95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 15 February 2021

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572100

This article is part of the Research Topic The Behavioral and Psychological Impact of Online Risks for Adolescents View all 7 articles

The present study investigated the mediating role of negative emotion in the relationship between cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and the moderating role of friendship quality in the indirect relationship. This model was tested with 1,326 Chinese adolescents who suffered from cyberbullying in the last 1 year; 727 were boys and 591 were girls, and their mean age was 13.67 years (SD = 1.34, range 11–17). Participants filled out questionnaires regarding cybervictimization, negative emotion, friendship quality, and non-suicidal self-injury. After demographic variables were controlled, cybervictimization was significantly positively associated with non-suicidal self-injury. Mediation analysis revealed that negative emotion partially mediated the association between cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury. Moderated mediation analysis further indicated that the mediated path was weaker for adolescents with higher levels of friendship quality. These findings underscore the importance of identifying the mechanisms that moderate the mediated path between cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents.

Cyberbullying is a term used referring to the repeated dissemination of hostile or offensive information by electronic or digital media by individuals or groups in an attempt to cause psychological injury or discomfort to others. This behavior is characterized by invisibility and anonymity (Tokunaga, 2010). A transcultural study found that 8.8% were cybervictims, 3.1% were cyberaggressors, and 4.9% were cybervictims-cyberaggressors in Spain, whereas 8.7% were cybervictims, 5.1% were cyberaggressors, and 14.3% were cybervictims-cyberaggressors in Ecuador (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2020). The situation in China seems to be much more serious. According to a study of Chinese adolescents, 82.77% of adolescent respondents experienced cyberbullying at least once in the previous year, and 57.21% reported engaging in cyberbullying toward others more than once (Chen et al., 2016). Just like traditional bullying, cyberbullying is an intentional aggressive act that can be repeated and is designed to cause harm to the individual (Olweus, 2013). Of those who experience cyberbullying, 31% reported being extremely anxious, 10% felt very fearful, and 19% felt embarrassed (Raskauskas and Stoltz, 2007). In serious cases, cyberbullying has led to victims engaging in self-injurious behaviors (Hay and Meldrum, 2010).

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a psychiatric behavior that is relatively common in adolescents and involves individuals intentionally and repeatedly physically harming themselves by engaging in behaviors such as cutting, burning, piercing, and hitting the wall. This behavior often is performed without the intent of committing suicide and is not accepted by society (Klonsky and Olino, 2008; Jiang et al., 2011). As a maladaptive coping strategy, NNSI has adverse consequences for adolescents’ mental health. The research showed that adolescents who frequently engage in self-injurious behaviors are more likely to experience depression and anxiety (Sho et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2017) and have low self-esteem (Nock et al., 2009). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), categorized NSSI as an undiagnosed disorder; however, these behaviors have drawn increasing attention among those in the field of mental health. In the adolescent stage, NSSI has a development process with age (Barrocas et al., 2014), and there may be some gender difference (Gandhi et al., 2015). Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have confirmed that bullied adolescents are more likely to engage in NNSI than non-bullied adolescents, and as the rates of bullying increases so does the risk for NSSI (Jantzer et al., 2015; van Geel et al., 2015). As with traditional bullying, cybervictimization has been found to positively predict adolescents’ NNSI (Hay and Meldrum, 2010; Kessel Schneider et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2020).

Although prior research has identified a relationship between traditional bullying and adolescents’ NSSI, few studies have explored NSSI as a consequence of cyberbullying. Given the high incidence of adolescents’ cybervictimization and the deleterious consequences of NSSI, investigating their relationship could enhance the field’s understanding of the sequelae of cyberbullying and develop effective intervention strategies. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate a conceptual model in a sample of Chinese adolescents in which cybervictimization would increase negative emotions, which, in turn, would increase NSSI. Then, the indirect association between cybervictimization and NSSI would be moderated by friendship quality (i.e., a moderated-mediation model). The friendship is a kind of social support, which provides support and company to friends, and the friendship quality is the measurement index that reflects the degree of friendship.

General Strain Theory (GST) proposes that when individuals encounter environmental stimulation or stressful events (strain stimulation) and cannot solve it through existing experience or ability, they will experience a subjective feeling of being physiologically and psychologically oppressed. To alleviate this sense of oppression, they may use maladaptive behaviors (Agnew, 1992). From this theory, negative emotions are not only a result of strain stimulation but also a contributing factor for risky behaviors, which serves as a mediating variable between environment stimulation and behavior consequence. Existing research has shown that being bullied is a significant stressor, and adolescents who experience bullying may engage in NSSI (Claes et al., 2015). So, we propose that negative emotion might act as a mediator in the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI among adolescents.

First, cybervictimization is often closely related to the victim’s negative emotions. Li (2015) compared cyberbullying to traditional bullying using a meta-analysis and found that the negative effects of cyberbullying on adolescents’ mental health were comparable to the effects of traditional bullying. Franks (2015) interviewed 10 adolescents aged 13–18 years and found that the emotional sequelae of cybervictimization included the loss of self-esteem and self-confidence as well as increased anger, embarrassment, and grief. When compared to adolescents with no experience of cyberbullying, adolescents who have experienced cyberbullying have higher levels of hostility, depressive symptoms, and anxiety related to persecution (Fan et al., 2018).

