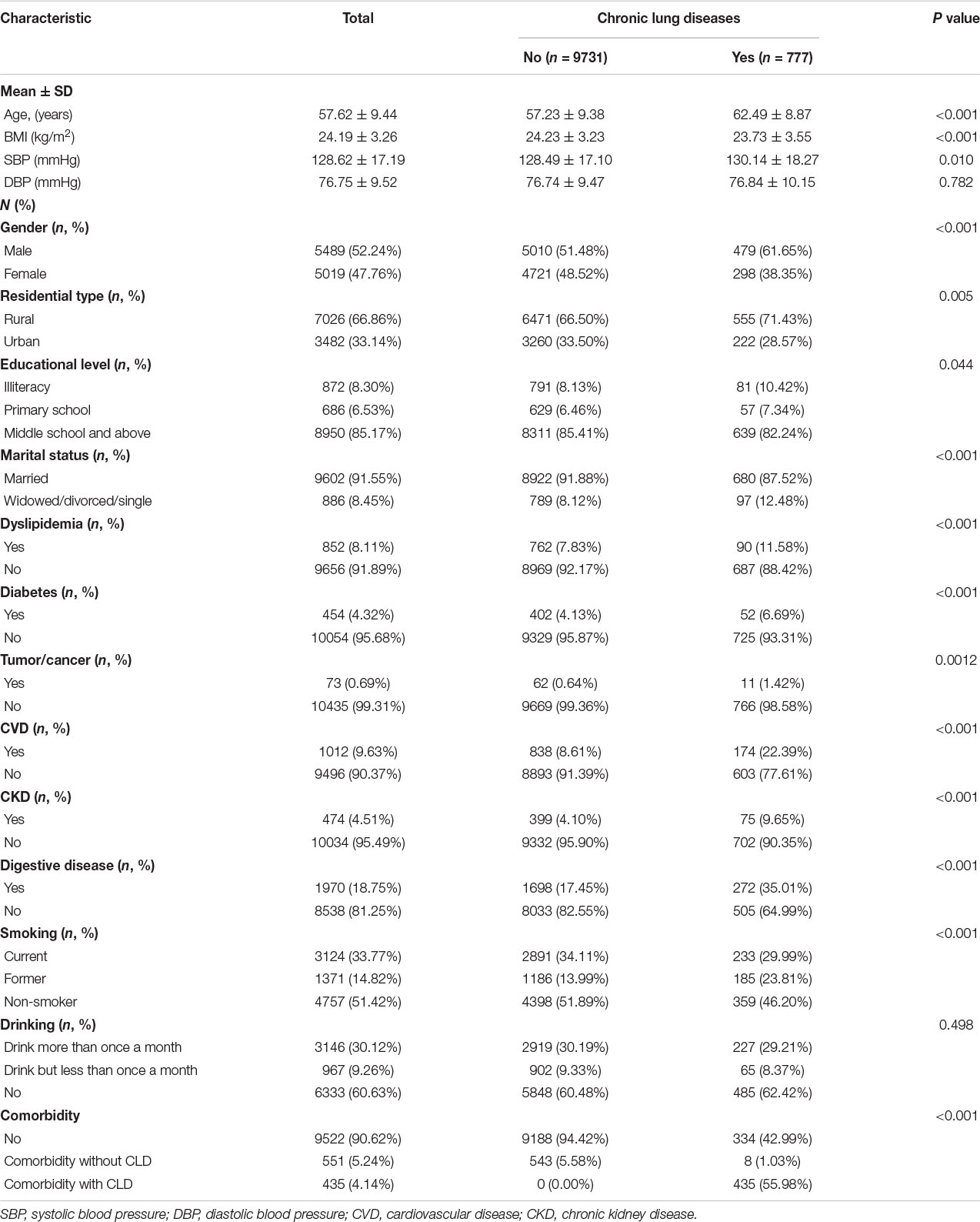

Baseline prevalence characteristics of CLD of 10,508 participants are shown in Table 1. The average age was 57.62 ± 9.44 years, 66.9% of the participants lived in rural areas, 85.2% had middle education, 33.8% were currently smoking, and 30.1% were drinking more than once a month. Regarding whether they are suffering from CLD, participants with CLD had older age, lower body mass index (BMI), lower systolic blood pressure (SBP), and lower smoking and drinking rates (P < 0.05). The prevalence of CLD was higher in men than in women, and higher in rural than in urban areas (P < 0.05). The participants with CLD had higher prevalence of CVD, CKD, and digestive disease than those without CLD (P < 0.001).

