- 1Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for Veteran Suicide Prevention, Aurora, CO, United States

- 2Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 3Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 4Department of Neurology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

Rates of suicide and posttraumatic stress disorder remain high among United States military personnel and veterans. Building upon prior work, we conducted a systematic review of research published from 2010 to 2018 regarding: (1) the prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide among United States military personnel and veterans diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder; (2) whether posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide among United States military personnel and veterans. 2,106 titles and abstracts were screened, with 48 articles included. Overall risk of bias was generally high for studies on suicidal ideation or suicide attempt and low for studies on suicide. Across studies, rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide widely varied based on study methodology and assessment approaches. Findings regarding the association between posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis with suicidal ideation and suicide were generally mixed, and some studies reported that posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with lower risk for suicide. In contrast, most studies reported significant associations between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide attempt. These findings suggest complex associations between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide, which are likely influenced by other factors (e.g., psychiatric comorbidity). In addition, most samples were comprised of veterans, rather than military personnel. Further research is warranted to elucidate associations between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide, including identification of moderators and mediators of this relationship. Addressing this among United States military personnel, by gender, and in relation to different trauma types is also necessary.

Introduction

Within the United States (U.S.), suicide remains a significant public health concern, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reporting it as the tenth overall leading cause of death (Heron, 2018). Risk for suicide is especially pronounced among U.S. military personnel and veterans, among whom adjusted suicide rates have, at times, outpaced suicide rates in the general U.S. non-veteran adult population (Reimann and Mazuchowski, 2018; Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019). As such, preventing suicide among military personnel and veterans remains a top clinical priority of the Departments of Defense and VA.

Efforts have been made to understand why U.S. military personnel and veterans are at increased risk for suicide, compared to civilians. Although suicide is understood to be etiologically complex, one potential conduit of increased risk is through traumatic experiences and their sequelae. Military personnel and veterans experience trauma with heightened propensity, both in terms of military- and non-military-related trauma, such as combat-related experiences, military sexual assault, childhood abuse, and intimate partner violence (Gates et al., 2012; Lehavot et al., 2018). Military personnel and veterans also experience high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Gates et al., 2012; Lehavot et al., 2018). As such, researchers have posited elevated rates of PTSD as a potential explanation for suicidal ideation (SI), suicide attempt (SA), and suicide among service members and veterans (Pompili et al., 2013). Indeed, prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the relationship between PTSD and suicide have reported significant associations between PTSD and suicide risk (Krysinska and Lester, 2010; Kanwar et al., 2013; Panagioti et al., 2015). However, to date, only one such review has focused specifically on military personnel and veterans (Pompili et al., 2013).

Pompili et al. (2013) conducted a systematic review of literature published from 1980 to 2010 regarding the association between PTSD with SI and suicidal self-directed violence (S-SDV; e.g., suicide attempt, suicide) among U.S. and Canadian military personnel and veterans. Based on their review of 18 studies, they concluded that PTSD was associated with SI, SA, and suicide. Pompili et al. further noted, however, that PTSD was associated with several mental health outcomes (e.g., psychiatric comorbidity), which may have partially accounted for the reported associations. As such, it remains difficult to ascertain to what extent PTSD independently explains heightened risk for SI, SA, and suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans.

While the aforementioned systematic review was seminal in its focus on military personnel and veterans, the review focused on “war-related PTSD” (e.g., combat-related), limiting inference regarding PTSD from other prevalent military- or non-military related traumatic exposures (e.g., military sexual assault, childhood abuse). Another limitation of the prior review was the inclusion of studies focused on PTSD symptoms, limiting the ability to draw precise inferences regarding PTSD diagnosis, as those without a diagnosis of PTSD may have been included. In addition, since 2010, veterans from the recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have experienced high rates of deployment-related experiences, such as combat and sexual assault (Street et al., 2009; Vasterling et al., 2010; Barth et al., 2016). While some of these experiences are not necessarily unique to deployment (e.g., sexual assault can occur during training or while stateside), deployment can disrupt pre-deployment life and family functioning. For example, Paley et al. (2013) noted that deployment can introduce a number of challenges, including disruptions in family routine, extended separation from friends and family, and parenting challenges following return due to mental health sequelae. These disruptions appear particularly salient in driving PTSD symptomatology following military-related trauma (Polusny et al., 2014). This, in turn, may result in differing clinical presentations in more recent research with military personnel and veterans that could impact associations of PTSD with SI and S-SDV. As such, an updated review of the literature published since 2010 is critical.

Finally, a number of prior reviews discussed SI, SA, and suicide as categorically-similar constructs, rather than differentiating between these outcomes. This is problematic to discerning optimal clinical care to mitigate risk among service members and veterans with PTSD (Holliday et al., 2019). The VA and Department of Defense have mandated a specific classification system and nomenclature for suicide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Suicidal Self-Directed Violence Classification System (Crosby et al., 2011), to distinguish these constructs. The CDC defines suicidal ideation as “thoughts of engaging in suicide-related behavior” (p. 90), suicide attempt as “a non-fatal self-directed potentially injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior…which may or may not result in injury” (p. 21), and suicide as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior” (p. 23). As these constructs have distinct underlying theoretical underpinnings, as well as divergent risk factors (Joiner, 2007; Nock et al., 2008; Klonsky and May, 2015; Klonsky et al., 2016; May and Klonsky, 2016), delineating the extent to which a diagnosis of PTSD is associated with SI, SA, and suicide remains crucial.

The current systematic review aimed to address these limitations and provide an enhanced update of research examining the association between PTSD diagnosis and SI, SA, and suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans. To update prior work (c.f. Pompili et al., 2013), this review focused on literature published between 2010 and 2018. Specifically, we focused on two key questions (KQ):

KQ1. What is the prevalence of SI, SA, and suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD?

KQ2. Is PTSD diagnosis associated with SI, SA, and suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans?

Methods

Methods and presentation of results map onto the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018089267). We conducted a systematic search of literature published between January 1, 2010 and April 25, 2018 in the following electronic databases: OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, OVID PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Published International Literature On Traumatic Stress (PILOTS), and Cochrane Library. The search strategy was developed using medical subject heading terms (MeSH) and relevant text and key words in OVID MEDLINE, then replicated in each database (see Supplementary Table 1 for additional information). Google Scholar was also searched to identify gray literature studies that met inclusion criteria but had been published outside traditional academic distribution channels or were not yet indexed in electronic databases. Reference lists were also mined for relevant publications not already identified.

Eligibility criteria were defined in accordance with the Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes, Timing/Setting (PI[E]COTS) framework (Moher et al., 2009; Matchar, 2012). In particular, inclusion criteria were as follows: Population(s): U.S. military personnel and/or veterans; Intervention/Exposure(s): (1) Assessment and diagnosis of PTSD and (2) assessment or documentation of SI, SA, or suicide; Comparator(s): A comparison group was not required for KQ1; however, for KQ2, a comparator of no PTSD diagnosis was required; Outcome(s): Prevalence of SI, SA, or suicide among those with PTSD (KQ1); reported on the association between PTSD and SI, SA, or suicide (KQ2); and Timing/Setting: No restrictions based on timing, setting, or study design. Additional criteria for inclusion were: (1) presentation of original study data in a peer-reviewed journal article; (2) adequate data to address KQ1 and/or KQ2 (i.e., reported rate and/or association between PTSD and SI, SA, or suicide within text); (3) the full-text article was in English; and (4) published between January 1, 2010 and April 25, 2018. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplicate datasets (i.e., re-analysis of a previously reported dataset) and (2) inadequate data (i.e., inability to calculate rates or associations based on content reported within the manuscript); (3) dissertations, conference proceedings, commentaries, editorials, letters, books, book chapters, duplicate datasets, and reviews.

Databases were searched sequentially on the same day. Complete citations were exported and de-duplicated using EndNote X8 reference management software (Thomson Reuters, New York City, NY, USA). References were then exported into Covidence review software. Review of studies for inclusion was based on previously-used systematic review frameworks, including those used by the study team (Hoffberg et al., 2020).

For the PRISMA screening stage, at least two reviewers (RH, LMB, KSY, LAB) independently screened each title and abstract for retrieval. When not in agreement, a third reviewer (LLM) evaluated the record for the final retrieval decision. All co-authors have experience conducting research on PTSD and SI and S-SDV among U.S. veterans and have previously published in this domain (e.g., Brenner et al., 2011a; Holliday et al., 2018b; Barnes et al., 2019; Monteith et al., 2019).

