95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 23 June 2020

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01289

This article is part of the Research Topic Advancing Social Purpose in Organizations: An Interdisciplinary Perspective View all 14 articles

Research on the role of public service motivation (PSM) relating to work performance has been a significant topic in recent years; however, the relationship between PSM and job performance remains mixed. To investigate whether job attitudes mediate the effect of PSM on public employees’ turnover intention, this study integrated job satisfaction and organizational commitment into a single model. Based on a sample of 587 full-time Chinese public employees, our findings revealed that job satisfaction and organizational commitment, respectively, mediated the negative association between PSM and employees’ turnover intention. Multiple mediation analysis indicated that job satisfaction and organizational commitment sequentially mediated the effects of PSM on turnover intention. As a result, our findings suggested that public employees with high PSM levels preferred to stay in the public organizations. The theoretical and practical implications of our findings are discussed.

Perry and Wise (1990) argued that individuals with high levels of public service motivation preferred to seek a job within the public sector and to perform better in public sector work. Subsequently, a stream of empirical studies has focused on the relationship between PSM and job performance (Kim, 2012; Shim et al., 2017; Choi and Chun, 2018; Jin et al., 2018; Miao et al., 2019; Caillier, 2020). A substantial amount of literature has laid stress on the significance of PSM in boosting job performance, but “the role of intermediate variables, mediating the relationship between PSM and performance, is still unclear” (Perry et al., 2010). In PSM literature, there are two research perspectives on whether individual PSM is negatively related to their intentions to stay in the public sector. Some studies have explored the direct effect of PSM on employees’ turnover intention (Alonso and Lewis, 2001; Andersen and Søren, 2012; Choi and Chun, 2018), but more recent research has shed light on the link between PSM and turnover intention which was mediated by intermediate variables, including the person-organization fit (Bright, 2008; Kim, 2012; Gould-Williams et al., 2015), organizational commitment (Vandenabeele, 2009; Jin et al., 2018), organizational identification (Miao et al., 2019), social impact potential (van Loon et al., 2018) and meaningfulness of work (Zheng et al., 2020). However, the causality between PSM and turnover intention remains highly disputed. For example, findings by Bright (2008) confirmed a non-significant association between PSM and employees’ turnover intention, which was consistent with the results of Alonso and Lewis (2001). In contrast to Bright, some recent results have revealed that the relationship between PSM and employees’ job performance is significant when some mediators (e.g., P-O fit or organizational commitment) are taken into account (Kim, 2012; Gould-Williams et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018).

In a word, most of the existing PSM literature does not provide strong evidence for the association between PSM and turnover intention. Furthermore, prior scholars have stressed the dominant role of P-O fit in the connection between PSM and employees’ work-related outcomes (Kim, 2012; Gould-Williams et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018), but they have largely ignored the effects of other mediating variables, such as work attitudes and behavior (Vandenabeele, 2009). Mathieu et al. (2016) noted that despite the critical role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in explaining turnover intention that has increasingly attracted attention in recent years, few studies have considered job satisfaction and organizational commitment together when presenting a structure turnover model. Therefore, it is essential to clarify the direct and indirect effects of PSM on employees’ turnover intention by incorporating mediators—job satisfaction and organizational commitment—into a single research model.

Our study aims to explore the effects of PSM on public employees’ turnover intention. The negative association between PSM and employees’ turnover intention has received little attention and demonstrated mixed findings (Bright, 2008; Kim, 2012; Jin et al., 2018). To investigate the inconsistent findings between PSM and employees’ turnover intention, researchers have laid stress on the cross-cultural comparison using diverse samples from different cultural context (Kim, 2017). Our study provides a new insight into the empirical research related to the links between PSM and turnover intention by shedding light on work-related behavior of Chinese public employees. As such, by focusing on Chinese public employees, our study extends the previous research that has been conducted with samples from Western countries. Another goal of the present study is to explore how public employees’ job attitudes mediate the effects of PSM on their turnover intention. To our knowledge, the current empirical findings revealed that the association between PSM and employees’ turnover intention was significantly mediated by employees’ P-O fit (Gould-Williams et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018). However, researchers have rarely taken into account the role of other mediators (e.g., job satisfaction and organizational commitment) when discussing employees’ turnover intention in the public sector (Vandenabeele, 2009). Thus, we propose a turnover model that integrates job satisfaction, organizational commitment, as well as turnover intention. In doing so, our findings stress the importance of mediating role of public employees’ job attitudes in predicting the impact of PSM on turnover intention.

The concept of PSM that originated from Perry and Wise (1990) refers to “an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions or organization.” The work of Perry and Hondeghem (2008) shows that individuals with a high level of PSM will select jobs in the public sector for the sake of public benefits. Alternatively, Vandenabeele (2007) saw PSM as “belief, value, and attitudes that go beyond self-interest and organizational interest, that concern the interest of a larger political entity and that motivate individuals to act accordingly whenever appropriate.” Furthermore, PSM can be viewed “as a specific type of prosocial motivation” or intrinsic motivation for public employees (Georgellis and Tabvuma, 2010; Ritz et al., 2020). Importantly, the concept of PSM has been discussed and used outside the public sector, because PSM is found in commercial settings (O’Leary, 2019). Therefore, scholars proposed more generalized concepts of PSM. For example, Rainey and Steinbauer (1999) defined PSM as a “general, altruistic motivation to serve the interests of a community of people, a state, a nation or humankind.” While PSM is originally viewed as a prosocial motivation to do good for others and the society within public sector (Perry and Wise, 1990; Hondeghem and Perry, 2009), it has been an increasing recognition that PSM has been a growing concern in various areas and is further discussed outside the public sector (Bozeman and Su, 2015; O’Leary, 2019).

As such, PSM can be described as “autonomous types of motivation” (Houston, 2011) that will play a key role in affecting individual work-related behaviors. These views indicate that both internal motives and external context play a vital role in determining individual work-related behaviors, such as job performance, work effort, and organizational performance (Bright, 2007; van Loon, 2017). Previous empirical studies have found that work-related attitudes and behaviors of public employees are closely connected with PSM (Perry and Wise, 1990; Bright, 2007; Leisink and Steijn, 2008). Generally speaking, many believe that individuals tend to work in the public organizations and report high job satisfaction, job performance, and organizational commitment when they have high PSM levels (Perry, 1996; Moynihan and Pandey, 2007). With a large sample of employees in the Italian National Health Service, Belle (2013) argued that PSM significantly increased job performance among public employees. More recently, the work of Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot (2017) showed that PSM was positively linked with public employees’ job outcomes, such as job satisfaction, affective commitment, and service quality.

Generally speaking, turnover intention refers to “probability of employees leaving their organization” (Wynen et al., 2013). Although previous studies have suggested that employees’ turnover intention is largely determined by economic, individual, and organizational factors (Moynihan and Landuyt, 2008), PSM theory fundamentally assumes that those people with high PSM levels prefer to “seek membership in a public organization” to obtain opportunities to promote public interests (Perry and Wise, 1990; Vandenabeele, 2008). Some earlier studies have found that PSM has no direct and significant impact on turnover intention (Kim and Lee, 2007; Bright, 2008); however, most recent empirical findings have confirmed the negative relationship between PSM and turnover intention in the public sector (Leisink and Steijn, 2008; Shim et al., 2017; Choi and Chun, 2018). Based on a sample of 4,974 street-level bureaucrats, Shim et al. (2017) revealed that the direct effect of PSM on employees’ turnover intention was negative and significant. Similarly, Choi and Chun (2018) concluded that individuals who attach importance to social equity and altruism were not likely to quit a job within the public sector. Actually, the negative effect of red tape on employees’ turnover intention can be mitigated by PSM because public employees with high PSM levels have less intention to leave their jobs within the public sector (Quratulain and Khan, 2015). However, the empirical study of Liu et al. (2011) revealed that “only a self-sacrifice dimension of PSM was positively related to occupational intention” to seek membership in a public organization. Based on the previous discussions, we expect that PSM will play a vital role in employees’ turnover intention because public employees with high-PSM are more willing to contribute to the interests of others and society. Thus, it leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: PSM is negatively correlated with public employees’ turnover intention.

