- 1Department of Health Promotion and Development, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

- 2Department of Psychosocial Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

- 3Public Health Research Group, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain

Child welfare workers (CWWs) often work under conditions similar in nature to workers within safety critical organizations (SCOs). This is because most of their work surrounds child neglect, securing homes for foster children, haphazard, and intricate cases, among other things, and where making wrong decisions, inattention to details, and the likes could lead to adverse consequences especially for the kids within their care. Research has shown that employees who experience support at work often report less stress symptoms, burnout, and a host of other negative workplace experiences. Experience of support at work has also been found to boost employees’ retention, job satisfaction, and productivity. Despite this development, research exploring the essence of workplace support among CWW is very scarce in the literature, and we know very little about the type of workplace support and their influence on a host of workplace outcomes, especially the negative ones like secondary traumatic stress, aggression, and violence toward CWWs. The purpose of the current scoping review was to uncover what is known about workplace support and their relationship with workplace outcomes among CWWs. The authors explored four databases and identified 55 primary studies investigating workplace support and workplace outcomes among CWWs in the review. Studies mostly framed support under three main support types of coworker/peer support, social/organizational/management support, and supervisor/leadership support. Findings showed that workplace support has a positive impact on workplace variables like job satisfaction, engagement, commitment, and reduces the risk of turnover, burnout, and other negative workplace variables. The review highlights possible directions for future research.

Introduction

In Norway, a huge number of child welfare workers (CWWs) recently took to the streets with slogans like “HeiErna” (Erna refers to the prime minister of Norway, Erna Solberg). These employees demonstrated to protest the shortage of employees amidst the ever-increasing workloads they face from day to day. According to one of the protesters, the Norwegian government’s promises to increase competences and learning among this workgroup will fail if there are insufficient employees, creating heavy workloads and demands (as cited in www.frifagbevegelsen.no). We know from past research within this workgroup that employees are often confronted with heavy workloads along with other types of unsuitable workplace events.

The purpose of this scoping review is to assess the essence of workplace support especially among CWWs vis-à-vis their constant exposure to risks at work. Owing to the nature of their work (child neglect, securing homes for foster children, haphazard, and intricate cases, among other things), CWWs often find themselves within zones bearing resemblance to employees within safety critical organizations (SCOs). This implies that wrong decisions, inattention to details, and the likes could lead to adverse consequences especially for the kids within their care. Risks at work have been associated with stress, disrupted productivity, sickness, and other negative health outcomes (Cox, 1993; Griffths, 1998; Cox et al., 2000, 2007; Leka et al., 2007). Working around children with troubled pasts, vulnerabilities, and complicated upbringing, CWWs deal with innumerable demanding intricacies within their field. Past research has shown that child welfare is one of the most complex, stressful, and emotionally demanding within the field of human services (Madden et al., 2014; McFadden et al., 2015). Across countries there are concerns that many social workers leave their jobs in child welfare services. Vacancies and a constant stream of new employees have negative effects both on the remaining staff of social workers and the clients by creating instability in services for vulnerable children and families. We know from past research that several workplace resources like job satisfaction, engagement, and social support provide ameliorating effects on employees’ experiences of workplace risks like turnover and burnout. For instance, social support has been found to reduce the risk of turnover, burnout, and other debilitating workplace risks (Karasek and Theorell, 1990; Brough and Pears, 2004; DePanfilis and Zlotnik, 2008). In this regard, getting an overview of the roles of workplace support for this work group will contribute immensely to enhancing and boosting their performance and well-being.

A review of the literature shows a seemingly one-sided focus on negative events or workplace variables like turnover and turnover intentions among CWWs. Only very few studies have explored novel topics that are not only related to turnover/turnover intentions (Jacquet et al., 2008; Hwang and Hopkins, 2012; Lizano et al., 2014; Kim and Mor Barak, 2015). For instance, Mor Barak et al. (2001) study the antecedents to retention and turnover among human service employees (including child welfare). DePanfilis and Zlotnik (2008) conducted a systematic review of the literature concerning the retention of frontline employees in child welfare services. Findings from their review pointed toward the importance of several workplace factors implicated in employees’ decision to stay. These factors included employees’ commitment, low levels of emotional exhaustion, self-efficacy, support at work, as well as salary and benefit. Likewise, Kim and Kao (2014) conducted a meta-analytical review of the predictors of turnover intentions among child welfare employees based in the United States. More recently, McFadden et al. (2015) reviewed the child welfare literature focusing on the role of resilience and burnout. The identified themes (subdivided into individual and organizational themes) among the included studies include coping, secondary traumatic stress, social support and supervision, job satisfaction, workload, professional and organizational commitment, etc. As mentioned above, one notable factor here is the heavy reliance/focus on employees’ intentions to stay or leave. Although some of their findings included/associated with workplace support, to our knowledge, workplace support as a concept has been disproportionately left on the sidelines when discussing psychosocial work environment variables and their importance, especially among CWWs.

Given the unequal focus on the negative workplace occurrences among CWWs, does that imply that CWW only deal with negative experiences at work? Au contraire, most scholars would agree that workplace experiences are seldom a one-way street. Against the backdrop of this knowledge, why has the focus on negative outcomes such as turnover, burnout, and occupational stress continue to increase the past years (Kelloway, 2011, p. 1)? One logical explanation could be the notion that “bad is stronger than good.” Baumeister et al. (2001) maintain that negatively valenced events will generate a greater impact on an individual than positive valenced events of the same type. Adding to this is the high economical and emotional cost of having to replace a sick, absent, or a worker who quits. The impact of this to the employer could have generated vibrating attention in the field, influencing the continuous focus on negative occurrences at work. Judging by these factors, it is reasonable that a host of past research centers on turnover and the likes.

Workplace Support

Before describing the importance of workplace support especially among CWWs, we will briefly present a theory that encapsulates workplace support with other relevant theories in any given work environment. The job-demand resource (JD-R) model provides a more nuanced explanation to what goes on at work. Building on previous balance models of employee well-being [the demand-control model (DCM) by Karasek, 1979; and the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) by Siegrist, 1996], the proponents of the JD-R hold that the exposure of employees to a high demanding work environment coupled with limited autonomy will oftentimes lead to stress and ill health (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007). Furthermore, elevated autonomy will yield a contrasting experience for the employees. The central tenet of this model revolves around two assumed pathways, namely, the health impairment and the motivation processes (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Schaufeli and Taris, 2014). The impairment pathway (also referred to as job demands) involves “those physical, social, organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs” (Demerouti et al., 2001, p. 501). The health impairment could range from job insecurity to role ambiguity, role conflict, unfavorable shift work schedule, and work-home conflict (Schaufeli and Taris, 2014). Job resources or the motivational path centers on those aspects of the job that largely contributes toward the achievement of stated work goals, reduce the impact of job demands and workload, and stimulate growth and development among employees (Schaufeli and Taris, 2014). Examples of job resources are autonomy, advancement, leadership, and social support from both the supervisor and colleagues (Schaufeli and Taris, 2014). The purpose of this scoping review is to assess the importance of workplace support among CWWs.

