- 1Changzhou Institute of Industry Technology, Changzhou, China

- 2Office of Physical Education, Chienkuo Technology University, Changhua, Taiwan

- 3Department of Business Management, National Taichung University of Science and Technology, Taichung City, Taiwan

- 4Graduate Institute of Sports and Health Management, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan

The purpose of this study is to explore the members of golf clubs in the central region of Taiwan and find out whether their involvement in activities affects the degree of place attachment and to add the two factors of activity experience and experience value so as to develop a theoretical framework. A questionnaire survey was used to collect 534 samples from golf clubs in central Taiwan for analysis using the following research tools: the Activity Involvement scale, Place Attachment scale, and Likert psychological scale. The results of the study show that (1) activity involvement has a significant positive impact on place attachment, activity experience, and experience value; (2) activity experience has a significant positive impact on experience value; (3) experience value has a significant positive impact on place attachment. This result verifies the theory that activity involvement impacts place attachment. It is suggested that the relevant bodies should strengthen the incentives given in the activities and strengthen the value of the leisure experience so as to facilitate the development of related industries in the future.

Introduction

With economic growth, the demands of modern people for quality of life are increasing day by day, and they are beginning to pursue a variety of leisure activities (Wang et al., 2012). Leisure activities are considered to improve quality of life and health (Vassiliadis et al., 2013a; Chick et al., 2016; Mehraliyev et al., 2019). There are many kinds of leisure activities, but according to degree of participant involvement, leisure activities can be roughly divided into two types: casual and serious (Scott, 2012). Golf, the game discussed in this study, is a kind of serious leisure activity. Those who engage in serious leisure activities (such as golf) must have certain professional skills (such as with golf technology) and invest a certain amount of time, money, and other resources in the activities they are engaged in. Serious leisure activities are thus usually highly involving activities, and the leisure benefits to the participants are higher than from casual leisure activities. Barbieri and Sotomayor (2013) summarize the differences in benefits between the two types of leisure, including social difficulties that are span difficulties, self-growth, engaging in leisure activities as a career, achieving certain long-term benefits, constructing a self-image, and creating leisure activities.

Sport has gained increasing popularity in Taiwan. This is partly due to the success of many well-known athletes. Some of the more popular forms of sport are basketball, baseball, badminton, and tennis. After Yani Tseng won many international trophies, golf also gained significantly in popularity. However, because golf requires a large area of well-maintained grassland, which is quite scarce in Taiwan, golf remains a very expensive sport. An aging society has become the trend of the future, and as a result, enterprises have increasingly begun to take notice of the value of this market segment and to develop the expertise to meet its product needs, including travel and leisure products (Kim et al., 2015), and golf is a leisure activity that is good for the elderly. Danylchuk et al. (2015) found that more and more women are beginning to join the ranks of golf leisure participants, and as the market of older people expands, the importance of golf increases. Further, some companies are using technology to develop virtual golf courses and to offer a variety of golf activities for consumers to choose from, and so golf-related research is becoming increasingly important (Han et al., 2014).

Involvement means the degree to which an individual perceives a person, thing, or activity as important because of his or her needs, values, and interests (Chiu et al., 2014). Chiu et al. (2014) posit that the higher the level of activity involvement, the greater the willingness to partake in and frequency of activities. The concept of involvement stems from consumer behavior, which involves five elements, namely importance, pleasure, symbolism, risk, and risk consequences (Laurent and Kapferer, 1985; Kyle et al., 2003; Hwang et al., 2005; Mansfeld and McIntosh, 2009; Vassiliadis et al., 2013b). These five elements affect the consumer’s willingness to purchase a product or service and the attitude toward the product or service. Later, the concept of involvement was adopted in tourism and leisure-related fields (Lu et al., 2015) and termed activity involvement, meaning a person’s level of immersion in the activity experience (Prayag and Ryan, 2012), while the introduction of activity involvement are considered to be one of the important variables for predicting tourism or leisure behavior (Prebensen et al., 2012) and attitudes toward a place or activity (Shen et al., 2012). The elements involved in the activity contain three different originals, namely attraction, self-expression, and life center (Funk et al., 2004; Fotiadis and Vassiliadis, 2016); attraction means the attraction of the activity to the person, self-expression means whether people define their own values through the activity, and finally, centrality of life is the impact of the activity on people and their social circles, which coincides with the leisure benefits mentioned by Barbieri and Sotomayor (2013). In other words, as the level of involvement in the activity increases, the leisure benefits that individuals receive from the activity increase, and they are more willing to continue to engage in the activity.

In summary, the research problem is mainly based on golf leisure activities, taking golf course customers as an example to explore the degree of involvement of golf course customers in their activities and to understand their leisure behavior. Based on this research question, the purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between golf course customer activity, activity experience, experience value, and local attachment. It is hoped that through this research, we will develop a deeper understanding of golf leisure activities and provide advice to the relevant industries.

