- 1Escuela de Psicología, Universidad Católica del Norte, Antofagasta, Chile

- 2Instituto de Alta Investigación, Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, Chile

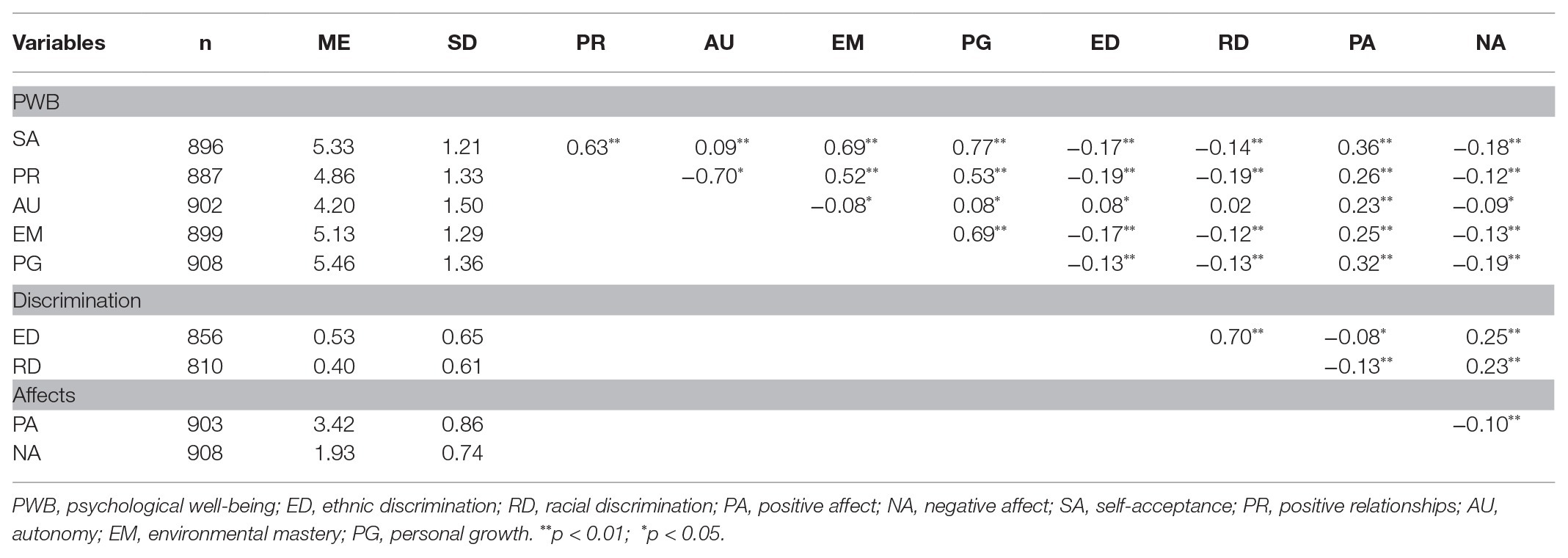

There is abundant empirical evidence on the negative effects of discrimination on psychological well-being. However, little research has focused on exploring the factors that can mitigate this effect. Within this framework, the present study examined the mediating role of positive and negative affects in the relationship between ethnic and racial discrimination and psychological well-being in the migrant population. About 919 Colombians, first-generation migrants, residing in Chile (Arica, Antofagasta, and Santiago) were evaluated, of which 50.5% were women, and the participants’ average age was 35 years (range: 18–65 years). Krieger’s discrimination questionnaires, Watson’s Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale were applied. The measurement models of each variable were estimated, and then the structural equation models were used. The results of the hypothesized multiple mediation model showed that the main mediator in the relationship between ethnic-racial discrimination and psychological well-being was positive affects over negative ones.

Introduction

Global processes on migration had implied that by mid-2019, about 272 million people would be living outside their countries of birth (Organización de Naciones Unidas, 2019). In South America, by 2019, the number of immigrants had reached almost 10 million, of which nearly a million were in Chile (Organización Internacional para las migraciones, 2020).

Even when migrants move to other countries seeking better living conditions and well-being, they often face different demanding and negative situations, such as living in overcrowded conditions, being victims of sexual or labor exploitation, or other types of violence, which negatively affects their quality of life, mental health, and well-being (Bobowik et al., 2015; Urzúa et al., 2015, 2016, 2017a,b; Bas-Sarmiento et al., 2017; Foo et al., 2018; Gatt et al., 2020).

Especially regarding well-being in the migrant population, evidence suggests that it can be affected by various variables at both individual and contextual levels, such as sex, educational level, age, length of residence, administrative situation, work situation, social support, acculturation strategies, language, positive social interaction, environment, and mental health (Liu et al., 2017; Urzúa et al., 2019a, 2020a; Rodríguez et al., 2020).

Besides these factors, a greater or smaller level of well-being may be conditioned by the individual’s level of adaptation in the host country, a process that is influenced by other factors such as ethnicity, language, religion, or an appearance different from that of the inhabitants of the host country (Martine et al., 2000). Low tolerance of these differences may produce phenomena such as discrimination and segregation by the host country (Tijoux et al., 2011).

Discrimination, a major negative social situation faced by migrants, is conceptualized as a different treatment toward a group with common characteristics or toward a person who belongs to such a group (Krieger, 2001). Discrimination can be exercised in several ways, with ethnic and racial discrimination being the most common among the migrant population. Racial discrimination refers to any differential treatment based on race or skin color. Ethnic discrimination involves situations of inequality and exclusion resulting from belonging to a specific ethnic group, a group that is formed by individuals who are perceived to have a common heritage with a common language, culture, and ancestry (Booth et al., 2011), and who are a minority in the host location.

Not only does discrimination have multiple negative effects on the population that suffers it, ranging from inequalities in access to socioeconomic goods and services and labor sources to access to health and education benefits, but also abundant evidence has revealed its negative effects on individuals’ physical and mental health and well-being (Harrell et al., 2003; Paradies, 2006; Gee et al., 2009; Pascoe and Smart, 2009; Williams and Mohammed, 2009; Bastos et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2015; Cuevas et al., 2016; Lahoz and Forns, 2016; Williams et al., 2019; Urzúa et al., 2019b, 2020a), especially stigmatized groups such as the migrant population (Finch et al., 2000; Bourguignon et al., 2006; Greene et al., 2006; Borrell et al., 2010; Zeiders et al., 2013; Schunck et al., 2015).

An inverse relationship between discrimination and well-being levels has been reported in studies of both the general population (Schmitt et al., 2014; Castaneda et al., 2015) and migrant population (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2006a,b; Mesch et al., 2008; Sevillano et al., 2013; Giuliani et al., 2018; Stevens and Thijs, 2018; Kader et al., 2020). However, studies on the factors that may moderate or mediate this relationship are still scarce. Factors such as personality traits (Xu and Chopik, 2020), self-esteem (Urzúa et al., 2018), identity (Jasperse et al., 2011; Liu and Zhao, 2016; Ferrari et al., 2017), sense of control (Jang et al., 2008), ethnic affirmation (Atari and Han, 2018), employability (Mera-Lemp et al., 2019), and group membership (Choi et al., 2020) could mediate the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being, or moderate it, in the case of group effectiveness (Bagci and Canpolat, 2020) or group membership (Shinwoo et al., 2020).

Given its close relationship to both discrimination and well-being, one factor that could play a mediating role is affect or emotional experience (Greenglass and Fiksenbaum, 2009; Pierce et al., 2018). Emotional experience has been divided into two dimensions: one positive and the other negative (Watson and Tellegen, 1985). Precedents suggest that affects can have a mediating role in the relationship between well-being and other factors, such as optimism (Vera-Villarroel et al., 2016). Although from a hedonic perspective, affects together with life satisfaction constitute the primary components of subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1999), there is evidence that the components of this structure behave independently and are moderately related (Busseri, 2018), which would also be expected for a measure of well-being, but from an eudaimonic perspective, as is psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989, 2014).

