94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 14 January 2021

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562972

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Psychological and Physiological Benefits of the ArtsView all 84 articles

Child abuse is an underreported phenomenon despite its high global prevalence. This study investigated how child abuse is perceived by children and adolescents as manifested in their drawings and narratives, based on the well-established notion that drawings serve as a window into children’s mental states. A sample of 97 Israeli children and adolescents aged 6–17 were asked to draw and narrate what child abuse meant to them. The drawings and narratives were coded quantitatively. The results indicated that participants did not perceive a distinction between abuse and violence and referred to them interchangeably. Almost half of the participants focused on emotional abuse. The most frequent type of abuse within the family was between parents and children, and the most frequent abuse outside the family was peer victimization. Most of the drawings were figurative and realistic and half of the drawings included words suggestive of the participants’ attempts to be heard and fully understood. The vast majority of drawings did not include the figure of the artist, about a third of the drawings employed dissociative techniques (i.e., included positive objects, were unrelated to abuse, used words alone, or did not follow the instructions), and almost half of the narratives were dissociative or characterized by negative resolution, describing feelings such as sadness, humiliation, and loneliness. These findings suggest the emotional pain associated with the abuse or violence and the use of dissociative mechanisms to bypass the pain. The findings are discussed in light of the literature on children’s disclosure.

Child abuse, which is defined as any act or series of acts of commission or omission by a parent, other caregivers, or a stranger that results in harm, the potential for harm, or the threat of harm to a child (Daphna-Tekoah et al., 2019), is a worldwide phenomenon (Wildeman et al., 2014; Stoltenborgh et al., 2015). In addition, violence against children is hugely prevalent, with more than half of all children worldwide annually exposed to violence in all its forms (Lev-Wiesel et al, 2018). A nationwide study on American youth’s exposure to violence covering conventional crime, child maltreatment, peer and sibling offenses, sexual assault, witnessing, and indirect exposure to violence, and internet offenses revealed that 60% reported at least one form of direct exposure to violence in the past year (Finkelhor et al., 2005). A recent epidemiological survey in Israel that focused on the level of youth’s exposure to the different forms of abuse revealed that 52% reported experiences of abuse at least once during their lifetime (Lev-Wiesel et al., 2019). These victims often suffer multiple and varied forms of abuse (Clemmons et al., 2003; Arata et al., 2005; Finkelhor et al., 2007), within and outside the family, by adults or peers (Oriol et al., 2017). Studies report a higher prevalence of bullying in boys than in girls (Hong and Espelage, 2012). Girls were found to be exposed to a higher incidence of emotional abuse by peers (Seals and Young, 2003). These findings demonstrate that every second child is exposed to any injury.

Yet, despite the high prevalence of child abuse, whether inflicted by a family member, a stranger, or a peer, less than 10% of the children ever disclose the abuse, and about 70% of children are reluctant to disclose it to professionals (Lev-Wiesel and First, 2018). Thus, the prevalence of abuse and its enduring harm and the gap between the prevalence of child maltreatment and disclosure underscores the need to document how children and youth perceive abuse and which abusive behaviors are required to be disclosed to adults according to children and adolescents. Although studies have examined perceptions of child maltreatment among pediatricians (Al-Moosa et al., 2003), social workers (Ashton, 2010), law enforcement officers, educators, and mental health and healthcare professionals (Eisikovits et al., 2015), as well as among teachers (Gamache Martin et al., 2010), much less work has been done on children’s and teens’ perceptions (Lev-Wiesel et al., 2020).

Recently, Lev-Wiesel et al. (2020) compared children’s and parents’ perceptions of child maltreatment and abuse. The findings showed that both parents and children considered sexual, emotional, and physical maltreatment, as well as neglect, as more damaging than child labor. However, children perceived emotional abuse to be significantly more severe than did their parents, and the parents, unlike their children, rated sexual abuse as the most damaging. Built on these preliminary efforts, the current study aimed to shed light on the ways children and adolescents from the general population perceive child abuse, as manifested in their drawings and narratives. Unfolding children’s perception of the abuse may assist therapists, parents, and educators in understanding the ways children experience this disturbing reality. Moreover, if clinicians, parents, and educators want to encourage children to disclose the abuse, they need to comprehend when children perceive violent situations as either abusive or non-abusive.

Empirical and clinical work in art therapy and allied fields has shown that drawings enable the expression of hidden or repressed thoughts and feelings in a relatively fast and straight forward way (Lev-Wiesel and Shvero, 2003; Jacobs-Kayam et al., 2013; Woolford et al., 2013; Snir et al., 2020). Regarding children, researchers and therapists posited that drawings could shed light on children’s internal and outer worlds and their perception of their families and parents in a way that communicates feelings and ideas of their environment (Goldner and Scharf, 2012). According to the authors, colors, shapes, and motifs can all represent the unconscious, ideas, distressful feelings and thoughts, concerns, and worries, adding layers of meaning to verbal content (Lev-Wiesel and Liraz, 2007; Goldner and Scharf, 2012; McInnes, 2019). Recently, researchers in social sciences have suggested that drawings serve as a powerful adjunct to traditional data collection approaches as they advance researchers’ understanding regarding individuals’ perceptions of pathology and well-being (Huss et al., 2012; Boden et al., 2019; Broadbent et al., 2019).

Furthermore, prior studies indicated that drawings could encourage the verbalization of traumatic experiences. Enabling the drawer to become a spectator to his or her negative experience, drawings facilitate the production of a rich, detailed description composed of emotions and facts from a somewhat detached and protected perspective (e.g., Dayton, 2000; Lev-Wiesel and Liraz, 2007). In this respect, clinical and empirical evidence indicates that children’s drawings, particularly those done during a time of crisis, can overcome children’s language limitations (Lev-Wiesel, 1999; Dayton, 2000; McInnes, 2019). For instance, Cohen and Ronen (1999) found that children who had experienced parental divorce reflected their negative experiences in their family drawings. Drawings were shown to enable sexually abused children to provide more details and speak more coherently about what had happened to them, thus enhancing these children’s testimonies (Macleod et al., 2013; Katz et al., 2014, 2018).