Literature Review

Golf-Related Research

In the past, there have been many studies on different market segments, such as seniors or women (Stubbs and MacGregor, 1997; Danylchuk et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015), and Shoemaker (1989) found that the elderly are not a completely homogeneous market. This means that even among older people, the motivations and reasons for engaging in golf will vary from person to person, thus affecting their leisure activities (Danylchuk et al., 2015). This has deep implications for this study, in that even people of the same age group may have significant differences in their level of activity involvement, and this will have an impact on their subsequent behavior.

In addition, because technology is changing with each passing day and land is expensive in some countries, some countries have begun to develop virtual golf courses, and there has been corresponding academic research (Han et al., 2014). Some countries, such as Cyprus, have come to treat golf as a major business area. Boukas and Ziakas (2013) propose that the golf business is worth investing in as a tourist attraction. There are two main reasons for this. First, the ordinary customers who engage in golf are more likely to be repeat tourists, and the second is because of golf. The balls are targeted more at high-spending groups. From these studies, the importance of golf balls and related research topics can be observed.

Regarding the relationship between activity involvement and local attachment, Lewicka (2011) reviewed nearly 400 related studies published in 120 different journals and identified the importance and intensity of this relationship. Place attachment refers to the relationship between people and specific places (Hwang et al., 2005; Lee and Shen, 2013), usually because of past positive experience, and thus gradually became attached to the place (Kyle et al., 2003). The concept of local attachment is applied in many different fields of research, and the scale of the “place” varies. For example, there is research on a specific restaurant as a subject of local attachment (Debenedetti et al., 2014). From a whole range of research (Ramkissoon, 2015), it can be seen that the application of this concept of local attachment can be carried out in different scales, different industries, and with different variables. Nevertheless, the causal relationship between activities involved in local attachment is still the most commonly used chain of relationships among scholars (Stubbs, 1997; Lewicka, 2011). Therefore, this study also uses this as the infrastructure to construct the framework of this study.

Hypothesis Development

The relationship between people and places is one of the important topics that academic circles are continuing to explore (Lewicka, 2011). The concept of local attachment was born in, and the concept of local attachment is often applied by, the research institutes of the leisure tourism industry. Most of them are scholars. There is agreement that the degree of involvement associated with the activity is an important pre-institutional factor of local attachment (Kyle et al., 2003). The main concept is that when a person puts more effort into an activity in a place, it will produce stronger feelings, and the feeling of local attachment will then form. This study, therefore, puts forward the following hypothesis:

H1: The “activity involvement” of golf course customers will positively affect their “local attachment.”

The relationship between activity involvement and activity experience stems from the concept of flow (Cheng et al., 2016). Its discussion shows that when a person is fully involved in an activity, it will be awkward. The ecstasy of realm, and thus better experience the fun and benefits of the event. This concept is applied in many leisure activities, especially in serious leisure activities, such as mountaineering (Cheng et al., 2016; Fotiadis et al., 2019), music appreciation or performance (Diaz, 2013; Wrigley and Emmerson, 2013), dance (Thin et al., 2013), etc., so this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: The “activity involvement” of golf course customers will positively affect their “activity experience.”

The concepts of customer experience and experience value are derived from marketing (Schmitt and Zarantonello, 2013), mainly for industries that rely on the provision of intangible goods or services, because the customer does not obtain the actual goods, so the goods obtained or the value of the service can depend on subjective experiences. Examples of such industries are wine tours (X. Chen et al., 2016), music festival tours (Andersson et al., 2017), the hot spring industry (Chen et al., 2013), etc. These terms are also used in leisure sports (Cronin and Lowes, 2016). In addition, online shoppers are not able to see the actual physical goods in advance, so these concepts are also used by online merchants for online shopping research. A relationship between the buying experience and its experience value has been explored by Bilgihan et al. (2014), and the current study argues that there is a clear causal relationship between the activity experience and the experience value. The corresponding hypothesis is:

H3: The “activity experience” of golf course customers will positively affect their “experience value.”

The extent that individuals interact with the people, things, or activities provided by a particular place is thought to have a significant impact on the formation of their local attachment (Prayag and Ryan, 2012). Scholars believe that a positive experience can produce unforgettable memories, which in turn add attachment to the place (Huan et al., 2004; Loureiro, 2014; Fotiadis et al., 2016), and even lead to post-event behaviors, such as sharing their experiences with people. For example, the authenticity of a tourist’s experience of a monument will cause local attachment to the monument (Ram et al., 2016). The correlation between experience and local attachment is also applied in sports-related research (Brown et al., 2016), so this study proposes:

H4: The “experience value” of golf course customers will positively affect their “local attachment.”

The degree of activity involvement affects the value of the activity’s own potency (Grohs and Reisinger, 2014). Even when buying physical items, the experience of buying will impact the perception of the value of the actual purchased item (Andrews et al., 2012). From this, it can be seen that the degree of involvement at the time of the event will affect the consumers or the players engaged in the activity, and the value of the goods or services they experience will change. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: The “activity involvement” of golf course customers will positively affect their “experience value.”