This research is framed in the context of south-south immigration, that is, South Americans migrating to South American countries, and specifically Colombians to Chile. Colombian migration mainly derives from the Pacific coast, i.e., people of African descent. This migration has resulted in situations of discrimination, either by the country of origin, linked to drug trafficking, drugs, and sex trade in the case of women, or by the color of the skin (Pavez, 2016; Tijoux, 2016; Gissi et al., 2019). Studies conducted in Chile show how discrimination has negatively affected both the mental health and the well-being of this population (Urzúa et al., 2018, 2019b; Mera-Lemp et al., 2020a), in addition to other factors that also affect well-being (Silva et al., 2016; Urzúa et al., 2019a, 2020b; Mera-Lemp et al., 2020b). A qualitative perspective about the effects of migration and racism on the Colombian population in Chile can be reviewed in Gii-Barbieri and Ghio-Suárez (2017) and Gii et al. (2019).

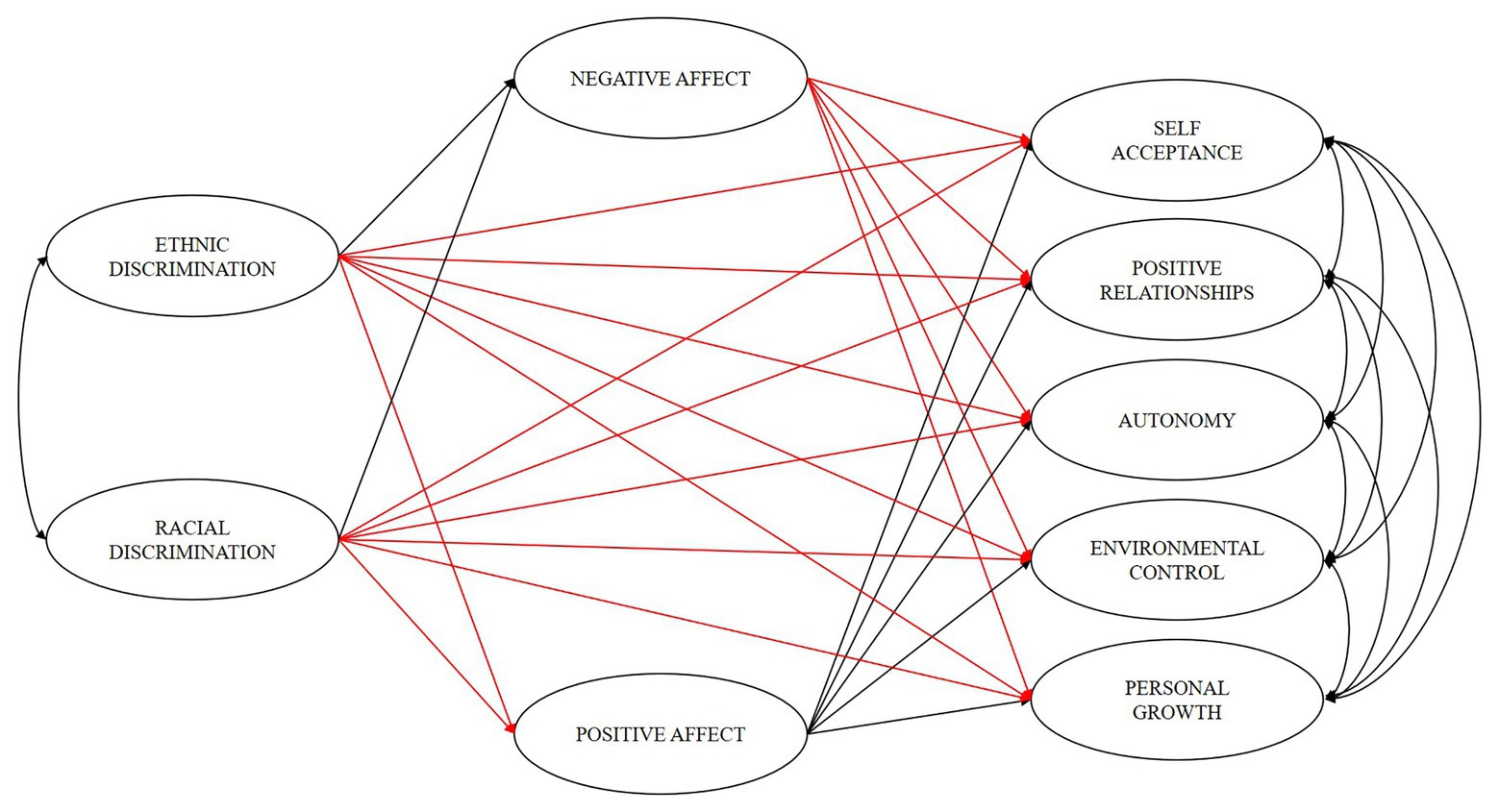

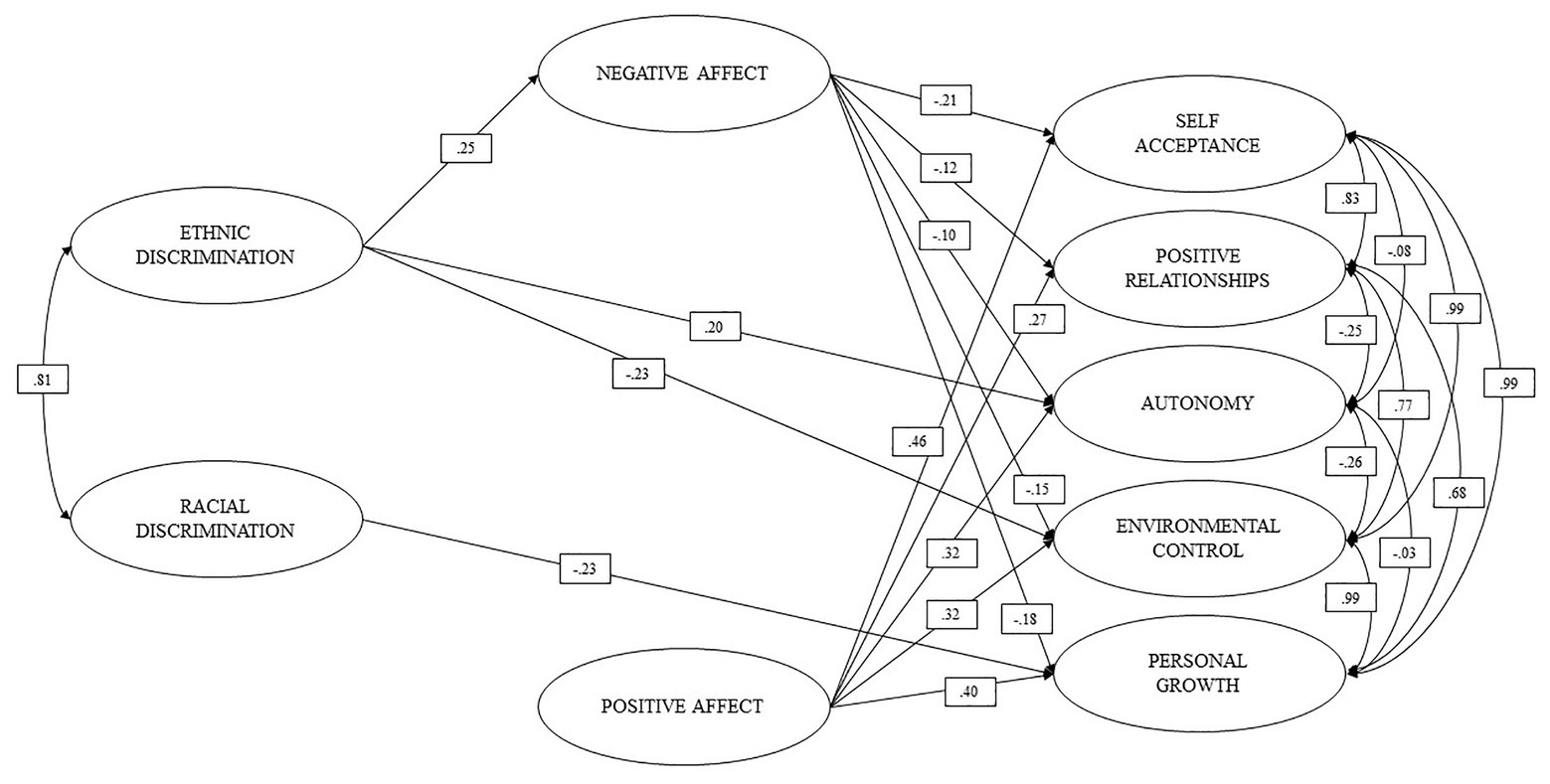

In this framework, this study examined the mediating role of positive and negative affects in the relationship between ethnic and racial discrimination and psychological well-being in Colombian migrants living in Chile. Based on the literature review, we hypothesized that the relationship between discrimination (racial and ethnic) and psychological well-being (self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, and personal growth) would be mediated by both positive and negative affects (Figure 1).

Materials and Methods

Participants

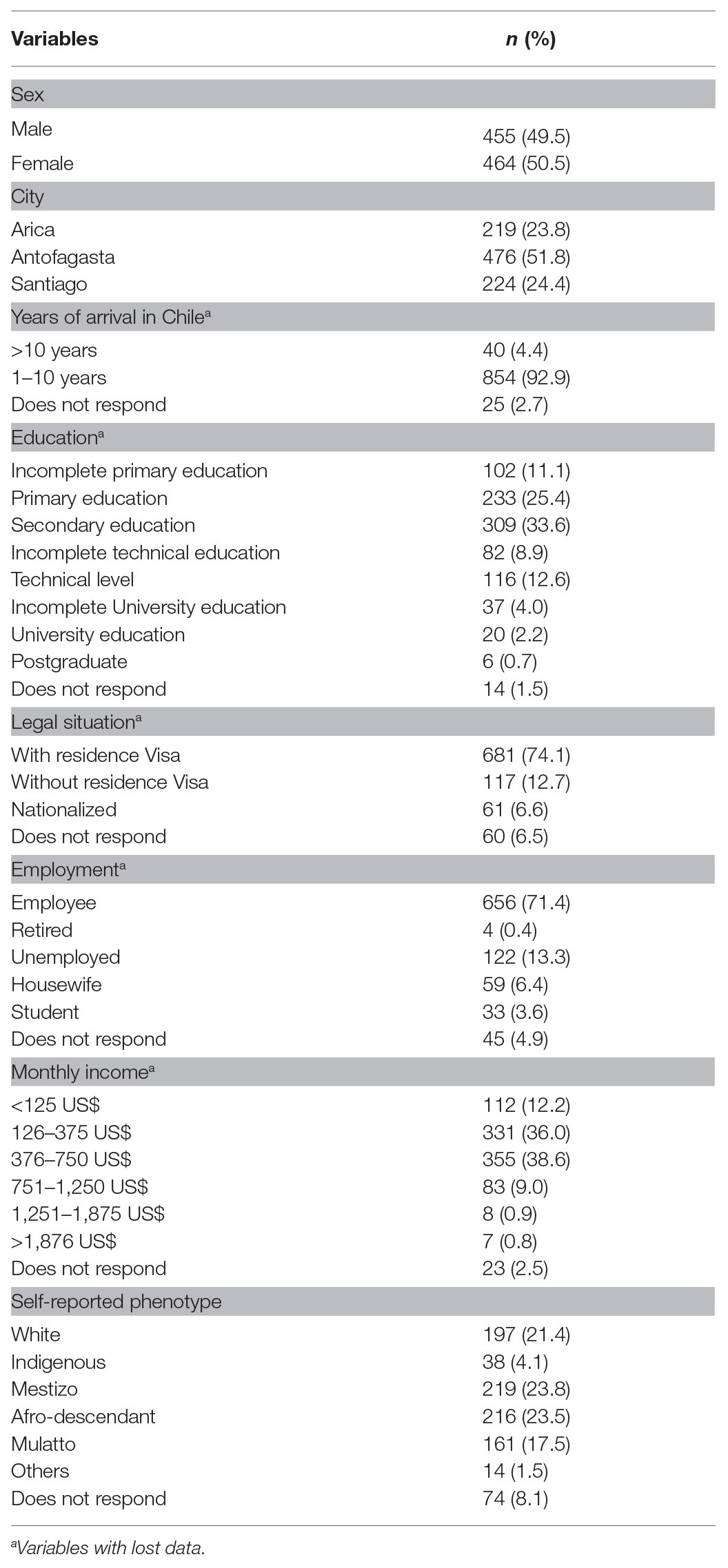

We surveyed a total of 919 migrants of Colombian nationality, who were living in three cities with the highest number of registered migrants in Chile: 476 (51.8%) in Antofagasta, 219 (23.8%) in Arica, and 224 (24.4%) in Santiago, at the time of the survey. It should be noted that the Metropolitan and the Antofagasta are the two regions with the highest number of visas issued by 2018 (Departamento de Extranjería y Migración, 2020). Regarding gender, 455 (49.5%) identified themselves as men, and 464 (50.5%) were women. Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 65 years (ME = 35.27; SD = 9.91). The characteristics of the participants can be observed in Table 1.

Instruments

Discrimination