Covidence was also used to evaluate records selected for the PRISMA eligibility stage of the review. Each full-text record was assessed by at least two reviewers (RH, LMB, KSY, LAB). The decision process was stepwise and based on the PICOTS model. Each reviewer progressed through the PICOTS decision tree until either all inclusion criteria were met or the record was excluded for a particular reason. Any disagreements at this stage were similarly resolved by a third blind reviewer (LLM).

Data from full-text articles selected for inclusion were abstracted into tables by three authors (RH, LMB, and LLM). Conflicts were resolved by group consensus, with RH making the final determination for inclusion. The preliminary data abstraction template was tested before being finalized. The following information was extracted: source article, population/sample (e.g., composed of military personnel or veterans, proportion of males and females within the sample, index trauma), measurement of PTSD, measurement of SI/SA/suicide, prevalence of SI/SA/suicide among those diagnosed with PTSD (KQ1), association of PTSD to SI/SA/suicide (KQ2), and additional relevant results. As variability of study designs and outcome measurements precluded a meta-analytic approach, a descriptive synthesis approach was conducted (McKenzie and Brennan, 2019). For each study included, the sample was described based on composition (i.e., military personnel or veteran) and proportion of males/females; however, due to infrequent reporting across studies, index trauma could not consistently be assessed and was thus not reported.

Included articles were classified by study design using the Taxonomy of Study Design Tool (Hartling et al., 2010) in a custom Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database (Harris et al., 2009). Study design was assessed independently (KSY, ASH), with conflicts resolved by a third author (RH). Each of these authors had prior experience conducting systematic reviews or meta-analyses (Bahraini et al., 2013; Hoffberg et al., 2018, 2020; Holliday et al., 2018a; Creech et al., 2019).

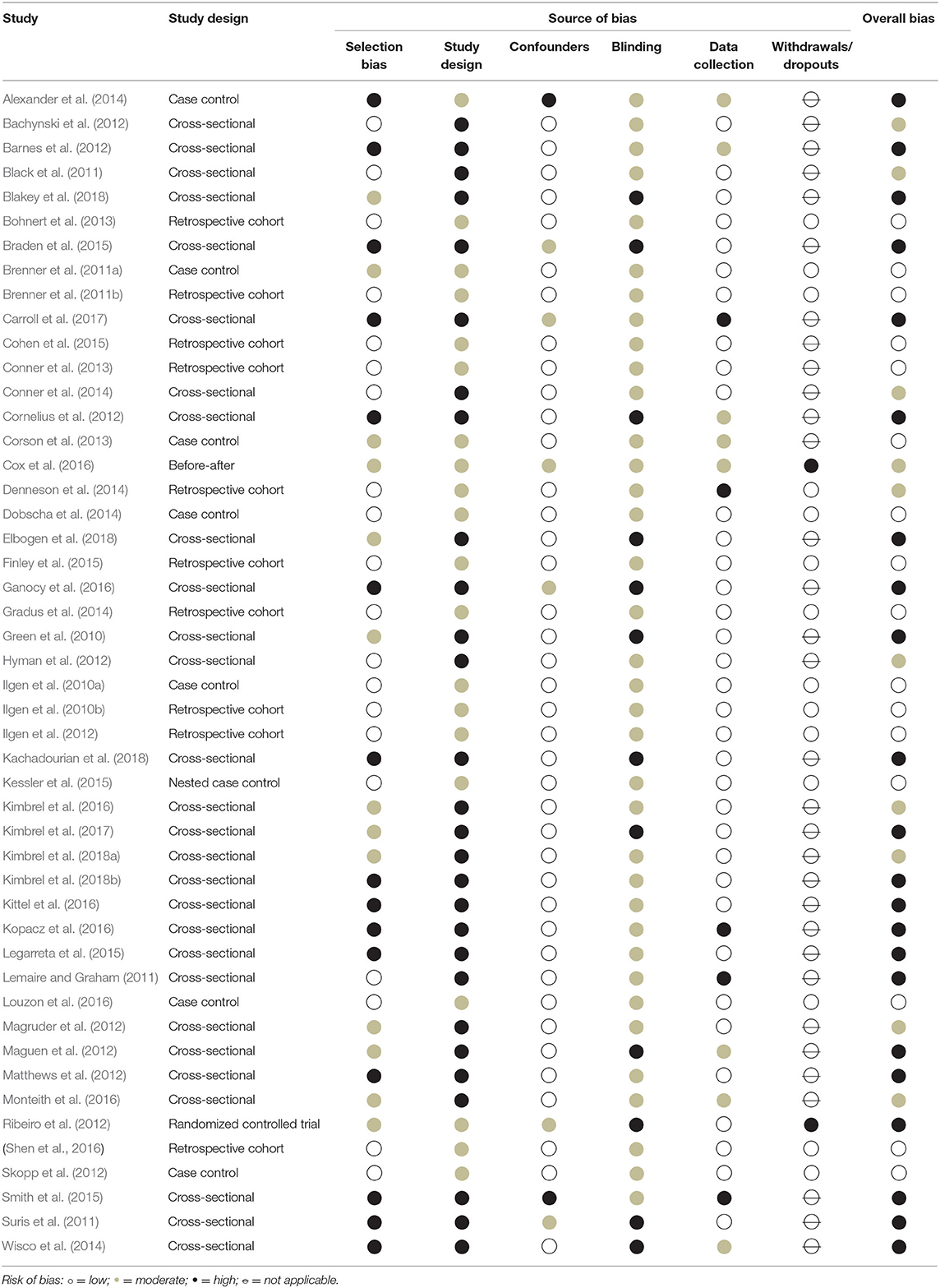

After reaching consensus on study design, risk of bias was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies (Thomas et al., 2004). Bias items included selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection, withdrawals/dropouts, and other sources (e.g., no disclosure of conflicts of interest). Each of these domains, if applicable, were rated as having a low, moderate, or high risk of bias based on standard guidelines (see Thomas et al., 2004 for additional information). An overall risk of bias rating was then generated using standard guidelines (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 1998a,b), such that studies rated as having no high risk of bias domain ratings were classified as low overall risk of bias, studies having up to one high risk of bias domain rating were classified as moderate overall risk of bias, and studies having two or more high risk of bias domain ratings were classified as high overall risk of bias. Risk of bias was evaluated independently by KSY and ASH, with discrepancies discussed among KSY, ASH, and RH until achieving consensus. Both KSY and ASH had prior experience evaluating risk of bias in prior systematic reviews (e.g., Hoffberg et al., 2018, 2020).