According to Locke (1976), job satisfaction can be seen as “a pleasure or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experience.” An enormous amount of empirical research has explored the significance of job satisfaction and its consequences. According to the organizational equilibrium theory, employees intend to change jobs when they perceive that they have received less inducement from their organizations than their contributions to their job. Indeed, research has confirmed that employees’ job dissatisfaction increase their desirability to leave and, thereby, leads to a greater intent to leave (Huang et al., 2017; Zeffane and Melhem, 2017). With regard to its potential influence on organizations, job satisfaction generally has played a significant role in the decision of employees’ intention to quit, because it has been one of the “most critical predictors of turnover intention” (Choi and Chiu, 2017). At the organizational level, job satisfaction is closely related to the degree of absenteeism, job performance, turnover intention, and organizational citizenship behavior (Wright and Bonett, 2007). At the individual level, some empirical research revealed that job satisfaction had a positive relationship with individual life satisfaction, well-being, or mental health, but it also has a negative relationship with anxiety and depression (Christian et al., 2011; Zalewska, 2011). In the context of value pluralism, employees’ intention to leave the job not only is associated with work-relate factors, but it also is linked to personal cognition, such as career orientation, organizational identity, or job pressure. However, as an emotional state that resulted from job experience, job satisfaction plays an important role in work-related behaviors. To be specific, Khan and Aleem (2014) identified that job satisfaction was affected by salary, promotion opportunities, job security, or job demands and, thus, resulted in negative influences on an employee’s intention to leave the job. Obviously, employees will tend to change jobs when they are dissatisfied with the present jobs.

Although numerous work-related relevant factors can bring about job satisfaction, the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction has gained increased research attention in recent years (Wright and Pandey, 2008; Liu et al., 2015; Choi and Chun, 2018; Kjeldsen and Hansen, 2018). These results are based on the assumption that public organizations provide opportunities for those employees with high PSM levels to do good for others and society, which meets their altruistic needs and, subsequently, leads to higher job satisfaction (Perry et al., 2010; Andersen and Kjeldsen, 2013). Furthermore, the work of Kjeldsen and Andersen (2013) revealed that PSM is positively correlated with job satisfaction when employees perceive that “their jobs are useful to society and other people.” Consistent with Balfour and Wechsler’s earlier proposition, PSM has been identified as being directly and indirectly related to job satisfaction through the moderation of P-O fit (Liu et al., 2015; Kim, 2012). To be specific, based on empirical data collected in Chinese public sector, Liu et al. (2015) suggested that the impact of PSM on job satisfaction was significant if both P-O fit and needs-supplies fit were low. Similarly, using a sample of civil servants employed by local governments in Korea, Kim (2012) revealed that PSM was not only an important independent factor in job satisfaction, but it also had “an indirect effect on job satisfaction and organizational commitment through its influence on P-O fit.”

However, some earlier empirical research shows mixed findings regarding the association between PSM and job satisfaction. For example, Bright (2008) and Steijn (2008) argued that PSM has direct impact on work-related outcomes when P-O fit was considered. This was supported by Wright and Pandey (2008) who also claimed that PSM did not directly affect employees’ job satisfaction if P-O fit was integrated into the research model as a mediator. Nevertheless, most scholars argued that the effects of PSM on work-related outcomes could not be fully explained through P-O fit theory, because PSM theory had been widely validated within both public and private organizations (Christensen and Wright, 2011; Choi and Chun, 2018; Andersen and Kjeldsen, 2013). More recently, Taylor (2014) suggested that public employees “with high PSM levels tend to be more satisfied with their job than those with low PSM levels.” Further, Andersen and Kjeldsen (2013) findings also confirmed that the direct and positive effect of PSM on job satisfaction was significant in both public sector and private sector.

As one of the consequences of PSM in the public sector, job satisfaction may play a critical role in bringing about better performance, such as low intention to quit a job within the public sector, especially when individuals hold an altruistic need to serve others and the community. Although P-O fit is more commonly considered as an important mediator in the PSM-job performance relationship (Bright, 2008; Kim, 2012; Gould-Williams et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018), job satisfaction may act as a possible mediating variable in the link. For instance, the findings by Vandenabeele (2009) revealed that PSM had an indirect impact on individual performance through normative and affective organizational commitment. In other words, an individual with high PSM levels is expected to experience a high level of job satisfaction, which, in turn, results in lower turnover intention. In sum, based on these arguments with regard to the significant relationships among PSM, job satisfaction and turnover intention, we propose that individuals with high levels of PSM will be satisfied with their job, and this increased job satisfaction will contribute to explain the relationship between PSM and employees’ turnover intention.

Hypothesis 2: Job satisfaction is negatively correlated with employees’ turnover intention.

Hypothesis 3: Job satisfaction mediates the negative link between employees’ PSM and their turnover intention.

Broadly speaking, organizational commitment is described as “a psychological state that characterizes the employee’s relationship with the organization” (Meyer et al., 1993). Allen and Meyer (1993) suggested that organizational commitment was an important predictor of turnover intention, because “it has implications for the decision to continue or discontinue membership in the organization.” A considerable number of studies have demonstrated that employees’ organizational commitment has a negative relationship with their intention to leave their organizations (Islam et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2015; Yousaf et al., 2015; Gatling et al., 2016; Wombacher and Felfe, 2017). For instance, Wombacher and Felfe (2017) revealed that affective organizational commitment and team commitment reduced employees’ target-specific turnover intention and, therefore, committed employees were more likely to remain in their organizations, especially if their levels of team commitment were high. Actually, when employees’ desires and expectations are satisfied, they will shape more psychological attachment toward their organizations and are less likely to change jobs (Nazir et al., 2016). In line with this view, we believe that affective and normative commitment is negatively related to employees’ turnover intention in a Chinese organizational context. In the Chinese context, empirical studies showed that employees’ turnover intention was not only related to organizational commitment (Tian, 2014; Li et al., 2018) but negatively connected with the work environment (Wang, 2015), organizational culture (Ma et al., 2015), emotional exhaustion (Li et al., 2018), or psychological contract (Tang et al., 2017). As Li et al. (2018) pointed out, only affective commitment is a significant predictor of Chinese employees’ turnover intention. However, Tian (2014) argued that all components of organizational commitment were negatively related to employees’ turnover intention. Generally speaking, employees would like to maintain a durable attachment to their organizations and to show less intention to leave their organizations when they have higher organizational commitment.

Furthermore, as “a psychological state” to a particular organization (Allen and Meyer, 1993), organizational commitment has several significant antecedents, such as career identification, value congruence, PSM, and so on. The original basis of PSM theory suggests that individuals are motivated to do good for public service for particular reasons, among which the most important is “commitment to the public interest” (Perry, 1996). In general, PSM acts as the antecedent of organizational commitment, which indicates that PSM is positively associated with organizational commitment (Taylor, 2008; Vandenabeele, 2009; Kim, 2012; Caillier, 2016; Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot, 2017). According to Kim (2012), “as the levels of PSM in public employees increase, their loyalty and emotional identification with the organization that seeks public interests will also increase.” Potipiroon and Ford (2017) supported scholars’ arguments that ethical leadership and high-intrinsic motivation mediated the positive association between PSM and public employees’ organizational commitment. Similarly, Jin et al. (2018) suggested that the effect of PSM on organizational commitment was positive and significant, which in turn led to more positive attitudes and commitment toward the employees’ work.

Yet, other studies showed that the effect of PSM on organizational commitment depended on the intermediate variables to some extent (Kim et al., 2015). Kim et al. (2015), for example, found that “when employees’ affective commitment is high in a context where their values are consistent with their organization’s goals or missions, their level of PSM will increase.” That is to say, the levels of affective commitment among public employees will reinforce their pro-social behaviors and positive work value, which leads to more motivation to serve others and the public. In addition, grounded in P-O fit perspective, many scholars indicate that the relationship between PSM and work-related outcomes (e.g., organizational commitment) was partially mediated by P-O fit (Kim, 2012; Jin et al., 2018). As such, we can expect that public employees will exhibit more commitment to their organizations when they have high levels of PSM (Kim et al., 2013), because they can obtain opportunities in the public organization to contribute to the public (Luu, 2018).