Similarly, narratives and the process of generating information through storytelling can shed light on the way meaning is constructed and the ways humans experience the world (Lucius-Hoene and Deppermann, 2000). With traumatic memories, therapists’ consensus is that autobiographical memory of the traumatic events leads to a fragmented narrative (Midgley, 2002; Lev-Wiesel, 2008). However, the reconstruction of a rich, coherent autobiographical memory is essential for healing (Van Minnen et al., 2002). Thus, for example, in narrative exposure therapy, children are requested to describe in detail what happened to them, attentively focused on sounds, smells, feelings, thoughts, and recall. According to researchers, children who have experienced multiple and very severe traumatic events should be treated with narrative approaches. It has been suggested that by habituation to the negative emotions relating to the painful memories, the symptoms of distress might decrease (Neuner et al., 2008; Ruf et al, 2010).

In the current study, we focused on the ways children and youth perceive child abuse through both drawings and narratives. The use of an integrated approach that involves visual, non-verbal, and verbal methods may serve as a venue exploring the multiplicity and complexity of children’s experience (Lev-Wiesel and Liraz, 2007). Thus, each modality substantiated and enriched the other (Boden et al., 2019).

Ninety-seven children and adolescents from the general population (41.2% girls, n = 57, mean age = 9.38, range 6.00–17.00; SD = 2.75) were recruited to this study. The study was a part of a large project conducted in a school setting, which aimed to learn about the perception of child abuse among children and youth (for the demographic variables, see Table 1). After receiving ethical approval from the Committee to Evaluate Human Subject Research of the Faculty of Health Sciences and Social Welfare of the University of Haifa (Number: 122/15), parents received letters explaining the study aims and risks and were asked to sign informed consent forms. Upon parents’ approval, research assistants introduced the project to children and adolescents and asked them to draw “what is child abuse for you” on an A4 (21 × 29.7 cm) sheet of white drawing paper using a set of 12 crayons and a pencil. There was no time limit. They were then asked to provide a written narrative in Hebrew recounting the drawings. Some of the narratives have been translated into English for the purpose of writing this article. Children were not asked to paint or describe a specific experience that had happened to them. However, in case of discomfort, children were assured of getting preliminary assistance from the research team by debriefing their emotions and referring them to school counselors. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their drawings and narratives. Parents were assured that the analysis of the drawings and the narratives would be conducted as a group and that the drawings will be used for research purposes.

The current study applied principles of a multimodal method (for drawings and narratives), the relational mapping interview, which was developed by Boden et al. (2019) to understand the relational context of distress, in this specific case abuse, as manifested in drawings and narratives by children. Incorporating drawing into interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) design provides a vehicle through which the children can communicate their experiences and perceptions. Drawing activates several senses simultaneously, providing data, which in turn sheds light on and reveals the phenomenon. Combining drawings with narratives about what is drawn results in richly nuanced visual and verbal accounts of relational experience. The analysis, therefore, incorporated the visual reflective method of drawing and the narrative into the IPA.

Furthermore, there is extensive mental health, self-defining memory, and art therapy literature on art-based assessments that uses an objective, quantitative approach to measure the frequency of items depicted in various types of drawings and narratives that have been considered indicators of possible emotional problems in non-clinical and clinical populations. These tests incorporate a multiple-sign approach to assist researchers and art therapists in understanding individuals’ mental world (Gantt, 2004; Goldner et al., 2018).

Following these methodological approaches, and based on the literature on child abuse and dissociation (Hetzel and McCanne, 2005; Lev-Wiesel, 2005; Nijenhuis et al., 2010), trauma resolution (Main and Hesse, 1990; Scharf and Shulman, 2006), and self-defining memories (Thorne and McLean, 2002), a quantitative protocol that combined the pictorial features of the drawings with the themes of the narrative was developed. The first two authors carefully examined the drawings and the narratives, identifying common features align with the literature (for the protocol categories and indicators, see Table 2).

The drawings coding system included indicators regarding the content and the style of the drawing. These two dimensions are considered central in investigating art products (Gantt, 2004; Matto and Naglieri, 2005) or art perception (Augustin et al., 2011). Content indicators related to the abuse/violence in the drawings were coded as follows: (1) depiction of a violent/abusive scene in the drawing (yes/no), (2) abuse within the family (yes/no), (3) the relationship between the aggressor and the victim [siblings, parent–child, spouses, other, terror, crime, accident, friends, entire family (including the child), adult (not a parent)–child outside of the family, no abuse], (4) the type of abuse/violence (physical, sexual, emotional, mixed, not specified), and (5) whether the artist is depicted in the drawing (yes/no).

The drawing style was coded using the following indicators: (1) drawing type (figurative/realistic, expressive/metaphoric, no drawing), (2) whether the drawing included words (yes/no), (3) whether the drawing matched the child’s chronological age (yes/no), (4) physical contact between the victim and the aggressor (between the depicted objects) (yes/no), (5) the size of the victim (tiny—the figure is small, about 2 cm, and occupies a small part of the page space; normal—the figure is proportional to the space of the page and the other figures; exaggerated—the figure occupies most of the page space and leaves no room for other objects or its size is not proportional to the other figures; not depicted), (6) the size of the aggressor (tiny, normal, exaggerated, not depicted), (7) overall impression of helplessness in the drawing (yes/no), (8) presence of aggressive symbols manifested in beatings, punches, or threats (yes/no), (9) depictions of injury manifested in blood, pain, tears to represent physical, emotional injury; mixed injuries; none, (11) whether the drawing was pre-schematic, limited, blocked human figures, primitive figures corresponding to ages 4–5 (yes/no), (12) level of vitality, referring to emotional investment in the drawing reflected in embellishment, colorfulness, and details (low, medium, high), (13) whether the drawing included dissociation, was detached, did not address the pain (i.e., included positive objects such as flowers, hearts, or non-related objects; contained only words; or did not follow the instructions, thus bypassing the painful meaning of the abusive scene) (yes/no).

The coding of the narratives’ search for coherence was based on methods described in the literature on trauma resolution (i.e., the extent to which individuals regain emotional and behavioral control and understand how trauma has affected both their inner world and their behavior) (Spooner and Lyddon, 2007; Saltzman et al., 2013). While resolved traumatic memories narratives are rich, specific, and integrative, reflecting individuals’ ability to merge affect and cognition in an optimal manner, chaotic unresolved traumatic memories are confused, excessively detailed, and contradictory and contain themes of failure and subsequent humiliation by caregivers, and restricted dismissing narratives are emotionless, over general, and convey a vague and diffuse sense of self and others (Goldner and Scharf, 2017). The narratives were coded using the following indicators: (1) the role of the artist in the drawing (victim, aggressor, bystander, mixed, no specific role), (2) presence of dissociation (i.e., the narrative does not concentrate on the violence or abuse, is detached, does not address the pain), (3) narrative organization coherent/organized, restricted—the inability to describe the event, chaotic/flooded—incoherent, flooded with detail description (3) central theme (child’s anxiety, dread, helplessness, and powerlessness/child’s humiliation, sadness, loneliness, guilt, and shame/mother’s helplessness, loneliness, and sadness/the child getting stronger as a result of the incident/narrow avoidant description without emotion, no reference to the abuse), (4) resolution of the narrative (positive, negative, no solution, neutral), and (5) whether the content of the drawing coincided with the content of the narrative (yes/no). The drawings and narratives were coded together by the first two authors, who are experts in art-based assessments. Disagreements were resolved through consensus.

