- 1Centre for Human Factors and Sociotechnical Systems, University of the Sunshine Coast, Sippy Downs, QLD, Australia

- 2St Kilda Football Club, St Kilda, VIC, Australia

The suspension of major sporting competitions due to the global COVID-19 pandemic had a substantial negative impact on the sporting industry. As such, a successful and sustainable return to sport will require extensive modifications to the current operations of sporting organizations. In this article we argue that methods from the realm of sociotechnical systems (STS) theory are highly suited for this purpose. The aim of the study was to use such methods to develop a model of an Australian Football League (AFL) club’s football department. The intention was to identify potential modifications to the club’s operations to support a return to competition following the COVID-19 crisis. Subject Matter Experts from an AFL club participated in three online workshops to develop Work Domain Analysis and Social Organization and Cooperation Analysis models. The results demonstrated the inherent complexity of an AFL football department via numerous interacting values, functions and processes influencing the goals of the system. Conflicts within the system were captured via the modeling and included pursing goals that may not fully reflect the state of the system, a lack of formal assessment of core values, overlapping functions and objects, and an overemphasis on specialized roles. The current analysis has highlighted potential areas for modification in the football department, and sports performance departments in general.

Introduction

On the 11th March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic (World Health Organisation, 2020). In the days and weeks that followed, the global sporting industry was brought to a sudden halt (Evans et al., 2020; Parnell et al., 2020; Toresdahl and Asif, 2020). This began with the National Basketball Association (NBA) in the United States suspending competition after a player tested positive for COVID-19. This was quickly followed by the suspension of all other major sporting competitions, including the world’s biggest sporting event, the Olympic Games, to be held in Tokyo in July 2020 (Sato et al., 2020). To put the situation in context, the scheduling of the Olympic Games has only previously been interrupted due to the second World War. From March 2020 onward, elite sport worldwide entered largely unchartered territory.

The public health crisis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has been extensively documented by the media, governments, WHO, and via academic commentary and editorials (Heymann and Shindo, 2020; World Health Organisation, 2020). In addition to the public health crisis, is the impending financial crisis brought about by the lock down of entire countries and industries (Goodell, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). While the overall financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet clear (Zhang et al., 2020), short term financial impacts are already being realized within the sporting industry (Evans et al., 2020). As a result of the suspension of play, sporting organizations have been unable to generate revenue from media, memberships, merchandise and ticket sales (Evans et al., 2020). This has led to a requirement to reduce spending, which has contributed to mass unemployment within the sporting industry (Evans et al., 2020). It is anticipated that the public health and economic impacts of the pandemic will be ongoing and will impact sport in both the short and long term (Goodell, 2020; Heymann and Shindo, 2020). As such, the sporting industry will be required to adapt and potentially to re-invent itself upon the resumption of competitive sport (Evans et al., 2020). In the short term, for example, a safe and successful return to play will require significant modifications to current practices such as coaching, training, and injury prevention management. Moreover, severe financial constraints will require sports organizations to revisit the structures and processes currently used to optimize performance. Sporting organizations will need resilience to cope with potential intermittent suspensions in the event of future global pandemics. A successful return to competition will require agility, innovation, and ultimately substantial modifications to current operations to ensure the sustainability of sporting organizations.

In order to understand the inherent complexity of the COVID-19 crisis for sporting organizations, appropriate approaches are necessary. There is a growing body of research applying complexity and systems thinking-based methods to understand and optimize sports systems (Bittencourt et al., 2016; McLean et al., 2017, 2019a; Hulme et al., 2019; Salmon and McLean, 2019; Salmon et al., 2021). Such methods are useful as they can be used to describe sports organizations, their key functions, and the factors that influence performance at the athlete, the team, and at the organizational level. Sociotechnical systems (STS) theory (Clegg, 2000; Read et al., 2018) is one such approach that is used to optimize work systems. It was developed during a program of research undertaken at the Tavistock Institute that focused on the disruptive impacts of new technologies on human work (Trist and Bamforth, 1951; Eason, 2014). The approach encapsulates a focus on both the performance of the work system and the experience and well-being of the people performing the work (Clegg, 2000). Joint optimization, as opposed to optimization of solely the social or technical aspects is required for efficient and healthy system performance (Badham et al., 2006). There is a large body of work demonstrating the positive benefits of adopting STS principles in organizational redesign. A meta-analysis of over 130 STS studies found that almost 90% reported improvements in safety and productivity and over 90% reported improvements in workers’ attitudes and quality of outputs (Pasmore et al., 1982). Although the approach appears highly suited to the design of sports organizations and practices, it is yet to be applied in this context. Despite this, it is our view that STS provides a novel and highly useful approach to support sports organizations in responding to COVID-19.

The aim of this study was therefore to apply methods from an STS framework to analyze the current functioning of an Australian Football League (AFL) club’s football department. The intention was to use the framework to identify potential modifications to the clubs’ operations in the wake of the impacts associated with the COVID-19 crisis.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This qualitative study applied two phases of the Cognitive Work Analysis (CWA) framework (Vicente, 1999), Work Domain Analysis (WDA), and Social Organization and Cooperation Analysis (SOCA) to develop and analyze a complex systems model of an AFL club football department. The WDA and SOCA development were conducted across three subject matter expert (SME) workshops via the Zoom video conferencing software. Five SMEs from the participating AFL club participated in the current study.

Cognitive Work Analysis

CWA is a sociotechnical systems analysis and design framework that has been used extensively for understanding the structure and behavior of complex systems (Bisantz and Burns, 2008; Stanton et al., 2017). An important feature of CWA is that it provides a series of analytical methods that focus on identifying the constraints present within a system and the resulting impacts on behavior. This allows analysts to understand what constraints exist, what impact the constraints have on behavior, and how constraints can be modified to improve system performance. The formative nature of the framework allows analysts to explore the possibilities for changing behavior through the removal of existing constraints, the addition of new constraints, or through changing the nature of constraints. These unique features have ensured that CWA has become one of the most popular systems analysis and design methods within the discipline of human factors and ergonomics (HFE), and safety science (Stanton et al., 2017). Recently, CWA has been used across a wide range of domains (Bisantz and Burns, 2008; Stanton et al., 2017), including recently in elite sport for organizational analysis (Hulme et al., 2019), performance analysis (McLean et al., 2017, 2019a), and talent identification and development in soccer (Berber et al., 2020).

The CWA framework comprises five phases, each being used to model behavior from differing perspectives: WDA; control task analysis (ConTA); strategies analysis; SOCA; and worker competencies analysis (WCA). An overview of the two phases used in this project, WDA and SOCA, is provided below.

