- Department of Creative Arts Therapies, College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

In this paper, we present a review of research on the role of traditional and indigenous forms of visual artistic practice in promoting physical health and psychosocial well-being, particularly as it relates to the discipline of art therapy. Using extant literature we present an overview of how art making has historically had a therapeutic role in human lives and how it can inform the modern interpretation and profession of art therapy. Thereafter, we provide a critical review of specific studies that reference traditional and indigenous art forms in art therapy in order to invite discussion, dialogue, and awareness of the role of the arts in human development and the therapeutic role of the arts. Gaps in research areas for further study are proposed. Implications for clinical practice including expanding the scope of traditional forms of creative self-expression and promoting an informed and respectful understanding of the role of these artforms in the profession of art therapy worldwide, are also discussed.

Introduction

Artistic expression has historically and simultaneously evolved as a part of human civilizations around the world (Dutton, 2010). Many scholars assert that art making is an integral part of human functioning and would not have evolved or been a sustained part of human existence if it did not serve a significant adaptive purpose (Dutton, 2010; Davies, 2012; Kaimal, 2019). These scholars argue that art and art making have identified roles in evoking emotions, problem solving, imagination, memorializing life events, and enabling non-verbal communication (Dissanayake, 2000; Dutton, 2010; Winner, 2018). Dissanayake (2000) for example, identified art making as being integral to humans in establishing rituals and communication as well as, in “making special” key events and milestones in the lives of individuals in communities. There has, however, been limited examination of the therapeutic role of the arts in helping individuals cope in response to challenges including deriving strength from individual creative capacity and sense of community.

In the present day, mental health issues are a worldwide challenge: The World Health Organization (2019) cautioned that lack of mental well-being is a leading cause of disease burden around the world, with one-fourth of the global population at risk of developing a mental health challenge in their lifetime and one-fifth of children and adolescents having mental health problems. Wars, adversity, discrimination, illness, and natural disasters further exacerbate these unmet needs of psychosocial support. Most parts of the world have very limited resources and few skilled professionals to support mental health and well-being.

Building on the idea of the universal presence of artistic practices and the mental health needs of our modern world, therapeutic approaches in art therapy have been theorized to be embedded in our evolutionary survival instincts including responding to threats and making choices to ensure safety and belonging (Kaimal, 2019). Facilitation of creative visual self-expression to promote mental health and overall well-being is the goal of professional art therapists. The modern profession of art therapy originated in the United States and Europe in the twentieth century as a restorative practice that allowed for self-expression in non-verbal ways like drawing and painting. In particular, the profession began by serving the needs of veterans from the two World Wars who were suffering from post-traumatic stress and to address the development of children with special needs (Junge, 2010). The American Art Therapy Association currently defines art therapy as an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active art making, creative processes, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship (American Art Therapy Association, 2018). Given its origins, art therapy has been a very Western field and has been critiqued for its lack of diversity and limited understanding of the range of artistic practices around the world (Joseph, 2006; Moon, 2010; Talwar, 2010). Recent scholarly and artistic endeavors are beginning to explore indigenous knowledge and insight developed through generations of observations and deep understanding of nature and natural processes (Langlois, 2018; Whiting, 2018). There is increasing awareness of the value of traditional healing practices, including narrative storytelling (Gotschall, 2013; Duff, 2018) and integrating cultural practices like sweat lodges in medical hospitals (Center for Mental Health, 2019). Huotilainen et al. (2018) highlighted the role of arts and crafts in building community and feelings of wellness through flow states (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) induced during art making. James (2019) further highlighted the return to traditional artistic practices like embroidery as a means to cope, for example, among migrant women facing adversity and despair.