Second, managing negative emotions has been identified as a primary motivational factor for adolescents’ NSSI. The Experiential Avoidance Model (EAM) posits that the main function of NSSI is the avoidance of internal experiences or feelings that an individual does not want to experience (Chapman et al., 2006). Klonsky (2007) pointed out that the majority of research has viewed NSSI as a negative emotional coping style. Hughes et al. (2019) reported that among the numerous factors, negative emotions, such as anxiety and feelings of being overwhelmed, are the strongest predictors of adolescents’ NSSI. Behavioral experiments have also demonstrated that both guilt and shame could induce adolescents’ NSSI, while NSSI reportedly alleviated feelings of guilt and shame (Wang et al., 2019).

Although the adolescents who experience frequent cyberbullying and have increased negative emotions might be at increased risk for NSSI, a positive correlation between the constructs has not been consistently shown (Kessel Schneider et al., 2012). This heterogeneity in outcomes might be contingent upon individuals’ social support that moderates the impact of cybervictimization on NSSI. The buffering model of social support proposes that social support, which is an important protective factor, could effectively reduce the adverse effects of stressful life events on adolescents’ mental health (Uchino, 2006). Several studies have indicated that social support buffers the relationship between adverse event life such as bullying and NSSI (Christoffersen et al., 2015; Claes et al., 2015; Alexandra et al., 2017). Shaw et al. (2019) found that social support plays a significant role in coping with bully effectively. Friendship quality is the measurement index of friendship, which reflects the support provided by friends, the degree of company, and the level of conflict (Parker and Asher, 1993). High friendship quality can not only provide external social support but also help to enhance their internal self-worth, so that adolescents can actively deal with setbacks and stress (Troop-Gordon et al., 2015). Mona (2017) found that peer social support was a potential protective factor for NSSI among adolescents.

When adolescents have emotional disorders due to life events, they might generate negative emotions such as loneliness, depression, and anxiety; however, high-quality friendship becomes a buffer for adolescents to resist negative emotions (Mounts, 2002; Kingery et al., 2011). This buffer then helps reduce the occurrence of externalizing behavior (Burk and Laursen, 2005; Tian et al., 2018). You et al. (2016) examined how peer group impulsivity moderated the individual-level relationship between depression and NSSI and found that friendship group pre-meditation weakened the relationship between individual depression and NSSI, while friendship group negative urgency strengthens the relationship between depression and NSSI.