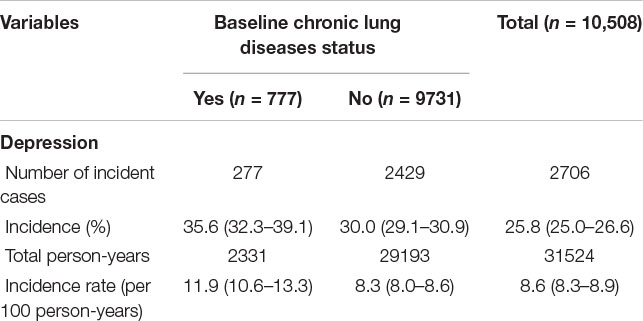

During the 31,254 person-years of follow-up, a total of 2706 participants were diagnosed with depressive symptoms. The incidence in 3 years was 25.8% (95% CI: 25.0–26.6%), and the incidence density (per 100 person-years) was 8.6% (95% CI: 8.3–8.9%). The standardized incidence rate of depressive symptoms in baseline population with and without CLD was 11.9% (95% CI: 10.6–13.3%) and 8.3% (95% CI: 8.0–8.6%), respectively. The incidence density of depressive symptoms was significantly higher in the participants with CLD than those without CLD (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

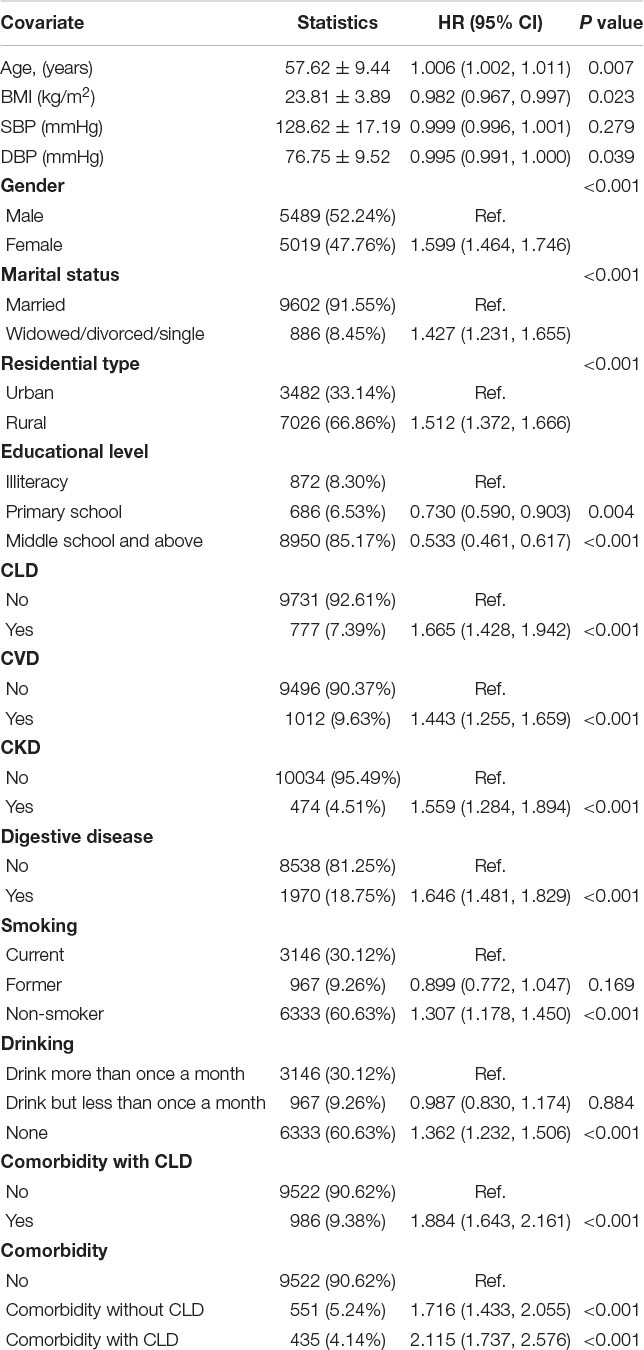

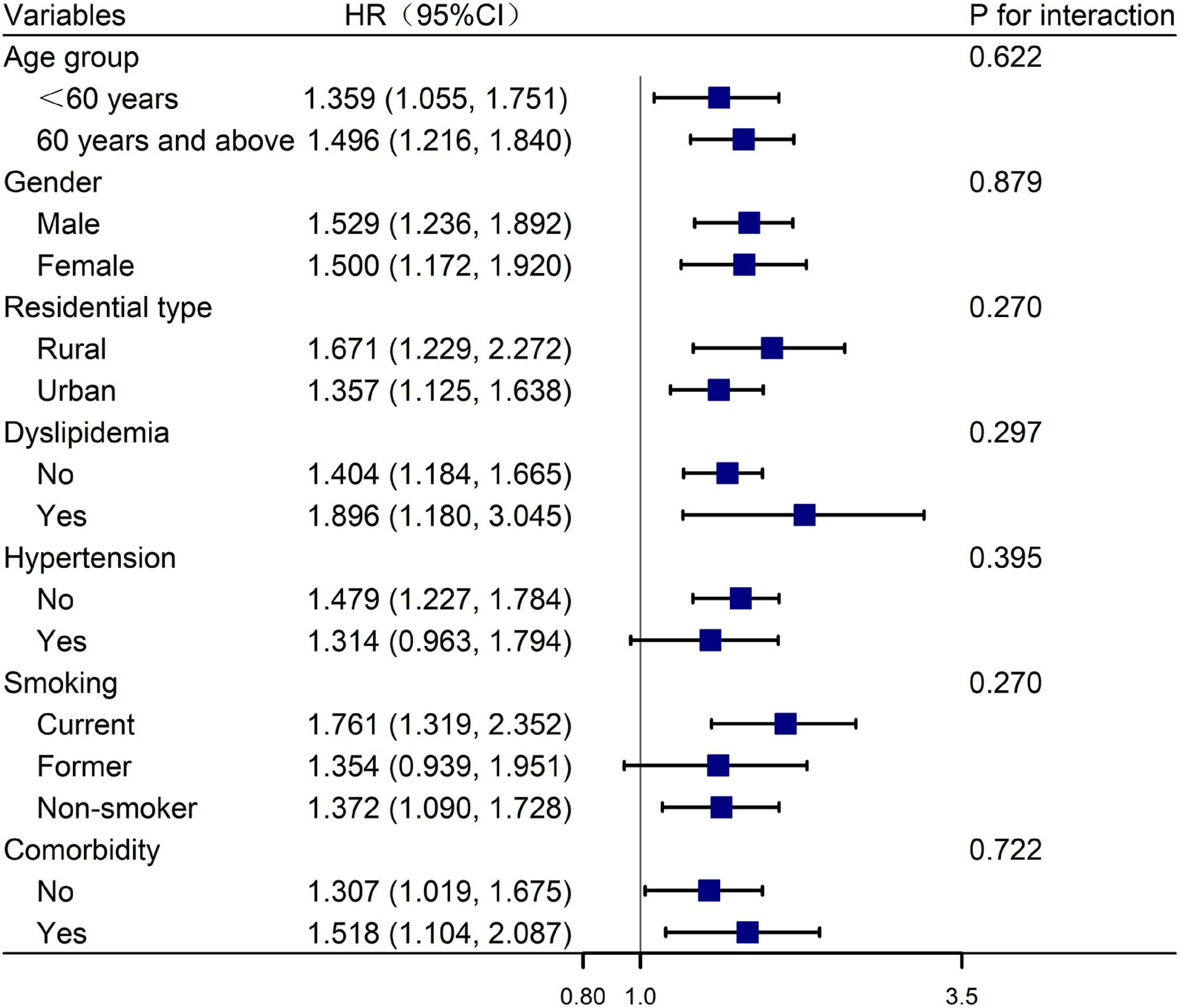

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis for depressive symptoms incidence. Table 4 presents the HRs of baseline CLD for depressive symptoms incidence during the follow-up and the subgroup analysis of the incidence of depressive symptoms according to smoking status, gender, age group, residential type, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and baseline comorbidity. After adjusting for age, gender, educational level, marital status, BMI, residential type, smoking, drinking, and baseline prevalence of CVD, CKD, and digestive disease, multivariate Cox regression showed that the adjusted HRs of depressive symptoms incidence caused by CLD was 1.449 (95% CI: 1.235–1.700). In the subgroup analysis, after the adjustment, compared with the general population, the adjusted HRs of depressive symptoms incidence