A series of chi-square analyses was performed to identify differences in drawings and narratives across boys and girls and age groups. Data indicated that boys depicted more tiny victims (41.9%) compared to girls (12.8%), [χ2(2) = 8.99, p = 0.01] and used more preschematic drawings (53.8%) compared to girls (31.6%), [χ2(1) = 4.76, p = 0.03]. Girls depicted more vital drawings (42.1%) compared to boys (15.1%), [χ2(2) = 3.10, p = 0.02]. However, they produced more negative narratives (66.7%) compared to boys (30%), [χ2(2) = 12.44, p = 0.00]. Elementary-school-aged children depicted more helplessness drawings (69.6%) compared to adolescents (45.9%), [χ2(1) = 3.92, p = 0.04] and produced more neutral resolution (37.1%), [χ2(2) = 6.90, p = 0.03] compared to adolescents, who generated more positive narratives (34.8%).

Children from families with two parents who were not divorced used less dissociative mechanisms in their drawings (31.4%) compared to children from divorced or single-parent families (78.6%), [χ2(1) = 11.2, p = 0.00] and their drawings coincided more with the narrative (92.7%) compared to children from divorced or single-parent families (42.9%), [χ2(1) = 23.88, p = 0.00]. Children from families with high socioeconomic status tended to depict more abuse/violence scenes within the family (88%) compared to children from families with low (24.2%) or median (57.9%) socioeconomic status [χ2(2) = 14.50, p = 0.00]. The most frequent type of abuse/violence depicted by children from families with high socioeconomic status was between siblings (50%), while the most frequent type of abuse/violence depicted by children from families with low and medium socioeconomic status was between friends (31, 14%, respectively) [χ2(14) = 33.69, p = 0.00]. Adolescents’ drawings incorporated more emotional injury symbols (47.8%) compared to drawings of elementary-school-aged children, which incorporated more symbols of physical injury (58.1%), [χ2(3) = 8.53, p = 0.04].