The degree of involvement in the activity itself also causes people to have deeper feelings about the place in which they do it (Prayag and Ryan, 2012). This kind of emotion is local attachment. Loureiro (2014) argues that local attachment will produce repeat visitations of respondents. When the place has positive behavioral intentions and behaviors associated with it, this leads to a higher estimate of place value and more enjoyable behaviors when in that place (Ram et al., 2016), so this study proposes:

H6: The “activity experience” of golf course customers will positively affect their “local attachment.”

Methodology

Research Scope, Objects, and Sampling Methods

This study takes the golf course as an example and uses it as the research scope, while the research object is the golf course customer. The survey was conducted from October 1, 2016, to December 31, 2016. This study used a random sampling method to issue questionnaires and cooperated with personnel to retrieve 534 samples. In terms of gender, most respondents were males, accounting for 60.9%. In terms of age group, “21–30 years old” is the most common, accounting for 42.9%, and “younger than 20 years old” is the second-highest, accounting for 21.3%. It can be seen that there are more and more young people investing in golf. In terms of education level, “university/college” was the most common, accounting for 65.4%, and the “postgraduate or above” was the second-highest, accounting for 21.3%.

Questionnaire Design

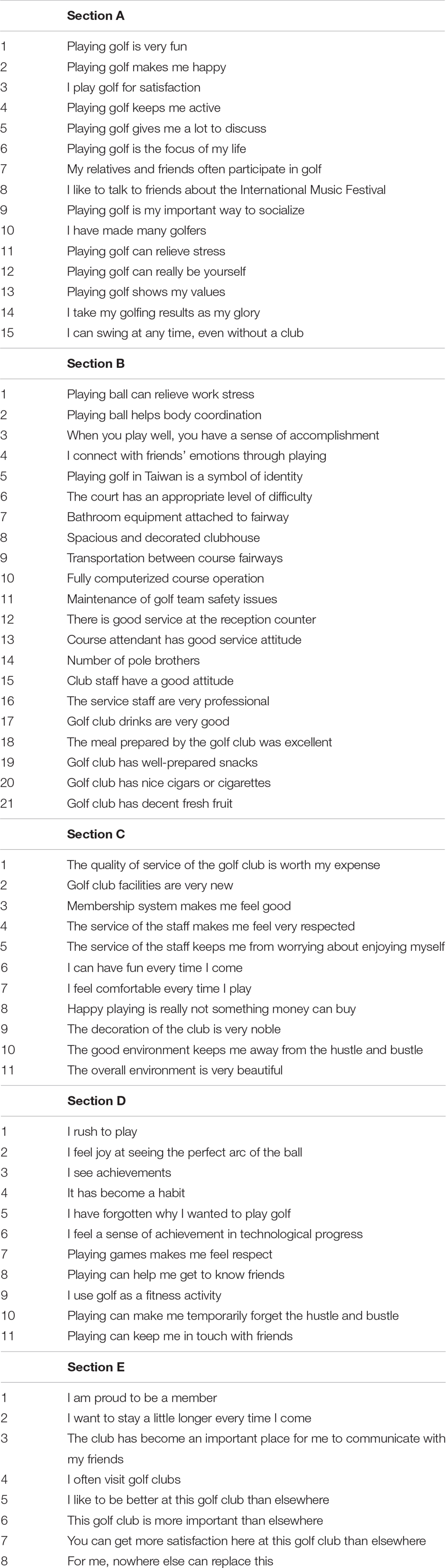

The questionnaire of this study consists of five parts. The main purpose of the first part is to investigate the socio-economic background of the respondents. The other four parts are the four facets of the study, namely activity involvement, activity experience, experience value, and local attachment. In terms of activity involvement, according to the opinions of Funk et al. (2004), it contains three different originals, namely, attraction, self-expression, and life center. For activity experience, according to Han et al. (2014), comments include health environment experience, environmental experience, social experience, and catering-related hospitality services. In terms of experience value, according to the opinions of Chen et al. (2014), customer return on investment, quality of service, pleasure, and beauty are considered. Finally, in terms of local attachment, according to Hwang et al. (2005) and Lee and Shen (2013), local attachment and local identity are considered. Please see the Appendix for the detailed measurement of the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

To test the hypotheses, the data were analyzed by Amos Software to model the structure and understand the causal relationship between its elements.

To achieve rigor in the structural equation model, first, the reliability and validity of the data were tested. Common Cronbach’s α (Nunnally, 1978), compositional validity, and average extraction variation (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) were calculated and tested.

In order to ensure the compatibility of the model, this study also examined whether the fitness indicators met the standards proposed by other scholars (Hooper et al., 2008; Hair et al., 2009; Kline, 2011). Finally, the overall research structure was analyzed, as was the verification the relevant hypotheses.