Results

Study Selection

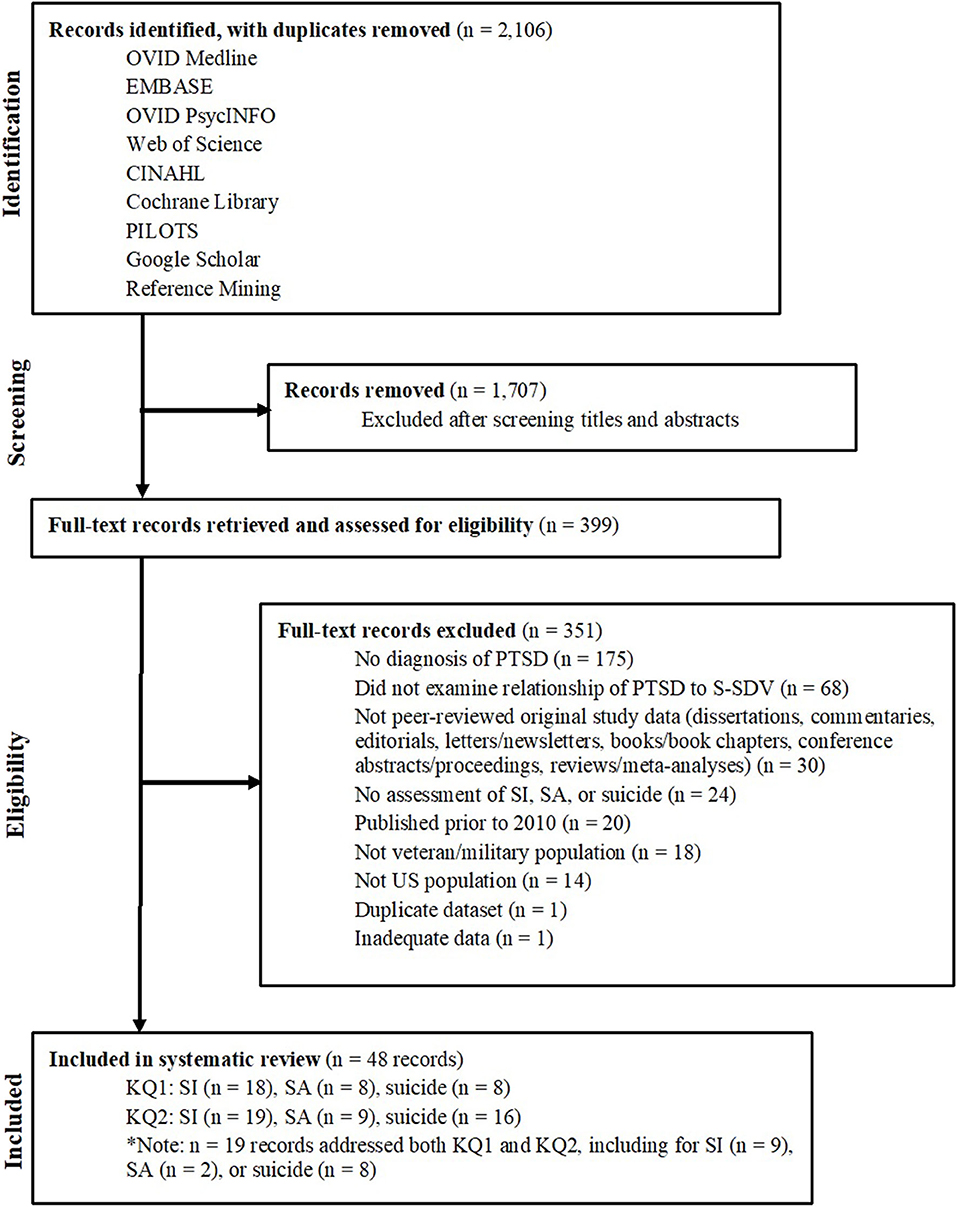

As depicted in Figure 1, 2,106 titles and abstracts identified in electronic searches were screened after removing duplicates. Following screening, 399 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Based on our PICOTS criteria, 351 of these full-text articles were subsequently excluded, resulting in 48 articles included for KQ1 and/or KQ2. Risk of bias for these articles is reported in Table 1.

Synthesis of Literature

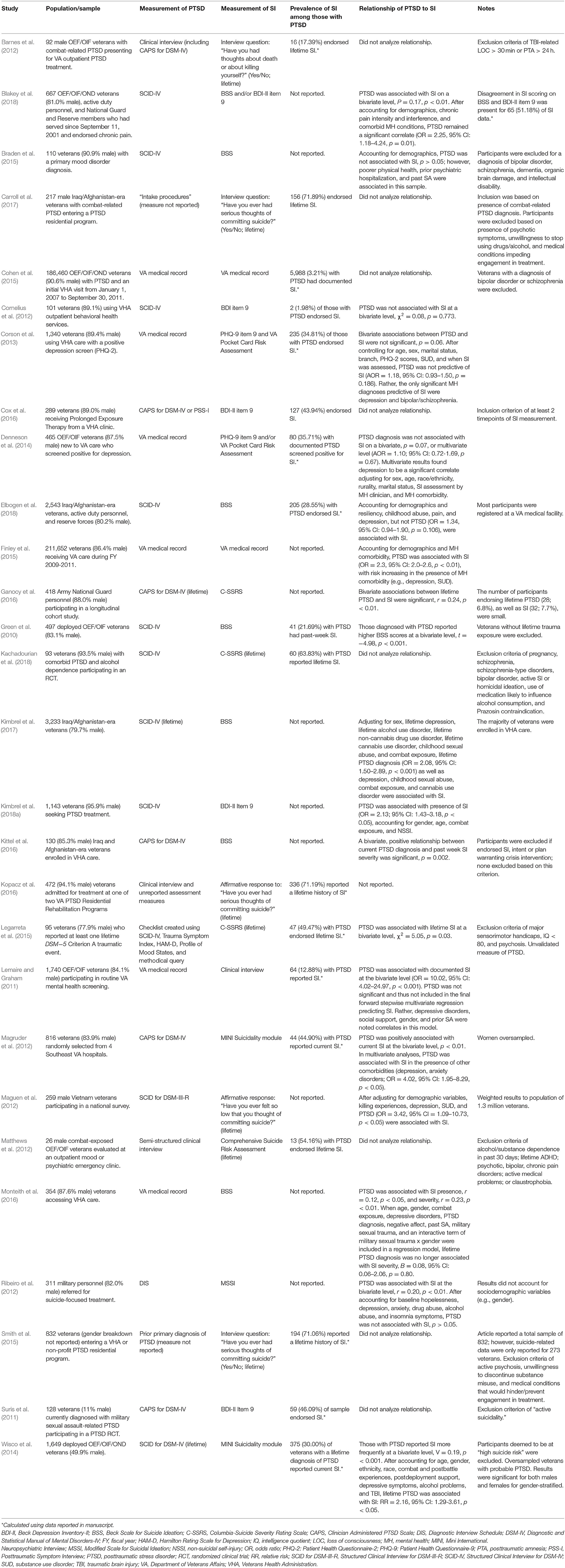

KQ1: Prevalence of SI Among Military Personnel and Veterans With PTSD

Eighteen studies reported on the prevalence of SI among U.S. military personnel or veterans diagnosed with PTSD. Rates of SI across studies ranged from 1.98 to 71.89% (Table 2). However, the overwhelming majority of included studies (n = 13) had a high overall risk of bias. Three had an overall moderate risk of bias and reported rates of SI ranging from 35.71 to 44.90% (Magruder et al., 2012; Denneson et al., 2014; Cox et al., 2016). Only two studies had a low overall risk of bias, reporting that 3.21–34.81% of veterans with PTSD had SI (Corson et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2015). Of studies relying on interview or assessment measures, current/recent rates of SI ranged from 1.98 to 44.9%, whereas lifetime rates varied more broadly, from 17.39 to 71.89%. All of these studies focused on veterans; none focused exclusively on military personnel. Studies evaluating lifetime SI often comprised fairly small clinical samples, whereas studies reporting on more recent SI involved much larger samples, typically comprising treatment-seeking Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans.