At the same time, it is important to recognize how knowledge about human development and the conceptualizations of traditional art making relate to contemporary society and an understanding of therapeutic art making and arts for health and well-being (Pascoe, 2015). Although, knowledge is also limited about the role specifically of visual expressive traditions in health and well-being, there is a need to help develop approaches to diversity in art therapy practice and reduce the likelihood of culturally misinformed or ill-suited Western imperialist approaches to treatment (Kleinman, 1981; Whitaker, 2002). There is a need to be better informed such that cultural forms of expression are not appropriated incorrectly; efforts to use them are respectful of local cultural and spiritual traditions; and; are adapted into materials, media, and art therapy approaches as sensitively and ethically as possible (Fincher, 1991; Kaimal, 2015; Iyer, 2018). This indigenous knowledge (Chilisa, 2012; Pascoe, 2015) highlights the importance of traditional wisdom and insight, including the close interaction of artistic practice with natural materials, creative agency, and contemplative and spiritual meaning making (Franklin, 2017) while recognizing our interconnectedness with other living beings in nature (Pascoe, 2015; Nagarajan, 2018).

The purpose of this mini review paper is to invite critical review, discussion, dialogue, and awareness on the therapeutic role of the arts, in order to expand the scope of traditional approaches to creative expression and promote an understanding of the role of integrating the arts and the profession of art therapy worldwide with traditional knowledge and wisdom. Inspired by the authors’ own artistic heritage from India and Turkey, we sought to better understand the existing literature on the use of traditional and indigenous artforms in art therapy practice.