To get an understanding of workplace support, it is imperative to explore the themes and ideas surrounding it. Workplace support is a sub-arm of social support, which is “the type of assistance that individuals receive from those who come into contact with them in any way” (Papakonstantinou and Papadopoulos, 2010, p. 183). Authors have attempted conceptualizing social support in recent past. This conceptualization varies in focus and content. While some authors focused on categories of support (Huurre et al., 1999), others focus on aspects of social support (Weiss, 1974); elements of support (Birch, 1998; Etzion, 1984), functions of social support (Cohen and Hoberman, 1983), and types of support (Cohen and Wills, 1985; Kef, 1997; Brough and Pears, 2004). Karasek and Theorell (1990) describe workplace support as the sum of support that is available to an individual at the workplace from colleagues and supervisors. In this sense, support could range from receiving advice on a task, appraisals of situations and assignments, information sharing, and emotional support (Karasek and Theorell, 1990; Brough and Pears, 2004; Harris et al., 2007). Past research has shown that workplace support has a positive impact on workplace variables like job satisfaction, engagement, commitment, and negative impact on turnover, burnout, and other negative workplace variables (Karasek and Theorell, 1990; Mor Barak et al., 2001; Brough and Pears, 2004; DePanfilis and Zlotnik, 2008; McFadden et al., 2015). A well-functioning workplace will arguably generate better services to its client than a malfunctioning one. For example, Iversen and Heggen (2016) recently conducted a study on CWWs use of knowledge in their daily work in Norway. Participants reported several factors as vital to performance and quality welfare work. Supervision and colleagues were cited as one of the most important factors. The authors pointed out that “Colleagues and Supervision is not only important for ‘new’ social workers with little experience, but also remains important throughout the career irrespective of working experience and continued education” (Iversen and Heggen, 2016, p. 13).

The Present Study

In line with the above, the current scoping review will attempt to identify the significance of workplace support among CWW. More importantly, the present review will seek to investigate the relationship (if any) between workplace support and workers experience of psychosocial risks. We endeavor to explore the roles and impact of workplace support among CWW as they carry out their day-to-day tasks at work. The knowledge of this will help researchers, practitioners, and policy makers in focusing on ways to encourage and stimulate support at work thereby influencing the well-being and work environment of CWW. Additionally, we will explore the characteristics of the studies in the field. This review will also identify the gaps in the field, if any.

By investigating and capturing the range of studies exploring the importance of workplace support amidst exposures to psychosocial risks within the child welfare sector, this scoping review will be taking the first step in addressing the gaps in the field of child welfare regarding this theme. Are there any gaps in the field? What areas need more research focus? This present review will attempt to answer these questions regarding the focus of future studies in the field. To our knowledge, no earlier studies have attempted capturing the essence of workplace support among workers in this particular sector.

According to the recently published PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA.ScR): checklist and explanation, scoping reviews share numerous components with any other type of knowledge synthesis (Tricco et al., 2018). Scoping reviews have within their scope to “follow a systematic approach to map evidence on a topic and identify main concepts, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps” (Tricco et al., 2018, p. 1). The present review is in line with this relatively new and refined approach to systematic reviews. Using the guidelines as found in the renowned framework of Arksey and O’Malley (2005), this paper aims to employ a systematic and comprehensive exploration of the literature on the workplace support among CWW. This framework has proven to be effective at mapping out the extent, range, and nature of the selected body of research. Our chosen approach is also in line with findings from earlier notable research employing the scoping reviews methodology (Grant and Booth, 2009; Levac et al., 2010; Daudt et al., 2013; Colquhoun et al., 2014; Pham et al., 2014).

Additionally, the current review aims to identify gaps in the literature and provide a summary of results. Specifically, the current paper will employ five key steps as proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005): (1) identify the research question, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Grant and Booth, 2009; Levac et al., 2010; Colquhoun et al., 2014; Pham et al., 2014). As commonly found with scoping reviews, the present study will not make efforts to evaluate the quality of studies nor offer a quantitative synthesis of data. The current scoping review will, however, seek to explore and capture the noteworthy features of an incipient body of evidence. In order to provide a structured overview of the whole research process, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA.ScR) guidelines in reporting this scoping review.

Method

Stage 1: Identify the Research Question

The present scoping review aims to explore the relationship between workplace support and psychosocial risk exposures among CWW. Following recommendations from Arksey and O’Malley (2005), we intend to begin with a broad review area to establish what is available before narrowing the search. Although past research points toward a negative relationship between workplace support and psychosocial risk, an overview of the types of support, and how essential they are is lacking in the field. Earmarking research questions for this review shapes the focus of the study while directing the identification and selection of relevant studies. The research question: What types of workplace support exist in the literature and what roles do they play in workers outcomes?

