- 1Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME, United States

- 2Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, United States

- 3Palliative Medicine Program, Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME, United States

- 4Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME, United States

Background: Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is an important cause of suffering for cancer survivors, and both empirical evidence and theoretical models suggest that prognostic uncertainty plays a causal role in its development. However, the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR is incompletely understood.

Objective: To explore the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR among patients with ovarian cancer (OC).

Design: A qualitative study was conducted utilizing individual in-depth interviews with a convenience sample of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer who had completed first-line treatment with surgery and/or chemotherapy. Semi-structured interviews explored participants’ (1) understanding of their prognosis; (2) experiences, preferences, and attitudes regarding prognostic information; and (3) strategies for coping with prognostic uncertainty. Inductive qualitative analysis and line-by-line software-assisted coding of interview transcripts was conducted to identify key themes and generate theoretical insights on the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR.

Results: The study sample consisted of 21 participants, nearly all of whom reported experiencing significant FCR, which they traced to an awareness of the possibility of a bad outcome. Some participants valued and pursued prognostic information as a means of coping with this awareness, suggesting that prognostic uncertainty causes FCR. However, most participants acknowledged fundamental limits to both the certainty and value of prognostic information, and engaged in various strategies aimed not at reducing but constructing and maintaining prognostic uncertainty as a means of sustaining hope in the possibility of a good outcome. Participants’ comments suggested that prognostic uncertainty, fear, and hope are connected by complex, bi-directional causal pathways mediated by processes that allow patients to cope with, construct, and maintain their uncertainty. A provisional dual-process theoretical model was developed to capture these pathways.

Conclusion: Among patients with OC, prognostic uncertainty is both a cause and an effect of FCR—a fear-inducing stimulus and a hope-sustaining response constructed and maintained through various strategies. More work is needed to elucidate the relationships between prognostic uncertainty, fear, and hope, to validate and refine our theoretical model, and to develop interventions to help patients with OC and other serious illnesses to achieve an optimal balance between these states.

Introduction

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is an important cause of suffering for cancer survivors and a topic of intense interest for clinicians and researchers. Broadly defined as “fear, worry, or concern relating to the possibility that cancer will come back or progress” (Lebel et al., 2016), FCR has been measured in different ways and found to be associated with various negative outcomes including psychological distress, diminished quality of life, and higher health care utilization (Lebel et al., 2013; Champagne et al., 2018; Mutsaers et al., 2020). Several theoretical models have been developed to explain the causes and effects of FCR, and the strategies patients use to cope with it (Lee-Jones et al., 1997; Fardell et al., 2016; Simonelli et al., 2016; Curran et al., 2017; Lebel et al., 2018). These models emphasize different factors and processes, but share a common view of prognostic uncertainty as a primary cause of FCR (Crist and Grunfeld, 2013; Simard et al., 2013; Hall et al., 2018; Tauber et al., 2019). Referencing Mishel’s influential Uncertainty in Illness Theory, several models construe uncertainty as a deficit state—specifically, an “inability to determine the meaning of illness-related events” (Mishel, 1988)—that provokes FCR both directly and indirectly (Fardell et al., 2016; Simonelli et al., 2016; Curran et al., 2017; Lebel et al., 2018).

This view of prognostic uncertainty as a primary cause of FCR is consistent with a vast body of research documenting the many aversive psychological effects of uncertainty (Afifi and Weiner, 2004; Han, 2013; Hillen et al., 2017b). At the same time, however, it reflects and reinforces a narrow conception of the nature, function, and beneficial effects of uncertainty. In treating uncertainty solely as a deficit state—a mere “inability” or absence of knowledge—it disregards how it also represents a form of knowledge in its own right: a metacognitive awareness of ignorance that serves the adaptive function of enabling individuals to cope with threats (Han et al., 2011). It overlooks potential beneficial effects of uncertainty, such as the maintenance of hope in the face of ignorance about the future (Babrow, 1992; Babrow and Kline, 2000; Brashers et al., 2000; Brashers, 2001). This benefit may explain why patients with serious life-limiting illness strive not only to decrease prognostic uncertainty, but to increase and maintain it in various ways—including actively avoiding prognostic information and embracing uncertainty in prognostic estimates (Fallowfield et al., 1995; Butow et al., 1997, 2002; Kutner et al., 1999; Hagerty et al., 2004, 2005; Kirk et al., 2004; Helft, 2005; Elkin et al., 2007; Hancock et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2008; Innes and Payne, 2009; Bilcke et al., 2011; Rayson, 2013; Han, 2016). These responses suggest the need to move beyond construing prognostic uncertainty solely as a cause of FCR and other psychological states, to adopt a broader, bi-directional view that accounts for the alternative role of prognostic uncertainty as an effect of FCR—a consequence of patients’ efforts to cope with their fear.

The overarching aim of the current study was to explore this alternative role and the potential bi-directional causal pathways that link prognostic uncertainty and FCR among patients with ovarian cancer (OC). The most lethal gynecologic malignancy and fifth leading cause of cancer deaths among United States women, OC has a high risk of recurrence and progression and OC survivors have a correspondingly high degree of FCR (Wenzel et al., 2002; Shinn et al., 2009; Roland et al., 2013; Ozga et al., 2015; Kyriacou et al., 2017; Galica et al., 2020). The experiences of OC survivors may thus yield valuable insights on the causes and effects of FCR, and the specific aim of the current study was to explore these experiences to better understand how prognostic uncertainty might represent not only an aversive cause but an adaptive effect of FCR. Appropriate to this exploratory aim, the study employed in-depth, semi-structured qualitative interviews with individual OC survivors, which allowed survivors themselves to describe their lived experiences in detail, and to account for the relationships between prognostic uncertainty and FCR in their own words. The study thus allowed us to generate testable hypotheses about these relationships and to develop a tentative, provisional theoretical model to guide future research on the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR among cancer survivors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Participants, and Recruitment

The study utilized individual qualitative interviews with a convenience sample of patients with epithelial ovarian or fallopian tube cancer, recruited from the Gynecologic Oncology Service of a large urban 637-bed teaching hospital. Eligible participants consisted of patients with Stage I–IV disease, determined by surgical or clinical staging after biopsy-confirmed diagnosis, who had completed first-line treatment with surgery and/or chemotherapy. In order to minimize potential psychological harms that might be caused by asking patients to discuss prognosis-related topics including the prospect of their own death, patients were excluded if they reported significant levels of cancer-specific emotional distress on routine screening using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Thermometer (Holland et al., 2001) (scores ≥ 3). Eligible and interested patients were identified by practice staff during regularly scheduled office visits and recruited by the research team, who informed participants of the study’s voluntary and exploratory nature and its overall focus on the topic of prognosis. Participants were provided a $25 (USD) incentive. We aimed for a minimum sample size of 20 based on available study resources and our prior qualitative research exploring similar themes with cancer survivors (Han et al., 2013; Hillen et al., 2017a). The study was approved by the Maine Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection and Interview Content

From July 2018 to November 2019, individual in-person interviews, lasting approximately 45–60 min each, were conducted by trained qualitative researchers (CG, HM, PH) with no professional or personal relationships with participants. Interviews were semi-structured and followed a moderator guide developed by our multi-disciplinary research team and consisting of open-ended questions and close-ended probes designed to elicit participants’ (1) prognostic understanding; (2) experiences, preferences, and attitudes regarding prognostic information; and (3) strategies for coping with prognostic uncertainty (Appendix). During the course of the study, minor revisions were made in the interview guide to clarify and further explore emergent themes. All interviews were audio-recorded with prior consent of participants, and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service.