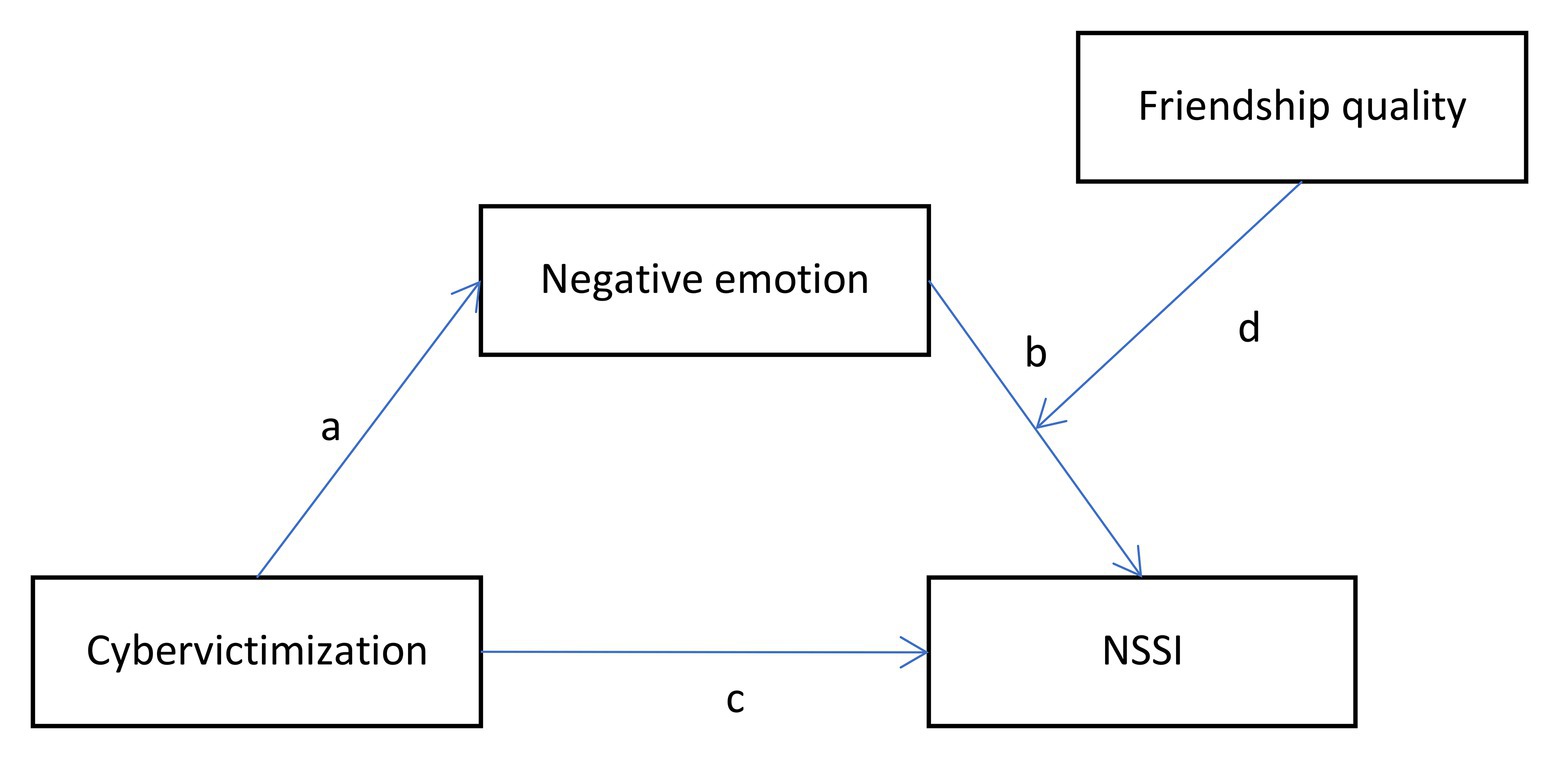

The purpose of the present study was twofold. First, this study examined whether negative emotion mediates the association between cybervictimization and NSSI in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Given existing research, we proposed the following for Hypothesis 1: Cybervictimization would positively impact adolescents’ negative emotions, which, in turn, would increase adolescents’ NSSI. In other words, negative emotions would mediate the association between cybervictimization and adolescents’ NSSI. Second, the study explored whether the indirect relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI via negative emotions was moderated by friendship quality. Based on the buffering hypothesis of social support and empirical evidence, we propose the following for Hypothesis 2: The indirect association between cybervictimization and NSSI via negative emotions would vary depending on the level of the adolescents’ friendship quality. Specifically, a high level of friendship quality would attenuate the path between negative emotion and NSSI. This study would contribute to an enhanced understanding the detrimental influences of cyberbullying on adolescents and provide insight regarding the development prevention strategies and methods of intervention. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed moderated-mediation model.

Figure 1. The proposed moderated-mediation model of the relationship between cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI).

Participants were selected from two middle schools and two high schools in the Hunan province of China. Overall, 1,800 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding the invalid questionnaires, such as a pattern of irregular responses and blank questionnaires, 1,668 valid questionnaires were collected. Of these, 1,324 (79.38%) participants reported that they had been bullied on the Internet at least once in the last year. These participants were the focus of the present study. Among the adolescents experiencing cybervictimization, 727 (54.91%) were boys, 591 (44.65%) were girls, 6 (0.44%) were missing. The mean age of the participants was 13.67 years (SD = 1.34, range 11–17).

Cyberbullying Scale was developed by Kwan and Skoric (2013) and translated and revised into the Chinese version by Chen et al. (2016), with items on both cyberbullying and cybervictimization, each of which included 17 questions, such as, “I have received threatening messages on social network sites.” The current study utilized the section that included the cybervictimization items. A 6-point rating scale was used in this questionnaire to rate items (1 = never, 2 = once, 3 = twice to four times, 4 = five times to seven times, 5 = eight times to 10 times, 6 = more than 10 times). The higher the total score, the more encounters with cyberbullying. In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

The Negative Emotion Scale was compiled by Bradburn (1969) and revised by Chen and Zhang (2004) to measure children’s and adolescents’ negative emotions, including loneliness, depression, and irritability. The questionnaire consists of six items, such as, “I feel inexplicably annoyed.” Each item was rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (no) to 4 (often), with the total score serving as an indicator of negative emotions. Higher scores meant greater negative emotions. The validity of the scale has been demonstrated to be good. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.81.

Friendship Quality was measured using a scale initially developed by Parker and Asher (1993), which was then revised to create a brief version by Zou et al. (1998). The scale consists of 18 items, such as “We often help each other,” which represent six dimensions: affirmation and caring, intimate and exchange, companionship and recreation, help and guidance, conflict and betrayal, and conflict resolution. The items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from no coincidence to complete coincidence, with the conflict and betrayal dimension using reverse scoring. The total score of friendship quality is obtained summing the ratings for each item, with higher scores indicating higher friendship quality. In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.85.

The Adolescent Self-Harm Scale was revised by Yu (2013) based on an existing scale (Feng, 2008) that assessed adolescents’ NSSI in contexts that do not involve suicidal intention. The questionnaire consists of 19 items, 18 of which measure two parallel components of NSSI – the frequency of NSSI and degree of physical harming behavior, such as “cut your skin intentionally,” and the last item was an open-ended question. The frequency items were rated on four levels: never, once, twice to four times, and five times or more, which were scored 0–3, respectively. The degree of physical harming items was rated on five levels: none, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe. The total score was the sum of the scores from the two parts, with higher scores indicating more severe NSSI. For this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Given that prior research has suggested that NSSI is correlated with the gender and age of adolescents (Barrocas et al., 2014; Li et al., 2019), we included these variables as covariates in the statistical analyses. Adolescent gender was dummy coded such that 0 = male and 1 = female.