Taken together, this stream of studies has suggested that PSM contributes to increase employees’ loyalty and affective identification to their organizations and, in turn, employees will prefer to stay in their organizations because a strong desire to remain in their job demonstrated commitment to the organization. As Vandenabeele (2009) described, both normative organizational commitment and affective organizational commitment mediated the association between PSM and individual work-related outcome. Similarly, Caillier (2015) also argued that organizational commitment mediated the association between PSM and government employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., whistle-blowing attitudes) in the United States. In line with these opinions, Jin et al. (2018) also argued that organizational commitment partially mediated the relationship between PSM and individual performance (e.g., organizational citizenship, institutional service) in public higher education. Although the negative effect of organizational commitment on turnover intention has been confirmed by extensive previous research, few studies have explore the association between PSM and employees’ turnover intention by examining the mediating role of organizational commitment. According to the previous research (Wright and Pandey, 2008; Vandenabeele, 2009; Jin et al., 2018), it is possible that PSM has indirect impact on work-related attitudes and behaviors through organizational commitment. As such, it is worthwhile to validate whether organizational commitment reinforces the ability of PSM to reduce employees’ turnover intention in the public sector. To test it, we propose the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 4: Organizational commitment is negatively correlated with employees’ turnover intention.

Hypothesis 5: Organizational commitment mediates the negative link between employees’ PSM and their turnover intention.

Although it is widely acknowledged that the causal link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment is still highly disputed, the psychological contract theory suggests that job satisfaction can strongly predict organizational commitment (Pandey, 2010). For instance, employees’ with high job satisfaction may develop a strong sense of loyalty and mutual commitment soon after understanding and accepting organizational goals and values (Bufquin et al., 2017; Chordiya et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017). Thus, it seems more plausible that the organizational commitment of public employees can be influenced at least in part by the levels of their job satisfaction. That is, public employees with high levels of satisfaction with their jobs will more likely become committed to their work and organizations. According to psychological contract theory, when employees are satisfied with their pay, work autonomy, career training, and career development, they will become more committed to the organization, which in turn brings about positive performance behavior.

As mentioned above, a large body of research has confirmed that employees’ turnover intention can be significantly predicted by both job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Karatepe and Kilic, 2007; Kang et al., 2014; Mathieu et al., 2016; Wombacher and Felfe, 2017). For example, according to Vandenabeele (2009), job satisfaction and organizational commitment by state civil servants acted as mediators in the PSM–performance relationship. These results were further supported by Jin et al. (2018), who argued that P-O fit and organizational commitment mediated the link between PSM and organizational citizenship behavior. Furthermore, some empirical studies proposed structural turnover models that incorporated both job satisfaction and organizational commitment in a single model (Mathieu et al., 2016; Redondo et al., 2019). Therefore, based on the aforementioned discussions and hypotheses, we expect that job satisfaction and organizational commitment will play a chain-mediating role between PSM and turnover intention. Namely, PSM will help increase employees’ levels of job satisfaction first, which, in turn, has a positive effect on employees’ loyalty and organizational commitment, and then the positive work-related attitudes can effectively decrease employees’ intention to quit their jobs. Therefore, it leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6: Job satisfaction and organizational commitment mediates the association between PSM and employees’ turnover intention sequentially.

Data for this study were collected from MPA (master of public administration) students of two prestigious universities in Yunnan province, China, from August to September in 2019. Before the survey, we contacted the director of MPA Education Center of each university to obtain the total number of MPA students. With the help of staff of MPA Education Centers, we successively distributed survey questionnaires to 600 MPA students who are full-time public employees in various government departments. Each participant was asked to fill out the self-reported questionnaire voluntarily and anonymously. After deleting 13 questionnaires with missing data, we obtained a diverse sample of 587 participants who were full-time civil servants employed by local governments at all levels across Yunnan province. Of the participants, 306 (52.1%) were men and 281 (47.9%) were women; 42.2% of the participants were 30 years old or under and 13.1% were over 50 years old. For educational background, 74.8% held at least a bachelor’s degree, while 25.2% had an associate degree or less. In terms of length of employment, 31.2% worked for under 5 years, 23.5% worked for 6–10 years, 8.7% worked for 11–15 years, 7% worked for 16–20 years, and 29.6% worked for more than 21 years.

Public service motivation was measured with a translated version of five items developed by Perry (1996), which was widely used in various cultural contexts (Christensen and Wright, 2011; Qi and Wang, 2018). This 5-item scale was used to capture four aspects of individual PSM which included self-sacrifice (two items), commitment to public interests (one item), compassion (one item), and social justice (one item). A sample item was “Making a difference in society means more to me than personal achievements.” Each item is measured on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.835.

Job satisfaction was evaluated with Boateng and Hsieh (2019) scale, including 4 items. Sample items included such statements as “No matter what, I will not leave my current job” and “Overall, I am satisfied with my current job.” Participants answered items on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.839.

Organizational commitment was measured by Meyer et al. (1993) scale. We adopted four items to evaluate public employees’ organizational commitment. Sample items included “I feel emotionally attached to my organization.” All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.884.

Turnover intention was assessed using the 4-item scale validated by Kim et al. (1996). Sample items included “I intend to leave my organization” and “I intend to stay in my present organization as long as possible.” Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.858.

We conducted data analyses using SPSS and AMOS version 24. The missing values were handled by using the full information maximum likelihood method before our analysis. According to the recommendation of Anderson and Gerbing (1988), a 2-step analytical strategy was used to conduct data analysis. First, to determine whether all study variables were distinguishable in the present study, we tested and compared the model fit of four models using confirmatory factory analysis (CFA). We assessed the hypothesized model compared with alternative models through confirmatory factory analysis. In addition, to avoid a risk of common method bias from as self-administered survey, the common method bias was tested by using Harman’s single-factor analysis.

Second, to test the hypotheses, structural equation modeling in AMOS 24 was performed to verify whether the relationship between PSM and turnover intention was mediated by job satisfaction or organizational commitment. Before testing the mediating effects, we first tested the direct effect of PSM on employee’ turnover intention without inclusion of the mediators in a structural equation model. Then, we used the biased-corrected bootstrapping method of the mediation test to analyze the indirect effects and mediated effects. As suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2008), the mediating effects are statistically significant when zero does not lie in the confidence interval range.

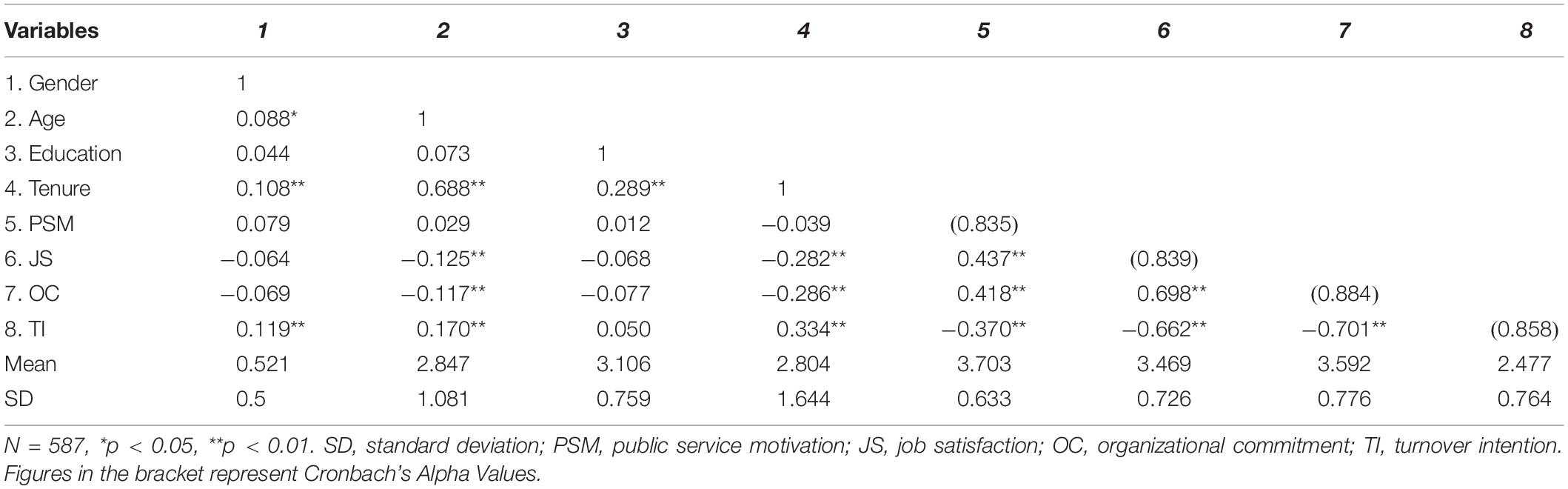

The descriptive, correlations, and reliability for all study variables were shown in Table 1. According to the correlation matrix, PSM was negatively correlated with turnover intention (r = −0.370, p < 0.01), thus Hypothesis 1 was supported. In addition, PSM was positively related to job satisfaction (r = 0.437, p < 0.01) and also to organizational commitment (r = 0.418, p < 0.01), thus supporting Hypotheses 2 and 5. Both organizational commitment (r = −0.701, p < 0.01) and job satisfaction (r = −0.662, p < 0.01) were all negatively related to turnover intention, which supported Hypotheses 6 and 3. In addition, the construct coefficient alphas were above the minimum threshold value of 0.70, which ranged from 0.835 to 0.858, and suggested high reliability of the study scale.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, correlations, and Cronbach’s Alpha Values among the study variables.