Data Analysis

In-depth qualitative analysis and line-by-line software-assisted coding of anonymized interview transcripts was conducted using the qualitative analysis software program MaxQDATM. The analysis utilized an inductive, constant comparative approach aimed at minimizing preconceptions, identifying key themes and relationships between them, and generating new theoretical understandings (Glaser, 1965; Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Four investigators—a palliative medicine physician and behavioral researcher with expertise in medical uncertainty (PH), an experienced qualitative health researcher (CG), a palliative medicine physician and health services researcher (RH), and a medical sociologist (AF)—first developed a working codebook by reading eight transcripts, inductively identifying themes in participants’ verbatim statements (open coding), and then categorizing emergent themes according to their content (axial coding) (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Ryan and Bernard, 2003; Corbin and Strauss, 2014). The investigators met after coding each transcript to compare coding decisions, resolve areas of disagreement, and refine the codebook. The remaining 13 transcripts were double-coded by pairs of researchers (PH and CG, or PH and RH), who met regularly to compare new data, concepts, and themes, to resolve further disagreements, and to refine the codebook. One researcher (PH) conducted further analysis of identified themes and developed an integrative conceptual model with feedback from the research team.

Results

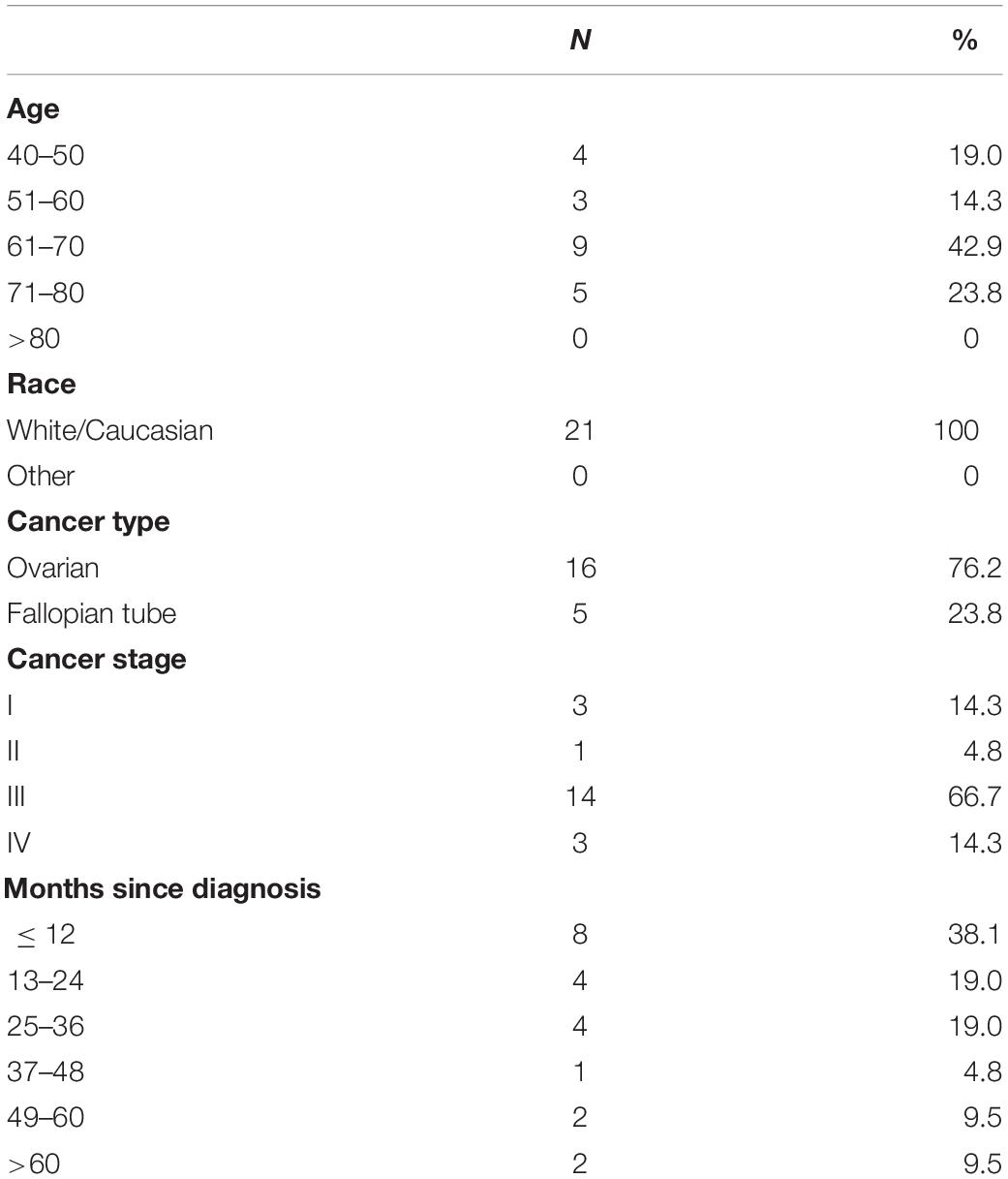

The study sample (Table 1) consisted of 21 participants, most of whom reported experiencing prognostic uncertainty and FCR at some point in their illness. Their descriptions of the relationship between these phenomena suggested two different views: (1) prognostic uncertainty as a cause of FCR, and (2) prognostic uncertainty as an effect of FCR. Supporting the former view, participants described managing FCR by pursuing prognostic certainty. Supporting the latter view, participants described managing FCR by pursuing prognostic uncertainty, and further identified various strategies that they used to construct and maintain this uncertainty. These views, furthermore, were not mutually exclusive; some participants endorsed both at once.