Approaches in Art Therapy Using Traditional and Indigenous Art Forms

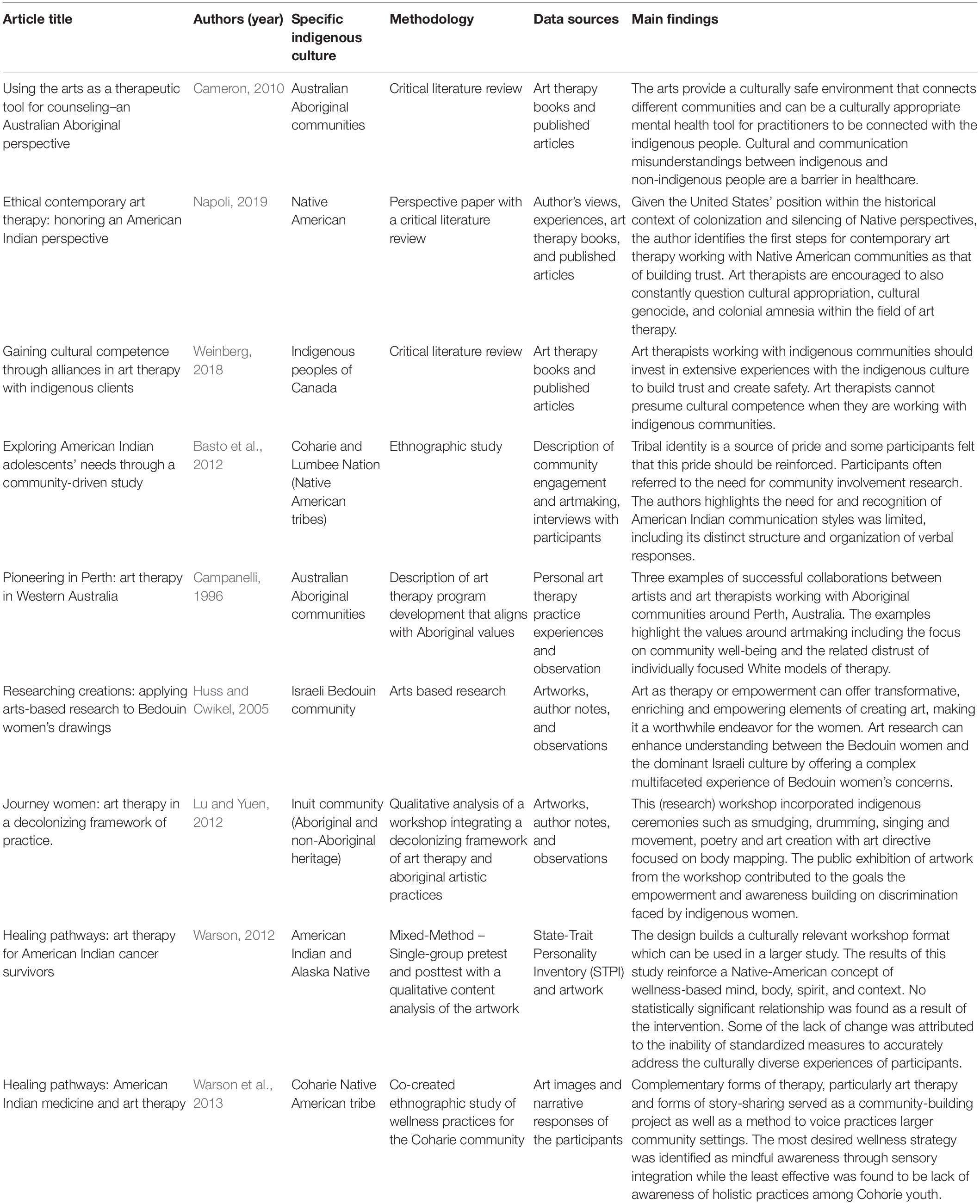

The databases searched for literature review included PubMed, JSTOR Google Scholar, and Elsevier Science Direct. Search terms used were, “indigenous,” “traditional,” “art therapy,” “creativity,” and “healing.”Google scholar provided the most references. We didn’t limit the year of publication but the language of source was limited to English. The search yielded nine peer-reviewed articles that referenced art therapy and indigenous arts practices. Book chapters were not included in this review. The nine papers included theoretical and critical perspectives (Cameron, 2010; Weinberg, 2018; Napoli, 2019) as well as community and ethnographic methodologies (Campanelli, 1996; Huss and Cwikel, 2005; Basto et al., 2012; Lu and Yuen, 2012; Warson, 2012; Warson et al., 2013). A brief overview of these art therapy articles is included in Table 1 and also summarized below.

Table 1. Peer reviewed journal articles addressing indigenous and traditional art practices in the discipline of art therapy.

The three theoretical perspective papers highlighted the differences in understanding of healing between the indigenous and Western societies (Cameron, 2010; Weinberg, 2018; Napoli, 2019). Cameron (2010) discussed how indigenous healing was informed by holistic understanding of the individual, including the “social, physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and cultural states of being” (Cameron, 2010, p. 404). Cameron (2010) further states that indigenous Australians consider art as a daily practice of meaning making rather than an artistic ideal. Further referencing communication difficulties and cultural misunderstandings that can occur between the art therapist and the indigenous client, Weinberg (2018) highlighted the importance of cultural appropriateness in art therapy when working with indigenous clients. Reflecting on the historical mistrust of indigenous people toward non-indigenous health-care providers, Weinberg (2018) suggested that art therapists consider cultural barriers and recommended partnering with indigenous mentors when practicing in an indigenous-focused art therapy program. In line with this argument, Cameron (2010) also underlined that utilizing indigenous artistic expressions in therapy acknowledges cultural inclusion and aids cross-cultural communication. When serving indigenous communities, the non-indigenous therapist should gain cultural competency, learn about trans-generational history, recognize social values and create culturally safe spaces in order to provide best practices (Cameron, 2010; Weinberg, 2018). In a strong critique of misappropriation of healing traditions, Napoli (2019) draws attention to the disrespect of American Indian traditions and practices and misuse of Native American healing systems in art therapy. For example, Napoli (2019) references the misappropriation of Native American spiritual and shamanistic practices in art therapy (McNiff, 1981). She highlights the need for culturally informed and respectful practices.

In addition to the perspective papers above, six papers used qualitative, participatory, mixed methods, and ethnographic methodologies to examine the role of art therapy practices in indigenous communities in Australia, Canada, Israel and the United States.