Results

Reliability and Validity

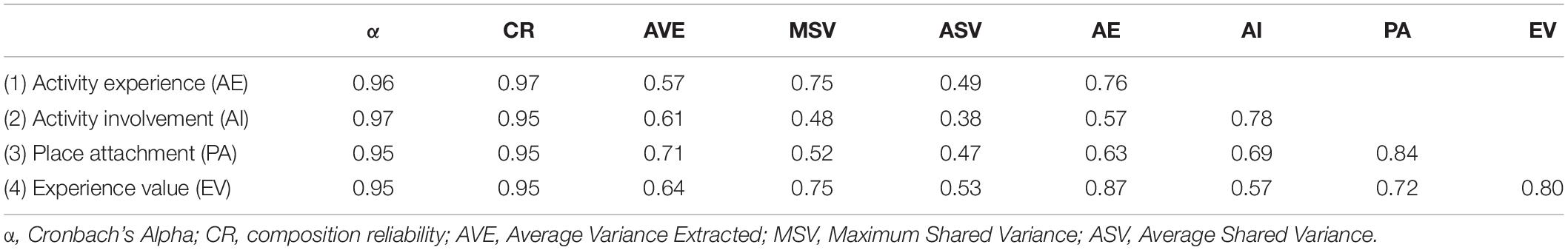

The reliability and validity indicators related to this study are summarized in Table 1. According to Nunnally (1978), the internal consistency of a Cronbach’s α value above 0.9 is excellent, indicating that the reliability of each facet is sufficient, while 0.7 or above is within an acceptable range but and 0.8 is better.

Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggested that in structural equation model analysis, the composition reliability (CR) of each facet should be better than 0.7, the lowest should be 0.6, and the average extraction variation (Average Variance Extracted, AVE) needs to reach 0.5 to meet an excellent standard is recommended to be at least above 0.36. In addition, the Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) and the Average Shared Variance (ASV) should be as small as possible to ensure the validity level.

According to the analysis results of this study, the Cronbach’s α, CR, and AVE values all have a high quality standard. However, in terms of activity experience and experience value, the MSV is greater than the AVE, indicating that there is a certain degree of commonality between variables or facets. However, this study has reached a high level of indicators, and in non-accurate science, it is difficult to completely discern discriminative problems, so this result has been deemed acceptable for this study.