Work Domain Analysis

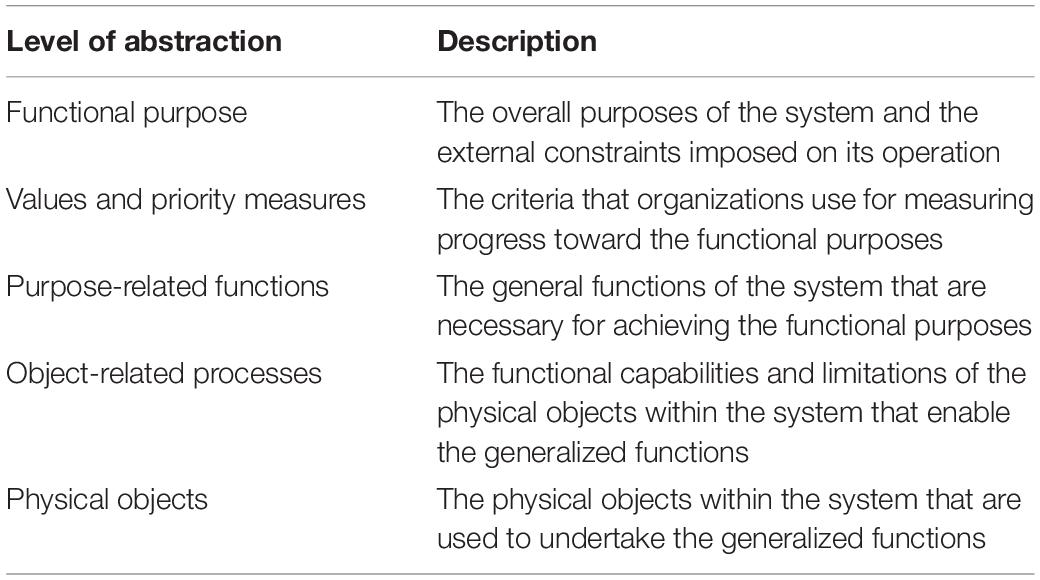

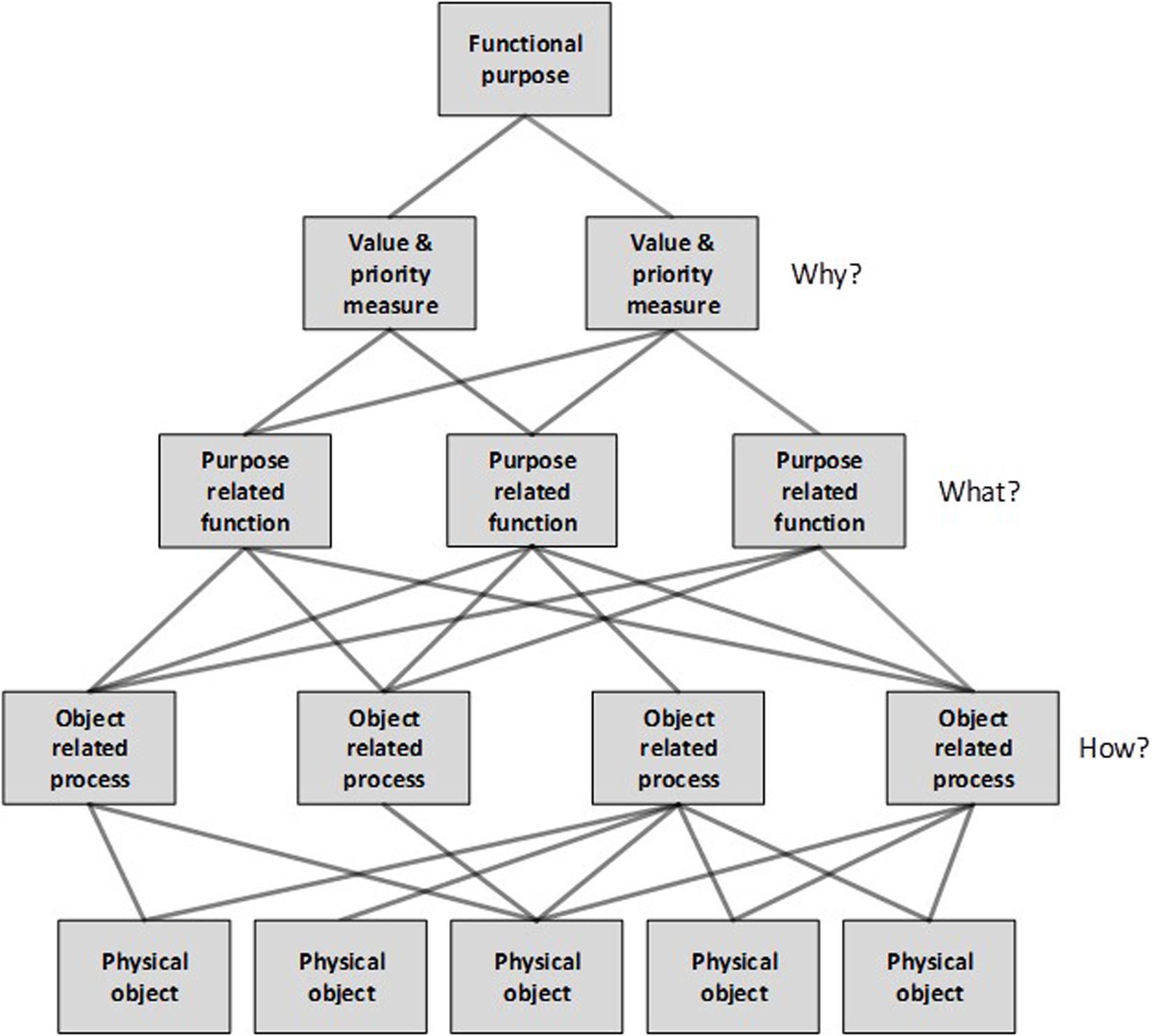

Work domain analysis is used to provide an event and actor independent description of the system under analysis (Figure 1): in this case a current AFL football department “system.” The aim is to describe the purposes of the system and the constraints imposed on the actions of those performing activities within it (Vicente, 1999). This involves using the abstraction hierarchy method to describe the system across five levels of abstraction (Table 1).

Figure 1. Work domain analysis (WDA) framework showing the levels of abstraction, and the means-end links “how-what-why” triad.

A key element of the abstraction hierarchy is that it uses means-ends relationships to link nodes across the five levels of abstraction. For example, the object-related process of “Treatment of player injuries” is undertaken to achieve the function of “Injury prevention, management and rehabilitation” and involves the use of the physical object “Medical equipment.” This feature of the abstraction hierarchy enables analysts to understand why functions and processes are undertaken, and what is used to achieve them.

Social Organization and Cooperation Analysis

Social organization and cooperation analysis is used to identify how functions and processes are distributed across human and non-human agents within the system. A formative element also enables analysts to determine how functions and processes could be allocated following redesign. By assessing the WDA to identify who/what currently does what, and who/what could do what, SOCA aims to specify an optimum allocation of functions for the system under analysis.

Procedure

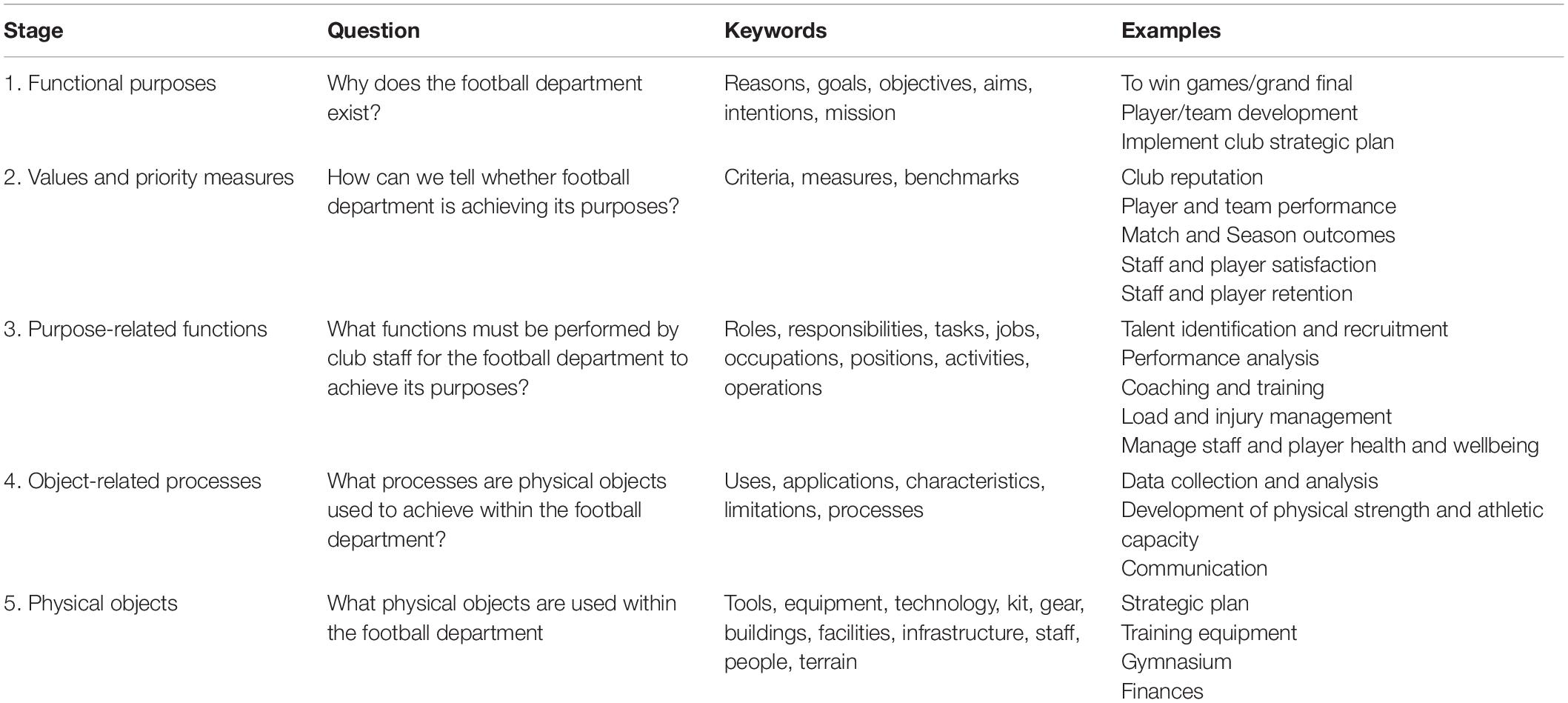

The SMEs had extensive experience in the AFL (16.2 ± 6.1 years), across a range of different roles including players, football director, general manager of football, strength and conditioning, biomechanics, performance analysis, high performance management, AFL governance, coach innovation and education, football strategy and innovation, and playing list management. The SMEs had been employed in these positions at seven different AFL clubs, the AFL, and at the Australian Institute of Sport. In addition, the SMEs had experience in other professional sports including sports science positions in cricket, and tennis. Prior to commencement of the workshops, the SMEs from the participating AFL club’s football department were provided with written information which included an overview of WDA and SOCA as well as a set of preparatory questions for a WDA development workshop. A WDA development workshop was held via Zoom with the SMEs and two researchers with extensive experience in applying WDA (Salmon et al., 2016; McLean et al., 2019a), and the SMEs. The SMEs were asked to respond to a set of WDA prompt questions which were presented in conjunction with relevant keywords and examples [Table 2, adapted from Naikar (2013)]. One researcher used the CWA software tool (Jenkins et al., 2007) to construct an initial draft abstraction hierarchy, using a shared screen function. Following the workshop, the two researchers completed the means-end-links.