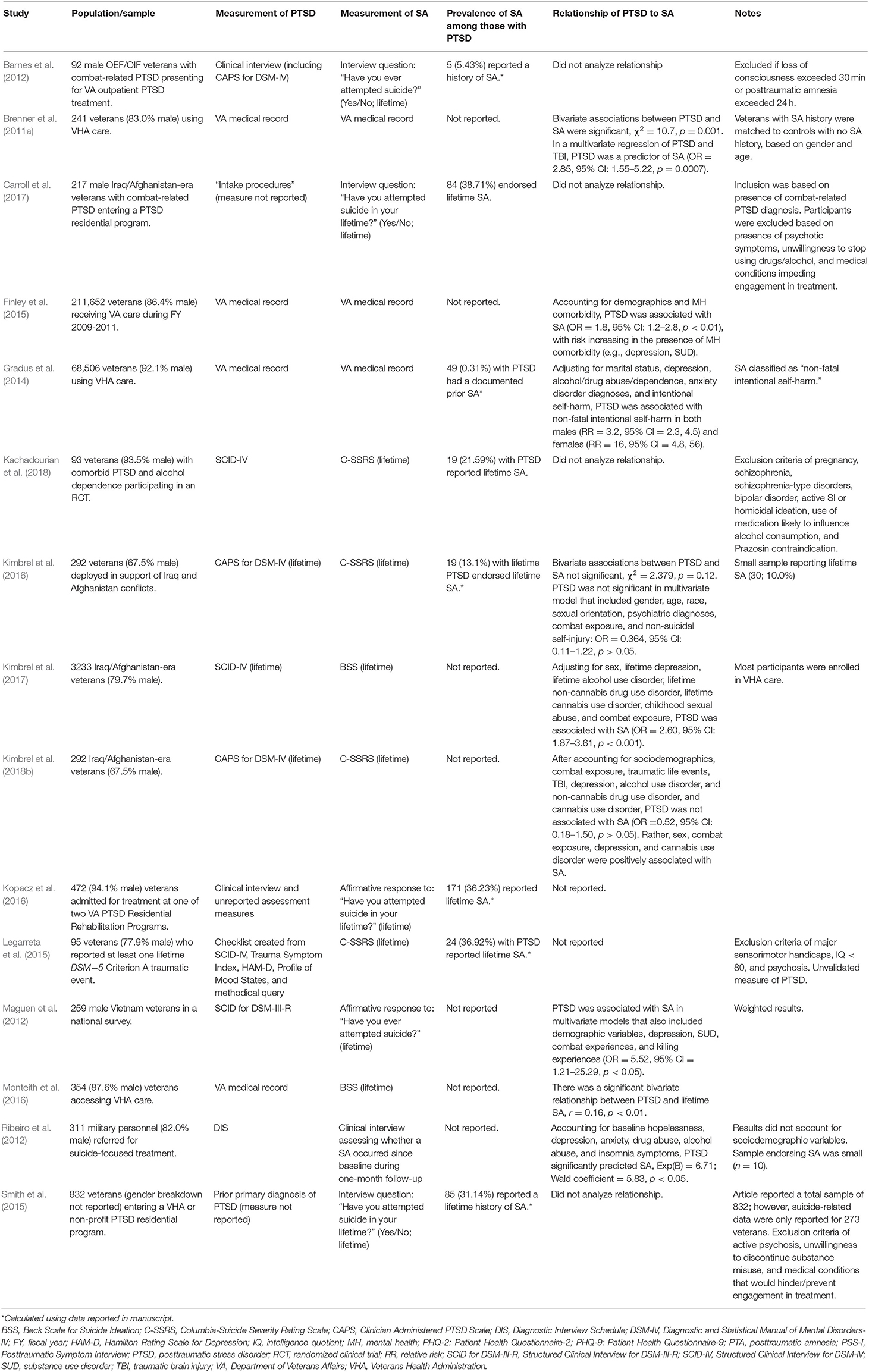

KQ1: Prevalence of SA Among Military Personnel and Veterans With PTSD

The eight studies on rates of SA among those diagnosed with PTSD reported rates ranging from 0.31 to 38.71% (Table 3). Only one included study was determined to have a low overall risk of bias (Gradus et al., 2014), and one had a moderate overall risk of bias (Kimbrel et al., 2016). Of note, all of the studies on the prevalence of SA among those with PTSD focused on veterans; none reported on rates of SA among military personnel with PTSD.

KQ1: Prevalence of Suicide Among Military Personnel and Veterans With PTSD

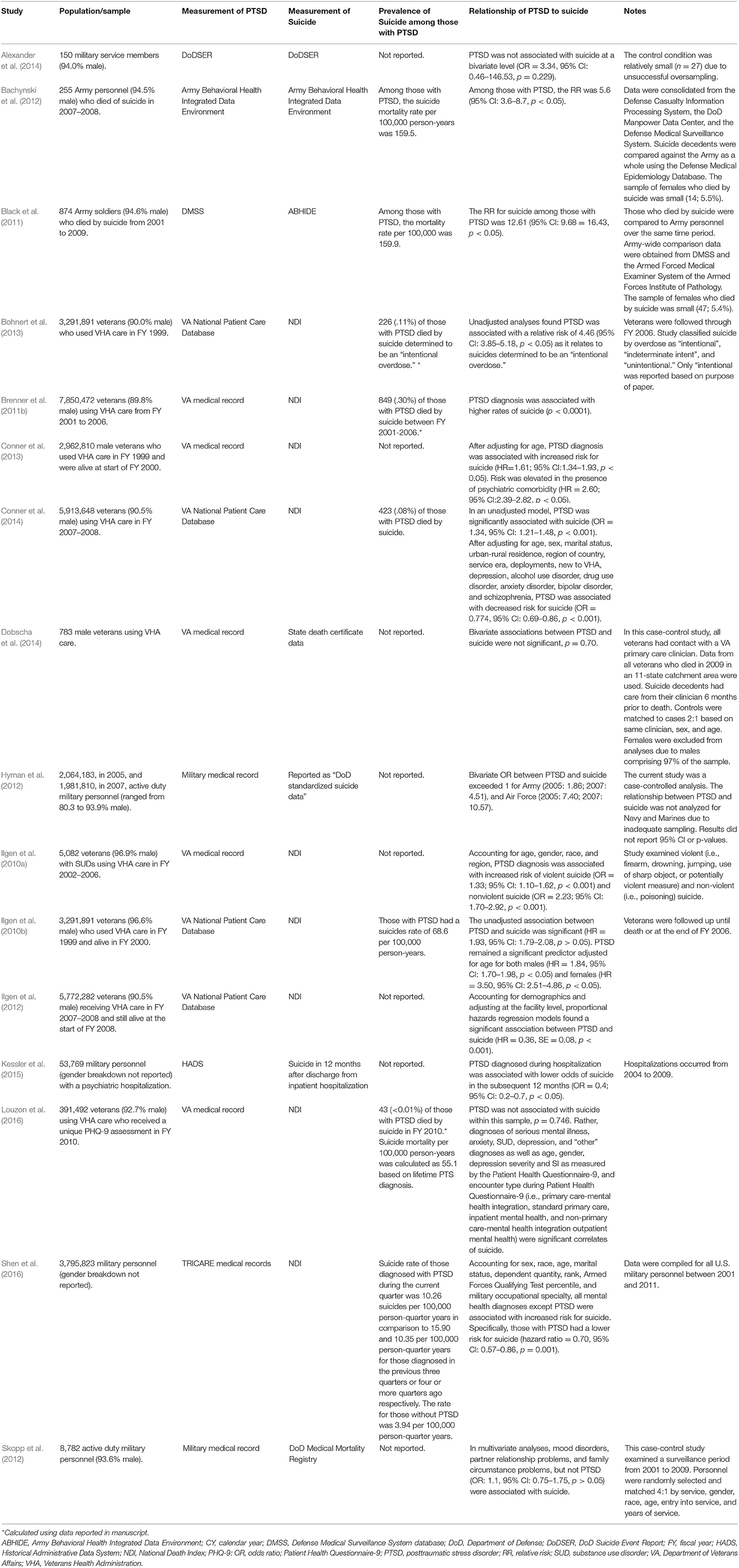

Eight studies were included that reported on the prevalence of suicide among military personnel and veterans diagnosed with PTSD (Table 4). Strength of evidence appeared strong for these studies, as the majority of included studies were determined to have a low overall risk of bias (n = 5; Ilgen et al., 2010b; Brenner et al., 2011b; Bohnert et al., 2013; Louzon et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016). Four studies reported the percent of military personnel or veterans with PTSD who died by suicide, with a range of <0.01–0.30% (Brenner et al., 2011b; Bohnert et al., 2013; Conner et al., 2014; Louzon et al., 2016). An additional four studies reported rates per person-years, ranging from 55.1 to 159.9 per 100,000 (Ilgen et al., 2010b; Black et al., 2011; Bachynski et al., 2012; Louzon et al., 2016), with rates ranging based on timeframe (e.g., per-person year, per-person quarter).

KQ2: Association of PTSD With SI Among Military Personnel and Veterans

Nineteen studies reported on the association between PTSD and SI. The majority of included studies were determined to have a high overall risk of bias (n = 13), four had a moderate risk of bias (Magruder et al., 2012; Denneson et al., 2014; Monteith et al., 2016; Kimbrel et al., 2018a), and only two studies had a low overall risk of bias (Corson et al., 2013; Finley et al., 2015). Bivariate associations between PTSD and SI were generally significant (significant in ten studies, non-significant in three studies; Table 2). In contrast, results regarding the association between PTSD and SI at the multivariate level were mixed. Of the fourteen studies reporting multivariate results regarding the association between PTSD and SI, seven reported significant associations, and seven reported non-significant associations. All of the studies reporting significant bivariate or multivariate associations between PTSD and SI reported that these were positively, rather than inversely, associated.

KQ2: Association of PTSD With SA Among Military Personnel and Veterans

Nine studies examined the relationship between PTSD and SA. Only three had a low overall risk of bias (Brenner et al., 2011a; Gradus et al., 2014; Finley et al., 2015), all of which reported significant associations between PTSD and SA (Table 3). In fact, all but two studies reported significant positive associations at the bivariate and/or multivariate level. In addition, all but one study focused on veterans (versus military personnel).