The goodness fit of the four-factor model was examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The model fit was assessed using three fit indices, including CFI (comparative fit index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis index), and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation). We proposed five alternative model conceptualizations (Table 2). Compared with the five alternative models, the four-factor model resulted in a more acceptable fit [χ2 (113) = 281.432, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.963, and RMSEA = 0.05]. For example, the fit indices in the two-factor model demonstrated that the model did not provide an adequate fit [χ2 (118) = 1433.392, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.753, TLI = 0.727, and RMSEA = 0.138] as well as the hypothesized four-factor model. The one-factor model provided a less adequate fit [χ2 (119) = 1580.686, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.736, TLI = 0.699, and RMSEA = 0.145]. Thus, the hypothesized four-factor model exhibited excellent construct distinctiveness in the present study.

Because the self-reported data was mainly collected from a single source, there was a risk of common method bias, such as social desirability and consistency motif (Podaskoff et al., 2003). To minimize the potential for common method bias, we adopted measures from previous studies and conducted a pre-test. Moreover, all respondents were informed to finish the questionnaire anonymously, which reduced the possibility of social desirability. To examine whether common method variance (CMV) bias was a concern, we assess the extent of common method bias in the present study by using a Harman’s single-factor test. The result indicated that 33.98% of the variance was explained by the first factor, which suggested the common method variance bias was not a problem in the present study. Furthermore, our results indicated a very poor fit in the one-factor model [χ2 (119) = 1580.686, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.736, TLI = 0.699, and RMSEA = 0.145]. Therefore, it also indicated that the common method bias was an unlikely interpretation of our findings.

To test the study hypotheses, the fit of the data was tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). First, we tested the direct effect of PSM on turnover intention without inclusion of the mediators in the path structural equation model. PSM had a direct, negative effect on turnover intention (PSM→TI; p < 0.001, standardized estimate = 0.407), which supported hypothesis 1. Also, 54% of the variance in turnover intention (R2 = 0.54) was explained by PSM. This finding was consistent with the previous studies of samples from street-level bureaucrats in South Korea (Shim et al., 2017) and high school employees in the United States (Choi and Chun, 2018).

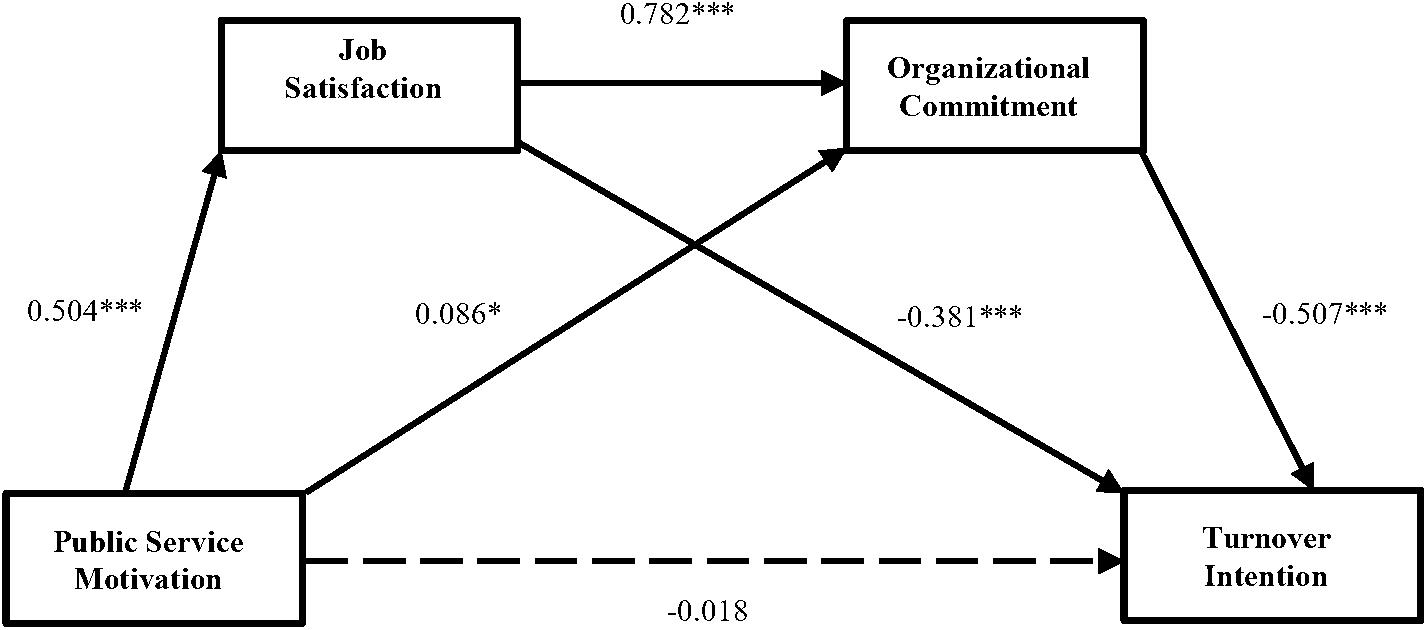

Then, we constructed a proposed model (Figure 1), which included the mediators. The results of the hypothesized model were shown in Table 3 and Figure 2 which provided standardized parameters and R2 coefficients. The results in Figure 2 showed that the fit indices for the hypothesized model were excellent [χ2 (111) = 246.104, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.970, and RMSEA = 0.046], because CFI and TLI all are above 0.9, and RMSEA was at or below 0.06. As displayed, PSM had a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction (PSM→JS; p < 0.001, standardized estimate = 0.504) and organizational commitment (PSM→JS; p < 0.05, standardized estimate = 0.086). Furthermore, the direct effects of job satisfaction (JS→TI; p < 0.001, standardized estimate = −0.381) and organizational commitment (OC→TI; p < 0.001, standardized estimate = −0.507) on turnover intention were all negative and significant, which supported Hypotheses 2 and 4. In addition, job satisfaction positively affected organizational commitment (JS→OC; p < 0.001, standardized estimate = 0.782). However, PSM had no direct effect on employees’ turnover intention (standardized estimate = −0.018, p > 0.05) when the mediators were included in the hypothesized model.

Figure 2. The mediation analysis of job attitudes between PSM and turnover intention (dotted lines represent relationships which are not significant in the full model), *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

To detect the indirect effects, a bootstrapping method was performed to test the indirect effects and mediating effects in the path structural equation model. As can be seen from Table 3 and Figure 2, the indirect impact of PSM on turnover intention through job satisfaction (PS→JS→TI) was statistically significant (standardized estimate = −0.192, CI = −0.970, −0.314), since the confidence interval range did not contain zero. Thus, job satisfaction fully mediated the negative relationship between PSM and turnover intention, which supported Hypothesis 3. Likewise, the indirect effect of PSM on turnover intention through organizational commitment (PSM→OC→TI) was statistically significant (standardized estimate = −0.043, CI = −0.303, −0.010), which indicated the mediating effect of organizational commitment in the association between PSM and employees’ intention to quit their jobs. Accordingly, Hypothesis 5 was supported. The bootstrapping test also presented an interesting finding that the indirect impact of job satisfaction on turnover intention through organizational commitment (JS→OC→TI) was significant (standardized estimate = −0.397, CI = −0.552, −0.242). This result indicated that the association between employees’ job satisfaction and their turnover intention was partially mediated by organizational commitment.