This present study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Institute of Psychology, Hunan Normal University. Data were collected in middle school classrooms between October and November in 2017. Undergraduate and graduate students in the psychology department were trained to collect the data and administered the questionnaires using standardized scripts that followed a procedure manual to ensure the standardization of the data collection process. Informed consent was obtained from the school administrators, adolescents, and their parents before data collection. The questionnaire was distributed in class. It took about 15 min to complete all the questionnaires. After all the participants answered, the questionnaire was collected. Every participant who completed all questionnaires received a ballpoint pen as incentives.

We used SPSS 19.0 to complete all statistical analysis. First, we calculated the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for our variables of interest and the control variables. Second, we used Hayes (2013) PROCESS macro (Model 4) to evaluate the mediating effect of negative emotions. Finally, we analyzed the moderated-mediation model using Hayes (2013) PROCESS macro (Model 14). All the continuous variables were standardized, and the interaction terms were computed from these standardized scores. The bootstrapping method produces 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals of these effects from 5,000 re-samples of the data. Confidence intervals that did not contain zero indicated significant effects. In all analyses, we included participants’ gender and age as covariates.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for all study variables are presented in Table 1. The correlation matrix showed that cybervictimization in the sample of adolescents in China was significantly related to gender and age. Cybervictimization was negatively associated with gender (r = −0.12, p < 0.01) and positively associated with age (r = 0.08, p < 0.01). Moreover, cybervictimization was positively associated with NSSI (r = 0.30, p < 0.01), as was negative emotion (r = 0.22, p < 0.01). Finally, negative emotions were positively associated with NSSI (r = 0.22, p < 0.01).

The results are shown in Table 2. After controlling for gender and age, the bias-corrected bootstrap method indicated that the indirect effect of cybervictimization on NSSI through negative emotions was significant, ab = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.06], with the mediating effect accounting for 13.06% of the variance. Furthermore, the direct effect of cybervictimization on NSSI was statistically significant, c = 0.28, SE = 0.10, 95% CI [0.23, 0.034], p < 0.001. Therefore, the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI was partially mediated by negative emotions.

The results are shown in Table 3. It was determined that cybervictimization has a significant effect on negative emotion (β = 0.23, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.18, 0.28], p < 0.001), and the effect of negative emotions on NSSI was statistically significant (β = 0.16, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.11, 0.21], p < 0.001). Further, cybervictimization positively predicted NSSI (β = 0.24, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.18, 0.29], p < 0.001), and the interaction between negative emotions and friendship quality negatively predicted NSSI (β = −0.16, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.21, −0.12], p < 0.001).

The bias-corrected bootstrap method indicated that the indirect effect of cybervictimization on NSSI, through negative emotion, was moderated by friendship quality, with the index of moderated mediation being −0.04, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.002]. When the level of friendship quality was higher (i.e., 1 SD above the mean), the mediating effect of negative emotions in the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI was not significant, with the index of the mediating effect being −0.001, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.03]. Meanwhile, when the level of friendship quality was lower (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), there was a mediating effect of negative emotions in the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI, with the index of the mediating effect being 0.07, 95% CI [0.03, 0.13].