KQ2: Association of PTSD With Suicide Among Military Personnel and Veterans

Sixteen studies examined the relationship between PTSD and suicide (Table 4), with the majority having a low overall risk of bias (n = 11; Ilgen et al., 2010a,b, 2012; Brenner et al., 2011b; Skopp et al., 2012; Bohnert et al., 2013; Conner et al., 2013; Dobscha et al., 2014; Kessler et al., 2015; Louzon et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016). Among these 16 studies, findings were mixed. Nine studies, four of which used multivariate analyses, reported that those diagnosed with PTSD were at greater risk for suicide. Interestingly, in seven studies, five of which used multivariate analyses, PTSD was not a significant predictor of increased risk for suicide (Skopp et al., 2012; Alexander et al., 2014; Dobscha et al., 2014; Louzon et al., 2016), with three of these studies reporting that suicide risk was significantly lower among those diagnosed with PTSD (Conner et al., 2014; Kessler et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2016). When restricting to only studies with low overall risk of bias, results were still mixed, with six reporting significant positive associations (Ilgen et al., 2010a,b, 2012; Brenner et al., 2011b; Bohnert et al., 2013; Conner et al., 2013), three reporting non-significant associations (Skopp et al., 2012; Dobscha et al., 2014; Louzon et al., 2016), and two reporting significant inverse associations (Kessler et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2016).

Discussion

Given the continued rise in rates of suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans (Reimann and Mazuchowski, 2018; Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019), understanding the extent to which common mental health diagnoses, such as PTSD, are associated with SI, SA, and suicide is important. Building upon the systematic review by Pompili et al. (2013), the current systematic review provides an update of literature spanning 2010–2018, focused on U.S. service members and veterans. Importantly, this review is inclusive of cohorts spanning multiple service eras, including those who served in the recent conflicts based in Afghanistan and Iraq, a population with notably high rates of suicide (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019).

KQ1

This systematic review is among the first to examine the prevalence of SI, SA, and suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans with PTSD. Attempts to determine rates of SI, SA, and suicide across studies were largely impacted by differences in study methodology. Studies varied in their methods of assessing PTSD and suicide-related constructs (e.g., use of electronic medical records vs. validated semi-structured interviews), as well as in the temporality of these variables (e.g., lifetime vs. past month). This resulted in highly variable rates, especially among studies examining SI.

The majority of included studies examining KQ1 for SI and SA were also rated as having high bias in study methodology. This is likely driven, in part, by the fact that many of these studies were not designed to examine the prevalence of SI or SA. Rather, a number of studies examined PTSD, SI, or SA as secondary outcomes or covariates. In contrast, studies on suicide tended to have a low overall risk of bias, although suicide rates were still quite variable. Stronger methodology and consistent reporting regarding assessment and timeframe of PTSD, SI, and SA is needed for future research to ensure accurate depiction of reported rates.

KQ2

Research examining if PTSD is associated with SI and S-SDV was also mixed, suggesting a complex relationship. Only PTSD and SA appeared to have a significant association that was largely maintained in the presence of covariates. In contrast, for studies reporting on the association between PTSD and SI or suicide, multivariate findings diverged, with some studies reporting non-significant associations. Further, in some studies, PTSD was even associated with decreased risk for suicide, further complicating conceptualization of this relationship.

Mixed findings regarding the association between PTSD with SI or suicide were maintained even when restricting studies to those with low overall risk of bias. This suggests that while study methodology and rigor are pertinent to synthesizing the literature base, factors outside of study quality may produce varied findings regarding the relationship between PTSD with both SI and suicide.

Several potential explanations can be posited as to why the relationship between PTSD and SI or suicide may be less robust. First and foremost, inclusion of other important correlates of SI and suicide may be more explanatory of risk than PTSD. Several included studies found other variables to be significant correlates of SI, SA, and suicide, including psychiatric comorbidities, psychosocial functioning (e.g., socioeconomic status, social support), and sociodemographic factors. In particular, across several studies, depression was a robust predictor of SI and S-SDV and thus may be more explanatory of suicide risk among U.S. military personnel and veterans with PTSD.

It is also important to note that a number of the studies which reported non-significant relationships between PTSD and SI or S-SDV relied on electronic medical records. There is sizable variability in the diagnostic validity of data obtained from medical records compared to diagnostic interviews (Holowka et al., 2014), suggesting that this may be an important factor to consider when interpreting these findings. The recency (e.g., past-month vs. lifetime) of PTSD, SI, and SA also can be difficult to ascertain from electronic medical records, which may further impact findings.

While our systematic review focused on the presence or absence of a PTSD diagnosis, a dichotomous focus on the presence or absence of a PTSD diagnosis likely does not provide sufficiently nuanced information regarding factors inherent to, or associated with, PTSD that may be driving risk within this population. The clinical presentation of PTSD can vary largely between patients based on heterogenous symptom profiles. In addition, specific symptoms of PTSD, such as guilt, social isolation, and trauma-related beliefs, have been posited as risk factors for suicide among military personnel and veterans (Bryan et al., 2013, 2017; DeBeer et al., 2014; Legarreta et al., 2015; McLean et al., 2017; Holliday et al., 2018a; Borges et al., 2020), but were not the focus of the current review. More research is needed to understand if specific components of PTSD are more strongly related to SI and suicide among military personnel and veterans.

Despite these potential explanations, none provide insight as to why the overwhelming majority of studies on SA found that PTSD was associated with SA, while many studies on SI and suicide did not. Research noting inherent differences in what motivates progression from SI to S-SDV (Nock et al., 2008) may explain some of these differences in findings regarding SI and SA, but would not necessarily explain inconsistencies between findings on SA vs. suicide. One alternate explanation is that, for KQ2, the number of SA studies, particularly low risk of bias studies, were far fewer; as such, inclusion of additional studies may regress toward a more confident understanding of the relationship between PTSD diagnosis and SA. Overall risk of bias for studies on SA were largely rated as moderate to high, leading to potentially spurious findings in comparison to the majority of studies on suicide, which were generally rated as low. This further reinforces the need for additional investigation of the relationship between PTSD and SA, using consistent, sound methodology.

Additional factors underlying S-SDV may also explain variance. For instance, differing means of attempting suicide (e.g., firearms vs. overdose) vary in lethality, as the overwhelming majority of individuals who use a firearm to attempt suicide die (Spicer and Miller, 2000). It is possible that those who survive a SA using a less lethal means differ in their precipitants and drivers of suicide risk in comparison to those who use more lethal means (e.g., firearms). Given that military personnel and veterans have high rates of access to highly lethal means (e.g., firearms; Cleveland et al., 2017) as well as the potential interrelationship between trauma and firearm access (Monteith et al., 2020; Sadler et al., 2020; Simonetti et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2020), longitudinal research must be prioritized to further understand if PTSD is associated with using different types of lethal means to enact S-SDV.

Limitations and Future Research

While this systematic review provides important insight into research published since 2010, several factors limit comprehensive inferences regarding this body of literature. A number of studies did not report rates of SI, SA, or suicide specific to those diagnosed with PTSD, precluding inclusion for KQ1. Included study samples were also overwhelmingly male and veteran, which generally reflects the compositions of the U.S. military and veteran populations. Nonetheless, as most studies reviewed did not adequately sample women or report rates or associations separately based on gender, future studies should consider oversampling women to facilitate exploring whether associations between PTSD with SI, SA, and suicide differ by gender.

Moreover, while our review expanded beyond war-related trauma (Pompili et al., 2013) to also include non-combat-related trauma (e.g., military sexual assault), only a limited number of studies specifically assessed and reported on trauma type or focused on non-combat-related PTSD. Because of this, it was not possible to differentiate rates and associations based on types of trauma. Therefore, given research suggesting that risk (e.g., for SI) may differ based on trauma type (Blais and Monteith, 2019), researchers should assess and report type of index trauma among their samples, especially in research pertaining to SI, SA, and suicide.