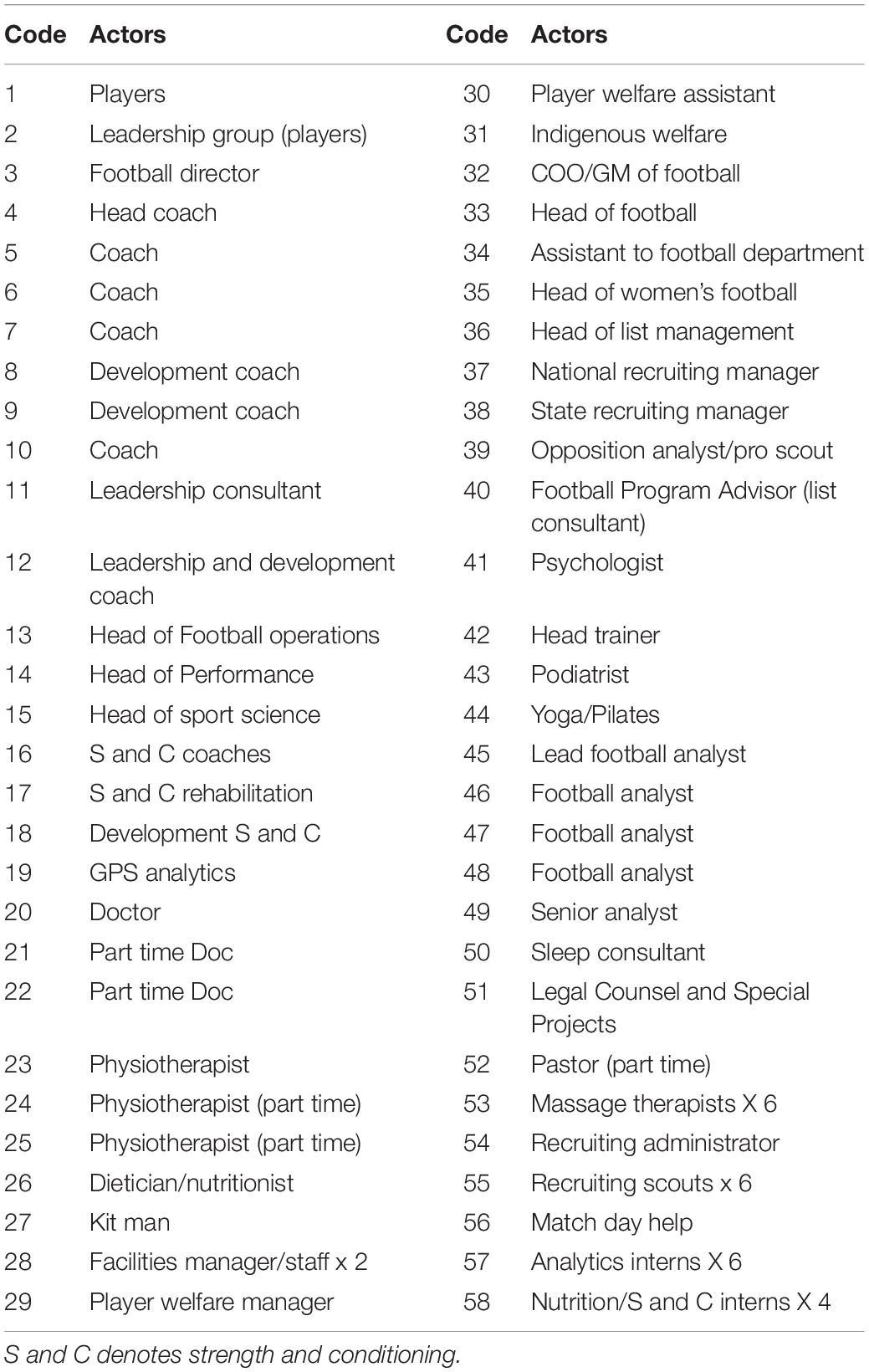

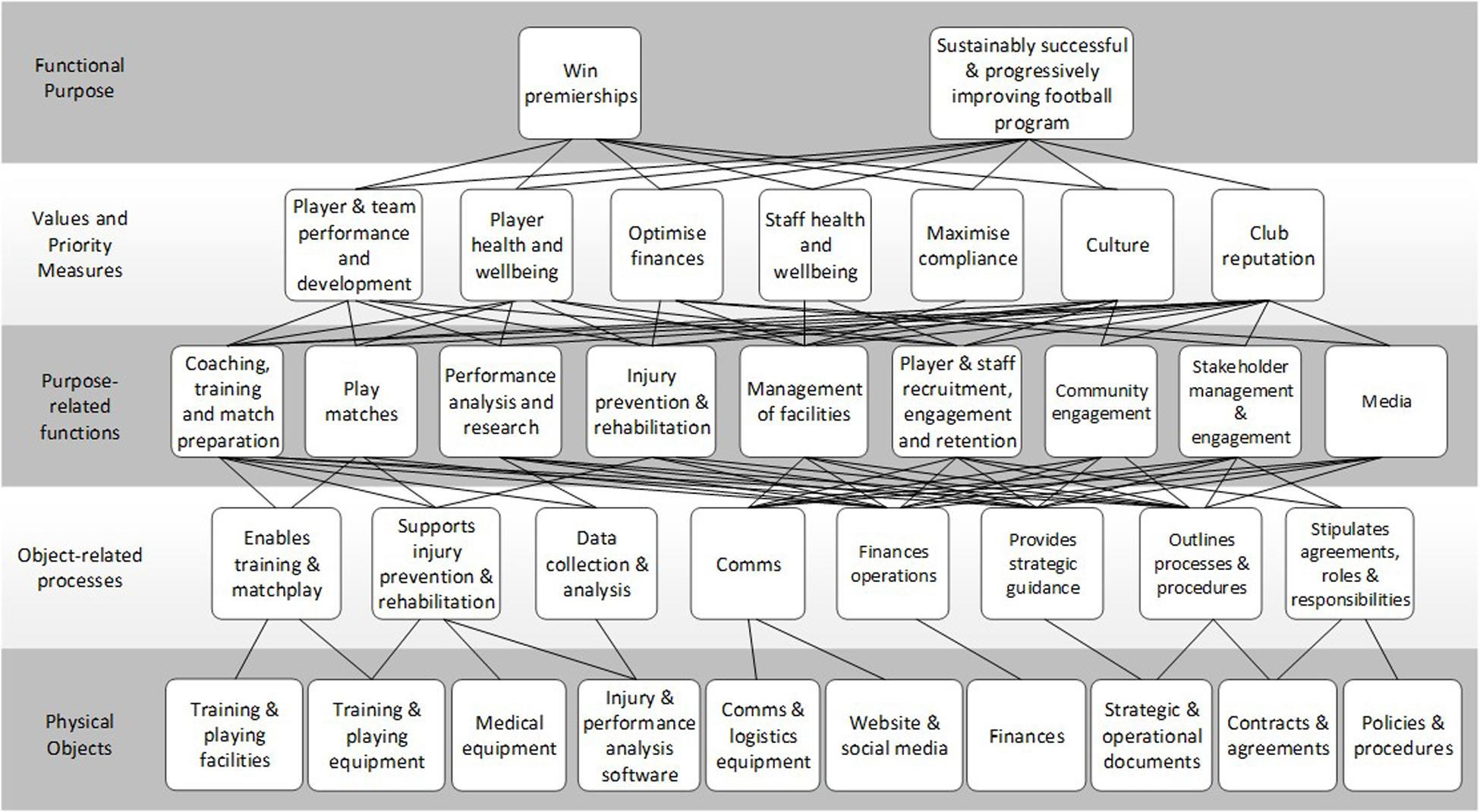

A second Zoom workshop was held with the same SMEs to review and refine the draft abstraction hierarchy and undertake the SOCA phase. The SMEs reviewed the WDA components and the means end links. Any modifications were discussed and revised to achieve the final WDA model (Supplementary Material). For the SOCA phase, SMEs were asked to create a list of all actors (employees, consultants, and volunteers) who currently hold a role in the AFL club’s football department. A list of actors was compiled, and the SMEs were asked to identify which of the actors are associated with the Functional Purposes, Values and Priority Measures, Purpose-Related Functions, Object-Related Processes, and Physical Objects specified in the WDA. Actors were identified and associated with the WDA nodes as described in Table 3.

Table 3. Social organization and cooperation analysis (SOCA) descriptions for the levels of abstraction.

The WDA and SOCA were reviewed and refined by the two researchers, following which a third and final workshop was held to complete the SOCA analysis and discuss initial insights from the model. Discussions were documented by the research team and were used to supplement the insights obtained from the WDA-SOCA model.

Results

Work Domain Analysis

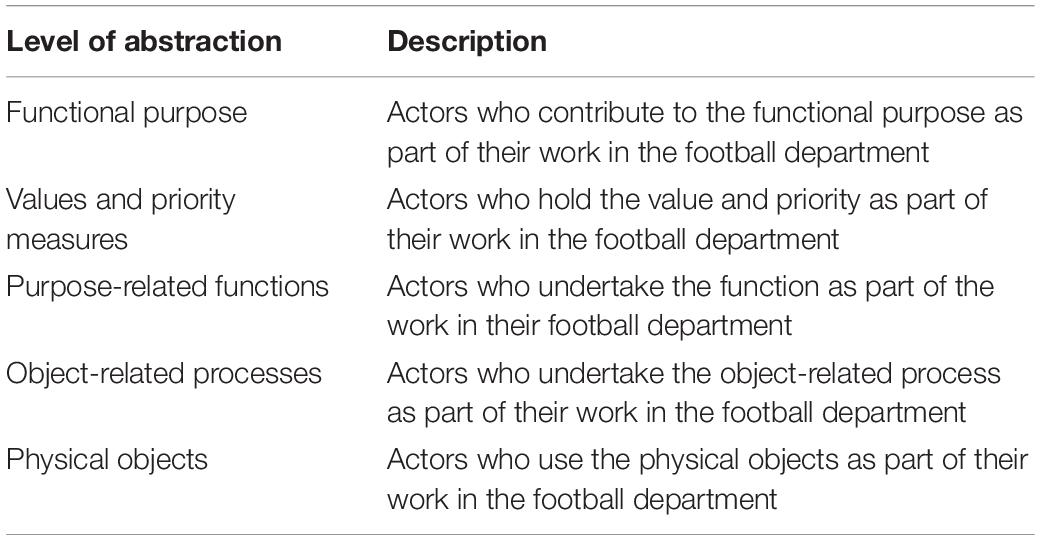

The AFL club football department abstraction hierarchy is presented as Supplementary Material. Given the complexity and size of the model, a summary is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Summary abstraction hierarchy of the AFL club football department. Each level contains summary nodes that encapsulate multi nodes from the overall model. For example, the value and priority measure node of “Player and team performance and development” included “Matches won,” “Percentage differential,” “Continual player improvement,” and “Maximizing player talent.”