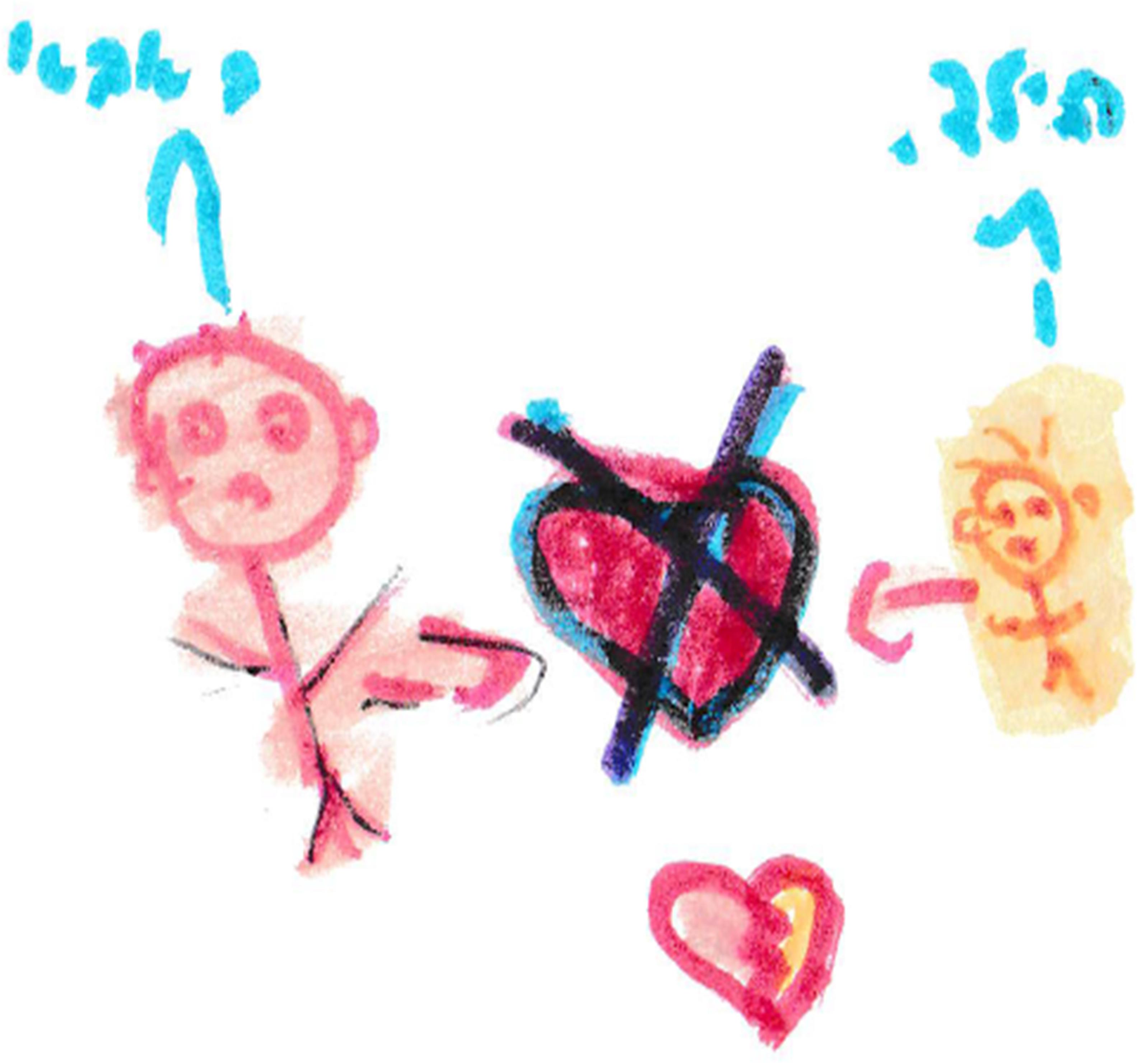

As shown in Table 2, most of the drawings were either figurative or realistic (85.6%) and included an abusive/violent scene (86.6%). Almost half of the drawings focused on emotional abuse (40.2%). About half of the participants depicted abuse within the family (51.5%), and the most frequent type of violence depicted was between parents and children (16.5%) or between siblings (18.6%). The most frequent category of violence outside the family was between friends (18.6%) (see Figures 1, 2). The vast majority of participants did not include themselves in the drawings (81.4%). More than half of the drawings did incorporate symbols of aggression (61.9%) and almost half of the drawings included injury symbols (46.4%). About a third of the drawings involved dissociative techniques (61.9%). About half of the drawings were preschematic (40.2%) and included words (47.4%) (for examples, see drawings and narratives in Figures 3, 4). Most of the narratives were consistent with the drawings (85.4%). Approximately a quarter (28.1%) of the narratives described the child as exposed to direct violence as either victim or aggressor, while in the rest of the narratives the child did not have a specific role or was exposed to indirect violence as a bystander. About half of the narratives were coherently organized (43.7%), whereas the rest were either restricted (37.5%) or chaotic (18.8%), revealing dissociation, distress, sadness, and loneliness.

Figure 1. An example of drawing and narrative of parent-child abuse drawn by a child. “A father and son. The father hit the son and then the son feels that the father doesn’t love him. The child has a broken heart and feels a lack of love”.

Figure 2. An example of a drawing of peer abuse drawn by a child. “One child made fun of me because I am fat and then all the children in the class made fun of me, and every day I got sick with a different disease. All the children in the class realized it was wrong, and said they were sorry. They gave me candies to apologize”.

Figure 3. An example of dissociation within the drawing, drawn by a child. “A family of clouds. This is mom and this is dad and here are flowers and more flowers, and they go outside and pick flowers”.

Figure 4. An example of dissociation within the drawing and narrative created by a child. The participant refused to follow instructions to draw what he thought was child abuse. He/she asked if he/she could draw the opposite of violence and something that appealed to him/her. He/she chose to draw a rainbow and said that his/her painting was called a “Rainbow of Peace”.

Chi-square analyses were conducted to identify differences in the participants’ drawings and narratives according to the type of abuse/violence. As can be seen in Table 3, the analyses revealed differences in relation to the presence of a violent scene, physical contact between the victim and the aggressor, the inclusion of aggressive symbols, and dissociation within the drawings and narratives. In particular, violent scenes, physical contact between the victim and the aggressor, and aggressive symbols were present in drawings containing multiple forms of abuse or physical abuse as compared to only emotional or only sexual abuse (for examples, see drawings in Figures 5, 6). More dissociations within the drawings and narratives were depicted when the type of abuse was not specified, as compared to sexual, physical, or emotional abuse (see Table 3).

Figure 5. An example of a drawing with symbols of hurt drawn by a child. “Dad says ‘You’re a bad boy’ and the boy cries and says ‘Dad, enough.’ This is emotional abuse, not physical, I’ve drawn emotional abuse.” The child in the drawing is not the artist; it is meant to represent any child.

Figure 6. An example of a drawing with aggression symbols and a helplessness narrative created by an adolescent. “I painted a dad who beats his kid, I don’t know why. I painted a bear, I don’t know, it doesn’t matter to the teddy bear. You see that the father is sad and the boy is crying, that hurts him. Usually, domestic violence doesn’t really happen, it’s more school violence. In this house, for example, one of the parents got upset or something, or was angry and said something insulting: I don’t want to bring you up, why were you born? After this quarrel they don’t really mean it, it’s just, you don’t really have to do it because after that you can see the child lying in bed and doing nothing. This once happened to me, I’m sorry to say”.