Stage 2: Identify Relevant Studies

Search Terms

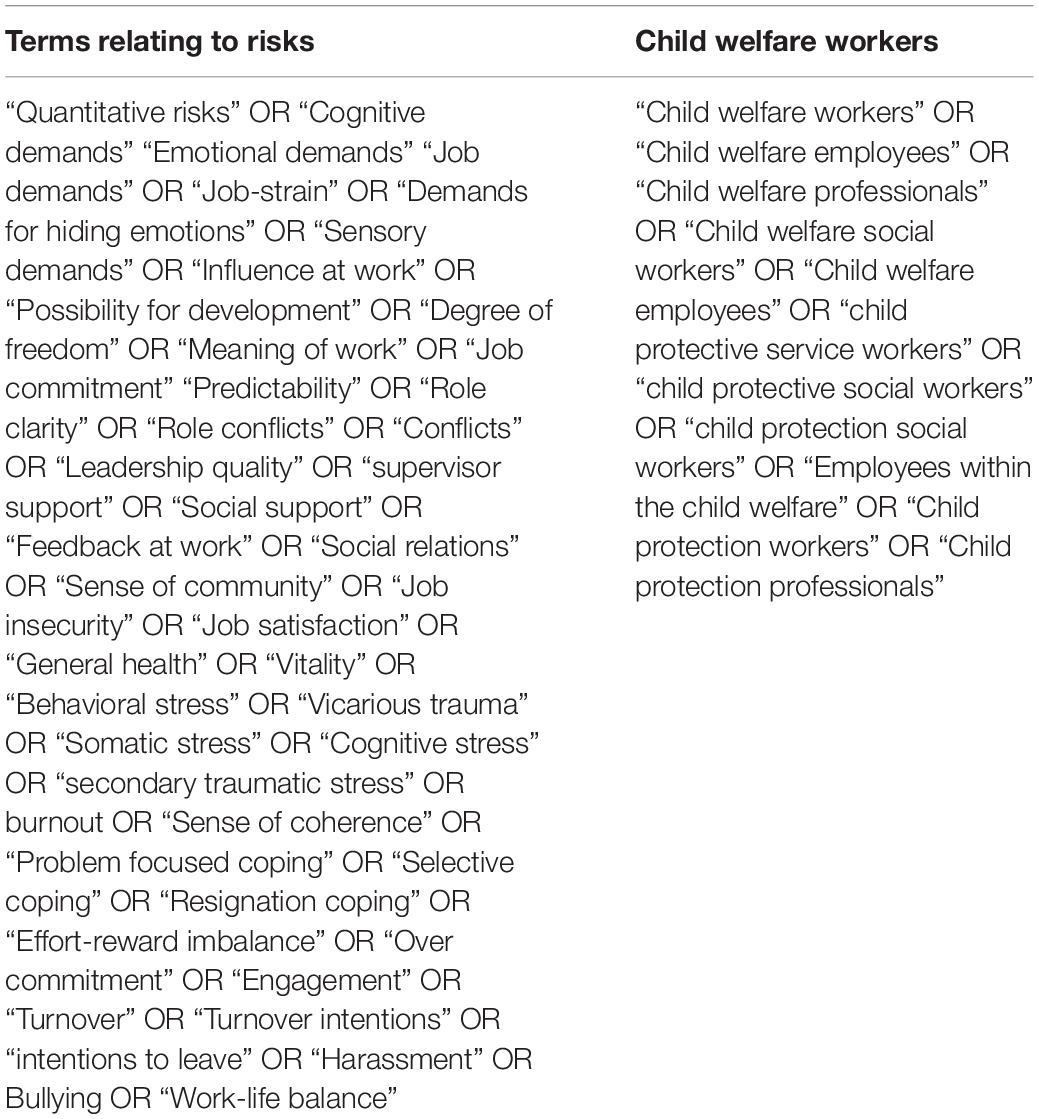

We implemented the bibliographic databases search from April 15 until 21 September 2018 in PsycINFO, Medline, ProQuest, and the Web of Science. A supplementary search was conducted between the periods of 11 September and 25 September 2019. We selected these databases because they provide a full-bodied coverage of peer-reviewed research and publications on work health and well-being, within which psychosocial risks fall. Since past research is inconclusive regarding how workplace support influences other work environment outcomes, we decided to employ a strategy that considered this knowledge. Using keywords from two widely accepted work environment/psychosocial scales (Copenhagen Psychosocial Scale and QPS-Nordic) as our point of departure, we constructed our search terms and conducted a search in the four aforementioned bibliographic databases. In addition to the two psychosocial scales, we also studied and included notable scales/variables from the PRIMA-EF (Guidance on the European Framework for Psychosocial Risk Management). As pointed out earlier, we were unsure of the range and extent of the publications existing on psychosocial risks among child welfare employees, and therefore we set no limits on publication dates. We employed a simple analytical framework (search, appraisal, synthesis, and analysis—SALSA) as well as two separate Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” in retrieving relevant studies. The first author constructed the search strategy with support from the rest of the team. See Table 1 for the full list of the search terms used in the present study.

Stage 3: Study Selection

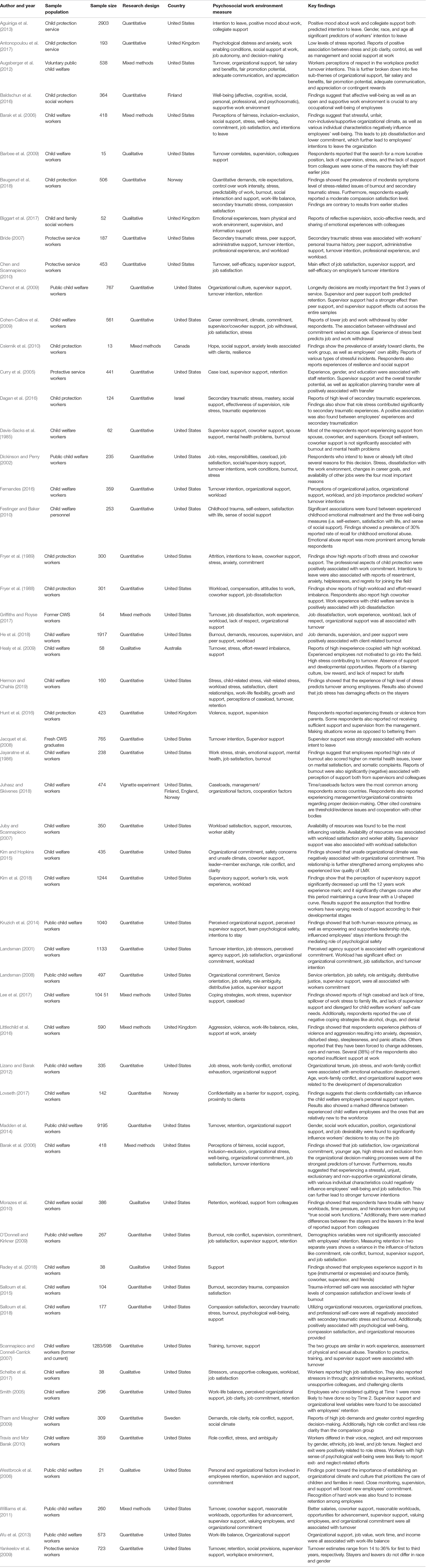

The first author conducted the data screening by going through the titles of articles, keywords, and abstracts following broad relevance criteria. We then embarked on a detailed exploration of the full-texts of the chosen articles. After removing duplicates, we identified 2534 citations from searches of electronic databases, highly cited articles, as well as the reference lists of review articles. We screened the titles and abstracts of the 2534 studies and 2386 citations were excluded (because they did not meet the inclusion criteria). Furthermore, we excluded 127 studies that explored psychosocial risk variables in related settings to child welfare, but that was unclear if child welfare employees were included in the sample (e.g. nurses, doctors, teachers, and other social workers), and 155 studies that explored variables outside the scope of the present study (e.g. organizational change, education, proximity to work, etc.). Finally, we excluded two studies because we were unable to retrieve them (we attempted to reach the authors but received no answer). With 148 full text articles remaining to be retrieved and assessed for eligibility, we excluded studies for the following reasons: 52 were dissertations (not pee-reviewed), 37 measured family engagement and related variables, and 14 were not original empirical research (e.g. reports, commentaries, and theoretical studies). We considered 55 studies eligible for this present review.

Stage 4: Chart the Data

The screening process generated 55 articles that met the inclusion criteria. We developed an extraction spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel in order to maintain a systematic data extraction process. We then moved to Microsoft Word and inserted all of the information from Microsoft Excel into a table. Our coding was guided by the focus of this review. Therefore, we coded included articles by study, sample population, sample size, research design, and psychosocial risk measure and findings.

Stage 5: Collate, Summarize, and Report Results

According to Arksey and O’Malley (2005), the last stage of the review process entails collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. We achieved this by organizing the relevant results into themes, conscientiously paying attention to these themes as they relate to the research questions and focus of the study.

Ongoing Consultation

In order to aid credibility and strength to the review, Arksey and O’Malley (2005) suggest the inclusion of experts in the area of research. For the present review, one professor, two associate professors, and two CWWs with over 12 years of work experience were consulted during the early phase of research questions development, search strategy development, and inclusion criteria. The first author has been involved with two reviews earlier. The fifth author has published more than 10 reviews.