We used Krieger et al. (2005) Discrimination Experience Scale to assess discrimination. This scale measures the participants’ perception of the various situations they have experienced related to discrimination in different contexts. To measure racial and ethnic discrimination separately, we asked the participants about their experiences where a treatment was perceived as discriminatory, whether due to skin color or nationality. Each scale is composed of nine items that ask if the person has felt discriminated, for example, when requiring attention in a restaurant or service, with answers ranging from never (0 points) to four or more times (3 points). In this application, an alpha of 0.88 was obtained for the ethnic discrimination scale and 0.90 for the racial discrimination scale.

Affect

It was evaluated using the PANAS, a self-report scale comprising two dimensions designed to measure positive and negative affects (Watson et al., 1988). The scale contains 20 items describing a series of feelings and emotions, and the participants indicate the extent to which they usually or regularly feel these affects with response options ranging between 1 (never) and 5 (very much). The present study used the Chilean version of Vera-Villarroel et al. (2019) and obtained Cronbach’s alphas of 0.87 for both positive and negative affects.

Psychological Well-Being

The Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scale of Ryff (1989) was used to measure psychological well-being (Díaz et al., 2006). This version includes 29 items under six dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. Responses are rated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree. There is evidence of its reliability and validity based on the internal structure of the measurement instrument (Chitgián-Urzúa et al., 2013; Vera-Villarroel et al., 2013). In this study (considering the results of the fit of the measurement model prior to the realization of the SEM), a reduced version of the scale was used. This short version contained 17 items under six dimensions proposed by Ryff. However, the “purpose” dimension was not used because it presented anomalous correlations (r > 1.0). In the present study, the scale presented Cronbach’s alphas of 0.79 for self-acceptance, 0.70 for positive relationships, 0.77 for autonomy, 0.62 for environmental mastery, and 0.81 for personal growth.