Hypothesis Testing Results

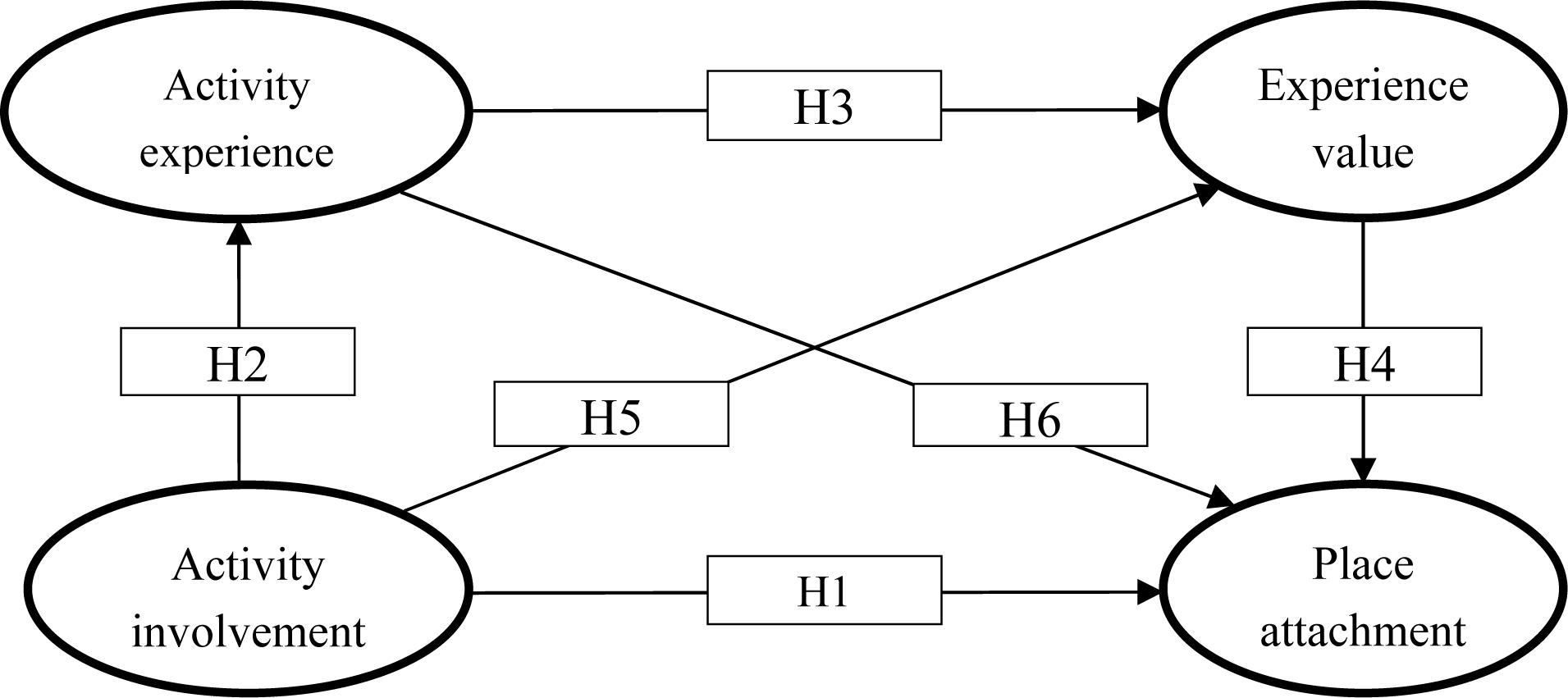

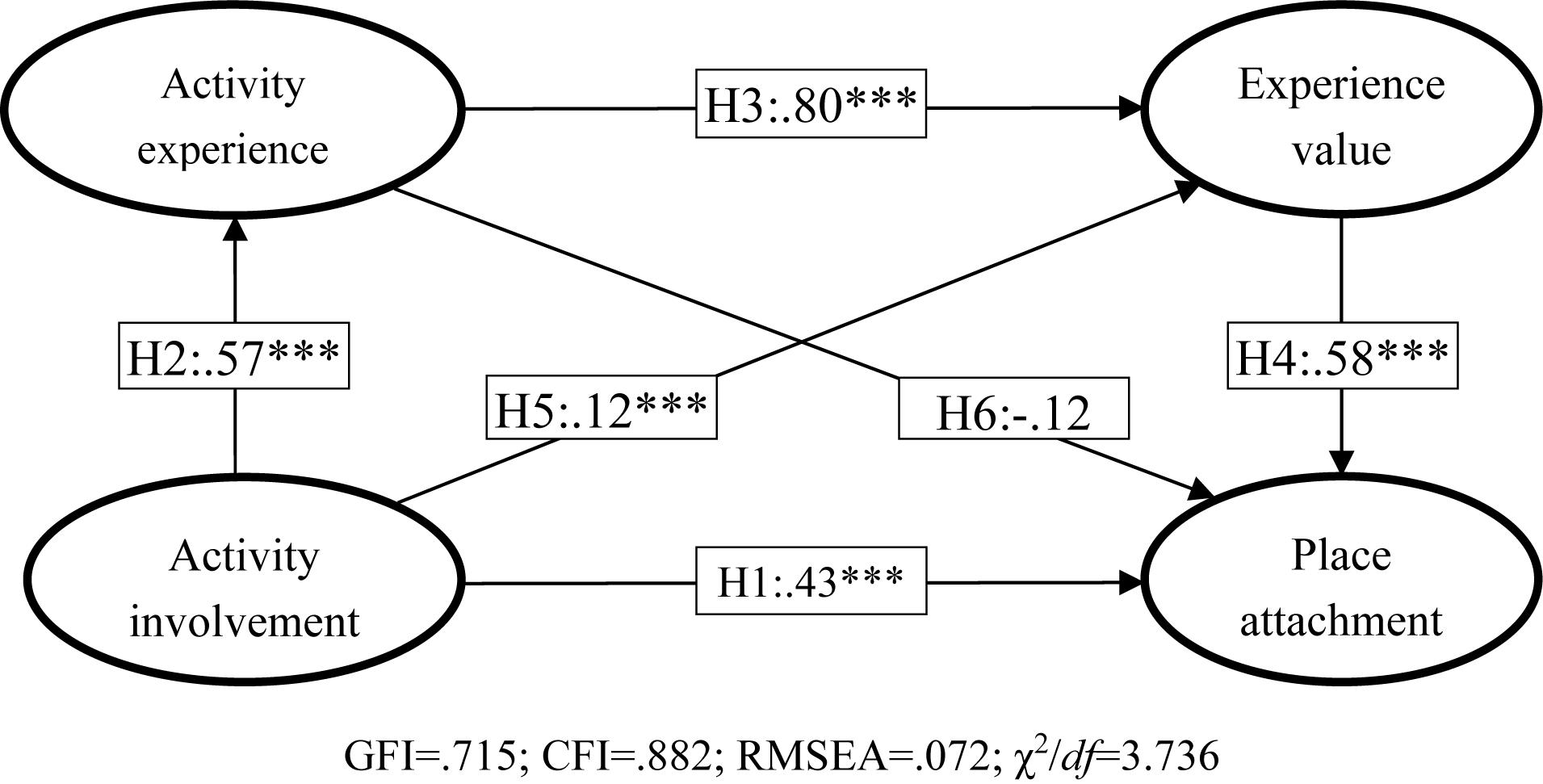

The research model with 6 hypotheses is shown in Figure 1 and the model fit index for this study is shown in Figure 2. The model-related indicators are as follows: GFI = 0.715; CFI = 0.882; RMSEA = 0.072; χ2/df = 3.736. According to the opinion of many scholars (Hooper et al., 2008; Hair et al., 2009; Kline, 2011), GFI and CFI must be at least 0.7 or higher, RMSEA less than 0.08, and chi-square versus degree of freedom (χ2/df) less than 5. The relevant values for this research model are within the acceptable range.