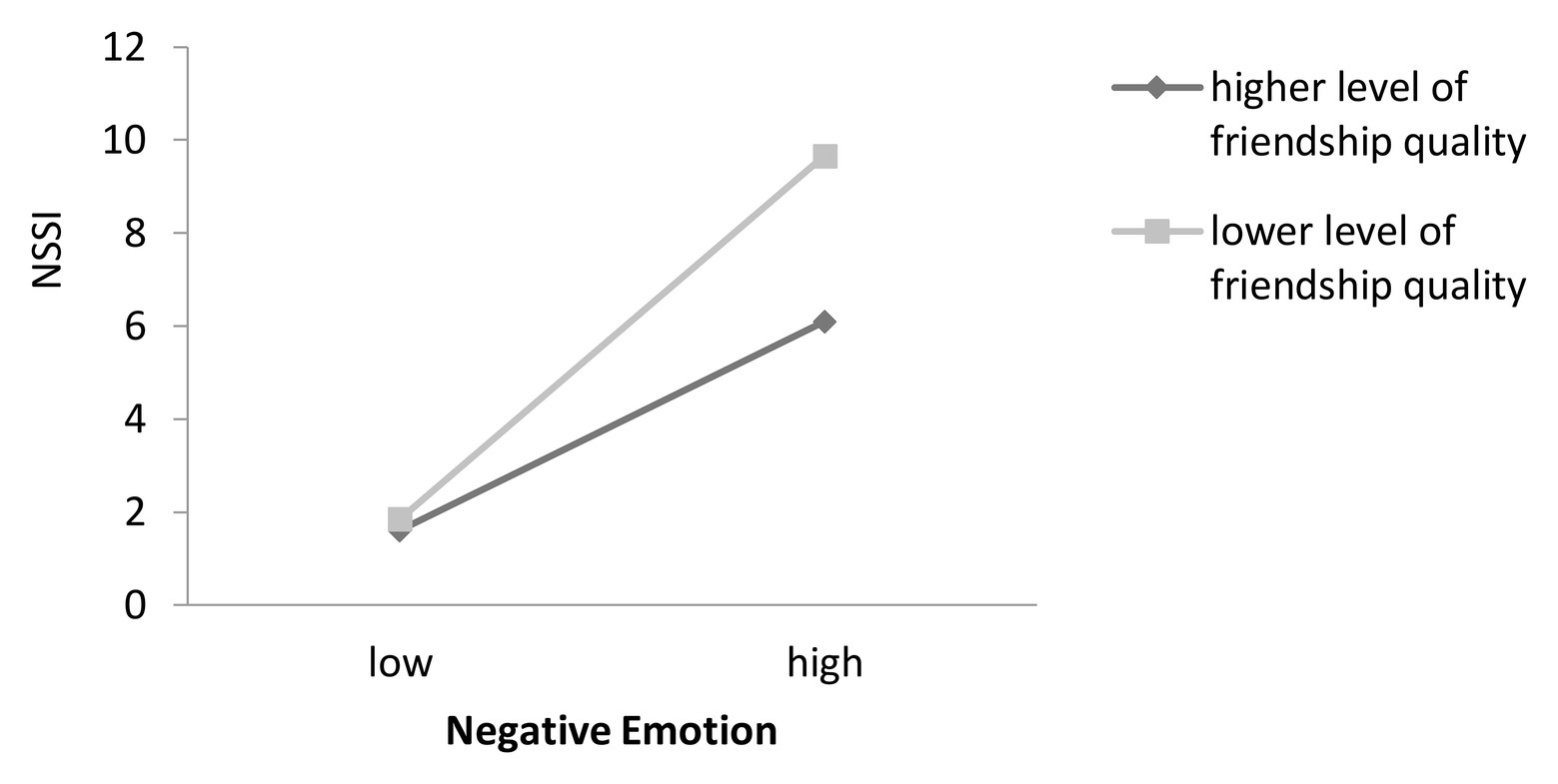

Following the procedures suggested by Aiken and West (1991), the present study examined the predictive effect of negative emotion on NSSI by conducting separate examinations for the high (+1 SD) and lower level of friendship quality in order to illustrate the nature of the moderating effect further. The simple slope test indicated that when friendship quality was higher, higher levels of negative emotion were associated with more NSSI (βsimple = 0.27, p < 0.01). Furthermore, when friendship quality was lower, the effect of negative emotion on NSSI was much stronger (βsimple = 0.37, p < 0.001; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Model of the test for simple slopes showing the moderating influence of friendship quality of the association between negative emotions and NSSI.

Cyberbullying is a form of bullying, which has been found to contribute to stress and mental pressure in those who are victimized by this behavior, and it can lead to numerous psychological and behavior problems, including NSSI (Hay and Meldrum, 2010; Kessel Schneider et al., 2012). NSSI is a maladaptive coping style (Sornberger et al., 2013) that is closely associated with various psychiatric experiences (Honings et al., 2016). To date, cyberbullying has been a relatively understudied public health problem in adolescents (Westers and Culyba, 2018). This study developed and evaluated a moderated-mediation model, to help clarify “how” and “for whom” cybervictimization are associated with NSSI.

Hypothesis 1 stated that negative emotions would mediate the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI. Our study found that cybervictimization was associated with increased negative emotions, which, in turn, was associated with NSSI in our sample of Chinese adolescents. In other words, negative emotions mediated the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI, which supported Hypothesis 1. Thus, an increase in negative emotions may serve as one explanatory mechanism for the relationship between cybervictimization and adolescent engagement in NSSI. As far as we are aware, this study is the first to report such a model. Our research provides support for General Strain Theory (Agnew, 1992), which has proposed that stressors regarding environment stimulation that an individual experiences or their life events are unrelated to NSSI, aggression, and other risky behaviors contribute to the development of depression, anxiety, anger, and other negative emotions. NSSI, aggression, and other risky behaviors are coping mechanisms that are designed to alleviate negative emotions. Cybervictimization serves as a stressor that evokes victims’ negative emotions, leading victims to employ NSSI as a coping strategy.

Our study is also consistent with NSSI’s Experiential Avoidance Theory (Chapman et al., 2006), which suggests that the mechanism leading to the formation of NSSI is a situation that evokes the individual’s negative emotions that leads to individuals perform NSSI as a means of evading or relieving unhappiness emotional experiences. The consequence of NSSI, which is the relief of negative emotions, brings immediate gratification to individuals. This negative reinforcement then strengthens the association between the stimulation of unhappiness and NSSI. Thus, the subsequent experience of unpleasant emotional experiences by an individual leads to NSSI becoming an automatic escape response.

In addition to the mediation results, each of the individual pathways in our mediation model is noteworthy. First, cybervictimization was found to have a significant direct effect on both negative emotions and NSSI. This demonstrates the various negative effects of cybervictimization on adolescents and provides empirical support regarding the harmfulness of cyberbullying. Compared with traditional bully, cyberbullying is easier to reach, as well as allowing invisibility and anonymity (Tokunaga, 2010). If adolescents lack sufficient social support or good psychological adjustment ability, they are more likely to develop psychological and behavior problems. Second, negative emotions are a significant positive predictor for adolescents’ NSSI. The predictive effect of negative emotions on NSSI has been reported in numerous studies, which suggests that NSSI acts as a method for managing emotions (Klonsky, 2007); however, NSSI is unable to resolve all of adolescents’ emotional problems. Wang et al. (2019) found that, although NSSI can relieve the psychological confusion caused by negative emotions, in the long term, NSSI and negative emotions are mutually perpetuating. Thus, if NSSI alleviates the negative emotions caused by repeated cyberbullying over an extended period, the negative emotions and NSSI might begin to mutually reinforce each other.