Procedures

This study is part of a larger project studying the effects of discrimination on health and well-being, which has been reviewed and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of the North. The initial participants were interviewed in person, mainly in public institutions such as the Catholic Migration Institute of Chile (INCAMI), Global Citizen-Jesuit Migration Services, Immigration Department, the Colombian Consulate, health centers, among others, after signing an informed consent. The data were coded and analyzed using SP-21 software.

Statistical Analysis

First, the measurement models of each scale were estimated using confirmatory factor analysis. Second, a structural equation model (SEM) was used to test whether ethnic discrimination (ED) and racial discrimination (RD) exerted an inverse effect on migrants’ psychological well-being. Subsequently, the hypothesized multiple mediation model was evaluated, where the mediating effect of positive and negative affects was estimated on the relationship between ethnic and racial discrimination (as a criterion variable) and self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, and personal growth (as response variables). The indirect effects of the mediation model were aeed following the recommendations of Stride et al. (2017).

Structural equation models were performed using Mplus 8.2 software (Muthén and Muthén, 2010), using the weighted least squares (WLSMV) robust estimation method, which is robust for non-normal ordinal variables (Beauducel and Herzberg, 2006). Goodness-of-fit of all models was estimated using Chi-square values (χ2), the approximation mean square error (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker Lewis index (TLI). According to the recommended literature standards (e.g., Schreiber, 2017), the RMSEA ≤ 0.08, CFI ≥ 0.95, and TLI ≥ 0.95 values are considered adequate and indicative of a good fit. Age, sex, city of residence, and self-reported phenotype were controlled for in all analyses. No significant differences were found in the levels of perceived well-being given the voluntary or forced nature of migration, so the analyses did not consider this variable as a control.

Results

Measurement Models

Table 1 shows the goodness-of-fit indices of the estimated measurement models. Both ED and RD presented indicators outside the recommended standards (i.e., RMSEA > 0.08). The items that could be causing the poor fit were examined, and it was detected that the items “On being hired or getting a job” and “On the job” could be sharing more variance than was directly explained by the common factor (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014) because both items indicated the work setting. For this reason, we evaluated both the measurement models by extracting the reagent “Upon being hired or obtaining a job,” leaving the reagent “At work” only. With this modification in both scales, the adjustment indicators were close to those recommended by the literature (ED: RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RD: RMSEA = 0.09; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; Table 2).

Structural Equation Model

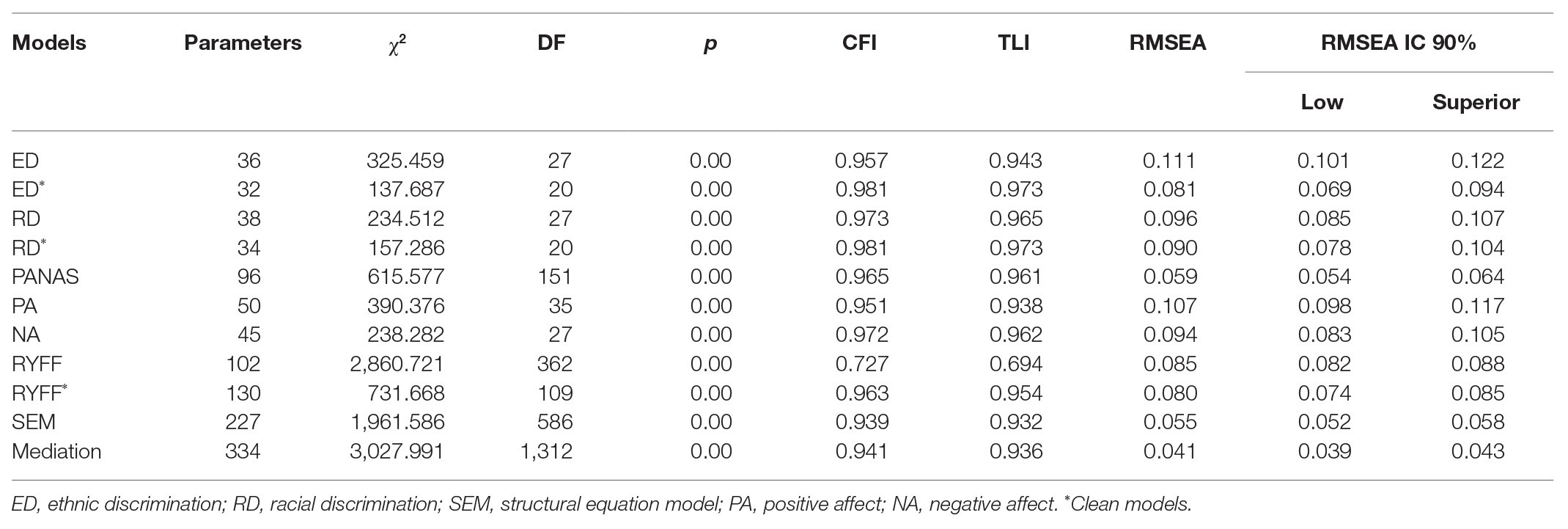

Based on the adjusted measurement models, a structural equation model was used to examine the effects of ED and RD on the components of psychological well-being (self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, and personal growth). In regard to the control variables, we could only observe significant effects of self-reported phenotype on Personal Growth (b = 0.10), and the city of residence on Self-acceptance (b = 0.09), Positive Relationships (b = 0.19), and autonomy (b = −0.12). Age and sex did not present significant effects on the dimensions of psychological well-being.

As shown in Figure 2, ED had a slight positive effect (b > 0.10; Cohen, 1988) on autonomy, a small negative effect on environmental mastery, and no significant effect on self-acceptance, positive relationships, and personal growth.

On the other hand, RD exerted a slight negative effect on positive relationships (b = −0.251; p < 0.00) and a moderate negative effect (b > 0.30; Cohen, 1988) on personal growth (b = −0.321; p < 0.00). RD did not have significant effects on self-acceptance, autonomy, and environmental mastery. The structural model presented goodness-of-fit close to the criteria accepted in the literature (RMSEA = 0.055; CFI = 0.939; TLI = 0.932).