Campanelli (1996), underlined the importance of arts engagement for cultural restoration for Aboriginal health and well-being in Australia. His clinical work in building a community-based art therapy program in Perth, the capital city of Western Australia, highlighted the functions of Aboriginal art in cultural healing, including community involvement, cultural restoration, and recovery, as well as maintaining hope and wholeness (Campanelli, 1996). Indigenous individuals referenced taking cultural pride in being members of their community and reproducing symbols of this belonging through art making which further strengthened their sense of belonging (Campanelli, 1996; Basto et al., 2012). Campanelli (1996) highlights in particular the distrust of individualistic White approaches to health which might be perceived as a an extension of the history of oppression of aboriginal peoples in Australia, but that respectful engagement through art could be the bridge. Lu and Yuen (2012) reported on a women’s program that they developed in Canada for First Nation, Inuit, and Métis women using a decolonizing framework of practice, in order to “empower and inform people in their healing journey” (Lu and Yuen, 2012, p. 192). The authors introduced a body-mapping technique that combined art therapy with traditional practices such as drumming, prayers and smudging and in collaboration with the community refer to the research efforts as a “ceremonial event” (p. 193). Based on interviews with the participants, the authors concluded that the initiative resulted in increased feelings of empowerment, creativity, and collective strength among the participants (Lu and Yuen, 2012).

In Israel, Huss and Cwikel (2005) examined the role of art therapy and arts-based research when working with Bedouin women living in Israel. Through the use of visual data gathering tools (paper, oil pastels, color pencils, and wet paint) of arts based research inquiry, they reported that art making was a “worthwhile tool for empowerment, that can transform, enrich, and empower” the Bedouin women participants in their study (Huss and Cwikel, 2005, p. 59).

In the US, three studies examined the role of art making as a medium for community building through addressing cultural practices American Indian Coharie people. Warson et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative ethnographic study with the Coharie people in the US to emphasize the importance of a culturally relevant co-created workshop format for restoring traditional wellness approaches. The authors used a qualitative ethnographic model, incorporating community participation and recruited 44 members from the Coharie tribe. The art workshops combined with holistic healing practices provided a community building opportunity as well as a space to voice cultural practices that were not previously discussed. Another qualitative ethnographic study with Coharie adolescents highlighted that art workshops increased community involvement and was a protective factor for American Indian youth (Basto et al., 2012). Lastly, Warson (2012) study explored the impact of culturally aligned art-based interventions on stress reduction for Native American cancer patients. Her research also provided an example for cultural considerations in assessment procedures. She utilized the State-Trait Personality Inventory (STPI) which is an assessment drawn from STAI assessment, a widely used and validated measure for Western participants. However, even after several modifications to make the inventory more culturally applicable, the authors reported that inventory was found to not be suitable for the Coharie tribe, highlighting the limitations of using some standardized psychological measures in this context.

In summary, the few studies in art therapy reviewed above highlight the opportunities for empowerment and community building as well as the challenges of working from the Western perspectives of individual clinical diagnostic categories in art therapy research and clinical practices.

Discussion

In this paper we provided a systematic review peer-reviewed literature on how art therapists have integrated traditional and indigenous artforms into their practice as well as preliminary efforts to conduct research on the topic. Overall the literature indicates that the therapeutic aspects of indigenous forms for visual arts practice are deeply interconnected with spiritual traditions, narrative storytelling, counseling and wisdom for the community, respect of all things living and non-living in nature, using natural and locally available materials as well as creating products that are sustainable. Undergirding all interactions with indigenous communities is the need for the recognition of trauma and misrepresentation that resulted from cultural imperialism and oppression, leading to a historical mistrust in the indigenous communities of outsider interventions. Talwar (2015) further highlights that issues around understanding multiculturalism can be meaningfully tackled within the context of historical representations of minority cultures within the culture in power. With this literature review we present a preliminary understanding of issues around working in indigenous settings and traditional materials that need further examination including implications for clinical practice and research approaches.