The present study also confirmed the moderating role of friendship quality in the indirect association between cybervictimization and adolescent NSSI. Specifically, we found that friendship quality attenuated the relationship between negative emotions and NSSI. The regulation of the mediating effect of friendship quality on negative emotions is achieved through regulating the relationship between negative emotion and NSSI. Compared to those adolescents with lower friendship quality, those with high friendship quality who experience being cyberbullied have the relationship between negative emotions and NSSI weakened. Thus, adolescents with high friendship quality are less likely to regulate the negative emotions caused by cybervictimization through NSSI. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Friendship reflects the attachment to a companion through an intimate emotional relationship. Whether in the real world or the virtual world, adolescents express a strong need of belonging (Fabris et al., 2020; Longobardi et al., 2020). For social functioning of adolescents, peer relationships are even greater important than family relationships (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2019). Research has demonstrated that adolescent attachment to a best friend has a stronger relationship to depression, self-esteem, self-ability, and attitudes toward learning better than attachment to a general companion or peer group (Wilkinson, 2010). Adolescents who have good relationships with friends have lower levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and other negative emotions (Woods et al., 2009; Kim, 2015), as well as fewer problem behaviors (Kawabata et al., 2010). Friendship appears to effectively alleviate negative emotions and problem behaviors (Sinanan and Gomes, 2020). The emotional management function of NSSI emphasizes its role in serving to manage negative emotions for the purpose of emotional control (Messer and Fremouw, 2008). When adolescents have high-quality friendships, they are more likely to reduce psychological distress by pouring out or seeking help instead of NSSI. In this sense, emotional support provided by high-quality friendships acts as a more adaptive form of emotional management that can replace nonadaptive coping styles, such as NSSI.

In summary, this study identified a significant moderated-mediation model that explained the effect of cybervictimization on adolescents’ NSSI, which integrated the General Strain Model and the Buffer Model. Our proposed model provides information on the relationship between cybervictimization and adolescents’ NSSI and offers corresponding empirical evidence for theories regarding the experiential avoidance of NSSI along with offering some potential methods for preventing the deleterious consequences of cyberbullying for adolescents. Further, this model addresses the critical issue of “what works for whom,” by revealing that negative emotions area primary mediating mechanisms and adolescent friendship quality is one variable that can account for the heterogeneity in the relationship between cybervictimization and adolescents’ NSSI.

There are several limitations to this study. First, due to the study’s cross-sectional design, we cannot make any causal inferences about observed associations, nor can we reveal the role of developmental factors. Future studies should use longitudinal research to better pinpoint the paths in our theoretical model. Second, although self-report has been widely used in the literature to assess both cybervictimization and NSSI, this method of data collection has some inherent disadvantages, such as strong subjectivity, which could lead to some deviations on data inevitably. Future studies should include multiple methods of data collection (e.g., adolescent, parent, peer, or teacher report) to allow for mutual confirmation and the acquisition of more objective and accurate data. Finally, during adolescence, there are different manifestations of NSSI (Yu, 2013); therefore, future studies should investigate the mechanisms of cybervictimization on different forms of NSSI to obtain more accurate research results.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important practical implications. First, given the universality and harmfulness of cybervictimization for adolescents, we need to emphasize the need to understand the experiences of cybervictimization on adolescents. Intervention and prevention programs should be used as much as possible to reduce cyberbullying (Gaffney et al., 2019). Second, based on the General Strain Model, we verified the mediating effect of negative emotions on the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI. This pathway suggests that by teaching emotional management skills to adolescents who are dealing with cybervictimization, they can learn to effectively deal with the emotional distress caused by the experience of cyberbullying and also prevent the development of problem behaviors. Third, our study found that high-quality friendship can attenuate the influence of negative emotions on NSSI. However, for adolescents, especially in China, tremendous academic pressure can lead to little time to devote to their friendships, and the emphasis on academic competition created challenges for the formation of high-quality friendships. Thus, schools can assist with managing the phenomenon of cyberbullying by promoting adolescent peer relationships and encouraging the cultivation of high-quality friendships. Schaefer et al. (2011) found that involvement in positive extracurricular activities can promote the formation of adolescent friendships and have a positive effect on their psychological health. Perhaps, schools can also consider increasing the diversity of school life beyond academics to further enhance adolescents’ ability to cope effectively with stressful life events.

Although further replication and extension are needed, this study serves as an important step in understanding how cybervictimization is related to adolescent NSSI. Using General Strain Theory and the buffering model of social support, our research constructed a moderated-mediation model and verified the mediating influence of negative emotions on the relationship between cybervictimization and NSSI, and the moderating effect of friendship quality on this mediating effect. This model has not been previously studied, and it helps extend the field’s understanding of the negative effects and mechanism of cybervictimization and identifies possible means of reducing the negative effects of cyberbullying on victims.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB, Institute of Psychology, Hunan Normal University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

YW: substantial contributions to the design of the work, data analysis, and writing. AC: substantial contributions to the design of data analysis and writing. HN: substantial contributions to the design of the work and language polish. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This article was supported by China National Fund for Study Abroad and Foundation of Hunan Educational Committee “The Latent Trajectory Classes of Adolescents’ Self-Injury and Their Causes and Psychological Consequence: An Application of Latent Growth Mixture Modeling” (19A296).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 30, 47–87.