Results

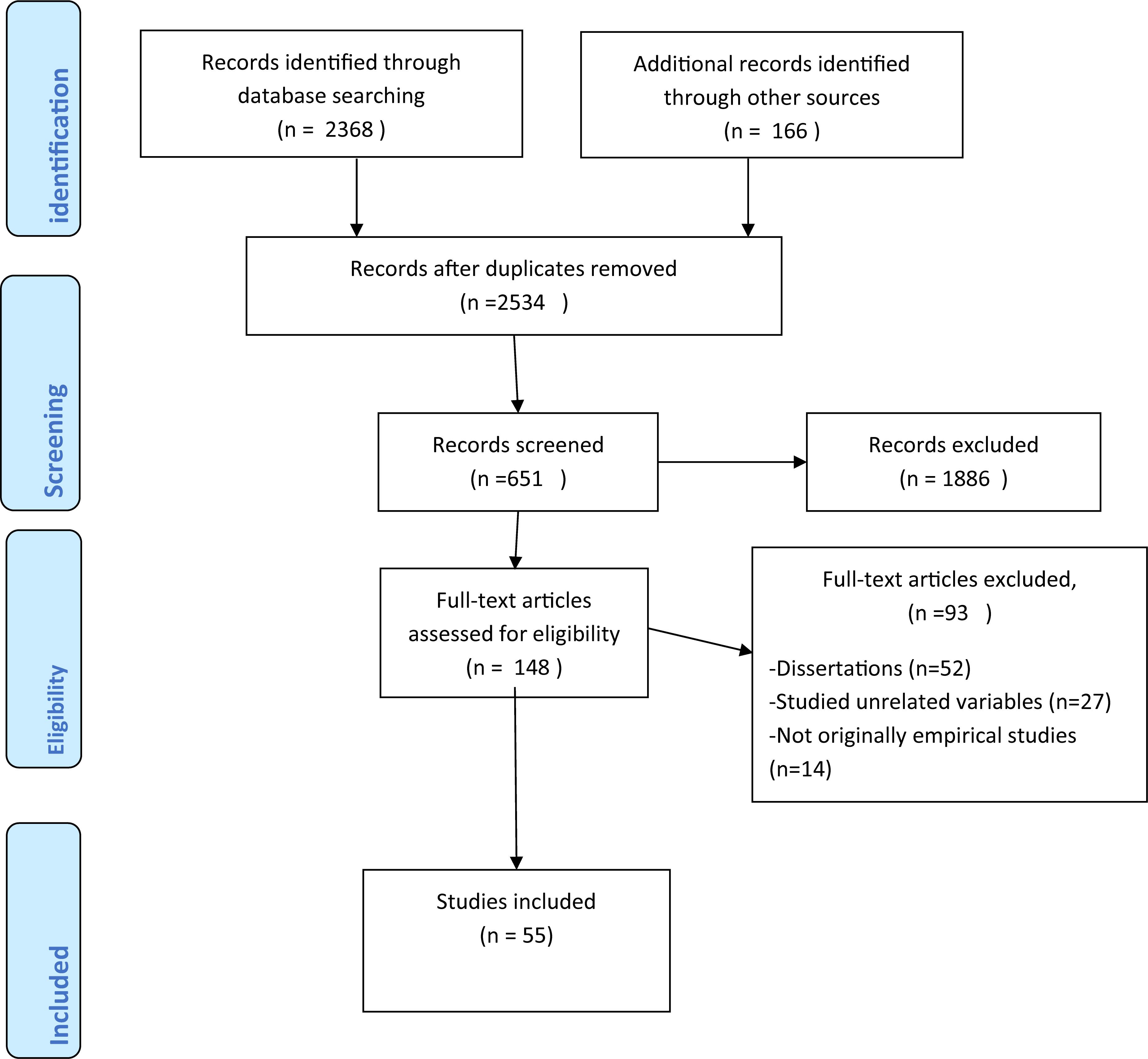

The studies’ country of origin, design, methods, and key findings are presented in Table 2. Of the 55 included studies in the present review, the majority were from the United States (n = 43). Other countries with less than five studies included: Canada, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Australia, Finland, Norway, Israel, and Spain. The vast majority of the included studies were conducted in a single country, except for one study conducted in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Italy (Frost et al., 2018), and another study conducted in the United States, Finland, the United Kingdom, and Norway (Juhasz and Skivenes, 2018). See Figure 1 for a display of study identification, screening, and the final study selection.

Support as framed by these studies somewhat varied, although they all shared similar scope. Depending on the study in focus, “support” was framed as colleagues/collegiate support, organizational support, social support, peer support, administrative support, supervisor support, and coworker support. Others framed support as emotional support, perceived agency support, and perceived organizational support. Although the included studies framed support differently, a closer look shows that they all could be categorized under three main support types of coworker/peer support, social/organizational/management support, and supervisor/leadership support. These three are presented below.

Coworker/Peer Workplace Support

Eighteen of the included studies investigated the impact of peer support among CWW (Davis-Sacks et al., 1985; Jayaratne et al., 1986; Fryer et al., 1988, 1989; Landsman, 2001; Bride, 2007; Barbee et al., 2009; Chenot et al., 2009; Cohen-Callow et al., 2009; Morazes et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2011; Aguiniga et al., 2013; Salloum et al., 2015; Biggart et al., 2017; Schelbe et al., 2017; Baugerud et al., 2018; He et al., 2018; Radey et al., 2018; Hermon and Chahla, 2019). Jayaratne et al. (1986) found a negative relationship between coworker support and reports of burnout. The authors further conducted a series of T-tests to compare the highs and the lows of support scores. Only two out of the nine tests were significant, coworker support being one of them. Bride (2007) report a negative (significant) correlation between workers’ experience of secondary traumatic stress and peer support. They concluded that employers could reduce workers experiences of secondary traumatic stress by cultivating opportunities for peer support. In their study on the examination of the internal and external resources in child welfare, He et al. (2018) found that peer support was negatively associated with client-related burnout. Likewise, in their study of survival among recently hired CWW, Radey et al. (2018) found that CWWs place a very high value on “expressive support” from colleagues. They reported one of the respondents saying “I’m surrounded by a lot of caring individuals who not only care about the kids and the families that they are helping, but their team members” (Radey et al., 2018, p. 89). Other studies found peer support to reduce experiences of stress, burnout, turnover, while serving as a source of strength and increasing retention (Davis-Sacks et al., 1985; Fryer et al., 1988, Fryer et al., 1989; Barbee et al., 2009; Chenot et al., 2009; Morazes et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2011; Biggart et al., 2017; Schelbe et al., 2017).

Social/Organizational/Management Workplace Support

Twenty-two of the included studies explored themes related to CWW experiences and/or consequences of organizational or management support (Samantrai, 1992; Landsman, 2001; Smith, 2005; Barak et al., 2006; Healy et al., 2009; Csiernik et al., 2010; Travis and Mor Barak, 2010; Augsberger et al., 2012; Lizano and Barak, 2012; Wu et al., 2013; Kruzich et al., 2014; Madden et al., 2014; Salloum et al., 2015; Baldschun et al., 2016; Dagan et al., 2016; Fernandes, 2016; Hunt et al., 2016; Littlechild et al., 2016; Antonopoulou et al., 2017; Griffiths and Royse, 2017; Hermon and Chahla, 2019). Healy et al. (2009) conducted an international comparative study comprising of respondents from Australia, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. They found work stress, low reward, a culture of blame, and lack of support implicated in workers’ retention. In her study of commitment among CWW, Landsman (2001) found that the experience of low commitment is one of the major predictors of turnover. The study also found agency/management support to be one of the predictors of work commitment. Management support was also positively related to job satisfaction, but this relationship was not significant. Likewise, Lizano and Barak (2012) employed the JD-R model to explore the impact of organizational support on burnout among CWW. The authors found a positive and significant relationship between workers’ perception of organizational support and depersonalization (one of the three sub-categories of burnout). Meaning that less reports of support was related to more burnout (depersonalization). Eight studies investigated the influence of management support on retention and turnover (Samantrai, 1992; Smith, 2005; Travis and Mor Barak, 2010; Augsberger et al., 2012; Kruzich et al., 2014; Madden et al., 2014; Fernandes, 2016; Griffiths and Royse, 2017). Perception of organizational support influences workers’ decisions to stay/leave. This finding was common for all studies. Wu et al. (2013) explored the essence of organizational support for workers’ work-life balance. They reported a positive relationship between workers perceived organizational support and experiences of a higher work-life balance. Both Hunt et al. (2016) and Littlechild et al. (2016) investigated the importance of organizational support among CWW facing violence and aggression from parents. In some of the included studies, participants reported different sets of safety measures installed in order to keep threats to their lives at bay. Some of these measures include necessity to change their real names, cars, fitting alarms to their homes, and other types of surveillance systems. Participants also reported experiencing anxiety, panic attacks, inability to sleep, and taking time off from work. Some of these workers reported that they did not get any support not understanding from the management despite the seriousness of their circumstances working with aggressive and violent clients (Littlechild et al., 2016). Other studies reported that social support was negatively and significantly correlated with secondary traumatization among a sample of CWW (Salloum et al., 2015; Dagan et al., 2016).