were higher in those who were currently smoking, male, more than 60 years, living in rural areas, suffering from hypertension and dyslipidemia, and patients with comorbid conditions at baseline; the adjusted HRs were 1.761 (95% CI: 1.319–2.352), 1.529 (95% CI: 1.236–1.892), 1.496 (95% CI: 1.216–1.840), 1.671 (95% CI: 1.229–2.272), 1.479 (95% CI: 1.227–1.784), 1.896 (95% CI: 1.180–3.045), and 1.518 (95% CI: 1.104–2.087), respectively. There was no interaction between the subgroups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the relationship between baseline CLD status and depressive symptoms incidence. The blue square represents the HR value, and the line across the blue square represents the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

This nationally representative, community-based CHARLS (2015–2018) found that baseline CLD status was independently associated with depressive symptoms incidence, and this causality was more pronounced in those participants who were currently smoking, male, more than 60 years, living in rural areas, and suffering from hypertension and dyslipidemia and comorbid conditions at baseline.

Depressive symptoms are complex and a common mental order with high incidence in the general population, and people with persistent depressive symptoms have a higher likelihood of developing depression or even schizophrenia (McCann et al., 2018). Studies on the risk factors of depressive symptoms have been a hot topic. Due to the decline of life quality caused by CLD leading to psychological burden, the negative effects of CLD on psychological influence are increasingly focused, but with large ranges in different populations (Matte et al., 2016). CLDs are complex, common, and multifactorial chronic diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, pneumonia, and so on. Data from WHO Study on global Ageing and adult health (SAGE) Wave 1 (2007–2010) showed that participants with baseline CLD exhibited a 3.74-fold higher incidence of developing depressive symptoms (Lotfaliany et al., 2018). A multicenter prospective cohort study in Korea found that CLD represents an independent risk factor for depression (Lee et al., 2013). The follow-up results of CHARLS presented in our study were in agreement with most of the previous studies. Middle-aged and elderly people with baseline CLD status was independently associated with depressive symptoms incidence, providing evidence from Chinese large-sample population with national representation for this association.

This study has shown that the CLD participants living in rural areas have higher incidence of depressive symptoms than those living in urban areas. In China, the prevalence of depression shows marked regional differences, which in urban and rural areas are 16% and 30%, respectively (Yang et al., 2019). This may be related to the poor economic development and medical and health services in rural areas (Qiu et al., 2020). This effect is more pronounced among CLD participants who are living in rural areas. No significant gender difference existed in the association between CLD and depressive disorders.