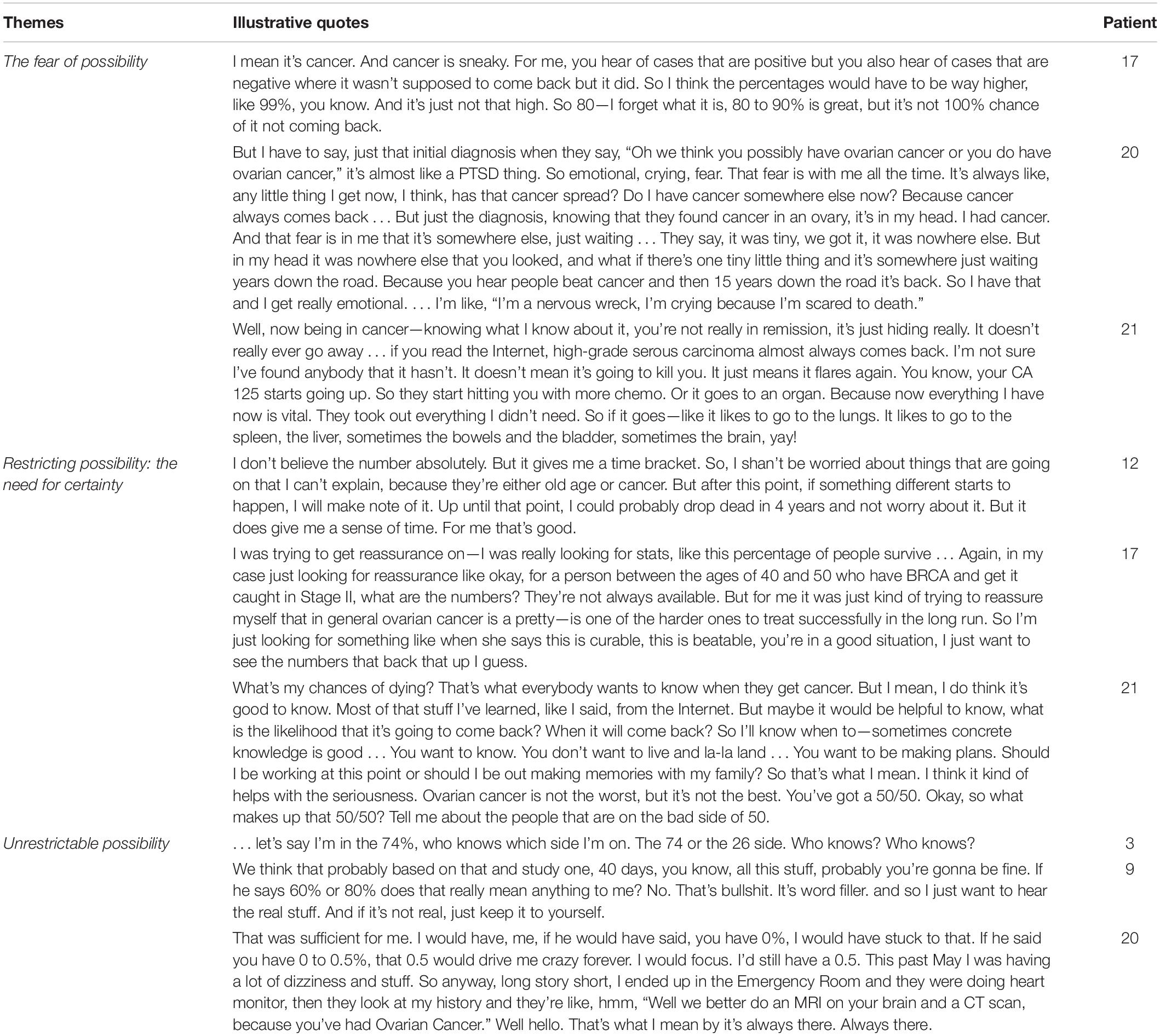

Prognostic Uncertainty as a Cause of FCR

Consistent with prevailing theories of FCR, study participants described prognostic uncertainty as a primary cause of their fear, which they managed by pursuing prognostic certainty.

The Fear of Possibility

Study participants’ accounts suggested that prognostic uncertainty was associated with higher FCR. Participants reported experiencing the greatest uncertainty and fear at the time of their initial cancer diagnosis, and during follow-up visits and diagnostic testing (bloodwork and radiologic imaging studies) for cancer surveillance. Participants’ comments further suggested that FCR originated not only from uncertainty per se, but from a negative bias in its perception and interpretation: a selective, pessimistic focus on worst-case possibilities, which clinical psychologists have termed a “catastrophizing” response to uncertainty (Robichaud, 2013). This bias was manifest in several study participants’ tendency to equate prognostic uncertainty with worst-case outcomes including cancer recurrence, progression, and death (Table 2). One participant (Patient 15), for example, traced the fear she felt at the time of her routine follow-up visits both to the inability to know whether or not her illness “was going to end badly,” and to an irresistible urge to imagine the worst: “every time I come here I’m panicked, just because it is scary to think that I could come back at any time and have a re-occurrence.” Other participants exhibited the same pessimistic bias in describing their cancer as a “hiding,” “sneaky” threat lurking “somewhere else, just waiting” to return and spread.

Restricting Possibility: The Pursuit of Certainty

Further supporting the view of prognostic uncertainty as a primary cause of FCR, participants reported managing their fear by pursuing prognostic certainty. This pursuit served the critical function of restricting future possibilities—that is, narrowing the range of potential outcomes—which made them more tolerable (Table 2). One participant (Patient 12) argued that reducing her prognosis to a finite “time bracket” gave her a “sense of time” that lessened her worry. Other participants (Patients 17, 21) similarly reported that by limiting the range of possible outcomes, prognostic information imposed a concrete order that enabled them to set priorities in their lives—a function they perceived as valuable regardless of how unfavorable their prognosis might have been.

Unrestrictable Possibility

At the same time, study participants acknowledged fundamental limits in the extent to which prognostic possibilities could be restricted. Participants argued that medical experts “don’t really know” the prognosis of individuals (Patient 2), that statistics “are not about people” because they simply “mix together” individual lives (Patient 7), and that even precise prognostic estimates do not answer the question of their own fate (Table 2). Participants thus recognized that the range of their potential outcomes could never be narrowed sufficiently to include knowledge of their own personal fate; prognostic certainty was unachievable. This recognition was a source of distress for many participants; Patient 20, for example, reported that even a small “0.5%” probability of a bad outcome was enough to “drive me crazy forever.” Such responses lend further support to the view of prognostic uncertainty as a primary cause of FCR.

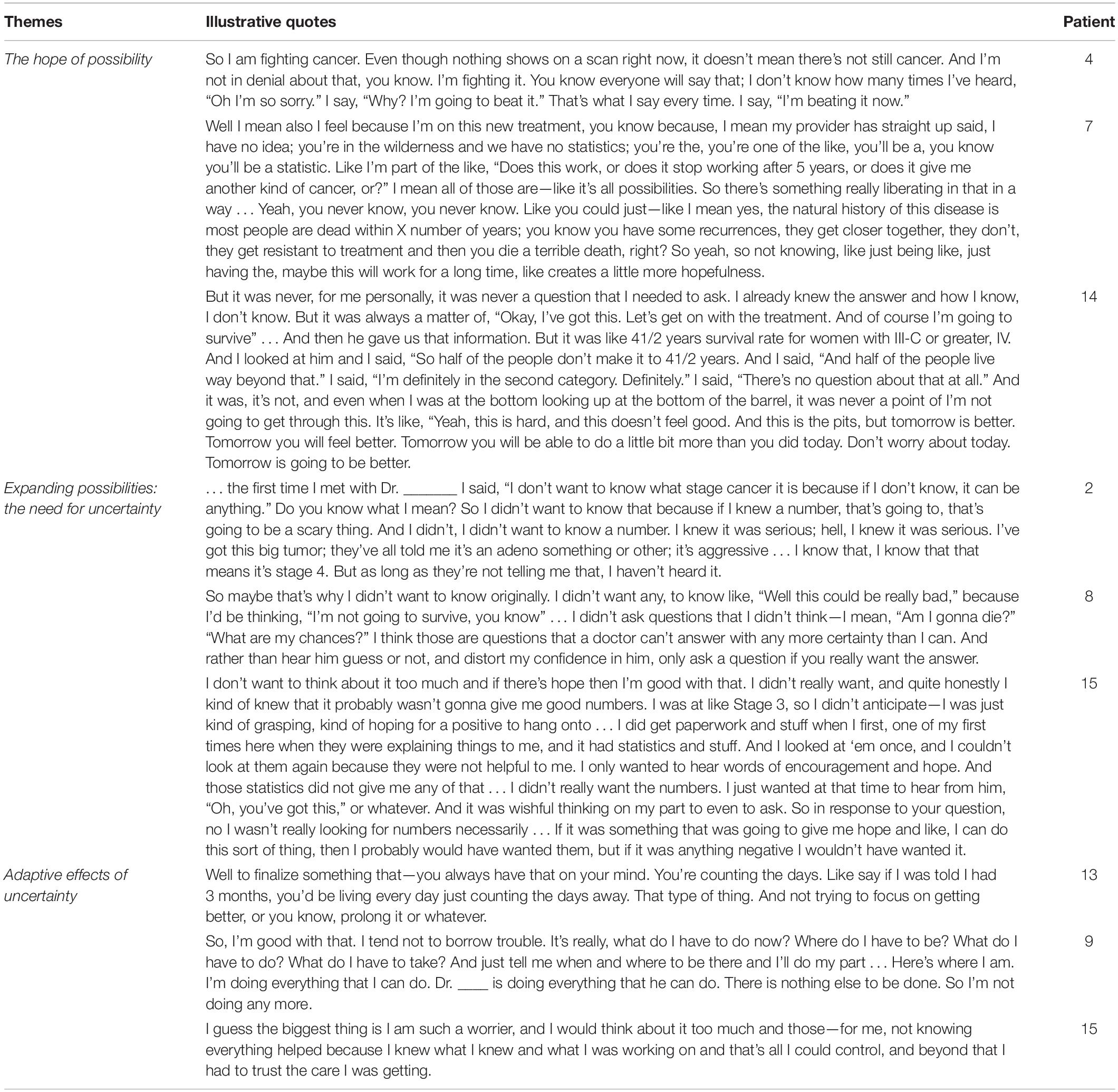

Prognostic Uncertainty as an Effect of FCR

Yet study participants’ accounts of their experiences suggested that prognostic uncertainty was not merely a primary cause but also a secondary effect of FCR: an adaptive response as well as an aversive stimulus, a source of hope as well as fear (Table 3).