Supervisor/Leadership Workplace Support

Twenty-three of the included studies explored supervisor support among CWWs (Davis-Sacks et al., 1985; Jayaratne et al., 1986; Samantrai, 1992; Dickinson and Perry, 2002; Curry et al., 2005; Smith, 2005; Westbrook et al., 2006; Juby and Scannapieco, 2007; Scannapieco and Connell-Carrick, 2007; Jacquet et al., 2008; Landsman, 2008; Chenot et al., 2009; Cohen-Callow et al., 2009; O’Donnell and Kirkner, 2009; Yankeelov et al., 2009; Chen and Scannapieco, 2010; Williams et al., 2011; Kruzich et al., 2014; Littlechild et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018; Radey et al., 2018; Hermon and Chahla, 2019). One study looked at the relationship between supervisor support and stress, as well as the relationship between supervisor support and satisfaction (Hermon and Chahla, 2019). Using a series of multilevel models, Chenot et al. (2009) investigated the influence of supervisor support among newly recruited CWW. They found that supervisor support predicted retention among newly recruited CWW. Thirteen other studies examined supervisor support and retaining workers approaching retirement (Cohen-Callow et al., 2009), retention (Dickinson and Perry, 2002; Smith, 2005; Scannapieco and Connell-Carrick, 2007; Jacquet et al., 2008; O’Donnell and Kirkner, 2009; Yankeelov et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2011), turnover (Curry et al., 2005; Kruzich et al., 2014), violence and aggression against CWW (Littlechild et al., 2016), desire to stay, and decision to leave (Samantrai, 1992; Chen and Scannapieco, 2010).

Discussion

In this scoping review, we identified 55 primary studies exploring a plethora of workplace support related themes among CWW published between 1985 and 2019. The included studies focused on different types of support at work, they also explored the relationship between their chosen workplace support and job satisfaction, job commitment and engagement, secondary traumatic stress, violence, turnover intentions, intentions to stay, retention, and turnover. They also investigated the roles of support at work in heavy and high workload, job stress, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, role stress, role conflict, role ambiguity, career advancement, unmet expectation, work-family conflict, work-life balance, and emotional exhaustion.

Essence of Workplace Support

Our findings show that the essence of workplace support is found in its dual ability, i.e. the potential to increase positive workplace outcomes (e.g. job satisfaction, engagement, commitment, meaning in the work) while simultaneously reducing the likelihood of occurrence or the effect of exposure to negative workplace experiences (e.g. burnout, stress, trauma, heavy workload). It is logical to think that workers who experience support by the management, supervisors, and colleagues are more likely to feel more secured, happy with their work, experience a very sense of belonging and positive attachment to the workplace, and are also more likely to exert substantial efforts toward any given tasks. Concerning the results from the current review, that workplace support ameliorates CWW’s negative experiences at work, this is in line with recent findings from reviews (Mor Barak et al., 2001; DePanfilis and Zlotnik, 2008). As mentioned in Section “Introduction,” workplace support was implicated in workers decision regarding staying or quitting their positions (DePanfilis and Zlotnik, 2008). The stayers reported experiencing more support than the leavers did.

Similarly, the study conducted by McFadden et al. (2015) investigated individual and organizational factors associated with resilience and burnout among CWW. Having peer support and supervisor support provided a buffering effect on burnout and turnover. One could also argue that initiating and practicing workplace support is cost effective in the sense that the giving and experiencing of support does not have to cost anything in terms of resources. Just that path on the back, the gentle look of compassion and understanding when a coworker or subordinate complains about their experiences will go a long way in helping these coworkers deal with the exposures to negative workplace outcomes. It is almost like the saying “the best things in life are free,” providing and receiving support as shown by the included studies portrays an action or activity that takes so little to achieve but yet generates a significant effect when received. Past research on thriving at work and psychological safety also provides support for the importance of workplace support (Kahn, 1990: Paterson et al., 2014).

The essence of workplace support is also made obvious especially in its absence. In one of their studies on aggression and violence against CWW, Littlechild et al. (2016) reported one of the respondents mentioning that she repeatedly received death threats and threats of violence, with her home address available to these potential assailants, and that it took a while before the management took her seriously. It is common that workers put in a lot of efforts into what they do at work and things get too overpowering as a result of the emotions involved. This could be related to the difficult decisions they have to make, or the outright weight of the amount of cases they have to deal with, it is safe to argue that having the understanding and support of the management, supervisor, and colleagues becomes necessary in order to appropriately deal with these risks. In their definition of social support in the workplace, Karasek and Theorell (1990) did not mention the roles of the management. The support of the management is quite important to any CWW. Added to this is that most CWWs agencies could have up to three levels of leadership positions (the main leader, section leader, and the workgroup leader). In view of this, we want to define workplace support as the sum of support available to a worker at her workplace. And this includes support from the management, supervisor/leader, as well as from colleagues and every notable bodies/groups in the agency.

While results from this review showed a high focus on numerous workplace outcomes as they relate with workplace support among CWW, our findings also indicated a paucity of research focusing on other essential areas of work environment. For instance, we rarely find studies investigating themes like harassment, bullying, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), and counterproductive work behavior (CWB). These workplace variables are particularly essential because of the roles they play in employees’ day-to-day experiences at work, as well as employees’ well-being and health. Looking at the literature, especially within sectors outside child welfare, past research has linked variables like employees experiences of bullying, workplace harassment, OCB, and CWB with employees well-being, health, and performance (Smith et al., 1983; Organ, 1997; Podsakoff et al., 2000; Rotundo and Sackett, 2002; Dalal, 2005; Podsakoff et al., 2010). Take OCB and CWB as examples, their proponents argue that social exchange theory–(Thibaut and Kelley, 1959, as cited in Arya and Kaushik (2015); the theory of psychological contracts–(Rousseau, 1989); and the norm of reciprocity—(Gouldner, 1960) explains occurrence of OCB and CWB on the one hand and job satisfaction, experience of organizational justice, and organizational commitment on the other (Dalal, 2005). The crucial point here is that the working conditions of CWW should be taken seriously as the rest of the other employees found in any other sector. Owing to the nature of their work, expectations from parents and society, and the difficulties they experience daily, CWW’s health and well-being within the workspace deserves in our opinion more attention than the status.

As pointed out in Section “Introduction,” CWW can be compared to employees within SCOs where decisions, especially wrong ones, could have damaging consequences to those involved and the society. A critical look at the workplace experiences of employees from the SCOs within Norway, for instance, illustrates largely a different picture compared with the child welfare service. Under the umbrella of the petroleum safety authority Norway (PSA), the industry conducts annual and biannual investigations of the work environment, and especially as they relate to themes like safety, which is a core theme to all and sundry in this sector. According to PSA (2019), conducting annual/biannual studies and safety work environment investigations increases awareness of the specific HSE challenges facing the industry, and this in turn enables them to conduct effective preventive work environment and safety work (PSA, 2019). In a similar fashion, the existing state of affairs within the child welfare regarding workplace and work conditions begs for focus on the core workplace environmental variables. We believe attention should be directed toward variables like workload, bullying, harassment, organizational justice, OCB, CWB, etc., not only because past research has shown their importance, but more so because “there is a certain, poetry in behaving badly in response to some perceived injustice” (Sackett and DeVore, 2001, p. 160).