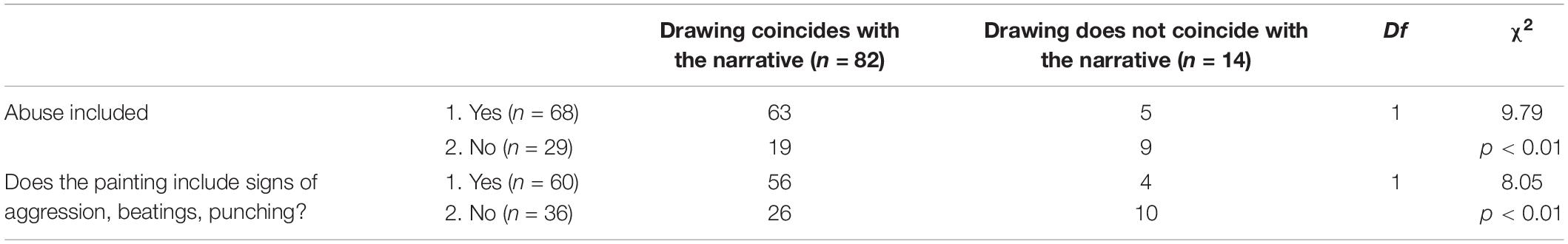

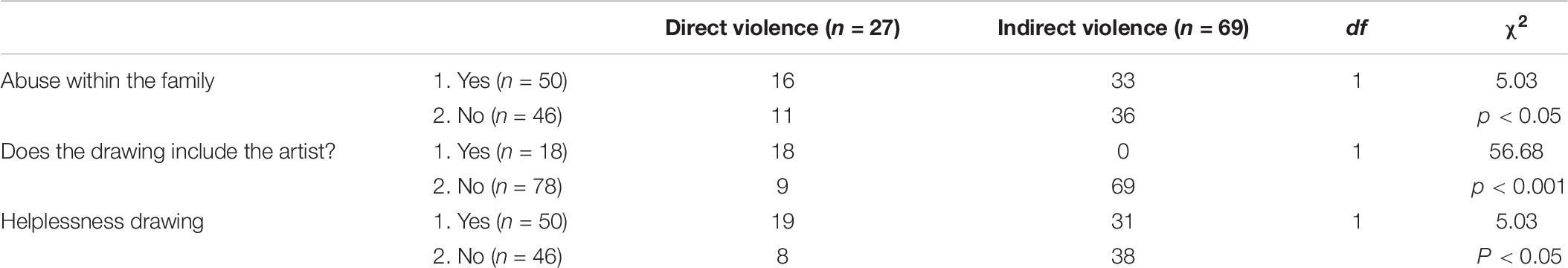

Chi-square analyses were conducted to identify the associations in the participants’ drawings and narratives. The analyses revealed correlations between the extent to which the drawing was consistent with the narrative and the presence of violent scenes or aggressive symbols. More violent scenes and aggressive symbols were found in the drawings when the narrative was consistent with the drawing compared to narratives that departed from the drawing (see Table 4). Correlations were also found between the presence of dissociative narratives and dissociative drawings that included the self in the drawings and scenes of abuse. In almost all the dissociative narratives, self-figures were not included as compared to the non-dissociative narratives. Almost two-thirds of the dissociative narratives were associated with dissociative drawings that did not include abusive or violent scenes (see Table 5). Finally, the narrative resolution was correlated with the presence of injury or the role of the self-figure in the drawing. Specifically, more symbols of emotional or physical injury were present in both positive and negative narrative resolutions compared to narratives with a neutral resolution. Similarly, more children depicted themselves as victims or aggressors when the resolution was either negative or positive as compared to narratives with neutral resolutions (see Table 6). Finally, children whose narratives discussed direct exposure to violence tended to include the artist in the drawing, to depict a higher rate of violent scenes within the family, and to depict helplessness in the drawings. By contrast, none of the children or adolescents who narrated stories on indirect exposure to violence depicted the artist in the drawings. These children and adolescents also depicted a higher rate of violent scenes out of the family or no violent scenes in their drawings, and a smaller percentage of their drawings depicted helplessness (see Table 7).

Table 4. Associations between drawing characteristics and match between the drawing and the narrative.

Table 7. Associations between direct and indirect violence in narratives and drawings characteristics.

The current study examined how children and adolescents from the general population perceive child abuse as reflected in drawings and narratives. In general, the findings indicated that the children did not perceive a distinction between abuse and violence and referred to them interchangeably, referring equally to intrafamilial and extrafamilial scenes of child abuse and violence. The most frequent form of abuse depicted by the participants was emotional abuse. This is consistent with previous findings indicating a higher prevalence of emotional abuse reported by children and adolescents than other forms of abuse (Lev-Wiesel et al., 2019). Because emotional abuse often accompanies other forms of abuse, whether intrafamilial or extrafamilial, children and adolescents may be more familiar with it. It is consistent with previous findings showing that many children experience and engage in hostility, teasing, bullying, yelling, criticism, rejection, and ostracism, whether as indirect victims or observers, as victims, or as perpetrators (Nansel et al., 2001; Modecki et al., 2014; Stark, 2015).

Although violent engagement between peers or siblings is common (Nansel et al., 2001; Tucker et al., 2013; Modecki et al., 2014; Wolke et al., 2015), the participants here did not appear to consider these interactions as acceptable but rather as abusive/violent acts, in which there were clear roles of victim and perpetrator. These imbalanced situations can exacerbate feelings of embarrassment, humiliation, sadness, loneliness, and helplessness, which were reflected here in the children’s powerlessness drawings and narratives, as well as in their restricted and chaotic narratives, which may imply children’s difficulties in reflecting and resolving the abuse (Main and Hesse, 1990; Scharf and Shulman, 2006). This raises the more general question of the impact of exposure to violence—whether domestic, in the community, or in the media—on children and how it shapes their views of the world and themselves, their ideas about the meaning and purpose of life, their expectations for future happiness, and their moral development (Cummings et al., 2009).

Most of the drawings communicated the abusive/violent experience realistically through the use of symbols of aggression, injuries, and words, particularly the drawings that depicted physical abuse or multiple forms of abuse. This finding lends weight to previous studies indicating that drawings encourage disclosure of disturbing content that can elevate distress by bypassing dissociative mechanisms (Amir and Lev-Wiesel, 2007). The fact that none of the participants avoided or refrained from completing the assignment, but some employed various graphical techniques such as receding themselves from the situation by seldom drawing themselves within the abusive scene, avoiding taking a specific role in the event, or distancing the aggressor from the victim, may indicate an attempt to protect themselves from the troubling subject and its associated negative feelings by dissociative mechanisms. Furthermore, despite the high prevalence of sexual assault among children (Oriol et al., 2017; Lev-Wiesel et al, 2018), children and adolescents rarely drew this type of assault.

Obviously, some of the children and adolescents could have served as the aggressors, perpetrators of bullying, or bystanders (Nansel et al., 2001); however, using these techniques, as well as adding positive objects such as flowers or hearts, non-related objects, or words, may also reflect the participants’ ambivalence toward contemplating on the subject or disclosing their personal abusive experience (Malloy et al., 2011; Lev-Wiesel et al, 2018). The use of excessive cuteness or sweetness in drawings as a dissociative mechanism previously was found in various studies that aimed to identify attachment representations in children (e.g., Pianta and Longmaid, 1999; Goldner and Scharf, 2012). Specifically, children characterized by disorganized attachment representation tended to add hearts, flowers, and butterflies to their drawings, and these objects tended to take over much of the page.

The dissociation literature considers dissociation as both a symptom of distress and a defense mechanism that can lead to distress (Nijenhuis et al., 2010; Lahav and Elklit, 2016). The classical approach regards dissociation as a pathological response to trauma in which the victim splits daily reality into the part in which he or she functions appropriately and the abuse experience (Nijenhuis et al., 2010). The two parts of the self, the one that acknowledges the harm and the one that detached itself from it, are thought to be separated on a different level of consciousness (Nijenhuis et al., 2010). However, it is essential to note that using dissociative mechanisms in the narratives and drawings should be regarded as a normative adjustment mechanism since it protects individuals who have undergone painful experiences from emotional flooding (Spiegel et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2013).

Children can be exposed to indirect victimization across multiple socio-ecological contexts, including in the neighborhood, school, and home. Jakob (2018) suggested that even children who do not directly observe domestic or community violence are often aware of violent events or hear repeated accounts of a specific incident and tend to form mental imagery of the violence (Bacchini and Esposito, 2020). In our study, three-quarters of our sample generated narratives of exposure to indirect violence. Data from surveys conducted in the United States showed that more than 58% of the children and adolescents had witnessed or experienced indirect violence, including exposure to war or ethnic conflict, rape, flashing, domestic violence, kidnapping, witnessing a murder, and dating violence (Finkelhor et al., 2007, 2010). Even though the scenes of children who narrated indirect violence narratives tended to involve violence occurring mostly outside the family and their drawings tended to depict less helplessness than those of children who produced narratives of direct exposure to violence, studies have documented harmful effects of indirect exposure to violence, including PTSD symptoms, depression, externalizing problems, and delinquency (Fleckman et al., 2016; Shukla and Wiesner, 2016; Gollub et al., 2019). Thus, the choice to draw indirect violence scenes can attest not only to the high prevalence of the phenomenon in children and adolescents but also to the way children emotionally protect themselves from the consequences of indirect violence and the mental pain involved.