Finally, we tested whether employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment will sequentially mediate the path between PSM and turnover intention. As expected, the indirect effects of PSM on turnover intention through job satisfaction and organizational commitment (PSM→JS→OC→TI) was also statistically significant (standardized estimate = −0.120, CI = −1.119, −0.442), which confirmed that PSM negatively affected turnover intention through job satisfaction and organizational commitment in serial. Hence, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

In the present study, we examined how PSM influenced employees’ turnover intention in the public sector. The present study aimed to analyze the associations among PSM and the work-related variables that included job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention. We also tested how employees’ job attitudes mediated the link between PSM and employees’ turnover intention.

First, employees’ with high PSM levels were less likely to leave their job within the public sector. In fact, the high-PSM employees were more likely to work in the public sector. A possible reason why public employees with high PSM levels can markedly lower the levels of turnover intention is because public employees with high PSM levels prefer to do these jobs that help others, serve the community of people and correct social inequity. Previous research has shown that public employee with high PSM levels place more importance on their jobs and showed more pro-social behaviors (Vandenabeele, 2008; Choi and Chun, 2018). Our results supported previous findings that public employees’ PSM had a direct, negative effect on their turnover intention (Perry and Wise, 1990; Shim et al., 2017).

However, the results suggested that employees’ PSM could not directly affect their turnover intention when job satisfaction and organizational commitment were taken into account. Consequently, our results supported a similar finding proposed by Bright (2008) that PSM had no direct, significant effect on employees’ turnover intention after mediators (e.g., P-O fit) were considered. Furthermore, our results were also similar to those suggested by Vandenabeele (2009), where job satisfaction, normative organizational commitment, and affective organizational commitment played a partial or full mediating role in the links between PSM and individual performance. Although some scholars stressed the significant direct effects of PSM on job attitudes, such as job satisfaction, and work-related behaviors (Kim, 2012; Jin et al., 2018), the indirect effect of PSM on turnover intention remains mixed when mediators are taken into account. The inconsistent association between PSM and turnover intention may depend on cultural context, which might be related to individuals’ PSM. More specifically, employees in collectivistic countries (e.g., China and Japan) would be more inclined to over-report their levels of PSM (Kim and Kim, 2016), because they are likely to hide their true intention to leave their job due to the profound influence of Confucianism.

Second, our study confirmed that the association between PSM and turnover intention was fully mediated by both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Wright and Pandey (2008) demonstrated that the direct influence of PSM on work-related attitudes was mixed, so mediating variables were needed to explain this. As the results revealed, the effect of employees’ PSM on turnover intention was fully mediated by job satisfaction. In other words, employees with high PSM level experienced high level of job satisfaction, which led them to lower their intention to leave the public sector. Such findings are consistent with some previous results, which found that the positive PSM-job satisfaction association decreased employees’ intention to leave the public sector (Choi and Chun, 2018; Kjeldsen and Hansen, 2018). Therefore, jobs in the public sector may bring more satisfaction and ultimately lower their turnover intention for those employees with high levels of PSM. Likewise, organizational commitment played a fully mediating role between employees’ PSM and their turnover intention. Previous research revealed that “PSM had a direct, positive effect on organizational commitment” (Kim, 2012; Austen and Zacny, 2015; Caillier, 2016), thus, employees with high PSM levels showed strong commitment and loyalty to their organizations.

Third, one interesting finding was that organizational commitment partially mediated the negative association between employees’ job satisfaction and their turnover intention. Our result showed that job satisfaction indirectly affected employees’ turnover intention through organizational commitment. Actually, some previous studies have shown that job satisfaction significantly predicts organizational commitment (Bufquin et al., 2017); thus, we concluded that job satisfaction showed an indirect impact on turnover intention through its influence on organizational commitment. Our results suggested that employees with high levels of job satisfaction showed greater commitment than others to their public organizations, and they chose not to leave their current job within the public sector.

Lastly, our results showed that job satisfaction and organizational commitment played multiple mediating effects in a negative association between PSM and employees’ intention to quit. In prior studies, work-related attitudes and behaviors are regarded as independent intervening variables in the link between PSM and job performance (Kim, 2012; Jin et al., 2018), but few studies have incorporated job satisfaction and organizational commitment into a single turnover model. Therefore, our study provided more comprehensive analysis of the process of the direct and indirect effects of PSM on public employees’ turnover intention, and it offered further evidence for turnover model including job satisfaction and organizational commitment, which supported the findings of Vandenabeele (2008). More specifically, individuals with high PSM level tend to be more satisfied with their job, work environment, and organizations. Then, this type of job satisfaction gradually increases employees’ commitment to their organizations, thereby lowering the intention to change jobs within the public sector.

Our study contributes to the previous literature concerning the mixed link between PSM and turnover intention. First, our study contributes to understanding the disputed association between PSM and turnover intention by extending the existing PSM literature in the Chinese context. Although previous studies have revealed an inconsistent relationship between PSM and turnover intention (Bright, 2008; Kim, 2012; Shim et al., 2017), there is no denying that individual levels of PSM differ across nations and cultures that are viewed as an antecedent of PSM (Ritz and Brewer, 2013; Anderfuhren-Biget et al., 2014; Kim, 2017). Most previous studies verified the causal effect of PSM on turnover intention with samples from Western countries, but few studies were conducted in Asian countries with a Confucian culture, especially in China where such studies are virtually non-existent. Indeed, recent findings have confirmed the significant effects of national culture on individual levels of PSM in collectivistic countries (Ritz and Brewer, 2013; Kim, 2017). As a result of the influence of Confucian culture, Chinese public employees may tend to over-evaluate their levels of PSM, but they may hide their true intention to quit a job to the extent possible. As such, our study not only confirmed whether the effect of PSM on turnover intention was significant in a Chinese context, but it also tested the generalizability of Perry’s PSM theory. Given that cultural and institutional context play an important role in shaping individual levels of PSM, the reason for the complex links between PSM and turnover intention or other work-related behaviors might be interpreted from a cross-cultural perspective. Consequently, in addition to examining the association between PSM and individual work-related behavior, scholars might explore further how the overall relationship found in our study varies across cultural and institutional contexts. In a word, our study broadens previous research on the mixed association between PSM and turnover intention in a cultural context. The fact that our study took into consideration the cultural context in explaining the effects of PSM on work-related behaviors also offers a more comprehensive insight for understanding PSM theory.

Second, our study integrated job satisfaction and organizational commitment into a single turnover model, which resulted in a better understanding of the relation between PSM and turnover intention. To our knowledge, only three empirical studies in the literature have proposed a turnover model that incorporated both job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Williams and Hazer, 1986; Mathieu et al., 2016; Redondo et al., 2019). As mentioned above, most scholars have explained the causality between PSM and work-related performance using P-O fit theory (Gould-Williams et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018), but few studies have attempted to include both job satisfaction and organizational commitment in a single turnover model. Perry et al. (2010) pointed out that scholars should pay careful attention to the roles of intervening variables with regard to the complicated PSM-performance relationships (Perry et al., 2010). In addition, some scholars have pointed out that PSM acts as a generic antecedent of job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Judge et al., 2001). Thus, we argued in this study, however, that the mediating role of public employees’ job attitudes in a turnover model should not be ignored. By doing so, our study theoretically broadens the mechanism through which PSM affects public employees’ turnover intention and might shed more light on the theoretical approaches to the disputed link between PSM and work-related behaviors.

Beyond the theoretical contribution to PSM theory, the present study offers significant insights for public organizations. First, since job applicants with high-PSM have a preference for the jobs within the public sector and are less likely to quit their job (Carpenter et al., 2012; Choi and Chun, 2018), our study indicates that job applicants with high PSM levels should be valued during the recruitment and selection procedures. To be more specific, the PSM index may be “used as one of the criteria in the employee selection process” (Lee and Choi, 2016) because it is urgent for public organizations to attract more individuals with the spirit of public concern and community values.