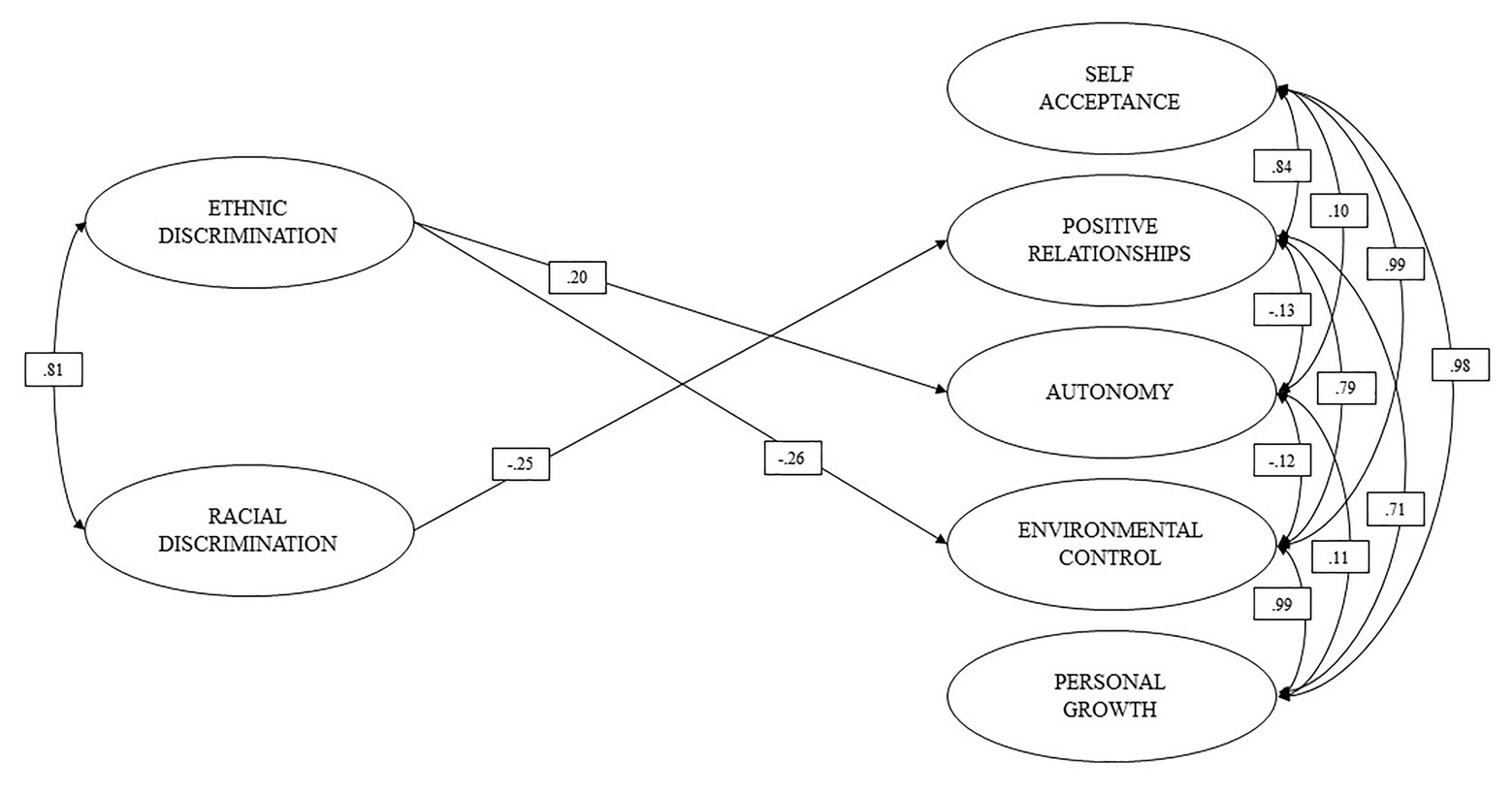

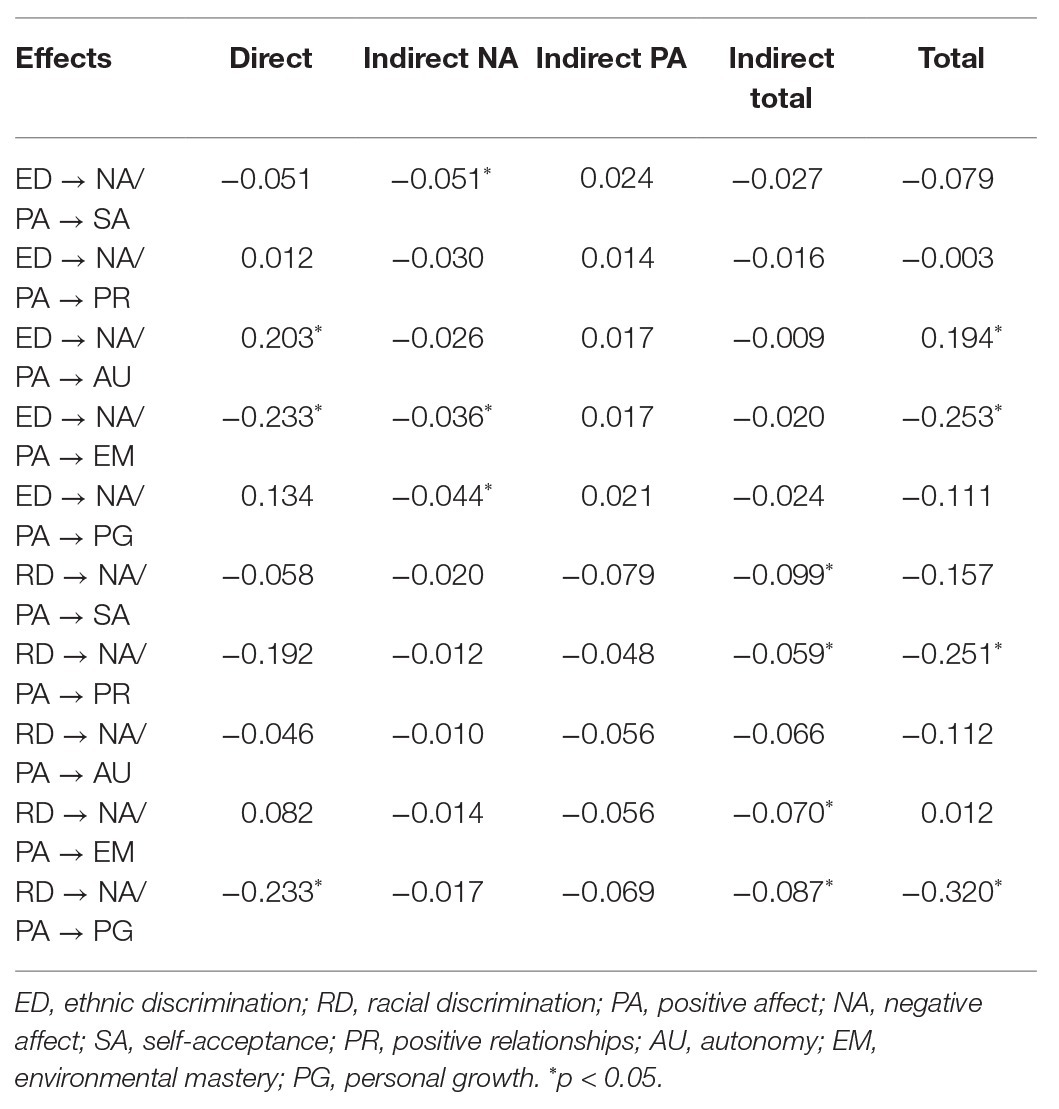

Once the relationship between ethnic-racial discrimination and psychological well-being was examined (Table 3), the model of multiple mediations was evaluated. In this model, the positive and negative effects on migrants were included as parallel mediators of the inverse effect that ED and RD would have on self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, mastery of the environment, and personal growth. In regard to the control variables, we could only observe significant effects of sex on positive affects (b = −0.09), self-reported phenotype on Personal Growth (b = 0.09), and city of residence on positive affects (b = 0.21), Positive Relationships (b = 0.13) and autonomy (b = −0.19). Age did not present significant effects on positive/negative affects, or on dimensions of psychological well-being.

Figure 3 shows the significant direct effects of the mediation model. As can be seen, ethnic discrimination presented positive direct effects of small magnitude on negative affects and autonomy, and a negative effect on mastery of the environment. No significant effects were observed on the other variables. Regarding ethnic discrimination, only small and significant negative direct effects can be observed on personal growth, nor were there significant effects observed on the other variables. Furthermore, in Figure 3, it can be seen that negative affects exert small negative direct effects on self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, mastery of the environment, and personal growth, while positive affects present positive direct effects of moderate magnitude on self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, control of the environment, and personal growth.

As shown in Table 4, negative affect only exerted indirect mediation effects (Zhao et al., 2010) on the relationship between ED and self-acceptance and personal growth, and complementary effects (Zhao et al., 2010) on the relationship between ED and environmental mastery. Positive affect did not have significant mediation effects. In addition, total indirect effects can be observed on the relationship between RD and self-acceptance, positive relationships, environmental mastery, and personal growth.

The hypothesized mediation model was adequately adjusted to the data (RMSEA = 0.041; CFI = 0.941; TLI = 0.936); therefore, it was a good representation of the observed relationships.

Discussion

This study hypothesized that the relationship between discrimination (racial and ethnic) and psychological well-being (self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, and personal growth) would be mediated by both positive and negative affects, which was partially proven.