Our study also revealed differences in the children’s drawings and narratives across genders, family structures, and socioeconomic statuses. While boys tended to draw smaller victims and use preschematic drawings, girls produced more vital drawings but negative narratives. These tendencies replicated prior studies that indicated girls’ disposition to depict more expressive metaphorical drawings using a broader range of colors and boys’ tendency to depict more simple and plain drawings (Deaver, 2009; Picard and Boulhais, 2011; Goldner and Levi, 2014). The smaller victim figures in boys’ drawings and the negative narratives of girls can be understood based on boys’ higher rate of physical aggression and girls’ higher rate of emotional aggression, perceived risk of victimization (Carbone-Lopez et al., 2010), and emotional distress (Dao et al., 2006).

In addition, children from families with two parents who were not divorced, and families with higher socioeconomic status tended to use less dissociative mechanisms in their drawings. They drew more abuse scenes (mostly between siblings), and their drawings accorded their narratives. These findings may indicate these children’s higher level of accessibility to the abusive experience and broader internal and external resources to approach the task without bypassing it. Note, however, that other reasons can explain children’s emotional detachment from the drawings, such as their desire to engage with the concept more cognitively and personal predispositions (e.g., personality traits or attachment tendency). Future studies might examine these reasons.

The findings of this study may shed light on the ways children and adolescents perceive child abuse, their concerns, and the ways they try to cope or avoid coping with the distress. Abuse (or a combination of abuse and/or violence, as they perceived it), either within or outside the family, left most of the children feeling lonely and defenseless. Struggling with feelings of humiliation, guilt, and shame, they tried to communicate the abuse/violence, depicting realistic violent scenes, injury, aggressive symbols, and words in an attempt to gain an understanding for the painful experience. Clearly, for some children, art-making accompanied by producing narratives enables a concretization of the abusive experience (Buk, 2009; Loumeau, 2011) as well as its externalization into tangible symbols and narratives, which might support the containment and processing of the event (Avrahami, 2006; Malchiodi, 2012). However, for some children, this task may be perceived as anxiety-provoking and overwhelming, which evokes a more defensive response than would maintaining greater emotional distance (Kaiser, 1996). Since clinicians consider that art-based interventions and drawing techniques facilitate disclosure and foster sharing (Bekhit et al., 2005; Leon et al., 2007), they should be aware of the complexity of asking their clients to produce this type of drawing and the mechanisms children/teens use to cope with evoked distressful feelings.

This study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration. First, the research design was observational and correlative; therefore, it does not allow for causal inference. Second, the study was composed of a small convenience sample of Israeli children and teens who depicted the ways they perceived abuse. Future studies aiming to replicate the findings should apply a representative larger sample. Finally, our findings concentrated on drawings and narrative analyses. Future studies should include additional measures such as self-report questionnaires on children’s adjustment or in-depth interviews to validate the findings and gain a deeper understanding of children’s perceptions of abuse and violence. In addition, personal variables such as the history of trauma and child abuse, emotional regulation, and attachment orientations could also moderate the analysis or shed light on the participants’ perceptions as reflected in their drawings and narratives.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Committee to Evaluate Human Subject Research of the Faculty of Health Sciences and Social Welfare of the University of Haifa. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

LG and RL-W analyzed the drawings and data. All authors were involved in writing the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Al-Moosa, A., Al-Shaiji, J., Al-Fadhli, A., Al-Bayed, K., and Adib, S. M. (2003). Pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes and experience regarding child maltreatment in Kuwait. Child Abuse Neglect 27, 1161–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.009

Amir, G., and Lev-Wiesel, R. (2007). Dissociation as depicted in the traumatic event drawings of child sexual abuse survivors: a preliminary study. Arts Psychotherapy 34, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2006.08.006

Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., and O’Farrill-Swails, L. (2005). Single versus multi-type maltreatment: an examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 11, 29–52. doi: 10.1300/j146v11n04_02

Ashton, V. (2010). Does ethnicity matter? social workers’ personal attitudes and professional behaviors in reporting child maltreatment. Adv. Soc. Work 11, 129–143. doi: 10.18060/266

Augustin, M. D., Defranceschi, B., Fuchs, H. K., Carbon, C. C., and Hutzler, F. (2011). The neural time course of art perception: an ERP study on the processing of style versus content in art. Neuropsychologia 49, 2071–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.03.038

Avrahami, D. (2006). Visual art therapy’s unique contribution in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders. J. Trauma Dissociat. 6, 5–38. doi: 10.1300/j229v06n04_02

Bacchini, D., and Esposito, C. (2020). “Growing up in violent contexts: differential effects of community, family, and school violence on child adjustment,” In Children and Peace. Peace Psychology Book Series, eds Balvin N, and Christie D, (Cham: Springer).

Bekhit, N. S., Thomas, G. V., and Jolley, R. P. (2005). The use of drawing for psychological assessment in Britain: survey findings. Psychol. Psychotherapy: Theory Res. Practice 78, 205–217. doi: 10.1348/147608305x26044

Boden, Z., Larkin, M., and Iyer, M. (2019). Picturing ourselves in the world: drawings, interpretative phenomenological analysis and the relational mapping interview. Qual. Res. Psychol. 16, 218–236. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2018.1540679

Broadbent, E., Schoones, J. W., Tiemensma, J., and Kaptein, A. A. (2019). A systematic review of patients’ drawing of illness: implications for research using the common sense model. Health Psychol. Rev. 13, 406–426. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2018.1558088

Buk, A. (2009). The mirror neuron system and embodied simulations: clinical implications for art therapists working with trauma survivors. Arts Psychotherapy 36, 61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2009.01.008

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F. -A., and Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence Juvenile Justice 8, 332–350. doi: 10.1177/1541204010362954

Clemmons, J. C., DiLillo, D., Martinez, I. G., DeGue, S., and Jeffcott, M. (2003). Co-occurring forms of child maltreatment and adult adjustment reported by Latina college students. Child Abuse Neglect 27, 751–767. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00112-1

Cohen, O., and Ronen, T. (1999). Young children’s adjustment to their parents’ divorce as reflected in their drawings. J. Divorce Remarriage 30, 47–70. doi: 10.1300/j087v30n01_04

Cummings, E. M., El-Sheikh, M., Kouros, C. D., and Buckhalt, J. A. (2009). Children and violence: the role of children’s regulation in the marital aggression-child adjustment link. Clin. Child Family Psychol. Rev. 12, 3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0042-7