More importantly, the policy makers in the public organizations should pay close attention to the cultivation and promotion of employees’ levels of PSM through formal training and occupational socialization. Lee and Choi (2016) argued that PSM could be cultivated and increased through a variety of devices, therefore, the policy makers in the public organizations could adopt some effective ways to imbue public employees with underlying organizational values (Kim, 2012). In particular, in view of various cultural backgrounds of new public employees, a kind of effective formal training might cause them to appreciate organizational values and expectations that embody public interests and public service values (Paarlberg et al., 2008).

Furthermore, our findings also suggest that job satisfaction significantly predicts public employees’ turnover intention and, thus, it might provide some reasons for policy makers in public organizations to increase public employees’ salary and improve their treatment on the job. Actually, our results showed that job satisfaction was positively associated with employees’ organizational commitment and, in turn, led to employees’ intention to stay in the public sector. Therefore, one important revelation is that a kind of diversified incentive mechanism should be established in the public organization to enhance public employee’s job satisfaction. These incentive mechanisms could include not only material excitation means, but some non-material motivating measures, such as job promotion, career development, skills training, and job autonomy (Ni and Wu, 2013; Tang et al., 2017).

As with any research, our study also has some limitations that should be taken into account in the future research. First, our study relied on a cross-sectional design that cannot allow us to make causal statements with certainty. Some recent studies have explored how employees’ turnover intention changes in accordance with affective commitment and job satisfaction based on longitudinal data (Chen et al., 2011; Vandenberghe et al., 2011). As such, future research should be based on longitudinal data that can further validate the causality between PSM and turnover intention. In particular, future studies should focus on how the trajectories of individual changes in PSM affect employees’ turnover intention and other work-related behaviors.

Second, we adopted a shortened version of Perry’s PSM scale, so the results of our study should be interpreted with caution. Although previous studies have widely verified the reliability of a shortened version of Perry’s PSM scale (Pandey et al., 2008; Wright and Pandey, 2008; Coursey et al., 2012), it would be worthwhile to develop an original PSM measure based on the Chinese context in future studies. As Liu (2009) argued, one of the PSM subdimensions—compassion dimension—could not be supported in the Chinese context. Future studies, therefore, are needed to propose and to validate a PSM scale consistent with Chinese cultural and institutional contexts.

Third, the data in the present study were collected from a single source, which means there was a risk of common method variance. In particular, it was possible that public employees answered questions in a similar way due to the influence of “official-oriented” thought and social desirability. In addition, because our data were derived from a sample collected from public employees in a single Chinese area, the sample of this survey does not completely match the characteristics of public employees’ nationwide. Therefore, although the common method bias is not a concern in our study, it needed to collected data from multiple sources in order to reduce potential common method bias.

Finally, given that PSM might change across cultures (Kim, 2017; Lee et al., 2020), it must be cautious to generalize the findings from one region (e.g., Yunnan province) to other regions of China. It is quite probable that individuals’ PSM levels might vary with region because each region of China has diversified ethnic culture. It may be worthwhile to explore whether our finding can be generalized in other regions of China with different ethnic culture and institution context. Thus, future research should verify the generalization of our findings with empirical data collected from different regions.

Our study aimed to explore the mediating role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment to explain the association between public employees’ PSM and their turnover intention. Although public management scholars have confirmed the critical role of PSM in shaping individual work-related behavior (Shim et al., 2017; Choi and Chun, 2018; Jin et al., 2018), the results remains mixed regarding the relationship between PSM and turnover intention. This study provides additional insight into the link between PSM and turnover intention by proposing a chain moderating role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Our findings revealed that public employees’ PSM had no direct effect on their turnover intention when job satisfaction and organizational commitment were considered simultaneously. In addition, the present study stressed the importance of exploring the mediating role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment to predict the effects of PSM on public employees’ turnover intention. Our findings also indicated that organizational commitment played a mediating role in the association between public employees’ job satisfaction and their turnover intention. Furthermore, PSM indirectly affected employees’ turnover intention through its influence on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the causal chain.

Although our findings are not completely consistent with some previous studies (Vandenabeele, 2009; Kim, 2012; Jin et al., 2018), it is important to recognize that the causality of the PSM-turnover intention link might depend on various mediators and different cultural and institutional contexts. Actually, without considering the influence of particular cultural and institutional backgrounds, it is impossible to understand the inconsistent results of the causal link between PSM and turnover intention. In particular, PSM and job satisfaction within the public sector should be regarded as significant psychological resources for the enhancement of employees’ organizational commitment and reduction of their turnover intention. As such, we expect that this type of research will not only help test the generalization of PSM theory by undertaking cross-cultural studies, but it will underscore the need for public sector organizations to attach importance to public employees’ PSM and job satisfaction.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

This study was conducted with oral informed consent from all participants. All participants were informed to complete the survey confidentially and anonymously. Based on this assumption, ethical review and approval was not required for this kind of study in China.

YL and QW collected the data and performed the data analyses. K-PG drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of manuscript and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 12CSH056.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01289/full#supplementary-material

Allen, N. J., and Meyer, J. P. (1993). Organizational commitment: evidence of career stage effects? J. Bus. Res. 26, 49–61. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(93)90042-N

Alonso, P., and Lewis, G. B. (2001). Public service motivation and job performance: evidence from the federal sector. Am. Rev. Public Admin. 31, 363–380. doi: 10.1177/02750740122064992

Anderfuhren-Biget, S., Varone, F., and Giauque, D. (2014). Policy environment and public service motivation. Public Admin. 92, 807–825. doi: 10.1111/padm.12026

Andersen, L. B., and Kjeldsen, A. M. (2013). Public service motivation, user orientation and job satisfaction: a question of employment sector? Int. Public Manag. J. 12, 252–274. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2013.817253

Andersen, L. B., and Søren, L. S. (2012). Does public service motivation affect the behavior of professionals? Int. J. Publ. Admin. 35, 19–29. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2011.635277

Anderson, J. C., and Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice- A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103, 411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Austen, A., and Zacny, B. (2015). The role of public service motivation and organizational culture for organizational commitment. Management 19, 21–34. doi: 10.1515/manment-2015-0011

Belle, N. (2013). Experimental evidence on the relationship between public service motivation and job performance. Public Admin. Rev. 73, 143–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02621.x

Boateng, F. D., and Hsieh, M. L. (2019). Explaining job satisfaction and commitment among prison officers: the role of organizational justice. Prison J. 99, 172–193. doi: 10.1177/0032885519825491

Bozeman, B., and Su, X. (2015). Public service motivation concepts and theory: a critique. Public Admin. Rev. 75, 700–710. doi: 10.1111/puar.12248

Bright, L. (2007). Does person-organization fit mediate the relationship between public service motivation and the job performance of public employees? Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 27, 361–379. doi: 10.1177/0734371X07307149

Bright, L. (2008). Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? Am. Rev. Public Admin. 38, 149–146. doi: 10.1177/0275074008317248

Bufquin, D., DiPietro, R., Orlowski, M., and Partlow, C. (2017). The influence of restaurant co-workers’ perceived warmth and competence on employees’ turnover intentions: the mediating role of job attitudes. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 60, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.09.008

Caillier, J. G. (2015). Transformational leadership and whistle-blowing attitudes: Is this relationship mediated by organizational commitment and public service motivation? Amer. Rev. Public Admin. 45, 458–475. doi: 10.1177/0275074013515299

Caillier, J. G. (2016). Does public service motivation mediate the relationship between goal clarity and both organizational commitment and extra-role behaviors? Public Manag. Rev. 18, 300–318. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2014.984625

Caillier, J. G. (2020). Testing the influence of autocratic leadership, democratic leadership, and public service motivation on citizen ratings of an agency head’s performance. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 190, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2020.1730919

Carpenter, J., Doverspike, D., and Miguel, R. F. (2012). Public service motivation as a predictor of attraction to the public sector. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 509–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.08.004

Chen, G., Ployhart, R. E., Thomas, H. C., Anserson, N., and Bliese, P. D. (2011). The power of momentum: a new model of dynamic relationships between job satisfaction change and turnover intentions. Acad. Manag. J. 54, 159–181. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2011.59215089

Choi, H., and Chiu, W. (2017). Influence of the perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and career commitment on football referees’ turnover intention. Int. J. Phy. Educ. Sport 17, 955–959. doi: 10.7752/jpes.2017.s3146