According the abstraction hierarchy, the club’s football department has two functional purposes: to “Win premierships,” and to achieve a “Sustainably successful and progressively improving football program.” A total of 25 values and priority measures were identified. These can be broadly grouped into seven categories. The first set includes values relating to player and team performance and development, such as “Matches won,” “Percentage,” “Maximizing player talent,” and “Continual player improvement.” The second set includes values relating to player health and wellbeing, such as “Players physical conditioning,” “Minimizing injuries,” and “Maximizing players health and wellbeing.” The third set includes values relating to club finances, including “Optimizing department spend” and “Optimizing player spend” (salary cap). The fourth set includes values relating to staff health and wellbeing. The fifth set of values relate to compliance such as “Minimizing positive drug tests” (both illicit drugs and performance enhancing drugs) and “Maximizing compliance with AFL rules and regulations.” The sixth set includes values which relate to the development and maintenance of club culture, such as “Player inspiration,” “Player and staff engagement,” and “Embracing and supporting diversity in the playing list.” Finally, the seventh set includes values which contribute to maintenance of the club’s reputation, such as, “Club culture” and “Embrace and support diversity in playing list.”

Forty purpose-related functions were identified. These include functions relating to “Coaching,” “Training and match preparation,” “Playing matches,” “Performance analysis and research,” “Injury prevention and rehabilitation,” “Management of facilities,” “Player and staff recruitment,” “Engagement and retention,” “Community engagement,” “Stakeholder management and engagement,” and “Media.”

At the bottom level of the abstraction hierarchy, thirty-eight physical objects were identified, including “Training and playing facilities” and “Equipment,” “Medical equipment,” “Recovery equipment,” “Performance analysis software,” “Communications and logistics equipment,” “Website and social media,” “Finances,” “Strategic and operational documents,” “Contracts and agreements,” and “Policies and procedures.” According to the abstraction hierarchy, the physical objects support 28 object-related processes including “Training and matches,” “Injury prevention and rehabilitation,” “Data collection and analysis,” “Communications,” “Financial operations,” “Strategic guidance,” “Processes and procedures,” and “Agreements, roles and responsibilities.”

Social Organization and Cooperation Analysis

A list of the AFL club football department actors considered in the SOCA is presented in Table 4.