Dao, T. K., Kerbs, J. J., Rollin, S. A., Potts, I., Gutierrez, R., Choi, K., et al. (2006). The association between bullying dynamics and psychological distress. J. Adolescent Health 39, 277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.001

Daphna-Tekoah, S., Lev-Wiesel, R., Israeli, D., and Balla, U. (2019). A novel screening tool for assessing child abuse: the medical somatic dissociation questionnaire–MSDQ. J. Child Sexual Abuse 28, 526–543. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2019.1581868

Deaver, S. P. (2009). A normative study of children’s drawings: preliminary research findings. Art Therapy 26, 4–11. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2009.10129309

Eisikovits, Z., Davidov, J., Sigad, L., and Lev-Wiesel, R. (2015). “The social construction of disclosure: the case of child abuse in Israeli society,” in Mandatory Reporting Laws and the Identification of Severe Child Abuse and Neglect, eds B. Mathews, D.C. Bross, (New York, NY: Springer), 395–413. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9685-9_19

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R., Turner, H., and Hamby, S. L. (2005). The victimization of children and youth: a comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment 10, 5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., and Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimization: a neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse Neglect 31, 7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., and Hamby, S. L. (2010). Trends in childhood violence and abuse exposure: evidence from 2 national surveys. Arch. Pediatr. Adolescent Med. 164, 238–242. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.283

Fleckman, J. M., Drury, S. S., Taylor, C. A., and Theall, K. P. (2016). Role of direct and indirect violence exposure on externalizing behavior in children. J. Urban Health 93, 479–492. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0052-y

Gamache Martin, C., Cromer, L. D., and Freyd, J. J. (2010). Teachers’ beliefs about maltreatment effects on student learning and classroom behavior. J. Child Adolescent Trauma 3, 245–254. doi: 10.1080/19361521.2010.523061

Gantt, L. (2004). The case for formal art therapy assessments. Art Therapy 21, 18–29. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2004.10129322

Goldner, L., and Levi, M. (2014). Children’s family drawings, body perceptions, and eating attitudes: the moderating role of gender. Arts Psychotherapy 41, 79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.11.004

Goldner, L., Sachar, S. C., and Abir, A. (2018). Adolescents’ rejection sensitivity as manifested in their self-drawings. Art Therapy 35, 25–34. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2018.1459103

Goldner, L., and Scharf, M. (2012). Children’s family drawings and internalizing problems. Arts Psychotherapy 39, 262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.04.005

Goldner, L., and Scharf, M. (2017). Individuals’ self-defining memories as reflecting their strength and weaknesses. J. Psychol. Counsellors Schools 27, 153–167. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2016.32

Gollub, E. L., Green, J., Richardson, L., Kaplan, I., and Shervington, D. (2019). Indirect violence exposure and mental health symptoms among an urban public-school population: prevalence and correlates. PLoS One 14:e0224499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224499

Hetzel, M. D., and McCanne, T. R. (2005). The roles of peritraumatic dissociation, child physical abuse, and child sexual abuse in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder and adult victimization. Child Abuse Neglect 29, 915–930. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.008

Hong, J. S., and Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: an ecological system analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 17, 311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Huss, E., Nuttman-Shwartze, O., and Altman, A. (2012). The role of collective symbols as enhancing resilience in children’s art. Arts Psychotherapy 39, 52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.11.005

Jacobs-Kayam, A., Lev-Wiesel, R., and Zohar, G. (2013). Self-mutilation as expressed in self-figure drawings in adolescent sexual abuse survivors. Arts Psychotherapy 40, 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.11.003

Jakob, P. (2018), Multi-stressed families, child violence and the larger system: an adaptation of the nonviolent model. Journal of Family Therapy, 40, 25–44. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.12133

Kaiser, D. H. (1996). Indications of attachment security in a drawing task. Arts Psychotherapy 23, 333–340. doi: 10.1016/0197-4556(96)00003-2

Katz, C., Barnetz, Z., and Hershkowitz, I. (2014). The effects of drawing on children’s experiences in investigations following alleged child abuse. Child Abuse Neglect 38, 858–867. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.003

Katz, C., Klages, A. L., and Hamama, L. (2018). Forensic interviews with children: exploring the richness of children’s drawing and the richness of their testimony. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 94, 557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.034

Lahav, Y., and Elklit, A. (2016). The cycle of healing - dissociation and attachment during treatment of CSA survivors. Child Abuse Neglect 60, 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.009

Leon, K., Wallace, T., and Rudy, D. (2007). Representations of parent–child alliances in children’s family drawings. Soc. Dev. 16, 440–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00392.x

Lev-Wiesel, E., Massrawa, M., and Binson, B. (2020). Parents’ and children’s perceptions of child maltreatment. J. Soc. Work 20:16.

Lev-Wiesel, R. (1999). The use of the machover draw-a-person test in detecting adult survivors of sexual abuse: a pilot study. Am. J. Art Therapy 37:106.

Lev-Wiesel, R. (2005). Dissociative identity disorder as reflected in drawings of sexually abused survivors. Arts Psychotherapy 32, 372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2005.02.003

Lev-Wiesel, R. (2008). Child sexual abuse: a critical review of intervention and treatment modalities. Child. Youth Services Rev. 30, 665–673. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.01.008

Lev-Wiesel, R., Eisikovits, Z., First, M., Gottfried, R., and Mehlhausen, D. (2018). Prevalence of child maltreatment in Israel: a national epidemiological study. J. Child. Adoles. Trauma. 11, 141–150. doi: 10.1007/s40653-016-0118-8

Lev-Wiesel, R., First, M., Gottfried, R., and Eisikovits, Z. (2019). Reluctance versus urge to disclose child maltreatment: the impact of multi-type maltreatment. J. Int. Violence 34, 3888–3914. doi: 10.1177/0886260516672938

Lev-Wiesel, R., and First, M. (2018). Willingness to disclose child maltreatment: CSA vs other forms of child abuse in relation to gender. Child Abuse Neglect 79, 183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.010

Lev-Wiesel, R., and Liraz, R. (2007). Drawings vs. narratives: drawing as a tool to encourage verbalization in children whose fathers are drug abusers. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 12, 65–75. doi: 10.1177/1359104507071056

Lev-Wiesel, R., and Shvero, T. (2003). An exploratory study of self-figure drawings of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Arts Psychotherapy 30, 13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4556(02)00232-0

Loumeau, L. (2011). “Art therapy with traumatically bereaved children,” in Trauma: Contemporary Directions in Theory, Practice, and Research, eds S. Ringel, and J. Brandell (Los Angeles, CA: Sage).