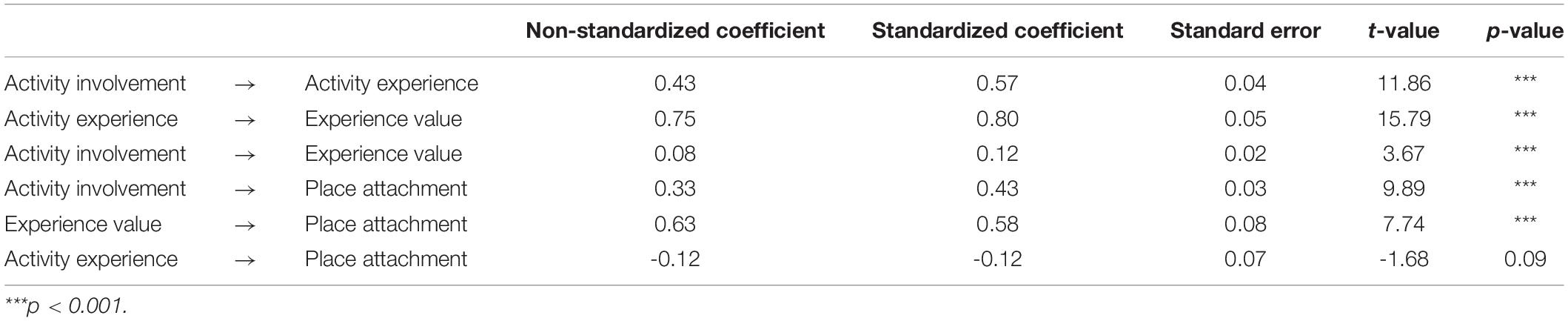

In view of the reliability and validity of the study, the model meets the test criteria, so hypothesis testing was performed. The results are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. According to the results, five of the six hypotheses in this study are supported, and the level of significance is less than 0.001. The results are as follows.

H1: The “activity involvement” of golf course customers will positively affect their “place attachment” is supported because the standardized β is 0.43 and the p-value is significant.

H2: The “activity involvement” of golf course customers will positively affect their “activity experience” is supported because the standardized β is 0.57 and the p-value is significant.

H3: The “activity experience” of golf course customers will positively affect their “experience value” is supported because the standardized β is 0.80 and the p-value is significant.

H4: The “experience value” of golf course customers will positively affect their “place attachment” is supported because the standardized β is 0.58 and the p-value is significant.

H5: The “activity involvement” of golf course customers will positively affect their “experience value” is supported because the standardized β is 0.12 and the p-value is significant.

H6: The “activity experience” of golf course customers will positively affect their “place attachment” is not supported because the p-value is 0.09, greater than 0.05.

The model proposed in this study actually has multiple intermediaries.

For example, activity involvement→experience value is mediated through activity experience. The fact that all three paths are significant means that the mediation is only partial at best. The results show that activity involvement is more important in terms of generating good golfing experience and eventually place attachment. The “activity value” plays an intermediary role between “activity experience” and “place attachment”. In other words, the respondents’ “activity experience” does not directly generate their “place attachment,” but it will be indirectly affected through the creation of “experience value.”

Conclusion and Suggestions

Conclusion

Along with economic growth, the demands of modern people for quality of life are increasing day by day, and they are pursuing a variety of leisure activities (Wang et al., 2012). Combined with the growth of the aging market (Kim et al., 2015) and of female customers (Danylchuk et al., 2015), this has caused the golf industry to spring up and develop rapidly. Based on this background of earlier research, this study aimed to understand the relationship between activity involvement, activity experience, experience value, and place attachment in golf leisure activities, thereby constructing behavior patterns to provide a reference for operators planning and operating golf courses. Therefore, this study has both theoretical and practical importance.

Based on the above literature review regarding the golf industry, as well as the concepts of activity involvement and place attachment, we know that the golf industry is facing a changing environment, including in business model and in market structure. Understanding the behavior of this market an important goal so as to retain customers and expand to new customers. Therefore, this paper not only has rational meaning in theory but also has practical value for the golf industry.

Suggestions

In terms of academics: In the past, there were few related literatures and studies on activity involvement, activity experience, experience value, and place attachment in various leisure industries, and there was no in-depth discussion and research on the golf industry and the relationships between the above variables. This study suggests that the research model of this paper be used while adding other variables. The results will establish a more complete consumer behavior model, which will enable the academic community to establish a more complete theoretical foundation and understanding of research regarding golf course customers.

In terms of national development: This study explores the relationship between the activity involvement, activity experience, experience value, and place attachment of golf courses. Therefore, government is recommended to: (1) encourage people to engage in golf activities, (2) promote the advantages of golf to enhance the health of the people and improve their leisure and living standards, (3) encourage entrepreneurs to upgrade the environment and activities at golf courses, and (4) develop and promote the golf industry to enhance the positive image of the city or country.