The Hope of Possibility

Study participants’ accounts suggested that prognostic uncertainty was associated not only with higher but lower FCR. Participants’ comments further suggested that this association may have originated from a positive bias in the perception and interpretation of uncertainty: a selective, optimistic focus on best-case possibilities, which might be termed “optimizing”—in contrast to the “catastrophizing” that resulted in the fear of possibility. This opposing focus made prognostic uncertainty a source of hope as well as fear. One participant (Patient 5) viewed even the smallest possibility of a best-case outcome as a reason for hope: “even if there was a 1% chance, I was like it didn’t matter,” she asserted, adding that “We don’t know what they can do.” In a similar vein, Patient 4 focused on the possibility of “beating” her cancer, in deliberate defiance of the high likelihood that her cancer would recur. Patient 7 acknowledged the “liberating” nature of the fact that all future outcomes—both bad and good—ultimately represent mere possibilities, and affirmed how the awareness of this fact “creates a little more hopefulness” (Table 3). For all of these participants, in other words, prognostic uncertainty signified the possibility of not only realizing a dreaded outcome—cancer recurrence, progression, death—but averting these outcomes. Uncertainty was thus a source of not only fear but hope.

Expanding Possibility: The Pursuit of Uncertainty

Corroborating the alternative view of prognostic uncertainty as a secondary effect of FCR rather than a primary cause, study participants reported coping with their fear by increasing rather than decreasing their uncertainty. Prognostic uncertainty was a key goal for many participants, who described conscious efforts to maintain ignorance about their future as a way of expanding the range of prognostic possibilities to include desirable as well as undesirable outcomes (Table 3). Patient 2 put it pointedly: “I don’t want to know what stage cancer it is because if I don’t know, it can be anything.” Patient 15 acknowledged her poor prognosis but reported actively foregoing more precise prognostic information—intentionally maintaining prognostic ignorance and uncertainty. For this and other patients, uncertainty kept prognostic possibilities open, and thus served the vital function of preserving hope in a better future.

Adaptive Effects of Uncertainty

Related to—yet independent of—its hope-preserving function, furthermore, prognostic uncertainty had other important, psychologically adaptive effects (Table 3). One was to prevent patients from resigning from further efforts to fight their disease; Patient 13 viewed such a response as a danger of prognostic certainty and a rationale for preserving prognostic uncertainty. Another adaptive effect of uncertainty, acknowledged by multiple study participants, was to help them focus attention on issues within their control and to disengage from issues that were not. One participant (Patient 9) viewed maintaining prognostic uncertainty as part of a general strategy “not to borrow trouble”—to let go and simply attend to the pragmatic task of “doing what I can do.” Other participants affirmed that prognostic uncertainty had the added benefit of allowing them to cease thinking and worrying about their future outcomes, as Patient 15 put it—and to “trust the care I was getting.”

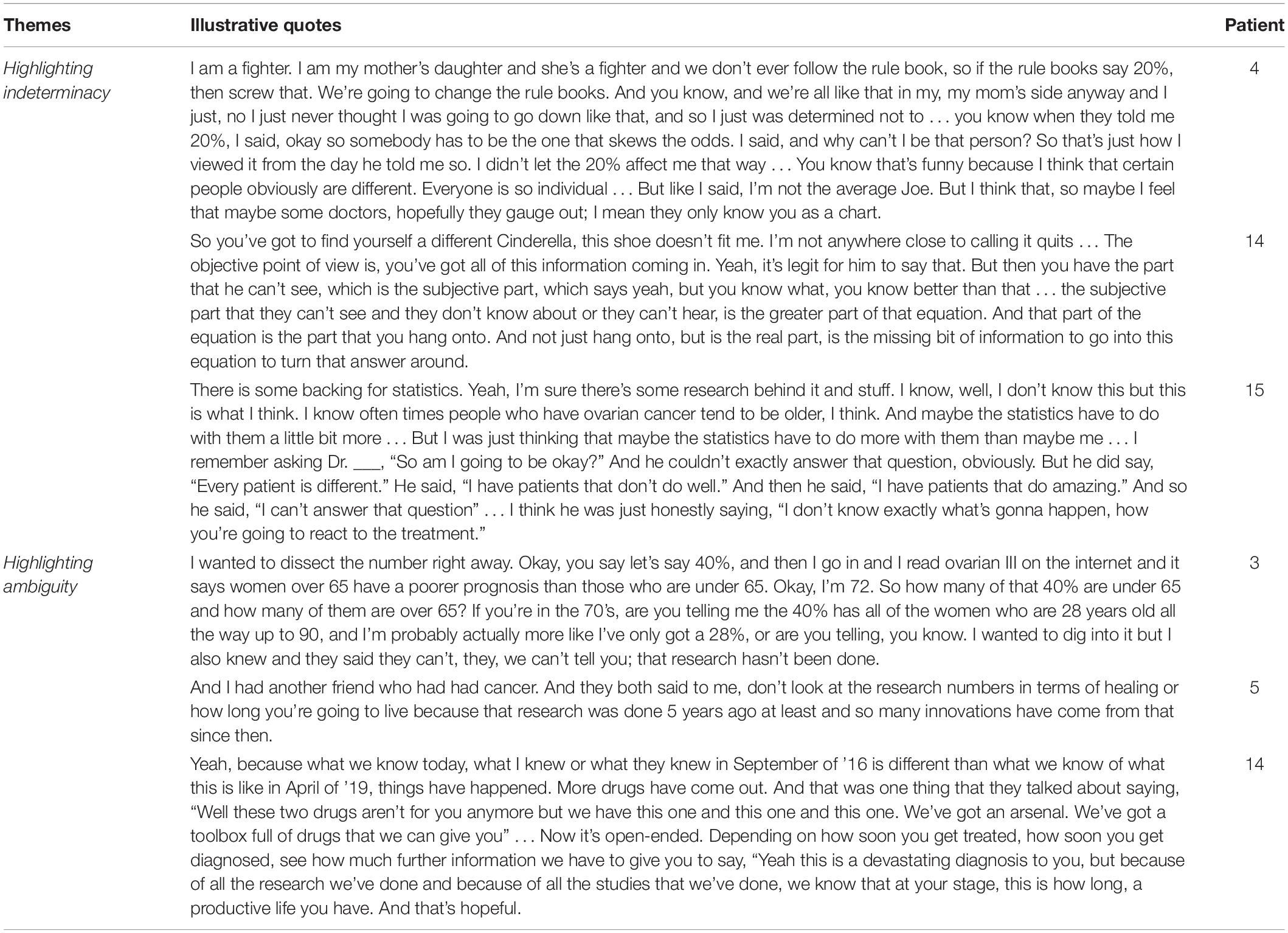

Constructing Prognostic Uncertainty

Further supporting the conception of uncertainty as an effect rather than a cause of FCR, study participants not only pursued prognostic uncertainty by foregoing prognostic information, but actively constructed it by engaging in two strategies: (1) highlighting the indeterminacy of their personal prognosis, and (2) highlighting ambiguity in prognostic information (Table 4). These strategies reinforced participants’ prognostic uncertainty, which further enabled them to maintain hope in a favorable outcome.