Lucius-Hoene, G., and Deppermann, A. (2000). Narrative identity empiricized: a dialogical and positioning approach to autobiographical research interviews. Narrat. Inquiry 10, 199–222. doi: 10.1075/ni.10.1.15luc

Macleod, E., Gross, J., and Hayne, H. (2013). The clinical and forensic value of information that children report while drawing. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 27, 564–573.

Main, M., and Hesse, E. (1990). “Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism?,” in Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention eds M. T. Greenberg, and D. Cicchetti. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Malchiodi, C. (2012). “Art therapy with combat veterans and military personnel,” In Handbook of Art Therapy, (Ed.) C. M. Malchiodi, (New York, NY: Guilford Malloy).

Malloy, L. C., Brubacher, S. P., & Lamb, M. E. (2011). Expected consequences of disclosure revealed in investigative interviews with suspected victims of child sexual abuse. Applied Developmental Science, 15, 8–19. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.538616

Matto, H. C., and Naglieri, J. A. (2005). Race and ethnic differences and human figure drawings: clinical utility of the DAP: SPED. J. Clin. Child Adolescent Psychol. 34, 706–711. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_12

McInnes, E. (2019). “Young children’s drawings after sexual abuse: disclosure and recovery,” in Where to From Here? Examining Conflict-related and Relational Interaction Trauma, (ed.) E. McInnes (Netherlands: Brill Rodopi.

Midgley, N. (2002). “Child dissociation and its roots in adulthood,” in Attachment, Trauma and Multiplicity, ed. V. Sinason (New York, NY: Brunner-Rutledge), 37–51.

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., and Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J. Adolescent Health 55, 602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., and Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 285, 2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094

Neuner, F., Catani, C., Ruf, M., Schauer, E., Schauer, M., and Elbert, T. (2008). Narrative exposure therapy for the treatment of traumatized children and adolescents (KidNET): from neurocognitive theory to field intervention. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatric Clin. N. Am., 17, 641–664. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.03.001

Nijenhuis, E., van der Hart, O., and Steele, K. (2010). Trauma-related structural dissociation of the personality. Act. Nervosa Superior 52, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/bf03379560

Oriol, X., Miranda, R., Amutio, A., Acosta, H. C., Mendoza, M. C., and Torres-Vallejos, J. (2017). Violent relationships at the social-ecological level: a multi-mediation model to predict adolescent victimization by peers, bullying and depression in early and late adolescence. PLoS One 12:e0174139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174139

Pianta, R. C., and Longmaid, K. (1999). Attachment-based classifications of children’s family drawings: psychometric properties and relations with children’s adjustment in kindergarten. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 28, 244–255. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_11

Picard, D., and Boulhais, M. (2011). Sex differences in expressive drawing. Personal. Individ. Diff. 51, 850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.017

Ruf, M., Schauer, M., Neuner, F., Catani, C., Schauer, E., and Elbert, T. (2010). Narrative exposure therapy for 7-to 16-year-olds: a randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. J. Traumat. Stress 23, 437–445. doi: 10.1002/jts.20548

Saltzman, W. R., Pynoos, R. S., Lester, P., Layne, C. M., and Beardslee, W. R. (2013). Enhancing family resilience through family narrative co-construction. Clin. Child Family Psychol. Rev. 16, 294–310. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0142-2

Scharf, M., and Shulman, S. (2006). “Intergenerational transmission of experiences in adolescence: the challenges of parenting adolescents,” in Parenting Representations, (Ed.) O. Mayseless. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Seals, D., and Young, J. (2003). Bullying and victimization: prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence 38, 735–747.

Shukla, K., and Wiesner, M. (2016). Relations of delinquency to direct and indirect violence exposure among economically disadvantaged, ethnic-minority mid-adolescents. Crime Delinquency 62, 423–445. doi: 10.1177/0011128713495775

Snir, S., Gavron, T., Maor, Y., Haim, N., and Sharabany, R. (2020). Friends’ closeness and intimacy from adolescence to adulthood: art captures implicit relational representations in joint drawing: a longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 11:2842. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573140

Spiegel, D., Loewenstein, R. J., Lewis-Ferna’ndez, R., Sar, V., Simeon, D., Vermetten, E., et al. (2011). Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Depress. Anxiety 28, 824–852.

Spooner, L. C., and Lyddon, W. J. (2007). Sandtray therapy for inpatient sexual addiction treatment: an application of constructivist change principles. J. Construct. Psychol. 20, 53–85. doi: 10.1080/10720530600992782

Stark, S. (2015). “Emotional abuse,” in Emotional abuse. Psychology & Behavioral Health, (Ed.) Moglia, P 4th ed. (Amenia, NY: Salem Press at Greyhouse Publishing). doi: 10.1300/j135v01n04_04

Stein, D. J., Koenen, K. C., Friedman, M. J., and Kessler, R. C. (2013). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 302–312.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R., and van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Rev. 24, 37–50. doi: 10.1002/car.2353

Thorne, A., and McLean, K. C. (2002). Gendered reminiscence practices and self-definition in late adolescence. Sex Roles 46, 267–277.

Tucker, C. J., Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A. M., and Turner, H. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of sibling victimization types. Child Abuse Neglect 37, 213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.01.006

Van Minnen, A., Wessel, I., Dijkstra, T., and Roelofs, K. (2002). Changes in PTSD patients’ narratives during prolonged exposure therapy: a replication and extension. J. Traumat. Stress 15, 255–258. doi: 10.1023/A:1015263513654

Wildeman, C., Emanuel, N., Leventhal, J. M., Putnam-Hornstein, E., Waldfogel, J., and Lee, H. (2014). The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatrics 168, 706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410

Wolke, D., Tippett, N., and Dantchev, S. (2015). Bullying in the family: sibling bullying. Lancet Psychiatry 2, 917–929. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00262-x

Keywords: child abuse, drawings, narratives, disclosure, art therapy

Citation: Goldner L, Lev-Wiesel R and Binson B (2021) Perceptions of Child Abuse as Manifested in Drawings and Narratives by Children and Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 11:562972. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562972

Received: 20 May 2020; Accepted: 08 December 2020;

Published: 14 January 2021.

Edited by:

Jennifer Drake, Brooklyn College (CUNY), United StatesReviewed by:

Angélica Quiroga-Garza, University of Monterrey, MexicoCopyright © 2021 Goldner, Lev-Wiesel and Binson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Limor Goldner, bGdvbGRuZXJAdW5pdi5oYWlmYS5hYy5pbA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.