Clinical Implications for Art Therapy

Art therapists interested in working with indigenous art forms or with indigenous communities need to first and foremost consider several aspects of their own identity and what they represent to indigenous communities. These include acknowledging personal motivations, power, and privilege; and willingness to reflect on personal history and its intersection with the colonial oppression, trauma, and multi-generational discrimination faced by most indigenous communities. Cultural awareness, knowledge, and humility are essential values in providing competent services, especially in culturally diverse indigenous settings. Given that there are now increasing numbers of art therapists working with people of diverse cultures both in their home country and abroad (Talwar, 2015), cultural competency (Sue, 2006) has been discussed in art therapy literature including in relation to making an effort and having an open attitude to learn the culture, being self-reflexive about one’s own biases and having a culturally humble stance to different values, beliefs, background (Ter Maat, 2011; Kapitan, 2015; Talwar, 2015; Potash et al., 2017). A related construct of cultural humility might serve art therapists well when working with traditional and indigenous artistic practices. Reflecting on one’s own cultural biases is a central value in the cultural humility framework. A culturally humble therapist examines their own cultural beliefs and identities and acknowledges their privileged position in the therapeutic relationship (Tervalon and Murray-Garcia, 1998). While being reflective and self-critical, the therapist should also be attentive to systemic forms of privilege and power in order to understand the oppressive mechanisms that can impact a client (Bal and Kaur, 2018). When therapists are perceived by the client as being respectful, interested, open and considerate, they are more likely to have better working alliances and improvements in therapeutic outcomes (Hook et al., 2013). This inclusive and culturally humble stance allows clinician to access the knowledge about culture without alienating the client (Bal and Kaur, 2018; Jackson, 2020). It is necessary for the art therapist to be familiar with the culture-specific media, technique and artistic philosophy. However, even when the art therapist feels competent in knowing the culture, the client is the expert on the culture of their specific community. Viewing the client as the expert and the teacher of their own culture validates and empowers the client to be more open when sharing their stories (Campanelli, 1996; Jackson, 2020). Art therapists might further explore and reflect on the artistic practices of their own heritage to better understand the meaning and health implications underlying creative practices.

Beyond the positioning of the art therapist, a key consideration in indigenous communities is the need to recognize that art making is often an integral part of the cultural system of the community, often with specific roles assigned by age and/or gender as well as valuing the interrelatedness of all things in nature (Campanelli, 1996). For example, traditional textiles including knitting, crocheting, weaving, embroidery, etc. tend to have historically be made by women but have also been found to forms of effective coping in the modern world (Collier, 2011). Other forms of woodwork, metalwork, fabric dying, etc. might be associated more with men’s roles and awareness of these traditional roles need to be recognized when interacting in the community (Kaimal et al., 2016). Kapitan (2015) discusses art therapy as a cultural practice, especially when working with marginalized cultures, acknowledging the risks of ethnocentric bias when we consider art making as a universal, non-verbal communication tool. In our review, we encountered studies and workshops where art therapists have tried to incorporate cultural practices such as the use of holistic healing practices. Such practices have included connecting an art therapy directive with existing artistic practices smudging, drumming and prayers in the therapy session (Lu and Yuen, 2012; Warson, 2012) with the goals of addressing specific health promoting goals in a non-hierarchical participatory way. When bringing art therapy into indigenous settings, art therapists need to co-create and work alongside a community mentor or leader in order to find culturally contextualized solutions to identified challenges in the problems in the community (Campanelli, 1996; Huss et al., 2015; Weinberg, 2018). Locating the meaning and value of art in the specific culture will allow art therapists to expand out of their own value systems and understand art making as a context-specific cultural phenomenon (Huss et al., 2015). The significance of culturally sensitive and relevant art therapy when working with indigenous clients was highlighted by several authors (Warson et al., 2013; Weinberg, 2018). The arts are an inherently valued source of community well-being (Campanelli, 1996) and in order to provide culturally relevant art therapy, the therapist needs to include the related learning norms and communication styles and avoid cultural misunderstandings (Ter Maat, 2011).

In addition to art therapists, artists, therapists, and healers have been practicing community healing programs that integrates traditional arts. For example, Archibald et al. (2010) conducted a survey with 137 Aboriginal foundations to investigate the use of creative arts relative to healing with first nation, Inuit and Metis healing programs in Canada. The self-report data showed that the use of creative arts in the aboriginal healing programs can make a meaningful contribution to the self-development, feeling personal and cultural safety, well-being and improved social relations. Lindeman et al. (2017) comprehensive literature concluded that art programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Australians living with dementia play a vital role in maintaining culture and traditional practices. Studies such as these indicate that art making can play a role as a protective factor; it can strengthen the community ties and increase self-esteem, elevate mood and change perception of pain, which can be of tremendous benefit for the indigenous communities (de Guzman et al., 2010; Muirhead and De Leeuw, 2013). Although these programs are not art therapy, they suggest positive health outcomes.