The current systematic review also focused on PTSD diagnosis, excluding studies relying on self-report symptom inventories (e.g., PTSD Checklist). While these inventories are psychometrically valid and can determine probable diagnoses, they should not be used to infer a formal diagnosis. As this was a departure from prior systematic reviews (e.g., Pompili et al., 2013), it may contribute to differences in findings. A number of studies also used single-item self-report measures of SI and SA. While these items were face valid, their psychometric properties relative to a clinical interview or formal assessment measure is debatable. Further inquiry is needed to understand how method of assessing SI and SA may impact findings.

Included studies were also predominantly cross-sectional. While still informative, such studies were rated as having higher risk of bias as this type of design precludes understanding the temporal relationship between PTSD with SI and SA (i.e., if PTSD precedes subsequent SI and SA). Longitudinal research was limited in this body of literature, and in particular, prospective cohort studies are warranted to further elucidate drivers of suicide risk.

Finally, studies largely differed in the factors that they accounted for in multivariate analyses. Because analytic approaches differed across studies, it is difficult to infer if associations between PTSD with SI, SA, and suicide would have differed based on inclusion of additional variables. As such, researchers should ensure multivariate analyses with PTSD also include correlates of SI, SA, and suicide identified in this review (e.g., depression) to better understand the magnitude and direction of the association with PTSD. Consistent inclusion of these factors would also facilitate future research focused on understanding potential moderators and mediators of the association between PTSD and SI, SA, and suicide (e.g., meta-regression).

Conclusions

When interpreting findings within the context of these limitations, this systematic review provides insight into the prevalence of SI, SA, and suicide among U.S. military personnel and veterans. Results provide continued, yet tentative, support that PTSD diagnosis is likely associated with SI, SA, and suicide at a bivariate level. Because of this, clinicians should continue to assess for PTSD, as well as associated psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., depression), in the context of suicide risk assessment when working with trauma-exposed U.S. military personnel and veterans. Similarly, clinicians should continue to screen for SI and prior SA when working with military personnel and veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

For many service members and veterans, PTSD may not be the sole driver of suicide risk, as SI, SA, and suicide are likely the result of an accumulation of numerous comorbid risk factors (e.g., depression) and other trauma-related sequelae (e.g., low social support; Lemaire and Graham, 2011). It is important to note that PTSD likely also increases risk for psychiatric comorbidity and decreased psychosocial functioning (Pietrzak et al., 2010; Hefner and Rosenheck, 2019). Therefore, PTSD may increase risk through indirect pathways (e.g., PTSD increases risk for depression, which, in turn, increases risk for suicide; e.g., McKinney et al., 2017).

Given the lack of consistency in multivariate results, further synthesis of the literature remains warranted. Analytic approaches that account for methodological differences between studies (e.g., diagnostic interview vs. electronic medical record) and also synthesize the role of potential covariates and other notable risk factors (e.g., depression) across studies is an integral next step. Additional understanding of specific aspects of PTSD (e.g., guilt, social isolation, trauma-related beliefs) that potentially moderate or mediate the relationship between PTSD diagnosis with SI, SA, and suicide would also further elucidate factors potentially impacting risk among U.S. military personnel and veterans. Identification of specific drivers of risk would be particularly important to inform clinical assessment and evidence-based treatment to prevent SI and S-SDV among U.S. military personnel and veterans with PTSD.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to potential study inclusion, review, and writing of the finalized manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA); the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for Veteran Suicide Prevention; and the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policy of the VA or the United States Government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01998/full#supplementary-material

References

Alexander, C. L., Reger, M. A., Smolenski, D. J., and Fullerton, N. R. (2014). Comparing U.S. Army suicide cases to a control sample: initial data and methodological lessons. Military Med. 179, 1062–1066. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00574

Bachynski, K. E., Canham-Chervak, M., Black, S. A., Dada, E. O., Millikan, A. M., and Jone, B. H. (2012). Mental health risk factors for suicides in the US Army, 2007-8. Injury Prevention 18, 405–412. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040112

Bahraini, N. H., Simpson, G. K., Brenner, L. A., Hoffberg, A. S., and Schneider, A. L. (2013). Suicidal ideation and behaviours after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Brain Impairment 14, 92–112. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2013.11

Barnes, S. M., Monteith, L. L., Forster, J. E., Nazem, S., Borges, L. M., Stearns-Yoder, K. A., et al. (2019). Developing predictive models to enhance clinician prediction of suicide attempts among veterans with and without PTSD. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 49, 1094–1104. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12511

Barnes, S. M., Walter, K. H., and Chard, K. M. (2012). Does a history of mild traumatic brain injury increase suicide risk in veterans with PTSD? Rehabil. Psychol. 57, 18–26. doi: 10.1037/a0027007

Barth, S. K., Kimerling, R. E., Pavao, J., McCutcheon, S. J., Batten, S. V., Dursa, E., et al. (2016). Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: Correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 50, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.012

Black, S. A., Gallaway, M. S., Bell, M. R., and Ritchie, E. C. (2011). Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicides of Army soldiers 2001-2009. Military Psychol. 23, 433–451. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.590409

Blais, R. K., and Monteith, L. L. (2019). Suicide ideation in female survivors of military sexual trauma: the trauma source matters. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 49, 643–652. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12464

Blakey, S. M., Wagner, H. R., Naylor, J., Brancu, M., Lane, I., Sallee, M., et al. (2018). Chronic Pain, TBI, and PTSD in military veterans: a link to suicidal ideation and violent impulses? J. Pain 19, 797–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.012

Bohnert, A. S. B., McCarthy, J. F., Ignacio, R. V., Ilgen, M. A., Eisenberg, A., and Blow, F. C. (2013). Misclassification of suicide deaths: examining the psychiatric history of overdose decedents. Injury Prevention 19, 326–330. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040631

Borges, L. M., Bahraini, N. H., Dorsey Holliman, B., Gissen, M. R., Lawson, W. C., and Barnes, S. M. (2020). Veterans' perspectives on discussing moral injury in the context of evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD and other VA treatment. J. Clin. Psychol. 76, 377–391. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22887

Braden, A., Overholser, J., Fisher, L., and Ridley, J. (2015). Life meaning is associated with suicidal ideation among depressed veterans. Death Stud. 39, 24–29. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2013.871604

Brenner, L. A., Betthauser, L. M., Homaifar, B. Y., Villarreal, E., Harwood, J. E., Staves, P. J., et al. (2011a). Posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and suicide attempt history among veterans receiving mental health services. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 41, 416–423.

Brenner, L. A., Ignacio, R. V., and Blow, F. C. (2011b). Suicide and traumatic brain injury among individuals seeking veterans health administration services. J. Head Trauma Rehabilit. 26, 257–264. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31821fdb6e

Bryan, C. J., Grove, J. L., and Kimbrel, N. A. (2017). Theory-driven models of self-directed violence among individuals with PTSD. Curr. Opinion Psychol. 14, 12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.09.007

Bryan, C. J., Ray-Sannerud, B., Morrow, C. E., and Etienne, N. (2013). Guilt is more strongly associated with suicidal ideation among military personnel with direct combat exposure. J. Affect. Disord. 148, 37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.044

Carroll, T. D., Currier, J. M., McCormick, W. H., and Drescher, K. D. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and risk for suicidal behavior in male Iraq and Afghanistan veterans seeking PTSD treatment. Psychol. Trauma 9, 583–586. doi: 10.1037/tra0000250

Cleveland, E. C., Azrael, D., Simonetti, J. A., and Miller, M. (2017). Firearm ownership among American veterans: Findings from the 2015 National Firearm Survey. Injury Epidemiology 4:33. doi: 10.1186/s40621-017-0130-y

Cohen, B. E., Shi, Y., Neylan, T. C., Maguen, S., and Seal, K. H. (2015). Antipsychotic prescriptions in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder in Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare, 2007-2012. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, 406–412. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08857

Conner, K. R., Bohnert, A. S., McCarthy, J. F., Valenstein, M., Bossarte, R., Ignacio, R., et al. (2013). Mental disorder comorbidity and suicide among 2.96 million men receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration health system. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 122, 256–263. doi: 10.1037/a0030163

Conner, K. R., Bossarte, R. M., He, H., Arora, J., Lu, N., Tu, X. M., et al. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide in 5.9 million individuals receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration health system. J. Affect. Disord. 166, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.067

Cornelius, J. R., Haas, G. L., Appelt, C. J., Walker, J. D., Fox, L. J., Kasckow, J. W., et al. (2012). Suicidal Ideation Associated with PCL Checklist-Ascertained PTSD among veterans treated for substance abuse. Intern. J. Med. Biol. Front. 18, 783–794.