First, after controlling for sex, age, city, and self-reported phenotype, the data provide evidence for the fact that discrimination had an effect on well-being. Particularly, ethnic discrimination affected environmental mastery, and racial discrimination affected positive relationships. Concurrently, a slight positive effect of ethnic discrimination on autonomy was found.

The inverse relationship of xenophobia with the environmental mastery is evident, since the migrant, perceiving unequal treatment because one belongs to a specific group (in this case, being Colombian) or according to what one believes or thinks one deserves, diminishes their sense of control over the world and the ability to influence the context around them. Similarly, feeling discriminated against because of the color of one’s skin has a negative effect on the acquisition of stable social relationships and trustworthy friends, especially in a highly racist context, such as Chile, where about one in three people consider themselves whiter than other people in Latin American countries (Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos, 2017).

Despite this, feeling discriminated against due to ethnic origin has a direct relationship with the domain of autonomy. This implies that, in some way, discrimination has generated a higher level of autonomy, which allows migrants to better resist social pressure and sustain their individuality in different social contexts, where both self-esteem and ethnic identity play an important role (Urzúa et al., 2018).

Second, regarding the incorporation of affects, whether positive or negative, in the relationship between discrimination and the domains of psychological well-being, there is evidence of a positive relationship between positive affects and well-being and an inverse relationship between negative affects and well-being, in a similar way to the relationship between affections and hedonic well-being. It should be noted that when the affects are introduced into the model, the relationships between ED and autonomy, and environmental control are maintained; however, the relationship between RD and positive relationships disappears, and the relationship with personal growth appears. The latter seems to provide evidence on the effect that the presence of both affects may have in the relationship of racial discrimination on personal growth.

However, we also found that affects effectively exercised a mediating role. Negative affect only exerted indirect mediation effects on the relationship between ED and self-acceptance and personal growth, and complementary effects on the relationship between ED and environmental mastery.

Complementary mediation occurs when the mediated effect (a × b) and the direct effect (c) exist, and point in the same direction (Zhao et al., 2010). This means that ethnic discrimination has negative effects on the environmental mastery, and in parallel, negative affects also have negative effects on this domain. This means that migrants who perceive greater discrimination due to their country of origin are affected in their abilities to be able to deploy and modify the context and environment for their benefit.

We have also found that the presence of both affects had a mediating effect on the relationship between RD and self-acceptance, positive relationships, environmental mastery, and personal growth. This is relevant since, although specific indirect effects can be observed in the multiple mediation model, it is very difficult for these effects to work separately in real life. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the phenomenon in a more complete and holistic way considering the inclusion of both negative and positive affects simultaneously. The results indicate that positive/negative affects as a whole play a fundamental role in explaining the low levels of psychological well-being caused by racial discrimination. These results open the need to deepen a possible line of study that allows us to continue enhancing our understanding of the effect of affects on the discrimination-well-being relationship, which could be to consider the variables of positive or negative affect not as independent variables but as a single variable elaborated based on the combination of both. Pierce et al. (2018) research could be considered as a precedent. They analyzed the mediating effect of affect on ethnic and racial minorities in African American students in the United States, showing that affect mediated well-being, but specifically, the combination of positive and negative affect, where high positive affect combined with low negative affect was associated with improved well-being. Similarly, it would be interesting to explore how this relationship might be affected by a possible moderating variable, such as sex, given that women’s stronger positive emotions have been reported to balance their greater negative affects (Fujita et al., 1991).

Therefore, the discussion focuses on an aspect that deserves our attention. There would be a differentiated effect of the interaction between the types of affects and the types of discrimination, given that the positive affects only presented the capacity to mediate the effect of racial discrimination on some domains of well-being, while the negative affects mediated the effects of ethnic discrimination on well-being only. It was difficult to find literature or previous research that contribute to the discussion about the relationship between the origin of discrimination (by nationality or skin color) and the affects, whether positive or negative. However, undoubtedly, by behaving independently, these would play a different role according to the origin of the discrimination, which opens an interesting line to explore. Xu et al. (2015) have also reported that attentional bias influenced affect and, therefore, the well-being (attention bias to positive information favors positive affects, and the positive affect could reduce the negative cognitive bias induced by negative affect and, therefore, would contribute to better psychological well-being). Racial discrimination would be linked to an attentional bias centered on positive affects, while xenophobia would activate activation bias oriented toward negative affects, thus, opening an interesting line of research.

Taking the above into consideration, and to better understand the phenomenon, by including in the model both positive and negative affects experienced by migrants, it was found that ethnic discrimination (because it comes from a particular country) causes negative affects, and these affects, in turn, cause lower levels of psychological well-being in all its dimensions. In other words, negative affects have a strong influence on the effect that ethnic discrimination has on the psychological distress of migrants. On the other hand, in the case of positive affects, these were not influenced by discrimination or by coming from a particular country, or by having a particular skin color, so this does not influence the relationship to a great extent between ethnic/racial discrimination and dimensions of psychological well-being. However, this does not mean that positive affects have no effects on psychological well-being, quite the contrary. The results show that the positive affects of migrants cause higher levels of psychological well-being for them.

Despite the limitations of this study, which are typical of a cross-sectional study in which the effect of affects over time cannot be evaluated and is performed in only one ethnic group, it is a contribution since much of the evidence found on well-being is based on measuring hedonic well-being (subjective well-being) and not eudemonic well-being (psychological well-being). It also opens new lines of discussion on the differential impact that discrimination due to different causes can have, while reinforcing the evidence of the independent effect of affects, whether negative or positive, on psychological well-being. This merits its inclusion as a variable in the development of intervention programs at the individual level, favoring the psychological well-being of the migrant population.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité de Ética Científica de la Universidad Católica del Norte. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AU and AC made substantial contributions to the conception and design, and acquisition of data. AU and DH performed the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding

This study was supported by “Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico—FONDECYT” of the project grant no 1180315.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Atari, R., and Han, S. (2018). Perceived discrimination, ethnic identity, and psychological well-being among Arab Americans. Couns. Psychol. 46, 899–921. doi: 10.1177/0011000018809889

Bagci, S. C., and Canpolat, E. (2020). Group efficacy as a moderator on the aociations between perceived discrimination, acculturation orientations, and psychological well-being. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 30, 45–58. doi: 10.1002/casp.2421

Bas-Sarmiento, P., Saucedo-Moreno, M. J., Fernández-Gutiérrez, M., and Poza-Méndez, M. (2017). Mental health in immigrants versus native population: a systematic review of the literature. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 31, 111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.014

Bastos, J., Barros, A., Celeste, R., Paradies, Y., and Faerstein, E. (2014). Age, cla and race discrimination: their interactions and aociations with mental health among Brazilian university students. Cad. Saúde Pública 30, 175–186. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00163812

Beauducel, A., and Herzberg, P. (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Struct. Equ. Model. 13, 186–203. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2

Bobowik, M., Basabe, N., and y Páez, D. (2015). The bright side of migration: hedonic, psychological, and social well-being in inmigrant in Spain. Soc. Sci. Res., 51, 189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.research.2014.09.011

Booth, A. L., Leigh, A., and Varganova, E. (2011). Does ethnic discrimination vary acro minority groups? Evidence from a field experiment*. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 74, 547–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.2011.00664.x

Borrell, C., Muntaner, C., Gil-González, D., Artazcoz, L., Rodríguez-Sanz, M., Rohlfs, I., et al. (2010). Perceived discrimination and health by gender, social cla, and country of birth in a Southern European country. Prev. Med. 50, 86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.016

Bourguignon, D., Seron, E., Yzerbyt, V., and Herman, G. (2006). Perceived group and personal discrimination: differential effects on personal self-esteem. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 36, 773–789. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.326

Bueri, M. A. (2018). Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the aociations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 122, 68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.003

Castaneda, A. E., Rask, S., Koponen, P., Suvisaari, J., Koskinen, S., Härkänen, T., et al. (2015). The aociation between discrimination and psychological and social well-being. Psychol. Dev. Soc. 27, 270–292. doi: 10.1177/2F0971333615594054

Chitgian-Urzúa, V., Urzúa, A., and Vera-Villarroel, P. (2013). Análisis Preliminar de las Escalas de Bienestar Psicológico en Población Chilena. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica 22, 5–14.