Incorporating traditional knowledge not only helps the indigenous community receive better care, but it may also offer therapeutic benefits to wider populations. Depending on the context, the use of culture-specific materials and forms of expression may be a better choice instead of conventional art therapy media. However, when bringing traditional art forms and materials outside of the cultural context, it is important to consider the dangers of cultural misappropriation. Even if the art therapist is well-informed, sensitive and ethical in their adaptation of cultural media and techniques into the therapeutic practice, and, is from the same cultural background, clients may not feel safe if there are conflicting assumptions around what is a culturally appropriate media or technique. This can potentially construct a superficial understanding of culture and help maintain already existing stereotypes. As Napoli (2019) highlights an art form or material may be profoundly significant to the original culture but when it is removed from the cultural context, the original meaning may get lost or worse, misrepresented. However, this doesn’t mean art therapists shouldn’t incorporate culture-specific art. The therapist can take an approach of being a partner in co-creating wellness, recognizing the interrelationships of all aspects of the community in creative practices, modeling respect and humility to counter the historic mistrust of indigenous communities toward the Western approaches to healthcare (Campanelli, 1996; Weinberg, 2018).

Suggestions for Future Research

Throughout this paper, we have highlighted the potential ethical considerations of incorporating traditional knowledge and creative practices into the profession of art therapy. However, the literature review suggests a pronounced need for further research especially on culturally responsive methodologies. In particular the wisdom on traditional approaches needs to be unpacked in order to better understand the underlying knowledge systems. Traditional and indigenous knowledge systems are founded on generations of observations a deep understanding of culture and context specific needs health needs. These values are often at odds with the individually focused health ideals of modern Western medicine and therapies. Clinicians can identify which community characteristics play a role in leading to therapeutic outcomes by comparing intercultural responses to adapting certain traditional knowledge into art therapy. For instance, incorporating holistic knowledge into a practicing monotheistic community may require different considerations than incorporating holistic knowledge into communities which religion may have a belief systems. Working across disciplinary boundaries with artists and traditional healers would also be an area of further inquiry for art therapy researchers.

Given historical experiences of oppression and justifiable mistrust of external entities, appropriate methods are a major consideration as cautioned by Warson (2012) and Weinberg (2018). Using storytelling traditions, reflective and participatory methods, recognizing appropriate community-led engagement are essential to research in this topic. In addition specific approaches and questions might require age and gender related adaptations to align with the values of the community. Moreover, future research in art therapy and indigenous communities can benefit from methodologies that accurately and appropriately measure outcomes. Outcome measures such as standardized tests should be either adapted to the specific culture or replaced with other culturally acceptable data collection tools. Understanding the interplay between individual and community well-being and how artmaking effectively helps promote this intergration is an area for further study. Researchers interested in this work, need to begin first by reflecting on personal biases, exploring the challenges and concerns around misappropriation and cultural humility in integrating indigenous practices. Further research is needed to better understand whether and how to implement traditional artistic practices in art therapy including identifying ethical standards that are acceptable to the community for both engagement and research.

Limitations and Conclusion

In this paper we provided an overview of the literature on the intersection of art therapy and indigenous and traditional artforms. The existing literature offers preliminary guidance but further research is needed to address the challenges of mistrust of individually focused Western approaches to health, while indigenous communities value interdependence as key to well-being. The solutions lie in the artistic practices themselves since indigenous art media and techniques can offer cultural safety and acknowledgment for the local communities. In addition art therapist may consider revisiting cultural humility framework, recognize the historical trauma and disenfranchisement experienced by many indigenous communities and approach their work through a participatory model of co-creation.

Author Contributions

GK contributed to the overall framework for the manuscript as well as discussion sections. AA contributed to the literature review and writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted with funding support from Drexel University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

American Art Therapy Association (2018). About Art Therapy. Avaliable at: www.arttherapy.org (accessed April 2, 2020).