Corson, K., Denneson, L. M., Bair, M. J., Helmer, D. A., Goulet, J. L., and Dobscha, S. K. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 149, 291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.043

Cox, K. S., Mouilso, E. R., Venners, M. R., Defever, M. E., Duvivier, L., Rauch, S. A. M., et al. (2016). Reducing suicidal ideation through evidence-based treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 80, 59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.05.011

Creech, S. K., Pulverman, C. S., Crawford, J. N., Holliday, R., Monteith, L. L., Lehavot, K., et al. (2019). Clinical complexity in women veterans: A systematic review of the recent evidence on mental health and physical health comorbidities. Behav. Med. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1644283. [Epub ahead of print].

Crosby, A. E., Ortega, L., and Melanson, C. (2011). Self-Directed Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

DeBeer, B. B., Kimbrel, N. A., Meyer, E. C., Gulliver, S. B., and Morissette, S. B. (2014). Combined PTSD and depressive symptoms interact with post-deployment social support to predict suicidal ideation in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Psychiatry Res. 216, 357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.010

Denneson, L. M., Corson, K., Helmer, D. A., Bair, M. J., and Dobscha, S. K. (2014). Mental health utilization of new-to-care Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans following suicidal ideation assessment. Psychiatry Res. 217, 147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.017

Department of Veterans Affairs (2019). 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf.

Dobscha, S. K., Denneson, L. M., Kovas, A. E., Teo, A., Forsberg, C. W., Kaplan, M. S., et al. (2014). Correlates of suicide among veterans treated in primary care: case-control study of a nationally representative sample. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 29, S853–S860. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3028-1

Elbogen, E. B., Wagner, H. R., Kimbrel, N. A., Brancu, M., Naylor, J., Graziano, R., et al. (2018). Risk factors for concurrent suicidal ideation and violent impulses in military veterans. Psychol. Assess 30, 425–435. doi: 10.1037/pas0000490

Finley, E. P., Bollinger, M., Noël, P. H., Amuan, M. E., Copeland, L. A., Pugh, J. A., et al. (2015). A national cohort study of the association between the polytrauma clinical triad and suicide-related behavior among US Veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am. J. Public Health 105, 380–387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301957

Ganocy, S. J., Goto, T., Chan, P. K., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Galea, S., et al. (2016). Association of spirituality with mental health conditions in Ohio National Guard soldiers. J. Nervous Mental Disease 204, 524–529. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000519

Gates, M. A., Holowka, D. W., Vasterling, J. J., Keane, T. M., Marx, B. P., and Rosen, R. C. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychol. Serv. 9, 361–382. doi: 10.1037/a0027649

Gradus, J. L., Leatherman, S., Raju, S., Ferguson, R., and Miller, M. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and non-fatal intentional self-harm in Massachusetts veterans. Injury Epidemiol. 1:20. doi: 10.1186/s40621-014-0020-5

Green, K. T., Calhoun, P. S., Dennis, M. F., Beckham, J. C., Miller-Mumford, M., Fernandez, A., et al. (2010). Exploration of the resilience construct in posttraumatic stress disorder severity and functional correlates in military combat veterans who have served since September 11, 2001. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 823–830. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05780blu

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., and Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Hartling, L., Bond, K., Harvey, K., Santaguida, P. L., Viswanathan, M., and Dryden, D. M. (2010). Developing and Testing a Tool for the Classification of Study Designs in Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Exposures. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Hefner, K., and Rosenheck, R. (2019). Multimorbidity among Veterans diagnosed with PTSD in the Veterans Health Administration nationally. Psychiatric Quarterly 90, 275–291. doi: 10.1007/s11126-019-09632-5

Heron, M. (2018). Deaths: Leading causes for 2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_06.pdf

Hoffberg, A. S., Spitzer, E., Mackelprang, J. L., Farro, S. A., and Brenner, L. A. (2018). Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 48, 481–498. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12369

Hoffberg, A. S., Stearns-Yoder, K. A., and Brenner, L. A. (2020). The effectiveness of crisis line services: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 7:399. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00399

Holliday, R., Holder, N., Olson-Madden, J. H., and Monteith, L. L. (2019). Treating posttraumatic stress disorder in the presence of acute risk in veterans and active duty service members: a call for research. J. Nervous Mental Disease 207, 611–614. doi: 10.1097/NMD0000000000001022

Holliday, R., Holder, N., and Surís, A. (2018a). A single-arm meta-analysis of Cognitive Processing Therapy in addressing trauma-related negative beliefs. J. Aggression Maltreat. Trauma 10, 1145–1153. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1429511

Holliday, R., Monteith, L. L., and Wortzel, H. S. (2018b). Understanding, assessing, and conceptualizing suicide risk among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Federal Practitioner 35, 24–27.

Holowka, D. W., Marx, B. P., Gates, M. A., Litman, H. J., Ranganathan, G., Rosen, R. C., et al. (2014). PTSD diagnostic validity in Veterans Affairs electronic records of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 569–579. doi: 10.1037/a0036347

Hyman, J., Ireland, R., Frost, L., and Cottrell, L. (2012). Suicide incidence and risk factors in an active duty US military population. Am. J. Public Health 102, S138–146. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300484

Ilgen, M. A., Bohnert, A. S. B., Ignacio, R. V., McCarthy, J. F., Valenstein, M. M., Kim, H. M., et al. (2010a). Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 1152–1158. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129

Ilgen, M. A., Conner, K. R., Valenstein, M., Austin, K., and Blow, F. C. (2010b). Violent and nonviolent suicide in veterans with substance-use disorders. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 71, 473–479. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.473

Ilgen, M. A., McCarthy, J. F., Ignacio, R. V., Bohnert, A. S. B., Valenstein, M., Blow, F. C., et al. (2012). Psychopathology, Iraq and Afghanistan service, and suicide among Veterans Health Administration patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 80, 323–330. doi: 10.1037/a0028266

Kachadourian, L. K., Gandelman, E., Ralevski, E., and Petrakis, I. L. (2018). Suicidal ideation in military veterans with alcohol dependence and PTSD: the role of hostility. Am. J. Addictions 27, 124–130. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12688

Kanwar, A., Malik, S., Prokop, L. J., Sim, L. A., Feldstein, D., Wang, Z., et al. (2013). The association between anxiety disorders and suicidal behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 30, 917–929. doi: 10.1002/da.22074

Kessler, R. C., Warner, C. H., Ivany, C., Petukhova, M. V., Rose, S., Bromet, E. J., et al. (2015). Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US army soldiers: the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 72, 49–57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754

Kimbrel, N. A., DeBeer, B. B., Meyer, E. C., Gulliver, S. B., and Morissette, S. B. (2016). Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans. Psychiatry Res. 243, 232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.039

Kimbrel, N. A., Dedert, E. A., Van Voorhees, E. E., Elbogen, E. B., Naylor, J. C., Ryan Wagner, H., et al. (2017). Cannabis use disorder and suicide attempts in Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans. J. Psychiatr. Res. 89, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.002

Kimbrel, N. A., Meyer, E. C., DeBeer, B. B., Gulliver, S. B., and Morissette, S. B. (2018b). The impact of cannabis use disorder on suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury in Iraq/Afghanistan-Era veterans with and without mental health disorders. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 48, 140–148. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12345

Kimbrel, N. A., Thomas, S. P., Hicks, T. A., Hertzberg, M. A., Clancy, C. P., Elbogen, E. B., et al. (2018a). Wall/object punching: An important but under-recognized form of nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 48, 501–511. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12371

Kittel, J. A., DeBeer, B. B., Kimbrel, N. A., Matthieu, M. M., Meyer, E. C., Gulliver, S. B., et al. (2016). Does body mass index moderate the association between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and suicidal ideation in Iraq/Afghanistan veterans? Psychiatry Res. 244, 123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.039

Klonsky, E. D., and May, A. M. (2015). The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 8, 114–129. doi: 10.1521/icjt.2015.8.2.114

Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., and Saffer, B. Y. (2016). Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 12, 307–330. doi: 10.1116/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204

Kopacz, M. S., Currier, J. M., Drescher, K. D., and Pigeon, W. R. (2016). Suicidal behavior and spiritual functioning in a sample of veterans diagnosed with PTSD. J. Inj. Violence Res. 8, 6–14. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v8i1.728