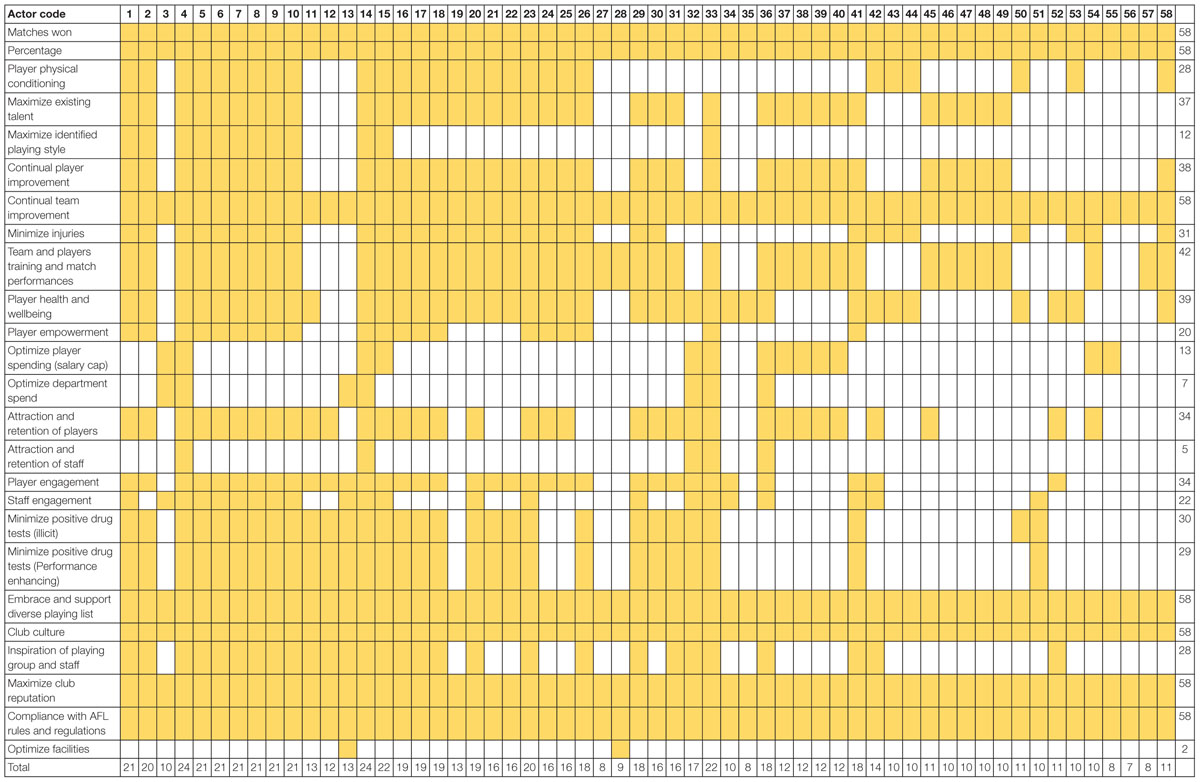

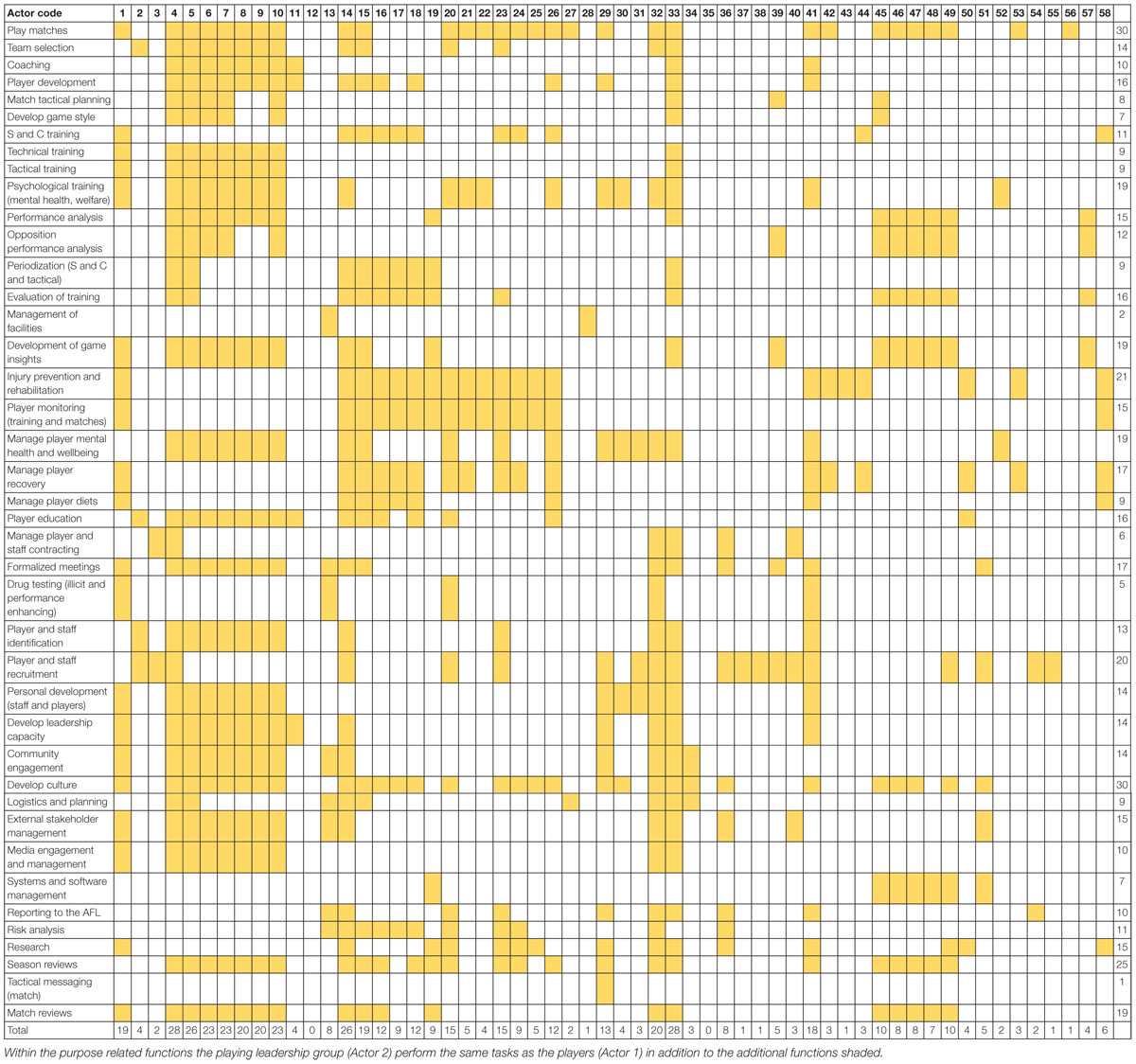

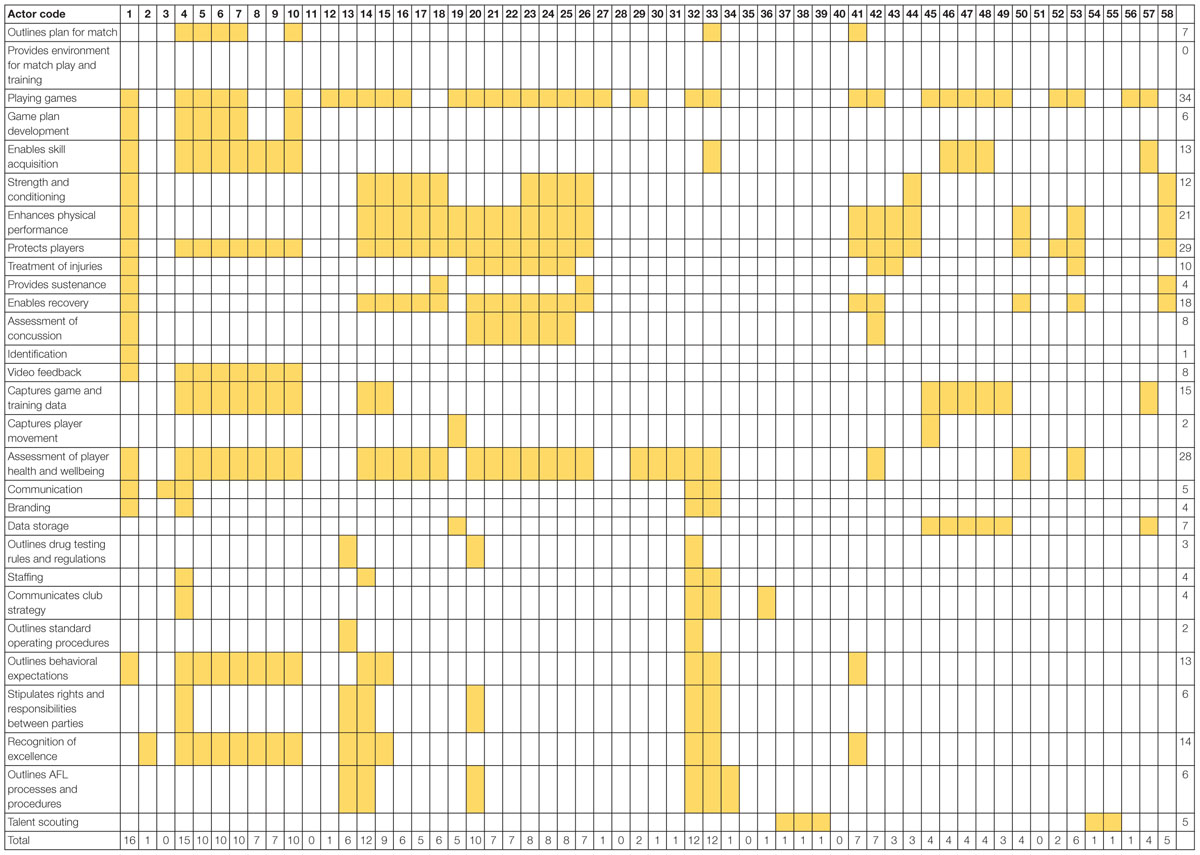

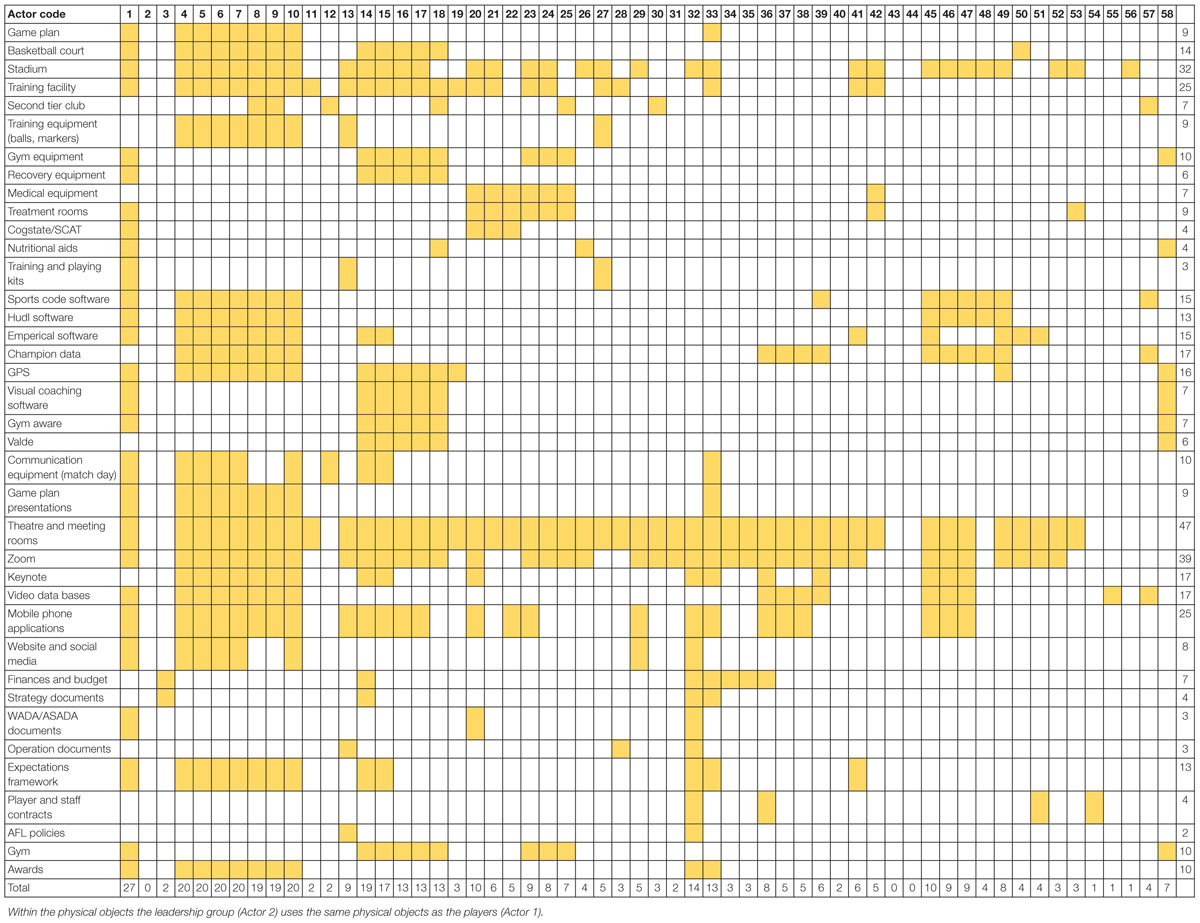

The results of the SOCA are presented in Tables 5–8. The SOCA results demonstrate how functions and processes are distributed across the actors within the system. Table 5 shows that all actors within the football department are associated with seven Values and Priority Measures, these include Matches won, Percentage, Continual team improvement, Embrace and support diverse playing list, Club culture, Maximize club reputation, Compliance with AFL rules and regulations. Table 6 shows that the coaching staff (actors 4–10), head of performance, sports scientists, the head of football, and the COO/GM of football perform a large number of the Purpose Related Functions relative to other actors. Table 7 shows the Object Related Processes associated with the most actors include Playing games, Enhances physical performance, Protects players, and assessment of player health and well-being. Finally, Table 8 shows the coaches and players utilize the majority of physical objects identified in the abstraction hierarchy relative to other actors. A table is not presented for the Functional Purposes level as all actors were deemed to contribute to both. Within Tables 5–8, the variables associated with each level of abstraction listed in the left-hand side column, with the corresponding columns relating to each the actors from Table 4. Shading is used to denote where actors contribute to each variable. Totals are also presented for the absolute number of actors associated with each value and priority (far right-hand side column) and the absolute number of values and priority measures associated with each actor (bottom row of the table).

Table 5. SOCA showing the football department actors associated with the values and priority measures identified in the abstraction hierarchy.

Table 6. SOCA showing the football department actors associated with the purpose related functions identified in the abstraction hierarchy.

Table 7. SOCA showing the football department actors associated with the object related processes identified in the abstraction hierarchy.

Table 8. SOCA showing the football department actors associated with the hierarchy physical objects identified in the abstraction hierarchy.

Discussion

This study applied two methods from the CWA (Vicente, 1999) framework to provide a detailed analysis of the functional structure of an AFL football department with a view to identifying opportunities for redesign. The analysis produced multiple insights which are relevant for the optimization of sports performance departments in general, and for streamlining current football department operations post COVID-19.

Complexity of the Football Department

The initial finding of the current study demonstrates the inherent complexity of an AFL football department via the multiple and interacting factors that influence the behavior, and the diverse set of actors who share responsibility for the performance of the system. As such, the department can be conceptualized as a STS in which social actors (e.g., athletes, coaches, facilities staff) interact with one another and with technologies (e.g., equipment, facilities, websites) to achieve common goals (Walker et al., 2008). In addition, the means-end-links in the abstraction hierarchy indicates a high level of connectivity among the system components and behaviors and demonstrate instances where there is either redundancy (i.e., many resources supporting a node above) and where there are potential fragilities (i.e., few resources supporting a node/purpose). These results are consistent with previous research which indicates that sporting organization performance and functioning is an emergent property of the complex interactions between all system components and actors (Jones et al., 2009; Hulme et al., 2019; Salmon and McLean, 2019).