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interaction. London: Sage.

Alexandra, M. T., Helen, M., and Tess, K. (2017). How do people stop non-suicidal self-injury? A systematic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 21, 470–489. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1222319

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th Edn. Washington, DC: APA.

Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E., and Longobardi, C. (2019). Parent and peer attachment as predictors of Facebook addiction symptoms in different developmental stages (early adolescents and adolescents). Addict. Behav. 95, 226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.009

Barrocas, A. L., Giletta, M., Hankin, B. L., Prinstein, M. J., and Abela, J. R. Z. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: longitudinal course, trajectiories, and intrapersonal predictors. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 369–380. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9895-4

Burk, W. J., and Laursen, B. (2005). Adolescent perceptions of friendship and their associations with individual adjustment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 29, 156–164. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000342

Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., and Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005

Chen, Q. Y., Tang, H. Y., Zhang, L., and Zhou, Z. K. (2016). Cyberbullying and its risk factors in chinese adolescents’ usage of social networking sites—based on a survey of 1103 secondary school students. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 3, 89–96.

Chen, W., and Zhang, W. (2004). Factorial and construct validity of the Chinese positive and negative affect scale for student. Chin. Ment. Health J. 18, 763–766. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2004.11.003

Christoffersen, M. N., Møhl, B., DePanfilis, D., and Vanmmen, K. S. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury—does social support make a difference? An epidemiological investigation of a Danish national sample. Child Abuse Negl. 44, 106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.023

Claes, L., Luyckx, K., Baetens, I., de Ven, M. V., and Witteman, C. (2015). Bullying and victimization, depression mood, and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: the moderating role of parental support. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 3363–3371. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0138-2

Fabris, M. A., Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., and Settanni, M. (2020). Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: the role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addict. Behav. 106, 364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364

Fan, C. Y., Wang, Q. Q., Chu, X. W., and Teng, Y. J. (2018). The influencing factors, consequence and educational countermeasures of adolescents’ cyberbullying. Educ. Res. Exp. 3, 93–96.

Feng, Y. (2008). The relation of adolescents’ self-harm behaviors, individual emotion characteristics and family environment factory. Wuhan: Cental China Normal University.

Franks, T. S. (2015). The experiences of adolescents regarding cyberbullying. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., Espelage, D. L., and Ttofi, M. (2019). Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 45, 134–153. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.002

Gandhi, A., Luyckx, K., Maitra, S., and Clae, L. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury and identity distress in Flemish adolescents: exploring gender differences and meditational pathways. Personal. Individ. Differ. 82, 215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.031

Hay, C., and Meldrum, R. (2010). Bullying victimization and adolescent self-harm: testing hypotheses from general strain theory. J. Youth Adolesc. 39, 446–459. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9502-0

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Honings, S., Drukker, M., Groen, S., and van Os, J. (2016). Psychotic experiences and risk of self-injurious behavior in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 46, 237–251. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001841

Hughes, C. D., King, A. M., Kranzler, A., Fehling, K., Miller, A., Lindqvist, J., et al. (2019). Anxious and overwhelming affects and repetitive negative think as ecological predictors of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Cognit. Ther. Res. 43, 88–101. doi: 10.1007/s10608-019-09996-9

Jantzer, V., Haffner, J., Parzer, P., Resch, F., and Kaess, M. (2015). Does parental monitoring moderate the relationship between bullying and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior? A community-based self-report study of adolescents in Germany. BMC Public Health 15:583. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1940-x

Jiang, G. R., Yu, L. X., Zheng, Y., Feng, Y., and Ling, X. (2011). The current status, problems and recommendations on non-suicidal self-injury in China. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 19, 861–873.

Kawabata, Y., Crick, N. R., and Hamaguchi, Y. (2010). Forms of aggression, social-psychological adjustment, and peer victimization in a Japanese sample: the moderating role of positive and negative friendship quality. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 38, 471–484. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9386-1

Kessel Schneider, S., O’Donnell, L., Stueve, A., and Coulter, R. W. S. (2012). Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: a regional census of high school students. Am. J. Public Health 102, 171–177. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300308

Kim, H. H. (2015). School context, friendship ties and adolescent mental health: a multilevel analysis of the Korean youth panel survey (KYPS). Soc. Sci. Med. 145, 209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.002

Kingery, J. N., Erdley, C. A., and Marshall, K. C. (2011). Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents’ adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Q. 57, 215–243. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2011.0012

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 27, 226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002

Klonsky, E. D., and Olino, T. M. (2008). Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: a latent class analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76, 22–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.22

Kwan, G. C. E., and Skoric, M. M. (2013). Facebook bullying: an extension of battles in school. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.014

Li, J. Y. (2015). Cyber bullying vs. traditional bullying: A meta-analysis of differential victimization associate with mental health among adolescent. Chengdu: Sichuan Normal University.

Li, C. Q., Zhang, J. S., Lv, R. R., Duan, J. L., and Lei, Y. T. (2019). Self-harm and its association with bullying victimization among junior high school students in Beijing. Chin. J. Public Health 7, 1–5.