Krysinska, K., and Lester, D. (2010). Post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide risk: A systematic review. Archives Suicide Res. 14, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/13811110903478997

Legarreta, M., Graham, J., North, L., Bueler, C. E., McGlade, E., and Yurgelun-Todd, D. (2015). DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms associated with suicide behaviors in veterans. Psychol. Trauma 7, 277–285. doi: 10.1037/tra0000026

Lehavot, K., Katon, J. G., Chen, J. A., Fortney, J. C., and Simpson, T. L. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder by gender and veteran status. Am. J. Preventative Med. 54, e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.008

Lemaire, C. M., and Graham, D. P. (2011). Factors associated with suicidal ideation in OEF/OIF veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 130, 231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.021

Louzon, S. A., Bossarte, R., McCarthy, J. F., and Katz, I. R. (2016). Does suicidal ideation as measured by the PHQ-9 predict suicide among VA patients? Psychiatric Services 67, 517–522. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500149

Magruder, K. M., Yeager, D., and Brawman-Mintzer, O. (2012). The Role of pain, functioning, and mental health in suicidality among Veterans Affairs primary care patients. Am. J. Public Health 102, S118–S124. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2011.300451

Maguen, S., Metzler, T. J., Bosch, J., Marmar, C. R., Knight, S. J., and Neylan, T. C. (2012). Killing in combat may be independently associated with suicidal ideation. Depress. Anxiety 29, 918–923. doi: 10.1002/da.21954

Matchar, D. B. (2012). Chapter 1: introduction to the methods guide for medical test reviews. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 27(Suppl 1), 4–10. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1798-2

Matthews, S., Spadoni, A., Knox, K., Strigo, I., and Simmons, A. (2012). Combat-exposed war veterans at risk for suicide show hyperactivation of prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate during error processing. Psychosom. Med. 74, 471–475. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f888f

May, A. M., and Klonsky, E. D. (2016). What distinguishes suicide attempters from suicide ideators? A meta-analysis of potential factors. Clin. Psychol. 23, 5–20. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12136

McKenzie, J. E., and Brennan, S. E. (2019). “Chapter 12: Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods,” in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0, eds J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, and V. A. Welch. Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

McKinney, J. M., Hirsch, J. K., and Britton, P. C. (2017). PTSD symptoms and suicide risk in Veterans: serial indirect effects via depression and anger. J. Affect. Disord. 214, 100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.008

McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Zandberg, L., Bryan, C. J., Gay, N., Yarvis, J. S., et al. (2017). Predictors of suicidal ideation among active duty military personnel with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 208, 392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.061

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and the P. R. I. S. M. A. Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Monteith, L. L., Bahraini, N. H., Matarazzo, B. B., Gerber, H. R., Soberay, K. A., and Forster, J. E. (2016). The influence of gender on suicidal ideation following military sexual trauma among Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychiatry Res. 244, 257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.036

Monteith, L. L., Holliday, R., Dorsey Holliman, B., Brenner, L. A., and Simonetti, J. A. (2020). Understanding female veterans' experiences and perspectives of firearms. J. Clin. Psychol. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22952. [Epub ahead of print].

Monteith, L. L., Holliday, R., Schneider, A. L., Forster, J. E., and Bahraini, N. H. (2019). Identifying factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts following military sexual trauma. J. Affect. Disord. 252, 300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.038

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Cha, C. B., Kessler, R. C., and Lee, S. (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol. Rev. 30, 133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002

Paley, B., Lester, P., and Mogil, C. (2013). Family systems and ecological perspectives on the impact of deployment on military families. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 16, 245–265. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0138-y

Panagioti, M., Gooding, P. A., Triantafyllou, K., and Tarrier, N. (2015). Suicidality and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 50, 525–537. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0978-x

Pietrzak, R. H., Goldstein, M. B., Malley, J. C., Rivers, A. J., and Southwick, S. M. (2010). Structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and psychosocial functioning in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Psychiatry Res. 178, 323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.039

Polusny, M. A., Kumpula, M. J., Meis, L. A., Erbes, C. R., Arbisi, P. A., Murdoch, M., et al. (2014). Gender differences in the effects of deployment-related stressors and pre-deployment risk factors on the development of PTSD symptoms in National Guard Soldiers deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J. Psychiatr. Res. 49, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.09.016

Pompili, M., Sher, L., Serafini, G., Forte, A., Innamorati, M., Dominici, G., et al. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide risk among veterans: A literature review. J. Nervous Mental Disorders 201, 802–812. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a21458

Reimann, C. A., and Mazuchowski, E. L. (2018). Suicide rates among active duty service members compared with civilian counterparts, 2005-2014. Mil. Med. 183, 396–402. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usx209

Ribeiro, J. D., Pease, J. L., Gutierrez, P. M., Silva, C., Bernert, R. A., Rudd, M. D., et al. (2012). Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049

Sadler, A. G., Mengeling, M. A., Cook, B. L., and Torner, J. C. (2020). Factors associated with U.S. military women keeping guns or weapons nearby for personal security following deployment. J. Women's Health. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8029. [Epub ahead of print].

Shen, Y. C., Cunha, J. M., and Williams, T. V. (2016). Time-varying associations of suicide with deployments, mental health conditions, and stressful life events among current and former US military personnel: A retrospective multivariate analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1039–1048. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30304-2

Simonetti, J. A., Dorsey Holliman, B., Holliday, R., Brenner, L. A., and Monteith, L. L. (2020). Correction: firearm-related experiences and perceptions among United States male veterans: a qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE 15:e0231493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231493

Skopp, N. A., Trofimovich, L., Grimes, J., Oetjen-Gerdes, L., and Gahm, G. A. (2012). Relations between suicide and traumatic brain injury, psychiatric diagnoses, and relationship problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2009. MSMR 19, 7–11.

Smith, P. N., Currier, J., and Drescher, K. (2015). Firearm ownership in veterans entering residential PTSD treatment: Associations with suicide ideation, attempts, and combat exposure. Psychiatry Res. 229, 220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.031

Spicer, R. S., and Miller, T. R. (2000). Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. Am. J. Public Health 90, 1885–1891. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1885

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Marx, B. P., and Reger, M. A. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder and firearm ownership, access, and storage practices: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12358. [Epub ahead of print].

Street, A. E., Vogt, D., and Dutra, L. (2009). A new generation of women veterans: stressors faced by women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.007

Suris, A., Link-Malcolm, J., and North, C. S. (2011). Predictors of suicidal ideation in veterans with PTSD related to military sexual trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 24, 605–608. doi: 10.1002/jts.20674

Thomas, B. H., Ciliska, D., Dobbins, M., and Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 1, 176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

Vasterling, J. J., Proctor, S. P., Friedman, M. J., Hoge, C. W., Heeren, T., King, L. A., et al. (2010). PTSD symptom increases in Iraq-deployed soldiers: comparison with nondeployed soldiers and associations with baseline symptoms, deployment experiences, and postdeployment stress. J. Trauma. Stress 23, 41–51. doi: 10.1002/jts.20487

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, suicide, military personnel, veteran, systematic review

Citation: Holliday R, Borges LM, Stearns-Yoder KA, Hoffberg AS, Brenner LA and Monteith LL (2020) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Self-Directed Violence Among U.S. Military Personnel and Veterans: A Systematic Review of the Literature From 2010 to 2018. Front. Psychol. 11:1998. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01998

Received: 30 March 2020; Accepted: 20 July 2020;

Published: 26 August 2020.

Edited by:

Moshe Bensimon, Bar-Ilan University, IsraelReviewed by:

Leah Shelef, Israeli Air Force, IsraelMichela Bonafede, National Institute for Insurance Against Accidents at Work (INAIL), Italy

Eyal Fruchter, Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Israel

Copyright © 2020 Holliday, Borges, Stearns-Yoder, Hoffberg, Brenner and Monteith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ryan Holliday, cnlhbi5ob2xsaWRheUB2YS5nb3Y=

Ryan Holliday

Ryan Holliday Lauren M. Borges

Lauren M. Borges Kelly A. Stearns-Yoder

Kelly A. Stearns-Yoder Adam S. Hoffberg

Adam S. Hoffberg Lisa A. Brenner

Lisa A. Brenner Lindsey L. Monteith1,2

Lindsey L. Monteith1,2