What Does Systems Modeling Tell Us About the Football Department?

The current analysis identified strengths of the AFL clubs’ department, as well as potential conflicts between systems components. Several strengths of the football department were identified in the WDA including important functions outside of playing football such as community engagement, finances, staff wellbeing, and the development of culture and club reputation (Jones et al., 2009). In line with the aim of the study, the remainder of the discussion will focus on areas for potential improvement and provide recommendations to modify and enhance the club’s current football department in the wake of the impacts associated with COVID-19.

Whilst the two functional purposes are appropriate given the context is elite sport, it seems pertinent to consider the potential adverse impacts of the Functional Purpose of “Win premierships.” As an aspirational Functional Purpose this may be appropriate, however, it is important to note that the AFL club in the current study has endured long periods without achieving this Functional Purpose. Within the study of dynamic system behavior, “seeking the wrong goal” is a common trap made by organizations (Meadows, 2008). If the goal of the system does not reflect the reality of the system, then the system may have problems achieving the intended result (Meadows, 2008). This is known as a stretch goal in organizational behavior research, and although stretch goals can benefit some organizations it appears to be an exception rather than the rule, particularly where achievable and measurable sub-goals are not in place (Sitkin et al., 2011). Stretch goals, compared to more easily achievable goals, increase variance in organizational performance, undermine goal commitment, can adversely impact worker health and wellbeing, and generate lower risk-adjusted performance (Gary et al., 2017). As such, it may be beneficial for the club to set appropriate achievable, attainable and measurable sub-goals which move the organization toward the longer term stretch goal. For example, if at the midpoint of the season the stretch goal of “win premiership” is seemingly out of reach, the overall Purpose can have less of an influence on the behavior of actors within the organization. This is particularly important given that all actors within football department were deemed to contribute to both Functional Purposes. However, if achievable sub-goals become the focus of the organization, progress remains attainable. Without appropriate sub-goals, the realization that the stretch goal will not be achieved mid-season may impact motivation and commitment to the goal. Although stretch goals are attractive to stakeholders, they often produce poor organizational performance (Sitkin et al., 2011; Gary et al., 2017). The use of stretch goals by elite sports organizations is thus only encouraged when appropriate sub-goals are specified and monitored.

The Values and Priority Measures level of the WDA includes the criteria that the football department uses to assess progress toward the Functional Purposes. Many of the measures identified can be used in a straightforward manner to assess progress including “Matches won,” “Percentage differentials,” “Player physical condition,” “Training and match performances.” However, the extent to which data is available to enable the football department to understand whether they are achieving some Values and Priorities is not clear. For example, it is questionable whether valid assessments exist for some of the identified Values and Priority Measures including “Club culture,” “Player empowerment,” and “Maximizing existing talent.” This presents an opportunity for the club to be innovative and develop or adopt new approaches for measuring their progress toward the Functional Purposes. Moreover, the development of valid measures for such aspects of elite sports organization performance represents an important direction for future sports science research.

Many of the measures used within the football department were identified as “lag” indicators in that they are retrospective measures of past performance and outcomes (e.g., “Matches won,” “Percentage,” “Injuries,” “Player improvement”). Within economic and financial modeling and more recently safety science there is an increasing focus on the use of leading indicators to help understand and optimize performance. Leading indicators are pro-active measures that allow organizations to predict, for example, safety issues before they arise (Grabowski et al., 2007). An example of a leading indicator in the current WDA includes “Player physical conditioning” which can be a leading indicator for future injuries. It is our view that the development of additional leading indicators for players, the team, the club, and the overall league could have substantial benefit for the football club and elite sporting organizations. This also represents an area for further research, in particular the identification of specific leading indicators and associated measures in different sports contexts.

Despite only a small number of values and priorities relating to the player and football team’s performance itself (e.g., “Win matches,” “Percentage differential,” “Team and player training and match performance”), many of the Purpose Related Functions and Object-Related Processes identified are focused on supporting these values. This is perhaps expected; however, it is worth noting that less support is ostensibly given to other values and priorities such as staff health and wellbeing, culture, and compliance. This suggests that many functions are geared toward winning football matches, with less functions undertaken in support of other values such as developing culture. This highlights a potential conflict between allocation of resources between winning and developing culture. A counterintuitive approach to improving performance may be to redirect resources to developing culture, which has been shown as one of the most prominent factors contributing to successful sporting organizations (Bell-Laroche et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2014). As such, there may be opportunities to improve the attainment of the lessor supported values as well as those relating to the football team’s performance.

The Purpose-Related Functions identified are largely consistent with those found in previous analyses of elite sporting organizations i.e., “Playing matches,” “Training,” “Performance analysis,” among others (Hulme et al., 2019). An insight derived from this level and the SOCA is the high level of specialist sport science and wellbeing support roles currently used by the football department. This is recognized in previous research with suggestions that professional sports organizations have evolved to encompass an increasingly complex team of specialized experts tasked with a diverse range of responsibilities (Sotiriadou and De Bosscher, 2018; Drust, 2019; Fullagar et al., 2019; Malone et al., 2019). Specifically, the SOCA highlighted the large number of specialist sports science functions and personnel (staff and external consultants) that currently contribute to football department operations. Included are functions such as “Strength and conditioning training,” “Tactical and technical training,” “Psychological training,” “Performance analysis,” “Injury prevention and rehabilitation,” “Player health and wellbeing,” “Management of player diets,” and “Player recovery.” Whilst the intention is to enhance performance, the use of many specialist roles and functions may be viewed differently by coaches and specialists regarding the importance of different activities (Fullagar et al., 2019; Otte et al., 2020). For example, knowledge on tactical and technical expertise is valued by coaches compared to specialist support staff whom often have a vested interest in their own specific area of expertise (Fullagar et al., 2019). This potentially creates the risk of siloed approach whereby the various skill sets are not well integrated (Otte et al., 2020). Given that the coaches ultimately make the decisions regarding training and competition, there is a level of uncertainty around the appropriate utility and value of applied sport science in professional sporting environments (Fullagar et al., 2019). A recent conceptual framework aimed to functionally integrate specialized roles into a multidisciplinary “department of methodology” drawing on expertise of sub-disciplines (e.g., skill acquisition, strength and conditioning) has been proposed (Otte et al., 2020; Rothwell et al., 2020). The purpose is to coordinate activities via shared theory and concepts, communication of ideas, and collaborative design of practice, which may prevent the siloing of sub-disciplines in elite sporting departments (Otte et al., 2020; Rothwell et al., 2020). A further consideration is that the resources required for large teams of specialized support staff and technology (Malone et al., 2019), may not be available post COVID-19. This presents an opportunity to streamline operations by merging roles and enhancing organizational cohesion by moving to a more generalist model whereby general sports science support is provided across these functions by an appropriately skilled but reduced number of personnel (Robertson, 2020).

Another potential negative impact of the large number of specialized support staff employed in professional sport is the conceivable intrusiveness to the players, which is beyond that of most other professions (Drust, 2019). Previous research has shown that a typical English Premier League player has more than 30 individual contacts with performance staff during a normal week (Drust, 2019). Although individual contacts were not measured in this study, the current findings indicate that many of the functions are designed to support player performance, development, and health and wellbeing. Whilst this is important, it also has the potential unwanted consequence of players being overly micromanaged which may diminish autonomy, competence, and subsequently motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2000). For example, the WDA highlights potential conflicts between the micromanagement required for supporting performance, and the functions of “Player empowerment,” “Player education,” and “Develop leadership capacity” in the players. To realize this, the organizational structure should be one that supports the players as the focal point of the club (Kihl et al., 2007), by providing the tools and skills necessary for development. The current findings suggest that, whilst the players are the focal point, many functions appear to be focused on providing direct interventions rather than on empowering players. As indicated in the SOCA, the players do not perform the Functions “Performance analysis,” “Opposition performance analysis,” or “Training evaluation.” Presumably, the players contribute to these functions informally during practice, however, formalizing the involvement of players in these processes may provide autonomy and empowerment.

An insight from the Object-Related Processes level that conflicts with the club’s ambition, is that there are few processes which support the Purpose-Related Functions of “Develop leadership capacity” and “Player education.” Further, the SOCA analysis indicates that the player leadership group currently only undertake four of the 40 functions in the WDA. In the WDA, “Developing leadership capacity” and “Education of players” are linked with several important values and priorities measures above, such as, “Attraction and retention of players,” “Club culture,” and “Player empowerment.” Given the importance of these functions in creating a player led environment, it may be pertinent to explore further ways in which players can be empowered. For example, this may be achieved by enabling player representation in decision making processes and policies that affect the playing group (Thibault and Babiak, 2005; Kihl et al., 2007).

Insights from Physical Objects level of the model included a high degree of overlap in terms of objects and their functionality. For example, “Sports code,” “Hudl,” “Champion Data,” “visual coaching software,” “Strength and conditioning software” are linked to the one process of “Captures game and training data.” While these are all popular tools in sport science and coaching, consideration of how they are being used in terms of the trade-off between cost and resources required for analysis and usability of outputs for coaches is required. This is particularly relevant in light of new financial restrictions introduced following COVID-19. Furthermore, caution is urged with regard to the use of multiple data collection tools and player assessment methods. It is important that the measures do not become a target for the players to pursue at the expense of motivation for training to perform in football matches. This issue has been captured within sports science through Goodhart’s law and the accompanying phrase “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure” (Goodhart, 1984; Strathern, 1997). Assigning importance to metrics can have unintended consequence on behavior which encourages a shift away from the initial intention of improving performance simply to satisfy the metric. For example, the degree of emphasis placed on distance covered, velocity measures (GPS and Gym Aware), the numerous Champion Data metrics (successful possessions, tackles completed, etc.) may have the potential to shift the focus from football performance to its component parts. This form of reductionism is increasingly being recognized as an inappropriate approach for performance analysis and improvement in sport (Glazier, 2010; McLean et al., 2019b; Salmon and McLean, 2019).