Choi, S., Weng, S., Park, H., and Kim, Y. (2020). Effects of Asian immigrants’ group membership in the aociation between perceived racial discrimination and psychological well-being: the interplay of immigrants’ generational status, age, and ethnic subgroup. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 29, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2020.1712569

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Aociates, Publishers.

Cuevas, A. G., Dawson, B. A., and Williams, D. R. (2016). Race and skin color in latino health: an analytic review. Am. J. Public Health 106, 2131–2136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2016.303452

Departamento de Extranjería y Migración (2020). Estadísticas Migratorias 2018. Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, Gobierno de Chile. Available at: https://www.extranjeria.gob.cl/estadisticas-migratorias/

Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., and Valle, C. y Van Dierendonck, D. (2006). Adaptación Española de las escalas de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema, 18, 572–577.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., and Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: three decades of progre. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Ferrari, L., Rosnati, R., Canzi, E., Ballerini, A., and Ranieri, S. (2017). How international transracial adoptees and immigrants cope with discrimination? The moderating role of ethnic identity in the relation between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 27, 437–449. doi: 10.1002/casp.2325

Finch, B. K., Kolody, B., and Vega, W. A. (2000). Perceived discrimination and depreion among Mexican-origin adults in California. J. Health Soc. Behav. 41, 295–313. doi: 10.1177/2F0739986301234004

Foo, S., Tam, W., Ho, C., Tran, B., Nguyen, L., McIntyre, R., et al. (2018). Prevalence of depreion among migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:1986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091986

Fujita, F., Diener, E., and Sandvik, E. (1991). Gender differences in negative affect and well-being: the case for emotional intensity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 427–434. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.427

Gatt, J. M., Alexander, R., Emond, A., Foster, K., Hadfield, K., Mason-Jones, A., et al. (2020). Trauma, resilience, and mental health in migrant and non-migrant youth: an international cro-sectional study acro six countries. Front. Psychiatry 10:997. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00997

Gee, G. C., Ro, A., Shariff-Marco, S., and Chae, D. (2009). Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, aement, and directions for future research. Epidemiol. Rev. 31, 130–151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp009

Gii-Barbieri, E., and Ghio-Suárez, G. (2017). Integración y exclusión de inmigrantes colombianos recientes en Santiago de Chile: estrato socioeconómico y “raza” en la geocultura del sistema-mundo. Papeles de población 23, 151–179. doi: 10.22185/24487147.2017.93.025

Gissi, E., Pinto, C., and Rodríguez, F. (2019). Inmigración reciente de colombianos y colombianas en Chile. Sociedades plurales, imaginarios sociales y estereotipos. Estudios Atacameños 62, 127–141. doi: 10.22199/in.0718-1043-2019-0011

Giuliani, C., Tagliabue, S., and Regalia, C. (2018). Psychological well-being, multiple identities, and discrimination among first and second generation immigrant Muslims. Eur. J. Psychol. 14, 66–87. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v14i1.1434

Greene, M. L., Way, N., and Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Dev. Psychol. 42, 218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218

Greengla, E. R., and Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being. Eur. Psychol. 14, 29–39. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29

Harrell, J., Hall, S., and Taliaferro, J. (2003). Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: an aement of the evidence. Am. J. Public Health 93, 243–248. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.243

Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (2017). Informe Anual. Situación de los Derechos Humanos en Chile. Available at: https://www.indh.cl/bb/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01_Informe-Anual-2017.pdf (Accessed June 24, 2020).

Jang, Y., Chiriboga, D. A., and Small, B. J. (2008). Perceived discrimination and psychological well-being: the mediating and moderating role of sense of control. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 66, 213–227. doi: 10.2190/ag.66.3.c

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., Jaakkola, M., and Reuter, A. (2006a). Perceived discrimination, social support network and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. J. Cro-Cult. Psychol. 3, 293–311. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286925

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., and Perhoniemi, R. (2006b). Perceived discrimination and well-being: a victim study of different inmigrant groups. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 16, 267–284. doi: 10.1002/casp.865

Jasperse, M., Ward, C., and Jose, P. E. (2011). Identity, perceived religious discrimination, and psychological well-being in Muslim immigrant women. Appl. Psychol. 61, 250–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00467.x

Kader, F., Bazzi, L., Khoja, L., Haan, F., and de Leon, C. M. (2020). Perceived discrimination and mental well-being in Arab Americans from Southeast Michigan: a cro-sectional study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 7, 436–445. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00672-y

Krieger, N. (2001). A gloary for social epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 55, 693–700. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.10.693

Krieger, N., Smith, K., Naishadham, D., Hartman, C., and Barbeau, E. (2005). Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 61, 1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006

Lahoz, S., and Forns, M. (2016). Discriminación percibida, afrontamiento y salud mental en migrantes peruanos en Santiago de Chile. Psicoperspectivas 15, 157–168. doi: 10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol15-Iue1-fulltext-613

Lewis, T. T., Cogburn, C. D., and Williams, D. R. (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging iues. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 11, 407–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728

Liu, Y., Zhang, F., Wu, F., Liu, Y., and Li, Z. (2017). The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities 60, 333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2016.10.008

Liu, X., and Zhao, J. (2016). Chinese migrant adolescents’ perceived discrimination and psychological well-being: the moderating roles of group identity and the type of school. PLoS One 11:e0146559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146559

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., and Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología 30, 1151–1169. doi: 10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Martine, G. R., Hakkert, R., and Guzmán, J. M. (2000). Aspectos sociales de la migración internacional: consideraciones preliminares. Notas de población 73, 163–193.

Mera-Lemp, M., Bilbao, M., and Martínez-Zelaya, G. (2020a). Discriminación, aculturación y bienestar psicológico en inmigrantes latinoamericanos en Chile. Revista de Psicología 29, 1–15. doi: 10.5354/0719-0581.2020.55711

Mera-Lemp, M. J., Martínez-Zelaya, G., Orellana, A., and Smith-Castro, V. (2020b). Acculturation orientations, acculturative stre and psychological well-being on Latin American immigrants settled in Santiago, Chile. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 23, 216–230. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2020.23.1.11

Mera-Lemp, M. J., Ramírez-Vielma, R., Bilbao, M. D. I. Á., and Nazar, G. (2019). La Discriminación Percibida, la Empleabilidad y el Bienestar Psicológico en los Inmigrantes Latinoamericanos en Chile [Perceived discrimination, employability, and psychological well-being among Latin American immigrants in Chile]. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 35, 227–236. doi: 10.5093/jwop2019a24

Mesch, G. S., Turjeman, H., and Fishman, G. J. (2008). Perceived discrimination and the well-being of immigrant adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 37, 592–604. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9210-6

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user's guide. 6th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Organización de Naciones Unidas (2019). International Migration. Departamento de asuntos económicos y sociales. División de población. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.as (Accessed June 24, 2020).

Organización Internacional para las migraciones (2020). Datos migratorios en América del Sur. Oficina Regional de la OIM para América del Sur. Centro de Análisis de Datos Mundiales sobre la Migración (GMDAC) de la OIM. Portal de datos mundiales sobre la migración. Available at: https://migrationdataportal.org/es/regional-data-overview/datos-migratorios-en-america-del-sur#tendencias-actuales (Accessed June 25, 2020).