Archibald, L., Dewar, J., Reid, C., and Stevens, V. (2010). Rights of Restoration: aboriginal peoples, creative arts, and healing. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 23, 2–17. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2010.11432334

Bal, J., and Kaur, R. (2018). Cultural humility in art therapy and child and youth care: reflections on practice by sikh women (L’humilité culturelle en art-thérapie et les soins aux enfants et aux jeunes: réflexions sur la pratique de femmes sikhes). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 31, 6–13. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2018.1454096

Basto, E., Warson, E., and Barbour, S. (2012). Exploring American Indian adolescents’ needs through a community-driven study. Arts Psychother. 39, 134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.02.006

Cameron, L. (2010). Using the arts as a therapeutic tool for counselling–an Australian Aboriginal perspective. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 5, 403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.112

Campanelli, M. (1996). Pioneering in perth: art therapy in western Australia. Art Ther. 13, 131–135. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1996.10759209

Center for Mental Health (2019). Toronto Hospital OPENS sweat Lodge for Aboriginal Patients. Avaliable online at: http://www. whitewolfpack.com/2016/06/toronto-hospital-opens-sweat-lodge-for.html? fbclid=IwAR2Rk3Dq-EavL5YoyIM4Tzs_dERi6W92vTu2onRlDBQA96A8 YUHk3TM81-U&m=1 (accessed January 9, 2020).

Collier, A. F. (2011). The well-being of women who create with textiles: implications for art therapy. Art Ther. 28, 104–112. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2011.597025

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

de Guzman, A. B., Santos, J. I. M., Santos, M. L. B., Santos, M. T. O., Sarmiento, V. V. T., Sarnillo, E. J. E., et al. (2010). Traditional Filipino arts in enhancing older people’s self-esteem in a penal institution. Educ. Gerontol. 36, 1065–1085. doi: 10.1080/03601270903534713

Dissanayake, E. (2000). Art and Intimacy: How the Arts Began. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Duff, M. (2018). In narrative Therapy, Maori Creation Stories Are Being Used to Heal. Avaliable at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/102115864/in-narrative-therapy-mori-creation-stories-are-being-used-to-heal (accessed March 9, 2018).

Dutton, D. (2010). The art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Fincher, S. F. (1991). Creating Mandalas for Insight, Healing, and Self-Expression. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Franklin, M. F. (2017). Art as Contemplative Practice: Expressive Pathways to the Self. Albany, NY: SUNY.

Gotschall, J. (2013). The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make us Human. Wilmington, MA: Mariner Books.

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington, E. L. Jr., and Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J. Counsel. Psychol. 60, 353–366. doi: 10.1037/a0032595

Huotilainen, M., Rankanen, M., Groth, C., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., and Makela, M. (2018). Why our brains love arts and crafts. Res. J. Design Design Educ. 11, 1–17. doi: 10.7577/formakademisk.1908

Huss, E., and Cwikel, J. (2005). Researching creations: applying arts-based research to bedouin women’s drawings. Int. J. Q. Methods 4, 44–62. doi: 10.1177/160940690500400404

Huss, E., Kaufman, R., Avgar, A., and Shouker, E. (2015). Using arts-based research to help visualize community intervention in international aid. Int. Soc. Work 58, 673–688. doi: 10.1177/0020872815592686

Iyer, M. (2018). Rangoli, Culture and Art Therapy: Integrating a Tradition Within Clinical Practice. Master’s thesis, LaSalle University, Singapore.

Jackson, L. (2020). Cultural Humility in Art Therapy: Applications for Practice, Research, Social Justice, Self-Care, and Pedagogy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

James, V. L. (2019). Migrant Women Fleeing Violence Find Beauty and Healing in Embroidery. Washington, DC: American Magazine.

Joseph, C. (2006). Creative alliance: the healing power of art therapy. Art Ther. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 23, 30–33. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2006.10129531

Junge, M. B. (2010). The Modern History of art Therapy in The United States. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Kaimal, G. (2015). Evolving identities: the person(al), the profession(al) and the artist(ic). Art Ther. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 32, 136–141. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1060840

Kaimal, G. (2019). Adaptive response theory (ART): a clinical research framework for art therapy. Art Ther. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 36, 215–219. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2019.1667670

Kaimal, G., Gonzaga, A. M. L., and Schwachter, V. (2016). Crafting, health and well-being: national trends and implications for art therapists. Arts Health 9, 81–90. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2016.1185447

Kapitan, L. (2015). Social action in practice: shifting the ethnocentric lens in cross-cultural art therapy encounters. Art Ther. 32, 104–111. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1060403

Kleinman, A. (1981). Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland Between Anthropology, Medicine and Psychiatry. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Langlois, K. (2018). Why Scientists are Beginning to Care About Cultures That Talk to Whales. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Mag.