Highlighting Indeterminacy

The most commonly reported way in which study participants constructed uncertainty was by highlighting the indeterminacy of their prognosis. Nearly all participants expressed a belief in the uniqueness of individual patients, and in the inability of statistics to account for all possible determinants of their own, personal prognosis—e.g., age, medical history, family history, positive attitude, and lifestyle. These beliefs affirm long-recognized epistemological problems that limit the precision and value of all probability estimates for individuals, and engender what philosophers of statistics have called aleatory uncertainty (Hacking, 1975; Gillies, 2000). Study participants, however, embraced and highlighted this uncertainty because it allowed them to believe that prognostic estimates did not apply to them, and that their personal prognosis was thus alterable. Folkman (2010) referred to this cognitive reappraisal process as “personalizing the odds.” As Patient 4 affirmed, “I think that certain people obviously are different. Everyone is so individual”; she went on to assert that she was “not the average Joe” and would “change the rule books” in fighting her cancer (Table 4). Another patient stated that she purposefully avoided seeking prognostic information because “Whatever it [prognostic estimate] says, I want to be the outlier” (Patient 5). The effort to highlight prognostic indeterminacy to preserve the possibility of beating the odds, furthermore, appeared to involve physicians as well as patients. Participants recounted how their physicians used language supporting the personal inapplicability of prognostic information—e.g., “Every patient is different” (Patient 15), and “your situation is a little different” (Patient 17). Patient 21 stated that her physician refrained from providing any prognostic estimate precisely for this reason: “And she’s never—she still hasn’t given me survivability odds. She just says that I am my own case. She says, ‘You know it’s really difficult to give that kind of definite knowledge because everybody is so individual.”’ These accounts suggest that physicians played an important role in co-constructing prognostic indeterminacy with patients as a means of maintaining hope in beating the odds.

Highlighting Ambiguity

Another important way in which study participants constructed prognostic uncertainty was by highlighting limitations in the reliability, credibility, or adequacy of prognostic information—features of information that produce what decision theorists have termed “ambiguity” (Ellsberg, 1961; Camerer and Weber, 1992). Ambiguity in prognostic information arises from missing or conflicting risk evidence or methodological limitations that produce imprecise, conflicting, or changing estimates, leading to what philosophers of statistics have called epistemic uncertainty. Study participants highlighted the ambiguity of prognostic information in several ways, including acknowledging the imprecision or unreliability of prognostic estimates for particular patient subgroups, due to shortcomings in empirical evidence—e.g., “research hasn’t been done” (Patient 3) (Table 4). Other participants noted how prognostic knowledge is unstable and “changing at every moment” (Patient 21) due to ongoing scientific advances. Highlighting these ambiguities of prognostic information reinforced participants’ uncertainty, further broadening the range of their possible futures to include favorable outcomes.

Maintaining Prognostic Uncertainty

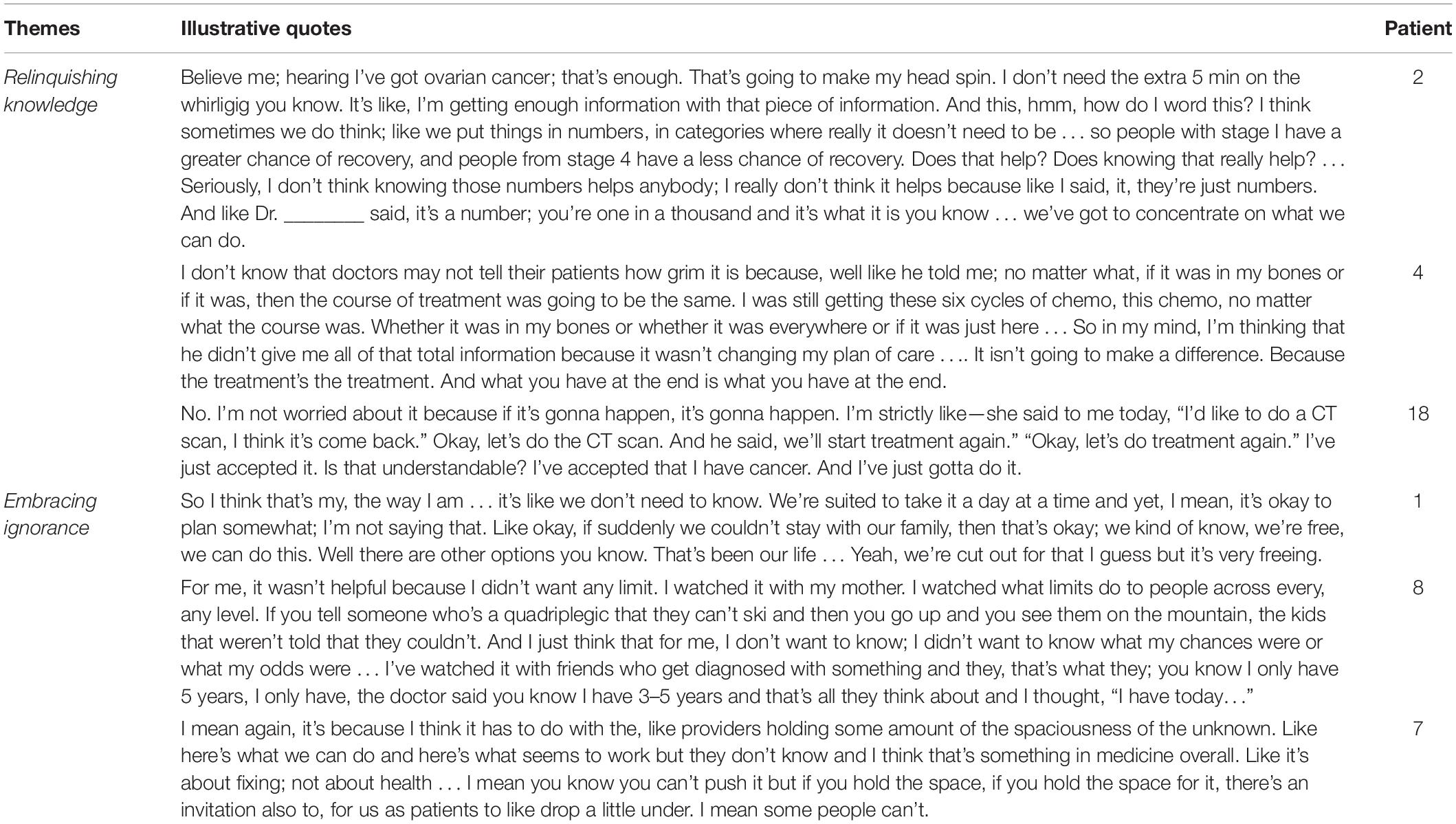

Study participants described how they not only construct uncertainty by acknowledging key limitations of prognostic information, but actively maintain it by engaging in two other general strategies—relinquishing knowledge and embracing ignorance—which enabled them to both sustain hope and better tolerate their uncertainty.

Relinquishing Knowledge

A primary strategy that participants used to maintain prognostic uncertainty consisted of relinquishing prognostic knowledge and its pursuit. Several participants viewed their prognosis as a moot question given that only one course of action—to pursue treatment—offered any hope of controlling their cancer; prognostic knowledge thus served no practical purpose. In this vein, Patient 2 argued that simply knowing she had OC was enough, and that her priority was simply “to concentrate on what we can do,” while Patient 4 disavowed prognostic knowledge because it would not change her “plan of care” (Table 5). Other participants added that prognostic knowledge was not only practically but existentially irrelevant. Patient 18 affirmed a need to accept whatever future outcomes might lie ahead, and to simply deal with her illness one step at a time. The practical and existential irrelevance of prognostic information led these participants to relinquish prognostic knowledge and its pursuit—especially as time went on and their illnesses progressed—which had the ultimate effect of sustaining their uncertainty and making it more tolerable.