Paradies, Y. (2006). A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 35, 888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056

Pascoe, E. A., and Smart, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 135, 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059

Pavez, J. (2016). “Racismo de clase y racismo de género: “mujer chilena”, “mestizo blanquecino” y “negra colombiana” en la ideología nacional chilena” in Racismo en Chile. La piel como marca de la inmigración. ed. M. E. Tijoux (Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria).

Pierce, J., Zhdanova, L., and Lucas, T. (2018). Positive and negative affectivity, stre, and well-being in African-Americans: Initial demonstration of a polynomial regreion and response surface methodology approach. Psychol. Health 33, 445–464. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1368510

Rodríguez, D. X., Hill, J., and McDaniel, P. N. (2020). A scoping review of literature about mental health and well-being among immigrant communities in the United States. Health Promot. Pract. 152483992094251. doi: 10.1177/1524839920942511 [Epub ahead of print]

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happine is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 83, 10–28. doi: 10.1159/000353263

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., and García, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 140, 921–948. doi: 10.1037/a0035754

Schreiber, J. B. (2017). Update to core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 13, 634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.06.006

Schunck, R., Rei, K., and Razum, O. (2015). Pathways between perceived discrimination and health among immigrants: evidence from a large national panel survey in Germany. Ethn. Health 20, 493–510. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.932756

Sevillano, V., Basabe, N., Bobowik, M., and Aierdi, X. (2013). Health-related quality of life, ethnicity and perceived discrimination among immigrants and natives in Spain. Ethn. Health 19, 178–197. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.797569

Shinwoo, C., Weng, S., Park, H., and Kim, Y. (2020). Effects of Asian immigrants’ group membership in the aociation between perceived racial discrimination and psychological well-being: the interplay of immigrants’ generational status, age, and ethnic subgroup. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 29, 114–135. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2020.1712569

Silva, S. J., Urzúa, M. A., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Lufin, M., and Irarrazaval, M. (2016). Bienestar psicológico y estrategias de aculturación en inmigrantes afrocolombianos en el norte de Chile. Interciencia 41, 804–811.

Stevens, G. W. J. M., and Thijs, J. (2018). Perceived group discrimination and psychological well-being in ethnic minority adolescents. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 48, 559–570. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12547

Stride, C., Gardner, S., Catley, N., and Thomas, F. (2017). Mplus code for mediation, moderation and moderated mediation models (1 to 80), 1–767. Available at: http://www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/mplusmedmod.htm (Accessed May 01, 2020).

Tijoux, M. E. (2016). Racismo en Chile. La piel como marca de la inmigración. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria.

Tijoux, M., Tarazona, M., Madriaga, L., and Reyes, P. (2011). Transformaciones de la vida cotidiana de los inmigrantes peruanos que habitan en Santiago de Chile: Relaciones familiares e invención de existencias transnacionales. Cuadernos de Investigación, 15. Available at: http://www.socialjesuitas.es/documentos/download/15-cuadernos-de-investigacion/61-c15-transformaciones-vida-cotidiana-peruanos

Urzúa, A., Caqueo-Urízar, A., and Aragón, D. (2020a). Prevalencia de sintomatología ansiosa y depresiva en migrantes colombianos en Chile. Revista Médica de Chile 148, 1271–1278.

Urzúa, A., Delgado, E., Rojas, M., and Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2017a). Social well being among Colombian and Peruvian immigrants in Northern Chile. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 19, 1140–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0416-0

Urzúa, A., Ferrer, R., Canales, V., Nuñez, D., Ravanal, I., and Tabilo, B. (2017b). The influence of acculturation strategies in quality of life by immigrants in Northern Chile. Qual. Life Res. 26, 717–726. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1470-8

Urzúa, A., Ferrer, R., Godoy, N., Leppes, F., Trujillo, C., Osorio, C., et al. (2018). The mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological wellbeing in immigrants. PLoS One 13:e0198413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198413

Urzúa, A., Ferrer, R., Olivares, E., Rojas, J., and Ramirez, R. (2019b). El efecto de la discriminación racial y étnica sobre la autoestima individual y colectiva según el fenotipo auto-reportado en migrantes colombianos en Chile. Terapia Psicológica 37, 225–240. doi: 10.4067/S0718-48082019000300225

Urzúa, A., Heredia, O., and Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2016). Salud mental y Estrés por aculturación en inmigrantes sudamericanos en el norte de Chile. Rev. Med. Chil. 144, 563–570. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872016000500002

Urzúa, A., Leiva, J., and Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2020b). Effect of positive social interaction on the psychological well-being in South American immigrants in Chile. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 21, 295–306. doi: 10.1007/s12134-019-00731-7

Urzúa, A., Leiva-Gutierrez, J., Caqueo-Urizar, A., and Vera-Villarroel, P. (2019a). Rooting mediates the effect of stre by acculturation on the psychological well-being of immigrants living in Chile. PLoS One 14:e0219485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219485

Urzúa, A., Vega, M., Jara, A., Trujillo, S., Muñoz, R., and Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2015). Calidad de vida percibida en Inmigrantes Sudamericanos en el norte de Chile. Terapia Psicológica 33, 139–156. doi: 10.4067/S0718-48082015000200008

Vera-Villarroel, P., Celis-Atenas, K., Urzúa, A., Silva, J., Contreras, D., and Lillo, S. (2016). Los afectos como mediadores de la relación optimismo y bienestar. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica. XXV, 195–202.

Vera-Villarroel, P., Urzúa, A., Silva, J. R., Pavez, P., and Celis-Atenas, K. (2013). Escala de Bienestar de Ryff: Análisis Comparativo de Los Modelos Teóricos en Distintos Grupos de Edad. Psicol-Reflex. Crít. 26, 106–112. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722013000100012

Vera-Villarroel, P., Urzúa, A., Zychc, I., Celis, K., Silva, J., Contreras, D., et al. (2019). Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): psychometric properties and discriminative capacity in several Chilean samples. Eval. Health Prof. 42, 473–497. doi: 10.1177/016327871774534

Watson, D., Clark, L., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.106

Watson, D., and Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychol. Bull. 98, 219–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.21

Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., and Davis, B. A. (2019). Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 40, 105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

Williams, D., and Mohammed, S. (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 32, 20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

Xu, Y. E., and Chopik, W. J. (2020). Identifying moderators in the link between workplace discrimination and health/well-being. Front. Psychol. 11:458. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00458

Xu, Y., Yu, Y., Xie, Y., Peng, L., Liu, B., Xie, J., et al. (2015). Positive affect promotes well-being and alleviates depreion: the mediating effect of attentional bias. Psychiatry Res. 228, 482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.06.011

Zeiders, K. H., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., and Derlan, C. L. (2013). Trajectories of depreive symptoms and self-esteem in Latino youths: examining the role of gender and perceived discrimination. Dev. Psychol. 49, 951–963. doi: 10.1037/a0028866

Keywords: migrant, well-being, positive affect, negative affect, discrimination, racism

Citation: Urzúa A, Henríquez D and Caqueo-Urízar A (2020) Affects as Mediators of the Negative Effects of Discrimination on Psychological Well-Being in the Migrant Population. Front. Psychol. 11:602537. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.602537

Edited by:

Dario Paez, University of the Basque Country, SpainReviewed by:

María José Mera-Lemp, Alberto Hurtado University, ChileGonzalo Martínez-Zelaya, Viña del Mar University, Chile

Copyright © 2020 Urzúa, Henríquez and Caqueo-Urízar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alfonso Urzúa, YWx1cnp1YUB1Y24uY2w=

Alfonso Urzúa

Alfonso Urzúa Diego Henríquez

Diego Henríquez Alejandra Caqueo-Urízar2

Alejandra Caqueo-Urízar2