Lindeman, M., Mackell, P., Lin, X., Farthing, A., Jensen, H., Meredith, M., et al. (2017). Role of art centres for aboriginal australians living with dementia in remote communities. Austr. J. Ageing 36, 128–133. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12443

Lu, L., and Yuen, F. (2012). Journey women: art therapy in a decolonizing framework of practice. Arts Psychother. 39, 192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.12.007

Moon, C. H. (2010). “Theorizing materiality in art therapy,” in Materials and Media in Art Therapy: Critical Understandings of Diverse Artistic Vocabularies, ed. C. H. Moon (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–49.

Muirhead, A., and De Leeuw, S. (2013). Art and Wellness: The Importance of art for Aboriginal Peoples’ Health and Healing. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. (accessed May 2, 2020).

Nagarajan, V. (2018). Feeding a Thousand Souls: Women, Ritual and Ecology in India, an Exploration of the Kôlam. London: Oxford University Press.

Napoli, M. (2019). Ethical contemporary art therapy: honoring an american indian perspective. Art Ther. 36, 175–182. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2019.1648916

Potash, J. S., Bardot, H., Moon, C. H., Napoli, M., Lyonsmith, A., and Hamilton, M. (2017). Ethical implications of cross-cultural international art therapy. Arts Psychother. 56, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.08.005

Sue, S. (2006). Cultural competency: from philosophy to research and practice. J. Commun. Psychol. 34, 237–245. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20095

Talwar, S. (2010). An intersectional framework for race, class, gender, and sexuality in art therapy. Art Ther. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 27, 11–17. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2010.10129567

Talwar, S. (2015). Culture, diversity, and identity: from margins to center. Art Ther. 32, 100–103. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1060563

Ter Maat, M. B. (2011). Developing and assessing multicultural competence with a focus on culture and ethnicity. Art Ther. 28, 4–10. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2011.557033

Tervalon, M., and Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J. Health Care Poor Underser. 9, 117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

Warson, E. (2012). Healing pathways: art therapy for American Indian cancer survivors. J. Cancer Educ. 27, 47–56. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0324-5

Warson, E., Taukchiray, W., and Barbour, S. (2013). Healing pathways: American Indian medicine and art therapy. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 26, 33–38. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2013.11415584

Weinberg, T. (2018). Gaining cultural competence through alliances in art therapy with indigenous clients (La compétence culturelle et son acquisition grâce à des alliances avec des clients autochtones en art-thérapie). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 31, 14–22. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2018.1453214

Whiting, J. (2018). Resonance Between Indigenous Art and Images Captured by Microscope. Avaliable at: http://theconversation.com/the-resonances-between-indigenous-art-and-images-captured-by-microscopes-105120 (accessed October 1, 2018).

Winner, E. (2018). How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

World Health Organization (2019). Mental health: strengthening our response. Avaliable at: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/.

Keywords: indigenous, traditional, healing, well-being, art therapy

Citation: Kaimal G and Arslanbek A (2020) Indigenous and Traditional Visual Artistic Practices: Implications for Art Therapy Clinical Practice and Research. Front. Psychol. 11:1320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01320

Received: 06 March 2020; Accepted: 19 May 2020;

Published: 16 June 2020.

Edited by:

Johanna Czamanski-Cohen, University of Haifa, IsraelReviewed by:

Michal Bat Or, University of Haifa, IsraelEphrat Huss, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel

Copyright © 2020 Kaimal and Arslanbek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Girija Kaimal, Z2lyaWphLmthaW1hbEBwb3N0LmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

Girija Kaimal

Girija Kaimal Asli Arslanbek

Asli Arslanbek