Put together, our findings showed that the majority of the included studies focused largely on turnover (or related themes, i.e. turnover intentions, stay intentions, and retention). At this junction, one can safely say that we now have a working knowledge of these variables. Thus, research that focus on a comprehensive/all-inclusive approach will go a long way to providing us with tools needed to better the work environment of employees within the child welfare. While the focus on these aforementioned themes are not inherently wrong nor far-fetched (there are abundance of useful knowledge from findings reported by past studies), we believe that shifting the focus (or expanding the focus) to cover those crucial areas might enable us to know more about a healthy work environment among this workgroup. The argument here is that authors should embrace focusing on factors that stimulate a better working culture, successful independent and collective working groups, as well as a healthy work environment, as opposed to concentrating heavily, on why employees are leaving or thinking about leaving. It is plausible to argue that this line of research will eventually safeguard against the reliance on last minute or what we can refer to as the fire brigade approach to research on turnover, turnover intentions and retentions among CWW.

Dealing With the Fire Brigade Approach

The “fire brigade approach” refers to desperate actions taken to quench a deteriorating situation, as opposed to earlier devotions/interventions to its causes. Our findings identified a host of psychosocial risk factors that are associated with workplace support. Remaining in a workplace/workforce does not always translate into thriving and good experience. Research on absenteeism and presentism has shown that employees could remain on the job while constantly calling in sick. This will eventually add more workloads to the rest of their workgroup. Employees may also show up every working day without putting in any tangible efforts or contributions toward the expected task owing to sickness and indisposition (Jensen and McIntosh, 2007). Authors refer to this as presenteeism or disengagement (Aronsson and Gustafsson, 2005; Hansen and Andersen, 2008). When we measure a functional child welfare workplace in terms of those who stay or leave, we miss these groups of employees that are sick or just not doing their jobs.

Strengths and Limitations of the Present Review

Since this is the first paper to focus on the importance of workplace support among CWW (to our knowledge), this will provide scholars and policy makers with the state of events in the field especially as regarding the importance of workplace support. The inclusion of only peer-reviewed articles (scientific evidence) adds more credibility to the study. The present scoping review has some limitations. The majority of the included studies were published in the United States. Another limitation common to all scoping reviews is the absence of a quality assessment of the included studies. We must, however, point it out that scoping reviews are conducted to identify research in a given field, and quality assessment falls outside of its scope and focus (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). Owing to the aims of our study, we streamlined our search to focus only on studies exploring the importance of workplace support among child welfare employees. Although our strategy appears to be clear, but we might have missed some studies even though they included CWWs in their sample. This may have occurred if studies have been unclear about the composition of their sample data.

Further Research Opportunities

– The influence of leadership styles on CWWs’ exposure to and coping with psychosocial risk at work.

– The role of a health promoting work climate and culture on performance, health, and well-being among CWWs.

– The prevalence and impact of harassment, violence, and bullying among child welfare employees, and their effect on performance and well-being.

– The connection between employees’ exposure to psychosocial risk and deplorable workplace behaviors.

Conclusion

In view of the impacts of psychosocial risks on workers’ health and well-being, efforts should be geared toward raising awareness on the importance of support among CWW, especially as it relates to the risks identified in the present scoping review. Research on the association between workplace support and psychosocial risks among CWW is not new, but this review is the first to summarize and analyze existing literature on the essence of workplace support among CWWs.

Author Contributions

All listed authors have contributed substantially to the final manuscript and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work is part of the first author’s Ph.D. project with the University of Bergen.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aguiniga, D. M., Madden, E. E., Faulkner, M. R., and Salehin, M. (2013). Understanding intention to leave: a comparison of urban, small-town, and rural child welfare workers. Adm. Soc. Work 37, 227–241. doi: 10.1080/03643107.2012.676610

Antonopoulou, P., Killian, M., and Forrester, D. (2017). Levels of stress and anxiety in child and family social work: workers’ perceptions of organizational structure, professional support and workplace opportunities in children’s services in the UK. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 76, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.028

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aronsson, G., and Gustafsson, K. (2005). Sickness presenteeism: prevalence, attendance pressure factors, and an outline of a model for research. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 47, 958–966. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000177219.75677.17

Arya, B., and Kaushik, N. (2015). Forgiveness and relationship quality: a dyadic perspective. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 6, 57–61.

Augsberger, A., Schudrich, W., Mcgowan, B. G., and Auerbach, C. (2012). Respect in the workplace: a mixed methods study of retention and turnover in the voluntary child welfare sector. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1222–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.016

Bakker, A., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010069

Baldschun, A., Totto, P., Hamalainen, J., and Salo, P. (2016). Modeling the occupational well-being of Finnish social work employees: a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 40, 524–539. doi: 10.1080/23303131.2016.1178201

Barak, M. E. M., Levin, A., Nissly, J. A., and Lane, C. J. (2006). Why do they leave? Modeling child welfare workers’ turnover intentions. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 28, 548–577. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.06.003

Barbee, A. P., Antle, B., Sullivan, D. J., Huebner, R., Fox, S., and Hall, J. C. (2009). Recruiting and retaining child welfare workers: is preparing social work students enough for sustained commitment to the field? Child Welf. 88, 69–86.

Baugerud, G., Vangbæk, S., and Melinder, A. (2018). Secondary traumatic stress, burnout and compassion satisfaction among Norwegian child protection workers: protective and risk factors. Br. J. Soc. Work 48, 215–235.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., and Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5, 323–370. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Biggart, L., Ward, E., Cook, L., and Schofield, G. (2017). The team as a secure base: promoting resilience and competence in child and family social work. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 83, 119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.031

Birch, D. A. (1998). Identifying sources of social support. J. Sch. Health 68, 159–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06335.x

Bride, B. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc. Work 52, 63–70. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.63

Brough, P., and Pears, J. (2004). Evaluating the influence of the type of social support on job satisfaction and work-related psychological well-being. Int. J. Organ. Behav. 8, 472–485.

Chen, S.-Y., and Scannapieco, M. (2010). The influence of job satisfaction on child welfare worker’s desire to stay: an examination of the interaction effect of self-efficacy and supportive supervision. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 32, 482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.10.014

Chenot, D., Benton, A., and Kim, H. (2009). The Influence of supervisor support, peer support, and organizational culture among early career social workers in child welfare services. Child Welf. 88, 129–147.

Cohen, S., and Hoberman, H. M. (1983). Positive events and social supports as buffers of life-change stress. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 13, 99–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb02325.x

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Cohen-Callow, A., Hopkins, K. M., and Kim, H. J. (2009). Retaining workers approaching retirement: why child welfare needs to pay attention to the aging workforce. Child Welf. 88, 209–228.

Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., O’Brien, K., Straus, S., Tricco, A., Perrier, L., et al. (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Cox, T., Griffths, A., Barlow, C., Randall, R., Thomson, T., and Rial-Gonza’lez, E. (2000). Organisational Interventions for Work Stress: a Risk Management Approach. Sudbury: HSE Books.