Embracing Ignorance

Yet study participants reported maintaining prognostic uncertainty by engaging in not only the negative act of relinquishing knowledge about their prognosis, but the positive act of embracing ignorance. Apart from the basic desire to maintain prognostic ignorance in order to expand the range of future possibilities to include hopeful outcomes (Table 3), participants also described a positive affinity for ignorance, which served other fundamental life goals. Patient 1 reported that embracing ignorance about her future provided a sense of freedom and openness that allowed her to “take it a day at a time” (Table 5). Patient 8 embraced ignorance about her prognosis because she “didn’t want any limit” to what was possible; she believed that acknowledging a poor prognosis posed the risk of turning into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Patient 7 evocatively described this same orientation toward ignorance as a capacity for “holding some amount of the spaciousness of the unknown”—for affirming prognostic ignorance and preventing it from collapsing into premature or excessive certainty about one particular outcome or another.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR among survivors of OC. To our knowledge it is the first study to focus on bi-directional causal pathways between these phenomena in this population, and to provide evidence of the role of prognostic uncertainty as an effect as well a cause of FCR, an adaptive response as well as an aversive stimulus. Study participants vividly described how uncertainty can not only provoke but ameliorate FCR and sustain hope in the face of an unknown and threatening future. They further reported using various strategies to cope with uncertainty and FCR, and identified several psychological processes that may mediate the relationships between uncertainty, FCR, and hope. These findings are clearly provisional given their qualitative nature; more research will be needed to confirm the causal nature and direction of the relationships identified. In the meantime, however, these findings generate testable hypotheses and provide the basis for a provisional new theoretical model that can guide future empirical research on the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR among cancer survivors.

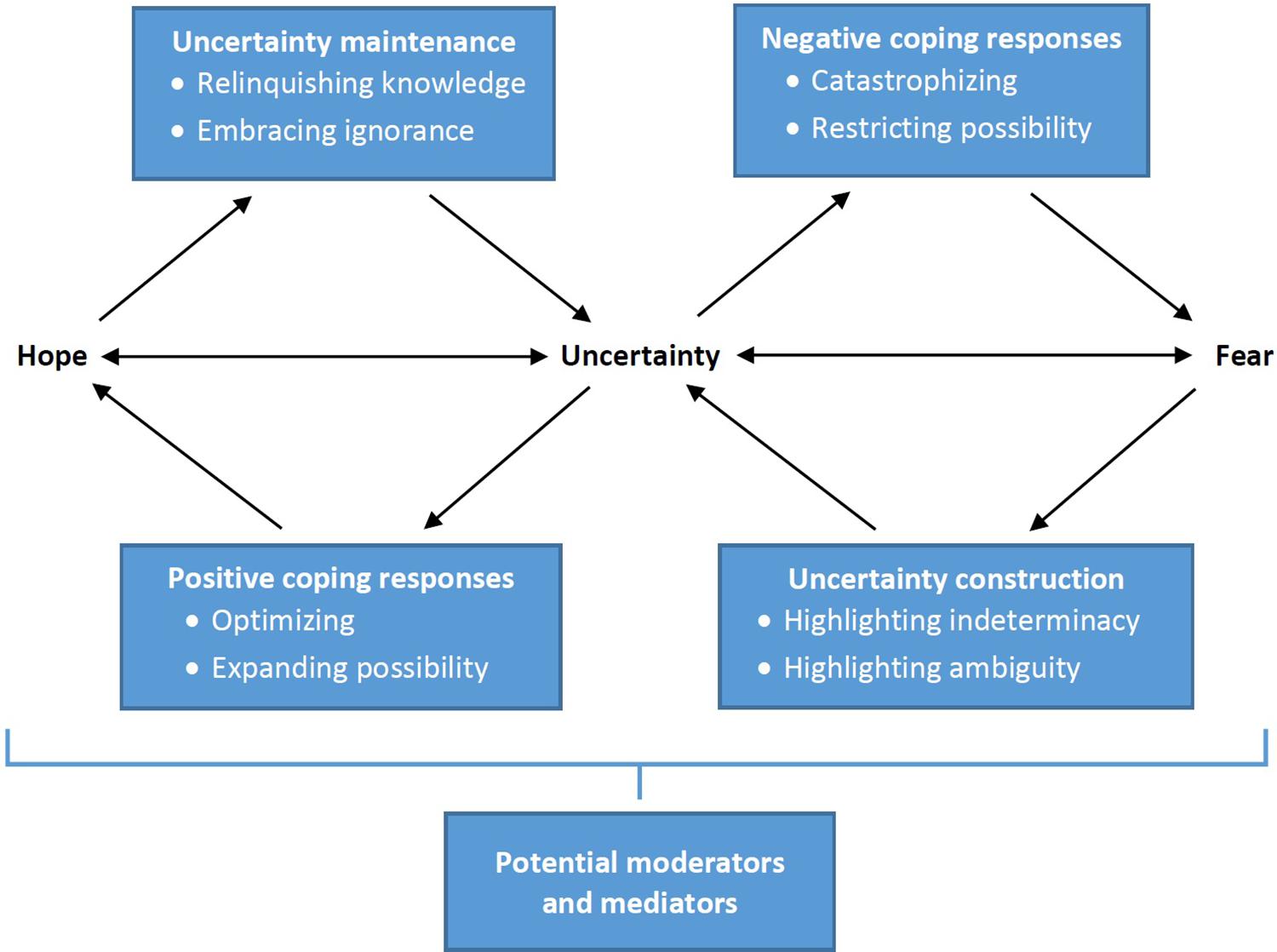

This provisional theoretical model is presented in Figure 1. Uncertainty occupies the center of this model, affirming both its primary importance in the lives of patients with cancer, and its fundamentally ambiguous, dual nature and function: it is at once a cause and an effect, a source of fear and hope, and a mediating variable between these states. Conventional theories of FCR focus on the direct uncertainty-fear pathway on the right-hand side of the model. For example, the model developed by Fardell et al. (2016) identifies “lack of information” about risk of recurrence as a direct cause of FCR, while integrative models of FCR put forth by Simonelli et al. (2016) and Curran et al. (2017) construe uncertainty as a primary trigger of subsequent cognitive appraisal processes that, in turn, produce FCR. A “blended” model of FCR developed by Lebel et al. (2018) characterizes uncertainty as a primary factor that moderates the effect of internal and external triggers (e.g., physical symptoms) on perceived risk of cancer recurrence, which then leads to FCR. The common feature of all these models is that they situate uncertainty upstream in the causal pathways that lead to FCR, and do not identify uncertainty-specific negative coping processes (e.g., catastrophizing, restricting possibility) that mediate the effects of prognostic uncertainty on FCR. Most importantly, they ignore potential reverse-causal pathways by which fear might induce uncertainty, and the uncertainty construction processes (e.g., highlighting the indeterminacy of prognosis and the ambiguity of prognostic information) that might mediate this pathway.

Figure 1. Dual-process equilibrium model of the relationship between prognostic uncertainty, fear of cancer recurrence, and hope.