In other applications: Based on the background of this research, this study reveals the relationship between the activity involvement, activity experience, experience value, and place attachment of golf customers. If this study proves the relationship between activity involvement and place attachment, the research model of this study should also be able to be applied to different leisure or sports industries for planning and management.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants to participate in this study was not required in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

CC: responsibility of this paper included substantially contributing to developing the research framework, to designing the methodology, to revising the manuscript, and to writing authors’ response notes. S-WL: responsibility of this paper included substantially contributing to designing the methodology, to conducting the survey, to writing, and to searching for references. S-YH and C-HW responsibility of this paper included substantially contributing to conducting the survey, to writing, and to searching for references.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Universities in Jiangsu (2018SJA1833) and Changzhou Institute of Industry Technology Project (YB201813101007).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Andersson, T. D., Armbrecht, J., and Lundberg, E. (2017). Linking event quality to economic impact a study of quality, satisfaction, use value and expenditure at a music festival. J. Vacation Mark. 23, 114–132. doi: 10.1177/1356766715615913

Andrews, L., Drennan, J., and Russell-Bennett, R. (2012). Linking perceived value of mobile marketing with the experiential consumption of mobile phones. Eur. J. Mark. 46, 357–386. doi: 10.1108/03090561211202512

Barbieri, C., and Sotomayor, S. (2013). Surf travel behavior and destination preferences: an application of the serious leisure inventory and measure. Tour. Manag. 35, 111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.005

Bilgihan, A., Okumus, F., Nusair, K., and Bujisic, M. (2014). Online experiences: flow theory, measuring online customer experience in e-commerce and managerial implications for the lodging industry. Inf. Technol. Tour. 14, 49–71. doi: 10.1007/s40558-013-0003-3

Boukas, N., and Ziakas, V. (2013). Exploring perceptions for Cyprus as a sustainable golf destination: motivational and attitudinal orientations of golf tourists. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 14, 39–70. doi: 10.1504/IJSMM.2013.060639

Brown, G., Smith, A., and Assaker, G. (2016). Revisiting the host city: an empirical examination of sport involvement, place attachment, event satisfaction and spectator intentions at the London Olympics. Tour. Manag. 55, 160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.010

Chen, H.-B., Yeh, S.-S., and Huan, T.-C. (2014). Nostalgic emotion, experiential value, brand image, and consumption intentions of customers of nostalgic-themed restaurants. J. Bus. Res. 67, 354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.01.003

Chen, K.-H., Liu, H.-H., and Chang, F.-H. (2013). Essential customer service factors and the segmentation of older visitors within wellness tourism based on hot springs hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 35, 122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.05.013

Chen, X., Goodman, S., Bruwer, J., and Cohen, J. (2016). Beyond better wine: the impact of experiential and monetary value on wine tourists’ loyalty intentions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 21, 172–192. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2015.1029955

Cheng, T.-M., Hung, S.-H., and Chen, M.-T. (2016). The influence of leisure involvement on flow experience during hiking activity: using psychological commitment as a mediate variable. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 21, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2014.1002507

Chick, G., Hsu, Y.-C., Yeh, C.-K., Hsieh, C.-M., Bae, S. Y., and Iarmolenko, S. (2016). Cultural consonance in leisure, leisure satisfaction, life satisfaction, and self-rated health in urban Taiwan. Leis. Sci. 38, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2016.1141734

Chiu, Y.-T. H., Lee, W.-I., and Chen, T.-H. (2014). Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: antecedents and implications. Tour. Manag. 40, 321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.013

Cronin, C. J., and Lowes, J. (2016). Embedding experiential learning in HE sport coaching courses: an action research study. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 18, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2016.02.001

Danylchuk, K., Snelgrove, R., and Wood, L. (2015). Managing women’s participation in golf: a case study of organizational change. Leisure 39, 61–80. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2015.1074394

Debenedetti, A., Oppewal, H., and Arsel, Z. (2014). Place attachment in commercial settings: a gift economy perspective. J. Consum. Res. 40, 904–923. doi: 10.1086/673469

Diaz, F. M. (2013). Mindfulness, attention, and flow during music listening: an empirical investigation. Psychol. Music 41, 42–58. doi: 10.1177/0305735611415144

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.2307/3150980

Fotiadis, A., Nuryyev, G., Achyldurdyyeva, J., and Spyridou, A. (2019). The impact of EU sponsorship, size, and geographic characteristics on rural tourism development. Sustainability 11:2375. doi: 10.3390/su11082375

Fotiadis, A., and Vassiliadis, C. (2016). Service quality on theme parks. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 17, 178–190. doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2015.1115247

Fotiadis, A., Yeh, S.-S., and Huan, T.-C. T. C. (2016). Applying configural analysis to explaining rural-tourism success recipes. J. Bus. Res. 69, 1479–1483.