Cox, T., Karanika, M., Mellor, N., Lomas, L., Houdmont, J., and Griffths, A. (2007). Implementation of the Management Standards for Work-Related Stress: Process Evaluation. Sudbury: HSE Books.

Csiernik, R., Smith, C., Dewar, J., Dromgole, L., and O’Neill, A. (2010). Supporting new workers in a child welfare agency: an exploratory study. J. Workplace Behav. Health 25, 218–232. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2010.496333

Curry, D., McCarragher, T., and Dellmann-Jenkins, M. (2005). Training, transfer, and turnover: exploring the relationship among transfer of learning factors and staff retention in child welfare. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 27, 931–948. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.12.008

Dagan, S. W., Ben-Porat, A., and Itzhaky, H. (2016). Child protection workers dealing with child abuse: the contribution of personal, social and organizational resources to secondary traumatization. Child Abuse Negl. 51, 203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.008

Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 1241–1255. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

Daudt, H., Van Mossel, C., and Scott, S. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

Davis-Sacks, M. L., Jayaratne, S., and Chess, W. A. (1985). A comparison of the effects of social support on the incidence of burnout. Soc. Work 30, 240–244. doi: 10.1093/sw/30.3.240

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512.

DePanfilis, D., and Zlotnik, J. L. (2008). Retention of front-line staff in child welfare: a systematic review of research. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 30, 995–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.017

Dickinson, N. S., and Perry, R. E. (2002). Factors influencing the retention of specially educated public child welfare workers. J. Health Soc. Policy 15, 89–103. doi: 10.4324/9781315864839-7

Etzion, D. (1984). Moderating effect of social support on stress-burnout relationship. J. Appl. Psychol. 69, 615–622. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.4.615

Fernandes, G. M. (2016). Organizational climate and child welfare workers’ degree of intent to leave the job: evidence from New York. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 60, 80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.11.010

Festinger, T., and Baker, A. (2010). Prevalence of recalled childhood emotional abuse among child welfare staff and related well-being factors. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 32, 520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.11.004

Frost, L., Hojer, S., Campanini, A., Sicora, A., and Kullburg, K. (2018). Why do they stay? A study of resilient child protection workers in three European countries. Eur. J. Soc. Work 21, 485–497. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2017.1291493

Fryer, G. E. Jr., Miyoshi, T. J., and Thomas, P. J. (1989). The relationship of child protection worker attitudes to attrition from the field. Child Abuse Negl. 13, 345–350. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(89)90074-4

Fryer, G. E., Poland, J. E., Bross, D. C., and Krugman, R. D. (1988). The child protective service worker: a profile of needs, attitudes, and utilization of professional resources. Child Abuse Negl. 12, 481–490. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90065-8

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 25, 161–178.

Grant, M., and Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 26, 91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Griffiths, A., and Royse, D. (2017). Unheard voices: why former child welfare workers left their positions. J. Public Child Welf. 11, 73–90. doi: 10.1080/15548732.2016.1232210

Griffths, A. (1998). “The psychosocial work environment,” in The Changing Nature of Occupational Health, eds R. C. McCaig, and M. J. Harrington (Sudbury: HSE Books).

Hansen, C. D., and Andersen, J. D. (2008). Going ill to work – What personal circumstances, attitudes and work-related factors are associated with sickness presenteeism? Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.022

Harris, J. I., Winskowski, A. M., and Engdahl, B. E. (2007). Types of workplace social support in the prediction of job satisfaction. Career Dev. Q. 56, 150–156. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00027.x

He, A. S., Phillips, J. D., Lizano, E. L., Rienks, S., and Leake, R. (2018). Examining internal and external job resources in child welfare: protecting against caseworker burnout. Child Abuse Negl. 81, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.013

Healy, K., Meagher, G., and Cullin, J. (2009). Retaining novices to become expert child protection practitioners: creating career pathways in direct practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 39, 299–317. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcm125

Hermon, S. R., and Chahla, R. (2019). A longitudinal study of stress and satisfaction among child welfare workers. J. Soc. Work 19, 192–215. doi: 10.1177/1468017318757557

Hunt, S., Goddard, C., Cooper, J., Littlechild, B., and Wild, J. (2016). ‘If I feel like this, how does the child feel?’ child protection workers, supervision, management and organisational responses to parental violence. J. Soc. Work Pract. 30, 5–24. doi: 10.1080/02650533.2015.1073145

Huurre, T. M., Komulainen, E. J., and Aro, H. M. (1999). Social support and self-esteem among adolescents with visual impairments. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 93, 26–37. doi: 10.1177/0145482x9909300104

Hwang, J., and Hopkins, K. (2012). Organizational inclusion, commitment, and turnover among child welfare workers: a multilevel mediation analysis. Adm. Soc. Work 36, 23–39. doi: 10.1080/03643107.2010.537439

Iversen, A. C., and Heggen, K. (2016). Child welfare workers use of knowledge in their daily work. Eur. J. Soc. Work 19, 187–203. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2015.1030365

Jacquet, S., Clark, S., Morazes, J., and Withers, R. (2008). The role of supervision in the retention of public child welfare workers. J. Public Child Welf. 1, 27–54. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw191

Jayaratne, S., Chess, W. A., and Kunkel, D. A. (1986). Burnout: its impact on child welfare workers and their spouses. Soc. Work 31, 53–59. doi: 10.1093/sw/31.1.53

Jensen, S., and McIntosh, J. (2007). Absenteeism in the workplace: results from Danish sample survey data. Empir. Econ. 32, 125–139. doi: 10.1007/s00181-006-0075-4

Juby, C., and Scannapieco, M. (2007). Characteristics of workload management in pulic child welfare agencies. Adm. Soc. Work 31, 95–109. doi: 10.1300/j147v31n03_06

Juhasz, I., and Skivenes, M. (2018). Child welfare workers’ experiences of obstacles in care order preparation: a cross-country comparison. Eur. J. Soc. Work 21, 100–113. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2016.1256868

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.5465/256287

Karasek, R. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 24, 285–306.

Karasek, R. A., and Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Kef, S. (1997). The personal networks and social supports of blind and visually impaired adolescents. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 91, 236–244.

Kelloway, E. (2011). Positive organizational scholarship. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. D 28, 1–3.

Kim, A., and Mor Barak, M. E. (2015). The mediating roles of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support in the role stress-turnover intention relationship among child welfare workers: a longitudinal analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 52, 135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.11.009

Kim, H., and Hopkins, K. M. (2015). Child welfare workers’ personal safety concerns and organizational commitment: the moderating role of social support. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 39, 101–115. doi: 10.1080/23303131.2014.987413

Kim, H., and Kao, D. (2014). A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among U.S. child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 47(Part 3), 214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.015

Kim, J., Park, T., Pierce, B., and Hall, J. A. (2018). Child welfare workers’ perceptions of supervisory support: a curvilinear interaction of work experience and educational background. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 42, 285–299. doi: 10.1080/23303131.2017.1395775

Kruzich, J. M., Mienko, J. A., and Courtney, M. E. (2014). Individual and work group influences on turnover intention among public: child welfare workers: the effects of work group psychological safety. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 42, 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.005

Landsman, M. J. (2001). Commitment in public child welfare. Soc. Serv. Rev. 75, 386–419. doi: 10.1086/322857

Landsman, M. J. (2008). Pathways to organizational commitment. Adm. Soc. Work 32, 105–132. doi: 10.1300/J147v32n02_07

Lee, K., Pang, Y. C., Lee, J. A. L., and Melby, J. N. (2017). A study of adverse childhood experiences, coping strategies, work stress, and self-care in the child welfare profession. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 41, 389–402. doi: 10.1080/23303131.2017.1302898

Leka, S., Cox, T., Makrinov, N., Ertel, M., Hallsten, L., Iavicoli, S., et al. (2007). Towards the Development of a Psychosocial Risk Management Toolkit. Stockholm: SALTSA.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., and O’Brien, K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5:69.