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Fabris, M. A., and Marengo, D. (2020). Follow or be followed: exploring the links between Instagram popularity, social media addiction, cybervictimization, and subjective happiness in Italian adolescents. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 113:104955. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104955

Messer, J., and Fremouw, W. (2008). A critical review of explanatory models for self-mutilating behaviors in adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 162–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.006

Mona, D. (2017). Exploring peer social support as a potential protective factor for self-injuring adolescents. Utah: The University of Utah.

Mounts, N. S. (2002). Parental management of adolescent peer relationships in context: the role of parenting style. J. Fam. Psychol. 16, 58–69. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.58

Nock, M. K., Prinstein, M. J., and Sterba, S. K. (2009). Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118, 816–827. doi: 10.1037/a0016948

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Parker, J. G., and Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Dev. Psychol. 29, 611–621.

Raskauskas, J., and Stoltz, A. D. (2007). Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 43, 564–575. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564

Robinson, K., Brocklesby, M., Garisch, J. A., O’Connell, A., Langlands, R., Russell, L., et al. (2017). Socioeconomic deprivation and non-suicidal self-injury in New Zealand adolescents: the mediating role of depression and anxiety. N. Z. J. Psychol. 46, 126–136.

Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. J., Mero, O., Solera, E., Herrera-López, M., and Calmaestra, J. (2020). Prevalence and psychosocial predictors of cyberaggression and cybervictimization in adolescents: a Spain-Ecuador transcultural study on cyberbulling. PLoS One 15:e0241288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241288

Schaefer, D. R., Simpkins, S. D., Vest, A. E., and Price, C. D. (2011). The contribution of extracurricular activities to adolescent friendships: new insights through social network analysis. Dev. Psychol. 47, 1141–1152. doi: 10.1037/a0024091

Shaw, R. J., Currie, D. B., Smith, G. S., Brown, J., Smith, D. J., and Inchley, J. C. (2019). Do social support and eating family meals together play a role in promoting resilience to bullying and cyberbullying in Scottish school children? SSM Popul. Health 9:100485. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100485

Sho, N., Oiji, A., Konno, C., Toyohara, K., Minami, T., Arai, T., et al. (2009). Relationship of intentional self-harm using sharp objects with depressive and dissociative tendencies in pre-adolescence-adolescence: intentional self-harm in adolescence. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 63, 410–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01959.x

Sinanan, J., and Gomes, C. (2020). “Everybody needs friends”: emotions, social networks and digital media in the friendships of international students. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 23, 674–691. doi: 10.1177/1367877920922249

Sornberger, M. J., Smith, N. G., Toste, J. R., and Heath, N. L. (2013). Non-suicidal self-injury, coping strategies, and sexual orientation. J. Clin. Psychol. 69, 571–583. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21947

Tian, W. W., Yang, C. C., Sun, L. P., and Bian, Y. F. (2018). Influence of interparental conflicts on externalizing problem behaviors in secondary school students: the effects of parent-child relationship and friendship quality. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 26, 532–537. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.025

Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: a critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26, 277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Troop-Gordon, W., Rudolph, K. D., Sugimura, N., and Little, T. D. (2015). Peer victimization in middle childhood impedes adaptive responses to stress: a pathway to depressive symptoms. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 44, 432–445. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.891225

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J. Behav. Med. 29, 377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

van Geel, M., Goemans, A., and Vedder, P. (2015). A meta-analysis on the relation between peer victimization and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res. 230, 364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.017

Wang, Y. L., Chen, H. L., Qin, Y. L., and Lin, X. Y. (2019). The self-punishment function of adolescents’ self-injury: from guilt or shame? Psychol. Dev. Educ. 35, 219–226. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.02.11

Wang, Y. L., Zhang, M. Q., Tan, G. L., and Lin, F. (2020). The relationship between cybervictimization and selfinjury of adolescents: the moderating role of friendship quality and ruminative response. J. Psychol. Sci. 43, 363–370. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200215

Westers, N. J., and Culyba, A. J. (2018). Non-suicidal self-injury: a neglected public health problem among adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 108, 981–983. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304550

Wilkinson, R. B. (2010). Best friend attachment versus peer attachment in the prediction of adolescent psychological adjustment. J. Adolesc. 33, 709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.10.013

Woods, S., Done, J., and Kalsi, H. (2009). Peer victimization and internalizing difficulties: the moderating role of friendship quality. J. Adolesc. 32, 293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.005

You, J., Zheng, C., Lin, M. -P., and Leung, F. (2016). The peer group impulsivity moderated the individual-level relationship between depressive symptoms and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. J. Adolesc. 147, 90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.12.008

Yu, L. X. (2013). "same" in behaviors, different in kinds: The classification of adolescent non-suicidal self-injurers. Wuhan: Central China Normal University.

Keywords: adolescent, non-suicidal self-injury, friendship quality, negative emotion, cybervictimization

Citation: Wang Y, Chen A and Ni H (2021) The Relationship Between Cybervictimization and Non-suicidal Self-Injury in Chinese Adolescents: A Moderated-Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 11:572100. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572100

Received: 22 June 2020; Accepted: 28 December 2020;

Published: 15 February 2021.

Edited by:

Shanmukh V. Kamble, Karnatak University, IndiaReviewed by:

Claudio Longobardi, University of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Wang, Chen and Ni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yulong Wang, eXVsb25nd2FuZzEwN0AxMjYuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.