This new model acknowledges a whole other side of the phenomenon: the critical role of prognostic uncertainty in promoting not only the fear of cancer recurrence but the hope of cancer non-recurrence. The hope-promoting function of uncertainty as a more general phenomenon has been acknowledged in conceptual models put forth by health communication theorists Babrow (1992) and Brashers (2001); however, much remains unknown about the causal pathways connecting uncertainty and hope. In the current model fear and hope are simply inverse responses to the complementary possibilities posed by uncertainty; fear manifests a focus on negative, undesirable possibilities, hope a focus on positive, desirable ones. The model is a dual-process conception that postulates a mirror-image causal pathway by which uncertainty induces hope through the mediating action of positive coping processes (optimizing, expanding possibility), as well as a reverse-causal pathway in which hope induces uncertainty through the mediating action of uncertainty maintenance processes (relinquishing knowledge, embracing ignorance).

This dual-process model thus clarifies that uncertainty is an essential source of both fear and hope, and exactly which of these states predominates at any given time is determined by how individuals balance different positive and negative uncertainty coping strategies. The degree of uncertainty that individuals experience, in turn, is determined by how they balance different uncertainty construction and maintenance strategies. In other words, uncertainty, fear, and hope are interdependent states that exist in dynamic equilibrium and influence one another through different feedback loops. Uncertainty can initiate either a self-perpetuating, vicious cycle of fear, or a similarly self-perpetuating, virtuous cycle of hope. On the one hand, prognostic uncertainty can stimulate primarily negative coping responses that promote FCR, which then stimulates uncertainty construction processes that promote even more uncertainty, which then stimulates further negative coping responses, and so on. On the other hand, prognostic uncertainty can stimulate primarily positive coping responses that promote hope of cancer non-recurrence, which then stimulates uncertainty maintenance processes that promote uncertainty, which then stimulates further positive coping responses, and so on.

More research is needed to elucidate the factors that cause patients to either enter or exit these opposing, self-perpetuating cycles, to experience more or less prognostic uncertainty, to refocus attention on either negative or positive possibilities, or to shift the balance of their psychological responses to uncertainty from fear to hope or vice versa. One important mediating factor may be physicians and physician-patient communication; our data suggest that physicians collude with patients to highlight indeterminacy and ambiguity in prognostic estimates, and thereby co-construct the prognostic uncertainty that both parties need to maintain hope. One important moderating factor may be individual differences in patients’ uncertainty tolerance; past research suggests that uncertainty tolerance influences the extent to which individuals perceive uncertainty and respond to it in negative vs. positive ways (Hillen et al., 2017a; Strout et al., 2018; Anderson et al., 2019). These and various other factors may mediate and moderate the causal pathways connecting uncertainty, fear, and hope, and warrant further research.

Our dual-process, equilibrium model of uncertainty provides a guiding framework and set of testable hypotheses for this research. The intermediary processes connecting uncertainty and fear (negative coping responses, uncertainty construction processes) and uncertainty and hope (positive coping responses, uncertainty maintenance processes) can be measured and their effects quantified. In the meantime, our model also raises important normative questions for research on FCR, including how much prognostic uncertainty ought to be constructed and maintained, what negative and positive coping responses are appropriate, and what balance of fear and hope is optimal. Unmitigated fear clearly causes significant suffering and is maladaptive; however, the same may be true for unmitigated hope, which may lead to unrealistic expectations and a “distortion of reality”(Folkman, 2010). More research, both empirical and conceptual, is needed to determine when particular responses are not only psychologically adaptive but morally appropriate, and why.

This study had several limitations that qualify its findings and call for further research. It was conducted at a single institution using a relatively small and racially homogeneous convenience sample of female OC patients with primarily advanced-stage disease. Study recruitment was driven by available study resources rather than thematic saturation; although the repeated occurrence of key themes across the interviews suggested a high degree of thematic saturation, important themes could have been missed. Larger studies, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative methods and more sociodemographically and clinically diverse patient populations, are needed to determine the validity of our findings and theoretical model.

In spite of these limitations, our study provides valuable empirical evidence and a new theoretical model of the relationship between prognostic uncertainty and FCR—and between uncertainty, fear, and hope as more general phenomena. In this model prognostic uncertainty has a dual nature—it is both a cause and an effect, a source of fear as well as hope—and which of these natures predominates at any given time manifests a dynamic equilibrium between dual, opposing processes that promote negative vs. positive coping responses. It remains for future research to confirm our findings, to validate and refine our theoretical model, and to develop interventions that can help patients with OC and other serious illnesses to achieve an optimal balance between uncertainty, fear, and hope.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they consist of qualitative interview data containing potentially sensitive information, and participants have not given consent for their broader use. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author cGF1bC5oYW4wOUBnbWFpbC5jb20=.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Maine Medical Center Research Institute IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

PH contributed to the conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, supervision, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. CG contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing, and project administration. RH contributed to the formal analysis and writing – review and editing. JL contributed to the conceptualization, resources, project administration, and writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by institutional funding from the Maine Medical Center Research Institute.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank the many patients who generously contributed their time and insights to this study, and Anny Fenton and Hayley Mandeville for assistance with the qualitative interviews and data analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.626038/full#supplementary-material

References

Afifi, W. A., and Weiner, J. L. (2004). Toward a theory of motivated information management. Commun. Theory 14, 167–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00310.x

Anderson, E. C., Carleton, R. N., Diefenbach, M., and Han, P. K. J. (2019). The relationship between uncertainty and affect. Front. Psychol. 10:2504. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02504

Babrow, A. S. (1992). Communication and problematic integration: understanding diverging probability and value, ambiguity, ambivalence, and impossibility. Commun. Theory 2, 95–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.1992.tb00031.x

Babrow, A. S., and Kline, K. N. (2000). From “reducing” to “coping with” uncertainty: reconceptualizing the central challenge in breast self-exams. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 1805–1816. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00112-x

Bilcke, J., Beutels, P., Brisson, M., and Jit, M. (2011). Accounting for methodological, structural, and parameter uncertainty in decision-analytic models: a practical guide. Med. Decis. Making 31, 675–692. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11409240

Brashers, D. E. (2001). Communication and uncertainty management. J. Commun. 51, 477–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02892.x

Brashers, D. E., Neidig, J. L., Haas, S. M., Dobbs, L. K., Cardillo, L. W., and Russell, J. A. (2000). Communication in the management of uncertainty: the case of persons living with HIV and AIDS. Commun. Monogr. 67, 63–84. doi: 10.1080/03637750009376495

Butow, P. N., Brown, R. F., Cogar, S., Tattersall, M. H., and Dunn, S. M. (2002). Oncologists’ reactions to cancer patients’ verbal cues. Psychooncology 11, 47–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.556

Butow, P. N., Maclean, M., Dunn, S. M., Tattersall, M. H., and Boyer, M. J. (1997). The dynamics of change: cancer patients’ preferences for information, involvement and support. Ann. Oncol. 8, 857–863. doi: 10.1023/a:1008284006045

Camerer, C., and Weber, M. (1992). Recent developments in modeling preferences: uncertainty and ambiguity. J. Risk Uncertain. 5, 325–370. doi: 10.1007/bf00122575

Champagne, A., Ivers, H., and Savard, J. (2018). Utilization of health care services in cancer patients with elevated fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology 27, 1958–1964. doi: 10.1002/pon.4748

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Crist, J. V., and Grunfeld, E. A. (2013). Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 22, 978–986. doi: 10.1002/pon.3114

Curran, L., Sharpe, L., and Butow, P. (2017). Anxiety in the context of cancer: a systematic review and development of an integrated model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 56, 40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.06.003

Elkin, E. B., Kim, S. H., Casper, E. S., Kissane, D. W., and Schrag, D. (2007). Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: elderly cancer patients’ preferences and their physicians’ perceptions. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 5275–5280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1922

Ellsberg, D. (1961). Risk, ambiguity, and the savage axioms. Q. J Econ 75, 643–669. doi: 10.2307/1884324