Littlechild, B., Hunt, S., Goddard, C., Cooper, J., Raynes, B., and Wild, J. (2016). The effects of violence and aggression from parents on child protection workers’ personal, family, and professional lives. Sage Open 6:2158244015624951. doi: 10.1177/2158244015624951

Lizano, E. L., and Barak, M. E. M. (2012). Workplace demands and resources as antecedents of job burnout among public child welfare workers: a longitudinal study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1769–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.006

Lizano, E. L., Hsiao, H.-Y., Barak, M. E., and Casper, L. M. (2014). Support in the workplace: buffering the deleterious effects of work-family conflict on child welfare workers’ well-being and job burnout. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 40, 178–188. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2013.875093

Lovseth, L. T. (2017). The hidden stressor of child welfare workers: client confidentiality as a barrier for coping with emotional work demands. Child Fam. Soc. Work 22, 923–931. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12312

Madden, E. E., Scannapieco, M., and Painter, K. (2014). An examination of retention and length of employment among public child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 41, 37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.02.015

McFadden, P., Campbell, A., and Taylor, B. (2015). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. Br. J. Soc. Work 45, 1546–1563. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct210

Mor Barak, M., Nissly, J., and Levin, A. (2001). Antecedents to retention and turnover among child welfare, social work, and other human service employees: what can we learn from past research? A review and metanalysis. Soc. Serv. Rev. 75, 625–661. doi: 10.1086/323166

Morazes, J., Benton, A., Clark, S., and Jacquet, S. (2010). Views of specially-trained child welfare social workers: a qualitative study of their motivations, perceptions, and retention. Qual. Soc. Work 9, 227–247. doi: 10.1177/1473325009350671

O’Donnell, J., and Kirkner, S. (2009). A longitudinal study of factors influencing the retention of Title IV-E master’s of social work graduates in public child welfare. J. Public Child Welf. 3, 64–86. doi: 10.1080/15548730802690841

Organ, D. W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: it’s construct cleanup time. Hum. Perform. 10, 85–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1002_2

Papakonstantinou, D., and Papadopoulos, K. (2010). Forms of social support in the workplace for individuals with visual impairments. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 104, 183–187. doi: 10.1177/0145482x1010400306

Paterson, T. A., Luthans, F., and Jeung, W. (2014). Thriving at work: impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 434–446. doi: 10.1002/job.1907

Pham, M. T., Rajic, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., and McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 5, 371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123

Podsakoff, N. P., Whiting, S. W., Podsakoff, P. M., and Mishra, P. (2010). Effects of organizational citizenship behaviors on selection decisions in employment interviews. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 310–326. doi: 10.1037/a0020948

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., and Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: a critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 26, 513–563. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600307

PSA, (2019). Available at: https://www.ptil.no/en/contact-us/loose-pages-contact-us/order-publications/notat-om-risikostyring/ (accessed September 12, 2019).

Radey, M., Schelbe, L., and Spinelli, C. L. (2018). Learning, negotiating, and surviving in child welfare: social capitalization among recently hired workers. J. Public Child Welf. 12, 79–98. doi: 10.1080/15548732.2017.1328380

Rotundo, M., and Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: a policy-capturing approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 66–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.66

Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities Rights J. 2, 121–139. doi: 10.1007/bf01384942

Sackett, P. R., and DeVore, C. J. (2001). “Counterproductive behaviors at work,” in Handbook of Industrial, Work, and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 1, eds N. Anderson, D. Ones, H. Sinangil, and C. Viswesvaran (London: Sage), 145–164.

Salloum, A., Choi, M. J., and Stover, C. S. (2018). Development of a trauma-informed self-care measure with child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 93, 108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.008

Salloum, A., Kondrat, D. C., Johnco, C., and Olson, K. R. (2015). The role of self-care on compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary trauma among child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 49, 54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.023

Samantrai, K. (1992). Factors in the decision to leave: retaining social workers with MSWs in public child welfare. (Master of social work degree). Soc. Work 37, 454–458.

Scannapieco, M., and Connell-Carrick, K. (2007). Child welfare workplace: the state of the workforce and strategies to improve retention. Child Welfare 86, 31–52.

Schaufeli, W. B., and Taris, T. W. (2014). “A critical review of the job demands-resources model: implications for improving work and health,” in Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach, eds G. F. Bauer, and O. Hämmig (Dordrecht: Springer), 43–68. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4

Schelbe, L., Radey, M., and Panisch, L. S. (2017). Satisfactions and stressors experienced by recently-hired frontline child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 78, 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.05.007

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1, 27–41. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27

Smith, A., Organ, D. W., and Near, J. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 68, 653–663.

Smith, B. D. (2005). Job retention in child welfare: effects of perceived organizational support, supervisor support, and intrinsic job value. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 27, 153–169. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.08.013

Tham, P., and Meagher, G. (2009). Working in human services: how do experiences and working conditions in child welfare social work compare? Br. J. Soc. Work 39, 807–827. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcm170

Travis, D. J., and Mor Barak, M. E. (2010). Fight or flight? Factors influencing child welfare workers’ propensity to seek positive change or disengage from their jobs. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 36, 188–205. doi: 10.1080/01488371003697905

Tricco, A., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473.

Weiss, R. S. (1974). “The provision of social relationships,” in Doing Unto Others, ed. Z. Rubin (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall), 17–26.

Westbrook, T. M., Ellis, J., and Ellett, A. J. (2006). Improving retention among public child welfare workers: what can we learn from the insights and experiences of committed survivors? Adm. Soc. Work 30, 37–62. doi: 10.1300/J147v30n04_04

Williams, S. E., Nichols, Q. L., Kirk, A., and Wilson, T. (2011). A recent look at the factors influencing workforce retention in public child welfare. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.028

Wu, L., Rusyidi, B., Claiborne, N., and McCarthy, M. L. (2013). Relationships between work-life balance and job-related factors among child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 35, 1447–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.05.017

Keywords: workplace support, social support, coworker support, leadership/supervisor support, psychosocial risk

Citation: Olaniyan OS, Hetland H, Hystad SW, Iversen AC and Ortiz-Barreda G (2020) Lean on Me: A Scoping Review of the Essence of Workplace Support Among Child Welfare Workers. Front. Psychol. 11:287. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00287

Received: 04 December 2019; Accepted: 06 February 2020;

Published: 25 February 2020.

Edited by:

Renato Pisanti, University of Niccolò Cusano, ItalyReviewed by:

Ilaria Setti, University of Pavia, ItalyCynthia D. Kelly, Independent Researcher, Atlanta, United States

Copyright © 2020 Olaniyan, Hetland, Hystad, Iversen and Ortiz-Barreda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oyeniyi Samuel Olaniyan, b3llbml5aS5vbGFuaXlhbkB1aWIubm8=; b29sMDQ4QHVpYi5ubw==

Oyeniyi Samuel Olaniyan

Oyeniyi Samuel Olaniyan Hilde Hetland2

Hilde Hetland2 Sigurd William Hystad

Sigurd William Hystad Anette Christine Iversen

Anette Christine Iversen