Evidence has shown that harmful gasses and particulates produced by smoking can lead to airflow restriction, which was the main cause of depressive symptoms induced by CLD (Taghizadeh, 2018). Despite the inconsistent direction between smoking and depression, their close relationships are unquestionable. This suggests that smoking may increase the association between CLD and depressive symptoms incidence. The results of this study showed that the incidence was higher in those who are suffering from CLD and were more than 60 years old. Older adults are more prone to suffer from worse chronic diseases, higher prevalence of physical disability, poorer cognitive activity, and lower socioeconomic status, which might cause more severe depressive symptoms. Comorbidity imposed a heavy disease burden on patients and families, predicting higher likelihood of depression incidence (Essau, 2011; Boden and Foulds, 2016).

The present study has several strengths. CHARLS is a national representative, reliable, large-sample prospective cohort study of participants aged more than 45 years old. In addition, this study provides the prospective evidence about the influence of baseline CLD status on depressive disorders during the follow-up.

Still, some limitations exist. Firstly, all disease information was self-reported, and there also existed the possibility of under-reporting, which weakens the effect. Secondly, rate of lost to follow-up in the current study and depressive symptoms at baseline were relatively high, and the follow-up duration was also relatively short, which might reduce the magnitude of association between CLD and depressive symptoms, to a certain extent. Thirdly, the information about treatment and control of CLD and depressive symptoms was lacking. The incidence of depressive symptoms between participants with and without treatment cannot be compared.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that CLD was an independent risk factor for depressive symptoms in the middle-aged and elderly people, and the causality was more pronounced among those who were currently smoking, male, more than 60 years, living in rural areas, and suffering from hypertension and dyslipidemia and comorbid conditions. This suggested that the mental health of CLD patients deserves special attention.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: http://opendata.pku.edu.cn/.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Peking University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

XR, SW, YG, and YW were involved in the conception and design of the work. XR and SW contributed to writing the manuscript. XR, SW, YH, JL, and QL contributed to data arrangement and statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

Baxter, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Cheng, H. G., Shidhaye, R., Ferrari, A. J., and Whiteford, H. A. (2016). Prevalence of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: a systematic analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 832–841. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30139-0

Boden, J. M., and Foulds, J. A. (2016). Major depression and alcohol use disorder in adolescence: Does comorbidity lead to poorer outcomes of depression? J. Affect. Disord 206, 287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.004

Chen, X., Crimmins, E., Hu, P. P., Kim, J. K., Meng, Q., Strauss, J., et al. (2019). Venous blood-based biomarkers in the china health and retirement longitudinal study: rationale, design, and results of the 2015 wave. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 1871–1877. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz170

Crump, C., Sundquist, K., Sundquist, J., and Winkleby, M. A. (2014). Sociodemographic, psychiatric and somatic risk factors for suicide: a swedish national cohort study. Psychol. Med. 44, 279–289. doi: 10.1017/s0033291713000810

Essau, C. A. (2011). Comorbidity of substance use disorders among community-based and high-risk adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 185, 176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.033

Hammen, C. (2018). Risk factors for depression: an autobiographical review. Annu. Rev. Clin Psychol. 14, 1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084811

Huang, D., Yang, L. H., and Pescosolido, B. A. (2019). Understanding the public’s profile of mental health literacy in China: a nationwide study. BMC Psychiatry 19:20. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1980-8

Ismail, Z., Elbayoumi, H., Fischer, C. E., Hogan, D. B., Millikin, C. P., Schweizer, T., et al. (2017). Prevalence of depression in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 58–67. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3162

Lee, Y. S., Park, S., Oh, Y. M., Lee, S. D., Park, S. W., Kim, Y. S., et al. (2013). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test can predict depression: a prospective multi-center study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 28, 1048–1054. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.7.1048

Li, M., Yang, Y., Pang, L., Wu, M., Wang, Z., Fu, Y., et al. (2019). Gender-specific associations between activities of daily living disability and depressive symptoms among older adults in China: evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 33, 160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.08.010

Lotfaliany, M., Bowe, S. J., Kowal, P., Orellana, L., Berk, M., and Mohebbi, M. (2018). Depression and chronic diseases: co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. J. Affect. Disord 241, 461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.011