Choi, Y. J., and Chun, I. H. (2018). Effects of public service motivation on turnover and job satisfaction in the US teacher labor market. Int. J. Publ. Admin. 41, 172–180. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2016.1256306

Chordiya, R., Sabharwal, M., and Goodman, D. (2017). Affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction: a cross-national comparative study. Public Adm. 95, 178–195. doi: 10.1111/padm.12306

Christensen, R. K., and Wright, B. E. (2011). The effects of public service motivation on job choice decisions: disentangling the contributions of person-organization fit and person-job fit. J. Publ. Admin. Res. Theory 21, 723–743. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muq085

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., and Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: a quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 64, 89–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

Coursey, D., Pandery, S. K., and Yang, K. F. (2012). Public service motivation (PSM) and support for citizen participation: a test of Perry and Vandenabeele’s reformulation of PSM theory. Public Adm. Rev. 72, 572–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02581.x

Gatling, A., Kang, H. J. A., and Kim, J. S. (2016). The effects of authentic leadership and organizational commitment on turnover intention. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 37, 181–199. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-05-2014-0090

Georgellis, Y., and Tabvuma, V. (2010). Does public service motivation adapt? Kyklos 63, 176–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2010.00468.x

Gould-Williams, J. S., Mostafa, A. M. S., and Bottomley, P. (2015). Public service motivation and employee outcomes in the Egyptian public sector: testing the mediating effect of person-organization fit. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory 25, 597–622. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mut053

Hondeghem, A., and Perry, J. L. (2009). EGPA symposium on public service motivation and performance: introduction. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 75, 5–9. doi: 10.1177/0020852308099502

Houston, D. J. (2011). Implications of occupational locus and focus for public service motivation: attitudes toward work motives across nations. Public Adm. Rev. 71, 761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02415.x

Huang, S. L., Chen, Z., Liu, H. F., and Zhou, L. Y. (2017). Job satisfaction and turnover intention in China: the moderating effects of job alternatives and policy support. Chin. Manag. Stud. 11, 955–959. doi: 10.1108/CMS-12-2016-0263

Islam, T., Ahmed, I., and Ahmad, U. N. B. (2015). The influence of organizational learning culture and perceived organizational support on employees’ affective commitment and turnover intention. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 6, 417–431. doi: 10.1108/NBRI-01-2015-0002

Jin, M. H., McDonald, B., and Park, J. (2018). Does public service motivation matter in public higher education? Testing the theories of person-organization fit and organizational commitment through a serial multiple mediation model. Am. Rev. Public Admin. 48, 82–97. doi: 10.1177/0275074016652243

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., and Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 127, 376–407. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.127.3.376

Kang, H. J., Gatling, A., and Kim, J. (2014). The impact of supervisory support on organizational commitment, career satisfaction, and turnover intention for hospitality frontline employees. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 14, 68–89. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2014.904176

Karatepe, O. M., and Kilic, H. (2007). Relationships of supervisor support and conflicts in the work–family interface with the selected job outcomes of frontline employees. Tour. Manag. 28, 238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.12.019

Khan, A. H., and Aleem, M. (2014). Impact of job satisfaction on employee performance: an empirical study of autonomous medical institutions of Pakistan. Int. J. Manag. Innov. 7, 122–132. doi: 10.14254/2071-8330.2014/7-1/11

Kim, S. (2012). Does person-organization fit matter in the public-sector? Testing the mediating effect of person-organization fit in the relationship between public service motivation and work attitudes. Public Admin. Rev. 72, 830–840. doi: 10.111/J.1540-6210.2O12.O2572.X

Kim, S. (2017). National culture and public service motivation: investigating the relationship using Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 83, 23–40. doi: 10.1177/0020852315596214

Kim, S. E., and Lee, J. W. (2007). Is mission attachment an effective management tool for employee retention? An empirical analysis of a nonprofit human services agency. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 27, 227–248. doi: 10.1177/0734371X06295791

Kim, S. H., and Kim, S. (2016). National culture and social desirability bias in measuring public service motivation. Admin. Soc. 48, 444–476. doi: 10.1177/0095399713498749

Kim, S. W., Price, J. L., Mueller, C. W., and Watson, T. W. (1996). The determinants of career intent among physicians at a US Air Force hospital. Hum. Relat. 49, 947–975. doi: 10.1177/001872679604900704

Kim, S. W., Vandenabeele, W., Wright, B. E., Andersen, L. B., Cerase, F. P., Christensen, R. K., et al. (2013). Investigating the structure and meaning of public service motivation across populations: developing an international instrument and addressing issues of measurement invariance. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory 23, 79–102. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus027

Kim, T., Henderson, A. C., and Eom, T. H. (2015). At the front line: examining the effects of perceived job significance, employee commitment, and job involvement on public service motivation. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 8, 713–733. doi: 10.1177/0020852314558028

Kim, Y. I., Geun, H. G., Choi, S., and Lee, Y. S. (2017). The impact of organizational commitment and nursing organizational culture on job satisfaction in Korean American registered nurses. J. Transcult. Nurs. 28, 590–597. doi: 10.1177/1043659616666326

Kjeldsen, A. M., and Andersen, L. B. (2013). How pro-social motivation affects job satisfaction: an international analysis of countries with different welfare state regimes. Scand. Polit. Stud. 36, 153–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2012.00301.x

Kjeldsen, A. M., and Hansen, J. R. (2018). Sector differences in the public service motivation-job satisfaction relationship: exploring the role of organizational characteristics. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 38, 24–48. doi: 10.1177/0734371X16631605

Lambert, E. G., Griffin, M. L., Hogan, N. L., and Kelley, T. (2015). The ties that bind: organizational commitment and its effect on correctional orientation, absenteeism, and turnover intent. Prison J. 95, 135–156. doi: 10.1177/0032885514563293

Lee, G., and Choi, D. L. (2016). Does public service motivation influence the college students’ intention to work in the public sector? Evidence from Korea. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 36, 145–163. doi: 10.1177/0734371X13511974

Lee, H. J., Oh, H. G., and Park, S. M. (2020). Do trust and culture matter for public service motivation development? Evidence from public sector employees in Korea. Public Pers. Manage. 49, 290–323. doi: 10.1177/0091026019869738

Leisink, P., and Steijn, B. (2008). “Recruitment, attraction, and selection,” in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service, eds J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 118–135.

Levitats, Z., and Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2017). Yours emotionally: how emotional intelligence infuses public service motivation and affects the job outcomes of public personnel. Public Admin. 95, 759–775. doi: 10.1111/padm.12342

Li, X. Y., Yang, B., Jiang, L. P., Zuo, W. C., and Zhang, B. F. (2018). Research on the relationship between early career employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intention with organizational commitment as mediated variable (in Chinese). Chin. Soft Sci. 15, 163–170.

Liu, B. C. (2009). Evidence of public service motivation of social worker in China. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 75, 349–366. doi: 10.1177/0020852309104180

Liu, B. C., Hui, C., Hu, J., Yang, W. S., and Yu, X. L. (2011). How well can public service motivation connect with occupational intention? Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 77, 191–211. doi: 10.1177/0020852310390287

Liu, B. C., Tang, T. L. P., and Yang, K. F. (2015). When does public service motivation fuel the job satisfaction fire? The joint moderation of person–organization fit and needs–supplies fit. Public Manag. Rev. 17, 876–900. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.867068

Locke, E. A. (1976). “The nature and causes of job satisfaction,” in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, ed. M. D. Dunnette (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally), 1297–1343.

Luu, T. (2018). Discretionary HR practices and proactive work behavior: the mediation role of affective commitment and the moderation roles of PSM and abusive supervision. Public Manag. Rev. 20, 789–823. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1335342

Ma, S., Wang, C. X., Hu, J., and Zhang, X. C. (2015). Work stress and job satisfaction, turnover intention of local taxation bureau township civil servants: the moderating effect of psychological capital (in Chinese). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 23, 326–335.