The SOCA revealed that there are a high number of actors within the football department. It is out of the scope of this article to determine the appropriate number of actors within the system. However, examination of specific roles is required to determine whether it is feasible to reduce the number of actors whilst still achieving the functions and values and priorities specific in the abstraction hierarchy. A recommendation for other sports organizations is to use methods such as WDA and SOCA to identify opportunities to reorganize their operations in response to COVID-19.

Implications for Sports Organization Restructure Post COVID-19

The current analysis has highlighted potential areas for modification in the AFL club’s football department, and sports performance departments in general. Whilst it is beyond the scope of the present article to discuss redesigns specific to the club in question, it is possible to prescribe a generic approach that sports organizations can use in response to COVID-19 and other high impact events. First and foremost, it is the authors opinion that redesign activities should be driven by core STS values and principles (Clegg, 2000; Read et al., 2015). Read et al. (2015) outline five core STS design values that appear to be pertinent in the sports context:

1. Humans should be treated as assets rather than as unpredictable, error-prone, and the cause of problems in otherwise well-designed systems.

2. Technology should be used as a tool to assist humans, rather than being seen as an end in its own right (Clegg, 2000; Norros, 2014).

3. Designs should focus on promoting quality of life, rather than creating strict work requirements (e.g., lack of flexibility around working hours and breaks), poor work design (e.g., repetitive tasks, lack of task rotation) and unachievable expectations. Quality work should be challenging and incorporate variety, should include scope for decision-making and choice and facilitate ongoing learning, should incorporate social support and recognition, and should have social relevance to life outside work (Cherns, 1976, 1987).

4. Designs should respect individual differences in the needs and preferences of the various end-users. For example, some players may prefer high levels of autonomy and control, while others may not.

5. Designers should consider all stakeholders, including the impacts of choices they make on various stakeholders. In the present context, these stakeholders include end users, broader club personnel, the community, sponsors, and the AFL.

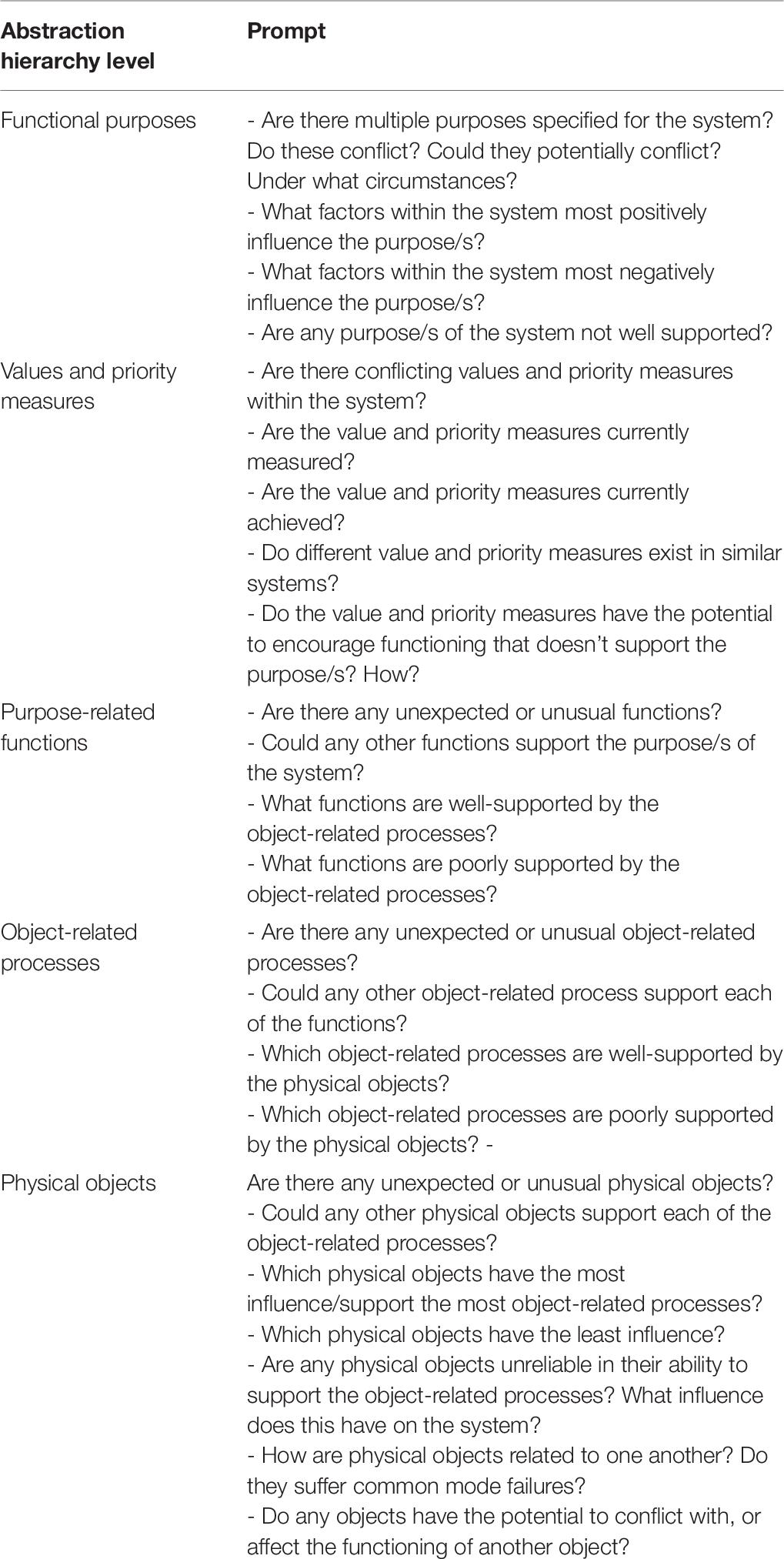

Based on conducting analyses similar to the one presented in this article, sports organizations could use the prompts presented in Table 9 to identify areas where redesign is required (adapted from Read et al., 2016). Participatory design approaches should then be used in conjunction with the STS values to develop and refine design concepts.

Limitations

The current study contained potential limitations. First, a small number of SMEs were involved in the WDA-SOCA development. However, the SMEs had extensive experience at the current organization and more broadly in the AFL, as well as across several different AFL clubs. Further development and validation of the model and its contents could occur in-house with additional club stakeholders and players. Despite the inclusion of a diverse set of SMEs, potential bias needs to be considered given the financial implications brought about by COVID-19 and the pending restructure to resource allocation within the football department. Further, current players were not included as SMEs in the current study. Given the important role of players within the football department, player input may have provided additional insights specific to the playing group. A second limitation is that the abstraction hierarchy method does not include weightings for the nodes or connections between the nodes across the levels of abstraction. As a result, the relative strength of different nodes and links is not considered and nodes with low incoming or outgoing links could be misinterpreted as being less important or less supported than others (e.g., culture in the present analysis). Whilst this was considered in the present analysis, future research could explore the use of weights to determine the relative importance of values, functions, processes and objects.

Conclusion

This study applied methods from the CWA framework, WDA and WDA-SOCA, in a first-of-its-kind approach to model an AFL football department. The modeling enabled identification of potential modifications to the clubs’ operations in general, and for streamlining of operations in the wake of COVID-19. The realization of conflicts within the system captured via the modeling will assist the club to redesign operations, and the analysis has important messages for elite sports organizations generally. Firstly, sporting organizations should pursue appropriate goals that reflect the actual state of the system. Secondly, the measures used to assess whether the goals of the system are being achieved need to be specific and measurable in order to obtain valid assessments. Thirdly, shifting to a generalist model that combines specialized roles and objects may increase organizational cohesion, increase system resilience, reduce overlap, and reduce operational costs. This study has extended the applications of systems modeling in sport and provided a practical guide that can be used as template to direct other sporting clubs aiming to redesign their operations. It is hoped that this article emphasizes the important role that sociotechnical systems theory methods can have on sports and sports research.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, model building, analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588959/full#supplementary-material

References

Badham, R., Clegg, C., and Wall, T. (2006). “Sociotechnical theory,” in In International Encyclopedia of Ergonomics and Human Factors, ed. W. Karwowski (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press).

Bell-Laroche, D., MacLean, J., Thibault, L., and Wolfe, R. (2014). Leader perceptions of management by values within Canadian national sport organizations. J. Sport Manag. 28, 68–80. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2012-0304

Berber, E., McLean, S., Beanland, V., Read, G. J., and Salmon, P. M. (2020). Defining the attributes for specific playing positions in football match-play: a complex systems approach. J. Sports Sci. 38, 1248–1258. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2020.1768636

Bisantz, A. M., and Burns, C. M. (2008). Applications of Cognitive Work Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Bittencourt, N., Meeuwisse, W., Mendonça, L., Nettel-Aguirre, A., Ocarino, J., and Fonseca, S. (2016). Complex systems approach for sports injuries: moving from risk factor identification to injury pattern recognition—narrative review and new concept. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 1309–1314. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095850

Cherns, A. (1976). The principles of sociotechnical design. Hum. Relat. 29, 783–792. doi: 10.1177/001872677602900806

Cherns, A. (1987). Principles of sociotechnical design revisted. Hum. Relat. 40, 153–161. doi: 10.1177/001872678704000303

Clegg, C. W. (2000). Sociotechnical principles for system design. Appl. Ergon. 31, 463–477. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(00)00009-0

Drust, B. (2019). Applied science and soccer: a personal perspective on the past, present and future of a discipline. Sport Perform. Sci. Rep. 56, 1–7.