Luo, H., Li, J., Zhang, Q., Cao, P., Ren, X., Fang, A., et al. (2018). Obesity and the onset of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in China: evidence from the CHARLS. BMC Public Health 18:909. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5834-6

Matte, D. L., Pizzichini, M. M., Hoepers, A. T., Diaz, A. P., Karloh, M., Dias, M., et al. (2016). Prevalence of depression in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Respir Med. 117, 154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.006

McCann, T. V., Savic, M., Ferguson, N., Cheetham, A., Witt, K., Emond, K., et al. (2018). Recognition of, and attitudes towards, people with depression and psychosis with/without alcohol and other drug problems: results from a national survey of Australian paramedics. BMJ Open 8:e023860. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023860

Qiu, Q. W., Li, J., Li, J. Y., and Xu, Y. (2020). Built form and depression among the Chinese rural elderly: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 10:e038572. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038572

Sampaio, M. S., Vieira, W. A., Bernardino, ÍM., Herval, ÁM., Flores-Mir, C., and Paranhos, L. R. (2019). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 151, 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.03.018

Seedat, S., Scott, K. M., Angermeyer, M. C., Berglund, P., Bromet, E. J., Brugha, T. S., et al. (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 785–795. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36

Steffens, D. C., Otey, E., Alexopoulos, G. S., Butters, M. A., Cuthbert, B., Ganguli, M., et al. (2006). Perspectives on depression, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 130–138.

Stein, A., Pearson, R. M., Goodman, S. H., Rapa, E., Rahman, A., McCallum, M., et al. (2014). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 384, 1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61277-0

Taghizadeh, F. (2018). “Efficacy of smoking cessation with guided self-change therapy on depression, stress and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial,” in Proceedings of the Addiction 2018, (Dubai).

van den Bemt, L., Schermer, T., Bor, H., Smink, R., van Weel-Baumgarten, E., Lucassen, P., et al. (2009). The risk for depression comorbidity in patients with COPD. Chest 135, 108–114. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0965

Vigo, D., Thornicroft, G., and Atun, R. (2016). Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 171–178. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00505-2

Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E., and Druss, B. G. (2015). Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., et al. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 382, 1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61611-6

Whiteford, H. A., Ferrari, A. J., Degenhardt, L., Feigin, V., Vos, T., and Forloni, G. J. P. O. (2010). The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One 10:e0116820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116820

World Health Organization (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Xiao, T., Qiu, H., Chen, Y., Zhou, X., Wu, K., Ruan, X., et al. (2018). Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and their associated factors in mild COPD patients from community settings, Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 18:89. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1671-5

Xu, Z., Huang, F., Kösters, M., and Rüsch, N. (2017). Challenging mental health related stigma in China: Systematic review and meta-analysis. II. Interventions among people with mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 255, 457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.002

Yang, G., Wang, Y., Zeng, Y., Gao, G. F., Liang, X., Zhou, M., et al. (2013). Rapid health transition in China, 1990-2010: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 381, 1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61097-1

Yang, Z., Chen, R., Hu, X., and Ren, X. H. (2019). Factors that related to the depressive symptoms among elderly in urban and rural areas of China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 38, 1088–1093. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.08.018

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J., and Yang, G. (2014). Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203

Keywords: chronic lung diseases, depressive symptoms, cohort study, association, risk variants

Citation: Ren X, Wang S, He Y, Lian J, Lu Q, Gao Y and Wang Y (2021) Chronic Lung Diseases and the Risk of Depressive Symptoms Based on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Psychol. 12:585597. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.585597

Received: 21 July 2020; Accepted: 18 March 2021;

Published: 22 July 2021.

Edited by:

Xiao Zhou, Zhejiang University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Ren, Wang, He, Lian, Lu, Gao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuling Wang, d2FuZ3l1bGluZzMwMUAxNjMuY29t; Yanhong Gao, MTczMDEyODUwNjVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xueling Ren

Xueling Ren Shengshu Wang

Shengshu Wang Yan He3

Yan He3