Fallowfield, L., Ford, S., and Lewis, S. (1995). No news is not good news: information preferences of patients with cancer. Psychooncology 4, 197–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.2960040305

Fardell, J. E., Thewes, B., Turner, J., Gilchrist, J., Sharpe, L., Smith, A., et al. (2016). Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. J. Cancer Surviv. 10, 663–673. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0512-5

Galica, J., Giroux, J., Francis, J. A., and Maheu, C. (2020). Coping with fear of cancer recurrence among ovarian cancer survivors living in small urban and rural settings: a qualitative descriptive study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 44, 101705. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.101705

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc. Probl. 12, 436–445. doi: 10.1525/sp.1965.12.4.03a00070

Hagerty, R. G., Butow, P. N., Ellis, P. A., Lobb, E. A., Pendlebury, S., Leighl, N., et al. (2004). Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 1721–1730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.095

Hagerty, R. G., Butow, P. N., Ellis, P. M., Lobb, E. A., Pendlebury, S. C., Leighl, N., et al. (2005). Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 1278–1288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.138

Hall, D. L., Luberto, C. M., Philpotts, L. L., Song, R., Park, E. R., and Yeh, G. Y. (2018). Mind-body interventions for fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 27, 2546–2558. doi: 10.1002/pon.4757

Han, P. K. (2013). Conceptual, methodological, and ethical problems in communicating uncertainty in clinical evidence. Med. Care Res. Rev. MCRR 70(1 Suppl.), 14S–36S. doi: 10.1177/1077558712459361

Han, P. K. (2016). The need for uncertainty: a case for prognostic silence. Perspect. Biol. Med. 59, 567–575. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2016.0049

Han, P. K., Hootsmans, N., Neilson, M., Roy, B., Kungel, T., Gutheil, C., et al. (2013). The value of personalised risk information: a qualitative study of the perceptions of patients with prostate cancer. BMJ Open 3:e003226. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003226

Han, P. K., Klein, W. M., and Arora, N. K. (2011). Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med. Decis. Making 31, 828–838. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11393976

Hancock, K., Clayton, J. M., Parker, S. M., Walder, S., Butow, P. N., Carrick, S., et al. (2007). Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat. Med. 21, 507–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823

Helft, P. R. (2005). Necessary collusion: prognostic communication with advanced cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 3146–3150. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.07.003

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Smets, E. M. A., Hansen, M., Kungel, T. M., Strout, T. D., et al. (2017a). The evolution of uncertainty in second opinions about prostate cancer treatment. Health Expect. 20, 1264–1274. doi: 10.1111/hex.12566

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Strout, T. D., Smets, E. M., and Han, P. K. J. (2017b). Tolerance of uncertainty: conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 180, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024

Holland, J. C., Jacobsen, P. B., and Riba, M. B. (2001). NCCN: distress management. Cancer Control 8(6 Suppl. 2), 88–93.

Innes, S., and Payne, S. (2009). Advanced cancer patients’ prognostic information preferences: a review. Palliat. Med. 23, 29–39. doi: 10.1177/0269216308098799

Kirk, P., Kirk, I., and Kristjanson, L. J. (2004). What do patients receiving palliative care for cancer and their families want to be told? A Canadian and Australian qualitative study. BMJ 328:1343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38103.423576.55

Kutner, J. S., Steiner, J. F., Corbett, K. K., Jahnigen, D. W., and Barton, P. L. (1999). Information needs in terminal illness. Soc. Sci. Med. 48, 1341–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00453-5

Kyriacou, J., Black, A., Drummond, N., Power, J., and Maheu, C. (2017). Fear of cancer recurrence: a study of the experience of survivors of ovarian cancer. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 27, 236–242. doi: 10.5737/23688076273236242

Lebel, S., Maheu, C., Tomei, C., Bernstein, L. J., Courbasson, C., Ferguson, S., et al. (2018). Towards the validation of a new, blended theoretical model of fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology 27, 2594–2601. doi: 10.1002/pon.4880

Lebel, S., Ozakinci, G., Humphris, G., Mutsaers, B., Thewes, B., Prins, J., et al. (2016). From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24, 3265–3268. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5

Lebel, S., Tomei, C., Feldstain, A., Beattie, S., and McCallum, M. (2013). Does fear of cancer recurrence predict cancer survivors’ health care use? Support Care Cancer 21, 901–906. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1685-3

Lee-Jones, C., Humphris, G., Dixon, R., and Hatcher, M. B. (1997). Fear of cancer recurrence–a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology 6, 95–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199706)6:2<95::AID-PON250<3.0.CO;2-B

Mutsaers, B., Butow, P., Dinkel, A., Humphris, G., Maheu, C., Ozakinci, G., et al. (2020). Identifying the key characteristics of clinical fear of cancer recurrence: an international Delphi study. Psychooncology 29, 430–436. doi: 10.1002/pon.5283

Ozga, M., Aghajanian, C., Myers-Virtue, S., McDonnell, G., Jhanwar, S., Hichenberg, S., et al. (2015). A systematic review of ovarian cancer and fear of recurrence. Palliat. Support Care 13, 1771–1780. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000127

Robichaud, M. (2013). Cognitive behavior therapy targeting intolerance of uncertainty: application to a clinical case of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn. Behav. Practice 20, 251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.09.001

Robinson, T. M., Alexander, S. C., Hays, M., Jeffreys, A. S., Olsen, M. K., Rodriguez, K. L., et al. (2008). Patient-oncologist communication in advanced cancer: predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer 16, 1049–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0372-2

Roland, K. B., Rodriguez, J. L., Patterson, J. R., and Trivers, K. F. (2013). A literature review of the social and psychological needs of ovarian cancer survivors. Psychooncology 22, 2408–2418. doi: 10.1002/pon.3322

Ryan, G. W., and Bernard, H. R. (2003). “Data management and analysis methods,” in Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 259–309.

Shinn, E. H., Taylor, C. L., Kilgore, K., Valentine, A., Bodurka, D. C., Kavanagh, J., et al. (2009). Associations with worry about dying and hopelessness in ambulatory ovarian cancer patients. Palliat. Support Care 7, 299–306. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990228

Simard, S., Thewes, B., Humphris, G., Dixon, M., Hayden, C., Mireskandari, S., et al. (2013). Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Cancer Surviv. 7, 300–322. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

Simonelli, L. E., Siegel, S. D., and Duffy, N. M. (2016). Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and its relevance for clinical presentation and management. Psychooncology 26, 1444–1454. doi: 10.1002/pon.4168

Strauss, A. L., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strout, T. D., Hillen, M., Gutheil, C., Anderson, E., Hutchinson, R., Ward, H., et al. (2018). Tolerance of uncertainty: a systematic review of health and healthcare-related outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 101, 1518–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.030

Tauber, N. M., O’Toole, M. S., Dinkel, A., Galica, J., Humphris, G., Lebel, S., et al. (2019). Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 2899–2915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00572

Keywords: uncertainty, fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), qualitative study, theoretical model, prognosis, ovarian cancer

Citation: Han PKJ, Gutheil C, Hutchinson RN and LaChance JA (2021) Cause or Effect? The Role of Prognostic Uncertainty in the Fear of Cancer Recurrence. Front. Psychol. 11:626038. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.626038

Received: 04 November 2020; Accepted: 22 December 2020;

Published: 15 January 2021.

Edited by:

Phyllis Noemi Butow, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Anne Brédart, Institut Curie, FranceKatriina Whitaker, University of Surrey, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Han, Gutheil, Hutchinson and LaChance. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paul K. J. Han, aGFucEBtbWMub3Jn; cGF1bC5oYW5AbmloLmdvdg==

Paul K. J. Han

Paul K. J. Han Caitlin Gutheil1

Caitlin Gutheil1