Mathieu, C., Fabi, B., Lacoursiere, R., and Raymond, L. (2016). The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. J. Manag. Organ. 22, 113–129. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2015.25

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organization and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Miao, Q., Eva, N., Newman, A., and Schwarz, G. (2019). Public service motivation and performance: the role of organizational identification. Public Money Manage. 39, 77–85. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2018.1556004

Moynihan, D. P., and Landuyt, N. (2008). Explaining turnover intention in state government: examining the roles of gender, life cycle, and loyalty. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 28, 120–143. doi: 10.1177/0734371X08315771

Moynihan, D. P., and Pandey, S. K. (2007). The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Admin. Rev. 67, 40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00695.x

Nazir, S., Shafi, A., Qun, W., Nazir, N., and Tran, Q. D. (2016). Influence of organizational rewards on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Empl. Relat. 38, 596–619. doi: 10.1108/ER-12-2014-0150

Ni, C. Q., and Wu, B. (2013). Exploring the path of civil servants’ pluralistic incentive: taking Zeng Guofan’s motivation as an example (in Chinese). Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 21, 136–141.

O’Leary, C. (2019). Public service motivation: a rationalist critique. Public Person. Manag. 48, 82–96. doi: 10.1177/0091026018791962

Paarlberg, L. E., Perry, J. L., and Hondeghem, A. (2008). “From theory to practice: strategies for applying public service motivation,” in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service, eds J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 268–293.

Pandey, S. K. (2010). Cutback management and the paradox of publicness. Public Admin. Rev. 70, 564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02177.x

Pandey, S. K., Wright, B. E., and Moynihan, D. P. (2008). Public service motivation and interpersonal citizenship behavior in public organizations: testing a preliminary model. Int. Public Manag. J. 11, 89–108. doi: 10.1080/10967490801887947

Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: an assessment of construct reliability and validity. J. Publ. Admin. Res. Theory 6, 5–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024303

Perry, J. L., and Hondeghem, A. (2008). Building theory and empirical evidence about public service motivation. Int. Public Manag. J. 11, 3–12.

Perry, J. L., Hondeghem, A., and Wise, L. R. (2010). Revisiting the motivational bases of public service: twenty years of research and an agenda for the Future. Public Admin. Rev. 70, 681–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02196.x

Perry, J. L., and Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public Admin. Rev. 50, 367–373. doi: 10.2307/976618

Podaskoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Potipiroon, W., and Ford, M. T. (2017). Does public service motivation always lead to organizational commitment? Examining the moderating roles of intrinsic motivation and ethical leadership. Public Person. Manag. 46, 211–238. doi: 10.1177/0091026017717241

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Qi, F. H., and Wang, W. J. (2018). Employee involvement, public service motivation, and perceived organizational performance: testing a new model. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 84, 746–764. doi: 10.1177/0020852316662531

Quratulain, S., and Khan, A. K. (2015). Red tape, resigned satisfaction, public service motivation, and negative employee attitudes and behaviors: testing a model of moderated mediation. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 35, 307–332. doi: 10.1177/0734371X13511646

Rainey, H. G., and Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory 9, 1–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024401

Redondo, R., Sparrow, P., and Hernández-Lechuga, G. (2019). The effect of protean careers on talent retention: examining the relationship between protean career orientation, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and intention to quit for talented workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 19, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1579247

Ritz, A., and Brewer, G. A. (2013). Does societal culture affect public service motivation? Evidence of sub-national differences in Switzerland. Int. Public Manag. J. 16, 224–251. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2013.817249

Ritz, A., Schott, C., Nitzl, C., and Alfes, K. (2020). Public service motivation and prosocial motivation: two sides of the same coin? Public Manag. Rev. 40, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1740305

Shim, D. C., Park, H. H., and Eom, T. H. (2017). Street-level bureaucrats’ turnover intention: Does public service motivation matter? Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 83, 563–582. doi: 10.1177/0020852315582137

Steijn, B. (2008). Person-environment fit and public service motivation. Int. Public Manag. J. 11, 13–27. doi: 10.1080/10967490801887863

Tang, Y. X., Liu, B. C., and Wang, Y. X. (2017). The influence of psychological contract difference on the turnover intention of civil servants: based on the guidance of motivation and contribution (in Chinese). J. Public Manag. 14, 27–43.

Taylor, J. (2008). Organizational influences, public service motivation and work outcomes: an Australian study. Int. Public Manag. J. 11, 67–88. doi: 10.1080/10967490801887921

Taylor, J. (2014). Public service motivation, relational job design, and job satisfaction in local government. Public Admin. 92, 902–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02108.x

Tian, H. (2014). Organizational justice, organizational commitment and turnover intention (in Chinese). Learn. Explor. 2, 114–118.

van Loon, N., Kjeldsen, A. M., Lotte Bøgh Andersen, L. B., Vandenabeele, W., and Leisink, P. (2018). Only when the societal impact potential is high? a panel study of the relationship between public service motivation and perceived performance. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 38, 139–166. doi: 10.1177/0734371X16639111

van Loon, N. M. (2017). Does context matter for the type of performance-related behavior of public service motivated employees? Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 2017, 405–429. doi: 10.1177/0734371X15591036

Vandenabeele, W. (2007). Toward a public administration theory of public service motivation. Public Manag. Rev. 9, 545–556. doi: 10.1080/14719030701726697

Vandenabeele, W. (2008). Government calling: public service motivation as an element in selecting government as an employer of choice. Public Admin. 86, 1089–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00728.x

Vandenabeele, W. (2009). The mediating effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on self-reported performance: more robust evidence of the PSM-performance relationship. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 75, 11–34. doi: 10.1177/0020852308099504

Vandenberghe, C., Panaccio, A., Bentein, K., Mignonac, K., and Roussel, P. (2011). Assessing longitudinal change of and dynamic relationships among role stressors, job attitudes, turnover intention, and well-being in neophyte newcomers. J. Organ. Behav. 32, 652–671. doi: 10.1002/job.732

Wang, W. J. (2015). The influence of female civil servants’ job satisfaction on their turnover intention (in Chinese). J. Tianjin Admin. Inst. 17, 17–25.

Williams, L. J., and Hazer, J. T. (1986). Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: are-analysis using latent variable structural equation methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 219–233. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.219

Wombacher, J. C., and Felfe, J. (2017). Dual commitment in the organization: effects of the interplay of team and organizational commitment on employee citizenship behavior, efficacy beliefs, and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 102, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.004

Wright, B. E., and Pandey, S. K. (2008). Public service motivation and the assumption of person-organization fit: testing the mediating effect of value congruence. Admin. Soc. 40, 502–521. doi: 10.1177/0095399708320187

Wright, T. A., and Bonett, D. G. (2007). Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as nonadditive predictors of workplace turnover. J. Manag. 33, 141–160. doi: 10.1177/0149206306297582

Wynen, J., Op de Beeck, S., and Hondeghem, A. (2013). Interorganizational mobility within the US federal government: examining the effect of individual and organizational factors. Public Admin. Rev. 73, 869–881. doi: 10.1111/puar.12113

Yousaf, A., Sanders, K., and Abbas, Q. (2015). Organizational/occupational commitment and organizational/occupational turnover intentions A happy marriage? Pers. Rev. 44, 470–491. doi: 10.1108/PR-12-2012-0203

Zalewska, A. M. (2011). Relationships between anxiety and job satisfaction-Three approaches: ‘Bottom-up’, ‘top-down’ and ‘transactional’. Pers. Individ. Differ. 50, 977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.013

Zeffane, R., and Melhem, S. J. B. (2017). Trust, job satisfaction, perceived organizational performance and turnover intention: a public-private sector comparison in the United Arab Emirates. Empl. Relat. 39, 1148–1167. doi: 10.1108/ER-06-2017-0135

Keywords: public service motivation, job attitudes, turnover intention, public sector, public employee

Citation: Gan K-P, Lin Y and Wang Q (2020) Public Service Motivation and Turnover Intention: Testing the Mediating Effects of Job Attitudes. Front. Psychol. 11:1289. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01289

Received: 21 February 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020;

Published: 23 June 2020.

Edited by:

Nicola Mucci, University of Florence, ItalyReviewed by:

Vincenzo Cupelli, Retired, Sesto Fiorentino, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Gan, Lin and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kai-Peng Gan, a2FpcGVuZ19nYW5AYWxpeXVuLmNvbQ==; Yun Lin, Y2F0aGVyaW5lNzVAMTYzLmNvbQ==