Funk, D. C., Ridinger, L. L., and Moorman, A. M. (2004). Exploring origins of involvement: understanding the relationship between consumer motives and involvement with professional sport teams. Leis. Sci. 26, 35–61. doi: 10.1080/01490400490272440

Grohs, R., and Reisinger, H. (2014). Sponsorship effects on brand image: the role of exposure and activity involvement. J. Bus. Res. 67, 1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.008

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7 Edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Han, H., Baek, H., Lee, K., and Huh, B. (2014). Perceived benefits, attitude, image, desire, and intention in virtual golf leisure. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 23, 465–486. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2013.813888

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., and Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Methods 6, 53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.07.001

Huan, T.-C., Beaman, J., and Shelby, L. (2004). No-escape natural disaster: mitigating impacts on tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 31, 255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.10.003

Hwang, S.-N., Lee, C., and Chen, H.-J. (2005). The relationship among tourists’ involvement, place attachment and interpretation satisfaction in Taiwan’s national parks. Tour. Manag. 26, 143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.11.006

Kim, H., Woo, E., and Uysal, M. (2015). Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 46, 465–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.002

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kyle, G., Graefe, A., Manning, R., and Bacon, J. (2003). An examination of the relationship between leisure activity involvement and place attachment among hikers along the Appalachian trail. J. Leis. Res. 35, 249–273.

Laurent, G., and Kapferer, J.-N. (1985). Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J. Mark. Res. 22, 41–53. doi: 10.1177/002224378502200104

Lee, T. H., and Shen, Y. L. (2013). The influence of leisure involvement and place attachment on destination loyalty: evidence from recreationists walking their dogs in urban parks. J. Environ. Psychol. 33, 76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.11.002

Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: how far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31, 207–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Loureiro, S. M. C. (2014). The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 40, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.02.010

Lu, L., Chi, C. G., and Liu, Y. (2015). Authenticity, involvement, and image: evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 50, 85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.026

Mansfeld, Y., and McIntosh, A. J. (2009). Spiritual hosting and tourism: the host-guest dimension. Tour. Recreat. Res. 34, 157–168. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2009.11081587

Mehraliyev, F., Choi, Y., and Koseoglu, M. A. (2019). Social structure of social media research in tourism and hospitality. Tour. Recreat. Res. 44, 451–465. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2019.1609229

Prayag, G., and Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius the role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 51, 342–356.

Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., and Uysal, M. (2012). Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. J. Travel Res. 52, 253–264. doi: 10.1177/0047287512461181

Ram, Y., Björk, P., and Weidenfeld, A. (2016). Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tour. Manag. 52, 110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.010

Ramkissoon, H. (2015). Authenticity, satisfaction, and place attachment: a conceptual framework for cultural tourism in African island economies. Dev. South. Afr. 32, 292–302. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2015.1010711

Schmitt, B., and Zarantonello, L. (2013). Consumer experience and experiential marketing: a critical review. Rev. Mark. Res. 10, 25–61. doi: 10.1108/S1548-643520130000010006

Scott, D. (2012). Serious leisure and recreation specialization: an uneasy marriage. Leis. Sci. 34, 366–371. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2012.687645

Shen, S., Guo, J., and Wu, Y. (2012). Investigating the structural relationships among authenticity, loyalty, involvement, and attitude toward World Cultural Heritage Sites: an empirical study of Nanjing Xiaoling Tomb, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 19, 103–121. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2012.734522

Shoemaker, S. (1989). Segmentation of the senior pleasure travel market. J. Travel Res. 27, 14–21. doi: 10.1177/004728758902700304

Stubbs, D. (1997). On managing golf courses ecologically. Tour. Recreat. Res. 22, 64–66. doi: 10.1080/02508281.1997.11014806

Stubbs, D., and MacGregor, L. (1997). Golf in Europe. Tour. Recreat. Res. 22, 71–73. doi: 10.1080/02508281.1997.11014788

Thin, A. G., Brown, C., and Meenan, P. (2013). User experiences while playing dance-based exergames and the Influence of different body motion sensing technologies. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2013:603604.

Vassiliadis, C., Fotiadis, A., and Piper, L. (2013a). Analysis of rural tourism websites: the case of Central Macedonia. Tourismos 8, 247–263.

Vassiliadis, C., Priporas, C., and Andronikidis, A. (2013b). An analysis of visitor behaviour using time blocks: a study of ski destinations in Greece. Tour. Manag. 34, 61–70.

Wang, C.-H., Chen, H.-T., and Chen, K.-S. (2012). A study of process quality assessment for golf club-shaft in leisure sport industries. J. Test. Eval. 40, 512–519. doi: 10.1520/JTE104269

Appendix

Keywords: golf, clubs, activities involved, place attachment, leisure sport

Citation: Chen C, Lin S-W, Hsu S-Y and Wu C-H (2020) A Study on the Place Attachment of Golf Club Members. Front. Psychol. 11:408. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00408

Received: 11 January 2020; Accepted: 24 February 2020;

Published: 09 April 2020.

Edited by:

Anestis Fotiadis, Zayed University, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Shi Shuo, National Quemoy University, TaiwanYuChih Max Lo, National Chin-Yi University of Technology, Taiwan

Copyright © 2020 Chen, Lin, Hsu and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chun Chen, Y2hlbmNodW5AY2lpdC5lZHUuY24=

Chun Chen

Chun Chen Shu-Wang Lin2

Shu-Wang Lin2 Shih-Yun Hsu

Shih-Yun Hsu