Eason, K. (2014). Afterword: the past, present and future of sociotechnical systems theory. Appl. Ergon. 45, 213. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.09.017

Evans, A. B., Blackwell, J., Dolan, P., Fahlén, J., Hoekman, R., Lenneis, V., et al. (2020). Sport in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: towards an agenda for research in the sociology of sport. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 17, 85–95. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2020.1765100

Fullagar, H. H., McCall, A., Impellizzeri, F. M., Favero, T., and Coutts, A. (2019). The translation of sport science research to the field: a current opinion and overview on the perceptions of practitioners, researchers and coaches. Sports Med. 49, 1817–1824. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01139-0

Gary, M. S., Yang, M. M., Yetton, P. W., and Sterman, J. D. (2017). Stretch goals and the distribution of organizational performance. Organ. Sci. 28, 395–410. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2017.1131

Glazier, P. S. (2010). Game, set and match? Substantive issues and future directions in performance analysis. Sports Med. 40, 625–634. doi: 10.2165/11534970-000000000-00000

Goodell, J. W. (2020). COVID-19 and finance: agendas for future research. Finance Res. Lett. 35:101512. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101512

Goodhart, C. A. (1984). “Problems of monetary management: the UK experience,” in Monetary Theory and Practice (London: Macmillan Press), 91–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-17295-5_4

Grabowski, M., Ayyalasomayajula, P., Merrick, J., Harrald, J. R., and Roberts, K. (2007). Leading indicators of safety in virtual organizations. Saf. Sci. 45, 1013–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2006.09.007

Heymann, D. L., and Shindo, N. (2020). COVID-19: what is next for public health? Lancet 395, 542–545. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30374-3

Hulme, A., McLean, S., Read, G. J. M., Dallat, C., Bedford, A., and Salmon, P. M. (2019). Sports organisations as complex systems: using cognitive work analysis to identify the factors influencing performance in an elite Netball organisation. Front. Sports Active Living 1:56.

Jenkins, D. P., Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., Walker, G. H., Young, M. S., Whitworth, I., et al. (2007). “The development of a cognitive work analysis tool,” Paper Presented at the International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics, Berlin.

Johnson, T., Martin, A. J., Palmer, F. R., Watson, G., and Ramsey, P. L. (2014). A core value of pride in winning: the all blacks’ team culture and legacy. Int. J. Sport Soc. 4, 1–14. doi: 10.18848/2152-7857/cgp/v04i01/59414

Jones, G., Gittins, M., and Hardy, L. (2009). Creating an environment where high performance is inevitable and sustainable: the high performance environment model. Annu. Rev. High Perform. Coach. Consult. 1, 139–150.

Kihl, L. A., Kikulis, L. M., and Thibault, L. (2007). A deliberative democratic approach to athlete-centred sport: the dynamics of administrative and communicative power. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 7, 1–30. doi: 10.1080/16184740701270287

Malone, J. J., Harper, L. D., Jones, B., Perry, J., Barnes, C., and Towlson, C. (2019). Perspectives of applied collaborative sport science research within professional team sports. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 19, 147–155. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2018.1492632

McLean, S., Hulme, A., Mooney, M., Read, G. J. M., Bedford, A., and Salmon, P. M. (2019a). A systems approach to performance analysis in women’s netball: using work domain analysis to model elite netball performance. Front. Psychol. 10:201. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00201

McLean, S., Read, G. J. M., Hulme, A., Dodd, K., Gorman, A. D., Solomon, C., et al. (2019b). Beyond the tip of the iceberg: using systems archetypes to understand common and recurring issues in sports coaching. Front. Sports Active Living 1:49. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2019.00049

McLean, S., Salmon, P. M., Gorman, A. D., Read, G. J., and Solomon, C. (2017). What’s in a game? A systems approach to enhancing performance analysis in football. PLoS One 12:e0172565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172565

Naikar, N. (2013). Work Domain Analysis: Concepts, Guidelines, and Cases. Baco Rotan, FL: CRC Press.

Norros, L. (2014). Developing human factors/ergonomics as a design discipline. Appl. Ergon. 45, 61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.04.024

Otte, F. W., Rothwell, M., Woods, C., and Davids, K. (2020). Specialist coaching integrated into a department of methodology in team sports organisations. Sports Med. Open 6, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/21640629.2013.822152

Parnell, D., Widdop, P., Bond, A., and Wilson, R. (2020). COVID-19, networks and sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 1–7. doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1750100

Pasmore, W., Francis, C., Haldeman, J., and Shani, A. (1982). Sociotechnical systems: a North American reflection on empirical studies of the seventies. Hum. Relat. 35, 1179–1204. doi: 10.1177/001872678203501207

Read, G. J., Salmon, P., Lenne, M. G., Stanton, N., Mulvihill, C. M., and Young, K. L. (2016). Applying the prompt questions from the cognitive work analysis design toolkit: a demonstration in rail level crossing design. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 17, 354–375. doi: 10.1080/1463922x.2016.1143987

Read, G. J., Salmon, P. M., Lenné, M. G., and Stanton, N. A. (2015). Designing sociotechnical systems with cognitive work analysis: putting theory back into practice. Ergonomics 58, 822–851. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2014.980335

Read, G. J., Salmon, P. M., Goode, N., and Lenné, M. G. (2018). A sociotechnical design toolkit for bridging the gap between systems-based analyses and system design. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries 28, 327–341. doi: 10.1002/hfm.20769

Robertson, S. (2020). Man & machine: adaptive tools for the contemporary performance analyst. J. Sports Sci. 38, 2118–2126.

Rothwell, M., Davids, K., Stone, J., O’Sullivan, M., Vaughan, J., Newcombe, D., et al. (2020). A department of methodology can coordinate transdisciplinary sport science support. J. Exp. 3, 55–65.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). The darker and brighter sides of human existence: basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychol. Inq. 11, 319–338. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1104_03

Salmon, P., Mclean, S., Dallat, C., Mansfield, N., Solomon, C., and Hulme, A. (2021). Human Factors and Ergonomics in Sport: Applications and Future Directions. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Salmon, P. M., Lenné, M. G., Read, G. J., Mulvihill, C. M., Cornelissen, M., Walker, G. H., et al. (2016). More than meets the eye: using cognitive work analysis to identify design requirements for future rail level crossing systems. Appl. Ergon. 53, 312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2015.06.021

Salmon, P. M., and McLean, S. (2019). Complexity in the beautiful game: implications for football research and practice. Sci. Med. Football 4, 162–167. doi: 10.1080/24733938.2019.1699247

Sato, S., Oshimi, D., Bizen, Y., and Saito, R. (2020). The COVID-19 outbreak and public perceptions of sport events in Japan. Manag. Sport Leisure 1–6. doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1773301

Sitkin, S. B., See, K. E., Miller, C. C., Lawless, M. W., and Carton, A. M. (2011). The paradox of stretch goals: organizations in pursuit of the seemingly impossible. Acad. Manag. Rev. 36, 544–566. doi: 10.5465/amr.2011.61031811

Sotiriadou, P., and De Bosscher, V. (2018). Managing high-performance sport: introduction to past, present and future considerations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 18, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/16184742.2017.1400225

Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., Walker, G. H., and Jenkins, D. P. (2017). Cognitive Work Analysis: Applications, Extensions and Future Directions. Baco Rotan, FL: CRC Press.

Strathern, M. (1997). ‘Improving ratings’: audit in the British University system. Eur. Rev. 5, 305–321. doi: 10.1017/s1062798700002660

Thibault, L., and Babiak, K. (2005). Organizational changes in Canada’s sport system: toward an athlete-centred approach. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 5, 105–132. doi: 10.1080/16184740500188623

Toresdahl, B. G., and Asif, I. M. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): considerations for the competitive athlete. Sports Health 12, 211–224.

Trist, E. L., and Bamforth, K. W. (1951). Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: an examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system. Hum. Relat. 4, 3–38. doi: 10.1177/001872675100400101

Vicente, K. J. (1999). Cognitive Work Analysis: Toward Safe, Productive, and Healthy Computer-Based Work. Baco Rotan, FL: CRC Press.

Walker, G. H., Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., and Jenkins, D. P. (2008). A review of sociotechnical systems theory: a classic concept for new command and control paradigms. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 9, 479–499. doi: 10.1080/14639220701635470

World Health Organisation (2020). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Keywords: football, complexity, sociotechnical systems, COVID-19, sport, cognitive work analysis, systems analysis

Citation: McLean S, Rath D, Lethlean S, Hornsby M, Gallagher J, Anderson D and Salmon PM (2021) With Crisis Comes Opportunity: Redesigning Performance Departments of Elite Sports Clubs for Life After a Global Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11:588959. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588959

Received: 30 July 2020; Accepted: 02 December 2020;

Published: 20 January 2021.

Edited by:

Hugo Borges Sarmento, University of Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

John William Francis, University of Worcester, United KingdomCarl Woods, Victoria University, Australia

Copyright © 2021 McLean, Rath, Lethlean, Hornsby, Gallagher, Anderson and Salmon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Scott McLean, c21jbGVhbkB1c2MuZWR1LmF1

Scott McLean

Scott McLean David Rath2

David Rath2 Paul M. Salmon

Paul M. Salmon